From Pixels to Predictions: Building Patient-Specific Finite Element Models from CT Scans for Advanced Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on generating patient-specific finite element (FE) models from CT scans.

From Pixels to Predictions: Building Patient-Specific Finite Element Models from CT Scans for Advanced Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on generating patient-specific finite element (FE) models from CT scans. We explore the foundational principles of translating medical imaging data into computational meshes, detail the core methodological pipeline from segmentation to solving, address common challenges and optimization strategies for accuracy and efficiency, and examine critical validation protocols and comparative analyses against alternative modeling approaches. The content synthesizes current best practices to empower the creation of high-fidelity, clinically relevant biomechanical models for personalized medicine and in silico trials.

The Building Blocks: Understanding How CT Scans Translate into Computational Models

Patient-Specific Finite Element Analysis (FEA) is a computational modeling technique that converts medical imaging data, such as CT scans, into precise, subject-specific digital models. These models simulate the physical behavior (e.g., stress, strain, flow) of biological tissues and medical devices under various physiological and pathological conditions. Within a thesis on model generation from CT scans, this approach is foundational for translating patient anatomy into a predictive, quantitative framework for research and clinical decision-making.

Application Notes & Protocols

Application 1: Pre-Clinical Assessment of Orthopedic Implants

Objective: To evaluate the biomechanical performance and risk of periprosthetic fracture for a cementless hip stem in a specific patient's femur.

Quantitative Data Summary: Table 1: Key Material Properties Assigned in Bone-Implant FEA

| Material / Tissue | Young's Modulus (MPa) | Poisson's Ratio | Property Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical Bone | 17000 | 0.3 | CT Hounsfield Unit (HU) calibration |

| Cancellous Bone | Variable (100-1500) | 0.3 | Site-specific HU calibration |

| Titanium Alloy (Implant) | 110000 | 0.3 | Manufacturer specification |

| Bone-Implant Interface | Frictional (µ=0.3) | - | Experimental literature |

Experimental Protocol:

- Image Acquisition: Acquire high-resolution (slice thickness ≤ 0.625 mm) CT scan of the patient's proximal femur.

- Segmentation & 3D Reconstruction: Use thresholding and region-growing algorithms in software (e.g., Mimics, 3D Slicer) to segment bony anatomy from soft tissue. Generate a 3D surface model (STL file).

- Mesh Generation: Import the surface model into FEA pre-processor (e.g., ANSYS, Abaqus). Apply a volumetric tetrahedral mesh, refining elements in regions of expected high stress gradients (e.g., calcar femorale, implant edges).

- Material Property Assignment: Establish a site-specific relationship between CT Hounsfield Units (HU) and bone elastic modulus (E) using a validated density-elasticity relationship (e.g., E = 2017 * ρ^1.64, where ρ is apparent density derived from HU).

- Boundary Conditions & Loading: Fix the distal end of the femur. Apply a joint reaction force (≈ 250% body weight) at the femoral head center, corresponding to the stance phase of gait.

- Solver Execution & Validation: Run the nonlinear static analysis. Validate model predictions by comparing strain patterns with published ex vivo digital image correlation (DIC) experimental data on instrumented cadaveric femurs.

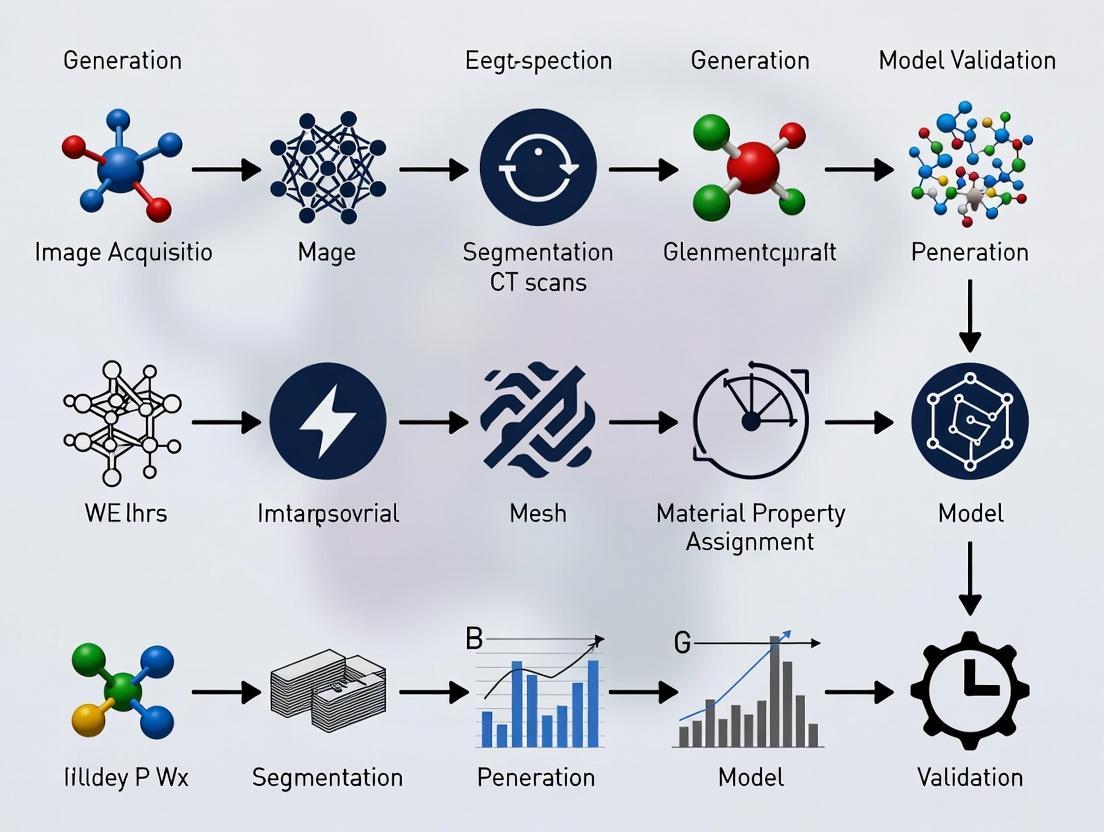

Diagram 1: Workflow for Patient-Specific Orthopedic FEA

Application 2: Drug Delivery & Aneurysm Hemodynamics

Objective: To model blood flow dynamics and drug (e.g., anti-thrombotic agent) residence time in a patient-specific cerebral aneurysm to assess treatment efficacy.

Quantitative Data Summary: Table 2: Parameters for Hemodynamic and Drug Transport FEA

| Parameter | Value / Description | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Blood Density | 1060 kg/m³ | Physiological constant |

| Blood Viscosity Model | Carreau non-Newtonian | Accounts for shear-thinning |

| Vessel Wall | Rigid (initial model) | Simplification for flow-focused study |

| Inlet Boundary Condition | Pulsatile Velocity Waveform | From phase-contrast MRI |

| Outlet Boundary Condition | Zero Pressure (or Windkessel) | Physiological outflow |

| Drug Diffusion Coefficient | 1e-10 m²/s | Molecular property of the agent |

Experimental Protocol:

- Angiography Imaging & Reconstruction: Obtain 3D rotational angiography (3DRA) or CTA data. Segment the lumen of the vasculature and aneurysm using level-set or model-based algorithms.

- Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Mesh: Generate a high-quality, boundary-layer-refined volumetric mesh (hexahedral or polyhedral) within the vascular geometry using CFD pre-processors (e.g., STAR-CCM+, SimVascular).

- Physiological Boundary Conditions: Map a representative pulsatile cardiac waveform to the inlet. Apply lumped parameter (Windkessel) models at outlets to mimic downstream vascular resistance and compliance.

- Flow & Drug Transport Simulation: Solve the Navier-Stokes equations for transient blood flow. Couple with a convection-diffusion equation to model passive scalar transport of the drug from the catheter release point.

- Post-Processing & Analysis: Quantify key hemodynamic indices (Wall Shear Stress, Oscillatory Shear Index) and drug residence time. Correlate low WSS and high residence time with regions of thrombus risk in clinical follow-ups.

Diagram 2: Multiphysics FEA for Aneurysm Drug Delivery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Patient-Specific FEA from CT

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose | Example (Not Exhaustive) |

|---|---|---|

| Medical Imaging Software | DICOM viewer, segmentation, 3D model creation. | 3D Slicer (open-source), Mimics (Materialise) |

| Image Segmentation Tools | Isolate anatomical regions of interest from scans. | ITK-SNAP (active contour), Simpleware ScanIP |

| Meshing Software | Converts 3D surface models into volumetric finite elements. | ANSYS Meshing, Gmsh (open-source), Simplexare FE |

| FEA/CFD Solver | Performs the core computational physics simulation. | Abaqus, ANSYS Mechanical/Fluent, FEBio (biomechanics) |

| Material Property Library | Provides empirical relationships for tissue mechanics (e.g., bone density-elasticity). | Published literature databases, bmtk (Biomechanics ToolKit) |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Provides computational power for solving large, nonlinear models. | Local clusters, cloud computing (AWS, Azure) |

| Validation Phantom | Physical model with known properties for model verification. | 3D-printed anatomical phantoms with compliant materials |

Computed Tomography (CT) is the foundational imaging modality for generating patient-specific finite element models. The accurate derivation of biomechanical properties hinges on a precise understanding of CT number fidelity (Hounsfield Units), spatial resolution, and artifact mitigation. This document outlines the critical principles and provides protocols for optimizing CT data acquisition for FEM generation in musculoskeletal and oncological research.

Core Principles & Quantitative Data

Hounsfield Units (HU): The Basis for Material Property Assignment

HU values are linearly related to the linear attenuation coefficient (μ) of tissues, calibrated against water and air. Accurate FEMs require stable and calibrated HU for tissue segmentation and density assignment.

Table 1: Standard Hounsfield Unit Ranges for Key Tissues

| Tissue / Material | Typical HU Range | Use in FEM Generation |

|---|---|---|

| Cortical Bone | 300 - 3000 | Assigns elastic modulus via density-power law relationships. |

| Trabecular Bone | 100 - 800 | Critical for modeling site-specific bone stiffness and failure. |

| Muscle | 10 - 40 | Defines soft tissue constraints and load distribution. |

| Fat | -150 to -50 | Differentiates mechanical properties from lean tissue. |

| Blood | 30 - 45 | Vascular modeling in tumor or organ FEMs. |

| Water (Reference) | 0 | Calibration standard. |

| Air (Reference) | -1000 | Calibration standard and cavity definition. |

Resolution: Spatial and Contrast

Resolution determines the geometric fidelity of the reconstructed 3D model.

Table 2: CT Resolution Metrics Impacting FEM Mesh Quality

| Metric | Typical Clinical Range | Impact on FEM |

|---|---|---|

| In-plane Spatial Resolution | 0.5 mm - 1.0 mm | Defines smallest discernible feature; limits element size. |

| Slice Thickness | 0.5 mm - 1.5 mm (isotropic preferred) | Affects z-axis accuracy; thicker slices cause staircase artifacts in 3D model. |

| Contrast Resolution (Low-contrast detectability) | < 5 HU difference | Critical for differentiating similar tissues (e.g., tumor vs. parenchyma). |

Artifacts: Threats to Model Accuracy

Artifacts introduce non-anatomical noise, corrupting geometry and density maps.

Table 3: Common CT Artifacts in FEM Context

| Artifact | Primary Cause | Consequence for FEM | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beam Hardening | Polychromatic X-ray spectrum | Cupping/streaking; inaccurate bone density/geometry. | Pre-patient filtration, calibration phantoms, iterative reconstruction. |

| Partial Volume | Voxel containing multiple tissues | Blurred interfaces, inaccurate HU at boundaries. | Use isotropic, high-resolution voxels (<0.5 mm). |

| Motion | Patient breathing, cardiac motion | Blurring, double contours, geometry errors. | Gating, fast acquisition, patient immobilization. |

| Metal | High-attenuation implants (e.g., prostheses) | Severe streaks, complete data loss. | Dual-energy CT, MAR algorithms, projection interpolation. |

| Scanner-specific Calibration Drift | Detector miscalibration | Global HU inaccuracy, corrupting density-power law. | Daily water phantom calibration. |

Application Notes & Protocols for FEM Research

Protocol A: Optimized CT Acquisition for Bone FEM Generation

Objective: Acquire CT data of a long bone (e.g., femur) for high-fidelity cortical and trabecular bone modeling. Materials: CT scanner (≥64 detector rows), calibration phantom (with known density inserts), immobilization devices.

Procedure:

- Phantom Scan: Prior to patient scanning, perform a daily quality assurance scan of a multi-material calibration phantom containing hydroxyapatite inserts (0-800 mg/cc).

- Patient Positioning: Immobilize the limb using a radiolucent support to eliminate motion.

- Acquisition Parameters:

- Voltage: 120 kVp (standardizes HU for bone).

- Tube Current: Use automated dose modulation (e.g., CARE Dose4D) with a quality reference mAs of 150-200.

- Rotation Time: ≤0.5 seconds.

- Pitch: ≤0.8 for overlapping reconstruction.

- Reconstruction Kernel: Use a "bone" or "sharp" kernel (e.g., B70s) to enhance edge detection.

- Field of View (FOV): Adjust to the limb only, maximizing matrix size.

- Reconstructed Slice Thickness: 0.5 mm, with 0.25 mm increment (isotropic voxels).

- Matrix: 512 x 512 (or 1024 x 1024 if available).

- Data Export: Export raw data (sinograms) and reconstructed images in DICOM format, ensuring HU integrity is preserved.

Protocol B: Mitigating Metal Artifacts for Implant-Tissue Interface Modeling

Objective: Acquire CT data of a pelvis with a metal hip implant for modeling bone-implant stress shielding. Materials: CT scanner with MAR software capability, gantry tilt functionality.

Procedure:

- Pre-Scan Planning: Use scout views to align the scan plane perpendicular to the long axis of the implant stem to minimize projected metal area.

- Acquisition Parameters:

- Voltage: Use high kVp (e.g., 140 kVp) to increase photon penetration.

- Tube Current: Increase substantially (e.g., 300-500 effective mAs) to improve signal-to-noise ratio.

- Pitch: Reduce to ≤0.6.

- Dual-Energy CT (if available): Acquire at 80/140 Sn kVp for virtual monoenergetic reconstructions and material decomposition.

- Reconstruction:

- Standard: Reconstruct images using the scanner's proprietary Metal Artifact Reduction (MAR) algorithm (e.g., SEMAR, iMAR).

- Dual-Energy: Generate virtual monoenergetic images at high keV (e.g., 140-190 keV) and material-specific images (water/calcium).

- Validation: Compare MAR-processed images to uncorrected images by measuring HU standard deviation in a region-of-interest adjacent to the implant.

Workflow for Patient-Specific FEM Generation from CT

Diagram Title: CT to FEM Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for CT-FEM Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| CT Calibration Phantom | Validates scanner HU linearity and provides density calibration for material property equations. | QCT Bone Mineral Density Phantom (Mindways) with hydroxyapatite inserts. |

| Anthropomorphic Phantom | Allows for protocol optimization and validation without patient exposure. | Pelvis or knee phantom with simulated cortical/trabecular bone and soft tissue. |

| Image Segmentation Software | Semi-automated segmentation of anatomical regions from CT DICOM data. | Mimics (Materialise), 3D Slicer (Open Source), Simpleware ScanIP (Synopsys). |

| Meshing Software | Converts segmented 3D surface models (.STL) into volumetric FE meshes. | ANSYS ICEM CFD, Gmsh (Open Source), Abaqus/CAE, Simpleware FE. |

| HU-Density-Elasticity Calibration Equations | Converts calibrated HU values to bone mineral density and elastic modulus for material assignment in FEM solver. | Rho = 1.067HU + 131 (mg/cc K2HPO4); E = c1(Rho)^c2 (c1, c2 from literature). |

| Finite Element Solver | Performs biomechanical simulation (stress, strain) on the generated model. | Abaqus (Dassault Systèmes), FEBio (Open Source), ANSYS Mechanical. |

Patient-specific finite element (FE) model generation from computed tomography (CT) scans is foundational for biomedical engineering applications, including surgical planning, implant design, and bone biomechanics research. The critical, value-determining step in this pipeline is image segmentation—the process of partitioning a digital image into distinct regions to isolate anatomical structures of interest. The fidelity of the subsequent 3D geometry and mesh directly dictates the accuracy of the FE simulation results. This document details application notes and protocols for the three predominant segmentation paradigms—manual, threshold-based, and AI-driven—within the context of generating biomechanically valid patient-specific bone models from clinical CT data.

Segmentation Methodologies: Protocols & Comparative Analysis

Manual Segmentation Protocol

Objective: To achieve expert-defined, high-precision segmentation of bone (e.g., femur, tibia) from clinical CT scans, serving as a "gold standard" for validating automated methods. Materials & Software: Clinical-grade workstation; DICOM viewer/segmentation software (e.g., 3D Slicer, Mimics); stylus/tablet (optional). Protocol:

- Data Import & Pre-processing: Import DICOM series into segmentation software. Confirm spatial calibration from metadata. Apply optional noise-reduction filters (e.g., Gaussian, median) if image quality is poor.

- Initial Mask Creation: Use a global threshold (e.g., 226–3071 HU for cortical bone) to create an initial, over-inclusive mask.

- Slice-by-Slice Correction: Navigate to each 2D axial slice. Manually refine the mask boundary using paint, erase, and interpolation tools to:

- Include trabecular bone and thin cortices.

- Exclude adjacent bones, calcifications, or metal artifacts.

- Ensure smooth, anatomically plausible contours.

- 3D Review & Edit: Generate a preliminary 3D model. Use clipping planes and rotation to inspect for topological errors (holes, spikes). Manually correct in 2D or 3D as needed.

- Export: Export the final segmentation as a binary label map and as a 3D surface mesh (STL format).

Threshold-Based (Semi-Automated) Segmentation Protocol

Objective: To efficiently segment bone using intensity-based techniques, often combined with morphological operations. Materials & Software: Image processing software (e.g., ImageJ, ITK-SNAP, Mimics). Protocol:

- Intensity Calibration: Ensure Hounsfield Unit (HU) calibration is applied. Segment based on known HU ranges for bone tissue.

- Global/Local Thresholding: Apply a threshold within the typical range for cortical bone. For better accuracy in heterogeneous regions, use adaptive local thresholding (e.g., Otsu's method per slice or region).

- Region of Interest (ROI) Definition: Manually draw a bounding region to separate the bone of interest from adjacent structures.

- Morphological Operations:

- Closing (dilation then erosion): To fill small holes within the bone.

- Opening (erosion then dilation): To remove small, isolated islands of noise.

- Apply 1-2 iterations with a 1-2 pixel spherical or cross kernel.

- Connected Component Analysis: Select the largest connected 3D component to isolate the target bone.

- Mask Smoothing: Apply a 3D median or Gaussian filter to the binary mask to reduce surface aliasing. Alternatively, apply smoothing directly to the subsequent mesh.

- Export: Export binary mask and STL file.

AI-Driven (Deep Learning) Segmentation Protocol

Objective: To automatically segment bone structures with high accuracy and reproducibility using a trained convolutional neural network (CNN). Materials & Software: GPU-equipped workstation; deep learning framework (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow); specialized software (e.g., MONAI, nnU-Net, commercial cloud services). Protocol:

- Model Selection/Preparation: Employ a state-of-the-art architecture like a 3D U-Net or its variants, pre-trained on medical imaging datasets if available.

- Data Preparation for Inference:

- Input: Resample the clinical CT volume to the isotropic resolution the model was trained on (e.g., 1.0 mm³).

- Normalization: Clip HU values to a relevant range (e.g., -200 to 1500 HU) and normalize to zero mean and unit variance.

- Patch-based Processing: For high-resolution volumes, use a sliding window approach if the model uses fixed-size patches.

- Inference: Feed the pre-processed volume through the trained network to obtain a probabilistic segmentation map.

- Post-processing: Apply a threshold (e.g., 0.5) to the probability map to create a binary mask. Perform standard morphological cleanup (closing, largest component selection).

- Export: Export final binary mask and STL file.

Quantitative Comparison of Segmentation Methodologies

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Segmentation Methodologies for Bone from CT

| Metric | Manual Segmentation | Threshold-Based | AI-Driven |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Basis | Expert anatomical knowledge | Pixel/voxel intensity (HU) | Learned hierarchical features |

| Time Investment | High (1–4 hours/bone) | Medium (10–30 minutes) | Low (< 2 minutes post-training) |

| Reproducibility | Low (Inter-operator variability ~5-15%) | Medium (Depends on parameter tuning) | High (Deterministic output) |

| Key Strength | Gold standard accuracy; handles complex cases | Simple, transparent, controllable | High speed & consistency; scalable |

| Key Limitation | Labor-intensive; subjective | Fails with poor contrast/artifacts | Requires large, labeled training set |

| Typical Dice Score* | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.85 – 0.94 | 0.92 – 0.98 |

| Role in FE Pipeline | Creating validation benchmarks | Rapid prototyping; educational use | Production-scale model generation |

*Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) compared to manual ground truth. Ranges from literature and typical results.

Integrated Workflow: From CT to FE Mesh

This diagram illustrates the logical progression from raw image data to a simulation-ready mesh, highlighting decision points for segmentation method selection.

Diagram Title: Segmentation-Driven FE Model Generation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents & Computational Tools for Segmentation & FE Modeling

| Item / Solution | Function / Role in Research |

|---|---|

| Clinical CT Dataset | Raw input data. Must have appropriate resolution (e.g., slice thickness < 1mm), contrast, and ethical approval for research use. |

| Manual Segmentation Software (e.g., 3D Slicer) | Provides interactive tools for expert contouring, serving as the platform for creating ground truth data. |

| Image Processing Library (e.g., SimpleITK, scikit-image) | Enables implementation of thresholding, filtering, and morphological operations for semi-automated pipelines. |

| Deep Learning Framework (e.g., PyTorch with MONAI) | Provides environment to develop, train, and deploy 3D CNN models for automated segmentation. |

| Labeled Training Dataset | Set of CT scans with expertly segmented bones (ground truth). Essential for training and validating AI models. |

| Mesh Generation Tool (e.g., CGAL, MeshLab, ANSYS ICEM CFD) | Converts binary masks to surface meshes and enables critical geometry repair, smoothing, and remeshing. |

| FE Meshing Software (e.g., ABAQUS, FEBio, ANSYS) | Generates volumetric (tetrahedral/hexahedral) meshes from surface geometry, assigns material properties, and defines boundary conditions. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Accelerates training of AI models and solves computationally intensive non-linear FE simulations. |

Experimental Protocol: Validation of Segmentation Accuracy for FE Modeling

Title: Protocol for Validating the Biomechanical Impact of Segmentation Method Choice. Objective: To quantify how errors from different segmentation methods propagate to errors in FE-predicted mechanical stress. Materials: One representative clinical CT scan of a proximal femur. Software for all three segmentation methods and an FE solver (e.g., FEBio). Procedure:

- Generate Ground Truth: Create a reference segmentation (

S_manual) using the Manual Protocol (2.1). Generate a high-quality surface mesh and volumetric FE mesh (M_manual). - Generate Test Models: Using the same CT scan, create segmentations via the Threshold Protocol (2.2) (

S_thresh) and AI Protocol (2.3) (S_ai). Generate corresponding FE meshes (M_thresh,M_ai). Ensure identical meshing parameters (element type, size) where possible. - Spatial Accuracy Metrics: Calculate Dice Score, Hausdorff Distance, and Mean Surface Distance between

S_thresh/S_aiand the referenceS_manual. - FE Simulation Setup: For all three models (

M_manual,M_thresh,M_ai):- Assign identical, homogeneous, linear elastic material properties (E=10 GPa, ν=0.3).

- Apply identical boundary conditions: fix distal end, apply a 2000N compressive load on the femoral head at 15° from vertical.

- Solve for von Mises stress and displacement fields.

- Biomechanical Error Analysis: In a standardized region of interest (e.g., femoral neck), compare peak von Mises stress and total displacement between

M_thresh/M_aiandM_manual. Calculate percentage error. - Analysis: Correlate spatial accuracy metrics (Step 3) with biomechanical error metrics (Step 5) to establish sensitivity.

Diagram Title: Segmentation Validation Experiment Flow

This document provides Application Notes and Protocols for the material property assignment phase within a broader thesis on Patient-specific finite element model (FEM) generation from CT scans. The accurate mapping of image intensity (grayscale) to biomechanical parameters is a critical step in creating clinically relevant computational models for surgical planning, implant design, and drug development (e.g., for osteoporosis).

Core Principles and Quantitative Relationships

The Hounsfield Unit (HU) from clinical CT scans is the primary grayscale metric. It is linearly related to the apparent density (ρ_app) of tissues. For bone, this density is then non-linearly converted to elastic modulus (E) and other mechanical properties.

Table 1: Standard Grayscale-to-Property Relationships for Musculoskeletal Tissues

| Tissue Type | CT Hounsfield Unit (HU) Range | Apparent Density ρ_app (g/cm³) | Elastic Modulus E (MPa) | Primary Empirical Relationship (Source) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical Bone | > 600 | 1.8 - 2.0 | 12,000 - 20,000 | E = 10,500 * ρ_app^2.29 (Rho et al., 1995) |

| Trabecular Bone | 100 - 600 | 0.2 - 1.0 | 50 - 2000 | E = 2,349 * ρ_app^1.57 (Morgan et al., 2003) |

| Fatty Marrow | -150 to -50 | ~0.93 | ~1 | Often modeled as a nearly incompressible fluid. |

| Muscle | 40 - 100 | ~1.06 | ~0.1 - 0.5 | Often modeled as a hyperelastic material (Mooney-Rivlin). |

| Cartilage | Not directly visible | 1.0 - 1.2 | 5 - 15 | Requires specialized sequences (μCT, MRI) for mapping. |

Table 2: Key Calibration Parameters for QCT-Based Finite Element Analysis (FEA)

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Value/Function | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calibration Phantom Density | ρ_phantom | 0, 50, 200 mg/cc K₂HPO₄ | Converts HU to equivalent mineral density. |

| Density-Modulus Coefficient | C | 2,349 - 10,500 | Material-specific constant from regression. |

| Density-Modulus Exponent | m | 1.57 - 2.29 | Material-specific exponent from regression. |

| Poisson's Ratio (Bone) | ν | 0.3 - 0.4 | Often assumed constant due to low sensitivity. |

| Yield Stress Exponent | b | ~1.7 | Used in plasticity models: σy = Cy * ρ^b. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Calibration of CT Scanner for Bone Mineral Density (BMD)

Objective: To establish a linear relationship between Hounsfield Units (HU) and equivalent bone mineral density (BMD) using a phantom.

- Preparation: Place a calibrated reference phantom (e.g., Mindways QCT phantom, European Spine Phantom) containing known concentrations of hydroxyapatite (HA) or K₂HPO₄ in the scanner field of view with the subject.

- Scanning: Acquire the CT scan using a standardized clinical protocol (e.g., 120 kVp, slice thickness ≤ 1.5 mm).

- ROI Sampling: In the reconstructed image, define Regions of Interest (ROIs) within each insert of the phantom.

- Data Extraction: Record the mean HU value for each ROI.

- Calibration Curve: Plot known insert density (mg HA/cc) versus measured mean HU. Perform linear regression:

HU = a * BMD + b. The coefficientsa(slope) andb(intercept) are scanner-specific.

Protocol 3.2: Direct Mechanical Testing for Validation

Objective: To empirically derive and validate the density-modulus relationship for a specific bone type (e.g., human femoral trabecular bone).

- Specimen Extraction: Obtain cylindrical bone cores (e.g., Ø 8mm, height 12mm) from cadaveric donors, ensuring alignment with principal trabecular orientation.

- Micro-CT Scanning: Scan each specimen using a high-resolution micro-CT scanner (voxel size ~20-30μm). Calculate the mean bone volume fraction (BV/TV) and apparent density (ρ_app = BV/TV * 1.92 g/cm³).

- Mechanical Testing: Perform unconfined, uniaxial compression test on a materials testing system at a quasi-static strain rate (0.005 s⁻¹). Extract the apparent elastic modulus (E) from the linear region of the stress-strain curve.

- Empirical Fitting: For the set of specimens, perform a power-law regression:

E = C * ρ_app^m. Document the coefficients C, m, and the coefficient of determination (R²).

Protocol 3.3: Implementation in Finite Element Software (Abaqus Python Script)

Objective: To automate the assignment of heterogeneous material properties to a meshed bone geometry from a registered CT scan.

- Input: A meshed bone geometry (e.g., .inp file) and its corresponding calibrated CT scan volume.

- Registration: Spatially register the mesh nodal/element coordinates to the CT image coordinates using an affine transformation.

- Mapping Algorithm:

a. For each element, find its centroid in image space.

b. Sample the calibrated HU value from the CT volume at that location (using trilinear interpolation).

c. Convert HU to BMD using the calibration curve from Protocol 3.1:

BMD = (HU - b) / a. d. Convert BMD to apparent densityρ_app(may require tissue-specific scaling). e. Calculate elastic modulus:E = C * ρ_app^m. - Output: Generate an Abaqus input file with material assignments (

*ELASTIC) defined per element or per element set based on density.

Diagrams

Title: Workflow for Patient-Specific FE Model Generation from CT

Title: Material Property Mapping Pathway for Bone

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Mapping Validation

| Item/Category | Function & Rationale | Example/Details |

|---|---|---|

| Calibration Phantom | Converts scanner-specific HU to standardized mineral density. Critical for multi-site studies. | Mindways QCT Phantom, European Spine Phantom (ESP). |

| Cadaveric Tissue Specimens | Provide gold-standard biological material for deriving and validating empirical relationships. | Human femoral/tibial heads, vertebral bodies. Stored at -20°C. |

| Micro-CT Scanner | Provides high-resolution 3D images for calculating precise bone morphology and apparent density of test specimens. | Scanco μCT 50, Bruker Skyscan 1272. |

| Materials Testing System | Empirically measures mechanical properties (E, σ_y) of tissue specimens under controlled loading. | Instron 5944, Bose ElectroForce. Requires small-load cells. |

| Image Segmentation Software | Isolates the tissue of interest (e.g., bone) from the surrounding anatomy in the CT scan. | Mimics, Simpleware ScanIP, ITK-SNAP (open source). |

| FE Solver with Scripting API | Enables automated, voxel-based assignment of heterogeneous material properties. | Abaqus (Python), FEBio (Python/C++), ANSYS (APDL). |

| Spectral CT Scanner (Emerging) | Provides multi-energy data to decompose materials (e.g., calcium, water, fat), improving specificity beyond HU. | Philips IQon, Siemens Dual Source CT. |

The generation of patient-specific finite element (FE) models from CT scans is a cornerstone of computational biomechanics in biomedical research. This process, critical for advancing personalized medicine, surgical planning, and medical device/drug development, relies on a multi-stage pipeline. Each stage is supported by specialized software tools and platforms, ranging from open-source to commercial. This note details the current landscape, providing application protocols and a comparative analysis of key platforms within the context of a thesis on automating and validating patient-specific FE model generation.

Comparative Analysis of Core Software Platforms

The following table summarizes the primary tools used across the standard pipeline of Image Segmentation → Geometry Reconstruction → Meshing → FE Solving → Post-processing.

Table 1: Core Software Tools in the Patient-Specific FE Modeling Pipeline

| Software | Type | Primary Role in Pipeline | Key Strength | Typical Application in Thesis Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D Slicer | Open-Source | Image Segmentation, Initial 3D Reconstruction | Extensible platform with vast module library (e.g., Segment Editor), excellent for clinical image data. | Semi-automatic segmentation of bony structures/soft tissue from clinical CT; initial STL surface generation. |

| SimVascular | Open-Source | Cardiovascular-specific Pipeline: Segmentation to Simulation. | Integrated workflow for blood flow (CFD) and FSI; patient-specific hemodynamics. | Generating subject-specific aortic or coronary models for vascular biomechanics studies. |

| FEBio | Open-Source | FE Solver & Pre/Post-processing (FEBio Studio). | Specialized in nonlinear, quasi-static biomechanics (contact, materials like Mooney-Rivlin). | Solving soft tissue mechanics, bone-implant interaction, cartilage contact. |

| Abaqus/CAE | Commercial | Integrated Pre-processing, FE Solver, Post-processing. | Robust, high-performance solver; advanced material models and element types; scripting via Python. | Gold-standard validation of simpler models; complex multi-physics or large-deformation problems. |

| MeshLab | Open-Source | Geometry Processing & Lightweight Meshing. | Cleaning, simplifying, and repairing surface meshes from segmented STLs. | Preparing watertight geometry for volume meshing. |

| Gmsh | Open-Source | Automatic 3D Volume Meshing. | Scriptable (via .geo) for parameterized, high-quality tetrahedral mesh generation. | Creating the volumetric FE mesh from cleaned surface geometry; mesh sensitivity studies. |

| Python (VTK, PyVista, scikit-image) | Open-Source Libraries | Custom Scripting & Pipeline Automation. | Full control to automate steps between platforms; develop custom algorithms. | Bridging tools (e.g., Slicer→Gmsh→FEBio); batch processing; developing novel segmentation/meshing methods. |

Application Notes & Protocols

Protocol 1: Generation of a Patient-Specific Tibial Bone FE Model from CT for Implant Analysis

Objective: Create a FE model of a human tibia from a clinical CT scan to analyze strain distributions under load.

Workflow Diagram:

Diagram Title: Workflow for Patient-Specific Tibia FE Model Generation

Detailed Methodology:

- Image Segmentation (3D Slicer):

- Load DICOM series into 3D Slicer.

- Use the Segment Editor module. Apply a

Thresholdtool (range ~250-3000 HU) to isolate cortical and cancellous bone. - Use

PaintandErasetools for manual correction. ApplyIslandstool to remove disconnected voxels. - Use the

Smoothing(Median) filter to reduce pixelation. Export segmentation as a binary labelmap.

Surface Mesh Generation (3D Slicer):

- Use the Model Maker module. Input: labelmap from Step 1.

- Parameters: use

Smoothingon,Decimateto 0.5 to reduce triangle count. Output: surface mesh as an STL file.

Geometry Cleaning (MeshLab):

- Import STL. Apply

Filters → Cleaning and Repairing → Remove Duplicate Vertices. - Apply

Filters → Cleaning and Repairing → Remove Isolated Pieces (wrt diameter)to remove tiny artifacts. - Export cleaned, watertight STL.

- Import STL. Apply

Volumetric Meshing (Gmsh):

- Write a

.geoscript to: a) import the cleaned STL, b) create aSurface LoopandVolume, c) define a meshing size field (finer at surfaces), d) generate a 3D tetrahedral mesh. - Command line:

gmsh -3 tibia_model.geo -o tibia_mesh.inp. Export format: Abaqus INP or FEBio XML.

- Write a

Material Assignment & FE Setup (FEBio Studio/Python):

- Import mesh into FEBio Studio. Assign a linear elastic material model.

- For homogeneous model: Use literature values (E=17 GPa, ν=0.3 for cortical bone).

- For heterogeneous model: Use a Python script to map CT Hounsfield Units (HU) in the original DICOM to element elastic moduli using an empirical relationship (e.g., E = a * ρ^b, where ρ is density derived from HU), and assign material IDs accordingly.

- Apply boundary conditions: Fix distal end. Apply a compressive load (~700N) distributed on the proximal plateau.

Solving & Post-processing (FEBio):

- Run the solver (

febio2 -i tibia_model.feb). - Visualize results (stress, strain, displacement) in FEBio Studio. Quantify peak von Mises stress in regions of interest.

- Run the solver (

Protocol 2: Patient-Specific Aortic Hemodynamics Simulation with SimVascular

Objective: Simulate blood flow in a patient-specific aorta to assess wall shear stress (WSS), a biomarker relevant in vascular drug delivery studies.

Workflow Diagram:

Diagram Title: SimVascular Pipeline for Aortic Hemodynamics

Detailed Methodology:

- Image Import & Path Planning (SimVascular):

- Import DICOM series. Use the Path Planning tool to manually place seeds at the aortic root and descending aorta to generate a centerline path.

Segmentation & Modeling (SimVascular):

- In the Segmentations module, use the

Level Setmethod along the path to grow the lumen contour. Adjust parameters (e.g., curvature, propagation scaling) to fit the image boundaries. - Create lofted surface from segmentations to generate a smooth, tubular surface model.

- In the Segmentations module, use the

Model Preparation & Meshing (SimVascular):

- Use the Model module to cap the inlets/outlets.

- Use the Mesh module to generate a boundary layer mesh. Set global edge size (~0.6 mm) and boundary layer parameters (3-5 layers, thickness ~0.3 mm). Run the TetGen-based mesher.

Solver Setup (SimVascular):

- In the Simulations module, select the

svSolver(incompressible Navier-Stokes). - Assign boundary conditions: Inlet - prescribed flow waveform (from literature or PC-MRI); Outlets - use a 3-element Windkessel (RCR) model for resistance and compliance.

- Set fluid properties: density = 1060 kg/m³, viscosity = 0.04 Poise.

- In the Simulations module, select the

Running & Post-processing:

- Run the simulation on a local cluster or workstation. SimVascular produces results in VTK format.

- Visualize and quantify time-averaged WSS (TAWSS), oscillatory shear index (OSI) in Paraview (open-source) using built-in calculators and streamtracers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials & Digital "Reagents" for Patient-Specific FE Modeling

| Item | Category | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical CT/MRI DICOM Datasets | Input Data | The raw material. Public repositories (e.g., The Cancer Imaging Archive - TCIA) or institutional PACS provide patient-specific anatomical geometry. |

| Segment Editor Module (3D Slicer) | Software Module | The "digestion enzyme" for images. Provides thresholding, region-growing, and AI-assisted tools to isolate tissues of interest from medical images. |

| TetGen (via Gmsh/SimVascular) | Meshing Algorithm | The "scaffold builder." Converts smooth surfaces into a tetrahedral volumetric mesh suitable for FE/CFD analysis. |

| FEBio's Mooney-Rivlin Material Model | Constitutive Model | The "biochemical" for soft tissue. Defines the nonlinear, nearly incompressible stress-strain behavior of materials like arterial wall or cartilage. |

| Python Scripts (NumPy, SciPy, pyFEBio) | Automation Tool | The "robotic pipettor." Automates repetitive tasks, connects software tools, and implements custom material mapping or batch processing pipelines. |

| Abaqus Python Scripting Interface | Commercial API | Enables programmatic control of Abaqus/CAE for validation studies, complex model generation, and design of experiments. |

| Paraview | Visualization Software | The "microscope" for results. Enables advanced visualization, quantitative analysis, and generation of publication-quality figures from simulation data. |

Step-by-Step Pipeline: A Practical Guide to Generating Your FE Model from DICOM Data

Within the research pipeline for generating patient-specific finite element (FE) models from CT scans, the initial step of image acquisition and pre-processing is foundational. The accuracy of subsequent segmentation, geometry reconstruction, and ultimately, the biomechanical predictions of the FE model, is critically dependent on the quality and consistency of the input CT data. This protocol details the acquisition parameters and pre-processing methods—specifically noise reduction and image alignment/registration—required to ensure standardized, high-fidelity input for automated model generation.

CT Acquisition Protocol for FE Modeling

A standardized acquisition protocol is essential to minimize variability. Key parameters are summarized below.

Table 1: Recommended CT Acquisition Parameters for Patient-Specific FE Modeling

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Rationale for FE Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Voltage (kVp) | 120-140 kVp | Optimal for bone mineral density (BMD) calibration and soft tissue contrast. |

| Tube Current (mA) | ≥200 mA (Dose modulated) | Balances low image noise with ALARA radiation dose principles. |

| Slice Thickness | ≤0.625 mm (isotropic voxels target) | Essential for high-resolution 3D reconstruction and accurate geometry capture. |

| Reconstruction Kernel | Bone/Sharp (for geometry) & Soft/Standard (for tissue) | Dual reconstruction may be necessary: sharp for edges, standard for noise. |

| Field of View (FOV) | Minimal to encompass anatomy of interest | Maximizes in-plane resolution; critical for small anatomical features. |

| Gantry Tilt | 0° | Simplifies subsequent registration and alignment steps. |

Pre-processing: Noise Reduction (Denoising)

Raw CT images contain quantum noise that can adversely affect automatic segmentation and material property assignment. Denoising must preserve edges critical for geometry definition.

Experimental Protocol: Non-Local Means (NLM) Denoising

Objective: To reduce noise while preserving anatomical edges for segmentation.

Software: Open-source (e.g., 3D Slicer with Simple Filters module) or commercial (e.g., Mimics).

Input: Original DICOM series (e.g., CT_Original).

Steps:

- Load Data: Import DICOM series into pre-processing software.

- Parameter Calibration:

- Set search radius to 3-5 voxels.

- Set comparison window to 1-2 voxels.

- Adjust smoothing parameter (h) iteratively. Start at

h = 0.1 * standard deviation of image noise.

- Application: Apply the 3D NLM filter to the entire volume.

- Output: Save denoised volume (e.g.,

CT_Denoised_NLM). - Validation:

- Calculate Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) and Contrast-to-Noise Ratio (CNR) in homogeneous regions (e.g., muscle) and at bone-soft tissue interfaces before and after.

- Visually inspect edge sharpness.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Denoising Algorithms for FE Modeling

| Algorithm | Primary Mechanism | SNR Improvement | Edge Preservation | Suitability for FE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Filter | Linear smoothing | High | Poor | Low - over-smoothes edges. |

| Median Filter | Non-linear, rank-based | Moderate | Good | Moderate for soft tissue. |

| Non-Local Means (NLM) | Patch-based similarity | High | Excellent | High - optimal balance. |

| Deep Learning (CNN-based) | Learned from data | Very High | Excellent | High - requires trained model. |

Pre-processing: Alignment (Registration)

For longitudinal studies or multi-modal fusion (e.g., CT with pre-op MRI), precise spatial alignment is required to establish a consistent coordinate system for the FE model.

Experimental Protocol: Rigid Registration to a Reference Atlas

Objective: To align a subject's CT scan (Moving Image) to a standard anatomical atlas or baseline scan (Fixed Image).

Software: 3D Slicer (General Registration (BRAINS) module) or Elastix.

Input: CT_Denoised (Moving), Atlas_CT (Fixed).

Steps:

- Initialization: Use manual or landmark-based initialization for coarse alignment.

- Metric Selection: Select Mean Squares for mono-modal (CT-to-CT) registration.

- Optimizer: Use Regular Step Gradient Descent.

- Parameters: Gradient Magnitude Tolerance

1e-4, Min/Max Step0.001/4.0, Iterations500.

- Parameters: Gradient Magnitude Tolerance

- Interpolator: Use Linear Interpolation for final resampling.

- Execution: Run the multi-resolution registration (typically 3 levels).

- Output: Save the transformed

Aligned_CTvolume and the transformation matrix (transform.tfm). - Validation: Calculate the Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) of a segmented bone (e.g., femur) between the aligned image and the atlas. Target DSC > 0.90.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item | Function in CT Pre-processing for FE | Example Product/Software |

|---|---|---|

| Phantom for Calibration | Converts CT Hounsfield Units (HU) to bone mineral density (BMD) for FE material properties. | QRM-BDC, Mindways Calibration Phantom |

| Denoising Algorithm Library | Provides state-of-the-art filters for image quality improvement. | ITK (Insight Toolkit), PyTorch for DL models |

| Registration Toolbox | Performs spatial alignment of image volumes. | Elastix, ANTs, 3D Slicer BRAINS |

| DICOM Viewer/Processor | Core platform for viewing, processing, and scripting the workflow. | 3D Slicer, MITK, Horos |

| High-Performance Workstation | Enables processing of high-resolution 3D volumes with GPU acceleration. | NVIDIA GPU (e.g., RTX A5000), 64GB+ RAM |

Visualization of Workflows

Title: CT Image Pre-processing Workflow for FE Model Generation

Title: Detailed Denoising and Alignment Experimental Protocols

Within patient-specific finite element model (FEM) generation from CT scans, anatomical segmentation is the critical step that transforms raw imaging data into distinct, label-specific volumetric masks. This step defines the geometry and material assignment domains for subsequent meshing and biomechanical simulation. Accurate segmentation of bone, soft tissue, and vasculature is paramount for generating models that reliably predict biomechanical behavior, implant performance, or drug delivery dynamics.

Key Segmentation Techniques

Thresholding & Region-Based Methods

Protocol: Multi-Threshold Otsu Segmentation for Bone

- Objective: Isolate cortical and trabecular bone from a clinical CT scan (e.g., femoral head).

- Materials: DICOM CT series (slice thickness ≤ 1.0 mm), ITK-SNAP or 3D Slicer software.

- Methodology:

- Preprocessing: Apply a non-local means filter to reduce noise while preserving edges.

- Global Thresholding: Use the Otsu multi-threshold algorithm to automatically identify up to three intensity clusters corresponding to background, soft tissue/marrow, and bone.

- Morphological Operations: Perform a 3D closing (dilation followed by erosion) with a spherical structuring element (radius=1 voxel) to smooth the bone mask and fill small voids.

- Connected Component Analysis: Retain the largest 3D connected component to eliminate isolated noise.

- Validation: Compare segmented volume against manual segmentation by an expert radiologist using Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC).

Atlas & Multi-Atlas Label Fusion (MALF)

Protocol: Whole-Pelvis Segmentation for Pre-operative Planning

- Objective: Segment pelvis, femur, and major muscle groups from a preoperative CT.

- Materials: Target patient CT, a curated atlas library of 30-50 manually segmented CT scans, Elastix or ANTs software for registration.

- Methodology:

- Atlas Library Preparation: Ensure all atlas images are isotropically resampled and aligned to a common coordinate system (e.g., based on anatomical landmarks).

- Target Preprocessing: Normalize the target scan's intensity histogram to match the atlas population.

- Deformable Registration: Non-rigidly register each atlas to the target scan using a B-spline transformation model with mutual information as the similarity metric.

- Label Fusion: Apply the resulting deformation fields to atlas labels. Use a locally weighted voting scheme (e.g., Local Weighted Voting) to fuse the propagated labels into a final consensus segmentation for each structure.

- Post-processing: Apply structure-specific logical rules (e.g., femur cannot intersect pelvis) to refine labels.

Deep Learning-Based Segmentation (U-Net & Variants)

Protocol: nnU-Net for Automatic Segmentation of Vasculature and Soft Tissue

- Objective: Segment the abdominal aorta, iliac arteries, and surrounding fat/muscle from contrast-enhanced CT angiography (CTA).

- Materials: Annotated CTA dataset (~100 scans), NVIDIA GPU (≥8GB VRAM), PyTorch, nnU-Net framework.

- Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Split data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets. nnU-Net automatically configures preprocessing (resampling to median voxel spacing, intensity normalization via z-scoring).

- Network Training: Train a 3D full-resolution U-Net with deep supervision. Use a combination of Dice and cross-entropy loss. Employ on-the-fly data augmentation (rotation, scaling, Gaussian noise).

- Inference: Apply the trained model to unseen test scans. Use a sliding window approach with overlap-tile strategy to handle large volumes.

- Post-processing: Apply a 3D connected components analysis to remove predicted voxel clusters below a physiologically plausible volume threshold.

Level Set & Active Contour Methods

Protocol: Level Set Segmentation of the Left Ventricle Myocardium

- Objective: Accurately segment the dynamic myocardium wall from 4D cardiac CT data.

- Materials: 4D Cardiac CT scan, SimpleITK or MITK software.

- Methodology:

- Initialization: Manually or automatically place a seed sphere within the ventricular blood pool in the first time frame.

- Evolution: Implement a geodesic active contour level set function. The speed function is governed by image gradients (to stop at edges) and regional intensity statistics (to leverage intensity homogeneity inside the chamber).

- Temporal Propagation: Use the final contour of frame t as the initialization for frame t+1 to track the myocardial boundary through the cardiac cycle.

- Constraint: Incorporate a penalty term to maintain a consistent wall thickness within physiological bounds.

Quantitative Comparison of Segmentation Techniques

Table 1: Performance and Application Suitability of Segmentation Techniques in Patient-Specific FEM Generation

| Technique | Typical Dice Score (Reported Range) | Speed | Primary Application in FEM Context | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thresholding | Bone: 0.92-0.97 | Very Fast | Initial bone mask extraction; creating density-based maps. | Simple, computationally inexpensive. | Fails with intensity overlap (e.g., bone/contrast). |

| Atlas-Based (MALF) | Complex Structures: 0.85-0.92 | Slow (Registration) | Segmenting multiple anatomical structures simultaneously. | Robust for structures with consistent topology. | Performance degrades with high anatomical variation. |

| Deep Learning (3D U-Net) | Vasculature: 0.88-0.94; Soft Tissue: 0.86-0.91 | Fast (after training) | High-throughput, automatic segmentation of all tissue types. | State-of-the-art accuracy; learns complex features. | Requires large, high-quality annotated datasets. |

| Level Sets | Myocardium: 0.85-0.90 | Medium | Refining boundaries of smooth structures; tracking deformation. | Provides smooth, closed surfaces; can handle topology changes. | Sensitive to initialization; may leak through weak edges. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software Tools for Anatomical Segmentation in FEM Research

| Item (Software/Package) | Primary Function | Application in Segmentation Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| 3D Slicer | Open-source platform for medical image informatics, visualization, and analysis. | Interactive manual correction, multi-atlas segmentation, and result visualization. |

| ITK-SNAP | Interactive software for semi-automatic segmentation using active contour methods. | Specifically used for detailed manual and level-set based delineation. |

| nnU-Net | Self-configuring framework for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. | "Out-of-the-box" training and inference for custom datasets with minimal configuration. |

| SimpleITK | Simplified layer built on the Insight Segmentation and Registration Toolkit (ITK). | Provides programmable access to filters (thresholding, morphological ops) and level sets in Python. |

| Elastix | Open-source toolbox for rigid and non-rigid image registration. | Core engine for deformably registering atlas images to a target patient scan. |

| PyTorch / MONAI | Deep learning frameworks with medical imaging-specific extensions. | Developing and training custom deep learning segmentation architectures. |

| MeshLab/3-Matic | Mesh processing software. | Converting segmentation labels (STL files) into surface meshes for FEM. |

Visualized Workflows

Title: FEM Generation and Segmentation Workflow

Title: nnU-Net Protocol for CTA Segmentation

Application Notes

In the pipeline for generating patient-specific finite element (FE) models from CT scans, the conversion of a segmented 3D volume into a high-quality surface mesh is a critical step. This "Surface Mesh Generation and Geometry Cleanup" phase directly dictates the accuracy, stability, and computational efficiency of subsequent FE analyses. A poor-quality mesh containing non-manifold edges, irregular triangles, or high-frequency surface noise can lead to solver divergence or physiologically implausible results, undermining the predictive value of the model for surgical planning or drug development research.

Recent methodologies emphasize a hybrid approach combining automatic algorithms with expert-guided intervention. Iso-surface extraction algorithms, such as Marching Cubes, are first applied to the segmented label map to generate an initial triangulated surface. This raw mesh is invariably contaminated by imaging artifacts and staircase aliasing effects from the discrete voxel grid. Subsequent remeshing techniques, including edge collapse/split, local reconnection, and vertex redistribution, are employed to create a more uniform and regular triangulation. Concurrently, smoothing algorithms must be applied judiciously; while they reduce surface noise, excessive smoothing can shrink the model and erode critical anatomical features. Laplacian and Taubin smoothing filters are commonly used, often with constrained or weighted parameters to preserve geometric fidelity at key landmarks. The ultimate goal is a watertight, manifold surface mesh suitable for volumetric meshing, with triangle quality metrics (e.g., aspect ratio, skewness) within acceptable thresholds for FE simulation.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-Stage Surface Mesh Generation and Cleanup for Cortical Bone

Objective: To generate a denoised, topology-corrected surface mesh of a femoral cortex from a segmented CT dataset for subsequent FE analysis of strain.

Materials:

- Segmented 3D binary mask of femoral cortex (output from Step 2: Image Segmentation).

- Software: 3D Slicer (v5.6.0) with MeshLabServer extension or standalone MeshLab (2024.02).

Procedure:

- Iso-surface Extraction: Input the binary mask into the

Marching Cubesmodule. Set the threshold value to 0.5. Generate the initial surface mesh (.stl file). - Topology Cleanup: Import the .stl into MeshLab. Apply the filter

Filters -> Cleaning and Repairing -> Remove Duplicate Vertices(tolerance: 1e-5). Then, applyFilters -> Cleaning and Repairing -> Remove Duplicate Faces. - Remeshing for Uniformity: Apply the

Filters -> Remeshing, Simplification and Reconstruction -> Uniform Mesh Resampling. SetTarget number of samplesto 200,000. EnableMerge close verticesandMultisampleoptions. - Feature-Preserving Smoothing: Apply

Filters -> Smoothing, Fairing and Deformation -> Laplacian Smooth(3 iterations,1D Boundarycheckbox UNCHECKED). Follow withFilters -> Smoothing, Fairing and Deformation -> Taubin Smooth(λ=0.5, μ=-0.53, 10 iterations) to mitigate shrinkage. - Quality Check: Apply

Filters -> Quality Measures and Computations -> Compute Geometric Measures. Record the face count and mesh volume. ApplyFilters -> Selection -> Select Faces with Aspect Ratio greater than...set to 10. If selected faces > 2% of total, revisit remeshing parameters.

Table 1: Mesh Quality Metrics Pre- and Post-Cleanup

| Metric | Raw Marching Cubes Mesh | After Remeshing & Smoothing | Target (Typical) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Faces | 1,542,891 | 201,447 | 150,000 - 300,000 |

| Non-Manifold Edges | 124 | 0 | 0 |

| Self-Intersections | 67 | 0 | 0 |

| Average Aspect Ratio | 4.8 | 1.7 | < 2.0 |

| Mesh Volume (mm³) | 64,512 | 64,488 | < 0.5% change |

Protocol 2: Vessel Wall Surface Preparation for Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD)

Objective: To create a smooth, luminal surface mesh of a coronary artery for CFD simulations in drug transport studies.

Materials:

- Segmented lumen mask (e.g., .nrrd file).

- Software: Vascular Modeling Toolkit (VMTK, v1.5).

Procedure:

- Centerline Extraction & Surface Generation: Use

vmtkcenterlineson the segmented volume. Then, generate an initial surface withvmtkmarchingcubes. - Surface Remeshing: Execute

vmtksurfaceremeshingwithtargetlengthset to 0.15 (mm). This uses a constrained Voronoi tessellation approach to create size-adaptive, isotropic triangles. - Geometric Smoothing: Apply

vmtksurfacesmoothingusingmethodset totaubin(iterations=50, passband=0.01). This preserves high-frequency geometric features critical for wall shear stress calculations. - Mesh Quality Assessment: Run

vmtksurfacemeshqualityto compute and output statistics on triangle quality and edge ratios.

Visualization

Surface Mesh Generation and Cleanup Workflow (82 characters)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software Tools for Surface Mesh Processing

| Tool / Solution | Primary Function | Relevance to Patient-Specific FE Model Generation |

|---|---|---|

| 3D Slicer | Open-source platform for medical image informatics. | Integrated environment for segmentation, initial mesh generation via Marching Cubes, and basic mesh cleanup modules. |

| MeshLab | Open-source system for processing and editing 3D triangular meshes. | Extensive toolbox for non-manifold repair, remeshing, smoothing, and detailed geometric quality assessment. |

| Vascular Modeling Toolkit (VMTK) | Open-source library for 3D reconstruction, analysis, and mesh generation for blood vessels. | Specialized algorithms for robust lumen surface extraction, centerline-based remeshing, and preparation of vascular geometries for CFD. |

| CGAL (Python Bindings) | Computational Geometry Algorithms Library. | Provides robust, state-of-the-art algorithms for surface mesh simplification, remeshing, and deformation in automated pipelines. |

| Autodesk Meshmixer | Proprietary software for 3D mesh manipulation. | Intuitive tool for interactive repair of mesh holes, extraneous artifacts, and manual smoothing of regions of interest. |

| PyVista / VTK | Python interfaces to the Visualization Toolkit (VTK). | Enables programmatic, scriptable control over the entire mesh processing pipeline, ideal for batch processing and reproducibility. |

Within the context of patient-specific finite element model (FEM) generation from CT scans, volumetric mesh generation is a critical step. The choice between tetrahedral (Tet) and hexahedral (Hex) elements directly impacts the accuracy, computational cost, and stability of biomechanical simulations used in surgical planning, implant design, and drug development research.

Element Characteristics: A Quantitative Comparison

The fundamental properties of tetrahedral and hexahedral elements are summarized below.

Table 1: Tetrahedral vs. Hexahedral Element Properties

| Property | Tetrahedral Elements (Tets) | Hexahedral Elements (Hexes) |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Geometry | 4 nodes, 4 triangular faces | 8 nodes, 6 quadrilateral faces |

| Automated Generation | Excellent for complex anatomy. Fully automatic algorithms (Delaunay, Advancing Front) are robust. | Challenging for complex geometries. Often requires semi-automatic multiblock sweeping or decomposition. |

| Mesh Density Control | Easy to refine locally using edge splitting. | More complex refinement often requires re-meshing the blocking structure. |

| Interpolation/Accuracy | Linear (4-node) or quadratic (10-node) shape functions. Can suffer from "volumetric locking" in nearly incompressible materials (e.g., soft tissue). | Trilinear (8-node) or triquadratic (20-node) shape functions. Generally more accurate per degree of freedom, less prone to locking. |

| Computational Cost | Lower cost per element, but requires more elements to achieve similar accuracy to hexes. | Higher cost per element, but fewer elements may be needed for target accuracy. |

| Aspect Ratio Sensitivity | Can tolerate larger aspect ratios without severe penalty. | Highly sensitive to element distortion, leading to Jacobian errors. |

| Dominant Application in Biomechanics | Complex anatomical structures (bones, aneurysms, lungs). | Structures with regular geometry (long bones, arterial segments) and explicit dynamics. |

Table 2: Performance Comparison in a Representative Biomechanical Study (Cortical Bone Simulation)

| Metric | Tetrahedral Mesh | Hexahedral Mesh |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Elements | ~1,200,000 | ~250,000 |

| Convergence Stress (MPa) | 148.5 ± 12.3 | 152.1 ± 5.8 |

| Relative Error vs. Benchmark | 6.8% | 2.1% |

| Simulation Runtime | 42 minutes | 28 minutes |

| Mesh Generation Time | 3 minutes (automatic) | 65 minutes (semi-automatic blocking) |

Experimental Protocols for Mesh Generation & Evaluation

Protocol 3.1: Patient-Specific Tetrahedral Mesh Generation from Segmented CT Data

Objective: To generate a conforming tetrahedral mesh of a femur from a segmented 3D binary image (STL file). Materials:

- Segmented 3D model (STL format)

- Mesh generation software (e.g., TetGen, ANSYS Meshing, 3D Slicer) Procedure:

- Import & Surface Preparation: Import the STL file. Run surface mesh repair tools to fix holes, non-manifold edges, and intersecting triangles.

- Define Mesh Parameters: Set global maximum tetrahedron volume (e.g., 1.0 mm³) to control density. Define local mesh refinement regions (e.g., around stress concentrators) using spatial functions.

- Generate Volume Mesh: Execute a constrained Delaunay tetrahedralization algorithm. Ensure the "–YY" flag (in TetGen) or equivalent is used to preserve the original surface.

- Mesh Quality Check: Calculate element quality metrics: Aspect Ratio (<3 optimal), Jacobian (>0.1), and Skewness (<0.7). Apply smoothing or optimization if needed.

- Export: Export the mesh in a solver-ready format (e.g., .inp, .msh, .cdb).

Protocol 3.2: Patient-Specific Hexahedral Mesh Generation via Image-Based Sweeping

Objective: To generate a structured hexahedral mesh for a tibial segment from a stack of CT images. Materials:

- Segmented image stack (DICOM or binary mask)

- Mesh generation software with blocking tools (e.g., ANSYS ICEM CFD, ScanIP+FE) Procedure:

- Image Stack Alignment: Ensure the image stack is aligned with the global Cartesian axes.

- Create Bounding Block: Define a single hexahedral block that encompasses the entire tibial segment.

- Associate Geometry: Project the edges of the block onto the outer contours of the bone in each principal plane. Use "curve to surface" association.

- Split & Subdivide Blocks: Split the initial block to better capture anatomical features. Create O-grids or Y-blocks around cylindrical sections.

- Define Edge Parameters: Specify the number of elements and bias factor along each block edge to grade the mesh.

- Generate Pre-Mesh: Compute the hexahedral mesh based on the defined blocking structure and parameters.

- Check & Smooth Mesh: Verify element quality (Jacobian > 0.3, Skewness < 0.5). Apply Laplacian smoothing to internal nodes.

- Export: Export the structured hex mesh in the required format.

Protocol 3.3: Protocol for Comparative Element Performance Testing

Objective: To evaluate the convergence and accuracy of Tet vs. Hex meshes for a simulated vertebroplasty. Materials: Two meshes (Tet and Hex) of the same lumbar vertebral body, finite element solver (e.g., Abaqus, FEBio). Procedure:

- Model Setup: Assign identical homogeneous, linear elastic material properties (E=500 MPa, ν=0.3) to both meshes. Apply identical boundary conditions (fixed inferior surface) and loads (uniform pressure on superior surface).

- Convergence Study: For each mesh type, create 4 series with increasing density (coarse to very fine). Perform linear static analysis for each.

- Data Collection: Record the maximum principal stress at a specific node and the total strain energy of the model for each simulation.

- Analysis: Plot the target metrics against the number of degrees of freedom. Determine the converged solution by identifying the point where the change between successive refinements is <2%.

- Benchmark Comparison: Compare the converged results from both element types to an analytical solution or a highly refined benchmark mesh. Calculate relative error.

Visualizing the Mesh Generation Decision Workflow

Title: Decision Workflow for Tet vs. Hex Mesh Selection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Software

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Volumetric Meshing

| Item | Function/Description | Example Product/Software |

|---|---|---|

| Medical Image Segmentation Suite | Converts DICOM CT scans into 3D label maps and surface models for meshing. | 3D Slicer, ITK-SNAP, Mimics (Materialise) |

| Surface Mesh Repair Tool | Fixes gaps, overlaps, and irregularities in the segmented surface before volume meshing. | MeshLab, Netfabb, Blender 3D |

| Tetrahedral Mesh Generator | Creates unstructured tetrahedral volume meshes from surface models automatically. | TetGen, Gmsh, ANSYS Meshing |

| Hexahedral Mesh Generator | Creates structured or semi-structured hex meshes, often requiring blocking. | ANSYS ICEM CFD, Hexpress (Numeca), Cubit |

| Finite Element Solver | Performs the biomechanical simulation using the generated volumetric mesh. | Abaqus, FEBio, ANSYS Mechanical |

| Mesh Quality Analyzer | Calculates Jacobian, aspect ratio, skewness, and other critical element metrics. | Verdict Library (integrated), MeshChecker tools |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Node | Provides the computational resources for generating dense meshes and running simulations. | Local clusters, Cloud computing (AWS, Azure) |

Application Notes

This section details the critical step of transforming a geometric mesh into a solvable biomechanical system within the context of patient-specific finite element model (FEM) generation from CT scans for applications in orthopedic and cardiovascular drug/device development. The accuracy of simulated mechanical responses—such as bone fracture risk, stent deployment, or implant stability—hinges on the precise definition of boundary conditions (BCs), physiological loads, and constitutive material models.

Boundary Conditions in Patient-Specific Models

Boundary conditions constrain the model to represent in vivo physiological fixation. Common types include:

- Dirichlet (Displacement) BCs: Fix degrees of freedom (e.g., zero displacement at bone ligamenti connections or rigidly fixed distal femur).

- Neumann (Force/Traction) BCs: Apply distributed or concentrated loads representing muscle forces, articular contact pressures, or vascular pressure.

- Symmetry and Cyclic BCs: Used to reduce computational cost or simulate repetitive loading.

Physiological Loads from Clinical Data

Loads are derived from in vivo measurements, gait analysis, or population-based studies, scaled using morphometric parameters from the CT scan (e.g., muscle attachment areas, bone density).

Material Model Assignment Based on Hounsfield Units (HU)

The key innovation in patient-specific modeling is the spatial mapping of heterogeneous material properties directly from CT attenuation (Hounsfield Units). This process is fundamentally non-linear and often anisotropic, especially for tissues like cortical bone and annulus fibrosus.

Table 1: Common Material Models for Biological Tissues in Patient-Specific FEM

| Tissue Type | Common Constitutive Model | Key Parameters (Typical Source) | Linear/Non-Linear | Isotropic/Anisotropic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trabecular Bone | Elastic-Plastic or Crushable Foam | Elastic Modulus (E) derived from HU-density-elasticity regression (e.g., ( E = aρ^b )). Yield stress. | Non-Linear | Isotropic (common assumption) |

| Cortical Bone | Orthotropic Linear Elastic | E1, E2, E3, G12, G13, G23, ν. From micro-CT or literature. | Linear (for small strains) | Anisotropic (Transversely isotropic or orthotropic) |

| Intervertebral Disc | Hyperelastic (e.g., Mooney-Rivlin) for matrix; Fiber-reinforced for annulus. | C10, C01 (matrix). Fiber stiffness & orientation from DTI or histology. | Non-Linear | Anisotropic (due to collagen fibers) |

| Blood Vessel / Soft Tissue | Fung-elastic or Ogden Hyperelastic | Material constants from biaxial testing, often fitted to patient cohort data. | Non-Linear | Isotropic or Anisotropic |

Table 2: Protocol for Assigning Bone Properties from CT Hounsfield Units

| Step | Parameter | Formula/Protocol | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Calibration | Phantom-equivalent Density (ρ_eq) | ( ρ_{eq} = a * HU + b ) | Scan-specific calibration using phantom. |

| 2. Conversion | Apparent Density (ρ_app) | ( ρ{app} = ρ{eq} * (BV/TV) ) (BV/TV from literature if not μCT). | Literature values for bone type. |

| 3. Assignment | Elastic Modulus (E) | ( E = c * ρ_{app}^d ) (c, d from empirical studies). | Key et al., Bone, 1998; Morgan et al., J Biomech, 2003. |

| 4. Mapping | Elemental Property Assignment | Direct voxel-to-element mapping via registration or sampling at Gauss points. | FE Meshing Software (e.g., Abaqus, FEBio). |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Non-Linear, Anisotropic Material Characterization for Cortical Bone

Objective: To derive patient-specific orthotropic elastic constants for cortical bone from high-resolution peripheral quantitative CT (HR-pQCT) data. Workflow:

- Image Acquisition: Obtain HR-pQCT scan of bone segment (e.g., distal tibia). Resolution: ~61 μm isotropic.

- Micro-FE Mesh Generation: Directly convert image voxels to hexahedral elements (voxel-conversion technique).

- Virtual Testing: Apply uniaxial strain in three principal anatomical directions (axial, medial-lateral, anterior-posterior) separately via displacement BCs on the mesh surface.

- Homogenization: Compute the average stress tensor within the region of interest for each load case.

- Parameter Calculation: Solve the orthotropic Hooke's law system of equations to extract the 9 independent elastic constants (E1, E2, E3, G12, G13, G23, ν12, ν13, ν23). Validation: Compare predicted apparent stiffness with results from ex vivo mechanical testing of the same bone (if available).

Protocol: Applying Physiological Loads to a Femur Model for Fracture Risk Assessment

Objective: To simulate a sideways fall loading scenario on a patient-specific proximal femur model. Workflow:

- BCs: Fully constrain all nodes on the distal-most 5% of the femur.

- Load Application:

- Map the force vector from a standardized fall configuration (e.g., 70° from horizontal, load applied to the greater trochanter).

- Apply the resultant force (magnitude scaled by patient body weight from CT metadata) as a distributed pressure over a representative contact area on the greater trochanter.

- Material Assignment: Use Table 2 protocol to assign heterogeneous, elastic-plastic material properties from the QCT scan.

- Solution: Run a quasi-static, non-linear analysis with large deformation.

- Output: Extract principal strains/stresses and identify regions exceeding yield criteria to predict fracture location.

Visualizations

Title: Patient-Specific FEM Property Assignment & Solving Workflow

Title: Material Model Selection Logic for Biological Tissues

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials & Software for Patient-Specific FEM Development

| Item | Function/Description | Example Product/Software |

|---|---|---|

| QCT/HR-pQCT Scanner | Provides 3D patient anatomy and density data (Hounsfield Units). | Siemens SOMATOM, Scanco Medical XtremeCT. |

| Calibration Phantom | Essential for converting scanner-specific HU values to equivalent bone mineral density. | Mindways QCT Bone Density Phantom, European Spine Phantom. |

| Segmentation Software | Isolates the region of interest (e.g., femur, vertebra) from the CT scan. | 3D Slicer, Mimics (Materialise), Simpleware ScanIP. |

| FE Meshing Software | Generates volumetric mesh from segmented geometry, enables property mapping. | ANSYS ICEM, FEBio Mesh, Abaqus CAE, 3-matic (Materialise). |

| FE Solver | Performs linear/non-linear analysis with complex material models and contact. | Abaqus, FEBio, ANSYS Mechanical, CalculiX. |

| Material Property Fitting Tool | Optimizes hyperelastic/anisotropic constants from experimental test data. | FEBio PreView & Fit, Abaqus/CAE Material Calibration. |

| In Silico Load Database | Provides population-based physiological load vectors and magnitudes for simulation. | Orthoload (for knee/hip loads), literature from gait labs. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Enables solving large, non-linear, patient-specific models in feasible time. | Local clusters, cloud computing (AWS, Azure). |

Application Notes

This section details the critical considerations for configuring finite element (FE) solvers and leveraging HPC resources in the context of patient-specific biomechanical modeling from CT data. The transition from model generation to solution is computationally demanding, requiring robust, scalable, and efficient numerical strategies.

Core Solver Considerations:

- Solver Type: Implicit solvers are typically required for static or quasi-static analyses common in bone mechanics (e.g., stress analysis under load). Explicit solvers may be necessary for dynamic events (e.g., impact). Nonlinear solvers are essential to capture material nonlinearity (e.g., plastic deformation) and contact mechanics between anatomical structures.

- Iterative vs. Direct Methods: For large-scale models (often >10 million degrees of freedom), iterative solvers (like Conjugate Gradient) with advanced preconditioning (e.g., Algebraic MultiGrid - AMG) are preferred on HPC systems due to their lower memory footprint and better parallel scalability compared to direct solvers.

- Contact Modeling: Defining accurate contact interfaces (e.g., between articular surfaces in a knee joint) is crucial. Penalty-based or augmented Lagrangian methods require careful selection of penalty parameters to balance accuracy and convergence.

- Material Model Implementation: Patient-specific material properties, often derived from CT Hounsfield Units, must be efficiently mapped to element integration points. User-defined material subroutines (e.g., UMAT for Abaqus) may be needed for complex constitutive laws.

HPC System Considerations:

- Parallel Scaling: FE solvers exhibit parallel scaling across three domains: Shared Memory (OpenMP) across CPU cores, Distributed Memory (MPI) across compute nodes, and Hybrid (MPI+OpenMP). Optimal configuration is system-dependent.

- Memory Architecture: High memory bandwidth (e.g., NVLink) is critical for iterative solver performance. Memory-per-core must be sufficient for the domain decomposition.

- I/O and Data Management: Reading input files and writing result files for massive models can become a bottleneck. Use of parallel file systems (e.g., Lustre, GPFS) and solver-specific restart/binary output is essential.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Solver Configurations for a Representative Femur Model (~5M Elements)

| Solver Configuration | Hardware (Nodes x Cores/Node) | Wall-clock Time (min) | Parallel Efficiency | Max Memory per Node (GB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct (MUMPS) | 1 x 32 | 142 | 100% (baseline) | 384 |

| Iterative (CG + AMG) | 1 x 32 | 89 | 100% (baseline) | 192 |

| Iterative (CG + AMG) | 2 x 32 (64 cores) | 48 | 93% | 96 |

| Iterative (CG + AMG) | 4 x 32 (128 cores) | 27 | 82% | 48 |

| Iterative (CG + AMG) | 8 x 32 (256 cores) | 16 | 70% | 24 |

Table 2: HPC Resource Requirements for Different Patient-Specific Model Fidelities

| Model Type | Approx. Elements | Degrees of Freedom | Estimated RAM Requirement | Recommended Min. Cores | Estimated Solution Time (Iterative Solver) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertebra (L4) | 1.2 million | 3.6 million | 50 GB | 16 | 25 min |

| Proximal Femur | 5 million | 15 million | 200 GB | 32 | 90 min |

| Full Knee Joint | 8 million | 24 million | 320 GB | 64 | 4 hours |

| Mandible with Implants | 12 million | 36 million | 480 GB | 128 | 8 hours |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Solver Performance and Parallel Scaling on an HPC Cluster Objective: To determine the optimal solver configuration and core count for efficient solution of patient-specific FE models.

- Model Preparation: Export a representative, large-scale model (e.g., the meshed femur from Step 5) in a solver-neutral format (e.g., INP, BDF).

- Job Script Generation: Create a series of batch job scripts for the target HPC system (e.g., SLURM, PBS). Each script should configure:

- Number of MPI tasks.

- Number of OpenMP threads per task.

- Solver type and parameters (e.g., convergence tolerance, preconditioner).