Optimizing 3D Bioprinting: A Comprehensive Guide to Processing High-Viscosity Biomaterial Inks

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed framework for optimizing the 3D printing of high-viscosity biomaterial inks.

Optimizing 3D Bioprinting: A Comprehensive Guide to Processing High-Viscosity Biomaterial Inks

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed framework for optimizing the 3D printing of high-viscosity biomaterial inks. Covering foundational principles, advanced methodologies, systematic troubleshooting, and validation techniques, it addresses the critical challenges of print fidelity, structural integrity, and biological functionality. By synthesizing current research and practical strategies, this guide aims to advance the fabrication of complex, cell-laden constructs for tissue engineering, disease modeling, and regenerative medicine applications.

Understanding High-Viscosity Bioinks: Rheology, Materials, and Printability Fundamentals

High-viscosity biomaterial inks are critical for fabricating self-supporting, structurally relevant constructs in 3D bioprinting. Within the context of process optimization, viscosity directly governs printability, shape fidelity, and cell viability. The following table summarizes the current quantitative benchmarks for classifying high-viscosity inks, based on recent extrusion-based printing studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Classification of Biomaterial Ink Viscosity

| Viscosity Range (Pa·s) | Shear Rate (s⁻¹) | Typical Material Examples | Primary Printing Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (< 10) | 1 - 100 | Alginate (low %), Collagen I, Fibrin | Lack of structural integrity, poor shape fidelity. |

| Medium (10 - 500) | 0.1 - 10 | GelMA (10-15%), Hyaluronic acid (modified) | Balance between extrusion force and cell compatibility. |

| High (> 500) | 0.01 - 1 | High-concentration Alginate (>5%), Silk fibroin, Collagen-Nanocellulose composites, PEG-based hydrogels (high MW) | High extrusion pressure, potential shear stress on cells, nozzle clogging. |

| Very High (> 1000) | < 0.1 | Dense microgel slurries, Shear-thinning granular gels | Requires specialized high-pressure printing systems. |

Note: Viscosity is a shear-dependent property. Values are approximate and measured at shear rates relevant to the printing process.

Application Notes: The Impact of High Viscosity on Print Parameters

Note 1: Printability and Shape Fidelity High-viscosity inks (> 500 Pa·s) exhibit superior shape fidelity due to reduced post-deposition spreading. The yield stress behavior is crucial; inks must flow under applied shear (in the nozzle) and immediately recover viscosity upon deposition. This is quantified by the Yield Stress and Storage/Loss Modulus (G'/G'') recovery kinetics.

Note 2: Cell Viability and Function While high viscosity can protect encapsulated cells from excessive deformation post-printing, the shear stress during extrusion is a major concern. Shear stress (τ) is related to viscosity (η) and shear rate (γ̇) by τ = η * γ̇. Optimal windows exist where viscosity is high at rest but drops sufficiently during extrusion to maintain cell viability > 90%.

Note 3: Structural and Mechanical Outcomes For printing load-bearing tissues (e.g., osteochondral grafts, tracheal splints), high-viscosity inks are prerequisites for achieving elastic moduli in the kPa to MPa range post-crosslinking. They allow for higher polymer content and better integration of reinforcing agents like nanoclays or fibers.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Rheological Characterization for Process Optimization

Objective: To measure the shear-thinning and viscoelastic recovery profile of a candidate high-viscosity biomaterial ink.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" (Section 5).

Methodology:

- Loading: Load approximately 500 µL of ink onto the Peltier plate of a cone-plate rheometer (e.g., 40 mm diameter, 1° cone).

- Flow Sweep Test:

- Set temperature to 25°C (or printing temperature).

- Perform a logarithmic shear rate sweep from 0.01 s⁻¹ to 100 s⁻¹.

- Record viscosity (η) as a function of shear rate (γ̇). Identify the zero-shear viscosity and shear-thinning region.

- Oscillatory Amplitude Sweep:

- At a fixed frequency (1 Hz), strain amplitude from 0.1% to 100%.

- Determine the linear viscoelastic region (LVR) and the yield point (where G' drops sharply).

- Three-Interval Thixotropy Test (3ITT):

- Interval 1 (Recovery): Low shear (0.1 s⁻¹) for 60s to establish structure.

- Interval 2 (Breakdown): High shear (10 s⁻¹) for 30s to simulate extrusion.

- Interval 3 (Recovery): Immediately return to low shear (0.1 s⁻¹) for 180s. Monitor G' recovery over time. Calculate recovery half-time (t₁/₂).

Protocol 2: Evaluating Extrusion Printability and Cell Viability

Objective: To correlate rheological data with printing performance and post-printing cell viability.

Methodology:

- Ink Preparation: Encapsulate human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) at 1x10⁶ cells/mL in the hydrogel precursor. Maintain sterile conditions.

- Printing: Use a pneumatic extrusion bioprinter. For a 27G nozzle (≈200 µm inner diameter):

- Systematically vary pneumatic pressure (P) from 15-60 psi.

- Maintain a constant print speed (V) of 10 mm/s.

- Print a 20-layer lattice structure (10x10 mm).

- Shape Fidelity Analysis:

- Capture top-down images post-printing.

- Measure filament diameter (Df) and compare to nozzle diameter (Dn). Calculate Fidelity Ratio = Df / Dn. Target is ~1.0.

- Quantify pore area consistency across layers.

- Cell Viability Assessment:

- Crosslink the printed construct per material requirements.

- At 1 hour and 24 hours post-print, incubate with live/dead assay (Calcein-AM/EthD-1) for 45 min.

- Image using confocal microscopy (z-stacks). Calculate viability as (Live cells / Total cells) * 100%.

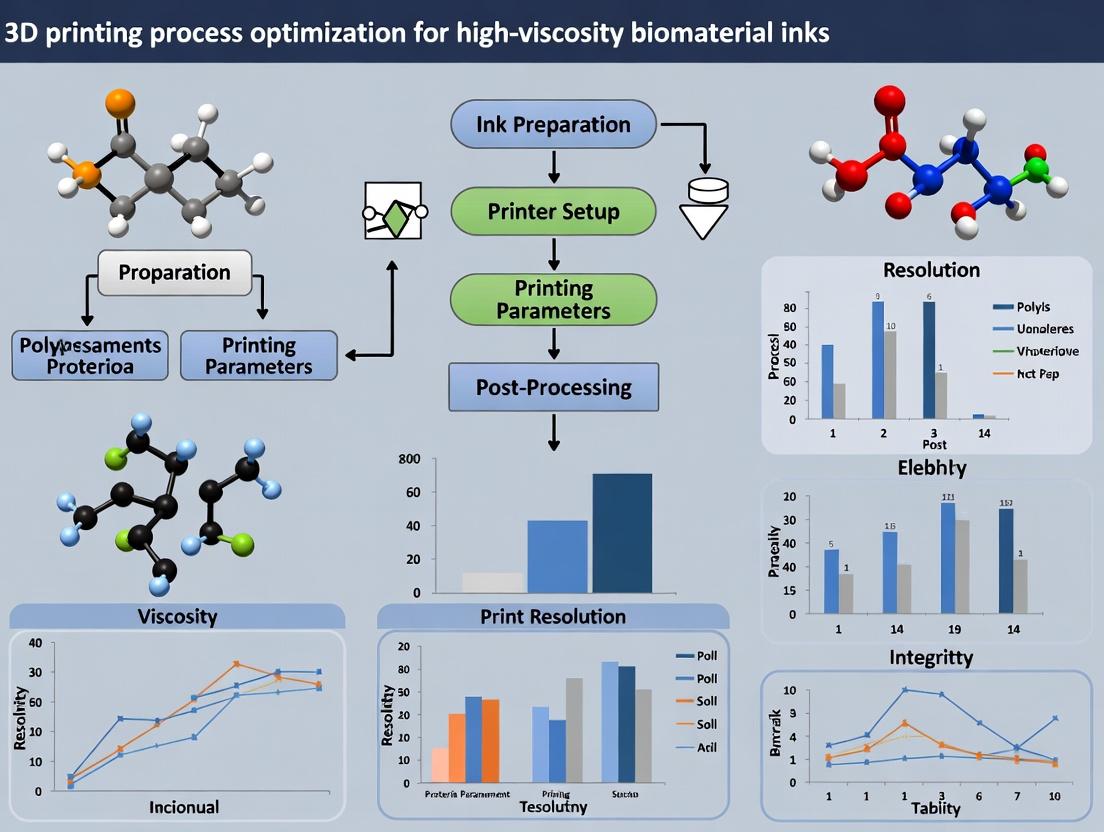

Visualizations

Diagram 1: High-Viscosity Ink Printability Decision Pathway

Diagram 2: Key Factors in High-Viscosity Bioink Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for High-Viscosity Bioink R&D

| Item | Function & Relevance to High-Viscosity Inks | Example Product/Chemical |

|---|---|---|

| Rheometer (Cone-Plate) | Essential for measuring absolute viscosity, yield stress, and viscoelastic recovery kinetics. Must handle high torque. | TA Instruments DHR, Anton Paar MCR series |

| Thixotropic/Rheology Modifiers | Additives that impart strong shear-thinning and rapid recovery. Critical for tuning printability. | Laponite nanoclay, Nanofibrillated cellulose, k-Carrageenan |

| High-Pressure Extrusion System | Bioprinter capable of delivering precise, repeatable pressures > 60 psi for extruding high-viscosity pastes. | Pneumatic or positive displacement (screw) systems. |

| Cell-Compatible Photoinitiator | For rapid crosslinking of light-curable (e.g., GelMA, PEGDA) high-viscosity inks post-extrusion to lock structure. | Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) |

| Viability/Cytotoxicity Assay | To quantify the impact of high shear stress during extrusion of cell-laden inks. | Live/Dead Assay (Calcein-AM / Ethidium Homodimer-1) |

| Mechanical Tester | To validate that printed high-viscosity constructs achieve target structural properties (compressive/tensile modulus). | Instron or Bose Electroforce systems with micro-load cells. |

Application Notes and Protocols

Within the broader thesis on 3D printing process optimization for high-viscosity biomaterial inks, precise characterization of rheological properties is paramount. These properties directly dictate extrudability, structural fidelity, and post-printing functionality. This document details critical rheological parameters, their impact on 3D printing, and standardized protocols for their measurement.

1. Rheological Properties: Significance and Quantitative Benchmarks

The following table summarizes the target rheological property ranges for printable high-viscosity biomaterial inks, based on current literature and empirical research.

Table 1: Target Rheological Properties for 3D Bioprinting Inks

| Property | Definition & Role in 3D Printing | Ideal Quantitative Range (General Guidance) | Consequence of Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shear-Thinning | Viscosity decreases with increasing shear rate. Enables extrusion through fine nozzles and rapid recovery after deposition. | Flow index (n) < 1, typically 0.2 - 0.6 from power-law model. High zero-shear viscosity (η₀ > 10 Pa·s). | n ~1: High extrusion pressure, cell damage. n too low: Ink too fluid, loss of shape. |

| Yield Stress | Minimum shear stress required to initiate flow. Prevents sagging and supports layer-by-layer deposition. | 50 - 500 Pa (dependent on nozzle size and layer height). | Too Low: Collapse of printed structure. Too High: Impossible extrusion, nozzle clogging. |

| Viscoelasticity | Combined solid-like (elastic) and liquid-like (viscous) behavior. Governs shape retention and response to deformation. | Loss tangent (tan δ = G''/G') < 1 at low freq. (0.1-1 Hz), indicating solid-dominant behavior at rest. | tan δ > 1: Ink flows excessively after printing. Very low tan δ: Brittle, poor layer fusion. |

| Recovery | Ability to regain elastic structure after cessation of shear. Critical for shape fidelity and multi-layer integrity. | Recovery (% of initial G') > 80% within 1-30 seconds post-shear. Thixotropic recovery time should match printing speed. | Slow Recovery: Layers merge, resolution lost. Fast Recovery: Poor interlayer adhesion. |

2. Experimental Protocols for Rheological Characterization

Protocol 2.1: Comprehensive Flow Sweep for Shear-Thinning and Yield Stress

- Objective: Quantify shear-thinning behavior and approximate yield stress.

- Equipment: Rotational rheometer with parallel plate (e.g., 25 mm diameter, 500 μm gap) or cone-and-plate geometry.

- Procedure:

- Load ink sample, trim excess, and equilibrate at 4°C or 37°C as relevant.

- Pre-shear at 1 s⁻¹ for 30s, then rest for 60s to erase history.

- Execute an upward logarithmic shear rate sweep from 0.01 to 1000 s⁻¹.

- Record viscosity (η) and shear stress (τ) as functions of shear rate (𝛾̇).

- Data Analysis:

- Fit the flow curve (τ vs. 𝛾̇) to the Herschel-Bulkley model: τ = τy + K * (𝛾̇)^n, where τy is yield stress, K is consistency index, and n is flow index.

- Zero-shear viscosity (η₀) can be estimated from the plateau at the lowest shear rates.

Protocol 2.2: Oscillatory Amplitude Sweep for Yield Stress and Linear Viscoelastic Region (LVER)

- Objective: Determine the yield stress (as a crossover point) and the maximum deformation the ink can withstand while behaving elastically.

- Equipment: Rotational rheometer with parallel plate geometry.

- Procedure:

- Load and equilibrate sample as in 2.1.

- At a fixed angular frequency (ω = 10 rad/s), perform a strain (γ) amplitude sweep from 0.01% to 1000%.

- Monitor storage modulus (G'), loss modulus (G''), and complex viscosity (η*).

- Data Analysis:

- Identify the strain at which G' = G'' (crossover point). The corresponding stress is often reported as the dynamic yield stress.

- The strain limit of the LVER (where G' is constant) defines the maximum safe handling deformation.

Protocol 2.3: Oscillatory Frequency Sweep for Viscoelastic Character

- Objective: Characterize the frequency-dependent viscoelastic moduli and assess ink stability.

- Equipment: Rotational rheometer with parallel plate geometry.

- Procedure:

- Load and equilibrate sample.

- Within the LVER (determined from 2.2, e.g., γ = 0.5%), perform a logarithmic frequency sweep from 100 to 0.1 rad/s.

- Record G' and G'' as functions of angular frequency (ω).

- Data Analysis:

- Evaluate the dominance of elastic (G' > G'') or viscous (G'' > G') behavior across frequencies relevant to printing (∼1-100 s⁻¹ equivalent).

- A predominantly frequency-independent G' > G'' indicates a stable, solid-like network at rest.

Protocol 2.4: Three-Interval Thixotropy Test (3ITT) for Recovery Kinetics

- Objective: Quantify the recovery of structure after a high-shear extrusion-simulating event.

- Equipment: Rotational rheometer with parallel plate geometry.

- Procedure:

- Interval 1 (Structure at Rest): Apply a small oscillatory strain within the LVER (γ = 0.5%, ω = 10 rad/s) for 60s. Record initial G'.

- Interval 2 (High-Shear Deformation): Apply a high constant shear rate (e.g., 100 s⁻¹) for 30s to mimic extrusion.

- Interval 3 (Recovery): Immediately return to the conditions of Interval 1. Monitor G' and G'' for 180-300s.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the % recovery of G' at specific time points (e.g., 30s, 180s): %Recovery = (G't / G'initial) * 100.

- Fit the recovery curve to a kinetic model (e.g., exponential) to quantify a recovery time constant.

3. The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Rheological Characterization of Biomaterial Inks

| Item / Reagent | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Herschel-Bulkley Model Fitting Software (e.g., Rheometer native software, MATLAB, Python SciPy) | To quantitatively extract yield stress (τ_y), consistency index (K), and flow index (n) from flow curves. |

| Hyaluronic Acid (High MW, >1 MDa) | A model shear-thinning polymer for tuning zero-shear viscosity and modulating recovery kinetics in hydrogel inks. |

| Nano-fibrillated Cellulose (NFC) or Laponite nanoclay | Additives to introduce a pronounced yield stress and enhance elastic modulus in composite inks. |

| PBS or Cell Culture Media (with/without serum) | Standard testing fluids to simulate physiological conditions and assess ink stability in biologically relevant environments. |

| UV- or Ionic-Crosslinking Agents (e.g., LAP photoinitiator, CaCl₂ solution) | To study the evolution of rheological properties during and after the chemical curing process post-deposition. |

| Temperature-Controlled Rheometry Cartridge | To maintain ink temperature (4°C for handling, 37°C for physiological) during testing, crucial for thermoresponsive materials. |

| Sandblasted or Roughened Parallel Plates | To prevent wall slip artifacts during testing of high-viscosity, gel-like materials. |

4. Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

The successful 3D bioprinting of functional tissues hinges on the optimization of process parameters for high-viscosity biomaterial inks. These inks must balance printability (extrudability, shape fidelity) with biocompatibility and post-printing functionality. This application note details five common high-viscosity biomaterials, providing quantitative data, protocols, and considerations for their integration into an optimized 3D bioprinting workflow.

Comparative Material Properties and Printability

Table 1: Key Properties of High-Viscosity Biomaterial Inks

| Biomaterial | Typical Viscosity Range (Pa·s) | Gelation/Curing Mechanism | Key Advantages for 3D Printing | Primary Optimization Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate | 0.1 - 10 (2-4% w/v) | Ionic crosslinking (e.g., Ca²⁺) | Rapid gelation, excellent shape fidelity, low cost | Low cell adhesion, degradation control, mechanical weakness. |

| Collagen | 10 - 100+ (3-5 mg/mL) | Thermally-induced (37°C) & pH-driven self-assembly | Native bioactivity, excellent cell compatibility | Low viscosity, slow gelation, poor mechanical strength. |

| Fibrin | 0.5 - 5 | Enzymatic (Thrombin + Fibrinogen) | Natural wound healing matrix, supports cell migration | Fast, uncontrollable polymerization, high shrinkage. |

| Silk Fibroin | 10 - 1000 (varies with conc.) | Solvent evaporation, shear-induced β-sheet formation | High tunable strength, slow degradation, versatile | Requires post-processing, residual solvent concerns. |

| dECM | 50 - 500+ | Thermally-induced (37°C) | Tissue-specific biochemical cues, bioactivity | High batch variability, complex viscosity control. |

Table 2: Representative Optimized 3D Printing Parameters

| Biomaterial (Typical Formulation) | Nozzle Gauge (G) | Pressure Range (kPa) | Print Speed (mm/s) | Bed Temperature (°C) | Post-Print Crosslinking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate (3% w/v, 1% CaSO₄ slurry) | 25-27 | 15-30 | 8-15 | 20-25 | Immersion in CaCl₂ bath |

| Collagen Type I (4 mg/mL, neutralized) | 22-25 | 20-40 | 5-10 | 4 (printhead), 37 (bed) | Incubation at 37°C, 30 min |

| Fibrinogen (40 mg/mL) + Thrombin | Dual-barrel or pre-mix | 10-25 | 10-20 | 20 | N/A (gels in situ) |

| Silk Fibroin (12-15% w/v aqueous) | 25-27 | 30-80 | 5-12 | 25 | Methanol treatment or humidity cycling |

| Heart dECM (30 mg/mL, pepsin-digested) | 21-23 | 40-100 | 3-8 | 15-20 (pre-cooled) | Incubation at 37°C, 1-2 hrs |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimization of Alginate Ink Rheology and Crosslinking for Shape Fidelity

Objective: To determine the ideal alginate concentration and ionic crosslinking protocol for maximizing structural integrity in extrusion-based printing.

- Ink Preparation: Prepare sodium alginate solutions at 1%, 2%, 3%, and 4% (w/v) in PBS or culture medium. Sterilize by filtration (0.22 µm).

- Rheological Characterization: Using a parallel-plate rheometer, perform a shear rate sweep (0.1 to 100 s⁻¹) to measure apparent viscosity. Perform oscillatory strain sweep to determine linear viscoelastic region (LVR) and gel point.

- Crosslinker Preparation: Prepare 100 mM CaCl₂ solution. For slower gelation, prepare a 1% (w/v) CaSO₄ slurry.

- Printability Assessment:

- Load ink into a syringe barrel fitted to the bioprinter.

- Using a 25G nozzle, print a standard 20-layer lattice structure (e.g., 15x15 mm) onto a petri dish.

- For immersion crosslinking, print directly into a CaCl₂ bath.

- For diffusion crosslinking, print onto a dry substrate and mist with CaCl₂.

- Analysis: Quantify strand diameter, pore size fidelity, and maximum unsupported overhang angle. Measure compressive modulus after 1 hour of crosslinking.

Protocol 2: Preparation and Printing of Tissue-Specific dECM Inks

Objective: To create a printable, viscous ink from decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM) that retains biological activity.

- dECM Solubilization:

- Mince decellularized tissue (e.g., porcine heart, liver) and lyophilize.

- Mill into a fine powder.

- Digest powder in 1 mg/mL pepsin solution (0.01M HCl) at a concentration of 30 mg dECM/mL under constant stirring (4°C, 48-72 hrs).

- pH Neutralization and Viscosity Enhancement:

- Slowly add 1/10 volume of 10x PBS and 1/20 volume of 0.1M NaOH to bring pH to ~7.4 on ice.

- To increase viscosity for printing, concentrate the neutralized dECM pre-gel using centrifugal filtration units (e.g., 10 kDa MWCO) or incubate at 37°C until the viscosity reaches >50 Pa·s.

- Printing and Gelation:

- Load the cold, viscous dECM pre-gel into a pre-cooled (4°C) print cartridge.

- Print onto a pre-cooled stage (15°C) using a 21G nozzle and elevated pressure.

- Immediately transfer the printed construct to a 37°C, humidified incubator for 1-2 hours to induce thermal gelation.

Protocol 3: Assessing Cell Viability Post-Printing with High-Viscosity Inks

Objective: To evaluate the impact of high-viscosity extrusion printing parameters on encapsulated cell viability.

- Cell-Laden Ink Preparation: Mix a suspension of target cells (e.g., NIH/3T3 fibroblasts at 5x10⁶ cells/mL) with your biomaterial ink (e.g., collagen pre-gel, alginate) on ice. Ensure homogeneous distribution.

- Control Setup: Prepare identical inks with cells loaded into syringes but not printed (static control).

- Printing: Print a multi-layer construct (e.g., 10x10x2 mm) using optimized pressure and speed parameters from Table 2.

- Viability Assay (Live/Dead Staining):

- At time points 1, 24, and 72 hours post-printing, incubate constructs in PBS containing 2 µM Calcein AM and 4 µM Ethidium homodimer-1 for 45 minutes at 37°C.

- Image using confocal microscopy (z-stacks).

- Quantify viability: (Live cells / (Live+Dead cells)) * 100%. Compare to the static control.

Signaling Pathways in Biomaterial-Cell Interactions

Title: Cell Signaling Activation by ECM Biomaterials

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for High-Viscosity Biomaterial Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example Supplier/Product |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Alginate (High G-Content) | Provides high gel strength and controllable viscosity for ink formulation. | Pronova UP MVG (NovaMatrix) |

| Recombinant Type I Collagen | Consistent, pathogen-free source for reproducible collagen ink formulation. | Collagen I, High Concentration (Corning) |

| Fibrinogen from Human Plasma | Key component for creating fibrin-based bioinks that mimic clotting. | Fibrinogen, Lyophilized Powder (Sigma-Aldrich) |

| Aqueous Silk Fibroin Solution | Ready-to-use, purified silk solution for tuning mechanical properties. | Silk Solution (Ajinomoto) |

| Pepsin, Lyophilized Powder | Enzyme for solubilizing decellularized ECM tissues into a printable pre-gel. | Pepsin from Porcine Gastric Mucosa (Sigma-Aldrich) |

| Photo-initiator (LAP) | Enables UV crosslinking of modified polymers (e.g., methacrylated gelatin) for enhanced stability. | Lithium Phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (TCI) |

| Rheometer with Peltier Plate | Characterizes ink viscosity, yield stress, and gelation kinetics critical for printability. | DHR Series (TA Instruments) |

| Microcapillary Extrusion Nozzles | Precision nozzles for consistent filament deposition of high-viscosity inks. | Nordson EFD MicroTip nozzles |

| Temperature-Controlled Print Stage | Essential for printing thermosensitive materials like collagen and dECM. | HP Incubator Stage (CELLINK) |

| Live/Dead Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit | Standard assay for quantifying cell survival after the printing process. | LIVE/DEAD Kit for mammalian cells (Thermo Fisher) |

Biomaterial Processing and 3D Printing Workflow

Title: Optimization Workflow for Biomaterial 3D Printing

The optimization of 3D bioprinting processes for high-viscosity biomaterial inks is central to advancing regenerative medicine and tissue engineering. This thesis posits that successful printing outcomes are governed by a critical, interdependent triad—the Printability Triangle—comprising Viscosity, Resolution, and Cell Viability. High-viscosity inks offer superior structural fidelity but pose significant challenges in extrusion and can induce damaging shear stress on encapsulated cells. This Application Note provides detailed protocols and data for systematically navigating this triad, enabling researchers to formulate and print inks that balance architectural precision with robust biological function.

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Table 1: Printability Parameters for Common High-Viscosity Biomaterial Inks

| Biomaterial (Formulation) | Apparent Viscosity (Pa·s) @ 10 s⁻¹ Shear Rate | Optimal Printing Pressure (kPa) | Nozzle Diameter (µm) | Theoretical Filament Width (µm) | Post-printing Cell Viability (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate (6% w/v, 100 mM CaCl₂) | 350 ± 25 | 80 - 120 | 250 | 320 ± 15 | 85 ± 3 |

| GelMA (15% w/v, 0.5% LAP) | 220 ± 15 | 60 - 90 | 200 | 260 ± 20 | 92 ± 4 |

| Collagen I (8 mg/mL, pH 7.4) | 45 ± 10 | 20 - 40 | 150 | 200 ± 30 | 95 ± 2 |

| Silk Fibroin (20% w/v) | 500 ± 50 | 100 - 150 | 300 | 400 ± 25 | 75 ± 5 |

| Agarose-Cellulose (4%-2% w/v) | 280 ± 20 | 70 - 110 | 250 | 310 ± 18 | 80 ± 4 |

*Viability measured via LIVE/DEAD assay at 24 hours post-printing. Data synthesized from current literature (2023-2024).

Table 2: Shear Stress and Viability Correlation

| Shear Stress (kPa) Estimated at Nozzle Wall | Measured Cell Viability (%) Post-extrusion | Recommended Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| < 5 | > 90 | Standard printing |

| 5 - 15 | 70 - 90 | Optimize nozzle geometry (tapered) |

| 15 - 30 | 50 - 70 | Pre-incubate cells in cyto-protective agents (e.g., Rho kinase inhibitor) |

| > 30 | < 50 | Reformulate ink; consider core-shell printing |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Rheological Characterization for Printability Assessment Objective: Determine the shear-thinning behavior and yield stress of the biomaterial ink.

- Equipment: Rotational rheometer with parallel plate geometry (e.g., 25 mm diameter, 500 µm gap).

- Procedure: a. Load 500 µL of pre-gelled ink onto the Peltier plate at 20°C. b. Perform a steady-state flow sweep from 0.1 to 100 s⁻¹ shear rate. c. Record apparent viscosity (η) at 10 s⁻¹ (simulating extrusion shear) and 0.1 s⁻¹ (simulating post-deposition recovery). d. Perform an oscillatory amplitude sweep (0.1% to 1000% strain, 1 Hz) to determine the storage (G') and loss (G'') moduli and the yield point (where G' = G'').

- Success Criteria: For extrusion printing, ink should exhibit shear-thinning (η at 10 s⁻¹ < η at 0.1 s⁻¹) and a G' > G'' at low strain, indicating solid-like behavior post-deposition.

Protocol 2: Printability and Fidelity Test (Grid Structure Printing) Objective: Quantify printing resolution and filament uniformity.

- Materials: Bioprinter, sterile cartridges, conical nozzles (27G, 22G), crosslinking agent (if applicable).

- Procedure: a. Load 3 mL of bioink into a sterile cartridge. b. Print a 10 mm x 10 mm single-layer grid (line spacing = 2x target filament width) onto a Petri dish. c. Capture images using a stereo microscope immediately after printing. d. Analyze images with ImageJ: measure actual filament width (n=10 per print) and calculate the Line Width Accuracy (Target Width / Actual Width) and Line Uniformity (standard deviation of width).

- Success Criteria: Line Width Accuracy between 0.9-1.1 and Line Uniformity with < 10% coefficient of variation.

Protocol 3: Post-Printing Cell Viability Assessment Objective: Evaluate the impact of the printing process on encapsulated cells.

- Materials: LIVE/DEAD Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit (Thermo Fisher), confocal microscope.

- Procedure: a. Print a 3D construct (e.g., 10-layer cube) with cell-laden bioink (1-5 x 10^6 cells/mL). b. Incubate the construct in complete media at 37°C, 5% CO₂ for 24 hours. c. Prepare staining solution: 2 µM calcein AM and 4 µM ethidium homodimer-1 in PBS. d. Rinse construct with PBS, incubate in staining solution for 45 minutes in the dark. e. Image using confocal microscopy (ex/em: 488/515 nm for live; 528/617 nm for dead). f. Quantify viability from 3-5 random z-stacks using Cell Counter plugin in ImageJ.

- Success Criteria: Viability > 80% is typically acceptable for high-viscosity ink printing; < 70% indicates excessive process-induced stress.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example Product/Catalog # |

|---|---|---|

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | UV-crosslinkable, tunable mechanical properties, excellent cell compatibility | Advanced BioMatrix GelMA Kit |

| LAP Photoinitiator | Cytocompatible photoinitiator for rapid UV crosslinking of GelMA, PEGDA, etc. | Sigma-Aldrich, 900889 |

| Alginate, High G-content | Rapid ionic gelation with Ca²⁺, provides high viscosity and structural integrity | NovaMatrix Pronova SLG100 |

| Recombinant Human Collagen I | Native, biocompatible matrix for soft tissue models; requires pH/thermal gelation | Cellink Bioink Collagen I |

| Rho Kinase (ROCK) Inhibitor (Y-27632) | Pre-treatment reagent to enhance cell survival post-dissociation and shear stress | Tocris Bioscience, 1254 |

| Fluorescent Microbeads (10 µm) | Passive tracers for visualizing shear profile and flow dynamics within the nozzle | Spherotech, FP-3056-2 |

| PDMS-based Microfluidic Nozzles | Customizable, low-adhesion nozzles to reduce shear stress during extrusion | Designed in-house via soft lithography |

| Hyaluronic Acid (High MW) | Bioactive rheology modifier to enhance viscosity and shear-thinning without cytotoxicity | Lifecore Biomedical, HA-HP series |

Diagrams

Title: The Printability Triangle Interdependencies

Title: High-Viscosity Bioink Printability Workflow

Within the broader research on 3D printing process optimization for high-viscosity biomaterial inks, three critical, interdependent challenges dominate: nozzle clogging, shear-induced cell damage, and inadequate interlayer fusion. These phenomena are intrinsically linked to the rheological properties of the bioink and the extrusion parameters. Optimizing one parameter often exacerbates another, creating a complex optimization landscape. This application note provides current protocols and data to systematically address these challenges.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Nozzle Geometries and Their Impact on Key Challenges

| Nozzle Type/Parameter | Inner Diameter (µm) | Taper Angle (degrees) | Observed Clogging Frequency (Relative) | Avg. Shear Stress (kPa)* | Resultant Layer Fusion Quality (Score 1-5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Cylindrical | 250 | 180 (flat) | High | 12.5 | 2 (Weak, distinct seams) |

| Conical Tapered | 410 (exit) | 30 | Low | 8.2 | 4 (Good, uniform matrix) |

| Flow-Focusing Microfluidic | 200 | N/A | Very Low | 5.1 | 3 (Moderate) |

| Key Finding: Tapered nozzles significantly reduce clogging and shear stress, improving cell viability and allowing for higher print pressures that enhance layer fusion. |

*Shear stress calculated for 5% alginate/3% gelatin blend at 15 mm/s extrusion speed.

Table 2: Effect of Printing Parameters on Cell Viability and Layer Fusion

| Parameter | Value Set 1 | Value Set 2 | Value Set 3 | Measured Cell Viability (%) | Layer Fusion Strength (kPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extrusion Pressure (kPa) | 80 | 120 | 160 | 92, 85, 74 | 15, 28, 41 |

| Printing Speed (mm/s) | 5 | 10 | 15 | 90, 86, 79 | 32, 25, 18 |

| Nozzle Height (µm) | 100 | 150 | 200 | 88, 89, 87 | 40, 28, 15 |

| Optimization Insight: A high-pressure (160 kPa), low-speed (5 mm/s) regimen with a nozzle height close to layer height (100µm) maximizes fusion but compromises viability. Set 2 (120 kPa, 10 mm/s, 150µm) offers a viable compromise. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Rheological Tuning to Mitigate Clogging and Improve Fusion Objective: Modify bioink viscoelastic properties to reduce shear-thinning and promote self-healing for better layer bonding.

- Preparation: Prepare a base bioink (e.g., 3% w/v alginate, 5 mg/mL fibrinogen).

- Additive Screening: Split the bioink into aliquots. Supplement with:

- A: 0.5% w/v nano-clay (Laponite XLG).

- B: 1% w/v methylcellulose (4000 cP).

- C: 0.1% w/v polymeric surfactant (Pluronic F127).

- Analysis: Perform oscillatory amplitude and frequency sweeps on a rheometer. Identify formulations with a high storage modulus (G') recovery (>90%) after high shear.

- Validation: Perform extrusion tests using a tapered 22G nozzle. Clogging is scored, and printed grids are assessed for fusion via microscopy.

Protocol 3.2: Real-Time Shear Stress Estimation and Viability Assay Objective: Quantify the relationship between extrusion parameters, shear stress, and immediate cell viability.

- Bioink Preparation: Encapsulate human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) at 5x10^6 cells/mL in the optimized bioink from Protocol 3.1.

- Instrumented Printing: Use a pressure-assisted bioprinter equipped with an in-line pressure sensor upstream of the nozzle.

- Shear Stress Calculation: For a known nozzle geometry, calculate apparent wall shear stress (τw) using the formula: τw = (ΔP * D) / (4L), where ΔP is the pressure drop, D is the nozzle diameter, and L is the nozzle length.

- Viability Assessment: Collect extruded filament directly into a Live/Dead assay staining solution at 0, 30, and 60 minutes post-printing. Quantify viability using fluorescence microscopy and image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ).

Protocol 3.3: Quantitative Layer Fusion Testing via Tensile Lap Shear Objective: Measure the mechanical strength of the bond between successively printed layers.

- Sample Fabrication: Print a two-layer rectangular sample (20mm x 5mm) where the second layer is deposited directly atop the first with a defined time interval (e.g., 5, 15, 30 seconds).

- Crosslinking: Apply crosslinking agent (e.g., CaCl₂ for alginate) uniformly after the second layer is deposited.

- Mechanical Testing: Mount the sample on a tensile tester with a 10N load cell. Perform a lap shear test at a strain rate of 1 mm/min.

- Analysis: Record the peak force at failure. Calculate shear strength as peak force divided by the overlap area. Compare across different time intervals and bioink formulations.

Visualization of Interdependencies and Workflows

Diagram 1: The Interlinked Challenges in Bioprinting Optimization

Diagram 2: Integrated Experimental Workflow for Process Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Addressing Bioprinting Challenges

| Item | Category | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Laponite XLG | Rheology Modifier | Nanosilicate clay that imparts shear-thinning and self-healing properties, reducing clogging and improving layer fusion by rapid structural recovery. |

| GelMA (Methacrylated Gelatin) | Photocrosslinkable Bioink | Provides cell-adhesive motifs; allows for gentle extrusion followed by UV-mediated stabilization, decoupling printability from final mechanics. |

| Pluronic F127 | Surfactant/Support Bath | Reduces ink-wall friction to lower extrusion pressure and shear stress. Can also be used as a yield-stress support bath for printing low-viscosity inks. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) with GDL | Crosslinking Agent | Glucono-δ-lactone (GDL) creates a slow, uniform release of Ca²⁺ ions, enabling ionic crosslinking of alginate after deposition, improving fusion. |

| Microfluidic Tapered Nozzles | Hardware | Conically tapered nozzles (e.g., from 500µm to 200µm) streamline flow, minimizing shear stress peaks and particle aggregation that cause clogs. |

| In-line Pressure Sensor | Instrumentation | Enables real-time monitoring of extrusion pressure, allowing for dynamic adjustment and direct calculation of nozzle shear stress. |

Advanced Printing Techniques and Parameter Optimization for Demanding Bioinks

Within the broader thesis on 3D printing process optimization for high-viscosity biomaterial inks, the choice of extrusion mechanism is paramount. For viscous inks—such as those incorporating high-concentration alginate, collagen, silk fibroin, or nanocellulose—the extrusion system directly influences cell viability, printing fidelity, and structural integrity. Pressure-driven and piston-driven systems are the two dominant technologies, each with distinct advantages and limitations for demanding biofabrication applications.

Pressure-Driven Systems utilize an external air (or gas) pressure source to extrude ink from a disposable syringe barrel. They offer rapid pressure response, easy syringe interchangeability, and are less mechanically complex. However, they can suffer from compressibility effects with highly viscous materials, leading to lag and inconsistent start/stop extrusion, which is detrimental to layer-by-layer accuracy.

Piston-Driven Systems employ a solid piston or plunger, mechanically driven by a stepper or servo motor, to directly displace the ink. This provides precise volumetric control, direct force feedback, and is highly effective for very stiff, shear-thinning pastes. The drawbacks include potential seal friction, more challenging material changeover, and a typically slower maximum extrusion speed.

The optimal system is determined by the specific rheological properties of the ink and the required printing resolution and speed for tissue engineering scaffolds or drug screening models.

Quantitative Comparison & Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics of Extrusion Systems for Viscous Inks (> 1 kPa·s)

| Performance Parameter | Pressure-Driven System | Piston-Driven System | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max Extrusion Pressure (Typical) | 0 – 800 kPa | 0 – 2000 kPa | Pressure transducer / Load cell |

| Volumetric Precision (Error) | ± 5 – 15% (viscosity-dependent) | ± 1 – 5% | Gravimetric analysis of extrudate |

| Response Time (to setpoint) | 50 – 500 ms | 10 – 100 ms | Step-response test |

| Typical Viscosity Range (Optimal) | 1 – 500 Pa·s | 10 – 5000 Pa·s | Rheometry (steady shear) |

| Cell Viability Impact (Post-print) | Moderate decrease due to potential pressure fluctuations | High viability with steady, low-shear extrusion | Live/Dead assay (e.g., Calcein AM/EthD-1) |

| Filament Consistency (Diameter CV%) | 8 – 20% | 3 – 10% | Image analysis of printed filaments |

| System Lag (Start/Stop) | Significant (air compressibility) | Minimal (direct mechanical contact) | High-speed video analysis |

Table 2: Protocol-Dependent Outcomes for Alginate (4% w/v) / GelMA (10% w/v) Composite Ink

| Printing Parameter | Pressure-Driven Protocol | Piston-Driven Protocol | Resulting Scaffold Property |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extrusion Force | 350 ± 45 kPa | 25 ± 3 N | Measured via system sensors |

| Print Speed | 10 mm/s | 8 mm/s | Optimized for filament continuity |

| Nozzle Diameter | 410 µm (27G) | 410 µm (27G) | Fixed variable |

| Layer Height | 300 µm | 300 µm | Fixed variable |

| Post-print Swelling | 12.5 ± 3.1% | 8.2 ± 1.7% | Dimensional fidelity after crosslinking |

| Compressive Modulus (Day 1) | 45.2 ± 6.1 kPa | 52.8 ± 4.9 kPa | Mechanical testing (unconfined) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Rheological Profiling for System Selection

Aim: To determine the ink's shear-thinning behavior and yield stress, informing the choice of extrusion system.

- Sample Preparation: Load 1 mL of prepared biomaterial ink (e.g., 3% alginate with 5x10^6 cells/mL) into a parallel-plate rheometer (e.g., 25 mm plate, 500 µm gap).

- Flow Ramp Test: Perform a logarithmic shear rate sweep from 0.1 to 100 s^-1 at 25°C.

- Oscillatory Stress Sweep: Perform an oscillatory stress sweep (0.1-100 Pa) at 1 Hz to determine the apparent yield stress (G' = G'' crossover).

- Data Analysis: Fit shear stress vs. shear rate data to the Herschel-Bulkley model. Inks with a high yield stress (>50 Pa) and strong shear-thinning are better suited for piston-driven systems.

Protocol 2: Printing Fidelity Assessment

Aim: To quantify the accuracy and resolution of printed structures from each system.

- Design & Slicing: Design a 10-layer, 15mm x 15mm grid structure (strand spacing = 2x nozzle diameter). Slice with identical G-code for toolpath.

- System Calibration: For pressure systems: calibrate pressure vs. flow rate. For piston systems: calibrate motor steps per µL.

- Printing: Print the grid using the optimized parameters from Table 2. Use a sterile, temperature-controlled print bed (15°C for gelatin-based inks).

- Analysis: Capture top-down images with a calibrated microscope. Measure strand diameter at 10 points per strand and pore area. Calculate coefficients of variation (CV%).

Protocol 3: Post-Printing Cell Viability Assessment

Aim: To evaluate the impact of the extrusion process on encapsulated cell health.

- Bioprinting: Print a 3D construct using the chosen protocol and a cell-laden ink.

- Crosslinking & Culture: Gently crosslink (e.g., 5 min in 100mM CaCl2 for alginate) and transfer to culture medium. Incubate for 1 and 24 hours (37°C, 5% CO2).

- Staining: At each time point, incubate constructs in PBS containing 2 µM Calcein AM (live) and 4 µM Ethidium homodimer-1 (dead) for 45 minutes.

- Imaging & Quantification: Image using a confocal microscope (z-stack). Use ImageJ/Fiji to count live/dead cells in a minimum of three fields of view. Calculate viability percentage.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for High-Viscosity Bioprinting Research

| Item | Function & Relevance |

|---|---|

| High-Viscosity Bioink (e.g., GelMA, Alginate, Collagen I) | The core biomaterial; must exhibit shear-thinning and rapid recovery for shape fidelity post-extrusion. |

| Crosslinking Agent (e.g., CaCl2, UV Light, Genipin) | Induces hydrogel formation; choice affects gelation kinetics and final mechanical properties of the printed construct. |

| Sterile, Filtered Luer-Lock Syringes (3-30 mL) | Standardized reservoirs for ink; Luer-lock prevents disconnection under high pressure. |

| Blunt-Ended Dispensing Nozzles (Gauge 16G-30G) | Defines filament diameter; smaller gauges (higher G#) increase resolution but require higher extrusion pressure. |

| Rheometer (e.g., Rotational) | Critical for characterizing ink viscosity, yield stress, and viscoelastic moduli to inform printability. |

| Fluorescent Live/Dead Cell Viability Assay Kit | Standardized reagents for quantifying the cytocompatibility of the bioprinting process. |

| Matrigel or Fibrinogen | Can be blended with primary polymers to enhance cell adhesion and biological activity in the final construct. |

| PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline), Sterile | For ink dilution, rinsing, and as a biocompatible buffer during printing. |

Visualizations

Title: Bioprinting System Selection & Optimization Workflow

Title: Mechanism of Pressure vs Piston Extrusion

Within the broader research on 3D printing process optimization for high-viscosity biomaterial inks (e.g., alginate, chitosan, collagen, nanocellulose, and their composites), precise control of core extrusion parameters is paramount. These parameters directly determine filament formation, deposition fidelity, and ultimately, the structural and functional integrity of printed constructs for tissue engineering and drug delivery applications. This document provides application notes and standardized protocols for investigating and optimizing these critical variables.

Parameter Analysis and Quantitative Data

Nozzle Geometry

Nozzle geometry is a primary determinant of shear stress, resolution, and extrusion behavior. The table below summarizes key dimensions and their impacts.

Table 1: Nozzle Geometry Parameters and Effects on High-Viscosity Biomaterial Extrusion

| Parameter | Typical Range for Biomaterials | Effect on Print Outcome | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inner Diameter (D) | 100 µm - 840 µm | Smaller D increases resolution & shear stress; larger D reduces clogging risk. | Must exceed largest particle/fiber in ink (e.g., >10x for cell-laden inks). |

| Nozzle Length (L) | L/D ratio: 2 - 10 | Higher L/D increases shear history and pressure drop. | Tapered nozzles (e.g., conical) reduce effective L/D and pressure requirement. |

| Orifice Shape | Circular, Slit, Coaxial | Circular: standard; Slit: for sheet deposition; Coaxial: for core-shell or hollow fibers. | Coaxial nozzles enable simultaneous printing of multiple materials or sacrificial sheaths. |

| Material | Stainless steel, Teflon, Glass | Steel: high pressure, sterilizable; Teflon/Glass: reduced adhesion for sticky inks. | Surface energy and roughness affect wall slip and material adhesion. |

Pressure, Print Speed, and Temperature

The interplay between pressure, speed, and temperature governs the volumetric flow rate and material state during deposition.

Table 2: Interdependent Printing Parameters for Biomaterial Inks

| Parameter | Operational Range (Typical) | Measurement & Control | Relationship & Optimization Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extrusion Pressure (P) | 15 - 100+ psi (pneumatic) / 50-5000 kPa | In-line pressure transducer, regulator. | P must overcome ink yield stress and viscous drag. Must be tuned with speed to match flow rate. |

| Print Speed (V) | 1 - 30 mm/s | Stepper motor control, encoder feedback. | With fixed P, V determines line width. Too high: under-extrusion; too low: over-extrusion. |

| Printhead Temperature (T) | 4°C - 40°C (for many hydrogels) | Peltier module, PID controller, thermocouple. | Lower T increases viscosity; higher T can reduce viscosity for extrusion but may damage bioactivity. |

| Volumetric Flow Rate (Q) | Calculated: Q ≈ V * W * H (line) | Derived from P, V, and nozzle D. | Key Balance: Qextruded(P, T, nozzle) must equal Qdeposited(V, path geometry). |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determining the Stable Printing Window (Pressure vs. Speed Sweep)

Objective: To identify the combination of extrusion pressure and print speed that produces consistent, continuous filament deposition without under- or over-extrusion for a given biomaterial ink and nozzle.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" (Section 5).

Method:

- Setup: Install target nozzle (e.g., 27G, 410 µm). Load ink into syringe barrel, eliminate air bubbles, and mount onto bioprinter. Connect pressure line.

- Calibration: Set printhead temperature to desired value (e.g., 20°C). Allow 5 min for equilibration.

- Pressure-Speed Matrix: Design a print path of straight lines (e.g., 20 mm long).

- Print Iterations: For each pressure setpoint (e.g., 20, 25, 30, 35 kPa), print lines across a range of speeds (e.g., 5, 10, 15, 20 mm/s).

- In-line Monitoring: Record actual pressure via transducer (if available) during each print.

- Post-Print Analysis:

- Visual Inspection: Use stereomicroscope to assess filament continuity, bead uniformity, and presence of defects.

- Dimensional Analysis: Measure average filament diameter (W) and height (H) at three points per line using digital microscopy or profilometry.

- Calculate Ratio: Compute the Flow Rate Ratio (FRR) = Qextruded / Qdeposited.

- Qextruded: Empirically derived from mass of material extruded over time at set P.

- Qdeposited = V * W * H (assumes rectangular cross-section; adjust shape factor as needed).

- Optimal Window: The stable printing window is defined where FRR ≈ 1 ± 0.1, filament is continuous, and diameter matches theoretical value (≈ nozzle D).

Protocol: Assessing Shear-Thinning and Recovery via Nozzle Geometry

Objective: To evaluate the effect of nozzle L/D ratio on the apparent viscosity and shear recovery of a viscoelastic biomaterial ink.

Method:

- Nozzle Preparation: Use three nozzles with similar D (e.g., 410 µm) but different L/D ratios (e.g., 2, 5, 10).

- Rheological Correlation: Perform a controlled extrusion test using a rheometer equipped with a capillary die or using the bioprinter itself with an in-line pressure sensor.

- Extrusion Test: For each nozzle, extrude ink at a constant, low pressure (P1) for 60s, then immediately switch to a high pressure (P2) for 60s, then return to P1.

- Data Collection: Record the mass extruded over time (or velocity if direct drive) to calculate instantaneous flow rate.

- Analysis:

- Shear Thinning: Compare steady-state flow rates at P2 for different nozzles. Higher L/D increases shear duration, potentially leading to greater viscosity reduction.

- Recovery: Compare the flow rate at the final P1 phase to the initial P1 phase. A delay or failure to return indicates incomplete viscoelastic recovery, critical for shape fidelity.

Visualization of Relationships and Workflows

Title: Biomaterial Print Parameter Optimization Workflow

Title: Core Parameter Interdependence Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for High-Viscosity Biomaterial Printing Research

| Item | Function & Rationale | Example Product/Brand |

|---|---|---|

| Programmable Bioprinter | Provides precise independent control over pressure/piston, speed, and temperature. Essential for DOE. | Allevi 3, CELLINK BIO X, REGEMAT 3D EXP. |

| Modular Nozzle System | Allows rapid interchange of nozzles with different geometries (D, L/D, shape) for comparative studies. | Nordson EFD barrel tips, IMS threaded nozzles. |

| In-line Pressure Sensor | Measures real-time extrusion pressure, enabling feedback control and accurate rheological calculations. | Honeywell ASDX series, FESTO pressure sensors. |

| Temperature-Controlled Stage/Printhead | Maintains ink at defined temperature (often cool) to preserve viscosity and bioactivity during print. | Peltier-based chilling blocks, custom water-jackets. |

| High-Viscosity Biomaterial Inks | Test materials with defined rheology (yield stress, shear-thinning). | Alginate (4-8% w/v), Nanocellulose (1-4% w/v), Fibrin-based composites. |

| Rheometer | Characterizes ink viscosity, yield stress, viscoelastic moduli (G', G''), and shear recovery pre-print. | TA Instruments DHR, Anton Paar MCR series. |

| Digital Microscopy/Profilometry | For post-print quantitative analysis of filament diameter, pore size, and layer height. | Keyence VHX series, Leica DVM6. |

Support Bath and Freeform Reversible Embedding (FRE) Printing for Unsupported Structures

This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for Support Bath and Freeform Reversible Embedding (FRE) printing techniques. These methodologies are critical components of a broader thesis on 3D printing process optimization for high-viscosity biomaterial inks. The focus is on enabling the fabrication of complex, unsupported structures—such as overhangs, branched vasculature, and porous scaffolds—which are essential for advanced tissue engineering and drug development applications. These techniques address the intrinsic limitations of direct extrusion printing with viscoelastic bioinks, which often lack the structural fidelity and shape retention necessary for unsupported features.

Foundational Mechanisms

- Support Bath Printing (SB): Utilizes a yield-stress fluid bath (e.g., microparticle gels, hydrogels) as a temporary, thermoreversible, or photo-reversible support medium. The print nozzle deposits ink within the bath, which flows around the extruded filament and immediately holds it in place via Bingham plastic behavior, enabling fixation of complex 3D paths.

- Freeform Reversible Embedding (FRE): Employs a granular gel (typically a Carbopol microgel) or a shear-thinning hydrogel as a solid-like yet fluidizable support bath. The key differentiator is the reversible fluidization of the support medium at the point of nozzle movement, allowing precise deposition without drag forces, followed by rapid re-solidification to embed and support the printed structure.

Quantitative Comparison of Techniques

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Support Bath and FRE Printing Techniques

| Parameter | Support Bath Printing (General) | Freeform Reversible Embedding (FRE) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Support Medium | Pluronic F127, Gelatin slurry, Agarose, Collagen | Carbopol (polyacrylic acid) microgel, Xanthan gum |

| Key Mechanism | Yield-stress support, Bingham plastic behavior | Reversible shear-thinning & rapid recovery |

| Typical Yield Stress (Pa) | 50 - 500 | 10 - 200 |

| Print Resolution (µm) | 200 - 1000 | 50 - 500 |

| Key Advantage | Excellent support for overhangs; biocompatible media available | Extremely low drag force; high precision for fine features |

| Primary Limitation | Bath viscosity can impede nozzle movement; ink diffusion | pH-sensitivity (Carbopol); post-print purification needed |

| Best Suited For | Large, soft tissue constructs; cell-laden structures | High-resolution, complex architectures; sacrificial printing |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Fabrication and Printing with a Carbopol-Based FRE Support Bath

Objective: To prepare a reversible granular hydrogel support bath and utilize it for printing unsupported structures with a high-viscosity biomaterial ink.

Materials & Equipment:

- Carbopol 940 (Polyacrylic acid)

- NaOH (1M) or NaHCO₃ solution for pH adjustment

- Deionized Water

- High-viscosity bioink (e.g., Alginate 5-8%, ECM-based hydrogels)

- Bioprinter with temperature-controlled stage (optional)

- Syringe barrels and luer-lock nozzles (18G-27G)

- pH meter

- Planetary centrifugal mixer

Methodology:

- Bath Preparation: Slowly disperse 0.5% (w/v) Carbopol 940 powder into deionized water under constant magnetic stirring to avoid clumping. Mix for 2 hours.

- Gelation: Gently add 1M NaOH or saturated NaHCO₃ solution dropwise to the dispersion until pH reaches ~7.0. The mixture will rapidly thicken into a clear gel.

- De-aeration: Transfer the gel to a centrifugal mixer and degas at 2000 rpm for 2-3 minutes to remove entrapped air bubbles, which can cause print defects.

- Bath Loading: Fill a clear printing reservoir (e.g., Petri dish) with the Carbopol gel. Smooth the surface with a flat spatula.

- Ink Loading: Load the high-viscosity bioink into a sterile syringe barrel. Attach the desired nozzle and mount onto the bioprinter.

- Printing Parameters: Submerge the nozzle tip 3-5 mm below the bath surface. The bath fluidizes locally via shear from the nozzle movement. Set print speed between 5-15 mm/s. Pressure or volumetric flow rate must be calibrated for the specific ink to ensure consistent filament diameter.

- Structure Recovery: After printing, carefully remove the entire support bath from the reservoir. Gently submerge the bath in a large volume of crosslinking solution (e.g., CaCl₂ for alginate) or cell culture medium. The Carbopol support will gradually dissolve, releasing the freestanding printed construct.

Protocol B: Printing in a Thermoreversible Pluronic F127 Support Bath

Objective: To use a thermoreversible support bath for printing cell-laden or sensitive biomaterials at low temperatures.

Materials & Equipment:

- Pluronic F127 powder

- Refrigerated bath or cold stage (4°C)

- Bioprinter with temperature-controlled stage/enclosure

- Bioink

Methodology:

- Bath Preparation: Dissolve 25-30% (w/v) Pluronic F127 in cold PBS or culture medium at 4°C with gentle agitation overnight. The solution will be liquid when cold.

- Print Setup: Pre-cool the print chamber and stage to 10-15°C. Pour the cold Pluronic solution into the print reservoir. It will transition to a rigid gel state at this temperature.

- Printing: Maintain the bath temperature below 15°C during printing. The gel provides rigid support. Deposit the bioink as per standard parameters.

- Recovery: Upon completion, lower the temperature of the entire reservoir to 4°C (e.g., by placing on a chilled plate). The Pluronic bath will liquefy, allowing gentle retrieval of the printed structure with a spatula or pipette.

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Workflow for Support Bath & FRE 3D Bioprinting

FRE Bath Rheology During Printing

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Support Bath & FRE Printing

| Item Name | Category | Primary Function | Key Consideration for Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbopol 940/980 | FRE Support Material | Forms a clear, shear-thinning microgel that reversibly fluidizes. | Concentration (0.3-1.5%) and neutralization pH control yield stress and recovery kinetics. |

| Pluronic F127 | Thermoresponsive Support | Liquid at low temp (4°C), forms rigid gel at 15-25°C, providing temporary support. | Concentration (20-30%) defines gelation temperature and modulus. Biocompatible but not cell-friendly long-term. |

| Gelatin Microparticle Slurry | Support Bath | Biocompatible, edible yield-stress fluid. Can be liquefied by heating to 37°C. | Particle size and concentration control support fidelity and removal ease. |

| Laponite XLG | Nanoclay Support | Forms a transparent, thixotropic gel. Can be ionically crosslinked. | Excellent for optical clarity but may interact with ionic bioinks. |

| High-Viscosity Alginate (≥5%) | Biomaterial Ink | Model high-viscosity bioink with rapid ionic crosslinking. Good shape retention. | Molecular weight and G/M ratio control viscosity and gelation speed. |

| Fibrinogen-Thrombin System | Biomaterial Ink | Enzymatically crosslinked ink for cell encapsulation and biological remodeling. | Crosslinking kinetics must be slower than deposition speed to avoid clogging. |

| PBS (10X), CaCl₂ (100mM) | Crosslinking/ Wash Solutions | For post-print ionic crosslinking of alginate and washing away support media. | Concentration and immersion time critical for structural integrity and cell viability. |

| Syringe Needles (Gauge 22-27) | Hardware | Nozzles for ink extrusion. Tapered tips reduce shear stress. | Smaller gauge = higher resolution but greater pressure required and potential cell damage. |

Multi-Material and Co-Axial Printing Strategies to Enhance Functionality.

Within the broader thesis on optimizing 3D printing processes for high-viscosity biomaterial inks, the integration of multi-material (MM) and coaxial printing is paramount for engineering advanced functional constructs. MM printing enables the spatial arrangement of distinct materials, while coaxial printing allows for the simultaneous deposition of multiple ink layers in a core-shell configuration. Combined, these strategies facilitate the creation of intricate architectures with graded mechanical properties, controlled release kinetics for therapeutics, and biomimetic tissue interfaces, directly addressing key challenges in drug development and regenerative medicine.

Application Notes and Current Research Data

Recent studies demonstrate the synergistic application of MM and coaxial strategies to create functionally enhanced constructs.

Table 1: Summary of Recent Applications in Bioprinting

| Primary Strategy | Materials Used (Core/Shell or Material A/B) | Target Functionality | Key Quantitative Outcome | Reference (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coaxial Printing | Alginate (Shell) / Fibrin-GelMA with cells (Core) | Enhanced cell viability & structure integrity | Cell viability >92% (Day 7) vs. <78% in bulk; Compressive modulus: 45 ± 5 kPa. | Lee et al. (2023) |

| Multi-Material | GelMA (Soft) / PEGDA (Hard) | Gradient mechanical properties | Elastic modulus gradient from 15 kPa to 1.2 MPa across a 10mm construct. | Smith et al. (2024) |

| Coaxial + MM | PCL (Structural) / Coaxial Alginate-GelMA (Bioactive) | Vascularized tissue constructs | Sustained VEGF release over 21 days; Capillary-like network formation in vitro by Day 14. | Zhao & Chen (2023) |

| Coaxial Printing | PLGA (Shell) / PEVK-Doxorubicin (Core) | Localized drug delivery | ~40% burst release in 24h, followed by zero-order release for 28 days; IC50 reduced 3-fold vs. free drug. | Patel et al. (2024) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Coaxial Printing of Core-Shell Bio-inks for Cell Encapsulation

Objective: To fabricate cell-laden filaments with a protective shell for enhanced viability and shape fidelity. Materials: Coaxial printhead (18G shell, 22G core), bioprinter with dual-temperature control, sterile alginate (4% w/v, high G), GelMA-Fibrinogen precursor (10% GelMA, 20 mg/mL Fibrinogen), 0.1M CaCl₂ crosslinking solution, LAP photoinitiator, cell suspension.

- Ink Preparation:

- Shell Ink: Filter sterilize sodium alginate solution. Load into syringe, maintain at 22°C.

- Core Ink: Mix GelMA, fibrinogen, 0.5% LAP, and cell suspension (e.g., fibroblasts, 5x10^6 cells/mL). Keep at 15°C to prevent premature gelation. Load into separate syringe.

- Printer Setup: Mount syringes on temperature-controlled holders. Connect to coaxial nozzle. Align print bed with 0.1M CaCl₂ bath.

- Printing Parameters: Set flow rates (Shell: 8 mL/h, Core: 4 mL/h). Print speed: 5 mm/s. Directly extrude filaments into CaCl₂ bath for immediate ionic crosslinking of alginate shell.

- Post-Processing: UV crosslink core (365 nm, 3 mW/cm², 60s). Transfer constructs to culture media. The CaCl₂ bath diffuses out, leaving a stable core-shell filament.

Protocol 3.2: Multi-Material Printing of Mechanical Gradient Constructs

Objective: To create a seamless gradient construct with spatially controlled stiffness. Materials: Multi-material capable extrusion printer (≥2 printheads), GelMA (5% and 15%), PEGDA (10%), LAP, digital model of gradient construct.

- Ink Formulation: Prepare three inks: Soft (5% GelMA, 0.25% LAP), Medium (15% GelMA, 0.25% LAP), Stiff (10% PEGDA, 0.5% LAP).

- Slicing and Toolpathing: Use advanced slicer (e.g., Simplify3D, custom G-code) to assign materials to specific regions. Design a linear gradient from 100% Soft to 100% Stiff over 10mm.

- Dynamic Switching Calibration: Calibrate printheads for identical nozzle height and deposition rate. Program purge/wipe sequence to prevent contamination during switching.

- Printing: Print onto a heated stage (20°C) in a humidity-controlled environment. Perform layer-by-layer UV crosslinking (405 nm, 2 mW/cm², 30s per layer).

- Final Cure: Post-print, globally crosslink with UV (405 nm, 10 mW/cm², 180s).

Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for High-Viscosity Biomaterial Ink Printing

| Item / Reagent | Supplier Examples | Critical Function in Process |

|---|---|---|

| Methacrylated Gelatin (GelMA) | Advanced BioMatrix, Allevi, Synthesized in-lab | Photo-crosslinkable hydrogel base providing cell-adhesive motifs. Key for MM and core bio-inks. |

| High-Guluronate Alginate | NovaMatrix, PRONOVA (FMC) | High-viscosity ionic-crosslinker. Ideal for shear-thinning shell ink in coaxial printing. |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) | Sigma-Aldrich, Laysan Bio | Bio-inert, tunable mechanical properties. Used in MM printing for creating stiff regions. |

| Lithium Phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | Sigma-Aldrich, TCI Chemicals | Efficient, cytocompatible photoinitiator for UV (365-405 nm) crosslinking. |

| Coaxial Nozzle Kits (18G/22G, 21G/25G) | Nordson EFD, SLA-solution, custom machined | Enables simultaneous deposition of core and shell materials. Critical for creating lumen or protective barriers. |

| Multi-Channel Pneumatic/Temperature-Controlled Extruder | CELLINK, Allevi, custom systems | Allows independent control of ≥2 high-viscosity inks, enabling complex MM printing. |

| Rheology Modifier (Nanocellulose, Silica) | University of Maine, Sigma-Aldrich | Enhances viscoelasticity and shape fidelity of bio-inks without affecting bioactivity. |

Application Notes

In the optimization of 3D printing processes for high-viscosity biomaterial inks, in-situ crosslinking is critical for stabilizing extruded filaments and complex 3D structures in real-time. Each strategy offers distinct advantages in gelation kinetics, cytocompatibility, and spatiotemporal control, directly impacting print fidelity, shape retention, and biological functionality.

Ionic Crosslinking: Ideal for rapid, mild stabilization of polysaccharide-based inks (e.g., alginate). It enables high cell viability but may exhibit poor long-term stability and mechanical strength.

Photo-crosslinking: Provides excellent spatiotemporal resolution and tunable mechanics via UV or visible light initiation. Essential for creating intricate, cell-laden structures, though photoinitiator cytotoxicity and light penetration depth are key considerations.

Thermal Crosslinking: Utilizes temperature-responsive polymers (e.g., gelatin, agarose, PNIPAAm) that gel upon cooling or heating. It's simple and often reversible, suitable for sacrificial molds or supporting baths.

Enzymatic Crosslinking: Offers high specificity and biocompatibility under physiological conditions (e.g., horseradish peroxidase, transglutaminase). It mimics natural crosslinking processes, ideal for sensitive cellular environments but can be costlier and slower.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of In-Situ Crosslinking Strategies for Biomaterial Inks

| Strategy | Typical Polymers/Inks | Crosslinking Agent/Trigger | Gelation Time | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic | Sodium alginate, Gellan gum | Divalent cations (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺) | Seconds to minutes | Rapid, mild, high cell viability | Weak mechanics, ion diffusion/leakage |

| Photo | GelMA, PEGDA, Hyaluronic acid methacrylate | Photoinitiator (LAP, Irgacure 2959) + UV/Vis light | < 60 seconds | Spatiotemporal control, tunable mechanics | Potential cytotoxicity, limited penetration depth |

| Thermal | Gelatin, Agarose, PNIPAAm, Pluronic F127 | Temperature change (cooling/heating) | Seconds to minutes | Simple, often reversible, no chemicals | Low structural stability at 37°C, limited polymer choice |

| Enzymatic | Tyramine-modified polymers, Fibrin, Gelatin | Enzyme (HRP+H₂O₂, Transglutaminase) | Minutes to hours | High specificity, biocompatible, physiological conditions | Slower kinetics, higher cost, potential immunogenicity |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics for High-Viscosity Bioink Formulations

| Bioink Formulation (w/v%) | Crosslinking Method | Post-Crosslinking Storage Modulus (kPa) | Gelation Time (s) | Reported Cell Viability (%) | Printability/Fidelity Score* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3% Alginate | Ionic (100mM CaCl₂) | 5 - 15 kPa | 30 - 120 s | >90% (Day 1) | Medium-High |

| 10% GelMA | Photo (0.1% LAP, 405 nm) | 10 - 50 kPa | 5 - 30 s | 80-90% (Day 7) | High |

| 15% Gelatin | Thermal (4°C to 25°C) | 1 - 5 kPa | 60 - 300 s | >95% (Day 1) | Low-Medium |

| 5% Tyramine-Hyaluronan | Enzymatic (HRP/H₂O₂) | 2 - 20 kPa | 60 - 600 s | >85% (Day 7) | Medium |

*Based on filament fusion, shape retention, and feature resolution in literature.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Ionic Crosslinking of Alginate for Coaxial Extrusion Printing

Objective: To stabilize a high-viscosity alginate core ink in-situ using a coaxial calcium chloride sheath flow.

- Ink Preparation: Dissolve sodium alginate (3-5% w/v) in deionized water or cell culture medium. Sterilize by autoclaving or filtration (0.22 µm). Add cells if required at 1-10 million cells/mL and mix gently.

- Crosslinking Solution: Prepare a sterile 50-200 mM CaCl₂ solution in DI water or buffer.

- Print Setup: Load alginate ink into the core syringe. Load CaCl₂ solution into the sheath syringe. Assemble coaxial nozzle (e.g., core diameter 22G, sheath diameter 18G).

- Printing Parameters: Set extrusion pressure (alginate: 15-30 kPa; CaCl₂: 10-20 kPa). Set print speed to 5-15 mm/s.

- In-Situ Stabilization: Initiate printing. The Ca²⁺ ions diffuse from the sheath into the core at the nozzle tip, causing immediate ionic gelation of the extruded filament.

- Post-Processing: Transfer printed structure to a 100 mM CaCl₂ bath for 5 minutes for complete crosslinking. Rinse with buffer before culture.

Protocol 2: Visible Light Photo-crosslinking of Cell-Laden GelMA Bioink

Objective: To achieve layer-by-layer stabilization of a printed GelMA construct using a integrated light source.

- Bioink Synthesis: Synthesize GelMA following standard methacrylation protocols. Dissolve lyophilized GelMA (5-15% w/v) in PBS at 37°C until clear.

- Photoinitiator Addition: Add Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) stock solution to achieve a final concentration of 0.05-0.25% w/v. Protect from light.

- Cell Incorporation: Suspend cells in medium, centrifuge, and resuspend in the GelMA-LAP solution at 4°C to achieve desired density. Keep on ice.

- Bioprinter Setup: Load bioink into a temperature-controlled (4-10°C) syringe. Equip printer with a 405 nm LED light source (5-20 mW/cm²) positioned at the print head.

- Printing & Crosslinking: Set print temperature to 15-25°C, pressure to 10-25 kPa. Define layer height (100-300 µm). Program the printer to expose each printed layer to light for 10-30 seconds immediately after deposition.

- Post-Print Curing: After final layer, expose entire construct to light for an additional 60-120 seconds for complete crosslinking. Transfer to culture media.

Protocol 3: Enzymatic Crosslinking of Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP)-Based Bioinks

Objective: To crosslink tyramine-conjugated polymer bioinks via an enzymatic reaction during extrusion.

- Polymer Solution Preparation: Prepare two separate sterile solutions:

- Solution A: Tyramine-modified hyaluronic acid (3-5% w/v) in PBS containing Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) at 0.1-1.0 U/mL.

- Solution B: The same polymer solution (3-5% w/v) in PBS containing Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) at 0.03-0.3% v/v.

- Keep both solutions on ice.

- Cell Preparation: If needed, pellet and divide cells equally. Resuspend one half in Solution A and the other in Solution B.

- Dual-Syringe/Mixing System: Load Solution A and Solution B into two separate syringes. Connect them via a "Y" connector or static mixer tip that blends the two components immediately before extrusion.

- Printing: Mount the syringe assembly or mixer onto the printer. Optimize pressure (15-30 kPa) and speed (5-10 mm/s). Gelation initiates upon mixing in the connector.

- Incubation: Allow the printed construct to incubate at 37°C in a humidified environment for 15-30 minutes for complete crosslinking before handling or transferring to media.

Visualizations

Title: Decision Workflow for Selecting a Bioink Crosslinking Strategy

Title: Mechanism of Visible Light-Induced Photo-Crosslinking

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for In-Situ Crosslinking Experiments

| Item & Example Product | Function in Crosslinking | Key Consideration for High-Viscosity Inks |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Alginate (e.g., NovaMatrix PRONOVA) | Ionic crosslinkable polymer backbone. | Viscosity and G/M ratio determine gel strength & printability. |

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Photo-crosslinkable, cell-adhesive polymer. | Degree of functionalization dictates crosslink density and mechanics. |

| Lithium Phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | Cytocompatible photoinitiator for UV/Vis light. | Concentration balances crosslinking speed vs. cytotoxicity. |

| Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP), Type VI | Enzyme for oxidative coupling of phenols (e.g., tyramine). | Activity (U/mg) must be consistent for reproducible gelation kinetics. |

| Calcium Chloride Dihydrate | Source of Ca²⁺ ions for ionic crosslinking of alginate. | Concentration and delivery method (bath, aerosol, coaxial) affect gel uniformity. |

| Transglutaminase (e.g., Microbial TG) | Enzyme forming ε-(γ-glutamyl)lysine bonds in proteins. | Used for gelatin/ fibrin inks; crosslinking is temperature & time-dependent. |

| N-Isopropylacrylamide (NIPAAm) Polymers | Thermo-responsive polymers that gel upon heating. | LCST can be tuned with co-monomers for specific gelation temperatures. |

| Static Mixing Nozzles (e.g., Fisnar tips) | For mixing multi-component inks (e.g., HRP/H₂O₂) just before extrusion. | Mixing efficiency is critical for homogeneous crosslinking in printed filaments. |

| Integrated LED Light Source (405/450 nm) | Provides precise, layer-by-layer photo-crosslinking during printing. | Intensity and exposure time must be optimized for each ink depth. |

Solving Common 3D Bioprinting Problems: A Systematic Guide to Process Refinement

Within the broader thesis on 3D printing process optimization for high-viscosity biomaterial inks, nozzle clogging emerges as a critical failure mode that compromises print fidelity, reproducibility, and material viability. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working with shear-thinning hydrogels, cell-laden bioinks, or polymeric suspensions, clogging is not merely a mechanical nuisance but a significant experimental variable. This document presents application notes and detailed protocols focusing on the pre-printing phases of material preparation and filtering to diagnose, mitigate, and prevent clogging at its source. Effective protocols here directly enhance extrusion consistency, cell viability in bioprinting, and the reliability of fabricating scaffolds for drug delivery systems.

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from current literature relevant to biomaterial ink preparation.

Table 1: Primary Contributors to Nozzle Clogging in Biomaterial Inks

| Contributor | Typical Size Range | Common Source in Bioinks | Impact Severity (Subjective) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Undissolved/Aggregated Polymer Clumps | 50 - 500 µm | Incomplete dissolution of alginate, collagen, HA | High |

| Particulate Contaminants | 1 - 100 µm | Impurities in raw powders, labware debris | Medium-High |

| Cross-linked Gel Precursors ("Micro-gels") | 10 - 200 µm | Premature ionic crosslinking (e.g., Ca²⁺ contamination in alginate) | Very High |

| Cell Aggregates | > 60 µm | Poor cell dispersion in carrier hydrogel | High (for small nozzles) |

| Air Bubbles | 100 - 1000 µm | Vortex mixing, loading technique | Medium (causes intermittent flow) |

Table 2: Efficacy of Common Filtering Methods for Clog Prevention

| Filtration Method | Typical Pore Size | Target Viscosity Range | Clog Reduction Efficacy* | Notes / Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syringe-Filter (Sterile) | 5 - 40 µm | Low-Medium (< 500 mPa·s) | 85-95% | Gold standard for sterilization; high pressure required for viscous inks. |

| Steriflip Vacuum Filtration | 20 - 70 µm | Low-Medium (< 1000 mPa·s) | 75-90% | Good for larger volumes; not suitable for very high viscosity. |

| Centrifugal Filters | 10 - 100 µm | Low-High (Broad) | 80-95% | Effective for de-bubbling and removing aggregates; speed/time critical. |

| Sequential Sieving (Mesh) | 37 - 200 µm | Medium-High (500 - 10,000 mPa·s) | 70-85% | Customizable for cell-laden inks; manual process may introduce bubbles. |

| Degassing (Centrifuge/Vacuum) | N/A (Bubble Removal) | All (esp. thixotropic) | 60-75% vs. bubble-clogs | Adjunct process; essential for pressure-driven extrusion systems. |

*Efficacy is an estimated percentage reduction in clogging events compared to unfiltered material, based on published print success rate data.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Comprehensive Biomaterial Ink Preparation and Filtration

Objective: To prepare a homogeneous, aggregate-free, high-viscosity biomaterial ink (e.g., 3% alginate with 1% methylcellulose) suitable for extrusion through nozzles down to 200 µm.

Materials: See Scientist's Toolkit Section 4. Procedure:

- Solution Preparation:

- Dissolve the methylcellulose in ¾ of the final volume of heated (80-90°C) sterile water or buffer under magnetic stirring (500 rpm) for 20 minutes.

- Cool the solution to 4°C for 1 hour to fully hydrate and clear.

- Separately, slowly sprinkle alginate powder into the remaining ¼ volume of room-temperature solvent under vigorous stirring (800-1000 rpm) for ≥2 hours. Use a scraper to dissociate wall clumps.

- Gradually combine the alginate solution with the cooled methylcellulose solution. Stir at 300-400 rpm at 4°C overnight (12-16 hours) for complete homogenization.

Primary Filtration (Aggregate Removal):

- Assemble a luer-lock syringe (30 mL) with a large-bore (e.g., 18G) blunt tip needle.

- Load the ink. Attach a sterile syringe filter (e.g., 40 µm nylon mesh) or place ink into a 50 mL conical tube for centrifugal filtration.

- For Syringe Filtration: Apply steady, firm pressure. If pressure exceeds 20 N (measure with force gauge), switch to a larger pore size (e.g., 70 µm) to avoid gel shear degradation. Discard first 1 mL.

- For Centrifugal Filtration: Use a 100 µm mesh insert. Centrifuge at 500 x g for 5 minutes at 10°C. Collect filtrate from the bottom chamber.

Degassing (Bubble Elimination):

- Transfer filtered ink to a 50 mL conical tube.

- Place in a vacuum desiccator for 15-20 minutes at 25 inHg. Alternatively, centrifuge at 2000 x g for 2-3 minutes.

- Let the ink rest at printing temperature (e.g., 20°C) for 30 minutes before loading.

Post-Filtration Viscosity & Homogeneity Check:

- Perform rotational rheometry (shear rate sweep 0.1-100 s⁻¹) to confirm viscosity profile matches unfiltered control within 10%.

- Image 10 µL droplets under phase-contrast microscopy (20x) to verify absence of particles > nozzle diameter / 3.

Protocol 3.2: Diagnostic Test for Clogging Propensity

Objective: To quantitatively assess the clogging risk of a prepared ink prior to lengthy bioprinting runs.

Materials: Pressure-driven extrusion system, calibrated force sensor, clean nozzles (various sizes), timer, balance. Procedure:

- Load 3 mL of prepared ink into a standard printing syringe. Ensure no bubbles.

- Equip a nozzle with diameter (D) representative of your target print (e.g., 410 µm, 250 µm).

- Program the extrusion system to apply a constant pressure (P) typical for your ink (e.g., 15 psi for alginate-based inks).

- Extrude ink for 30 seconds into a waste container. Weigh the extrudate (M_initial).

- Pause the extrusion for 120 seconds with the ink static in the nozzle tip to simulate a printing pause.

- Resume extrusion at the same pressure for 30 seconds. Weigh the extrudate (M_paused).

- Calculate the Clogging Index (CI):

- CI = [1 - (Mpaused / Minitial)] x 100%.

- A CI < 5% indicates excellent stability.