Molecular Biology Techniques for Biomaterial Biocompatibility Testing: A Guide for Researchers

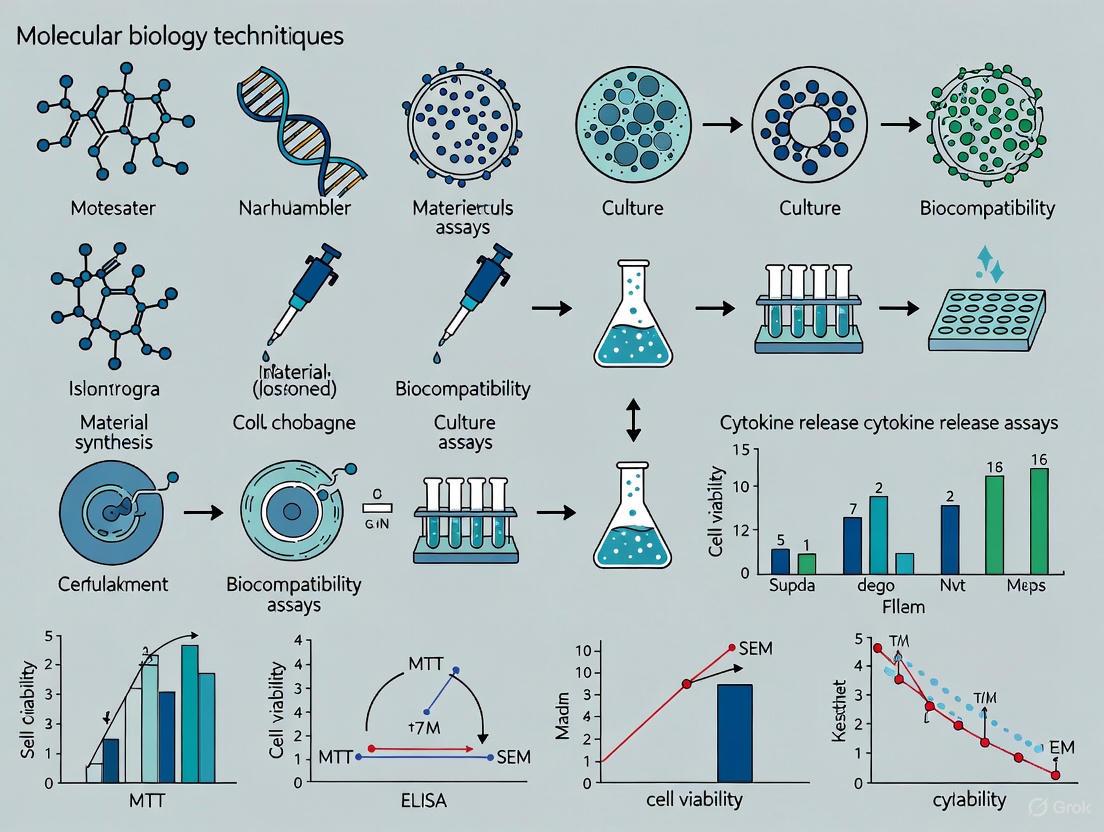

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the application of molecular biology techniques in biomaterial biocompatibility testing.

Molecular Biology Techniques for Biomaterial Biocompatibility Testing: A Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the application of molecular biology techniques in biomaterial biocompatibility testing. It covers the foundational principles of biocompatibility, explores key methodological approaches like PCR, recombinant DNA technology, and immunohistochemistry, and addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges. The content also outlines strategies for test validation and comparative analysis within regulatory frameworks, such as ISO 10993, to ensure the development of safe and effective medical devices and implants.

Understanding Biocompatibility: From Bio-inertia to Biofunctionality

Biocompatibility has undergone a significant conceptual evolution, moving from a passive definition focused merely on the "absence of toxic or injurious effects" toward a dynamic paradigm that emphasizes positive biofunctionality and appropriate host response [1]. The modern definition, widely attributed to Williams, describes biocompatibility as "the ability of a material to perform with an appropriate host response in a specific application" [1]. This shift acknowledges that an ideal biomaterial is not simply inert but actively interacts with the biological system to promote the desired therapeutic outcome, whether it be tissue integration, regeneration, or sustained drug delivery [1] [2].

This evolution places molecular biology techniques at the forefront of biocompatibility assessment. Where traditional testing primarily evaluated gross cytotoxicity, modern approaches require probing the intricate molecular dialogues between biomaterials and cells or tissues [3]. Understanding these interactions—how a material influences gene expression, protein synthesis, and cellular behaviors like proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis—is now fundamental to establishing both the safety and efficacy of a new biomaterial [3] [4].

A Quantitative Framework for Biocompatibility Assessment

Moving beyond qualitative observations, the field is increasingly adopting quantitative metrics to objectively compare scaffold performance. One advanced approach involves the geometric analysis of explants to quantify the foreign body response.

Table 1: Quantitative Metrics for In Vivo Biocompatibility Assessment

| Metric | Description | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Encapsulation Thickness | Measurement of the fibrous capsule layer surrounding the implanted material. | A thinner, consistent capsule indicates a lower chronic inflammatory response and better integration [5]. |

| Cross-sectional Area | Analysis of the explanted scaffold's area compared to its original dimensions. | Helps assess the in vivo structural stability, swelling behavior, or degradation rate of the biomaterial [5]. |

| Ovalization | Degree of circular deformation of a cylindrical implant post-explantation. | Serves as an indicator of structural integrity and the uniformity of mechanical forces exerted by the host tissue [5]. |

These quantitative methods provide a more complete and objective comparison of scaffolds with differing compositions and architectures, complementing traditional histopathological scores [5].

Essential Molecular Biology Techniques and Protocols

Molecular biology techniques are indispensable for decoding the mechanisms behind a material's biocompatibility. The following section details key methodologies for evaluating gene and protein expression relevant to inflammatory and regenerative responses.

Protocol: Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) for Inflammatory Marker Profiling

Objective: To quantify the expression levels of mRNA encoding key cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10) in cells cultured on a test biomaterial versus a control surface.

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents:

- Cells: Relevant cell line (e.g., macrophages, fibroblasts).

- Test Biomaterial: Sterilized scaffolds or material samples.

- RNA Extraction Kit: e.g., phenol-guanidine-based kits.

- Reverse Transcription Kit: Includes reverse transcriptase, dNTPs, random hexamers/oligo(dT).

- qPCR Master Mix: Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, and fluorescent dye (e.g., SYBR Green).

- Primers: Validated, sequence-specific forward and reverse primers for target and housekeeping genes.

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding and Culture: Seed cells at a defined density onto the test biomaterial and a control substrate (e.g., tissue culture plastic). Culture for a predetermined period.

- RNA Extraction: Lyse cells directly on the material. Extract total RNA according to the manufacturer's protocol. Treat samples with DNase to remove genomic DNA contamination.

- RNA Quantification: Measure RNA concentration and assess purity (A260/A280 ratio ~2.0) using a spectrophotometer.

- Reverse Transcription: Convert equal amounts of total RNA (e.g., 1 µg) into complementary DNA (cDNA) using the reverse transcription kit.

- qPCR Setup: Prepare reactions containing qPCR master mix, gene-specific primers, and cDNA template. Run samples in technical replicates.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the cycle threshold (Ct) for each reaction. Normalize the Ct of the target gene to a housekeeping gene (e.g., GAPDH, β-actin) to obtain ΔCt. Compare ΔCt between test and control groups using the ΔΔCt method to determine the relative fold-change in gene expression.

Protocol: Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for Protein Localization

Objective: To detect and visualize the spatial distribution of specific proteins (e.g., collagen I, CD31, α-SMA) in tissue sections surrounding an implanted biomaterial.

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents:

- Tissue Sections: Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections of the explanted biomaterial and surrounding tissue.

- Primary Antibody: Monoclonal or polyclonal antibody against the protein of interest.

- Secondary Antibody: Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibody specific to the host species of the primary antibody.

- Antigen Retrieval Buffer: Citrate or EDTA-based buffer, pH 6.0 or 9.0.

- Blocking Solution: Serum or protein (e.g., BSA) from the same species as the secondary antibody.

- Chromogen: 3,3'-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate, which produces a brown precipitate.

- Counterstain: Hematoxylin.

Procedure:

- Sectioning and Deparaffinization: Cut FFPE blocks into 4-5 µm thick sections. Deparaffinize in xylene and rehydrate through a graded series of ethanol to water.

- Antigen Retrieval: Heat slides in antigen retrieval buffer using a pressure cooker or microwave to unmask epitopes crosslinked by formalin.

- Blocking and Staining:

- Block endogenous peroxidase activity by incubating with 3% Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚.

- Block non-specific binding with an appropriate blocking solution.

- Incubate sections with the optimized dilution of primary antibody in a humidified chamber.

- Wash and apply the enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody.

- Detection: Apply the DAB chromogen solution until the desired stain intensity develops. Rinse to stop the reaction.

- Counterstaining and Mounting: Counterstain with hematoxylin to visualize nuclei. Dehydrate sections, clear in xylene, and mount with a permanent mounting medium.

- Analysis: Examine slides under a light microscope. Positive staining is indicated by a brown precipitate at the site of the target antigen.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful biocompatibility testing relies on a suite of reliable reagents and tools.

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Molecular Biocompatibility Testing

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| EDC-NHS Crosslinking Kit | Chemically crosslinks collagen and other biopolymers to enhance mechanical stability and control degradation rate. | Fabrication of stable, freeze-cast bovine collagen scaffolds for subcutaneous implantation studies [5]. |

| SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix | Fluorescent dye that binds double-stranded DNA, allowing real-time quantification of PCR products. | Profiling pro-inflammatory (IL-6) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10) cytokine mRNA levels in macrophage-biomaterial co-cultures. |

| Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedding (FFPE) Kit | Preserves tissue architecture for long-term storage and enables high-quality sectioning for histology. | Preparation of explanted scaffold-tissue constructs for histological analysis (H&E staining) and IHC [5]. |

| DAB Chromogen Kit | Enzyme substrate producing an insoluble, visible brown precipitate at the site of antibody binding. | Visualizing the deposition of key extracellular matrix proteins like Collagen I in tissue sections via IHC. |

| Protein-Specific Validated Antibodies | Primary antibodies for detecting and localizing specific proteins of interest in cells and tissues. | IHC staining for CD31 to identify endothelial cells and quantify capillary formation within a scaffold (angiogenesis). |

| (-)-Menthyloxyacetic acid | (-)-Menthyloxyacetic acid, CAS:40248-63-3, MF:C12H22O3, MW:214.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2'-Deoxycytidine hydrate | 2'-Deoxycytidine hydrate, CAS:652157-52-3, MF:C9H15N3O5, MW:245.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The modern definition of biocompatibility demands an integrated, multi-faceted evaluation strategy. It is no longer sufficient to demonstrate that a material is non-toxic; it must be shown to perform its intended function by eliciting an appropriate host response. This requires the synergistic application of quantitative in vivo metrics and sensitive molecular biology techniques. By adopting this comprehensive framework, researchers can transition from simply assessing the passive absence of harm to actively engineering advanced, bioactive biomaterials that predictably and successfully integrate with the biological system to achieve defined clinical goals.

The Role of Molecular Biology in Assessing Host Response

The implantation of any biomaterial or medical device triggers a complex series of host responses that ultimately determine clinical success or failure. Molecular biology techniques provide powerful tools for deciphering these biological reactions at the cellular and molecular level, moving beyond traditional histological evaluation to enable precise mechanistic understanding [6]. As the field of biomaterials advances, the focus has shifted from merely assessing bio-inertness to actively promoting bioactivity and tissue integration [7]. This evolution demands sophisticated analytical approaches that can characterize the nuanced interplay between implanted materials and the host immune system, facilitating the development of next-generation biomaterials with enhanced biocompatibility and functionality.

The host response to biomaterials encompasses a well-orchestrated sequence of events, beginning with protein adsorption and initiating through foreign body reaction (FBR) that can culminate in fibrosis and isolation of the implant [6]. Molecular techniques now allow researchers to probe deeper into these processes, examining specific signaling pathways, cytokine profiles, and cellular differentiation patterns that dictate whether a biomaterial will be tolerated, integrated, or rejected. This application note details current molecular biology protocols for comprehensive host response assessment, providing researchers with standardized methodologies for evaluating biomaterial biocompatibility.

Key Biological Responses to Biomaterials

Sequential Host Response Phases

The implantation of biomaterials initiates a cascade of biological events that occur in sequential yet overlapping phases [8] [6]. Understanding these phases is fundamental to designing appropriate assessment protocols.

Table 1: Sequential Phases of Host Response to Biomaterials

| Time Post-Implantation | Phase | Key Cellular Players | Molecular Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minutes to hours | Protein adsorption & acute inflammation | Plasma proteins, mast cells, polymorphonuclear leukocytes | Complement factors, TNF-α, IL-1β |

| Hours to days | Chronic inflammation & macrophage activation | Monocytes/macrophages, lymphocytes | IL-4, IL-13, IL-10, TGF-β |

| 4-7 days | Foreign body reaction & giant cell formation | Macrophages, fibroblasts, foreign body giant cells | Fusion receptors (DC-STAMP, MFR), fibronectin |

| Weeks to months | Fibrous encapsulation & tissue remodeling | Fibroblasts, endothelial cells | Collagen I/III, MMPs, TIMPs, VEGF |

The foreign body reaction represents a critical determinant of long-term implant success, typically resulting in collagenous encapsulation that isolates the device from surrounding tissues [6]. Molecular assessment techniques enable researchers to characterize each phase with precision, identifying potential intervention points for modulating the host response toward favorable outcomes.

Macrophage Polarization in Immune Response

Macrophages play a pivotal role in determining the fate of implanted biomaterials, demonstrating remarkable plasticity that enables them to adopt different functional phenotypes in response to microenvironmental cues [8]. The M1/M2 macrophage paradigm represents a crucial framework for understanding host response dynamics.

Diagram 1: Macrophage polarization pathways in host response. Bioactive materials promote M2 pro-healing phenotypes, while inert materials often trigger M1 pro-inflammatory responses.

Studies have demonstrated that biomaterial surface properties directly influence macrophage polarization. For instance, polycaprolactone (PCL) scaffolds with modified surfaces promoted a higher prevalence of M2 macrophages, accompanied by increased angiogenic factors like VEGF, reduced pro-inflammatory chemokines, and decreased fibrous capsule formation [8]. Molecular techniques that characterize macrophage polarization provide critical insights into a biomaterial's immunomodulatory potential.

Molecular Assessment Techniques

Proteomic Approaches for Biocompatibility Assessment

High-throughput proteomics has revolutionized biocompatibility assessment by enabling comprehensive analysis of protein expression changes in response to biomaterials [6]. These approaches move beyond single-protein analysis to provide systems-level understanding of host responses.

Table 2: Proteomic Techniques for Host Response Assessment

| Technique | Principle | Application in Host Response | Throughput | Key Readouts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Microarrays | Immobilized antibodies or antigens for multiplexed detection | Cytokine/chemokine profiling, signaling pathway analysis | High | Simultaneous measurement of 100+ proteins |

| Mass Spectrometry (DDA/DIA) | LC-MS/MS with data-dependent or independent acquisition | Global proteome changes, protein corona characterization | Very High | Identification and quantification of 1000+ proteins |

| Targeted Proteomics (PRM/SRM) | Selective monitoring of predefined peptides | Validation of candidate biomarkers, precise quantification | Medium | Accurate measurement of specific proteins |

| Western Blot/ELISA | Gel electrophoresis & immunodetection | Validation of specific protein targets | Low | Confirmation of protein identity and quantity |

Functional proteomics explores protein functions, intracellular signaling pathways, and protein-protein interactions, providing mechanistic insights into host responses [6]. For example, protein microarrays can identify specific cytokines and growth factors involved in the foreign body reaction, while mass spectrometry techniques characterize the protein corona that forms immediately on biomaterial surfaces, influencing subsequent immune recognition.

Molecular Biology Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Protein Corona Characterization via Mass Spectrometry

Purpose: To identify and quantify proteins adsorbed onto biomaterial surfaces following implantation or in vitro exposure to biological fluids.

Materials:

- Test biomaterial (nanoparticles, implant surfaces, or scaffolds)

- Biological fluid (serum, plasma, or simulated body fluid)

- Lysis buffer (1% SDS, 50mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0)

- Protease and phosphatase inhibitors

- Trypsin/Lys-C mix for protein digestion

- C18 desalting columns

- LC-MS/MS system

Procedure:

- Incubation: Incubate biomaterial with selected biological fluid (1:10 ratio) for predetermined timepoints (30min, 2h, 24h) at 37°C with gentle agitation.

- Protein Elution: Centrifuge and carefully remove biomaterial. Wash twice with PBS to remove loosely associated proteins. Elute tightly bound proteins using 1% SDS lysis buffer with protease inhibitors.

- Protein Digestion: Reduce proteins with 5mM DTT (30min, 60°C), alkylate with 15mM iodoacetamide (30min, room temperature in dark), and digest with Trypsin/Lys-C mix (1:50 enzyme:protein) overnight at 37°C.

- Peptide Cleanup: Acidify digest with 1% trifluoroacetic acid and desalt using C18 columns according to manufacturer's instructions.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Reconstitute peptides in 0.1% formic acid and analyze by nano-LC-MS/MS using 120min gradient. Operate mass spectrometer in data-independent acquisition (DIA) mode for comprehensive peptide detection.

- Data Analysis: Process raw files using specialized software (e.g., DIA-NN, Spectronaut) against appropriate protein databases. Quantify protein abundance using peak area or spectral counting methods.

Quality Control: Include reference materials with known adsorption profiles, process blanks (no biomaterial) alongside samples, and perform technical replicates to ensure reproducibility.

Protocol 2: Multiplex Cytokine Profiling of Macrophage-Biomaterial Interactions

Purpose: To simultaneously quantify multiple cytokines and chemokines released during immune cell responses to biomaterials.

Materials:

- Primary human macrophages or macrophage cell lines

- Test biomaterials in appropriate formats (films, particles, scaffolds)

- Multiplex cytokine assay kit (Luminex-based or electrochemiluminescence)

- Cell culture reagents and equipment

- Plate reader capable of detecting luminescence or fluorescence

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Stimulation: Differentiate monocytes to macrophages (7 days with M-CSF). Seed macrophages at 2×10^5 cells/well in 24-well plates. Expose to test biomaterials at clinically relevant concentrations for 6h, 24h, and 48h.

- Supernatant Collection: Centrifuge culture plates at 300×g for 5min and carefully collect supernatants without disturbing cells or biomaterials. Store at -80°C until analysis.

- Multiplex Assay Preparation: Thaw samples on ice and clarify by centrifugation. Prepare standards according to kit instructions using serial dilutions.

- Assay Procedure: Add samples and standards to assay plates pre-coated with capture antibodies. Incubate overnight at 4°C with shaking. Wash plates, add biotinylated detection antibody mixture, and incubate for 1h at room temperature. After washing, add streptavidin-phycoerythrin and incubate for 30min.

- Detection and Analysis: Wash plates and read on appropriate multiplex array reader. Generate standard curves for each analyte and calculate sample concentrations using instrument software.

- Data Interpretation: Analyze patterns of M1 (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12) versus M2 (IL-10, TGF-β, CCL17, CCL22) cytokines to determine macrophage polarization state.

Troubleshooting: Check for matrix effects by spiking recovery standards, ensure samples fall within linear range of standard curve, and verify assay reproducibility with quality control samples.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Host Response Assessment

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Host Response Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Systems | Primary human macrophages, THP-1 cell line, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) | Provide biologically relevant models for immune cell-biomaterial interactions |

| Cytokine Detection Kits | Luminex multiplex panels, ELISA kits, electrochemiluminescence arrays | Enable quantification of key inflammatory and regulatory mediators |

| Protein Analysis Reagents | RIPA buffer, protease inhibitors, BCA protein assay kits, SDS-PAGE reagents | Facilitate protein extraction, quantification, and separation for downstream analysis |

| Molecular Biology Kits | RNA extraction kits, cDNA synthesis kits, qPCR master mixes, Western blot reagents | Support gene expression analysis and protein detection at molecular level |

| Proteomics Consumables | Trypsin/Lys-C, C18 desalting columns, TMT labels, LC-MS grade solvents | Enable sample preparation for mass spectrometry-based proteomic analysis |

| Immunofluorescence Reagents | Primary antibodies (CD68, iNOS, CD206), fluorescent secondary antibodies, mounting media with DAPI | Allow visualization and localization of specific cell types and markers in tissue sections |

| 6-Aza-2'-deoxyuridine | 6-Aza-2'-deoxyuridine, CAS:20500-29-2, MF:C8H11N3O5, MW:229.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Methyl Green zinc chloride | Methyl Green zinc chloride, CAS:36148-59-1, MF:C26H33N3Zn+4, MW:452.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Workflow: Integrated Molecular Assessment

A comprehensive molecular assessment of host response requires integration of multiple techniques to build a complete picture of biomaterial-immune system interactions.

Diagram 2: Integrated workflow for comprehensive molecular assessment of host response to biomaterials, combining multiple analytical approaches.

This integrated workflow begins with characterization of the initial protein layer that forms on the biomaterial surface, proceeds through detailed analysis of cellular responses, and culminates in signaling pathway investigation. Data integration across these domains enables identification of key biomarkers predictive of clinical outcomes and facilitates development of biomaterials with optimized immunocompatibility.

Molecular biology techniques have transformed our ability to assess host responses to biomaterials, providing unprecedented resolution into the cellular and molecular events that determine implant success. The protocols and methodologies detailed in this application note empower researchers to move beyond descriptive biocompatibility assessment toward mechanistic understanding of host-material interactions. As the field advances, integration of these molecular approaches with materials science and computational modeling will accelerate the development of precision biomaterials engineered to elicit specific, favorable immune responses tailored to clinical applications.

The growing emphasis on immunomodulatory biomaterials underscores the importance of sophisticated molecular assessment techniques that can characterize macrophage polarization, cytokine networks, and signaling pathways with precision and throughput. By adopting these standardized protocols, researchers can generate comparable, reproducible data across studies, advancing the collective goal of developing biomaterials that seamlessly integrate with host tissues and promote optimal healing outcomes.

The biocompatibility of a biomaterial is fundamentally determined by a series of highly orchestrated cellular and molecular interactions that occur at the material-tissue interface. Upon implantation, a biomaterial triggers an immediate foreign body reaction (FBR), a specialized inflammatory response that dictates subsequent healing and integration outcomes [6]. The ultimate clinical success of medical devices, implants, and tissue engineering scaffolds depends on the delicate balance between pro-inflammatory and pro-healing processes.

This document details the key molecular players, signaling pathways, and cellular behaviors in inflammation, tissue integration, and immunogenicity. It provides application notes and standardized experimental protocols to quantify these interactions, equipping researchers with the tools to systematically evaluate and improve biomaterial design within a molecular biology framework.

The Foreign Body Reaction and Molecular Signaling

The Foreign Body Reaction (FBR) is a sequential, immune-mediated process initiated the moment a biomaterial contacts biological fluids [6]. Understanding its phases is crucial for biocompatibility assessment.

Phases of the Foreign Body Reaction

The following diagram illustrates the key stages and cellular players in the Foreign Body Reaction (FBR).

Key Signaling Pathways in the FBR

The following diagram summarizes the major signaling pathways that drive macrophage polarization during the Foreign Body Reaction.

Application Notes: Quantifying Key Interactions

This section provides standardized methods and quantitative frameworks for analyzing critical biomaterial-cell interactions. The data collected using these methods should be summarized using descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation) to characterize central tendency and dispersion, and inferential statistics (t-tests, ANOVA) to determine the significance of observed differences between test materials and controls [9] [10].

Quantitative Analysis of Cytokine Secretion

Cytokine profiling is essential for classifying the immune response. A pro-inflammatory profile (high TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) indicates a classical M1 macrophage activation, while a pro-healing profile (high IL-10, TGF-β) suggests alternative M2 activation [6]. Data should be collected over multiple time points (e.g., 6, 24, 48, 72 hours) to track response dynamics.

Table 1: Key Cytokine Targets and Their Implications in Biocompatibility

| Cytokine | Primary Cell Source | Receptor | Key Signaling Pathway | Biological Effect in FBR | Implication for Biomaterials |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | M1 Macrophages, Mast Cells | TNFR1/2 | NF-κB, MAPK | Promotes acute inflammation; enhances leukocyte adhesion and migration. | High levels indicate strong pro-inflammatory response and potential tissue damage. |

| IL-1β | M1 Macrophages | IL-1R | NF-κB, MAPK | Pyrogen; promotes endothelial activation and chemokine production. | Sustained expression is linked to chronic inflammation and implant failure. |

| IL-6 | M1 Macrophages, Fibroblasts | IL-6R | JAK/STAT | Drives acute phase response; promotes B and T cell activation. | Marker for ongoing inflammatory activity. |

| IL-4 | Th2 Cells, Eosinophils | IL-4R | JAK/STAT6 | Induces macrophage polarization to M2 phenotype. | High early levels may predict better integration and reduced fibrosis. |

| IL-10 | M2 Macrophages, Tregs | IL-10R | JAK/STAT3 | Potent anti-inflammatory; suppresses M1 cytokine production. | Critical for resolving inflammation and promoting tissue repair. |

| TGF-β | M2 Macrophages, Platelets | TGF-βR | Smad | Stimulates fibroblast proliferation and collagen production. | Essential for wound healing; overproduction leads to fibrous encapsulation. |

Quantifying Cell-Material Interactions

Cellular responses to a biomaterial surface—including adhesion, migration, proliferation, and apoptosis—are direct indicators of its biocompatibility. These responses are highly influenced by surface properties like wettability, topography, and chemistry [11]. For instance, surfaces modified to be hydrophilic ("Line" patterns) promote cell adhesion and spreading, while hydrophobic ("Grid" patterns) may exhibit cell-repellent properties [11].

Table 2: Assays for Quantifying Cell-Material Interactions

| Cellular Process | Standard Assay | Quantifiable Readout | Key Molecular Targets / Stains | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adhesion | Fluorescence Microscopy | Cell count per area, Focal adhesion size & number | Vinculin, Actin (Phalloidin), Paxillin, Integrins (e.g., αvβ3) | Standardize seeding density and adhesion time (e.g., 4 hours) [11]. |

| Proliferation | Colorimetric Assay (e.g., MTT) | Metabolic activity, Normalized to time-zero | BrdU/EdU incorporation, Ki67 staining | Conduct over multiple days (1, 3, 7 days); ensure linear range of assay. |

| Apoptosis | Flow Cytometry | % Apoptotic/Necrotic Cells | Annexin V, Propidium Iodide, Caspase-3/7 activity | Use positive controls (e.g., staurosporine). Distinguish early/late apoptosis. |

| Migration | Scratch/Wound Assay | Wound closure rate over time | Time-lapse imaging, Cell tracker dyes | Ensure uniform "scratch"; use serum-free media to isolate migration from proliferation. |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed, step-by-step protocols for key experiments in biomaterial biocompatibility testing.

Protocol: In Vitro Macrophage Polarization and Cytokine Profiling

Objective: To evaluate the immunomodulatory potential of a biomaterial by characterizing the cytokine secretion profile and cell surface markers of interacting macrophages.

Principle: This protocol uses human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) cultured with biomaterial extracts or directly on the material surface. The macrophage polarization state is determined by quantifying signature cytokines in the supernatant and analyzing cell surface markers via flow cytometry.

The Scientist's Toolkit:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Human Monocytes: Isolated from PBMCs using CD14+ magnetic beads.

- Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor (M-CSF): Differentiates monocytes into naïve M0 macrophages.

- Polarizing Cytokines: IFN-γ + LPS (for M1), IL-4 (for M2) as experimental controls.

- ELISA or Luminex Kits: For quantifying TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, and TGF-β.

- Flow Cytometry Antibodies: Anti-CD86 (M1 marker), Anti-CD206 (M2 marker), Anti-CD80, Anti-HLA-DR.

- Cell Culture Media: RPMI-1640 or DMEM supplemented with FBS, L-Glutamine, and Penicillin/Streptomycin.

Methodology:

- Monocyte Isolation and Differentiation: Isolate CD14+ monocytes from human buffy coats or leukopaks using positive selection. Culture 5.0 × 10^5 cells/mL in complete media supplemented with 50 ng/mL M-CSF for 7 days to differentiate into M0 macrophages. Refresh media with M-CSF every 2-3 days.

- Sample Preparation:

- Extract Method: Incubate sterile biomaterial in complete culture media at a surface area-to-volume ratio of 3 cm²/mL or 0.1 g/mL for 24-72 hours at 37°C. Use the extract as the test media.

- Direct Contact Method: Seed M0 macrophages directly onto sterile, flat biomaterial samples placed in a multi-well plate.

- Stimulation and Harvest: Seed M0 macrophages and treat with:

- Group 1 (M0 Control): Complete media only.

- Group 2 (M1 Positive Control): Complete media with 20 ng/mL IFN-γ + 100 ng/mL LPS.

- Group 3 (M2 Positive Control): Complete media with 20 ng/mL IL-4.

- Group 4 (Test Group): Biomaterial extract or direct contact. Incubate for 24-48 hours.

- Analysis:

- Cytokine Quantification: Collect cell culture supernatants. Centrifuge to remove debris. Analyze cytokine levels using commercial ELISA or multiplex bead arrays according to manufacturer instructions. Perform assays in triplicate.

- Phenotypic Characterization (Flow Cytometry): Gently scrape and harvest cells. Stain with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against CD86 and CD206 (and other markers of interest) for 30 minutes on ice. Wash, resuspend in buffer, and analyze on a flow cytometer. Use unstained and isotype controls for gating.

Protocol: Analysis of Cell Adhesion and Spreading on Modified Surfaces

Objective: To quantitatively assess how biomaterial surface topography and chemistry influence initial cell adhesion and cytoskeletal organization.

Principle: Human gingival fibroblasts (HGFs) or other relevant cell lines are cultured on test surfaces. After a short period, cells are fixed, stained for focal adhesion complexes and actin cytoskeleton, and visualized using fluorescence microscopy to quantify adhesion metrics [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Test Surfaces: Biomaterials with defined surface modifications (e.g., HFLS-generated 'Line' and 'Grid' patterns) [11].

- Fluorescent Dyes: Phalloidin (stains F-actin), DAPI (stains nuclei).

- Primary Antibodies: Anti-vinculin antibody (labels focal adhesions).

- Secondary Antibodies: Alexa Fluor-conjugated antibodies (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488).

- Fixation and Permeabilization Reagents: 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA), 0.5% Triton X-100.

- Blocking Buffer: 2% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) in PBS.

Methodology:

- Surface Preparation and Sterilization: Sterilize biomaterial samples (e.g., "None," "Line," "Grid") using UV irradiation or 70% ethanol wash, followed by PBS rinse.

- Cell Seeding: Seed Human Gingival Fibroblasts (HGFs) at a density of 1.0 × 10^4 cells/cm² onto the test surfaces in a multi-well plate. Allow cells to adhere for 4 hours in a CO2 incubator at 37°C [11].

- Fixation and Permeabilization: Aspirate media and gently wash cells twice with pre-warmed PBS. Fix cells with 4% PFA for 15 minutes at room temperature. Permeabilize cells with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes.

- Immunofluorescence Staining:

- Blocking: Incubate samples with 2% BSA in PBS for 30 minutes to block non-specific binding.

- Primary Antibody: Incubate with anti-vinculin antibody (diluted 1:50 in blocking buffer) for 1 hour at room temperature or overnight at 4°C.

- Washing: Wash three times with PBS for 5 minutes each.

- Secondary Antibody & Stains: Incubate with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1000) and Rhodamine-phalloidin (for F-actin, 2.88 µg/mL) for 1 hour in the dark.

- Nuclear Stain: Wash and mount with a mounting medium containing DAPI.

- Image Acquisition and Quantitative Analysis: Acquire images using a fluorescence microscope with a 40x or 60x objective. Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ) to quantify:

- Adhesion Density: Number of DAPI-stained nuclei per unit area.

- Spreading Area: Average cell area based on F-actin staining.

- Focal Adhesion Count & Size: Number and average area of vinculin-positive patches per cell.

The workflow for this protocol, from surface preparation to quantitative analysis, is outlined below.

Advanced Proteomic Techniques for Immunogenicity Screening

Modern biocompatibility evaluation is moving beyond classical techniques to leverage high-throughput functional proteomics. These methods allow for the unbiased, large-scale identification of protein expression changes and post-translational modifications in cells exposed to biomaterials, providing a systems-level view of the immune response [6].

- Protein Microarrays: Enable simultaneous screening of hundreds to thousands of proteins to identify biomarkers of inflammation, autoantibodies, or cytokine profiles triggered by biomaterials [6].

- Mass Spectrometry (MS)-Based Proteomics:

- Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA): Provides comprehensive, quantitative profiling of complex protein mixtures from cell lysates, ideal for discovering novel protein signatures of biocompatibility or immunogenicity [6].

- Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM): A targeted MS technique used for highly sensitive and reproducible quantification of specific candidate protein biomarkers (e.g., key cytokines or signaling molecules) identified in discovery-phase experiments [6].

Integrating these advanced proteomic approaches with classical molecular biology techniques provides a powerful, multi-dimensional framework for deconstructing the complex cellular and molecular interactions that define biomaterial biocompatibility, ultimately accelerating the development of safer and more effective medical devices.

The ISO 10993 series, titled "Biological evaluation of medical devices," comprises a set of international standards that provide a framework for evaluating the biocompatibility of medical devices to manage biological risk [12]. These standards are foundational for ensuring that medical devices are safe for their intended use and serve as critical tools for global market access, regulatory compliance, and patient safety [13]. For the purpose of this standard, biocompatibility is defined as the "ability of a medical device or material to perform with an appropriate host response in a specific application" [14] [12]. This definition underscores that biocompatibility is not merely the absence of cytotoxicity but encompasses the broader requirement for a device to function appropriately within a biological system without eliciting undesirable effects [14] [2].

The central theme of the ISO 10993 series is the integration of biological evaluation into a risk management process, as outlined in its first part, ISO 10993-1 [13] [15]. This standard serves as the cornerstone document, providing the overarching principles and requirements for assessing a device's biological safety [13]. The evaluation process considers the nature and duration of body contact, the materials used, and the biological endpoints that need to be addressed [12]. Compliance with ISO 10993 is a fundamental expectation of regulatory bodies worldwide, including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which has issued its own guidance document to support the interpretation and implementation of the standard [16] [12].

The ISO 10993-1 Risk Management Framework

The latest edition of ISO 10993-1, published in 2025, represents a significant evolution by fully integrating the biological evaluation process within the risk management framework established by ISO 14971 [13] [15]. This alignment ensures that biological safety is assessed systematically throughout the device lifecycle, from initial design through post-market surveillance [15]. The standard guides manufacturers and evaluators through identifying, assessing, and managing biological risks associated with materials, design choices, and tissue contact during a device's intended use [13].

The risk management process for biological evaluation, as defined in ISO 10993-1:2025, includes several key stages. It begins with the identification of biological hazards, followed by defining biologically hazardous situations, and then establishing potential biological harms [15]. Once these biological harms are identified, biological risk estimation is performed based on the severity and probability of harm, mirroring the methodology described in ISO 14971 [15]. The standard also introduces a more rigorous approach to considering reasonably foreseeable misuse, which is defined as "use of a product or system in a way not intended by the manufacturer, but which can result from readily predictable human behaviour" [15]. This requires manufacturers to anticipate and account for potential misuse scenarios that could impact biological safety.

The following diagram illustrates this integrated risk management process for biological evaluation:

Categorization of Medical Devices and Endpoint Selection

A fundamental aspect of ISO 10993-1 is the categorization of medical devices based on the nature of body contact and contact duration, which drives the selection of appropriate biological endpoints for evaluation [12]. This systematic categorization ensures that the biological safety evaluation is tailored to the specific characteristics and intended use of the device.

The standard defines three primary categories of body contact: surface devices, externally communicating devices, and implant devices [12]. Each category is further subdivided based on the specific tissues contacted, such as intact skin, mucosal membranes, breached surfaces, tissue/bone, or circulating blood. Complementing this, the standard establishes three duration categories: limited exposure (≤24 hours), prolonged exposure (>24 hours to 30 days), and long-term exposure (>30 days) [15] [12]. The determination of contact duration has been refined in the 2025 edition, which now requires consideration of multiple exposures and introduces concepts such as "total exposure period" and "contact day" to more accurately capture cumulative patient exposure [15].

Based on this categorization, ISO 10993-1 provides guidance on which biological endpoints require evaluation. The table below summarizes the recommended endpoints for various device categories based on the nature and duration of body contact.

Table 1: Biological Endpoint Evaluation Based on Device Categorization

| Nature of Body Contact | Specific Tissue | Contact Duration | Cytotoxicity | Sensitization | Irritation | Systemic Toxicity | Genotoxicity | Implantation | Hemocompatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Device | Intact Skin | Limited | X | X | X | ||||

| Prolonged | X | X | X | ||||||

| Long-term | X | X | X | ||||||

| Surface Device | Mucosal Membrane | Limited | X | X | X | ||||

| Prolonged | X | X | X | O | O | O | |||

| Long-term | X | X | X | O | O | X | O | ||

| Externally Communicating | Tissue/Bone/Dentin | Limited | X | X | X | O | O | ||

| Prolonged | X | X | X | X | O | X | X | ||

| Long-term | X | X | X | X | O | X | O | ||

| Externally Communicating | Circulating Blood | Limited | X | X | X | X | O | O | X |

| Prolonged | X | X | X | X | O | X | X | ||

| Long-term | X | X | X | X | O | X | X | ||

| Implant Device | Tissue/Bone | Limited | X | X | X | O | O | ||

| Prolonged | X | X | X | X | O | X | X | ||

| Long-term | X | X | X | X | O | X | O | ||

| Implant Device | Blood | Limited | X | X | X | X | O | O | X |

| Prolonged | X | X | X | X | O | X | X | ||

| Long-term | X | X | X | X | O | X | X |

X = ISO 10993-1 recommended endpoints for consideration; O = Additional FDA recommended endpoints for consideration [12]

Integration of Molecular Biology Techniques in Biocompatibility Assessment

While traditional biocompatibility testing provides essential safety data, modern biomaterials research increasingly relies on molecular biology techniques to gain deeper insights into the interactions between biomaterials and biological systems at a cellular and molecular level [3]. These techniques enable researchers to detect and quantify gene and protein expression, particularly those involved in inflammation and tissue regeneration, providing molecular-level insights into how cells respond to biomaterial cues [3].

Molecular biology methods offer several advantages for biocompatibility assessment, including the ability to identify subtle cellular responses long before they manifest as histological changes, elucidate specific mechanisms of biological responses, and provide highly quantitative and objective data on cellular reactions to biomaterials [3]. Key techniques include recombinant DNA technology, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), in situ hybridization, immunocytochemistry (ICC), and immunohistochemistry (IHC) [3]. These tools are particularly valuable for identifying inflammatory markers, tracking cell differentiation, and understanding tissue integration processes, which are central to evaluating the biocompatibility and biofunctionality of biomaterials in various applications [3].

The application of these techniques faces technical challenges, including interference from the physicochemical properties of biomaterials, difficulties in sample preparation, and the standardization of protocols across different platforms [3]. However, emerging opportunities involving the integration of 3D imaging technologies and artificial intelligence promise to enhance our ability to manage and interpret the complex biological data generated through these methods [3].

The following workflow illustrates how molecular biology techniques integrate with the ISO 10993 biological evaluation process:

Experimental Protocols for Key Biocompatibility Tests

Cytotoxicity Testing (ISO 10993-5)

Purpose: To evaluate the potential of device extracts to cause cell death, inhibit cell growth, or produce other toxic effects on cells [17].

Sample Preparation: Prepare extracts of the test material using appropriate solvents (e.g., saline, culture media with serum) at extraction ratios and conditions specified in ISO 10993-12 [17]. Include both negative and positive controls.

Protocol:

- Cell Culture: Use established cell lines such as L-929 mouse fibroblasts cultured in appropriate media under standard conditions [17].

- Exposure: Expose cells to device extracts using one of these methods:

- Incubation: Incubate at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for 24-72 hours.

- Assessment: Evaluate cell response using microscopic examination and quantitative measures such as:

- Scoring: Grade cytotoxicity based on the degree of cell damage and destruction.

Molecular Biology Integration: For enhanced assessment, incorporate gene expression analysis of apoptosis markers (e.g., caspase-3, BAX/BCL-2 ratio) using quantitative PCR to detect subtle cytotoxic effects [3].

Sensitization Testing (ISO 10993-10)

Purpose: To determine whether device extracts have the potential to cause allergic contact dermatitis [17].

Sample Preparation: Prepare extracts of the test material using polar and non-polar solvents as specified in ISO 10993-12.

Protocol:

- Test System: Use guinea pigs or murine local lymph node assay (LLNA) models.

- Induction Phase:

- Challenge Phase: After 10-14 days, apply test material to a fresh site.

- Evaluation:

- Interpretation: Classify materials based on the incidence and severity of skin reactions.

Molecular Biology Integration: Incorporate cytokine profiling (IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IFN-γ) from challenge sites using ELISA or multiplex immunoassays to differentiate types of hypersensitivity responses [3].

Genotoxicity Testing (ISO 10993-3)

Purpose: To assess the potential of device extracts to cause gene mutations, chromosomal aberrations, or other DNA damage [17].

Sample Preparation: Prepare extracts using appropriate solvents at conditions that simulate clinical use.

Protocol:

- Bacterial Reverse Mutation Assay (Ames Test):

- Use Salmonella typhimurium strains with different mutations to detect point mutations [17].

- Expose bacteria to device extracts with and without metabolic activation.

- Count revertant colonies and compare to negative and positive controls.

- In Vitro Mammalian Cell Assays:

- In Vivo Tests (if warranted):

- Micronucleus Test: Analyze bone marrow or peripheral blood cells for micronuclei formation [17].

Molecular Biology Integration: Implement comet assay (single cell gel electrophoresis) to detect DNA damage at the individual cell level and γ-H2AX immunofluorescence staining to identify DNA double-strand breaks [3].

Implantation Testing (ISO 10993-6)

Purpose: To evaluate the local effects of an implantable material on living tissue [17].

Sample Preparation: Prepare test materials of appropriate size and shape, sterilized according to intended use.

Protocol:

- Surgical Implantation:

- Select appropriate site (muscle, subcutaneous, or site-specific) in animal model.

- Create implantation pockets and insert test materials, controls, and sham sites.

- Ensure sufficient sample size for statistical analysis.

- Study Duration: Based on intended use and evaluation endpoints (typically 1, 4, 12, 26, or 52 weeks).

- Histopathological Processing:

- Retrieve implant sites with surrounding tissue at sacrifice.

- Process tissues for histological evaluation (paraffin or plastic embedding).

- Section tissues and stain with H&E and special stains as needed.

- Histopathological Evaluation:

- Assess tissue response parameters: inflammation, fibrosis, necrosis, degeneration, and tissue integration [17].

- Score responses using semi-quantitative grading scales.

- Compare test articles to controls.

Molecular Biology Integration: Incorporate in situ hybridization to localize specific mRNA transcripts of inflammatory markers (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) and immunohistochemistry to detect protein expression of extracellular matrix components (collagen types, fibronectin) and cell phenotype markers [3].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biomaterial Testing

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting biocompatibility assessments, particularly those integrating molecular biology techniques.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biomaterial Biocompatibility Testing

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Systems | In vitro cytotoxicity and cell-based assays | L-929 mouse fibroblasts [17], human primary cells, co-culture systems |

| Molecular Biology Kits | Nucleic acid extraction and analysis | PCR kits, RNA/DNA extraction kits, cDNA synthesis kits [3] |

| Antibodies | Protein detection and cellular characterization | Primary and secondary antibodies for ICC/IHC, flow cytometry [3] |

| ELISA Assays | Cytokine and protein quantification | Commercial kits for TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, etc. [3] |

| Histology Reagents | Tissue processing and staining | Fixatives (formalin), embedding media (paraffin, resin), stains (H&E) [17] |

| Extraction Solvents | Preparation of device extracts | Polar (saline, culture media) and non-polar (DMSO, vegetable oil) solvents [17] |

| Positive Controls | Assay validation and quality control | Latex for sensitization, cytotoxic chemicals, known mutagens [17] |

| Animal Models | In vivo biocompatibility assessment | Rodents, guinea pigs, rabbits (IACUC approved) [17] |

The ISO 10993 series provides an essential framework for the biological evaluation of medical devices, with the 2025 edition of ISO 10993-1 representing a significant advancement through its full integration with risk management principles [15]. The standard's systematic approach to device categorization and endpoint selection ensures that biological safety evaluations are appropriately tailored to the specific device characteristics and intended use [12]. For contemporary biomaterials research, the integration of molecular biology techniques with traditional biocompatibility testing offers powerful tools to elucidate the mechanisms underlying biological responses to medical devices [3]. These methods provide deeper insights into cellular and molecular interactions, enabling the development of safer and more effective medical devices that not only avoid adverse reactions but also promote appropriate host responses for optimal clinical performance [3] [14].

Essential Molecular Methods for Biocompatibility Profiling

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) for Analyzing Gene Expression of Inflammatory and Regenerative Markers

Within the field of biomaterial biocompatibility testing, understanding the molecular response of host tissues is paramount. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has emerged as a cornerstone technique for profiling gene expression, enabling researchers to decipher complex cellular interactions with implanted materials. By analyzing the expression of inflammatory and regenerative markers, scientists can predict long-term biocompatibility, assess the success of tissue integration, and identify potential fibrotic or rejection pathways. This application note provides a detailed protocol for using quantitative PCR (qPCR) to evaluate key genetic markers, framed within the context of a broader thesis on molecular biology techniques for biomaterial research. It is designed to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the methodologies necessary to generate robust, quantitative data on cellular responses to novel biomaterials.

Key Gene Targets for Biomaterial Testing

The selection of gene targets is critical for accurately characterizing the host response to a biomaterial. The table below summarizes key inflammatory and regenerative markers, their functions, and documented expression changes relevant to biocompatibility.

Table 1: Key Inflammatory and Regenerative Markers for Biomaterial Biocompatibility Assessment

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Primary Function | Relevance to Biomaterial Testing | Reported Expression Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADM | Adrenomedullin [18] | Vasodilation, angiogenesis, immunoregulation [18] | Associated with cardiovascular abnormalities and pathophysiological development; a marker of stress response [18]. | Upregulated (3x higher fold change) [18] |

| EDN1 | Endothelin-1 [18] | Potent vasoconstrictor, pro-fibrotic signaling [18] | Higher levels found in hypertensive individuals; contributes to vascular resistance [18]. | Upregulated (3x higher fold change) [18] |

| ANGPTL4 | Angiopoietin-like 4 [18] | Angiogenesis, lipid metabolism [18] | Contributes to pathophysiology of cardiovascular conditions [18]. | Upregulated (3x higher fold change) [18] |

| IL1B | Interleukin-1 Beta [19] | Pro-inflammatory cytokine | Key mediator of the initial inflammatory phase; upregulation indicates acute immune activation [19]. | Upregulated by pro-inflammatory stimuli [19] |

| CD206 | Macrophage Mannose Receptor [19] | Phagocytosis, anti-inflammatory resolution | Marker for alternatively activated (M2) macrophages; associated with tissue repair and regenerative phases [19]. | Downregulated by pro-inflammatory stimuli; upregulated by anti-inflammatory stimuli (IL-4/IL-10) [19] |

| CD163 | Scavenger Receptor [19] | Hemoglobin clearance, anti-inflammatory | Another marker for M2 macrophages; indicates a shift towards wound healing and remodeling [19]. | Downregulated by pro-inflammatory stimuli [19] |

| PRKCD | Protein Kinase C Delta [20] | Oxidative stress response, apoptosis | Identified as a marker gene associated with oxidative stress in hypertrophic tissue; may influence immune microenvironment [20]. | Associated with elevated oxidative stress and apoptosis [20] |

| JAK2 | Janus Kinase 2 [20] | Cytokine receptor signaling | Oxidative stress-related gene; implicated in signaling pathways activated during foreign body response [20]. | Identified as a diagnostic biomarker [20] |

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

The following table outlines essential reagents and materials required for successful gene expression analysis via qPCR in a biomaterial testing context.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for qPCR-based Gene Expression Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Thermostable enzyme for DNA synthesis during PCR amplification [21]. | A recombinant form from Thermus aquaticus is commonly used; supplied with optimized 10x reaction buffer [22]. |

| SYBR Green I Dye | Fluorescent dsDNA-binding dye for real-time product detection [23]. | Binds to any dsDNA; requires post-amplification melting curve analysis to verify product specificity and exclude primer-dimer artifacts [23]. |

| TaqMan Probes | Sequence-specific oligonucleotide probes for highly specific real-time detection [23]. | Consist of a 5' reporter fluorophore and a 3' quencher; cleavage by Taq polymerase' 5' nuclease activity generates fluorescence [23]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Enzyme for synthesizing complementary DNA (cDNA) from mRNA templates [21]. | Critical first step for gene expression analysis; often derived from retroviruses [21]. |

| Primers | Short, single-stranded DNA sequences that define the start and end of the target amplicon [21]. | Typically 20-25 nucleotides long; optimal annealing temperature (55-72°C) depends on their physicochemical properties [21]. |

| dNTPs | Deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP); the building blocks for new DNA strands [22]. | Included in pre-mixed master mixes for convenience and consistency [22]. |

| MgClâ‚‚ | Cofactor essential for Taq DNA polymerase activity [22]. | Concentration must be optimized for each primer-template system; titration is often necessary for maximum efficiency [22]. |

| RNA Extraction Kit | For isolating high-quality, intact total RNA from cells or tissues on the biomaterial. | Quality of starting RNA is the most critical factor for reliable results. |

| PCR Array | Pre-configured multi-well plates containing primers for a focused panel of genes [24]. | Enables simultaneous profiling of 84+ genes related to a specific process (e.g., wound healing), streamlining biomarker discovery [24]. |

| 4,6-Dichloro-3-formylcoumarin | 4,6-Dichloro-3-formylcoumarin, CAS:51069-87-5, MF:C10H4Cl2O3, MW:243.04 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 11-Methyltridecanoic acid | 11-Methyltridecanoic acid, CAS:29709-05-5, MF:C14H28O2, MW:228.37 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow, from cell seeding to data analysis.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Cell Seeding and Stimulation

- Cell Number Considerations: Seed cells at a constant density in an appropriate multi-well plate. Studies have shown that reliable gene expression profiles can be obtained even with low cell numbers (e.g., as low as ~3,600 cells in a 96-well format) without significant differences from larger-scale cultures, which is advantageous for testing scarce primary cells or high-throughput biomaterial screening [19].

- Biomaterial Exposure: Introduce the test biomaterial to the culture system according to the experimental design (e.g., direct contact, extract exposure).

- Stimulation (Optional): To challenge the cellular response and reveal the biomaterial's immunomodulatory effects, stimulate the cells with pro-inflammatory (e.g., 100 ng/mL LPS + 10 µg/mL poly(I:C)) or anti-inflammatory (e.g., 20 ng/mL IL-4 + 20 ng/mL IL-10) cues for 6-24 hours [19]. Include unstimulated controls.

Step 2: RNA Extraction and Quantification

- Extraction: At the desired time point, lyse cells and extract total RNA using a commercial kit. Ensure all equipment and surfaces are RNase-free to prevent RNA degradation.

- Quantification and Quality Control: Precisely quantify the RNA concentration using a spectrophotometer (e.g., Nanodrop). Assess RNA integrity (e.g., via agarose gel electrophoresis or Bioanalyzer). Use only samples with an A260/A280 ratio of ~2.0 and intact ribosomal RNA bands for subsequent steps.

Step 3: Reverse Transcription (cDNA Synthesis)

- Reaction Setup: In a nuclease-free tube, combine the following components on ice:

- Total RNA: 100 ng - 1 µg

- Oligo(dT) and/or Random Hexamer Primers: 0.5-2.5 µM

- dNTP Mix: 0.5-1 mM each

- Reverse Transcriptase: 1-2 µL (follow manufacturer's instructions)

- RNase Inhibitor: 10-20 U

- 5X Reaction Buffer: as per manufacturer

- Nuclease-free water to a final volume of 20 µL.

- Incubation: Run the reaction in a thermal cycler with the following conditions: priming for 10 minutes at 25°C, reverse transcription for 30-60 minutes at 50°C, and enzyme inactivation for 5 minutes at 85°C. The resulting cDNA can be stored at -20°C.

Step 4: Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Reaction Setup

- Detection Chemistry Selection: Choose between intercalating dye (e.g., SYBR Green I) or probe-based (e.g., TaqMan) chemistry. SYBR Green is more cost-effective but requires rigorous optimization and melting curve analysis to ensure specificity. TaqMan probes offer superior specificity and are ideal for multiplexing but are more expensive [23].

- Reaction Assembly: Prepare reactions in a optical 96- or 384-well plate. A typical 20 µL reaction contains:

- 2X SYBR Green Master Mix or TaqMan Universal Master Mix: 10 µL

- Forward and Reverse Primer Mix (final concentration 0.1-0.5 µM each) or TaqMan Probe/Prime r Mix: 2 µL

- cDNA template (typically a 1:10 dilution of the RT reaction): 2-5 µL

- Nuclease-free water: to 20 µL.

- Technical Replicates: Perform each reaction in at least triplicate to account for technical variability.

Step 5: Thermal Cycling and Fluorescence Acquisition

- Load the plate into the real-time PCR instrument. The standard thermal cycling protocol involves:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2-10 minutes (enzyme activation).

- Amplification Cycles (Repeat 40-45 times):

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds.

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 1 minute (acquire fluorescence at this step). Note: The annealing temperature is primer-specific and may require optimization, typically between 55-72°C [21].

- Post-Amplification Melting Curve (For SYBR Green only): After the final cycle, run a melting curve analysis from 65°C to 95°C in 0.5°C increments to verify the amplification of a single, specific product.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Quantification Cycle (Cq) Determination: The software will assign a Cq value for each reaction, representing the cycle number at which the fluorescence crosses a predetermined threshold.

- Normalization to Reference Genes: Calculate the ΔCq for each sample: ΔCq = Cq(target gene) - Cq(reference gene). Use stable reference genes (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB) that are unaffected by the biomaterial or treatment [19].

- Fold Change Calculation: Use the comparative ΔΔCq method to calculate the relative fold change in gene expression [18] [21].

- ΔΔCq = ΔCq(treated sample) - ΔCq(control calibrator sample)

- Fold Change = 2^(-ΔΔCq)

- Interpretation for Biocompatibility: Analyze the expression profile of your selected markers. A pro-inflammatory profile is characterized by high levels of IL1B, ADM, and EDN1. A pro-regenerative or anti-inflammatory profile is indicated by elevated levels of CD206 and CD163. The overall balance of these markers provides a molecular signature of the host response to the biomaterial.

Signaling Pathways in the Host Response

The host response to a biomaterial involves the complex interplay of multiple signaling pathways. The diagram below illustrates key pathways and their connections to the inflammatory and regenerative markers analyzed by PCR.

Critical Factors for Reliable Results

- Primer Design and Validation: Primers should be 20-25 nucleotides long and designed to span an exon-exon junction where possible to avoid amplification of genomic DNA. Verify primer specificity using BLAST and confirm with a single peak in the melting curve and a single band of the expected size on an agarose gel [21] [23].

- RNA Integrity: The quality of the input RNA is the single most critical factor. Degraded RNA will lead to biased and non-reproducible results.

- PCR Efficiency: For accurate quantification using the ΔΔCq method, the amplification efficiency of the target and reference genes must be approximately equal and close to 100% (a doubling of product each cycle). Efficiency can be assessed using a standard curve from a serial dilution of cDNA [21].

- Minimizing Contamination: PCR is extremely sensitive to contamination. Perform RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and PCR setup in separate, dedicated areas. Use aerosol-resistant pipette tips and include negative controls (no-template and no-reverse-transcriptase controls) in every run [21].

Recombinant DNA Technology and In Situ Hybridization for Spatial Gene Expression

The evaluation of biomaterial biocompatibility has evolved from assessing basic tissue acceptance to understanding complex molecular-level interactions. A critical aspect of this understanding lies in determining how biomaterials influence spatial gene expression patterns in surrounding tissues and cells. The integration of recombinant DNA technology with advanced in situ hybridization (ISH) methods provides powerful tools to visualize and quantify these spatial relationships, offering unprecedented insights into host-material interactions. These techniques enable researchers to map gene expression while preserving morphological context, revealing how biomaterials alter local cellular environments at the transcriptional level—essential information for developing safer, more effective medical devices and implantable materials.

For biomaterial research, spatial context is particularly crucial as cellular responses often vary significantly based on proximity to the implant interface. Techniques that preserve architectural information can identify zoned inflammatory responses, gradients of stress gene expression, and heterogeneous cellular adaptation to material surfaces. This application note details how modern molecular biology techniques, specifically recombinant DNA-based ISH approaches, can be implemented to advance biomaterial biocompatibility research, with protocols optimized for the unique challenges of material-tissue interface analysis.

Technical Foundations and Principles

Core Methodological Framework

The convergence of recombinant DNA technology with ISH has created a sophisticated toolbox for spatial genetic analysis. Recombinant DNA methodologies enable the production of highly specific, customizable nucleic acid probes through molecular cloning and amplification techniques. These probes form the foundation of modern ISH applications, allowing researchers to design detection systems with enhanced specificity and signal-to-noise ratios for challenging samples like biomaterial-tissue interfaces.

In situ hybridization provides the spatial context by allowing these recombinant probes to hybridize directly to complementary nucleic acid sequences within intact tissue sections or cells, preserving architectural information. The fundamental principle involves using labeled nucleic acid probes to detect specific DNA or RNA sequences within morphologically preserved biological samples. When applied to biomaterial research, this approach can reveal how material properties influence genetic programs in adjacent versus distant cells, providing mechanistic insights into biocompatibility.

Recent advancements have significantly expanded these capabilities through isothermal amplification strategies and signal amplification systems that push detection sensitivity to single-molecule levels. For instance, Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) enables multiplexed, quantitative RNA imaging with high specificity and signal amplification without enzymes, making it particularly valuable for detecting low-abundance transcripts in heterogeneous tissue samples surrounding implants [25]. Similarly, DNA microscopy represents a revolutionary approach that encodes spatial relationships directly into DNA sequences, allowing for computational reconstruction of molecular positions without direct optical imaging [26].

Advanced DNA Circuitry for Enhanced Detection

Beyond conventional ISH, sophisticated DNA-based circuits now enable intracellular imaging of enzymatic activities relevant to biomaterial responses. Self-replicating DNA circuits (SDCs) integrate signal transduction modules with amplification mechanisms, allowing sensitive detection of biomarkers such as polynucleotide kinase (PNK)—an enzyme involved in DNA repair pathways that may be activated in response to genotoxic stress from biomaterial degradation products [27]. These systems function through cleverly designed hairpin probes that undergo structural changes upon encountering target enzymes, initiating cascades of hybridization events that generate amplified, localized signals ideal for spatial mapping within cells exposed to test materials.

Application Notes for Biomaterial Research

Practical Implementation Considerations

Implementing recombinant DNA and ISH technologies for biomaterial biocompatibility studies requires careful consideration of several application-specific factors:

Sample Preparation Challenges: Tissue samples containing biomaterials often present sectioning difficulties due to hardness mismatches between tissue and material phases. For hard implants, decalcification or specialized sectioning may be required, potentially compromising nucleic acid integrity. Optimal fixation conditions must balance morphology preservation with RNA retention—over-fixation can mask epitopes and reduce hybridization efficiency [28].

Probe Design Strategy: For biocompatibility studies focusing on specific pathways (inflammatory response, oxidative stress, extracellular matrix remodeling), custom probe sets can be designed using recombinant methods. RNA probes should typically be 250-1,500 bases in length, with approximately 800 bases often providing optimal sensitivity and specificity [28]. The development of cost-effective probe design tools, such as the automated HCR Probe Designer for non-model organisms, makes customized probe generation more accessible for specialized biocompatibility questions [25].

Multiplexing Capabilities: Understanding complex tissue responses to biomaterials often requires simultaneous detection of multiple genetic markers. Multiplexed whole-mount RNA fluorescence ISH combined with immunohistochemistry enables concurrent visualization of mRNA and protein in intact tissues, providing a more comprehensive view of cellular states at material interfaces [25]. Careful fluorophore selection using fluorescence spectra viewers (e.g., FPbase.org) minimizes spectral overlap in multiplexed experiments.

Integration with Standard Biocompatibility Testing

Spatial gene expression analysis complements standard biocompatibility tests prescribed by ISO 10993 standards, which include cytotoxicity, sensitization, and genotoxicity evaluations [29] [30] [31]. While conventional tests determine whether a material causes adverse effects, spatial transcriptomic approaches reveal mechanistic insights and subtle, localized responses that may be missed in bulk analyses. This is particularly valuable for detecting heterogeneous cellular responses at material-tissue interfaces, identifying subtoxic but biologically relevant changes, and understanding temporal progression of tissue integration or rejection.

Table 1: Correlation Between ISO 10993 Tests and Spatial Gene Expression Applications

| ISO 10993 Test Category | Relevant Spatial Gene Expression Targets | Information Gained |

|---|---|---|

| Cytotoxicity (ISO 10993-5) | Apoptosis regulators (Bax, Bcl-2), Stress response genes (HSP70, CHOP) | Mechanism of cell death; sublethal stress responses |

| Sensitization (ISO 10993-10) | Cytokine genes (IL-4, IL-13, IL-17), Immune cell markers (CD3, CD68) | Immune activation pathways; cell types involved |

| Genotoxicity (ISO 10993-3) | DNA damage response genes (p53, GADD45), Repair enzymes (PNK) [27] | Localized genotoxic stress; DNA repair activation |

| Implantation (ISO 10993-6) | Extracellular matrix genes (COL1A1, FN1), Angiogenesis factors (VEGF) | Tissue remodeling patterns; integration quality |

Experimental Protocols

Multiplex Whole-Mount RNA Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization with Immunohistochemistry

This protocol, adapted for biomaterial-tissue interface analysis, enables simultaneous visualization of mRNA and protein markers in intact tissue samples, providing spatial context for host responses to implanted materials [25].

Sample Preparation and Fixation

- Tissue Collection: Excise tissue containing biomaterial implant with surrounding tissue. For hard implants, careful dissection may be necessary to maintain interface integrity.

- Fixation: Immediately place tissue in freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde with 0.3% Triton X-100 in 1× PBS. Fix for 24-48 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation. For optimal RNA preservation, limit fixation time to the minimum required for adequate morphology.

- Permeabilization: For improved probe penetration, especially with dense tissue or fibrous capsules surrounding implants, treat samples with proteinase K (20 µg/mL in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5) for 10-20 minutes at 37°C. Optimal concentration and time require titration based on tissue type and fixation duration [28].

- Storage: Store fixed samples in 100% ethanol at -20°C or in protective wrapping at -80°C for long-term preservation. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles [28].

HCR Probe Design and Preparation

- Probe Design: For custom probe design targeting specific genes of interest, use automated tools such as the HCR Probe Designer [25]. Input genomic sequence in FASTA format and specify parameters:

- Oligo length: 25 bases

- Melting temperature: 47°C–85°C

- GC content: 37–85%

- Specificity: <60% sequence similarity to non-target transcripts

- Probe Selection: Select 15–20 probe pairs per transcript to ensure sufficient detection sensitivity. Order custom DNA oligonucleotides with 100 µM concentration, desalted and frozen in water [25].

- Amplifier Preparation: Prepare HCR hairpin amplifiers according to manufacturer protocols (Molecular Instruments, Inc.) or published methods [25]. Aliquot and store at -20°C protected from light.

Hybridization and Signal Detection

- Pre-hybridization: Equilibrate samples in hybridization buffer (50% formamide, 5× salts, 5× Denhardt's solution, 10% dextran sulfate, 20 U/mL heparin, 0.1% SDS) for 1 hour at the hybridization temperature (typically 55–62°C) [28].

- Probe Hybridization: Dilute HCR probes in hybridization buffer, denature at 95°C for 2 minutes, then chill on ice. Replace pre-hybridization buffer with probe solution and incubate overnight at 65°C in a humidified chamber [25] [28].

- Stringency Washes:

- Wash 3× 5 minutes with 50% formamide in 2× SSC at 37–45°C

- Wash 3× 5 minutes with 0.1–2× SSC at 25–75°C (temperature and stringency dependent on probe characteristics) [28]

- HCR Amplification: Incubate samples with pre-amplified HCR hairpins in amplification buffer overnight at room temperature protected from light.

- Immunohistochemistry: Following HCR detection, proceed with standard immunohistochemistry using species-appropriate primary and secondary antibodies to detect protein co-localization [25].

- Mounting and Imaging: Clear samples and mount for 3D imaging using confocal or light-sheet microscopy. For samples containing opaque biomaterials, refractive index matching may be necessary.

DNA Microscopy for Volumetric Spatial Transcriptomics

DNA microscopy represents a revolutionary approach for capturing spatial genetic information without direct imaging, particularly valuable for analyzing complex 3D tissue structures around biomaterials [26].

Sample Processing and UMI Tagging

- Fixation and Permeabilization: Fix tissue samples with biomaterial implants in 4% PFA for 24 hours at 4°C. Permeabilize with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1–2 hours at room temperature.

- Reverse Transcription: Convert RNA to cDNA using random primers with reverse transcriptase.

- UMI Tagging: Add 3′ DNA overhangs using Tn5 transposase and double-stranded DNA ligase. Anneal precircularized single-stranded DNA molecules containing Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) with 31 randomized nucleotides to protruding adaptors [26].

Multiscale Proximity Encoding

- Anchored Diffusion (RCA): Perform rolling circle amplification (RCA) using strand-displacing DNA polymerase to create DNA nanoballs with tandem UMI copies while maintaining spatial origin information.

- Unanchored Diffusion (IVT): Embed samples in reversible PEG hydrogel and perform in vitro transcription (IVT) with uracil endonucleases to allow longer-range molecular interactions [26].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Amplify products via RT-PCR and prepare sequencing libraries. Sequence using high-throughput platforms to capture UMI-UEI (Unique Event Identifier) relationships.

Image Inference and Data Analysis

- UEI Matrix Construction: Assemble sparse UEI matrix where rows and columns represent UMI-tagged molecules and values reflect interaction frequencies.

- Spectral Embedding: Apply geodesic spectral embedding for dimensionality reduction to infer relative spatial coordinates of original UMIs [26].

- Genetic Mapping: Align cDNA sequences to reference genome and map to spatial coordinates to create volumetric gene expression maps.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantitative Assessment of Spatial Expression Patterns

The quantitative data derived from spatial gene expression techniques requires specialized analytical approaches to extract biologically meaningful information about biomaterial-tissue interactions.

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters from Spatial Gene Expression Analysis in Biocompatibility Testing

| Parameter | Measurement Approach | Interpretation in Biocompatibility Context |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Zonation | Distance-based expression profiling from material interface | Identification of effective biological influence distance of material |

| Gradient steepness | Exponential decay modeling of expression vs. distance | Strength of material effect on cellular responses |

| Cellular response heterogeneity | Entropy measurements of expression patterns | Uniformity vs. variability of tissue response |

| Co-expression patterns | Correlation analysis of multiple transcripts | Identification of coordinated response pathways |

| Expression spatial entropy | Shannon entropy calculations across tissue regions | Degree of organization/disorganization in tissue response |

| Interface-specific expression | Differential expression at material interface vs. bulk tissue | Direct contact effects versus secondary responses |

Integration with Biomaterial Characterization Data

Correlating spatial gene expression patterns with material properties is essential for understanding structure-function relationships in biomaterial design. Key integration points include: