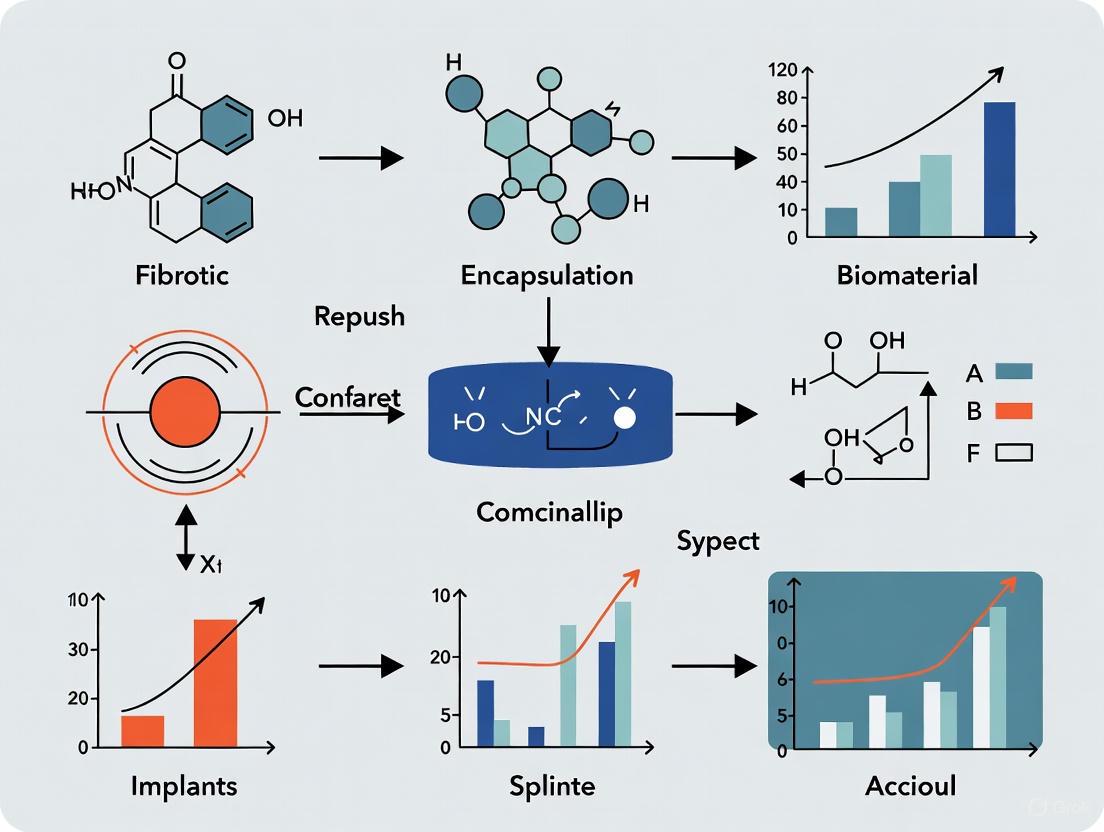

Preventing Fibrotic Encapsulation of Breast Implants: Molecular Mechanisms, Biomaterial Innovations, and Therapeutic Strategies

This review provides a comprehensive analysis of the pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging strategies to prevent fibrotic encapsulation of breast implants, a major complication leading to capsular contracture.

Preventing Fibrotic Encapsulation of Breast Implants: Molecular Mechanisms, Biomaterial Innovations, and Therapeutic Strategies

Abstract

This review provides a comprehensive analysis of the pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging strategies to prevent fibrotic encapsulation of breast implants, a major complication leading to capsular contracture. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we synthesize foundational science on the foreign body response, exploring the critical roles of mechanical signaling, TGF-β activation, and immune cell interplay. The article details methodological advances in biomaterial engineering, including surface topography, soft coatings, and immunomodulatory approaches. We further evaluate troubleshooting for clinical challenges and validate strategies through comparative analysis of preclinical and clinical data, offering a roadmap for developing next-generation implants and targeted anti-fibrotic therapies.

Decoding the Foreign Body Response: Cellular and Molecular Drivers of Implant Fibrosis

{css}

/* Technical Support Center: The Fibrotic Cascade */

Fibrotic Cascade Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Low Cell Yield from Capsule Tissue Digestion

Problem: After enzymatic digestion of breast implant capsule tissue, the resulting cell yield is low, hindering subsequent analysis.

- Check Tissue Processing: Ensure the tissue is thoroughly minced into fragments smaller than 1 mm before digestion to maximize surface area for enzyme action [1].

- Verify Enzyme Activity: Confirm that the collagenase solution was freshly prepared or properly aliquoted and stored to prevent loss of activity. The standard concentration used is 0.75 mg/mL [1].

- Optimize Digestion Time: The standard digestion period is 1 hour at 37°C. Over-digestion can damage cells, while under-digestion reduces yield [1].

- Validate Cell Sorting Markers: When sorting fibroblast subpopulations, ensure the use of validated antibody panels. A common combination is CD26 (a fibrogenic marker) with vimentin (a pan-fibroblast marker) for identification [1].

High Background in Immunofluorescence (IF) Staining

Problem: High background fluorescence obscures specific signal when staining for markers like α-SMA or CD26 in capsular tissue sections.

- Confirm Antibody Compatibility: Ensure the secondary antibody is specific to the host species of the primary antibody and is not cross-reacting with other tissue elements [2].

- Optimize Blocking: Use an appropriate blocking solution (e.g., 1% Power Block) for at least 2 hours at room temperature to reduce non-specific binding [1].

- Titrate Antibodies: The concentration of both primary and secondary antibodies may need optimization. A common starting dilution for primary antibodies is 1:200 [1].

- Include Controls: Always run negative controls (omitting the primary antibody) to distinguish specific staining from background [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key cellular players in the fibrotic cascade around breast implants? A1: The process involves an orchestrated response from immune cells and structural cells. Initially, neutrophils and macrophages respond to the implant. Subsequently, fibroblasts are activated and can differentiate into myofibroblasts, which are the primary collagen-producing cells responsible for capsule formation and contraction. A specific subpopulation of pro-fibrotic fibroblasts marked by CD26 has been identified as being particularly responsible for collagen production [1] [3] [4].

Q2: What is the central signaling pathway driving myofibroblast differentiation? A2: The Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF-β) pathway is the prototypical driver. It operates through both canonical (Smad-dependent) and non-canonical (e.g., MAPK/JNK/p38) signaling pathways to activate the genetic program for myofibroblast differentiation, leading to increased expression of α-SMA, collagens, and fibronectin [5] [3].

Q3: How does implant surface topography influence the fibrotic response? A3: Surface texture is a critical determinant of the host immune response. Roughness influences protein adsorption, immune cell activation, and cytokine profiles. Implants with an average roughness of ~4 µm have been shown to elicit less inflammation and thinner fibrous capsules compared to rougher surfaces, which can trigger a stronger pro-fibrotic TH1/TH17 immune response [6].

Q4: What are the essential controls for a reliable fibroblast activation experiment? A4:

- Positive Control: Treat fibroblasts with a known activator like TGF-β (e.g., 2-10 ng/mL) to ensure the system can detect differentiation.

- Negative Control: Use untreated fibroblasts to establish a baseline activation state.

- Technical Control: Include a housekeeping gene (e.g., GAPDH, β-actin) in gene expression analyses (qPCR) to normalize data [5].

The table below consolidates key quantitative findings from recent research on capsular fibrosis.

Table 1: Key Experimental Findings in Capsular Fibrosis Research

| Parameter | Finding | Experimental Context | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD26+ Fibroblast Collagen Production | Produced more collagen than CD26- fibroblasts | Cell sorting and culture from human breast capsules | [1] |

| Critical Surface Roughness (Ra) | ~4 µm associated with least inflammation and fibrosis | Comparison of silicone implants in patients | [6] |

| Enzymatic Digestion Concentration | 0.75 mg/mL collagenase | Digestion of human breast capsule tissue for FACS | [1] |

| Primary Antibody Dilution (IF) | 1:200 | Immunofluorescence on human breast capsule sections | [1] |

| Key Gene Expression in CD26+ Fibroblasts | Increased IL8, TGF-β1, COL1A1, TIMP4 | qPCR on sorted fibroblast populations from human capsules | [1] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Flow Cytometry Analysis of Capsular Fibroblasts

This protocol details the process for isolating and characterizing fibroblast subpopulations from human breast implant capsule tissue [1].

1. Tissue Digestion:

- Thoroughly mince the freshly obtained capsule specimen into fragments <1 mm.

- Enzymatically digest the tissue using 0.75 mg/mL collagenase from Clostridium histolyticum in a digest buffer (e.g., with 5% FBS and DNase I).

- Incubate for 1 hour at 37°C with gentle agitation (120 rpm).

2. Cell Sorting (FACS):

- Resuspend the resulting single-cell suspension.

- Incubate cells with fluorescently conjugated antibodies against target surface markers (e.g., anti-CD26 to identify pro-fibrotic fibroblasts, anti-vimentin as a pan-fibroblast marker).

- Use a fluorescence-activated cell sorter to isolate the CD26-positive and CD26-negative fibroblast populations for downstream functional assays.

3. Downstream Analysis:

- Culture the sorted fibroblasts to assess collagen production.

- Extract RNA to analyze gene expression of fibrotic markers (e.g., IL8, TGF-β1, COL1A1, TIMP4) via qPCR.

Protocol: Immunofluorescence Staining for Myofibroblasts

This protocol is used to visualize and confirm the presence of activated myofibroblasts in capsular tissue sections [1].

1. Tissue Preparation:

- Fix capsule tissue specimens immediately in 4% paraformaldehyde for 16 hours at 4°C.

- Cryoprotect by immersing in 30% sucrose for 5 days before embedding in OCT compound.

- Section the OCT blocks into 6-μm thick slices using a cryostat.

2. Staining Procedure:

- Permeabilize tissue sections with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 30 minutes.

- Block sections with 1% blocking solution for 2 hours at room temperature.

- Incubate with primary antibodies (e.g., anti-α-SMA for myofibroblasts, anti-CD26) diluted in blocking solution (1:200) for 18 hours at 4°C.

- Wash sections and incubate with appropriate fluorescent secondary antibodies (e.g., diluted 1:4000) for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Mount slides with a DAPI-containing medium to counterstain nuclei.

3. Imaging:

- Image the stained sections using a confocal microscope.

- Analyze for co-localization of markers (e.g., α-SMA and CD26) to identify activated pro-fibrotic fibroblast populations.

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

The Core Fibrotic Signaling Pathway

Fibroblast Isolation & Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Fibrosis Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Collagenase | Enzymatic digestion of fibrous capsule tissue to isolate cells. | From Clostridium histolyticum; used at 0.75 mg/mL [1]. |

| Anti-CD26 Antibody | Identification and sorting of a pro-fibrotic fibroblast subpopulation. | Rabbit anti-CD26; used for Immunohistochemistry and FACS [1]. |

| Anti-α-SMA Antibody | Marker for activated myofibroblasts; key indicator of fibrosis. | Used in immunofluorescence to visualize contractile cells [1] [3]. |

| Anti-Vimentin Antibody | Pan-fibroblast marker; identifies the general fibroblast population. | Goat anti-vimentin; often used in co-staining with CD26 [1]. |

| TGF-β1 Cytokine | Positive control to induce myofibroblast differentiation in vitro. | Typical working concentration of 2-10 ng/mL [5]. |

| Silicone Implants (Various Ra) | To study the effect of surface topography on the foreign body response. | Implants with defined roughness (e.g., Ra ~4µm vs. Ra ~60µm) [6]. |

| Sulfatroxazole | Sulfatroxazole | High-Purity Antibacterial Agent | Sulfatroxazole is a potent synthetic antibacterial compound for research use only (RUO). Explore its mechanism and applications. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| N-Acetylhistidine | N-Acetyl-L-histidine|High-Purity Research Compound | N-Acetyl-L-histidine for research applications. Study its role as a molecular water pump in models. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

FAQs: Immune Mechanisms in Capsular Fibrosis

1. What are the key macrophage phenotypes involved in the foreign body reaction to breast implants, and how do they influence capsular contracture?

The foreign body reaction (FBR) to breast implants is characterized by a dynamic interplay of macrophage phenotypes, primarily the pro-inflammatory M1 and the pro-repair M2 macrophages [7] [8].

- M1 Macrophages (CD68+NOS2+): Dominant in the acute inflammatory phase post-implantation. They are classically activated by bacterial components (e.g., via TLR4) or T-cell-derived IFN-γ. M1 macrophages boost inflammation by releasing cytokines like TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8, and contribute to tissue damage via reactive oxygen species (ROS) and degradative enzymes [7] [9]. Sustained M1 activation is profibrotic.

- M2 Macrophages (CD68+CD206+): Predominant later in the FBR, activated by IL-4 and IL-13. They dampen inflammation and orchestrate tissue repair and fibrosis by producing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and the master fibrotic regulator, Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF-β) [7] [8]. A controlled M2 response is necessary for normal healing, but persistent activity drives excessive fibrosis.

An imbalance, particularly a prolonged M1-dominated response often linked to biofilm presence or chronic inflammation, leads to sustained cytokine release and TGF-β-driven fibroblast activation, resulting in capsular contracture [7] [8].

2. Which T-cell subsets are associated with promoting or preventing capsular contracture?

Both innate and adaptive immunity are involved in fibrogenesis, with specific T-helper (Th) cell subsets playing distinct roles [10] [8].

- Pro-Fibrotic Subsets: Th1 (secreting IFN-γ) and Th17 (secreting IL-17) responses are pro-inflammatory and associated with the M1 macrophage phenotype. Contracted capsules show greater infiltrates of Th1/Th17 T cells and express higher levels of TGF-β, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-17, directly contributing to capsular fibrosis [8]. Th2 cells (secreting IL-4 and IL-13) are linked to the M2 macrophage phenotype and are also involved in profibrotic wound repair [8].

- Anti-Fibrotic Subsets: A dominant Th2 response is generally considered profibrotic in other organ systems [11]. However, within the context of breast implant capsules, the Th2-driven M2 macrophage activation is stated to lead to less capsular contracture, highlighting the complexity and context-dependency of these pathways [8]. The role of regulatory T cells (Tregs) in breast capsules is less defined, though in other fibrotic diseases they often exhibit anti-fibrotic effects [10].

3. What are the primary experimental models for studying immune responses to implant surfaces?

- In Vivo Models: Rodent models (e.g., Wistar rats) are widely used to study capsule formation around implanted devices [12]. Researchers can control variables like implant surface topography (smooth, macrotextured, nanotextured), placement, and administration of therapeutic compounds.

- In Vitro Models: These involve culturing macrophages (e.g., cell lines like RAW 264.7 or primary human macrophages) with implant surface materials or conditioned media. This allows for controlled investigation of specific signaling pathways and cytokine production in response to different surface chemistries and topographies [9].

- Human Tissue Analysis: Capsular tissues from revision surgeries are analyzed using histology, immunohistochemistry, and molecular biology techniques to characterize immune cell infiltrates and cytokine profiles, providing direct human pathological data [7] [8].

4. Our histology shows a thick, collagen-dense capsule. What immune profiling should we perform to understand the driving mechanism?

Focus your analysis on key immune cells and fibrotic markers.

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC)/Immunofluorescence (IF): Quantify cell populations using specific antibodies.

- Western Blot/Quantitative PCR (qPCR): Analyze protein and gene expression levels of key cytokines and fibrotic mediators.

Table 1: Key Targets for Immune Profiling of Fibrotic Capsules

| Target | Cell Type / Process | Significance in Capsular Contracture |

|---|---|---|

| CD68 / NOS2 | M1 Macrophages | Indicates pro-inflammatory, profibrotic activation [7] |

| CD206 | M2 Macrophages | Indicates pro-repair, fibrotic activation [7] |

| CD3 / CD4 | T-Lymphocytes | General T-cell infiltration [8] |

| IFN-γ | Th1 Cells | Pro-inflammatory cytokine, linked to M1 polarization [8] |

| IL-17 | Th17 Cells | Pro-inflammatory, profibrotic cytokine [8] |

| TGF-β1 | Fibrosis Master Regulator | Potent driver of fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition and collagen production [7] [12] |

| α-SMA | Myofibroblasts | Activated fibroblast responsible for contraction and ECM deposition [12] |

| Collagen I | Extracellular Matrix (ECM) | Primary component of the fibrous capsule [12] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent macrophage polarization in in vitro assays.

- Potential Cause 1: Inadequate or variable stimulation. LPS and IFN-γ are required for robust M1 polarization, while IL-4 and IL-13 are essential for M2 polarization [9]. Check cytokine activity and concentrations.

- Solution: Use fresh, high-purity cytokines at established concentrations (e.g., 20-100 ng/mL LPS + 20-50 ng/mL IFN-γ for M1; 20-50 ng/mL IL-4 for M2). Include positive controls (e.g., known M1/M2 marker analysis via qPCR or flow cytometry).

- Potential Cause 2: Cell culture conditions affecting responsiveness. Serum batches can vary and contain polarizing factors.

- Solution: Use a consistent, well-characterized serum batch. Consider using serum-free media formulations designed for macrophage culture during the polarization stage.

Problem: High variability in capsule thickness in an animal model.

- Potential Cause 1: Surgical technique inconsistency leading to varying degrees of tissue trauma, bleeding, or contamination.

- Solution: Standardize the surgical procedure, including pocket creation, implant handling, and closure. Implement strict aseptic techniques to prevent subclinical infection, a known trigger for contracture [13] [8].

- Potential Cause 2: Uncontrolled implant movement or positioning.

- Solution: Ensure a properly sized pocket and consistent implant placement. Studies show implant movement varies with surface type, which can influence the FBR [12].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluating the Effect of Implant Surface Topography on Capsule Formation (In Vivo)

This protocol is based on a study comparing smooth, macrotextured, and nanotextured implants [12].

- Animal and Grouping: Utilize 48 Wistar rats. Randomly divide them into 3 experimental groups (n=16 per group): Group A (Smooth implant), Group B (Macrotextured implant), Group C (Nanotextured implant). Each group is further divided into 4-week and 12-week endpoints.

- Implantation Surgery: Perform sterile surgery to insert one implant into a subcutaneous pocket on the rat's back. Administer standard post-operative analgesics.

- Tissue Harvest: At each endpoint, euthanize the animals and carefully explant the implant with the surrounding capsular tissue intact.

- Analysis:

- Histology: Fix tissue in formalin, embed in paraffin, and section. Perform:

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): Stain sections for α-SMA (myofibroblasts) and TGF-β1 to assess fibrotic activity [12].

- Western Blot: Homogenize capsule tissue to quantify protein expression levels of TGF-β1 and other fibrosis markers [12].

Table 2: Key Reagents for Implant-Capsule Interaction Studies

| Research Reagent | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Silicone Implants (Smooth, Macro, Nano) | The foreign body to trigger the FBR; variable topography is the independent variable [12]. |

| Anti-CD68 / Anti-NOS2 Antibodies | IHC/IF markers for identifying pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages [7]. |

| Anti-CD206 Antibodies | IHC/IF markers for identifying pro-repair M2 macrophages [7]. |

| Anti-α-SMA Antibody | Marker for activated myofibroblasts, the key contractile cell in fibrosis [12]. |

| Anti-TGF-β1 Antibody | Detects the master regulator of fibrosis via IHC or Western Blot [12]. |

| LPS & IFN-γ | In vitro stimulants for polarizing macrophages to the M1 phenotype [9]. |

| IL-4 & IL-13 | In vitro stimulants for polarizing macrophages to the M2 phenotype [9]. |

Protocol 2: In Vitro Macrophage Polarization in Response to Implant Surface Microparticles

- Macrophage Culture: Use a human macrophage cell line (e.g., THP-1 differentiated with PMA) or primary human monocyte-derived macrophages.

- Particle Generation & Treatment: Generate silicone microparticles from implant materials. Co-culture macrophages with varying concentrations of particles in culture media.

- Polarization Stimulation: After particle exposure, stimulate the cells with standard M1 (LPS + IFN-γ) or M2 (IL-4) polarizing cytokines for 24-48 hours.

- Analysis:

- qPCR: Isolate RNA and analyze expression of M1 markers (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) and M2 markers (Arg1, Mrc1, Fizz1) [9].

- ELISA: Collect cell culture supernatant and measure secretion of key cytokines like TNF-α (M1) or TGF-β (M2/fibrosis).

- Flow Cytometry: Harvest cells and stain for surface markers CD80/86 (M1) and CD206 (M2) for quantification of populations.

Signaling Pathway Visualizations

Macrophage Polarization Signaling

T-cell Macrophage Crosstalk

FAQs: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: In my 2D culture, TGF-β treatment does not consistently induce myofibroblast differentiation. What could be the issue?

The inconsistency often stems from inadequate activation of latent TGF-β or the absence of necessary mechanical tension.

- Problem: Latent TGF-β requires activation before it can bind to its receptors. In 2D cultures without sufficient mechanical force or the correct integrins, this activation may not occur.

- Solution: Ensure proper TGF-β activation. You can use commercially available active TGF-β1. Alternatively, to study physiological activation, pre-coat plates with an RGD-containing peptide (e.g., from fibronectin) or use a cell line that expresses relevant integrins like αVβ6 or αVβ8 [14] [15]. Confirming the presence of mechanical tension in your culture system is also critical.

Q2: My 3D fibrotic microtissue model is not demonstrating sufficient collagen alignment and contraction. How can I improve it?

The key is to provide topographical guidance and ensure the presence of mechanically activated cells.

- Problem: Randomly polymerized collagen gels lack the directional cues found in fibrotic tissues, leading to disorganized matrix deposition.

- Solution: Incorporate microfabricated structures (like micropillar arrays) into your 3D model to guide tissue alignment and measure contractile forces [16]. Co-culture fibroblasts with pro-fibrotic macrophages (M2-like), as their interaction significantly enhances collagen alignment and tissue contraction through integrin-mediated mechanotransduction [16].

Q3: How can I specifically inhibit integrin-mediated TGF-β activation without affecting other pathways?

Target the specific integrins or the mechanical link they provide.

- Solution: Utilize small molecule inhibitors or blocking antibodies against specific integrins. For example, Cilengitide targets αV-containing integrins. To specifically disrupt the mechanical link between integrins and the cytoskeleton, use low concentrations of ROCK inhibitors (e.g., Y-27632) or myosin II inhibitors (e.g., blebbistatin) [17] [16]. This prevents the generation of contractile force required for integrin-mediated TGF-β activation.

Q4: What are the best markers to confirm a pro-fibrotic phenotype in my in vitro model?

A combination of markers for activated fibroblasts, ECM, and immune cells is most reliable.

- Solution: The table below summarizes key markers for a pro-fibrotic phenotype.

Table 1: Key Markers for Profibrotic Phenotype Analysis

| Cell Type | Marker | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Myofibroblast | α-SMA (Alpha-Smooth Muscle Actin) | Gold standard for fibroblast-to-myofibroblast differentiation [18] [16] [3]. |

| Collagen I, Fibronectin (especially EDA+ isoform) | Indicates elevated ECM production [18] [17]. | |

| Pro-fibrotic Macrophage | CD206, Arginase-1 | Associated with M2/pro-fibrotic polarization [16]. |

| Integrin αM (CD11b) / β2 (CD18) | Indicates mechanical activation [16]. | |

| General Pathway | Phospho-Smad2/3 | Indicates active canonical TGF-β signaling [18] [19]. |

| CTGF (Connective Tissue Growth Factor) | Key downstream mediator of TGF-β's fibrotic effects [18]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol 1: Assessing Integrin-Mediated TGF-β Activation in a Co-culture System

This protocol is designed to study how mechanically activated macrophages contribute to TGF-β activation and fibroblast differentiation in a 3D microtissue, relevant to the fibrotic capsule microenvironment.

- Objective: To investigate the role of macrophage-fibroblast crosstalk in driving TGF-β activation and fibrosis.

Materials:

- Normal Human Lung Fibroblasts (NHLFs) or human dermal fibroblasts.

- Human peripheral blood monocytes.

- Recombinant IL-4 and IL-13 (to polarize monocytes to M2 macrophages).

- Type I collagen solution.

- Micropillar-based microtissue molds (e.g., spiral or diamond patterns).

- Anti-integrin β2 (CD18) blocking antibody or ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632).

- Antibodies for immunofluorescence: α-SMA, Collagen I, CD206.

Method:

- Microtissue Formation: Mix NHLFs with collagen I and seed into micropillar molds. Allow fibroblasts to remodel the matrix for 3-5 days, forming an aligned microtissue [16].

- Macrophage Polarization and Seeding: Differentiate monocytes into M2 macrophages using IL-4 and IL-13 (e.g., 20 ng/mL each for 48 hours). Seed these macrophages onto the pre-formed fibroblast microtissues.

- Experimental Inhibition: To test the role of mechanotransduction, treat co-cultures with an integrin β2 blocking antibody or ROCK inhibitor.

- Analysis: After 3-7 days of co-culture, fix microtissues and perform immunofluorescence staining for α-SMA, collagen I, and CD206. Analyze the degree of cell and collagen alignment, and quantify α-SMA intensity. Measure contractile force generation by tracking micropillar deflection [16].

Protocol 2: Quantifying Myofibroblast Differentiation in a Stiffness-Controlled 2D System

This protocol examines how substrate stiffness synergizes with soluble factors to drive fibrosis.

- Objective: To evaluate the combined effect of substrate mechanics and TGF-β on fibroblast activation.

Materials:

- Polyacrylamide hydrogels of tunable stiffness (e.g., 1 kPa mimicking healthy tissue, 50 kPa mimicking fibrotic tissue).

- Sulfo-SANPAH for crosslinking collagen I to the hydrogel surface.

- Human fibroblasts.

- Latent or active TGF-β1.

Method:

- Hydrogel Preparation: Fabricate polyacrylamide hydrogels with compliant (1 kPa) and stiff (50 kPa) substrates. Coat the surface with type I collagen using the crosslinker Sulfo-SANPAH.

- Cell Seeding and Treatment: Plate fibroblasts onto the hydrogels. Treat cells with either latent TGF-β or active TGF-β.

- Analysis: After 48-72 hours, fix and stain for α-SMA and paxillin (to visualize focal adhesions). The number of α-SMA-positive stress fibers and the size of focal adhesions will be significantly greater on stiff substrates, especially in the presence of TGF-β, demonstrating mechanical potentiation of the fibrotic response [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Investigating Mechanical Profibrotic Signaling

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant TGF-β1 (Active) | Directly activates TGF-β receptors. | Positive control for inducing Smad2/3 phosphorylation and myofibroblast differentiation [18] [15]. |

| Latent TGF-β Complex | Requires activation for function. | Studying physiological TGF-β activation mechanisms via integrins or proteases [18] [14]. |

| Cilengitide | Small molecule inhibitor of αV integrins. | Blocking integrins αVβ3, αVβ5, and αVβ6 to inhibit integrin-mediated TGF-β activation [20]. |

| Integrin β2 (CD18) Blocking Antibody | Inhibits leukocyte-specific integrins. | Disrupting macrophage mechanical activation and their pro-fibrotic crosstalk with fibroblasts [16]. |

| Y-27632 (ROCK Inhibitor) | Inhibits Rho-associated kinase (ROCK). | Reducing cellular contractility; blocks force-mediated TGF-β activation and myofibroblast contraction [17] [16] [3]. |

| Pirfenidone | FDA-approved anti-fibrotic drug. | Multi-target inhibitor; used to validate fibrotic models. Recently shown to inhibit macrophage mechanical activation via ROCK2 [16]. |

| Tunable Stiffness Hydrogels | Mimics compliant or stiff tissue environments. | Essential for studying the role of matrix mechanics in potentiating TGF-β signaling and fibroblast activation [17]. |

| Micropillar Arrays | Measures cellular contractile forces. | Quantifying the contractile output of myofibroblasts and the contribution of mechanical force to fibrosis [16]. |

| Cyclo(Ala-Phe) | Cyclo(Ala-Phe), CAS:14474-78-3, MF:C12H14N2O2, MW:218.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Methyladipic acid | 3-Methyladipic Acid|High-Purity Research Chemical | 3-Methyladipic acid, a key metabolite in Refsum disease research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Pathway Diagrams for Core Signaling Mechanisms

TGF-β Activation and Signaling

Macrophage-Fibroblast Profibrotic Crosstalk

Capsular fibrosis, specifically capsular contracture (CC), is the most common complication following breast implant surgery, often leading to pain, implant distortion, and the need for revision surgery [21] [3]. While the formation of a thin, soft fibrous capsule is a normal foreign body response, the progressive tightening and contraction that defines CC is a pathological process [3]. A growing body of evidence implicates subclinical biofilm infections as a primary etiological factor in this process [21] [22]. Biofilms are structured communities of microorganisms encased in a self-produced polymeric matrix that adhere to a surface, such as a breast implant [21]. These biofilm communities are highly resistant to antibiotics and host immune responses, leading to a state of chronic, low-grade inflammation that can drive excessive fibroblast activation and collagen deposition, resulting in clinical contracture [21] [3] [22]. This technical support guide is designed to assist researchers in investigating this critical biofilm-infection connection to develop effective preventative and therapeutic strategies.

FAQs: Biofilms and Implant-Related Fibrosis

What is the clinical evidence linking biofilms to capsular contracture? Multiple clinical studies have directly cultured bacteria from implants and capsules explanted due to contracture. The table below summarizes key clinical evidence:

Table: Clinical Evidence of Biofilms in Capsular Contracture

| Study Focus | Author | Key Finding | Level of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of Biofilms | Virden et al. [21] | Correlation between positive bacterial cultures on silicone shells and development of CC. | 3 (Case-control) |

| Presence of Biofilms | Pajkos et al. [21] | Identification of biofilms via sonication and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) on explanted devices. | 3 (Case-control) |

| Presence of Biofilms | Schreml et al. [21] | Bacterial colonization confirmed via culture in patients with CC. | 3 (Case-control) |

Which bacterial species are most commonly associated with biofilms on breast implants? The biofilm community on mammary implants is often polymicrobial, but certain commensal skin bacteria are frequently identified [21]. The most common organisms include:

- Staphylococcus epidermidis: A major part of the skin flora and the most frequently identified species on explanted breast implants [21].

- Staphylococcus aureus: Another common skin commensal with strong biofilm-forming capabilities [21].

- Propionibacterium acnes: A skin and gut commensal that may gain access to the implant during surgery, particularly with peri-areolar incisions [21].

How do biofilms on implants drive the process of fibrotic encapsulation? Biofilms induce a persistent foreign body reaction. The innate immune system recognizes biofilm components, triggering a chronic inflammatory cascade. This involves sustained activation of macrophages, which release pro-fibrotic cytokines like Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF-β) [3] [22]. TGF-β is a master regulator that drives the differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, which are characterized by the expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and are responsible for excessive collagen production and tissue contraction, leading to a thick, constrictive capsule [3].

Why are biofilm-related infections so resistant to antibiotic treatment? Biofilms confer resistance through multiple, overlapping mechanisms [21]:

- Physical Barrier: The extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix limits antibiotic penetration.

- Altered Microenvironments: Gradients in nutrients, oxygen, and pH within the biofilm create heterogeneous populations of bacteria, including dormant, persister cells that are highly tolerant to antibiotics.

- Upregulated Stress Responses: Bacteria in a biofilm state differentially express genes, including those for multidrug efflux pumps and antibiotic-degrading enzymes like β-lactamases.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Inconsistent Biofilm Formation In Vitro

- Problem: High variability in biofilm biomass between experimental replicates.

- Solution:

- Standardize Inoculum: Use a defined growth medium (e.g., Tryptic Soy Broth with 1% glucose [23]) and carefully control the initial bacterial concentration (e.g., half McFarland density diluted to ~5x10^5 CFU/mL) [23].

- Control Surface Properties: Ensure the material used for in vitro assays (e.g., silicone discs) has consistent surface topography and chemistry, as these are critical factors for bacterial adhesion [24] [3].

- Include Controls: Always include a known strong biofilm-forming strain (e.g., S. aureus ATCC 25923) and a non-biofilm forming negative control in every assay run [23].

Challenge 2: Differentiating Between Planktonic and Biofilm Antimicrobial Resistance

- Problem: An agent shows efficacy against free-floating (planktonic) bacteria but fails against a established biofilm.

- Solution: Employ specific assays designed for biofilms.

- Minimum Biofilm Eliminating Concentration (MBEC) Assay: This is the standard method. After forming a biofilm in a 96-well plate, treat it with serial dilutions of the antimicrobial agent. The MBEC is the lowest concentration that eliminates the visible biofilm [23]. The XTT colorimetric assay can be used to quantify metabolic activity of biofilm-resident bacteria post-treatment [23].

- Data Interpretation: Note that MBEC values are often orders of magnitude higher than the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) for planktonic cells. For example, one study on S. aureus found strains susceptible to ceftiofur in the planktonic state but resistant in the biofilm state [23].

Challenge 3: Modeling the Complex Host Immune Response to Biofilms In Vivo

- Problem: Simple rodent models may not fully recapitulate the human foreign body response and fibrotic cascade.

- Solution:

- Use Larger Animal Models: Porcine (pig) skin and immune responses are closer to humans, making them valuable for preclinical studies [21].

- Incorplicate Key Read-Outs: Beyond quantifying bacterial load, analyze the explanted tissue and capsule for:

- Histology: Collagen density (Trichrome stain), immune cell infiltration (H&E), and myofibroblast presence (α-SMA immunohistochemistry) [3] [22].

- Cytokine Profiling: Measure levels of pro-fibrotic cytokines (e.g., TGF-β, IL-17) and pro-inflammatory markers (e.g., IL-1, TNF-α) in peri-implant tissue [3] [22].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Quantitative Analysis of Biofilm Formation via Colorimetric Assay

This protocol, adapted from Stepanović et al. and used in mastitis research, is a cornerstone for in vitro biofilm quantification [23].

Workflow Diagram: Biofilm Quantification Assay

Materials:

- Tissue culture-treated 96-well plate (e.g., JET BIOFIL) [23]

- Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) with 1% glucose [23]

- Bouin's reagent or equipment for air-drying at 60°C [23]

- 0.1% Crystal Violet solution

- 95% Ethanol

- Microplate reader (e.g., Epoch, BioTek) [23]

Procedure:

- Inoculation: Dilute a fresh bacterial culture 2:200 in TSB + 1% glucose. Pipette 200 µL into designated wells. Include control wells with sterile broth only [23].

- Incubation: Incubate the plate aerobically for 24 hours at 37°C [23].

- Washing: Gently discard the supernatant from each well. Wash the wells three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove non-adherent planktonic cells. Let the plate air-dry.

- Fixing: Fix the adhered biofilms by adding Bouin's reagent for 1 hour or by air-drying the plate at 60°C for 1 hour [23].

- Staining: Add 0.1% crystal violet solution to each well for 5-15 minutes.

- Destaining: Rinse the plate thoroughly under running tap water until the control wells appear clear. Air-dry the plate.

- Solubilization: Add 200 µL of 95% ethanol to each well to solubilize the dye bound to the biofilm. Allow it to sit for 10-30 minutes with gentle shaking.

- Measurement: Transfer 125 µL of the solubilized dye from each well to a new plate (or measure directly if the plate is compatible). Measure the optical density (OD) at 570 nm using a microplate reader [23].

Data Analysis: Calculate the cut-off value (ODc) as the average OD of the negative control plus three times its standard deviation. Categorize biofilm formation as follows [23]:

- None: OD ≤ ODc

- Weak: ODc < OD ≤ 2xODc

- Moderate: 2xODc < OD ≤ 4xODc

- Strong: OD > 4xODc

Protocol: Molecular Detection of Biofilm-Associated Genes

Understanding the genetic basis of biofilm formation in clinical isolates is crucial.

Materials:

- PCR reagents (Taq polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, MgClâ‚‚)

- Primers for target genes (e.g., icaA, icaD, fnbA, fnbB, bap) [23]

- Thermocycler

- Gel electrophoresis equipment

Procedure:

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from your bacterial isolates using a standard boiling or commercial kit method.

- PCR Amplification: Set up PCR reactions with specific primers and cycling conditions as previously described for each target gene [23].

- Gel Electrophoresis: Run the PCR products on an agarose gel, visualize under UV light, and score for the presence or absence of the target amplicon.

Table: Common Biofilm-Associated Genes in Staphylococci

| Gene | Function / Encodes For | Reported Frequency in S. aureus Isolates |

|---|---|---|

| icaD | Intercellular adhesion locus (polysaccharide synthesis) | 75% [23] |

| fnbA | Fibronectin-binding protein A (initial attachment) | 43.8% [23] |

| fnbB | Fibronectin-binding protein B (initial attachment) | 31.2% [23] |

| bap | Biofilm-associated protein | 25% [23] |

| icaA | Intercellular adhesion locus | 9.4% [23] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Biofilm and Fibrosis Research

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Silicone Discs/Sheets | In vitro substrate for biofilm growth; mimics implant material. | Ensure consistent surface topography (smooth vs. textured) as it influences bacterial adhesion [24] [3]. |

| Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) + 1% Glucose | Standardized rich medium for promoting biofilm growth of Staphylococci. | The added glucose enhances production of extracellular polysaccharides [23]. |

| Crystal Violet | A basic dye used for the colorimetric quantification of total biofilm biomass. | Standard, cost-effective method; cannot distinguish between live and dead cells [23]. |

| XTT Assay Kit | Colorimetric assay to measure the metabolic activity of cells within a biofilm. | Used for determining MBEC and assessing viability after antimicrobial treatment [23]. |

| Anti-α-SMA Antibody | Primary antibody for immunohistochemistry to identify activated myofibroblasts in fibrous capsules. | A key marker for the profibrotic cellular phenotype [3]. |

| Anti-TGF-β Antibody | For detecting levels of this master regulatory cytokine in tissue sections (IHC) or supernatants (ELISA). | Central to the pro-fibrotic signaling pathway [3] [22]. |

| PCR Primers for icaADBC | To detect the genetic potential of staphylococcal isolates to produce a polysaccharide biofilm matrix. | The ica locus is critical for biofilm accumulation in many strains [23]. |

| Cyclo(Tyr-Val) | Cyclo(Tyr-Val), MF:C14H18N2O3, MW:262.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| L-Serine-13C3 | L-Serine-13C3, MF:C3H7NO3, MW:108.071 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualizing the Fibrotic Signaling Pathway Induced by Biofilms

The following diagram integrates the key molecular and cellular events, from bacterial adhesion to clinical contracture, as described in the literature [3] [22].

Mechanism Diagram: Biofilm-Induced Fibrotic Encapsulation

Biomaterial Engineering and Pharmacological Disruption of Profibrotic Pathways

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges in Surface Engineering

FAQ 1: Why does my in vitro macrophage assay not show a clear difference in cytokine expression between smooth and textured surfaces?

- Potential Cause: The surface properties of your test samples, specifically the hydrophilicity, may have degraded over time due to hydrocarbon contamination from the air, a process known as "biological aging." This can diminish the expected cellular response [25].

- Solution: Implement a surface activation protocol immediately prior to experiments. Techniques like UV photofunctionalization have been shown to restore surface hydrophilicity and remove hydrocarbon contaminants, revitalizing the bioactivity of the surface and ensuring a more robust cellular response [25].

FAQ 2: How can I ensure the surface topography of my experimental implants is consistent and accurately characterized?

- Potential Cause: Inconsistent fabrication methods or inadequate surface characterization. Manufacturing techniques for textured implants can be crude, and surfaces are often poorly characterized [26].

- Solution:

- Standardize Fabrication: For research-grade samples, use precise methods like anodic oxidation for nano-textures or certified sandblasting/acid-etching for micro-textures [27].

- Comprehensive Characterization: Employ a combination of:

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): For qualitative evaluation of micro- and nano-morphology [28] [12].

- Laser Confocal Microscopy / White Light Interferometry: For accurate 3D quantitative characterization of surface roughness parameters (e.g., S₠- average height, Sᵈʳ - developed interfacial area ratio) [28] [12] [26].

- Energy-Dispersive X-ray (EDX) Analysis: To verify the chemical and elemental composition of the surface [28].

FAQ 3: My animal model shows high variance in capsular thickness. What factors should I control?

- Potential Cause: Uncontrolled surgical variables or implant movement (rotation) within the pocket, which is influenced by surface topography [12].

- Solution:

- Surgical Precision: Standardize the implant pocket size and location across all subjects to minimize confounding variables.

- Account for Surface-Dependent Movement: Be aware that different topographies exhibit different levels of mobility. A study found that nanotexture and smooth surface implants had significantly increased movement compared to macrotexture implants. This variable should be measured and accounted for in your analysis [12].

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from preclinical studies on implant surface topography.

Table 1: Impact of Surface Topography on Capsule Formation in a Rodent Model (12 Weeks Post-Implantation) [12]

| Surface Topography | Capsule Thickness (µm) | Collagen Fiber Density (%) | Myofibroblast Infiltration (%) | TGF-β1 Expression (Optical Density) | Implant Movement (Change in Location) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smooth | 415.07 ± 19.74 | 67.8 ± 3.4 | 42.8 ± 3.4 | 0.95 ± 0.04 | 38.75° ± 15.56° |

| Macrotexture(Roughness: ~100 µm) | 261.53 ± 5.7 | 62.2 ± 6.1 | 25.2 ± 6.1 | 0.91 ± 0.05 | 3.50° ± 1.73° |

| Nanotexture(Roughness: ~6 µm) | 232.48 ± 14.10 | 46.2 ± 3.3 | 16.2 ± 3.3 | 0.80 ± 0.09 | 76.00° ± 24.01° |

Table 2: Comparison of Micro-scale vs. Nano-scale Surface Modifications [27]

| Aspect | Micro-Scale Modifications | Nano-Scale Modifications |

|---|---|---|

| Feature Size | 1 - 100 micrometers (µm) | 1 - 100 nanometers (nm) |

| Common Methods | Sandblasting, Acid Etching, Plasma Spraying | Anodization, Sol-Gel Coating, Chemical Vapour Deposition |

| Key Advantage | Cost-effective, extensive long-term clinical data | Enhanced protein adsorption, faster healing, biomimetic |

| Key Limitation | May trap bacteria; less efficient protein interaction | Higher cost, limited long-term data, complex manufacturing |

| Impact on Fibrosis | Higher capsule thickness and collagen density | Reduced capsule thickness and collagen density |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vivo Evaluation of Capsule Formation

This protocol is adapted from a study investigating capsule formation around implants with different surface topographies in a rodent model [12].

- Study Groups and Implants: Assign subjects into groups (e.g., n=8 per group). Use commercially available or custom-fabricated silicone implants with well-characterized surfaces:

- Surgical Implantation: Perform aseptic surgery to insert one implant per subject into a defined subcutaneous pocket. Standardize pocket size and location precisely across all subjects.

- Post-Op Monitoring and Measurement: At defined endpoints (e.g., 4 and 12 weeks):

- Implant Location: Periodically measure and record implant rotation or movement from the original position [12].

- Euthanasia and Explantation: Euthanize subjects and carefully retrieve the implant with the surrounding capsular tissue intact.

- Histological Processing and Staining:

- Immunohistochemical (IHC) Staining:

- Perform IHC staining for key fibrotic markers such as α-Smooth Muscle Actin (α-SMA) to identify myofibroblasts and TGF-β1 to assess pro-fibrotic signaling [12].

- Western Blot Analysis:

- Homogenize capsular tissue and use Western Blot to quantitatively compare the protein expression levels of fibrotic markers like TGF-β1 across the different study groups [12].

- Data Analysis: Use image analysis software to quantify staining results. Perform statistical analysis (e.g., ANOVA) to compare capsule thickness, collagen density, and marker expression between groups.

Protocol 2: Fabrication and In Vitro Testing of a Biomimetic Breast Tissue-Derived Surface

This protocol outlines the creation of a novel, biomimetic implant surface derived from human breast tissue and its initial in vitro validation [26].

- Surface Characterization and Modeling:

- Tissue Sampling: Obtain human breast adipose tissue samples with appropriate ethical approval and informed consent [26].

- Imaging: Image the tissue surface using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to observe the native topography, which typically appears as a layer of close-packed spheres (adipocytes) with a web of extracellular matrix fibers [26].

- 3D Profiling: Use Laser Confocal Microscopy to generate a high-resolution three-dimensional map of the adipose surface texture [26].

- Statistical Modeling: Analyze the surface measurement data to create a statistical model of the topography (e.g., "modelled adipose" surface) [26].

- Surface Fabrication:

- In Vitro Macrophage Response Assay:

- Cell Culture: Use a human macrophage cell line (e.g., THP-1 cells). Differentiate monocytes into macrophages prior to seeding [26].

- Seeding: Seed macrophages onto the novel biomimetic surfaces and control surfaces (e.g., smooth silicone) [26].

- Analysis:

- Cell Morphology: Use SEM to assess macrophage morphology and adhesion on the different surfaces [26].

- Gene Expression: After a set incubation period (e.g., 48 hours), extract RNA and perform Quantitative PCR (qPCR) to analyze the expression of key cytokines and polarization markers (e.g., IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6 for pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype; IL-10, TGF-β for pro-fibrotic M2 phenotype) [26].

- Cytokine Secretion: Collect cell culture supernatant and use Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) to quantify the secretion of proteins like TNF-α and IL-6 [26].

- Evaluation: A favorable, less fibrotic response is indicated by a downregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6) and/or a shift in macrophage polarization towards the M2 phenotype in response to the biomimetic surface compared to controls [26].

Foreign Body Response (FBR) Pathway

Integrated Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Investigating Implant Surfaces

| Item | Function/Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Medical-Grade Silicone (PDMS) | The base material for fabricating experimental breast implant shells and testing novel surface topographies [26]. |

| THP-1 Human Monocyte Cell Line | A widely used model for in vitro studies of the human immune response. Can be differentiated into macrophages to test surface-induced inflammatory and fibrotic responses [26]. |

| Antibodies for IHC/Western Blot | Essential for detecting and quantifying key proteins involved in fibrosis. Critical targets include α-SMA (for myofibroblasts) and TGF-β1 (a master regulator of fibrosis) [12]. |

| ELISA Kits (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) | Used to quantitatively measure the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines from macrophages cultured on different implant surfaces, indicating the intensity of the foreign body response [26]. |

| PCR Primers & Reagents | For quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis of gene expression changes in cells exposed to different surfaces. Key genes include those for fibrotic markers and cytokines [26]. |

| Histology Stains (H&E, Masson's Trichrome) | Standard dyes used on tissue sections to visualize overall capsule structure (H&E) and to quantify collagen deposition and density (Masson's Trichrome) [12]. |

| Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) | Instrument for high-resolution imaging of surface micro- and nano-morphology to ensure topographical features are as designed and to inspect cell morphology on surfaces [28] [12] [26]. |

| 3D Surface Profilometer | Instrument for quantitative, three-dimensional analysis of surface roughness parameters (e.g., Sâ‚, Sᵈʳ), which are critical for correlating topography with biological outcomes [28] [12]. |

| Cauloside D | Cauloside D, MF:C53H86O22, MW:1075.2 g/mol |

| Bromo-PEG7-Boc | Bromo-PEG7-Boc, MF:C21H41BrO9, MW:517.4 g/mol |

This technical support center provides resources for researchers investigating the use of soft silicone layers to mitigate the fibrotic encapsulation of breast implants. Fibrotic encapsulation, or capsular contracture, is a common complication where a thickened collagen capsule forms around the implant, potentially leading to pain, hardening, and deformity [29] [30]. The underlying mechanism involves a foreign body response (FBR) that activates myofibroblasts, which are scar-forming cells [31]. The mechanical properties of the implant surface, specifically its elastic modulus, play a critical role in driving this activation [30].

The foundational study by Noskovicova et al. demonstrated that coating conventionally stiff silicone implants (elastic modulus ~2 MPa) with a soft silicone layer (elastic modulus ~2 kPa) significantly reduced collagen deposition and myofibroblast activation in a murine model [30]. The proposed mechanism is that soft surfaces reduce intracellular stress in fibroblasts, minimizing the recruitment of αv and β1 integrins and subsequent activation of pro-fibrotic Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF-β) signaling pathways [30]. This resource center consolidates experimental protocols, troubleshooting guides, and key reagents to facilitate replication and advancement of this promising approach.

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathway involved in this process, contrasting the cellular responses to stiff versus soft silicone surfaces.

Diagram 1: Signaling Pathway in Fibrotic Encapsulation. This diagram contrasts the pro-fibrotic cellular response triggered by stiff silicone surfaces with the suppressed response from soft surfaces or pharmacological inhibition.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

Q1: Our soft silicone coatings are exhibiting incomplete or non-uniform curing, leading to tacky surfaces and compromised mechanical integrity. What are the causes and solutions?

A: Incomplete curing is a frequent issue that can invalidate modulus measurements and biological results.

- Cause (Incorrect Mixing Ratios): Two-part silicone systems require precise stoichiometric ratios for complete cross-linking. Deviations disrupt the polymerization network [32].

- Solution: Always use a high-precision digital scale to measure components. For critical applications, consider using pre-measured kits from suppliers to ensure consistency [32].

- Cause (Insufficient Curing Time/Temperature): Rushing the process or using incorrect temperatures prevents the material from reaching its ultimate physical properties [33] [32].

- Solution: Strictly follow the manufacturer's data sheet for recommended curing times and temperatures. Note that elevated temperatures accelerate curing, but the reaction coordinate (a function of time and temperature) must be calculated to ensure full cure [33]. Allow the material to cure at a stable, controlled room temperature for the full recommended duration before testing or use.

- Cause (Material Incompatibility): The soft coating material may be chemically incompatible with the stiffer substrate silicone.

- Solution: Ensure both the base implant and soft coating are from the same silicone chemistry family (e.g., platinum-catalyzed). Perform adhesion tests on small samples before full-scale fabrication.

Q2: We are encountering air bubbles trapped within our soft silicone layers during fabrication. How can this be prevented?

A: Air bubbles create defects that act as stress concentrators and can be misinterpreted as biological voids in histology.

- Cause (Poor Mixing & Pouring Technique): Aggressive stirring or rapid pouring of the liquid prepolymer introduces and traps air [34] [32].

- Solution: Mix the components slowly and deliberately to minimize air entrainment. Pour the mixture in a thin, steady stream against the side of the mold container [32].

- Cause (Inadequate Degassing): Failing to remove entrained air before curing is a primary cause.

- Solution: Implement vacuum degassing. Place the mixed silicone in a vacuum chamber immediately after mixing and apply a vacuum until the volume stops expanding and bubbles collapse (typically 2-5 minutes) [34] [32].

Q3: The adhesion between our soft silicone layer and the underlying stiff substrate is weak, leading to delamination during handling or implantation.

A: Weak interfacial adhesion is a critical failure point for layered implants.

- Cause (Overcuring of the First Layer): If the base silicone implant is fully cured (its reaction coordinate Ï„ >> 1), it presents a chemically inert surface with few available sites for the soft coating to bond with [33].

- Solution: Employ a staged curing process. Apply the soft coating while the base substrate is only partially cured (the "green stage"), allowing polymer chains to cross-link across the interface. The reaction coordinate framework can be used to determine the optimal window for bonding [33].

- Cause (Absence of a Mechanical Interlock): A perfectly smooth interface provides little surface area for adhesion.

- Solution: Modify the surface topography of the stiff substrate before applying the soft layer. This can be achieved by using textured molds or lightly abrading the surface to create micro-scale anchors.

Q4: Our in-vivo experiments show high variability in capsule thickness despite using soft layers. What factors beyond modulus could be influencing this?

A: Fibrotic encapsulation is a multifactorial process. Key considerations include:

- Cause (Subclinical Infection/Biofilm): Bacterial contamination, even at levels that do not cause clinical infection, is a well-documented trigger for chronic inflammation and capsular contracture [29].

- Solution: Adhere to strict aseptic surgical techniques during implantation. Some studies suggest the use of antibiotic irrigation or antimicrobial-coated implants, though their efficacy is an area of active research [29].

- Cause (Implant Surface Topography): While your focus is modulus, surface texture (smooth, micro-textured, nano-textured) independently modulates the immune response. Nano-textured surfaces have shown promise in reducing myofibroblast infiltration and promoting a more favorable immune profile [29].

- Solution: Control for surface topography in your experimental design. Consider using implants with identical topography but varying modulus to isolate the mechanical effect.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Researchers

Q1: What is the quantitative evidence that soft silicone layers reduce fibrosis?

A: The primary evidence comes from a key murine model study which reported that a soft silicone layer (~2 kPa) on a stiff substrate (~2 MPa) significantly reduced collagen deposition and myofibroblast activation compared to stiff implants alone. Furthermore, pharmacological inhibition of the mechanical activation of TGF-β via the small molecule CWHM-12 produced a similar anti-fibrotic effect [30].

Q2: How does implant elastic modulus mechanically activate TGF-β?

A: On stiff surfaces, fibroblasts generate high intracellular contractile forces. This mechanical stress promotes the recruitment of αv and β1 integrins to focal adhesions. These integrins bind to the Latency-Associated Peptide (LAP) of latent TGF-β, inducing a conformational change that releases active TGF-β, which then drives myofibroblast differentiation and fibrosis [30]. Soft surfaces reduce the cellular contractile forces, preventing this mechano-activation pathway.

Q3: Are there pharmacological strategies that mimic the effect of soft surfaces?

A: Yes, the small-molecule inhibitor CWHM-12 antagonizes the binding of αv integrin to LAP. In the referenced study, treatment with CWHM-12 suppressed active TGF-β signaling, myofibroblast activation, and fibrotic encapsulation around stiff subcutaneous implants in mice, effectively producing a "chemical softening" effect [30].

Q4: How can we accurately measure the elastic modulus of our silicone layers?

A: The gold standard is to use a dynamic mechanical analyzer (DMA) or a tensile tester to perform uniaxial or biaxial tensile tests on pure, bulk samples of the cured material. For thin coatings, nanoindentation may be more appropriate. Ensure samples are fully cured and tested under standardized environmental conditions. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from the literature.

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of Implant Surface Properties on Fibrotic Outcomes

| Implant Type / Treatment | Elastic Modulus | Key Measured Outcome | Experimental Model | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Silicone (Control) | ~2 MPa | Baseline collagen deposition & myofibroblast activation | Mouse subcutaneous implant | [30] |

| Soft Silicone-Coated | ~2 kPa | Reduced collagen & myofibroblast activation | Mouse subcutaneous implant | [30] |

| CWHM-12 Treatment (on stiff implant) | N/A (Pharmacological) | Suppressed TGF-β signaling & fibrosis | Mouse subcutaneous implant | [30] |

| L-Microtextured Implant | N/A (Topography) | Increased tissue remodeling, reduced myofibroblasts | Human study (n=30, 5 groups) | [29] |

| Smooth Implant | N/A (Topography) | Highest incidence of capsular contracture | Human study (n=30, 5 groups) | [29] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabricating Soft Silicone-Coated Implants

This protocol describes the creation of a model implant with a tunable soft surface layer.

Materials:

- Base Silicone Elastomer (e.g., for stiff core, ~2 MPa)

- Soft Silicone Elastomer (e.g., for coating, Shore A hardness <30, target modulus ~2 kPa)

- Precision Digital Scale

- Vacuum Chamber and Pump

- Mold (e.g., disk-shaped for standardized testing)

- Curing Oven (if temperature-accelerated)

Method:

- Fabricate Stiff Core: Mix the base silicone components in the precise ratio recommended by the manufacturer. Degas in a vacuum chamber until no bubbles remain. Pour into the mold and cure partially. The key is to bring the reaction coordinate (Ï„) of the base to a point just before full gelation to ensure optimal adhesion for the next layer [33].

- Apply Soft Coating: Mix the soft silicone components thoroughly. Degas the mixture completely. Pour the soft silicone directly onto the partially cured stiff core.

- Co-Curing: Allow the layered structure to cure fully together. This enables polymer chains from both layers to interdiffuse and cross-link at the interface, creating a strong bond.

- Post-Processing: Demold the final implant and inspect for defects like bubbles or delamination. Store in a clean, dry environment until implantation.

The workflow for this fabrication process and the subsequent in-vivo validation is outlined below.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Implant Fabrication and Validation. This diagram outlines the key steps from creating the layered silicone implant to its in-vivo evaluation and final data analysis.

Protocol: Quantifying the Foreign Body Response In-Vivo

Materials:

- Experimental Implants (Soft-coated) & Control Implants (Stiff)

- Animal Model (e.g., C57BL/6 mice, approved by IACUC)

- Surgical tools, sutures, anesthetic, analgesic

- Tissue fixation and processing equipment

- Antibodies for immunohistochemistry (e.g., α-SMA for myofibroblasts, CD68 for macrophages, CD31 for vasculature)

Method:

- Implantation: Following approved ethical guidelines, implant disks of test and control materials subcutaneously in the dorsum of the animal. Each animal can host multiple implants in separate pockets.

- Explanation: At predetermined endpoints (e.g., 2, 4, and 8 weeks), euthanize the animals and carefully explant the constructs with the surrounding capsular tissue.

- Histological Processing: Fix tissues in formalin, embed in paraffin, and section. Perform standard staining (e.g., H&E for general morphology, Masson's Trichrome for collagen).

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): Stain sections with specific antibodies to identify key cell types and activation states.

- Quantitative Analysis:

- Capsule Thickness: Measure at multiple points around the implant circumference from H&E or Trichrome stains.

- Collagen Density: Quantify the blue-stained area in Trichrome sections using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ).

- Myofibroblast Presence: Count α-SMA positive cells at the implant-tissue interface.

- Immune Cell Profiling: Quantify M1 (pro-inflammatory) vs. M2 (pro-repair) macrophage polarization using specific markers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for Investigating Soft Silicone Layers

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Research | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Soft Silicone Elastomer | Creates the low-modulus surface layer to reduce mechanical activation. | Look for a Shore 00 hardness rating or an Elastic Modulus in the low kPa range (e.g., ~2 kPa). "Gel-type" soft SR with Shore A below 30 is also relevant [35] [30]. |

| Stiff Silicone Substrate | Serves as the base implant material and experimental control. | Standard medical-grade silicone with an Elastic Modulus of ~1-3 MPa [30]. |

| CWHM-12 Inhibitor | A small-molecule pharmacological tool to inhibit αv integrin binding to LAP, suppressing TGF-β activation. | Used for in-vivo studies to mimic the "soft surface" effect chemically and validate the mechano-transduction pathway [30]. |

| α-SMA Antibody | Primary antibody for Immunohistochemistry to identify and quantify activated myofibroblasts. | Critical for measuring the terminal effector cell in the fibrotic response. |

| TGF-β Signaling Assay Kits | To quantify the level of active TGF-β signaling in the peri-implant tissue (e.g., via pSMAD2/3 levels). | Validates the molecular mechanism linking mechanics to cell activation. |

| Vacuum Degassing Chamber | Essential equipment for removing air bubbles from liquid silicone before curing to ensure defect-free samples. | Prevents experimental artifacts and ensures consistent mechanical properties [34] [32]. |

| 3-epi-Digitoxigenin | 3-epi-Digitoxigenin, CAS:545-52-8, MF:C23H34O4, MW:374.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Phytochelatin 5 | Phytochelatin 5 (PC5) | Research-grade Phytochelatin 5, a heavy metal-detoxifying plant peptide. For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Scientific Background: TGF-β Signaling in Fibrotic Encapsulation

The fibrotic encapsulation of medical implants, such as silicone breast implants, is a common complication that often necessitates revision surgery. This process, known as the Foreign Body Response (FBR), is a complex immune reaction that culminates in the formation of a dense, collagenous capsule around the implant, a process clinically recognized as capsular contracture [36] [3]. Central to this pathological fibrosis is the cytokine Transforming Growth Factor-Beta (TGF-β).

Upon implant placement, tissue injury initiates a wound healing response. Platelets are among the first responders, releasing growth factors including TGF-β, which orchestrates subsequent inflammatory and proliferative phases [36]. The persistence of the implant leads to chronic inflammation, characterized by the activation of macrophages. These macrophages attempt to phagocytose the implant; when unsuccessful, "frustrated phagocytosis" occurs, leading to their fusion into foreign body giant cells (FBGCs) and sustained pro-inflammatory signaling [36] [3]. A critical event is the shift in macrophage polarization from a pro-inflammatory (M1) phenotype to a pro-fibrotic (M2) phenotype. M2 macrophages are a major source of active TGF-β [3].

TGF-β drives fibrosis by activating resident fibroblasts, prompting their differentiation into myofibroblasts. These cells are identified by the expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and are responsible for excessive deposition and remodeling of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, primarily collagen types I and III, which form the fibrous capsule [3]. The primary signaling pathway for TGF-β involves the binding to and activation of transmembrane TGF-β receptor I (TGF-βRI) and II (TGF-βRII) complexes, which then phosphorylate downstream SMAD transcription factors (SMAD2/3) that translocate to the nucleus to initiate pro-fibrotic gene expression [15] [37]. Given its pivotal role, the TGF-β pathway presents a prime therapeutic target for mitigating fibrotic encapsulation.

The following diagram illustrates the key cellular and molecular events in the foreign body response and the points of intervention for TGF-β-targeting therapies:

Targeting the Pathway: Mechanisms of TGF-β Inhibition

Two primary therapeutic strategies for inhibiting TGF-β signaling are Small-Molecule TGF-βRI Inhibitors and Integrin Antagonists. Their mechanisms of action are distinct yet converge on the same goal of reducing fibrotic signaling.

A. Small-Molecule TGF-βRI Inhibitors

These compounds are designed to directly target the intracellular kinase domain of the TGF-β receptor I (TGF-βRI, also known as ALK5), competitively inhibiting its ATP-binding site. This blockade prevents the receptor from phosphoryating its downstream SMAD2/3 proteins, thereby interrupting the canonical pro-fibrotic signaling cascade [38]. Structural biology and X-ray crystallography have been instrumental in designing these inhibitors for high selectivity and potency [38] [39].

B. Integrin Antagonists

Integrins are cell surface receptors that play a crucial role in the activation of TGF-β. TGF-β is secreted in a latent complex (LLC) bound to the extracellular matrix. Specific integrins, notably αVβ6 and αVβ8, are key mediators of latent TGF-β activation. The αVβ6 integrin, expressed on epithelial cells, binds to the RGD motif in the Latency-Associated Peptide (LAP) and exerts mechanical force to change LAP's conformation, releasing the active TGF-β cytokine. The αVβ8 integrin, expressed on immune cells like macrophages, employs proteolytic activation via membrane-type MMPs (e.g., MMP14) to liberate active TGF-β [15] [37]. Antagonists blocking these integrins prevent the initial release of active TGF-β, acting further upstream in the pathway [40].

The diagram below details the TGF-β signaling pathway and the precise points of inhibition for these two classes of therapeutics:

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below summarizes key reagents used in research targeting the TGF-β pathway for anti-fibrotic studies.

| Reagent Category | Example(s) | Primary Function / Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Small-Molecule TGF-βRI Inhibitors | Galunisertib (LY2157299), SB-431542, CWHM-12 (representative class) [38] | Selective ATP-competitive inhibitors of the TGF-βRI (ALK5) kinase, blocking downstream SMAD2/3 phosphorylation. |

| Integrin Antagonists | Anti-αVβ6/αVβ8 mAbs, Cilengitide (RGD-mimetic) [40] [37] | Block integrin-mediated activation of latent TGF-β complexes, preventing the release of the active cytokine. |

| SMAD Reporter Assays | SMAD-responsive luciferase constructs (CAGA box, SBE) [38] | Measure the transcriptional activity of the canonical TGF-β/SMAD signaling pathway in cells. |

| Antibodies for Fibrosis Markers | Anti-α-SMA, Anti-Collagen I/III, Anti-phospho-Smad2/3 [3] | Detect and quantify myofibroblast differentiation, ECM deposition, and pathway activation via IHC, IF, or Western Blot. |

| Latent TGF-β Activation Kits | Commercial ELISA-based kits | Quantify levels of active vs. total TGF-β in cell culture supernatants or tissue lysates. |

Experimental Protocols

A. Protocol 1: Assessing Anti-Fibrotic Efficacy in anIn VitroFibroblast Activation Assay

This protocol is used to test the efficacy of TGF-β inhibitors on preventing fibroblast-to-myofibroblast differentiation.

- Cell Seeding: Plate human dermal fibroblasts (e.g., HDFs) in multi-well plates (e.g., 12 or 24-well) at a density of 5 x 10^4 cells/mL in standard growth medium. Allow cells to adhere overnight.

- Pre-treatment (Optional): Pre-incubate cells with your test compounds (e.g., TGF-βRI inhibitor or integrin antagonist) for 1-2 hours. Prepare a dilution series of the inhibitor in serum-free or low-serum medium.

- Stimulation: Replace the medium with fresh medium containing 2-5 ng/mL of recombinant active TGF-β1 to induce differentiation. Maintain the same concentration of your test inhibitor in the treatment wells. Include controls:

- Negative Control: Cells in medium only (no TGF-β1, no inhibitor).

- Positive Control: Cells with TGF-β1 only (no inhibitor).

- Vehicle Control: Cells with TGF-β1 + DMSO/equivalent solvent.

- Incubation: Culture the cells for 48-72 hours.

- Analysis:

- Protein Analysis (Western Blot): Lyse cells and analyze lysates via Western Blot for fibrotic markers: α-SMA (key outcome), phospho-Smad2/3 (pathway activation), and total Smad2/3 (loading control). Compare band intensity between treated and control groups [3].

- Immunofluorescence (IF): Fix cells, permeabilize, and stain for α-SMA (primary antibody) with a fluorescent secondary antibody. Use DAPI for nuclei. Visualize and quantify fluorescence intensity or the percentage of α-SMA-positive cells using fluorescence microscopy [3].

- Gene Expression (qRT-PCR): Extract RNA, synthesize cDNA, and perform qPCR for genes such as ACTA2 (α-SMA), COL1A1, and COL3A1. Normalize to housekeeping genes (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB) and express as fold-change relative to the positive control [3].

B. Protocol 2: Evaluating Compound Efficacy in anIn VivoMouse Model of Implant Fibrosis

This protocol outlines the key steps for testing anti-TGF-β therapies in an animal model of fibrotic encapsulation.

- Implant Preparation:

- Use small discs of medical-grade silicone (e.g., 5mm diameter).

- For localized drug delivery, implants can be coated with a matrix (e.g., poloxamer hydrogel, fibrin sealant) containing the test inhibitor (e.g., a TGF-βRI inhibitor) or a vehicle control [3].

- Surgery:

- Anesthetize mice according to your institutional animal care protocol.

- Make a small dorsal incision and create a subcutaneous pocket.

- Insert the prepared silicone implant into the pocket.

- Close the wound with sutures or clips.

- Administer post-operative analgesics.

- Systemic Dosing (Alternative to Coating): If testing systemic administration, begin dosing via intraperitoneal (IP) injection or oral gavage according to the compound's pharmacokinetic profile, starting on the day of surgery and continuing for the study duration.

- Study Duration and Endpoint: Maintain animals for 2-8 weeks to allow for mature capsule formation.

- Tissue Harvest and Analysis:

- Euthanize mice and carefully explant the silicone disc with the surrounding fibrous capsule intact.

- Capsule Thickness Measurement: Fix explants in formalin, process for paraffin embedding, and section. Stain with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) for general histology and Masson's Trichrome or Picrosirius Red to visualize collagen. Measure capsule thickness in multiple locations per section using image analysis software [36] [3].

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): Perform IHC on tissue sections for α-SMA (to identify myofibroblasts) and phospho-Smad2/3 (to confirm pathway inhibition in the treatment group) [3].

- Hydroxyproline Assay: Hydrolyze a portion of the capsule and use a hydroxyproline assay as a biochemical measure of total collagen content [3].

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Q1: My test compound shows excellent efficacy in the in vitro fibroblast activation assay but fails to reduce capsule thickness in vivo. What could be the reason?

- A1: This is a common translational challenge. Consider the following:

- Bioavailability: The compound may have poor penetration into the dense, avascular fibrotic tissue surrounding the implant. Check the compound's distribution profile.

- Pharmacokinetics (PK): The half-life of the compound in vivo might be too short to maintain effective concentrations at the target site. Conduct PK studies to guide dosing frequency.

- Redundancy in Pathways: In vivo, multiple parallel pro-fibrotic pathways (e.g., PDGF, IL-13) may be activated, which can compensate for the inhibited TGF-β pathway. Consider combination therapies.

- Timing of Intervention: The therapeutic window may have been missed. Administering the inhibitor during the early inflammatory phase might be more effective than during later fibrotic stages.

Q2: In my in vitro assays, I observe high variability in α-SMA expression between technical replicates when stimulating with TGF-β. How can I improve consistency?

- A2:

- Cell Passage Number: Use fibroblasts at low, consistent passage numbers (e.g., P3-P8). High-passage cells can senesce and lose their responsiveness to TGF-β.

- Serum Batch: Use the same batch of fetal bovine serum (FBS) for an entire study, as different lots can have varying levels of endogenous growth factors that influence baseline fibroblast activity.

- TGF-β Preparation: Always use a fresh aliquot of recombinant TGF-β and ensure it is properly diluted and mixed to achieve a uniform concentration across all wells. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

- Cell Density: Ensure cells are seeded at a highly consistent density to achieve uniform confluence at the time of stimulation.

Q3: What are the key controls needed for a rigorous in vivo implant study?

- A3: A well-designed study should include:

- Sham Control: Animals undergo the same surgical procedure without implant insertion to account for baseline wound healing.

- Vehicle-Control Implant Group: Animals receiving an implant coated with/dosed with the delivery vehicle only (e.g., DMSO, saline).

- Treatment Group(s): Animals receiving the implant with the active test compound.

- Reference Compound Group (if available): Animals treated with a known anti-fibrotic agent (e.g., a glucocorticoid like Triamcinolone) to validate the model's responsiveness [3].

Q4: How can I confirm that an integrin antagonist is working in my system and not just causing general cytotoxicity?

- A4:

- Viability Assay: Perform a standard cell viability assay (e.g., MTT, CCK-8) alongside your functional assay to rule out cytotoxic effects at the working concentration.

- Measure Active TGF-β: Use an ELISA specific for active TGF-β (not total TGF-β) on cell culture supernatants. A successful αVβ6/αVβ8 antagonist should significantly reduce the level of active TGF-β detected after latent complex stimulation, without affecting cell viability [37].

- Downstream Readout: Confirm reduced phosphorylation of Smad2/3, which is a specific downstream event of TGF-β pathway activation.

This technical support center is designed for researchers working within the field of breast implant bioengineering, specifically focusing on the challenge of preventing fibrotic encapsulation. Fibrosis, or capsular contracture, remains a primary cause of implant failure, often necessitating revision surgery. This process is driven by an excessive foreign body response (FBR), a complex cascade initiated upon implantation. At the heart of this response are macrophages, innate immune cells with remarkable plasticity. Their polarization state—toward pro-inflammatory (M1) or pro-healing (M2) phenotypes—critically influences whether the outcome is destructive fibrosis or harmonious integration [3] [36] [41]. This resource provides targeted troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and detailed protocols to aid in the development and testing of immunomodulatory surface coatings designed to steer macrophage responses toward positive outcomes and mitigate fibrotic encapsulation.

Core Concepts & Troubleshooting Guides

The Macrophage Polarization Balance in FBR