Nanoparticle Biomaterials for Targeted Drug Delivery: Advances, Applications, and Future Therapeutics

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements in nanoparticle biomaterials for targeted drug delivery, a field poised to revolutionize pharmaceutical therapy.

Nanoparticle Biomaterials for Targeted Drug Delivery: Advances, Applications, and Future Therapeutics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements in nanoparticle biomaterials for targeted drug delivery, a field poised to revolutionize pharmaceutical therapy. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of nano-bio interactions and the unique properties of various biomaterial classes, including biopolymers, proteins, and metallic nanoparticles. It delves into methodological innovations in synthesis, functionalization, and the application of these systems in overcoming biological barriers for diseases such as cancer and neurological disorders. The content further addresses critical challenges in biocompatibility, scalability, and safety, evaluating modern troubleshooting techniques and preclinical validation models like organ-on-chip platforms. Finally, it offers a comparative analysis of material systems and discusses the translational pathway from laboratory research to clinical implementation, highlighting the future of personalized and programmable medicine.

The Foundation of Nano-Bio Interactions: Principles and Material Classes for Targeted Delivery

Within the context of targeted drug delivery research, nanoparticle biomaterials are engineered particles, typically ranging from 1 to 1000 nm, designed to interact with biological systems at a molecular level [1] [2]. These materials are defined by a core-shell structure where the core encapsulates the therapeutic agent, and the surface functionality dictates the particle's biological interactions and fate. The primary objective in designing these nanomaterials is to overcome the limitations of conventional drug delivery, including poor solubility, non-specific biodistribution, and rapid clearance, thereby enhancing drug bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy at the target site [3] [2]. The transition from a simple nanoparticle to a functional drug product requires an integrated formulation strategy that considers the final dosage form, a critical step in bridging the significant gap between laboratory research and clinical application [4].

Quantitative Definition of Key Properties

The behavior of nanoparticle biomaterials in a biological environment is governed by a set of definable and measurable physicochemical properties. The table below summarizes these critical parameters and their impact on biological fate.

Table 1: Defining Properties of Nanoparticle Biomaterials and Their Impact on Biological Fate

| Property | Defined Range & Characteristics | Direct Impact on Biological Fate |

|---|---|---|

| Size | 10–1000 nm [2]; <200 nm to cross biological barriers [3]; <10 nm susceptible to rapid renal clearance [1]. | Determines tissue penetration, cellular uptake, and circulation time. Smaller particles (<100 nm) penetrate tissues more effectively and avoid immune clearance [1]. |

| Surface Charge (Zeta Potential) | Positive, negative, or neutral. Cationic surfaces promote cellular uptake but increase toxicity and clearance; anionic/neutral surfaces prolong circulation [1]. | Governs electrostatic interaction with negatively charged cell membranes, protein adsorption (opsonization), and subsequent clearance by the Mononuclear Phagocyte System (MPS) [1]. |

| Surface Hydrophobicity | Ranges from hydrophilic to hydrophobic. Hydrophobic surfaces tend to aggregate and adsorb proteins [1]. | Drives protein adsorption, leading to opsonization and rapid MPS clearance. Hydrophilicity enhances dispersion and stability in blood [1]. |

| Surface Functionalization | Presence of functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl, carboxyl, amine) or coatings (e.g., PEG, chitosan, targeting ligands) [1]. | PEGylation creates a "stealth" effect, reducing protein adsorption and prolonging circulation [4] [1]. Targeting ligands (e.g., antibodies, peptides) enable active targeting to specific cells [1]. |

Experimental Protocols for Characterization

To ensure reproducible and effective nanoparticle biomaterials, standardized protocols for characterizing the key properties defined in Table 1 are essential. The following sections provide detailed methodologies.

Protocol for Nanoparticle Size and Zeta Potential Analysis

Method: Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) and Laser Doppler Micro-electrophoresis

Principle: DLS measures the Brownian motion of particles in suspension to determine their hydrodynamic diameter, while electrophoresis measures the velocity of particles under an applied electric field to calculate zeta potential.

Materials:

- Nanoparticle suspension

- Disposable zeta potential cuvettes and folded capillary cells

- DLS/Zeta Potential Analyzer (e.g., Malvern Zetasizer Nano series)

- Appropriate dispersant (e.g., distilled water, PBS)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the nanoparticle suspension with a clear, particle-free buffer to achieve a concentration that avoids inter-particle interference (typically recommended scattering intensity between 50-200 kcps).

- Equilibration: Allow the instrument and sample to thermally equilibrate to the set temperature (typically 25°C) for 2 minutes.

- Size Measurement:

- Transfer the diluted sample into a disposable sizing cuvette.

- Place the cuvette in the instrument and set the measurement parameters (material RI, dispersant RI, viscosity).

- Run the measurement for a minimum of 3 runs per sample.

- Record the Z-Average diameter (hydrodynamic size) and the Polydispersity Index (PDI) as a measure of size distribution width.

- Zeta Potential Measurement:

- Transfer the sample into a dedicated folded capillary zeta cell.

- Insert the cell into the instrument.

- Set the measurement parameters, including dispersant dielectric constant and Smoluchowski approximation.

- Perform a minimum of 3 runs and record the average zeta potential (in mV).

- Data Analysis: Report the Z-Average size and PDI. A PDI < 0.2 indicates a monodisperse sample. Report the mean zeta potential; a value greater than ±30 mV typically indicates good electrostatic stability.

Protocol for Surface Functionalization with a Targeting Ligand

Method: Covalent Conjugation of a Peptide Ligand to PEGylated Polymeric Nanoparticles

Principle: This protocol uses EDC/NHS chemistry to form an amide bond between surface carboxyl groups on the nanoparticle and primary amines on the targeting ligand.

Materials:

- Carboxyl-functionalized, PEG-coated nanoparticles (e.g., PLGA-PEG-COOH)

- Targeting peptide ligand with a terminal primary amine (e.g., RGD peptide)

- Coupling agents: 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) and N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)

- Reaction buffer: MES buffer (0.1 M, pH 5.5) or PBS (pH 7.4)

- Purification devices: Centrifugal filters (e.g., Amicon Ultra) or dialysis tubing

- Quenching agent: Glycine or ethanolamine

Procedure:

- Activation of Carboxyl Groups:

- Dilute the nanoparticle suspension in MES buffer (pH 5.5) to a final volume of 1 mL.

- Add a fresh-prepared solution of EDC (molar excess to COOH groups) and NHS (equal molar to EDC) to the nanoparticle suspension.

- React for 15-30 minutes at room temperature with gentle stirring to form an amine-reactive NHS ester on the nanoparticle surface.

- Ligand Conjugation:

- Add the peptide ligand solution (in PBS, pH 7.4) to the activated nanoparticle mixture. Use a molar excess of the ligand to ensure efficient coupling.

- Allow the reaction to proceed for 2-4 hours at room temperature with gentle stirring.

- Quenching and Purification:

- Stop the reaction by adding a 10x molar excess (relative to EDC) of glycine or ethanolamine and incubate for 30 minutes to quench any unreacted NHS esters.

- Purify the conjugated nanoparticles from unreacted reagents and free ligand using centrifugal filtration (with multiple washes with PBS) or dialysis against PBS for 24 hours.

- Verification:

- Confirm successful conjugation using techniques such as:

- FTIR: To detect new amide bond formation.

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): To detect elements unique to the ligand.

- Fluorescence Labeling: If the ligand is fluorescently tagged, measure fluorescence before and after purification.

- Confirm successful conjugation using techniques such as:

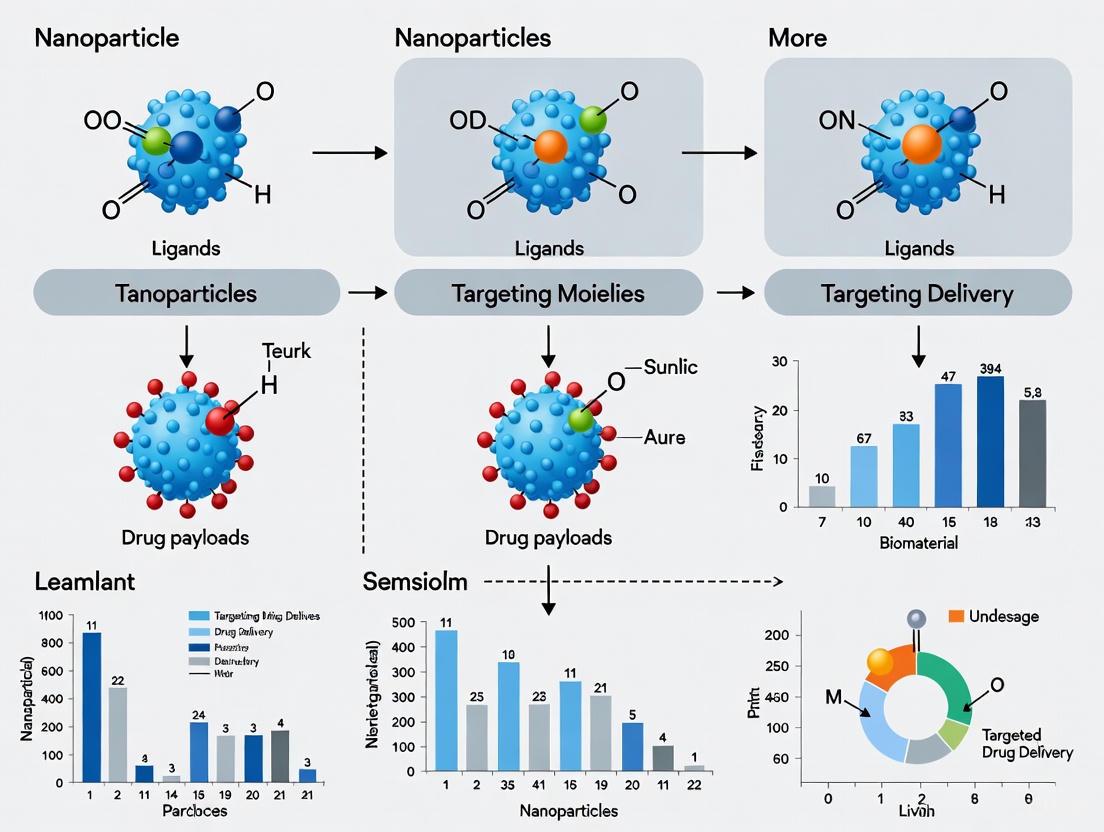

Visualization of Nanoparticle Design and Biological Journey

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for designing a precision nanoparticle, from core material selection to the final biological outcome, integrating the principles of size, surface properties, and targeting.

Diagram 1: Workflow for Precision Nanoparticle Design. This chart outlines the strategic process of engineering nanoparticles, highlighting how decisions about core materials and surface properties directly influence in vivo behavior and ultimate biological fate.

The biological journey of an intravenously administered nanoparticle, from circulation to its final intracellular fate, is a critical sequence of events determining therapeutic success.

Diagram 2: The Biological Journey of an Administered Nanoparticle. This sequence details the critical steps from injection to drug release, highlighting key decision points that lead to either successful targeting or clearance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs essential materials and reagents required for the synthesis, functionalization, and characterization of nanoparticle biomaterials as discussed in the protocols.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Nanoparticle Development and Characterization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Polymeric Core Materials | Biodegradable matrices for controlled drug release. | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) [4], Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) [5], Chitosan [1] [2]. |

| Lipid Components | Form the backbone of liposomes and lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) for nucleic acid and drug delivery. | Phosphatidylcholine, ionizable lipids (for LNPs), cholesterol [4]. |

| Stealth Coating Agents | Reduce protein adsorption and prolong systemic circulation by conferring a "stealth" effect. | Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) derivatives (e.g., DSPE-PEG, PLGA-PEG) [4] [1]. |

| Targeting Ligands | Enable active targeting by binding to specific receptors on target cells. | Folate [6], peptides (e.g., RGD) [1], antibodies or their fragments [1] [3]. |

| Crosslinking & Conjugation Reagents | Facilitate covalent attachment of ligands to the nanoparticle surface. | EDC (1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide), NHS (N-Hydroxysuccinimide) [1]. |

| Characterization Standards & Buffers | Provide a controlled environment for accurate measurement of size and zeta potential. | Disposable zeta cells, MES buffer for conjugation, PBS for dilution and purification [1]. |

| Ald-Ph-amido-PEG1-C2-NHS ester | Ald-Ph-amido-PEG1-C2-NHS ester, CAS:2101206-80-6, MF:C17H18N2O7, MW:362.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 13,14-Dihydro-15-keto-PGE2-d9 | 13,14-Dihydro-15-keto-PGE2-d9 Stable Isotope | Research-grade 13,14-Dihydro-15-keto-PGE2-d9, a deuterated metabolite of PGE2. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Application Notes: Functional Characteristics and Quantitative Performance

The efficacy of nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems is governed by the distinct properties of their constituent materials. The table below summarizes the key functional characteristics and quantitative performance metrics of the four primary material classes.

Table 1: Key Material Classes for Nanoparticle Drug Delivery Systems

| Material Class | Key Characteristics | Representative Materials | Primary Applications | Reported Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biopolymers | Biodegradability, biocompatibility, sustainability, tunable swelling, stimuli-responsiveness (e.g., pH, temperature) [7]. | Chitosan, cellulose, alginate, hyaluronan, PLGA [8] [7] [9]. | Controlled release systems, colon-specific delivery, tissue engineering, wound healing [8] [7]. | Swelling degree (SD) of chitosan: >100%; Carboxymethyl cellulose SD: 50-200 g/g [7]. Improved oral bioavailability of antibiotics [8]. |

| Proteins & Peptides | Self-assembly, high biocompatibility, capacity for functional engineering (e.g., incorporation of histidine, endosomal escape peptides) [10]. | Elastin-like Polypeptides (ELPs), Endosomal Escape Peptides (EEPs), ENTER system [10]. | Delivery of DNA, RNA, proteins, and gene editors; endosomal escape; targeted cell delivery [10]. | Gene editing efficiency of 65% with CRISPR-Cas9 and 83% with adenine base editor; minimal cell toxicity observed [10]. |

| Lipids | Biocompatible encapsulation, ionizable lipids enable endosomal escape, PEG-lipids improve stability [11] [12]. | Ionizable cationic lipids, phospholipids, cholesterol, PEG-lipids [11] [12]. | RNA delivery (mRNA vaccines, siRNA), intramuscular injection, liver-targeted therapies [11] [12]. | Catalyzed COVID-19 mRNA vaccines; success in clinical trials for siRNA (e.g., Patisiran) [11] [12]. |

| Metallic Nanoparticles | Unique optical/magnetic properties, high surface-to-volume ratio, tunable surfaces, capability for theranostics [13] [14]. | Gold (Au), Silver (Ag), Iron Oxide (Fe₃O₄) [13]. | Photothermal therapy, antimicrobial applications, MRI contrast agents, targeted drug delivery [13] [14]. | >90% drug loading; 3-5x improved tumor targeting; up to 99% antimicrobial activity for AgNPs [13]. PEGylation reduces macrophage uptake by 60-75% [13]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Formulation of Stimuli-Responsive Biopolymer Gels for Colon-Specific Drug Delivery

This protocol details the synthesis of interpolyelectrolyte complexes (IPECs) using natural pectins and synthetic polymers for colon-targeted drug release, leveraging the specific pH and enzymatic environment of the colon [8].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Anionic Biopolymer Solution: 1.0% (w/v) pectin (from various types) in deionized water.

- Cationic Polymer Solution: 1.0% (w/v) Eudragit EPO in deionized water.

- Drug Load Solution: Therapeutic agent dissolved in a suitable solvent compatible with the polymers.

- Simulated Gastric Fluid (SGF): pH 1.2 buffer.

- Simulated Intestinal Fluid (SIF): pH 6.8 buffer.

- Simulated Colonic Fluid (SCF): pH 7.4 buffer with relevant enzymes (e.g., pectinase).

Methodology:

- Polymer Preparation: Separately dissolve the weighed quantities of pectin and Eudragit EPO in deionized water under constant magnetic stirring (500 rpm) at room temperature for 2 hours to obtain clear, homogeneous 1% solutions.

- Complex Formation: Gradually add the Eudragit EPO solution to the pectin solution in a defined molar ratio (e.g., 1:1, 2:1, 1:2) under continuous stirring (700 rpm) for 1 hour.

- Drug Loading: Introduce the drug load solution to the anionic biopolymer solution prior to the complex formation step to ensure uniform encapsulation.

- Isolation & Washing: Recover the formed IPECs by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 15 minutes. Wash the pellet twice with deionized water to remove unreacted polymers and free drug.

- Lyophilization: Freeze the purified IPECs at -80°C for 4 hours and subsequently lyophilize for 24 hours to obtain a dry, stable powder for characterization and further use.

- In Vitro Release Testing: a. Dispense weighed amounts of drug-loaded IPECs into vessels containing 500 mL of SGF (pH 1.2), maintained at 37±0.5°C with continuous stirring (100 rpm). b. After 2 hours, withdraw samples and transfer the remaining formulation to SIF (pH 6.8) for an additional 3 hours. c. Finally, transfer to SCF (pH 7.4) and continue the experiment for up to 24 hours. d. Analyze the drug concentration in the withdrawn samples using UV-Vis spectroscopy or HPLC to determine the release profile at each stage [8].

Protocol: Engineering ENTER Nanoparticles for Efficient Cytosolic Delivery

This protocol describes the creation and validation of ENTER (elastin-based nanoparticles for therapeutic delivery), a protein-based platform designed for efficient endosomal escape and delivery of various macromolecular cargoes [10].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Engineered ELP Solution: Recombinantly expressed Elastin-like Polypeptide (ELP) incorporating histidine residues, dissolved in cold PBS or Tris buffer.

- Endosomal Escape Peptide (EEP) Solution: Synthesized EEP (e.g., S10 or machine learning-optimized EEP13) dissolved in DMSO or buffer.

- Therapeutic Cargo: CRISPR-Cas9 protein, Cre recombinase mRNA/protein, siRNA, or plasmid DNA.

- Cell Culture Media: Appropriate medium (e.g., DMEM, RPMI) for the target cell line.

- Staining Solution: Fluorescent antibodies or dyes for flow cytometry and microscopy.

Methodology:

- Nanoparticle Self-Assembly: a. Combine the Engineered ELP Solution, EEP Solution, and Therapeutic Cargo in a specific mass ratio on ice. b. Incubate the mixture at room temperature (20-25°C) for 30-60 minutes. The ELPs will undergo a temperature-induced phase transition, self-assembling into nanoparticles that encapsulate both the EEP and the cargo [10].

- Particle Characterization: Determine the particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential of the formed ENTER nanoparticles using dynamic light scattering (DLS).

- In Vitro Transfection: a. Seed target cells (e.g., HEK-293, lung fibroblasts, T cells) in a 24-well plate and culture until 70-80% confluency. b. Replace the medium with fresh media containing the ENTER nanoparticle formulation. c. Incubate cells for 4-48 hours at 37°C in a 5% CO₂ atmosphere.

- Efficacy Assessment: a. For Gene Editing (CRISPR-Cas9): After 48-72 hours, harvest cells and extract genomic DNA. Use T7E1 assay or next-generation sequencing to quantify indel frequency. b. For Gene Recombination (Cre recombinase): Use a reporter cell line (e.g., tdTomato). After 48 hours, analyze the percentage of fluorescent cells via flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy. c. For mRNA/siRNA Delivery: Measure the levels of the target protein or mRNA by Western blot or qPCR, respectively [10].

- Cytotoxicity Evaluation: Perform an MTT or CellTiter-Glo assay alongside the transfection experiment to ensure minimal cytotoxicity.

Diagram 1: ENTER Nanoparticle Assembly and Endosomal Escape Mechanism.

Protocol: Synthesis and Functionalization of Theranostic Metal Nanoparticles

This protocol outlines the preparation of theranostic metal nanoparticles (e.g., gold, iron oxide) for combined drug delivery and imaging, with a focus on mitigating toxicity through surface modification [13].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Metal Precursor Solution: Chloroauric acid (for AuNPs) or iron chloride (for Fe₃O₄ NPs) in deionized water.

- Reducing Agent Solution: Sodium citrate or sodium borohydride.

- Stabilizing Agent Solution: PEG-thiol (for AuNPs) or PEG-carboxyl (for Fe₃O₄ NPs).

- Targeting Ligand Solution: Antibodies, peptides, or small molecules (e.g., folic acid) functionalized with thiol or amine groups.

- Drug Load Solution: Chemotherapeutic agent (e.g., doxorubicin).

Methodology:

- Nanoparticle Synthesis: a. Gold Nanoparticles (Turkevich Method): Heat 100 mL of 1 mM chloroauric acid solution to boiling under reflux. Rapidly add 10 mL of 38.8 mM sodium citrate solution with vigorous stirring. Continue heating and stirring until the solution develops a deep red color (≈15 minutes). Cool to room temperature. b. Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (Co-precipitation): Mix FeCl₂ and FeCl₃ in a 1:2 molar ratio in deoxygenated water under an inert nitrogen atmosphere. Add ammonium hydroxide solution dropwise under vigorous stirring. A black precipitate will form. Heat the mixture to 70-80°C for 30 minutes.

- Purification: Purify the synthesized nanoparticles by repeated centrifugation and redispersion in deionized water (3 cycles).

- Surface Functionalization (PEGylation): a. Incubate the purified nanoparticle solution with a 100-fold molar excess of PEG-thiol (for AuNPs) or PEG-carboxyl (for Fe₃O₄ NPs) for 24 hours at room temperature with gentle shaking. b. Purify the PEGylated nanoparticles via centrifugation to remove unbound PEG.

- Drug Loading & Targeting: a. Drug Loading: For AuNPs, incubate PEGylated nanoparticles with the drug load solution. For Fe₃O₄ NPs, drug molecules can be conjugated to the carboxyl groups on the PEG chain using EDC/NHS chemistry. b. Ligand Conjugation: Activate the terminal group of the PEG chain (e.g., carboxyl) using EDC/sulfo-NHS. Add the Targeting Ligand Solution and allow the conjugation to proceed for 4-6 hours. Purify the final product.

- In Vitro Validation: a. Cytotoxicity (IC₅₀): Treat cells with a concentration range of the drug-loaded nanoparticles (e.g., 0-100 μg/mL) for 72 hours and perform an MTT assay. b. Imaging: Use the functionalized Fe₃O₄ NPs as a T₂ contrast agent in MRI, or utilize the surface plasmon resonance of AuNPs for photothermal imaging [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Nanoparticle Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Cationic Lipids | Forms core of LNPs; binds nucleic acids; enables endosomal escape via protonation in acidic endosomes [11] [12]. | Critical component in mRNA COVID-19 vaccines and siRNA drugs (e.g., Onpattro) [11] [12]. |

| PEGylated Lipids/Lipid-PEG | Shields nanoparticle surface; improves stability, reduces opsonization, and extends circulation half-life [11] [13]. | Co-lipid in LNP formulations; PEGylation of metal nanoparticles to reduce macrophage uptake by 60-75% [13]. |

| Cholesterol | Integrates into lipid bilayers; enhances structural integrity and stability of lipid nanoparticles [12]. | A key component (≈40 mol%) in LNP formulations to improve packing and prevent leakage [12]. |

| Endosomal Escape Peptides (EEPs) | Disrupts endosomal membrane to facilitate cargo release into the cytoplasm [10]. | Core component of the ENTER system (e.g., EEP13); clustered inside nanoparticles for targeted endosomal puncture [10]. |

| Elastin-like Polypeptides (ELPs) | Stimuli-responsive (temperature) protein polymers that self-assemble into nanoparticles [10]. | Backbone of the ENTER system; engineered with histidine to act as a "proton sponge" and trigger disassembly in endosomes [10]. |

| Chitosan | A natural, mucoadhesive biopolymer; enables sustained and targeted release, especially in mucosal environments [7] [9]. | Used in colon-specific drug delivery systems and vaginal gels to improve drug retention and absorption [9]. |

| Targeting Ligands (e.g., Vitamin B12, Peptides) | Conjugated to nanoparticle surface to enable active targeting to specific cells or receptors [8]. | Vitamin B12 modification on antibiotic-poly saccharide conjugates for improved oral bioavailability [8]. |

| 5'-O-DMT-N4-Bz-2'-F-dC | 5'-O-DMT-N4-Bz-2'-F-dC, MF:C37H34FN3O7, MW:651.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 12-Ethyl-9-hydroxycamptothecin | 12-Ethyl-9-hydroxycamptothecin, MF:C22H20N2O5, MW:392.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Nanoparticles have transformed contemporary medicine by providing innovative solutions to longstanding challenges in drug delivery. Their core advantages—enhanced biocompatibility, precision controlled release, and superior barrier penetration—address critical limitations of traditional therapeutics, including poor solubility, systemic toxicity, and inadequate targeting. These engineered systems operate at the nanoscale (1-100 nm), leveraging unique physicochemical properties that bulk materials cannot exhibit [15]. This application note examines these foundational advantages within the context of advanced biomaterials research, providing detailed protocols and analytical frameworks for developing next-generation nanotherapeutics.

The strategic value of nanoparticles lies in their multifunctional design. By engineering specific physicochemical properties such as size, surface charge, and functionalization, researchers can create carriers that navigate biological systems with unprecedented precision [16] [17]. These capabilities are particularly valuable for treating conditions where biological barriers and targeted delivery are paramount, including cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and chronic inflammatory disorders.

Advantage Analysis: Core Mechanisms and Therapeutic Benefits

Enhanced Biocompatibility and Safety

Biocompatibility in nanomaterial design encompasses both intrinsic safety and the ability to function within biological systems without provoking adverse responses. This is achieved through careful material selection and surface engineering.

- Material Selection: Biodegradable polymers like poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and poly(lactic acid) (PLA) are popular choices due to their adjustable degradation rates, which can be tailored to match therapeutic release kinetics [18]. Natural polymers and lipids often exhibit superior biocompatibility profiles compared to synthetic alternatives [19].

- Surface Functionalization: Modifying nanoparticle surfaces with hydrophilic polymers such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) creates a protective layer that reduces opsonization and recognition by the immune system, extending circulation time and minimizing immune reactions [17] [15].

- Rigorous Toxicity Profiling: Comprehensive assessment requires evaluating potential nanotoxicological concerns, including oxidative stress, inflammatory responses, and cytotoxic reactions [15]. The protein corona—a layer of adsorbed biomolecules that forms upon introduction to biological fluids—significantly influences nanoparticle behavior in vivo and must be characterized during development [20].

Precision Controlled Release

Controlled release mechanisms enable spatial and temporal precision in drug delivery, maintaining therapeutic concentrations at target sites while minimizing off-target effects.

- Core-Shell Architecture: This design features a core material that encapsulates the therapeutic agent and a protective shell that manages release kinetics. The shell provides stability and can be engineered to respond to specific stimuli [18].

- Stimuli-Responsive Systems: "Intelligent" nanocarriers release their payload in response to specific pathological stimuli:

- pH-Sensitivity: Utilizing materials that undergo dissolution or structural changes at the weakly acidic pH of tumor microenvironments (pH 6.5-7.2) or inflamed tissues [21].

- Enzyme-Responsiveness: Designing carriers that degrade in the presence of enzymes overexpressed in disease environments, such as matrix metalloproteinases in tumors [21].

- Tailored Release Kinetics: The release profile is governed by diffusion through the polymer matrix, nanoparticle erosion, and combination mechanisms, allowing for sustained release over periods ranging from hours to weeks [18].

Superior Barrier Penetration

The ability to cross biological barriers is perhaps the most transformative advantage of nanoparticle systems, particularly for targeting the central nervous system.

- Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) Transcytosis: Nanoparticles utilize endogenous transport pathways to cross the BBB. Receptor-Mediated Transcytosis (RMT) is a primary mechanism, where surface-functionalized ligands (e.g., transferrin, insulin) bind to specific receptors on endothelial cells, initiating vesicular transport across the barrier [22] [20].

- Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) Effect: In oncology, nanocarriers (typically 20-200 nm) preferentially accumulate in tumor tissues due to leaky vasculature and impaired lymphatic drainage, enabling passive targeting [16].

- Mucosal Penetration: For oral delivery, nanoparticles protect drugs from degradation in the gastrointestinal tract and facilitate absorption across the intestinal mucosa, significantly improving bioavailability for drugs with poor solubility [21].

Table 1: Quantitative Analysis of Nanoparticle Performance in Barrier Penetration

| Nanoparticle Type | Average Size (nm) | BBB Penetration Efficiency (% Injected Dose/g Tissue) | Key Transport Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymeric NPs (PLGA) | 80-150 | 0.5-1.5% | Receptor-Mediated Transcytosis [23] |

| Liposomes | 70-120 | 0.3-0.8% | Adsorptive-Mediated Transcytosis [22] |

| Solid Lipid NPs (SLNs) | 50-100 | 0.4-1.2% | Passive Diffusion & Carrier-Mediated Transport [23] |

| Gold Nanoparticles | 15-40 | 0.1-0.5% | Cell-Mediated Transcytosis [23] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Formulation of pH-Responsive Polymeric Nanoparticles

This protocol details the synthesis of core-shell nanoparticles designed for controlled drug release in the acidic tumor microenvironment, using the solvent evaporation method.

- Research Objective: To prepare and characterize poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles coated with a pH-sensitive Eudragit shell for colorectal cancer therapy.

Materials:

- Polymer Phase: PLGA (50:50), 100 mg

- pH-Sensitive Coating: Eudragit S100, 50 mg

- Organic Solvent: Dichloromethane (DCM), 10 mL

- Aqueous Phase: Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, 1% w/v), 50 mL

- Model Drug: 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU), 10 mg

- Equipment: High-speed homogenizer, magnetic stirrer, sonicator, centrifugation equipment

Procedure:

- Organic Phase Preparation: Dissolve PLGA (100 mg) and 5-FU (10 mg) in dichloromethane (10 mL) using a magnetic stirrer until a clear solution is obtained.

- Emulsion Formation: Add the organic phase dropwise to 50 mL of 1% PVA solution while homogenizing at 15,000 rpm for 5 minutes to form a stable oil-in-water (o/w) emulsion.

- Solvent Evaporation: Transfer the emulsion to a beaker and stir continuously at 600 rpm for 4 hours at room temperature to allow complete solvent evaporation and nanoparticle hardening.

- pH-Sensitive Coating: Re-disperse the collected nanoparticles in 20 mL of Eudragit S100 solution (0.5% w/v in ethanol). Stir gently for 2 hours to allow adsorption of the pH-sensitive polymer.

- Purification and Collection: Centrifuge the suspension at 20,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C. Wash the pellet three times with deionized water to remove excess surfactant and unencapsulated drug.

- Lyophilization: Re-suspend the final nanoparticles in a minimal volume of water and lyophilize for 48 hours to obtain a free-flowing powder for characterization and storage.

Quality Control Parameters:

- Particle Size and PDI: Analyze by dynamic light scattering (DLS); target size: 100-150 nm, PDI < 0.2.

- Drug Encapsulation Efficiency: Determine by HPLC after nanoparticle dissolution; calculate as (Actual drug loading / Theoretical loading) × 100%.

- Surface Morphology: Examine by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) for spherical shape and smooth surface.

- In Vitro Drug Release: Perform in phosphate buffers at pH 7.4 and 6.0 to verify pH-dependent release profile.

Protocol: Functionalization for Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration

This protocol describes the surface modification of nanoparticles with targeting ligands to facilitate receptor-mediated transcytosis across the blood-brain barrier.

- Research Objective: To conjugate transferrin ligands to the surface of solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) for enhanced brain targeting.

Materials:

- Nanoparticle Core: Pre-formed SLNs (100 nm, amine-terminated), 10 mg/mL

- Targeting Ligand: Human transferrin, 5 mg

- Crosslinker: N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) and 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC)

- Reaction Buffer: MES buffer (0.1 M, pH 6.0) and PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Purification: Zeba Spin Desalting Columns (7K MWCO)

Procedure:

- Ligand Activation:

- Dissolve transferrin (5 mg) in 2 mL of MES buffer (0.1 M, pH 6.0).

- Add EDC (10 mM final concentration) and NHS (5 mM final concentration) to the transferrin solution.

- Incubate the mixture for 15 minutes at room temperature with gentle mixing to activate carboxyl groups on the transferrin molecule.

- Conjugation Reaction:

- Add 2 mL of amine-terminated SLNs (10 mg/mL in PBS, pH 7.4) to the activated transferrin solution.

- React for 2 hours at room temperature with continuous gentle stirring to form stable amide bonds between the nanoparticle surface and targeting ligand.

- Purification:

- Remove unreacted crosslinker and free transferrin using Zeba Spin Desalting Columns according to manufacturer instructions.

- Centrifuge at 4,000 × g for 2 minutes, collecting the purified conjugate in the flow-through.

- Characterization:

- Confirm conjugation success by measuring changes in zeta potential and hydrodynamic diameter using dynamic light scattering.

- Quantify ligand density on the nanoparticle surface using fluorescence microscopy (for fluorescently labeled transferrin) or Bradford protein assay.

- Ligand Activation:

Visualization: Mechanisms and Workflows

BBB Penetration Pathways

Core-Shell Nanoparticle Synthesis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Nanoparticle Drug Delivery Research

| Research Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| PLGA (Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) | Biodegradable polymer for nanoparticle core | Tunable degradation rate, FDA-approved, excellent drug encapsulation capability [18] |

| Eudragit S100 | pH-sensitive coating polymer for colon targeting | Dissolves at pH >7, protects drug in upper GI tract [21] |

| PEG (Polyethylene glycol) | Surface functionalization for stealth properties | Reduces opsonization, extends circulation half-life [17] |

| Transferrin | Targeting ligand for blood-brain barrier penetration | Binds to transferrin receptors on endothelial cells, enables RMT [22] [20] |

| DSPE-PEG-Maleimide | Functional lipid for ligand conjugation | Reactive maleimide group for thiol-based chemistry, PEG spacer [17] |

| PVA (Polyvinyl alcohol) | Surfactant for emulsion stabilization | Forms protective layer during nanoparticle formation, controls particle size [21] |

| EDC/NHS Chemistry | Crosslinking system for ligand conjugation | Activates carboxyl groups for amide bond formation with amines [17] |

| D-Ribose 5-phosphate disodium | D-Ribose 5-phosphate disodium, MF:C5H9Na2O8P, MW:274.07 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1,2,3,4,6,7,8-Heptachlorodibenzofuran | 1,2,3,4,6,7,8-Heptachlorodibenzofuran, CAS:67652-39-5, MF:C12HCl7O, MW:409.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Targeted drug delivery using nanoparticle (NP) biomaterials represents a transformative approach in modern therapeutics, aiming to enhance drug efficacy while minimizing systemic side effects [24]. The core principle involves the precise delivery of therapeutic agents to specific cells, tissues, or organs, a capability particularly crucial in oncology where traditional therapies like chemotherapy and radiotherapy lack specificity [24] [25]. This application note delineates the fundamental mechanisms—passive and active targeting—that enable the site-specific accumulation of nanocarriers. Passive targeting primarily leverages the unique pathological features of diseased tissues, such as the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect in solid tumors [24] [25]. In contrast, active targeting employs surface-functionalized ligands to actively recognize and bind to specific biomarkers on target cells [26] [27]. Understanding these strategies' distinct mechanisms, applications, and limitations is essential for researchers and drug development professionals designing next-generation nanomedicines. The following sections provide a detailed comparison, supported by quantitative data, experimental protocols, and visual workflows, to guide the rational design of targeted nanoparticle biomaterials.

Core Targeting Mechanisms

The journey of a nanoparticle from administration to site-specific action involves a multi-step biological cascade. The following diagram illustrates the critical pathways for passive and active targeting strategies, from systemic circulation to intracellular delivery.

Passive Targeting

Passive targeting is a strategy that capitalizes on the inherent pathophysiological characteristics of diseased tissues to achieve selective drug accumulation [24] [25]. The most recognized mechanism is the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect, first described by Maeda and Matsumura in 1986, which is a hallmark of many solid tumors [25]. The EPR effect arises from the abnormal tumor vasculature, characterized by wide fenestrations (gaps of 100-800 nm) between endothelial cells, combined with impaired lymphatic drainage [24] [25]. This unique environment allows nanoparticles of a specific size range to extravasate from the bloodstream into the tumor interstitium, where they are retained and accumulate over time [24]. The efficiency of passive targeting is predominantly governed by the physicochemical properties of the nanocarrier itself, rather than by specific molecular recognition events.

Active Targeting

Active targeting involves the functionalization of nanoparticle surfaces with biological ligands that specifically recognize and bind to antigens or receptors overexpressed on the surface of target cells [26] [27]. This strategy provides an additional layer of specificity beyond the passive accumulation conferred by the EPR effect. The binding event between the ligand-decorated nanoparticle and the cell surface receptor typically triggers receptor-mediated endocytosis, promoting the internalization of the nanocarrier and its payload into the target cell [27]. This active targeting mechanism is particularly valuable for delivering therapeutics to specific cell types, overcoming biological barriers like the blood-brain barrier, and enhancing cellular uptake even in cases where passive accumulation is inefficient [28] [27]. It is crucial to note that active targeting generally functions as a complementary step after the nanoparticle has reached the target tissue via passive mechanisms (primarily the EPR effect) and is not a standalone homing mechanism from systemic circulation [25].

Comparative Analysis: Key Parameters

The choice between passive and active targeting strategies, or their combination, depends heavily on the intended application and the biological barriers to be overcome. The table below summarizes the defining characteristics, advantages, and challenges of each approach.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Passive and Active Targeting Strategies

| Parameter | Passive Targeting | Active Targeting |

|---|---|---|

| Core Mechanism | Exploits the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect of pathological sites (e.g., tumors) [24] [25]. | Utilizes ligand-receptor interactions for specific cell recognition and binding [26] [27]. |

| Governed By | Physicochemical properties of the NP: size, surface charge, composition, and hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity [24] [26]. | Nature of the targeting ligand (e.g., antibody, peptide, aptamer, small molecule) and receptor density on target cells [27]. |

| Primary Effect | Extravasation and accumulation within the tumor interstitium or specific organ structures [24]. | Enhanced cellular internalization via receptor-mediated endocytosis and improved tumor cell specificity [27]. |

| Key Advantages | Simpler NP design, broader applicability to fast-growing solid tumors, and proven clinical success (e.g., Doxil) [24] [25]. | Increased specificity for target cells, higher intracellular drug concentration, potential to overcome biological barriers (e.g., BBB) [28] [27]. |

| Major Challenges | High heterogeneity of the EPR effect between patients and tumor types; limited penetration into dense tumor cores due to high interstitial fluid pressure [25]. | Complex manufacturing and ligand conjugation; potential for immunogenicity; reliance on initial passive accumulation for tumor delivery [25] [27]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Formulating Passively Targeted Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs)

This protocol details the synthesis and characterization of PEGylated lipid nanoparticles optimized for passive targeting via the EPR effect, based on established methods for liposomal formulations like Doxil [24] [26].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Lipids: Hydrogenated soy phosphatidylcholine (HSPC), cholesterol, PEG-lipid (e.g., DSPE-PEG2000) [26].

- Therapeutic Agent: Hydrophilic drug (e.g., Doxorubicin HCl) or nucleic acids (e.g., siRNA, mRNA).

- Solvents: Ethanol (absolute), chloroform, ammonium sulfate solution (250 mM, pH 5.5).

- Buffers: HEPES-buffered saline (HBS, pH 7.4).

- Equipment: Microfluidic nanoparticle formulator (e.g., TAMARA system), thermobarrel extruder with polycarbonate membranes (50-200 nm), dynamic light scattering (DLS) instrument, dialysis tubing (MWCO 100 kDa).

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Lipid Film Formation: Dissolve HSPC, cholesterol, and PEG-lipid at a molar ratio of 55:40:5 in an ethanol-chloroform mixture (3:1 v/v) in a round-bottom flask. Remove solvents under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator (40°C water bath) to form a thin, homogeneous lipid film.

- Hydration and Preliminary Sizing: Hydrate the dried lipid film with 250 mM ammonium sulfate solution (pre-heated to 60°C) to a final lipid concentration of 10-20 mM. Vortex vigorously for 5 minutes to form large multilamellar vesicles (LMVs). Sequentially extrude the lipid suspension through polycarbonate membranes of decreasing pore size (e.g., 400 nm, 200 nm, 100 nm, and finally 80 nm) using a thermobarrel extruder maintained at 60°C (above the lipid phase transition temperature).

- Remote Drug Loading: Transfer the blank LNPs to a dialysis bag and dialyze against HBS (pH 7.4) at 4°C for 18 hours to establish a transmembrane ammonium sulfate gradient. Incubate the dialyzed LNPs with the drug solution (e.g., doxorubicin) at a drug-to-lipid ratio of 1:10 (w/w) for 60 minutes at 60°C. The gradient drives the active loading and encapsulation of the drug.

- Purification and Storage: Purify the drug-loaded LNPs from unencapsulated drug via dialysis or size-exclusion chromatography. Sterile-filter the final formulation (0.22 µm pore size) and store under inert gas (N₂) at 4°C.

III. Characterization and Quality Control

- Size and Polydispersity (PDI): Measure by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS). Target diameter: 80-120 nm with PDI < 0.2 [24] [26].

- Surface Charge (Zeta Potential): Measure by Laser Doppler Micro-electrophoresis. Target: Near-neutral or slightly negative charge to reduce non-specific uptake.

- Encapsulation Efficiency (EE%): Determine by measuring free drug concentration in the supernatant after ultrafiltration/centrifugation using HPLC or UV-Vis spectroscopy. Calculate EE% = (Total drug - Free drug) / Total drug × 100%. Target: > 90% [26].

Protocol 2: Functionalizing Nanoparticles for Active Targeting

This protocol describes the conjugation of a targeting ligand (e.g., the peptide-based ligand ALN for bone targeting) to pre-formed nanoparticles for active targeting to specific tissues or cells [27].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Nanoparticles: Pre-formed, purified nanoparticles (e.g., liposomes, polymeric NPs) with surface functional groups (e.g., maleimide, NHS-ester, DBCO).

- Targeting Ligand: Ligand of choice (e.g., Alendronate/ALN for bone, folate, RGD peptide, antibodies) modified with a complementary reactive group (e.g., thiol, amine, azide).

- Coupling Buffer: Degassed PBS (pH 7.4) or other suitable buffer (e.g., HEPES, pH 8.5 for amine coupling).

- Purification Equipment: Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) columns (e.g., Sephadex G-25) or dialysis membranes.

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Ligand Preparation: If necessary, reduce disulfide bonds in the ligand (e.g., antibodies) using tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) to generate free thiols. Purify the ligand immediately before use via desalting.

- Conjugation Reaction: Dilute the pre-formed nanoparticles in the appropriate coupling buffer to a concentration of 1-5 mg/mL. Add the purified ligand to the nanoparticle solution at a 2:1 to 5:1 molar ratio (ligand to available nanoparticle surface groups). Incubate the reaction mixture with gentle stirring or rotation for 4-16 hours at room temperature, protected from light.

- Quenching and Purification: Terminate the reaction by adding a 100-fold molar excess of a quenching agent (e.g., L-cysteine for maleimide reactions, glycine for NHS-ester reactions) and incubate for 30 minutes. Purify the ligand-conjugated nanoparticles from unreacted ligand and quenching agents using SEC or extensive dialysis.

- Final Formulation: Concentrate the purified, functionalized nanoparticles if necessary, sterile-filter (0.22 µm), and store at 4°C.

III. Characterization and Quality Control

- Ligand Coupling Efficiency: Quantify using colorimetric assays (e.g., BCA for proteins, Ellman's for thiols), fluorescence labeling, or SDS-PAGE. Report the number of ligand molecules per nanoparticle.

- Binding Affinity and Specificity: Validate using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) or in vitro cell-binding assays with target-positive and target-negative cell lines. Perform competitive inhibition assays with free ligand.

- Functional Integrity: Confirm that functionalization does not adversely affect nanoparticle size (DLS), stability, or drug release profile.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Targeted Nanoparticle Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids (e.g., MC3) | Enables efficient encapsulation of nucleic acids (siRNA, mRNA) and facilitates endosomal escape due to pH-dependent charge shift [26]. | Core component of LNPs for gene therapy and mRNA vaccines (e.g., Onpattro). |

| PEG-Lipids (e.g., DSPE-PEG2000) | Confers "stealth" properties by forming a hydrophilic corona, reducing opsonization, prolonging blood circulation time, and enhancing passive targeting via the EPR effect [24] [26]. | Standard component in long-circulating nanocarriers (e.g., Doxil). PEG molar mass and density are critical parameters. |

| Targeting Ligands (e.g., Alendronate/ALN) | Binds with high affinity to hydroxyapatite in bone mineral, directing nanocarriers to bone tissue and osteosarcoma sites for active targeting [27]. | Functionalization agent for bone-targeted drug delivery systems. |

| Bisphosphonates (BPs) | Small molecules with P-C-P structure that chelate calcium ions in hydroxyapatite (HAp), the main inorganic component of bone [27]. | Widely used for active targeting to bone in treating osteoporosis, bone metastases, and osteosarcoma. |

| Antibodies & Aptamers | Provide high specificity and affinity for unique cell surface antigens or proteins, enabling highly selective active targeting [24] [27]. | Used for functionalizing nanoparticles to target specific cancer cell markers (e.g., EGFR, HER2). |

| Microfluidic Formulator | Enables precise, reproducible, and scalable mixing of organic and aqueous phases to produce nanoparticles with controlled size, low PDI, and high encapsulation efficiency [26]. | Essential equipment for the robust and tunable synthesis of lipid and polymeric nanoparticles. |

| 8-Deacetylyunaconitine | 8-Deacetylyunaconitine, MF:C33H47NO10, MW:617.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Azido-PEG5-S-methyl ethanethioate | Azido-PEG5-S-methyl ethanethioate, MF:C14H27N3O6S, MW:365.45 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Quantitative Data for Nanoparticle Design

Successful targeting is critically dependent on the precise engineering of nanoparticle properties. The following table consolidates key quantitative parameters that govern the behavior of nanocarriers in biological systems.

Table 3: Key Physicochemical Parameters for Optimizing Nanoparticle Targeting

| Design Parameter | Optimal Range / Target Value | Rationale & Impact on Targeting |

|---|---|---|

| Particle Size | 20-150 nm [24] [26] [25] | Optimal for EPR-mediated passive targeting. Size >150 nm increases liver/spleen clearance; <7 nm leads to rapid renal filtration [26] [25]. |

| Polydispersity Index (PDI) | < 0.2 [26] | Indicates a monodisperse population, ensuring consistent pharmacokinetics and biodistribution. |

| Zeta Potential | Approx. -10 to +10 mV (for passive) [26] | Near-neutral charge minimizes non-specific interactions with plasma proteins and cell membranes, prolonging circulation. |

| PEG Chain Length | 1 - 5 kDa [24] | Longer PEG chains (e.g., 5 kDa) can more effectively shield the nanoparticle surface and extend circulation half-life. |

| PEG Density | 5 - 20% (w/w of total lipid) [24] | Sufficient density is required for effective "stealth" properties; optimal range balances steric stabilization with drug loading and release. |

| Ligand Density | Variable (e.g., 0.5-5 mol%) [27] | Requires empirical optimization; too low reduces targeting efficacy, too high can opsonize particles and alter nanocarrier physicochemical properties. |

Passive and active targeting strategies represent two complementary pillars of modern nanoparticle-based drug delivery. Passive targeting, driven by the EPR effect and finely tuned nanoparticle physicochemical properties, provides the foundational mechanism for accumulation in pathological tissues. Active targeting, achieved through sophisticated surface functionalization with specific ligands, builds upon this foundation to enhance cellular uptake and specificity. The integration of both strategies, informed by a deep understanding of the multi-step biological cascade and guided by robust experimental protocols and quantitative design parameters, holds the greatest promise for developing the next generation of precise, effective, and clinically transformative nanomedicines. As the field advances, the incorporation of bioresponsive elements and computational/AI-driven design will further refine the spatiotemporal control of therapeutic delivery [29] [30].

Synthesis, Engineering, and Therapeutic Applications Across Disease States

Green Synthesis and Fungal-Mediated Production of Multimetallic Nanoparticles

The development of targeted drug delivery systems is a critical frontier in modern medicine, and nanoparticle biomaterials are poised to revolutionize this field. Among the various synthesis methods, fungal-mediated production of multimetallic nanoparticles (MMNPs) represents a particularly promising green synthesis route. This approach leverages the natural metabolic capabilities of fungi to create complex nanoparticles composed of two or more metals, offering synergistic benefits over their monometallic counterparts [31]. These MMNPs exhibit enhanced catalytic activity, superior stability, and improved biocompatibility—properties that are highly valuable for biomedical applications [31]. As the demand for sustainable nanomaterial production grows, fungal synthesis stands out as an environmentally friendly alternative to traditional physical and chemical methods, eliminating the need for toxic chemicals while providing a cost-effective and scalable platform for generating advanced drug delivery vehicles [31] [32].

Fundamental Mechanisms of Fungal-Mediated Synthesis

Fungi serve as efficient bio-factories for nanoparticle synthesis due to their unique biological characteristics, including high metal resistance, substantial biomass production, and the ability to secrete numerous extracellular metabolites [31]. The structural features of fungi, particularly their filamentous mycelial network with a high surface area-to-mass ratio, provide an ideal template for nanoparticle nucleation and growth [31].

Synthesis Pathways

Fungi employ two primary pathways for nanoparticle synthesis, each with distinct mechanisms and advantages for drug delivery applications:

Extracellular Synthesis: Fungi release a wide array of extracellular metabolites, including enzymes, proteins, polysaccharides, flavonoids, and phenolic compounds, which act as both reducing and stabilizing agents during nanoparticle formation [31]. Key enzymes such as NADH-dependent nitrate reductase deliver electrons to metal ions, reducing them to their neutral metallic state (M0) [31]. Secondary metabolites including anthraquinones and hydroxyquinoline also function as electron donors, facilitating reduction and stabilization processes. This extracellular approach offers significant advantages for drug delivery applications through simpler nanoparticle recovery, better scalability, and reduced purification requirements.

Intracellular Synthesis: This approach involves the binding of metal ions (M+) to the fungal cell surface through electrostatic interactions between positively charged metal ions and negatively charged lysine residues on the fungal cell membrane [31]. Once attached, metal ions are reduced by enzymes and metabolites within the fungal cell membrane, with biochemical agents transforming metal ions into neutral metal atoms (M0) that aggregate into nanoparticles beneath the cell surface [31]. While this method can produce more uniform nanoparticles, it presents challenges for large-scale drug delivery applications due to more complex extraction requirements.

Stabilization Mechanisms

Stability is crucial for drug delivery nanoparticles to maintain their structural integrity and functionality in biological environments. Fungi naturally produce biomolecules that adhere to nanoparticle surfaces, preventing agglomeration and enhancing stability [31]. Proteins and amino acid residues serve as effective capping agents, with free amino groups (particularly cysteine residues) and negative carboxyl groups from cell wall enzymes creating electrostatic attractions that stabilize the nanoparticles [31]. This biological capping not only improves colloidal stability but can also enhance biocompatibility and provide functional groups for further conjugation with therapeutic agents.

Experimental Protocols

Fungal Cultivation and Biomass Preparation

Objective: To generate fungal biomass capable of synthesizing multimetallic nanoparticles for drug delivery applications.

Materials:

- Fungal strains (e.g., Fusarium oxysporum, Aspergillus niger)

- Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) plates

- Liquid growth medium (e.g., Malt Extract Glucose Yeast Extract Peptone (MGYP))

- Sterile filtration units (0.22 µm)

- Incubator shaker

- Centrifuge

Procedure:

- Maintain fungal cultures on PDA plates at 28°C for 5-7 days.

- Inoculate 100 mL of sterile liquid MGYP medium in a 500 mL Erlenmeyer flask with 5-10 mycelial plugs (5 mm diameter) from actively growing fungal cultures.

- Incubate at 28°C with continuous shaking at 120 rpm for 72-96 hours.

- Harvest biomass by filtration through Whatman No. 1 filter paper and wash extensively with sterile distilled water (3-5 times) to remove medium components.

- Transfer 10 g of fresh, clean biomass to 100 mL of sterile distilled water in a 500 mL Erlenmeyer flask.

- Incubate at 28°C with shaking at 120 rpm for 48-72 hours to allow secretion of extracellular metabolites.

- Filter the culture through Whatman No. 1 filter paper to separate biomass from the cell-free filtrate containing extracellular metabolites.

- Store the cell-free filtrate at 4°C for extracellular synthesis of MMNPs (to be used in Protocol 3.2).

Synthesis of Multimetallic Nanoparticles

Objective: To synthesize multimetallic nanoparticles using fungal metabolites for drug delivery applications.

Materials:

- Fungal cell-free filtrate (from Protocol 3.1)

- Metal precursors (aqueous solutions of AgNO₃, HAuCl₄, ZnCl₂, CuSO₄)

- Magnetic stirrer with heating

- Ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) spectrophotometer

- pH meter

Procedure: For extracellular synthesis:

- Adjust the pH of the cell-free filtrate to the optimal range (typically pH 8-10) using 0.1M NaOH or 0.1M HCl [33].

- Mix metal precursor solutions in the desired molar ratios (e.g., 3:1 Au:Ag for core-shell structures) to a final combined metal concentration of 1-3 mM in the reaction mixture.

- Add the metal precursor mixture to the cell-free filtrate in a 1:1 ratio (v/v) under continuous stirring at 200 rpm.

- Incubate the reaction mixture at 60-80°C for 24-48 hours while monitoring color changes visually and via UV-vis spectroscopy (300-800 nm) at regular intervals.

- Recover nanoparticles by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 20 minutes.

- Wash the pellet three times with sterile distilled water to remove unreacted precursors and biomolecules.

- Resuspend the purified MMNPs in sterile water or buffer and store at 4°C for characterization and application.

For intracellular synthesis:

- Follow Protocol 3.1 steps 1-4 to obtain clean, fresh fungal biomass.

- Expose 10 g of biomass to 100 mL of metal precursor solution (1-3 mM total metal concentration) in the desired molar ratios.

- Incubate at 28°C with shaking at 120 rpm for 24-72 hours.

- Monitor nanoparticle formation by observing color changes in the biomass.

- Recover biomass by filtration and wash with sterile distilled water to remove unabsorbed metal ions.

- Lyse fungal cells using sonication or French press to release intracellular nanoparticles.

- Purify nanoparticles through centrifugation and washing cycles as described in the extracellular method.

Optimization Using Design of Experiments

Objective: To systematically optimize synthesis parameters for enhanced nanoparticle properties relevant to drug delivery.

Materials:

- Statistical software (e.g., R, Minitab, Design-Expert)

- Robotics-assisted liquid handling platform (for high-throughput screening)

- Analytical instruments for characterization (DLS, UV-vis, TEM)

Procedure:

- Identify critical process parameters: pH, temperature, precursor concentration, reaction time, and fungal strain.

- Design experiments using Response Surface Methodology (RSM) with Central Composite Design or Box-Behnken design.

- Employ automated liquid handling systems to prepare distinct formulations systematically [34].

- Characterize key response variables: nanoparticle size, polydispersity index, zeta potential, and drug encapsulation efficiency.

- Develop mathematical models to correlate process parameters with response variables.

- Validate models experimentally and establish design space for reproducible MMNP synthesis.

- Implement machine learning approaches like the Tunable Nanoparticle platform guided by AI (TuNa-AI) for further optimization of material recipes and ratios [34].

Characterization and Analysis

Comprehensive characterization of fungal-synthesized MMNPs is essential to ensure their suitability for drug delivery applications. The following table summarizes key characterization techniques and the information they provide:

Table 1: Characterization Techniques for Fungal-Synthesized Multimetallic Nanoparticles

| Technique | Parameters Analyzed | Significance for Drug Delivery |

|---|---|---|

| UV-visible Spectroscopy | Surface plasmon resonance, stability | Confirms nanoparticle formation, composition, and colloidal stability |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Hydrodynamic size, size distribution | Determines particle size critical for biodistribution and cellular uptake |

| Zeta Potential Measurement | Surface charge, colloidal stability | Predicts nanoparticle stability and interaction with biological membranes |

| FTIR Spectroscopy | Functional groups of capping agents | Identifies biomolecules responsible for stabilization and functionalization |

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | Crystalline structure, phase composition | Determines crystallinity and alloy vs. core-shell structure |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Size, morphology, core-shell structure | Visualizes nanoparticle architecture at high resolution |

| Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) | Elemental composition, distribution | Confirms multimetallic composition and distribution of elements |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) | Quantitative elemental analysis | Precisely determines metal composition and concentration |

Applications in Targeted Drug Delivery

Fungal-mediated MMNPs offer significant advantages for drug delivery applications, particularly through their enhanced targeting capabilities and multifunctionality.

Anticancer Drug Delivery

MMNPs demonstrate exceptional potential as carriers for chemotherapeutic agents. The TuNa-AI platform has been used to design nanoparticles that more effectively encapsulate difficult-to-deliver drugs like venetoclax, a chemotherapy agent for leukemia [34]. These optimized nanoparticles showed improved solubility and more effectively halted leukemia cell growth compared to the non-encapsulated drug [34]. In another study, an AI-guided platform reduced the use of a potentially carcinogenic excipient by 75% in a chemotherapy formulation while preserving the drug's efficacy and improving its biodistribution in mouse models [34].

Antifungal Therapeutics

With fungal infections causing approximately 1.6 million deaths annually and increasing antifungal resistance complicating treatment strategies, MMNPs offer novel therapeutic approaches [35]. Nanoparticles can act as direct antifungal agents by disrupting fungal cell walls and generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) [35]. Metallic nanoparticles including silver, copper, and zinc oxide have demonstrated significant antifungal properties through multiple mechanisms:

Table 2: Antifungal Efficacy of Metallic Nanoparticles

| Nanoparticle Type | Target Fungi | Key Findings | Mechanisms of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copper Nanoparticles (CuNPs) | Corticium salmonicolor, Candida tropicalis, Fusarium oxysporum | 76.29% mycelial inhibition of F. oxysporum at 0.24% concentration; 93.98% growth suppression at 450 ppm [36] | Reactive hydroxyl radical formation, cell membrane disruption |

| Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) | Various plant and human pathogens | High efficacy against multiple fungal strains [36] | ROS generation, cell wall structure disruption |

| Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) | Multiple pathogenic fungi | Significant reductions in colony formation for plant pathogenic fungi [37] | Membrane integrity disruption, protein denaturation |

Enhanced Targeting and Biocompatibility

The biological origin of fungal-synthesized MMNPs contributes to their improved biocompatibility, a critical factor for drug delivery applications. The biomolecular capping layer on these nanoparticles not only enhances stability but also provides functional groups that can be modified with targeting ligands for specific tissue or cell recognition [31]. Furthermore, the ability to create MMNPs with responsive properties enables the development of smart drug delivery systems that release their payload in response to specific enzymatic activities or environmental triggers at the target site [38].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Fungal-Mediated Nanoparticle Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fungal Strains (Fusarium oxysporum, Aspergillus niger, Trichoderma longibrachiatum) | Biological factories for nanoparticle synthesis | Select strains based on enzyme secretion profiles and metal tolerance [31] [37] |

| Metal Precursors (AgNO₃, HAuCl₄, ZnCl₂, CuSO₄) | Source of metal ions for nanoparticle formation | Use high-purity grades; concentration typically 1-3 mM in final reaction [31] |

| Culture Media (PDA, MGYP, Sabouraud Dextrose) | Fungal growth and maintenance | Composition affects metabolic activity and subsequent nanoparticle synthesis |

| NADH | Electron donor in enzymatic reduction | Critical for nitrate reductase-mediated metal ion reduction [31] |

| pH Adjusters (NaOH, HCl) | Optimization of synthesis conditions | pH significantly affects nanoparticle size, shape, and stability [33] |

| Robotics-Assisted Liquid Handling Platform | High-throughput screening of synthesis parameters | Enables systematic exploration of parameter space for optimization [34] |

Workflow and Mechanism Diagrams

Fungal-Mediated Synthesis Workflow

Drug Delivery Mechanism Pathways

Surface Functionalization and Ligand Engineering for Cellular Targeting

The efficacy of nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems is critically dependent on their ability to selectively accumulate within target cells while minimizing off-target effects. Surface functionalization and ligand engineering serve as the cornerstone of this selective targeting, transforming nanoparticles from passive carriers into active therapeutic vehicles. These strategies directly modulate the physicochemical interactions at the bio-nano interface, influencing cellular uptake, biodistribution, and ultimately, therapeutic outcomes [39] [1]. By decorating nanoparticle surfaces with specific biological ligands, researchers can exploit the unique molecular signatures of target cells, such as receptor overexpression, to achieve precision medicine goals. This document outlines the core principles, quantitative data, and detailed protocols essential for designing and executing effective surface functionalization strategies for cellular targeting in drug delivery research.

Fundamental Principles and Key Concepts

Mechanisms of Nanoparticle-Cell Interactions

The initial contact and subsequent internalization of nanoparticles by cells are governed by a complex interplay of forces and biological recognition events. A comprehensive understanding of these mechanisms is a prerequisite for rational design.

- Electrostatic Interactions: Charged nanoparticle surfaces interact with oppositely charged components of the cell membrane. The strength of these interactions is highly tunable and depends on environmental factors such as pH and ionic strength. Positively charged surfaces often promote stronger adhesion to the negatively charged cell membrane, enhancing uptake but potentially increasing non-specific interactions and toxicity [39] [1].

- Ligand-Receptor Binding: This is the primary mechanism for active targeting. Ligands conjugated to the nanoparticle surface (e.g., peptides, antibodies, small molecules) specifically bind to receptors that are overexpressed on the surface of target cells. This binding often triggers receptor-mediated endocytosis, leading to efficient and selective cellular internalization [40].

- Protein Corona Formation: Upon intravenous administration, nanoparticles are rapidly coated by a layer of plasma proteins, forming the "protein corona". This corona defines the biological identity of the nanoparticle and can mask surface ligands, thereby altering the intended targeting specificity and cellular interaction pathways. The composition of the hard and soft corona layers is influenced by the nanoparticle's core material, size, and surface chemistry [39] [41].

The Role of Surface Properties in Cellular Uptake

Key physicochemical properties of the nanoparticle surface directly dictate its biological behavior and must be carefully controlled.

Table 1: Impact of Nanoparticle Surface Properties on Cellular Interactions and Biodistribution

| Surface Property | Impact on Cellular Uptake & Biodistribution | Key Considerations for Targeting |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Charge | Positively charged NPs generally show enhanced cellular adhesion and uptake due to electrostatic attraction to anionic cell membranes. Neutral/negative NPs typically have prolonged circulation. | Cationic surfaces may increase toxicity and non-specific binding. Anionic/neutral surfaces benefit from reduced opsonization [39] [1]. |

| Hydrophobicity | Hydrophobic surfaces tend to adsorb more proteins, leading to opsonization and rapid clearance by the Mononuclear Phagocyte System (MPS). | Hydrophilic coatings (e.g., PEG) provide "stealth" properties, reduce protein adsorption, and extend circulation half-life [39] [1]. |

| Ligand Density & Orientation | Optimal ligand density is critical; too low results in weak binding, while too high can hinder internalization or cause non-specific binding. Proper orientation maintains ligand activity. | Requires precise control during conjugation chemistry. Density can be optimized to trigger specific mechanotransduction signaling in immune cells like T cells [40]. |

Quantitative Data and Performance Metrics

Evaluating the success of a functionalization strategy requires quantitative assessment of both physicochemical attributes and biological performance. The following data, synthesized from literature, provides benchmark values for researchers.

Table 2: Quantitative Biodistribution Coefficients (% Injected Dose per Gram) of Nanoparticles in Mouse Models [42]

| Organ/Tissue | Mean NBC (%ID/g) | Notes on Variability |

|---|---|---|

| Liver | 17.56 | High variability; primary organ of the RES/MPS. |

| Spleen | 12.10 | High variability; secondary RES organ. |

| Tumor | 3.40 | Highly dependent on EPR effect and active targeting. |

| Kidneys | 3.10 | Site of excretion for small NPs (<10 nm). |

| Lungs | 2.80 | Can accumulate larger or aggregated NPs. |

| Intestine | 1.80 | Related to hepatobiliary excretion. |

| Heart | 1.80 | Generally low accumulation. |

| Stomach | 1.20 | -- |

| Pancreas | 1.20 | -- |

| Skin | 1.00 | -- |

| Bone | 0.90 | -- |

| Muscle | 0.60 | -- |

| Brain | 0.30 | Protected by the blood-brain barrier (BBB). |

Interpretation: The high accumulation in the liver and spleen highlights the significant challenge posed by the MPS. Effective surface functionalization, particularly with stealth coatings like PEG, aims to reduce these NBC values in clearance organs and enhance them in target tissues like tumors. The low baseline NBC in the brain underscores the necessity of advanced targeting ligands (e.g., g7 peptide) for central nervous system delivery [42] [41].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Covalent Amine Functionalization of PLGA Nanoparticles using EDC/NHS Chemistry

This protocol describes a standard method for conjugating carboxyl-containing ligands (e.g., antibodies, peptides) to amine-functionalized polymeric nanoparticles.

1. Reagent Setup

- NP Suspension: Polymeric nanoparticles (e.g., PLGA-NHâ‚‚) suspended in MES buffer (0.1 M, pH 6.0).

- Activation Reagents: EDC (1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) and NHS (N-hydroxysuccinimide), freshly prepared in cold MES buffer.

- Ligand Solution: Target ligand (e.g., anti-EGFR antibody, RGD peptide) dissolved in a compatible, amine-free buffer (e.g., PBS).

- Quenching Solution: 1 M hydroxylamine or 100 mM glycine solution.

- Purification Buffers: PBS (pH 7.4) or Tris buffer for final storage.

2. Step-by-Step Procedure 1. Activation of Carboxyl Groups: Transfer 1 mL of NP suspension (1-5 mg/mL) to a clean microcentrifuge tube. Add EDC solution to a final concentration of 2 mM and NHS to a final concentration of 5 mM. React for 15 minutes on a rotator at room temperature. 2. Purification of Activated NPs: Separate the activated NPs from excess EDC/NHS by gel filtration (e.g., using a Sephadex G-25 column) or centrifugal filtration (e.g., 100 kDa MWCO Amicon filters). Elute or wash with MES buffer (pH 6.0). Critical Step: Proceed quickly to the next step as the activated ester is unstable. 3. Ligand Conjugation: Immediately add the ligand solution to the purified, activated NPs. The molar ratio of ligand to NP should be determined empirically (a 50:1 to 100:1 ratio is a common starting point). Allow the reaction to proceed for 2-4 hours at room temperature on a rotator. 4. Quenching: Terminate the reaction by adding a quenching solution (e.g., 10 μL of 1 M hydroxylamine) and incubating for 10 minutes. This step deactivates any remaining activated esters. 5. Purification of Conjugated NPs: Purify the ligand-conjugated NPs from unreacted ligand via extensive dialysis (against PBS, pH 7.4) or centrifugal filtration. Perform 3-4 wash cycles. 6. Characterization: Determine the ligand conjugation efficiency using a BCA assay for proteins, or HPLC for small molecules. Confirm surface modification by measuring the zeta potential shift and by using techniques like SDS-PAGE or immunoassays.

Protocol: Analyzing Protein Corona Formation on Functionalized Nanoparticles

Understanding the protein corona is vital for predicting the in vivo behavior of targeted nanoparticles.

1. Reagent Setup

- NP Suspension: Functionalized nanoparticles (1 mg/mL) in PBS.

- Human Plasma: Commercially sourced, K2EDTA-treated human plasma.

- Purification Buffers: PBS or 150 mM ammonium acetate, pH 7.4.

- Lysis & Digestion Buffers: RIPA buffer, Trypsin/Lys-C mix, and other reagents for proteomic sample preparation.

2. Step-by-Step Procedure 1. Incubation: Mix 100 μL of NP suspension with 900 μL of human plasma (or 100% plasma, depending on the desired dilution). Incubate the mixture at 37°C for 1 hour with gentle agitation to mimic physiological conditions. 2. Isolation of Hard Corona (HC): - Centrifuge the NP-protein corona complex at high speed (e.g., 21,000 x g for 30 minutes) to form a pellet. - Carefully remove the plasma supernatant. - Wash the pellet gently but thoroughly with 1 mL of cold PBS to remove loosely associated proteins. Centrifuge again and discard the wash. Repeat this wash step 3 times. - The resulting pellet contains the NPs with the Hard Corona. 3. Isolation of Soft Corona (SC): - The initial plasma supernatant and the combined wash buffers from the HC isolation contain the Soft Corona proteins. These can be concentrated using centrifugal filters (e.g., 3 kDa MWCO) for analysis. 4. Protein Elution and Digestion: Resuspend the HC pellet in a strong denaturing and elution buffer (e.g., 2% SDS in RIPA buffer). Vortex and sonicate to dissociate proteins from the NP surface. Transfer the eluate to a new tube, leaving the NPs behind. Reduce, alkylate, and digest the proteins (both HC and SC fractions) with trypsin using standard proteomic protocols. 5. Analysis: Analyze the digested peptides using Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Identify and quantify the proteins present in the HC and SC using relevant database search software (e.g., MaxQuant). Compare the corona profiles of non-functionalized and ligand-functionalized NPs to assess the impact of surface engineering [41].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key steps involved in the ligand conjugation and subsequent corona analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful surface functionalization requires a suite of reliable reagents and materials. The following table lists key solutions used in the featured protocols and the broader field.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Surface Functionalization and Targeting Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| EDC & NHS | Carbodiimide crosslinkers for catalyzing amide bond formation between carboxyl and amine groups. | Covalent conjugation of antibodies or peptides to nanoparticle surfaces [39]. |

| Maleimide Crosslinkers | Reacts specifically with thiol (-SH) groups. Enables site-specific conjugation. | Coupling thiolated ligands (e.g., cysteine-containing peptides) to maleimide-activated nanoparticles. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A hydrophilic polymer used for "PEGylation". Provides stealth properties by reducing protein adsorption and MPS clearance. | Coating nanoparticles to extend circulation half-life and improve bioavailability [4] [1]. |

| Targeting Ligands (e.g., RGD peptide, g7 peptide) | Biological molecules that bind specifically to receptors on target cells. | RGD for targeting αvβ3 integrin on tumor vasculature; g7 peptide for enhancing blood-brain barrier penetration [40] [41]. |

| PLGA polymer | A biocompatible and FDA-approved copolymer used to form the nanoparticle matrix. | Forming the core of polymeric nanoparticles for drug encapsulation [41]. |

| Cholesterol | A natural lipid used to formulate or hybridize nanoparticles to improve stability and membrane interactions. | Core component of lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and hybrid PLGA-Chol systems [41]. |

| Boc-PEG2-ethoxyethane-PEG2-benzyl | Boc-PEG2-ethoxyethane-PEG2-benzyl, MF:C25H42O7, MW:454.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| FmocNH-PEG4-t-butyl acetate | FmocNH-PEG4-t-butyl acetate, MF:C29H39NO8, MW:529.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualization of Signaling Pathways in Targeted Delivery

The specific binding of a surface-engineered nanoparticle to its cellular receptor initiates a cascade of intracellular events that lead to internalization. The following diagram illustrates a generalized pathway for receptor-mediated endocytosis, a common mechanism for ligand-functionalized nanoparticles.