PCR and Electrophoresis: Essential Tools for Analyzing Cellular Response to Biomaterials

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers on applying Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and electrophoresis to evaluate cellular responses to biomaterials.

PCR and Electrophoresis: Essential Tools for Analyzing Cellular Response to Biomaterials

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers on applying Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and electrophoresis to evaluate cellular responses to biomaterials. It covers the foundational principles of how biomaterials interact with biological systems and why molecular-level analysis is crucial for assessing biocompatibility, inflammation, and tissue regeneration. The content details standardized methodologies for nucleic acid isolation, PCR amplification, and product analysis, alongside direct protocols for preparing biomaterial extracts and culturing cells. A significant focus is given to troubleshooting common PCR challenges and optimizing protocols for complex biomaterial samples. Finally, the article explores advanced validation techniques, including the use of digital PCR for absolute quantification and integrity assays, ensuring data reliability for preclinical and clinical applications in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Understanding Biomaterial-Cell Interactions: The Role of Molecular Biology

The concept of biocompatibility has evolved significantly from its early definitions focused primarily on biological safety. The contemporary understanding, encapsulated in the Williams definition, describes it as "the ability of a material to perform with an appropriate host response in a specific application" [1] [2]. This definition underscores that biocompatibility is not merely about the absence of harm but involves a dynamic interaction between the biomaterial and the host environment, optimized for the clinical function of the medical device or tissue engineering construct [1].

In the context of tissue engineering, this definition expands further to emphasize the scaffold's role in supporting appropriate cellular activity, including the facilitation of molecular and mechanical signaling systems to optimize tissue regeneration [1]. This progression from bio-inertia to biofunctionality represents a paradigm shift in biomaterial science, moving from materials that passively coexist with tissues to those that actively direct a desired biological response [3]. Evaluating these complex interactions requires sophisticated molecular tools, with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and electrophoresis forming cornerstone technologies for quantifying cellular responses at the genetic level.

Core Principles and Definitions

Biocompatibility encompasses a spectrum of requirements that vary significantly based on the medical application. The core principle is that a biomaterial must not only be non-toxic but must also perform its intended function effectively within the biological environment.

Application-Specific Definitions

- Long-Term Implantable Devices: The ability of the device to perform its intended function with the desired degree of incorporation in the host, without eliciting any undesirable local or systemic effects [2].

- Tissue-Engineering Products: The ability to perform as a substrate that supports appropriate cellular activity, including molecular and mechanical signaling systems, to optimize tissue regeneration [1] [2].

Key Determinants of Biocompatibility

The biological response to a biomaterial is influenced by multiple factors that extend beyond its chemical composition [1]:

- Material Chemical Properties: Composition, surface chemistry, and degradation products.

- Physical Characteristics: Stiffness, topography, and mechanical properties.

- Host-Related Factors: Implantation site, tissue vascularization, and patient health status.

- Material Response: The effect of the biological system on the material, including degradation and structural changes.

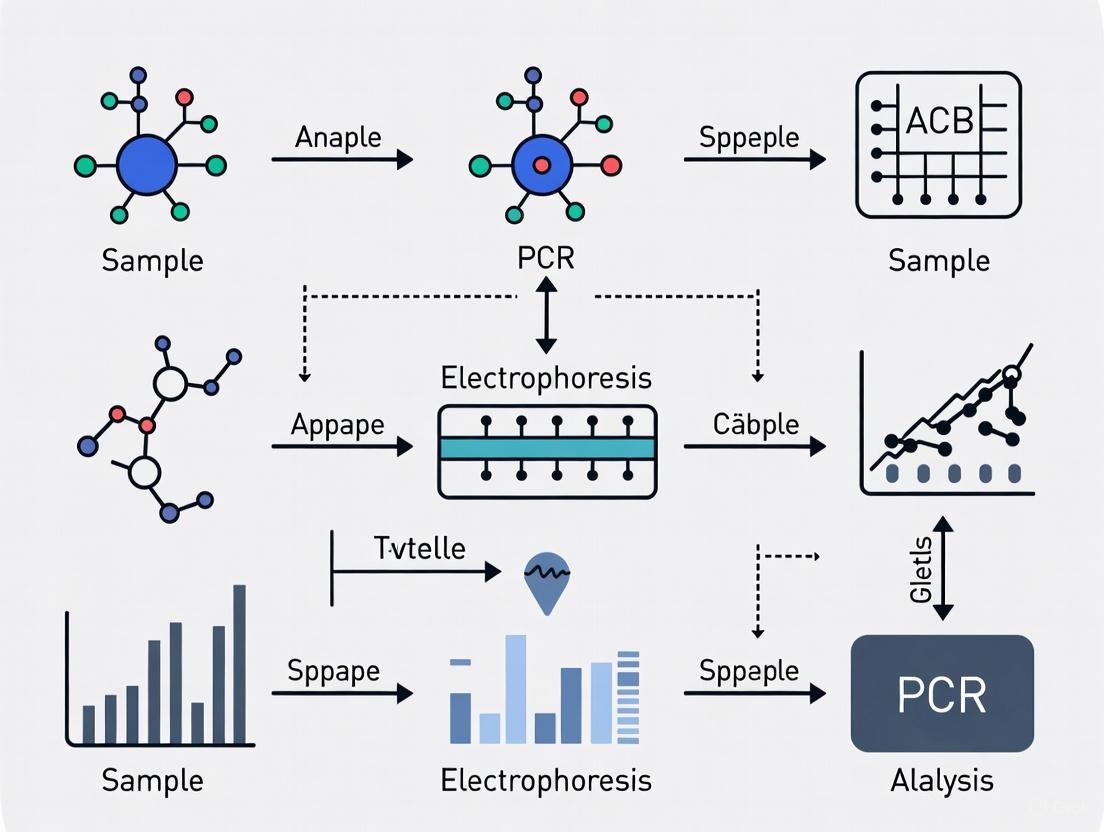

The following diagram illustrates the multifaceted nature of the host response to biomaterials and the key pathways researchers can investigate using molecular tools like PCR:

Quantitative Biocompatibility Assessment

While traditional histological evaluation provides valuable qualitative data, recent advances emphasize the importance of quantitative metrics for objective biocompatibility assessment. These methods enable more precise comparison between different scaffold compositions and architectures [4].

Geometric Analysis of Encapsulation

A study investigating freeze-cast polymeric scaffolds for tissue regeneration introduced geometric models to quantify the foreign body response [4]. Key measurable parameters include:

Table 1: Quantitative Metrics for Scaffold Biocompatibility Assessment

| Parameter | Measurement Technique | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Encapsulation Thickness | Histomorphometric analysis of cross-sections | Indicator of fibrotic response; thinner encapsulation suggests better integration |

| Cross-sectional Area | Digital imaging of explanted scaffolds | Measures structural stability and deformation in vivo |

| Ovalization | Ratio of minor to major axis dimensions | Quantifies structural deformation under physiological loads |

| Cell Infiltration Distance | Microscopic measurement of cell migration into scaffold | Indicates scaffold porosity and bioactivity |

This quantitative approach demonstrated that EDC-NHS-crosslinked bovine collagen scaffolds exhibited superior biocompatibility with minimal encapsulation compared to other materials, highlighting how material composition directly influences the host response [4].

Molecular Analysis of Cellular Response

PCR-based methods provide crucial quantitative data on gene expression patterns in cells interacting with biomaterials:

Table 2: Key Apoptosis Markers for Biocompatibility Assessment

| Gene/Protein | Function | Detection Method | Significance in Biocompatibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bax | Pro-apoptotic protein | RT-qPCR, Western blot | Elevated expression indicates activation of apoptotic pathways |

| Bcl-2 | Anti-apoptotic protein | RT-qPCR, Western blot | Higher expression suggests cell survival and material compatibility |

| Caspase-3 | Apoptosis executioner | RT-qPCR, Western blot | Activated form indicates ongoing apoptosis |

| Bax/Bcl-2 Ratio | Apoptosis regulation balance | Calculated from expression data | Predictive metric for overall cellular health |

A recent study evaluating dental polymers demonstrated that CAD/CAM PMMA materials showed more stable apoptotic marker expression over 28 days compared to conventional polymers, indicating superior temporal biocompatibility [5].

Experimental Protocols

RNA Extraction and Quality Control

Purpose: To isolate high-quality RNA from cells or tissues exposed to biomaterials for subsequent gene expression analysis [5].

Materials:

- RNAiso Plus lysis buffer or equivalent

- Chloroform

- Isopropyl alcohol

- 75% ethanol (in DEPC-treated water)

- Nuclease-free water

- Tissue homogenizer

Procedure:

- Tissue Homogenization: Place 50-100 mg of tissue in 1 mL of RNAiso Plus buffer. Homogenize using a low-temperature high-speed grinder at 5.5 m/s for 3 cycles of 1 minute each at 4°C [5].

- Phase Separation: Incubate homogenate for 5 minutes at room temperature. Add 0.2 mL chloroform, shake vigorously for 15 seconds, and incubate for 3 minutes. Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C.

- RNA Precipitation: Transfer aqueous phase to new tube. Add 0.5 mL isopropyl alcohol, mix, and incubate for 10 minutes. Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C.

- RNA Wash: Remove supernatant. Wash pellet with 1 mL 75% ethanol. Centrifuge at 7,500 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C.

- RNA Dissolution: Air-dry pellet for 5-10 minutes. Dissolve RNA in nuclease-free water.

- Quality Control: Measure RNA concentration and purity using spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratio of 1.8-2.0 indicates pure RNA).

Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Purpose: To quantify expression of specific genes involved in the cellular response to biomaterials [5].

Materials:

- PrimeScript RT reagent kit [5]

- TB Green Premix Ex Taq [5]

- Gene-specific primers (e.g., for Bax, Bcl-2, Caspase-3, GAPDH)

- Thermal cycler with real-time detection capability

- Nuclease-free PCR tubes

Procedure:

- Reverse Transcription:

- Prepare reaction mix: 1 μg total RNA, 1 μL PrimeScript RT Enzyme Mix, 1 μL RT Primer Mix, 4 μL 5× PrimeScript Buffer, nuclease-free water to 20 μL.

- Incubate: 37°C for 15 minutes, 85°C for 5 seconds [5].

- Store cDNA at -20°C.

qPCR Amplification:

- Prepare reaction mix: 10 μL TB Green Premix Ex Taq, 0.8 μL forward primer (10 μM), 0.8 μL reverse primer (10 μM), 2 μL cDNA template, 6.4 μL nuclease-free water [5].

- Cycling conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds

- 40 cycles: 95°C for 5 seconds, 60°C for 30 seconds

- Melt curve: 95°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 1 minute, 95°C for 15 seconds

Data Analysis:

- Calculate quantification cycle (Cq) values

- Determine relative expression using the 2^(-ΔΔCq) method [5]

- Normalize to housekeeping gene (e.g., GAPDH)

The following workflow diagram outlines the complete process from sample preparation to data analysis in biomaterial biocompatibility assessment:

Agarose Gel Electrophoresis for PCR Product Analysis

Purpose: To separate and visualize amplified DNA fragments to confirm specificity of PCR reactions [6] [7].

Materials:

- Agarose

- TAE or TBE electrophoresis buffer

- DNA ladder (molecular weight standard)

- Ethidium bromide or SYBR Safe stain

- Gel electrophoresis apparatus

- UV transilluminator or gel documentation system

Procedure:

- Gel Preparation: Melt 1-2% agarose in electrophoresis buffer. Cool to approximately 60°C, add nucleic acid stain (0.5 μg/mL ethidium bromide), and pour into casting tray with comb [6].

- Sample Loading: Mix PCR products with 6× loading dye. Load samples alongside DNA ladder in separate wells.

- Electrophoresis: Run gel at 5-10 V/cm until adequate separation achieved (approximately 30-45 minutes) [6].

- Visualization: Examine gel under UV light and document results.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Biomaterial Cellular Response Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Reverse Transcriptase Enzymes | PrimeScript Reverse Transcriptase | Converts RNA to cDNA for gene expression analysis [5] |

| DNA Polymerases | Taq DNA Polymerase, TB Green Premix | Amplifies specific DNA sequences with thermostability [6] [7] |

| Nucleic Acid Isolation Kits | RNAiso Plus | Extracts high-quality RNA from tissue samples [5] |

| Fluorescent Detection Reagents | TB Green, SYBR Green, Ethidium Bromide | Enables detection and quantification of amplified DNA [7] |

| Apoptosis Assay Kits | TUNEL Assay Kit | Detects programmed cell death in tissue sections [5] |

| Histological Stains | Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) | Visualizes tissue morphology and cellular structure [5] |

| Scaffold Materials | EDC-NHS-crosslinked collagen, PCL, PEEK | Provides three-dimensional substrates for tissue integration studies [4] [8] [5] |

| Ethylnorepinephrine Hydrochloride | Ethylnorepinephrine Hydrochloride, CAS:3198-07-0, MF:C10H16ClNO3, MW:233.69 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Gusperimus Trihydrochloride | Gusperimus Trihydrochloride, CAS:85468-01-5, MF:C17H40Cl3N7O3, MW:496.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Research Applications

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing in Biomaterial Evaluation

The application of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) has revolutionized our understanding of cellular responses to biomaterials by enabling unprecedented resolution of cell-type-specific responses [8]. This technology has revealed previously unknown diversity in immune and stromal cell populations responding to implanted materials.

A comprehensive atlas of the biomaterial tissue microenvironment created through scRNAseq identified 18 distinct cell clusters responding to biological and synthetic scaffolds, including multiple subsets of fibroblasts, natural killer (NK) cells, and specialized macrophage populations with unique functional signatures [8]. This granular understanding moves beyond bulk tissue analysis to reveal intricate cell-cell communication networks that determine clinical outcomes.

Computational Analysis of Cellular Signaling

The development of computational tools like Domino enables reconstruction of intracellular signaling networks based on transcription factor activation from scRNAseq data [8]. This approach identifies condition-specific intercellular signaling patterns connected to downstream biological functions, providing insights into:

- Immune-stromal interactions in the cellular response to biomaterials

- Signaling modules for stromal, immune, and tissue-specific cells

- Material-specific communication patterns that drive regeneration versus fibrosis

These computational approaches validated novel signaling pathways, such as IL-17 signaling in the foreign body response, confirmed through Il17ra−/− knockout models [8].

The evolution of biocompatibility from a concept focused primarily on safety to one emphasizing biofunctionality represents significant progress in biomaterial science. The integration of molecular biology techniques like PCR and electrophoresis with traditional histological methods provides researchers with powerful tools to quantify and understand host responses at unprecedented resolution. The quantitative frameworks and standardized protocols outlined in these application notes empower researchers to conduct comprehensive biocompatibility assessments that bridge the gap between basic material characterization and clinical performance. As single-cell technologies and computational analysis continue to advance, our ability to precisely tailor biomaterial design to specific clinical applications will further transform the field of regenerative medicine.

The study of inflammation and tissue regeneration is pivotal for developing new therapeutic strategies for a wide range of conditions, including osteoarthritis, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), and impaired wound healing. Understanding the key molecular players—both genetic and protein-based—provides critical insights into disease mechanisms and enables the development of targeted interventions. This field has been revolutionized by advanced molecular biology techniques that allow for precise detection, quantification, and analysis of these targets.

Molecular targets can be broadly categorized into genetic elements (specific genes, single-nucleotide polymorphisms, and expression profiles) and proteins that execute cellular functions. The integration of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and electrophoresis methodologies provides a powerful framework for investigating these targets within the context of biomaterial research, where understanding cellular responses to implanted materials is essential for evaluating biocompatibility and regenerative potential.

Key Genetic and Protein Targets

Recent research has identified specific molecular targets crucial for regulating inflammatory processes and regenerative pathways. The tables below summarize key validated targets.

Table 1: Key Genetic Targets in Inflammation and Regeneration

| Target Name | Full Name/Type | Primary Biological Function | Associated Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| WSTF | Williams Syndrome Transcription Factor | Represses pro-inflammatory gene loci in the nucleus; evicted during chronic inflammation [9] [10]. | Chronic Inflammation, Osteoarthritis, MASH, Aging [9] [10]. |

| GWAS-Derived Loci | 513 novel genetic markers from meta-analysis | 962 genetic markers identified; 700 genes with high confidence linked to disease pathogenesis [11]. | Osteoarthritis [11]. |

| Reference Genes | Housekeeping Genes (e.g., EF1α, Act, UBI, GAPDH) | Constitutively expressed genes used for normalization in gene expression studies [12] [13]. | Used as stable controls across various tissues and experimental conditions [12]. |

Table 2: Key Protein Targets and Analytical Methods

| Target/Method | Description | Role in Inflammation/Regeneration | Primary Detection Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| WSTF Protein | Nuclear protein degraded via autophagy in chronic inflammation [9] [10]. | Loss leads to persistent activation of pro-inflammatory genes; restoration suppresses inflammation [9] [10]. | Western Blot, Immunostaining [14]. |

| SDS-PAGE | Denaturing electrophoresis separating proteins by molecular mass [14]. | Analyzes protein expression, purity, and molecular weight in cell-biomaterial interactions [14]. | Protein separation and quantification [14]. |

| Native-PAGE | Non-denaturing electrophoresis separating proteins by charge, size, and shape [14]. | Studies native protein complexes, quaternary structure, and enzymatic activity [14]. | Analysis of native protein complexes [14]. |

| 2D-PAGE | Separates proteins by isoelectric point (pI) and then by mass [14]. | High-resolution proteomic analysis of complex protein mixtures from tissues or cells [14]. | Proteomic analysis of complex samples [14]. |

Gene Expression Analysis Using Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Principles of qPCR and Reverse Transcription qPCR (RT-qPCR)

Quantitative PCR (qPCR), also known as real-time PCR, is a fundamental technique for quantifying gene expression levels. Unlike traditional PCR that provides end-point detection, qPCR monitors the amplification of DNA in real-time during the exponential phase of the reaction, which provides the most reliable data for quantification [13]. The key output is the threshold cycle (Ct), which is the PCR cycle number at which the sample's fluorescence crosses a predetermined threshold, indicating a significant increase in amplified product [13].

For analyzing gene expression, RNA must first be reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) in a technique called reverse transcription qPCR (RT-qPCR) [13]. This method is exceptionally sensitive and can detect even low-abundance transcripts, making it ideal for studying subtle changes in gene expression in response to biomaterials or inflammatory stimuli [13] [15].

Detailed Protocol: RT-qPCR for Inflammatory Marker Gene Expression

Application Note: This protocol is designed to quantify the expression of inflammation-related genes (e.g., cytokines) in cells cultured on a novel biomaterial, compared to a control surface.

I. Sample Preparation and RNA Extraction

- Cell Culture: Seed cells onto the test biomaterial and control surface in culture plates. After the desired incubation period, lyse cells directly in the culture well.

- RNA Isolation: Use a commercial RNA extraction kit to purify total RNA. Treat samples with DNase I to remove genomic DNA contamination. Determine RNA concentration and purity using a spectrophotometer (e.g., A260/A280 ratio ~2.0 is ideal).

II. Reverse Transcription (cDNA Synthesis)

- Reaction Setup: Use a commercial reverse transcription kit. For a 20 µL reaction, combine:

- 1 µg of total RNA

- 1 µL of Oligo(dT)â‚₈ primer (or random hexamers)

- 4 µL of 5x Reaction Buffer

- 1 µL of Ribolock RNase Inhibitor (20 U)

- 2 µL of 10 mM dNTP Mix

- 1 µL of RevertAid Reverse Transcriptase (200 U)

- Nuclease-free water to 20 µL.

- Thermal Cycling: Incubate at 42°C for 60 minutes, followed by 70°C for 5 minutes to inactivate the enzyme. The resulting cDNA can be stored at -20°C.

III. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Setup

- Detection Chemistry: SYBR Green or TaqMan probes can be used. SYBR Green is more cost-effective and suitable for validating primer specificity, while TaqMan probes offer greater specificity through an additional hybridization step [13].

- Reaction Mixture: For a 20 µL reaction using SYBR Green:

- 10 µL of 2x SYBR Green Master Mix

- 0.8 µL of Forward Primer (10 µM)

- 0.8 µL of Reverse Primer (10 µM)

- 2 µL of cDNA template (diluted 1:10)

- 6.4 µL of Nuclease-free water.

- Primer Design: Primers should be designed to be sequence-specific. For plant genomes or genes with homologs, design primers based on single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to ensure specificity [12]. Amplicon length should typically be 85–125 bp [12].

- Thermal Cycling Protocol:

- Data Analysis: Use the comparative ΔΔCt method for relative quantification [13]. Normalize the Ct values of your target gene to the Ct values of a stable reference gene (e.g., GAPDH, β-actin) in the same sample. Calculate the fold-change in gene expression relative to the control group.

Optimization and Troubleshooting

- Primer and Assay Validation: It is critical to optimize primer sequences, annealing temperatures, and primer concentrations for each gene [12]. The amplification efficiency of the primer set should be between 90–110%, which can be validated using a standard curve with a serial dilution of cDNA [12] [13]. An R² ≥ 0.99 for the standard curve indicates excellent linearity [12].

- Annealing Temperature: If nonspecific amplification occurs (e.g., multiple peaks in a melt curve), increase the annealing temperature in 1-2°C increments. Use touchdown PCR for difficult targets [16].

- Inhibition: If amplification is inefficient, ensure the cDNA template is not contaminated with inhibitors from the RNA isolation or biomaterial itself. Test different dilutions of the cDNA.

Protein Analysis Using Electrophoresis

Principles of Protein Gel Electrophoresis

Protein gel electrophoresis is a standard laboratory technique that uses an electrical field to separate proteins through a porous matrix based on their size, charge, or a combination of both [14]. The most common form is sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), which denatures proteins and coats them with a negative charge, allowing separation strictly by molecular mass [14]. Other forms include native-PAGE for separating proteins in their native state and two-dimensional PAGE (2D-PAGE) for high-resolution separation of complex protein mixtures [14].

Detailed Protocol: SDS-PAGE for Protein Profiling

Application Note: This protocol is used to separate and visualize proteins isolated from cells interacting with a biomaterial, allowing for the analysis of protein expression levels, including key inflammatory mediators or regeneration markers.

I. Sample Preparation

- Protein Extraction: Lyse cells harvested from the biomaterial surface using RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors.

- Protein Denaturation: Mix the protein lysate with 2x or 4x Laemmli sample buffer (containing SDS and β-mercaptoethanol). Heat the samples at 70-100°C for 5-10 minutes to denature the proteins [14].

- Protein Quantification: Determine the protein concentration of each sample using a colorimetric assay (e.g., BCA assay). Adjust all samples to the same concentration with lysis buffer and sample buffer.

II. Gel Casting and Setup

- Gel Composition: SDS-PAGE uses a discontinuous gel system:

- Resolving Gel (Lower Gel): Typically 8-12% acrylamide, pH 8.8. This gel is responsible for separating proteins by size.

- Stacking Gel (Upper Gel): 4-5% acrylamide, pH 6.8. This gel concentrates all protein samples into a sharp band before they enter the resolving gel.

- Recipe for a 10% Resolving Gel (for one mini-gel):

- 4.0 mL of 30% Acrylamide/Bis Solution

- 2.5 mL of 1.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8

- 3.4 mL of dHâ‚‚O

- 0.1 mL of 10% SDS

- 0.1 mL of 10% Ammonium Persulfate (APS)

- 0.01 mL of TEMED

- Casting: Pour the resolving gel between glass plates and overlay with isopropanol to ensure a flat surface. After polymerization, pour off the isopropanol, pour the stacking gel, and immediately insert a comb.

III. Electrophoresis

- Loading: Load an equal amount of protein (e.g., 20-30 µg) per well. Include one well for a pre-stained protein molecular weight marker.

- Running Conditions: Fill the electrophoresis tank with 1x Tris-Glycine-SDS running buffer. Run the gel at a constant voltage (e.g., 80-120 V) until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel.

IV. Protein Detection

- Staining: After electrophoresis, carefully remove the gel from the cassette and stain with Coomassie Brilliant Blue or a more sensitive silver stain to visualize the protein bands.

- Western Blotting (Immunoblotting): For specific detection of a protein of interest (e.g., WSTF), transfer the separated proteins from the gel onto a nitrocellulose or PVDF membrane. Probe the membrane with a primary antibody specific to your target, followed by a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody. Detect the signal using a chemiluminescent substrate and imaging system.

Optimization and Troubleshooting

- Gel Percentage: Use lower percentage gels (e.g., 8%) for resolving high molecular weight proteins and higher percentage gels (e.g., 12-15%) for low molecular weight proteins [14]. Gradient gels (e.g., 4-20%) can resolve a broader range of protein sizes.

- Protein Smiling: Ensure the gel is run at a constant voltage and that the apparatus is cooled if necessary to prevent overheating, which can cause "smiling" bands.

- Transfer Efficiency: For western blotting, optimize transfer time and conditions to ensure complete transfer of proteins from the gel to the membrane, especially for high molecular weight targets.

Application in Biomaterials Research: An Integrated Workflow

The combination of PCR and electrophoresis is indispensable for evaluating the molecular-level interactions between biomaterials and biological systems. These techniques allow researchers to move beyond simple observation of cellular attachment and proliferation to a mechanistic understanding of how a material influences gene expression and protein synthesis, which ultimately dictates the host response—be it regenerative, fibrotic, or inflammatory [17].

An integrated experimental workflow for analyzing cellular response to a novel biomaterial might proceed as follows:

- In Vitro Culture: Culture relevant cell types (e.g., macrophages, fibroblasts, stem cells) on the test biomaterial and appropriate controls.

- Gene Expression Analysis: Harvest cells and perform RT-qPCR to quantify the expression of key marker genes. For inflammation, this might include pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α). For regeneration, growth factors (e.g., VEGF, TGF-β) or extracellular matrix components (e.g., Collagen I) are relevant.

- Protein Analysis: Analyze the same cell lysates via SDS-PAGE and western blotting to confirm that changes in mRNA translate to the protein level for critical targets, such as the WSTF protein [9] [10].

- Data Integration: Correlate the molecular data with functional cellular assays (e.g., migration, proliferation) to build a comprehensive picture of the biomaterial's performance.

This integrated approach provides robust data on biocompatibility and biofunctionality, guiding the rational design of next-generation biomaterials that actively promote healing and integration while minimizing adverse inflammatory responses [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Molecular Target Analysis

| Reagent/Kits | Function/Description | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| PCR Polymerases | Enzymes that synthesize new DNA strands. Specialized versions exist for different needs (e.g., high-fidelity, GC-rich templates) [16]. | PrimeSTAR GXL for long templates; enzymes with GC buffer for high GC-content genes [16]. |

| SYBR Green Master Mix | Fluorescent dye that intercalates into double-stranded DNA, allowing real-time quantification of PCR products [13]. | General qPCR gene expression analysis for one or a few targets. |

| TaqMan Assays | Sequence-specific probes labeled with a reporter fluorophore, providing high specificity for target detection [13]. | Multiplex qPCR, discriminating between closely related gene homologs or splice variants. |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | Contain enzymes and reagents to convert RNA into cDNA for downstream PCR applications [13]. | First step in two-step RT-qPCR for analyzing multiple targets from a single RNA sample. |

| Precast Polyacrylamide Gels | Ready-to-use protein gels of various percentages and formats, ensuring consistency and saving time [14]. | Standardized SDS-PAGE for protein separation and western blotting. |

| Protein Molecular Weight Markers | A mixture of proteins of known molecular weights, run alongside samples to estimate protein size [14]. | Essential for determining the approximate mass of separated proteins on SDS-PAGE. |

| Primary & Secondary Antibodies | Immunoreagents for specific detection of target proteins in techniques like western blotting and immunohistochemistry. | Detecting specific protein targets like WSTF [9] in cell lysates or tissue sections. |

| Haloperidol Decanoate | Haloperidol Decanoate - CAS 74050-97-8 For Research | Haloperidol decanoate is a potent dopamine antagonist for psychiatric research. This product is for research use only and is not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic applications. |

| Hexadecylphosphoserine | Hexadecylphosphoserine, CAS:133321-35-4, MF:C19H40NO6P, MW:409.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The central hypothesis that biomaterials actively influence gene expression patterns in surrounding cells is fundamentally reshaping regenerative medicine and therapeutic development. Biomaterials are no longer considered inert structural supports; they are dynamic interfaces that engage in complex dialogue with biological systems [18]. This interaction triggers precise transcriptional changes that dictate critical outcomes such as cellular heterogeneity, immune response, and tissue regeneration [18].

The emerging framework of the "Biomaterial-mediated Cell Atlas" (BCA) provides a comprehensive approach to characterizing these responses at single-cell resolution [18]. This concept extends the Human Cell Atlas initiative by mapping how physical, chemical, and biological cues from materials redirect cellular function through gene regulation. Understanding these mechanisms requires sophisticated molecular tools, with reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and electrophoresis forming the foundational methodologies for quantifying these biomaterial-driven genetic changes.

Table 1: Key Aspects of the Biomaterial-mediated Cell Atlas (BCA)

| BCA Aspect | Role in Gene Expression Analysis | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Safety | Assesses biocompatibility and toxicological responses | Identifying pro-inflammatory gene expression patterns [18] |

| Bioactivity | Evaluates capacity to positively influence tissue | Measuring pro-regenerative gene upregulation [18] |

| Immune Microenvironment | Analyzes immune reactions to foreign material | Characterizing immunomodulatory gene signatures [18] |

Quantitative Analysis of Gene Expression in Biomaterial Research

Methodological Comparison

Accurate gene expression analysis is crucial for testing the central hypothesis. The choice between endpoint and quantitative PCR methodologies involves significant trade-offs in precision, throughput, and cost [19] [20].

Table 2: Comparison of PCR Methodologies in Biomaterial Research

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Ideal Application in Biomaterials |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endpoint PCR | Amplification with analysis after final cycle | Inexpensive; simple visualization; no specialized equipment required [20] | Semi-quantitative; low sensitivity; plateau effect masks true expression differences [19] [20] | Initial screening for transcript presence/absence; quality control of RNA samples [19] |

| Gel-Based RT-PCR | Reverse transcription followed by endpoint PCR with gel visualization | Confirms specific amplicon; identifies nonspecific amplification; relatively inexpensive [19] | Limited quantitative accuracy; requires post-reaction processing; ethidium bromide staining potential mutagen [19] | Verifying primer specificity; analyzing splice variants; when transcript abundance is high [19] |

| Absolute Quantitative RT-PCR | Real-time monitoring during exponential phase with standard curve | Highest accuracy; determines actual transcript copy numbers; broad dynamic range [20] | Technically demanding; requires precise standards; higher cost per sample [20] | Precise quantification of osteogenic markers (e.g., osteocalcin) in engineered constructs [20] |

| Relative Quantitative RT-PCR | Normalization to housekeeping genes during exponential phase | Controls for sample-to-sample variation; no need for absolute standards; well-established protocols [20] | Expression reported as ratios; sensitive to reference gene stability; biological meaning can be obscured [20] | Comparing expression fold-changes across multiple experimental conditions [20] |

Key Findings from Biomaterial Gene Expression Studies

Quantitative analysis has revealed how specific material properties translate into transcriptional programs:

- Osteogenic Differentiation: Absolute quantification demonstrated that human fetal osteoblasts (hFOBs) cultured under osteogenic conditions showed significantly elevated osteocalcin expression compared to normal culture conditions, providing molecular validation of biomaterial-induced differentiation [20].

- Immune Response Profiling: Single-cell transcriptomics of cells interacting with implants has revealed previously unappreciated heterogeneity in immune responses, including distinct macrophage polarization states that correlate with material surface properties [18].

- Resource Reallocation: Recent RNA-sequencing of cells expressing synthetic genetic circuits (iFFLs) revealed differential expression in pathways related to RNA processing, translation, and metabolism, suggesting biomaterials can trigger cellular resource redistribution that impacts transgene expression [21].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Template Preparation Using PBC Method

This rapid potassium hydroxide-based method efficiently prepares PCR templates from diverse microorganisms [22].

Reagents and Equipment

- Potassium hydroxide (KOH), 0.1 M

- Microcentrifuge tubes

- Thermal block or water bath (100°C)

- Centrifuge

- Microbial cultures

Procedure

- Transfer 10-20 μL of microbial culture to a microcentrifuge tube.

- Add an equal volume of 0.1 M KOH solution.

- Incubate the mixture at 100°C for 10 minutes in a thermal block.

- Centrifuge the tubes at 12,000 × g for 5 minutes.

- Use 1-2 μL of the suspended sediment as template in a 25 μL PCR reaction.

- Store remaining template at -20°C for future use.

Technical Notes

- The PBC method works for diverse microorganisms including bacteria (E. coli), fungi (S. cerevisiae), and oomycetes [22].

- This method generates primarily damaged cells and cell-bound DNA rather than free naked DNA [22].

- For Gram-positive bacteria with tough cell walls, extend the boiling time to 15 minutes.

- Avoid using >2 μL of template per 25 μL reaction to prevent inhibitors from affecting PCR efficiency.

Protocol 2: Gel-Based RT-PCR for Transcript Detection

This protocol provides a balance between sensitivity and technical accessibility for detecting transcripts in biomaterial-related samples [19].

Reagents and Equipment

- RNA isolation reagent (e.g., Trizol) or kit (e.g., RNeasy Mini Kit)

- RNase-Free DNase Set

- Access RT-PCR System

- Specific primers for target gene

- Thermal cycler

- Agarose gel electrophoresis equipment

- Ethidium bromide or SYBR-safe DNA gel stain

Procedure

Part A: RNA Isolation and Quantitation

- Homogenize biomaterial-exposed tissue or cells in Trizol reagent, maintaining samples on dry ice to prevent RNA degradation [19].

- Isolate total RNA following manufacturer's protocol, including a DNase digestion step to remove genomic DNA contamination [19].

- Quantitate RNA using fluorescence-based methods (e.g., Quant-iT Ribogreen RNA assay) for superior accuracy over absorbance methods [19].

Part B: RT-PCR Amplification

- Prepare RT-PCR master mix on ice: 1× RT-PCR buffer, 0.2 mM each dNTP, 1.0 mM MgSO₄, 0.3 μM each primer, 5 U of reverse transcriptase, 5 U of DNA polymerase.

- Add 100-500 ng of total RNA template to the reaction mix.

- Program thermal cycler: Reverse transcription at 48°C for 45 min; initial denaturation at 94°C for 2 min; 30-40 cycles of: denaturation at 94°C for 30 sec, annealing at 55-65°C for 30 sec, extension at 72°C for 1 min/kb; final extension at 72°C for 10 min [19].

- Include no-template controls and positive controls in each run.

Part C: Gel Electrophoresis and Visualization

- Prepare 1-2% agarose gel in 1× TAE buffer with nucleic acid stain.

- Mix 5-10 μL of each RT-PCR product with 6× loading dye and load into wells alongside DNA molecular weight marker.

- Run gel at 5-8 V/cm distance between electrodes until adequate separation achieved.

- Visualize bands under UV transillumination and document with imaging system.

Technical Notes

- Cycle number optimization is critical: too few cycles may miss low-abundance transcripts, while too many cycles can obscure expression differences due to plateau effects [19].

- Always confirm a single dominant amplicon of expected size to rule out nonspecific amplification [19].

- For semi-quantitative comparison, ensure all samples are in the linear phase of amplification by testing different cycle numbers [19].

Protocol 3: Absolute Quantification Using Real-Time PCR

This method provides the highest accuracy for quantifying transcript copy numbers in cells responding to biomaterials [20].

Reagents and Equipment

- Real-time PCR system

- Quantified PCR standards (purified target amplicon)

- RNA isolation and DNase treatment reagents

- One-step or two-step RT-PCR kit with fluorescence detection

- Gene-specific primers (and probes if using TaqMan chemistry)

Procedure

- Isolve total RNA from biomaterial-cultured cells using rigorous DNase treatment to prevent genomic DNA contamination [20].

- Generate standards by purifying target amplicon from positive control cDNA using preparative PCR and gel extraction [20].

- Quantify purified amplicon spectroscopically at 260 nm and calculate copy number based on molecular weight [20].

- Prepare 10-fold serial dilutions of standard amplicon (10ⷠto 10¹ copies/μL).

- Set up real-time PCR reactions with standards, test samples, and no-template controls.

- Run amplification with appropriate cycling conditions and fluorescence acquisition.

- Generate standard curve from dilution series and calculate copy numbers in unknown samples from the curve [20].

Technical Notes

- Using PCR-generated standards eliminates molecular cloning steps, simplifying the absolute quantification process [20].

- Verify standard amplicon sequence to ensure accurate quantification of the correct target [20].

- Include a reverse transcription negative control to confirm absence of genomic DNA amplification.

Visualization: Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Biomaterial-Induced Gene Expression Pathway

Gene Expression Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Biomaterial Gene Expression Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Isolation Kits | RNeasy Mini Kit, ZR-Whole Blood Total RNA Kit [19] | High-quality RNA extraction from biomaterial-cultured cells and tissues |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Access RT-PCR System [19] | cDNA synthesis from RNA templates; combined systems streamline workflow |

| DNA Polymerases | Taq DNA polymerase, High-fidelity enzymes [23] | PCR amplification; choice depends on need for speed, fidelity, or GC-rich targets |

| Specialized PCR Kits | Direct PCR kits, Hot-start enzymes [23] | Amplification from crude samples (Direct PCR); reduced primer-dimer formation (Hot-start) |

| Nucleic Acid Stains | Ethidium bromide, SYBR-safe [19] [23] | DNA visualization in gels; SYBR-safe offers safer alternative to ethidium bromide |

| Quantitation Assays | Quant-iT Ribogreen RNA assay [19] | Accurate RNA quantification superior to A260/A280 measurements |

| Electrophoresis Systems | Invitrogen E-gel system [23] | Pre-cast agarose gels for streamlined, buffer-less nucleic acid separation |

| 3,29-O-Dibenzoyloxykarounidiol | 3,29-O-Dibenzoyloxykarounidiol, CAS:118117-31-0, MF:C30H48O2, MW:440.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Histidinomethylalanine | Histidinomethylalanine, CAS:88495-09-4, MF:C10H16N4O4, MW:256.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The field of biomaterial science has revolutionized biomedical research, providing advanced tools for studying cellular responses. Three-dimensional (3D) scaffolds and nanoparticles have emerged as pivotal platforms for creating biologically relevant microenvironments in vitro. These materials more accurately mimic the native extracellular matrix (ECM) compared to traditional two-dimensional cultures, leading to more physiologically relevant cellular behavior and gene expression patterns [24]. The analysis of this cellular response, particularly through nucleic acid techniques like polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and gel electrophoresis, is fundamental for evaluating the performance and safety of these novel biomaterials. This application note details the material considerations and protocols for integrating 3D scaffold and nanoparticle technologies with standard nucleic acid analysis methods, providing a framework for researchers in biomaterial development and drug discovery.

Material Considerations for 3D Scaffolds

In tissue engineering, scaffolds are not merely passive support structures but active components that direct cell fate through biochemical and biophysical cues. The material properties of a scaffold directly influence cell attachment, proliferation, differentiation, and ultimately, the transcriptional profile of the cells, which is measurable via nucleic acid analysis [24].

Key Scaffold Properties and Their Impact on Cellular Response

The table below summarizes critical scaffold properties and their quantitative influence on cellular behavior, which can be assessed via PCR analysis of specific genetic markers.

Table 1: Key Scaffold Properties and Their Cellular Implications

| Property | Ideal Target/Example Value | Cellular Impact & Analyzable Markers |

|---|---|---|

| Porosity | Highly porous (>90% interconnectivity desirable) [24] | Enables cell migration & nutrient diffusion. PCR can analyze markers for cell invasion (e.g., MMPs) and hypoxia (e.g., HIF-1α). |

| Mechanical Strength | Wide-ranging (e.g., Cortical Bone: ~200 MPa; Trabecular Bone: ~2.5 MPa) [24] | Directs stem cell lineage. Adhesion/spacing of ~34 nm promotes osteogenesis, while ~63 nm promotes adipogenesis [24]. |

| Surface Topography | Nanofibrous structures mimicking native ECM [24] | Enhances cell adhesion and signaling. Upregulates expression of differentiation markers (e.g., RUNX2 for osteoblasts) [24]. |

| Bioactivity | Incorporation of nanoclays, NPs, carbon nanotubes [24] | Can enhance electroconductivity (e.g., for cardiac tissue) or provide antimicrobial activity. PCR can monitor functional gene expression. |

Experimental Protocol: RNA Extraction from 3D Scaffold Cultures

Analyzing the cellular response from 3D cultures requires optimized nucleic acid extraction protocols to account for the complex material matrix.

Materials:

- Cell-laden 3D scaffold

- TRIzol Reagent or equivalent

- Chloroform

- Isopropanol

- 75% Ethanol (in DEPC-treated water)

- RNase-free water

- Liquid nitrogen and mortar/pestle (for non-degradable, rigid scaffolds) or direct homogenization (for soft/hydrogel scaffolds)

Method:

- Termination of Culture & Harvesting: At the desired time point, carefully remove the cell-scaffold construct from culture media. Gently wash with cold 1X PBS to remove residual serum and media.

- Scaffold Disruption:

- For soft/hydrogel scaffolds: Transfer the construct to a microcentrifuge tube containing TRIzol. Homogenize thoroughly using a motorized pellet pestle or by pipetting until no visible fragments remain.

- For rigid/scaffolds: Flash-freeze the construct in liquid nitrogen. Using a pre-cooled mortar and pestle, pulverize the scaffold into a fine powder. Transfer the powder to TRIzol.

- Phase Separation: Incubate the homogenate for 5 minutes at room temperature. Add 0.2 ml of chloroform per 1 ml of TRIzol used. Cap the tube securely and shake vigorously by hand for 15 seconds. Incubate at room temperature for 2-3 minutes.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the mixture at 12,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The mixture will separate into a red lower phenol-chloroform phase, an interphase, and a colorless upper aqueous phase containing the RNA.

- RNA Precipitation: Transfer the aqueous phase to a new RNase-free tube. Precipitate the RNA by adding 0.5 ml of isopropanol per 1 ml of TRIzol used. Mix and incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes.

- RNA Wash: Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. A gel-like pellet will form. Carefully remove the supernatant. Wash the RNA pellet with 1 ml of 75% ethanol by vortexing and subsequent centrifugation at 7,500 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C.

- Redissolution: Air-dry the pellet for 5-10 minutes (do not over-dry). Dissolve the RNA in 20-50 µl of RNase-free water. Quantify the RNA concentration and purity using a spectrophotometer (e.g., Nanodrop). Store at -80°C.

Diagram 1: RNA Extraction from 3D Scaffolds Workflow

Nanotechnology and Nanoparticle Integration

Nanotechnology offers powerful strategies to functionalize scaffolds and interact with biological systems at a molecular level. Nanoparticles (NPs) can be incorporated into 3D scaffolds to impart new functionalities such as localized drug delivery, enhanced imaging, and improved mechanical or electrical properties [24] [25].

Types and Applications of Functional Nanoparticles

The selection of nanoparticle type is critical and depends on the intended application in biomaterial design and analysis.

Table 2: Functional Nanoparticles for Biomaterial Enhancement

| Nanoparticle Type | Key Characteristics | Application in Biomaterials & Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Metallic NPs (e.g., Gold, Iron Oxide) | Strong optical properties, superparamagnetism [25] | Imaging contrast agents, photothermal therapy, antimicrobial activity (Ag NPs) [24] [26]. |

| Polymeric NPs (e.g., PLGA) | Biodegradable, tunable release kinetics [25] | Controlled delivery of growth factors, antibiotics (e.g., Vancomycin [26]), or siRNA to cells within the scaffold. |

| Lipid NPs (e.g., PEGylated Liposomes) | High biocompatibility, drug encapsulation efficiency [25] | Delivery of hydrophobic/hydrophilic drugs (e.g., Doxorubicin [25]). Model systems for studying NP-cell interactions. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | High electroconductivity, mechanical strength [24] | Incorporated into scaffolds for cardiac or neural tissue engineering to enhance electrical signal propagation. |

| DNA-Programmed NPs | Precise 3D organization via DNA origami [27] [28] | Creation of highly structured materials for biosensing and as programmable scaffolds for studying cell-material interactions. |

DNA-Programmable Assembly for Advanced Materials

A groundbreaking approach in nanomaterial science involves using DNA as a programmable "smart glue" to assemble nanoparticles into precise 3D architectures. DNA origami allows the creation of nanostructures (e.g., octahedral "voxels") with specific binding sites, enabling the construction of complex, pre-designed superlattices that can host various "nanocargo" such as proteins, enzymes, or inorganic NPs [27] [28]. The inverse design algorithm, MOSES (Mapping Of Structurally Encoded aSsembly), helps define the minimal set of DNA voxels and bond types required to form a target structure, streamlining the fabrication of sophisticated materials for analytical applications [28].

Nucleic Acid Analysis Protocols

The cellular response to these advanced materials is ultimately decoded by analyzing changes in gene expression using robust nucleic acid techniques.

Protocol: Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

PCR is a cornerstone technique for amplifying specific DNA sequences, enabling the detection and analysis of minute quantities of genetic material [7].

Principle: The technique involves repeated cycles of thermal denaturation of double-stranded DNA, annealing of sequence-specific primers, and extension of the primers by a thermostable DNA polymerase (e.g., Taq polymerase), resulting in the exponential amplification of the target sequence [29] [7].

Reaction Setup: Table 3: Components of a Standard PCR Reaction [7]

| Component | Final Concentration/Amount | Function |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Template | 1-100 ng (or 1-10 ng for cDNA) | The sample containing the target sequence to be amplified. |

| Forward & Reverse Primers | 0.1-1.0 µM each | Short, single-stranded DNA molecules that define the start and end of the target sequence. |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | 0.5-2.5 units/50 µL reaction | Enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands by adding dNTPs. |

| dNTP Mix | 200 µM each | Building blocks (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) for new DNA synthesis. |

| Reaction Buffer | 1X | Provides optimal pH and salt conditions (often includes MgClâ‚‚, a cofactor for Taq polymerase). |

| Nuclease-free Water | To volume | To bring the reaction to the final volume. |

Thermal Cycler Protocol:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2-5 minutes (activates polymerase, denatures template).

- Amplification Cycles (25-40 cycles):

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15-30 seconds.

- Annealing: 55-72°C for 15-60 seconds (temperature is primer-specific).

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kb of amplicon.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes.

- Hold: 4°C ∞.

Diagram 2: Standard PCR Thermal Cycling Process

Protocol: Agarose Gel Electrophoresis

This technique is used to separate, identify, and size PCR products based on their molecular weight [29].

Materials:

- Agarose

- TAE or TBE electrophoresis buffer

- DNA ladder (molecular weight standard)

- Loading dye (e.g., with bromophenol blue)

- Ethidium bromide or SYBR Safe DNA gel stain

- Gel electrophoresis tank and power supply

- UV transilluminator or gel doc system

Method:

- Gel Preparation: Prepare a 1-2% agarose solution by dissolving agarose in electrophoresis buffer by heating. Allow to cool slightly, add nucleic acid stain (e.g., Ethidium Bromide, caution: mutagen), and pour into a gel tray with a comb.

- Sample Loading: Once solidified, place the gel in the electrophoresis tank and submerge with buffer. Mix PCR samples with loading dye. Load the DNA ladder and samples into the wells.

- Electrophoresis: Run the gel at 5-10 V/cm distance between electrodes until the dye front has migrated sufficiently.

- Visualization: Visualize the gel under UV light. The amplified PCR product should appear as a discrete band at the expected size relative to the ladder.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents for Biomaterial-Nucleic Acid Research

| Item/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Scaffold Materials | Natural (Collagen, Chitosan); Synthetic (PLGA, PCL); Hydrogels (Alginate, PEGDA) [24] | Provide 3D structural support for cells, mimicking the native tissue microenvironment. |

| Functional Nanoparticles | Gold NPs, PLGA NPs, PEGylated Liposomes, Mesoporous Silica NPs (MSNs) [26] [25] | Enhance scaffold functionality (drug delivery, imaging, antimicrobial activity). |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | TRIzol-based kits, Silica-membrane column kits | Isolate high-quality, intact DNA/RNA from complex 3D cell-scaffold constructs. |

| PCR Master Mix | Pre-mixed solutions containing Taq polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, Mg²⺠| Simplify PCR setup, ensure reaction consistency, and improve amplification efficiency. |

| Reverse Transcriptase | M-MLV, AMV | Synthesize complementary DNA (cDNA) from RNA templates for gene expression analysis (RT-PCR). |

| DNA Ladders & Stains | 100 bp DNA Ladder, Ethidium Bromide, SYBR Safe | Provide molecular weight standards for gel electrophoresis and enable DNA band visualization. |

| Homatropine Methylbromide | Homatropine Methylbromide, CAS:80-49-9, MF:C17H24BrNO3, MW:370.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Hydroquinone diacetate | Hydroquinone diacetate, CAS:1205-91-0, MF:C10H10O4, MW:194.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

A Step-by-Step Guide to Nucleic Acid Analysis for Biomaterial Testing

Protocol for Preparing Biomaterial Extracts and Cell Cultures

Evaluating the biological safety and performance of biomaterials is a critical step in medical device development and drug research. This process involves preparing extracts from the biomaterial to simulate leachable substances and then exposing these extracts to cell cultures to assess their biological response. The data generated is often analyzed using sophisticated molecular techniques, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and electrophoresis, to understand specific cellular responses at the genetic level. This protocol outlines a detailed, step-by-step procedure for preparing biomaterial extracts and subsequent cell cultures, framed within the context of a broader research thesis utilizing PCR and electrophoresis for biomaterial cellular response research. It integrates the latest regulatory considerations, including the FDA's September 2024 draft guidance on chemical characterization, to ensure the analytical chemistry studies are consistent and reliable [30] [31].

Background and Regulatory Context

Chemical characterization of medical device materials is used to identify and quantify the chemical substances that may be released from a device into the body. This process helps address potential biological risks and can serve as a supportive or alternative approach to some animal testing when followed by a toxicological risk assessment (TRA) according to ISO 10993-17 [31] [32]. The US FDA's draft guidance "Chemical Analysis for Biocompatibility Assessment of Medical Devices," released in September 2024, provides a comprehensive framework for these assessments, aligning with ISO 10993-18 and focusing on extraction, chemical analysis, and reporting requirements [30].

The fundamental principle of extract preparation is to use conditions that exaggerate or provide a worst-case estimate of the clinical use conditions. This ensures a safety margin by identifying potential leachables that might be released over the device's intended contact duration [32]. The resulting extracts are then applied to cell cultures to evaluate endpoints such as cytotoxicity (cell death), genotoxicity (DNA damage), and other metabolic functions, with downstream analysis via PCR and electrophoresis providing granular data on gene expression and DNA integrity.

Materials and Equipment

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and their functions in the preparation of biomaterial extracts and cell cultures.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent/Material | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Polar Solvent (e.g., Physiological Saline) | Aqueous extractant for polar and ionic leachables, simulating body fluids like blood and serum [33] [32]. |

| Non-Polar Solvent (e.g., Vegetable Oil) | Lipid-soluble extractant for non-polar leachables, simulating contact with fatty tissues [33]. |

| Semi-Polar Solvent (e.g., Ethanol/Water Mixtures) | Recommended for devices with long-term contact; can extract a broader range of compounds [30] [32]. |

| Cell Culture Media (e.g., DMEM, RPMI) | Provides essential nutrients, hormones, and growth factors to sustain cells ex vivo during biocompatibility testing [34] [35]. |

| Agarose | A polysaccharide powder used to create gels for the electrophoretic separation of DNA fragments by size [36]. |

| TBE (Tris/Borate/EDTA) Buffer | Provides the ionic environment and pH control necessary to conduct electrical current and maintain DNA integrity during electrophoresis [36]. |

| DNA Safe Stain | A fluorescent dye that intercalates with DNA fragments, allowing for visualization under UV or blue light transillumination [36]. |

| Loading Dye | Adds density to DNA samples for easy loading into gel wells and contains a visible dye to track migration progress [36]. |

| DNA Ladder | A molecular weight standard containing DNA fragments of known sizes, enabling the estimation of unknown fragment sizes in samples [36]. |

Laboratory Equipment

- Biomaterial Processing Tools: Sterile scalpels, scissors, or cryogenic mill for sample preparation.

- Extraction Vessels: Sealed containers (e.g., glass vials) with minimal headspace, chemically inert [30] [32].

- Incubator or Oven: For maintaining precise extraction temperatures (e.g., 37°C, 50°C, 70°C) [33].

- Mechanical Agitation Device: Such as an orbital shaker, to ensure continuous, uniform contact between the biomaterial and solvent [30].

- Analytical Balance: High-sensitivity balance capable of measuring down to 10-100 micrograms for Non-Volatile Residue (NVR) analysis [30].

- Cell Culture Facility: Including biosafety cabinet, COâ‚‚ incubator, centrifuges, and microscopes.

- Gel Electrophoresis System: Including a gel tray, comb, power supply, and visualization system (e.g., gel doc) [36].

- Thermal Cycler: For performing PCR amplification.

Experimental Protocol

Part I: Preparation of Biomaterial Extracts

Step 1: Information Gathering and Test Article Selection

Before testing, conduct thorough information gathering on the device, including:

- Materials of Construction: List all constituents, including polymers, plasticizers, colorants, and manufacturing aids (e.g., lubricants, mold release agents) [30] [33].

- Device Configuration and Intended Use: Understand the clinical exposure (contact duration, tissue type, temperature) to define the worst-case scenario [30] [32].

- Select the Test Article: The device should be in its final, clinically representative form, having undergone all manufacturing, packaging, and sterilization steps. If the entire device cannot be used, a representative section containing all material types may be used with justification. The test article should represent a worst-case exposure scenario [30] [33] [32].

Step 2: Determination of Extraction Conditions

The extraction conditions should be selected based on the device's intended use and should exceed clinical conditions to produce a worst-case extract.

Table 2: Guidelines for Selecting Extraction Conditions

| Parameter | Options and Guidelines |

|---|---|

| Solvents | Use polar (saline) and non-polar (oil) solvents as a minimum. For long-term devices, include a semi-polar solvent (e.g., ethanol-water mixture). Prefer neat solvents over mixtures; justify any deviations [30] [32]. |

| Temperature & Duration | Should be exaggerated. Common conditions include: 37°C for 24-72 hours, 50°C for 72 hours, 70°C for 24 hours, or 121°C for 1 hour. The choice must be justified based on the clinical worst-case and material thermal properties [33] [32]. |

| Extraction Exhaustiveness | For prolonged/long-term devices, perform exhaustive extraction until the amount of extractable material in a subsequent cycle is <10% of the initial cycle (determined gravimetrically) [32]. |

| Surface Area-to-Volume Ratio | Follow ISO 10993-12 guidelines. A common ratio is 6 cm²/mL for materials ≤ 0.5 mm thick and 3 cm²/mL for materials > 0.5 mm thick. For irregular shapes, use 0.1-0.2 g/mL [33]. |

Step 3: Performing the Extraction

- Prepare the Test Article: Subdivide the device if necessary under clean conditions to avoid contamination. Record the final surface area or mass.

- Conduct Solvent Compatibility (if needed): For novel materials, a pre-study evaluating at least three solvents of the same polarity is recommended to identify which causes the least swelling or degradation [30].

- Perform the Extraction:

- Place the test article in a sealed extraction vessel.

- Add the predetermined volume of solvent, ensuring the article is completely immersed with minimal headspace [32].

- Place the vessel in an incubator/oven at the selected temperature for the specified duration with continuous mechanical agitation [30].

- Perform extractions in triplicate for each solvent to account for device variability, unless justification is provided (e.g., devices are pooled to obtain sufficient extract volume) [32].

- Post-Extraction Handling:

- After extraction, visually inspect the test article and extract. Note any changes like cloudiness, particulates, or material degradation. The presence of particulates may require analysis per ISO/TS 10993-19 [32].

- For volatile compound analysis (via HS-GC-MS), analyze the extract immediately.

- Store extracts appropriately before biological testing, noting that storage conditions should not alter the chemical profile.

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key stages of the biomaterial extract preparation process:

Part II: Cell Culture Preparation and Dosing

Step 1: Cell Line Selection and Culture

- Select Appropriate Cell Line: Common choices include mammalian cell lines like Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) or human-derived lines like HEK293 for general biocompatibility, or more specialized primary cells like Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) for specific immune responses [34] [35].

- Culture and Maintain Cells: Grow cells in optimal serum-free or chemically defined media in a humidified CO₂ incubator at 37°C. Using chemically defined media (CDM) eliminates variability from animal-derived components and simplifies regulatory compliance [34].

- Optimize Media (if necessary): For specific applications (e.g., maintaining PBMC viability or recombinant protein production), media may need optimization. Advanced methods like Bayesian Optimization (BO) can efficiently identify optimal media compositions with fewer experiments than traditional Design of Experiments (DoE) [35].

Step 2: Exposing Cell Cultures to Biomaterial Extracts

- Prepare Test Concentrations: Aseptically filter the biomaterial extract if necessary. The extract is often applied to cells at 100% concentration, but serial dilutions (e.g., 1:2, 1:10 in culture medium) may be used to establish a dose-response relationship.

- Apply Extract to Cells: Plate cells at a predetermined density and allow them to adhere and stabilize (typically 24 hours). Remove the growth medium and replace it with the medium containing the biomaterial extract. Include control groups: a negative control (cells with culture medium and pure extraction solvent) and a positive control (cells with a known cytotoxic agent) [33].

- Incubation: Incubate the cells for a predetermined period (e.g., 24, 48, or 72 hours) based on the biological endpoint being investigated.

Integration with PCR and Electrophoresis for Cellular Response Analysis

Following exposure, the cellular response is analyzed. PCR and electrophoresis are key for assessing genetic-level changes.

- RNA/DNA Extraction: After the exposure period, extract total RNA to analyze gene expression (via Reverse Transcription PCR or qRT-PCR) or DNA to assess genomic integrity (e.g., for genotoxicity) or specific edits (e.g., in CRISPR-Cas9 studies) [37].

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): Amplify specific target sequences. For gene expression analysis, qRT-PCR is used to quantify transcript levels of genes related to stress response, inflammation (e.g., cytokines), or apoptosis. In gene editing research, PCR is used to verify the success of edits in primary cells like Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells (HSPCs) [37].

- Gel Electrophoresis: Analyze the PCR products.

- Prepare a 1-2% Agarose Gel: Dissolve agarose in TBE buffer by heating, cool to ~55°C, add DNA Safe Stain, and pour into a gel tray with a comb [36].

- Load and Run the Gel: Mix PCR products with loading dye and load into wells alongside a DNA ladder. Run at 50-100V for 30-60 minutes [36].

- Visualize: Under UV/blue light, DNA fragments will appear as bands. Compare against the ladder for size determination and observe band patterns and intensities for qualitative and semi-quantitative analysis.

The following diagram illustrates the workflow from cell culture to molecular analysis:

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Gel Electrophoresis Analysis: The presence, absence, or smearing of DNA bands can indicate genotoxic effects. The intensity of bands from qRT-PCR products can be used for semi-quantitative analysis of gene expression.

- Toxicological Risk Assessment (TRA): For chemical characterization, identified extractables above the Analytical Evaluation Threshold (AET) must undergo a TRA per ISO 10993-17 to determine if the exposure level poses a risk to patients [31] [32].

This detailed protocol provides a robust framework for preparing biomaterial extracts and corresponding cell cultures, directly supporting downstream molecular analyses like PCR and electrophoresis. Adherence to the latest regulatory drafts, such as the FDA's 2024 guidance, ensures that the chemical characterization is rigorous, justified, and forms a solid foundation for assessing the biological safety of medical devices and biomaterials [30] [31]. This integrated approach from material extraction to genetic analysis is indispensable for modern biomaterial research and development.

The isolation of high-quality nucleic acids from cell-biomaterial constructs presents unique challenges for researchers investigating cellular responses through PCR and electrophoresis. These constructs often incorporate complex scaffolds, hydrogels, and engineered tissues that introduce high levels of polysaccharides, secondary metabolites, and polymers that co-precipitate with DNA and RNA, leading to degradation and poor yield [38]. Success in downstream applications including quantitative PCR, RNA sequencing, and genotyping depends entirely on the initial quality of isolated nucleic acids. This application note provides detailed, validated protocols and comparative data to guide researchers in selecting and implementing optimal isolation strategies for these challenging sample types, with direct application to biomaterial cellular response research.

Comparative Analysis of Nucleic Acid Isolation Techniques

The selection of an appropriate nucleic acid isolation method is critical when working with cell-biomaterial constructs. The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of major technique categories evaluated for challenging sample types.

Table 1: Comparison of Nucleic Acid Isolation Techniques for Complex Biomaterial Constructs

| Technique | Expected Yield | Purity (A260/A280) | Best Application | Technical Complexity | Cost | Suitability for Downstream Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenol-Chloroform (Guanidinium-based) | High | Moderate (1.7-1.9) | RNA isolation from polysaccharide-rich constructs | High | Low | RT-qPCR, RNA sequencing |

| Silica Column-Based | Moderate | High (1.8-2.0) | High-throughput DNA isolation | Medium | Medium | PCR, genotyping, sequencing |

| Magnetic Bead-Based | Variable | High (1.8-2.0) | Automated high-throughput processing | Low to Medium | Medium to High | All molecular applications |

| Cesium Chloride Gradient | High | Very High (>2.0) | Plasmid DNA purification from constructs | Very High | High | Transfection, cloning |

Recent comparative studies on difficult plant and tissue samples have demonstrated that conventional phenol-chloroform methods, particularly those incorporating guanidinium thiocyanate, consistently yield DNA of superior purity and concentration compared to many commercial kits when processing materials with high secondary metabolite content [38]. For RNA isolation, a hybrid approach combining modified commercial kits with conventional techniques has shown exceptional results, producing RNA with high concentration and purity suitable for even the most sensitive downstream applications like RNA-Seq [38].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and kits form the foundation of successful nucleic acid isolation from cell-biomaterial constructs.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Nucleic Acid Isolation

| Reagent/Kits | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Guanidinium Thiocyanate | Protein denaturation, nuclease inhibition | Essential for RNA stability during homogenization; effective for polysaccharide-rich constructs [39]. |

| Silica Matrix Columns | Nucleic acid binding and purification | Selective binding in presence of high salt; effective for DNA removal in RNA protocols [39]. |

| Magnetic Silica Beads | Selective nucleic acid capture | Enable automation; effective with small sample volumes; reduce polysaccharide carryover [39]. |

| RNase Inhibitors | Protection of RNA integrity | Critical during RNA isolation from active cellular constructs; required in lysis buffers. |

| Phase Lock Gel | Interface separation | Improves phenol-chloroform separation; increases nucleic acid recovery [39]. |

| DNase I (RNase-free) | DNA removal | Essential for pure RNA isolation; must be effectively removed or inactivated post-treatment. |

| QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit | DNA fragment purification | Enables purification of specific DNA fragments from agarose gels [40]. |

Validated Protocols for High-Quality Nucleic Acid Isolation

Combined Guanidinium-Thiocyanate-Phenol-Chloroform RNA Protocol

This protocol has been specifically adapted for cell-biomaterial constructs with high polysaccharide content and yields RNA with high purity suitable for RT-qPCR and transcriptomic analysis.

Reagents Required:

- Lysis Buffer: 4M guanidinium thiocyanate, 25mM sodium citrate, 0.5% N-lauroylsarcosine, 0.1M 2-mercaptoethanol

- Acid Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol (125:24:1)

- Isopropanol

- 75% Ethanol

- Nuclease-free Water

Procedure:

- Homogenization: Resuspend cell-biomaterial construct in 800μL lysis buffer. For robust constructs, use mechanical homogenization (e.g., rotor-stator) for 30-60 seconds.

- Phase Separation: Add 200μL chloroform, vortex vigorously for 15 seconds, and incubate on ice for 5 minutes.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. Transfer the upper aqueous phase containing RNA to a new tube.

- Precipitation: Add equal volume of isopropanol, mix, and incubate at -20°C for 30 minutes. Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C.

- Wash: Discard supernatant, wash pellet with 75% ethanol, and centrifuge at 7,500 × g for 5 minutes.

- Resuspension: Air-dry pellet for 5-10 minutes and resuspend in 20-50μL nuclease-free water.

Quality Assessment:

- Assess purity using NanoDrop spectrophotometer (A260/A280 ratio of 1.9-2.1 indicates pure RNA)

- Verify integrity using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (RIN >8.0 recommended for sequencing applications)

- Confirm absence of DNA contamination by PCR of non-reverse transcribed RNA

Silica Column-Based DNA Isolation with Modifications

This protocol incorporates modifications to standard commercial kits to improve DNA yield from complex biomaterial constructs.

Reagents Required:

- Commercial silica-column DNA extraction kit

- Additional β-mercaptoethanol (0.1% final concentration)

- Proteinase K (20mg/mL stock)

- RNase A (10mg/mL stock)

Procedure:

- Lysis: Incubate cell-biomaterial construct in lysis buffer with 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol and 20μL proteinase K at 56°C for 1-3 hours with agitation.

- RNase Treatment: Add 5μL RNase A, mix, and incubate at room temperature for 5 minutes.

- Column Binding: Add equal volume of binding buffer, mix, and transfer to silica column. Centrifuge at 11,000 × g for 1 minute.

- Wash: Wash column twice with wash buffer, centrifuging at 11,000 × g for 1 minute after each wash.

- Elution: Elute DNA in 50-100μL elution buffer pre-heated to 65°C.

Quality Assessment:

- NanoDrop spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratio of 1.8-2.0)

- Agarose gel electrophoresis to confirm high molecular weight and absence of degradation

- PCR amplification of housekeeping genes to confirm amplifiability

Agarose Gel DNA Purification Protocol

Gel purification is essential for isolating specific DNA fragments after restriction digestion or PCR amplification, particularly for cloning applications in biomaterial research.

Reagents Required:

- Low-melt agarose (0.7-0.8%)

- TAE or TBE buffer

- DNA staining dye (SYBR Safe)

- QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit or equivalent

- Sterile razor blades or scalpels

Procedure:

- Gel Electrophoresis: Prepare 0.8% agarose gel in TAE buffer. Load samples with appropriate DNA ladder, leaving empty lanes between samples to prevent cross-contamination.

- Visualization and Excision: Visualize DNA bands using long-wavelength UV light to minimize damage. Excise target band with clean razor blade, minimizing excess gel.

- Gel Weighing: Weigh gel slice in microfuge tube to determine appropriate buffer volumes.

- DNA Purification: Follow manufacturer's instructions for gel extraction kit. Typically involves dissolving gel slice, binding DNA to column, washing, and eluting.

Critical Optimization Steps:

- Run gel at lower voltage (3-5V/cm) for crisper bands

- Limit UV exposure to less than 30 seconds to prevent DNA damage

- Use wide gel combs for increased sample capacity [40]

Quality Assessment and Validation Methods

Rigorous quality assessment is essential for nucleic acids intended for PCR and electrophoresis applications in cellular response research.

Table 3: Quality Metrics and Validation Methods for Isolated Nucleic Acids

| Quality Parameter | Assessment Method | Acceptance Criteria | Impact on Downstream Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration | NanoDrop spectrophotometry | DNA: >50ng/μL, RNA: >100ng/μL | Ensures sufficient template for detection |

| Purity (A260/A280) | NanoDrop spectrophotometry | DNA: 1.8-2.0, RNA: 1.9-2.1 | Indicates absence of protein contamination |

| Purity (A260/A230) | NanoDrop spectrophotometry | >2.0 for both DNA and RNA | Indicates absence of salt/solvent carryover |

| Structural Integrity | Agarose gel electrophoresis | Sharp, high molecular weight bands | Critical for long-amplicon PCR |

| RNA Integrity | Bioanalyzer/biochromatogram | RIN >8.0, 28S:18S >1.5 | Essential for RNA-seq and RT-qPCR |

| Amplifiability | PCR of housekeeping genes | Ct <30 in qPCR, clear bands in PCR | Confirms enzymatic compatibility |

| Functional Purity | Restriction digestion | Complete digestion pattern | Confirms absence of PCR inhibitors |

Validation studies demonstrate that performance metrics should aim for a geometric mean of absolute fold-differences (gmAFD) to ground truth of less than 1.25× for accurate quantification in molecular applications [41]. The quadratic mean of coefficients of variation (qmCV) for technical replicates should be below 5%, indicating high precision in measurement [41].

Workflow Integration for Cellular Response Research

The isolation of high-quality nucleic acids represents the critical first step in comprehensive analysis of cellular responses to biomaterials. The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated process from sample to analysis.

Nucleic Acid Isolation Workflow Integration

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Low Yield:

- Increase homogenization intensity and duration for robust constructs

- Extend proteinase K digestion time (up to overnight)

- Increase starting material volume

- Add carrier RNA during RNA precipitation

Poor Purity (Low A260/A280):

- Increase number of phenol:chloroform extractions

- Add additional wash steps in column-based protocols

- Ensure complete removal of organic solvents

- Use fresh preparation of β-mercaptoethanol

RNA Degradation:

- Maintain RNase-free conditions throughout procedure

- Keep samples on ice when not in processing

- Use fresh lysis buffer with guanidinium thiocyanate

- Process samples immediately or flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen

Inhibitors in Downstream Applications:

- Perform additional ethanol precipitation with 70% ethanol wash

- Dilute template in subsequent reactions

- Use additives such as BSA in PCR reactions

- Employ inhibitor removal columns