Immunomodulatory Biomaterials: Mastering Host Interactions for Regenerative Medicine and Advanced Drug Delivery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the dynamic interplay between biomaterials and the host immune system, a critical determinant for the success of medical implants, tissue engineering, and drug...

Immunomodulatory Biomaterials: Mastering Host Interactions for Regenerative Medicine and Advanced Drug Delivery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the dynamic interplay between biomaterials and the host immune system, a critical determinant for the success of medical implants, tissue engineering, and drug delivery systems. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational immunology, advanced material design strategies, and state-of-the-art analytical techniques. We explore the evolution from bioinert to bioactive and smart immunomodulatory materials, detailing how physical, chemical, and biological properties can be engineered to steer immune responses toward pro-regenerative outcomes. The content further addresses critical challenges in biocompatibility and clinical translation, evaluates current in vitro and in vivo validation methodologies, and compares the performance of natural and synthetic biomaterials. This resource aims to equip experts with the knowledge to design next-generation biomaterials that proactively harness the immune system for improved therapeutic efficacy.

The Immune System Meets Biomaterials: Decoding the Foreign Body Response and Foundational Interactions

The Foreign Body Response: A Sequential Biological Process

The implantation of a biomaterial initiates a complex and sequential host reaction known as the Foreign Body Response (FBR). This process begins with surgical injury and can culminate in the isolation of the implant within a dense fibrous capsule, which often compromises the device's functionality [1] [2]. The FBR is an inevitable host reaction marked by a cascade of inflammatory and fibrotic processes, governed by a dynamic network of molecular signaling pathways, cellular mechanosensing, and intercellular communication [1].

The sequence of events unfolds as follows:

- Surgical Injury and Acute Inflammation: Implantation causes local tissue damage and rupture of blood vessels, leading to blood-material interactions and the formation of a provisional matrix containing fibrin and inflammatory mediators. This matrix facilitates the recruitment of innate immune cells, primarily neutrophils, which characterize the initial acute inflammatory phase [2].

- Chronic Inflammation and Monocyte/Macrophage Involvement: If the acute inflammation does not resolve, or due to the persistent presence of the foreign material, the response transitions to a chronic phase. This stage is dominated by monocytes and macrophages. Macrophages attempt to phagocytose the material, and upon failing, may fuse to form foreign body giant cells (FBGCs) on the implant surface [2].

- Fibrosis and Encapsulation: The prolonged inflammatory milieu stimulates the activation and proliferation of fibroblasts. These cells deposit dense layers of collagen and extracellular matrix, forming a avascular fibrous capsule that walls off the implant from the surrounding tissue [1] [2]. This encapsulation can lead to functional failure of devices such as sensors, drug-delivery systems, and implants [3].

Table 1: Key Cellular Players in the Foreign Body Response.

| Cell Type | Role in FBR | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|

| Neutrophils | First responders; initiate acute inflammation; release reactive oxygen species (ROS) and enzymes. | Cytokines, proteases, DAMPs. |

| Macrophages | Central regulators of inflammation and fibrosis; attempt phagocytosis; form FBGCs. | Pro-inflammatory (TNF-α, IL-6) & pro-fibrotic cytokines; growth factors. |

| Fibroblasts | Effector cells of fibrosis; produce and remodel extracellular matrix (ECM). | Collagen, fibronectin; fibrous capsule. |

| Foreign Body Giant Cells (FBGCs) | Formed from macrophage fusion; persist on material surface. | Sustained inflammatory signals; enzymes. |

Quantitative Analysis of FBR Severity and Biomaterial Performance

The severity of the FBR and the performance of novel biomaterials are quantified using specific histological, molecular, and functional metrics. These parameters allow for the direct comparison between different materials and the evaluation of new anti-FBR strategies.

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Assessing the Foreign Body Response In Vivo.

| Assessment Method | Quantitative Parameters | Interpretation and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Histological Staining (e.g., H&E, Masson's Trichrome) | Fibrous capsule thickness (μm); Cellular density and composition. | Thinner capsule indicates better biocompatibility; identifies inflammatory cell infiltration. |

| Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Expression levels of markers (e.g., CCR-7, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10). | Quantifies pro- vs. anti-inflammatory responses at the implant-tissue interface. |

| Proteome Profiler Antibody Array | Relative concentration of multiple cytokines/chemokines from peri-implant tissue. | Provides a systemic view of the immune and inflammatory status. |

| Functional Device Testing | Device longevity (days); Signal fidelity; Drug delivery efficacy. | Measures the ultimate clinical impact of the FBR on implant performance. |

Recent research on a novel immunocompatible elastomer platform, termed EVADE, provides a benchmark for high-performance, anti-fibrotic materials. In a subcutaneous implantation model in C57BL/6 mice, EVADE (H90 formulation) demonstrated a significantly reduced fibrotic capsule thickness of 10–40 μm after one month, compared to 45–135 μm for medical-grade PDMS controls [3]. This superior performance was maintained long-term, with negligible inflammation and capsule formation observed after one year in mice and two months in non-human primate models [3]. Proteomic analysis revealed that EVADE implants significantly reduced the expression of the pro-inflammatory alarmins S100A8/A9 at the implant site, suggesting a key molecular target for mitigating fibrosis [3].

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Subcutaneous Implantation and FBR Evaluation

This protocol details a standard methodology for evaluating the host response to biomaterials in a rodent subcutaneous implantation model, synthesizing established practices from the field [2] [3].

Materials and Pre-implantation Preparation

- Biomaterials: Fabricate test materials (e.g., polymer discs of EVADE, PDMS) to standardized dimensions (e.g., 5 mm diameter, 1 mm thickness). Adjust material modulus to be comparable between groups if necessary [3].

- Animals: C57BL/6 mice (or other appropriate strain), 8-12 weeks old.

- Sterilization: Sterilize all materials and surgical instruments using ethylene oxide gas or autoclaving (where material properties allow).

- Anesthesia: Prepare a ketamine/xylazine mixture (e.g., 100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine) for intraperitoneal injection.

Surgical Implantation Procedure

- Anesthetize the mouse and confirm the depth of anesthesia by the absence of a pedal reflex.

- Shave the dorsal fur and disinfect the surgical site with alternating scrubs of betadine and 70% ethanol.

- Using aseptic technique, make a single midline incision of approximately 1 cm in the dorsal skin.

- Create subcutaneous pockets by blunt dissection laterally from the incision. Each mouse can accommodate multiple implants (e.g., one per quadrant), with each pocket sized to fit the implant without excessive tension.

- Insert one sterile material disc into each subcutaneous pocket. Include sham-operated controls (incision without implant) if required by the experimental design.

- Close the incision with surgical wound clips or sutures.

- Monitor the animals until fully recovered from anesthesia and provide post-operative analgesia as approved by the institutional animal care and use committee.

Post-implantation Analysis and Tissue Harvest

- Duration: Plan endpoints based on the biological phase of interest: acute inflammation (e.g., 3-7 days), chronic inflammation and early fibrosis (e.g., 2-4 weeks), or long-term encapsulation (e.g., 1-3 months, or longer) [3].

- Euthanasia and Harvest: At the designated time point, euthanize animals according to approved protocols. Carefully excise the implant with the surrounding tissue envelope intact.

- Sample Processing:

- For histology: Fix the entire tissue-implant construct in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24-48 hours. After fixation, carefully remove the implant to avoid damaging the tissue cavity before processing the tissue for paraffin embedding. Section tissues to 5 μm thickness.

- For protein/mRNA analysis: Dissect the tissue adjacent to the implant (a defined peri-implant area) and snap-freeze in liquid nitrogen. Store at -80°C until analysis.

Key Outcome Measures and Analytical Techniques

- Histological Evaluation: Stain sections with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) for general morphology and cellular infiltration, and Masson's Trichrome for collagen deposition and fibrous capsule visualization [3]. Quantify fibrous capsule thickness from multiple, standardized locations around the implant using image analysis software.

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): Perform IHC for specific cell markers (e.g., CCR-7 for M1 macrophages, CD206 for M2 macrophages) and inflammatory mediators (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6, S100A8/A9) [3]. Use semi-quantitative or quantitative (e.g., image analysis) scoring systems.

- Protein-Level Analysis: Use Proteome Profiler Antibody Arrays to simultaneously measure the relative levels of multiple cytokines and chemokines from homogenized peri-implant tissue lysates, following the manufacturer's protocol [3].

Molecular Signaling in the Foreign Body Response

The progression of the FBR is directed by a complex interplay of molecular signals. Key pathways involve the initial recruitment of immune cells via cytokines and chemokines, the activation of macrophages into pro-inflammatory (M1) or pro-healing (M2) phenotypes, and the subsequent activation of fibroblasts leading to fibrosis [1] [2]. Recent mechanistic studies highlight the role of specific proteins, such as the S100A8/A9 heterodimer, as critical alarmins that drive the inflammatory and fibrotic cascade. Inhibition or knockout of S100A8/A9 has been shown to substantially attenuate fibrosis in mouse models, identifying it as a promising therapeutic target [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials for FBR Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Foreign Body Response Studies.

| Reagent / Material | Function and Application in FBR Research |

|---|---|

| EVADE Elastomers | A novel platform of immunocompatible elastomers (e.g., H90) used as a test material demonstrating long-term suppression of inflammation and capsule formation in vivo [3]. |

| Medical-Grade PDMS | A widely used reference/control elastomer known to elicit a standard FBR, enabling comparative assessment of new materials [3]. |

| Proteome Profiler Antibody Arrays | Membrane-based arrays used to simultaneously detect and semi-quantify multiple inflammation-related cytokines and chemokines from tissue lysates surrounding the implant [3]. |

| S100A8/A9 Inhibitors | Specific antibodies or pharmacological agents used to block the function of the S100A8/A9 alarmin complex, allowing for mechanistic studies of fibrosis [3]. |

| Cytokine-specific Antibodies | Essential reagents for immunohistochemistry (IHC) and ELISA to localize and quantify key inflammatory markers (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6, CCR-7, IL-10) in tissue sections [3]. |

| Masson's Trichrome Stain | A standard three-color staining protocol used on paraffin-embedded tissue sections to distinguish collagen (blue/green) from muscle (red) and cell nuclei (black), critical for quantifying fibrous capsule formation [3]. |

This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of the central roles played by macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells, and lymphocytes in the context of biomaterial host interactions and immune responses. The successful integration of biomaterials and the subsequent tissue regeneration process are fundamentally governed by a carefully orchestrated immune response. Understanding these cellular mechanisms is paramount for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to design next-generation immunomodulatory biomaterials and therapeutic strategies. This whitepaper synthesizes current research to detail the specific functions, signaling pathways, and experimental approaches relevant to characterizing these key immune players, with a particular emphasis on their temporal coordination following biomaterial implantation.

Macrophages: The Orchestrators of Immune Response and Tissue Repair

M1/M2 Polarization and Functional Phenotypes

Macrophages are versatile innate immune cells essential for maintaining tissue homeostasis, providing host defense, and orchestrating tissue repair. They exhibit remarkable phenotypic plasticity, dynamically polarizing in response to local microenvironmental cues [4]. The classical framework describes polarization into two main phenotypes: the pro-inflammatory M1 and the anti-inflammatory or pro-regenerative M2 macrophages [5] [6].

M1 Macrophages (Classical Activation): Induced by microbial components like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and Th1 cytokines such as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), M1 macrophages drive pro-inflammatory responses [5] [4]. Key signaling pathways involve JAK-STAT1 activation downstream of the IFN-γ receptor, and MyD88/TRIF signaling downstream of TLR4 engagement, leading to the activation of transcription factors like NF-κB and IRF3 [4]. This results in the high production of inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6, IL-12), generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, and strong antimicrobial activity [5] [6]. They are characterized by surface markers like CD80, CD86, and high expression of MHC class II molecules [6].

M2 Macrophages (Alternative Activation): Polarized by Th2 cytokines including IL-4 and IL-13, M2 macrophages are associated with immune regulation, wound healing, and tissue regeneration [5] [4]. The IL-4Rα receptor signaling activates JAK-STAT6, along with transcription factors IRF4 and PPARγ [4]. This phenotype upregulates surface markers like the mannose receptor (CD206) and CD163, and produces anti-inflammatory factors (e.g., IL-10, TGF-β) and enzymes like Arginase-1 (Arg-1) which promote matrix deposition and repair [5] [6]. The M2 phenotype can be further subdivided into M2a, M2b, M2c, and M2d based on specific inducers and functions, with M2a being primarily linked to anti-inflammatory responses and bone regeneration [5].

caption: Table 1: Key Characteristics of M1 and M2 Macrophage Polarization

| Feature | M1 (Pro-inflammatory) | M2 (Anti-inflammatory/Pro-regenerative) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Inducers | LPS, IFN-γ, GM-CSF [5] [4] | IL-4, IL-13, IL-10, Glucocorticoids [5] [4] |

| Key Signaling Pathways | TLR/MyD88/TRIF, JAK-STAT1, NF-κB, IRF3 [4] | IL-4R/JAK-STAT6, IRF4, PPARγ [4] |

| Characteristic Markers | CD80, CD86, MHC-II, iNOS [5] [6] | CD206, CD163, Arg-1, FIZZ1 [5] [6] |

| Major Secretory Products | TNF-α, IL-6, IL-12, IL-1β, ROS/NOS [5] [4] | IL-10, TGF-β, CCL17, CCL22, VEGF [5] [6] |

| Primary Functions | Pathogen clearance, pro-inflammatory response, antimicrobial activity [6] | Tissue repair, angiogenesis, immune regulation, matrix remodeling [5] |

The Role of Macrophages in Biomaterial Integration and Bone Regeneration

The temporal sequence of macrophage polarization is critical for successful biomaterial integration and bone regeneration. Following injury or implantation, an initial M1-dominated response is beneficial for pathogen clearance and initiation of the healing process [5]. Subsequently, a timely transition to an M2-dominated phenotype facilitates tissue repair, angiogenesis, and osteogenesis [5]. Biomaterials can be engineered with specific physical and chemical properties to actively guide this polarization. Key biomaterial properties that influence macrophage behavior include:

- Stiffness: Substrate elasticity can direct macrophage polarization [5].

- Topography and Pore Architecture: Surface geometry and scaffold microstructure provide physical cues [5].

- Hydrophilicity and Chemical Composition: Surface chemistry and the release of bioactive ions (e.g., from metals) can modulate the immune response [5] [7].

An imbalance, such as a prolonged M1 response or premature M2 polarization, can lead to chronic inflammation, fibrous encapsulation of the implant, or failed integration [5]. Therefore, designing biomaterials that encourage a dynamic shift from M1 to M2 is a key strategy in bone tissue engineering [5] [7].

Neutrophils: The First Responders

Recruitment and Core Antibacterial Functions

Neutrophils are the most abundant leukocytes in human blood and are the first immune cells recruited to sites of injury, infection, or biomaterial implantation [8] [9]. Their recruitment involves a well-defined sequence of steps: rolling, adhesion, crawling, and transmigration out of blood vessels, guided by chemokine gradients like IL-8 [8]. Upon arrival, they deploy several potent mechanisms to eliminate pathogens and clear debris [8]:

- Phagocytosis: Direct engulfment and destruction of bacteria within phagolysosomes using oxidative (e.g., Hypochlorous acid generated via Myeloperoxidase (MPO)) and non-oxidative (e.g., lysozyme, defensins) mechanisms [8].

- Degranulation: Release of pre-formed antimicrobial proteins and enzymes from cytoplasmic granules into the extracellular space [8].

- Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs): A unique cell death process (NETosis) where neutrophils extrude a web of DNA decorated with histones and granule proteins (e.g., NE, MPO) to trap and neutralize pathogens [8]. NETs can be formed via NADPH oxidase (NOX)-dependent or NOX-independent pathways [8].

- Oxidative Burst: Rapid production of large quantities of reactive oxygen species (ROS) via the NADPH oxidase complex for microbial killing [8].

Neutrophils as Instructive Cells for Tissue Repair

Beyond their antibacterial role, neutrophils are critical instructors of the subsequent immune response to biomaterials. They secrete cytokines and chemokines that recruit and influence the polarization of other immune cells, particularly monocytes and macrophages [10] [9]. Their lifespan and mode of death are crucial for determining the healing outcome. Apoptotic neutrophil death followed by efferocytosis (clearance by macrophages) is a key signal that prompts macrophages to switch from a pro-inflammatory M1 to a pro-healing M2 phenotype, thereby resolving inflammation [9]. Conversely, persistent neutrophil activation or excessive NETosis can lead to chronic inflammation, tissue damage, and fibrous encapsulation of biomaterials, preventing integration [8] [9]. Recent studies show that neutrophil response is influenced by biomaterial properties such as polymer origin (natural vs. synthetic), stiffness, and surface charge [10].

Dendritic Cells: Bridging Innate and Adaptive Immunity

Subsets, Development, and Core Functions

Dendritic cells (DCs) are professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that form a critical bridge between the innate and adaptive immune systems [11]. They originate from bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells under the regulation of cytokines like Flt3L and key transcription factors (e.g., IRF8, PU.1) [11]. The main DC subsets include:

- Classical DCs (cDC1 and cDC2): Specialized in antigen capture and presentation. cDC1s are critical for cross-presenting antigens to CD8+ T cells, while cDC2s primarily activate CD4+ T cells [11].

- Plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs): Specialized in secreting vast amounts of Type I Interferons (IFN-α/β) in response to viral infections [11].

- Monocyte-derived DCs (moDCs): Differentiated from monocytes during inflammation [11].

- Langerhans Cells: Tissue-resident DCs in the epidermis [11].

The core functions of DCs involve antigen capture in peripheral tissues, followed by migration to secondary lymphoid organs. During migration, they undergo maturation, upregulating MHC and co-stimulatory molecules (CD80, CD86). In the lymph nodes, they present processed antigens to naïve T cells, thereby activating and polarizing antigen-specific T cell responses (e.g., Th1, Th2, Th17) [11]. DCs are also indispensable for inducing immune tolerance to self-antigens [11].

DCs in Biomaterial and Therapeutic Contexts

In the context of biomaterials, DCs can be targeted to steer immune responses toward either tolerance (for implant acceptance) or immunity (for vaccine development). DC-based therapies, such as cancer vaccines, have been explored, with the first FDA-approved DC vaccine (Sipuleucel-T) for prostate cancer [11] [12]. Biomaterial scaffolds are being used to enhance DC-based therapies by providing a 3D environment for cell delivery, controlling the release of antigens and adjuvants, and recruiting host DCs to the implantation site [12].

Lymphocytes: The Adaptive Immune Specificity

Lymphocytes, including T cells and B cells, provide antigen-specific, long-lasting adaptive immunity. Their role in the response to biomaterials is complex and shaped by the initial innate immune response.

- T Cells: Activated by DCs, T cells can exert both beneficial and detrimental effects on tissue regeneration. Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells can clear infected cells, while CD4+ Helper T cells (e.g., Th1, Th2) release cytokines that can influence macrophage polarization and osteoblast/osteoclast activity [5]. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are crucial for suppressing excessive inflammation and promoting tolerance [7]. The success of Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T cell therapies in oncology highlights the potential of engineered lymphocyte therapies [12].

- B Cells: Primarily responsible for producing antigen-specific antibodies. Their role in the direct response to biomaterials is less characterized but contributes to the overall humoral immune response.

The interaction between biomaterials and lymphocytes is often indirect, mediated by innate immune cells like DCs and macrophages. An uncontrolled adaptive response can lead to implant rejection, while a regulated response can support healing.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: In Vitro Assessment of Macrophage Polarization

Objective: To evaluate the immunomodulatory effect of a biomaterial surface on macrophage polarization.

Materials:

- Cells: Primary human or murine monocytes (e.g., from bone marrow or peripheral blood) or a macrophage cell line (e.g., RAW 264.7).

- Culture Reagents: Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor (M-CSF) for differentiation, polarization cytokines (e.g., LPS + IFN-γ for M1; IL-4 for M2), cell culture media.

- Test Material: Biomaterial scaffolds or flat substrates placed in culture wells.

- Analysis Tools: Antibodies for flow cytometry (anti-CD80, CD86, CD206, MHC-II), ELISA kits for cytokines (TNF-α, IL-12, IL-10, TGF-β), reagents for RNA extraction and qPCR (for iNOS, Arg-1, etc.).

Methodology:

- Monocyte Isolation and Differentiation: Isolate monocytes and seed them onto the test biomaterial and control surfaces (e.g., tissue culture plastic). Differentiate monocytes into naïve (M0) macrophages using M-CSF (50 ng/mL) for 5-7 days [5].

- Polarization Stimulation: Stimulate the differentiated macrophages with M1 polarizing agents (e.g., 100 ng/mL LPS + 20 ng/mL IFN-γ) or M2 polarizing agents (e.g., 20 ng/mL IL-4) for 24-48 hours. A material-only group without polarizing cytokines is essential to assess the material's intrinsic effect.

- Cell Harvest and Analysis:

- Flow Cytometry: Harvest cells and stain for M1 (CD80, CD86) and M2 (CD206) surface markers. Analyze using a flow cytometer to determine the percentage of positively stained cells [6].

- Gene Expression Analysis (qRT-PCR): Lyse cells to extract RNA. Perform reverse transcription and qPCR for M1-associated genes (iNOS, IL-12) and M2-associated genes (Arg-1, Ym1). Normalize data to a housekeeping gene (e.g., GAPDH) and use the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method for analysis [5].

- Cytokine Secretion (ELISA): Collect cell culture supernatants. Use specific ELISA kits to quantify the secretion of M1 (TNF-α, IL-12) and M2 (IL-10) cytokines according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Protocol 2: In Vitro Functional Profiling of Neutrophil Response to Biomaterials

Objective: To characterize key neutrophil functions (activation, NETosis, phagocytosis) when cultured on different biomaterials.

Materials:

- Cells: Freshly isolated human neutrophils from peripheral blood.

- Culture Reagents: Histopaque density gradient media, HBSS buffer, fluorescent probes (e.g., SYTOX Green for extracellular DNA, CM-H2DCFDA for ROS).

- Test Material: Biopolymer substrates of varying composition and stiffness.

- Analysis Tools: Fluorescent microscope, plate reader, MPO activity assay kit.

Methodology:

- Neutrophil Isolation: Isolate neutrophils from fresh human blood using density gradient centrifugation (e.g., with Histopaque) [10].

- Culture on Biomaterials: Seed purified neutrophils onto the test biomaterials and control surfaces. Culture for a defined period (e.g., 4-6 hours).

- Functional Assays:

- NETosis Assay: Stain cultures with a cell-impermeable DNA dye (e.g., SYTOX Green). Quantify fluorescence, which indicates extracellular DNA release, using a plate reader or image the fibrous NET structures using fluorescence microscopy [8] [10].

- Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Production: Load cells with a ROS-sensitive fluorescent dye (e.g., CM-H2DCFDA) before seeding. Measure fluorescence intensity over time as an indicator of oxidative burst [8] [10].

- Phagocytosis Assay: Incubate neutrophils with fluorescently labeled particles (e.g., pHrodo E. coli bioparticles). Measure internalized fluorescence after quenching extracellular signal [8].

- Cell Survival/Death Assay: Use a viability dye (e.g., Propidium Iodide) and an apoptosis marker (e.g., Annexin V) to distinguish between apoptotic and necrotic neutrophils via flow cytometry [10].

caption: Table 2: Key Parameters for Profiling Neutrophil-Biomaterial Interactions In Vitro

| Parameter Measured | Experimental Assay | Key Reagents/Tools | Interpretation of Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| NET Formation | Fluorescence-based NETosis assay [8] [10] | SYTOX Green, Anti-citrullinated Histone H3 (CitH3) Antibody | High fluorescence/extensive fibrous structures indicate strong neutrophil activation and NET release. |

| ROS Production | Oxidative burst assay [8] [10] | CM-H2DCFDA, Dihydrorhodamine 123 | Increased fluorescence intensity indicates elevated ROS generation, a key bactericidal mechanism. |

| Cell Viability & Death Mode | Annexin V/PI staining & flow cytometry [10] | Annexin V-FITC, Propidium Iodide (PI) | High Annexin V+/PI- (apoptosis) is desirable for resolution; High PI+ (necrosis) can promote inflammation. |

| Cytokine/Chemokine Release | Multiplex ELISA of culture supernatant [10] | Multiplex cytokine array (e.g., for IL-8, TNF-α) | Identifies the secretory profile, indicating the pro-inflammatory or regulatory role of neutrophils. |

| Phagocytic Capacity | Phagocytosis of fluorescent bioparticles [8] | pHrodo Green E. coli BioParticles | A decrease in fluorescence over time (after quenching) indicates efficient particle internalization. |

Signaling Pathways and Cellular Crosstalk

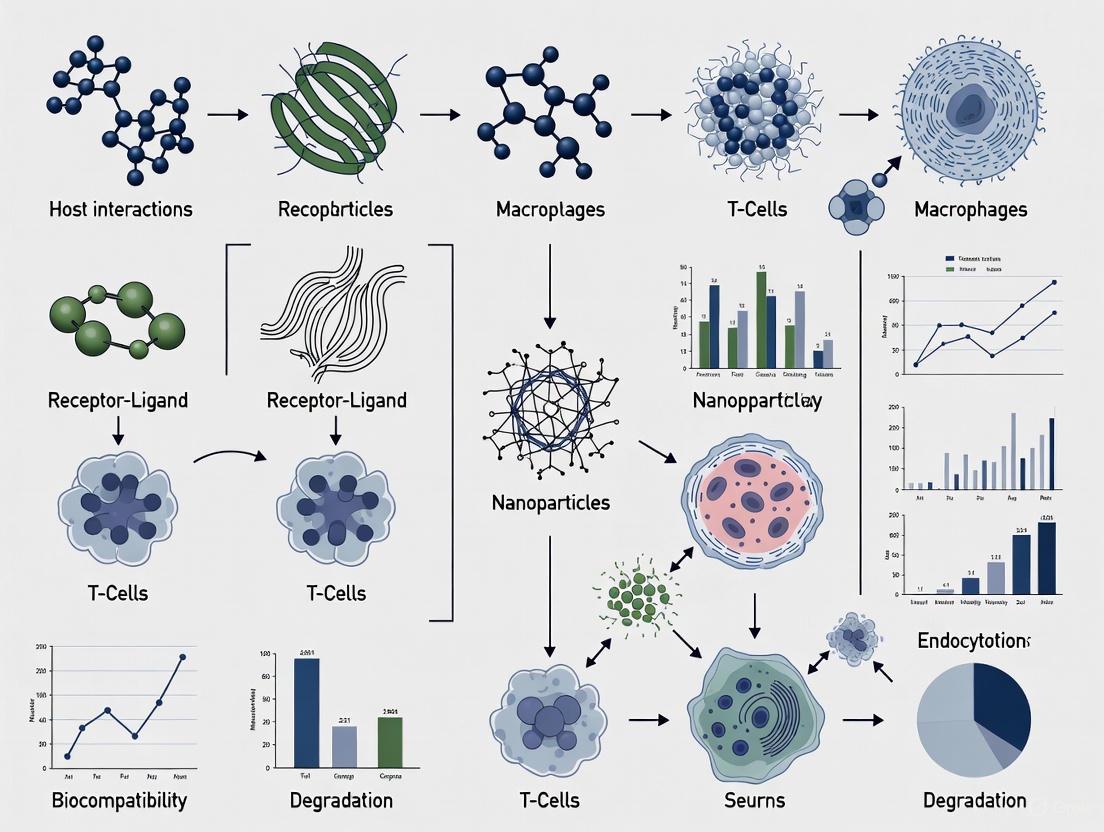

The following diagrams illustrate the core signaling pathways and the sequential crosstalk between immune cells in response to biomaterials.

caption: Figure 1: Signaling pathways driving macrophage M1 and M2 polarization.

caption: Figure 2: Sequential crosstalk and orchestration between key immune cells following biomaterial implantation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

caption: Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Immune Cell Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Cytokines (e.g., M-CSF, IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-13) | Direct polarization and differentiation of immune cells in vitro. | Differentiating monocytes to macrophages (M-CSF); polarizing macrophages to M1 (IFN-γ + LPS) or M2 (IL-4) [5] [4]. |

| Fluorescent Conjugated Antibodies (for Flow Cytometry) | Identification and phenotyping of cell populations via surface and intracellular markers. | Staining for M1 markers (CD80, CD86) and M2 markers (CD206) on macrophages; identifying DC subsets (CD11c, CD141, CD1c) [5] [11]. |

| ELISA Kits | Quantification of specific protein secretion (cytokines, chemokines) in cell culture supernatants. | Measuring TNF-α or IL-12 (M1) and IL-10 or TGF-β (M2) to assess macrophage polarization [5]. |

| SYTOX Green / Anti-CitH3 Antibody | Detection and quantification of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs). | Staining extracellular DNA and citrullinated histones to visualize and quantify NETosis in response to biomaterials [8]. |

| Flt3 Ligand (Flt3L) | Expansion and differentiation of classical DC (cDC) precursors in vitro and in vivo. | Generating large numbers of DCs from bone marrow cultures for functional studies or therapeutic applications [11]. |

| pHrodo BioParticles | Measurement of phagocytic activity. | Neutrophils or macrophages ingest these particles, which fluoresce brightly in the acidic phagolysosome, allowing phagocytosis quantification [8]. |

The interaction between biomaterials and the biological environment is a critical determinant of their success or failure in medical applications. Upon implantation or injection, the surface of any biomaterial is immediately coated by a dynamic layer of adsorbed biomolecules, predominantly proteins, forming what is known as the "protein corona" [13] [14]. This corona represents the primary interface between the synthetic material and the host's biological systems, effectively creating a new biological identity that overwrites the material's original synthetic properties [15] [13]. The composition and behavior of this protein layer fundamentally dictate subsequent immune recognition, inflammatory responses, and ultimately, therapeutic efficacy [16] [15].

The formation of the protein corona is not a passive process but rather a dynamic exchange of biomolecules that evolves as the material transitions through different biological compartments [13]. This review synthesizes current understanding of how the protein corona mediates immune recognition, with particular emphasis on the physicochemical determinants of corona composition, subsequent immune signaling pathways activated, and advanced computational approaches for predicting these interactions. Within the broader context of biomaterial-host interactions, understanding and controlling corona formation represents a paradigm shift from designing bioinert materials to actively engineering bioactive interfaces that direct favorable immune responses [16].

The Fundamental Nature of the Protein Corona

Structural Organization and Dynamics

The protein corona is structurally organized into two distinct layers with different stability and exchange kinetics. The hard corona consists of proteins with high binding affinity that are directly adsorbed to the nanoparticle surface through electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions [13]. This layer remains stable for extended periods and maintains its integrity even in dynamic biological environments. Surrounding this core is the soft corona, comprising proteins with weaker binding affinity that undergo continuous exchange with the surrounding biological milieu [13]. This dynamic outer layer fluctuates rapidly in response to changes in the biological environment, making its characterization methodologically challenging.

The corona formation follows a temporal evolution where small, highly mobile proteins like albumin initially adsorb to the surface but are gradually displaced by proteins with higher binding affinities—a phenomenon known as the Vroman effect [13]. This process reaches equilibrium typically within 30-60 minutes for many nanomaterial systems, though the exact kinetics depend on material properties and biological conditions [13].

Key Factors Influencing Corona Composition

Multiple factors determine the precise composition of the protein corona, creating a complex "personalized" profile that varies based on both material properties and biological context [15].

Table 1: Factors Influencing Protein Corona Composition

| Factor Category | Specific Parameters | Impact on Corona Composition |

|---|---|---|

| Nanoparticle Properties | Size, Shape, Surface chemistry, Hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity, Surface charge (ζ-potential), Material composition | Smaller particles have higher curvature affecting protein binding; hydrophobic surfaces promote more protein unfolding; surface charge determines electrostatic interactions |

| Biological Environment | Protein source (species), Protein concentration, Biological fluid composition (plasma, BALF, etc.), Disease state, Temperature, pH | Disease states alter plasma composition; protein concentration affects binding kinetics; different biological fluids contain distinct protein profiles |

| Temporal Factors | Incubation time, Administration route, Temporal disease progression | Corona evolves over time through Vroman effect; disease progression dynamically alters available proteins |

The physicochemical properties of the nanoparticle surface profoundly influence corona formation. Surface hydrophobicity drives protein adsorption through hydrophobic interactions, often resulting in protein unfolding and denaturation [13]. Hydrophobic nanoparticles typically adsorb approximately twice as much protein as hydrophilic counterparts and form more stable coronas with reduced dynamic exchange [13]. Surface charge, represented by ζ-potential, determines electrostatic interactions with charged protein domains, with highly positive or negative surfaces attracting oppositely charged proteins [17].

The biological context introduces significant variability in corona composition. Recent research demonstrates that disease states dynamically alter plasma biomolecule profiles, which in turn dramatically affects corona composition and subsequent immune responses [15]. For instance, in murine models of LPS-induced endotoxemia, the corona formed at different time points post-inflammatory challenge (3hr vs 8hr) exhibited distinct protein fingerprints and elicited dramatically different macrophage responses [15].

Quantitative Analysis of Corona-Mediated Immune Responses

Immune Cell Responses to Corona-Coated Materials

The protein corona directly influences immune recognition by presenting specific surface epitopes and ligands to immune cells. The table below summarizes key findings from recent studies investigating immune responses to protein corona-coated biomaterials.

Table 2: Immune Cell Responses to Corona-Coated Biomaterials

| Immune Cell Type | Material | Key Corona-Mediated Effects | Experimental Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macrophages | Titanium with hydrophilic surface | ↓ Pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF); ↑ Anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-4, IL-10); ↑ M2 phenotype | In vitro (C57BL/6J mice) [16] |

| Macrophages | PLGA NPs with inflammatory plasma corona | ↑ Co-stimulatory molecules (CD80: 1.43-fold, CD86: 2.30-fold); ↑ PD-L1 (14.61-fold); ↑ Pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNFα, IL-6, CXCL1) | In vitro (bone marrow-derived macrophages) [15] |

| Macrophages | Nanoengineered surfaces (70 nm topography) | Reduced inflammatory response; Alterations in adsorbed protein composition (↓ clusterin, ↑ ApoB and IgG gamma) | In vitro (macrophages) [18] |

| Neutrophils | Hydrophilic Titanium | ↓ Cytokine release; ↓ NET formation | In vitro (C57BL/6J mice) [16] |

| Neutrophils | Hydrophobic PTFE | ↑ NET formation; ↑ ROS generation; ↑ Histone citrullination | In vitro (Human PBMC) [16] |

Key Corona Proteins and Their Immune Implications

Machine learning analysis of extensive protein corona databases has identified specific proteins whose adsorption consistently correlates with distinct immune responses and biodistribution patterns.

Table 3: Key Corona Proteins and Their Immunological Significance

| Protein | Immune/Biological Function | Impact on Nanoparticle Fate |

|---|---|---|

| Apolipoprotein E (APOE) | Lipoprotein mediating cellular uptake via LDL receptor pathways | Enhances targeting to brain and liver; associated with receptor-mediated uptake [17] |

| Apolipoprotein B-100 (APOB-100) | Principal lipoprotein in LDL particles | Promotes liver targeting via LDL receptor pathways [17] |

| Complement C3 (C3) | Central component of complement system | Opsonization; promotes immune recognition and clearance; enhances uptake by monocytes [17] |

| Clusterin (CLUS/ApoJ) | Dysopsonin, chaperone protein | Reduces nonspecific cell uptake; may impart "stealth" properties [17] |

| Immunoglobulins (IgG) | Antibody-mediated opsonization | Enhances phagocytic clearance via Fc receptor recognition [18] |

| Albumin | Most abundant serum protein | Can impart stealth properties at high coverage; initial corona component [13] |

Meta-analysis of 817 nanoparticle formulations revealed that silica, polystyrene, and lipid-based nanoparticles smaller than 100 nm with moderately negative to neutral ζ-potentials preferentially bind APOE and APOB-100, which are linked to receptor-mediated uptake and enhanced delivery efficiency [17]. In contrast, metal and metal-oxide nanoparticles with highly negative surface charge enrich complement component C3, indicating greater likelihood of immune recognition and clearance [17].

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The protein corona influences immune responses through specific receptor-mediated signaling pathways. Integrated multi-omics approaches have identified Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling as a central pathway activated by specific corona compositions.

Diagram 1: TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB Signaling Pathway in Corona-Mediated Immune Activation

Pharmacological inhibition and genetic knockout studies have validated that specific nanoparticle coronas mediate immune activation through the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling axis [15]. Coronas enriched with damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) or pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) from inflammatory environments can directly activate pattern recognition receptors on immune cells, initiating a cascade that leads to NF-κB translocation and pro-inflammatory gene expression.

The diagram illustrates how corona components (such as LPS or LPS-binding proteins enriched in inflammatory conditions) engage TLR4 receptors, triggering downstream signaling through the MyD88 adaptor protein, resulting in IKK complex activation, NF-κB nuclear translocation, and ultimately production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and immune activation.

Experimental Methodologies for Corona Research

Standard Protocol for Protein Corona Isolation and Characterization

The following workflow represents a standardized approach for protein corona isolation and characterization, synthesized from multiple methodological approaches [15] [13] [18].

Diagram 2: Protein Corona Isolation and Characterization Workflow

Step 1: Nanoparticle Formulation and Characterization

- Synthesize nanoparticles with defined physicochemical properties (size, charge, hydrophobicity)

- Common systems include PLGA, titanium, silica, and lipid-based nanoparticles [15] [17]

- Characterize baseline properties using DLS (size, PDI), ζ-potential measurements (surface charge), and TEM (morphology) [13]

Step 2: Biological Fluid Incubation

- Incubate nanoparticles with relevant biological fluid (human plasma, serum, BALF)

- Standard conditions: 37°C with gentle agitation for 30-60 minutes [13]

- Protein concentration typically 50-100% of physiological concentration [17]

- Consider disease-specific biofluids for personalized corona profiling [15]

Step 3: Corona Isolation

- Separate corona-coated nanoparticles from unbound proteins via centrifugation

- Alternative methods: magnetic separation, size-exclusion chromatography [13]

- Centrifugation parameters: typically 14,000-20,000 × g for 15-30 minutes [15]

Step 4: Washing and Corona Stabilization

- Carefully wash pellet with mild buffer (e.g., PBS) to remove loosely associated proteins

- Repeat centrifugation 2-3 times to isolate hard corona [13]

- Note: Washing may remove components of the soft corona [13]

Step 5: Corona Characterization

- SDS-PAGE: Qualitative protein fingerprinting [15]

- LC-MS/MS: Quantitative proteomic analysis [17]

- DLS: Hydrodynamic size and aggregation state [15]

- Additional techniques: ITC, FTIR, circular dichroism for structural information [13] [14]

Step 6: Biological Response Assessment

- Incubate corona-coated nanoparticles with immune cells (e.g., macrophages)

- Assess cellular association/uptake via flow cytometry [15]

- Measure cytokine secretion via multiplex ELISA [15]

- Evaluate surface marker expression (CD80, CD86, PD-L1) via flow cytometry [15]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Corona Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nanoparticle Systems | PLGA, Titanium, Silica, Gold, Lipid NPs | Model substrates for corona formation studies; PLGA particularly common due to FDA approval [15] |

| Biological Fluids | Human plasma, Fetal Bovine Serum, BALF | Source of proteins for corona formation; human plasma most relevant for clinical translation [17] |

| Characterization Instruments | DLS, SDS-PAGE, LC-MS/MS, Flow Cytometry | Quantify corona size, composition, and biological effects [15] [13] |

| Cell Culture Models | Bone marrow-derived macrophages, THP-1, RAW 264.7 | Assess immune responses to corona-coated materials [16] [15] |

| Cytokine Analysis | Multiplex ELISA, Luminex arrays | Quantify immune activation through cytokine secretion profiles [15] |

Advanced Prediction and Engineering Approaches

Machine Learning for Corona Composition Prediction

Machine learning (ML) approaches have emerged as powerful tools for predicting protein corona composition based on nanoparticle properties, addressing the methodological challenges and time-consuming nature of experimental characterization [17] [14]. The creation of the Protein Corona Database (PC-DB) with 817 unique nanoparticle formulations and quantitative profiles for 2497 proteins has enabled the development of predictive models with high accuracy (ROC-AUC > 0.85) [17].

Feature importance analysis from these models identifies NP size, ζ-potential, and incubation time as the most influential predictors of protein adsorption [17]. Commonly employed algorithms include LightGBM and XGBoost, which can handle the complex, non-linear relationships between nanoparticle properties and corona composition [17] [14]. These models reveal that silica, polystyrene, and lipid-based nanoparticles smaller than 100 nm with moderately negative to neutral ζ-potentials preferentially bind APOE and APOB-100, while metal and metal-oxide nanoparticles with highly negative surface charge enrich complement component C3 [17].

Strategic Corona Engineering for Immunomodulation

The growing understanding of corona formation has enabled strategic engineering approaches to manipulate corona composition for desired immune outcomes:

Surface Property Modulation: Precisely engineered nanotopography can selectively alter protein adsorption patterns. Surfaces with 70 nm topography demonstrated reduced clusterin adsorption while increasing ApoB and IgG gamma binding, resulting in attenuated inflammatory responses [18].

Pre-adsorption Strategies: Intentional pre-formation of coronas with specific proteins (e.g., apolipoproteins for brain targeting) can steer biological interactions toward desired outcomes [17] [14].

Personalized Corona Design: Accounting for disease-specific plasma compositions enables designing nanoparticles that maintain intended functionality in specific patient populations [15] [14].

Stealth Corona Engineering: Enriching coronas with dysopsonins like clusterin can reduce immune recognition and extend circulation half-life [17].

The protein corona represents a critical transformation point where synthetic materials acquire biological identity, fundamentally directing subsequent immune recognition and responses. The physicochemical properties of biomaterials—including size, surface chemistry, charge, and topography—determine corona composition, which in turn activates specific immune signaling pathways and cellular responses. Strategic engineering of these material properties enables rational design of coronas that steer immune responses toward desired outcomes, whether for enhanced integration, targeted delivery, or controlled immunomodulation.

The emerging capabilities in machine learning prediction of corona composition, combined with advanced multi-omics characterization approaches, are accelerating our ability to design biomaterials with predictable biological fates. This knowledge is particularly crucial within the context of personalized medicine, where disease-specific corona variations significantly impact therapeutic efficacy. Future research directions include the development of dynamic corona models that account for temporal evolution in disease states, standardized characterization methodologies across laboratories, and clinical translation of corona engineering strategies for improved medical outcomes.

The host immune response is a critical determinant of the long-term success of medical implants. While acute inflammation is a protective and necessary biological process for initiating tissue repair, its dysregulation into a state of chronic inflammation frequently leads to implant failure through mechanisms such as foreign body reaction, fibrosis, and inadequate osseointegration [19] [20]. This whitepaper delineates the temporal dynamics of acute versus chronic inflammation within the context of biomaterial host interactions, framing this continuum as the central paradigm for understanding and improving implant outcomes. A profound understanding of these processes is foundational to the development of next-generation, immuno-informed biomaterials that can proactively modulate the host response to favor integration and longevity [7] [21].

The failure of a biomaterial to integrate is not merely a passive rejection but often a consequence of active, sustained immune signaling. Chronic inflammation is increasingly recognized as a "silent epidemic" and a common pathway in numerous disease states, a concept that extends directly to the persistence of inflammation around biomedical implants [19]. This document provides a detailed analysis of the immunological mechanisms, quantitative biomarkers, and advanced material science strategies that define the transition from beneficial acute inflammation to pathological chronic inflammation at the implant-tissue interface. It is intended to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the experimental frameworks and conceptual tools needed to navigate this complex biological landscape.

The Immunological Basis of Inflammation in Tissue Repair

Phases of Normal Healing

Tissue repair following implantation is a dynamic process orchestrated primarily by the immune system, unfolding in overlapping phases: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling [7] [22]. The inflammatory phase is initiated immediately after injury and implantation, characterized by the recruitment of innate immune cells such as neutrophils and macrophages to the wound site [22]. These cells clear cellular debris and pathogens and set the stage for subsequent repair. The successful resolution of this acute inflammatory phase and the transition to proliferation is paramount for healing.

Macrophage Polarization: A Key Regulatory Axis

Macrophages demonstrate remarkable functional plasticity, and their phenotypic polarization is a crucial event in inflammation and repair [23]. The classical dichotomy outlines:

- M1 Macrophages (Pro-inflammatory): Stimulated by factors like IFN-γ or LPS, these cells express high levels of iNOS, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12. They are essential for initial pathogen clearance and debridement but can exacerbate tissue damage if their activity is prolonged [23] [24].

- M2 Macrophages (Pro-reparative): Activated by IL-4 or IL-13, these cells express markers like CD206 and Arg-1, and secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10) and growth factors (e.g., TGF-β, PDGF) that promote angiogenesis, matrix deposition, and tissue remodeling [23] [24].

It is critical to note that this M1/M2 dichotomy is a simplification; in vivo, macrophages exist along a spectrum of functional states [23]. The timely transition from a predominantly M1 to a predominantly M2 phenotype is a hallmark of successful healing and implant integration. Conversely, a persistent M1 state is a characteristic feature of chronic inflammation and implant failure [24] [22].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Macrophage Phenotypes in Implant Integration

| Feature | M1 (Pro-inflammatory) | M2 (Pro-reparative) |

|---|---|---|

| Activating Stimuli | IFN-γ, LPS, TNF-α | IL-4, IL-13, IL-10, Immune Complexes |

| Key Surface Markers | CD80, CD86, MHC-II | CD206, CD163 |

| Secreted Factors | TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, ROS | IL-10, TGF-β, VEGF, PDGF, Arg-1 |

| Primary Functions | Pathogen clearance, debridement, pro-inflammation | Inflammation resolution, angiogenesis, matrix remodeling |

| Effect on Implants | Linked to chronic inflammation & fibrosis | Promotes integration & tissue repair |

Acute vs. Chronic Inflammation: A Temporal and Functional Dichotomy

Acute Inflammation: A Controlled, Protective Response

Acute inflammation is the body's immediate, short-term defensive response to tissue injury caused by implantation. It is characterized by the classic signs of redness, swelling, heat, pain, and loss of function [19]. This phase is typically self-limiting and resolves within days to weeks as the threat is eliminated and repair processes commence. The role of acute inflammation in implant healing is protective and constructive; it is essential for clearing debris, preventing infection, and initiating the signaling cascades that lead to tissue regeneration [19] [22].

Chronic Inflammation: A Dysregulated, Pathological State

Chronic inflammation, in contrast, is a low-grade, persistent inflammatory response that can last for months or years. Unlike its acute counterpart, it is systemic and often "silent," lacking the obvious cardinal signs [19]. In the context of implants, chronic inflammation is frequently driven by a persistent foreign body reaction to the biomaterial itself. This state is characterized by a sustained influx of mononuclear cells (lymphocytes, macrophages), ongoing tissue destruction, and simultaneous attempts at healing that lead to fibrosis and encapsulation of the implant [19] [20]. The failure to resolve acute inflammation, due to factors such as persistent immune activation, microbial biofilm, or excessive tissue damage, is a primary driver of this transition.

Table 2: Contrasting Features of Acute and Chronic Inflammation in Implant Biology

| Characteristic | Acute Inflammation | Chronic Inflammation |

|---|---|---|

| Onset & Duration | Immediate, short-term (days-weeks) | Delayed, long-term (months-years) |

| Cardinal Signs | Present (redness, swelling, heat, pain) | Often absent or subclinical |

| Primary Immune Cells | Neutrophils, M1 Macrophages | Macrophages, Lymphocytes, Plasma Cells |

| Tissue Outcomes | Tissue repair and regeneration | Tissue destruction, fibrosis, necrosis |

| Role in Implant Success | Essential for initiating integration | Primary cause of failure (loosening, fibrosis) |

| Biomarkers | Rapid, transient rise in CRP, cfDNA | Sustained, low-level elevation of CRP, NLR, PLR |

Quantitative Biomarkers and Clinical Evidence

Monitoring the inflammatory response is crucial for predicting implant outcomes. Clinical studies leverage various biomarkers to assess systemic and local inflammation.

Evidence from Cochlear and Dental Implants

A recent retrospective cohort study on sequential cochlear implantation provides compelling evidence for immunological memory influencing contralateral implant outcomes. The study found that the second implanted ear exhibited significantly higher and more rapidly increasing electrode impedances, consistent with a more robust immune response, suggesting the first implant "primed" the immune system [25]. Linear mixed models confirmed statistically significant effects of implant sequence and time on delta impedance (p < 0.0001), with the most pronounced differences in the basal and apical electrode groups [25].

In dental implantology, a study investigated preoperative inflammatory biomarkers as predictors of early failure in systemically healthy patients. While the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), and C-reactive protein (CRP) showed limited predictive value, the Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index (SII) demonstrated statistically significant discrimination for impaired osseointegration (p=0.015) [26]. This highlights the potential of composite biomarkers in risk stratification.

Kinetics of Key Biomarkers

The kinetic profiles of biomarkers provide a temporal window into the inflammatory state:

- Cell-free DNA (cfDNA): Released rapidly from damaged cells, cfDNA peaks within minutes to hours of an acute injury, making it an excellent early marker of cellular stress [27].

- C-reactive Protein (CRP): This classic acute-phase protein exhibits delayed kinetics, with levels beginning to rise after a delay of up to 24 hours and potentially peaking around 48 hours post-injury [27].

Table 3: Kinetic Profiles and Utility of Inflammation Biomarkers

| Biomarker | Origin / Stimulus | Kinetic Profile | Utility in Implant Monitoring |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-reactive Protein (CRP) | Liver; cytokine stimulation (e.g., IL-6) | Rises after ~24h, peaks at ~48h | Indicator of prolonged inflammation; useful for monitoring post-surgical burden. |

| Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) | Apoptotic or necrotic cells | Rises within minutes, peaks immediately post-injury | Promising for early detection of significant cellular damage during implantation. |

| Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) | Complete Blood Count (CBC) | Dynamic, reflects systemic inflammatory state | Pre-operative elevated levels may suggest a subclinical pro-inflammatory state. |

| Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index (SII) | CBC-derived (Platelets × Neutrophils/Lymphocytes) | Composite measure of inflammatory status | Shown to be a significant predictor of early dental implant failure [26]. |

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Protocol: Retrospective Analysis of Clinical Impedance Data

This methodology, used to investigate immunological memory in cochlear implants, can be adapted for studying other chronic inflammatory responses to implants [25].

- Cohort Selection: Apply strict inclusion/exclusion criteria. For example, in the cited study, patients with bilateral sequential implants from the same manufacturer and similar array types were selected, while those with explantation events or confounding medical conditions were excluded. A final cohort of 79 patients was established [25].

- Data Extraction: Collect longitudinal patient data from clinical databases. Key data points include patient demographics, implantation dates, and serial impedance measurements for all electrodes.

- Data Processing:

- Define a baseline measurement (e.g., the visit immediately following initial activation).

- Calculate delta impedance (change from baseline) for each electrode over time.

- Remove data from deactivated electrodes to avoid confounding.

- Statistical Analysis:

- Use paired t-tests to compare average absolute impedance between first and second implants at specific time points (e.g., 12 months).

- Employ linear mixed models to analyze the effects of fixed factors (implant sequence, time, electrode group) and random effects (individual patient trajectories).

- Perform post-hoc analyses on estimated marginal means and slopes to pinpoint significant differences.

Protocol: In Vivo Evaluation of a Smart Implant Coating

This protocol details the evaluation of an inflammation-responsive, multifunctional peptide coating (DOPA-P1@P2) on titanium implants, a prime example of immuno-informed biomaterial design [24].

- Surface Functionalization:

- Synthesize a mussel-inspired peptide ((DOPA)4-OEG5-DBCO) and the functional peptides P1 (N3-K15-PVGLIG-K23) and P2 (N3-Y5-PVGLIG-K23) via solid-phase peptide synthesis.

- Purify peptides using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and verify molecular masses with Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry (ESI-MS).

- Modify titanium implants by first coating with the mussel-inspired peptide, then grafting P1 and P2 via bioorthogonal click chemistry between DBCO and azide (-N3) groups [24].

- In Vivo Implantation and Analysis:

- Use a rodent model (e.g., rat or rabbit) for bone implantation into critical-sized defect sites.

- Experimental Groups: Include a control group (unmodified TiO₂) and the test group (DOPA-P1@P2 coated implants).

- Outcome Measures:

- Biomechanical Testing: At sacrifice, perform a push-out test to measure the maximal force required for implant displacement.

- Micro-Computed Tomography (μCT): Quantify bone volume fraction (BV/TV) and bone-to-implant contact (BIC) around the implant.

- Histological and Immunohistochemical Analysis: Process explanted tissue to assess tissue morphology, inflammation, and cellular composition. Use specific antibodies to identify M1 (e.g., iNOS) and M2 (e.g., CD206) macrophages.

- Data Interpretation: The DOPA-P1@P2 coating demonstrated a 161% increase in push-out force, a 207% increase in bone volume, and a 1409% increase in BIC compared to control, validating its success via sequential immune modulation and osteogenesis [24].

Diagram 1: Macrophage-Driven Pathways to Implant Success vs Failure

Advanced Strategies: Immuno-Informed Biomaterials

The emerging field of immuno-informed biomaterials seeks to design implants that actively direct the host immune response toward a regenerative outcome rather than a hostile one [7] [21]. Key strategies include:

- Surface Topography Modification: Engineering surface micro- and nano-topography to directly influence immune cell behavior. For instance, reducing the surface roughness of silicone mammary implants to 4 μm was shown to improve immune response and reduce capsular fibrosis [21].

- Bioactive Functionalization: Coating implants with peptides or cytokines that promote a pro-regenerative environment. The DOPA-P1@P2 coating is a sophisticated example, using an MMP-cleavable sequence (PVGLIG) to sequentially release an anti-inflammatory peptide (K23) first, followed by angiogenic (K15) and osteogenic (Y5) peptides [24].

- Mechanotransduction Modulation: Designing biomaterials with mechanical properties (e.g., stiffness) that favorably influence macrophage polarization through mechanosensitive pathways involving integrins and focal adhesion kinase (FAK) [23].

Diagram 2: Sequential Action of a Smart Inflammation-Responsive Coating

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Models

Table 4: Essential Tools for Investigating Inflammation in Implant Models

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Specific Examples / Targets |

|---|---|---|

| Polarization Inducers | To polarize macrophages to specific phenotypes in vitro for functional assays. | LPS + IFN-γ (for M1); IL-4 or IL-13 (for M2) [23]. |

| MMP-Cleavable Peptides | To create "smart" coatings that release bioactive factors in response to inflammatory enzymes. | PVGLIG sequence (cleaved by MMP-2/9) [24]. |

| Anti-inflammatory Peptides | To bias the local immune microenvironment toward a reparative state upon implantation. | K23 peptide (KAFAKLAARLYRKALARQLGVAA) [24]. |

| Angiogenic & Osteogenic Peptides | To promote vascularization and bone formation in the proliferation phase of healing. | K15 (VEGF-mimetic), Y5 (OGP-derived) [24]. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | To identify and quantify immune cell populations and their activation states from explanted tissue. | CD80/86 (M1), CD206/163 (M2), Ly6C (monocyte subsets) [23]. |

| Rodent Implantation Model | A standard in vivo model for evaluating the host response and osseointegration of novel implants. | Critical-sized bone defect model in rat or rabbit femur/tibia [24]. |

| Linear Mixed Models | A powerful statistical framework for analyzing longitudinal data from implant studies (e.g., impedance, imaging). | Accounts for fixed effects (implant type, time) and random effects (individual variation) [25]. |

The dichotomy between acute and chronic inflammation represents the fundamental axis upon which implant success pivots. The temporal dynamics of the immune response, particularly the critical phenotype switch in macrophages, dictate whether the outcome is functional integration or fibrotic failure. The growing body of evidence, from clinical retrospective studies to advanced material science, underscores that passive biocompatibility is no longer sufficient. The future of regenerative medicine and implantology lies in the proactive design of immuno-informed biomaterials that can actively guide the inflammatory response through its natural, reparative sequence [7] [21]. By leveraging quantitative biomarkers, sophisticated experimental models, and a deep understanding of immunology, researchers and drug developers can pioneer a new generation of implants that not replace tissue but truly integrate and heal with the body.

The interaction between biomaterials and the host immune system is a critical determinant of clinical success. This whitepaper provides a comparative analysis of the innate immunogenic profiles of natural and synthetic biomaterials. It explores the distinct mechanisms through which these materials interact with immune cells, details key experimental methodologies for profiling these responses, and visualizes the underlying signaling pathways. The objective is to furnish researchers and drug development professionals with a structured technical guide to inform the rational selection and design of biomaterials for applications in regenerative medicine, drug delivery, and tissue engineering.

Upon implantation, all biomaterials initiate a complex sequence of immune responses, a process known as the host response. The innate immune system is the first to react, with outcomes ranging from constructive remodeling and integration to chronic inflammation and fibrotic encapsulation [28]. The immunogenic profile of a biomaterial—its inherent capacity to stimulate immune activation—is not a binary property but a spectrum heavily influenced by its origin and physicochemical characteristics.

The paradigm in biomaterials science has evolved from designing inert materials that passively avoid immune detection to developing active, "smart" systems that dynamically modulate immune responses [29] [30]. This shift acknowledges the immune system not as an adversary but as a powerful therapeutic target. Understanding the fundamental differences in how natural and synthetic polymers engage with innate immune pathways is, therefore, foundational to advancing the field of immuno-informed biomaterial design.

Comparative Immunogenic Profiles

The following tables summarize the key immunological characteristics, mechanisms, and properties of natural and synthetic biomaterials.

Table 1: Immune Activation Mechanisms and Key Characteristics

| Feature | Natural Biomaterials | Synthetic Biomaterials |

|---|---|---|

| General Immunogenicity | Often considered low, but can elicit specific immune recognition [31]. | Variable; can be engineered for low immunogenicity, but some exhibit intrinsic immunostimulatory properties [32]. |

| Primary Immune Activation Pathways | Engagement of specific receptors (e.g., Integrins, DDR, OSCAR) [31]. | Activation of pattern recognition receptors (e.g., TLRs, inflammasomes) [32]. |

| Typical Macrophage Response | Often promotes a transition to pro-remodeling (M2-like) phenotypes [28]. | Can drive a pro-inflammatory (M1-like) response; highly tunable via engineering [29]. |

| Role of Adaptive Immunity | Can condition antigen-presenting cells to bias T-cell responses towards Th2 and Treg lineages [28]. | Generally lower adaptive involvement unless specifically engineered as vaccine carriers [32]. |

| Key Advantages | Biocompatible, bioactive, biodegradable, structurally biomimetic [31] [33]. | Reproducible, tunable mechanical & degradation properties, scalable manufacturing [34] [33]. |

| Key Limitations | Batch-to-batch variability, potential for immunogenicity from residual cellular components [28]. | Lack of innate bioactivity; degradation byproducts can cause acidic microenvironments and inflammation [34]. |

Table 2: Physicochemical Properties and Degradation Profiles

| Property | Natural Biomaterials | Synthetic Biomaterials |

|---|---|---|

| Common Examples | Collagen, Chitosan, Hyaluronic Acid, Fibrin, Alginate [31] [33]. | PLGA, PLA, PCL, PBAEs, Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) [34] [32]. |

| Degradation Mechanism | Primarily enzymatic (e.g., matrix metalloproteinases, lysozymes) [34]. | Primarily hydrolytic (cleavage of ester bonds) [34]. |

| Degradation Byproducts | Natural amino acids, sugars (generally well-tolerated) [33]. | Acidic monomers (e.g., lactic acid, glycolic acid) that may provoke inflammation [34]. |

| Mechanical Properties | Often limited mechanical strength; may require cross-linking or blending [34]. | Highly tunable mechanical strength and elasticity [34]. |

| Influence of Form | Immunogenicity can be affected by fibrillar vs. monomeric structure (e.g., in collagen) [31]. | Immunogenicity is highly form-dependent (e.g., particulate forms are more immunogenic than soluble polymers) [32]. |

Experimental Protocols for Profiling Immunogenicity

A critical step in biomaterial evaluation is the systematic assessment of their immunogenic potential. The following is a detailed protocol for evaluating the intrinsic immunogenicity of synthetic polymer particles, a common experimental approach in the field.

Detailed Protocol: Evaluating Intrinsic Immunostimulatory Properties of Polymeric Particles

This methodology is adapted from studies on degradable poly(beta-amino esters) (PBAEs) and can be generalized for other synthetic polymers [32].

1. Objective: To determine the intrinsic capacity of polymer particles to activate dendritic cells (DCs) and enhance T-cell proliferation in vitro.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Polymers of Interest: e.g., PBAEs, PLGA, or other synthetic polymers.

- Cell Culture Media: RPMI-1640 supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS).

- Immune Cells: Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) from mouse models and CD4+ T cells isolated via negative selection kits.

- Activation Reagents: Toll-like receptor agonists (e.g., LPS, Poly(I:C)).

- Assay Kits: ELISA kits for cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) and CFSE for T-cell proliferation tracking.

- Characterization Equipment: Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) for particle size and zeta potential, Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) for molecular weight.

3. Experimental Workflow:

Diagram 1: Immunogenicity Assay Workflow

4. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Polymer Synthesis and Particle Fabrication. Synthesize polymers via established methods (e.g., Michael-type addition for PBAEs). Characterize the initial molecular weight using GPC. Form particles via electrostatic condensation or emulsion methods. Characterize particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential using DLS [32].

- Step 2: In Vitro Degradation. Incubate particles in buffers mimicking physiological (pH 7.4) and inflammatory (pH 5.0) conditions at 37°C. Withdraw samples at predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 6, 24, 72 hours). Lyophilize and analyze the molecular weight of degraded polymer fragments via GPC to track degradation kinetics [32].

- Step 3: Dendritic Cell Activation Assay. Isplicate and culture BMDCs. Seed DCs in plates and treat with:

- Negative control: Media only.

- Positive control: TLR agonist (e.g., LPS).

- Experimental groups: Particles fabricated from polymers at different degradation stages (varying MW). After 18-24 hours, collect supernatant for cytokine analysis (ELISA) and harvest cells for analysis of surface activation markers (CD40, CD80, CD86) via flow cytometry [32].

- Step 4: T-cell Proliferation Co-culture. Isolate CD4+ T cells from spleens of transgenic mice (e.g., 2D2 mice) and label with CFSE. Co-culture these T cells with the particle-treated BMDCs. After 3-5 days, analyze T-cell proliferation by measuring CFSE dilution using flow cytometry [32].

5. Data Analysis:

- Correlate DC activation (cytokine levels, marker expression) and T-cell proliferation with polymer properties (MW, particle size, charge).

- A key finding to assess is whether high molecular weight particles elicit a stronger immunostimulatory effect, which wanes with degradation, as demonstrated with PBAEs [32].

Key Signaling Pathways in Biomaterial-Immune Interactions

The innate immune response to biomaterials is mediated by specific receptor-ligand interactions. The pathways differ significantly between natural and synthetic materials.

Natural Biomaterial Pathway: Collagen-Integrin Signaling

Collagen, a predominant natural polymer, interacts with immune and stromal cells primarily through integrin receptors, initiating a pro-regenerative signaling cascade [31].

Diagram 2: Collagen-Integrin Signaling

Synthetic Biomaterial Pathway: Particulate-Induced Inflammasome Activation

Synthetic polymer particles, similar to pathogens, are often recognized by the innate immune system as danger signals, leading to activation of inflammasomes and pro-inflammatory cytokine production [32].

Diagram 3: Particulate-Induced Inflammasome Activation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting experiments in biomaterial immunogenicity.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Biomaterial-Immune Profiling

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(beta-amino esters) (PBAEs) | Model degradable, cationic synthetic polymer for studying the impact of molecular weight and form on intrinsic immunogenicity [32]. | Polymers synthesized from monomers like 1,4-butanediol diacrylate and 4,4′-trimethylenedipiperidine [32]. |

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | A widely used, FDA-approved synthetic polymer known to exhibit intrinsic immunostimulatory properties; a benchmark material [32]. | Commercial PLGA resins with various lactide:glycolide ratios and molecular weights. |

| Toll-like Receptor (TLR) Agonists | Positive controls for activating immune cells in vitro to benchmark biomaterial-induced immunostimulation [32]. | Lipopolysaccharide (LPS, TLR4 agonist) or Poly(I:C) (TLR3 agonist). |

| Fluorescent Antibody Conjugates | Critical for flow cytometry analysis of immune cell surface markers to determine activation and polarization states [32]. | Antibodies against CD40, CD80, CD86 for DCs; CD206, CD64 for macrophages. |

| CFSE (Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester) | A cell proliferation dye used to track and quantify T-cell division in co-culture assays with biomaterial-treated antigen-presenting cells [32]. | Used to label T cells before co-culture; proliferation is measured as dye dilution via flow cytometry. |

| Decellularized ECM Bioscaffolds | Representative natural biomaterials used to study pro-remodeling immune responses; quality is dependent on source tissue and decellularization method [28]. | ECM scaffolds derived from porcine small intestine submucosa (SIS), urinary bladder, or dermis. |

The innate immunogenic profiles of natural and synthetic biomaterials are distinct, rooted in their fundamental compositions and interactions with the host. Natural biomaterials tend to engage specific receptor-mediated pathways that can promote constructive remodeling, whereas synthetic biomaterials often trigger pattern-recognition receptors, leading to inflammation, though this is highly tunable. The future of the field lies in the rational design of "smart" hybrid materials that combine the bioactivity of natural polymers with the engineerability of synthetic systems. By leveraging detailed experimental profiling and a deep understanding of immune signaling pathways, researchers can now design biomaterials that do not just evade the immune system, but actively orchestrate it to achieve desired therapeutic outcomes.

Engineering Immunomodulation: Strategic Design of Smart and Bioactive Biomaterials

The field of biomaterials science has undergone a profound transformation, evolving from the development of passive constructs intended primarily for structural support to the engineering of sophisticated "smart" platforms [30] [29]. These advanced biomaterials are meticulously designed to actively and precisely interface with the host's biological systems, particularly the immune system, to orchestrate desired therapeutic outcomes [30]. This evolution represents a paradigm shift, fueled by the convergence of breakthroughs in materials science, immunology, and bioengineering. The traditional goal of achieving "bio-inertness"—a state of passive coexistence—has been replaced by the ambition of active "immunomodulation" [29]. This conceptual pivot acknowledges the immune system not as an adversary to be evaded, but as a powerful biological system that can be rationally programmed and harnessed for therapeutic benefit [29] [35]. The capacity to intelligently interact with and guide cellular and tissue responses positions smart biomaterials at the forefront of regenerative medicine and advanced therapeutics, offering transformative strategies for disease intervention and tissue repair [30].

The Classification Spectrum: From Inert to Autonomous Biomaterials

The classification of biomaterials reflects an increasing level of sophistication in their interaction with biological systems, essentially mirroring an evolution in their biomimetic capabilities [30] [29]. This progression highlights a journey from static implants to dynamic, self-adaptive platforms.

Table 1: Classification of Biomaterials Based on Biological Interaction and "Smartness"

| Classification | Core Functionality | Key Characteristics | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inert Materials | Passive structural support; occupy space | Designed for minimal biological interaction; often trigger Foreign Body Reaction (FBR) and fibrous encapsulation | Certain titanium alloys, inert ceramics, inert polymers [30] [29] |

| Active Materials (Bioactive) | Elicit a defined biological response at interface | Release pre-loaded bioactive agents (drugs, growth factors) or possess inherent surface bioactivity | Drug-eluting stents, antibiotic-loaded bone cements, hydroxyapatite coatings [30] [29] |

| Responsive Materials | Sense and respond to specific environmental stimuli | Dynamic change in properties or payload release triggered by pH, temperature, enzymes, etc. | pH-sensitive hydrogels, temperature-responsive polymers (PNIPAM), enzyme-degradable matrices [30] [29] |

| Autonomous Materials | Sense, respond, and adapt based on feedback; mimic homeostatic loops | Bi-directional responsiveness; capable of receiving cellular feedback and remodeling accordingly | Engineered systems that adjust drug release based on real-time inflammatory marker levels [30] |

Decoding the Host Immune Response to Biomaterials

The interaction between an implanted biomaterial and the host immune system is a critical determinant of its ultimate clinical success [29]. An inappropriate or unresolved immune response can precipitate a cascade of adverse events, including chronic inflammation, the formation of a dense fibrous capsule that isolates the implant, and ultimately, implant failure and compromised tissue healing [29] [36]. This host response, known as the Foreign Body Response (FBR), is a sequential biological reaction [36] [35].

Phases of the Foreign Body Response (FBR)

- Protein Adsorption: Within seconds to minutes, host plasma proteins (e.g., albumin, fibrinogen, fibronectin) adsorb onto the biomaterial surface, forming a provisional matrix. The composition of this protein layer is influenced by the biomaterial's surface properties and dictates subsequent cell interactions [36] [35].

- Acute Inflammation: Granulocytes, particularly neutrophils, infiltrate the site. They attempt to phagocytose the material and release reactive oxygen species (ROS) and enzymes. Neutrophils also release chemokines like CXCL8 and CCL2 to recruit monocytes [36] [35].