Strategic Control of Biomaterial Degradation: From Molecular Design to Clinical Application in Tissue Engineering and Drug Delivery

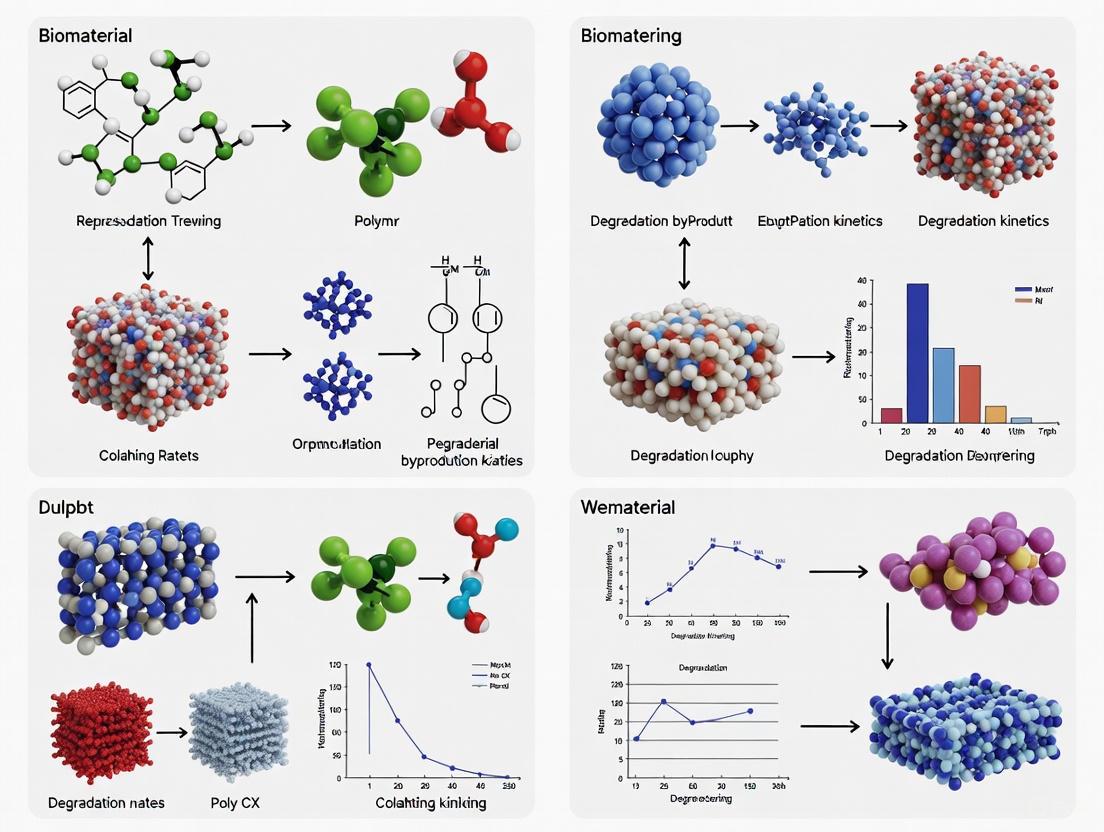

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies for optimizing biomaterial degradation rates to meet specific clinical needs in regenerative medicine and drug delivery.

Strategic Control of Biomaterial Degradation: From Molecular Design to Clinical Application in Tissue Engineering and Drug Delivery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies for optimizing biomaterial degradation rates to meet specific clinical needs in regenerative medicine and drug delivery. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles governing degradation, advanced material design and fabrication methodologies, common challenges with targeted solutions, and standardized assessment protocols. By synthesizing foundational science with applied engineering and validation frameworks, this review serves as a strategic guide for developing next-generation biomaterials with precisely tuned in vivo performance, bridging the gap between laboratory innovation and clinical translation.

The Science of Biomaterial Breakdown: Core Principles and Degradation Mechanisms

Biodegradation is the biological catalytic process of breaking down complex macromolecules into smaller, less complex molecular structures (by-products) [1]. In the context of biomaterials, this process is a critical design criterion for achieving optimal tissue regeneration with cell transplantation, as it influences the material's lifetime and its interaction with the biological environment [2]. The ideal scenario involves coupling the degradation rate of polymers used in cell transplantation carriers to the growth rate of the developing tissue, which can significantly improve the quantity and quality of the regenerated tissue [2].

The degradation of biomaterials occurs via three interconnected processes that can be assessed by monitoring physical, chemical, and mechanical changes [1]. Biomaterials contain characteristic functional groups—including ester, ether, amide, imide, thioester, and anhydride—that can be chemically or enzymatically cleaved during the degradation process through hydrolysis or enzymatic action [1].

Key Experimental Protocols for Assessing Biodegradation

Standardized Marine Biodegradation Assessment

The ASTM International D6691-24a standard provides a method for determining aerobic biodegradation of plastic materials in marine environments using a defined microbial consortium or natural sea water inoculum [3]. This protocol serves as a rapid, reliable screening tool for assessing the inherent biodegradability of materials.

Experimental Workflow:

Detailed Protocol Steps:

- Collection and characterization of seawater: Identify a collection site unaffected by wastewater, chemicals, or oil slicks. Collect 10-20 L of seawater using a Niskin bottle and transport in acid-leached carboys. Analyze subsamples for particulate carbon/nitrogen, dissolved inorganic/organic nitrogen/phosphorus, NHâ‚„âº, PO₄³â», and chlorophyll-a concentrations [3].

- Preparation of experimental substrate: Mill 10-15 g of experimental substrate to a uniform particle size (0.10-0.25 mm) using a ball mill after submerging in liquid nitrogen for 15 minutes for embrittlement. Verify size uniformity through sieve analysis per ASTM D1921-96. Determine carbon content per subsample dry weight by elemental analysis [3].

- Preparation of additional nutrients for seawater: Supplement seawater with 0.5 g/L ammonium chloride (NHâ‚„Cl) and 0.1 g/L potassium phosphate monobasic (KHâ‚‚POâ‚„) to prevent nutrient limitation [3].

- Reactor vessel setup and monitoring: Use 250 mL reactor vessels containing 75 mL of nutrient-enriched seawater and approximately 20 mg of experimental substrate. Incubate at 30°C in the dark. Measure CO₂ production using a Micro-Oxymax respirometer or similar closed-loop system [3].

- Calculation of biodegradation: Calculate the degree of mineralization (biodegradation) as the percentage of net carbon biogas (COâ‚‚-C) produced relative to the initial carbon mass added. Include triplicate reactors for each material, plus negative control (seawater only) and positive control (cellulose) [3].

General In Vitro Biodegradation Assessment

For general biomaterial evaluation, a systematic approach should be followed as depicted in the workflow below.

General Biodegradation Assessment Workflow:

The ASTM F1635-11 guidelines highlight that degradation should be monitored via mass loss (gravimetric analysis), changes in molar mass, and mechanical testing [1]. Furthermore, the guidelines specify that molar mass should be evaluated by solution viscosity or size exclusion chromatography (SEC), while weight loss should be measured to a precision of 0.1% of the total sample weight, with samples dried to a constant weight [1].

Troubleshooting Common Biodegradation Experimental Problems

FAQ 1: Why is my biomaterial degrading too quickly or too slowly for my target application?

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Material composition issues: Review the functional groups in your polymer backbone. Esters, anhydrides, and amides have different hydrolysis rates. Incorporating more stable functional groups or cross-linking can slow degradation [1].

- Inadequate pre-treatment: For metals like magnesium alloys, a 30-minute anodizing treatment in 1.6 wt% K₂SiO₃ + 1 wt% KOH or pre-treatment in 1 M NaOH for 24-48 hours can significantly reduce biodegradation rates by forming a passive hydroxide film [2].

- Enzyme-mediated control: For natural polymers like chitosan, incorporate encapsulated hydrolytic enzymes to create systems with controlled degradation at desired sites and specific rates. The degradation kinetics can be adjusted by the amount of encapsulated enzyme [2].

FAQ 2: My weight loss data suggests degradation, but chemical analysis doesn't confirm it. What could be wrong?

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Material solubility vs. degradation: Weight loss can be mistaken for degradation when the material is simply dissolving in the simulated bodily fluid or buffered solution. Always combine gravimetric analysis with chemical characterization techniques such as FTIR, NMR, or SEC to confirm chemical breakdown [1].

- Incomplete degradation products: The material may be fragmenting into larger molecules not detected by your chemical analysis methods. Use multiple analytical techniques including GPC, HPLC, or mass spectrometry to detect intermediate degradation products [1].

FAQ 3: How can I better match my biomaterial's degradation rate to the tissue regeneration timeline?

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Molecular weight tuning: For alginate hydrogels, decrease the size of polymer chains (via γ-irradiation) to increase the in vivo degradation rate. Studies have shown that more rapid degradation led to dramatic increases in the extent and quality of bone formation [2].

- Composite material design: Combine fast-degrading and slow-degrading polymers to create a composite with staged degradation profiles that better match the healing process [4].

- Validation experiment design: Use normalized area metrics based on probability density functions for the deterioration model validation. Employ kernel density estimation to obtain smooth probability density functions from discrete experimental data, reducing systematic error of the validation metric [5].

FAQ 4: Why do I get different degradation results between in vitro and in vivo studies?

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Microbial community differences: In vitro environments may not fully replicate the complex enzymatic and cellular activities in vivo. For marine environments, use natural seawater as the inoculum to capture the in situ microbial community [3].

- Dynamic environmental factors: In vivo environments have fluctuating pH, enzyme concentrations, and mechanical stresses not replicated in static in vitro tests. Consider using dynamic bioreactor systems or incorporating relevant enzymes in your in vitro tests [1] [2].

- Inflammatory response factors: The inflammatory response to implants creates localized pH decreases and secretes hydrolytic enzymes that accelerate degradation. Develop polymeric systems with self-regulated degradation mechanisms that respond to these specific environmental conditions [2].

Quantitative Data and Material Selection Guidance

Table 1: Degradation Rate Control Methods for Different Biomaterial Classes

| Material Class | Method | Effect on Degradation Rate | Key Applications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate hydrogels | γ-irradiation to reduce polymer chain size | Increases degradation rate | Bone tissue engineering | [2] |

| Magnesium alloys | Anodizing in K₂SiO₃ + KOH or pretreatment in NaOH | Significantly decreases degradation rate | Orthopedic implants | [2] |

| Chitosan-based systems | Incorporation of encapsulated lysozyme | Creates enzyme-responsive degradation | Controlled drug delivery | [2] |

| Polymeric scaffolds | Cross-linking density modification | Inverse relationship with degradation rate | Various tissue engineering | [1] |

| Starch-based systems | Incorporation of non-active α-amylase with calcium ion activation | Creates ion-responsive degradation mechanism | Responsive drug delivery | [2] |

Table 2: Comparison of Biodegradation Assessment Techniques

| Technique | Parameters Measured | Advantages | Limitations | Applicable Standards |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gravimetric Analysis | Mass loss over time | Simple, cost-effective, quantitative | Cannot distinguish dissolution from degradation; infers but does not confirm degradation | ASTM F1635-11 |

| Closed-loop Respirometry | COâ‚‚ production | Direct measurement of microbial metabolism; high sensitivity | Does not account for carbon assimilation into biomass; requires specialized equipment | ASTM D6691-24a |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Molecular weight changes | Detects polymer chain scission; quantitative | May not detect small chemical changes; requires soluble samples | - |

| SEM Morphology Analysis | Surface erosion, cracks, pores | Visual evidence of physical changes; high resolution | Qualitative; cannot confirm chemical degradation; sample preparation may introduce artifacts | - |

| FTIR Spectroscopy | Chemical bond changes | Confirms chemical degradation; identifies functional groups | May not detect small changes in complex mixtures; surface-sensitive technique | - |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Biodegradation Experiments

| Reagent | Function/Application | Key Considerations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural seawater inoculum | Provides diverse microbial community for marine biodegradation studies | Collect from unpolluted sites; characterize for nutrients, chlorophyll, salinity; use within 7 days | [3] |

| Ammonium chloride (NHâ‚„Cl) and Potassium phosphate (KHâ‚‚POâ‚„) | Prevents nutrient limitation in marine biodegradation tests | Use 0.5 g/L NHâ‚„Cl and 0.1 g/L KHâ‚‚POâ‚„ based on seawater volume | [3] |

| Cellulose (TLC grade) | Positive control in biodegradation experiments | Historically shown to be biodegradable in marine environments; provides benchmark | [3] |

| Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) | In vitro testing of biomedical materials | Maintain at pH 7.4 or specific pH for targeted bodily environment | [1] |

| Lysozyme enzyme | Study enzyme-mediated degradation of certain polymers (e.g., chitosan) | Concentration and activity should be standardized; represents inflammatory response | [2] |

| NaOH solution | Pre-treatment to reduce degradation rate of metals | 1 M solution with 24-48 hour treatment forms protective passive layer | [2] |

Advanced Strategies and Future Directions

Future advancements in biodegradation assessment should focus on measuring parameters in real-time using non-invasive, continuous, and automated processes [1]. The development of "self-regulated degradation mechanisms" where the degradation process is initiated and/or controlled under specific environment conditions or in response to tissue responses represents a promising frontier [2]. For tissue engineering applications, combining the degradation rate control with the "bottom-up" biomaterial design approach—which prioritizes fundamental biological properties and microenvironmental needs of target cells—will enhance therapeutic outcomes [6].

The integration of machine learning and multi-modal imaging in testing technologies shows promise for more comprehensive biodegradation assessment [4]. Additionally, employing validation metrics such as normalized area metrics based on probability density functions with kernel density estimation can provide more reliable assessment of how well deterioration models simulate actual degradation processes [5].

FAQs: Core Concepts and Mechanisms

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between hydrolytic and enzymatic degradation?

A1: The fundamental difference lies in the mechanism of the chemical reaction that breaks the polymer bonds:

- Hydrolytic Degradation: A passive chemical process where water molecules cleave hydrolytically-labile bonds (e.g., ester, anhydride, amide bonds in polyesters). This process can be autocatalytic because the acidic by-products (e.g., carboxylic acids) generated during degradation accelerate further hydrolysis [7] [8].

- Enzymatic Degradation: An active, biologically catalyzed process where specific enzymes (e.g., lipases, proteases, phosphatases) bind to the polymer and significantly accelerate the scission of chemical bonds. This degradation is typically faster and more specific than hydrolysis alone [7] [9].

Q2: How does the erosion type (bulk vs. surface) differ between the two pathways?

A2: The predominant erosion mechanism is a key differentiator:

- Hydrolytic Degradation most commonly leads to bulk erosion. Water penetrates the entire polymer structure, causing chain scission throughout the bulk material. This can result in a sudden loss of mechanical properties and specimen cracking, even at low mass loss [8].

- Enzymatic Degradation typically follows a surface erosion mechanism. Due to their large size, enzymes cannot easily penetrate the polymer bulk. Instead, they act on the material's surface, creating an erosion front that gradually moves inward. This leads to a more predictable and controllable mass loss over time [7] [9].

Q3: What are the critical material properties that govern the degradation rate?

A3: Several interdependent material properties are crucial [1] [8]:

- Crystallinity: Highly crystalline regions have ordered polymer packing that limits water and enzyme penetration, thereby slowing degradation.

- Glass Transition Temperature (Tg): A Tg above the degradation temperature limits molecular motion and free volume, reducing hydration and slowing hydrolysis.

- Hydrophilicity: More hydrophilic polymers absorb more water, accelerating hydrolytic degradation.

- Molecular Weight: Higher molecular weight generally correlates with longer degradation times.

- Porosity: Porosity facilitates the removal of acidic degradation by-products, reducing autocatalytic effects and can allow deeper enzyme access.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Inconsistent or Irreproducible Degradation Rates

- Potential Cause: Inadequate control of the degradation medium. The pH of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) can drop significantly due to the release of acidic degradation products, changing the degradation kinetics [7].

- Solution: Regularly monitor and refresh the degradation medium (e.g., PBS, HPLC-grade water) according to a strict schedule to maintain a consistent pH and ion concentration. Using a buffer with greater capacity or a flow-through system can help [7].

Problem: Difficulty Distinguishing Between Material Solubility and True Degradation

- Potential Cause: Relying solely on gravimetric analysis (mass loss) can be misleading, as simple dissolution of polymer chains without chemical bond scission can also cause weight loss [1].

- Solution: Employ multiple complementary techniques to confirm degradation. Combine gravimetric analysis with methods that confirm chemical changes, such as Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) to monitor molecular weight reduction, or Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) to identify changes in chemical bonds [1].

Problem: Poor Correlation Between In Vitro and In Vivo Degradation Data

- Potential Cause: Standard in vitro hydrolytic tests (e.g., in PBS) lack the enzymatic activity and complex cellular environment of a living system. A material that degrades slowly in PBS may be rapidly broken down in vivo by specific enzymes [7] [9].

- Solution: Develop more biologically relevant in vitro models. This includes conducting parallel degradation studies in solutions of relevant enzymes (e.g., lipases for polyesters) to simulate the accelerated degradation that can occur in a physiological environment [7].

Experimental Protocols for Pathway Analysis

Protocol: Basic Hydrolytic Degradation Study

This protocol outlines the standard method for assessing the passive hydrolytic degradation of a polyester biomaterial.

1. Sample Preparation:

- Prepare polymer films or scaffolds with precise dimensions (e.g., 10 mm x 10 mm x 1 mm). Record the initial dry weight (Wâ‚€) to a precision of at least 0.1% [1].

- Sterilize samples if intended for biomedical applications.

2. Degradation Setup:

- Immerse individual samples in vials containing a sufficient volume of degradation medium (e.g., Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, pH 7.4, or HPLC-grade water) to ensure sink conditions.

- Add sodium azide (NaN₃) (0.02-0.05% w/v) to the medium to prevent microbial growth [7].

- Incubate the vials in a shaking water bath or oven maintained at 37°C [7].

3. Monitoring and Analysis:

- At predetermined time points, remove samples from the medium (n=3-5 for statistics).

- Gravimetric Analysis: Rinse samples with deionized water, dry to a constant weight, and record the dry weight (Wð‘¡). Calculate mass loss as:

(Wâ‚€ - Wð‘¡)/Wâ‚€ × 100%[7] [1]. - Molecular Weight Change: Analyze the molecular weight and distribution of the dried samples using Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC/GPC) [1] [8].

- Morphological Analysis: Use Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to visualize surface and bulk morphological changes, such as cracking or pore formation [7].

- Thermal Properties: Employ Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) to track changes in crystallinity, Tg, and Tm during degradation [7].

Protocol: Enzymatic Degradation Study (e.g., PCL with Lipase)

This protocol describes how to assess the accelerated degradation of a polymer like Poly(ε-caprolactone) using a specific enzyme.

1. Sample Preparation:

- Follow the same sample preparation and initial characterization steps as in the hydrolytic protocol.

2. Enzymatic Solution Preparation:

- Prepare a solution of a suitable enzyme in an appropriate buffer. For PCL, Lipase from Pseudomonas species is highly effective. Dissolve the enzyme in PBS (pH 7.4) to a final activity of, for example, 40 units/mg [7].

- Prepare a control group with the same buffer but without the enzyme (inactivated enzyme can also be used as a negative control).

3. Degradation Setup and Monitoring:

- Immerse samples in the enzymatic solution and control buffer. Incubate at 37°C with agitation.

- The degradation process is much faster. Monitor mass loss over a shorter timeframe (hours to days instead of weeks) [7].

- Analyze samples using the same techniques as the hydrolytic protocol (gravimetric analysis, GPC, SEM) to compare the extent and mechanism of degradation.

The following workflow summarizes the key steps for conducting a comparative degradation study:

Quantitative Data Comparison

The table below summarizes key quantitative differences and factors influencing hydrolytic and enzymatic degradation, using Poly(ε-caprolactone) as a model system.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Hydrolytic vs. Enzymatic Degradation Pathways

| Parameter | Hydrolytic Degradation | Enzymatic Degradation |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Passive chemical hydrolysis; can be autocatalytic [8] | Enzyme-catalyzed hydrolysis; specific binding [9] |

| Erosion Type | Predominantly Bulk Erosion [8] | Predominantly Surface Erosion [7] [9] |

| Degradation Rate | Slow (e.g., PCL: several years) [7] | Fast (e.g., PCL with Pseudomonas lipase: 4 days) [7] |

| Key Influencing Factors | • pH of medium [7]• Material crystallinity [8]• Polymer Tg & hydrophilicity [7] | • Presence & concentration of specific enzymes [7]• Enzyme accessibility (porosity, size) [9] |

| Mass Loss Profile | Little initial mass loss, followed by a rapid drop as bulk integrity is lost [7] | More linear and predictable mass loss over time [7] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Degradation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Standard hydrolytic degradation medium; simulates physiological pH and osmolarity [7] | Use at pH 7.4; requires regular refreshing to maintain pH stability. |

| Specific Enzymes | To catalyze and accelerate degradation for enzymatic pathway studies [7] [9] | Lipase (e.g., from Pseudomonas): for polyesters like PCL [7]. Proteases (e.g., for silk, collagen) [10] [9]. |

| Sodium Azide (NaN₃) | Biocide to prevent microbial growth in degradation media, which could confound results [7] | Typically used at 0.02-0.05% w/v. Handle with care as it is highly toxic. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | To measure the reduction in polymer molecular weight and distribution, confirming chemical degradation [1] [8] | Also known as Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC). Essential for tracking chain scission. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | To analyze thermal properties (Tg, Tm, crystallinity) that change during degradation [7] [8] | An increase in crystallinity often observed as amorphous regions degrade first. |

| Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) | To visualize physical surface erosion, cracking, and morphological changes [7] [1] | Provides visual evidence of bulk vs. surface erosion mechanisms. |

| 9-Hete | 9-Hete, CAS:70968-92-2, MF:C20H32O3, MW:320.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Physachenolide C | Physachenolide C, MF:C30H40O9, MW:544.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting a degradation pathway based on the polymer's properties and the experimental objectives:

Fundamental Degradation Mechanisms & Kinetics

How do the core functional groups in polymers influence their degradation kinetics?

The degradation behavior of biomaterials is primarily governed by the hydrolysis of key chemical functional groups within the polymer backbone or side chains. The rate of this hydrolysis, and thus the overall degradation kinetics, is determined by the chemical reactivity and accessibility of these groups. The table below summarizes the characteristics of the primary functional groups involved.

Table 1: Key Functional Groups and Their Degradation Profiles

| Functional Group | Chemical Reaction & Mechanism | Primary Degradation Mode | Representative Polymers/Biomaterials | General Degradation Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ester | Hydrolysis: Acid/Base-catalyzed cleavage into carboxylic acid and alcohol [1] [11]. | Bulk erosion (common) or surface erosion [11] [12]. | Polycaprolactone (PCL), Polylactic acid (PLA), Polyglycolic acid (PGA), Poly(ethylene carbonate) (PEC) [13] [11] [12]. | Moderate to Slow (Highly tunable via crystallinity, MW) [13]. |

| Anhydride | Hydrolysis: Rapid cleavage into two carboxylic acid molecules [1]. | Predominantly surface erosion [14]. | Anhydride-cured epoxy resins (ANH-EP), Polyanhydrides [14]. | Fast |

| Amide | Hydrolysis: Cleavage into carboxylic acid and amine; requires strong catalysts or enzymes [1]. | Bulk erosion (very slow) or enzymatic surface erosion [15] [1]. | Proteins (e.g., collagen), Nylon, Polyamides [1]. | Very Slow |

The degradation kinetics for these groups can often be described by mathematical models. For instance, the hydrolysis of ester bonds in polycaprolactone (PCL) has been successfully modeled using pseudo-first-order kinetics under assumptions of abundant water and ester groups [13]. Furthermore, for surface-eroding materials like anhydride-cured epoxy resins or certain polycarbonates, a core-shrinking model (CSM) is more appropriate [14] [12].

Table 2: Common Mathematical Models for Degradation Kinetics

| Kinetic Model | Equation | Best Suited For | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudo-First Order | Mn = Mnâ‚€ * e^(-k't) where k' = k[E][Hâ‚‚O] [13]. |

Bulk-eroding polymers (e.g., PCL, PLA) where water and ester groups are initially abundant [13]. | Molecular weight decrease is exponential. Rate constant k' is proportional to ester bond concentration [E] and water concentration [Hâ‚‚O]. |

| Core-Shrinking Model (SCM) | X = 1 - (V/V₀) = 1 - (xyz / L³) [14]. |

Surface-eroding polymers (e.g., anhydride-cured epoxy, PEC) where degradation is confined to the surface [14] [12]. | Mass loss is linear with time. The volume V of the undegraded core decreases as the surface recedes. |

| Korsmeyer-Peppas Model | α = k₄ * t⿠where α is fractional mass loss and n is the release exponent [11]. |

Analyzing mass loss data and determining the degradation mechanism (e.g., Fickian diffusion, relaxation-controlled) [11]. | The exponent n helps identify the transport mechanism. A shift to n ~1 indicates relaxation-controlled degradation. |

Diagram 1: Functional Group Degradation Pathways

Experimental Protocols for Kinetics Assessment

What are the standard experimental protocols for quantifying degradation kinetics?

A robust assessment of biodegradation requires a multi-faceted approach that monitors chemical, physical, and mechanical changes over time [1]. The following workflow outlines a generalized protocol for in vitro degradation studies, which should be adapted based on the specific polymer and application.

Diagram 2: Degradation Assessment Workflow

Detailed Protocol: Enzymatic Degradation of PCL-based Scaffolds [11]

This protocol provides a specific example of how to monitor ester bond hydrolysis.

- Scaffold Preparation: Prepare polymer scaffolds (e.g., via solvent casting, hot pressing). Record the initial dry weight (

W_i). - Degradation Media Preparation: Prepare a degradation medium such as 0.1 M Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) containing 500 µg/mL of lysozyme. Lysozyme is used to simulate enzymatic activity present in the biological environment.

- Incubation: Immerse the pre-weighed scaffolds in the degradation medium and incubate at 37°C for set durations (e.g., 7, 14, 28, 35 days). Use a constant media volume to sample mass ratio to ensure consistency.

- Sampling and Analysis:

- Gravimetric Analysis: At each time point, remove samples from the medium, rinse thoroughly with distilled water, and dry to a constant weight. Record the final dry weight (

W_f). - Calculate Mass Loss: Determine the percentage weight loss using:

W_loss% = [(W_i - W_f) / W_i] * 100[11]. - Thermal Analysis: Use Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) to track changes in crystallinity (

T_c) and melting temperature (T_m), which indicate whether degradation is occurring in the amorphous or crystalline regions [11].

- Gravimetric Analysis: At each time point, remove samples from the medium, rinse thoroughly with distilled water, and dry to a constant weight. Record the final dry weight (

- Kinetic Modeling: Fit the obtained mass loss or molecular weight data to various kinetic models (see Table 2) using software like MATLAB to determine the dominant degradation mechanism and calculate rate constants [11].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

What are common issues in degradation experiments and how can they be resolved?

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for Degradation Studies

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No significant mass loss observed over time. | Degradation medium pH is not optimal for hydrolysis. Polymer is highly crystalline, slowing water penetration. | Adjust pH to target specific catalytic conditions (e.g., acidic for acetal hydrolysis). Use enzymes (e.g., lipases, esterases) known to catalyze the reaction [12]. |

| Mass loss is mistaken for dissolution. | Polymer or additives are simply dissolving in the aqueous medium without chemical degradation [1]. | Confirm chemical degradation via GPC (to show molecular weight decrease) or NMR/FTIR (to show bond cleavage) [1]. |

| High variability in degradation rates between samples. | Inconsistent sample geometry or porosity. Poor control over medium temperature or agitation. Inadequate sample size (n) for statistical power. | Standardize fabrication to ensure consistent geometry and porosity. Use a temperature-controlled incubator with agitation. Increase sample size and include appropriate replicates. |

| Unexpected acceleration of degradation. | Presence of catalytic impurities or residues from synthesis. Autocatalysis due to accumulation of acidic byproducts in the polymer bulk [13]. | Purify polymers before use (e.g., re-precipitation). Increase the volume of degradation medium and refresh it periodically to remove acidic byproducts [13]. |

| Inability to fit data to standard kinetic models. | Degradation mechanism is complex, involving multiple simultaneous processes (e.g., simultaneous bulk and surface erosion). | Use a combination of models or a more complex empirical model. The Korsmeyer-Peppas model can be a good starting point to identify the dominant mechanism [11]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

What are the essential reagents and materials needed for these studies?

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | A standard isotonic buffer (pH 7.4) that mimics the salt composition and osmolarity of blood and other bodily fluids. Used as a basic hydrolysis medium [11]. | In vitro degradation studies of PCL scaffolds and other polyesters [11]. |

| Lysozyme | An enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of specific glycosidic bonds. Often used in degradation studies to simulate enzymatic activity present in vivo [11]. | Added to PBS to create an enzymatic degradation medium for studying scaffold erosion [11]. |

| Nanohydroxyapatite (nHA) | A bioactive ceramic that mimics the mineral component of bone. Used as a nanofiller to tune the degradation kinetics and mechanical properties of polymer composites [11]. | Incorporated into PCL scaffolds (PHAP) to alter crystallinity and shift degradation from diffusion-based to relaxation-driven [11]. |

| Vitamin E (VE) & Other Antioxidants | Compounds that scavenge Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS). Used to modify polymer end-groups or blend into matrices to delay oxidative degradation [12]. | Capping the terminal hydroxyl groups of Poly(ethylene carbonate) to slow down enzyme- and ROS-mediated surface erosion [12]. |

| Graphene Oxide Nanoscrolls (GONS) | Carbon-based nanofillers that can provide structural reinforcement, modulate degradation, and exhibit antioxidant properties [11]. | Combined with nHA in PCL composites (PGAP) to increase activation energy for degradation and provide ROS-scavenging capability [11]. |

| Gpr35 modulator 2 | Gpr35 modulator 2, MF:C28H23FN2O4, MW:470.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ganoderic Acid C6 | Ganoderic Acid C6, MF:C30H42O8, MW:530.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technical Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Biomaterial Degradation Experiments

Q1: My biomaterial is degrading too quickly in vitro. What could be the cause?

- Check enzyme concentration: High concentrations of proteolytic enzymes (e.g., ≥1 U/mL Proteinase K) can drastically accelerate mass loss. Verify and reduce enzyme activity units in your degradation buffer [16].

- Verify biomaterial cross-linking: Low crystalline content or insufficient cross-linking accelerates hydrolysis. For silk fibroin, ensure adequate water annealing time (e.g., >12 hours) to increase β-sheet content and slow degradation [16].

- Assess autocatalytic effect: Acidic degradation by-products can create an autocatalytic feedback loop. Incorporating even small amounts (e.g., 2 mol%) of acidic comonomers like methacrylic acid (MAA) significantly increases hydrolysis rates in polyesters; reduce or eliminate such components [17].

- Confirm pH conditions: Degradation media at neutral pH (7.4) is standard; acidic conditions accelerate hydrolysis of ester bonds in synthetic polymers. Check and adjust buffer pH [17].

Q2: I am observing inconsistent degradation rates between experimental batches. How can I improve reproducibility?

- Control initial material properties: Key parameters like polymer molecular weight, crystallinity, and porosity must be consistent. Use Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to characterize each batch [1] [16].

- Standardize degradation assessment method: Choose between continuous (samples remain in enzyme solution) or discrete (samples removed for analysis) methods and maintain consistency, as the method influences calculated rate constants [16].

- Ensure homogeneous enzyme distribution: Agitate degradation buffers to prevent enzyme settling and ensure uniform concentration throughout the solution.

- Validate analytical techniques: Combine multiple assessment methods (e.g., gravimetric analysis with molecular weight measurement via SEC) to confirm degradation, as mass loss alone can be misleading if material is dissolving rather than degrading [1].

Q3: How can I confirm that observed mass loss is due to degradation and not simply dissolution?

- Monitor molecular weight changes: Use Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) to detect a decrease in polymer molecular weight, confirming chain scission and true degradation, not just dissolution [1].

- Analyze chemical composition: Employ Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) to detect changes in functional groups (e.g., loss of ester bonds, appearance of carboxylic acids) [1].

- Characterize degradation by-products: Techniques like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) or Mass Spectrometry can identify and quantify small molecules (e.g., lactic acid, peptides) resulting from degradation [1].

- Combine gravimetric with chemical data: Cross-reference mass loss data with chemical analysis to confirm degradation [1].

Troubleshooting Biomaterial Processing and Scaffold Formation

Q4: My 3D-bioprinted scaffold lacks structural integrity and layers are merging. What should I do?

- Optimize bioink viscosity: Perform rheological tests to ensure sufficient viscosity and thixotropic behavior (shear-thinning) for layer stacking. Adjust polymer concentration or incorporate viscosity-enhancing agents [18].

- Increase crosslinking rate: Optimize crosslinking method and time. For photocrosslinking, ensure appropriate wavelength and intensity. For ionic crosslinking, optimize crosslinker concentration to ensure the bottom layer stabilizes before the next is deposited [18].

- Adjust printing parameters: Reduce printing speed to allow more time for deposited struts to stabilize before the next layer is applied [18].

Q5: I am experiencing frequent needle clogging during bioprinting. How can I resolve this?

- Ensure bioink homogeneity: Centrifuge bioink at low RPM (e.g., 30 seconds) to remove air bubbles and prevent phase separation that can lead to clogging [18].

- Check particle size: When using nanoparticles, ensure their size is smaller than the needle gauge diameter. Pre-characterize particle size using SEM and ensure homogeneous dispersion to prevent agglomeration [18].

- Adjust needle gauge and pressure: Increase pressure temporarily to clear minor clogs (for acellular inks). If clogging persists, switch to a larger needle gauge. When working with cells, limit pressure to 2 bar to maintain viability [18].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: In Vitro Enzymatic Degradation of Protein-Based Biomaterials

Purpose: To quantitatively determine the degradation profile of a protein-based biomaterial (e.g., silk fibroin sponge) under simulated physiological conditions [16].

Reagents:

- Proteinase K or Protease XIV enzyme

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Lyophilized biomaterial scaffolds

Procedure:

- Pre-degradation characterization: Weigh initial dry mass (Wâ‚€) of scaffolds (n=3). Characterize initial molecular weight and chemical structure via SEC and FTIR [1] [16].

- Prepare degradation solution: Dilute enzyme to desired concentration (e.g., 0.01, 0.1, 1.0 U/mL) in PBS. Include enzyme-free PBS controls.

- Initiate degradation: Immerse each scaffold in 1-5 mL of degradation solution. Incubate at 37°C with gentle agitation.

- Monitor degradation:

- Post-degradation analysis:

- Kinetic modeling: Fit mass loss data to a modified first-order kinetic model to determine degradation rate constants [16].

Protocol: Tuning Degradation Rate via Acidic Comonomer Incorporation

Purpose: To modulate the degradation rate of a thermally responsive hydrogel (e.g., poly(NIPAAm-based) by incorporating acidic commoners to exploit the autocatalytic effect [17].

Reagents:

- N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAAm)

- 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA)

- Methacrylate-polylactide (MAPLA)

- Methacrylic acid (MAA)

- Benzoyl peroxide (BPO) initiator

- 1,4-dioxane solvent

Procedure:

- Copolymer synthesis: Synthesize poly(NIPAAm-co-HEMA-co-MAPLA-co-MAA) (pNHMMj) via free radical polymerization. Vary MAA feed ratio (j = 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10 mol%) while keeping total monomer concentration constant [17].

- Polymer characterization: Confirm copolymer structure and composition using ¹H NMR. Determine molecular weight and polydispersity via GPC [17].

- Hydrogel formation: Dissolve copolymers in PBS (e.g., 15 wt%) to form hydrogels via thermal gelation at 37°C [17].

- Degradation study:

- Incubate pre-weighed hydrogels in PBS at 37°C.

- At scheduled time points, remove samples, lyophilize, and record dry mass.

- Measure pH of supernatant to track acid generation.

- Analysis: Plot mass loss over time and correlate with MAA content. Rheology can be used to monitor changes in mechanical properties during degradation [17].

Quantitative Data & Kinetic Analysis

Biomaterial Degradation Rate Constants

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Rate Constants for Enzymatic Degradation of Lyophilized Silk Sponges [16]

| Enzyme | Enzyme Concentration (U/mL) | Water Annealing Time (Hours) | Modified First-Order Rate Constant (k, dayâ»Â¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteinase K | 1.0 | 2 | 0.210 |

| Proteinase K | 1.0 | 12 | 0.035 |

| Proteinase K | 0.1 | 2 | 0.070 |

| Proteinase K | 0.01 | 2 | 0.015 |

| Protease XIV | 1.0 | 2 | 0.180 |

| Protease XIV | 0.1 | 2 | 0.055 |

Tuning Hydrogel Degradation via Composition

Table 2: Effect of Acidic Comonomer (MAA) on Hydrogel Degradation Duration [17]

| MAA Content (mol%) | Time to Complete Mass Loss (Days) | Key Degradation Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | >150 (≈5 months) | Slow, linear degradation profile |

| 0.5 | ≈90 | -- |

| 1 | ≈60 | -- |

| 2 | ≈30 | Rapid onset, autocatalytic behavior |

| 5 | ≈7 | -- |

| 10 | ≈1 | -- |

Standard Methods for Assessing Biomaterial Degradation

Table 3: Comparison of Biomaterial Degradation Assessment Techniques [1]

| Assessment Method | What It Measures | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gravimetric Analysis | Mass loss over time | Simple, cost-effective, quantitative | Does not distinguish dissolution from degradation; requires drying |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Change in molecular weight | Confirms polymer chain scission (true degradation) | Requires soluble fragments; specialized equipment |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Surface morphology, erosion | Visualizes structural changes; high resolution | Qualitative; sample preparation may alter morphology |

| Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) | Chemical bond cleavage | Identifies functional group changes | May not detect early-stage degradation |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Molecular structure of by-products | Detailed chemical structure information | Expensive; requires specialized expertise |

| Mass Spectrometry | Identification of degradation products | High sensitivity for small molecules | Complex data interpretation |

Signaling Pathways & Experimental Workflows

Inflammation-Mediated ECM Remodeling Pathway

Inflammation-Mediated ECM Remodeling Pathway

Biomaterial Degradation Experiment Workflow

Biomaterial Degradation Experiment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for ECM and Biomaterial Degradation Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteolytic Enzymes | Proteinase K, Protease XIV, Collagenase, α-Chymotrypsin | Simulate enzymatic degradation of protein-based biomaterials; study degradation kinetics | Concentration range typically 0.01-1.0 U/mL; activity varies by enzyme source [16] |

| Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) | Collagenase (MMP-1, MMP-8, MMP-13), Gelatinase (MMP-2, MMP-9), Stromelysin (MMP-3, MMP-10) | Study physiological ECM remodeling; investigate specific cleavage of collagen, gelatin, proteoglycans | Specific inhibitors (TIMPs) available for mechanistic studies [19] [20] |

| Crosslinking Agents | Glutaraldehyde, Genipin, EDC/NHS, Transglutaminase | Modulate biomaterial stability and degradation rate by increasing crosslink density | Crosslinking degree inversely correlates with degradation rate; optimize for target application [16] |

| pH-Sensitive Dyes | LysoSensor Yellow/Blue DND-160 | Monitor internal pH of degrading biomaterials; detect autocatalytic effect in polyesters | Useful for visualizing spatial pH gradients within bulk materials [17] |

| Degradation Buffers | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), Tris-HCl, Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) | Provide physiological ionic strength and pH (typically 7.4) for in vitro degradation studies | Include antimicrobial agents (e.g., sodium azide) for long-term studies to prevent microbial growth [1] |

| Characterization Standards | Poly(methyl methacrylate) for GPC, pH calibration standards | Calibrate instruments for accurate molecular weight and pH measurement | Essential for quantitative comparison between studies [17] [16] |

| NSC-217913 | NSC-217913, CAS:79100-27-9, MF:C9H8Cl2N4O2S, MW:307.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Calcium Stearate | Calcium Stearate, CAS:66071-81-6, MF:C36H70O4.Ca, MW:607.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Comparative Degradation Data

The following table summarizes the key degradation characteristics and performance thresholds for polymers, metals, and ceramics, which are critical for biomaterial selection.

| Material Class | Primary Degradation Mechanisms | Typical Service Temperature Limits | Key Degradation-Limiting Properties | Susceptible Environments/Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymers | Hydrolysis, Oxidation, Chain Scission, UV Degradation, Wear [21] [22] | 150°C - 350°C (High-performance polymers like PEEK, Polyimides) [21] | Low thermal stability, Time-dependent deterioration of mechanical properties [21] [23] | Hydrolytic solutions (pH changes), Enzymes, UV radiation, Abrasive media [24] [22] |

| Metals | Corrosion (Uniform, Pitting, Galvanic), Stress Corrosion Cracking, Fatigue, Creep [23] [22] [25] | Varies by alloy; can be limited by oxidation and creep at high temperatures [25] | Susceptibility to electrochemical reactions, Microstructural changes [23] [25] | Chloride ions (saltwater), Acids, Dissimilar metals, Tensile stress + corrosive environment [22] [25] |

| Ceramics | Dissolution in aggressive environments, Slow corrosion, Wear, Thermal Shock, Fracture [21] [23] | >1000°C (e.g., Silicon Carbide, Alumina can exceed 1600°C) [21] | Inherent brittleness, Low fracture toughness, Complex manufacturing [21] | Extreme pH, Fluorides, Thermal cycling, Impact/point loads [21] [23] |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Biomaterial Degradation

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments to characterize biomaterial degradation in vitro.

Gravimetric Analysis for Mass Loss

Objective: To quantify the rate of mass loss of a solid biomaterial formulation due to degradation in simulated body fluid.

Materials:

- Test Specimens: Pre-weighed biomaterial samples (e.g., polymer scaffolds, metal coupons, ceramic discs).

- Degradation Media: Simulated body fluid (SBF), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), or other relevant buffered solutions at pH 7.4 [24].

- Equipment: Analytical balance (precision ±0.1 mg), sterile incubation containers, oven, pH meter.

Procedure:

- Pre-degradation Assessment: Dry samples to a constant weight (Wâ‚€). Record initial dimensions and document morphology via photography or scanning electron microscopy (SEM) [24].

- Immersion: Immerse each sample in a sufficient volume of degradation media (typically 20:1 media-to-sample volume ratio) in a sterile container. Maintain at 37°C [24].

- Sampling: At predetermined time points, remove samples from the incubation environment (n=3 recommended).

- Rinsing and Drying: Gently rinse samples with deionized water to remove salts and media. Dry samples to a constant weight (Wₜ) [24].

- Analysis: Calculate the percentage mass loss at each time point:

Mass Loss (%) = [(W₀ - Wₜ) / W₀] * 100. Plot mass loss versus time to determine degradation kinetics.

Monitoring Molecular Weight Change via Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)

Objective: To confirm degradation by tracking the reduction in the average molecular weight of a polymeric biomaterial.

Materials:

- Test Specimens: Degrading polymer samples from the gravimetric study.

- Equipment: Size Exclusion Chromatography system with refractive index detector.

- Reagents: Appropriate solvent for the polymer (e.g., Tetrahydrofuran for PLGA), narrow dispersity polymer standards for calibration.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: At each time point, dissolve a portion of the degraded polymer sample in the SEC solvent at a known concentration. Filter the solution through a 0.2 µm membrane.

- SEC Analysis: Inject the sample into the SEC system. Use the calibrated system to determine the number-average molecular weight (Mâ‚™) and weight-average molecular weight (Mð“) [24].

- Analysis: Plot Mâ‚™ and Mð“ versus time. A steady decrease confirms bulk degradation through chain scission.

Electrochemical Analysis for Metallic Corrosion

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the corrosion rate and susceptibility of a metallic biomaterial.

Materials:

- Test Specimen: Metal sample with a known exposed surface area, connected as a working electrode.

- Equipment: Potentiostat, standard three-electrode electrochemical cell (working, reference, counter electrode).

- Reagents: Electrolyte solution simulating the physiological environment (e.g., Ringer's solution).

Procedure:

- Setup: Immerse the electrochemical cell in the electrolyte at 37°C. Allow the system to stabilize until the open-circuit potential is steady.

- Potentiodynamic Polarization: Scan the potential of the working electrode from approximately -250 mV to +250 mV relative to the open-circuit potential at a slow scan rate (e.g., 0.5 mV/s) [23].

- Analysis: Use the Tafel extrapolation method on the resulting current-potential plot to determine the corrosion current density (i_corr), which is directly proportional to the corrosion rate.

Experimental Workflow and Material Selection

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting a material class based on application requirements and subsequently characterizing its degradation.

Troubleshooting FAQs for Degradation Experiments

Q1: My polymer samples are losing mass in PBS much faster than expected. How can I determine if this is true degradation or just dissolution?

A: This is a common issue. Mass loss alone is not conclusive proof of degradation [24]. To confirm:

- Chemical Analysis: Use Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) to monitor changes in molecular weight. A decrease confirms chain scission (degradation), whereas dissolution would not alter the molecular weight [24].

- Analyze By-products: Employ techniques like Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) or Mass Spectrometry to identify and quantify the chemical by-products in the degradation media. The presence of monomeric or oligomeric units confirms degradation [24].

- Surface Morphology: Examine the sample surface with Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). Surface erosion, cracking, or pitting indicates degradation, while a smooth surface may suggest dissolution.

Q2: We are observing catastrophic, unexpected failures in our metallic implant prototypes during cyclic loading tests in a simulated physiological environment. What could be the cause?

A: This failure mode strongly suggests Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC) [22] [25]. This occurs due to the combined action of tensile stress (applied or residual from manufacturing) and a corrosive environment.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Fractography: Examine the fracture surface with SEM. SCC often leaves a characteristic "cleavage" or "brittle" appearance, even in ductile metals, with possible secondary cracking [26].

- Review Stresses: Analyze the component design and manufacturing history (e.g., welding, heat treatment) for sources of tensile stress. Finite element analysis can identify stress concentrations.

- Material Selection: Consider switching to a metal alloy known for high resistance to SCC in chloride environments (e.g., titanium alloys vs. some stainless steels) [22].

- Environmental Control: If possible, modify the environment with corrosion inhibitors to reduce its aggressiveness.

Q3: Our ceramic component shattered during sterilization and subsequent rapid cooling. Why did this happen?

A: This is a classic case of failure due to thermal shock [21]. Ceramics generally have low fracture toughness and are brittle. A rapid temperature change creates internal thermal stresses because different parts of the component expand or contract at different rates. If these stresses exceed the material's strength, fracture occurs.

- Preventive Measures:

- Select a Ceramic with High Thermal Shock Resistance: Materials like Silicon Carbide (SiC) generally have better thermal shock resistance than Alumina [21].

- Control the Thermal Ramp Rates: Implement slower and more controlled heating and cooling cycles during sterilization and processing.

- Design Modifications: Avoid sharp corners and thick cross-sections in your design, as these act as stress concentrators and exacerbate thermal shock failure.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and reagents used in the fabrication and degradation testing of biomaterials, as featured in the cited research.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Application in Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Precursors (e.g., Methyl Silsesquioxane - MK) | Serves as a pre-ceramic polymer for fabricating polymer-derived ceramics (PDCs) via pyrolysis [27]. | Used in synthesizing Silicon Oxycarbide (SiOC) ceramics for high-temperature sensing applications [27]. |

| Metal Salts (e.g., Titanium Acetylacetonate, Cobalt Nitrate) | Acts as a source of metal ions to modify the properties of ceramic precursors (e.g., SiOC) [27]. | Doping SiOC with Ti, Co, or Fe to enhance graphitization, electrical conductivity, and piezoresistive performance [27]. |

| Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) / Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Provides an in vitro environment that mimics the ionic composition and pH of human blood plasma for degradation studies [24]. | Standard immersion media for assessing the corrosion of metals or the hydrolytic degradation of polymers over time [24]. |

| Enzymatic Solutions (e.g., Lysozyme) | Used to simulate the enzymatic activity present in the biological environment, which can accelerate polymer degradation [24]. | Added to degradation media to study the enzymatic hydrolysis of specific polymers (e.g., polyesters) for biomedical applications. |

| Purging Compounds / Heat Stabilizers | Used in polymer processing to prevent thermal and oxidative degradation of the polymer melt during shutdown and start-up cycles of equipment like extruders [28]. | Preventing the formation of degraded, cross-linked "black specks" in thermoplastic extrusion, which can lead to defective products [28]. |

| FT113 | FT113, MF:C22H20FN3O4, MW:409.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| GK420 | GK420, MF:C20H25NO5S, MW:391.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Engineering Degradation Profiles: Material Design, Synthesis, and Application-Specific Strategies

Selecting a biomaterial with the correct degradation rate is a critical determinant for the success of medical implants, tissue engineering scaffolds, and drug delivery systems. The ideal biomaterial must maintain its mechanical integrity for the required duration of the healing or treatment process and then safely degrade, eliminating the need for a second surgical removal. This guide provides a structured approach and practical methodologies for researchers to match a material's degradation profile to a specific clinical application timeline.

FAQs: Degradation Rate Fundamentals

1. What is the fundamental difference between bioresorbable, biodegradable, and non-degradable materials?

- Bioresorbable/Biodegradable Materials: These are designed to break down in vivo into harmless by-products that are metabolized or excreted by the body. They are used for temporary support, such as in sutures, bone fixation devices, and tissue engineering scaffolds. Examples include polylactic acid (PLA), polyglycolic acid (PGA), and certain magnesium alloys [29] [30].

- Non-degradable Materials: These are intended to remain stable and intact in the body for long-term or permanent applications. They are used in permanent implants like artificial joints and dental fixtures. Examples include titanium, stainless steel, and cobalt-chromium alloys [31].

2. Why is matching the degradation rate to the clinical timeline so important?

A mismatch can lead to clinical failure. If a material degrades too quickly, it can lose mechanical strength before the tissue has sufficiently healed, leading to structural failure. If it degrades too slowly, it can impede the healing process, cause chronic inflammation, or necessitate a secondary surgery for removal [1] [32]. The degradation time should ideally match the healing or regeneration process [1].

3. What are the key material properties that control the degradation rate?

Degradation is influenced by a combination of material properties, including:

- Chemical Composition: The presence of hydrolytically or enzymatically cleavable bonds (e.g., ester, amide, anhydride) [1].

- Crystallinity: More crystalline regions are typically more resistant to degradation than amorphous regions.

- Molecular Weight: Higher molecular weight generally correlates with a slower degradation rate.

- Porosity and Surface-to-Volume Ratio: Higher porosity and surface area can accelerate degradation by allowing greater fluid penetration [32].

- Hydrophilicity/Hydrophobicity: Hydrophilic materials tend to absorb more water, which can accelerate hydrolysis.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Degradation Rate Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Degradation is too rapid | Material is too hydrophilic; high amorphous content; high porosity; low molecular weight. | Increase material crystallinity; select a more hydrophobic polymer; increase molecular weight; use a composite material to control fluid uptake [33]. |

| Degradation is too slow | Material is highly crystalline or hydrophobic; very high molecular weight; dense, non-porous structure. | Incorporate more hydrolytically unstable linkages (e.g., from PLA to PLGA); increase material porosity; apply surface treatments (e.g., plasma) to increase hydrophilicity [33]. |

| Inconsistent degradation between samples | Inconsistent material synthesis (e.g., variable molecular weight); poor control over scaffold porosity/morphology; non-uniform sterilization. | Standardize synthesis and processing protocols; use characterization techniques (e.g., SEC, SEM) to ensure batch-to-batch consistency; validate sterilization methods [1]. |

| Unexpected inflammatory response | Release of acidic or toxic degradation by-products; rapid degradation generating a high local concentration of fragments. | Select materials that degrade into natural metabolites (e.g., lactic acid); buffer the local environment; control degradation to a slower, more consistent rate [1] [29]. |

Quantitative Data for Material Selection

The following tables summarize key properties of common biodegradable materials to aid in initial screening.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Common Biodegradable Polymer Classes

| Polymer Class | Example Materials | Typical Degradation Time | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Key Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyesters | PLA, PCL, PLGA | 6 months - 2+ years [33] | 10 - 60 | Sutures, bone fixation, GBR membranes, drug delivery [29] [30] |

| Polyanhydrides | - | Days - Months | Low | Drug delivery (primarily) |

| Polyorthoesters | - | Adjustable: Days - Months | Low | Drug delivery |

| Natural Polymers | Collagen, Chitosan | Days - Weeks (can be crosslinked) | Low - Medium | Wound healing, hemostats, soft tissue engineering |

Table 2: Degradation Rate and Mechanical Properties of Biodegradable Alloys

| Alloy Type | Tensile Strength Pattern (High to Low) | Degradation Rate Pattern (Fast to Slow) | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Biodegradable Medium Entropy (NBME) | Highest [31] | Moderate | Permanent implants |

| Biodegradable High Entropy (BHE) | High [31] | Slow | Orthopedic implants |

| Biodegradable Medium Entropy (BME) | Medium [31] | Fastest [31] | Orthopedic implants |

| Biodegradable Low Entropy (BLE) | Lower [31] | Slowest [31] | Orthopedic implants |

Standard Experimental Protocols for Degradation Assessment

Accurately characterizing degradation is essential. The following protocols are based on standard practices and ASTM guidelines [1].

Protocol 1: In Vitro Hydrolytic Degradation Study

Objective: To assess the mass loss, molecular weight changes, and morphological changes of a biomaterial under simulated physiological pH conditions.

Materials:

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Incubator or water bath maintained at 37°C

- Analytical balance (precision ±0.1 mg)

- Freeze dryer

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) system

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

Method:

- Pre-degradation characterization: Record the initial dry mass (W₀), molecular weight (Mₙ₀), and take SEM images of the material.

- Immersion: Immerse the samples in PBS and maintain at 37°C. Ensure the sample-to-solution volume ratio is sufficient.

- Sampling: At predetermined time points (e.g., 1, 4, 12 weeks [33]), remove samples from the solution in triplicate.

- Post-degradation processing:

- Rinse samples with deionized water and dry to a constant mass.

- Weigh the dry mass (Wₜ).

- Analyze molecular weight (Mₙₜ) via SEC.

- Image the surface morphology via SEM.

- Calculations:

- Mass Loss (%) = [(W₀ - Wₜ) / W₀] × 100

- Molecular Weight Retention (%) = (Mₙₜ / Mₙ₀) × 100

Protocol 2: Surface Modification to Accelerate Degradation

Objective: To increase the surface hydrophilicity of a slow-degrading polymer (e.g., PCL, PLA) to accelerate its degradation rate [33].

Materials:

- Electrospun or fabricated polymer membrane

- Atmospheric-pressure non-thermal argon plasma system

Method:

- Pre-treatment characterization: Measure the water contact angle of the polymer surface to confirm hydrophobicity.

- Plasma treatment: Place the polymer membrane in the plasma chamber. Treat the surface with argon plasma for a defined period (e.g., 1-10 minutes). The optimal time should be determined empirically.

- Post-treatment characterization: Re-measure the water contact angle to confirm the shift to a hydrophilic surface.

- Degradation study: Subject the treated and untreated control samples to Protocol 1. The treated samples should show a significantly faster rate of mass loss and molecular weight reduction due to enhanced water penetration.

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Degradation Assessment Workflow

Biomaterial Selection Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Degradation Studies

| Item | Function in Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | A tunable polymer scaffold; degradation rate is controlled by the LA:GA ratio. | A higher glycolide content generally increases the degradation rate. |

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | A slow-degrading polymer used as a base material for long-term implants. | Often modified (e.g., with plasma [33]) to increase its degradation rate. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Standard immersion medium for simulating the ionic strength and pH of the body. | Does not contain enzymes; represents a baseline hydrolytic degradation. |

| Collagenase (Enzyme) | Used in enzymatic degradation studies to simulate the active biological environment. | Concentration and activity must be standardized for reproducible results. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | The primary method for tracking changes in molecular weight distribution over time. | Essential for confirming degradation beyond simple mass loss [1]. |

| Atmospheric-Pressure Plasma System | A tool for surface modification to increase polymer hydrophilicity and degradation rate [33]. | Treatment time is a key parameter to optimize for the desired effect. |

| Lumigen APS-5 | Lumigen APS-5, MF:C21H15ClNNa2O4PS, MW:489.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| MMP-9-IN-9 | MMP-9-IN-9, MF:C27H33N3O5S, MW:511.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In the field of biomaterials, particularly for orthopaedic applications and drug delivery, controlling the degradation rate of polymers is paramount to ensuring therapeutic success. Biodegradation is the process of breaking down large molecules into smaller ones with or without the aid of catalytic enzymes, playing a crucial role in the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) profile of biomaterials within the body [1]. The ideal biodegradable biomaterial must balance multiple requirements: its degradation time should match the healing or regeneration process, its mechanical properties should be appropriate for the intended application, and its degradation by-products must be non-toxic and readily cleared from the body [1]. This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers troubleshooting challenges in achieving precise degradation control through monomer selection, cross-linking density, and crystallinity management.

Core Principles of Degradation Control

The Interplay of Material Properties and Degradation

The degradation of biomaterials occurs through three interconnected processes—physical, chemical, and mechanical changes—that can be monitored to assess degradation progress [1]. The key to controlled breakdown lies in understanding how fundamental material properties influence the rate at which this occurs:

- Monomer Chemistry: The specific functional groups present in the polymer backbone (e.g., ester, ether, amide, imide, thioester, and anhydride) determine the susceptibility to hydrolytic or enzymatic cleavage [1].

- Cross-linking Density: Higher cross-linking densities typically create more tightly bound network structures that slow down degradation rates and enhance mechanical properties [34].

- Crystallinity: Crystalline regions in polymers are more resistant to hydrolysis and enzymatic attack than amorphous regions, providing a means to tune degradation profiles [34].

Quantitative Property Relationships

The following table summarizes how these key parameters interact to control the degradation behavior of polymeric biomaterials:

Table 1: Key Polymer Properties and Their Impact on Degradation

| Property | Impact on Degradation Rate | Effect on Mechanical Strength | Common Characterization Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Hydrolytically-Unstable Monomers (e.g., anhydrides) | Increased | Decreased | FTIR, NMR [1] |

| High Cross-linking Density | Decreased | Increased | Sol-gel fraction analysis, DMA [34] |

| High Crystallinity | Decreased | Increased | DSC, XRD [34] |

| Higher Surface Area to Volume Ratio | Increased | Minimal direct effect | SEM, Micro-CT [1] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ: Degradation Rate Issues

Q1: My polymer is degrading too quickly for my target application. What approaches can I use to slow down degradation?

- A1: Several strategies can slow degradation:

- Increase cross-linking density: Enhance network formation using higher cross-linker ratios or optimized curing conditions [34].

- Select less hydrolytically susceptible monomers: Replace ester groups with more stable amide or ether linkages where possible [1].

- Increase crystallinity: Adjust processing conditions (annealing, slow precipitation) to enhance crystalline domains [34].

- Utilize hydrophobic monomers: Reduce water penetration into the polymer matrix by incorporating hydrophobic segments [1].

Q2: The mechanical properties of my biodegradable scaffold are insufficient, but when I strengthen it, the degradation profile changes unfavorably. How can I balance these properties?

- A2: This common challenge requires a multi-faceted approach:

- Create composite materials: Combine a slow-degrading structural polymer with a faster-degrading component to maintain mechanical integrity during initial healing phases [31].

- Graduated cross-linking: Implement regions of varying cross-link density to create mechanical strength where needed while maintaining appropriate overall degradation [34].

- Explore entropy-controlled alloys: Recent research indicates biodegradable medium-entropy (BME) and high-entropy (BHE) alloys may offer favorable strength-degradation profiles [31].

Q3: I'm observing inconsistent degradation results between experimental batches. What could be causing this variability?

- A3: Inconsistent degradation often stems from:

- Inadequate characterization of starting materials: Thoroughly characterize molecular weight, polydispersity, and functional group concentration before processing [1].

- Variations in processing conditions: Strictly control temperature, humidity, and curing time during synthesis [35].

- Inadequate degradation monitoring: Employ multiple complementary assessment techniques rather than relying on a single method [1].

Degradation Assessment Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standardized workflow for assessing biomaterial degradation, as guided by ASTM recommendations:

Diagram 1: Standard Degradation Assessment Workflow (ASTM-guided)

Experimental Protocols for Degradation Analysis

Standardized In Vitro Degradation Testing

Protocol 1: Gravimetric Analysis for Degradation Monitoring

Purpose: To quantify mass loss of polymeric biomaterials during degradation studies [1].

Materials:

- Polymer samples (pre-dried to constant weight)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4, or simulated body fluid

- Constant temperature incubator (37°C)

- Analytical balance (precision of 0.1% of sample weight)

- Vacuum desiccator

Procedure:

- Pre-weigh dried samples (Wâ‚€) to the specified precision.

- Immerse samples in degradation medium at a ratio of 1:20 (sample volume:medium volume).

- Maintain at 37°C under gentle agitation.

- At predetermined time points, remove samples, rinse gently with deionized water, and dry under vacuum to constant weight.

- Record dry weight (Wₜ).

- Calculate mass loss percentage: [(W₀ - Wₜ)/W₀] × 100.

Troubleshooting Note: Gravimetric analysis alone may mistake material solubility for degradation; always complement with chemical analysis to confirm breakdown products [1].

Cross-linking Density Optimization

Protocol 2: Controlling Cross-linking for Targeted Degradation

Purpose: To establish a correlation between cross-linking density and degradation rate.

Materials:

- Base polymer (e.g., polyethylene, collagen, chitosan)

- Cross-linking agent (peroxide, silane, or physical irradiation source)

- Rheometer or dynamic mechanical analyzer (DMA)

- Soxhlet extraction apparatus

Procedure:

- Prepare polymer samples with varying cross-linker concentrations (e.g., 0.5%, 1%, 2%, 5%).

- Apply cross-linking conditions appropriate to your system (thermal, chemical, or irradiation).

- Determine sol-gel fraction to quantify effective cross-linking.

- Characterize mechanical properties via DMA to determine storage modulus.

- Subject samples to standard degradation conditions as in Protocol 1.

- Correlate cross-linking density with degradation rate constants.

Technical Note: Chemical cross-linking using peroxides or silane coupling agents creates covalent networks, while irradiation cross-linking offers an environmentally friendly alternative without introducing low-molecular-weight chemicals [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Controlled Degradation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Degradation Studies | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Simulates physiological pH conditions for hydrolysis studies | Maintain at pH 7.4; include antimicrobial agents for long-term studies [1] |

| Enzyme Solutions (e.g., esterases, collagenases) | Models enzymatic degradation pathways | Concentration should reflect physiological levels for target tissue [1] |

| Peroxide Cross-linkers (e.g., Dicumyl peroxide) | Chemical cross-linking to control network density | Decomposes to form free radicals that create carbon-carbon bonds between chains [34] |

| Silane Coupling Agents (e.g., A171, A151) | Chemical cross-linking with organofunctional groups | Forms Si-O-Si networks; particularly effective in moisture-cured systems [34] |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Standards | Molecular weight distribution monitoring | Critical for confirming degradation by tracking molecular weight reduction [1] |

| Biodegradable Entropy Alloys (BLE, BME, BHE) | Novel metallic biomaterials with tunable degradation | BME alloys show promising balance of tensile strength and degradation rate [31] |

| Habenariol | Habenariol, CAS:216752-89-5, MF:C22H26O7, MW:402.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| AVN-322 free base | AVN-322 free base, MF:C17H19N5O2S, MW:357.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Technical Guide: Interpreting Degradation Data

Relationship Between Material Class and Degradation Profile

Different classes of biomaterials exhibit characteristic degradation patterns that researchers should recognize when troubleshooting:

Table 3: Degradation Characteristics by Material Class

| Material Class | Typical Degradation Pattern | Representative Tensile Strength Range | Key Degradation Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-biodegradable Medium Entropy (NBME) Alloys | Minimal degradation | Highest | Corrosion (very slow) [31] |

| Biodegradable High Entropy (BHE) Alloys | Slow, controlled degradation | High | Galvanic corrosion [31] |

| Biodegradable Medium Entropy (BME) Alloys | Moderate to fast degradation | Medium | Uniform corrosion [31] |

| Biodegradable Low Entropy (BLE) Alloys | Slow degradation | Lowest | Surface erosion [31] |

| Highly Cross-linked Polymers | Surface erosion | High | Hydrolysis at cross-links [34] |

| Semicrystalline Polyesters | Bulk erosion, faster in amorphous regions | Medium | Hydrolysis of ester bonds [1] |

Decision Framework for Material Selection

The following diagram provides a systematic approach to selecting and optimizing biomaterials based on target degradation requirements:

Diagram 2: Biomaterial Selection Based on Degradation Requirements

Achieving precise control over biomaterial degradation requires careful consideration of monomer selection, cross-linking density, and crystallinity in an integrated framework. By implementing the systematic troubleshooting approaches, standardized protocols, and decision frameworks outlined in this technical support guide, researchers can more effectively design biomaterials with degradation profiles tailored to specific clinical applications. Future advancements in this field will likely focus on real-time degradation monitoring and smart materials that respond to physiological cues, further enhancing our ability to match biomaterial breakdown with biological healing processes.

Troubleshooting Guide: 3D-Printed Scaffolds for Degradation Control

Q1: My 3D-printed bone tissue scaffolds are degrading too slowly for the target application. What structural parameters can I adjust to accelerate degradation without compromising mechanical integrity?

A: Research demonstrates that scaffold lay-up pattern is a critical, material-independent parameter for controlling degradation kinetics. A study on Polyethylene terephthalate glycol (PETG) bone-tissue scaffolds revealed that altering the lay-up pattern from a standard 0/90° orientation to a 0/60/120° pattern can increase the degradation rate by up to 50% while maintaining the compressive modulus [36]. This is attributed to variations in the printing path length, crystallinity, and fiber contact points introduced by the optimized lay-up pattern [36].

Table 1: Structural Parameters for Tuning Scaffold Degradation Rate

| Parameter | Effect on Degradation Rate | Mechanical Trade-off | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lay-up Pattern [36] | Can increase by up to 50% | Minimal impact on compressive modulus | Use 0/60/120 or 0/45 patterns instead of 0/90. |

| Porosity & Pore Size [37] | Higher porosity/larger pores increase rate | Can reduce compressive/tensile strength | Design hierarchical porosity (macro/micro/nano). Aim for >300µm pore size for enhanced vascularization. |

| Material Composition [38] | Blending polymers (e.g., CS with PCL) tailors rate. | Blending can significantly enhance mechanical strength. | Use polymer blends and cross-linking for a balanced profile. |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Degradation Kinetics of 3D-Printed Scaffolds

- Objective: To quantify the in vitro degradation profile of a 3D-printed scaffold.

- Materials: 3D-printed scaffold, Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) at pH 7.4 or simulated body fluid, analytical balance, incubator maintained at 37°C, and characterization equipment (e.g., SEM, FTIR, SEC) [1].

- Procedure:

- Pre-degradation Analysis: Weigh each scaffold (Wi), record initial dimensions, and characterize initial morphology (SEM), chemical structure (FTIR), and mechanical properties [1].

- Immersion: Immerse each scaffold in a sufficient volume of degradation medium and place in an incubator at 37°C [1].

- Sampling: At predetermined time points, remove scaffolds from the medium (in triplicate).

- Post-degradation Analysis:

- Gravimetric Analysis: Rinse samples, dry to constant weight, and record final weight (Wf). Calculate mass loss:

(Wi - Wf)/Wi * 100%[1]. - Morphological Analysis: Use SEM to visualize surface erosion, pore structure changes, and crack formation [37].

- Chemical Analysis: Use FTIR to identify chemical bond cleavage and SEC to track changes in molecular weight, which confirms degradation beyond simple dissolution [1].

- Gravimetric Analysis: Rinse samples, dry to constant weight, and record final weight (Wf). Calculate mass loss:

- Mechanical Testing: Periodically assess compressive modulus and strength to correlate degradation with mechanical performance [36] [37].

Diagram Title: Biomaterial Degradation Assessment Workflow

Troubleshooting Guide: Electrospinning for Biomedical Applications

Q2: My electrospun chitosan (CS) nanofiber scaffolds dissolve too rapidly in aqueous environments, losing their fibrous structure. How can I improve their stability for wound healing applications?