The Silent Architect of Healing: Building a Better TMJ Disc

A groundbreaking blend of natural and synthetic materials is paving the way for a future where joint pain is a thing of the past.

Understanding TMJ Disorders

Imagine a tiny, cartilage-like disc in your jaw—no bigger than a fingernail—that makes every meal, every conversation, and every smile a painful ordeal. For the millions suffering from temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders, this is a daily reality. The TMJ disc is a crucial shock absorber situated between your skull and jawbone. When it deteriorates, the resulting pain can be debilitating.

The Problem

Traditional solutions often fall short in treating TMJ disorders, leaving patients with limited options and persistent pain.

The Solution

Bioengineers are crafting a revolutionary replacement by mimicking the body's own blueprints, combining natural and synthetic materials.

The Silent Architect: Why the Extracellular Matrix Matters

To understand this medical breakthrough, we must first appreciate the body's "silent architect"—the extracellular matrix (ECM). Once thought to be merely a cellular scaffold, the ECM is now known to be a dynamic, information-rich environment that actively guides cell behavior 1 .

It provides not only structural support but also critical biochemical and biomechanical cues that regulate tissue development, maintenance, and repair 1 .

The ECM is a reservoir for various growth factors—such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and transforming growth factor (TGF-β)—which are released in a tightly regulated manner to guide tissue regeneration 1 . Its specific composition, varying from tissue to tissue, is a masterclass in functional design. In cartilage, it creates a slippery, shock-absorbing surface essential for smooth joint movement 4 .

Decellularized ECM (dECM)

Decellularized ECM (dECM) takes this natural architecture and repurposes it for healing. Through a process called decellularization, scientists remove the original cells from a donor tissue—which could cause immune rejection—while meticulously preserving the intricate ECM structure and its beneficial signaling molecules 1 7 9 .

The resulting dECM can then be used as a biological scaffold, providing a familiar "home" for a patient's own cells to migrate into and rebuild new, healthy tissue 7 .

Polyvinyl Alcohol: The Synthetic Workhorse with a Biological Feel

On the other side of this bio-hybrid material is polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), a synthetic hydrogel with remarkable properties. PVA is water-soluble, biocompatible, and can be formulated to have a biomimetic water content similar to that of natural tissues 2 8 .

This is achieved through techniques like directional freezing or freezing-thawing under drawing (FTD), which force the PVA chains to align in a specific orientation 3 5 . The result is a material that is much stronger in one direction—a critical trait for the TMJ disc, which must withstand complex, directional forces during jaw movement .

A Blueprint for Regeneration: The Core Experiment

How do these two components come together to form a functional TMJ disc? A pivotal study provides a clear blueprint, detailing the development and mechanical evaluation of a novel composite scaffold 2 .

Methodology: A Step-by-Step Fusion

The process to create the new TMJ disc involves several precise stages:

dECM Preparation

Cartilage tissue is decellularized using a combination of physical methods (freeze-thaw cycles to rupture cells) and chemical agents (like the detergent SDS) to remove cellular material and genetic components while preserving the valuable ECM proteins and growth factors 4 . The resulting dECM is then broken down into a powder.

PVA Hydrogel Formulation

PVA is dissolved in water and heated to create a clear solution. Concentrations of 15%, 20%, and 25% PVA are typically tested to find the optimal mechanical profile 2 .

Composite Bioink Creation

The dECM powder is thoroughly mixed with the PVA solution. To make this mixture printable or moldable, it is often combined with other biopolymers like gellan gum, which provides structural integrity during and after the fabrication process 4 .

Anisotropic Structuring

The composite solution is subjected to a freezing-thawing under drawing (FTD) process. The material is stretched to a specific "drawing ratio" (e.g., 100% or 200% of its original length) and then frozen. This orients the PVA crystallites and polymer chains in the direction of the stretch, creating a mechanically anisotropic gel 3 .

Results and Analysis: Matching Nature's Design

The mechanical evaluation of the resulting composite scaffolds reveals their promising potential. When compared to a natural ovine TMJ disc, the synthetic-biologic hybrid shows remarkable similarities.

Key Finding

A key finding is that the 25% PVA hydrogel composite was the best candidate, demonstrating the most similarity to the native TMJ disc's compressive properties 2 . This indicates that the scaffold can effectively act as a shock absorber.

Friction Properties

Crucially, there was no statistically significant difference in the coefficient of friction between the PVA hydrogels and the natural TMJ disc 2 . This means the artificial disc is just as slippery and smooth as the natural one, a vital property for reducing wear and tear on the joint's articulating surfaces.

Table 1: Tensile Property Comparison between PVA Hydrogels and Native TMJ Disc

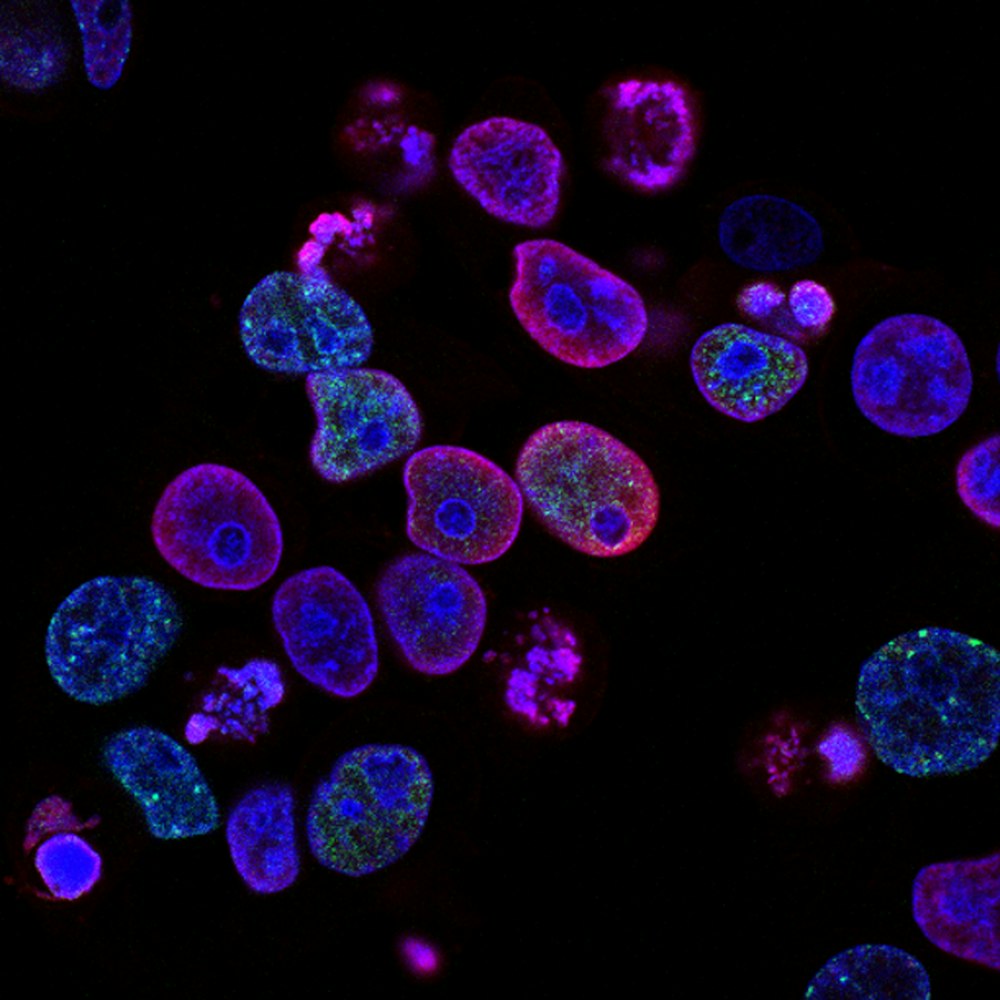

Furthermore, biological assays confirmed the success of the dECM component. Cell viability tests showed a high survival rate (97.41%) on the dECM-containing scaffolds, and staining techniques proved the deposition of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs)—essential molecules for cartilage function—confirming that the scaffold actively promotes a cartilage-like cellular environment 4 .

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Building a Bio-Hybrid Joint

Creating a biomimetic TMJ disc requires a specialized set of tools and materials. The following table details the key "research reagent solutions" essential to this innovative process.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Process |

|---|---|

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | Synthetic polymer that forms the strong, durable, and tunable hydrogel base of the scaffold 2 8 . |

| Decellularized ECM (dECM) | Provides the biological cues, proteins, and growth factors that mimic the native tissue environment and promote cell attachment and regeneration 4 7 . |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | An ionic detergent used in decellularization to disrupt cell membranes and solubilize cytoplasmic components, effectively removing cellular material 1 4 . |

| Gellan Gum | A polysaccharide used as a thickening and gelling agent in the bioink to improve printability and provide initial structural support before permanent cross-linking 4 . |

| Cross-linking Agents (e.g., EDC/NHS) | Chemicals used to create stable covalent bonds between polymer chains, strengthening the scaffold's mechanical structure 6 . |

Laboratory Setup

Specialized equipment is required for precise material synthesis and testing.

Material Synthesis

Precise control over material properties is essential for biomimetic design.

Mechanical Testing

Rigorous testing ensures materials meet the demanding requirements of joint function.

The Future of Joint Repair

The journey to create a perfect artificial TMJ disc is well underway. The synergistic combination of anisotropic PVA and decellularized ECM represents a paradigm shift in tissue engineering. While challenges remain—particularly in perfectly replicating the high tensile stiffness of native tissue—the progress is undeniable 2 .

Applications Beyond TMJ

This bio-hybrid strategy is not limited to the jaw. It paves the way for engineering a range of load-bearing tissues, from knee menisci to intervertebral discs.

- Knee meniscus repair

- Intervertebral disc replacement

- Cartilage regeneration in osteoarthritis

- Other load-bearing tissue engineering applications

Regenerative Medicine Potential

By learning from and collaborating with the body's own silent architect, scientists are developing solutions that don't just replace what is lost, but actively guide the body to heal itself.

The future of regenerative medicine is not just synthetic or natural; it is intelligently, and beautifully, both.

Table 3: Advantages and Challenges of the Bio-Hybrid Approach

| Aspect | Advantages | Remaining Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Performance | Tunable strength; Anisotropy mimics native tissue; Low friction 2 3 . | Tensile modulus still lower than native tissue in some directions 2 . |

| Biological Integration | dECM provides natural cues for cell adhesion and tissue formation 4 7 . | Ensuring complete decellularization to avoid immune response 1 . |

| Manufacturing | 3D bioprinting allows for patient-specific shapes and structures 1 4 . | Standardizing and scaling up production for clinical use 1 . |

The future of joint repair lies in biomimetic approaches that combine the best of synthetic and natural materials.