Navigating the Maze: Overcoming Standardization Challenges in Biomaterial Testing Protocols

This article addresses the critical standardization challenges confronting researchers and developers in the biomaterials field.

Navigating the Maze: Overcoming Standardization Challenges in Biomaterial Testing Protocols

Abstract

This article addresses the critical standardization challenges confronting researchers and developers in the biomaterials field. It explores the foundational international standards and regulatory frameworks governing biomaterial testing, examines methodological complexities in applying these standards to advanced materials, provides strategies for troubleshooting common optimization hurdles, and outlines robust validation and documentation requirements. Aimed at scientists, researchers, and drug development professionals, this comprehensive review synthesizes current practices, identifies persistent gaps between standardized protocols and innovative material systems, and discusses future directions for creating more predictive and efficient testing paradigms that can keep pace with technological advancement while ensuring patient safety and regulatory compliance.

The Regulatory Landscape: Core Standards and Evolving Frameworks for Biomaterial Testing

ISO 10993 and Its Critical Role in Biological Evaluation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core purpose of the ISO 10993 series for a researcher?

The ISO 10993 series provides a framework for the biological evaluation of medical devices within a risk management process [1] [2]. Its purpose is to ensure that a device is safe for its intended use by assessing the potential for adverse biological reactions—such as toxicity, irritation, or sensitization—resulting from contact between the device materials and the human body [3]. For researchers, it shifts the approach from a standardized checklist of tests to a science-based, risk-informed justification for the testing strategy [4] [3].

Q2: What are the "Big Three" biocompatibility tests and are they always required?

The "Big Three" tests are cytotoxicity, sensitization, and irritation assessments [5]. These are considered fundamental and are required for almost all medical devices, regardless of the device's category, nature of patient contact, or duration of use [5]. Cytotoxicity testing, for example, evaluates the potential for device materials to cause cell death or inhibit cell growth using in vitro methods [6] [5].

Q3: What is the difference between "extractables" and "leachables" in material characterization?

- Extractables: Chemical constituents that can be released from a material under controlled, exaggerated laboratory conditions (e.g., using strong solvents or high temperatures) [3].

- Leachables: Substances that are released from the device under normal clinical conditions of use and can come into contact with the patient [3].

The identification and quantification of these substances, as guided by ISO 10993-18, form the basis for a toxicological risk assessment and are critical for the biological safety evaluation [7] [3].

Q4: How has the concept of "foreseeable misuse" been integrated into the biological evaluation?

Recent updates to the standards require that the biological risk assessment considers how a device might be used outside its intended purpose [8] [9]. A key example is "use for longer than the period intended by the manufacturer, resulting in a longer duration of exposure" [8]. This means researchers must now consider systematic misuse scenarios, informed by post-market surveillance data or clinical literature, during the design of the biological evaluation plan [8].

Q5: My device is chemically equivalent to an existing device. Can I avoid new biological testing?

Demonstrating biological equivalence is a recognized pathway to reduce or avoid animal testing [7]. However, under regulations like the EU MDR, the requirements are strict. You must demonstrate not only that the devices have the same materials and intended use but also that they have "similar release characteristics of substances, including degradation products and leachables" [7]. This requires a comprehensive chemical characterization and a detailed justification for any differences, making biological equivalence one of the most challenging arguments to substantiate [7].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Inconsistent or Variable Cytotoxicity Results

- Problem: Cell cultures show variable levels of cell death (lysis) or morphological changes between test runs [6].

- Investigation Protocol:

- Review Sample Preparation: Confirm that the surface-area-to-volume ratio for extractions is consistent and follows ISO 10993-12 guidelines [5]. Slight variations can significantly alter the concentration of extractables.

- Verify Extraction Conditions: Ensure temperature and duration of extraction are rigorously controlled (e.g., 37°C for 24 hours) [6].

- Check Cell Culture Health: Use low-passage-number cells and confirm that control cultures are healthy and confluent. The use of antibiotics in the culture medium can prevent interference from microbial contamination on the test material [6].

- Solution: Standardize the entire workflow from sample preparation to cell seeding. Use well-defined positive and negative controls in every test run to validate the system's performance [6] [5].

Challenge 2: Justifying the Omission of a Standard Test (e.g., Sensitization)

- Problem: A researcher wants to justify that a sensitization test is not needed for their device.

- Investigation Protocol:

- Conduct a Thorough Chemical Characterization: Perform a complete extractables and leachables study per ISO 10993-18 [7] [4]. This is a prerequisite for a science-based justification.

- Perform a Toxicological Risk Assessment: A qualified toxicologist must evaluate all identified leachable substances against established thresholds (e.g., Dose-Based Threshold, DBT) for sensitization potential [10] [3].

- Leverage Existing Clinical Data: If the device is part of a family or has a well-established material with significant clinical history, this data can be used to support the justification, provided it specifically addresses the sensitization endpoint [10].

- Solution: Document the entire process in a Biological Evaluation Plan (BEP) and Report (BER). The justification must be based on analytical data and toxicological risk assessment, not merely on the fact that a material is "well-known" [4] [3].

Challenge 3: Determining the Correct Contact Duration for a Complex Device

- Problem: A device is intended for brief contact but is routinely used multiple times on the same patient. The correct duration category (limited, prolonged, long-term) is unclear.

- Investigation Protocol:

- Define the Exposure Scenario: Determine if the contact is "daily" or "intermittent" based on the standard's definitions. A "contact day" is any day in which contact occurs, irrespective of the length of time within that day [8].

- Calculate Total Exposure Period: For multiple exposures, the total exposure period is the number of calendar days from the first to the last use on a single patient [8].

- Consider Foreseeable Misuse: Evaluate if the device could reasonably be left in place or used for longer than stated in the instructions for use [8] [9].

- Solution: A device used intermittently over 10 days, even if each contact is brief, has a total exposure period of 10 days, placing it in the "prolonged" duration category (≥24 hours to 30 days) [8]. Justify the final categorization in the BEP.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and methods used in biocompatibility testing, as referenced in the ISO 10993 standards.

Table: Essential Reagents and Analytical Methods for Biocompatibility Testing

| Reagent / Method | Function in Biological Evaluation | Key Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Cultures (L929, Balb 3T3) | Used in in vitro cytotoxicity testing (ISO 10993-5) to assess cell viability and morphological damage [5]. | Mammalian fibroblast cell lines are standard. Culture health is critical for reproducible results [6]. |

| Extraction Media (Saline, Culture Medium, Vegetable Oil) | Simulate the elution of leachables from a device under different physiological conditions (polar, non-polar) [5] [3]. | The choice of media is critical and should reflect the nature of bodily fluids the device will contact [3]. |

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) | An analytical method for the identification and quantification of non-volatile extractables and leachables [3]. | Highly effective for characterizing a wide range of organic compounds released from device materials. |

| Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) | An analytical method for identifying and quantifying volatile and semi-volatile organic leachables [3]. | Complements LC-MS to provide a comprehensive profile of substances that can migrate from the device. |

| MTT / XTT Assay Kits | Colorimetric assays that measure cell metabolic activity as an indicator of cell viability and cytotoxicity [5]. | Provides quantitative data on cytotoxicity; a reduction in activity indicates compromised cell health. |

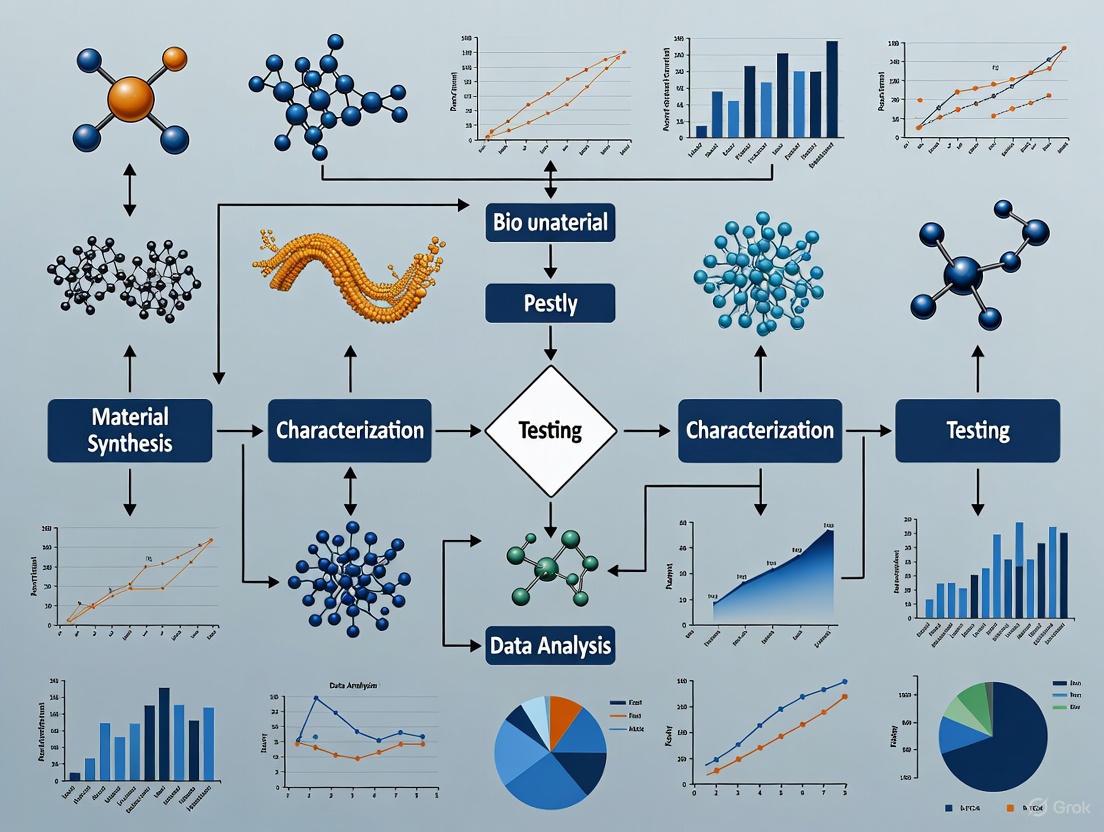

Experimental Workflow and Risk Assessment Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, risk-based biological evaluation process for a medical device as outlined in the ISO 10993 series, particularly the updated ISO 10993-1:2025.

Biological Evaluation Workflow

The updated standards embed the biological evaluation firmly within a risk management framework (aligning with ISO 14971) [8] [4]. This process is iterative, requiring re-evaluation if risks are deemed unacceptable or if new information (e.g., from post-market surveillance) becomes available [8].

The following diagram outlines the critical decision-making process for determining the necessary testing based on the device's contact nature and duration.

Testing Decision Tree

ASTM International Standards for Material-Specific Testing

ASTM International develops and publishes voluntary consensus technical standards that are critical for a wide range of materials, products, systems, and services [11]. For biomaterials, these standards provide essential specifications and test methods for evaluating the design, performance, and biocompatibility of medical devices, implants, and tissue-engineered medical products (TEMPs) [12]. Within the broader thesis on standardization challenges in biomaterial testing protocols, understanding and properly implementing these ASTM standards is fundamental to ensuring material safety, efficacy, and regulatory compliance while addressing inconsistencies in testing methodologies across research institutions and industries.

Standards by Material Category

ASTM International organizes its standards across multiple volumes, with Section 13 specifically dedicated to Medical Devices and Services [13]. The tables below summarize key ASTM standards relevant to different biomaterial categories.

Metallic Biomaterials Standards

Table 1: Selected ASTM Standards for Metallic Biomaterials

| Standard Number | Standard Title | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| F136-13(2021)e1 [14] | Specification for Wrought Titanium-6Aluminum-4Vanadium ELI (Extra Low Interstitial) Alloy for Surgical Implant Applications | Orthopedic and trauma implants |

| F138-13 [15] | Specification for Wrought 18Chromium-14Nickel-2.5Molybdenum Stainless Steel Alloy Bar and Wire for Surgical Implants | Corrosion-resistant surgical implants |

| F2063-18 [14] | Specification for Wrought Nickel-Titanium Shape Memory Alloys for Medical Devices and Surgical Implants | Devices utilizing shape memory effect |

| F1108-21 [14] | Specification for Titanium-6Aluminum-4Vanadium Alloy Castings for Surgical Implants | Cast orthopedic implants |

| F648-21 [14] | Specification for Ultra-High-Molecular-Weight Polyethylene Powder and Fabricated Form for Surgical Implants | Bearing surfaces in joint replacements |

Polymeric Biomaterials Standards

Table 2: Selected ASTM Standards for Polymeric Biomaterials

| Standard Number | Standard Title | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| F648-21 [14] | Specification for Ultra-High-Molecular-Weight Polyethylene Powder and Fabricated Form for Surgical Implants | Bearing surfaces in joint replacements |

| F997-18 [14] | Specification for Polycarbonate Resin for Medical Applications | Medical device components |

| F702-18 [14] | Specification for Polysulfone Resin for Medical Applications | Medical device components |

| F3333-20 [14] | Specification for Chopped Carbon Fiber Reinforced (CFR) Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) Polymers for Surgical Implant Applications | Load-bearing orthopedic implants |

Tissue-Engineered Medical Products (TEMPs) Standards

Table 3: Selected ASTM Standards for TEMPs and Biomaterials [16]

| Standard Number | Standard Title | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| F2150-19 [14] | Guide for Characterization and Testing of Biomaterial Scaffolds Used in Regenerative Medicine and TEMPs | Scaffold evaluation |

| F2212-25 [16] | Guide for Characterization of Type I Collagen as Starting Material for Surgical Implants and TEMPs | Collagen characterization |

| F2900-25 [16] | Guide for Characterization of Hydrogels Used in Regenerative Medicine | Hydrogel assessment |

| F3659-24 [16] | Guide for Bioinks Used in Bioprinting | Bioprinting materials |

| F2027-25 [16] | Guide for Characterization and Testing of Raw/Starting Materials for TEMPs | Raw material qualification |

| F2347-24 [16] | Guide for Characterization and Testing of Hyaluronan as Starting Materials | Hyaluronan-based products |

| F3368-19 [14] | Guide for Cell Potency Assays for Cell Therapy and Tissue Engineered Products | Cell functionality assessment |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Sample Preparation and Handling

FAQ: How should I prepare test samples for ASTM biocompatibility testing to ensure consistent and reproducible results?

Sample preparation is a critical first step detailed in standards like ISO 10993-12:2021, which is often referenced in ASTM-guided workflows [5]. Inconsistent extraction procedures are a primary source of inter-laboratory variability.

- Problem: Inconsistent cytotoxicity results between testing batches.

- Solution:

- Extraction Vehicle Selection: Use appropriate extraction vehicles as specified in the standard and relevant to your device's clinical use. Common vehicles include [5]:

- Physiological saline

- Vegetable oil

- Cell culture medium with serum

- Surface Area-to-Volume Ratio: Precisely calculate the surface area or weight of your sample and maintain the specified ratio with the extraction vehicle. Deviations can drastically alter leachable concentrations.

- Extraction Time and Temperature: Strictly adhere to the prescribed conditions (e.g., 24 ± 2 hours at 37 ± 1°C). Document any deviations as they can impact the profile of extracted chemicals.

- Aseptic Technique: For tests requiring sterility, ensure all preparation steps are performed under aseptic conditions to prevent microbial contamination that confounds results.

- Extraction Vehicle Selection: Use appropriate extraction vehicles as specified in the standard and relevant to your device's clinical use. Common vehicles include [5]:

Biocompatibility Testing

FAQ: Why are my in vitro cytotoxicity results (e.g., MTT assay) highly variable even with controlled sample preparation?

The "Big Three" biocompatibility tests—cytotoxicity, irritation, and sensitization—are required for nearly all medical devices [5]. Cytotoxicity testing, per ASTM F813 and ISO 10993-5, evaluates the material's potential to cause cell death or damage [12] [5].

- Problem: High variability in quantitative cell viability readings (e.g., MTT, XTT, Neutral Red Uptake).

- Solution:

- Cell Line and Passage Number: Use the recommended cell lines (e.g., L929 fibroblasts, Balb 3T3) and control the passage number. High-passage cells can lose sensitivity. Maintain consistent seeding density and confirm cell viability is >90% before starting the assay [5].

- Positive and Negative Controls: Always include concurrent controls. A negative control (e.g., high-density polyethylene) and a positive control (e.g., organotin-stabilized PVC) are essential for validating the test system's responsiveness [5].

- Assay Interference: Some materials can interfere with assay metrics. For example, materials that are themselves redox-active can interfere with MTT formazan production. Perform an interference check by incubating the material extract with the assay reagent in the absence of cells.

- Acceptance Criteria: While ISO 10993-5 does not define strict acceptance criteria, a cell viability of ≥70% is generally considered a positive sign, especially when testing neat extract. However, the final assessment must consider the device's nature and intended use [5].

Mechanical Testing

FAQ: My polymer scaffold's compressive modulus results show high standard deviation. How can I improve the reliability of my mechanical testing data?

Standards like ASTM D695 (compressive properties of rigid plastics) and ISO 604 provide frameworks, but methodological rigor is key [15].

- Problem: High standard deviation in compressive modulus measurements for porous polymer scaffolds.

- Solution:

- Specimen Geometry and Parallelism: Ensure test specimens have parallel end faces. Non-parallel surfaces induce uneven stress distribution. The height-to-diameter ratio should comply with the standard to prevent buckling.

- Hydration State: For biomaterials intended for hydrated use (in vivo), test them in their hydrated state. Mechanical properties of hydrogels and many polymers are highly dependent on water content. Control hydration time precisely.

- Crosshead Speed: The strain rate significantly influences the measured modulus. Strictly adhere to the crosshead speed specified in the standard (e.g., 1 mm/min for many polymers). Document any deviation.

- Preload: Apply a minimal, standardized preload to ensure full contact between the specimen and the platens before starting the test. This establishes a consistent "zero" point.

Experimental Protocols for Key Tests

Cytotoxicity Testing by Extraction (Based on ISO 10993-5 / ASTM F813)

Principle: This test assesses the cytotoxic potential of a biomaterial by exposing cultured mammalian cells to an extract of the material and evaluating cell damage and inhibition of cell growth [5].

Materials and Reagents:

- L929 fibroblast or Balb 3T3 cell line

- Appropriate cell culture medium (e.g., Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium with serum)

- Extraction vehicles: physiological saline, vegetable oil, culture medium without serum

- MTT reagent (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide)

- Solvent for formazan crystals (e.g., Isopropanol, DMSO)

- Multi-well plate reader (spectrophotometer)

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare the material extract per ISO 10993-12 using a surface area-to-volume ratio of 3 cm²/mL or 0.1 g/mL for irregular materials. Perform extraction at 37°C for 24 hours [5].

- Cell Culture: Grow L929 cells in complete medium to 80% confluence. Harvest and seed cells into 96-well plates at a density of 1 x 10â´ cells/well. Incubate for 24 hours to allow cell attachment.

- Exposure: Aspirate the culture medium from the wells. Add the material extract (neat or diluted) to the test wells. Include negative control wells (extraction vehicle alone) and positive control wells (e.g., latex or zinc diethyldithiocarbamate). Incubate the plates for 24 ± 2 hours at 37°C in a 5% CO₂ atmosphere [5].

- Viability Assessment (MTT Assay):

- After incubation, add MTT solution to each well.

- Incubate for 2-4 hours to allow formazan crystal formation.

- Carefully aspirate the medium and solubilize the formazan crystals with isopropanol.

- Measure the absorbance of each well at 570 nm using a plate reader [5].

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of cell viability relative to the negative control. Cell viability ≥70% is generally considered a positive indicator, but the result must be interpreted in the context of the device's intended use [5].

Compression Testing of Porous Polymer Scaffolds (Based on ASTM D695 / ISO 604)

Principle: This test determines the compressive properties of a rigid or semi-rigid plastic scaffold, which is critical for applications in load-bearing tissue engineering, such as bone regeneration.

Materials and Reagents:

- Universal Testing Machine (UTM) with compression platens

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) for hydration

- Calipers for dimensional measurement

Methodology:

- Specimen Preparation: Fabricate cylindrical specimens with a height-to-diameter ratio as specified in the standard (e.g., 2:1). Ensure the end faces are flat and parallel. Measure and record the exact dimensions of each specimen.

- Conditioning: For biomaterials intended for hydrated use, condition the specimens by immersing them in PBS at 37°C for 24 hours prior to testing to achieve equilibrium swelling.

- Test Setup: Mount the specimen centrally on the lower platen of the UTM. Ensure the specimen's long axis is aligned with the direction of the applied force. Lower the upper platen until it just makes contact with the specimen.

- Application of Preload: Apply a small preload (e.g., 0.05 N) to ensure full contact between the specimen and the platens. This point is defined as zero displacement.

- Testing: Compress the specimen at a constant crosshead speed (e.g., 1 mm/min for many polymers) until a predetermined strain or specimen failure is reached. Record the force and displacement data throughout the test.

- Data Analysis:

- Convert force-displacement data to stress-strain data.

- The compressive modulus is calculated as the slope of the initial linear portion of the stress-strain curve.

- Compressive strength is typically taken as the maximum stress sustained by the specimen before failure (or at a specific strain offset for materials that do not fail catastrophically).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Biomaterial Testing

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| L929 Fibroblast Cell Line [5] | In vitro cytotoxicity testing (ISO 10993-5) | Standardized cell model; control passage number to maintain sensitivity. |

| Balb 3T3 Cell Line [5] | In vitro cytotoxicity testing (ISO 10993-5) | An alternative fibroblast cell line; ensure mycoplasma-free status. |

| MTT/XTT Reagents [5] | Colorimetric assays for quantitative cell viability. | MTT requires solubilization; XTT is ready-to-use. Check for material interference. |

| High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) [5] | Negative control sample for biocompatibility tests. | Provides a baseline for non-cytotoxic response. |

| Zinc Diethyldithiocarbamate or Latex [5] | Positive control sample for biocomotoxicity tests. | Validates the responsiveness of the test system. |

| Cell Culture Media & Sera | Maintaining cell lines for in vitro assays. | Use consistent batches; serum-free options may be needed for specific extract tests. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Extraction vehicle and general washing buffer. | A polar extraction medium for hydrophilic compounds. |

| Vegetable Oil | Extraction vehicle (non-polar). | A non-polar extraction medium for lipophilic compounds. |

| Ultra-High-Molecular-Weight Polyethylene (UHMWPE) [14] | Reference material for wear and mechanical tests. | Well-characterized material for comparative studies (e.g., ASTM F648). |

| Type I Collagen [16] | Raw material for TEMPs and scaffold fabrication (e.g., ASTM F2212). | Source (bovine, porcine, recombinant) and purity are critical parameters. |

| HPH-15 | HPH-15, MF:C19H31N3S4, MW:429.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pth (1-44) (human) | Pth (1-44) (human), MF:C225H366N68O61S2, MW:5064 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The successful implementation of ASTM International standards for material-specific testing is paramount for overcoming standardization challenges in biomaterial research. By adhering to detailed protocols for sample preparation, biocompatibility assessment, and mechanical testing, researchers can generate reliable, reproducible, and comparable data. This technical support center provides foundational guidance for troubleshooting common experimental issues, thereby enhancing research quality and accelerating the development of safe and effective biomaterials for clinical applications.

FDA Guidance and Regional Regulatory Variations

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers navigate the complex landscape of biomaterials testing regulations, directly addressing common experimental challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the core biocompatibility tests required for most medical devices? The "Big Three" biocompatibility tests—cytotoxicity, irritation, and sensitization assessment—are standard requirements for nearly all medical devices regardless of category, patient contact, or duration of use [5]. These tests evaluate fundamental biological responses to ensure device safety. Cytotoxicity testing assesses whether materials cause harm to living cells, irritation testing evaluates localized inflammatory responses, and sensitization testing identifies potential allergic reactions [5]. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 10993 series provides detailed guidance on conducting these assessments within a risk management framework [17] [5].

Q2: How do FDA requirements align with international standards like ISO 10993? The FDA generally aligns with ISO 10993 standards but maintains specific interpretations and additional requirements [5]. While FDA recognizes many ISO 10993 standards, it doesn't fully recognize all parts and provides supplementary guidance documents [5]. For example, the FDA's recently issued draft guidance "Chemical Analysis for Biocompatibility Assessment of Medical Devices" expands on ISO 10993-18:2020 with more specific recommendations for chemical characterization [18]. Manufacturers must provide biocompatibility data that satisfies both ISO standards and FDA's specific interpretations for regulatory submissions [5].

Q3: What alternative methods to animal testing does the FDA accept? The FDA encourages alternative methods to animal testing, particularly through chemical characterization combined with toxicological risk assessment [18]. According to recent draft guidance, acceptable approaches include targeted analysis (quantifying expected constituents), non-targeted analysis (identifying unknown chemicals in device extracts), and simulated-use or leachables studies that refine exposure estimates [18]. This aligns with the principles of Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement (3Rs) mandated by Directive 2010/63/EU in the European Union [5].

Q4: What are the key differences in biomaterials regulations across major markets? Major regulatory regions maintain distinct frameworks with varying emphasis, though all reference ISO 10993 standards:

- United States (FDA): Requires premarket submissions with biocompatibility data based on ISO 10993 with specific modifications and interpretations [17] [5].

- European Union (MDR): Mandates CE marking under the Medical Device Regulation which references ISO 10993 standards, with oversight by notified bodies rather than national health authorities [17] [5].

- Japan (PMDA): Follows "Guidelines for Basic Biological Tests of Medical Materials and Devices" which resembles ISO 10993 but recommends modified tests and sample preparations [17].

- Canada (Health Canada): Aligns with international standards through Medical Devices Regulations but maintains country-specific requirements [5].

Q5: What are common pitfalls in chemical characterization for biocompatibility? The FDA identifies several methodological challenges in recent draft guidance: variability in testing methodologies across laboratories, inappropriate extraction conditions that underestimate tissue exposure, insufficient chemical identification, and inadequate data reporting [18]. To address these, FDA recommends specific quality assurance parameters like performing extractions in triplicate, choosing conditions that simulate worst-case scenarios, and implementing detailed workflows for identifying unknown extractables [18].

Regional Regulatory Variations Comparison

Table 1: Key Regional Regulatory Variations for Biomaterials Testing

| Region/Authority | Primary Regulation | Guidance Foundation | Notable Specific Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States (FDA) | Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act [17] | ISO 10993-1 with modifications [17] [5] | Detailed chemical characterization per draft guidance [18] |

| European Union | Medical Device Regulation (MDR) [5] | ISO 10993 series [5] | CE marking through notified bodies [17] |

| Japan (PMDA) | PMDA Regulations [5] | Modified ISO 10993 approach [17] | Different sample preparations and test modifications [17] |

| Canada (Health Canada) | Medical Devices Regulations [5] | ISO 10993 standards [5] | Country-specific submission requirements [5] |

| International | Various national regulations [5] | ISO 10993 series [5] | Lack of complete harmonization causes ambiguity [5] |

Table 2: Recent FDA Guidance Documents Relevant to Biomaterials (2024-2025)

| Guidance Topic | Status | Issue Date | Key Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Analysis for Biocompatibility Assessment of Medical Devices [19] | Draft | 09/19/2024 | Methodological approaches for chemical analysis [19] |

| Considerations for the Use of Artificial Intelligence | Draft | 01/07/2025 | AI support for regulatory decision-making [20] |

| Alternative Tools: Assessing Drug Manufacturing Facilities | Final | 09/12/2025 | CGMP for pharmaceutical quality [20] |

| Control of Nitrosamine Impurities in Human Drugs | Final | 09/05/2024 | Pharmaceutical quality and impurities [20] |

| Real-World Data: Assessing EHR and Claims Data | Final | 07/25/2024 | Supporting regulatory decisions with real-world evidence [20] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Biomaterials Testing

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Standard/Protocol Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Solvents (physiological saline, vegetable oil, DMSO, ethanol) [17] | Extract leachable components from test materials under standardized conditions [17] | ISO 10993-12:2021 [5] |

| Cell Cultures (Balb 3T3, L929, Vero cells) [5] | In vitro cytotoxicity testing using mammalian cell lines [5] | ISO 10993-5:2009 [5] |

| Viability Assays (MTT, XTT, Neutral Red Uptake) [5] | Quantitative measurement of cell survival and proliferation [5] | ISO 10993-5:2009 [5] |

| Reference Materials | Positive and negative controls for test validation [5] | ISO 10993-12:2021 [5] |

| Limulus Amebocyte Lysate | Detection of bacterial endotoxins/pyrogens [17] | Bacterial endotoxin testing [17] |

| Epi-cryptoacetalide | Epi-cryptoacetalide, MF:C18H22O3, MW:286.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Stearidonoyl glycine | Stearidonoyl glycine, MF:C20H31NO3, MW:333.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Cytotoxicity Testing (ISO 10993-5:2009)

Purpose: Assess whether medical device materials or extracts cause harm to living cells [5].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare extracts using physiological saline, vegetable oil, or cell culture medium as extraction solvents following ISO 10993-12:2021 [5]. Use surface area to volume ratios of 1.25-6 cm²/mL [17].

- Extraction Conditions: Conduct extraction at 37°C for 24 hours for cytotoxicity testing [17].

- Cell Culture Exposure: Expose cultured mammalian cells (Balb 3T3, L929, or Vero cell lines) to extracts for approximately 24 hours [5].

- Assessment Endpoints:

- Cell viability measured via MTT, XTT, or Neutral Red Uptake assays

- Morphological changes observed microscopically

- Cell detachment and lysis evaluation [5]

- Acceptance Criteria: While ISO 10993-5 doesn't define specific criteria, ≥70% cell viability (cell survival) is generally considered favorable, especially when testing neat extract [5].

Chemical Characterization (FDA Draft Guidance 2024)

Purpose: Identify and quantify chemical constituents in device extracts as an alternative to some biological testing [18].

Methodology:

- Information Gathering: Compose comprehensive device information including materials, manufacturing processes, and clinical use conditions [18].

- Test Article Selection: Use final, sterile finished devices representative of mass production [18].

- Extraction Studies:

- Perform extractions in triplicate for statistical significance

- Use exaggerated conditions to simulate worst-case scenarios

- Employ both polar and non-polar extraction media [18]

- Analytical Techniques:

- Targeted Analysis: Fully quantify expected constituents

- Non-Targeted Analysis: Identify and semi-quantify unknown extractables [18]

- Data Analysis and Reporting: Create comprehensive test reports with method summaries, protocol deviations, and detailed results with toxicological risk assessment [18].

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Biocompatibility Assessment Workflow

Global Regulatory Strategy Development

The Drive to Reduce Animal Testing and Develop Alternative Models

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs for New Approach Methodologies (NAMs)

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Q1: Our organ-on-a-chip model shows inconsistent barrier function across devices. What could be causing this variability?

A: Variability in microphysiological systems often stems from these key factors:

- Cell source and passage number: Primary cells beyond passage 5 may lose functionality, while iPSC-derived cells require rigorous differentiation quality control. Standardize using cells between passages 3-5 for consistent results.

- Microfluidic flow rates: Laminar flow must be maintained between 50-100 μL/min for most organ models. Calibrate pumps weekly and document shear stress calculations (typically 0.5-2 dyne/cm² for endothelial barriers).

- Extracellular matrix batch variability: Test each new Matrigel or collagen batch with a transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) validation assay before experimental use. Acceptable coefficient of variation should be <15% across three devices.

- Media composition: Growth factor concentrations can degrade; prepare fresh aliquots weekly and document lot numbers for all serum-free components.

Q2: Our in silico toxicity predictions don't align with traditional in vivo data. How should we resolve these discrepancies?

A: Discrepancies often reveal human-specific biological responses that animal models cannot capture. Follow this validation protocol:

- Confirm human biological relevance: Use the FDA's ISTAND program evaluation framework to determine if your model better predicts human responses [21]. The Emulate Liver-Chip, for instance, demonstrated 87% sensitivity and 100% specificity for drug-induced liver injury detection where animal models failed [21].

- Utilize the Integrated Chemical Environment (ICE): Compare predictions against the ICE database's curated human-relevant toxicity data [22].

- Implement orthogonal validation: Run parallel tests using two additional NAMs (e.g., high-throughput screening and 3D spheroid models) to build a weight-of-evidence approach [22].

Q3: We're encountering difficulties qualifying alternative methods under ISO 10993-1:2025. What documentation is essential?

A: The 2025 standard requires robust integration with risk management frameworks [8]. Essential documentation includes:

- Biological evaluation plan: Must now include "reasonably foreseeable misuse" scenarios and total exposure period calculations, not just intended use [8].

- Risk estimation rationale: Document severity and probability of biological harm using ISO 14971 methodology, including how chemical characterization data informs these assessments [8].

- NAMs validation evidence: Provide data comparing your method's performance against traditional endpoints with statistical analysis of sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility [8] [22].

Q4: How do we address regulatory concerns about novel biomaterials that lack animal testing data?

A: FDA's 2025 roadmap emphasizes a "totality-of-evidence" approach [23] [21]:

- Implement a tiered testing strategy: Begin with in chemico and in silico assessments, progress to increasingly complex in vitro models, and use animals only as a last resort [22].

- Leverage the FDA's ISTAND program: Qualify your Drug Development Tools through this pilot program, as demonstrated by the first Organ-on-a-Chip acceptance in September 2024 [21].

- Provide mechanistic data: Include transcriptomics, proteomics, and high-content imaging to demonstrate understanding of material-biological interactions at a molecular level [24].

Quantitative Comparison of Alternative Methods

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Validated Non-Animal Methods

| Method Type | Key Application | Validation Status | Throughput | Relative Cost | Regulatory Acceptance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organ-on-a-Chip | Drug-induced liver injury prediction | Peer-reviewed; 87% sensitivity, 100% specificity [21] | Medium | High | Accepted into FDA ISTAND program [21] |

| In silico (AI/ML) toxicity prediction | Predictive toxicology | OECD QSAR framework; >80% concordance for many endpoints [22] | High | Low | Accepted as part of weight-of-evidence |

| High-throughput screening | Chemical prioritization | Tox21 program; >10,000 chemicals tested [22] | Very High | Medium | Accepted for prioritization |

| 3D organoids | Disease modeling | Research use; characterizing heterogeneity [22] | Medium | Medium | Early-stage qualification |

| Human-based in vitro | Biocompatibility testing | ISO 10993-1:2025 aligned for specific endpoints [8] | Medium-High | Medium | Increasing acceptance |

Table 2: Regulatory Timeline for Alternative Methods Implementation

| Timeframe | Regulatory Developments | Impact on Testing Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Short-term (2025) | FDA roadmap implementation; ISO 10993-1:2025 adoption | Animal testing becomes "the exception rather than the rule"; increased acceptance of NAMs data in INDs [23] [8] |

| Mid-term (2026-2027) | Standards development for NAMs qualification; expanded ISTAND qualifications | Specific NAMs recognized as valid for particular contexts of use; reduced requirements for animal data [21] |

| Long-term (2028+) | Widespread adoption of qualified NAMs across regulatory agencies | Animal testing primarily for complex systemic effects not addressable by current NAMs [23] [22] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Alternative Methods

Protocol 1: Establishing a Multi-Organ Microphysiological System

Purpose: To create a connected liver-cardiac model for preclinical toxicity assessment.

Materials:

- Organ-on-a-chip platform with 2+ tissue chambers

- Primary human hepatocytes (commercial source, passage 2-4)

- iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (30+ days differentiated)

- Serum-free organ-specific media

- TEER measurement apparatus

- Analytical platform for metabolite analysis (LC-MS recommended)

Methodology:

- Device preparation: Coat liver chamber with collagen I (50μg/mL) and cardiac chamber with fibronectin (25μg/mL). Incubate at 37°C for 2 hours.

- Cell seeding: Seed hepatocytes at 5×10ⵠcells/cm² in liver chamber. Seed cardiomyocytes at 1×10ⶠcells/cm² in cardiac chamber. Maintain static conditions for 6 hours to facilitate attachment.

- System initiation: After cell attachment, initiate flow at 50μL/hour, gradually increasing to 100μL/hour over 48 hours.

- Functional validation: Measure albumin production (hepatocytes) and beat rate (cardiomyocytes) daily for 7 days to establish baseline functionality.

- Test compound exposure: Introduce compounds through the circulatory mimetic channel at clinically relevant concentrations. Include a minimum of n=6 chips per treatment group.

- Endpoint assessment: At 24, 48, and 72 hours post-exposure, measure:

- Metabolic activity (MTT assay)

- Tissue-specific function markers

- Histological changes

- Transcriptomic changes if applicable

Troubleshooting note: If one tissue shows premature failure, check for media compatibility—custom formulations may be necessary to support multiple tissue types.

Protocol 2: Computational Prediction of Biomaterial Biocompatibility

Purpose: To predict the biocompatibility of novel polymers using in silico methods.

Materials:

- Chemical structure of test material (SMILES format)

- Access to toxicity prediction software (OECD QSAR Toolbox, EPA TEST, or commercial platforms)

- Chemical properties database (PubChem, ChemIDplus)

- Historical biocompatibility data for similar structures

Methodology:

- Descriptor calculation: Compute physicochemical descriptors including logP, molecular weight, polar surface area, and H-bond donors/acceptors.

- Read-across analysis: Identify structurally similar compounds with existing toxicity data using the OECD QSAR Toolbox. Apply a similarity threshold of >70% for reliable prediction.

- Toxicity endpoint prediction: Run QSAR models for:

- Cytotoxicity (baseline toxicity prediction)

- Sensitization potential (protein binding models)

- Genotoxicity (structural alerts for DNA reactivity)

- Dose-response modeling: Estimate the probable concentration at which effects may occur using hierarchical clustering of historical dose-response data for analogous structures.

- Uncertainty quantification: Apply the Applicability Domain Index to determine prediction reliability. Reject predictions with ADI <0.7.

- Experimental design prioritization: Use computational results to focus in vitro testing on predicted endpoints of concern.

Validation: Compare predictions against limited in vitro testing (minimum 3 endpoints) to establish model accuracy for your specific chemical space.

Research Reagent Solutions for Alternative Methods

Table 3: Essential Materials for Implementing New Approach Methodologies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cells | Primary human hepatocytes, iPSC-derived cells, primary human keratinocytes | Provide human-relevant biological responses | Verify donor information, passage number, and functional validation data [22] |

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel, collagen I, fibrin, synthetic PEG-based hydrogels | Mimic tissue microenvironment | Test lot-to-lot variability; consider defined synthetic matrices for standardization [25] |

| Specialized Media | Organ-specific differentiation media, serum-free toxicity testing media | Support tissue-specific functions | Document all growth factors and supplements; check stability data [22] |

| Microphysiological Systems | Organ-on-a-chip platforms, 3D bioprinters, transwell systems | Provide physiological context with flow and tissue-tissue interfaces | Select systems with demonstrated reproducibility and available historical data [21] |

| Detection Assays | TEER electrodes, transepithelial electrical resistance; high-content imaging systems | Functional and structural assessment | Validate assays for 3D culture formats; establish baseline ranges [25] |

| Computational Tools | QSAR software, PBPK modeling platforms, AI/ML prediction tools | In silico prediction and data integration | Verify using known compounds before applying to novel materials [22] [24] |

Workflow Visualization

Gaps in Standards for Emerging Technologies (Nanomaterials, 3D-Printed Scaffolds)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key regulatory challenges for documenting novel nanomaterials? The regulatory landscape for nanomaterials is complex and varies significantly by region, creating a major challenge for standardization. In the European Union, REACH regulation has stringent, evolving reporting requirements for nanomaterials, including specific provisions for surface-treated nanomaterials [26]. Canada has expanded its mandatory reporting requirements with thresholds that differ from those for conventional chemicals [26]. The United States currently lacks nano-specific regulations, but regulatory bodies like OSHA are increasingly scrutinizing nanomaterial Safety Data Sheets (SDS) under existing frameworks like the Hazard Communication Standard [26]. This regulatory patchwork necessitates tailored documentation strategies for different markets.

Q2: Why do traditional Safety Data Sheet (SDS) templates fail for nanomaterials? Traditional SDS templates are inadequate because they do not capture the unique properties that govern nanomaterial behavior and toxicity. Key shortcomings include:

- Inadequate Hazard Identification: Traditional acute toxicity data may not reflect nano-specific respiratory hazards [26].

- Insufficient Composition Details: Standard templates lack fields for critical parameters like particle size distribution, surface area, shape, and surface chemistry [26].

- Generic Exposure Controls: Recommendations for standard fume hoods and gloves are often ineffective for controlling nanoparticle exposure [26].

Q3: What are the critical mechanical performance gaps in standardizing 3D-printed bone scaffolds? Standardization is challenged by the complex interplay between scaffold geometry, material composition, and processing parameters, all of which significantly influence mechanical performance [27]. For instance, studies on PLA+ scaffolds show that mechanical responses like displacement and strain vary dramatically with the lattice geometry (Gyroid, Diamond, Lidinoid) and wall thickness under the same compressive load [27]. This lack of a unified predictive model for how design choices affect mechanical outcomes is a major gap. Furthermore, balancing mechanical strength with necessary porosity for biological functions like cell migration and vascularization remains a significant challenge [28] [27].

Q4: Which 3D printing technologies are most relevant for bone scaffold fabrication, and how does the choice impact standardization? The choice of printing technology introduces variability that complicates standardization. The most common technologies include:

- Extrusion-Based Printing: Includes Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) for thermoplastics and Direct Ink Writing (DIW) for pastes/hydrogels. Fidelity in DIW heavily depends on the ink's viscoelastic properties [28].

- Laser-Based Printing: Includes Stereolithography (SLA) and Digital Light Processing (DLP), which use light to polymerize resins with high resolution [28]. Each technology has a distinct processing window, material compatibility, and impact on the final scaffold's structural fidelity, mechanical properties, and bioactivity, creating a barrier to establishing universal standards [28].

Q5: How can researchers address the lack of specific toxicological data for nanomaterials? A transparent "weight of evidence" approach is recommended. This involves:

- Building a Data Matrix: Systematically gathering all available data (e.g., from in vitro studies, read-across from similar materials) and explicitly identifying data gaps [26].

- Documenting Reasoning: Clearly stating the justification for hazard classifications and including statements in the SDS such as: "Limited toxicity data available specifically for this nanomaterial form" [26].

- Leveraging Consortia Data: Utilizing resources like the OECD Test Guidelines for nanomaterials and ECHA's appendices to inform assessments [26].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inconsistent Mechanical Performance in 3D-Printed Scaffolds

Issue: Printed scaffolds exhibit unexpected mechanical failure, excessive deformation, or high batch-to-batch variability.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution & Recommended Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal Geometric Configuration [27] | Analyze scaffold design using Finite Element Analysis (FEA) to identify stress concentration points. | Optimize architecture using computational modeling. Studies show Gyroid lattices often outperform Diamond and Lidinoid in mechanical integrity [27]. |

| Incorrect Printing Parameters for Material [28] | Review layer height, nozzle temperature, and printing speed against material supplier specifications. | Adopt a systematic experimental design like a Taguchi L27 Orthogonal Array to identify the optimal parameter set for mechanical performance [27]. |

| Uncontrolled Porosity and Pore Size [28] [27] | Characterize scaffold porosity and pore size using micro-CT scanning. | Design scaffolds with a controlled pore size range of 700–900 μm and ensure high interconnectivity to balance mechanical and biological needs [27]. |

| Inadequate Material Selection [28] | Evaluate the degradation profile and mechanical strength (e.g., compressive modulus) of the polymer. | Select advanced materials like PLA+ for enhanced toughness over standard PLA, or use polymer-ceramic composites to improve osteoconductivity and strength [28] [27]. |

Problem 2: Regulatory Compliance and Hazard Communication for Nanomaterials

Issue: Safety Data Sheets (SDS) for nanomaterials are rejected by regulators or customers for insufficient characterization.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution & Recommended Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Particle Characterization [26] | Audit Section 9 (Physical/Chemical Properties) of the SDS for missing nano-specific data. | Incorporate specific measurements: particle size distribution (e.g., D50), BET surface area, and detailed shape/morphology descriptions [26]. |

| Poorly Defined Exposure Controls [26] | Review exposure control plans for engineering controls and PPE specific to nanomaterials. | Specify "HEPA-filtered local exhaust ventilation" instead of "fume hoods" and detail effective glove types (e.g., "double nitrile, 0.18mm") [26]. |

| Inadequate Hazard Identification [26] | Check if GHS classification is based on data for the bulk material, not the nano-form. | Classify based on available nano-specific data. Use clear statements about data gaps and apply a conservative, evidence-based classification [26]. |

| Omitted Information on Composition [26] | Verify that all nanomaterials are listed with specific CAS numbers or detailed descriptions. | Disclose all nano-ingredients. Use precise descriptions like "titanium dioxide (anatase, silica-modified, 15-25 nm)" if a specific CAS is unavailable [26]. |

Data Presentation

| Lattice Geometry | Wall Thickness (mm) | Compressive Load (kN) | Displacement (mm) | Strain (×10â»Â²) | Notable Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lidinoid | 1.0 | 9 | 2.15 | 7.1 | Highest deformability |

| Diamond | 1.5 | 6 | 0.98 | 3.3 | Intermediate performance |

| Gyroid | 2.0 | 3 | 0.36 | 1.2 | Superior mechanical integrity, least deformation |

| Gyroid | 1.0 | 9 | 1.45 | 4.8 | Maintains relative strength at high load |

| Parameter Category | Specific Data Required | Example Entry for an SDS | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Size & Distribution | D50 value, range (e.g., 90% of particles between) | "D50 = 45 nm with 90% of particles between 30-65 nm" | Governs deposition, biological uptake, and toxicity. |

| Surface Area | BET surface area measurement | "BET Surface Area: 225 m²/g" | Critical for reactivity and dose-metric assessment. |

| Shape & Morphology | Descriptive morphology, aspect ratio | "High-aspect ratio needle-like structures" | Indicates potential asbestos-like pathogenicity. |

| Surface Chemistry | Description of coatings or modifications | "Surface-treated with silica" | Significantly alters biological interactions and toxicity. |

| Dispersion Stability | Stability behavior in relevant media | "Dispersion agglomerates in high ionic strength solutions" | Informs safe handling and risk under use conditions. |

Experimental Protocols

Objective: To systematically optimize the mechanical performance of 3D-printed bone scaffolds by evaluating geometric and loading parameters.

Methodology:

- Scaffold Design: Create three distinct Triply Periodic Minimal Surface (TPMS) lattice geometries (e.g., Lidinoid, Diamond, Gyroid) within a fixed design envelope (e.g., 30×30×30 mm³).

- Parameter Variation: Define varying wall thicknesses (e.g., 1.0, 1.5, 2.0 mm). Calculate the resulting porosity for each design.

- Experimental Design: Employ a Taguchi L27 Orthogonal Array to efficiently arrange the experiments (geometry × thickness × compressive load (e.g., 3, 6, 9 kN)).

- Mechanical Testing: Subject scaffolds to compression testing according to standards (e.g., ASTM). Record key responses: displacement and strain.

- Predictive Modeling: Train a Back-propagation Artificial Neural Network (BPANN) model using experimental data to predict scaffold behavior across a wider parameter space. Validate model accuracy (e.g., target R² > 0.99).

- Validation: Perform Finite Element Analysis (FEA) simulations to validate both experimental and BPANN-predicted results, creating a robust optimization framework.

Objective: To prepare a comprehensive and regulatory-compliant SDS for a nanomaterial, addressing its unique properties and potential hazards.

Methodology:

- Comprehensive Characterization: Prior to classification, fully characterize the nanomaterial's physical and chemical properties (see Table 2 for required data).

- Data Gap Analysis: Build a "data matrix" spreadsheet to inventory all available toxicological data (in vivo, in vitro) and explicitly identify data gaps.

- Hazard Classification: Use a "weight of evidence" approach. For data gaps, apply read-across from similar materials and expert judgment. Document all reasoning transparently.

- SDS Authoring - Critical Sections:

- Section 2: Hazard Identification: Clearly state data limitations. Emphasize respiratory hazards, which are common for nanomaterials.

- Section 3: Composition: List all nano-ingredients with specific CAS numbers or detailed descriptions, including concentration.

- Section 8: Exposure Controls: Specify "HEPA-filtered local exhaust ventilation" and test and specify PPE (e.g., glove type and thickness).

- Section 9: Physical Properties: Include all nano-specific parameters from Step 1.

- Section 11: Toxicological Information: Summarize all data, prioritize routes of exposure (e.g., inhalation), and contextualize in vitro vs. in vivo findings.

- Review and Documentation: Assemble a team (material scientist, toxicologist, safety engineer) to review the SDS. Maintain a separate file with all data sources and decision rationales.

Workflow Visualization

Experimental Protocol Development Workflow

Nanomaterial SDS Authoring Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Material/Reagent | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| PLA+ (Polylactic Acid Plus) | A primary thermoplastic polymer for extrusion printing; offers enhanced toughness and reduced brittleness compared to standard PLA, better mimicking bone mechanics [27]. |

| Bioactive Ceramics | Materials like hydroxyapatite or tricalcium phosphate; incorporated as fillers in polymer composites to provide osteoconductivity and improve compressive strength [28]. |

| Photocurable Resins | Used in laser-based printing (SLA/DLP) to create high-resolution scaffolds; often require post-processing for biocompatibility [28]. |

| Surface Modification Agents | Molecules (e.g., peptides, PEG) used to functionalize scaffold surfaces, improving cell adhesion, reducing immune rejection, or controlling degradation [28]. |

| Autotaxin-IN-7 | Autotaxin-IN-7, MF:C26H24N6O4, MW:484.5 g/mol |

| P162-0948 | P162-0948, MF:C20H15FN4O2, MW:362.4 g/mol |

| Resource/Platform | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| ECHA's Appendix for Nanoforms | Provides critical guidance for complying with the European Union's REACH regulation for nanomaterials, essential for market access in the EU [26]. |

| NIOSH Current Intelligence Bulletins | Offers authoritative, science-based recommended exposure limits (RELs) for specific nanomaterials (e.g., titanium dioxide), informing safe lab practices [26]. |

| OECD Test Guidelines | Provides internationally agreed-upon testing methods for the safety assessment of nanomaterials, ensuring data reliability and regulatory acceptance [26]. |

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Testing Protocols Across Material Classes

Test Selection Based on Contact Duration and Body Contact Type

This technical support guide provides a structured framework for selecting appropriate biocompatibility tests for medical devices and biomaterials, directly addressing key challenges in standardizing biomaterial testing protocols.

Biocompatibility Testing Framework

How are medical devices categorized for biocompatibility testing?

Device categorization is the first critical step and is based on the nature of body contact and contact duration [29] [30].

- Surface Devices: Contact body surfaces only.

- Intact Skin: Devices like electrodes, compression garments.

- Mucosal Membranes: Devices like endotracheal tubes, contact lenses.

- Breached or Compromised Surfaces: Devices like wound dressings on broken skin.

- External Communicating Devices: Contact internal tissues or body fluids via a external path.

- Blood Path, Indirect: Devices like administration sets, which contact blood indirectly.

- Tissue/Bone/Dentin: Devices like laparoscopic surgery tools or dental restoration materials.

- Circulating Blood: Devices like central venous catheters or blood oxygenators.

- Implant Devices: Placed entirely inside the body.

- Tissue/Bone: Devices like orthopedic implants or pacemakers.

- Blood: Devices like vascular grafts or heart valves [29].

How does contact duration influence test selection?

The duration a device contacts the body directly influences the extent of biological evaluation required. The three standardized categories are [29] [30]:

- Limited: ≤ 24 hours (e.g., hypodermic needles, single-use surgical instruments).

- Prolonged: >24 hours to 30 days (e.g., temporary indwelling catheters, some wound dressings).

- Long-term/Permanent: >30 days (e.g., joint replacements, permanent implants).

Test Selection Tables by Device Category

The following tables summarize the biological effects that must be evaluated based on your device's categorization and contact duration. These requirements are derived from the FDA's modified matrix based on ISO 10993-1 [29].

= Endpoint for consideration.

Surface Devices

| Biological Effect | Intact Skin | Mucosal Membrane | Breached/Compromised Surface |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limited Contact (≤24 hours) | |||

| Cytotoxicity | |||

| Sensitization | |||

| Irritation or Intracutaneous Reactivity | |||

| Acute Systemic Toxicity | |||

| Material-Mediated Pyrogenicity | |||

| Prolonged Contact (>24h to 30 days) | |||

| Subacute/Subchronic Toxicity | |||

| Implantation | |||

| Long-term/Permanent Contact (>30 days) | |||

| Genotoxicity | |||

| Chronic Toxicity | |||

| Carcinogenicity |

External Communicating Devices

| Biological Effect | Blood Path, Indirect | Tissue/Bone/Dentin | Circulating Blood |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limited Contact (≤24 hours) | |||

| Cytotoxicity | |||

| Sensitization | |||

| Irritation or Intracutaneous Reactivity | |||

| Acute Systemic Toxicity | |||

| Material-Mediated Pyrogenicity | |||

| Genotoxicity | * | ||

| Hemocompatibility | |||

| Prolonged Contact (>24h to 30 days) | |||

| Subacute/Subchronic Toxicity | |||

| Genotoxicity | |||

| Implantation | |||

| Hemocompatibility | |||

| Long-term/Permanent Contact (>30 days) | |||

| Genotoxicity | |||

| Implantation | |||

| Hemocompatibility | |||

| Chronic Toxicity | |||

| Carcinogenicity |

Note: *For all devices used in extracorporeal circuits [29].

Implant Devices

| Biological Effect | Tissue/Bone | Blood |

|---|---|---|

| Limited Contact (≤24 hours) | ||

| Cytotoxicity | ||

| Sensitization | ||

| Irritation or Intracutaneous Reactivity | ||

| Acute Systemic Toxicity | ||

| Material-Mediated Pyrogenicity | ||

| Genotoxicity | ||

| Implantation | ||

| Hemocompatibility | ||

| Prolonged Contact (>24h to 30 days) | ||

| Subacute/Subchronic Toxicity | ||

| Genotoxicity | ||

| Implantation | ||

| Hemocompatibility | ||

| Long-term/Permanent Contact (>30 days) | ||

| Genotoxicity | ||

| Implantation | ||

| Hemocompatibility | ||

| Chronic Toxicity | ||

| Carcinogenicity |

Troubleshooting FAQs

Our device is made of a common polymer. Do we still need to perform all tests listed in the matrix?

Not necessarily. The FDA provides a policy for devices contacting intact skin made from common materials (identified in Attachment G of its guidance) where you may provide specific information in your submission instead of a full biocompatibility evaluation [29] [31]. However, this is specific to intact skin devices. For all other device categories and materials, you must address every endpoint in the matrix, but not always with new testing. You can use existing data, chemical characterization, or a scientific rationale to justify why a test is not needed [29] [4]. If you use novel materials or manufacturing processes, additional testing is typically required [29].

We are testing a biodegradable material. Which additional factors must we consider?

For any device or material intended to degrade in the body, you must provide degradation information as part of your biological evaluation [29]. This includes identifying and quantifying the degradation products (leachables) and assessing their biological safety (e.g., cytotoxicity, systemic toxicity, genotoxicity). Understanding the full degradation profile is critical, as some byproducts may have toxicological effects not evident from testing the parent material [32].

Why is there variability in cytotoxicity results between different labs testing the same material?

A core standardization challenge in cytotoxicity testing lies in the choice of cell lines and protocols. Many labs use immortalized cell lines (e.g., L-929 mouse fibroblasts) which are tumor-derived and may not represent the behavior of primary human cells. Furthermore, results can be influenced by factors like [32]:

- Cell origin and type: Tumor-derived vs. primary cells.

- Culture conditions: Media composition and exposure time.

- Endpoint measurement: Qualitative (microscopic evaluation) vs. quantitative (e.g., MTT assay) methods. Adhering to standardized protocols like those in ISO 10993-5 and carefully documenting all methodological details is crucial for reproducibility [33] [34].

What are the key considerations for testing a device that contacts blood?

For blood-contacting devices (especially those contacting circulating blood), hemocompatibility testing is mandatory [29]. This involves a battery of tests to evaluate the device's interaction with blood, assessing the potential for [33] [34]:

- Thrombogenicity: Formation of blood clots.

- Hemolysis: Destruction of red blood cells.

- Platelet activation.

- Complement system activation. The specific tests required depend on the device's contact duration and the nature of blood contact (indirect vs. circulating) [29] [30].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Cytotoxicity Testing (ISO 10993-5)

Purpose: To evaluate the potential for device materials to cause cell death or inhibit cell growth.

Method Selection:

- Direct Contact Method: Ideal for low-density materials. A piece of the test material is placed directly onto a confluent layer of cells (e.g., L-929 fibroblasts) and incubated for 24-72 hours. Cytotoxicity is indicated by zones of malformed, degenerative, or lysed cells under and around the test sample [33].

- Agar Diffusion Method: Suitable for high-density materials. A thin layer of agar is placed over the cells. The test material or an extract dried on filter paper is placed on the agar surface. After incubation, a zone of cell lysis under the material indicates cytotoxicity [33].

- MEM Elution (Extract) Method: Uses extracts of the device prepared with various solvents (e.g., saline, serum) to simulate clinical use. The extracts are applied to the cell culture, and after incubation, cells are examined for effects. This method allows for semi-quantitative analysis [33].

- Quantitative MTT Assay: A colorimetric method that measures the reduction of a yellow tetrazolium salt by mitochondrial enzymes in living cells. The resulting purple formazan can be quantified spectrophotometrically. This method provides a numerical value for cell viability and is less subject to analyst interpretation [33].

Sensitization Testing (ISO 10993-10)

Purpose: To determine if device extracts contain chemicals that can cause allergic reactions after repeated or prolonged exposure.

Method Selection:

- Guinea Pig Maximization Test (GPMT): Considered the most sensitive. The test material extract is intradermally injected with Freund's Complete Adjuvant (an immune stimulant) during the induction phase. After a challenge exposure, the skin reaction is scored for redness and swelling (erythema and edema). Recommended for devices with internal or externally communicating contact [33].

- Closed Patch Test: Used for devices contacting only unbroken skin. The test material or extract is applied topically to the shaved skin of guinea pigs repeatedly during the induction phase, followed by a challenge dose. The skin sites are graded for allergic response [33].

- Murine Local Lymph Node Assay (LLNA): An alternative method that measures the proliferation of lymphocytes in the lymph nodes draining the application site. From an animal welfare perspective, the LLNA is often preferred as it reduces animal suffering and can provide quantitative data [33].

Genotoxicity Testing (ISO 10993-3)

Purpose: To assess the potential of device extracts to cause genetic damage (gene mutations, chromosomal aberrations).

Standard Battery: A battery of tests is required, typically including:

- Ames Test (Bacterial Reverse Mutation Assay): An in vitro test using specific strains of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli to detect point mutations. It is a required initial test for all devices with prolonged or permanent contact [33] [34].

- In vitro Mouse Lymphoma Assay or Chromosomal Aberration Test: These in vitro tests use mammalian cells to detect chromosomal damage (clastogenicity).

- In vivo Micronucleus Test: An in vivo test where animals (typically mice) are treated with the device extract, and the bone marrow or peripheral blood is examined for the presence of micronuclei (small, extranuclear bodies containing chromosomal fragments), which indicate chromosomal damage [33]. For devices with long-term exposure, an Ames test plus two in vivo methods are generally required [33].

Test Selection Workflow

This diagram outlines the logical decision process for selecting biocompatibility tests.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Biocompatibility Testing |

|---|---|

| L-929 Mouse Fibroblast Cell Line | A standard cell line used for in vitro cytotoxicity testing (e.g., MEM Elution, Agar Diffusion assays) [32]. |

| Salmonella typhimurium TA98, TA100, etc. | Specific bacterial strains used in the Ames Test for detecting reverse mutations and assessing genotoxic potential [33]. |

| Complete Freund's Adjuvant (CFA) | An immune stimulant used in the Guinea Pig Maximization Test to enhance the sensitization response for more reliable detection of weak allergens [33]. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) & Sodium Chloride | Common solvents used to prepare extracts of device materials for elution-based tests (cytotoxicity, sensitization, systemic toxicity) [33]. |

| MTT Reagent (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) | A yellow tetrazolium salt used in quantitative cytotoxicity assays. It is reduced to a purple formazan by metabolically active cells, providing a colorimetric measure of cell viability [33]. |

| Glp-Asn-Pro-AMC | Glp-Asn-Pro-AMC, MF:C24H27N5O7, MW:497.5 g/mol |

| 5-Methylnonanoyl-CoA | 5-Methylnonanoyl-CoA, MF:C31H54N7O17P3S, MW:921.8 g/mol |

A technical guide for researchers navigating standardization challenges in biomaterial testing.

This technical support center article addresses frequently asked questions and common experimental challenges related to the "Big Three" biocompatibility tests—cytotoxicity, sensitization, and irritation. These tests form the cornerstone of the biological safety evaluation for nearly all medical devices and are critical for regulatory approval globally [5].

FAQs: Core Concepts and Regulatory Context

Q1: What are the "Big Three" biocompatibility tests and why are they so critical?

The "Big Three" refers to the trio of cytotoxicity, irritation, and sensitization assessments. These tests are a standard requirement for almost every medical device entering the market, irrespective of its category, nature of patient contact, or duration of use [5]. They are the first line of defense in ensuring that a device material does not cause immediate cell death, skin irritation, or allergic reactions upon contact with the body.

Q2: How do international standards like ISO 10993 guide our testing protocols?

The ISO 10993 series of standards provides a globally harmonized framework for the biological evaluation of medical devices. Key standards include:

- ISO 10993-1: Provides an overarching framework for evaluation and testing within a risk management process [35] [8].

- ISO 10993-5: Specifies test methods and protocols for cytotoxicity testing [5].

- ISO 10993-10: Covers test methods for irritation and skin sensitization [5].

Other major regulatory bodies, including the US FDA and the European Union under its MDR, align their expectations with these ISO standards, though often with specific national deviations or additional guidance [5] [36].

Q3: Our device is made from "biocompatible" materials. Do we still need to perform this testing?

Yes, testing is likely still required. The FDA does not maintain a list of pre-approved "biocompatible materials" [35]. A material's safety is evaluated in the context of its specific intended use, patient contact duration, and the device's overall design. While data from predicate devices or supplier materials can reduce the testing burden, a comprehensive biological evaluation plan rooted in risk management is mandatory [35].

Q4: What is the single biggest standardization challenge in this field today?

The most significant challenge is the fragmented research landscape and significant variability in in vitro culture conditions and read-outs, which complicates cross-study comparisons [37]. This lack of standardized protocols is a major hurdle in adopting new approach methodologies (NAMs) and is a primary focus of ongoing research and standards development [5] [37].

Q5: How is the upcoming ISO 10993-1:2025 standard changing our approach?

The 2025 revision deeply embeds the biological evaluation process within a formal risk management framework, as defined in ISO 14971 [8]. Key changes include:

- Mandating the consideration of reasonably foreseeable misuse (e.g., using a device longer than intended) in the biological risk assessment.

- Providing more precise definitions for determining total exposure period, especially for devices with multiple or intermittent patient contact.

- Requiring an assessment of bioaccumulation potential for chemicals present in the device [8].

Troubleshooting Guides for Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Inconsistent Cytotoxicity Results

Problem: Variable results in cell viability assays (e.g., MTT, XTT) between test runs or laboratories.

Investigation & Resolution:

| Potential Cause | Investigation Steps | Recommended Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Extract Preparation Variability | Audit extraction parameters (solvent, temperature, duration, surface area-to-volume ratio) per ISO 10993-12. [5] | Standardize extraction protocols across all batches. Use controls with known reactivity. |

| Cell Line Instability | Check cell line authentication and passage number. Monitor mycoplasma contamination. | Use low-passage cells from a reputable source. Maintain consistent culture conditions. |

| Assay Interference | Test device extracts with assay reagents in a cell-free system. | Switch to an alternative assay (e.g., from MTT to Neutral Red Uptake if interference is confirmed). [5] |

Challenge 2: Non-Standardized FBGC Formation for Implantation Studies

Problem: Difficulty in reproducing in vitro foreign body giant cell (FBGC) formation, leading to poor predictive value for the in vivo foreign body response.

Investigation & Resolution:

- Root Cause: The research landscape is marked by significant variability in critical parameters, including cell origin and type, culture media and sera, fusion-inducing factors, and seeding density [37].

- Solution: While a universally accepted standard is not yet available, researchers are urged to adopt internal, rigorously documented protocols. A recent review proposes guidelines to improve reproducibility, focusing on standardizing the use of fusion-inducing factors like IL-4 and IL-13 and consistent quantification methods [37].

Challenge 3: Justifying Test Selection to Regulatory Bodies

Problem: Defending the choice, scope, or omission of certain "Big Three" tests during regulatory submission.

Investigation & Resolution:

- Proactive Planning: Develop a robust Biological Evaluation Plan (BEP) early in the device development process. The BEP should not just be a test checklist; it must be a risk-based rationale that considers the device's intended use, material chemistry, and clinical history [35] [8].

- Leverage All Data: Justify your testing strategy with a combination of data: chemical characterization, toxicological risk assessment, existing scientific literature, and clinical data from predicate devices [35]. Engage regulators in pre-submission discussions to align on your strategy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials used in standard in vitro "Big Three" testing.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for "Big Three" Biocompatibility Testing

| Item | Function in Testing | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| L929 or Balb/c 3T3 Fibroblasts | Standardized cell lines used for cytotoxicity testing. | Assess cell viability and morphological changes after exposure to device extracts. [5] |

| MTT / XTT Assay Kits | Colorimetric assays that measure cell metabolic activity as a marker of viability. | Common quantitative methods endorsed by ISO 10993-5. [5] |

| Neutral Red Dye | A vital dye taken up by living lysosomes; used in cytotoxicity testing. | An alternative endpoint for quantifying cell viability. [5] |

| Extraction Solvents | Vehicles to leach chemicals from a device for testing. | Typically include physiological saline, vegetable oil, and cell culture medium with serum. [5] |

| Recombinant IL-4 / IL-13 | Cytokines used to induce macrophage fusion into FBGCs in vitro. | Critical but variably applied reagents in non-standardized implantation simulation models. [37] |

| pGlu-Pro-Arg-MNA | pGlu-Pro-Arg-MNA, MF:C23H32N8O7, MW:532.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Avenanthramide D | Avenanthramide D, CAS:53901-55-6, MF:C16H13NO4, MW:283.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Cytotoxicity Testing Workflow

The following diagram outlines the core decision-making and experimental process for assessing cytotoxicity according to ISO 10993-5.

Key Signaling in Foreign Body Response

This diagram illustrates the core cellular process of Foreign Body Giant Cell (FBGC) formation, a key event in the reaction to implanted materials, highlighting areas of protocol variability.

Table: Acceptability Criteria for Common Cytotoxicity Assays (based on ISO 10993-5) [5]

| Assay Type | Measured Endpoint | General Acceptance Guideline | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MTT / XTT | Metabolic Activity (Cell Viability) | Typically ≥ 70% cell survival vs. control | A qualitative assessment of cell morphology is also required. |

| Neutral Red Uptake | Lysosomal Integrity & Viability | Typically ≥ 70% cell survival vs. control | Measures the ability of living cells to incorporate and bind the dye. |