Sensitivity Analysis in Computational Biomaterial Models: Enhancing Predictive Power for Biomedical Applications

This article explores the critical role of sensitivity studies in improving the reliability and predictive power of computational models for biomaterial design and evaluation.

Sensitivity Analysis in Computational Biomaterial Models: Enhancing Predictive Power for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article explores the critical role of sensitivity studies in improving the reliability and predictive power of computational models for biomaterial design and evaluation. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive examination of foundational principles, advanced methodological applications, optimization strategies for overcoming computational challenges, and rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing insights from recent advancements in machine learning, organoid modeling, and nanotechnology-based biosensing, this review aims to equip practitioners with the knowledge to develop more robust, clinically translatable computational tools for applications ranging from drug delivery and tissue engineering to implantable medical devices.

Foundations of Sensitivity Analysis in Biomaterial Modeling: From First Principles to Modern Applications

Defining Sensitivity Analysis in the Context of Computational Biomaterials

Sensitivity Analysis (SA) is defined as the study of how uncertainty in a model's output can be apportioned to different sources of uncertainty in the model input [1]. In the specific context of computational biomaterials, this translates to a collection of mathematical techniques used to quantify how the predicted behavior of a biomaterial—such as its mechanical properties, degradation rate, or biological interactions—changes in response to variations in its input parameters. These parameters can include material composition, scaffold porosity, chemical cross-linking density, and loading conditions, which are often poorly specified or subject to experimental measurement error [2] [1].

The analysis of a computational biomaterials model is incomplete without SA, as it is crucial for model reduction, inference about various aspects of the studied phenomenon, and experimental design [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding SA is indispensable for assessing prediction certainty, clarifying underlying biological mechanisms, and making informed decisions based on computational forecasts, such as optimizing a biomaterial for a specific therapeutic application [2].

Key Methods for Sensitivity Analysis: A Comparative Guide

Various SA methods exist, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and ideal application scenarios. They are broadly categorized into local and global methods. Local SA assesses the impact of small perturbations around a fixed set of parameter values, while global SA evaluates the effects of parameters varied simultaneously over wide, multi-dimensional ranges [3] [1].

Classification and Comparison of SA Methods

The table below provides a structured comparison of the most common sensitivity analysis methods used in computational biomaterials research.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Key Sensitivity Analysis Methods

| Method Type | Specific Method | When to Use | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local | One-at-a-Time (OAT) / Finite Difference [2] | Inexpensive, simple models; initial screening. | Simple to implement and interpret. | Does not explore interactions between parameters; local by nature. | Low |

| Local | Adjoint Sensitivity Analysis [2] | Models with many parameters but few outputs of interest. | Highly efficient for models with a large number of parameters. | Complex to implement; requires solving a secondary adjoint system. | Low (for many parameters) |

| Local | Forward Mode Automatic Differentiation [2] | Accurate gradient calculation for analytic functions. | High accuracy; avoids truncation errors of finite difference. | Can be difficult to implement for complex, non-analytic functions. | Medium |

| Local | Complex Perturbation Sensitivity Analysis [2] | Accurate gradient calculation for analytic models. | Simple implementation; high accuracy. | Limited to analytic functions without discontinuities. | Medium |

| Global | Partial Rank Correlation Coefficient (PRCC) [3] | Models with monotonic input-output relationships. | Robust to monotonic transformations; provides a correlation measure. | Misleading for non-monotonic relationships. | High |

| Global | Variance-Based (e.g., Sobol' Indices) [3] [1] | Models with non-monotonic relationships; quantifies interactions. | Quantifies interaction effects; model-independent. | Very high computational cost. | Very High |

| Global | Morris Method (Screening) [1] | Initial screening of models with many parameters. | Computationally cheaper than variance-based methods. | Provides qualitative (screening) rather than quantitative results. | Medium |

| Global | Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) [3] | Comprehensive sampling of parameter space for global SA. | Efficient stratification; better coverage than random sampling. | Often used as a sampling technique for other global methods, not an analysis itself. | High |

Quantitative Data from Experimental Studies

The following table summarizes quantitative findings from SA applications in related fields, illustrating how these methods provide concrete data for model refinement and validation.

Table 2: Exemplary Quantitative Data from Sensitivity Analysis Studies

| Study Context | SA Method Applied | Key Quantitative Finding | Impact on Model/Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| CARRGO Model for Tumor-Immune Interaction [2] | Differential Sensitivity Analysis | Revealed specific parameter sensitivities that traditional "naive" methods missed. | Provided deeper insight into the underlying biological mechanisms driving the model. |

| Deterministic SIR Model [2] | Second-Order Sensitivity Analysis | Demonstrated that second-order sensitivities were crucial for refining model predictions. | Improved forecast accuracy by accounting for non-linear interaction effects. |

| Stiffened Corrugated Steel Plate Shear Walls [4] | Numerical Modeling & Validation | Asymmetric diagonal stiffeners improved elastic buckling load and energy dissipation; a fitted formula for predicting ultimate shear resistance of corroded walls was provided. | Validated computational models with experimental data, leading to direct engineering design guidance. |

| Aluminum-Timber Composite Connections [4] | Laboratory Push-Out Tests | Toothed plate reinforcement increased connection stiffness but reduced strength for grade 5.8 bolts due to faster bolt shank shearing. | Provided nuanced design insight, showing reinforcement is not universally beneficial and is dependent on bolt grade. |

| Cement Composites with Modified Starch [4] | Rheological & Compressive Testing | Retentate LU-1412-R increased compressive strength by 25%, while LU-1422-R decreased it. | Identified specific natural admixtures that can enhance performance, supporting sustainable material development. |

Experimental Protocols for SA in Biomaterials Research

Implementing SA requires a structured workflow. The following protocols detail the steps for conducting both global and local SA, drawing from established methodologies in the field [3] [1].

Detailed Protocol for Global Sensitivity Analysis

Objective: To apportion the uncertainty in a model output (e.g., biomaterial scaffold Young's Modulus) to all uncertain input parameters (e.g., polymer molecular weight, cross-link density, pore size) over their entire feasible range.

Define Model and Output of Interest:

- Clearly state the computational model

Y = f(X₁, X₂, ..., Xₖ), whereYis the output quantity of interest (e.g., stress at failure) andXᵢare thekinput parameters.

- Clearly state the computational model

Parameter Selection and Range Specification:

- Identify all uncertain parameters

Xᵢ. - Define a plausible range for each parameter (e.g., uniform distribution between a lower and upper bound). Ranges can be based on experimental data or literature.

- Identify all uncertain parameters

Generate Input Sample Matrix:

- Use a sampling technique such as Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) to create an

N × kinput matrix. LHS ensures that the entire parameter space is efficiently stratified and covered, which is superior to simple random sampling [3]. - A common sample size

Nis between 500 and 1000 for initial analysis [3].

- Use a sampling technique such as Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) to create an

Run Model Simulations:

- Execute the computational model

Ntimes, each run corresponding to one set of parameter values from the input matrix. - For stochastic models, multiple replications (e.g., 3-5 or more, determined by a graphical or confidence interval method [3]) are required for each parameter set to control for aleatory uncertainty.

- Execute the computational model

Calculate Global Sensitivity Indices:

- For monotonic relationships, compute Partial Rank Correlation Coefficients (PRCC) between each input parameter and the output. This measures the strength of a monotonic relationship while controlling for the effects of other parameters [3].

- For non-monotonic relationships or to quantify interactions, use variance-based methods like Sobol' indices. The first-order Sobol' index (Sᵢ) measures the main effect of a parameter, while the total-order index (Sₜᵢ) includes its interaction effects with all other parameters [3] [1].

Detailed Protocol for Local (Differential) Sensitivity Analysis

Objective: To compute the local rate of change (gradient) of a model output with respect to its input parameters at a specific point in parameter space, which is vital for parameter estimation and optimization [2].

Define Nominal Parameter Set:

- Choose a baseline parameter vector

β₀around which to perform the analysis. This is often a best-fit or literature-derived parameter set.

- Choose a baseline parameter vector

Select a Differential Method:

- Forward Mode: Integrate the original model equations jointly with the sensitivity differential equations. This is efficient for models with few parameters [2].

- Adjoint Method: Solve a single backward-in-time adjoint equation to compute the gradient of a function of the solution with respect to all parameters. This is highly efficient for models with many parameters and few outputs [2].

- Automatic Differentiation: Use tools like DifferentialEquations.jl [2] to automatically and accurately compute derivatives without the truncation errors associated with finite differences.

- Complex Perturbation: For analytic models, compute gradients by evaluating the model at

β₀ + iε, whereiis the imaginary unit. The derivative is approximatelyIm(f(β₀ + iε)) / ε[2].

Compute Sensitivity Coefficients:

- Execute the chosen numerical method to obtain the partial derivatives

∂Y/∂βᵢat the pointβ₀.

- Execute the chosen numerical method to obtain the partial derivatives

Normalize Sensitivities (Optional):

- Calculate normalized sensitivity coefficients

Sᵢ = (∂Y/∂βᵢ) * (βᵢ / Y)to allow for comparison between parameters of different units and scales.

- Calculate normalized sensitivity coefficients

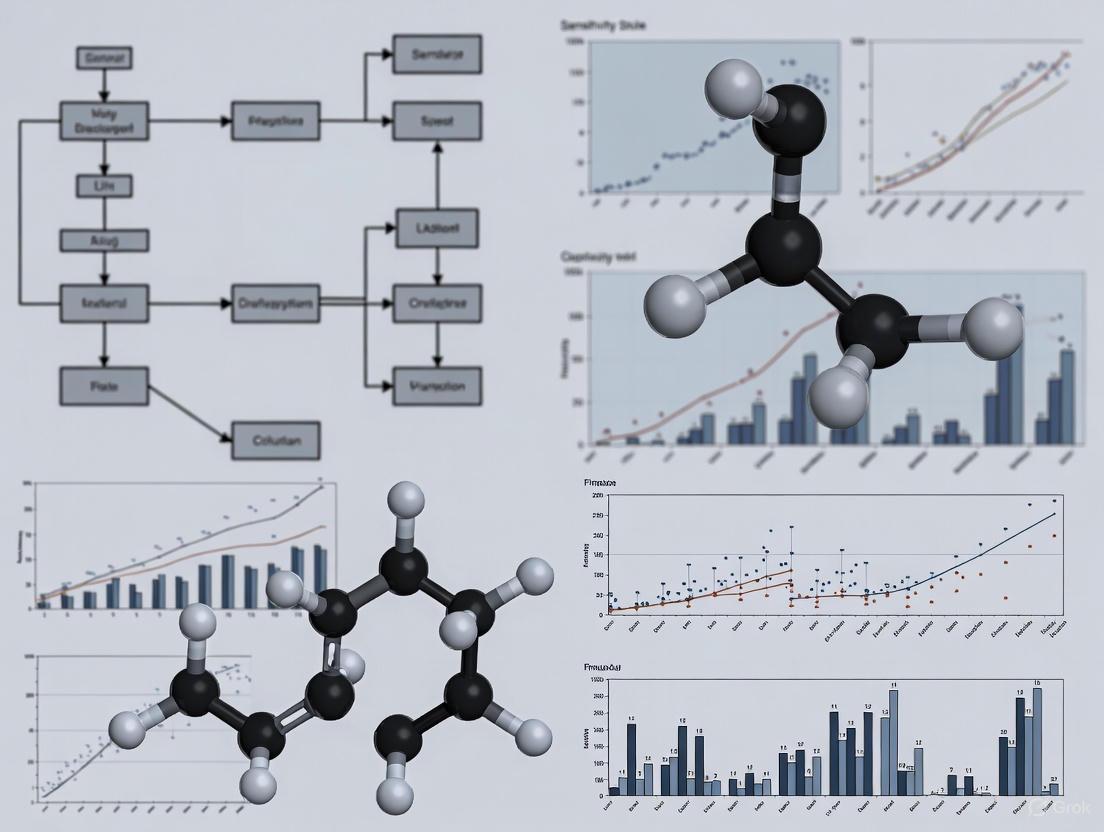

Visualizing Workflows and Multi-Scale Relationships

The logical relationships and workflows inherent in SA for computational biomaterials are best understood through diagrams. The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, adhere to the specified color and contrast rules.

Workflow for Global Sensitivity Analysis

The diagram below outlines the standard workflow for performing a global sensitivity analysis, from problem definition to interpretation of results.

Multi-Scale Modeling in Computational Biomaterials

Computational biomaterials often operate across multiple biological and material scales. SA helps identify which parameters at which scales most significantly influence the macro-scale output.

Successful implementation of SA requires both computational tools and an understanding of key material parameters. The table below lists essential "research reagents" for a virtual SA experiment in computational biomaterials.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Computational SA

| Item Name/Software | Function/Purpose | Application Context in Biomaterials |

|---|---|---|

| Dakota [1] | A comprehensive software framework for optimization and uncertainty quantification. | Performing global SA (e.g., Morris, Sobol' methods) on a finite element model of a polymer scaffold. |

| DifferentialEquations.jl [2] | A Julia suite for solving differential equations with built-in SA tools. | Conducting forward and adjoint sensitivity analysis on a pharmacokinetic model of drug release from a hydrogel. |

| SALib [1] | An open-source Python library for performing global SA. | Easily implementing Sobol' and Morris methods to analyze a model predicting cell growth on a surface. |

| Latin Hypercube Sample (LHS) [3] | A statistical sampling method to efficiently explore parameter space. | Generating a well-distributed set of input parameters (e.g., material composition, processing conditions) for a simulation. |

| Partial Rank Correlation Coefficient (PRCC) [3] | A sensitivity measure for monotonic relationships. | Identifying which material properties most strongly correlate with a desired biological response in a high-throughput screening study. |

| Sobol' Indices [3] [1] | A variance-based sensitivity measure for non-monotonic relationships and interactions. | Quantifying how interactions between pore size and surface chemistry jointly affect protein adsorption. |

| Adjoint Solver [2] | An efficient method for computing gradients in models with many parameters. | Calibrating a complex multi-parameter model of bone ingrowth into a metallic foam implant. |

| Computational Model Parameters (e.g., Scaffold Porosity, Polymer MW) | The virtual "reagents" whose uncertainties are being tested. | Serving as the direct inputs to the computational model whose influence on the output is being quantified. |

In the realm of computational biomaterial science, the transition from traditional empirical approaches to data-driven development strategies is paramount for accelerating discovery [5]. Computational models serve as powerful tools for formulating and testing hypotheses about complex biological systems and material interactions [1]. However, a significant obstacle confronting such models is that they typically incorporate a large number of free parameters whose values can substantially affect model behavior and interpretation [1]. Sensitivity Analysis (SA) is defined as the study of how uncertainty in a model's output can be apportioned to different sources of uncertainty in the model input [1]. This differs from uncertainty analysis, which characterizes the uncertainty in the model output but does not identify its sources [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, SA provides a mathematically robust framework for determining which parameters most significantly influence model outcomes, thereby guiding efficient resource allocation, model simplification, and experimental design.

The importance of SA in biomedical sciences stems from several inherent challenges. Biological processes are inherently stochastic, and collected data are often subject to significant measurement uncertainty [1]. Furthermore, while high-throughput methods excel at discovering interactions, they remain of limited use for measuring biological and biochemical parameters directly [1]. Parameters are frequently approximated collectively through data fitting rather than direct measurement, which can lead to large parameter uncertainties if the model is unidentifiable. SA methods are crucial for ensuring model identifiability, a property the model must satisfy for accurate and meaningful parameter inference from experimental data [1]. Effectively, SA bridges the gap between complex computational models and their practical application in biomaterial design, from tissue engineering scaffolds to drug delivery systems.

Comparative Analysis of Sensitivity Analysis Methodologies

A diverse array of SA techniques exists, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and ideal application domains. The choice of method depends on the model's computational cost, the nature of its parameters, and the specific analysis objectives, such as screening or quantitative ranking. The table below provides a structured comparison of key SA methods used in computational biomaterial research.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Sensitivity Analysis Methods

| Method Name | Classification | Key Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ideal Use Case in Biomaterials |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local/Derivative-Based | Local | Computes partial derivatives of output with respect to parameters at a baseline point [1]. | Computationally efficient; provides a clear linear estimate of local influence [1]. | Only valid within a small neighborhood of the baseline point; cannot capture global or interactive effects [1]. | Initial, rapid screening of parameters for simple, well-understood models. |

| Morris Method | Global, Screening | Computains elementary effects by averaging local derivatives across the parameter space [1]. | More efficient than variance-based methods; provides a good measure for factor screening and ranking [1]. | Does not quantify interaction effects precisely; results can be sensitive to the choice of trajectory number [1]. | Identifying the few most influential parameters in a high-dimensional model before detailed analysis [6] [1]. |

| Sobol' Method | Global, Variance-Based | Decomposes the variance of the output into fractions attributable to individual parameters and their interactions [7]. | Provides precise, quantitative measures of individual and interaction effects; model-independent [8] [1]. | Computationally very expensive, especially for models with high computational cost or many parameters [8]. | Final, rigorous analysis for a reduced set of parameters to obtain accurate sensitivity indices [7]. |

| ANOVA | Global, Variance-Based | Similar to Sobol', uses variance decomposition to quantify individual and interactive impacts [8]. | Computationally more efficient than Sobol's method; allows for analysis of individual and interactive impacts [8]. | Performance and accuracy compared to Sobol' can be problem-dependent. | Quantifying dynamic sensitivity and interactive impacts in computationally intensive models [8]. |

| Bayesian Optimization | Global, Probabilistic | Builds a probabilistic surrogate model of the objective function to guide the search for optimal parameters [9]. | Sample-efficient; provides uncertainty estimates for the fitted parameter values [9]. | Implementation is more complex than direct sampling methods. | Efficiently finding optimal parameters for computationally expensive cognitive or biomechanical models [9]. |

The shift from one-at-a-time experimental approaches to structured statistical methods like Design of Experiments (DoE) and modern SA represents a significant advancement in biomaterials research [10]. While DoE is powerful for planning experiments and analyzing quantitative data, it lacks suitability for high-dimensional data analysis, where the number of features exceeds the number of observations [10]. This is where machine learning (ML) and advanced SA methods demonstrate their strength, mapping complex structure-function relationships in biomaterials by strategically utilizing all available data from high-throughput experiments [11]. The "curse of dimensionality," where the required data grows exponentially with the number of features, makes specialized techniques like SA essential for accurate interpretation [11].

Experimental Protocols for Quantifying Parameter Influence

Protocol for Global Sensitivity Analysis Using the Sobol' Method

The Sobol' method is a cornerstone of global, variance-based SA, providing precise quantitative indices for parameter influence.

- Objective: To compute first-order (main effect) and total-order Sobol' indices for each model parameter, quantifying its individual contribution and its contribution including all interaction effects to the output variance [1] [7].

- Materials & Software: The computational model of interest, a computing environment (e.g., Python, MATLAB, R), and SA software (e.g., SALib [1]).

- Procedure:

- Parameter Range Definition: Define the plausible range and probability distribution for each model parameter to be analyzed.

- Sample Matrix Generation: Generate two independent sampling matrices (A and B) of size N × D, where N is the sample size (typically 1000+) and D is the number of parameters. Using a quasi-Monte Carlo sequence (e.g., Sobol' sequence) is recommended for better space-filling properties [1].

- Model Evaluation: Create a set of hybrid matrices from A and B and run the computational model for each row in these matrices. The total number of model evaluations required is N × (D + 2) [1].

- Index Calculation: Calculate the first-order (Si) and total-order (STi) Sobol' indices based on the variance of the model outputs using the formulas:

- First-order index (main effect): Si = V[E(Y|Xi)] / V(Y)

- Total-order index: STi = E[V(Y|X~i)] / V(Y) = 1 - V[E(Y|X~i)] / V(Y) where V(Y) is the total unconditional variance, E(Y|Xi) is the expected value of Y conditioned on a fixed Xi, and X~i represents all parameters except X_i [1].

- Output Interpretation: A high first-order index Si indicates the parameter itself has a strong individual influence on the output. A large difference between STi and S_i suggests the parameter is involved in significant interactions with other parameters.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the core steps of this protocol:

Figure 1: Sobol' Sensitivity Analysis Workflow

Protocol for Model Simplification via Dynamic Sensitivity Analysis

Dynamic sensitivity analysis reveals how the influences of parameters and their interactions change during a process, such as an optimization routine or a time-dependent simulation [8].

- Objective: To quantify the individual and interactive impacts of algorithm or model parameters on performance criteria (e.g., convergence speed, success rate) throughout an optimization process, enabling dynamic tuning and model simplification [8].

- Materials & Software: The optimization algorithm or dynamic model, computational resources, and software for Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) [8].

- Procedure:

- Parameter and Metric Selection: Select the parameters of the optimization algorithm or dynamic model to be investigated and define the performance metrics of concern (e.g., convergence speed at each iteration) [8].

- Experimental Design: Determine the feasible ranges for the selected parameters and create a set of random parameter combinations for multiple independent runs of the algorithm/model [8].

- Data Collection: Execute the algorithm/model for each parameter combination and record the chosen performance metrics at predefined intervals (e.g., every 100 function evaluations) [8].

- Variance Decomposition: At each interval, apply ANOVA to decompose the variance of the performance metric. This quantifies the contribution of each parameter's individual effect and its interactive effects with other parameters to the overall variance in performance [8].

- Simplification: Rank parameters by their contribution to variance over time. Parameters with consistently low individual and total contributions can be considered for fixation at a default value to simplify the model without significant performance loss [7].

- Output Interpretation: The analysis identifies which parameters are most critical at different stages of the process, informing adaptive tuning strategies and providing a principled basis for model reduction.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biomaterial Sensitivity Studies

Executing robust sensitivity analysis in computational biomaterials requires a combination of computational tools, model structures, and data sources. The following table details key resources essential for this field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Tools for Sensitivity Studies

| Reagent/Tool Name | Category | Specification/Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| SALib | Software Library | An open-source Python library for sensitivity analysis [1]. | Provides implemented functions for performing various SAs, including Morris and Sobol' methods, streamlining the analysis process. |

| Hill-type Muscle Model | Computational Model | A biomechanical model representing muscle contraction dynamics, often used in musculoskeletal modeling [7]. | Serves as a foundational component for models estimating joint torque; its parameters are common targets for SA and identification. |

| Dakota | Software Framework | A comprehensive software toolkit from Sandia National Laboratories [1]. | Performs uncertainty quantification and sensitivity analysis, including global SA using methods like Morris and Sobol'. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Biomaterial System | Versatile nanoparticles used in drug and gene delivery, e.g., in mRNA vaccines [11]. | A complex biomaterial system where SA helps identify critical design parameters (size, composition, charge) governing function. |

| 3D Scaffold Architectures | Biomaterial System | Porous structures for tissue engineering, produced via 3D printing or freeze-drying [11] [10]. | Their performance (mechanical properties, cell response) depends on multiple parameters (porosity, fiber diameter), making them ideal for SA. |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Optimization Tool | A population-based stochastic search algorithm inspired by natural selection [7]. | Used for parameter identification of complex models before SA, finding parameter sets that minimize the difference between model and experimental data. |

Application in Biomaterial and Biomechanical Research

The practical application of sensitivity analysis is vividly demonstrated in studies focusing on the interface between biology and engineering. For instance, research on a lower-limb musculoskeletal model for estimating knee joint torque employed Sobol's global sensitivity analysis to quantify the influence of model parameter variations on the output torque [7]. This approach allowed the researchers to propose a sensitivity-based model simplification method, effectively reducing model complexity without compromising predictive performance, which is crucial for real-time applications in rehabilitation robotics [7]. This demonstrates how SA moves beyond theoretical analysis to deliver tangible improvements in model utility and efficiency.

In the broader field of biomaterials, the challenge of mapping structure-function relationships is pervasive. Biomaterials possess multiple attributes—such as surface chemistry, topography, roughness, and stiffness—that interact in complex ways to drive biological responses like protein adsorption, cell adhesion, and tissue integration [11] [12]. This creates a high-dimensional problem where SA is not just beneficial but necessary. For example, uncontrolled protein adsorption (biofouling) on an implant surface can lead to thrombus formation, infection, and implant failure [12]. SA of computational models predicting fouling can identify the most influential material properties and experimental conditions (e.g., protein concentration, ionic strength), guiding the rational design of low-fouling materials and ensuring that in vitro tests more accurately recapitulate in vivo conditions [12]. As the field advances, the integration of machine learning with high-throughput experimentation is poised to further leverage SA for the accelerated discovery and optimization of next-generation biomaterials [5] [11].

The Evolution from Traditional Parametric Studies to Modern Data-Driven Approaches

The field of computational modeling in biology and drug development has undergone a profound transformation, shifting from traditional parametric studies to modern, data-driven approaches. Traditional parametric methods rely on fixed parameters and strong assumptions about underlying data distributions (e.g., normal distribution) to build mathematical models of biological systems [13]. In contrast, modern data-driven approaches leverage machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) to learn complex patterns and relationships directly from data without requiring pre-specified parametric forms [14] [15]. This evolution represents a fundamental change in philosophy—from assuming a model structure based on theoretical principles to allowing the data itself to reveal complex, often non-linear, relationships.

This methodological shift is particularly impactful in sensitivity analysis, a core component of computational biomodeling. Traditional local parametric sensitivity analysis examines how small changes in individual parameters affect model outputs while keeping all other parameters constant [16]. Modern global sensitivity methods like Sobol's analysis, combined with ML, can explore entire parameter spaces simultaneously, capturing complex interactions and non-linear effects that traditional methods might miss [7]. This evolution enables researchers to build more accurate, predictive models of complex biological systems, from metabolic pathways to drug responses, ultimately accelerating biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Historical Foundation: Traditional Parametric Methods

Traditional parametric approaches have long served as the foundation for computational modeling in biological research. These methods are characterized by their reliance on fixed parameters and specific assumptions about data distribution.

Core Principles and Applications

Parametric methods operate on the fundamental assumption that data follows a known probability distribution, typically the normal distribution [13]. This assumption allows researchers to draw inferences using a fixed set of parameters that describe the population. In computational biomedicine, these principles have been applied to:

- Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) Modeling: Using compartmental models with fixed parameters to predict drug concentration and effect over time [17]

- Survival Analysis: Applying parametric distributions (Weibull, exponential, log-logistic) to model time-to-event data, such as patient survival or disease recurrence [15]

- Metabolic Pathway Modeling: Constructing mathematical models of biochemical networks with kinetic parameters derived from literature [16]

Traditional Sensitivity Analysis Techniques

Local parametric sensitivity analysis has been a cornerstone technique for understanding model behavior. As demonstrated in a study of hepatic fructose metabolism, this approach involves "systematically varying the value of each individual input parameter while keeping the other parameters constant" and measuring the impact on model outputs [16]. The sensitivity coefficient is typically calculated using first-order derivatives of model outputs with respect to parameters:

[S{X/i} = \frac{ki}{cx} \cdot \frac{\partial cx}{\partial ki} \cdot 100\% \approx \frac{ki \cdot \Delta cx}{cx \cdot \Delta k_i} \cdot 100\%]

Where (S{X/i}) is the sensitivity coefficient, (cx) represents the concentration vector, and (k_i) is the system parameter vector [16].

Table 1: Characteristics of Traditional Parametric Methods in Biomedicine

| Characteristic | Description | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed Parameters | Uses a fixed number of parameters determined prior to analysis | Compartmental PK/PD models [17] |

| Distribution Assumptions | Assumes data follows known distributions (e.g., normal) | Parametric survival models (Weibull, exponential) [15] |

| Local Sensitivity | Analyzes effect of one parameter at a time while others are fixed | Metabolic pathway modeling [16] |

| Computational Efficiency | Generally computationally fast due to simpler models | Early-stage drug development [17] |

| Interpretability | High interpretability with clear parameter relationships | Dose-response modeling [17] |

Modern Paradigm: Data-Driven Approaches

Modern data-driven approaches represent a significant departure from traditional parametric methods, leveraging advanced computational techniques and large datasets to build models with minimal prior assumptions about underlying structures.

Key Methodological Advancements

The shift to data-driven methodologies has been enabled by several key advancements:

Machine Learning and AI Integration: ML algorithms can identify complex patterns in high-dimensional biological data without predefined parametric forms [15]. Artificial intelligence, particularly deep learning, has demonstrated "significant advancements across various domains, including drug characterization, target discovery and validation, small molecule drug design, and the acceleration of clinical trials" [18].

Global Sensitivity Analysis: Methods like Sobol's sensitivity analysis provide a "global" approach that evaluates parameter effects across their entire range while accounting for interactions between parameters [7]. This offers a more comprehensive understanding of complex model behavior compared to traditional local methods.

Integration of Multi-Scale Data: Modern approaches can integrate diverse data types, from genomic and proteomic data to clinical outcomes, creating more comprehensive models of biological systems [15].

Applications in Drug Development and Biomedical Research

Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) represents a paradigm shift in pharmaceuticals, leveraging "quantitative prediction and data-driven insights that accelerate hypothesis testing, assess potential drug candidates more efficiently, reduce costly late-stage failures, and accelerate market access for patients" [17]. Key applications include:

- AI-Enhanced Drug Discovery: Generative models can design novel drug candidates, with some platforms reporting "the discovery of a lead candidate in just 21 days" compared to traditional timelines [19].

- Predictive Biomarker Identification: ML algorithms analyze multi-omics data to identify biomarkers for patient stratification and treatment response prediction [15].

- Clinical Trial Optimization: Data-driven approaches predict clinical outcomes and optimize trial designs, improving success rates and reducing costs [17] [18].

Table 2: Comparison of Sensitivity Analysis Approaches

| Aspect | Traditional Local Sensitivity | Modern Global Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter Variation | One parameter at a time, small perturbations [16] | All parameters simultaneously, across full ranges [7] |

| Interaction Effects | Cannot capture parameter interactions | Quantifies interaction effects between parameters [7] |

| Computational Demand | Lower computational requirements | Higher computational requirements |

| Implementation Example | Local parametric sensitivity of fructose metabolism model [16] | Sobol's method for musculoskeletal model parameters [7] |

| Typical Output | Sensitivity coefficients for individual parameters [16] | Total sensitivity indices including interaction effects [7] |

Comparative Analysis: Performance and Applications

Performance Metrics in Biomedical Applications

Direct comparisons between traditional and modern approaches reveal context-dependent advantages. In survival prediction for breast cancer patients, modern machine learning methods demonstrated superior performance in certain scenarios: "The random forest model achieved the best balance between model fit and complexity, as indicated by its lowest Akaike Information Criterion and Bayesian Information Criterion values" [15]. However, the optimal approach depends on specific research questions and data characteristics.

In musculoskeletal modeling, a hybrid approach that combined traditional Hill-type muscle models with modern sensitivity analysis techniques proved effective. The researchers used Sobol's global sensitivity analysis to identify which parameters most significantly influenced model outputs, enabling strategic model simplification without substantial accuracy loss [7].

Application-Specific Considerations

The choice between traditional parametric and modern data-driven approaches depends on multiple factors:

- Data Availability: Traditional methods often perform better with limited data, while modern ML approaches typically require large datasets [13].

- Interpretability Needs: Parametric models generally offer higher interpretability, which is crucial for regulatory submissions and mechanistic understanding [17].

- Computational Resources: Modern data-driven approaches typically demand greater computational power and specialized expertise [20].

- Project Phase: Early discovery may benefit from data-driven exploration, while later stages may require the interpretability of parametric models [17].

Table 3: Performance Comparison in Biomedical Applications

| Application Domain | Traditional Parametric Approach | Modern Data-Driven Approach | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer Prognosis | Log-Gaussian survival models [15] | Neural networks, random forests [15] | Neural networks showed highest accuracy; random forests best balance of fit and complexity [15] |

| Musculoskeletal Modeling | Hill-type muscle models with fixed parameters [7] | Sensitivity-guided simplification with genetic algorithm optimization [7] | Sensitivity-based simplification maintained accuracy while improving computational efficiency [7] |

| Drug Development | Population PK/PD models [17] | AI-driven molecular design and trial optimization [19] | AI platforms report reducing discovery cycle from years to months [19] |

| Metabolic Pathway Analysis | Local sensitivity of kinetic parameters [16] | Systems biology with multi-omics integration | Local methods identified key regulators (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, pyruvate) in fructose metabolism [16] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Traditional Local Parametric Sensitivity Analysis

Objective: To identify the most influential parameters in a computational model of hepatic fructose metabolism [16].

Materials and Methods:

- Model System: Mathematical model of hepatic fructose metabolism comprising 11 biochemical reactions with 56 kinetic parameters from literature [16]

- Parameter Variation: Each kinetic parameter individually increased and decreased by 3% and 5% while keeping other parameters constant

- Simulation Conditions: 2-hour simulation following meal ingestion with varying fructose concentrations

- Output Measurement: Resulting values of model variables (metabolite concentrations) and reaction rates after the simulation period

- Sensitivity Calculation: Compute relative sensitivity coefficients using the formula: [S{X/i} \approx \frac{ki \cdot \Delta cx}{cx \cdot \Delta ki} \cdot 100\%] where (ki) is the parameter value, (c_x) is the output variable concentration, and (\Delta) denotes the change in these values [16]

Key Findings: Identified glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate and pyruvate as key regulatory factors in hepatic triglyceride accumulation following fructose consumption [16].

Protocol 2: Modern Global Sensitivity Analysis with Model Simplification

Objective: To simplify a lower-limb musculoskeletal model through parameter identification and sensitivity analysis [7].

Materials and Methods:

- Experimental Setup: Lower-limb physical and biological signal collection experiment without ground reaction force using EMG sensors and motion capture

- Model Structure: Established knee joint torque estimation model driven by four electromyography (EMG) sensors incorporating multiple advanced Hill-type muscle model components

- Parameter Identification: Employed genetic algorithm (GA) to identify model parameters using experimental data from several test subjects

- Sensitivity Analysis: Applied Sobol's global sensitivity analysis theory to quantify the influence of parameter variations on model outputs

- Model Simplification: Proposed sensitivity-based model simplification method retaining only parameters with significant influence on outputs

- Validation: Evaluated simplified model performance using normalized root mean square error (NRMSE) compared to experimental data [7]

Key Findings: The proposed musculoskeletal model provided comparable NRMSE through parameter identification, and the sensitivity-based simplification method effectively reduced model complexity while maintaining accuracy [7].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Computational Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| CellDesigner Software | Modeling and simulation of biochemical networks | Constructing mathematical model of hepatic fructose metabolism [16] |

| Surface EMG Sensors | Measurement of muscle activation signals | Collecting biological signals for musculoskeletal model parameter identification [7] |

| Motion Capture System | Tracking of movement kinematics | Recording physical signals during motion for biomechanical modeling [7] |

| Genetic Algorithm | Optimization method for parameter identification | Identifying parameters of musculoskeletal models [7] |

| Sobol's Method | Global sensitivity analysis technique | Analyzing influence of parameter variations on musculoskeletal model outputs [7] |

| AlphaFold | AI-powered protein structure prediction | Predicting protein structures for target identification in drug discovery [20] |

| TensorFlow/PyTorch | Deep learning frameworks | Building neural network models for survival prediction and drug response [15] [20] |

Visualizing Methodological Evolution and Workflows

Evolution of Computational Approaches

Modern Sensitivity Analysis Workflow

The evolution from traditional parametric studies to modern data-driven approaches represents significant methodological progress in computational biomedicine. Rather than viewing these approaches as mutually exclusive, the most effective research strategies often integrate both paradigms—leveraging the interpretability and theoretical foundation of parametric methods with the predictive power and flexibility of data-driven approaches [7] [15].

Future directions point toward increasingly sophisticated hybrid models, such as physics-informed neural networks that incorporate mechanistic knowledge into data-driven architectures, and expanded applications of AI in drug development that further "shorten development timelines, and reduce costs" [18] [20]. As these methodologies continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly enhance our ability to model complex biological systems, accelerate therapeutic development, and ultimately improve human health outcomes.

In biomaterials science and regenerative medicine, a fundamental challenge persists: understanding and predicting how molecular-level interactions influence cellular behavior, and how cellular activity collectively directs tissue-level formation and function. This cross-scale interaction is pivotal for developing advanced biomaterials for drug delivery, tissue engineering, and regenerative medicine [21]. Traditional experimental approaches often struggle to quantitatively monitor these multi-scale processes due to technical limitations in measuring forces, cellular parameters, and biochemical factor distributions simultaneously across different scales [21]. Computational multi-scale modeling has emerged as a powerful methodology to bridge this gap, complementing experimental studies by providing detailed insights into cell-tissue interactions and enabling prediction of tissue growth and biomaterial performance [21].

The inherent complexity of biological systems necessitates modeling frameworks that can seamlessly integrate phenomena occurring at different spatial and temporal scales. At the molecular level, interactions between proteins, growth factors, and material surfaces determine initial cellular adhesion. These molecular events trigger intracellular signaling pathways that dictate cellular decisions about proliferation, differentiation, and migration [22]. The collective behavior of multiple cells then generates tissue-level properties such as mechanical strength, vascularization, and overall function [21]. Multi-scale modeling provides a computational framework to connect these disparate scales, enabling researchers to predict how molecular design choices ultimately impact tissue-level outcomes, thereby accelerating the development of advanced biomaterials and reducing reliance on traditional trial-and-error approaches [23].

Computational Methodologies for Multi-Scale Integration

Fundamental Modeling Approaches

Multi-scale modeling in biological systems employs two primary strategic approaches: bottom-up and top-down methodologies. Bottom-up models aim to derive higher-scale behavior from the detailed dynamics and interactions of fundamental components [22]. For instance, in tissue engineering, a bottom-up approach might model molecular interactions between cells and extracellular matrix components to predict eventual tissue formation [21]. Conversely, top-down models begin with observed higher-level phenomena and attempt to deduce the underlying mechanisms at more fundamental scales [22]. This approach is particularly valuable when seeking to reverse-engineer biological systems from experimental observations of tissue-level behavior.

Several computational techniques have been successfully applied to multi-scale biological problems:

- Finite Element Analysis (FEA): Commonly used for continuum-level modeling of tissue mechanics and nutrient transport [21]

- Agent-Based Modeling: Captures cellular decision-making and interactions within populations [21]

- Molecular Dynamics (MD): Simulates molecular-level interactions between proteins, drugs, and material surfaces [24]

- Representative Volume Elements (RVE): Enables scale transition by defining microstructural domains that statistically represent larger material systems [24]

Hybrid and Advanced Computational Frameworks

Recent advancements have introduced more sophisticated hybrid frameworks that combine multiple modeling approaches. Hybrid multiscale simulation leverages both continuum and discrete modeling frameworks to enhance model fidelity [25]. For problems involving complex reactions and interactions, approximated physics methods simplify these processes to expedite computations without significantly sacrificing accuracy [25]. Most notably, machine-learning-assisted multiscale simulation has emerged as a powerful approach that integrates predictive analytics to refine simulation outputs [25].

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) algorithms are increasingly being deployed to analyze large datasets, identify patterns, and predict material properties that fulfill strict specifications for biomedical applications [26]. These approaches can address both forward problems (predicting properties from structure) and inverse problems (identifying structures that deliver desired properties) [23]. ML models range from supervised learning with labeled data to unsupervised learning that discovers hidden patterns, and reinforcement learning that optimizes outcomes through computational trial-and-error [23]. The integration of AI with traditional physical models represents one of the most promising directions for advancing multi-scale modeling capabilities [25].

Comparative Analysis of Multi-Scale Modeling Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Modeling Techniques for Multi-Scale Biological Systems

| Modeling Technique | Spatial Scale | Temporal Scale | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Nanoscale (1-10 nm) | Picoseconds to nanoseconds | Molecular interactions, protein folding, drug-biomaterial binding [24] | High resolution, atomic-level detail | Computationally expensive, limited timescales |

| Agent-Based Modeling | Cellular to tissue scale (µm to mm) | Minutes to days | Cell population dynamics, tissue development, cellular decision processes [21] [22] | Captures emergent behavior, individual cell variability | Parameter sensitivity, computational cost for large populations |

| Finite Element Analysis (FEA) | Cellular to organ scale (µm to cm) | Milliseconds to hours | Tissue mechanics, nutrient transport, stress-strain distributions [21] | Handles complex geometries, well-established methods | Limited molecular detail, continuum assumptions |

| Hybrid Multiscale Models | Multiple scales simultaneously | Multiple timescales | Tissue-biomaterial integration, engineered tissue growth [21] [25] | Links processes across scales, more comprehensive | Complex implementation, high computational demand |

| Machine-Learning-Assisted Simulation | All scales | All timescales | Property prediction, model acceleration, inverse design [25] [23] | Fast predictions, pattern recognition, handles complexity | Requires large datasets, limited mechanistic insight |

Table 2: Comparison of Bottom-Up vs. Top-Down Modeling Strategies

| Aspect | Bottom-Up Approach | Top-Down Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Strategy | Derives higher-scale behavior from lower-scale components [22] | Deduces underlying mechanisms from higher-scale observations [22] |

| Model Development | Stepwise construction from molecular to tissue level | Reverse-engineering from tissue-level phenomena to molecular mechanisms |

| Data Requirements | Detailed parameters for fundamental components | Comprehensive higher-scale observational data |

| Validation Challenges | Difficult to validate across all scales simultaneously | Multiple potential underlying mechanisms may explain same high-level behavior |

| Knowledge Gaps | Reveals gaps in understanding of fundamental processes [22] | Highlights missing connections between scales |

| Computational Cost | High for detailed fundamental models | Lower initial cost, increases with detail added |

| Typical Applications | Molecular mechanism studies, detailed process modeling [22] | Hypothesis generation from observational data, initial model development [22] |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Protocol 1: Validating Cellular Mechanoresponse Models

Objective: To experimentally validate computational models predicting cellular responses to mechanical stimuli in three-dimensional biomaterial environments [21].

Materials and Methods:

- Prepare 3D collagen hydrogel scaffolds with controlled stiffness (varied collagen concentration from 1-5 mg/mL) [21]

- Seed with mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) or myoblasts at density of 1×10^6 cells/mL [21]

- Culture constructs between two fixed ends to apply static tension [21]

- Utilize Culture Force Monitor (CFM) to continuously measure collective cellular contraction forces [21]

- Fix constructs at timepoints (days 1, 3, 7, 14) for immunohistochemical analysis of cell orientation, differentiation markers, and matrix organization [21]

- Perform live cell imaging to track individual cell migration and morphology changes [21]

- Measure oxygen and nutrient gradients using embedded sensors [21]

Computational Correlation:

- Develop finite element model simulating mechanical environment within hydrogel [21]

- Implement agent-based model to simulate cellular decision-making in response to mechanical cues [21]

- Compare predicted force generation, cell orientation, and tissue organization with experimental measurements [21]

- Iteratively refine model parameters based on experimental discrepancies [21]

Protocol 2: Sensitivity Enhancement in Biosensor Designs

Objective: To validate multi-scale models predicting sensitivity enhancement in surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensors through core-shell nanoparticle inclusion [27].

Materials and Methods:

- Fabricate SPR biosensors using BK7 prism coated with 40nm Ag layer [27]

- Synthesize Fe3O4@Au core-shell nanoparticles with controlled core radius (2.5-10nm) and shell thickness (1-5nm) [27]

- Functionalize sensor surface with core-shell nanoparticles at varying volume fractions (0.1-0.5) [27]

- Introduce biomaterial samples: blood plasma, haemoglobin cytoplasm, lecithin at controlled concentrations [27]

- Measure ATR spectra using Kretschmann configuration with 632.8nm laser source [27]

- Quantify resonance angle shifts before and after biomaterial introduction [27]

- Calculate sensitivity enhancement compared to conventional SPR biosensors [27]

Computational Correlation:

- Develop electromagnetic model using effective medium theory approximation [27]

- Calculate effective permittivity of core-shell nanoparticle and composite [27]

- Simulate reflectivity as function of incident angle for various core sizes and volume fractions [27]

- Validate model predictions against experimental resonance angle shifts and sensitivity measurements [27]

Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Scale Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Multi-Scale Biomaterial Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Multi-Scale Studies | Specific Applications | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3D Hydrogel Scaffolds | Provides 3D environment for cell culture that better replicates in vivo conditions [21] | Tissue engineering, mechanobiology studies [21] | Tunable stiffness, porosity, biocompatibility |

| Fe3O4@Au Core-Shell Nanoparticles | Enhances detection sensitivity in biosensing applications [27] | SPR biosensors, biomolecule detection [27] | Combines magnetic and plasmonic properties, biocompatible |

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Model cell type for studying differentiation in response to mechanical cues [21] | Tissue engineering, regenerative medicine [21] | Multi-lineage potential, mechanoresponsive |

| Culture Force Monitor (CFM) | Measures collective forces exerted by cells in 3D constructs [21] | Quantifying cell-tissue mechanical interactions [21] | Continuous, non-invasive force monitoring |

| Phase-Change Materials | Thermal energy storage for controlled environment systems [28] | Bioreactor temperature control, thermal cycling | High heat capacity, reversible phase changes |

| Aerogels | Highly porous scaffolds for tissue engineering and drug delivery [28] | Biomedical engineering, regenerative medicine [28] | Ultra-lightweight, high porosity, tunable surface chemistry |

Sensitivity Analysis in Multi-Scale Frameworks

Sensitivity analysis represents a critical component in validating multi-scale models, particularly in the context of computational biomaterial research. It involves systematically varying input parameters at different scales to determine their relative impact on model predictions and overall system behavior [27]. For instance, in SPR biosensor design, sensitivity analysis reveals how core-shell nanoparticle size (molecular scale) influences detection capability (device scale), with studies showing that a core radius of 2.5nm can increase sensitivity by 10-47% depending on the target biomolecule [27].

At the cellular scale, sensitivity studies examine how variations in extracellular matrix stiffness (tissue scale) influence intracellular signaling and gene expression (molecular scale), ultimately affecting cell differentiation fate decisions [21]. Computational models enable researchers to systematically explore this parameter space, identifying critical thresholds and nonlinear responses that would be difficult to detect through experimental approaches alone [21]. For example, models have revealed that stem cell differentiation exhibits heightened sensitivity to specific stiffness ranges, with small changes triggering completely different lineage commitments [21].

The integration of machine learning with traditional sensitivity analysis has created powerful new frameworks for exploring high-dimensional parameter spaces efficiently. ML algorithms can identify the most influential parameters across scales, enabling researchers to focus experimental validation efforts on the factors that most significantly impact system behavior [23]. This approach is particularly valuable for inverse design problems, where desired tissue-level outcomes are known, but the optimal molecular and cellular parameters to achieve those outcomes must be determined [23].

The integration of multi-scale modeling approaches continues to evolve, with several emerging trends shaping its future development. The incorporation of artificial intelligence and machine learning represents perhaps the most significant advancement, enabling more efficient exploration of complex parameter spaces and enhanced predictive capabilities [25] [23]. ML-assisted multiscale simulation already demonstrates promise in balancing model complexity with computational feasibility, particularly for inverse design problems in biomaterial development [25].

As multi-scale modeling matures, we anticipate increased emphasis on standardization and validation frameworks. The development of robust benchmarking datasets and standardized protocols for model validation across scales will be essential for advancing the field [21] [22]. Additionally, the growing availability of high-resolution experimental data across molecular, cellular, and tissue scales will enable more sophisticated model parameterization and validation [21].

The ultimate goal of multi-scale modeling in biomaterials research is the creation of comprehensive digital twins—virtual replicas of biological systems that can accurately predict behavior across scales in response to therapeutic interventions or material designs. While significant challenges remain in managing computational expense and effectively coupling different scale-specific modeling techniques [24] [25], the continued advancement of multi-scale approaches promises to accelerate the development of novel biomaterials and regenerative therapies through enhanced computational prediction and reduced experimental trial-and-error.

Role in De-risking Biomaterial Development and Accelerating Clinical Translation

The development of novel biomaterials has traditionally been a time- and resource-intensive process, plagued by a high-dimensional design space and complex performance requirements in biological environments [29]. Conventional approaches relying on sequential rational design and iterative trial-and-error experimentation face significant challenges in predicting clinical performance, creating substantial financial and safety risks throughout the development pipeline [30] [31]. The integration of computational models, particularly those powered by artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), is fundamentally transforming this paradigm by enabling predictive design and systematic de-risking long before clinical implementation [30] [32].

These computational approaches function within an iterative feedback loop where in silico predictions guide targeted experimental synthesis and characterization, whose results subsequently refine the computational models [32]. This integrated framework allows researchers to explore parameter spaces that cannot be easily modified in laboratory settings, exercise models under varied physiological conditions, and optimize material properties with unprecedented efficiency [32]. By providing data-driven insights into the complex relationships between material composition, structure, and biological responses, computational modeling reduces reliance on costly serendipitous discovery and positions biomaterial development on a more systematic, predictable foundation [31].

Computational Approaches for Biomaterial De-risking

Predictive Modeling of Material Properties and Biocompatibility

A primary application of computational models in biomaterial science involves predicting critical material properties and biological responses based on chemical structure and composition. AI systems can analyze complex biological and material datasets to forecast attributes like mechanical strength, degradation rates, and biocompatibility, thereby enhancing preclinical research ethics and accelerating the identification of promising candidates [30].

Table 1: Computational Predictions for Key Biomaterial Properties

| Biomaterial Class | Predictable Properties | Common Computational Approaches | Reported Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metallic Alloys | Mechanical strength, corrosion resistance, fatigue lifetime | Machine Learning, Active Learning | Successful prediction of optimal Ti-Mo-Si compositions for bone prosthesis [31] |

| Polymeric Biomaterials | Hydrogel formation, immunomodulatory behavior, protein adhesion | Random Forest, Support Vector Machines | ML models developed with initial libraries of 43 polymers for RNA transfection design [29] |

| Ceramic Biomaterials | Bioactivity, resorption rates, mechanical integrity | Deep Learning, Supervised Learning | Prediction of fracture behavior and optimization of mechanical properties [31] [29] |

| Composite Biomaterials | Interfacial bonding, drug release profiles, degradation | Ensemble Methods, Transfer Learning | ML-directed design of polymer-protein hybrids for maintained activity in harsh environments [29] |

The predictive capability of these models directly addresses several critical risk factors in biomaterial development. By accurately forecasting biocompatibility—the fundamental requirement for any clinical material—computational approaches can prioritize candidates with the highest potential for clinical success while flagging those likely to elicit adverse biological reactions [31]. Furthermore, these models can predict material performance under specific physiological conditions, reducing the likelihood of post-implantation failure due to unanticipated material-biological interactions [33].

AI-Driven High-Throughput Screening and Optimization

Machine learning excels in digesting large and complex datasets to extract patterns, identify key drivers of functionality, and make predictions on the behavior of future material iterations [29]. When integrated with high-throughput combinatorial synthesis techniques, ML creates a powerful "Design-Build-Test-Learn" paradigm that dramatically accelerates the data-driven design of novel biomaterials [29].

Table 2: Comparison of Traditional vs. AI-Driven Development Approaches

| Development Phase | Traditional Approach | AI-Driven Approach | Risk Reduction Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Screening | Sequential testing of individual candidates | Parallel in silico screening of thousands of virtual candidates | Identifies toxicity and compatibility issues earlier; reduces animal testing |

| Composition Optimization | Empirical, trial-and-error adjustments | Bayesian optimization and active learning for targeted experimentation | Minimizes failed experiments; accelerates identification of optimal parameters |

| Performance Validation | Limited to synthesized variants | Predictive modeling across continuous parameter spaces | Reveals failure modes before manufacturing; ensures robust design specifications |

| Clinical Translation | High attrition rate due to unanticipated biological responses | Improved prediction of in vivo performance from in vitro data | Increases likelihood of clinical success through better candidate selection |

Advanced ML strategies like active learning are particularly valuable for risk reduction in biomaterial development. In active learning, ensemble or statistical methods return uncertainty values alongside predictions to map parameter spaces with high uncertainty [29]. This information enables researchers to strategically initialize new experiments with small, focused datasets that target regions of feature space that would be most fruitful for exploration, creating a balanced "explore vs exploit" approach [29]. Research has demonstrated the superior efficiency and efficacy of ML-directed active learning data collection compared to large library screens, directly addressing resource constraints while maximizing knowledge gain [29].

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Protocol for Predictive Biocompatibility Modeling

Objective: To validate computational predictions of biomaterial biocompatibility through standardized in vitro testing. Materials and Reagents:

- Candidate biomaterials (prioritized by computational screening)

- Appropriate cell lines (e.g., osteoblasts for bone materials, fibroblasts for soft tissue)

- Cell culture media and supplements

- Metabolic activity assay kits (e.g., MTT, Alamar Blue)

- Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for inflammatory markers

- Flow cytometry reagents for apoptosis/necrosis detection

Methodology:

- Computational Prediction Phase: Input material descriptors (chemical composition, surface properties, etc.) into trained ML models to predict cytotoxicity and immunogenicity.

- Material Preparation: Fabricate/synthesize top-ranked candidates from computational screening using standardized protocols.

- Extract Preparation: Incubate materials in cell culture medium following ISO 10993-12 guidelines to generate extraction media.

- Cell Viability Assessment: Seed cells in 96-well plates and expose to extraction media. Assess metabolic activity after 24, 48, and 72 hours.

- Inflammatory Response Profiling: Measure secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) via ELISA after 24-hour exposure.

- Cell Death Analysis: Quantify apoptosis and necrosis rates using flow cytometry with Annexin V/PI staining.

- Model Validation: Compare experimental results with computational predictions to refine model accuracy.

This protocol directly addresses translation risks by establishing a rigorous correlation between computational predictions and experimental outcomes, creating a validated framework for future candidate screening [31].

Protocol for Mechanical Property Prediction and Validation

Objective: To verify computationally-predicted mechanical properties of candidate biomaterials through standardized mechanical testing. Materials and Equipment:

- Fabricated biomaterial specimens (prioritized by computational screening)

- Universal mechanical testing system

- Environmental chamber for physiological condition simulation

- Digital calipers for dimensional verification

- Scanning electron microscope for failure analysis

Methodology:

- Computational Prediction: Utilize ML models trained on material descriptors to predict key mechanical properties (tensile strength, compressive modulus, fatigue resistance).

- Specimen Fabrication: Manufacture predicted high-performing materials using controlled processing parameters.

- Dimensional Verification: Precisely measure all specimens to ensure standardized testing geometry.

- Mechanical Testing:

- Tensile Testing: Conduct according to ASTM D638/ISO 527 for polymers or ASTM E8/E8M for metals at physiological temperature (37°C).

- Compressive Testing: Perform according to ASTM D695/ISO 604 for relevant applications (e.g., bone implants).

- Fatigue Testing: Apply cyclic loading at physiologically-relevant frequencies and loads to determine fatigue lifetime.

- Fracture Analysis: Examine failure surfaces using SEM to correlate predicted and actual failure modes.

- Model Refinement: Feed experimental results back into computational models to improve predictive accuracy.

This validation protocol is essential for de-risking structural biomaterials, particularly those intended for load-bearing applications like orthopedic and dental implants, where mechanical failure carries significant clinical consequences [34].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Computational-Experimental Biomaterial Validation

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Validation Pipeline | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Medical-Grade PEEK Filament | High-performance polymer for orthopedic and dental prototypes | Customized spinal cages, bone screws [34] |

| Titanium Alloy Powders | Metallic biomaterials for load-bearing implant applications | Orthopedic implants, joint replacements [31] [33] |

| Calcium Phosphate Ceramics | Bioactive materials for bone tissue engineering | Bone repair scaffolds, osteoconductive coatings [33] |

| Peptide-Functionalized Building Blocks | Self-assembling components for bioactive hydrogels | 3D cell culture matrices, drug delivery systems [29] |

| Molecular Dynamics Simulation Software | In silico prediction of material-biological interactions | Simulating protein adsorption, degradation behavior [29] |

| High-Temperature 3D Printing Systems | Additive manufacturing of high-performance biomaterials | Fabricating patient-specific PEEK implants [34] |

Visualization of Computational-Experimental Workflows

Computational-Experimental Workflow for De-risking

Comparative Analysis of Biomaterial Performance

Metallic vs. Polymeric Biomaterials for Orthopedic Applications

Table 4: Performance Comparison of Orthopedic Biomaterial Classes

| Property | Titanium Alloys | PEEK Polymers | Comparative Clinical Risk Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elastic Modulus | 110-125 GPa | 3-4 GPa | PEEK's bone-like modulus reduces stress shielding; lowers revision risk |

| Strength-to-Weight Ratio | High | Moderate | Titanium superior for load-bearing; PEEK advantageous for lightweight applications |

| Biocompatibility | Excellent (with surface oxidation) | Excellent | Both demonstrate strong biocompatibility with proper surface characteristics |

| Imaging Compatibility | Creates artifacts in CT/MRI | Radiolucent, no artifacts | PEEK superior for post-operative monitoring and assessment |

| Manufacturing Complexity | High (subtractive methods) | Moderate (additive manufacturing) | PEEK more amenable to patient-specific customization via 3D printing |

| Long-term Degradation | Corrosion potential in physiological environment | Hydrolytic degradation | Titanium more stable long-term; PEEK degradation manageable in many applications |

The clinical translation risk profile differs significantly between these material classes. Titanium's high stiffness, while beneficial for load-bearing, creates a substantial risk of stress shielding and subsequent bone resorption—a common cause of implant failure [34]. PEEK's bone-like modulus directly addresses this risk factor, though with potential trade-offs in ultimate strength requirements for certain applications [34]. The radiolucency of PEEK eliminates imaging artifacts that can complicate postoperative assessment of titanium implants, providing clearer diagnostic information throughout the implant lifecycle [34].

Benchmarking Predictive Model Performance Across Biomaterial Classes

Table 5: Performance Metrics of Computational Models for Biomaterial Prediction

| Model Type | Biomaterial Class | Prediction Accuracy | Key Validation Metrics | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | Polymeric Biomaterials | 85-92% (gelation prediction) | ROC-AUC: 0.89-0.94 | Requires extensive feature engineering |

| Neural Networks | Metallic Alloys | 88-95% (mechanical properties) | R²: 0.91-0.96 | Large training datasets required |

| Support Vector Machines | Ceramic Biomaterials | 82-90% (bioactivity prediction) | F1-score: 0.85-0.91 | Performance decreases with sparse data |

| Transfer Learning | Composite Biomaterials | 78-88% (degradation rates) | MAE: 12-15% | Dependent on source domain relevance |

| Active Learning | Diverse Material Classes | 85-93% (multiple properties) | Uncertainty quantification: ±8% | Initial sampling strategy critical |

The benchmarking data reveals that while computational models achieve impressive predictive accuracy across diverse biomaterial classes, each approach carries distinct limitations that must be considered in risk assessment [31] [29]. Model performance is highly dependent on data quality and quantity, with techniques like transfer learning and active learning showing particular promise for addressing the sparse data challenges common in novel biomaterial development [29]. The integration of uncertainty quantification in active learning approaches provides particularly valuable risk mitigation by explicitly identifying prediction confidence and guiding targeted experimentation to reduce knowledge gaps [29].

Computational models are fundamentally transforming the risk landscape in biomaterial development by replacing uncertainty with data-driven prediction. Through integrated workflows that combine in silico screening with targeted experimental validation, researchers can now identify potential failure modes earlier in the development process, optimize material properties with unprecedented precision, and significantly accelerate the translation of promising biomaterials from bench to bedside. As these computational approaches continue to evolve—fueled by advances in AI, machine learning, and high-throughput experimentation—they promise to further de-risk biomaterial development while enabling the creation of increasingly sophisticated, patient-specific solutions that meet the complex challenges of modern clinical medicine.

Advanced Methodologies and Cutting-Edge Applications in Biomaterial Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity Analysis (SA) constitutes a critical methodology for investigating how the uncertainty in the output of a computational model can be apportioned to different sources of uncertainty in the model inputs [35]. In the context of computational biomaterial models and drug development, SA transitions from a mere diagnostic tool to a fundamental component for model interpretation, validation, and biomarker discovery. The emergence of complex machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models in biomedical research has intensified the need for robust sensitivity frameworks that can demystify the "black box" nature of these algorithms while ensuring their predictions are biologically plausible and clinically actionable [36] [37].

Global Sensitivity Analysis (GSA) methods have gained particular prominence as they evaluate the effect of input parameters across their entire range of variation, not just local perturbations, making them exceptionally suited for nonlinear biological systems where interactions between parameters are significant [35]. These methods align with a key objective of explainable AI (XAI): clarifying and interpreting the behavior of machine learning algorithms by identifying the features that influence their decisions—a crucial approach for mitigating the computational burden associated with processing high-dimensional biomedical data [35]. As pharmaceutical companies increasingly leverage AI to analyze massive datasets for target identification, molecular behavior prediction, and clinical trial optimization, understanding model sensitivity becomes paramount for reducing late-stage failures and accelerating drug development timelines [38] [18].

Comparative Framework of Sensitivity Analysis Techniques

Methodological Categories and Mathematical Foundations

Sensitivity analysis techniques can be broadly categorized into distinct methodological families, each with unique mathematical foundations and applicability to different model architectures in computational biomaterial research.

Table 1: Categories of Sensitivity Analysis Methods

| Category | Key Methods | Mathematical Basis | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variance-Based | Sobol Indices | Decomposition of output variance into contributions from individual parameters and their interactions [35] | Nonlinear models with interacting factors; biomarker identification [35] |

| Derivative-Based | Morris Method | Elementary effects calculated through local derivatives [35] | Screening influential parameters in high-dimensional models [35] |

| Density-Based | δ-Moment Independent | Measures effect on entire output distribution without moment assumptions [35] | Models where variance is insufficient to describe output uncertainty [35] |

| Feature Additive | SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Game-theoretic approach allocating feature contributions based on cooperative game theory [39] | Interpreting individual predictions for any ML model; clinical decision support [39] |

| Gradient-Based | Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping) | Uses gradients flowing into final convolutional layer to produce coarse localization map [40] | Visual explanations for CNN-based medical image analysis [40] [37] |

The Sobol method, one of the most established variance-based approaches, relies on the decomposition of the variance of the model output under the assumption that inputs are independent. The total variance of the output Y (V(Y)) is decomposed into variances from individual parameters and their combinations, resulting in first-order (Si) and total-order (STi) sensitivity indices that quantify individual and interactive effects, respectively [35]. In contrast, moment-independent methods like the δ-index consider the entire distribution of output variables without relying on variance, making them suitable for models where variance provides an incomplete picture of output uncertainty [35].

Performance Comparison Across Biomedical Applications