Fabricating the Future: A Comprehensive Guide to 3D Printed Bioceramic Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering

This article provides a detailed examination of modern 3D printing techniques for fabricating bioceramic scaffolds, targeting researchers and biomaterials professionals.

Fabricating the Future: A Comprehensive Guide to 3D Printed Bioceramic Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering

Abstract

This article provides a detailed examination of modern 3D printing techniques for fabricating bioceramic scaffolds, targeting researchers and biomaterials professionals. It covers the foundational principles of bioceramics, explores core fabrication methodologies like vat photopolymerization, extrusion, and powder bed fusion, addresses common technical challenges and optimization strategies, and critically validates performance through comparative analysis of mechanical, biological, and degradation properties. The scope is designed to guide the selection, development, and successful application of these advanced manufacturing techniques in regenerative medicine and drug delivery systems.

Bioceramics 101: Understanding the Core Materials and Design Principles for 3D Printed Scaffolds

Within the broader scope of a thesis investigating 3D printed bioceramic scaffolds fabrication techniques, understanding the material classification is foundational. The engineered scaffold's clinical role is dictated by its class: bioinert, bioactive, or biodegradable. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols relevant to researchers developing next-generation scaffolds for bone tissue engineering and drug delivery systems.

Key Classes: Definitions and Clinical Roles

Bioinert Bioceramics

Definition: Materials that maintain their structure in the biological environment, exhibiting minimal chemical interaction or integration with host tissue. The goal is mechanical stability without adverse reaction. Primary Materials: High-purity alumina (Al₂O₃), zirconia (ZrO₂). Clinical Role: Used in load-bearing applications where high mechanical strength and wear resistance are paramount, such as femoral heads in hip prostheses, dental implants, and bone plates/screws (limited use in scaffolds due to lack of integration).

Bioactive Bioceramics

Definition: Materials that interact with the physiological environment to form a direct, strong chemical bond with living bone tissue, often via the formation of a hydroxyapatite (HA) layer. Primary Materials: Hydroxyapatite (HA, Ca₁₀(PO₄)₆(OH)₂), bioactive glasses (e.g., 45S5 Bioglass), glass-ceramics (e.g., A-W glass-ceramic). Clinical Role: Ideal for coatings on metallic implants to enhance osteointegration and as the primary material for non-load-bearing bone defect fillers (e.g., periodontal repair, middle ear implants). In 3D-printed scaffolds, they promote bone ingrowth.

Biodegradable (Bioresorbable) Bioceramics

Definition: Materials designed to be gradually dissolved, absorbed, and replaced by newly formed host tissue over time. The resorption rate should match the tissue regeneration rate. Primary Materials: Beta-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP, Ca₃(PO₄)₂), certain bioactive glasses, sulfate-based ceramics (e.g., calcium sulfate). Clinical Role: Critical for temporary scaffolds in bone regeneration. They provide a temporary template for bone growth and are completely replaced, eliminating long-term implant presence. Used in cranio-maxillofacial defects, spinal fusion, and as drug delivery carriers.

Table 1: Key Properties and Clinical Applications of Bioceramic Classes

| Class | Exemplary Materials | Key Properties | Typical Clinical Applications | Integration Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinert | Al₂O₃, ZrO₂ (Y-TZP) | High compressive strength (>400 MPa), high hardness, low friction, chemical stability | Femoral heads, dental implant abutments, orthopedic bearings | Fibrous encapsulation; mechanical interlocking |

| Bioactive | HA, 45S5 Bioglass | Osteoconductive, forms surface HA layer in vivo, moderate strength (HA ~100 MPa compressive) | Coatings on hip/knee stems, bone void fillers, dental graft granules | Direct chemical bonding to bone (bioactive bonding) |

| Biodegradable | β-TCP, Calcium Sulfate | Osteoconductive, controlled resorption rate (β-TCP: 6-18 months), porous | Bone graft substitutes, periodontal defects, spinal fusion cages, drug-eluting scaffolds | Integration followed by gradual resorption and replacement |

Table 2: Quantitative Data for Common Bioceramics in Scaffold Fabrication

| Material | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Fracture Toughness (MPa·m¹/²) | Young's Modulus (GPa) | Resorption Time (Months) | 3D Printability (Notes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alumina (Al₂O₃) | 2500 - 4000 | 3 - 5 | 380 - 400 | Non-resorbable | Difficult; often sintered post-printing |

| Hydroxyapatite (HA) | 100 - 900 | ~1 | 70 - 120 | >24 (very slow) | Good via binder jetting/robocasting; brittle |

| 45S5 Bioglass | 50 - 500 | ~0.7 | 30 - 35 | 6 - 12 (variable) | Challenging due to crystallization; often used in composites |

| Beta-TCP (β-TCP) | 50 - 300 | ~1 | 60 - 90 | 6 - 18 | Excellent; common in extrusion/DLP printing |

Application Notes for 3D-Printed Scaffolds

Note 1: Material Selection for Porosity & Strength Trade-off

- Biodegradable β-TCP scaffolds are designed with interconnected porosity >60% for cell migration and vascularization, but this reduces compressive strength to the lower end of the range (~2-10 MPa for highly porous constructs).

- Protocol Consideration: For load-bearing sites, composite designs (e.g., PCL-coated β-TCP) or bioactive coatings on stronger bioinert cores are under research.

Note 2: The Role of Bioactivity in Scaffold Integration

- The formation of a carbonated HA layer on bioactive glasses in SBF (Simulated Body Fluid) is a critical predictor of in vivo performance.

- Standard Protocol: Immerse scaffold in SBF (pH 7.4, 37°C) for periods from hours to weeks. Characterize surface via SEM/EDS and XRD to confirm HA layer formation.

Note 3: Tailoring Degradation for Drug Delivery

- Biodegradable ceramic scaffolds can be co-printed with polymer binders containing growth factors (e.g., BMP-2) or antibiotics (e.g., gentamicin).

- Release Kinetics: The degradation rate of the ceramic matrix (and any polymer phase) directly controls drug release profile. Faster-resorbing calcium sulfate is used for short-term release, while slower β-TCP provides sustained release.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vitro Bioactivity Assessment (SBF Immersion Test)

Aim: To evaluate the surface bioactivity of a 3D-printed bioceramic scaffold by assessing its ability to form a hydroxyapatite (HA) layer.

Materials:

- 3D-printed bioceramic scaffold sample.

- Simulated Body Fluid (SBF), prepared as per Kokubo recipe.

- Sterile plastic containers or glass bottles.

- Water bath or incubator set to 37°C.

- pH meter.

- Analytical balance.

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS).

- X-ray Diffractometer (XRD).

Procedure:

- SBF Preparation: Prepare 1L of SBF by dissolving reagent-grade chemicals in DI water in the exact order and under constant stirring at 36.5°C. Maintain pH at 7.40 using Tris buffer and HCl.

- Sample Preparation: Weigh and record the dry mass of the scaffold. Sterilize if required for subsequent cell studies.

- Immersion: Place the scaffold in a container with a volume of SBF at least 100x the sample's surface area (estimated). Seal the container.

- Incubation: Immerse in a water bath at 37°C for predetermined periods (e.g., 1, 3, 7, 14 days). Replace the SBF solution every 48 hours to maintain ionic concentration.

- Post-Immersion: Remove the sample at each time point, rinse gently with DI water, and dry overnight in a 60°C oven.

- Analysis:

- SEM/EDS: Image the surface morphology. Look for cauliflower-like HA nodules. Perform EDS to confirm increased Ca/P ratio (~1.67).

- XRD: Analyze the crystalline phases. Look for the characteristic peaks of hydroxyapatite (e.g., at 2θ ≈ 26° and 32°).

Protocol 2: Compressive Strength Testing of Porous Scaffolds (ASTM F452)

Aim: To determine the mechanical integrity of a 3D-printed porous bioceramic scaffold under uniaxial compression.

Materials:

- Universal Testing Machine (UTM) with a calibrated load cell.

- Parallel, flat stainless steel platens.

- Sample scaffolds with parallel top/bottom surfaces (cylinder or cube, aspect ratio ~1:1 to 2:1).

- Calipers.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Sinter or cure scaffolds to final density. Measure sample dimensions (diameter/width, height) precisely using calipers at three points. Calculate cross-sectional area (A).

- UTM Setup: Mount the sample centrally on the lower platen. Align the upper platen to be parallel. Set a pre-load (~1N) to ensure full contact.

- Test Parameters: Set the compression test to displacement control with a constant crosshead speed of 0.5 mm/min. Ensure the load cell range is appropriate.

- Run Test: Initiate the test until sample failure (catastrophic fracture or a 20% drop from peak load).

- Data Analysis:

- Record the maximum load (Fmax) sustained.

- Calculate Compressive Strength (σ) = Fmax / A.

- Generate a stress-strain curve from load-displacement data to determine the elastic modulus (slope of the initial linear region).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Bioceramic Scaffold Research

| Item / Reagent Solution | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Beta-Tricalcium Phosphate (β-TCP) Powder | The primary raw material for fabricating biodegradable scaffolds. High-purity, sinterable powder with controlled particle size distribution (e.g., 1-5 µm) is essential for printability. |

| 45S5 Bioglass Particulates | The gold standard bioactive material. Used as a filler in composite inks or as a coating to confer bioactivity to otherwise inert scaffolds. |

| Photopolymerizable Ceramic Slurry (for DLP) | A ready-to-use suspension containing ceramic powder (HA, TCP) dispersed in a UV-curable monomer (e.g., acrylates). Enables high-resolution digital light processing (DLP) printing. |

| Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) Kit | A standardized pre-mixed salt kit or concentrate for consistent preparation of SBF, crucial for reproducible in vitro bioactivity testing. |

| Cell Culture Media (α-MEM, Osteogenic Supplements) | For in vitro cytocompatibility and osteogenesis studies. Often supplemented with FBS, ascorbic acid, β-glycerophosphate, and dexamethasone to test scaffold performance with osteoblast-like cells (e.g., MC3T3-E1). |

| Alginate or Methylcellulose-Based Binder | Temporary rheological modifiers used in extrusion-based 3D printing (Robocasting) to impart shape fidelity and green strength to ceramic pastes before sintering. |

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) Solution | A biodegradable polymer often used to coat brittle ceramic scaffolds to improve fracture toughness or to create polymer-ceramic composite filaments for FDM printing. |

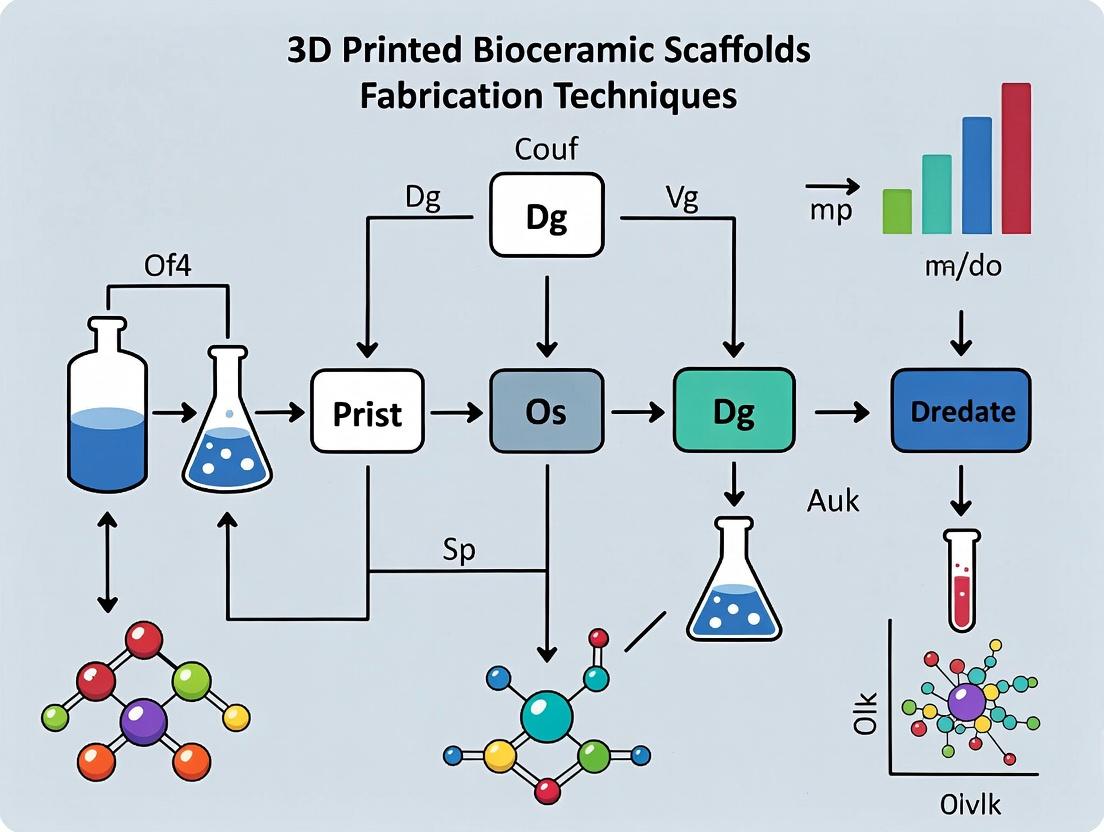

Visualization Diagrams

Diagram 1 Title: Scaffold Material Class Selection Flow

Diagram 2 Title: Bioactive Ceramic Integration Pathways

Diagram 3 Title: 3D-Printed Scaffold Evaluation Workflow

Within the broader thesis on 3D printed bioceramic scaffolds, this document details the critical, interrelated scaffold properties considered the "gold standard" for bone tissue engineering. These properties—porosity, pore size, interconnectivity, and mechanical strength—collectively dictate the success of scaffolds in supporting cell migration, nutrient/waste diffusion, vascularization, and load-bearing in defect sites. Optimizing these parameters is central to advancing fabrication techniques like extrusion-based, vat photopolymerization, and powder-bed 3D printing.

The target values for ideal scaffold properties are derived from the physiological and mechanical requirements of native bone tissue. The following table consolidates current consensus targets from recent literature.

Table 1: Target Ranges for Ideal 3D Printed Bioceramic Scaffold Properties

| Property | Optimal Target Range | Rationale & Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Porosity | 60 - 80% | Balances space for tissue ingrowth and neovascularization with sufficient mechanical integrity. Porosity <50% impedes infiltration; >90% severely compromises strength. |

| Pore Size | 100 - 500 μm | 100-200 μm: Supports cell migration and attachment. >300 μm: Essential for osteoconduction, vascularization, and bone formation. Macro-pores (>500 μm) can enhance vascular ingrowth but may reduce surface area for initial cell adhesion. |

| Interconnectivity | >99% | Absolute requirement for uniform cell distribution, vascularization, and nutrient diffusion. Pores must be fully interconnected; dead-end pores lead to necrotic cores. |

| Compressive Strength | 2 - 12 MPa (Trabecular bone range) | Must match the mechanical properties of the host bone (cancellous: 2-12 MPa; cortical: 100-200 MPa) to avoid stress shielding while providing temporary load-bearing support. |

| Young's Modulus | 0.5 - 3 GPa (Trabecular bone range) | Should approximate the modulus of trabecular bone to promote mechanical stimulation of osteogenic cells and proper load transfer. |

Experimental Protocols for Property Characterization

Protocol: Micro-Computed Tomography (μ-CT) for Porosity, Pore Size, and Interconnectivity

Objective: To quantitatively measure the 3D architectural parameters of a fabricated bioceramic scaffold non-destructively. Materials: Desktop μ-CT scanner (e.g., SkyScan 1272), scaffold sample (<20 mm diameter), mounting stub, image analysis software (e.g., CTAn, ImageJ/Fiji with BoneJ plugin). Procedure:

- Mounting: Secure the dry scaffold sample vertically on the stub using adhesive putty. Ensure it does not move during rotation.

- Scanning Parameters: Set X-ray voltage to 70 kV, current to 142 μA. Use a 0.5 mm aluminum filter. Set rotation step to 0.4° over 180°, with an exposure time of 1000 ms per frame. Pixel resolution should be ≤10 μm.

- Reconstruction: Use manufacturer software (e.g., NRecon) to reconstruct 2D cross-sections from projection images. Apply beam hardening correction (30%) and ring artifact correction (10).

- Binarization & Analysis:

- Import reconstructed image stack into CTAn.

- Apply a uniform global threshold (e.g., Otsu method) to segment scaffold material from pores.

- Porosity: Calculate as (Volume of Voids / Total Volume) * 100%.

- Pore Size Distribution: Execute the sphere-fitting algorithm for pore diameter distribution.

- Interconnectivity: Use the "Analysis of Interconnectivity" function. Interconnectivity (%) = (Interconnected Pore Volume / Total Pore Volume) * 100.

Protocol: Uniaxial Compression Test for Mechanical Strength

Objective: To determine the compressive strength and modulus of a bioceramic scaffold. Materials: Universal mechanical testing system (e.g., Instron 5967), 1 kN load cell, parallel plate platens, calipers, 3D printed bioceramic scaffold (cylindrical, aspect ratio ~1:1). Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Fabricate cylindrical scaffolds (e.g., Ø10mm x 10mm). Dry thoroughly at 80°C for 24h. Measure exact diameter and height with calipers at three points each.

- Test Setup: Mount the scaffold between two steel platens. Ensure the top and bottom surfaces are parallel to the platens. Set the crosshead speed to 0.5 mm/min.

- Data Acquisition: Initiate the test and record load (N) vs. displacement (mm) until sample fracture or a 70% strain limit is reached.

- Analysis:

- Compressive Strength (σ): Calculate as σ = Fmax / A, where Fmax is the maximum load prior to fracture and A is the original cross-sectional area.

- Young's Modulus (E): Calculate the slope of the initial linear elastic region of the stress-strain curve (typically between 0.05% and 0.25% strain).

Visualizing the Property-Performance Relationship

Title: Scaffold Properties Drive Bone Regeneration

Title: Iterative Scaffold Development Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Bioceramic Scaffold Fabrication & Testing

| Item | Function/Application | Example Product/Brand |

|---|---|---|

| Beta-Tricalcium Phosphate (β-TCP) Powder | Primary osteoconductive ceramic material for ink/slurry formulation. | Sigma-Aldrich, Berkeley Advanced Biomaterials |

| Hydroxyapatite (HA) Nano-powder | Blended with β-TCP to form biphasic calcium phosphate (BCP) for enhanced bioactivity. | Fluidinova, Cam Bioceramics |

| Sodium Alginate | A biocompatible rheology modifier and temporary binder for extrusion-based printing. | Sigma-Aldrich, Pronova UP MVG |

| Pluronic F-127 | A sacrificial polymer used to create porogens in the ink, increasing porosity after sintering. | Sigma-Aldrich, BASF |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) Binder | Used in powder-bed printing to temporarily bind ceramic particles prior to sintering. | Sigma-Aldrich, Kuraray Poval |

| Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) | To test scaffold bioactivity and apatite-forming ability in vitro. | Biorelevant.com, prepared in-house per Kokubo recipe |

| AlamarBlue or PrestoBlue Assay | Cell viability/proliferation reagent for assessing cytocompatibility on scaffolds. | Thermo Fisher Scientific, Invitrogen |

| Osteogenic Media Supplements | Induces osteogenic differentiation of seeded MSCs; includes ascorbic acid, β-glycerophosphate, dexamethasone. | Sigma-Aldrich, STEMCELL Technologies |

| Micro-CT Calibration Phantom | For validating grayscale values and ensuring accuracy of porosity/pore size measurements. | Bruker, Scanco |

| Hydraulic Cements (e.g., Brushite) | Used as a reference material for comparing mechanical properties of novel scaffolds. | Sigma-Aldrich, prepared in-house |

The fabrication of 3D printed bioceramic scaffolds represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine, enabling the creation of patient-specific, geometrically complex, and biologically functional implants. This process integrates Computer-Aided Design (CAD) with advanced additive manufacturing (AM) techniques to transition from a digital blueprint to a physical, porous scaffold that mimics the native extracellular matrix (ECM). The precision afforded by 3D printing allows for controlled architecture, influencing mechanical properties, degradation kinetics, and ultimately, in vivo osteointegration and vascularization.

Key Application Areas:

- Bone Tissue Engineering: Repair of critical-sized craniofacial, maxillofacial, and orthopedic bone defects.

- Drug Delivery Systems: Localized, sustained release of osteogenic factors (e.g., BMP-2), antibiotics, or chemotherapeutics from the scaffold matrix.

- Disease Modeling: Creation of in vitro platforms for studying bone metastasis or osteoporosis.

- Dental Implantology: Fabrication of customized alveolar ridge augmentation scaffolds.

Critical Considerations: The transition from CAD to scaffold necessitates meticulous attention to material printability (rheology, sintering behavior), scaffold design (pore size >300µm for vascularization, interconnectivity >99%), post-processing (debinding, sintering), and sterilization compatibility (gamma irradiation, autoclaving).

Quantitative Data on Common 3D Printing Techniques for Bioceramics

Table 1: Comparison of Primary 3D Printing Techniques for Bioceramic Scaffold Fabrication

| Technique | Typical Materials | Resolution (µm) | Porosity Range (%) | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation | Representative Compressive Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robocasting/Direct Ink Writing (DIW) | HA, β-TCP, SiO₂-based glass, composite inks | 100 - 500 | 20 - 70 | High ceramic loading; excellent mechanical integrity. | Limited to self-supporting inks; slower print speeds. | 5 - 150 (varies with material & porosity) |

| Stereolithography (SLA) / Digital Light Processing (DLP) | Photopolymerizable ceramic slurries (HA, Al₂O₃, ZrO₂) | 10 - 100 | 30 - 80 | Ultra-high resolution; smooth surface finish. | Limited material depth; requires photoinitiators & debinding. | 2 - 80 |

| Selective Laser Sintering/Melting (SLS/SLM) | HA, TCP, Bioglass powders | 50 - 150 | 10 - 60 | No need for binders; can create dense parts. | High temperature; limited to semi-crystalline materials; rough surface. | 50 - 200+ |

| Binder Jetting | HA, TCP, Calcium Sulfate powders | 50 - 200 | 40 - 70 | High speed; full-color capability. | Low green strength; requires extensive post-processing infiltration. | 1 - 20 (pre-inflitration) |

Table 2: Impact of Scaffold Architectural Parameters on Biological Outcomes (In Vitro/In Vivo Data Summary)

| Pore Size (µm) | Interconnectivity (%) | Primary Biological Outcome | Observed Cell Type/Model | Reference Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100-200 | >95% | Enhanced cell adhesion & proliferation. | MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts | Higher initial cell attachment observed. |

| 300-500 | >99% | Optimal vascularization & new bone ingrowth. | HUVECs; Canine femoral defect | Significant capillary network formation and osseointegration. |

| 500-800 | >99% | Potential for fibrovascular tissue invasion. | Rat calvarial defect | Faster tissue infiltration, but lower mechanical strength. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Robocasting of β-Tricalcium Phosphate (β-TCP) Scaffolds

Objective: To fabricate a 3D porous β-TCP scaffold with a grid-like architecture via direct ink writing.

I. Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| β-TCP Powder (d50 < 1µm) | Primary bioceramic material; osteoconductive. |

| Pluronic F-127 (25 wt% in DI Water) | Sacrificial thermoreversible gel; provides viscoelasticity for extrusion. |

| Orthophosphoric Acid (H₃PO₄, 0.1M) | Dispersant and reaction agent for chemical setting. |

| Sodium Alginate (4 wt% solution) | Optional co-binder for ionic crosslinking. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂, 100mM) | Crosslinking solution for alginate-containing inks. |

| 3-Axis Robocasting System | Precision extrusion system with controlled pressure/plunger. |

| Cylindrical Nozzle (200-410µm) | Defines filament diameter and pore size. |

II. Methodology

- Ink Formulation: Mix 45 vol% β-TCP powder into the Pluronic F-127 solution. Add H₃PO₄ (2-5 vol%) dropwise under vigorous mixing (planetary centrifugal mixer, 2000 rpm, 5 min). Cool on ice to increase viscosity for printing.

- CAD & Slicing: Design a 10x10x5 mm³ 3D lattice (0/90° laydown pattern) in CAD software. Slice the model with a layer height of 80% of the nozzle diameter. Generate G-code.

- Printing Setup: Load ink into a syringe barrel. Attach nozzle. Mount syringe in the robocaster. Set bed temperature to 4°C to maintain ink viscosity.

- Printing: Extrude ink at a constant pressure (500-700 kPa) with a print speed of 5-10 mm/s. Deposit filaments in a layer-by-layer fashion.

- Post-Printing Crosslinking: Immerse the printed "green" scaffold in 100mM CaCl₂ solution for 1 hour if alginate is used.

- Debinding & Sintering: Slowly heat to 600°C (1°C/min) to burn out organics. Sinter at 1150°C for 2 hours (heating rate: 5°C/min). Cool slowly to room temperature.

Protocol 3.2: In Vitro Osteogenic Differentiation Assessment on Printed Scaffolds

Objective: To evaluate the biocompatibility and osteoinductive potential of a printed bioceramic scaffold using human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs).

I. Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| hMSCs (e.g., Lonza) | Primary cell model for bone formation. |

| Osteogenic Media: DMEM, 10% FBS, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 µg/mL ascorbic acid, 100 nM dexamethasone. | Induces and supports osteogenic differentiation. |

| Alizarin Red S Staining Solution (2%, pH 4.1-4.3) | Binds to calcium deposits, indicating mineralization. |

| Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) | Colorimetric assay for quantifying viable cell number. |

| qPCR Reagents: RNA isolation kit, cDNA synthesis kit, SYBR Green master mix, primers for RUNX2, OSX, OPN, GAPDH. | Quantifies expression of osteogenic marker genes. |

II. Methodology

- Scaffold Sterilization & Pre-wetting: Autoclave scaffolds. Immerse in complete growth media overnight.

- Cell Seeding: Seed hMSCs at 5x10⁴ cells/scaffold in a droplet. Incubate for 2 hours, then add media.

- Proliferation (Day 1, 3, 7): Transfer scaffolds to new wells. Add CCK-8 reagent (10% v/v). Incubate for 2 hours. Measure absorbance at 450 nm.

- Osteogenic Induction: Maintain test group in osteogenic media, control group in growth media. Change media twice weekly.

- Gene Expression (Day 7, 14): Lyse cells in TRIzol. Isolate RNA, synthesize cDNA. Perform qPCR for RUNX2, OSX, OPN. Normalize to GAPDH using the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method.

- Mineralization Assay (Day 21): Fix cells with 4% PFA for 30 min. Stain with Alizarin Red S for 20 min. Wash extensively. For quantification, dissolve stain with 10% cetylpyridinium chloride and measure absorbance at 562 nm.

Visualization Diagrams

3D Printing Workflow for Bioceramic Scaffolds

Osteogenic Differentiation Pathway on Scaffolds

Application Notes

Bone Regeneration

3D-printed bioceramic scaffolds (e.g., β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP), hydroxyapatite (HA), biphasic calcium phosphate (BCP)) are engineered to mimic cancellous bone architecture, promoting osteoconduction and osteoinduction. Recent studies focus on incorporating bioactive ions (Sr²⁺, Mg²⁺, Zn²⁺) to enhance osteogenic differentiation and angiogenesis. Pore geometry (500-800 µm) and interconnectivity (>90%) are critical for cell migration, vascularization, and nutrient diffusion. In vivo models show >70% new bone infiltration within 8-12 weeks in critical-sized defect models.

Craniofacial Repair

Patient-specific implants for maxillofacial and cranial defects are fabricated via medical imaging (CT/CBCT) and 3D printing (e.g., robocasting, stereolithography). Materials like HA/β-TCP composites or polymer-ceramic hybrids (e.g., PCL/HA) balance mechanical strength (compressive strength: 2-30 MPa) with resorption rates. Key applications include sinus floor augmentation, alveolar ridge preservation, and orbital floor reconstruction, with clinical success rates >85% for integration.

Drug Delivery

Bioceramic scaffolds serve as localized, sustained-release systems for osteogenic (e.g., BMP-2), angiogenic (VEGF), or antimicrobial (gentamicin, vancomycin) agents. Drug loading is achieved via adsorption, co-printing, or encapsulation in microspheres embedded within the scaffold matrix. Release kinetics (typically biphasic: burst release followed by sustained release over 2-8 weeks) are modulated by scaffold composition, porosity, and surface functionalization.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of 3D-Printed Bioceramic Scaffolds in Preclinical Studies

| Application | Material System | Porosity (%) | Pore Size (µm) | Compressive Strength (MPa) | New Bone Formation (%)* | Key Loaded Agent | Release Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Regeneration | β-TCP | 70-80 | 500-700 | 2-10 | 75 ± 12 (12 wks) | BMP-2 | 28 days |

| Bone Regeneration | BCP (HA/β-TCP 60/40) | 60-70 | 400-600 | 10-20 | 82 ± 8 (12 wks) | Sr²⁺ ions | N/A (ionic release) |

| Craniofacial Repair | HA/PCL composite | 50-60 | 300-500 | 15-30 | 88 ± 5 (24 wks) | PDGF-BB | 21 days |

| Craniofacial Repair | GelMA-HA hybrid | 75-85 | 200-400 | 0.5-2.0 | 70 ± 10 (8 wks) | VEGF | 14 days |

| Drug Delivery | Mesoporous SiO₂/β-TCP | 65-75 | 100-300 | 5-15 | N/A | Doxycycline | 56 days |

| Drug Delivery | Gentamicin-loaded HA | 55-65 | 500-700 | 20-25 | N/A | Gentamicin sulfate | 42 days |

Measured via histomorphometry in rodent calvarial or femoral defect models. *Micropores for drug elution within macropores for cell ingress.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication & Osteogenic Efficacy Testing of Ion-Doped β-TCP Scaffolds

Aim: To fabricate Sr²⁺-doped β-TCP scaffolds and evaluate osteogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Materials: β-TCP powder, Sr(NO₃)₂, Pluronic F-127 as binder, MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblast cells, male Sprague-Dawley rats. Methods:

- Ink Preparation: Mix β-TCP powder with 5 wt% Sr(NO₃)₂ (for 5% Sr doping). Disperse in 25 wt% Pluronic F-127 solution.

- 3D Printing: Use a robocasting system (nozzle Ø 410 µm) to print lattice scaffolds (layer height 300 µm, pore size 500x500 µm). Sinter at 1250°C for 2h.

- Material Characterization: SEM for morphology, XRD for phase analysis, compression testing (ASTM D695).

- In Vitro Study: Seed scaffolds with MC3T3-E1 cells (2x10⁵ cells/scaffold). Culture in osteogenic medium. Assess at days 7, 14, 21: ALP activity (pNPP assay), osteocalcin expression (ELISA), and mineralization (Alizarin Red S staining).

- In Vivo Study: Create two 5-mm calvarial defects in each rat (n=6/group). Implant: (1) Sr-β-TCP, (2) pure β-TCP, (3) empty defect. Euthanize at 12 weeks. Analyze via µ-CT (bone volume/total volume, BV/TV) and histology (H&E, Masson's trichrome).

Protocol 2: Fabrication of Drug-Eluting Craniofacial Scaffolds

Aim: To fabricate patient-specific, VEGF-loaded scaffolds for mandibular bone regeneration. Materials: Medical CT DICOM data, PCL, nano-HA, recombinant human VEGF₁₆₅, gelatin microparticles, solvent (chloroform). Methods:

- Design: Convert CT data to 3D model (Mimics). Design a porous scaffold (300-500 µm pores) fitting the defect (3-matic).

- Drug Carrier Preparation: Prepare VEGF-loaded gelatin microparticles via aqueous phase separation. Encapsulation efficiency >90%.

- Ink/Extrudate Preparation: Dissolve PCL in chloroform (15% w/v). Mix with nano-HA (20% w/w of polymer) and gelatin microparticles (VEGF load: 100 ng/mg scaffold).

- 3D Printing: Use a pneumatic extrusion printer (heated nozzle at 90°C) to fabricate scaffold. Dry under vacuum.

- Release Kinetics: Immerse scaffold in PBS (pH 7.4) at 37°C under gentle agitation (n=5). Collect supernatant at predetermined intervals. Quantify VEGF via ELISA. Fit data to Korsmeyer-Peppas model.

- In Vivo Evaluation: Implant in rabbit mandibular defect model (n=8). Evaluate at 4 and 8 weeks for new bone formation and blood vessel density (CD31 immunohistochemistry).

Diagrams

Diagram 1: Osteogenic Signaling Pathway Activated by Sr²⁺-Doped Bioceramics

Diagram 2: Workflow for Developing Drug-Loaded Craniofacial Scaffolds

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bioceramic Scaffold Research

| Item | Function/Description | Example Supplier/Cat. No. (for reference) |

|---|---|---|

| β-Tricalcium Phosphate (β-TCP) Powder | Primary osteoconductive ceramic material for ink formulation. | Sigma-Aldrich, 542991 |

| Hydroxyapatite (HA), Nano-sized | Enhances bioactivity and protein adsorption in composite inks. | Berkeley Advanced Biomaterials, Inc. |

| Pluronic F-127 | Thermoresponsive sacrificial binder for robocasting. | Sigma-Aldrich, P2443 |

| Recombinant Human BMP-2 | Gold-standard osteoinductive growth factor for loading. | PeproTech, 120-02 |

| Recombinant Human VEGF₁₆₅ | Angiogenic growth factor for enhancing vascularization. | R&D Systems, 293-VE |

| Gelatin (Type A) | For creating drug-encapsulating microparticles. | Sigma-Aldrich, G1890 |

| AlamarBlue Cell Viability Reagent | Resazurin-based assay for monitoring cell proliferation on scaffolds. | Thermo Fisher Scientific, DAL1025 |

| Osteocalcin (OCN) ELISA Kit | Quantifies osteogenic differentiation in vitro. | Thermo Fisher Scientific, BMS2022INST |

| p-Nitrophenyl Phosphate (pNPP) | Substrate for colorimetric Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) activity assay. | Sigma-Aldrich, N2770 |

| Alizarin Red S Solution | Stains calcium deposits for quantifying in vitro mineralization. | ScienCell Research Laboratories, 0223 |

Hands-On Fabrication: A Deep Dive into Leading 3D Printing Techniques for Bioceramics

Vat photopolymerization, encompassing Stereolithography (SLA) and Digital Light Processing (DLP), has emerged as a premier technique for fabricating high-resolution, complex bioceramic scaffolds (e.g., hydroxyapatite, β-tricalcium phosphate) for bone tissue engineering and drug delivery. Within a thesis on 3D-printed bioceramic scaffolds, this technique is pivotal for achieving the architectural precision (features down to ~25 µm) necessary to mimic bone microstructure, control porosity for cell migration/vascularization, and create tailored drug eluting devices.

Key Application Notes

2.1. Resolution and Accuracy: DLP/SLA can achieve XY resolutions of 20-50 µm and layer thicknesses of 10-100 µm, enabling the fabrication of scaffolds with controlled pore size (200-600 µm) and interconnectivity critical for osteogenesis.

2.2. Material Considerations: The process requires a photocurable ceramic suspension (slurry). Key challenges include achieving high ceramic loading (>40 vol%) for sufficient green body density while maintaining low viscosity for recoating and ensuring uniform dispersion to prevent light scattering.

2.3. Post-Processing Imperative: As-printed "green" parts contain uncured resin and require meticulous post-processing: solvent washing, thermal debinding to remove the polymer binder, and sintering (often >1100°C) to achieve final density and mechanical strength.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of SLA vs. DLP for Bioceramic Fabrication

| Parameter | Stereolithography (SLA) | Digital Light Processing (DLP) |

|---|---|---|

| Light Source | Single UV Laser (e.g., 355 nm) | UV Projector (LED/LCD, 385-405 nm) |

| Build Style | Point-by-point scanning | Whole-layer projection |

| Typical XY Resolution | 10-50 µm | 20-50 µm (pixel size dependent) |

| Typical Layer Thickness | 25-100 µm | 25-100 µm |

| Build Speed | Slower for dense features | Faster for full layers |

| Ceramic Loading (Typical Vol%) | 40-55% | 40-50% |

| Key Advantage | Superior fine-feature resolution | Faster build speed for uniform layers |

Table 2: Representative Sintering Parameters for Common Bioceramics

| Bioceramic Material | Debinding Ramp Rate (°C/h) | Sintering Temperature (°C) | Sintering Hold Time (h) | Final Relative Density (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxyapatite (HA) | 20-30 | 1200-1300 | 2-3 | >95% |

| β-Tricalcium Phosphate (β-TCP) | 20-30 | 1100-1150 | 2-3 | >94% |

| HA/β-TCP Biphasic | 20 | 1250 | 2 | >93% |

| Silica-doped HA | 20 | 1150-1200 | 2 | >95% |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Formulation of a Photocurable Ceramic Suspension

Objective: Prepare a stable, high-solid-loading slurry for DLP printing of hydroxyapatite scaffolds. Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below. Procedure:

- Pre-drying: Dry HA powder at 120°C for 12 hours to remove moisture.

- Premixing: In a light-protected container, combine 70 wt% of the total photopolymer resin (e.g., a blend of HDDA, PEGDA, and photoinitiator) with 40 vol% of the dried HA powder.

- Primary Mixing: Use a planetary centrifugal mixer for 2 minutes at 2000 rpm to achieve a preliminary blend.

- Dispersion & Deagglomeration: Transfer the mixture to a ball mill jar. Add the remaining 30% of resin and 0.5 wt% (relative to powder) of dispersant. Mill for 24 hours using zirconia balls.

- Degassing: After milling, place the slurry in a vacuum desiccator for 30-60 minutes until air bubbles are removed.

- Characterization: Measure viscosity (target < 5 Pa·s at 30 s⁻¹ shear rate) and cure depth (Dp) via working curve measurement.

Protocol 2: DLP Printing & Post-Processing of Green Scaffolds

Objective: Print and process a lattice scaffold structure. Materials: Prepared HA slurry, IPA, sintering furnace. Procedure:

- Printer Setup: Load slurry into the DLP vat. Set parameters: Layer thickness = 50 µm, Exposure time = 8 s/layer (optimized via working curve), Light intensity = 15 mW/cm².

- Printing: Initiate build. Ensure consistent recoating between layers.

- Initial Cleaning: After build, drain part and remove excess slurry. Immerse in IPA bath with gentle agitation for 5 minutes to remove surface slurry.

- Secondary Cleaning: Transfer to a second, clean IPA bath and agitate for 10 minutes. Use an ultrasonic cleaner for 1-2 minutes with caution.

- Post-Curing: Cure the cleaned "green" part under a broad-spectrum UV lamp (405 nm) for 10 minutes per side.

- Thermal Processing: a. Debinding: Heat in air at a slow ramp rate (0.5-1°C/min) to 600°C, hold for 1-2 hours. b. Sintering: In air, ramp at 3°C/min to 1250°C, hold for 2 hours, then furnace cool.

Diagrams

Title: VPP Bioceramic Scaffold Fabrication Workflow

Title: Key Factors Influencing Scaffold Outcome

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for VPP of Bioceramic Suspensions

| Item | Function & Rationale | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Bioceramic Powder | The bioactive filler material. Determines scaffold bioactivity, degradation, and final mechanical properties. | Hydroxyapatite (HA, Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2), <5 µm particle size, high purity (>99%). |

| Photoreactive Monomer | The liquid matrix that polymerizes under light. Provides green strength and is later removed during debinding. | 1,6-Hexanediol diacrylate (HDDA), Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA). Low viscosity for high solids loading. |

| Photoinitiator | Absorbs light energy to generate radicals, initiating polymerization. Must match light source wavelength. | Phenylbis(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)phosphine oxide (BAPO, for 385-420 nm). |

| Dispersant | Reduces interparticle forces, prevents agglomeration, and stabilizes the suspension for uniform curing and density. | Phosphate ester-based dispersants (e.g., BYK-111), typically 0.5-2.0 wt% of powder. |

| UV Absorber/Dye | Controls light penetration depth, improving XY resolution and preventing overcuring between layers. | Sudan I, Tinuvin 326 (very low concentrations, <0.1 wt%). |

| Dispersion Solvent | For post-print cleaning of uncured resin from the green part. Must be compatible with resin chemistry. | Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA), 99% purity. |

| Debinding/Sintering Furnace | For the critical thermal post-processing to remove polymer and densify the ceramic. Requires precise atmosphere control. | High-temperature box furnace (max temp >1400°C), with programmable ramps and air/controlled atmosphere. |

Application Notes

Direct Ink Writing (DIW) of ceramic pastes and composites is a pivotal additive manufacturing technique within the broader thesis on 3D printed bioceramic scaffolds for bone tissue engineering and drug delivery. This technique enables the precise, layer-by-layer deposition of high-viscosity ceramic inks to create complex, porous structures that mimic bone architecture. Its relevance lies in overcoming traditional fabrication limitations, allowing for customized scaffold geometry, controlled porosity for vascularization, and the incorporation of bioactive molecules or drugs. For researchers and drug development professionals, DIW offers a versatile platform for developing patient-specific implants with tailored mechanical properties and release kinetics for therapeutic agents.

Key Quantitative Parameters for DIW of Bioceramic Inks

The printability and final scaffold properties are governed by specific rheological and compositional parameters. The table below summarizes critical quantitative data from recent studies.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters for DIW Bioceramic Inks and Scaffolds

| Parameter | Typical Range for DIW | Influence on Scaffold Properties | Target for Bone Scaffolds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ink Viscosity | 10 - 1000 Pa·s (at shear rate 0.1 s⁻¹) | Determines shape fidelity & filament collapse. | >50 Pa·s for structural integrity. |

| Yield Stress | 50 - 5000 Pa | Prevents sagging; enables self-support. | 200-2000 Pa. |

| Storage Modulus (G') | 1 x 10³ - 1 x 10⁶ Pa | Indicates elastic solid-like behavior. | G' > G'' (loss modulus). |

| Ceramic Solid Loading | 40 - 60 vol% | Affects sintering shrinkage, final density, & mechanical strength. | ~50 vol% for balance. |

| Nozzle Diameter | 100 - 500 µm | Determines filament size & printing resolution. | 200-400 µm for trabecular bone mimicry. |

| Printing Pressure | 200 - 800 kPa | Drives extrusion; must match ink rheology. | Optimized for consistent filament flow. |

| Sintering Temperature | 1100 - 1350 °C (for HA/β-TCP) | Determines final crystallinity, density, & compressive strength. | Phase-dependent (e.g., 1250°C for HA). |

| Final Compressive Strength | 2 - 150 MPa | Critical for load-bearing bone defect sites. | >10 MPa for trabecular bone. |

| Porosity | 50 - 70% | Facilitates cell infiltration, vascularization, & nutrient diffusion. | 60-70% interconnected porosity. |

| Pore Size | 200 - 600 µm | Optimal for osteogenesis and bone ingrowth. | 300-500 µm target. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Formulation and Rheological Characterization of a Bioactive Ceramic Composite Ink

This protocol details the preparation of a shear-thinning, self-supporting ink suitable for DIW, composed of hydroxyapatite (HA) and beta-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) in a pluronic-alginate carrier system.

Materials:

- Hydroxyapatite (HA) powder (< 5 µm particle size)

- Beta-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) powder (< 5 µm particle size)

- Sodium alginate (medium viscosity)

- Pluronic F-127

- Deionized water

- Calcium chloride (CaCl₂) solution (100 mM)

- Centrifugal mixer (Thinky ARE-310)

- Rheometer (e.g., TA Instruments DHR, Malvern Kinexus) with parallel plate geometry

- DIW 3D printer (e.g., 3D-Bioplotter, custom pneumatic system)

Methodology:

- Pre-mix Preparation: Dissolve 4% (w/v) sodium alginate and 18% (w/v) Pluronic F-127 in deionized water under magnetic stirring at 4°C for 12 hours to form a clear hydrogel precursor.

- Powder Integration: Gradually blend a 70:30 mixture of HA and β-TCP powders into the hydrogel precursor to achieve a final ceramic solid loading of 45 vol%. Use a centrifugal mixer (2000 rpm, 5 minutes, 3 cycles) to ensure homogeneous dispersion and deaeration.

- Rheological Assessment:

- Load the ink onto the rheometer plate (25°C, 1 mm gap).

- Perform a flow sweep test: measure viscosity over a shear rate range of 0.01 to 100 s⁻¹ to confirm shear-thinning behavior.

- Perform an oscillatory amplitude sweep test: at a fixed frequency (1 Hz), measure storage (G') and loss (G'') moduli as a function of shear stress (1-1000 Pa) to determine the yield stress (point where G' = G'').

- Printability Verification: A filament extruded through a nozzle should maintain its shape without spreading or breaking. The ink is deemed printable if G' > G'' at low shear stresses and demonstrates a rapid recovery of G' after the cessation of high shear.

Protocol 2: DIW Printing and Post-Processing of a Porous Bioceramic Scaffold

This protocol covers the printing, post-printing stabilization, and sintering of a 3D porous lattice scaffold.

Materials:

- Characterized ceramic ink (from Protocol 1)

- DIW 3D printer with pneumatic extrusion system and cooled print bed (4°C)

- Nozzle (conical, 410 µm inner diameter)

- Crosslinking bath (100 mM CaCl₂)

- Lyophilizer (Freeze-dryer)

- High-temperature furnace

Methodology:

- Printer Setup: Load the ink into a syringe barrel, attach the nozzle, and mount onto the printer. Set the print bed temperature to 4°C to enhance the structural stability of the Pluronic-based ink.

- Printing Parameters: Define a 0/90° lattice structure with a center-to-center filament spacing of 800 µm and a layer height of 300 µm. Optimize parameters:

- Pressure: 350 kPa (calibrated for consistent extrusion).

- Print Speed: 8 mm/s.

- Path Planning: Use continuous paths to minimize retractions.

- Layer-by-Layer Deposition: Print the scaffold directly into a supporting bath of 100 mM CaCl₂. The Ca²⁺ ions diffuse into the alginate, providing immediate ionic crosslinking to stabilize the structure.

- Post-Printing Crosslinking: After printing, immerse the entire scaffold in fresh CaCl₂ solution for 30 minutes to ensure complete crosslinking.

- Freeze-Drying: Rinse with deionized water and freeze at -80°C for 4 hours. Lyophilize for 24 hours to remove all water without pore collapse.

- Debinding & Sintering: Program the furnace with a thermal cycle:

- Ramp at 1°C/min to 600°C, hold for 2 hours (polymer burnout/debinding).

- Ramp at 5°C/min to 1250°C, hold for 2 hours (sintering).

- Cool at 3°C/min to room temperature.

- Characterization: Analyze sintered scaffolds for dimensional accuracy, porosity (via micro-CT), phase composition (XRD), and compressive strength (mechanical tester).

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for DIW of Bioceramics

| Item | Function in DIW Process |

|---|---|

| Hydroxyapatite (HA) Powder | Primary bioactive ceramic phase; provides osteoconductivity and chemical similarity to bone mineral. |

| Tricalcium Phosphate (TCP) Powder | Bioresorbable ceramic phase; tunes degradation rate and ionic release profile of the composite scaffold. |

| Sodium Alginate | Natural polysaccharide; provides viscosity and enables ionic crosslinking (e.g., with Ca²⁺) for green body strength. |

| Pluronic F-127 | Thermo-responsive triblock copolymer; acts as a rheological modifier to impart shear-thinning and yield-stress behavior for printability. |

| Gellan Gum / Xanthan Gum | Alternative polysaccharide thickeners; used to enhance viscoelasticity and shape retention of aqueous ceramic pastes. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | Water-soluble synthetic polymer; often used as a binder to improve particle cohesion and green strength before sintering. |

| Dispersants (e.g., TMAH, Darvan C) | Prevent particle agglomeration in the ink, ensuring homogeneity and smooth extrusion. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) Solution | Ionic crosslinker for alginate-containing inks; rapidly stabilizes extruded filaments post-deposition. |

| Customizable DIW Printer | Pneumatic or screw-driven extrusion system with temperature control, enabling precise deposition of high-viscosity pastes. |

Diagrams

Title: DIW Bioceramic Scaffold Fabrication Workflow

Title: DIW Experiment Validation Loop

Within the thesis on 3D printed bioceramic scaffolds, Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) is examined as a powder bed fusion technique capable of fabricating complex, porous geometries from ceramic powders without organic binders. This technique is pivotal for creating patient-specific, load-bearing bone scaffolds with controlled micro-architecture to promote osteoconduction and osseointegration.

Table 1: Typical SLS Process Parameters for Common Bioceramic Powders

| Material | Particle Size (µm) | Laser Power (W) | Scan Speed (mm/s) | Layer Thickness (µm) | Pre-heat Temp (°C) | Key Outcome (Porosity % / Strength MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxyapatite (HA) | 5-20 | 10-15 | 100-200 | 50-100 | 80-120 | 40-60% / 5-12 MPa |

| Beta-Tricalcium Phosphate (β-TCP) | 10-30 | 12-18 | 150-250 | 50-100 | 100-140 | 45-65% / 4-10 MPa |

| HA/β-TCP Biphasic | 10-25 | 12-16 | 120-220 | 50-100 | 90-130 | 50-70% / 6-15 MPa |

| Alumina (Al₂O₃) | 1-10 | 20-40 | 50-150 | 20-50 | 150-200 | 30-50% / 20-40 MPa |

| Zirconia (3Y-TZP) | 0.1-1.0 | 25-50 | 100-200 | 20-40 | 150-250 | 20-40% / 50-100 MPa |

Table 2: Post-Processing Parameters for SLS-Fabricated Bioceramic Scaffolds

| Post-Process Step | Temperature Profile | Atmosphere | Duration | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Debinding (if binder used) | 1°C/min to 450°C, hold 2h | Air | ~8 hours | Remove organic components |

| Sintering | 5°C/min to 1200-1350°C, hold 2h | Air/Vacuum | ~10 hours | Densify ceramic, achieve final strength |

| Pressure-Assisted Sintering (Hot Isostatic Pressing) | 1100-1300°C, 100-200 MPa | Argon | 1-3 hours | Eliminate residual porosity, enhance mechanical properties |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: SLS Fabrication of Porous β-TCP Scaffold Objective: To fabricate a porous β-TCP scaffold with interconnected pores of ~500 µm.

- Powder Preparation: Sieve commercially available β-TCP powder to achieve a particle size distribution of 10-30 µm. Dry in an oven at 120°C for 4 hours to remove moisture.

- Machine Setup: Preheat the powder bed chamber of the SLS system (e.g., EOSINT M 280 modified for ceramics) to 110°C to reduce thermal gradients.

- Parameter Setting: Load the following parameters into the machine software: Laser Power = 14 W, Scan Speed = 180 mm/s, Hatch Spacing = 80 µm, Layer Thickness = 75 µm.

- Build Process: Spread the first powder layer using a recoating blade. The laser sinters the cross-sectional pattern per the scaffold's 3D model (STL file). The build platform lowers by one layer thickness, and the process repeats.

- Cooling & Recovery: After completion, allow the part cake to cool slowly inside the build chamber under inert atmosphere (N₂) for 6-8 hours. Carefully excavate the green part from the unsintered powder bed.

Protocol 2: Post-Sintering and Characterization Objective: To densify the SLS green part and evaluate its properties.

- Thermal Post-Processing: Place the green scaffold in an alumina crucible. Sinter in a high-temperature furnace using the following profile: ramp at 5°C/min to 1250°C, hold for 2 hours, cool at 3°C/min to room temperature.

- Architectural Analysis: Scan the sintered scaffold using micro-computed tomography (µCT). Reconstruct 3D model. Calculate total porosity, interconnectivity, and pore size distribution using analysis software (e.g., CTAn).

- Mechanical Testing: Perform uniaxial compression testing (ASTM C773) on cube-shaped samples (n=5) using a universal testing machine at a crosshead speed of 0.5 mm/min. Record compressive strength and modulus.

- Biological Assessment (In Vitro): Sterilize scaffolds by autoclaving. Seed with human osteoblast-like cells (SaOS-2) at a density of 50,000 cells/scaffold. Culture in osteogenic media. Assess cell viability (AlamarBlue assay), proliferation (DNA content), and differentiation (ALP activity) at days 1, 7, and 14.

Visualizations

Title: SLS Ceramic Scaffold Fabrication Workflow

Title: SLS Parameter Effects on Scaffold Properties

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for SLS of Bioceramic Powders

| Item | Function & Rationale | Example Product/ Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Ceramic Powder | Base material for scaffold fabrication. High-purity, controlled particle size and flowability are critical for consistent layering and sintering. | Hydroxyapatite powder, >99% purity, D50 = 15 µm (Sigma-Aldrich 04238) |

| Flow Aid (Optional) | Improves powder spreadability in the SLS bed, crucial for thin, uniform layers. | Fumed silica (Aerosil R812), added at 0.1-0.5 wt% |

| Post-Sintering Etchant | Removes surface impurities or reveals microstructure for SEM imaging. | Dilute Hydrofluoric Acid (1-5% HF) for silica-containing ceramics; Phosphoric Acid for others. |

| Cell Culture Media for In Vitro Test | Provides nutrients for culturing osteoblasts on scaffolds to assess biocompatibility. | α-MEM, supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% Pen/Strep, 50 µg/mL Ascorbic Acid, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate. |

| Live/Dead Viability Stain | Fluorescently labels live (green) and dead (red) cells on the scaffold to visually assess cytocompatibility. | Thermo Fisher Scientific L3224 (Calcein AM / Ethidium homodimer-1) |

| µCT Contrast Agent | Enhances soft tissue/bone ingrowth contrast in scaffolds for in vivo studies. | Gold Nanoparticles or Iodine-based agents (e.g., Viact) for pre-implantation soaking. |

Application Notes in Bioceramic Scaffold Fabrication

Binder Jetting (BJ) is an additive manufacturing process where a liquid binding agent is selectively deposited to join powder particles layer-by-layer. In the context of bioceramic scaffolds for bone tissue engineering and drug delivery, this technique offers unique advantages for creating complex, porous structures without the need for support materials and with relatively high production speeds.

Key Applications:

- Patient-Specific Bone Implants: Fabrication of customized, porous calcium phosphate (e.g., hydroxyapatite, tricalcium phosphate) scaffolds from patient CT data.

- Combinatorial Drug Delivery Devices: Creation of scaffolds with spatially controlled porosity to enable localized, multi-drug release kinetics.

- In Vitro Tissue Models: Production of standardized, complex 3D bioceramic substrates for studying cell-scaffold interactions and osteogenesis.

Critical Process Parameters: The biomechanical and biological performance of the final scaffold is governed by several interlinked BJ parameters, summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Binder Jetting Parameters for Bioceramic Scaffolds

| Parameter | Typical Range/Type | Impact on Scaffold Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Powder Material | Hydroxyapatite (HA), β-Tricalcium Phosphate (β-TCP), Bioglass, Composites | Determines bioactivity, biodegradation rate, and base mechanical strength. |

| Powder Particle Size (D50) | 10 - 100 µm | Influences layer thickness, surface finish, green density, and minimum feature size. |

| Layer Thickness | 50 - 200 µm | Affects Z-axis resolution, stair-stepping effect, and total build time. |

| Binder Saturation | 70 - 130% | Critical for interlayer bonding and green strength. Low saturation causes delamination; high saturation causes pore clogging. |

| Drop Velocity/Spacing | 5-10 m/s; 20-80 µm | Controls binder line width, penetration depth, and dimensional accuracy. |

| Post-Processing: Sintering Temperature | 1100 - 1300°C for HA/TCP | Dictates final density, crystallinity, mechanical strength (compressive strength: 2-50 MPa), and shrinkage (15-30%). |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Porous β-TCP Scaffold for Osteogenesis Studies

Objective: To manufacture a reproducible, porous β-TCP scaffold with defined macro-architecture for in vitro osteoblast culture.

Materials & Reagents:

- Powder: β-Tricalcium phosphate powder (D50: 45 µm).

- Binder: Deionized water-based polymeric binder (2% wt PVA).

- Equipment: Commercial binder jetting 3D printer (e.g., ExOne, Voxeljet), sintering furnace.

Methodology:

- Powder Preparation: Dry the β-TCP powder at 80°C for 12 hours to remove moisture. Sieve to ensure uniform particle distribution.

- Printer Setup: Load the powder into the feed reservoir. Fill the print head with the prepared binder. Set the build platform.

- Digital Design: Load the scaffold model (e.g., 10x10x5 mm cube with orthogonal 500 µm pores) in .STL format into the printer software.

- Parameter Setting: Configure the following build parameters: Layer thickness: 75 µm, Binder saturation: 90%, Roller speed: 100 mm/s, Print head speed: 300 mm/s, Drying time between layers: 5 s.

- Printing: Initiate the build. The process alternates between spreading a powder layer and selectively jetting the binder according to the slice data.

- Depowdering: After build completion, carefully remove the "green" part from the powder bed using brushes and compressed air. Recover unbound powder for recycling.

- Curing: Place the green scaffold in an oven at 180°C for 2 hours to cure the binder.

- Sintering: Sinter in a high-temperature furnace using the following profile: Ramp at 3°C/min to 600°C (binder burnout), hold for 1 hour, then ramp at 5°C/min to 1250°C, hold for 2 hours, then slow cool to room temperature.

Expected Outcome: A sintered, mechanically stable β-TCP scaffold with interconnected porosity, suitable for subsequent cell seeding experiments.

Protocol 2: Fabrication of a Dual-Drug-Loaded Bioceramic Scaffold

Objective: To create a hydroxyapatite scaffold with spatially distinct compartments loaded with different therapeutic agents (e.g., an antibiotic and a growth factor).

Materials & Reagents: As Protocol 1, plus: Hydroxyapatite powder, Model drug 1 (e.g., Vancomycin), Model drug 2 (e.g., BMP-2 simulant), Functionalized binder solutions.

Methodology:

- Binder Functionalization: Prepare two separate binder solutions. Dope Binder A with 5 mg/ml of Drug 1. Dope Binder B with 0.1 mg/ml of Drug 2 in a stabilizing buffer.

- Digital Design: Create a scaffold model with two distinct, interdigitated geometric regions (Region A and Region B).

- Multi-Binder Printing: Utilize a printer with multiple print heads or a single head with flushing capability. Assign Binder A to Region A and Binder B to Region B in the print file.

- Printing & Post-Processing: Execute the print as in Protocol 1, with careful attention to prevent cross-contamination of binders. Perform depowdering, curing, and sintering (Note: sintering will degrade most protein-based drugs; for heat-labile agents, a post-printing infiltration method post-sintering is required).

- Characterization: Perform HPLC or ELISA on crushed samples from each region to confirm localized drug presence and measure loading efficiency.

Diagrams

Binder Jetting Scaffold Fabrication Workflow

Process Parameters Determine Scaffold Outcome

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Binder Jetting Bioceramics

| Item | Function in Research Context | Typical Specification/Example |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium Phosphate Powders | The base biomaterial providing osteoconductivity. | Hydroxyapatite (Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2), β-Tricalcium Phosphate (β-Ca3(PO4)2); Purity >98%, D50: 20-80 µm. |

| Aqueous Polymeric Binder | Temporarily bonds powder particles; burned out during sintering. | 1-5% w/v Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) or Polyethyleneglycol (PEG) in deionized water. |

| Functionalized Binder Solution | Enables direct integration of bioactive molecules during printing. | Binder doped with antibiotics (e.g., Gentamicin) or suspended growth factor carriers (e.g., gelatin microparticles). |

| Debinding & Sintering Furnace | Removes organic binder and sinters ceramic particles to achieve final strength. | Programmable furnace with oxidizing atmosphere (air), capable of reaching 1400°C with controlled ramp rates. |

| Architectural Design Software | Enables design of controlled porous architectures (gyroids, channels) for biological studies. | CAD (e.g., SOLIDWORKS) or implicit modeling software (e.g., nTopology). |

| Porosity Measurement Kit | Quantifies the porous structure critical for cell invasion and vascularization. | Mercury Intrusion Porosimeter or Micro-CT scanner with analysis software. |

| Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) | Assesses in vitro bioactivity by measuring apatite formation on scaffold surface. | Ion concentration similar to human blood plasma, pH 7.4, prepared per Kokubo protocol. |

Within the context of advancing fabrication techniques for 3D-printed bioceramic scaffolds, post-processing is a critical determinant of final material properties. Debinding and sintering are indispensable steps that transform a green body from a polymer-ceramic composite into a dense, mechanically competent, and biocompatible ceramic structure. These protocols directly influence the scaffold's phase purity, grain size, porosity, density, and ultimate biomechanical performance.

Key Quantitative Parameters in Post-Processing

Table 1: Common Debinding & Sintering Parameters for Bioceramics

| Parameter | Typical Range/Value for β-TCP/HA | Impact on Final Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Debinding Ramp Rate | 0.5 – 2 °C/min | Controls polymer burnout rate; too fast causes cracking/bloating. |

| Debinding Hold (Soak) | 400 – 600 °C for 1 – 4 hours | Ensures complete organic removal. Residual carbon can contaminate ceramic. |

| Sintering Temperature | HA: 1100 – 1300 °C; β-TCP: 1000 – 1150 °C; Composite: Tailored between ranges | Dictates phase stability, density, and grain growth. Higher temps increase density but may degrade phases or cause over-sintering. |

| Sintering Hold Time | 1 – 6 hours | Longer times increase density and grain size, potentially reducing strength if grains become too large. |

| Heating/Cooling Rate | 2 – 5 °C/min during critical phase transitions | Minimizes thermal stresses and cracking. |

| Atmosphere | Air (for HA), Dry Ar/N₂ (for TCP to prevent decomposition) | Prevents unwanted phase transformations (e.g., HA to α-TCP) or reduction reactions. |

| Final Density | >95% theoretical density (often 98-99% for load-bearing applications) | Directly correlates with compressive strength and modulus. |

| Final Grain Size | 0.5 – 5 µm (target sub-micron to low micron for optimal strength) | Smaller grains generally improve mechanical strength via Hall-Petch relationship. |

| Compressive Strength | Dense HA/β-TCP: 80 – 150 MPa; Porous Scaffolds (50-70% porosity): 2 – 20 MPa | Must match target anatomical site (e.g., trabecular bone: 2-12 MPa). |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Thermal Debinding of 3D Printed Bioceramic Green Bodies

Objective: To safely and completely remove organic binders/plasticizers without inducing defects. Materials: As-synthesized 3D printed green body (e.g., HA/polymer composite), tube furnace with programmable controller, alumina crucible or setters, fume extraction. Procedure:

- Preparation: Place the green body on an alumina setter powder (e.g., alumina powder) inside a crucible to support the structure and absorb any potential polymer residues.

- Furnace Loading: Position the crucible in the uniform hot zone of the furnace.

- Thermal Cycle Programming:

- Ramp 1: Heat from room temperature (RT) to 300°C at 1°C/min.

- Hold 1: Dwell at 300°C for 60 minutes to allow slow volatilization of low-molecular-weight organics.

- Ramp 2: Heat from 300°C to 550°C at 0.5°C/min. Critical: This slow ramp through the major polymer decomposition range (350-500°C) is essential.

- Hold 2: Dwell at 550°C for 120 minutes to ensure complete burnout.

- Cooling: Furnace cool to <100°C at 3°C/min.

- Post-Debinding: Carefully remove the "brown" body. It will be fragile but polymer-free. Characterize weight loss (should match theoretical binder content ±2%).

Protocol 2: Sintering of β-Tricalcium Phosphate (β-TCP) Scaffolds

Objective: To achieve a high-density, phase-pure β-TCP scaffold with controlled microstructure. Materials: Debinded β-TCP brown body, high-temperature furnace, platinum foil or alumina crucible, dry argon gas supply. Procedure:

- Preparation: Place the brown body on a piece of platinum foil (or in an alumina crucible with matching powder bed) to prevent reaction with the shelf.

- Furnace Sealing & Purging: Seal the furnace and purge with dry argon for at least 30 minutes prior to heating to establish an inert atmosphere. Maintain a low positive gas flow throughout the cycle.

- Thermal Cycle Programming:

- Ramp 1: Heat from RT to 900°C at 3°C/min.

- Ramp 2: Heat from 900°C to the target sintering temperature (e.g., 1120°C) at 2°C/min.

- Hold: Dwell at 1120°C for 4 hours.

- Cooling: Cool to 800°C at 3°C/min, then furnace cool to RT.

- Post-Sintering Analysis: Characterize phase composition via XRD (ensure no transformation to α-TCP), measure bulk density via Archimedes' method, and evaluate microstructure via SEM.

Diagram Title: Post-Processing Workflow & Property Evolution for Bioceramics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Debinding & Sintering Experiments

| Item Name | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Programmable Tube Furnace | Enables precise control of temperature ramps, holds, and atmospheres. Critical for reproducibility of thermal protocols. |

| Alumina Crucibles/Setters | High-temperature stable ceramicware to hold samples. Inert to most bioceramics and prevents fusion to furnace elements. Use with alumina powder for bedding. |

| Platinum Foil | Inert supporting material for sintering sensitive phases (e.g., TCP) where even alumina may cause minor contamination at high temperatures. |

| Dry Inert Gas Cylinder | Source of argon or nitrogen for creating non-oxidizing/reducing atmospheres to prevent phase decomposition (e.g., β-TCP to α-TCP). |

| Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA) | Critical for protocol development. Used to determine the exact temperature profile of binder burnout, informing optimal debinding ramp and hold temperatures. |

| High-Temperature Sintering Furnace | Capable of reaching >1400°C with uniform hot zone (±5°C) for densifying calcium phosphates and other bioceramics. |

| Alumina Powder (99.8%) | Used as a sacrificial bedding powder to support fragile brown bodies and absorb any residual organics during debinding. |

Diagram Title: Sintering Parameter Effects on Final Scaffold Properties

Meticulously optimized debinding and sintering protocols are non-negotiable for translating 3D-printed bioceramic green bodies into scaffolds with reliable and optimal final properties. The interplay between temperature, time, and atmosphere must be rigorously controlled based on the specific ceramic chemistry (e.g., HA vs. TCP) and the intended scaffold architecture. The protocols and data frameworks provided here serve as a foundational guide for researchers aiming to achieve reproducible, high-performance bioceramic scaffolds for bone tissue engineering and drug delivery applications.

Overcoming Fabrication Hurdles: Troubleshooting and Optimizing Print Fidelity & Scaffold Performance

Within the research on fabrication techniques for 3D-printed bioceramic scaffolds, achieving structural fidelity and mechanical integrity is paramount for biomedical applications such as bone tissue engineering and drug delivery systems. Common print defects—cracking, warping, and poor resolution—directly compromise scaffold porosity, mechanical strength, and biological functionality. This document details the causes and presents targeted experimental protocols to mitigate these defects, framed within a bioceramic (e.g., hydroxyapatite, β-tricalcium phosphate) extrusion-based printing context.

Defect Analysis, Causes, and Quantitative Data

Table 1: Summary of Common Bioceramic Print Defects, Causes, and Measured Impacts

| Defect | Primary Causes | Key Measurable Impact on Scaffolds | Typical Quantitative Range (From Literature) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cracking | Rapid drying-induced stress, binder-powder mismatch, excessive layer height, poor interlayer adhesion. | Reduced compressive strength, increased brittleness, micro-crack propagation. | Strength reduction: 40-70%. Crack density increase: 2-5x. |

| Warping | Non-uniform thermal gradients, high residual stress, poor bed adhesion, excessive shrinkage. | Dimensional inaccuracy (>200µm deviation), loss of bottom-layer porosity, delamination. | Warpage displacement: 0.5-3 mm. Bed detachment rate: 20-50%. |

| Poor Resolution | Nozzle abrasion/diameter increase, paste rheology instability, incorrect printing parameters (speed, pressure). | Loss of pore architecture (pore size deviation >50µm), reduced surface area for cell attachment. | Feature blurring: 100-300 µm. Pore size error: ±15-30%. |

Experimental Protocols for Defect Mitigation

Protocol 3.1: Assessing and Optimizing Paste Rheology to Prevent Cracking & Poor Resolution

Objective: To formulate a bioceramic paste with viscoelastic properties that minimize shear-thinning and promote shape retention. Materials: Bioceramic powder (e.g., Hydroxyapatite, <50µm), Pluronic F-127 or Alginate binder, Deionized water, Rheometer, Syringe extruder. Procedure:

- Paste Preparation: Prepare pastes with varying solid loadings (e.g., 40, 45, 50 vol%) and binder concentrations (e.g., 3, 5, 7 wt%).

- Rheological Characterization: Using a parallel-plate rheometer, measure:

- Static Yield Stress: Apply a controlled stress ramp (0.1-1000 Pa) to determine the stress required to initiate flow.

- Dynamic Viscosity: Perform a shear rate sweep (0.1-100 s⁻¹) to assess shear-thinning behavior.

- Storage/Loss Modulus (G'/G''): Conduct an amplitude sweep at 1 Hz to quantify elastic (G') and viscous (G'') components.

- Printability Assessment: Extrude each formulation through the target nozzle (e.g., 410µm) at constant pressure. Evaluate filament continuity and shape fidelity.

- Cracking Analysis: Print 10-layer lattice structures. After drying (37°C, 24h), inspect under optical microscope for cracks. Quantify crack density (cracks/mm²).

Protocol 3.2: Protocol for Minimizing Warping via Controlled Drying and Bed Adhesion

Objective: To implement a controlled drying environment and optimize first-layer adhesion to prevent warping and delamination. Materials: Heated print bed, Humidity-controlled enclosure, Build surface (polypropylene tape, sandblasted glass), Contact angle goniometer. Procedure:

- Surface Energy Modification: Treat the build surface with oxygen plasma for 2 minutes. Measure the water contact angle pre- and post-treatment to confirm increased hydrophilicity.

- Adhesion Test: Print single-layer squares (20x20mm) with the optimized paste from Protocol 3.1. Test conditions: (A) Untreated bed, room temp; (B) Plasma-treated bed, room temp; (C) Plasma-treated bed, 40°C.

- Controlled Drying: Immediately after printing a multi-layer scaffold, place it in an environmental chamber set to 25°C and 70% relative humidity for a 12-hour "slow-drying" stage.

- Warpage Measurement: After full drying, use a confocal laser scanner or digital micrometer to measure the vertical displacement of each corner from the theoretical plane. Warpage is defined as the maximum deviation (in µm).

Protocol 3.3: Calibrating Printing Parameters for Optimal Resolution

Objective: To establish a correlation between printing parameters and feature resolution, minimizing blurring and pore size error. Materials: High-precision extrusion printer, Nozzles of various diameters (e.g., 250, 410, 600 µm), Calibration lattice model. Procedure:

- Parameter Matrix: Define a matrix of printing speeds (10, 15, 20 mm/s) and extrusion multipliers (90, 100, 110%) for a fixed nozzle size.

- Print Calibration Structures: Print a standard lattice (e.g., 0/90° infill, 500µm strand spacing) for each parameter set.

- Image Acquisition & Analysis: Use a digital microscope to capture top-down images. Process images with ImageJ software:

- Measure actual strand width at 10 points.

- Calculate the ratio of actual/predicted strand width (Resolution Fidelity Ratio, RFR). Target RFR = 1.

- Measure the pore size in X and Y directions.

- Nozzle Wear Assessment: Weigh printed structures and compare to theoretical paste mass. A consistent >10% under-extrusion may indicate nozzle wear (abrasion). Inspect nozzle bore under microscope.

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Bioceramic Print Optimization Workflow (94 chars)

Diagram 2: Root Cause and Solution Pathway (85 chars)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Bioceramic Scaffold Print Defect Research

| Item | Function in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Hydroxyapatite (HA) Powder (< 50µm) | Primary bioceramic material; particle size distribution directly affects paste rheology and sintering. | High purity (>99%), controlled particle morphology (spherical preferred) to reduce nozzle clogging. |

| Pluronic F-127 | Thermogelling sacrificial binder; imparts shear-thinning behavior and temporary green strength. | Concentration critically determines yield stress. Allows for room-temperature extrusion. |

| Sodium Alginate | Ionic cross-linking binder; enhances filament elasticity and shape retention post-extrusion. | Cross-linking kinetics (via Ca²⁺) must be tuned to prevent nozzle clogging or weak strands. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) Bed Coating | Promotes first-layer adhesion for warping prevention; water-soluble for easy part removal. | Molecular weight and concentration affect adhesion strength and dissolution rate. |

| Glycerol / Ethylene Glycol | Humectant plasticizer; slows water evaporation from paste, reducing drying-induced cracking. | Optimal dosage balances crack reduction with maintaining structural rigidity during printing. |

| Deionized Water | Solvent for binder system; affects paste viscosity and particle dispersion. | pH and ionic content can influence binder performance and paste stability. |

Within the broader thesis on 3D printed bioceramic scaffolds for bone tissue engineering and drug delivery, the formulation of the ceramic ink or paste is the foundational step. Optimized rheology is critical for achieving reliable extrusion through fine nozzles (printability) and maintaining the designed shape post-deposition (shape fidelity). This balance is governed by key rheological parameters: yield stress (τ_y), storage modulus (G'), loss modulus (G''), and viscosity (η). For bioceramics like hydroxyapatite (HA), beta-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP), or bioactive glass, formulations are typically aqueous-based pastes using biocompatible polymers as rheological modifiers.

Key Rheological Targets for Bioceramic Inks:

- Extrudability: Requires a low apparent viscosity under high shear stress (in the syringe and nozzle) to facilitate flow. This is often achieved with shear-thinning behavior.

- Shape Fidelity: Requires a rapid recovery of a high elastic modulus (G') and yield stress after extrusion to resist deformation under gravitational and capillary forces.

- Structural Integrity: For layer-by-layer fabrication, the paste must possess sufficient zero-shear viscosity and yield stress to support subsequent layers without collapsing.

Table 1: Exemplary Rheological Properties for Bioceramic Pastes (Recent Studies)

| Bioceramic System (Solid Loading) | Rheological Modifier | Yield Stress (τ_y, Pa) | Apparent Viscosity at 100 s⁻¹ (Pa·s) | G' at 1 Hz (Pa) | Reference Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-TCP (60 wt%) | Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose (HPMC) | 450 ± 35 | 120 ± 10 | 5,200 ± 400 | Scaffolds with 300 µm filaments |

| HA (55 wt%) | Alginate (Cross-linked with Ca²⁺) | 680 ± 50 | 95 ± 8 | 8,500 ± 600 | High-fidelity, complex gyroid structures |

| Bioactive Glass (45S5, 40 vol%) | Pluronic F-127 | 150 ± 20 | 25 ± 5 | 1,800 ± 200 | Sacrificial plotting for macroporous networks |

| HA/β-TCP Composite (50 wt%) | Chitosan + Glycerophosphate | 320 ± 25 | 80 ± 7 | 4,100 ± 350 | Thermoresponsive gel for cell encapsulation |

Table 2: Printability & Shape Fidelity Assessment Metrics

| Metric | Definition | Target Range for Bioceramics | Measurement Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extrusion Pressure | Pressure required to maintain constant flow rate. | 300 - 800 kPa (dependent on nozzle size) | Recorded via pressure sensor on dispensing system. |

| Shape Fidelity Ratio (SFR) | (Area of Printed Filament) / (Area of Nozzle Orifice). | 0.9 - 1.1 (Close to 1 is ideal) | Optical microscopy + image analysis (e.g., ImageJ). |

| Filament Collapse Angle | Angle of deformation of an overhanging filament. | < 5° | Side-view imaging of a spanning filament. |

| Layer Stacking Ability | Maximum number of layers without significant deformation. | > 10 layers | Printing a simple pillar structure. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Rheological Characterization of Bioceramic Paste

- Objective: To measure yield stress, viscoelastic moduli, and shear-thinning behavior.

- Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" (Table 3). Prepared bioceramic paste.

- Equipment: Rotational rheometer with parallel plate geometry (plate diameter: 20-25 mm), gap setting tool, solvent trap.

Method:

- Loading: Carefully load the paste onto the lower Peltier plate, ensuring no air bubbles. Set the gap to ~1.0 mm. Trim excess material.

- Yield Stress Determination (Oscillatory Stress Sweep):

- Mode: Oscillation.

- Fixed frequency: 1 Hz.

- Applied shear stress: Log scale from 0.1 Pa to 1000 Pa.

- Analysis: Identify τ_y as the stress where G' drops sharply (crossover with G'' or deviation from linear viscoelastic region).

- Viscoelastic Profile (Oscillatory Frequency Sweep):

- Mode: Oscillation.

- Applied stress: Within the linear viscoelastic region (e.g., 10 Pa, as determined in step 2).

- Frequency range: 0.1 Hz to 100 Hz.

- Analysis: Record G' and G''. For shape fidelity, G' should be greater than G'' (solid-like behavior) across most frequencies.

- Shear-Thinning Behavior (Steady State Shear Ramp):

- Mode: Flow.

- Shear rate: Log scale from 0.01 s⁻¹ to 500 s⁻¹.

- Analysis: Plot viscosity vs. shear rate. A strong shear-thinning profile is ideal. Note apparent viscosity at a shear rate representative of extrusion (~100 s⁻¹).

Protocol 2: Direct Ink Writing (DIW) Printability Assessment

- Objective: To empirically evaluate extrusion reliability and shape fidelity.

- Materials: Prepared paste, 3D bioplotter or extrusion system, syringe barrels, conical nozzles (e.g., 200-410 µm), substrate (glass or petri dish).