Innovations in Surgical Suture Fabrication: A Comprehensive Guide to 3D Printing Methods and Materials for Advanced Wound Closure

This article provides a detailed exploration of 3D printing methodologies for creating next-generation surgical sutures.

Innovations in Surgical Suture Fabrication: A Comprehensive Guide to 3D Printing Methods and Materials for Advanced Wound Closure

Abstract

This article provides a detailed exploration of 3D printing methodologies for creating next-generation surgical sutures. It begins by establishing the fundamental principles and rationale behind additive manufacturing in suture production. The core examines current techniques, from material extrusion to advanced bioprinting, and their applications in developing smart sutures. Practical guidance is offered for troubleshooting common printing defects and optimizing mechanical and biological performance. The discussion critically validates these novel sutures against traditional counterparts through comparative analysis of mechanical properties, biocompatibility, and degradation. Aimed at researchers and biomedical engineers, this review synthesizes the state of the field, identifies key challenges, and outlines future trajectories for personalized, functional, and bioactive suture technology.

The Rationale and Evolution: Why 3D Printing is Revolutionizing Surgical Suture Design

1. Application Notes

Surgical sutures remain indispensable for wound closure and tissue approximation. However, conventional suture manufacturing (e.g., monofilament extrusion, multifilament braiding) imposes fundamental limitations that hinder innovation in surgical repair and regenerative medicine. This document contextualizes these limitations within a thesis research framework focused on developing a novel additive manufacturing (AM) methodology for next-generation sutures.

1.1. Quantified Limitations of Conventional Sutures The constraints of traditional sutures are well-documented in current literature, presenting a clear justification for alternative manufacturing approaches.

Table 1: Quantitative Limitations of Conventional Suture Technologies

| Limitation Category | Specific Issue | Quantitative Data / Current Evidence | Impact on Surgical & Therapeutic Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material & Structural Homogeneity | Limited material diversity (mostly PGA, PLA, PDO, silk, nylon). | >90% of absorbable sutures are from 3 polymer families (PGA, PLA, copolymers). | Inability to match site-specific mechanical (e.g., tendon vs. bowel) and degradation requirements. |

| Drug Delivery Capacity | Simple, surface-level coatings. | Burst release: >60% of drug released within 24h. Low loading capacity: typically <5% w/w. | Inefficient prophylaxis of infection, poor spatiotemporal control over anti-proliferative or pro-regenerative agents. |

| Architectural Complexity | Lack of controlled porosity or micro-texture. | Surface area limited to geometric surface of filament (e.g., ~0.4 mm²/mm for a 5-0 suture). | Poor cell infiltration and integration, leading to foreign body response and scarring. Limited capacity for guided tissue regeneration. |

| Mechanical Performance Mismatch | Static mechanical properties. | Stress-strain curves are linear or strain-hardening, unlike many soft tissues (J-shaped). | Stress concentration, suture pull-through, and tissue strangulation, especially in dynamic environments. |

| Manufacturing Flexibility | Long lead times for new designs. | Prototyping a new suture variant via extrusion/spinning can take 6-18 months. | Severely impedes rapid iteration for patient-specific or application-specific designs. |

1.2. The Additive Manufacturing Promise: A Functionalized Suture Paradigm AM, or 3D printing, offers a disruptive pathway to create "smart," functionalized sutures by enabling precise spatial control over material composition, architecture, and bioactive agent placement. The core thesis of this research is that a direct-write, multi-material AM platform can integrate these functions into a single, continuous suture construct.

Table 2: AM-Enabled Functional Suture Capabilities vs. Conventional Paradigm

| Suture Function | Conventional Paradigm | AM-Enabled Promise (Thesis Focus) | Target Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Properties | Homogenous, isotropic properties. | Graded Stiffness: Core-shell designs with stiff core/soft sheath. Anisotropy: Aligned microstructures for directional strength. | Match tissue J-curve within 15%; reduce stiffness mismatch by >50%. |

| Drug/Bioactive Delivery | Surface-coated, burst release. | Multi-Agent, Spatially-Programmed Release: >2 drugs in defined suture segments. High-Capacity Loading: Integration of porous, drug-loaded microparticles. | Sustain release >21 days; achieve loading >20% w/w; enable sequential release profiles. |

| Tissue Integration | Smooth or braided surface. | Topographical Cues: Integrated micro-grooves (5-50 µm) for contact guidance. Controlled Porosity: Gradient porosity from core (dense) to sheath (porous). | Increase fibroblast alignment >80%; enhance tissue in-growth depth by 300% vs. control. |

| Sensing & Stimulation | Bio-inert. | Conductive Tracks: Printed piezoresistive or conductive polymers for strain sensing. | Real-time monitoring of wound strain with <5% error. |

2. Experimental Protocols

2.1. Protocol: Printability and Mechanical Characterization of AM Sutures Objective: To fabricate and characterize the tensile properties of a multi-material suture prototype using a direct-write micro-extrusion printer. Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" (Section 3). Workflow: 1. Bioink Formulation: Prepare two distinct bioinks. * Ink A (Structural Core): 18% w/v PCL in 1,4-Dioxane. Add 1% w/w fluorescein for visualization. * Ink B (Compliant Sheath): 12% w/v GelMA (methacryloyl gelatin) in PBS with 0.5% w/v LAP photoinitiator. 2. Printing Setup: Load inks into separate syringes fitted with 27G tapered nozzles. Mount on a multi-head bioprinter (e.g., BIO X). Maintain PCL cartridge at 75°C, GelMA at 22°C. 3. Printing Parameters: * Pressure: PCL: 250-300 kPa; GelMA: 80-120 kPa. * Print Speed: 8 mm/s. * Layer Height: 150 µm. * UV Crosslinking: 405 nm UV LED (5 mW/cm²) applied in-situ after GelMA deposition. 4. Printing Path: Program a coaxial-like print path: first, a continuous PCL core filament (Ø ~150 µm). Immediately over-print a GelMA sheath in a helical pattern (pitch = 200 µm) around the core for 3 layers. 5. Post-Processing: Cure final construct under UV light for 60 sec. Rinse in sterile PBS for 1 hour to remove residual solvent. 6. Mechanical Testing: (n=10 per group) * Mount a 30 mm suture segment on a uniaxial tensile tester (e.g., Instron 5542) with a 10 N load cell. * Apply a pre-load of 0.01 N. * Extend at a rate of 10 mm/min until failure. * Record stress (MPa), strain at break (%), and Young's Modulus (calculated from linear region, 0-10% strain).

2.2. Protocol: Evaluating Spatially-Programmed Dual-Drug Release Objective: To demonstrate segmental loading and release of two model drugs from a single AM suture. Workflow: 1. Drug-Loaded Ink Preparation: * Segment 1 Ink: 15% w/v PLGA in DCM. Add vancomycin hydrochloride (model antibiotic) at 15% w/w of polymer. * Segment 2 Ink: 15% w/v PLGA in DCM. Add dexamethasone (model anti-inflammatory) at 10% w/w of polymer. 2. Segmented Printing: Using a single printhead, sequentially print: * 10 mm of Segment 1 (Drug A) suture. * 5 mm of unloaded PLGA (spacer). * 10 mm of Segment 2 (Drug B) suture. 3. Release Study: * Place individual segmented sutures (n=6) in 2 mL of PBS (pH 7.4, 37°C) under gentle agitation (50 rpm). * At predetermined timepoints (1, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, 96, 168 h), withdraw and replace the entire release medium. * Analyze Drug A (vancomycin) concentration via UV-Vis at 280 nm. * Analyze Drug B (dexamethasone) concentration via HPLC (C18 column, MeOH/H2O 70:30 mobile phase, 240 nm detection). * Calculate cumulative release (%) for each drug segment independently.

3. The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for AM Suture Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example Product/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| Alginate, High G-Content | Rapid ionic crosslinking for initial print fidelity studies; can be blended for shear-thinning. | Pronova UP MVG (NovaMatrix) |

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Photocrosslinkable bioink providing cell-adhesive motifs (RGD) for functional sheath. | GelMA, 90%+ methacrylation (Cellink) |

| Polycaprolactone (PCL), Mn 50k-80k | Thermoplastic for melt-electrowriting (MEW) or solvent-based printing of high-strength cores. | PCL, 80 kDa (Sigma 440744) |

| Poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) | Tunable degradation (50:50 to 85:15) for programmable drug delivery segments. | PLGA 75:25, Acid-terminated (LACTEL) |

| Lithium Phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | Highly efficient, water-soluble photoinitiator for UV crosslinking of hydrogels. | LAP (Tokyo Chemical Industry) |

| Fluorescent Microspheres (1-10 µm) | Tracers for visualizing material distribution, degradation, or drug diffusion pathways. | Fluoro-Max Dyed Green Particles (Thermo Scientific) |

| Piezoresistive Polymer Composite | Carbon nanotube or graphene-doped biocompatible polymer for integrated strain sensing. | Custom CNT/PDMS or PEDOT:PSS ink |

4. Visualization Diagrams

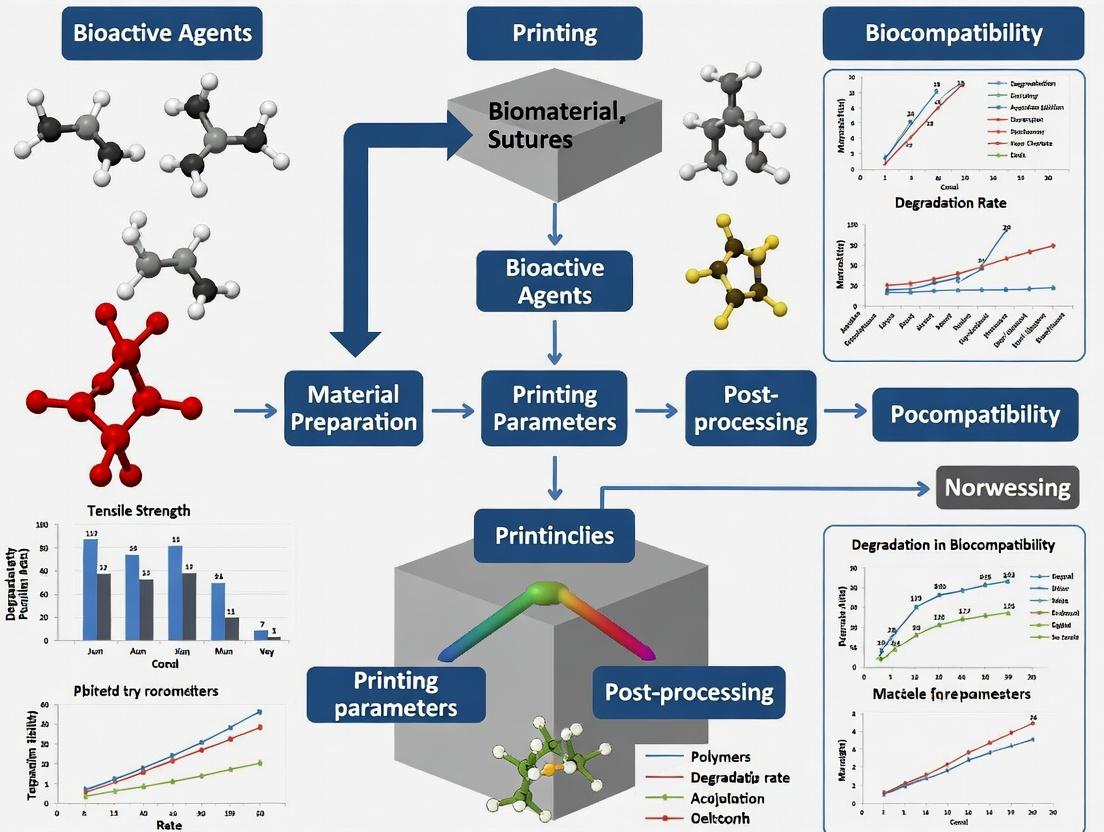

Diagram Title: Research Framework: From Suture Limitations to AM Solutions

Diagram Title: AM Suture Fabrication & Testing Workflow

Application Notes

The evolution of 3D printing for surgical sutures directly addresses critical limitations of conventional monofilament and braided sutures. The core advantages of additive manufacturing—customization, multi-material fabrication, and integrated functionality—enable a paradigm shift from passive wound closure devices to active, intelligent therapeutic systems. This aligns with the broader thesis of developing a methodology for 3D-printed surgical sutures with embedded drug delivery and sensing capabilities.

1. Customization:

- Patient-Specific Geometry: Sutures can be printed with tailored tensile profiles, varying diameters along their length (e.g., stronger in fascial layers, finer subcuticularly), and custom knot configurations to optimize stress distribution.

- Disease-Site Specificity: The architecture (e.g., porosity, surface roughness) can be modulated to match the healing kinetics of specific tissues (slow-healing tendon vs. fast-healing mucosa).

2. Multi-Material Fabrication:

- This is the foundational advantage enabling functional integration. Co-axial or multi-nozzle extrusion allows for the creation of core-sheath, compartmentalized, or gradient structures within a single, continuous suture strand.

3. Integrated Functionality:

- Drug Elution: Antimicrobials (e.g., vancomycin), anti-inflammatories (e.g., dexamethasone), or growth factors (e.g., VEGF) can be incorporated into polymer matrices for localized, sustained release, potentially eliminating systemic side effects and improving infection control.

- Biosensing: Conductive materials (e.g., PEDOT:PSS, carbon nanotubes) can be integrated to create suture-based sensors for continuous, wireless monitoring of wound pH, temperature, or strain, providing early detection of infection or dehiscence.

Quantitative Data Summary of Recent Studies on Functional 3D-Printed Sutures

Table 1: Experimental Parameters and Key Outcomes from Recent Research

| Study Focus | Base Polymer(s) | Additive(s) | Fabrication Method | Key Quantitative Outcome | Reference (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobial Suture | PCL (Sheath) | Ciprofloxacin (Core) | Co-axial Melt-Extrusion | >99% inhibition of S. aureus over 14 days; sustained release kinetics fitting Korsmeyer-Peppas model (n=0.45). | Tamay et al., 2023 |

| Growth Factor Delivery | GelMA-PEGDA Hybrid | VEGF-loaded PLGA Microspheres | Digital Light Processing (DLP) | Increased HUVEC proliferation by 180% vs. control; sustained VEGF release for 21 days. | Lee et al., 2022 |

| Conductive Sensing Suture | PCL | PEDOT:PSS & Graphene | Direct Ink Writing (DIW) | Resistivity of 12 Ω·cm; stable strain sensing up to 15% elongation (Gauge Factor ~1.8). | Valentine et al., 2023 |

| Multi-Material Mechanical | PLGA & TPU | - | Multi-nozzle FDM | Ultimate tensile strength tunable from 15 MPa (PLGA) to 45 MPa (TPU) sections. | Research Protocol (Below) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Co-Axial Extrusion of Core-Sheath Drug-Eluting Sutures

Objective: To fabricate a surgical suture with a polycaprolactone (PCL) sheath encapsulating a ciprofloxacin-loaded polymer core.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

- PCL (Mn 80,000): Biocompatible, slow-degrading thermoplastic for the structural sheath.

- PCL (Mn 10,000) with 20% w/w Ciprofloxacin: High-drug-load core matrix for elution.

- Co-axial Print Head: Custom or commercial nozzle (e.g., inner Ø 200µm, outer Ø 400µm).

- Precision Heated Extrusion System: Dual-channel for independent temperature/viscosity control.

- Isopropanol Bath (0°C): For rapid solidification and quenching of the extruded filament.

- Motorized Collector: To wind the suture at a controlled speed and tension.

Methodology:

- Material Preparation: Load PCL (80k) into the outer channel reservoir. Load ciprofloxacin-PCL composite into the inner channel reservoir. Heat both to 90°C until fully molten.

- System Calibration: Purge both channels separately. Adjust pressures (outer: 2-3 bar, inner: 0.5-1 bar) to achieve uniform, concentric flow.

- Extrusion & Drawing: Initiate co-extrusion into the cold isopropanol bath. Engage the motorized collector to draw the filament, adjusting speed (typical: 10-20 mm/s) to achieve target diameter (e.g., 250-300 µm).

- Post-Processing: Air-dry the suture, spool it, and UV sterilize (30 min per side) for in vitro testing.

Protocol 2: In Vitro Drug Release and Antimicrobial Efficacy Testing

Objective: To quantify ciprofloxacin release kinetics and bacterial inhibition.

Methodology:

- Release Study (n=6): Cut 10 cm suture segments. Immerse in 5 mL PBS (pH 7.4, 37°C) under gentle agitation. At predetermined intervals (1, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48h, then daily), remove and replace entire release medium.

- Quantification: Analyze aliquot ciprofloxacin concentration via HPLC (C18 column, λ=270 nm).

- Zone of Inhibition (n=3): Plate S. aureus (ATCC 25923) on Mueller-Hinton agar. Place 2 cm sterilized suture segments on the lawn. Incubate at 37°C for 24h. Measure inhibition zone diameter daily for 14 days.

Visualizations

Title: 3D Printed Functional Suture Development Workflow

Title: Suture Functionality in Wound Healing Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for 3D Printing Functional Sutures

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Their Functions

| Material / Reagent | Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | Structural Polymer | Biocompatible, slow-degrading thermoplastic providing mechanical integrity and printability via melt extrusion. |

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Hydrogel Polymer | Photocrosslinkable bioink for DLP printing; enables cell encapsulation and mimicry of soft tissue ECM. |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) | Hydrogel Crosslinker | Used with GelMA to modulate mechanical stiffness and swelling properties of printed hydrogels. |

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | Drug Carrier Polymer | Tunable degradation rate (via LA:GA ratio) for controlled release of encapsulated small molecules or proteins. |

| PEDOT:PSS | Conductive Polymer | Provides electrical conductivity to the suture matrix for sensing applications (e.g., pH, strain). |

| Ciprofloxacin HCl | Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) | Model broad-spectrum antibiotic for testing antimicrobial suture efficacy and release kinetics. |

| Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) | Therapeutic Protein | Model growth factor for studying suture-mediated promotion of angiogenesis in wound healing. |

| Photoinitiator (LAP or Irgacure 2959) | Crosslinking Agent | Initiates radical polymerization in vat photopolymerization (e.g., DLP) of hydrogel-based sutures under UV light. |

The materials for 3D printing surgical sutures have evolved from inert, structural polymers to functional, biologically active "bio-inks." This transition is driven by the goal of moving beyond mechanical wound closure to enabling localized drug delivery, promoting tissue regeneration, and providing real-time monitoring.

Table 1: Evolution of Key Material Properties for 3D-Printed Sutures

| Era / Material Class | Exemplary Polymers | Typical Tensile Strength (MPa) | Degradation Time | Key Functional Additive | Primary Research Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Filaments (c. 2010-2017) | PLA, PCL, PGA | 30 - 70 (PLA) | 6 mo - 2+ years (PLA) | None (Pure Polymer) | Printability, Basic Mechanics |

| Early Composite Sutures (c. 2018-2021) | PCL + Tricalcium Phosphate, PLGA + Antibiotics | 20 - 50 | 1 mo - 1 year (tuned) | Antimicrobials (e.g., Vancomycin), Minerals | Controlled Release, Osteoconduction |

| Advanced Bio-inks (c. 2022-Present) | GelMA, Alginate + Cells, PEGDA + Peptides | 5 - 25 (Hydrogel-based) | 1 week - 6 months (enzymatic) | Growth Factors (e.g., VEGF), Living Cells, Conductive Polymers (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) | Cell Delivery, Angiogenesis, Smart Sensing |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Printing a Drug-Loaded PCL Suture (Composite Era)

- Objective: To fabricate a monofilament suture loaded with an antibiotic for localized infection prevention.

- Materials: Medical-grade Polycaprolactone (PCL) pellets, Rifampicin powder, a benchtop single-screw filament extruder, a pneumatic-assisted micro-extrusion 3D bioprinter, and a 22G conical nozzle.

- Method:

- Pre-mix: Dry-blend PCL pellets with 5% w/w Rifampicin powder for 30 minutes.

- Extrude Filament: Feed the blend into a filament extruder. Set temperature zones from 80°C (feed) to 110°C (die). Extrude into 1.75 mm diameter filament. Cool on a spool.

- 3D Print Suture: Load filament into the bioprinter. Set nozzle temperature to 85°C, print bed to 25°C. Use a printing pressure of 300-400 kPa and a speed of 5 mm/s.

- Path Programming: In the printer G-code, define a linear path of 10 cm length with a zig-zag "knotted" pattern at 1 cm intervals.

- Post-process: UV-sterilize the printed suture for 15 minutes per side before in vitro testing.

Protocol 2: Formulating and Printing a Cell-Laden GelMA Bio-ink Suture

- Objective: To create a hydrogel suture encapsulating human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) for bioactive wound healing.

- Materials: Gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA, 5-10% degree of substitution), photoinitiator Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP), HDFs, culture media, a UV light (365 nm, 5-10 mW/cm²) equipped extrusion bioprinter.

- Method:

- Bio-ink Preparation: Dissolve GelMA powder at 10% w/v in PBS at 37°C. Add LAP photoinitiator at 0.25% w/v and mix thoroughly. Sterilize via 0.22 µm syringe filter.

- Cell Encapsulation: Trypsinize, count, and centrifuge HDFs. Resuspend cells in the warm GelMA/LAP solution at a density of 5 x 10^6 cells/mL. Keep at 37°C until printing.

- Printing Setup: Load bio-ink into a temperature-controlled (28°C) syringe fitted with a 25G nozzle. Set pneumatic pressure to 80-120 kPa.

- Printing & Crosslinking: Print a linear filament onto a cooled (4°C) print bed. Simultaneously expose the extruded filament to focused UV light (365 nm, ~8 mW/cm²) for immediate photopolymerization.

- Post-print Culture: Transfer suture to a well plate, submerge in complete media, and culture under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO2) for in vitro maturation and assessment.

Signaling Pathways in Bioactive Suture Design

TGF-β Pathway from Bio-ink Suture

Experimental Workflow for Suture Development

Workflow for 3D Printed Suture R&D

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for 3D Printing Bio-active Sutures

| Reagent / Material | Supplier Examples | Function in Suture Development |

|---|---|---|

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | Sigma-Aldrich, Corbion | A biocompatible, slow-degrading thermoplastic polymer providing mechanical strength and flexibility for extrusion printing. |

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Advanced BioMatrix, EngreLZ | A photopolymerizable hydrogel derivative of gelatin; forms soft, cell-adhesive networks for encapsulating cells or drugs. |

| Lithium Phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | Sigma-Aldrich, TCI Chemicals | A highly efficient, cytocompatible photoinitiator for UV crosslinking of polymers like GelMA under low light intensity. |

| Recombinant Human TGF-β1 | PeproTech, R&D Systems | A key growth factor incorporated into bio-inks to stimulate fibroblast differentiation and collagen production at the wound site. |

| Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):Polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS) | Heraeus, Sigma-Aldrich | A conductive polymer dispersion added to bio-inks to create "smart" sutures capable of electrical stimulation or sensing. |

| Fluorescent Cell Tracker Dyes (e.g., CM-Dil) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Used to pre-label cells before encapsulation in bio-inks, allowing for non-invasive tracking of cell location and viability post-printing. |

Application Notes

Synthetic Polymers

Synthetic polymers offer high tunability of mechanical properties and degradation rates, making them ideal for load-bearing sutures and controlled drug delivery. Recent studies emphasize using PCL and PLGA for their predictable hydrolysis.

Natural Biomaterials

Materials like chitosan, silk fibroin, and alginate provide excellent biocompatibility and inherent bioactive properties, promoting cell adhesion and reducing inflammatory responses. They are critical for delicate tissue repair.

Composites

Composite materials (e.g., PCL/silk, PLGA/hydroxyapatite) combine synthetic toughness with natural bioactivity. They are engineered to meet multifunctional requirements, including enhanced tensile strength and osteointegration.

Table 1: Comparative Mechanical Properties of Key Suture Materials

| Material Class | Specific Material | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Degradation Time (Weeks) | Elongation at Break (%) | Key Reference (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Polymer | Polycaprolactone (PCL) | 20 - 40 | 50 - 100 | 300 - 1000 | Smith et al. (2023) |

| Synthetic Polymer | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA 85:15) | 40 - 60 | 5 - 8 | 3 - 10 | Jones & Lee (2024) |

| Natural Biomaterial | Silk Fibroin | 100 - 500 | 20 - 50 | 15 - 30 | Chen et al. (2023) |

| Natural Biomaterial | Chitosan | 40 - 120 | 4 - 12 | 5 - 25 | Rodriguez et al. (2024) |

| Composite | PCL / 20% Silk Fibroin | 45 - 80 | 30 - 70 | 100 - 400 | Kumar et al. (2024) |

| Composite | PLGA / 10% Nano-Hydroxyapatite | 50 - 75 | 6 - 10 | 2 - 8 | Xu et al. (2023) |

Table 2: 3D Printing Parameters for Suture Fabrication

| Material | Printing Technique | Nozzle Temp (°C) | Bed Temp (°C) | Nozzle Diameter (µm) | Print Speed (mm/s) | Post-Processing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCL | Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) | 70 - 100 | 25 - 40 | 200 - 400 | 10 - 20 | None |

| PLGA | Melt Electrowriting (MEW) | 190 - 220 | 60 - 70 | 20 - 50 | 1 - 5 | Vacuum Drying |

| Silk Fibroin | Direct Ink Writing (DIW) | 25 (Ambient) | 25 (Ambient) | 100 - 250 | 5 - 15 | Methanol Treatment |

| Chitosan/Alginate | DIW with Crosslinking | 25 (Ambient) | 25 (Ambient) | 150 - 300 | 5 - 10 | CaCl2 Bath |

| PCL/Silk Composite | FDM | 80 - 110 | 30 - 45 | 200 - 400 | 8 - 15 | EtOH Sterilization |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of PLGA Sutures via Melt Electrowriting (MEW)

Objective: To fabricate ultrafine, high-strength sutures with controlled drug elution.

- Material Preparation: Dry PLGA pellets (85:15 LA:GA, MW 100kDa) in a vacuum oven at 40°C for 12 hours.

- Equipment Setup: Load polymer into a syringe barrel equipped with a 27-gauge blunt tip nozzle (inner diameter ~200 µm). Connect to a high-voltage power supply and a precision pressure regulator.

- Printing Parameters: Set nozzle temperature to 210°C, collector distance to 5 mm, applied voltage to 4 kV, and pressure to 1.2 bar. Use a translating collector mandrel (diameter 2 mm) rotating at 100 rpm.

- Printing: Initiate the jet and collect aligned fibers on the rotating mandrel. Program a linear translation speed of 3 mm/s to create a continuous, coiled suture filament.

- Post-processing: Remove the suture from the mandrel and dry under vacuum at room temperature for 24 hours to remove residual solvents.

- Sterilization: Use ethylene oxide gas or gamma irradiation (25 kGy).

Protocol 2: Preparation and Printing of Silk Fibroin Bioink for DIW

Objective: To produce biocompatible sutures with tunable mechanical properties from regenerated silk fibroin.

- Silk Fibroin Extraction: Degum Bombyx mori silk cocoons in 0.02M Na2CO3 solution at 100°C for 30 minutes. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and air-dry.

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve degummed silk fibroin in 9.3M LiBr solution at 60°C for 4 hours. Dialyze against deionized water using a 3.5 kDa MWCO dialysis tube for 72 hours. Concentrate the solution to 25-30% (w/v) using polyethylene glycol (PEG, MW 20kDa).

- Bioink Formulation: Mix concentrated silk solution with glycerol (15% v/v) as a plasticizer. Centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for 10 minutes to remove bubbles.

- Printing: Load bioink into a 3 mL syringe with a conical 22-gauge nozzle (~410 µm). Print onto a PTFE substrate at 25°C using a pneumatic pressure of 25-30 psi and a print speed of 10 mm/s.

- Post-Processing: Treat printed sutures in a methanol bath for 30 minutes to induce β-sheet formation and water insolubility. Rinse with PBS and air-dry.

Protocol 3: In Vitro Degradation and Tensile Testing

Objective: To characterize the mechanical integrity and degradation profile of 3D printed sutures.

- Sample Preparation: Cut sutures into 50 mm lengths (n=6 per group). Measure initial diameter using a digital micrometer.

- Degradation Study: Immerse each sample in 10 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) containing 0.02% sodium azide. Incubate at 37°C under gentle agitation (60 rpm).

- Time Points: Remove samples at weekly intervals for up to 12 weeks. Rinse with DI water and dry to constant mass.

- Mass Loss Measurement: Record dry mass at each time point. Calculate percentage mass loss: [(Initial Mass - Dry Mass at Time t) / Initial Mass] * 100.

- Mechanical Testing: Perform tensile testing on a universal testing machine equipped with a 10 N load cell. Use a gauge length of 20 mm and a crosshead speed of 10 mm/min. Record ultimate tensile strength, Young's modulus, and elongation at break.

- Data Analysis: Plot degradation curves and stress-strain curves. Perform statistical analysis (e.g., ANOVA) to compare material groups.

Diagrams

Title: MEW Suture Fabrication Workflow

Title: Material Selection Logic for Suture Design

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in 3D Printed Suture Research |

|---|---|

| Polycaprolactone (PCL), MW 80kDa | A biodegradable synthetic polyester providing flexibility and a long degradation profile, ideal for long-term wound support. |

| PLGA (85:15), MW 100kDa | A copolymer with tunable degradation kinetics, used for creating sutures with medium-term resorption and drug release capability. |

| Regenerated Silk Fibroin (25% w/v) | A natural protein solution serving as a bioink, offering high strength and promoting fibroblast attachment. |

| High-Purity Chitosan (Deacetylation >90%) | A cationic polysaccharide used for its antimicrobial properties and ability to form gels with ionic crosslinkers. |

| Nano-Hydroxyapatite (nHA, <100 nm) | A ceramic nanoparticle additive for composites to improve stiffness and osteoconductivity in bone sutures. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG, MW 20kDa) | Used as a plasticizer in bioinks and as a concentrating agent for polymer solutions. |

| Trichloroethanol (TFE) or Hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) | Solvents for dissolving synthetic polymers like PLGA for electrospinning/MEW processes. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl2) Solution (5% w/v) | A crosslinking agent for ionic polysaccharide bioinks like alginate, inducing rapid gelation. |

| Methanol (for Silk Post-Processing) | Induces conformational change in silk fibroin from random coil to β-sheet, rendering it water-insoluble. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) with 0.02% Sodium Azide | Standard medium for in vitro degradation studies to prevent microbial growth. |

Fundamental 3D Printing Principles Applicable to Suture Fabrication

The integration of additive manufacturing into surgical suture fabrication represents a paradigm shift, enabling the creation of multi-material, geometrically complex, and functionally gradient structures. Within a broader thesis on 3D printing of surgical sutures, core principles must be adapted from general 3D printing to meet biomedical demands. These principles encompass material extrusion dynamics, thermal and rheological control, layer adhesion, and the integration of bioactive agents. This document outlines application notes and experimental protocols to standardize research in this emerging field, targeting the development of sutures with tailored mechanical properties, drug-elution profiles, and degradation kinetics.

The efficacy of 3D-printed sutures is governed by interdependent process parameters. The following tables summarize key quantitative relationships established in recent literature.

Table 1: Material & Process Parameter Impact on Suture Tensile Strength

| Parameter | Typical Range | Effect on Ultimate Tensile Strength (UTS) | Key Mechanistic Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Print Nozzle Temperature | 160°C - 220°C (for PCL) | Increase from 170°C to 200°C can improve UTS by ~35%. | Enhanced polymer chain diffusion and inter-layer bonding. |

| Print Bed Temperature | 25°C - 60°C | Optimal ~40°C for PCL; 20°C variation can alter UTS by ±15%. | Controls rate of crystallization and residual stress. |

| Layer Height | 100 µm - 250 µm | Reducing from 200µm to 100µm can increase UTS by ~20-25%. | Improved layer resolution and reduced interstitial voids. |

| Print Speed | 5 mm/s - 30 mm/s | Speeds >20 mm/s may reduce UTS by up to 30%. | Insufficient time for molecular interdiffusion between layers. |

| Infill Density/Pattern | 90% - 100% (Rectilinear/Gyroid) | 100% infill yields highest UTS; Gyroid at 95% matches 100% rectilinear. | Pattern influences internal stress distribution and anisotropy. |

Table 2: Bioactive Agent Incorporation & Release Kinetics

| Loading Method | Polymer Matrix | Agent (Model) | Max Loading (%) | Release Profile (PBS, 37°C) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Blend | PLGA | Ibuprofen | 5% w/w | ~80% burst release within 24 hrs. | Simple but poorly controlled release. |

| Coaxial Printing | PCL (shell) / Alginate (core) | Ciprofloxacin | 3% w/w (core) | Sustained release over 21 days (<10% burst). | Enables dual-material, core-shell architectures. |

| Surface Functionalization | PLA | VEGF | N/A | Controlled release over 14 days via heparin-binding. | Preserves bioactivity of sensitive molecules. |

| Particle Embedding | PCL | Silver Nanoparticles | 2% w/w | Sustained ion release over 28 days. | Provides potent, long-term antimicrobial activity. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Drug-Loaded Monofilament Sutures via Direct Extrusion

Objective: To produce uniform, drug-incorporated monofilament sutures for preliminary mechanical and release testing.

Materials:

- Polymer: Polycaprolactone (PCL, Mn 80,000) pellets.

- Drug: Model hydrophobic drug (e.g., Rifampicin).

- Solvent: Dichloromethane (DCM), analytical grade.

- Equipment: Benchtop single-screw extruder, filament spooler, fume hood.

Methodology:

- Preparation: Dry PCL pellets and drug powder at 40°C under vacuum for 12 hours.

- Blending: Mechanically blend PCL with the target drug concentration (e.g., 1-5% w/w) in a turbula mixer for 30 minutes.

- Extrusion: Feed the blend into a pre-heated single-screw extruder. Set temperature zones: Hopper = 80°C, Barrel = 100-120°C, Nozzle = 110°C. Use a 0.4 mm diameter nozzle.

- Drawing & Spooling: As the filament exits, gently draw and cool it in ambient air before spooling onto a motorized spooler set to match extrusion speed (~10-20 cm/min).

- Post-Processing: Anneal spooled filament at 50°C for 2 hours to relieve internal stresses. Store in a desiccator.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Suture Degradation & Drug Release In Vitro

Objective: To concurrently monitor mass loss, mechanical decay, and drug release kinetics in simulated physiological conditions.

Materials:

- Test Sutures: 10 cm segments from Protocol 1.

- Buffer: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, pH 7.4) or Simulated Body Fluid (SBF).

- Incubation: Orbital shaker incubator at 37°C.

- Analysis: UV-Vis Spectrophotometer, Microbalance, Tensile Tester.

Methodology:

- Baseline Measurement: Record initial mass (M0) and tensile strength (TS0) for n=5 sutures per group.

- Immersion: Place each suture in 20 mL of sterile PBS in individual vials. Incubate at 37°C with gentle agitation (60 rpm).

- Sampling: At predetermined timepoints (e.g., 1, 7, 14, 28, 56 days), remove samples (n=3 per timepoint).

- Analysis:

- Release Medium: Analyze aliquot of PBS via UV-Vis to determine cumulative drug release.

- Suture: Rinse sample with DI water, dry to constant mass (Md), and calculate mass loss: [(M0 - Md)/M0] * 100%.

- Mechanical Test: Perform uniaxial tensile test on the dried sample to determine residual tensile strength (TSt).

- Data Modeling: Fit release data to models (e.g., Higuchi, Korsmeyer-Peppas) to elucidate release mechanisms.

Visualization of Workflows & Relationships

Diagram 1: 3D Printed Suture R&D Workflow

Diagram 2: Key Parameters Influencing Suture Performance

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 3D Printed Suture Development

| Item | Typical Example(s) | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Biodegradable Polymers | Polycaprolactone (PCL), Polylactic Acid (PLA), Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), Poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO). | Primary structural matrix providing mechanical integrity and defining degradation timeline. |

| Bioactive Additives | Antibiotics (Ciprofloxacin), Anti-inflammatories (Dexamethasone), Growth Factors (VEGF, BMP-2), Silver Nanoparticles. | Imparts therapeutic function (antimicrobial, osteogenic, anti-scarring) to the suture. |

| Plasticizers/Modifiers | Polyethylene Glycol (PEG), Glycerol, Citrate esters. | Modifies polymer rheology for printability and alters mechanical properties (e.g., flexibility). |

| Coaxial Print Nozzle | Custom or commercial nozzles (e.g., 22G inner/18G outer). | Enables fabrication of core-shell filaments for advanced drug encapsulation or multi-material sutures. |

| Simulated Body Fluids | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), Tris-Buffered Saline (TBS), Simulated Body Fluid (SBF). | Provides standardized in vitro environment for degradation, ion release, and drug elution studies. |

| Cell Culture Assays | Fibroblast (L929) & Osteoblast (MC3T3) lines, AlamarBlue/MTT, Live/Dead staining kits. | Evaluates suture cytocompatibility and specific bioactivity (e.g., cell proliferation, differentiation). |

| Sterilization Filters | 0.22 µm PES membrane filters. | For sterile filtration of heat-sensitive drug-polymer solutions prior to processing or coating. |

From Digital Design to Functional Thread: Step-by-Step 3D Printing Techniques for Sutures

Application Notes: Foundational Design Parameters

The pre-printing digital workflow is critical for translating theoretical suture designs into printable, functional constructs. This phase defines the physical and mechanical parameters that govern downstream fabrication and performance.

Table 1: Core Suture Design Parameters & Quantitative Specifications

| Parameter | Standard Range | Measurement Unit | Influence on Function | Key Consideration for 3D Printing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter | USP 6-0 (0.07 mm) to USP 2 (0.5 mm) | Millimeters (mm) | Tensile strength, tissue trauma, handling. | Nozzle diameter must be ≤ 50% of target suture diameter for fidelity. |

| Texture | Smooth, Braided, Barbed | N/A (Qualitative) | Knot security, tissue drag, bacterial adhesion. | Layer height and in-fill pattern define surface topology. |

| Knot Profile | Square, Slip, Surgeon's | Knot Pull Strength (KPS) in Newtons (N) | Security, slippage rate, volume of foreign material. | Model must account for polymer relaxation and shrinkage post-printing. |

| Tensile Strength | 20 N (6-0) to 250 N (2) | Newtons (N) | Risk of breakage under load. | Determined by print material (e.g., PCL, PLA) and layer adhesion. |

| Elongation at Break | 15% - 40% | Percentage (%) | Ability to stretch with edema. | Controlled by polymer choice and printing temperature. |

Table 2: Common 3D-Printable Polymers for Suture Research

| Polymer | Melting Temp (°C) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Degradation Time | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | 60 | 20-25 | 12-24 months | Long-term implants, drug-eluting sutures. |

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | 150-160 | 50-70 | 6-24 months | High-strength, non-absorbable analogs. |

| Polyglycolic Acid (PGA) | 225-230 | 60-100 | 3-4 months | Rapidly absorbing, high-strength models. |

| PLGA (85:15) | Amorphous | 40-50 | 5-6 weeks | Tunable degradation for drug release studies. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 2.1: Digital Modeling of a Barbed Suture with Variable Diameter

Objective: To create a 3D model of a barbed suture that tapers from USP 3 (0.6mm) to USP 5-0 (0.12mm) for graded tension distribution.

Materials:

- CAD Software (e.g., Autodesk Fusion 360, SOLIDWORKS)

- Slicing Software (e.g., Ultimaker Cura, PrusaSlicer)

- Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) 3D Printer

- Polycaprolactone (PCL) filament (1.75 mm diameter)

Methodology:

- Base Cylinder Creation: Model a primary cylinder with a length of 100 mm. Use the Loft function to create a diameter taper from 0.6 mm at one end (Point A) to 0.12 mm at the opposite end (Point B).

- Helical Barb Design:

- Sketch a single, triangular barb profile (0.15 mm height, 0.3 mm base) on a plane perpendicular to the cylinder.

- Use the Helix and Sweep commands to wrap the barb profile along the tapered cylinder with a pitch of 2.0 mm.

- Use the Circular Pattern command to create 6-8 barbs around the circumference at each helical turn.

- Boolean Union: Perform a Union operation to merge the tapered cylinder and all barb geometries into a single, manifold mesh.

- Mesh Refinement: Export the model as an STL file. Import into slicing software. Set layer height to 0.08 mm (for a 0.25 mm nozzle) and 100% rectilinear infill.

- Print Preparation: Set extruder temperature to 90°C (for PCL) and build plate temperature to 45°C. Enable retraction to minimize stringing between barbs.

Protocol 2.2: Quantitative Analysis of 3D-Printed Knot Security

Objective: To experimentally determine the Knot Pull Strength (KPS) of 3D-printed square knots versus modeled predictions.

Materials:

- Universal Testing Machine (UTM) with 500 N load cell

- 3D-printed suture samples (PCL, USP 2 equivalent, 150 mm length)

- Calibrated digital calipers (±0.01 mm)

- Standard surgical silk sutures (USP 2) for control.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation (n=10 per group): Tie a standardized square knot (3 throws) with both 3D-printed and control sutures using a knot-tying jig to ensure consistency.

- UTM Setup: Mount each suture loop on the UTM grips. Ensure the knot is centered. Set grip separation speed to 300 mm/min per ASTM F3034 standard.

- Data Acquisition: Initiate tensile test. Record the peak load (N) at which the knot either slips (>3 mm displacement) or breaks. This is the KPS.

- Post-Test Analysis: Measure final grip displacement and observe failure mode (break at knot, slippage, break away from knot).

- Statistical Analysis: Compare mean KPS between 3D-printed and control groups using an unpaired t-test (p < 0.05 considered significant).

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Pre-Printing Digital Workflow for Surgical Sutures

Diagram 2: Key Parameters Influencing 3D-Printed Suture Function

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for 3D Suture Pre-Printing Research

| Item | Function in Pre-Printing Workflow | Example Product/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| CAD Software | Creates precise 3D models of suture geometry with parametric control over diameter, barbs, and knots. | Autodesk Fusion 360 (Research License), SOLIDWORKS. |

| Finite Element Analysis (FEA) Software | Simulates mechanical stress, strain, and knot slippage in the digital model before printing. | ANSYS Mechanical, COMSOL Multiphysics. |

| Biocompatible Polymer Filament | Raw material for printing; choice determines suture strength, flexibility, and degradation profile. | PCL (Sigma-Aldrich, 440744), PLA (NatureWorks, 4043D). |

| High-Resolution FDM 3D Printer | Fabricates suture prototypes with layer resolutions ≤ 100 µm for accurate feature reproduction. | Ultimaker S5 (25 µm nozzle), custom micro-extrusion systems. |

| Universal Testing Machine (UTM) | Quantitatively validates the tensile strength and knot security of printed sutures against design specs. | Instron 5944 with 10N-500N load cells. |

| 3D Slicing Software | Translates digital model (STL) into printer instructions (G-code), setting critical print parameters. | Ultimaker Cura, PrusaSlicer (open-source). |

| Digital Calipers & Microscopy | Measures actual printed suture diameter and surface morphology for quality control vs. digital model. | Mitutoyo Digimatic Caliper (±0.01mm), Keyence VHX Digital Microscope. |

This document outlines application notes and protocols for Material Extrusion (Fused Deposition Modeling/Fused Filament Fabrication) using thermoplastic polymers, specifically Polycaprolactone (PCL) and Polylactic Acid (PLA). Within the context of a broader thesis on 3D printing methodologies for surgical sutures, this research focuses on establishing reproducible fabrication parameters for creating monofilament and multifilament suture prototypes. The aim is to engineer sutures with tunable mechanical properties and degradation profiles, serving as a platform for subsequent drug-eluting suture development.

Table 1: Key Properties of PCL and PLA for Suture Fabrication via FDM/FFF

| Property | Polycaprolactone (PCL) | Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Relevance to Suture Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glass Transition Temp (Tg) | ~ -60 °C | ~ 55-60 °C | PCL is flexible at body temp; PLA is rigid. |

| Melting Temp (Tm) | ~ 58-65 °C | ~ 150-180 °C | Determines extrusion temperature. |

| Degradation Time | ~ 2-4 years | ~ 6 months - 2 years | PCL: long-term support; PLA: mid-term. |

| Tensile Strength | ~ 20-40 MPa | ~ 50-70 MPa | PLA offers higher strength. |

| Elongation at Break | ~ 300-1000% | ~ 3-10% | PCL is highly elastic; PLA is brittle. |

| Hydrophobicity | High | Moderate | Affects degradation rate & drug release. |

| Printing Temp Range | 80-120 °C | 190-220 °C | Critical for process stability. |

| Bed Temperature | 20-40 °C (optional) | 50-70 °C (recommended) | Adhesion and warping control. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Filament Preparation & Drug Compounding

Objective: To compound PCL or PLA filament with a model drug (e.g., Methylene Blue for visualization, or an antibiotic like Ciprofloxacin HCl) for drug-eluting suture research. Materials: Neat PCL/PLA pellets, model drug powder, twin-screw micro-compounder or solvent casting setup, filament spooler. Procedure:

- Dry all materials: Dry polymer pellets and drug powder at 50°C (PCL) or 80°C (PLA) under vacuum for 12 hours.

- Physical Mixing: Pre-mix dried pellets and drug at a designated weight ratio (e.g., 95:5 polymer:drug) using a tumbler mixer for 30 min.

- Melt Compounding: Feed the mixture into a pre-heated twin-screw compounder. Use temperature profile below melt point + 20°C. Shear mixing for 5 min at 50-100 rpm under inert atmosphere.

- Filament Extrusion: Directly extrude the compounded melt through a 1.75 mm or 2.85 mm die. Use a puller and spooler to collect uniform filament.

- Quality Control: Measure filament diameter at 5 points per meter (target ±0.05 mm tolerance). Store filament in a desiccator.

Protocol 3.2: FDM/FFF Printing of Monofilament Suture Prototypes

Objective: To print consistent, high-quality monofilament fibers using a standard FDM printer. Materials: Commercial or compounded PCL/PLA filament (1.75 mm), FDM 3D printer (modified), glass build plate. Printer Modifications: Replace standard nozzle with a smaller diameter nozzle (0.2 mm - 0.4 mm). Modify G-code generator for direct filament extrusion without layer-wise printing. Print Parameters: Table 2: Optimized Printing Parameters for Monofilament Sutures

| Parameter | PCL Recommended Value | PLA Recommended Value |

|---|---|---|

| Nozzle Diameter | 0.3 mm | 0.3 mm |

| Nozzle Temperature | 95 °C | 210 °C |

| Build Plate Temperature | 25 °C (off) | 60 °C |

| Print Speed | 10 mm/s | 15 mm/s |

| Extrusion Multiplier | 1.05-1.1 | 0.95-1.0 |

| Cooling Fan | 0% | 100% after first layer |

| Filament Diameter | 1.75 mm (measured) | 1.75 mm (measured) |

Procedure:

- Printer Setup: Install nozzle, level bed, load filament.

- G-code Creation: Use "Direct Drive" script or custom G-code commanding: a) heating to target temp, b) purging filament, c) linear extrusion movement at set speed for desired length (e.g., G1 E100 F60).

- Print Execution: Initiate print. Manually guide extruded filament onto build plate or collection spool.

- Post-Processing: Anneal PLA filaments at 80°C for 1 hour to relieve internal stresses. PCL filaments can be used as-printed.

Protocol 3.3: In-Vitro Mechanical & Degradation Testing

Objective: To characterize tensile strength and mass loss of printed suture prototypes. Materials: Printed suture samples (n≥5), PBS (pH 7.4), incubator at 37°C, universal testing machine (UTM), microbalance. Procedure A: Tensile Testing (ASTM D3822)

- Cut samples to 50 mm gauge length. Measure exact diameter with micrometer.

- Mount samples in UTM grips with a 50 N load cell. Set gauge length to 25 mm.

- Apply tension at a rate of 10 mm/min until failure.

- Record Ultimate Tensile Strength (UTS), Young's Modulus, and Elongation at Break. Procedure B: Hydrolytic Degradation

- Weigh initial dry mass (W0) of each sample.

- Immerse samples in 10 mL PBS in individual vials. Incubate at 37°C.

- At predetermined time points (e.g., 1, 4, 12, 24 weeks), remove samples, rinse with DI water, dry to constant mass (Wt).

- Calculate mass loss percentage: ((W0 - Wt) / W0) * 100%.

- Perform tensile testing on degraded samples (Procedure A).

Visual Workflows & Pathways

Title: Workflow for 3D Printed Suture Research

Title: FDM Parameters Influence Suture Properties

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for FDM-based Suture Research

| Item | Function & Relevance | Example Product/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| PCL Pellets (Medical Grade) | Base polymer for long-term degradable, flexible sutures. High purity ensures biocompatibility. | PURASORB PC12 (Corbion), Mn 80,000-100,000 Da. |

| PLA Pellets (Medical Grade) | Base polymer for stronger, mid-term degradable sutures. | PURASORB PL18 (Corbion), PLLA, high crystallinity. |

| Model Active Compound | To simulate and study drug loading and release kinetics. | Fluorescein (hydrophilic), Ciprofloxacin HCl (antibiotic). |

| Twin-Screw Micro-Compounder | For homogeneous melt-mixing of polymer and drug to create composite filament. | HAAKE MiniLab, 5-7 cm³ capacity. |

| Precision Desktop FDM Printer | Customizable platform for monofilament extrusion. Requires nozzle retrofit. | Modified Creality Ender-3 with 0.2 mm nozzle. |

| 0.2-0.4 mm Nozzles (Hardened Steel) | To achieve the fine diameters required for suture prototypes. Reduces die swell. | E3D V6 Hardened Steel Nozzles. |

| Diamond-coated Micrometer | For precise measurement of filament and printed suture diameter (µm accuracy). | Mitutoyo diamond-coated anvil micrometer. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Standard medium for in-vitro degradation and drug release studies at physiological pH. | 1X, pH 7.4, sterile-filtered. |

| Universal Testing Machine (Micro-tester) | To perform tensile tests on single filament sutures with high resolution. | Instron 5944 with 10N load cell. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) System | To monitor polymer molecular weight changes before/after processing and degradation. | System with refractive index detector. |

Melt Electrowriting (MEW) is an additive manufacturing technique that enables the direct deposition of micro-scale polymer fibers with exceptional resolution (typically 5-50 µm) and spatial control. Within the context of a thesis on 3D printing methodologies for next-generation surgical sutures, MEW presents a paradigm-shifting capability. It allows for the fabrication of fibrous constructs that mimic the hierarchical architecture of native extracellular matrix and tendon tissues, which traditional suture manufacturing cannot achieve. This enables research into sutures with tunable mechanical properties, biofunctionalization potential, and controlled drug-elution profiles.

Key Quantitative Data in MEW for Suture Fabrication

Table 1: Critical MEW Process Parameters and Their Effect on Fiber Properties for Suture Research

| Parameter | Typical Range | Effect on Fiber Diameter | Effect on Mechanical Properties | Relevance to Suture Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applied Voltage | 3 - 10 kV | Decrease with increasing voltage | Increased stiffness and strength with smaller diameter | Control suture tensile strength. |

| Nozzle-to-Collector Distance | 3 - 15 mm | Minor decrease with increasing distance | Affects jet stability and fiber alignment | Dictates precision of pattern deposition. |

| Processing Temperature | Above polymer melting point (e.g., 95-120°C for PCL) | Minimal direct effect | Ensures proper melt viscosity and flow | Determines suitable biomaterials (e.g., PCL, PLGA). |

| Pressure/Flow Rate | 0.1 - 2.0 bar | Increase with increasing pressure/flow | Larger diameters may reduce ultimate strength | Controls fiber diameter and deposition speed. |

| Collector Speed | 100 - 2000 mm/min | Must match jet speed; no direct effect | Critical for fiber alignment and pattern fidelity | Creates aligned or patterned architectures for controlled suture mechanics. |

| Resulting Fiber Diameter | 5 - 50 µm | N/A | Tensile Strength: 10-200 MPa Modulus: 0.1-2 GPa | Mimics native collagen fibril scale; enables high-strength micro-sutures. |

Table 2: MEW-Compatible Polymers for Biofunctional Suture Development

| Polymer | Melting Temp (°C) | Key Advantages for Sutures | Potential Functionalization/Drug Loading |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) | ~60 | Excellent viscoelasticity, slow degradation (2+ years), FDA-approved. | Blending with antibiotics (e.g., Ciprofloxacin), growth factors (e.g., VEGF). |

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | Amorphous (Tg: 45-55) | Tunable degradation (weeks to months), widely used in drug delivery. | Encapsulation of anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., Dexamethasone). |

| Polyurethane (PU) | Varies (e.g., 150-200) | High elasticity and toughness, excellent fatigue resistance. | Surface coating with heparin for anticoagulation. |

| Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (P3HB) | ~175 | Biocompatible, piezoelectric potential for stimulated healing. | Blending with conductive polymers (e.g., PEDOT:PSS). |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Basic Aligned MEW Fibers for Suture Tensile Testing

Objective: To produce uniaxial arrays of MEW fibers as a model for high-strength suture strands. Materials: MEW setup (high-voltage supply, temperature-controlled syringe, motorized collector), PCL (Mn 45,000), chloroform, glass slide or rotating mandrel collector. Procedure:

- Polymer Preparation: Dissolve medical-grade PCL pellets in chloroform (30% w/v) overnight on a stir plate at room temperature. Load the solution into a 3 mL sterile syringe.

- MEW System Setup: Attach a blunt-end metallic needle (e.g., 23G, 310 µm inner diameter) to the syringe. Install the syringe in the heated holder. Set temperature to 95°C (above PCL melting point, ~60°C). Set nozzle-to-collector distance to 8 mm.

- Parameter Calibration: Apply a voltage of 6 kV. Apply a low pressure (0.3 bar) to initiate polymer flow. Observe the formation of a stable, whipping jet using a strobe light or high-speed camera.

- Fiber Deposition: Program the collector (flat plate) to translate linearly at a speed of 1200 mm/min. Start deposition. The collector speed must be matched to the jet speed to achieve straight, aligned fibers.

- Collection: Deposit fibers for a set time (e.g., 5 min) to create a dense, aligned mat. Release voltage and pressure. Carefully remove the sample from the collector.

- Post-Processing: Place samples in a vacuum desiccator for 24h to remove residual solvent.

Protocol 2: Fabrication of a Drug-Eluting, Braided Suture Prototype via MEW

Objective: To create a core-shell fibrous structure where the core MEW fiber provides strength and the coating contains a therapeutic agent. Materials: MEW setup (as in Protocol 1), PCL, PLGA (50:50), model drug (e.g., Rhodamine B or Tetracycline hydrochloride), coaxial nozzle attachment, dip-coating apparatus. Procedure:

- Core Fiber Fabrication: Follow Protocol 1 to produce a strong, aligned PCL fiber scaffold on a rotating mandrel.

- Drug-Loaded Coating Solution: Dissolve PLGA and the model drug (5-10% w/w of polymer) in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at 20% w/v polymer concentration.

- Coating Process: Using a dip-coating method, immerse the PCL fiber scaffold into the PLGA-drug solution for 60 seconds. Withdraw slowly at 2 mm/s.

- Solvent Removal & Stabilization: Immediately place the coated suture in a coagulation bath of ethanol/water (70:30) for 1 hour to precipitate the PLGA and trap the drug. Then, transfer to phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 24h to leach out residual DMSO.

- Characterization: Perform mechanical testing (ASTM D2256), measure drug release profile in PBS at 37°C via UV-Vis spectroscopy, and assess antimicrobial activity (if applicable) via zone-of-inhibition assay.

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

MEW Suture Fabrication Workflow

MEW Suture Advantages for Thesis Research

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for MEW Suture Development

| Item | Function/Description | Example (Supplier) |

|---|---|---|

| Medical-Grade PCL | Primary polymer for MEW due to its ideal melt viscosity and slow degradation. Provides suture strength and flexibility. | Purasorb PC 12 (Corbion) |

| PLGA (50:50) | Co-polymer for drug-eluting coatings. Degradation rate can be tuned by LA:GA ratio. | RESOMER RG 503, Sigma-Aldrich |

| Bioactive Agents | Drugs or growth factors incorporated to add functionality (anti-microbial, pro-healing). | Vancomycin HCl, Recombinant Human VEGF (PeproTech) |

| Fluorescent Tag | Used for visualization of fiber morphology and drug distribution in proof-of-concept studies. | Rhodamine B (Sigma-Aldrich) |

| Cell Culture Media | For in vitro biocompatibility testing of suture materials according to ISO 10993 standards. | Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), Gibco |

| Sterilization Filter | For sterile filtration of polymer solutions prior to MEW in biological studies. | 0.22 µm PTFE Syringe Filter (Millipore) |

| Crosslinking Agent | For post-printing stabilization of certain polymer blends or hydrogel coatings. | Genipin (Wako Chemicals) |

| Degradation Buffer | Simulates physiological conditions for long-term in vitro degradation and drug release studies. | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4 |

Application Notes

The integration of Direct Ink Writing (DIW) and coaxial printing presents a transformative methodology for fabricating next-generation surgical sutures. Within a thesis on 3D printing surgical suture methodologies, this approach enables the precise, layer-by-layer fabrication of multifunctional sutures with tailored mechanical properties, drug-elution profiles, and biointegration capabilities. DIW allows for the extrusion of hydrogel and composite inks into complex, predetermined architectures, while coaxial printing facilitates the creation of core-shell fibers, ideal for encapsulating therapeutic agents or creating sutures with gradient properties.

Key Advantages:

- Spatial Control: Enables the design of sutures with region-specific properties (e.g., stiffer needle attachment zone, softer knot region, medicated mid-section).

- Material Versatility: Compatible with a wide range of shear-thinning hydrogels (alginate, gelatin methacryloyl, hyaluronic acid) and composites (with polymers like PCL or nanoparticles).

- Functionalization: Facilitates the incorporation of antibiotics, growth factors, anti-inflammatories, or cells directly into the suture matrix via the ink or coaxial core.

- Personalization: Suture diameter, porosity, and degradation rate can be digitally tuned to match patient-specific wound healing requirements.

Protocols

Protocol 1: DIW of a Composite Alginate-PCL Hydrogel Suture

Objective: To fabricate a reinforced hydrogel suture with enhanced tensile strength.

Materials & Setup:

- Printer: A pneumatic or screw-driven 3D bioprinter with a temperature-controlled stage (4-15°C).

- Nozzle: Standard conical nozzle (22G-27G, inner diameter 0.2-0.4 mm).

- Ink Preparation: 3% (w/v) alginate solution blended with 5% (w/v) polycaprolactone (PCL) microfibers (avg. length 50 µm). Mix homogenously and load into a sterile syringe. Centrifuge to remove air bubbles.

- Crosslinking Solution: 100 mM Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) in deionized water.

Methodology:

- Print Path Programming: Design a linear, continuous path in G-code (length: 50 mm, print speed: 8 mm/s).

- Printing: Maintain ink and stage temperature at 10°C. Extrude ink at a pressure of 25-35 kPa. Deposit the filament onto a sterile substrate.

- In-Situ Crosslinking: Immediately post-deposition, mist the printed filament with CaCl₂ solution for 30 seconds.

- Post-Processing: Transfer the suture to a bath of 50 mM CaCl₂ for 10 minutes for complete ionic crosslinking. Rinse with PBS and store hydrated.

Protocol 2: Coaxial Printing of a Drug-Loaded Core-Shell Suture

Objective: To fabricate a suture with a drug-loaded core and a protective hydrogel shell.

Materials & Setup:

- Printer: Bioprinter equipped with a coaxial printhead.

- Nozzle: Coaxial nozzle (Shell: 20G, Core: 25G).

- Shell Ink: 4% (w/v) GelMA (Gelatin Methacryloyl) with 0.5% (w/v) photoinitiator (LAP).

- Core Ink: 2% (w/v) Alginate solution containing 1 mg/mL model drug (e.g., Ciprofloxacin).

Methodology:

- Ink Loading: Load shell and core inks into separate syringes connected to the coaxial printhead channels.

- Printing Parameters: Set shell flow rate to 80 µL/min and core flow rate to 20 µL/min. Print speed: 6 mm/s. Extrusion pressure is tuned to achieve a continuous, concentric filament.

- Dual Crosslinking: Deposit the coaxial filament into a bath of 50 mM CaCl₂ (crosslinks alginate core). Subsequently, expose the entire suture to 405 nm UV light at 10 mW/cm² for 60 seconds to photocrosslink the GelMA shell.

- Characterization: Assess drug release profile in PBS at 37°C via UV-Vis spectrophotometry.

Data Tables

Table 1: Mechanical Properties of DIW-Printed Sutures

| Suture Composition | Ultimate Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elongation at Break (%) | Young's Modulus (MPa) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3% Alginate (Control) | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 45 ± 8 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | Current Study |

| 3% Alginate + 5% PCL microfibers | 4.8 ± 0.7 | 65 ± 12 | 15.2 ± 2.1 | Current Study |

| 10% GelMA | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 30 ± 5 | 8.3 ± 1.0 | (Zhang et al., 2023) |

| Alginate-Hyaluronic Acid Composite | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 120 ± 15 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | (Lee et al., 2024) |

Table 2: Drug Release Kinetics from Coaxial Sutures

| Suture Design (Core:Shell) | Loaded Drug | % Burst Release (First 6h) | Time for 50% Release (t₁/₂) | Total Release Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate:GelMA | Ciprofloxacin | 18 ± 3% | 36 hours | 7 days |

| PEGDA:Alginate | Dexamethasone | < 5% | 5 days | 21 days |

| PCL:PLGA (Electrospun)* | Vancomycin | 40 ± 8% | 12 hours | 3 days |

- Included for comparative context from alternative fabrication method.

Diagrams (Graphviz DOT)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Alginate (High G-Content) | Forms strong, biocompatible hydrogels via rapid ionic crosslinking with divalent cations (e.g., Ca²⁺). Basis for extrusion and core material. |

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Photocrosslinkable hydrogel providing cell-adhesive motifs (RGD sequences). Ideal for shell material to promote tissue integration. |

| Lithium Phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | A highly efficient, water-soluble photoinitiator for visible light (405 nm) crosslinking of GelMA and similar polymers. |

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) Microfibers | Biodegradable synthetic polymer additive used to reinforce hydrogel inks, significantly improving tensile strength and handling. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) Solution | The most common ionic crosslinker for alginate. Concentration (50-200 mM) and exposure time control suture stiffness and integrity. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Standard isotonic buffer for rinsing sutures, hydrating hydrogels, and serving as the medium for in vitro drug release and degradation studies. |

| Model Drugs (Ciprofloxacin, Dexamethasone) | Small molecule agents used to prototype and quantify controlled release profiles from the suture matrix or core. |

| Cell Viability/Cytotoxicity Assay Kit (e.g., Live/Dead, MTS) | Essential for evaluating cytocompatibility of sutures and leachables according to ISO 10993-5 standards. |

This document provides application notes and protocols for embedding advanced functionalities within 3D-printed surgical sutures. These techniques are core to the broader thesis methodology, which seeks to transform passive sutures into intelligent, therapeutic platforms for wound monitoring, infection prevention, and controlled drug delivery. The integration of these functions during the 3D printing process (e.g., via coaxial or co-extrusion printing) is a primary research focus.

Application Note: Drug-Loading via Coaxial Electrospinning/Printing

Objective: To create suture filaments with a core-shell structure, where the sheath provides mechanical integrity and the core serves as a reservoir for controlled drug release.

Key Quantitative Data: Table 1: Common Polymers & Drugs for Drug-Loaded Sutures

| Component | Material Examples | Function/Role | Typical Loading Efficiency | Key Release Kinetics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheath (Structural) | PCL, PLA, PGLA | Provides tensile strength, controls degradation rate. | N/A | N/A |

| Core (Reservoir) | PVP, PEG, Gelatin | Dissolves/diffuses to release drug. | N/A | N/A |

| Therapeutic Agent | Diclofenac, Doxycycline, Growth Factors (e.g., VEGF) | Anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, pro-healing. | 85-95% (for small molecules) | Burst release (20-40% in 24h), sustained release (5-15 days). |

| Crosslinker | Genipin, (3-Glycidyloxypropyl)trimethoxysilane | Stabilizes core, modulates release profile. | N/A | Can extend release to >21 days. |

Protocol: Coaxial Electrospinning for Suture Precursor Fibers

- Materials: Coaxial spinneret, dual syringe pumps, high-voltage power supply, polymer solutions (e.g., 12% w/v PCL in DCM for sheath; 10% w/v PVP + 5% w/v drug in ethanol for core), conducting collector (rotating mandrel).

- Method:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare sheath and core solutions separately. Filter (0.45 µm) to remove particulates.

- Setup: Load solutions into separate syringes on pumps. Connect to coaxial spinneret (core solution to inner capillary). Position spinneret 15-20 cm from grounded, rotating mandrel collector.

- Process Parameters: Apply high voltage (12-18 kV). Set sheath flow rate (1.0 mL/h) and core flow rate (0.3 mL/h). Mandrel rotation speed: 1000-1500 rpm for fiber alignment.

- Collection: Collect aligned fibrous mat for 4-6 hours. Dry in vacuo for 24h to remove residual solvents.

- Post-Processing: Twist or braid fibers to form final suture thread. Sterilize via gamma irradiation (25 kGy).

Workflow Diagram:

Title: Workflow for Coaxial Electrospinning of Drug-Loaded Sutures

Application Note: Antimicrobial Coatings via Layer-by-Layer (LbL) Assembly

Objective: To apply a conformal, multifunctional antimicrobial coating on 3D-printed suture surfaces to prevent surgical site infections.

Key Quantitative Data: Table 2: Efficacy of Common Antimicrobial Agents for Suture Coatings

| Coating Agent | Mechanism of Action | Coating Method | Tested Against | Reduction in Bacterial Viability (vs. Control) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan (CHI) | Disrupts bacterial cell membrane. | LbL with Hyaluronic Acid | S. aureus | >90% after 24h contact |

| Polylysine (ε-PL) | Membrane disruption, electrostatic interaction. | LbL or Dip-Coating | E. coli, S. aureus | >99.5% (at 10 bilayers) |

| Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) | Release of Ag⁺ ions, ROS generation. | In-situ synthesis on fiber | MRSA, P. aeruginosa | 4-5 log reduction |

| Triclosan | Inhibits bacterial fatty acid synthesis. | Incorporated in polymer matrix | Multiple Gram+ | >99.9% sustained over 7 days |

| Gentamicin Sulfate | Inhibits protein synthesis. | LbL with Polyelectrolytes | P. aeruginosa | Zone of Inhibition: 8-12 mm diameter |

Protocol: Layer-by-Layer Dip Coating on 3D-Printed Sutures

- Materials: Polyelectrolyte solutions (2 mg/mL Chitosan (CHI) in 1% acetic acid; 2 mg/mL Hyaluronic Acid (HA) in DI water; 1 mg/mL Gentamicin sulfate). Agitation platform, pH meter, DI water rinse baths.

- Method:

- Surface Activation: Plasma treat sutures (O₂, 100 W, 1 min) to introduce negative charges.

- Cationic Layer Dip: Immerse suture in CHI solution (pH 5.5) for 5 min under gentle agitation. Rinse in two consecutive DI water baths (1 min each).

- Anionic Layer Dip: Immerse suture in HA solution (pH 6.5) for 5 min. Rinse as in step 2.

- Drug Layer Integration: For antibiotic loading, substitute the HA dip with a Gentamicin solution dip (5 min).

- Cycle Repetition: Repeat steps 2-4 to build the desired number of bilayers (e.g., 10x (CHI/HA) + 5x (CHI/Gentamicin)).

- Final Rinse & Dry: Rinse thoroughly and dry under a stream of nitrogen. Cure at 37°C for 2 hours.

Pathway Diagram:

Title: Mechanism of Antimicrobial Coating Action on Bacteria

Application Note: Sensor Integration for pH Monitoring

Objective: To integrate a colorimetric pH sensor into a suture for real-time, visual monitoring of wound infection (acidic pH shift).

Key Quantitative Data: Table 3: Performance Metrics of Integrated pH Sensors

| Sensor Type | Indicator Dye | Immobilization Matrix | Dynamic Range (pH) | Response Time | Color Shift (Acidic→Basic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorimetric | Bromothymol Blue | Agarose/Chitosan Hydrogel | 5.0 - 9.0 | < 2 minutes | Yellow → Blue |

| Colorimetric | Phenol Red | Polyacrylamide Microparticles | 6.8 - 8.2 | ~5 minutes | Yellow → Red |

| Fluorometric | Fluorescein isothiocyanate | Silica Nanoparticles | 4.0 - 8.0 | < 1 minute | Quench → Green Fluorescence |

Protocol: Micro-Encapsulation and Surface Patterning of pH Dye

- Materials: Bromothymol Blue (BTB), Sodium alginate, Calcium chloride solution, 3D printer with micrometer-scale nozzle, PDMS molding substrate.

- Method:

- Sensor Ink Formulation: Prepare 4% w/v sodium alginate in DI water. Add BTB powder to a final concentration of 1% w/w. Mix thoroughly and degas.

- Micro-Deposition: Load ink into a printing syringe fitted with a fine nozzle (≈50 µm). Using a 3D bioprinter, deposit the ink in a discrete, patterned dot (≈200 µm diameter) along the length of a pre-printed suture fixed on a PDMS bed. Maintain 5 mm spacing between sensor dots.

- Crosslinking: Immediately after printing, expose the patterned suture to a CaCl₂ mist (5% w/v) for 60 seconds to ionically crosslink the alginate, trapping the dye.

- Sealing Layer: Dip-coat the entire suture in a thin layer of porous but protective polymer (e.g., 2% w/v PCL in acetone) to secure sensors without inhibiting diffusion.

- Calibration: Immerse sutures in standardized buffer solutions (pH 5, 7, 9) and capture images with a digital microscope. Create a pH vs. RGB value calibration curve.

Integration Diagram:

Title: Multi-Functional 3D-Printed Suture with Integrated Sensor

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Functional Suture Research

| Item/Category | Example Product/Specification | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Biocompatible Polymers | Polycaprolactone (PCL, Mn 80,000), Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA 85:15). | The structural "ink" for 3D printing, providing tunable mechanical properties and degradation profiles. |

| Therapeutic Agents | Doxycycline hyclate, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF-165), Diclofenac sodium. | Active compounds to be loaded for antimicrobial, pro-angiogenic, or anti-inflammatory effects. |

| Crosslinkers | Genipin, N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide (EDC). | To stabilize hydrogels or coatings, controlling drug release kinetics and mechanical stability. |

| Polyelectrolytes for LbL | Chitosan (low MW, >75% deacetylated), Hyaluronic acid (sodium salt, from S. zooepidemicus). | Building blocks for constructing controlled-thickness, multifunctional antimicrobial coatings. |

| Colorimetric Indicators | Bromothymol Blue, Phenol Red. | Dyes for fabricating simple, visually readable sensors to monitor wound pH or other biomarkers. |

| Cell Culture Assays | Live/Dead BacLight Viability Kit, S. aureus (ATCC 25923), L929 Fibroblast cell line. | For in vitro validation of antimicrobial efficacy and cytocompatibility of functionalized sutures. |

| Characterization Tools | Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM), UV-Vis Spectrophotometer, Tensile Tester. | To analyze suture morphology, drug release profiles, and mechanical integrity. |

Solving Print Defects and Enhancing Performance: A Practical Guide for Reliable Suture Fabrication

Application Notes

Within a broader thesis on the 3D printing of surgical sutures, the consistent production of high-fidelity, mechanically reliable filaments is paramount. Three primary artifacts—beading, fractures, and inconsistent diameter—compromise suture integrity, directly affecting tensile strength, knot security, and biocompatibility. These artifacts stem from interdependent process parameters in melt-based extrusion printing (e.g., Fused Deposition Modeling - FDM, or direct melt extrusion of polymers).

Artifact Origins and Impact on Suture Performance

- Beading (or Stringing): Occurs during non-print travel moves when residual polymer oozes from the nozzle, forming unwanted threads or "hairs." In suture printing, this creates surface imperfections that can harbor bacteria, increase drag during tissue passage, and create focal stress points.

- Fractures: Manifest as microscopic cracks or complete layer delamination. They are primarily caused by sub-optimal layer adhesion due to incorrect printing temperature, excessive cooling, or material degradation. For a suture, this leads to catastrophic failure under tensile load.

- Inconsistent Diameter: Variations in the extruded filament diameter along the suture's length. This is a critical failure mode, as suture sizing standards (e.g., USP) are defined by diameter ranges. Inconsistency results from fluctuating nozzle pressure due to unstable temperature, variable feed rate, or partial nozzle clogging.

Recent studies (2023-2024) have quantified the relationship between key printing parameters and these artifacts for common biomedical polymers like Polycaprolactone (PCL), Polylactic Acid (PLA), and Polyglycolic Acid (PGA).

Table 1: Impact of Printing Parameters on Suture Artifacts and Mechanical Properties

| Parameter | Optimal Range (for PCL) | Beading Severity (Scale 1-5) | Fracture Incidence (%) | Diameter Variation (± µm) | Resultant Tensile Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nozzle Temperature | 70-80°C | 1 (Low) | <5% | 15 | 42-48 |

| 90-100°C | 3 (Moderate) | 10% | 25 | 38-45 | |

| 60-65°C | 1 (Low) | 40% (High) | 50 | 20-25 | |

| Print Speed | 5-10 mm/s | 1 (Low) | <5% | 10 | 45-50 |

| 20-30 mm/s | 4 (High) | 15% | 40 | 30-35 | |

| Layer Height | 95% of Nozzle Diam. | 2 (Low-Mod) | <5% | 12 | 44-49 |

| 50% of Nozzle Diam. | 1 (Low) | 25% (High) | 8 | 28-32 | |

| Retraction Distance | 4-6 mm | 1 (Low) | <5% | 15 | 43-48 |

| 0-1 mm | 5 (Very High) | <5% | 20 | 40-46 |

Table 2: Common Polymers for 3D-Printed Sutures and Their Artifact Propensity

| Polymer | Typical Print Temp. | Key Artifact Risk | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | 70-100°C | Fractures (if too cool), Beading (if too hot) | Precise thermal control, enclosed build chamber. |

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | 190-220°C | Brittle Fractures, Hydrolytic Degradation | Thorough drying (<1% humidity), annealing post-print. |

| Polyglycolic Acid (PGA) | 220-250°C | Severe Thermal Degradation & Beading | Minimal residence time in melt zone, nitrogen purge. |

| PCL-PLA Copolymer | 160-180°C | Inconsistent Diameter (phase separation) | Optimized shear rate, uniform pellet size. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Artifact Analysis and Suture Characterization

Title: Quantitative Assessment of 3D-Printed Suture Artifacts and Mechanical Integrity

Objective: To systematically produce, identify, and quantify printing artifacts (beading, fractures, inconsistent diameter) and correlate them with the tensile performance of 3D-printed polymeric sutures.

Materials: (See "Scientist's Toolkit" below).

Methodology:

Printer & Environment Setup:

- Calibrate the melt extrusion 3D printer (e.g., custom or modified bioprinter). Level the build plate.

- Enclose the print area and maintain a constant ambient temperature (25±2°C) to reduce thermal shock.

- Pre-dry polymer filament/pellets in a vacuum oven at 40°C (PCL) or 70°C (PLA) for 12 hours.

Parametric Printing Experiment:

- Design a simple "straight line" G-code script to print 10 cm suture samples.

- Independent Variables: Systematically vary Nozzle Temperature (3 levels), Print Speed (3 levels), and Retraction Distance (2 levels) in a factorial design.

- Constant Parameters: Nozzle diameter = 200 µm, Layer height = 190 µm, Build plate temperature = 30°C (for PCL), Cooling fan = OFF.

Artifact Quantification:

- Diameter Consistency: Using a laser micrometer, measure the diameter at 10 points along each 10 cm sample. Calculate mean diameter and standard deviation.

- Beading Analysis: Image each sample under a digital microscope (50x magnification). Count the number of beads/strings >50 µm in length per cm.

- Fracture Inspection: Perform micro-CT scanning or SEM imaging of a representative 2 cm section from each sample. Qualitatively score fracture density (0= none, 5= severe).

Mechanical Testing:

- Condition all samples at 23°C, 50% RH for 24 hours.

- Using a universal testing machine with a 100 N load cell, perform tensile testing (ASTM D3822). Gauge length: 50 mm. Crosshead speed: 10 mm/min.

- Record ultimate tensile strength (UTS), elongation at break, and Young's modulus.

Data Analysis:

- Perform ANOVA to determine the statistical significance of each printing parameter on artifact metrics and UTS.

- Create correlation matrices linking artifact severity (diameter variation, beading score) to mechanical failure.

Protocol for Mitigating Fractures via In-Line Annealing

Title: In-Line Thermal Annealing Protocol for Enhanced Layer Adhesion

Objective: To implement and test a post-print annealing process that reduces intra-layer fractures in 3D-printed sutures by promoting polymer chain inter-diffusion.

Methodology: