Immunohistochemistry Methods for Tissue Integration Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide from Basics to Advanced Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide to immunohistochemistry (IHC) methods for analyzing protein expression and localization within tissues.

Immunohistochemistry Methods for Tissue Integration Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide from Basics to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to immunohistochemistry (IHC) methods for analyzing protein expression and localization within tissues. It covers foundational principles, detailed methodological protocols for both basic and advanced multiplex techniques, essential troubleshooting strategies for common issues, and rigorous validation approaches to ensure data reliability. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource integrates established practices with current advancements, including semi-quantitative analysis and standardized reporting, to support robust tissue-based research in both preclinical and clinical settings.

Understanding Immunohistochemistry: Core Principles and Tissue Context in Biomarker Analysis

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is an antibody-based technique used to characterize protein expression within tissue while preserving its structural and organizational context [1]. First reported in 1942 by Coons et al., IHC has evolved into a fundamental tool that combines immunological, anatomical, and biochemical techniques to image discrete components in tissues [2]. The technique relies on the specific recognition of an epitope by an antibody, allowing researchers to visualize and document the high-resolution distribution and localization of specific cellular components within their proper histological context [1] [2].

IHC's unique capability to maintain tissue architecture while detecting specific proteins makes it invaluable for both research and clinical applications. In biomedical research, IHC is used to detect proteins of interest in various contexts, as well as in drug development to test drug efficacy by detecting either the activity or the up- or down-regulation of disease markers [1] [2]. In clinical pathology, IHC is essential for identifying various pathogenic features—including neoplasia, metastasis, infection, and inflammation—within tissue samples for diagnostic purposes [1].

Fundamental Principles of IHC

Core Methodology

IHC exploits the specific relationship between an antibody and an antigen to visualize protein expression in situ [1]. The process can be performed using either direct or indirect detection methods. Direct detection involves a primary antibody directly conjugated to a label, while indirect detection uses an unlabeled primary antibody followed by labeled secondary antibodies that recognize the primary antibody [3]. The indirect method provides signal amplification as multiple secondary antibodies can bind to a single primary antibody [3].

Detection Systems

Modern IHC detection systems typically utilize enzymes such as Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) conjugated to antibodies [3]. These systems often employ polymers where multiple enzyme molecules are attached to a single antibody backbone, producing more intense staining as there are more molecules for the chromogen to attach [3]. The most common chromogens are DAB (3,3'-diaminobenzidine), which produces a brown precipitate, and AP Red (or other red chromogens), typically used for skin sections where brown DAB might be masked by brown melanin pigment [3]. Double staining using both DAB and AP Red on the same tissue section allows pathologists to visualize two antigens simultaneously on a single slide [3].

IHC Workflow and Protocols

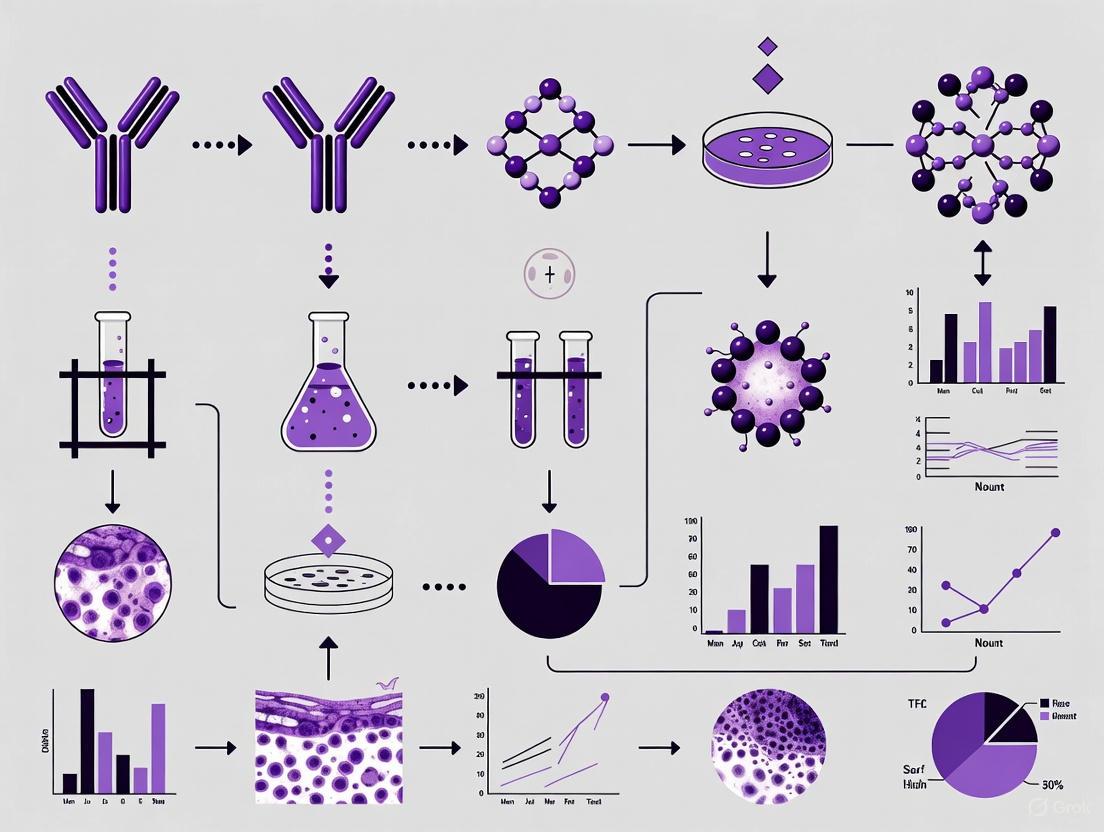

Complete IHC Workflow Diagram

Sample Preparation Protocol

Tissue Collection and Fixation

Proper tissue collection and fixation are critical first steps that directly impact sample integrity and macromolecular accessibility [1]. Chemical fixatives, particularly cross-linking fixatives like formaldehyde, paraformaldehyde, and glutaraldehyde, are most commonly used [1]. Formaldehyde fixation generates methylene bridges that covalently crosslink proteins in tissue samples, preserving tissue morphology but potentially masking antigenic epitopes [2]. Consistent fixation conditions (fixative type, pH, temperature, time) are essential for reproducible results [3].

Tissue Embedding and Sectioning

Tissue samples fixed in formaldehyde are typically embedded in paraffin, creating formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks [1]. FFPE tissue provides superb maintenance of cell structure and allows for long-term tissue storage [1]. Alternatively, tissues incompatible with formalin-fixation can be embedded in cryogenic material and snap-frozen for frozen section preparation [1]. FFPE tissues are usually cut into thin sections (4-5 μm) using a microtome, while frozen sections are cut using a cryostat [2]. Using high-quality sections that are thin, flat, and thoroughly dried onto charged or APES-coated slides is essential for optimal staining [3].

Antigen Retrieval Methods

Antigen retrieval is crucial for FFPE tissues as formaldehyde fixation can mask epitopes, preventing antibody binding [2]. The two primary antigen retrieval methods are:

Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval (HIER): This method uses heat to break protein cross-links and unwind proteins, rendering epitopes accessible to antibodies [1]. Common HIER buffers include citrate (pH 6.0), EDTA (pH 8.0), and Tris-EDTA (pH 9.0) [4]. Heating can be performed using microwave ovens, water baths, or pressure cookers, with microwave ovens often providing superior results for many antibodies [1].

Proteolytic-Induced Epitope Retrieval (PIER): This method utilizes proteolytic enzymes like proteinase K, pepsin, or trypsin to digest protein cross-links and recover antigenicity [1] [4]. PIER requires careful optimization of time, temperature, enzyme type, and concentration to avoid damaging tissue morphology [4].

Table 1: Antigen Retrieval Methods and Applications

| Method | Mechanism | Common Reagents | Optimal For | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval (HIER) | Heat breaks cross-links and unwinds proteins | Citrate buffer (pH 6.0), EDTA (pH 8.0), Tris-EDTA (pH 9.0) | Most epitopes; provides cleaner staining | pH critical for optimization; microwave often superior to water bath [1] [4] |

| Proteolytic-Induced Epitope Retrieval (PIER) | Enzymatic digestion of cross-links | Proteinase K, pepsin, trypsin | Epitopes resistant to HIER; certain antibodies | Risk of tissue damage; requires precise optimization [1] [4] |

Immunostaining Protocol

Blocking and Permeabilization

Blocking is essential to minimize background staining from non-specific antibody binding and endogenous enzyme activity [4]. Key blocking steps include:

- Endogenous enzyme blocking: For peroxidase-based detection systems, endogenous peroxidase must be blocked using hydrogen peroxide or commercial peroxidase inhibitors [3] [4]. For alkaline phosphatase systems, endogenous phosphatase must be inactivated [4].

- Biotin blocking: If using streptavidin-biotin amplification systems, endogenous biotin must be blocked [4].

- Protein blocking: Non-specific protein binding sites are blocked using protein-based blockers like BSA, normal serum, or commercial blocking buffers [4].

- Autofluorescence quenching: For fluorescent detection, chemical treatments can reduce natural tissue autofluorescence [4].

Antibody Incubation and Detection

Primary antibody incubation conditions (time, temperature, concentration) must be optimized for each antibody [1]. Antibodies are available in concentrated or ready-to-use (RTU) formats, with RTUs offering increased laboratory efficiency, better quality control, and easier reagent management [3]. Secondary antibody selection should match the host species of the primary antibody, with polymer-based detection systems providing enhanced sensitivity through signal amplification [3].

Visualization and Counterstaining

After immunostaining, tissues are typically counterstained to provide structural context [1]. Hematoxylin is most commonly used for chromogenic detection, staining nuclei blue [3]. For fluorescent detection, nuclear stains like DAPI or Hoechst are used [2]. Finally, slides are mounted using aqueous or permanent mounting media and coverslipped to preserve staining and create the ideal refractive index for microscopy [1].

Quantitative IHC Analysis

H-Score Methodology

Quantitative IHC analysis enables objective assessment of protein expression levels. The H-score is a commonly used quantitative method that incorporates both the intensity and percentage of stained cells [5]. The H-score formula is: H-score = Σpi(i+1), where "pi" represents the percentage of positive cell counts in total cell counts, and "i" represents the intensity (typically scored as 0, 1+, 2+, or 3+) [5]. This scoring system provides a continuous variable from 0-300 for data analysis.

Quantitative IHC Analysis Diagram

Case Study: ESCC Biomarker Analysis

A 2021 study demonstrated the application of quantitative IHC in identifying biomarkers for esophageal squamous carcinoma (ESCC) [5]. The study evaluated expressions of PCNA, p53, EGFR, and VEGF in 30 ESCC and 30 non-ESCC patients using quantitative computerized IHC with H-scoring [5].

Table 2: Quantitative IHC Analysis of ESCC Biomarkers [5]

| Biomarker | Biological Function | H-score in ESCC | H-score in Non-ESCC | Statistical Significance | AUC Value | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCNA | Proliferating cell nuclear antigen; marker of cellular proliferation | Significantly higher | Lower | P < 0.05 | 0.80 | Clearly demarcates proliferating areas in esophageal tissue [5] |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor; cell division regulation | Significantly higher | Lower | P < 0.05 | 0.74 | Constant activation leads to uncontrolled cell division [5] |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor; angiogenesis stimulation | Significantly higher | Lower | P < 0.05 | 0.70 | Reinforces microvascular permeability and macrophage migration [5] |

| p53 | Tumor suppressor protein | Not significantly different | Similar | P > 0.05 | N/A | Frequently mutated in cancers but not significant in this ESCC study [5] |

| Combined Panel | Triplicate combination of PCNA, EGFR, VEGF | N/A | N/A | P < 0.01 | 0.86 | Enhanced diagnostic sensitivity over single biomarkers [5] |

The study found that biomarker combinations provided superior diagnostic sensitivity compared to individual proteins, with the triplicate combination achieving an AUC prediction probability of 0.86 [5]. This demonstrates the power of quantitative IHC in developing diagnostic biomarker panels.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential IHC Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixatives | Formaldehyde, paraformaldehyde, glutaraldehyde | Preserve tissue architecture and antigenicity | Aldehyde-based fixatives most common; optimization of time, temperature, pH critical [1] [2] |

| Embedding Media | Paraffin, cryogenic embedding compounds | Stabilize tissue for sectioning | FFPE superb for morphology; frozen sections for antigen sensitivity [1] [4] |

| Primary Antibodies | Monoclonal (clone D5F3, EP38Y), Polyclonal | Specific recognition of target epitopes | Monoclonal offers specificity; polyclonal may offer sensitivity; choose based on validation [3] [5] |

| Detection Systems | HRP-polymer, alkaline phosphatase-polymer | Signal amplification and visualization | Polymer systems provide enhanced sensitivity; choose based on application [3] |

| Chromogens | DAB (brown), AP Red, AEC (red) | Generate visible precipitate at antigen site | DAB most common; red chromogens for melanin-rich tissues [3] [2] |

| Antigen Retrieval Buffers | Citrate (pH 6.0), EDTA (pH 8.0), Tris-EDTA (pH 9.0) | Unmask epitopes obscured by fixation | pH critical for optimization; EDTA may be superior for certain membrane targets [1] [4] |

| Blocking Reagents | BSA, normal serum, commercial blockers, peroxidase inhibitors | Reduce non-specific background | Essential for clean staining; multiple types may be needed [4] |

| Counterstains | Hematoxylin, DAPI, Hoechst | Provide structural context | Hematoxylin for chromogenic; DAPI/Hoechst for fluorescent [3] [2] |

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Common IHC Issues and Solutions

Achieving optimal IHC results requires careful attention to technique and troubleshooting. Key issues include:

- Weak or absent staining: May result from improper antigen retrieval, insufficient antibody concentration, or over-fixation. Optimize retrieval method and validate antibody dilution [3].

- High background staining: Often caused by inadequate blocking, insufficient washing, or endogenous enzyme activity. Ensure proper blocking steps and standardized washing protocols [3].

- Uneven staining: Can result from section adhesion problems, concentration gradients during reagent application, or uneven heating during antigen retrieval. Use charged slides and ensure even reagent application [3].

- Non-specific staining: May indicate antibody cross-reactivity. Check antibody specification sheets and include appropriate controls [3].

Quality Control Measures

Implementing rigorous quality control is essential for reliable IHC results:

- Appropriate controls: Always include positive and negative controls that are carefully examined to validate results [3].

- Standardization: Use standardized washing steps (duration, volume, agitation) throughout the procedure to ensure consistency [3].

- Antibody validation: Know your primary antibody by checking specification sheets and validating new antibody batches [3].

- Documentation: Maintain detailed records of fixation conditions, retrieval methods, and antibody lots for reproducibility.

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

IHC continues to evolve with technological advancements. Quantitative computerized IHC, as demonstrated in the ESCC study, enables objective biomarker quantification and enhances diagnostic precision [5]. Multiplex IHC allows simultaneous detection of multiple markers on a single section, providing comprehensive profiling of tissue microenvironment [3]. In drug development, IHC is used to test drug efficacy by detecting modulation of disease markers in target tissues [2].

The integration of IHC with digital pathology and artificial intelligence represents the future of tissue-based diagnostics, enabling high-throughput analysis, pattern recognition, and development of predictive algorithms for personalized medicine approaches [5]. As these technologies advance, IHC will continue to be an indispensable tool for visualizing cellular components in tissue architecture, bridging the gap between molecular biology and histological context.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is a cornerstone technique in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics, enabling the visualization and localization of specific proteins within tissue samples. [6] The reliability and quality of IHC results are profoundly influenced by pre-analytical variables—those factors affecting the sample before it undergoes the actual staining process. [7] This application note details standardized protocols for the critical pre-analytical phases of tissue collection, fixation, and sectioning, providing researchers with methodologies to ensure superior sample quality for downstream IHC analysis.

The Impact of Pre-Analytical Variables

Pre-analytical variables constitute any and all steps in tissue processing, starting from sample acquisition to the point of analysis. [7] Inconsistent handling during these initial stages is a major source of variability, leading to compromised morphology, antigen degradation, masking of epitopes, and ultimately, unreliable and non-reproducible data. [8] [7] Adherence to standardized protocols is therefore not merely a recommendation but a necessity for generating high-quality, comparable research findings, particularly in translational studies and drug development.

Protocols for Tissue Collection and Fixation

Principles of Tissue Fixation

Fixation is the fundamental process of preserving tissue structure and antigenicity immediately following collection. Its primary purpose is to rapidly terminate cellular enzyme activity, prevent autolysis and bacterial decay, and stabilize biomolecules for subsequent processing and analysis. [9] The choice of fixative and fixation conditions requires careful consideration to balance optimal morphological preservation with the retention of antigenicity for the target(s) of interest.

Fixative Types and Properties

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of common fixatives used in IHC workflows.

Table 1: Common Fixatives in IHC and Their Properties

| Fixative Type | Mechanism of Action | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formalin (10% NBF) | Cross-linking via methylene bridges | Excellent morphology, strong tissue penetration, low background | Potential epitope masking requiring antigen retrieval | Gold standard for FFPE tissues; general IHC |

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Cross-linking | Lacks methanol found in formalin; "fresher" fixative | Requires preparation and may repolymerize | Cell culture, perfusion fixation, immunofluorescence |

| Glutaraldehyde | Strong cross-linking | Excellent structural preservation, ideal for EM | Poor penetration, high autofluorescence, often requires quenching | Primarily electron microscopy |

| Precipitative (e.g., Methanol, Ethanol, Acetone) | Protein precipitation | No cross-linking, good for some sensitive epitopes | Poorer morphology, often incompatible with antigen retrieval | Frozen sections, cytology preparations |

Step-by-Step Protocol: Tissue Fixation for IHC

Materials:

- 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin (NBF) or other chosen fixative

- Specimen containers

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS)

Procedure:

- Tissue Collection and Trimming: Immediately upon dissection, place the tissue into a pre-labeled container filled with a volume of fixative that is 10-20 times greater than the tissue volume. [9] For larger specimens (e.g., >4 mm thick), neatly trim to ensure uniform fixation. [6]

- Fixation Duration: Fix the tissue for 18-24 hours at room temperature. [9] Under-fixation can lead to proteolytic degradation, while over-fixation excessively cross-links proteins and masks epitopes, making antigen retrieval more challenging. [6]

- Post-Fixation Rinse: Following fixation, rinse the tissue thoroughly with PBS to remove residual fixative, which can interfere with downstream processing.

Protocols for Tissue Processing and Sectioning

Tissue Processing and Paraffin Embedding

This process removes water from the fixed tissue and replaces it with paraffin wax, providing the structural support needed for thin sectioning.

Procedure:

- Dehydration: Pass the fixed tissue through a series of graded ethanol solutions (e.g., 70%, 80%, 95%, and two changes of 100% ethanol) to gradually remove all water. [9]

- Clearing: Immerse the tissue in a clearing agent, such as xylene, which is miscible with both ethanol and molten paraffin. This step prepares the tissue for wax infiltration. [8] [9]

- Infiltration and Embedding: Transfer the tissue to molten paraffin wax using an embedding station. After thorough infiltration, orient the tissue in an embedding mold, cover with fresh paraffin, and allow it to cool and solidify into a block. [9]

Microtomy and Slide Preparation

Materials:

- Microtome (e.g., Epredia HM 355S) [8]

- Poly-L-lysine or other charged slides

- Warm water bath (40-45°C)

Procedure:

- Sectioning: Using a microtome, cut the paraffin block to obtain thin sections typically 4-5 μm thick for IHC. [9] For nucleic acid extraction from FFPE tissue, thicker sections (e.g., 10 μm) may be used. [8]

- Floating and Mounting: Float the ribbon of sections on a warm water bath to remove wrinkles. Carefully pick up the sections onto charged slides, which enhance tissue adhesion. [9]

- Drying: Bake the mounted slides in an oven at 60°C for 1-2 hours to firmly adhere the tissue to the slide surface. [9] Properly prepared slides can be stored at 4°C until needed. [8]

Experimental Validation of Pre-Analytical Conditions

To ensure the quality of tissues processed through the above protocols, the following validation experiments are recommended.

Validation of Nucleic Acid Integrity

For studies involving subsequent genomic or transcriptomic analyses, it is critical to assess the impact of pre-analytical steps on nucleic acids. DNA and RNA can be degraded during fixation and processing.

Protocol: DNA/RNA Extraction and QC from FFPE Tissue [8]

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Use commercial kits designed for FFPE tissue (e.g., QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue kit, AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE kit, RNeasy FFPE kit). Perform simultaneous DNA/RNA extraction when possible. Include DNase I digestion for RNA purification and RNase A digestion for DNA purification. [8]

- Quality Control:

- Purity: Use a UV spectrophotometer (e.g., Nanodrop) to assess the A260/A280 ratio, with a target of ~1.8 for DNA and ~2.0 for RNA. [8]

- Integrity: For DNA, perform PCR amplification of targets of varying lengths (e.g., 152 bp, 268 bp, 676 bp) to check for fragmentation. For RNA, use a BioAnalyzer to determine the RNA Integrity Number (RIN). [10]

Table 2: Expected Outcomes from Nucleic Acid QC of FFPE Tissue

| Biomolecule | QC Method | Acceptable Outcome | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA | PCR Amplification | Robust amplification of shorter fragments (e.g., 152-268 bp) | Longer amplicons may fail due to fragmentation. [10] |

| DNA | Targeted NGS | High concordance with fresh-frozen tissue when excluding variants with low VAF (e.g., <5%) | Helps overcome FFPE-induced sequencing artefacts. [8] |

| RNA | Microarray / nCounter | High correlation with matched fresh-frozen tissue (e.g., R² > 0.9) | Demonstrated as feasible in breast cancer tissue. [8] |

Effect of Immunostaining on Downstream Molecular Analysis

If IHC-guided laser microdissection is planned, it is vital to understand how the immunostaining process itself affects biomolecules.

Key Findings: [10]

- DNA: The most robust biomolecule. Immunostaining causes no significant change in quality but can lead to a 50-75% decrease in total yield. It remains suitable for PCR and methylation analyses.

- RNA: Highly susceptible to degradation during the initial aqueous steps of staining due to RNase activity. Protocols require rigorous RNase inhibition.

- Protein: Can be successfully analyzed by one-dimensional electrophoresis and mass spectrometry after immunostaining but may be less amenable to solution-phase assays.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Pre-Analytical IHC Workflows

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Example Product / Note |

|---|---|---|

| 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin | Standard tissue fixation | Most common fixative for histology; ensures consistent pH. |

| Ethanol Series | Tissue dehydration | Gradual dehydration (70% to 100%) prevents excessive tissue shrinkage. |

| Xylene | Clearing agent | Clears ethanol from tissue prior to wax infiltration. |

| Paraffin Wax | Tissue embedding and support | Provides a solid matrix for microtomy. |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | DNA/RNA purification from FFPE | Specialized kits (e.g., from QIAGEN) are optimized for cross-linked, fragmented FFPE material. [8] |

| Microtome | Sectioning paraffin blocks | Essential for producing thin, consistent tissue sections. [8] |

| Uralenol-3-methyl ether | Uralenol-3-methyl ether, CAS:150853-98-8, MF:C21H20O7, MW:384.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 22-(tert-Butoxy)-22-oxodocosanoic acid | 22-(tert-Butoxy)-22-oxodocosanoic acid, MF:C26H50O4, MW:426.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Pre-Analytical IHC Workflow

Pre-analytical IHC workflow with validation points

Fixation Impact on Analysis

Fixation effects on downstream analysis

The choice between Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) and frozen tissue preservation is a fundamental decision that significantly impacts experimental outcomes in immunohistochemistry (IHC) and tissue integration analysis research. These two methods employ fundamentally different approaches to stabilize tissue: FFPE uses chemical cross-linking and paraffin embedding to preserve tissue architecture at room temperature, while frozen tissue employs rapid cryopreservation to maintain biomolecules in their native state at ultra-low temperatures [11] [12]. For researchers investigating protein localization, expression patterns, and cellular interactions, this initial preservation step can determine the success or failure of downstream analyses. Within the context of a broader thesis on IHC methods, understanding the technical specifications, advantages, and limitations of each preservation approach is paramount for generating reliable, reproducible data that advances drug development and basic research.

The historical predominance of FFPE in pathology archives and the growing preference for frozen tissues in molecular research create a methodological divergence that researchers must navigate with careful consideration of their specific analytical goals. This application note provides a structured comparison and detailed protocols to guide researchers in selecting the appropriate preservation method for their IHC-based research questions.

Technical Comparison: FFPE versus Frozen Tissue

Core Characteristics and Research Applications

The decision between FFPE and frozen tissue involves balancing multiple factors including biomolecule integrity, morphological preservation, logistical constraints, and research objectives.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of FFPE and Frozen Tissue Characteristics

| Characteristic | FFPE Tissue | Frozen Tissue |

|---|---|---|

| Preservation Process | Formalin fixation followed by paraffin embedding [11] | Snap-freezing in liquid nitrogen followed by storage at -80°C [11] |

| Protein Integrity | Denatured proteins due to formalin cross-linking; may affect antibody binding [11] [13] | Native protein conformation preserved; optimal for functional studies [11] [12] |

| Nucleic Acid Quality | Fragmented DNA/RNA; suitable for some molecular analyses with optimized protocols [11] | High-quality, intact DNA and RNA ideal for sequencing and gene expression studies [14] [12] |

| Tissue Morphology | Excellent architectural preservation; superior for pathological diagnosis [11] [15] | Good structural preservation but potential for ice crystal artifacts [16] [17] |

| Storage Requirements | Room temperature; stable for decades [11] [12] | -80°C or lower; vulnerable to power failures [11] [14] |

| Cost & Logistics | Low-cost long-term storage; easy transport [13] | High energy costs; requires reliable freezer infrastructure [14] |

| IHC Applications | Requires antigen retrieval for most targets; well-established for diagnostic IHC [18] [17] | No antigen retrieval typically needed; ideal for labile epitopes and phospho-specific antibodies [16] |

| Best Suited For | Histopathology, retrospective studies, biobanking [15] [13] | Molecular studies (proteomics, RNA-Seq), rapid intraoperative analysis [15] [12] |

Performance in Downstream Analytical Applications

The preservation method significantly influences data quality across various research applications, particularly in modern genomic and proteomic analyses.

Table 2: Analytical Performance Across Research Applications

| Application | FFPE Tissue Performance | Frozen Tissue Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Immunohistochemistry | Good with antigen retrieval; potential for epitope masking [17] | Excellent for native epitopes; minimal background [16] |

| DNA Sequencing | Higher error rates (C>T transitions); shorter read lengths [19] | Gold standard for accuracy; longer read lengths [14] |

| RNA Sequencing | Challenging due to fragmentation; requires specialized kits [14] | Optimal for transcriptome analysis; high-quality data [14] [12] |

| DNA Methylation Studies | Potential overestimation of methylation levels [20] | Highly comparable to fresh tissue [20] |

| Protein Biochemistry | Denatured proteins limit utility for functional assays [11] | Suitable for mass spectrometry, Western blotting [13] [12] |

| Long-term Biobanking | Exceptional; decades-long stability at room temperature [11] | Limited by freezer reliability; typically years not decades [14] |

Decision Framework and Experimental Design

Selection Algorithm for Preservation Methods

The following workflow diagram outlines a systematic approach for selecting the appropriate tissue preservation method based on research objectives and practical constraints:

Hybrid Approaches and Advanced Considerations

For complex research programs requiring multiple analytical modalities, consider a hybrid approach where tissues are divided and preserved using both methods. This is particularly valuable in translational research and biomarker discovery where morphological context and molecular data are complementary [15] [13]. When designing studies that may incorporate both FFPE and frozen tissues from different sources, ensure consistent handling procedures and document any pre-analytical variables that may affect cross-comparison.

Recent advances in FFPE-compatible sequencing technologies and antigen retrieval methods have narrowed the performance gap between the two preservation methods for some applications [14] [19]. However, for novel epitopes or unvalidated antibodies, frozen tissue remains the preferred starting point for method development due to superior antigen preservation.

Experimental Protocols for IHC

Comprehensive IHC Protocol for FFPE Tissue Sections

The FFPE IHC protocol requires particular attention to antigen retrieval to reverse formalin-induced cross-links that mask epitopes.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for FFPE IHC

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fixation | 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin (NBF) [18] | Preserves tissue architecture through protein cross-linking; standard 18-24 hour fixation |

| Embedding Medium | Paraffin wax [11] | Provides structural support for microtomy; enables thin sectioning (4-7µm) |

| Antigen Retrieval Buffers | Sodium citrate (pH 6.0), Tris-EDTA (pH 9.0) [18] | Reverses formalin cross-links; choice depends on target antigen |

| Blocking Reagents | Normal serum, serum-free protein blocks [18] [16] | Reduces non-specific antibody binding; serum should match secondary antibody species |

| Detection Systems | HRP-conjugated antibodies with DAB substrate [18] | Enzymatic chromogenic detection; produces insoluble brown precipitate |

Detailed Step-by-Step Protocol:

Sectioning and Deparaffinization:

- Cut paraffin blocks into 4-7µm sections using a microtome and transfer to charged slides [18].

- Deparaffinize slides by immersion in xylene (2 changes, 3 minutes each) [18].

- Rehydrate through graded ethanols (100%, 100%, 95%, 70%, 50%) - 3 minutes each [18].

- Rinse in running tap water for 10 minutes; do not allow sections to dry hereafter [18].

Antigen Retrieval:

- Choose appropriate retrieval method based on target antigen:

- Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval (HIER): Place slides in retrieval buffer (e.g., 10mM sodium citrate, pH 6.0) and heat using pressure cooker, microwave, or steaker at approximately 98°C for 15-20 minutes [18] [17].

- Protease-Induced Epitope Retrieval (PIER): Apply protease solution (e.g., 0.05% trypsin) and incubate at 37°C for 10 minutes [18].

- Cool slides completely after HIER (30-60 minutes) [18].

- Rinse gently with wash buffer (PBS or TBS).

- Choose appropriate retrieval method based on target antigen:

Immunostaining:

- Blocking: Incubate sections with protein blocking reagent (e.g., 2-10% normal serum or commercial serum-free block) for 30-60 minutes at room temperature [18] [16].

- Primary Antibody: Apply optimized primary antibody dilution in blocking buffer and incubate overnight at 4°C in a humidity chamber [18].

- Washing: Wash slides 3 times with wash buffer (PBS/TBS with 0.025% Triton X-100) for 5 minutes each [18].

- Secondary Antibody: Apply appropriate enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody (e.g., HRP-anti-rabbit) for 1 hour at room temperature [18].

- Washing: Repeat wash step as above.

Detection and Counterstaining:

- Chromogenic Development: Incubate with substrate solution (e.g., DAB for HRP) until desired stain intensity develops (typically 5-10 minutes) [18].

- Counterstaining: Apply hematoxylin for 30-60 seconds to visualize nuclei [18].

- Dehydration and Mounting: Dehydrate through graded ethanols (95%, 100%, 100%) and xylene, then mount with organic mounting medium [18].

Comprehensive IHC Protocol for Frozen Tissue Sections

Frozen tissue IHC prioritizes preservation of antigenicity through rapid processing and minimal fixation.

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Frozen Tissue IHC

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Embedding Medium | Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) compound [16] | Water-soluble embedding matrix; provides support for cryosectioning |

| Freezing Agent | Chilled isopentane (2-methylbutane) [16] | Enables rapid "snap-freezing" to minimize ice crystal formation |

| Fixatives | Acetone, Methanol, 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) [16] | Post-sectioning fixation; choice depends on antigen preservation needs |

| Blocking Reagents | Normal serum, BSA, commercial protein blocks [16] | Reduces non-specific binding; critical for frozen sections |

| Detection Systems | Fluorescently-conjugated antibodies [16] | Commonly used for frozen IHC; enables multiplexing |

Detailed Step-by-Step Protocol:

Tissue Freezing and Sectioning:

- Snap-Freezing: Place fresh tissue in OCT-filled mold and orient correctly. Slowly submerge in chilled isopentane bath cooled by dry ice until opaque (10-20 seconds) [16]. Store frozen blocks at -80°C until sectioning.

- Cryosectioning: Equilibrate frozen block to cryostat temperature (-20°C) for 15-30 minutes [18] [16]. Cut sections at 5-8µm thickness and transfer to charged slides [16].

- Storage: Store slide-mounted sections at -80°C for up to several months [18].

Fixation and Permeabilization:

Blocking and Immunostaining:

- Blocking: Incubate sections with protein blocking solution (e.g., 5% normal serum) for 30-60 minutes at room temperature [16].

- Optional Blocks: For biotinylated antibodies, perform avidin/biotin blocking; for peroxidase systems, block endogenous peroxidase with 3% Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ [16].

- Primary Antibody: Apply optimized primary antibody dilution and incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C [16].

- Washing: Wash slides 3 times with wash buffer for 5 minutes each.

- Secondary Antibody: Apply fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody for 45-60 minutes at room temperature in the dark [16].

Mounting and Imaging:

Troubleshooting Common IHC Issues

Problem Identification and Resolution Strategies

The following workflow diagram outlines a systematic approach for diagnosing and resolving common IHC problems across both FFPE and frozen techniques:

Method-Specific Troubleshooting Guidelines

FFPE-Specific Issues:

- Epitope Masking: Optimize antigen retrieval by testing different buffers (citrate vs. Tris-EDTA), pH values, and heating methods [18] [17]. Extend retrieval time incrementally if staining remains weak.

- Over-fixation Artifacts: Standardize formalin fixation time to 18-24 hours; prolonged fixation increases cross-linking and requires more aggressive retrieval [17].

- Tissue Degradation: Ensure prompt tissue processing after collection; delays before fixation can cause nucleic acid degradation and protein cleavage [11].

Frozen Tissue-Specific Issues:

- Ice Crystal Damage: Ensure rapid "snap-freezing" using isopentane chilled by dry ice; slow freezing causes disruptive ice crystals [16] [17].

- Sectioning Difficulties: Allow proper block equilibration in cryostat (-20°C for 15-30 minutes); use anti-roll plates to prevent section curling [16].

- Antigen Loss: Limit post-sectioning fixation time; test different fixatives (acetone vs. PFA) for optimal antigen preservation [16].

The choice between FFPE and frozen tissue preservation is not merely a technical consideration but a strategic decision that influences research capabilities, data quality, and translational potential. FFPE tissues offer unparalleled advantages for morphological studies, retrospective research, and clinical applications where architectural context is paramount. Frozen tissues provide superior preservation of biomolecules in their native state, enabling advanced molecular analyses and functional studies. Contemporary research increasingly leverages both methods in complementary approaches, recognizing that the preservation protocol should be tailored to specific research questions rather than adhering to a universal standard.

For researchers developing IHC methods within tissue integration analysis projects, initial validation experiments should compare both preservation methods when feasible, particularly for uncharacterized antibodies or novel targets. As the field advances, improved antigen retrieval methods for FFPE tissues and standardized freezing protocols continue to narrow the performance gap. However, the fundamental trade-off between morphological integrity and molecular preservation remains, requiring informed decisions based on analytical priorities and practical constraints. By applying the structured comparison and detailed protocols presented in this application note, researchers can optimize their tissue preservation strategies to generate reliable, reproducible data that advances both basic science and drug development.

Antigen retrieval (AR) is a foundational technique in immunohistochemistry (IHC) that enables effective antibody binding by reversing the epitope masking caused by chemical fixation. In formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues—the standard for pathological diagnosis—formalin creates methylene bridges between proteins, leading to cross-linking that obscures antigenic sites and renders them inaccessible to antibodies [21] [22]. This process is critical because without AR, IHC staining can result in false negatives, weak signals, and unreliable data, particularly problematic for diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets like HER2 in breast cancer [22] [23].

The development of AR, particularly Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval (HIER), marked a revolutionary milestone, effectively dividing IHC for FFPE tissues into pre-AR and post-AR eras [24]. By breaking the formaldehyde-induced cross-links, AR restores the antigenicity of tissues, allowing researchers and clinicians to unlock the vast potential of archival FFPE tissue collections for both diagnostic pathology and translational research [24] [22]. This protocol outlines the principles and applications of AR, providing detailed methodologies to achieve consistent and robust staining results.

Principles of Antigen Retrieval

The Problem of Formalin Fixation

Formalin fixation preserves tissue architecture by creating protein cross-links; however, these methylene bridges sterically hinder antibody access to epitopes [21] [22]. This masking effect alters protein conformation and reduces antigen accessibility, leading to diminished immunoreactivity. The need for AR is particularly acute when using monoclonal antibodies, which target a single, specific epitope, compared to polyclonal antibodies that recognize multiple epitopes and may retain some binding capacity even after fixation [21].

Mechanisms of Unmasking

AR techniques primarily work by reversing the effects of formalin fixation. The exact mechanism is believed to involve the hydrolytic cleavage of the formaldehyde cross-links, the unfolding of epitopes, and the chelation of bound calcium ions [22] [25]. This process dissociates interfering proteins, exposes the antigenic sites, and allows the epitope to regain a conformation recognizable by the antibody [22].

Antigen Retrieval Methods

Two principal methods are employed for antigen retrieval: heat-induced and enzymatic. The choice between them depends on the target antigen, antibody, and tissue type.

Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval (HIER)

HIER is the most commonly used and generally effective method. It involves applying high heat to tissue sections in a specific retrieval buffer to break the cross-links [21] [22]. The key variables requiring optimization are:

- Buffer pH: Critical for success; citrate-based buffers (pH ~6.0) and Tris-EDTA buffers (pH ~9.0) are most common. The optimal pH is antigen-dependent [21] [25].

- Temperature: Effective retrieval typically requires temperatures between 90°C and 100°C [21].

- Incubation Time: Generally between 10-30 minutes, depending on the heating apparatus and tissue type [21].

Commonly used devices and their standard protocols are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of Common HIER Methods and Conditions

| Heating Apparatus | Typical Temperature | Typical Time | Advantages | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure Cooker [25] | Full pressure (~120°C) | 3 minutes after reaching pressure | Fast, even heating | Can be harsh on delicate tissues |

| Microwave [25] | 98-100°C | 20 minutes | Widely accessible | Risk of hot spots and uneven retrieval; slides must not dry out |

| Steamer/Rice Cooker [25] | 95-100°C | 20 minutes | Gentle boiling, less vigorous | Longer protocol |

| Water Bath [25] | 60-95°C | Overnight (60°C) or 20 min (95°C) | Gentle for fragile tissues | Very long incubation at lower temperatures |

Proteolytic-Induced Epitope Retrieval (PIER)

PIER uses proteolytic enzymes like trypsin, pepsin, or proteinase K to digest the cross-linked proteins and expose the epitopes [22] [26]. This method is typically employed when HIER is ineffective or when the antigen is known to be sensitive to heat. Optimization of PIER requires careful titration of:

- Enzyme Type: Selection based on the antigen and tissue.

- Enzyme Concentration: Too little is ineffective, too much damages tissue morphology.

- Incubation Time and Temperature: Typically 10-15 minutes at 37°C [22].

While useful, PIER has a lower success rate than HIER and carries a higher risk of damaging tissue morphology and the target antigen itself if over-digested [22].

Buffer Selection for HIER

The choice of retrieval buffer is antigen-specific and often requires empirical testing. The three most common buffers are:

- Sodium Citrate Buffer (10 mM, pH 6.0): A versatile, widely-used buffer for many antigens [25].

- Tris-EDTA Buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 9.0): Often preferred for nuclear antigens and more challenging targets [25].

- EDTA Buffer (1 mM, pH 8.0): Another high-pH alternative for difficult antigens [25].

Table 2: Common Antigen Retrieval Buffers and Their Applications

| Buffer | pH | Commonly Used For | Preparation Guide |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium Citrate | 6.0 | A broad range of cytoplasmic and membrane antigens | 2.94 g Tri-sodium citrate dihydrate in 1L dHâ‚‚O. Add 0.5 mL Tween 20 [25]. |

| Tris-EDTA | 9.0 | Nuclear antigens (e.g., Ki-67), phospho-epitopes, and more challenging targets | 1.21 g Tris base, 0.37 g EDTA in 1L dHâ‚‚O. Add 0.5 mL Tween 20 [25]. |

| EDTA | 8.0 | An alternative high-pH buffer for select antigens | 0.37 g EDTA in 1L dHâ‚‚O. Adjust pH with NaOH [25]. |

Advanced Applications and Integrated Workflows

The principles of AR extend beyond routine IHC, enabling advanced analytical techniques.

Quantitative IHC (qIHC)

Novel amplification systems now allow for precise protein quantification directly in FFPE tissues. One such method, qIHC, uses a known ratio of labeled-to-unlabeled secondary antibodies to generate countable dots, with each dot corresponding to a single antigen molecule [23]. This provides a sensitive, quantitative, and robust assay with a larger dynamic range and lower limit of detection than traditional IHC or ELISA, as demonstrated in accurate HER2 measurements [23].

Epitope Characterization for Antibody Discovery

Epitope binning is a critical step in therapeutic antibody development, grouping antibodies based on epitope similarities. High-throughput methods like Epitope Binning-seq use mammalian cell display and next-generation sequencing to simultaneously profile numerous query antibodies against a reference antibody without individual purification, dramatically accelerating candidate screening [27]. Complementary "dock binning" uses computational docking models to predict epitope regions, and combining these experimental and computational approaches provides a powerful strategy for localizing antigenic hotspots [28].

Integration with Mass Spectrometry Imaging (MSI)

Combining IHC with MSI overcomes throughput limitations. Antibodies conjugated to metal tags or organic mass tags can be simultaneously detected using mass spectrometry, enabling highly multiplexed imaging of dozens of proteins while preserving spatial context [29]. This integration of highly specific antibody binding with the multiplexing power of MSI is advancing biomarker discovery and spatial proteomics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Antigen Retrieval

| Item | Function/Description | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Antigen Retrieval Buffers | Solutions to break cross-links and expose epitopes. pH is critical. | Citrate (pH 6.0), Tris-EDTA (pH 9.0), EDTA (pH 8.0) [25]. |

| Proteolytic Enzymes | Enzymes for PIER to digest cross-linking proteins. | Trypsin, Pepsin, Proteinase K [22] [26]. |

| Heating Apparatus | Device for performing HIER under controlled conditions. | Pressure cooker, scientific microwave, vegetable steamer, water bath [25]. |

| Validated Primary Antibodies | Antibodies tested and validated for IHC on FFPE tissue. | Check manufacturer's datasheet for recommended AR conditions [21]. |

| Detection System | Visualization system, often enzyme-based (e.g., HRP). | Polymer-based systems for enhanced sensitivity and low background [26]. |

| Blocking Reagents | Reduce non-specific background staining. | Normal serum, BSA, or proprietary protein blocks [26]. |

| (E)-4,6-dichloro-2-styrylpyrimidine | (E)-4,6-dichloro-2-styrylpyrimidine, MF:C12H8Cl2N2, MW:251.11 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-Hydroxycanthin-6-one | 4-Hydroxycanthin-6-one, MF:C14H8N2O2, MW:236.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocol: Standard HIER Using a Pressure Cooker

This protocol provides a detailed step-by-step method for achieving robust and consistent antigen retrieval using a pressure cooker, a common and effective approach [25].

Materials and Reagents

- Tissue Sections: 4-5 µm thick FFPE sections mounted on slides.

- Antigen Retrieval Buffer: e.g., Tris-EDTA (pH 9.0) or Sodium Citrate (pH 6.0).

- Equipment: Domestic stainless steel pressure cooker, hot plate, slide rack, forceps.

- Staining Equipment: Access to an automated or manual IHC stainer for subsequent steps.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Deparaffinization and Rehydration:

- Deparaffinize slides by immersing in xylene (or substitute), 2 changes, 5 minutes each.

- Hydrate through graded ethanols: 100% (2x), 95%, 70%, 5 minutes each.

- Rise briefly in distilled water. Do not let sections dry out.

Heating and Retrieval:

- Add a sufficient volume of antigen retrieval buffer to the pressure cooker to cover slides by several centimeters. Place on the hot plate and begin heating, with the lid resting on top but not secured.

- Once the buffer is boiling, carefully transfer the rehydrated slides from the water into the slide rack within the pressure cooker.

- Secure the pressure cooker lid according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Once full pressure is reached, start timing and maintain pressure for 3 minutes [25].

Cooling:

- After 3 minutes, turn off the hotplate and move the pressure cooker to a sink.

- Activate the pressure release valve and run cold water over the cooker to depressurize and cool it.

- Once safe to open, remove the lid and run cold tap water into the cooker for 10 minutes to cool the slides and allow epitopes to re-form into a stable conformation [25].

Completion:

- Proceed with the standard IHC staining protocol, starting with blocking and application of the primary antibody.

Workflow and Data Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for selecting and optimizing an antigen retrieval method, integrating key factors from the protocols above.

Antigen retrieval is an indispensable technique for successful immunohistochemistry in FFPE tissues. While HIER is the preferred initial approach, the optimal protocol must be determined empirically for each antibody and tissue type. Mastery of AR principles and protocols ensures reliable, sensitive, and reproducible results, unlocking the full potential of archival tissue samples for diagnostic pathology, biomarker discovery, and therapeutic development. As IHC continues to evolve with quantitative methods and multiplexed imaging, robust antigen retrieval remains the critical first step in effective antibody binding.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is a foundational technique for tissue integration analysis research, enabling the visualization of protein distribution, subcellular localization, and abundance within a physiological context [6]. The specificity and reliability of any IHC experiment hinge on the appropriate selection of antibody reagents. An antibody is a blood protein produced in the immune system that specifically binds to a target antigen; a primary antibody binds directly to the target antigen of interest, while a secondary antibody binds to the primary antibody to facilitate detection [30] [31]. The selection process requires careful consideration of multiple interdependent factors to ensure specific, sensitive, and reproducible results, which is critical for researchers and drug development professionals relying on accurate tissue analysis data.

Core Considerations for Primary Antibody Selection

Understanding Your Target Protein and Antigen

A deep understanding of your target protein's biology is the first critical step in informed antibody selection. Key characteristics to consider include the protein's expression level, subcellular localization, structure, stability, homology to related proteins, and any post-translational modifications (PTMs) or involvement in upstream signaling events [32]. Consulting resources such as UniProt, the Human Protein Atlas, and literature databases provides valuable biological context [32].

The antibody must be raised against an immunogen (a specific region of the target antigen) for successful detection [30] [31]. The chosen immunogen defines which epitope the antibody recognizes. It is essential to verify that the immunogen sequence is contained within the region of the protein you are trying to detect, especially when working with protein isoforms or specific domains [31]. Furthermore, sample processing significantly impacts epitope recognition. Some antibodies only recognize proteins in their denatured state (e.g., for western blotting), while others require proteins in their native, folded conformation [30]. For IHC, fixation methods like formalin-induced cross-linking can mask epitopes, often necessitating an antigen retrieval step to reverse these cross-links and expose the binding site [30] [6].

Antibody Clonality: Monoclonal vs. Polyclonal

The clonality of an antibody—whether it is polyclonal or monoclonal—fundamentally affects its specificity, sensitivity, and consistency.

Table 1: Comparison of Polyclonal and Monoclonal Antibodies for IHC

| Feature | Polyclonal Antibodies | Monoclonal Antibodies |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Heterogeneous mixture from multiple B-cell clones [31] | Homogeneous population from a single B-cell clone [31] |

| Epitope Recognition | Multiple epitopes on the same antigen [30] [33] | Single, specific epitope [30] [33] |

| Sensitivity | Generally higher due to binding multiple epitopes [30] | Can be lower, but high-affinity clones exist |

| Specificity | Lower; potential for cross-reactivity with similar proteins [33] [31] | Higher; minimal cross-reactivity [33] [31] |

| Lot-to-Lot Variability | Higher [32] [31] | Very low [30] [32] |

| Tolerability to Antigen Conformation | Greater tolerability to fixation, pH, and temperature changes [30] | More sensitive to changes in protein conformation [33] |

| Ideal Use Case | Detecting low-abundance targets; native proteins [31] | Long-term projects; specific modification detection [33] |

A third category, recombinant antibodies, is produced using in vitro genetic engineering. Recombinant monoclonals offer the superior specificity of monoclonals combined with animal-free manufacturing, exceptional lot-to-lot consistency, and a scalable, secure supply [32] [31]. For the highest level of experimental reproducibility, recombinant monoclonal antibodies are recommended when a suitable clone is available [31].

Host Species and Isotype

The host species in which the primary antibody was raised has critical implications for experimental design, particularly when using a secondary antibody for detection [30] [32]. A fundamental rule is to choose a primary antibody host species that is different from the species of the tissue sample being tested [30]. For example, when studying a mouse tissue, select a rabbit-raised primary antibody instead of a mouse-raised one. This prevents the anti-mouse secondary antibody from binding to endogenous immunoglobulins in the mouse tissue, which causes non-specific background staining and false positives [32]. This "mouse-on-mouse" background can be addressed with specialized blocking kits, but the simplest solution is to choose a primary antibody from an alternate host species [30].

The antibody class or isotype (e.g., IgG, IgM) is also important because the secondary antibody must be directed against the specific class and subclass of the primary antibody, especially for monoclonal antibodies [30] [33]. This is crucial for multiplexed experiments where primary antibodies from the same host species but different subclasses are used with isotype-specific secondary antibodies.

Validation and Specificity

Antibody validation is the process of providing evidence that an antibody is specific and sensitive for its intended target and application. Given that validation in one application (e.g., western blot) does not guarantee performance in another (e.g., IHC), it is imperative to choose an antibody that has been specifically validated for use in IHC [32].

The most trusted method for confirming specificity is genetic validation using knockout (KO) controls [31] [34]. This involves testing the antibody on a cell line or tissue where the gene encoding the target protein has been inactivated. A specific antibody will produce a clear signal in the wild-type (control) sample and no signal in the isogenic KO sample [31]. The YCharOS initiative, a collaborative effort between academia and antibody manufacturers, has established a consensus platform using KO cell lines to systematically characterize antibody performance in common applications, providing openly accessible data to the research community [34]. When selecting an antibody, always check the datasheet for KO validation data and look for supporting images from IHC experiments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for IHC Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Primary Antibody | Binds specifically to the protein target of interest [30]. |

| Secondary Antibody (conjugated) | Binds to the primary antibody and carries a label (enzyme or fluorophore) for detection, providing signal amplification [31]. |

| Formalin/Paraformaldehyde Fixative | Preserves tissue integrity and morphology by creating protein cross-links; the most common fixative for IHC [6]. |

| Antigen Retrieval Buffer | Reverses cross-links introduced by formalin fixation to expose hidden epitopes, enabling antibody binding [30] [6]. |

| Blocking Serum | Reduces non-specific background staining by occupying reactive sites in the tissue before antibody incubation. |

| Chromogenic Substrate (e.g., DAB) | For enzyme-conjugated antibodies, produces an insoluble colored precipitate at the antigen site for brightfield microscopy [6]. |

| Fluorophore (e.g., CoraLite Plus dyes) | For fluorescent detection; emits light at a specific wavelength when excited, allowing visualization by fluorescence microscopy [6] [33]. |

| Mounting Medium with DAPI | Preserves the stained sample under a coverslip; DAPI is a dye that stains nuclear DNA, providing a cellular counterstain [6]. |

| Isotype Control | A non-immune immunoglobulin of the same species and isotype as the primary antibody; used to confirm specific binding via the Fab paratope [33]. |

| KO Cell Line or Tissue | Serves as a critical negative control to validate antibody specificity by confirming the absence of signal when the target is absent [31] [34]. |

| Thalidomide-O-C4-COOH | Thalidomide-O-C4-COOH|E3 Ligase Ligand-Linker Conjugate |

| Ethyl 3,3-dimethyl-4-nitrobutanoate | Ethyl 3,3-dimethyl-4-nitrobutanoate, MF:C8H15NO4, MW:189.21 g/mol |

Experimental Protocols for Antibody Validation in IHC

Protocol: Antibody Titration and Staining Optimization

Purpose: To determine the optimal dilution of a primary antibody for IHC that provides strong specific signal with minimal background.

- Sample Preparation: Cut consecutive sections from your FFPE (Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded) tissue block of interest. A positive control tissue known to express the target is ideal [33].

- Deparaffinization and Antigen Retrieval: Deparaffinize sections in xylene and rehydrate through a graded alcohol series. Perform antigen retrieval using the recommended method (e.g., heat-induced epitope retrieval in citrate or EDTA buffer) [6].

- Blocking: Block endogenous peroxidase activity (for chromogenic detection) and then incubate sections with a blocking serum (e.g., normal goat serum) to prevent non-specific binding.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Prepare a series of primary antibody dilutions. A good starting point is to test a range around the manufacturer's recommendation (e.g., 1:50, 1:100, 1:200, 1:500) [33]. Apply the different dilutions to consecutive tissue sections and incubate. The incubation can be performed for 1 hour at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. If background is high, shorter incubations at room temperature are recommended [33].

- Detection and Visualization: Incubate with the appropriate conjugated secondary antibody. For chromogenic detection, apply the enzyme substrate (e.g., DAB for HRP) and monitor color development. Counterstain with hematoxylin, dehydrate, and mount.

- Analysis: Examine the stained slides under a microscope. The optimal dilution is the one that yields the strongest specific staining with the cleanest background. If high background persists at all dilutions, consider further protocol adjustments like shorter incubation times or using F(ab')2 fragment secondary antibodies to avoid Fc receptor binding [33].

Protocol: Specificity Validation Using Knockout Controls

Purpose: To confirm the specificity of an antibody signal by comparing staining in wild-type versus knockout tissue.

- Source Control Tissues: Obtain matched tissue samples from a wild-type and a KO model (e.g., a CRISPR/Cas9-generated KO mouse) for your target protein [31]. The KO status must be confirmed at the protein level.

- Parallel Processing: Process both the wild-type and KO tissue samples identically and simultaneously: fix with the same fixative for the same duration, embed in paraffin, and section at the same thickness [34].

- Parallel Staining: Stain consecutive sections from both the wild-type and KO tissue blocks following the optimized IHC protocol from section 4.1, using the same antibody batch and dilution.

- Interpretation: A specific antibody will produce a clear, localized signal in the wild-type tissue and an absent or dramatically reduced signal in the KO tissue. Any signal remaining in the KO tissue is likely due to non-specific binding or cross-reactivity, indicating the antibody is not suitable for IHC without further validation [31] [34].

Decision Workflow and Visualization

The following diagram outlines the logical decision process for selecting a primary antibody for an IHC experiment, integrating the key considerations discussed in this note.

IHC Antibody Selection Workflow

A rigorous, hypothesis-driven approach to antibody selection is fundamental for generating reliable and meaningful IHC data in tissue integration research. By systematically considering the target antigen, choosing the appropriate clonality and host species, and insisting on application-specific validation—particularly with knockout controls—researchers can significantly enhance the specificity, sensitivity, and reproducibility of their experiments. Adopting these fundamentals and standardized protocols, as championed by community initiatives, will advance the quality of scientific discovery and drug development.

Step-by-Step IHC Protocols and Advanced Multiplex Staining Techniques

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is an indispensable technique in biomedical research and diagnostic pathology that allows for the specific visualization of target molecule distributions within tissue architecture without destroying histological context [35]. For researchers investigating tissue integration analysis, IHC provides critical insights into protein expression patterns, cellular localization, and pathological alterations within complex tissue environments. The unique capacity of IHC to preserve spatial relationships while detecting specific antigens makes it particularly valuable for drug development professionals studying disease mechanisms and therapeutic targets [35]. This application note provides a comprehensive protocol and framework for the complete IHC staining workflow, emphasizing standardization approaches essential for generating reliable, reproducible data in research settings.

The foundational principle of IHC relies on specific antigen-antibody reactions visualized through various detection systems [35]. When properly optimized, IHC enables researchers to confirm target molecule expressions within their native tissue microenvironment, providing crucial information that complements other molecular techniques. For scientists investigating tissue integration, this contextual preservation is paramount—it allows for the co-analysis of target molecules alongside their subcellular, cellular, and intercellular relations [35]. The following sections detail the complete workflow from tissue preparation through counterstaining, with specific attention to the technical considerations that ensure experimental success.

Materials and Methods

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful IHC requires carefully selected reagents at each procedural stage. The table below outlines essential materials and their functions within the IHC workflow.

Table 1: Essential Reagents for IHC Staining Workflow

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Fixatives | 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin (NBF), 4% paraformaldehyde with picric acid [36] | Preserves tissue architecture and antigenicity by preventing autolysis and degradation |

| Processing Reagents | Ethanol series (70%, 90%, 100%), Xylene, Paraffin [36] | Dehydrates, clears, and infiltrates tissue for microtomy sectioning |

| Antigen Retrieval Solutions | EDTA-based (pH 9.0), Citrate-based (pH 6.0) [37] [36] | Reverses formaldehyde-induced epitope masking through heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER) |

| Blocking Reagents | Normal serum, Bovine serum albumin (BSA), Protein blocking buffers [35] [36] | Reduces non-specific background staining by occupying hydrophobic binding sites |

| Primary Antibodies | Monoclonal (clone BP6165 [37]), Polyclonal [3] | Specifically binds to target antigen of interest with varying sensitivity and specificity |

| Detection System Components | Biotinylated secondary antibodies, Streptavidin-HRP, DAB chromogen [36] | Amplifies and visualizes primary antibody binding through enzymatic reactions |

| Counterstains | Mayer's Hematoxylin, DAPI, Methyl Green, Eosin [38] [39] [40] | Provides contrasting stain to visualize tissue morphology and context |

Complete IHC Staining Protocol

Tissue Preparation and Sectioning

Proper tissue preparation establishes the foundation for successful IHC staining. Ischemia time before fixation should be minimized as alteration in IHC results for biomarkers like Ki-67 has been reported with variable ischemic times [35].

Fixation: Immerse tissue in 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin (NBF) for 24 hours at room temperature with a tissue-to-fixative ratio between 1:1 to 1:20 [35]. For specialized applications, formaldehyde fixative solutions containing 4% paraformaldehyde with 14% saturated picric acid (pH 6.9) may be used to enhance morphology preservation [36]. Avoid fixation beyond 24 hours as this may mask or destroy tissue antigens [36].

Processing and Embedding: Dehydrate fixed tissues through a graded ethanol series (70%, 90%, 100%), clear in xylene, and infiltrate with molten paraffin at 58°C [36]. Proper dehydration is critical as paraffin is immiscible with water.

Sectioning: Cut tissue sections at 3-5 μm thickness using a rotary microtome [37] [35]. Float sections in a 56°C water bath and mount onto charged or gelatin-coated slides to enhance adhesion [3] [36]. Dry slides overnight at room temperature before storage or use.

Deparaffinization and Rehydration

Before IHC staining, paraffin-embedded sections must undergo deparaffinization and rehydration to enable aqueous-based reagents to penetrate the tissue.

- Immerse slides in xylene (mixed isomers) twice for 10 minutes each [36].

- Transfer through graded alcohols: 100% alcohol twice for 10 minutes, 95% alcohol for 5 minutes, 70% alcohol for 5 minutes, and 50% alcohol for 5 minutes [36].

- Rinse with deionized water and rehydrate in wash buffer (1X PBS) for 10 minutes [36].

Antigen Retrieval

Formaldehyde fixation creates methylene bridges that cross-link proteins and mask epitopes, necessitating antigen retrieval for many targets [35].

Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval (HIER): Incubate slides in preheated antigen retrieval solution (e.g., EDTA pH 9.0 or sodium citrate pH 6.0) using a heating device. Maintain at 100°C for 30 minutes on a heating plate, 10 minutes in a pressure cooker, or 8-15 minutes in a microwave oven [38] [35]. Allow slides to cool gradually to room temperature in the retrieval solution.

Enzymatic Retrieval: For limited antigens such as some cytokeratins, incubate sections with trypsin or proteinase K for 10-20 minutes at 37°C [35].

Immunostaining Procedure

The following protocol utilizes a chromogenic detection system with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and 3,3'-diaminobenzidine (DAB).

Endogenous Enzyme Blocking: Apply peroxidase blocking reagent (3% Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ in water or methanol) for 5-15 minutes to quench endogenous peroxidase activity [3] [36]. Rinse with wash buffer.

Protein Blocking: Apply serum blocking reagent (1-3% normal serum from the secondary antibody species or BSA) for 15 minutes to reduce non-specific background [35] [36]. Do not rinse after this step.

Primary Antibody Incubation: Apply optimized concentration of primary antibody diluted in incubation buffer (e.g., 1% BSA in PBS). Incubate overnight at 2-8°C in a humidified chamber [36]. For monoclonal antibody BP6165, a dilution of 1:200 for 30 minutes at room temperature has been successfully used [37].

Secondary Antibody and Detection: Incubate with biotinylated secondary antibody for 30-60 minutes, followed by High Sensitivity Streptavidin-HRP conjugate for 30 minutes [36]. Wash thoroughly between steps.

Chromogen Application: Apply DAB chromogen solution (prepared by mixing DAB concentrate with diluent at 1:20 ratio) for 3-20 minutes, monitoring development under a microscope [37] [36]. Terminate reaction by rinsing with wash buffer.

Counterstaining and Mounting

Counterstaining provides morphological context to the specific IHC signal.

Nuclear Counterstaining: For chromogenic IHC with DAB, apply Mayer's Hematoxylin for approximately 30 seconds [38] [39]. Rinse and immerse in bluing reagent (alkaline solution such as ammonia water or lithium carbonate) to convert nuclear color from red to blue/purple [41] [40].

Mounting: Dehydrate through graded alcohols (70%, 95%, 100%), clear in xylene, and coverslip using organic mounting media for DAB stains [36]. For AEC chromogen (red), use aqueous mounting media as AEC is alcohol-soluble [36].

The complete IHC staining workflow is visually summarized in the following diagram:

IHC staining workflow from tissue preparation to mounting

Results and Data Interpretation

Counterstain Selection and Applications

Appropriate counterstain selection is crucial for creating optimal contrast that allows the primary staining product to stand out while providing morphological context. The table below summarizes common counterstains and their applications.

Table 2: Counterstain Options for IHC Applications

| Counterstain | Target | Color | Staining Time | Compatible Chromogens | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mayer's Hematoxylin [38] [39] | Nuclei (binds to lysine residues on histones) | Blue to violet | 30 seconds [39] | DAB (brown), AEC (red) | Progressive stain; provides clear, sharp nuclear staining with little background [39] |

| Nuclear Fast Red [38] | Nucleic acids | Red | 5 minutes | DAB (brown), BCIP/NBT (blue) | Rapid staining; provides good contrast against blue, purple, brown, and green stains |

| Methyl Green [38] | Nucleic acids | Green | 5 minutes | DAB (brown), AEC (red) | Differentiates between DNA and RNA; excellent contrast against brown and red stains |

| Eosin [38] | Cytoplasm | Pink to red | 2-5 minutes | DAB (brown), Vector Blue | General cytosolic stain; acts as non-nuclear counterpart to hematoxylin |

| DAPI [38] [40] | Nucleic acids | Blue (fluorescent) | 5-15 minutes | Alexa Fluor dyes (488, 594, 647) | Less membrane permeable than Hoechst; typically used for fixed cells |

| Hoechst 33342 [38] | Nucleic acids | Blue (fluorescent) | 5-15 minutes | Alexa Fluor dyes | Membrane permeable; suitable for live or fixed cell applications |

| Propidium Iodide [38] | Nucleic acids | Red (fluorescent) | 5-15 minutes | FITC, Alexa Fluor 488 | DNA intercalating dye; ideal for experiments using green reporter labels |

Quality Control and Validation

Robust IHC requires systematic quality control measures to ensure result reliability and reproducibility. The following diagram illustrates the essential quality control framework:

Essential quality control components for validating IHC results

Controls fall into two primary categories: antigen (tissue) controls and reagent controls [41]. Positive controls consist of tissues with known expression of the target antigen, verifying that both procedure and reagents are functioning correctly even if test samples are negative [41]. Negative controls include tissues known not to express the target antigen, which check for non-specific signals and false-positive results [41]. Knockout tissues provide particularly robust negative controls, as demonstrated with TMEM119 knockout mouse brain tissue showing complete absence of staining [41].

Reagent controls are equally critical. The no-primary antibody control, where tissue is incubated with antibody diluent alone followed by secondary antibodies and detection reagents, ensures that observed staining results specifically from primary antibody binding rather than non-specific detection system interactions [41]. Isotype controls utilize non-immune antibodies of the same isotype and concentration as the primary antibody to identify non-specific antibody-tissue interactions [41]. For automated IHC systems, controls in liquid form (CLFs) prepared from genetically modified cell lines provide standardized quality assessment with regular circular shape and better cell distribution when applied automatically [37].

Troubleshooting Common IHC Issues

Even with optimized protocols, IHC experiments may encounter technical challenges that require systematic troubleshooting.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for Common IHC Problems

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Staining | Inadequate antigen retrieval, Primary antibody too dilute, Over-fixation, Improper epitope compatibility | Optimize HIER conditions (pH, time, temperature) [35]; Titrate primary antibody concentration [3]; Reduce fixation time; Verify antibody specification sheet for recommended protocols [3] |

| High Background Staining | Inadequate blocking, Endogenous enzyme activity not blocked, Primary antibody concentration too high, Non-specific antibody binding | Extend protein blocking time (30 min to overnight) [35]; Ensure complete peroxidase blocking (check erythrocytes as indicator) [3]; Titrate primary antibody; Use Fc receptor blocking for lymphoid tissues [35] |

| Uneven Staining | Section adhesion problems, Inconsistent washing, Concentration gradients during reagent application | Use charged slides instead of protein-based adhesives [3]; Standardize washing steps (duration, volume, agitation) [3]; Ensure even application of reagents across entire section [3] |

| Counterstain Too Strong | Hematoxylin concentration too high, Differentiation step omitted, Excessive counterstaining time | Regulate and standardize counterstain concentration and time [3]; For regressive hematoxylin, include differentiation in acid alcohol; Reduce counterstaining time, especially for nuclear antigens [41] |

| Tissue Morphology Damage | Excessive microwaving during HIER, Over-digestion with proteases, Section drying during procedure | Optimize HIER conditions to avoid "microwave burn" [35]; Titrate enzymatic retrieval concentration and time; Maintain tissue hydration throughout procedure |

Discussion

Advanced Applications in Tissue Integration Research

For researchers investigating tissue integration analysis, IHC offers several advanced applications that provide deeper insights into complex biological systems. Multiplex staining approaches enable the simultaneous detection of multiple antigens within the same tissue section, revealing cellular interactions and spatial relationships that single-marker staining cannot capture [42]. Both fluorescent and chromogenic multiplexing methods are available, each with distinct advantages. Fluorescent detection is particularly valuable for co-localization studies where targets occupy the same cellular compartments, as fluorophores with minimal spectral overlap can be distinguished even when precisely overlapping [42]. Chromogenic multiplexing with enzymes such as HRP (producing brown DAB precipitate) and AP (producing red Vector Red) allows visualization of multiple targets using standard brightfield microscopy [3].

When designing multiplex experiments, two key parameters must be considered: avoiding cross-reactivity between detection reagents and selecting fluorochromes or chromogens with minimal spectral overlap [41] [42]. This typically requires primary antibodies from different species to ensure secondary antibody specificity. For complex multiplex panels, species-specific secondary antibodies conjugated to distinct fluorophores (e.g., Alexa Fluor dyes with well-separated emission spectra) enable clear discrimination of multiple targets [41].

Recent technological advancements have significantly enhanced IHC capabilities for tissue integration research. Automated quantitative analysis methods based on deep learning techniques and image processing algorithms now enable precise identification and quantification of nuclear, membrane, and cytoplasmic expressions in whole-slide images [43]. These computational approaches employ optical density separation to differentiate between hematoxylin and DAB staining components, combined with advanced segmentation algorithms like CellViT for nuclear segmentation and region growing algorithms for membrane and cytoplasmic analysis [43]. Such automated systems achieve greater accuracy in specific quantitative metrics compared to traditional manual interpretation, providing robust tools for high-throughput tissue integration studies [43].

Standardization and Reproducibility Considerations