Predicting and Controlling Biomaterial-Host Interactions: A Roadmap to Overcome Response Variability

This article addresses the critical challenge of variability in host responses to biomaterials, a major hurdle in clinical translation for researchers and drug development professionals.

Predicting and Controlling Biomaterial-Host Interactions: A Roadmap to Overcome Response Variability

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of variability in host responses to biomaterials, a major hurdle in clinical translation for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational biological sources of this variability, from individual immune profiles to biomaterial physicochemical properties. The scope encompasses novel methodological frameworks like 'bottom-up' biomaterial design and AI-driven predictive modeling, alongside troubleshooting strategies for immune modulation and personalization. Finally, it evaluates advanced in silico and in vitro validation techniques designed to reliably predict in vivo performance and facilitate comparative analysis of next-generation biomaterials.

Decoding the Sources of Variability: From Biological Systems to Material Properties

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is understanding macrophage polarization (M1/M2) critical for the success of my biomaterial implant?

Macrophage polarization is a pivotal determinant of biomaterial fate. The dynamic equilibrium between pro-inflammatory M1 and pro-healing M2 phenotypes directly dictates the balance between destructive inflammation and constructive tissue regeneration [1] [2].

- M1 Macrophages: Induced by stimuli like LPS and IFN-γ, they are characterized by the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) and markers like iNOS and CD80. They initiate necessary inflammatory responses but can lead to chronic inflammation, fibrous encapsulation, and implant failure if their activity is prolonged [3] [4].

- M2 Macrophages: Induced by signals like IL-4 and IL-13, they express markers like CD206 and CD163 and secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β). They promote tissue repair, angiogenesis, and biomaterial integration [3] [2] [4].

A successful biomaterial facilitates a timely transition from a dominant M1 phenotype in the early stages to a dominant M2 phenotype in the later stages of healing [2].

Q2: Which physical properties of a biomaterial can I modify to influence macrophage behavior?

The physical cues of biomaterials are potent immunomodulators that can be engineered to guide macrophage polarization, offering a powerful strategy to reduce research variability stemming from ill-defined material properties [2].

- Stiffness: Macrophages tend to polarize toward an M1 phenotype on stiffer substrates and toward an M2 phenotype on softer substrates that mimic the elasticity of native tissues [2] [5].

- Topography and Surface Roughness: Micropatterned and nano-rough surfaces generally promote an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, while smooth surfaces can exacerbate pro-inflammatory M1 responses [2].

- Pore Architecture: Three-dimensional scaffold architectures, particularly those with larger pore sizes (e.g., 50×50×20 μm³), have been shown to promote an M2-like expression profile, whereas smaller pores can increase M1-associated markers [2] [6].

- Hydrophilicity: Hydrophilic surfaces typically reduce foreign body reactions and favor M2 polarization, while hydrophobic surfaces can increase protein denaturation and promote M1 responses [2].

Q3: My in vivo results do not match my in vitro predictions regarding the host response. What are the common culprits for this discrepancy?

This is a central challenge in translational research. Key culprits include:

- Oversimplified In Vitro Models: Standard in vitro cultures often use extreme polarizing conditions (e.g., high-dose LPS or IL-4) and lack the complexity of the in vivo immune cell crosstalk (e.g., with T cells, neutrophils) and dynamic cytokine milieu [2].

- Serum Protein Adsorption: The "protein corona" that instantly forms on a biomaterial upon implantation in vivo can completely mask the engineered surface properties you tested in vitro, altering how immune cells recognize the material [7].

- Mechanical Mismatch: The mechanical mismatch between your implant and the surrounding tissue creates a mechanical microenvironment not captured in standard 2D cultures, significantly influencing macrophage mechanosensing and response [8].

Q4: What are the key signaling pathways involved in macrophage polarization that I should analyze to validate my biomaterial's immunomodulatory effects?

Biomaterials influence macrophage fate through specific signaling pathways. Analyzing these is key to validating your material's design and ensuring consistent outcomes. The table below summarizes the core pathways.

Table 1: Key Signaling Pathways in Macrophage Polarization

| Pathway | Primary Inducers | Key Transcription Factors | Resulting Phenotype & Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| NF-κB / MAPK [1] [4] | LPS, TNF-α, DAMPs/PAMPs [1] | NF-κB, AP-1 | M1 Phenotype: Pro-inflammatory cytokine production (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) [4]. |

| JAK-STAT1 [3] [4] | IFN-γ | STAT1 | M1 Phenotype: iNOS expression, antimicrobial activity [3] [4]. |

| JAK-STAT6 [3] [4] | IL-4, IL-13 | STAT6, PPARγ | M2 Phenotype (M2a): Tissue repair, fibrosis, expression of CD206, arginase-1 [3] [4]. |

| PI3K-Akt [4] | Growth factors, IL-4 | Akt, mTOR | Dual Role: Can support both M1 (glycolysis) and M2 (metabolic reprogramming) polarization depending on context [4]. |

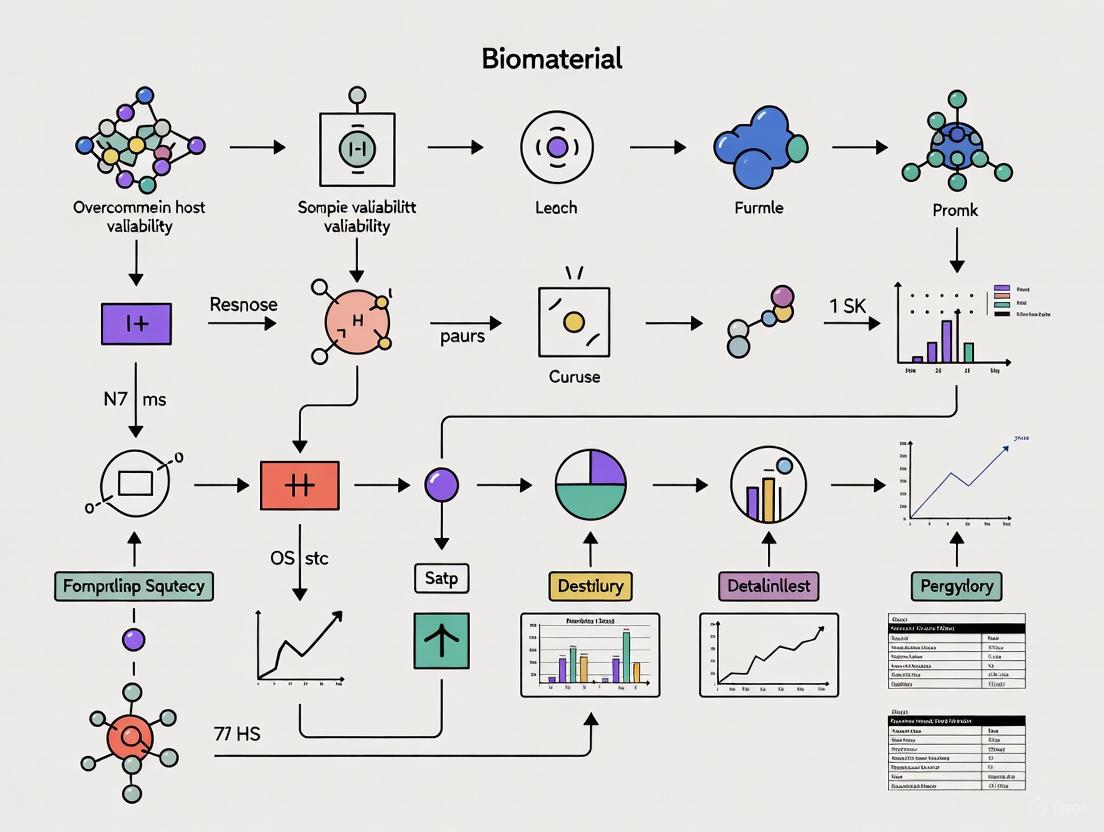

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and crosstalk between these key signaling pathways in macrophage polarization.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Uncontrolled Foreign Body Reaction and Fibrosis

A persistent pro-inflammatory response often leads to dense fibrous capsule formation, isolating the implant and causing failure [7] [5].

Investigation and Resolution Protocol:

Characterize the Immune Microenvironment:

- Method: Implant your biomaterial in a relevant animal model. At multiple time points (e.g., 3, 7, 14, 28 days), explant the tissue and perform:

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC)/Immunofluorescence (IF): Stain for M1 (iNOS, CD80) and M2 (CD206, ARG1) markers to quantify the M1/M2 ratio spatially and temporally [7].

- RNA Analysis: Use qPCR on explanted tissue to analyze the expression of key pro-inflammatory (TNF-α, IL-1β) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10, TGF-β) cytokines [1].

- Method: Implant your biomaterial in a relevant animal model. At multiple time points (e.g., 3, 7, 14, 28 days), explant the tissue and perform:

Modify Biomaterial Physicochemical Properties:

- Action: If analysis confirms chronic M1 dominance, redesign your biomaterial.

- Reduce Stiffness: If possible, tune the scaffold's elastic modulus to better match the target tissue [2].

- Alter Surface Topography: Introduce micro/nano-scale roughness or specific patterns known to promote M2 polarization [2] [5].

- Incorporate Bioactive Cues: Functionalize the material with anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-4) or specific ECM-derived peptides (e.g., RGD) to actively steer macrophages toward an M2 phenotype [1] [8].

- Action: If analysis confirms chronic M1 dominance, redesign your biomaterial.

Issue: High Variability in Macrophage Response Between Experimental Batches

Inconsistent outcomes can stem from uncontrolled variables in biomaterial fabrication or cell culture.

Investigation and Resolution Protocol:

Audit Your Material Characterization:

- Action: For every new batch of biomaterial, rigorously characterize:

- Documentation: Maintain a detailed log of all fabrication parameters (e.g., polymer lot, crosslinking time, temperature).

Standardize Your Cell-Based Assays:

- Cell Source: Use a consistent and well-characterized source of macrophages (e.g., primary human monocyte-derived macrophages from a specific donor pool or a specific cell line like THP-1). Document passage numbers and differentiation protocols meticulously [3].

- Serum Control: Use the same lot of fetal bovine serum (FBS) for an entire study to minimize variability introduced by serum-derived factors [7].

- Stimulation Consistency: Prepare stock solutions of polarizing agents (LPS, IFN-γ, IL-4) in single-use aliquots to avoid freeze-thaw cycles and degradation.

The following workflow diagram outlines a standardized experimental approach to minimize variability from material fabrication through to data analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Macrophage-Biomaterial Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiments | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| THP-1 Cell Line | A human monocytic cell line; can be differentiated into macrophages using PMA. | Provides a renewable, consistent cell source. Must ensure consistent differentiation protocols. Response may differ from primary cells [3]. |

| Primary Human Monocytes | Isolated from peripheral blood, these differentiate into macrophages (e.g., with M-CSF). | More physiologically relevant. High donor-to-donor variability must be accounted for in experimental design [3] [4]. |

| Polarizing Cytokines (IL-4, IL-13, IFN-γ, LPS) | Used to polarize macrophages toward specific (M1 or M2) phenotypes in vitro. | Use high-purity, endotoxin-free reagents. Aliquot to preserve activity. Concentration and timing are critical [3] [2] [4]. |

| Anti-CD68 / Anti-Iba1 Antibodies | Pan-macrophage markers for identifying total macrophage population in tissue sections (IHC/IF) [9]. | Validate antibodies for your specific species and application (IHC vs. IF). |

| Anti-iNOS / Anti-CD206 Antibodies | Classic markers for identifying M1 (iNOS) and M2 (CD206) polarized macrophages via IHC/IF or flow cytometry [2] [4]. | Be aware that macrophages exist on a spectrum; using multiple markers is more reliable than a single one. |

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | A common synthetic, biodegradable polymer used to fabricate 3D scaffolds for tissue engineering. | Easily tunable mechanical properties and architecture. Hydrophobic surface may need modification to enhance biocompatibility [7]. |

| Decellularized ECM Scaffolds | Natural biomaterials derived from tissues, retaining complex biochemical cues. | Highly bioactive and can promote favorable M2 polarization. Potential for batch-to-batch variability and immunogenicity if not properly decellularized [8] [7]. |

| RGD Peptide | A fibronectin-derived peptide used to functionalize biomaterial surfaces to promote cell adhesion. | Enhances integrin-mediated macrophage adhesion, which can influence polarization fate. The density and spatial presentation are critical [8]. |

| Sulfo Cy5.5-N3 | Sulfo Cy5.5-N3, MF:C46H53N6NaO10S3, MW:969.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Resveratrol-3-O-beta-D-glucuronide-13C6 | Resveratrol-3-O-beta-D-glucuronide-13C6, MF:C20H20O9, MW:410.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Our in vivo implant study shows high variability in fibrotic capsule thickness between test animals. What are the primary factors driving this outcome variability, and how can we control for them?

Several interrelated factors contribute to variability in fibrosis outcomes. To control for them, focus on the following:

- Biomaterial Surface Properties: The chemical, physical, and morphological characteristics of your biomaterial surface are a primary modulator of the FBR [10] [11]. Surface properties dictate the initial adsorption of host proteins (like fibrinogen and fibronectin), which in turn influences subsequent immune cell adhesion and activation [11]. Standardize and thoroughly characterize your material's surface properties (e.g., roughness, wettability, chemistry) between batches.

- Host Immune Cell Heterogeneity: The FBR is driven by a dynamic network of cells, notably macrophages and fibroblasts, which are not uniform populations [12] [13]. The balance between pro-inflammatory (M1) and pro-healing (M2) macrophages, as well as the activity of different fibroblast subpopulations, can significantly impact the degree of fibrosis [12] [11]. Use flow cytometry and transcriptional analysis to characterize the immune cell profile at the implant interface rather than relying solely on histological endpoints.

- Surgical Technique and Implantation Site: Inconsistent surgical procedures, including the degree of tissue injury and implantation technique, can introduce significant variability [11]. Implement a standardized surgical protocol and consider the specific physiological environment of the implantation site.

FAQ 2: We are observing inconsistent monocyte adhesion and macrophage fusion on our biomaterials in vitro. What could be causing this, and how can we improve the consistency of our cell culture models?

Inconsistencies in in vitro cell behavior often stem from the protein layer that spontaneously forms on the material prior to cell interaction.

- Protein Adsorption and the Vroman Effect: The types, concentrations, and conformations of proteins adsorbed to your biomaterial from the cell culture medium are critical determinants of cell adhesion [11]. This layer is dynamic, with proteins adsorbing and desorbing over time (the Vroman Effect). To improve consistency:

- Pre-condition materials: Pre-incubate all material samples in the relevant protein solution (e.g., serum) for a standardized duration before adding cells.

- Use defined media: Whenever possible, use cell culture media with defined protein compositions to reduce batch-to-batch variability of serum.

- Characterize the adsorbed layer: Utilize techniques like immunofluorescence or quartz crystal microbalance to confirm the consistency of the protein layer on your material surfaces.

FAQ 3: What are the key molecular and cellular markers we should track to reliably stage the Foreign Body Response in our animal models?

Reliable staging requires monitoring a combination of cellular and molecular markers across the timeline of the FBR. The table below summarizes key indicators.

Table 1: Key Markers for Staging the Foreign Body Response

| Stage of FBR | Timeline | Key Cellular Players | Characteristic Molecular Markers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Inflammation | First ~1-7 days | Neutrophils, Mast Cells, M1 Macrophages | TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, Histamine [12] [11] |

| Chronic Inflammation / FBGC Formation | ~1-4 weeks | Monocytes, M1/M2 Macrophages, Foreign Body Giant Cells (FBGCs) | IL-4, IL-13, CCL2 (MCP-1), iNOS (M1), CD206 (M2) [12] [11] |

| Granulation Tissue & Fibrosis | ~2 weeks onward | Myofibroblasts, Endothelial Cells, Macrophages | TGF-β1, α-SMA (alpha-smooth muscle actin), Collagen I/III, PDGF [12] [14] |

FAQ 4: How can we leverage computational tools to predict and manage variability in biomaterial-host interactions?

Machine learning (ML) is an emerging powerful tool to navigate the complex parameter space of biomaterial design and host response.

- Handling Multi-dimensional Data: ML can identify non-intuitive relationships between a biomaterial's input parameters (e.g., composition, surface topography, stiffness) and its in vivo output properties (e.g., extent of fibrosis, capsule thickness) [15].

- Accelerating Discovery: Supervised learning models can be trained on existing experimental data to predict the biological performance of new, untested biomaterials, drastically reducing the need for extensive and costly in vivo experimentation [15]. Start by building a structured dataset of your material properties and corresponding experimental outcomes to serve as a foundation for such models.

FAQ 5: What are the most promising strategic approaches for designing biomaterials that mitigate the FBR?

Current strategies focus on actively modulating the immune response rather than simply being inert.

- Immunomodulation: Incorporate anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10) or specific metabolic inhibitors into the biomaterial to steer the local immune microenvironment toward a pro-regenerative, anti-fibrotic state [14].

- Mechanical Property Tuning: Cells sense and respond to mechanical cues. Designing materials with stiffness that discourages fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition and dense collagen deposition can reduce fibrosis [13].

- Surface Engineering: Creating non-fouling surfaces that minimize protein adsorption (e.g., using zwitterionic hydrogels) can reduce the initial trigger for the FBR cascade [14]. Bio-inspiration, such as creating microtopographies that discourage FBGC formation, is also a viable path.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Isolating and Analyzing Peri-Implant Cells for FBR Staging

This protocol is adapted from recent studies investigating cellular drivers of fibrosis, including the role of skeletal stem cells and fibroblast subpopulations [12] [14].

Objective: To isolate and characterize the key cellular populations (immune cells and fibroblasts) from the tissue-biomaterial interface for precise staging of the FBR.

Materials:

- Explanted Sample: The biomaterial implant and the surrounding fibrous capsule tissue.

- Dissociation Reagents: Collagenase Type I and DNAse I in a suitable buffer like PBS or RPMI.

- Cell Staining: Fluorescently conjugated antibodies against F4/80 (macrophages), CD206 (M2 macrophage marker), α-SMA (myofibroblasts), and CD90 (fibroblasts). A viability dye (e.g., propidium iodide) is essential.

- Equipment: GentleMACS or similar tissue dissociator, flow cytometer, cell culture incubator.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Explanation & Tissue Processing: Surgically explain the biomaterial with its enclosing fibrous capsule. Gently separate the capsule tissue from the biomaterial surface using a scalpel, ensuring all interfacial tissue is collected.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Mince the tissue finely and place it in a digestion cocktail containing Collagenase Type I (e.g., 2 mg/mL) and DNAse I (e.g., 0.1 mg/mL). Digest for 30-60 minutes at 37°C with constant agitation. Using a GentleMACS dissociator can improve yield and consistency.

- Cell Isolation: Pass the digested tissue through a 70 µm cell strainer to obtain a single-cell suspension. Centrifuge to pellet the cells and lyse any red blood cells if necessary.

- Cell Staining & Flow Cytometry: Resuspend the cell pellet in FACS buffer. Incubate with antibody cocktails designed to identify your cell populations of interest (e.g., macrophages, fibroblasts). Include isotype controls. Analyze the stained cells using a flow cytometer.

- Data Analysis: Use flow cytometry software to identify and quantify the percentages of different cell populations (e.g., F4/80+ macrophages, F4/80+CD206+ M2 macrophages, CD90+α-SMA+ myofibroblasts). This provides a quantitative snapshot of the FBR stage.

Protocol 2: Quantifying Fibrotic Outcomes via Histomorphometry

Objective: To quantitatively assess the extent of fibrosis and capsule formation around an implanted biomaterial.

Materials:

- Tissue Sections: Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections containing the implant site.

- Staining Reagents: Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) for general morphology. Picrosirius Red for collagen deposition.

- Equipment: Light microscope, polarized light microscope (for Picrosirius Red), image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, QuPath).

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Tissue Sectioning: Section FFPE blocks to a thickness of 5-7 µm. Ensure sections are taken from the central region of the implant.

- Staining:

- Perform H&E staining following standard protocols to visualize overall tissue structure and cellularity.

- Perform Picrosirius Red staining to specifically highlight collagen fibrils.

- Image Acquisition:

- For H&E, capture bright-field images at standardized magnifications (e.g., 40x, 100x).

- For Picrosirius Red, capture images under both bright-field and polarized light. Under polarized light, thick, mature collagen fibers appear orange/red, while thinner, newer fibers appear green.

- Image Analysis:

- Capsule Thickness: Using H&E images, take multiple, perpendicular measurements of the fibrous capsule from the implant surface to the outer edge of normal tissue. Calculate the average and standard deviation.

- Collagen Deposition & Maturity: Using Picrosirius Red images, use color thresholding in image analysis software to quantify the total area of birefringence (both red and green) as a percentage of the total tissue area. The ratio of red (mature) to green (new) collagen can provide insight into the maturity of the fibrotic tissue.

Visualizing the FBR Cascade: Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflow

FBR Signaling Pathway

FBR Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table details key reagents and their functions for investigating the Foreign Body Response.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for FBR Investigation

| Research Reagent | Function / Target in FBR | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant IL-4 / IL-13 | Cytokines that drive macrophage fusion into Foreign Body Giant Cells (FBGCs) [11]. | Used in in vitro models to induce and study FBGC formation on biomaterial surfaces. |

| TGF-β1 Inhibitors | Blocks Transforming Growth Factor-beta 1 signaling, a master regulator of fibroblast activation and collagen production [12]. | In vivo administration or local release from biomaterials to test reduction of fibrotic capsule formation. |

| Anti-α-SMA Antibody | Immunostaining for Alpha-Smooth Muscle Actin, a marker for activated myofibroblasts [13]. | Identifying and quantifying the key effector cells in fibrotic encapsulation via immunohistochemistry. |

| Picrosirius Red Stain | Binds to collagen fibrils; allows for quantification of total collagen deposition and maturity under polarized light [12]. | Histological assessment of fibrosis extent and maturity around explanted biomaterials. |

| Fluorophore-conjugated Antibodies (F4/80, CD206, CD3) | Cell surface markers for macrophages (F4/80), M2 macrophages (CD206), and T-cells (CD3) [11]. | Flow cytometric immunophenotyping of the inflammatory cell infiltrate at the implant site. |

| Collagenase Type I/II | Enzymes for the digestion of collagenous tissue in the fibrous capsule. | Essential for creating single-cell suspensions from explanted tissue for downstream flow cytometry or cell culture. |

| Rediocide C | Rediocide C, MF:C46H54O13, MW:814.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Geninthiocin | Geninthiocin, MF:C50H49N15O15S, MW:1132.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Biomaterial Experiment Challenges

This guide addresses frequent issues encountered in biomaterials research, helping you identify potential causes and corrective actions to reduce variability in your results.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Biomaterial Experiments

| Problem | Potential Causes | Suggested Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High Protein Fouling | Suboptimal surface chemistry or energy; experimental conditions not mimicking physiological state [16]. | Tailor surface chemistry/functional groups; use controlled biofluid sources and physiological conditions (concentration, pH, ionic strength) [17] [16]. |

| Poor Cell Adhesion | Non-adhesive protein layer (e.g., albumin); insufficient surface roughness or inappropriate functional groups [18] [16]. | Modify surface with RGD peptides or collagen; optimize nano/micro-scale topography to promote focal adhesion [18] [19]. |

| Uncontrolled/Overly Fast Degradation | Biomaterial chemical composition (e.g., ester groups) highly susceptible to hydrolysis; mismatch between degradation rate and tissue healing [20]. | Select materials with stable moieties (e.g., amides) or crosslinking; design degradation profile to match tissue regeneration time [20] [19]. |

| Severe Foreign Body Reaction & Fibrosis | Material surface properties trigger sustained inflammation; surface topography promotes pro-fibrotic macrophage response [7] [21]. | Design surfaces with anti-fibrotic chemical moieties; modulate topography/chemistry to promote pro-regenerative M2 macrophage polarization [7] [17]. |

| Irreproducible Degradation Data | Mistaking material dissolution for degradation; relying only on inferential techniques (e.g., gravimetry) without chemical confirmation [20]. | Employ multiple, complementary techniques (e.g., SEC, NMR) to confirm chemical breakdown; follow ASTM guidelines precisely [20]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is my biomaterial triggering a severe inflammatory response? A severe inflammatory response is often linked to your biomaterial's surface properties. The chemical composition, topography, and surface energy directly influence initial protein adsorption, which in turn dictates immune cell activation. Furthermore, the degradation products of your material can be immunogenic. To mitigate this, focus on modulating surface chemistry and topography to promote a favorable immune response, such as encouraging anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage polarization [7] [17] [21].

2. How can I accurately measure biomaterial degradation without expensive equipment? While gravimetric analysis (mass loss) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) for surface morphology are common and cost-effective starting points, they can be misleading as they infer but do not confirm degradation. For conclusive evidence, these physical methods should be combined with techniques that monitor chemical changes. Solution viscosity can indicate molecular weight changes, and pH tracking of the degradation medium can confirm hydrolytic processes. Be aware that ASTM guidelines recommend methods like SEC for definitive molar mass evaluation [20].

3. What is the optimal surface roughness for promoting bone integration (osseointegration)? For bone tissue engineering, studies suggest that surface roughness at the nanoscale increases extracellular matrix (ECM) protein adsorption, which promotes osteoblast attachment and differentiation. While cell infiltration can occur with pores as small as 40 μm, optimal bone formation has been observed with larger pore diameters, around 325 μm, which allows for even cell distribution and reduces peripheral cell accumulation [18].

4. My experimental fouling results are inconsistent. What critical parameters should I control? Inconsistent fouling results often stem from variations in experimental conditions. To improve reproducibility, strictly control and document these parameters:

- Protein Source and Concentration: Use consistent, fresh biofluids, as age can alter protein conformation. Concentrations can dramatically affect adsorption profiles [16].

- Ionic Strength and pH: These affect protein charge and stability, thereby influencing adsorption [16].

- Temperature: Conduct experiments at physiological temperature (37°C) when possible [16].

- Characterization Technique: Be aware that the method itself (e.g., fluorescent labeling) can alter protein behavior [16].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Comprehensive In Vitro Degradation Assessment

This protocol provides a multi-faceted approach to assess biomaterial degradation, moving beyond simple mass loss.

Workflow Overview

Materials & Reagents

- Degradation Medium: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), simulated body fluid (SBF), or enzymatic buffers [20].

- Sterile Containers: For incubation of samples.

- Analytical Balances: Precision of 0.1% of total sample weight is recommended [20].

- Oven or Desiccator: For drying samples to a constant weight [20].

- Characterization Equipment: SEM, Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), FTIR, NMR, viscometer.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Pre-degradation Characterization: Record the initial dry mass, molecular weight, and chemical structure (via FTIR/NMR) of your biomaterial samples [20].

- Immersion: Immerse pre-weighed samples in the degradation medium (e.g., PBS at pH 7.4) in sterile containers. Maintain a consistent surface-area-to-volume ratio [20].

- Incubation: Place containers in an incubator at 37°C. The pH should be monitored and maintained at 7.4, unless testing for a specific biological environment [20].

- Sampling: Remove samples in triplicate at predetermined timepoints (e.g., days 1, 7, 14, 28, etc.). Gently rinse samples and dry to a constant weight before analysis [20].

- Post-sampling Analysis:

- Gravimetric Analysis: Measure mass loss:

(Initial Mass - Dry Mass at Time t) / Initial Mass * 100%. - Surface Morphology: Use SEM to visualize surface erosion, cracking, or porosity changes.

- Molecular Weight: Use SEC or solution viscosity to track the reduction in polymer chain length.

- Chemical Analysis: Use FTIR or NMR to confirm the breakage of chemical bonds (e.g., ester groups) and identify degradation by-products [20].

- Gravimetric Analysis: Measure mass loss:

Protocol 2: Systematic Evaluation of Protein Fouling

This protocol standardizes the critical initial step of protein adsorption to improve experimental consistency.

Materials & Reagents

- Protein Solution: Single protein (e.g., fibrinogen, albumin) or complex biofluid (e.g., blood serum). Use consistent, fresh sources [16].

- Buffer: e.g., PBS. Control ionic strength and pH meticulously [16].

- Detection Method: Radiolabels, fluorescent labels, or colorimetric assays (e.g., Micro BCA).

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Surface Preparation: Prepare biomaterial samples with identical surface properties and dimensions.

- Solution Incubation: Incubate samples with the protein solution under controlled conditions (37°C, static or flow conditions) for a set time [16].

- Rinsing: Gently rinse samples with buffer to remove loosely associated proteins.

- Protein Detection:

- Labeled Proteins: Directly measure radioactivity or fluorescence from the surface.

- Unlabeled Proteins: Elute adsorbed proteins using a detergent (e.g., 1% SDS) and quantify the concentration in the eluent using a colorimetric assay [16].

- Data Normalization: Normalize the amount of adsorbed protein to the surface area of the sample (e.g., ng/cm²).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Their Functions in Biomaterial Characterization

| Research Reagent / Material | Primary Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Standard aqueous medium for in vitro degradation studies, simulating physiological pH and ionic strength [20]. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Analytical technique to monitor changes in the molecular weight distribution of a biodegradable polymer over time [20]. |

| Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy | Detects changes in chemical bonds and functional groups on the biomaterial surface before and after degradation or protein interaction [20]. |

| RGD Peptide | A cell-adhesive peptide ligand that can be grafted onto biomaterial surfaces to promote specific integrin-mediated cell attachment [19]. |

| Enzymatic Buffers (e.g., with Lysozyme) | Used to study enzyme-mediated degradation pathways relevant to the in vivo environment [20]. |

| Acellular Dermal Matrix (e.g., HADM, PADM) | A natural biomaterial used as a positive control in in vivo studies for effective tissue integration and mild inflammatory response [7]. |

| Eupenifeldin | Eupenifeldin, MF:C33H40O7, MW:548.7 g/mol |

| Rabdoserrin A | Rabdoserrin A, MF:C20H26O5, MW:346.4 g/mol |

Advanced Strategy: Integrating Design of Experiments (DoE) and Machine Learning

To systematically overcome variability and optimize biomaterial properties, move beyond traditional one-factor-at-a-time approaches.

Relationship Between DoE, ML, and Biomaterial Development

- Adopt a DoE Workflow: Begin by using statistical Design of Experiments (DoE) to plan your studies. This involves identifying key factors (e.g., polymer composition, pore size, crosslinking density) and their levels, then running a controlled set of experiments to model their relationship with responses (e.g., degradation rate, tensile strength, cell viability). This maximizes information while minimizing the number of experimental runs [22].

- Leverage Machine Learning: For highly complex and multi-dimensional data (e.g., from high-throughput characterization), machine learning (ML) can identify non-linear relationships and hidden patterns that traditional statistics might miss. ML models can predict optimal biomaterial compositions and properties, drastically accelerating the discovery pipeline [15] [22].

- Combine Both Methods: Use DoE to generate high-quality, structured initial data. Then, apply ML to build predictive models from this data, which can then inform the next, more refined, round of experimental design. This synergistic approach is a powerful future direction for the field [15] [22].

Core Mechanisms: How Host Factors Influence Biomaterial Response

FAQ: Why do age and sex cause variability in host responses to biomaterials?

Biological sex and age are significant sources of variability in immune responses, which directly influence how a host reacts to an implanted biomaterial. These factors affect cytokine production, immune cell populations, and the overall inflammatory environment [23].

- Sex-Based Differences: Females typically mount stronger innate and adaptive immune responses than males. This includes higher antibody responses, interferon activity, and T cell numbers. This can make females more susceptible to autoimmune diseases but also leads to more robust responses to biomaterials, vaccines, and infections [23] [24].

- Age-Based Differences: Aging is associated with immunosenescence, which includes a decline in naive T cells and dysregulation of the tissue microenvironment. Older individuals often exhibit delayed macrophage recruitment and altered proinflammatory profiles following implantation [23].

- The Estrogen Paradox: In some diseases, such as pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), sex hormones create a complex phenomenon. For example, estrogen may contribute to increased disease susceptibility in females while also conferring a survival advantage, a situation that can be modeled using advanced biomaterial systems [25].

FAQ: What is the clinical evidence that these factors matter?

Numerous clinical and pre-clinical observations confirm the critical role of host factors. For instance, the immune response to six common biomaterials (e.g., agarose, alginate, chitosan, CMC, GelMA, and collagen) showed clear sex and age-related heterogeneity in transcriptomic profiles after blood contact [23]. Furthermore, in respiratory diseases like PAH, a clear sexual dimorphism exists, with females being four times more likely to be diagnosed but having better survival rates than males [25].

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge: Inconsistent Cell Activation in Response to Biomaterial Stiffness

Problem: When studying fibroblast activation on hydrogels of varying stiffness, results are inconsistent and not reproducible.

Solution: Consider the sex of the cell source and the composition of the serum used in your culture media.

- Step 1: Report Cell Sex. Always note the biological sex of the primary cells used. Male and female human pulmonary arterial adventitial fibroblasts (hPAAFs) respond differently to identical mechanical cues [25].

- Step 2: Standardize Serum Source. Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) has batch-to-batch variability and undefined levels of sex hormones. For greater consistency, use human serum pooled by sex and age.

- Example: Female hPAAFs showed a stiffness-dependent activation profile only when cultured in younger female serum (from donors <50 years old) or when older female serum was supplemented with estradiol. Male hPAAFs, however, responded to stiffness increases regardless of serum composition [25].

- Step 3: Use Dynamic Biomaterials. Employ biomaterials that can mimic disease progression, such as dynamically stiffening PEGαMA hydrogels, to model how cells respond to changes in their mechanical environment [25].

Challenge: Unpredictable Immune Reactions to Implanted Biomaterials

Problem: An implant elicits a highly variable immune response (e.g., severe inflammation or fibrosis) across a test population.

Solution: Stratify test subjects by age and sex during pre-clinical evaluation and select biomaterial type based on the desired immune response.

- Step 1: Pre-screen Biomaterial Immunogenicity. Use an ex vivo human whole blood incubation model to profile the immune response to different biomaterials across donors of different ages and sexes [23].

- Step 2: Select Biomaterials by Immune Profile. Research shows that biomaterial ingredients elicit specific immune responses. For example:

- Step 3: Incorporate Immune Modulators. Engineer biomaterials to release immunomodulatory factors, such as anti-inflammatory cytokines, to promote a tolerogenic immune response and mitigate adverse reactions [26].

Key Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Ex Vivo Analysis of Blood-Biomaterial Interactions

This protocol, adapted from a 2021 study, details how to profile the immuno-biocompatibility of a biomaterial while accounting for donor age and sex [23].

1. Blood Collection and Preparation:

- Collect venous blood from healthy human volunteers, stratified into age/sex groups (e.g., young group: 20-39 years old; elderly group: 40-59 years old). Include at least 5 males and 5 females per group.

- Use anticoagulants like sodium citrate or EDTA. Keep samples at room temperature and process within 2 hours.

2. Biomaterial Coating:

- Prepare biomaterial solutions (e.g., 0.5% w/w in appropriate solvents).

- Coat well plates with 100 µL of each solution and allow them to dry under sterile conditions.

3. Whole Blood Incubation:

- Add 1 mL of fresh whole blood to each coated well.

- Incubate for 4-6 hours at 37°C with 5% CO₂.

4. RNA Sequencing and Analysis:

- Collect blood post-incubation for RNA extraction.

- Perform RNA-seq and subsequent bioinformatic analysis (e.g., PCA, differential gene expression, leukocyte profiling) to identify ingredient-, sex-, and age-specific immune signatures.

Detailed Protocol: Testing Cell Response to Dynamic Stiffening

This protocol describes a method to study sex-specific fibroblast activation in response to microenvironment stiffening, mimicking disease progression [25].

1. PEGαMA Hydrogel Synthesis and Fabrication:

- Synthesize PEGαMA from 8-arm PEG-OH and ethyl 2-(bromomethyl)acrylate.

- Fabricate soft hydrogels (~1-5 kPa) that replicate healthy tissue stiffness using photopolymerization.

2. Cell Seeding and Culture:

- Seed male and female human pulmonary arterial adventitial fibroblasts (hPAAFs) onto the soft hydrogels.

- Culture cells in media supplemented with defined sera (e.g., FBS, or human serum pooled by sex and age).

3. Dynamic Stiffening:

- After cell adhesion, perform a secondary photopolymerization reaction to stiffen the hydrogel to a modulus exceeding 10 kPa, mimicking diseased tissue.

4. Analysis of Fibroblast Activation:

- Quantify activation by measuring the expression and organization of alpha-smooth muscle action (αSMA) via immunostaining and image analysis.

- Compare activation levels between male and female cells on soft vs. stiffened substrates under different serum conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Host Factor Variability

| Reagent / Material | Function / Relevance | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| PEGαMA (Poly(ethylene glycol)-alpha methacrylate) | Forms dynamically stiffening hydrogels. | Allows in vitro mimicking of progressive tissue stiffening, as seen in fibrotic diseases [25]. |

| Human Serum (Sex & Age Pooled) | Physiologically relevant culture supplement. | Reveals sex-specific cell responses; superior to FBS which has undefined hormones [25] [23]. |

| Primary Cells (with defined sex) | Biologically relevant model system. | Using cells from both sexes is critical, as responses can be opposite [25] [24]. |

| RNA-Sequencing | Transcriptomic profiling tool. | Identifies genome-wide, sex- and age-specific host responses to biomaterials [23]. |

| Collagen & GelMA | Protein-based biomaterials. | Known to upregulate NKT cell pathways and activate adaptive immunity [26] [23]. |

| Chitosan & Alginate | Polysaccharide-based biomaterials. | Tend to induce stronger innate inflammatory responses [26] [23]. |

| Pyralomicin 1b | Pyralomicin 1b, MF:C20H19Cl2NO7, MW:456.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Methotrexate Hydrate | Methotrexate Hydrate, MF:C20H24N8O6, MW:472.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Table 2: Summary of Sex-Biased Immune Responses to Pathogens in Humans [24]

| Pathogen Type | Pathogen Example | Observed Sex Bias | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virus | Hepatitis B & C (HBV, HCV) | Higher prevalence & severity in males | [24] |

| Virus | Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV1/2) | Higher prevalence in females | [24] |

| Virus | HIV-1 | Female-biased transmission (Male-to-female) | Varies with regional socioeconomic factors [24] |

| Bacteria | Helicobacter pylori | Higher infection rate in males | [24] |

| Bacteria | Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme) | Initial infection higher in males; reinfection higher in females | [24] |

| Parasite | Leishmania spp. (Visceral) | Higher susceptibility in males | [24] |

| Fungus | Cryptococcus spp. | Higher disease incidence in males | Observed in both HIV+ and HIV- cohorts [24] |

Table 3: Age and Sex-Based Transcriptomic Responses to Biomaterials [23]

| Biomaterial Category | Example Materials | Key Immune Findings | Impact of Age & Sex |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polysaccharide-based | Chitosan, Alginate, Agarose, CMC | Induced strong innate immune responses. | Significant age-related differences were observed. |

| Protein-based | GelMA, Collagen Type I | Upregulated NKT cell pathway and adaptive immune responses. | Showed fewer differences by sex and age compared to polysaccharides. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Host Factor Impact Pathway

Diagram 2: Ex Vivo Blood Test Workflow

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Inherent Differentiation Biases

Problem: Unexpected lineage specification despite defined soluble factors.

- Potential Cause: The mechanical properties (stiffness) of your culture substrate are biasing stem cell fate.

- Solution: Match substrate stiffness to your target tissue. For example, use soft substrates (~0.2 kPa) to promote neurogenic or adipogenic outcomes, and stiffer substrates (10-100 kPa) to promote osteogenic outcomes [27]. Utilize polyacrylamide or polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) hydrogels with tunable elastic moduli for precise control.

- Potential Cause: The surface topography or geometry is providing conflicting cues.

- Solution: Employ microgrooved or nanogrooved substrates to guide cell alignment and fate. For enhanced osteogenic differentiation of human adipose stem cells (hASCs), consider using titanium dioxide (TiOâ‚‚) nanotubes with 70 nm grooves [28].

- Potential Cause: The cell adhesion ligand density is insufficient or inappropriate, failing to support necessary integrin signaling.

- Solution: Optimize the surface density of adhesion peptides like RGD. Ensure a sufficient density of GRGDSP to support cell adhesion and potentiate growth factor signaling [29].

Problem: Low efficiency of directed differentiation towards a target cell type.

- Potential Cause: The culture system does not support biologically driven assembly or proper morphogenesis.

- Solution: For tissues requiring complex 3D architecture, use 3D culture systems like embryoid bodies (EBs). Precisely control the size and shape of cell aggregates, as EB size critically influences lineage specification [29].

- Potential Cause: Lack of synergy between adhesive cues and soluble morphogenic cues.

- Solution: Co-present cell adhesion ligands (e.g., RGD) with specific growth factor receptor-binding peptides (e.g., BMP-receptor binding peptide) on your material surface to create synergistic signaling contexts [29].

Troubleshooting Epigenetic Memory

Problem: Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) exhibit a differentiation bias towards their cell type of origin.

- Potential Cause: Incomplete epigenetic reprogramming, leaving residual tissue-specific DNA methylation signatures [30].

- Solution:

- Serial Reprogramming: Differentiate the iPSCs and then reprogram them again.

- Chromatin-Modifying Drugs: Treat iPSCs with drugs like histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors or DNA methyltransferase inhibitors to reset the epigenetic landscape [30].

- Extended Culture: Culture iPSCs for extended passages (e.g., beyond passage 6) to allow for gradual erosion of the epigenetic memory.

- Solution:

Problem: Primary cells lose their phenotype after 2D expansion prior to 3D culture.

- Potential Cause: Cells have developed a "mechanical memory" of the stiff 2D culture substrate, which is maintained through epigenetic modifications like H3K9me3, locking them in a de-differentiated state [31].

- Solution:

- Limit Expansion: Keep 2D expansion phases as short as possible. For chondrocytes, recovery is possible after 8 population doublings but is lost after 16 [31].

- Epigenetic Disruption: Use inhibitors of epigenetic modifiers during or after expansion to disrupt the unfavorable mechanical memory. Suppressing or increasing H3K9me3 levels can help partially restore the native chromatin architecture [31].

- Use Soft Substrates: Culture cells on substrates that mimic the stiffness of their native tissue environment during expansion to prevent the acquisition of a non-physiological mechanical memory.

- Solution:

Problem: Unstable cell phenotype after transfer from a synthetic material to a 3D hydrogel.

- Potential Cause: The material-induced epigenetic state is not maintained in the new environment.

- Solution: Pre-condition cells on a material that promotes a transcriptionally active chromatin state (euchromatin) for the desired lineage. Cells cultured on micropatterned, flexible substrates show increased histone acetylation and decreased HDAC activity, which may prime them for differentiation [28] [27].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is "inherent differentiation bias" in the context of stem cell-material interactions? A1: Inherent differentiation bias refers to the tendency of stem cells to preferentially differentiate into certain lineages based on physical and chemical cues from the material they are cultured on, independent of soluble factors. This includes biases imposed by substrate stiffness, topography, and ligand presentation. For example, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) cultured on stiff substrates (100 kPa) produce a secretome that promotes their own proliferation, while those on soft substrates (0.2 kPa) produce a secretome that promotes osteogenesis and adipogenesis [32]. Similarly, iPSCs can retain an "epigenetic memory" of their tissue of origin, making them differentiate more efficiently into related lineages [30].

Q2: How do material cues lead to long-term epigenetic memory? A2: Material cues are transduced from the extracellular matrix, through the cytoskeleton, and directly to the nucleus via structures like the LINC complex. This force transmission can alter chromatin architecture by modifying histones (e.g., acetylation, methylation) and DNA methylation. These epigenetic marks can be maintained over multiple cell divisions, creating a memory of the initial mechanical environment. For instance, prolonged 2D culture on stiff plastic increases H3K9me3 levels, a repressive mark, which suppresses the native chondrocyte phenotype even after the cells are moved to a 3D soft hydrogel [27] [31].

Q3: My differentiation protocol is highly variable. Which material properties should I control first? A3: To reduce variability, prioritize standardizing these three material properties, as they are potent regulators of cell fate:

- Stiffness (Elastic Modulus): Use hydrogels to precisely mimic the stiffness of your target tissue.

- Topography: Introduce controlled micro- or nano-scale patterns to guide cell shape and differentiation.

- Ligand Density: Use well-defined chemistries to present a consistent density of cell adhesion peptides (e.g., RGD) across experimental batches.

Q4: Can I erase an undesirable mechanical memory in my cells? A4: Yes, emerging strategies involve using small molecule inhibitors targeting epigenetic enzymes like HDACs or histone methyltransferases/demethylases. Treating cells with these inhibitors can disrupt the established chromatin state, effectively "erasing" the mechanical memory and making cells more receptive to new differentiation cues [31] [30].

Q5: Why should I consider using 3D cultures over 2D systems? A5: 3D cultures more faithfully recapitulate the complex and dynamic signaling present during natural morphogenesis. They allow for "biologically driven assembly," where stem cells self-organize into higher-order structures with minimal external patterning cues. The 3D context also provides more physiologically relevant mechanical and spatial signals that can reduce aberrant epigenetic memory and improve differentiation efficiency [29] [33].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of Substrate Stiffness on MSC Paracrine Activity and Differentiation

| Substrate Stiffness | Secretome Effect on MSC Proliferation | Secretome Effect on MSC Differentiation | Effect on Macrophage Phagocytosis | Effect on Angiogenesis | Key Secretory Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.2 kPa (Soft) | No promotion | Promotes osteogenesis and adipogenesis | Most beneficial effects | Promotes | Elevated IL-6 [32] |

| 100 kPa (Stiff) | Boosts proliferation | No promotion | Less beneficial effects | Less beneficial | Elevated OPG, TIMP-2, MCP-1, sTNFR1 [32] |

Table 2: Epigenetic Modifications Induced by Material Cues

| Material Cue | Cell Type | Observed Epigenetic Change | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Micropatterned/ Flexible Substrates [28] [27] | Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | ↑ Histone H3 acetylation, ↓ HDAC activity | Increased gene transcription; Enhanced reprogramming and differentiation |

| TiO₂ Nanogrooves [28] | Human Adipose Stem Cells (hASCs) | ↑ H3K4 trimethylation, inhibition of demethylase RBP2 | Promotion of osteogenic differentiation |

| Prolonged 2D Culture (Stiff Substrate) [31] | Primary Chondrocytes | ↑ H3K9me3 (repressive mark) | Loss of chondrocyte phenotype; Mechanical memory |

| Nanotopographical Substrates [28] | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Altered DNA methylation in regions related to MSCs and osteogenic progenitors | Influence on early cell fate decisions |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Epigenetic Memory via Chondrocyte Re-differentiation

Purpose: To evaluate the persistence of mechanical memory after 2D expansion by measuring the recovery of the chondrocyte phenotype in a 3D hydrogel [31].

- 2D Expansion: Expand primary chondrocytes on standard tissue culture plastic (TCP) for a defined number of population doublings (PDs). For example, use 8 PDs (recoverable memory) and 16 PDs (long-term memory) as critical time points.

- 3D Encapsulation: Harvest the expanded cells and encapsulate them in a soft, chondropermissive 3D hydrogel (e.g., agarose or a soft PEG-based hydrogel at a stiffness of ~2-5 kPa).

- Culture: Maintain constructs in a defined chondrogenic medium (e.g., with TGF-β3) for 14-21 days.

- Analysis:

- Gene Expression: Quantify expression of chondrogenic genes (e.g., ACAN, COL2A1, SOX9) via qRT-PCR. Compare to freshly isolated chondrocytes and a no-expansion control.

- Histology: Process constructs for histology and stain for sulfated glycosaminoglycans (sGAG) with Alcian Blue or Safranin-O.

- Epigenetic Analysis: Perform immunostaining or ChIP-qPCR for H3K9me3 on the 2D-expanded cells and recovered 3D constructs to correlate phenotype with chromatin state.

Protocol 2: Testing Synergy between Adhesion and Growth Factor Cues

Purpose: To investigate the combined effect of cell adhesion ligand density and a tethered growth factor peptide on stem cell fate [29].

- Surface Functionalization: Prepare self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) or a similar platform with varying densities of the cell adhesion peptide GRGDSP (e.g., 0, low, medium, high density).

- Combinatorial Presentation: On each adhesion density background, co-present a fixed density of a specific growth factor receptor-binding peptide, such as a BMP-receptor binding peptide (BR-BP).

- Cell Seeding and Culture: Seed human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (hMSCs) onto the functionalized surfaces. Culture in a basal medium without exogenous BMP-2 to isolate the effect of the tethered cues.

- Analysis:

- Morphology: Quantify cell spreading and surface coverage after 24 hours.

- Differentiation: After 7-14 days, assess early osteogenic differentiation by staining for alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity and quantifying expression of osteogenic genes (e.g., Runx2, Osteocalcin).

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: Mechano-Epigenetic Signaling Pathway

Diagram Title: Material Cues to Epigenetic Change Pathway

Diagram 2: Mechanical Memory Experiment Workflow

Diagram Title: Mechanical Memory Testing Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Studying Stem Cell-Material Interactions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Property | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Polyacrylamide Hydrogels [32] [27] | Tunable elastic modulus (0.1 kPa to 100+ kPa); can be functionalized with adhesion ligands. | Studying the effect of substrate stiffness on stem cell differentiation and paracrine activity. |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) [28] | Flexible polymer; can be molded with microgrooves; gas-permeable. | Creating micropatterned substrates to study effects of topography and strain on histone acetylation. |

| RGD Peptide [29] | Synthetic peptide containing Arg-Gly-Asp sequence; binds to cell surface integrins. | Functionalizing synthetic materials to enable specific cell adhesion and study integrin-mediated signaling. |

| Titanium Dioxide (TiOâ‚‚) Nanotubes [28] | Nanoscale topography (e.g., 70 nm grooves); bioactive. | Promoting osteogenic differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells (hASCs). |

| Thermoresponsive Hydrogels (e.g., Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)) [28] | Allows for gentle cell harvest by lowering temperature without enzymatic digestion. | Harvesting cells while preserving their epigenetic state and mechanical memory for downstream analysis. |

| Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) Inhibitors (e.g., Valproic Acid, Trichostatin A) [30] | Small molecules that increase global histone acetylation by inhibiting deacetylases. | Resetting epigenetic memory in iPSCs or disrupting unfavorable mechanical memory. |

| Rhodirubin B | Rhodirubin B, MF:C42H55NO15, MW:813.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pgla tfa | Pgla tfa, MF:C90H163F3N26O24S, MW:2082.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Engineering Solutions: From 'Bottom-Up' Design to Integrin-Targeting and AI

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What exactly is the "bottom-up" biomaterial design paradigm, and how does it differ from traditional approaches?

The bottom-up biomaterial design paradigm is a strategic framework that starts by first understanding the fundamental biological properties and microenvironmental needs of specific cells, and then engineering cell-instructive biomaterials from the molecular level upward to support them [34]. This approach fundamentally shifts away from conventional methods that often try to adapt cells to pre-existing, off-the-shelf materials. Instead, it prioritizes designing biomaterials that are tailored to address key biological challenges such as differentiation variability, functional maturity of derived cells, and the survival of therapeutic cell populations in hostile microenvironments [34]. By replicating lineage-specific mechanical, chemical, and spatial cues, these tailored biomaterials enhance differentiation fidelity, reprogramming efficiency, and functional integration.

Q2: My biomaterial implant is triggering a strong foreign body response and fibrosis. How can a bottom-up approach help mitigate this?

A bottom-up approach addresses this by actively designing materials to modulate the immune response, rather than just being passive scaffolds. This involves several key strategies informed by the principles of the paradigm [35] [36]:

- Immune-Instructive Surfaces: Modifying surface properties like roughness, topography, and chemistry can significantly influence immune cell interactions. For example, specific nanopatterning can reduce the foreign body reaction and improve integration [36].

- Controlled Release of Immunomodulators: Biomaterials can be engineered to release bioactive molecules that actively shape the immune environment. For instance, releasing agents that promote a shift in macrophage phenotype from pro-inflammatory (M1) to anti-inflammatory and pro-regenerative (M2) can reduce chronic inflammation and fibrosis [35].

- Mechanical Property Matching: The stiffness and elasticity of the biomaterial should match the target tissue. Softer materials that mimic the brain's mechanical properties, for example, have been shown to lead to a reduced inflammatory reaction [36].

Q3: I am working with induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). How can this paradigm help with issues like inconsistent differentiation and tumorigenic risk?

The bottom-up paradigm directly tackles these challenges by creating engineered microenvironments that provide precise control over stem cell fate [34] [37].

- Overcoming Epigenetic Memory: iPSCs can retain a "memory" of their original cell type, which can bias differentiation. A bottom-up design uses tailored biomaterial cues—such as specific adhesion ligands, controlled stiffness, and spatial patterning—to more robustly guide cells toward the desired lineage, overcoming this inherent bias [34].

- Ensuring Functional Maturity and Safety: By replicating critical aspects of the native stem cell niche, these biomaterials promote more complete differentiation and functional maturation of derived cells. This reduces the risk of residual undifferentiated pluripotent cells persisting and forming teratomas [34]. Using defined, biomaterial-based systems also avoids the variability and xenogeneic risks associated with tumor-derived matrices like Matrigel [33].

Q4: What are some key material properties I should prioritize when designing a bottom-up biomaterial for neural regeneration?

For neural applications, the biomaterial should mimic the delicate and complex environment of the nervous system. Key properties to prioritize include [37]:

- Electrical Conductivity: Using conductive polymers like polypyrrole, polythiophene, and polyaniline can help neurites grow and enhance cellular activity by facilitating the transmission of electrical impulses crucial for nerve signaling.

- Mechanical Compatibility: Neural tissue is soft. The scaffold should be malleable, flexible, and structurally sound to match the mechanical properties of the brain without causing compression or irritation.

- Biocompatibility and Surface Erodibility: Materials like polyglycerol sebacate (PGS) are beneficial because they are surface-erodible and elastomeric, providing consistent contact-guidance for nerve regeneration over time.

- Support for 3D Growth: The material should facilitate the creation of a porous, three-dimensional structure that supports axonal ingrowth and cell infiltration.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inconsistent Cell Differentiation Outcomes in 3D Biomaterial Scaffolds

A core promise of the bottom-up paradigm is controlling cell fate, but variability in differentiation can still occur.

Step 1: Identify the Problem Confirm that differentiation is inconsistent across multiple batches of scaffolds and with different cell donors, not just a one-time experimental error.

Step 2: List Possible Explanations

- Inhomogeneous Scaffold Properties: Variability in porosity, stiffness, or ligand distribution within the scaffold.

- Improper Biochemical Cue Presentation: Inconsistent concentration, stability, or spatial distribution of growth factors or adhesion peptides.

- Inadequate Mass Transport: Poor diffusion of nutrients, oxygen, or signaling molecules to cells in the scaffold's core.

- Cell-Seeding Inconsistency: Uneven cell distribution or varying initial cell viability.

Step 3: Collect Data & Experimentation

- For Explanation 1: Characterize scaffold uniformity using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to assess pore structure and use atomic force microscopy (AFM) to map mechanical properties across different regions of the scaffold.

- For Explanation 2: Use immunofluorescence to check the spatial distribution of key biofunctionalized ligands (e.g., RGD peptides). Employ ELISA assays to quantify the release kinetics of loaded growth factors from multiple scaffold batches.

- For Explanation 3: Section the scaffold and perform live/dead staining to see if cell death is localized to the interior, indicating diffusion limitations.

Step 4: Implement the Fix Based on the data, potential fixes include:

- Optimizing fabrication parameters (e.g., electrospinning, 3D bioprinting) for greater consistency.

- Using dual-crosslinking or different biofunctionalization strategies to ensure uniform and stable cue presentation.

- Incorporating sacrificial materials or channels during fabrication to create vascular-like networks for improved perfusion.

Problem 2: Uncontrolled or Mismatched Biomaterial Degradation

The degradation profile of a biomaterial is critical for its success and must match the rate of new tissue formation.

Step 1: Identify the Problem Observe either a complete loss of structural integrity too early, a persistent implant that hinders tissue remodeling, or an inflammatory reaction to degradation products.

Step 2: List Possible Explanations

- Bulk Erosion vs. Surface Erosion: Bulk-eroding polymers (e.g., PLGA) can lead to sudden collapse and acidic byproduct accumulation, while surface erosion offers more controlled degradation.

- Enzyme-Mediated Degradation: Overexpression of specific enzymes (e.g., MMPs) at the implant site can cause unexpectedly rapid degradation.

- Material Crystallinity and MW: Higher crystallinity and molecular weight generally slow down degradation.

Step 3: Collect Data & Experimentation

- Perform in vitro degradation studies in PBS and in enzyme solutions (e.g., collagenase for natural polymers) to track mass loss, molecular weight change, and pH shift over time.

- Analyze the mechanical properties (e.g., compressive modulus) of the scaffold weekly to correlate degradation with function loss.

Step 4: Implement the Fix

- Switch to a surface-eroding polymer (e.g., polyanhydrides) or blend polymers to fine-tune the degradation profile.

- Design the material to be enzyme-responsive, so degradation is directly linked to cell-mediated remodeling activities [35]. For example, incorporate MMP-cleavable crosslinkers.

- Adjust the crystallinity and initial molecular weight during polymer synthesis.

Key Biomaterial Properties and Their Design Considerations

Table 1: Key properties for bottom-up biomaterial design and their impact on biological response.

| Property | Goal in Bottom-Up Design | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Stiffness | Match target tissue to direct stem cell lineage and reduce foreign body response [8] [36]. | Tune polymer crosslinking density, polymer concentration, or composite with ceramics. Softer materials (~0.1-1 kPa) for brain, stiffer (~10-30 kPa) for bone. |

| Biodegradation Rate | Synchronize with new tissue formation rate to provide temporary, supportive niche. | Choose between surface-eroding (e.g., PGS [37]) or bulk-eroding (e.g., PLGA) polymers. Incorporate enzyme-sensitive linkages. |

| Bioactivity | Present specific biochemical cues to instruct cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation. | Functionalize with adhesion peptides (e.g., RGD [8]), incorporate glycosaminoglycan mimetics, or create systems for controlled release of growth factors. |

| Immunomodulation | Actively shape a pro-regenerative immune microenvironment [35] [36]. | Modify surface topography/chemistry; incorporate controlled release of cytokines (e.g., IL-4) or drugs to promote M2 macrophage polarization. |

| Electrical Conductivity | Support excitable tissues like nerve and muscle by facilitating electrical signal propagation [37]. | Use conductive polymers (e.g., polypyrrole), or incorporate graphene/carbon nanotubes into insulating biodegradable polymers. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 1: Assessing Integrin-Mediated Signaling in Cells on Engineered Surfaces

Purpose: To verify that your biomaterial is successfully engaging specific integrin receptors to activate pro-regenerative intracellular signaling pathways, a core principle of bottom-up design [8].

Materials:

- Biomaterial scaffold or 2D film

- Relevant cell type (e.g., mesenchymal stem cells, fibroblasts)

- Antibodies for immunofluorescence: anti-integrin (e.g., β1 subunit), anti-phospho-FAK (Tyr397), anti-vinculin, and corresponding fluorescent secondary antibodies

- Cell culture reagents

- Confocal microscope

Method:

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells at a sub-confluent density onto the biomaterial test substrate and a control substrate (e.g., tissue culture plastic).

- Fixation and Permeabilization: After 4-24 hours, rinse cells with PBS and fix with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes. Permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 minutes.

- Immunostaining: Block with 1% BSA for 1 hour. Incubate with primary antibodies (diluted in blocking buffer) overnight at 4°C. Wash and incubate with secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. Use phalloidin to stain F-actin and DAPI for nuclei.

- Imaging and Analysis: Image using a confocal microscope. Analyze for:

- Focal Adhesion Formation: Look for co-localization of vinculin and phospho-FAK with the ends of F-actin stress fibers.

- Integrin Clustering: Assess the presence and size of integrin clusters at the cell-material interface.

- Signal Activation: Compare the intensity and distribution of phospho-FAK staining between test and control materials, indicating activation of downstream signaling.

Protocol 2: Quantifying Macrophage Polarization in Response to an Immunomodulatory Biomaterial

Purpose: To determine if your biomaterial can actively modulate the host immune response by driving macrophages toward a pro-regenerative (M2) phenotype, a key strategy for overcoming variability in host responses [35] [36].

Materials:

- Biomaterial sample (sterile)

- Primary human or murine macrophages (e.g., THP-1-derived macrophages)

- Cell culture media

- LPS (for M1 polarization control), IL-4 (for M2 polarization control)

- RNA extraction kit, qPCR reagents

- Antibodies for flow cytometry: anti-CD86 (M1 marker), anti-CD206 (M2 marker)

Method:

- Macrophage Culture and Stimulation: Differentiate and seed macrophages onto the biomaterial and control surfaces. Include control groups stimulated with LPS (M1) and IL-4 (M2).

- Gene Expression Analysis (qPCR): After 24-48 hours, extract total RNA. Perform qPCR to analyze the expression of:

- M1 markers: TNF-α, iNOS (NOS2), IL-1β

- M2 markers: ARG1, CD206 (MRC1), IL-10

- Normalize to housekeeping genes (e.g., GAPDH). A shift toward M2 marker expression on the test biomaterial indicates successful immunomodulation.

- Surface Marker Analysis (Flow Cytometry): Harvest cells from the biomaterial surface (using gentle scraping or enzymatic digestion). Stain cells with fluorescently-labeled antibodies against CD86 and CD206. Analyze using flow cytometry to quantify the percentage of cells in M1 vs. M2 states.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key reagents and materials for bottom-up biomaterial research.

| Item | Function in Bottom-Up Design | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| RGD Peptide | A key integrin-binding peptide used to biofunctionalize materials and promote specific cell adhesion [8]. | Enhancing osteogenic differentiation on bone scaffolds; improving endothelial cell attachment on vascular grafts. |

| Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP)-Cleavable Peptide Crosslinker | Creates enzyme-responsive materials that degrade in response to cell-secreted enzymes, facilitating cell migration and tissue remodeling [35]. | Designing injectable hydrogels for 3D cell culture; creating scaffolds that allow patient-specific invasion rates. |

| Conductive Polymers (e.g., Polypyrrole) | Provides electrical conductivity to biomaterials, supporting the function of electrically excitable tissues [37]. | Nerve guidance conduits; cardiac patches for myocardial infarction. |

| Hyaluronic Acid (HA) | A natural glycosaminoglycan that can be chemically modified to create hydrogels that mimic the native extracellular matrix. | Liver organoid culture [33]; wound healing dressings. |

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | A synthetic, biodegradable polymer known for its good mechanical properties and slow degradation rate. Often used in composites. | Electrospun scaffolds for bone and neural tissue engineering [37]. |

| Endophenazine C | Endophenazine C, MF:C25H28N2O7, MW:468.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Yadanzioside L | Yadanzioside L, MF:C34H46O17, MW:726.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Key Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Integrin Signaling Pathway

Troubleshooting Workflow

Harnessing Integrin-Targeting Motifs to Direct Cell Fate and Enhance Integration

Integrins, a superfamily of heterodimeric transmembrane adhesion receptors, serve as fundamental mediators of bidirectional communication between cells and their extracellular matrix (ECM). These receptors, composed of α and β subunits that form 24 unique combinations in humans, recognize specific ECM components and orchestrate essential cellular processes including adhesion, migration, proliferation, differentiation, and survival [38] [39] [40]. The dynamic interplay between integrins and their ligands forms the molecular foundation for tissue development, homeostasis, and regeneration, establishing them as prime targets for therapeutic intervention in regenerative medicine [8] [40].

The central premise of harnessing integrin-targeting motifs lies in their ability to precisely direct cell fate and enhance biomaterial integration by recapitulating key aspects of native ECM signaling. Specific recognition motifs, particularly the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) sequence found in numerous ECM proteins, demonstrate high binding affinity for several integrins, including αvβ3, αvβ5, αvβ6, αvβ8, and α5β1 [39] [41]. This specific binding capability provides a powerful tool for engineering biomaterials that can actively instruct cellular behavior rather than merely serving as passive scaffolds [8].

Within the context of overcoming variability in biomaterial host responses, integrin-targeting strategies offer promising approaches to enhance signaling specificity and reduce unpredictable outcomes. By precisely controlling integrin engagement through engineered motifs, researchers can potentially direct more consistent cellular responses, improve biomaterial integration, and ultimately achieve more predictable therapeutic outcomes in regenerative medicine applications [8] [40].

Technical Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Biomaterial-Cell Interaction Issues

Problem: Poor cell adhesion to engineered biomaterials Solution: Optimize integrin-binding motif presentation

- Verify motif density: Use quantitative methods (e.g., ELISA, fluorescence tagging) to confirm RGD surface concentration. Optimal density typically ranges from 1-10 fmol/cm² but requires empirical determination for specific cell types [8] [41].

- Check spatial arrangement: Ensure motifs are accessible, not sterically hindered by polymer chains. Incorporate flexible linkers (e.g., PEG spacers) of appropriate length (typically 3.5-13 nm) to enhance accessibility [8].

- Confirm motif orientation: Use chemoselective conjugation strategies (e.g., click chemistry, maleimide-thiol) rather than random conjugation to control ligand orientation [8].

- Validate integrin specificity: Include control surfaces with scrambled peptide sequences (e.g., RGE) to distinguish specific integrin-mediated adhesion from non-specific binding [39].

Problem: Inconsistent differentiation outcomes across experimental replicates Solution: Standardize integrin signaling pathway activation

- Characterize integrin expression profile: Perform flow cytometry to identify which integrin subunits (αv, β1, β3, β5, etc.) your target cell population expresses before designing biomaterials [38] [40].

- Control substrate mechanics: Match biomaterial stiffness to target tissue physiology (e.g., ~0.1-1 kPa for neural tissue, ~10-30 kPa for mesenchymal precursors, ~25-40 kPa for osteogenic differentiation) [8] [40].

- Modulate co-receptor engagement: Incorporate secondary binding sites (e.g., PHSRN synergic site for α5β1 integrin) alongside primary RGD motifs to enhance signaling specificity [8].

- Monitor pathway activation: Implement standard controls for key downstream effectors (FAK, ERK, AKT) via Western blot to verify consistent integrin signaling across experiments [42] [8].

Biomaterial Performance Challenges

Problem: Unpredictable host immune response to implanted biomaterials Solution: Engineer immunomodulatory integrin engagement

- Select anti-inflammatory integrin ligands: Prioritize motifs that promote M2 macrophage polarization (e.g., laminin-derived peptides engaging α6β1) over those stimulating pro-inflammatory responses [1].

- Control degradation kinetics: Tune biomaterial degradation rates to match tissue ingrowth (days for acute inflammation resolution, weeks for functional integration) to prevent persistent foreign body response [8].

- Incorporate multi-functional motifs: Include integrin-binding sequences known to modulate immune cell activity (e.g., α4β1-binding peptides for lymphocyte regulation) alongside adhesion motifs [40].

- Validate in relevant models: Test materials in systems with competent immune components (e.g., co-cultures with macrophages) rather than solely in simplified cell systems [1].

Problem: Limited functional integration with host tissue Solution: Enhance bidirectional mechanotransduction

- Design dynamic mechanical properties: Develop materials with stress-relaxing behavior that permit cell-mediated remodeling rather than purely elastic substrates [8].

- Incorporate protease-sensitive domains: Include matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-cleavable sequences to enable cell-directed material degradation and replacement with native ECM [8].

- Implement graded interface design: Create biomaterials with spatially varying integrin ligand density to guide seamless tissue integration at the implant-host interface [8] [40].

- Ensure vascularization support: Include αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrin-binding motifs to promote endothelial cell adhesion and angiogenic signaling for proper nutrient transport [39].

Integrin Signaling Pathways: Mechanisms and Experimental Monitoring

Core Integrin Signaling Cascade

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental signaling pathway activated upon integrin engagement with ECM motifs, highlighting key nodes for experimental monitoring:

Lineage-Specific Integrin Signaling

The diagram below illustrates how integrin signaling directs mesenchymal stem cell fate toward adipogenic, chondrogenic, and osteogenic lineages through distinct pathway activation:

Quantitative Analysis of Integrin Signaling Components

Table 1: Key downstream effectors in integrin-mediated differentiation pathways

| Signaling Component | Adipogenesis | Chondrogenesis | Osteogenesis | Detection Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAK phosphorylation | Decreased at Tyr397 | Variable | Increased at Tyr397 | Phospho-specific Western blot |

| ERK/MAPK activity | Moderate activation | Strong activation (via Src) | Strong activation | Phospho-ERK ELISA/Western |

| Wnt/β-catenin | Activated (inhibits differentiation) | Not primary pathway | Activated (promotes differentiation) | β-catenin nuclear localization |

| Key transcription factors | PPARγ, CEBPα | SOX9 | RUNX2, OSX | Immunofluorescence, qPCR |

| Characteristic markers | AP2, AdipoQ | Collagen II, Aggrecan | Osteocalcin, Alkaline phosphatase | qPCR, enzymatic assay |

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Integrin Research

Table 2: Key research reagents for manipulating and monitoring integrin signaling

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrin-binding peptides | RGD, LDV, PHSRN, IKVAV | Promote specific integrin engagement | Optimize density (1-10 fmol/cm²); include spacer arms |