Engineering the Future of Medicine: Functionalizing Biomaterials with Recombinant DNA Technology

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of recombinant DNA technology in the functionalization of advanced biomaterials.

Engineering the Future of Medicine: Functionalizing Biomaterials with Recombinant DNA Technology

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of recombinant DNA technology in the functionalization of advanced biomaterials. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of designing recombinant proteins like collagen and elastin-like polypeptides for tissue scaffolding. It delves into methodological applications in areas such as cartilage regeneration and drug delivery, examines cutting-edge troubleshooting and optimization strategies including AI-driven culture medium design, and validates these approaches through analysis of FDA-approved products and commercial market trends. The synthesis of these insights highlights the immense potential of recombinant biomaterials to revolutionize regenerative medicine and therapeutic development.

The Building Blocks of Innovation: Core Principles of Recombinant DNA in Biomaterial Design

Defining Recombinant DNA Technology and Its Relevance to Biomaterials

Recombinant DNA (rDNA) technology involves using enzymes and various laboratory techniques to manipulate and isolate DNA segments of interest [1]. This foundational method allows scientists to combine (or splice) DNA from different species or to create genes with new functions [1]. The resulting copies, known as recombinant DNA, are typically propagated in bacterial or yeast cells, which copy the engineered DNA along with their own genetic material during cell division [1]. The technology was invented in 1973 by Paul Berg, Herbert Boyer, Annie Chang, and Stanley Cohen [2], and has since revolutionized biological research, medicine, and biotechnology.

A fundamental goal of genetics facilitated by rDNA technology is the isolation, characterization, and manipulation of individual genes [3]. Although isolating a sample of DNA from a collection of cells is relatively straightforward, finding a specific gene within this DNA sample was historically challenging [3]. Recombinant DNA technology has solved this problem by making it possible to isolate one gene or any other segment of DNA, enabling researchers to determine its nucleotide sequence, study its transcripts, mutate it in highly specific ways, and reinsert the modified sequence into a living organism [3].

Fundamental Principles and Techniques

Core Methodology

Recombinant DNA technology comprises altering genetic material outside an organism to obtain enhanced and desired characteristics in living organisms or as their products [2]. This technology involves the insertion of DNA fragments from a variety of sources, having a desirable gene sequence via an appropriate vector [2]. The fundamental process involves several key steps:

- DNA Manipulation: Enzymatic cleavage is applied to obtain different DNA fragments using restriction endonucleases for specific target sequence DNA sites [2].

- Ligation: DNA ligase activity joins the fragments to fix the desired gene into a vector [2].

- Introduction to Host: The vector is then introduced into a host organism, which is grown to produce multiple copies of the incorporated DNA fragment in culture [2].

- Selection and Harvest: Finally, clones containing a relevant DNA fragment are selected and harvested [2].

DNA Cloning and Vectors

In biology, a clone is a group of individual cells or organisms descended from one progenitor, meaning the members of a clone are genetically identical [3]. The concept has been extended to recombinant DNA technology, which provides scientists with the ability to produce many copies of a single fragment of DNA, such as a gene, creating identical copies that constitute a DNA clone [3].

In practice, the procedure is carried out by inserting a DNA fragment into a small DNA molecule and then allowing this molecule to replicate inside a simple living cell such as a bacterium [3]. The small replicating molecule is called a DNA vector (carrier) [3]. The most commonly used vectors are:

- Plasmids: Circular DNA molecules that originated from bacteria [3]

- Viruses: Which can efficiently deliver genetic material [3]

- Yeast Cells: Eukaryotic systems that offer post-translational modifications [3]

Plasmids are particularly useful as they are not part of the main cellular genome, but can carry genes that provide the host cell with useful properties, such as drug resistance, mating ability, and toxin production [3]. They are small enough to be conveniently manipulated experimentally and can carry extra DNA that is spliced into them [3].

Table 1: Common Host Systems for Recombinant DNA Technology

| Host System | Examples | Advantages | Limitations | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial | Escherichia coli | Rapid growth, high cell concentrations, inexpensive substrates, well-characterized genome [4] | Limited post-translational modification capability [4] | Non-glycosylated proteins, basic research [4] |

| Yeast | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Eukaryotic model, post-translational modifications, large-scale production capability [4] | Glycosylation patterns may affect human serum half-life [4] | Insulin production, recombinant proteins [4] |

| Mammalian Cell Cultures | Chinese hamster ovary (CHO), human embryo kidney (HEK-293) | Appropriate post-translational modifications, human-like glycosylation patterns [4] | Higher cost, more complex culture requirements [4] | Glycosylated therapeutic proteins, complex biologics [4] |

Relevance to Biomaterials Research

Molecular Characterization of Biomaterial-Host Interactions

Molecular biology techniques enabled by rDNA technology play a fundamental role in biomaterials research by evidencing the influence of biomaterials on gene expression, protein synthesis, and cellular behaviors such as proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [5]. These results are inputs to establish biocompatibility and biofunctionality for biomaterials in different applications, including modulation of immune cells to regulate wound healing in response to an implant, or to promote tissue regeneration rather than a fibrotic outcome [5].

Techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), electrophoresis, and DNA sequencing enable researchers to analyze and manipulate genetic material, facilitating the development of biomaterials that integrate effectively with biological tissue [5]. For instance, genetic modifications can enhance cell receptivity to a specific biomaterial, improving the success of biomedical treatments [5]. Additionally, cell culture techniques play a crucial role in assessing biocompatibility by simulating biological environments and evaluating cellular responses to different materials, helping predict their behavior in vivo [5].

Biomaterial Functionalization via Genetic Engineering

Recombinant DNA technology enables the creation of active materials by genetically fusing a self-assembling protein to a functional protein [6]. These fusion proteins form materials while retaining the function of interest [6]. Key advantages of this approach include:

- Elimination of a separate functionalization step during materials synthesis [6]

- Uniform and dense coverage of the material by the functional protein [6]

- Stabilization of the functional protein [6]

This strategy can be used to incorporate peptides, protein domains, and full-length, folded proteins into a wide variety of protein-based materials [6]. The structure and function of the fused functional proteins are often preserved and improved due to reduced protease access and limited mobility [6]. This confined space surrounding the fused proteins hampers protein unfolding, resulting in prolonged enzymatic, signaling, and/or biological activities [6].

Table 2: Applications of Recombinant DNA Technology in Biomaterials Development

| Application Area | Specific Examples | Key Findings/Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue Engineering | Fusion proteins containing fibronectin domains, elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs), spider silk proteins [6] | Enhanced cell attachment, tunable mechanical properties, promoted tissue regeneration [6] |

| Neural Regeneration | Collagen, gelatin, chitosan, alginate, hyaluronan, silk fibroin, conductive polymers (polypyrrole, polythiophene) [7] | Supported nerve cell growth, electrical conductivity enhanced neurite outgrowth and nerve signal travel [7] |

| Drug Delivery | Protein-based biomaterials with fused functional domains [6] | Sustained and targeted release of therapeutic agents, improved stabilization of bioactive compounds [6] |

| Enzyme Immobilization | Functional enzymes fused to self-assembling protein domains [6] | Enhanced enzyme stability, reusability, and localized catalytic activity [6] |

| Biosensing | Fusion proteins incorporating binding domains or fluorescent proteins [6] | Specific detection of analytes, real-time monitoring capabilities [6] |

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Genetic Fusion of Functional Proteins to Self-Assembling Biomaterials

Principle: This protocol describes the creation of fusion proteins where a functional protein domain is genetically linked to a self-assembling protein domain to create bioactive materials [6].

Materials:

- DNA sequences encoding functional and self-assembling proteins

- Appropriate expression vector

- Restriction enzymes and DNA ligase

- Competent E. coli cells

- Protein purification reagents

- Cell culture materials for biocompatibility testing

Procedure:

- Gene Design: Identify and obtain DNA sequences for both the functional protein and self-assembling protein components [6].

- Vector Construction: Fuse the DNA sequences in-frame, typically with a short linker sequence (e.g., GGGS repeats) to prevent steric hindrance [6]. Clone into an appropriate expression vector.

- Transformation: Introduce the construct into competent E. coli or other suitable host cells [6].

- Protein Expression: Induce protein expression under optimized conditions.

- Purification: Purify the fusion protein using appropriate chromatographic methods.

- Material Formation: Induce self-assembly under predetermined buffer conditions.

- Characterization: Assess material properties (mechanical strength, porosity) and biological activity.

Technical Notes:

- Linker length and composition significantly impact function; test multiple variants [6].

- Fusion orientation (N-terminal vs. C-terminal) affects folding and activity [6].

- Monitor for inclusion body formation in bacterial systems; may require refolding protocols.

Protocol 2: Biomaterial-Mediated Neuronal Regeneration

Principle: This protocol utilizes recombinant DNA-derived biomaterials to support neuronal repair and regeneration, particularly using conductive polymers to enhance neurite outgrowth [7].

Materials:

- Conductive polymers (polypyrrole, polythiophene, polyaniline)

- Natural polymers (chitin, chitosan, collagen, alginate, gelatin)

- Primary neurons or neural stem cells

- Electrochemical setup for electrical stimulation

- Immunocytochemistry reagents for neuronal markers

Procedure:

- Scaffold Fabrication: Create 3D scaffolds using natural or synthetic polymers via electrospinning or 3D printing [7].

- Conductive Coating: Apply conductive polymers to scaffold surface [7].

- Sterilization: Sterilize scaffolds using appropriate methods (UV, ethanol, ethylene oxide).

- Cell Seeding: Seed neural stem cells or primary neurons onto scaffolds at optimal density.

- Electrical Stimulation: Apply controlled electrical stimulation using customized bioreactors [7].

- Assessment: Evaluate neurite outgrowth, alignment, and expression of neuronal markers.

- In Vivo Testing: Implant optimized scaffolds in appropriate animal models of neural injury.

Technical Notes:

- Conductivity levels must be optimized to support signaling without causing toxicity [7].

- Scaffold porosity should allow nutrient diffusion and cell infiltration [7].

- Mechanical properties should match native neural tissue.

Advanced Technologies and Future Directions

CRISPR-Based DNA Engineering

Recent advances in CRISPR-based DNA engineering have expanded capabilities for biomaterial functionalization [8]. CRISPR-Cas systems are RNA-guided elements that can integrate into DNA by base-pairing target protospacers with complementary CRISPR RNA spacers [8]. CRISPR-associated transposase (CAST) systems present a unique strategy for integrating large genetic elements into specific genomic loci without introducing double-strand breaks, relying solely on guide RNA for target recognition [8].

These systems enable accurate and efficient one-step insertion of foreign DNA into the target gene in vivo [8]. In various prokaryotic hosts, this method has demonstrated nearly complete insertion in Escherichia coli, enabling the stable integration of donor sequences up to approximately 15.4 kb with type I-F CAST and as much as 30 kb using type V-K variants [8]. While applications in mammalian cells are still developing, progress continues with engineered systems showing promise for future biomedical applications [8].

Recombinant Protein Production Challenges

Recombinant proteins are susceptible to undergoing chemical and physical changes during all production steps [4]. Common challenges include:

- Chemical Changes: Modifications of the primary structure, failure of amino acid incorporation, and post-translational modifications (glycosylation, phosphorylation, oxidation, etc.) [4]

- Physical Changes: Aggregation and denaturation processes involving tertiary and quaternary structures [4]

The true analytical challenge is the heterogeneity in recombinant protein expression alongside the numerous changes and degradation pathways that may occur during biological processes [4]. Regulatory considerations further complicate production, with agencies like the FDA, EMEA, and ANVISA requiring thorough characterization to assure quality, safety, and efficacy of recombinant drugs [4].

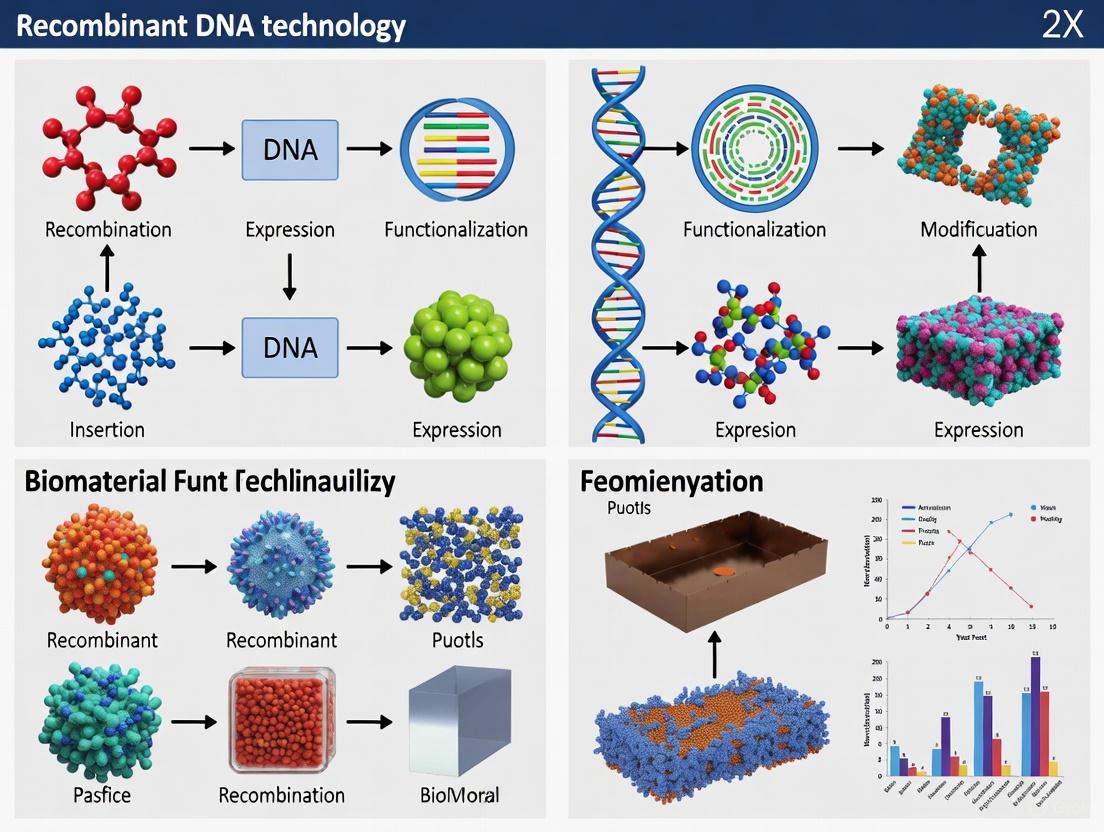

Diagram 1: Recombinant Protein Biomaterial Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key steps in creating functionalized biomaterials using recombinant DNA technology.

Diagram 2: Fusion Protein Design and Applications. This diagram illustrates the structure of genetically engineered fusion proteins and their applications in biomaterials.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Recombinant DNA Technology in Biomaterials

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Restriction Enzymes | EcoRI, BamHI, HindIII | Recognize specific DNA sequences and create precise cuts for gene insertion [2] |

| DNA Ligases | T4 DNA Ligase | Join DNA fragments by catalyzing phosphodiester bond formation [2] |

| Expression Vectors | Plasmids, bacteriophages, artificial chromosomes | Carry and replicate inserted DNA fragments in host cells [3] [4] |

| Host Systems | E. coli, S. cerevisiae, CHO cells | Provide cellular machinery for protein expression and replication [4] |

| Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance genes, fluorescence proteins | Enable identification and selection of successfully transformed cells [3] |

| Linker Sequences | (GGGGS)n, (EAAAK)n | Provide flexibility and prevent steric hindrance in fusion proteins [6] |

| Conductive Polymers | Polypyrrole, polythiophene, polyaniline | Enable electrical conductivity in neural tissue engineering scaffolds [7] |

| Natural Polymers | Collagen, chitosan, alginate, silk fibroin | Provide biocompatible scaffolding for tissue regeneration [7] |

| 4-Hydroxymethylphenol 1-O-rhamnoside | 4-Hydroxymethylphenol 1-O-rhamnoside, MF:C13H18O6, MW:270.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Methyldopa hydrochloride | 3-O-Methyldopa Hydrochloride|High-Purity Research Chemical | 3-O-Methyldopa hydrochloride is a key metabolite of L-DOPA. This product is for research use only (RUO) and is not intended for personal use. |

Recombinant DNA technology has evolved from a basic research tool to an indispensable technology for biomaterials development. By enabling precise manipulation of genetic material, it facilitates the creation of functionalized biomaterials with enhanced bioactive properties. The integration of rDNA technology with biomaterials science has accelerated progress in tissue engineering, drug delivery, neural regeneration, and biosensing.

Future directions will likely involve more sophisticated genetic engineering approaches, including advanced CRISPR systems [8] and more complex fusion protein designs [6]. As the field progresses, addressing challenges related to scalability, regulatory approval, and biological variability will be essential for translating these technologies into clinical applications. The convergence of recombinant DNA technology with biomaterials engineering continues to open new frontiers in regenerative medicine and therapeutic device development, promising innovative solutions to complex medical challenges.

The strategic application of recombinant proteins as scaffolding materials represents a significant advancement in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for three key recombinant proteins—collagen, elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs), and fibrin—focusing on their unique properties, fabrication methodologies, and specific applications in tissue regeneration. Within the broader context of recombinant DNA technology for biomaterial functionalization, these proteins offer tailored solutions for overcoming limitations associated with natural derivatives, including batch variability, immunogenicity, and pathogen transmission risks. The following sections provide a comparative analysis, detailed protocols, and practical resources to support researchers in leveraging these sophisticated biomaterials for advanced therapeutic development.

Recombinant Human Collagen

Recombinant human collagen (rhCol) is produced through heterologous expression systems, emulating the post-translational modifications seen in natural collagens, such as hydroxylation and glycosylation, thereby achieving a high degree of similarity to human collagen [9]. The characteristic triple-helical structure, composed of three polypeptide α-chains, provides structural integrity and regulatory cues for cellular behavior [9]. Among various types, recombinant human type III collagen (rhCol III) is particularly crucial for distensible tissues like blood vessels and skin, forming fine, elastic fibers that co-assemble with type I collagen and playing a vital role in early wound healing and scar quality [10].

Key Advantages and Applications

rhCol offers significant advantages over animal-derived collagen, including superior biocompatibility, controlled bioactivity, and elimination of zoonotic pathogen risks [9] [10]. Its applications are extensive in the tissue engineering field, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Applications of Recombinant Collagen in Tissue Engineering

| Application Area | Specific Uses | Key Benefits | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wound Healing & Skin Repair | Dressings, hydrogels, skin substitutes | Promotes re-epithelialization, improves scar quality (Type III), accelerates wound closure | [9] [10] |

| Bone & Cartilage Regeneration | Scaffolds combined with stem cells | Supports osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation, facilitates substantial new bone/cartilage formation in vivo | [9] |

| Vascular Engineering | Cell-seeded tubular scaffolds | Demonstrates ability to remodel into vascular grafts | [9] |

| Stroma Regeneration | 3D scaffolds for soft tissues | Supports cell proliferation and differentiation, creates favorable ECM microenvironment | [9] [10] |

Detailed Protocol: Fabrication of a Recombinant Collagen Hydrogel Scaffold for Skin Regeneration

This protocol describes the formation of a hydrogel scaffold from recombinant human Type III collagen, designed to promote a regenerative wound healing environment with reduced scarring.

Materials & Reagents:

- Recombinant Human Type III Collagen (rhCol III) Solution (3-5 mg/mL in 0.1% acetic acid)

- 10X Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Neutralization Solution (1M NaOH or 0.1M HEPES buffer, pH 8.0)

- Crosslinker (e.g., 10 mM EDC (1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) in deionized water)

- Cell Culture Media (DMEM/F12, optional for cellularization)

Procedure:

- Preparation: Pre-cool all reagents and equipment to 4°C. Keep the rhCol III solution on ice.

- Neutralization:

- Pipette 1 mL of rhCol III solution into a sterile vial on ice.

- Slowly add 100 µL of 10X PBS while gently stirring.

- Titrate the pH to 7.2-7.4 using the neutralization solution. The mixture will become viscous.

- Gelation:

- Transfer the neutralized collagen solution to the desired mold (e.g., multi-well plate).

- Incubate at 37°C for 30-60 minutes to form a stable hydrogel.

- Crosslinking (Optional for Enhanced Mechanical Strength):

- Carefully aspirate any residual liquid from the gelled scaffold.

- Add the EDC crosslinking solution to cover the hydrogel.

- Incubate at room temperature for 2-4 hours with gentle agitation.

- Rinse the crosslinked hydrogel 3-5 times with sterile PBS or DI water to remove residual crosslinker.

- Cell Seeding (Optional):

- Pre-condition the scaffold with cell culture media for at least 1 hour.

- Seed fibroblasts or keratinocytes onto the scaffold surface at a density of 1x10^5 cells/cm².

- Allow 2-4 hours for cell attachment before adding additional media.

Elastin-Like Polypeptides (ELPs)

Elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs) are biologically inspired, thermally responsive biopolymers derived from the repetitive hydrophobic domains of human tropoelastin [11] [12]. They are composed of short repeating pentapeptide motifs, most commonly VPGXG, where X is a "guest residue" that can be any amino acid except proline [11] [13]. This sequence confers a unique Inverse Temperature Transition (ITT) property: ELPs are soluble in aqueous solutions below a characteristic transition temperature (Tt) but undergo a reversible phase transition to form a coacervate (a highly viscous fluid) above their Tt [11] [12].

Key Advantages and Applications

ELPs are genetically encoded, allowing for exquisite control over their amino acid sequence, molecular weight, and, consequently, their Tt and mechanical properties [11] [12]. They are biocompatible, biodegradable, and non-immunogenic, making them excellent candidates for in vivo applications [11]. Their applications in tissue engineering are diverse.

Table 2: Applications of Elastin-Like Polypeptides in Tissue Engineering

| Application Area | Specific Uses | Key Benefits | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cartilage & Intervertebral Disc Repair | Injectable, crosslinkable hydrogels | Promotes chondrogenesis and stem cell differentiation; shear moduli can be tuned over several orders of magnitude | [11] |

| Drug Delivery | Micelles, vesicles, nanofibers | Thermally triggered drug release; enhances pharmacokinetics through self-assembly | [12] [13] |

| Injectable Depots | Sustained local therapy for cancer | Forms solid matrix in situ upon injection for prolonged local drug exposure | [12] |

Detailed Protocol: Creating an Injectable ELP Hydrogel for Cartilage Tissue Engineering

This protocol utilizes a lysine-containing ELP crosslinked with THPP to create a mechanically robust hydrogel suitable for encapsulating chondrocytes or stem cells.

Materials & Reagents:

- Lysine-containing ELP (e.g., ELP[V5K2-40], 20% w/v solution in PBS, stored at 4°C)

- Crosslinker Solution (β-[Tris(hydroxymethyl)phosphino]propionic acid, THPP, 100 mM in deionized water)

- Chondrocytes or Mesenchymal Stem Cells (in suspension, 10-50 x 10^6 cells/mL)

- Cell Culture Media (Chondrogenic media, optional)

Procedure:

- Preparation: Cool the ELP solution and PBS to 4°C. Pre-chill pipettes and tubes.

- Cell Mixing:

- Gently mix the cell suspension with the cold ELP solution to achieve a final ELP concentration of 10-15% w/v and the desired final cell density.

- Keep the cell-ELP mixture on ice at all times to prevent premature gelling.

- Crosslinking and Gelation:

- Add the THPP crosslinker to the cell-ELP mixture at a 1:1 molar ratio of THPP to lysine residues in the ELP. Mix quickly but gently.

- Immediately pipette the solution into the desired mold or inject it into the defect site.

- The gel will form within 5 minutes at 37°C [11].

- Post-Gelation Culture:

- Once gelled, carefully overlay the construct with pre-warmed chondrogenic media.

- Culture the cell-laden hydrogel, changing the media every 2-3 days.

Figure 1: Workflow for Injectable ELP Hydrogel Formation.

Recombinant Fibrin

Fibrin is the natural matrix protein formed during the blood coagulation cascade. It is generated through the enzymatic polymerization of fibrinogen (Fbg) by thrombin in the presence of Ca²⺠ions [14]. Fibrinogen is a 340 kDa glycoprotein that contains two primary Arginine-Glycine-Aspartic acid (RGD) integrin-binding sites, which mediate cell adhesion and signaling [14] [15]. Recombinant technologies are now enabling the production of human fibrinogen, overcoming the limitations of plasma-derived sources.

Key Advantages and Applications

Fibrin scaffolds are inherently bioactive, providing a natural provisional extracellular matrix that supports cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation [14] [15]. They are widely used in tissue engineering due to their excellent biocompatibility and ability to be processed into various forms like microspheres, nanofibers, and hydrogels [14]. Key applications include:

Table 3: Applications of Fibrin-Based Scaffolds in Tissue Engineering

| Application Area | Specific Uses | Key Benefits | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Regeneration | Scaffolds with stem cells and growth factors (e.g., BMP-2) | Supports osteogenic differentiation; TG2 crosslinking enhances matrix deposition and calcification | [15] |

| Nerve & Skin Conduits | Guides for nerve regeneration, wound dressings | High affinity for growth factors (VEGF, NGF, EGF); promotes vascularization and healing | [14] |

| Cell Delivery | Microcarriers for cell transplantation | 3D fibrous structure enables high cell seeding efficiency and uniform distribution | [14] |

Detailed Protocol: Fabrication of a Fibrin Scaffold for Bone Tissue Engineering with TG2-Modified Cells

This protocol describes the construction of a functional bone-like graft using a fibrin scaffold seeded with ectomesenchymal stem cells (EMSCs) overexpressing Transglutaminase 2 (TG2) to enhance matrix stability and osteogenesis [15].

Materials & Reagents:

- Fibrinogen (from rat or recombinant source, 20 mg/mL in PBS)

- Thrombin (from rat or recombinant source, 10 U/mL in 40 mM CaClâ‚‚ solution)

- TG2 gene-modified EMSCs (in single-cell suspension, 1x10^7 cells/mL)

- Osteogenic Media (DMEM/F12, 10% FBS, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 µg/mL L-ascorbic acid, 10 nM dexamethasone)

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation:

- Scaffold Polymerization:

- Mix the fibrinogen solution with the TG2-EMSC suspension in a 1:1 volume ratio. The final cell density in the construct will be 5x10^6 cells/mL.

- In a separate tube, add an equal volume of the thrombin/CaClâ‚‚ solution to the fibrinogen-cell mixture. Pipette up and down gently 2-3 times to mix.

- Quickly transfer the solution to a mold and incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes to form a stable fibrin gel.

- In Vitro Culture and Mineralization:

- Carefully overlay the polymerized scaffold with osteogenic media.

- Culture the constructs for up to 28 days, changing the media every 2-3 days.

- The overexpression of TG2 will cross-link secreted ECM proteins (fibronectin, collagen, OPN), leading to enhanced matrix deposition and subsequent calcification [15].

Comparative Analysis and Selection Guide

The choice of scaffolding protein depends on the specific requirements of the target tissue and application. The table below provides a direct comparison to guide material selection.

Table 4: Comparative Analysis of Key Recombinant Scaffolding Proteins

| Parameter | Recombinant Collagen | Elastin-Like Polypeptides (ELPs) | Recombinant Fibrin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Structure | Triple-helix (Gly-X-Y)n | Linear polymer (VPGXG)n | Fibrillar network from Fbg monomers |

| Key Mechanical Property | High tensile strength | High elasticity & extensibility | Viscoelasticity |

| Key Functional Feature | Innate cell binding sites | Thermally responsive (ITT) | Natural provisional matrix; RGD sites |

| Crosslinking Methods | Chemical (EDC), UV, Dehydrothermal | Chemical (THPP), Enzymatic (Transglutaminase) | Enzymatic (Thrombin), FXIII |

| Degradation Profile | Enzymatic (MMPs, Collagenases) | Enzymatic (Elastase, Cathepsins) | Enzymatic (Plasmin, Fibrinolysis) |

| Ideal Tissue Targets | Skin, Bone, Cartilage, Vasculature | Cartilage, Vascular grafts, Drug depots | Bone, Nerve, Skin, Cardiac tissue |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 5: Key Reagents for Working with Recombinant Scaffolding Proteins

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Prolyl 4-Hydroxylase (P4H) | Critical post-translational enzyme for recombinant collagen production. Improves thermal stability of the triple helix. | Co-express with collagen genes in host systems (e.g., P. pastoris) [10]. |

| EDC (1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) | Zero-length chemical crosslinker for collagen and fibrin scaffolds. Enhances mechanical strength and stability. | Use in MES buffer (pH 5.5); requires careful rinsing to remove urea by-product [16]. |

| THPP (β-[Tris(hydroxymethyl)phosphino]propionic acid) | Biocompatible chemical crosslinker for lysine-containing ELPs. Enables rapid hydrogel formation. | Reacts with lysine residues; forms hydrogels within 5 minutes at 37°C [11]. |

| Transglutaminase 2 (TG2) | Enzyme for crosslinking ECM proteins. Enhances matrix deposition and stability in fibrin and collagen scaffolds. | Overexpression in stem cells (e.g., EMSCs) significantly improves osteogenic outcomes in fibrin scaffolds [15]. |

| Inverse Transition Cycling (ITC) | Non-chromatographic purification method for ELPs. Leverages their thermal phase transition behavior. | Purify ELPs from E. coli lysate; involves alternating centrifugation above and below Tt [12] [13]. |

| Alosetron hydrochloride | Alosetron Hydrochloride | High-purity Alosetron hydrochloride, a selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonist. For research applications only. Not for human use. |

| 1,1-Dimethyl-4-acetylpiperazinium iodide | 1,1-Dimethyl-4-acetylpiperazinium iodide, CAS:75667-84-4, MF:C8H17IN2O, MW:284.14 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Concluding Remarks

The functionalization of biomaterials using recombinant DNA technology has ushered in a new era of precision in tissue engineering. Recombinant collagen, ELPs, and fibrin each offer a unique and powerful set of properties that can be tailored to meet the specific physiological and mechanical demands of target tissues. As production scales increase and costs decrease, these recombinant proteins are poised to move from bench-side research to mainstream clinical applications, ultimately enabling the development of more effective and predictable regenerative therapies. Future work will likely focus on creating more complex multi-protein hybrid scaffolds that better mimic the intricate composition of the native extracellular matrix.

The field of regenerative medicine is increasingly focused on replicating the dynamic mechanical and biochemical signaling of the native extracellular matrix (ECM) to direct cellular behavior and tissue regeneration. The extracellular matrix serves as a sophisticated biological framework that transcends its conventional role as a passive structural scaffold, actively orchestrating fundamental cellular processes through integrated biomechanical and biochemical cues [17]. Understanding mechanosensing and mechanotransduction pathways—the processes by which cells perceive and respond to mechanical stimuli—forms the essential proof of concept for biomaterial-based polymer-cell interaction [18]. In this context, recombinant DNA technology provides powerful tools for engineering biomaterials with precisely controlled bioactivity, moving beyond static structural mimicry to create dynamic interfaces that guide tissue repair and regeneration.

Foundational Principles: ECM Mechanobiology and Integrin Signaling

The Mechanosensing and Mechanotransduction Cascade

Cellular interaction with biomaterials occurs through a sophisticated mechanobiological dialogue. The process begins with mechanosensing, where transmembrane proteins (e.g., integrins) and ion channels (e.g., Piezo 1 and 2) perceive biophysical stimuli from the material surface [18]. These inputs are then converted into biochemical signals through mechanotransduction, involving focal adhesion proteins (Vinculin, Paxillin, Talin), cytoskeletal components, and downstream effectors that ultimately regulate gene expression and cell decision-making [18].

The following diagram illustrates this cellular mechanoresponse to biomaterial cues, mirroring natural ECM stimulation:

Integrin-Mediated Signaling in Tissue Repair

Integrins serve as fundamental mediators of bidirectional communication between cells and engineered biomaterials. These transmembrane receptors, composed of α and β subunits, recognize specific ECM components and synthetic ligands, orchestrating essential cellular processes including adhesion, migration, proliferation, and survival [17]. The activation of integrin signaling initiates with ligand binding, which induces conformational changes that promote receptor clustering and assembly of focal adhesion complexes [17]. These specialized structures serve as mechanical and biochemical signaling hubs, recruiting adaptor proteins including talin, vinculin, and paxillin to bridge the connection between integrins and the actin cytoskeleton [17].

Central to this signaling network is the focal adhesion kinase (FAK) pathway, which, upon activation at Tyr397, recruits Src family kinases to regulate cytoskeletal dynamics and promote cell migration [17]. Parallel MAPK/ERK pathway activation regulates gene expression for proliferation and differentiation, while the PI3K/Akt pathway promotes cell survival in stressful, injured tissue microenvironments [17]. The mechanical properties of biomaterials—including substrate stiffness, topography, and ligand density—profoundly influence integrin signaling dynamics and subsequent cellular responses [17].

Biomaterial Design Strategies: Matching Native Tissue Properties

Material Selection and Hybrid Approaches

The ideal tissue-engineered graft must achieve mechanical compatibility with the graft site, as disparities in properties can shape the behavior of surrounding native tissue, contributing to graft failure [19]. Biological tissues exhibit complex mechanical properties including heterogeneity, viscoelasticity, and anisotropy, with mechanical properties spanning from the low kilopascal range (neural tissues) to gigapascals (cortical bone) [19]. The following table summarizes key biomaterial classes and their applications in tissue engineering:

Table 1: Biomaterial Classes for Tissue Engineering Applications

| Material Class | Key Examples | Mechanical Properties | Tissue Applications | Functionalization Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Polymers | Alginate, Chitosan, Collagen, Hyaluronic Acid [18] [19] | Low to moderate strength (kPa range), often viscoelastic | Soft tissues, cartilage, neural tissue [18] | RGD peptide incorporation, glycosaminoglycan mimetics [17] |

| Synthetic Polymers | PCL, PLA, PEG, PLGA [18] [19] | Highly tunable strength and degradation | Bone, vascular, musculoskeletal [18] | Surface modification, controlled drug release [17] |

| Bioceramics | Hydroxyapatite, Bioglass [19] | High compressive strength, brittle | Bone, dental [19] | Protein adsorption, ion release |

| Decellularized Matrices | Tissue-derived ECM [19] | Tissue-specific mechanics | Multiple tissue types [17] | Native bioactive factor retention |

| Metals | Titanium, Tantalum [19] | Very high strength and durability | Orthopedic, dental [19] | Surface porosity, coating |

Advanced Fabrication Technologies

Advanced manufacturing technologies enable precise replication of the ECM's hierarchical architecture. Electrospinning creates fibrous scaffolds that mimic collagen organization [17] [19], while 3D bioprinting allows spatial patterning of cells and bioactive factors [17]. 4D printing represents a paradigm shift by introducing time as a functional dimension, utilizing smart biomaterials that can actively respond to external stimuli such as temperature, pH, light, or humidity after fabrication [20]. These constructs can undergo reversible or irreversible changes in geometry, stiffness, or porosity through processes such as swelling, contraction, folding, or self-assembly in response to physiological cues [20].

Recombinant DNA Technology for Biomaterial Functionalization

Virus-Like Particles as Modular Biointerfaces

Recombinant DNA technology enables the creation of sophisticated biointerfaces with precisely controlled presentation of bioactive cues. Virus-like particles (VLPs) have emerged as versatile molecular scaffolds for biomaterial surface biofunctionalization, overcoming limitations associated with native proteins and synthetic peptides [21]. These non-infectious, self-assembling nanoparticles (20-200 nm) composed of viral structural proteins can be engineered to display high densities of bioactive peptides in a controlled orientation [21].

Two primary strategies have been successfully implemented:

- Direct genetic fusion of bioactive peptides (e.g., RGD, YIGSR) to the VLP coat protein (e.g., AP205 bacteriophage)

- SpyTag/SpyCatcher-mediated modular display on computationally designed nanoparticles (e.g., Mi3) for precise biomolecular conjugation [21]

This platform allows co-display of multiple peptides on a single nanoscale scaffold, enabling complex, multifunctional signaling that closely mimics the native ECM [21]. The VLP-based surface biofunctionalization strategy currently reaches Technology Readiness Level (TRL) 3-4, with successful demonstration in controlled laboratory conditions [21].

Experimental Protocol: VLP Production and Biomaterial Functionalization

Protocol 1: Production and Application of Bioactive VLPs for Surface Functionalization

Objective: Recombinant production of functionalized VLPs and their application for biomaterial surface biofunctionalization.

Materials:

- Escherichia coli BL21 Star for protein expression [21]

- AP205 coat protein gene with modified sequences [21]

- In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit [21]

- Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and titanium substrates [21]

- C2C12 mouse myoblast cells (ATCC CRL-1772) [21]

Method:

- Molecular Design and Cloning:

- Engineer coding sequence of AP205 capsid protein to include 6×His purification tag at N-terminus

- Genetically fuse bioactive peptides (RGD, YIGSR, or BMP2 epitope) to C-terminus using flexible glycine-serine-glycine (GSG) linker [21]

- Perform cloning using In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit according to manufacturer's instructions [21]

VLP Expression and Purification:

- Transform engineered constructs into E. coli BL21 Star expression host

- Culture in Lysogeny Broth at 37°C under standard conditions

- Induce protein expression and harvest cells

- Purify VLPs using affinity chromatography via 6×His tag [21]

Surface Functionalization:

- Incubate PDMS or titanium substrates with purified VLPs at varying concentrations

- Allow adsorption to proceed for specified duration

- Rinse gently to remove unbound particles [21]

Bioactivity Assessment:

- Seed C2C12 cells on functionalized surfaces at standard density

- Culture in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin

- Analyze cell adhesion, spreading, and differentiation markers

- Perform immunofluorescence staining for vinculin, integrin β1, and other relevant markers [21]

Quality Control:

- Quantify VLP adsorption using fluorescence intensity measurements from confocal images

- Fit data to nonlinear regression model to determine binding parameters [21]

- Assess cell spreading using Cellpose 2.0 plugin with 100 μm cell diameter model [21]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Biomaterial Functionalization Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|

| AP205 Bacteriophage VLPs | Icosahedral scaffolds for peptide display (30 nm, 180 subunits) [21] | Recombinant production in E. coli [21] |

| Mi3-SpyCatcher Particles | Computationally designed dodecahedral nanoparticles for modular conjugation [21] | Recombinant fusion proteins [21] |

| SpyTag/SpyCatcher System | Irreversible isopeptidic bond formation for biomolecular conjugation [21] | Genetic fusion tags [21] |

| RGD Peptide | Integrin-binding motif from fibronectin for cell adhesion [21] [17] | Synthetic peptide or genetic fusion [21] |

| YIGSR Peptide | Laminin-derived peptide for cell adhesion and differentiation [21] | Synthetic peptide or genetic fusion [21] |

| C2C12 Mouse Myoblasts | Model cell line for evaluating bioactivity [21] | ATCC CRL-1772 [21] |

| Anti-Integrin β1 Antibody | Detection of integrin expression and clustering [21] | Commercial antibodies [21] |

| Anti-Vinculin Antibody | Visualization of focal adhesion formation [21] | Commercial antibodies [21] |

| Semotiadil recemate fumarate | Semotiadil recemate fumarate, MF:C33H36N2O10S, MW:652.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| AL 8810 isopropyl ester | AL 8810 isopropyl ester, MF:C27H37FO4, MW:444.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Quantitative Design Parameters for Tissue-Specific Biomaterials

Achieving mechanical compatibility with native tissues requires careful matching of key biomechanical parameters. The following table provides target properties for various tissue types:

Table 3: Target Mechanical Properties for Tissue-Engineered Constructs

| Tissue Type | Young's Modulus Range | Key Mechanical Characteristics | Critical Biomaterial Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Tissue | 0.1-2 kPa [19] | Soft, compliant | Low modulus, high porosity |

| Adipose Tissue | 2-5 kPa [19] | Soft, viscoelastic | Compressive compliance |

| Muscle Tissue | 10-50 kPa [19] | Anisotropic, contractile | Aligned topography, elastic recovery |

| Cartilage | 0.5-1.5 MPa [19] | Compressive resilience, low friction | High compressive strength, lubricious surface |

| Bone | 5-20 GPa [19] | High compressive and tensile strength | Stiffness, fracture toughness |

Experimental Protocol: Mechanical Characterization of Biomaterials

Protocol 2: Comprehensive Mechanical Characterization of Tissue-Engineered Scaffolds

Objective: To evaluate the mechanical properties of biomaterial scaffolds and ensure compatibility with native tissue.

Materials:

- Universal mechanical testing system

- Hydrated environmental chamber

- Sample scaffolds (various geometries)

- Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for hydration

- Calibrated calibration standards

Method:

- Sample Preparation:

- Hydrate scaffolds in PBS at 37°C for 24 hours to achieve physiological conditions

- Measure sample dimensions precisely using digital calipers

- Mount samples carefully to avoid pre-loading or damage

Tensile Testing:

- Apply uniaxial tension at constant strain rate (e.g., 1% per second)

- Record load-displacement data until failure

- Calculate Young's modulus from linear elastic region

- Determine ultimate tensile strength and failure strain [19]

Compressive Testing (for load-bearing applications):

- Apply compressive loads at physiological strain rates

- Measure compressive modulus and yield point

- For viscoelastic materials, conduct stress-relaxation tests [19]

Functional Mechanical Assessment:

Data Analysis:

- Calculate mean and standard deviation for minimum n=5 samples per group

- Compare mechanical parameters to native tissue values from literature

- For anisotropic materials, characterize properties in multiple orientations

Regulatory and Translation Considerations

The biological evaluation of medical devices incorporating recombinant biomaterials must align with the updated ISO 10993-1:2025 framework, which emphasizes risk-based evaluation integrated within the overall device risk management process [22] [23]. Key considerations include:

- Biological evaluation planning that incorporates assessment of reasonably foreseeable misuse and defines exposure scenarios based on contact days rather than simply transitory contact [22]

- Chemical characterization to identify potential bioaccumulation risks, particularly for devices with cumulative exposure [22]

- Justification for reduced testing through demonstration of biological equivalence where scientifically appropriate [23]

- Implementation of the 3Rs principles (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) for animal testing, with preference for in vitro and in silico methods [23]

The convergence of recombinant DNA technology with biomaterial science has enabled unprecedented precision in designing tissue-engineered constructs that mimic native tissue properties. By controlling both mechanical properties and biological signaling at the molecular level, these advanced biomaterials provide dynamic microenvironments that actively guide tissue repair and regeneration. Future directions include the development of increasingly sophisticated 4D biomaterials that adapt their properties in response to physiological cues, multifunctional VLP systems displaying complex peptide combinations, and personalized approaches that match patient-specific tissue characteristics. As these technologies mature toward clinical translation, they hold tremendous potential to revolutionize regenerative medicine and address unmet needs in tissue repair.

Recombinant DNA technology has revolutionized the field of biomaterial science, enabling the transition from naturally derived materials to precisely engineered, functionalized platforms. This pipeline facilitates the design and production of the next-generation biomaterial scaffolds with tailored properties for specific therapeutic applications [24]. The process involves the genetic engineering of protein-based biopolymers, which can be functionalized with bioactive domains and processed into three-dimensional structures that mimic the native extracellular microenvironment [25] [26]. These inductive scaffolds serve the dual role of providing structural support for cell growth and acting as a controlled release vehicle for tissue inductive factors or the DNA encoding them [25]. This document outlines the standardized protocols and key considerations for the functionalization pipeline, providing researchers with a framework for developing advanced biomaterials for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Core Principles of Recombinant Biomaterial Design

The foundational principle of the biomaterial functionalization pipeline is the use of recombinant DNA technology to design biopolymers that expand the catalog of available biomaterials beyond that which exists in nature [24]. This is achieved by fusing genes encoding for individual protein blocks and functional modules into a single large gene, allowing for absolute control over the polymer's size and composition [26]. This design flexibility allows for the creation of Recombinamers, such as Silk-Elastin Like Polypeptides (SELPs) and Silk-Bacterial Collagens (SBCs), which combine the beneficial properties of different natural proteins [24].

A critical design aspect is the selection of structural modules. Commonly used modules include:

- Elastin-like Polypeptides (ELRs): Composed of repeating VPGXG sequences, these polymers exhibit a reversible temperature-dependent phase-transitional behavior, which is useful for purification and self-assembly [26].

- Silk-elastin-like Proteins (SELPs): These copolymers alternate silk blocks (GAGAGS) with elastin blocks. The silk blocks impart thermal and chemical stability, while the elastin blocks reduce crystallinity and increase flexibility and water solubility [26].

These base polymers can be genetically engineered to include functional modules, such as cell-adhesion peptides (e.g., RGD) or Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs), to create multifunctional materials with enhanced bioactivity [25] [26].

Table 1: Common Functional Modules for Biomaterial Functionalization

| Functional Module | Type | Sequence Example | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-Adhesion Peptide | Peptide | RGD | Promotes cell attachment and spreading via integrin binding [25]. |

| Antimicrobial Peptide (AMP) | Peptide | ABP-CM4, BMAP18 | Confers contact-killing antimicrobial activity to surfaces [26]. |

| Enzyme Cleavage Site | Peptide | MMP-sensitive sequences | Allows for cell-mediated scaffold degradation and remodeling [25]. |

| Growth Factor | Protein | BMP-2, FGF-2 | Directs progenitor cell differentiation and tissue formation [25]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Protocol 1: Genetic Construction and Recombinant Production

This protocol describes the creation of a functionalized SELP with an antimicrobial peptide (AMP), as exemplified by research into antimicrobial surfaces [26].

3.1.1 Materials and Reagents

- Template Genes: Synthetic genes encoding the structural polymer (e.g., SELP-59-A) and the functional module (e.g., AMP ABP-CM4), optimized for E. coli codon usage.

- Expression Plasmid: A modified pET25b(+) vector or similar.

- Restriction Enzymes: NdeI and KpnI.

- Host Organism: Escherichia coli expression strain (e.g., BL21(DE3)).

- Culture Medium: Lysogeny Broth (LB) with appropriate antibiotic (e.g., ampicillin).

- Induction Agent: Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG).

3.1.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Gene Synthesis and Cloning:

- Chemically synthesize the DNA sequence for the antimicrobial peptide (AMP) with flanking NdeI and KpnI restriction sites.

- Digest both the AMP gene and the target plasmid containing the structural polymer gene (SELP-59-A) with the NdeI and KpnI restriction enzymes.

- Ligate the AMP gene fragment into the prepared vector backbone at the N-terminus of the structural polymer gene.

- Transform the ligated product into competent E. coli cells and plate on selective LB-agar plates containing ampicillin.

- Recombinant Protein Production:

- Inoculate a single transformed colony into a small volume of LB medium with ampicillin and grow overnight at 37°C with shaking.

- Dilute the overnight culture into a larger volume of fresh, pre-warmed LB-ampicillin medium.

- Incubate at 37°C with shaking until the culture reaches the mid-log phase (OD600 ~0.6).

- Induce protein expression by adding IPTG to a final concentration of 0.1 - 1.0 mM.

- Continue incubation for 4-16 hours at a temperature optimized for the specific protein (often 25-30°C).

- Non-Chromatographic Purification:

- Harvest the bacterial cells by centrifugation.

- Lyse the cells using sonication or a French press.

- Utilize the inverse transition cycling (ITC) method, which leverages the temperature-dependent solubility of ELRs and SELPs. This involves repeated cycles of heating and cooling in specific buffer solutions to precipitate and isolate the target recombinant protein [26].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of this genetic construction and production process:

Protocol 2: Scaffold Processing and Functional Testing

3.2.1 Materials and Reagents

- Purified Recombinant Protein: The functionalized polymer from Protocol 1.

- Solvents: High-purity water (as a "green" solvent) or Formic Acid (for enhanced polymer chain mobility).

- Casting Surface: A flat, non-adhesive surface (e.g., Teflon or glass).

- Test Microorganisms: Gram-positive (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus) and Gram-negative (e.g., Escherichia coli) bacteria.

- Culture Media: Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB), Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS).

3.2.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Solvent Casting of Free-Standing Films:

- Dissolve the purified recombinant protein polymer in either distilled water or formic acid (e.g., 5-10% w/v) by gentle agitation at room temperature.

- Pour the polymer solution onto a clean, level casting surface.

- Allow the solvent to evaporate fully in a fume hood (for formic acid) or at ambient conditions (for water). This may take 24-48 hours.

- Carefully peel the resulting free-standing film from the casting surface for further testing [26].

- Antimicrobial Activity Testing:

- Prepare bacterial suspensions in PBS or a dilute nutrient broth (like 1/500 TSB) to a concentration of approximately 1x10^5 CFU/mL.

- Place the film samples in contact with the bacterial suspension.

- Incubate for 1-24 hours at 37°C with agitation.

- Quantify the antimicrobial activity by determining the reduction in viable cells, for example, by plating and colony counting or using an optical density measurement [26].

Table 2: Key Growth Factors for Functionalized Scaffolds

| Growth Factor | Molecular Weight (kDa) | Primary Functions in Tissue Engineering | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 (BMP-2) | 44.7 | Osteogenesis; angiogenesis | [25] |

| Fibroblast Growth Factor-2 (FGF-2) | 17.3 | Chondrogenesis; angiogenesis; neuronal and endothelial cell proliferation | [25] |

| Nerve Growth Factor (NGF) | 27 | Promotes neuron survival and extension in CNS and PNS | [25] |

| Transforming Growth Factor-β1 (TGF-β1) | 25 | Promotes chondrogenic differentiation | [25] |

| Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1) | 27.9 | Increases proteoglycans and type II collagen synthesis | [25] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Recombinant Biomaterial Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | Plasmid for hosting the recombinant gene in a microbial factory. | Modified pET25b(+); enables inducible expression in E. coli [26]. |

| Restriction Enzymes | Molecular scissors for precise gene insertion. | NdeI, KpnI; for directional cloning of functional modules [26]. |

| Elastin-like Recombinamers (ELRs) | Base structural polymer providing flexibility and stimuli-responsiveness. | Composed of >200 repeats of VPAVG sequence; exhibits thermal hysteresis [26]. |

| Silk-Elastin-like Recombinamers (SELPs) | Base structural copolymer combining strength and flexibility. | SELP-59-A: 9 tandem repeats of S(ilk)5E(lastin)9 blocks [26]. |

| Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs) | Functional domains to confer bioactive properties. | ABP-CM4, BMAP18, Hepcidin, Synoeca-MP; broad-spectrum activity [26]. |

| Formic Acid | Solvent for processing protein polymers into scaffolds. | Used for solvent casting of free-standing films [26]. |

| Tirofiban hydrochloride | Tirofiban hydrochloride, CAS:150915-40-5, MF:C22H39ClN2O6S, MW:495.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 5,10-Dideazafolic acid | 5,10-Dideazafolic Acid|CAS 85597-18-8|Research Chemical | 5,10-Dideazafolic acid is a potent GARFT inhibitor for cancer research. This product is for Research Use Only and is not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Data Interpretation & Quality Control

The successful functionalization of the biomaterial is confirmed through a combination of molecular biology and material science techniques. SDS-PAGE should be used to verify the protein's molecular weight and purity after purification. The functionality of the incorporated domain, such as an AMP, is validated through standardized antimicrobial assays, with success defined by a significant reduction (e.g., >90% or several log reductions) in viable bacterial counts compared to a non-functionalized control material [26].

The mechanical and physical properties of the final scaffold are critically important. The choice of solvent during processing (e.g., water vs. formic acid) can significantly impact the material's final properties, such as its mechanical strength, surface topography, and subsequent bioactivity [26]. Furthermore, the scaffold must be designed to be both macroscopically stable and microscopically dynamic. This means it provides immediate structural support but also degrades at a rate commensurate with new tissue formation, often achieved by incorporating enzymatically cleavable cross-linkers that are targets for cell-secreted Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) [25].

The following diagram illustrates the mechanism of action for an antimicrobial-functionalized scaffold, a key application of this pipeline:

The increasing incidence of bone-related diseases and fractures, driven by an ageing population and participation in high-risk sports, has created an urgent clinical need for effective bone graft substitutes [27]. While autogenous bone grafts remain the gold standard treatment, they are limited by donor site morbidity, limited availability, and prolonged surgical time [28] [29]. These limitations have accelerated the development of bioactive and resorbable biomaterials that can interact with the injury environment to facilitate recovery in a quick and safe manner [28].

Within this context, recombinant DNA technology has emerged as a transformative approach for creating precisely engineered protein-based biomaterials. This technology enables the design of materials with tailored bioactivity and controlled resorption profiles, addressing fundamental challenges in tissue regeneration. Biomaterials functionalized through recombinant techniques offer unprecedented control over material properties, including degradability, drug release capability, and immune response modulation [29].

Biomaterial Classes and Properties

Therapeutic biomaterials are commonly categorized into several classes based on their composition and properties. The global biomaterials market reflects the significance of these materials, estimated to reach USD 47.5 billion by 2025 from USD 35.5 billion in 2020, with a compound annual growth rate of 6.0% [29].

Table 1: Classification of Biomaterials and Their Key Characteristics

| Material Class | Key Examples | Advantages | Limitations | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metallic | Austenitic steels, Titanium alloys, Cobalt-chromium alloys | Excellent mechanical properties, good strength under static/dynamic loads | Potential corrosion, release of harmful ions, often requires removal surgery | Fracture fixation devices, hip and knee joints, dental implants [29] |

| Ceramic | Hydroxyapatite (HA), Calcium phosphates, Bio-glasses | High biocompatibility, osteoconductivity, corrosion resistance | Brittle nature, low resistance to dynamic bending, poor tensile strength | Bone graft substitutes, dental applications, coatings for metal implants [28] [29] |

| Polymeric | PLGA, PLA, PGA, Elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs) | Biodegradability, tunable properties, can be functionalized | Rapid degradation possible, mechanical stability concerns | Tissue engineering scaffolds, drug delivery systems, sutures [28] [29] |

| Recombinant Protein-Based | Silk-elastin-like polymers, Fusion proteins (e.g., FN-Ubx, Z-4RepCT) | Precise control over sequence/structure, inherent bioactivity, self-assembly capability | Complex production process, potential immune response, scaling challenges | Biosensing, drug delivery, enzyme immobilization, tissue engineering [6] |

The Role of Recombinant DNA Technology in Biomaterial Functionalization

Recombinant DNA technology enables the creation of fusion proteins where functional protein domains are genetically fused to self-assembling protein sequences [6]. This approach involves creating a fusion gene where the DNA sequence encoding the functional protein is placed end-to-end with the DNA sequence encoding the self-assembling protein, without intervening stop codons [6]. When expressed in an appropriate host system, this genetic construct produces a single fusion protein containing both functional and structural elements in a single amino acid chain.

The key advantage of this approach includes the elimination of separate functionalization steps during materials synthesis, uniform and dense coverage of the material by the functional protein, and stabilization of the functional protein through reduced protease access and limited mobility [6]. The confined space surrounding the fused proteins hampers protein unfolding, resulting in prolonged enzymatic, signaling, and biological activities [6].

Table 2: Representative Functional Domains in Recombinant Fusion Proteins for Biomaterials

| Fusion Protein | Functional Domain/Protein | Self-Assembling Protein | Linker | Fusion Terminus | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FN-Ubx | Type III domain 8–10 of Fibronectin (FN) | Ultrabithorax (Ubx) | GH | N | Tissue engineering [6] |

| Z-4RepCT | IgG-binding domain Z | 4RepCT | LEALFQGPNS | N | Ligand binding [6] |

| ScFv-NC | Single-chain variable fragments | N- and C-terminal domains of natural spider silk | None | N | Molecular recognition [6] |

| mCherry-Ubx | mCherry | Ubx | GH | N | Fluorescent tagging [6] |

| MBP-Ubx | Maltose-binding protein | Ubx | GTNIDDDDKHMSGSG | N | Ligand binding [6] |

| RLP12 | RGDSP, protease cleavage site, heparin binding domain | 12 resilin-like motifs | GGKGG, AEDL, and GGRGG | Middle | Multifunctional scaffold [6] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Development and Evaluation of HA/PLGA/Bleed Composite Scaffold

This protocol details the methodology for creating and testing a composite biomaterial with enhanced regenerative properties, as demonstrated in a rat calvarial defect model [28].

Scaffold Preparation

- HA/PLGA Base Material Preparation: Dissolve commercial PLGA polymer in chloroform and place in an ultrasonic bath. Disperse hydroxyapatite (HA) nanoparticles (synthesized via calcium hydroxide precipitation with orthophosphoric acid) step by step into the solution. After 10 minutes of mixing, transfer the mixture to glass plates and allow evaporation at room temperature for 24 hours. Transfer to a vacuum chamber for an additional 48 hours. The resulting scaffold should have a composition of 30% HA + 70% PLGA with 1.5-mm thickness [28].

- HA/PLGA/Bleed Composite Preparation: Crush the HA/PLGA compound in a knife mill and sieve through an analytical sieve with known granulometry to obtain granules. Add vegetable polysaccharide paste (Bleed) to this initial mixture. Lyophilize the final suspension to create scaffolds with proportion of 2.4% HA + 5.6% PLGA + 92% Bleed, with 1.5-mm thickness and 8-mm diameter [28].

In Vivo Evaluation in Rat Calvarial Defect Model

- Animal Model and Surgical Procedure: Use three-month-old male Wistar rats (mean body mass 280 ± 20 grams). Anesthetize animals intraperitoneally, perform aseptic preparation of the surgical site, and make a 1.5 cm incision in the medial region of the skullcap. Create a critical-size defect using an 8-mm external diameter trephine drill driven by a micromotor at 13,500 rpm with continuous saline irrigation. Break through both external and internal cortices until dura mater exposure [28].

- Experimental Groups: Randomly distribute animals into three groups: (1) Control group (untreated defect), (2) Biomaterial group 1 (HA/PLGA scaffold implanted), and (3) Biomaterial group 2 (HA/PLGA/Bleed scaffold implanted). Use eight animals per group per evaluation time point [28].

- Postoperative Care and Euthanasia: Administer analgesic (dipirone-sodium in 6.2 mg.kg-1 proportion) post-surgery. Perform euthanasia by anesthetic overdose at 15, 30, and 60 postoperative days. Immediately collect the critical-size bone defect area for analysis [28].

Histological Analysis and Immunohistochemistry

- Tissue Processing: Fix samples in 10% buffered formalin for 24 hours, decalcify in 4% EDTA solution, and embed in paraffin. Cut sections at 5 µm thickness and mount on histological slides [28].

- Collagen-1 and RANK-L Assessment: Perform immunohistochemical staining for Collagen-1 (Col-1) and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-Î’ ligand (Rank-L) according to standard protocols. Evaluate expression semi-quantitatively or quantitatively to assess bone matrix formation and remodeling activity [28].

Diagram 1: Composite Scaffold Development Workflow

Protocol: Genetic Functionalization of Self-Assembling Protein Biomaterials

This protocol describes the creation of functionalized biomaterials through recombinant fusion of functional proteins to self-assembling protein domains [6].

Fusion Gene Design and Vector Construction

- Functional Domain Selection: Select functional protein domains based on desired biomaterial activity (e.g., fibronectin domains for cell adhesion, fluorescent proteins for tracking, enzyme domains for catalysis).

- Linker Design: Incorporate short linker sequences (e.g., GGKGG, AEDL, GGRGG, GH, or LEALFQGPNS) between functional and self-assembling sequences to prevent steric hindrance and allow independent folding of domains [6].

- Fusion Gene Assembly: Clone DNA sequence encoding the functional protein end-to-end with DNA sequence encoding the self-assembling protein (e.g., Ultrabithorax, 4RepCT, elastin-like polypeptides) without intervening stop codons. Insert appropriate regulatory sequences for expression in the selected host system [6].

Protein Expression and Purification

- Host System Selection: Choose appropriate expression system based on protein requirements. E. coli provides low-cost production but may require endotoxin removal. Alternative systems include other bacteria, yeast, insect cells, and mammalian cells (e.g., Chinese hamster ovary cells) for complex proteins [6].

- Protein Expression: Express fusion proteins in selected host system under optimized conditions. For E. coli, standard fermentation protocols with appropriate antibiotics and induction agents are typically employed.

- Purification: Purify recombinant fusion proteins using affinity chromatography (e.g., His-tag, GST-tag) or methods appropriate for the specific fusion partner. For in vivo applications, ensure removal of bacterial endotoxins using specialized columns or alternative host systems [6].

Material Formation and Characterization

- Self-Assembly Induction: Induce material formation under appropriate buffer conditions, which may involve temperature shift, pH change, or concentration-dependent assembly based on the specific self-assembling domain.

- Structural Characterization: Analyze material structure using electron microscopy, atomic force microscopy, or other appropriate techniques to confirm proper assembly and morphology.

- Functional Assessment: Evaluate retention of functional domain activity using domain-specific assays (e.g., binding assays for receptor domains, enzymatic assays for enzyme fusions).

Key Research Findings and Data Analysis

Comparative Performance of Biomaterial Scaffolds

Experimental evaluation of different biomaterial compositions provides critical data for understanding structure-function relationships in bone regeneration.

Table 3: Comparative Performance of HA/PLGA and HA/PLGA/Bleed Scaffolds in Rat Calvarial Defect Model [28]

| Evaluation Parameter | Time Point | Control Group | HA/PLGA (BG1) | HA/PLGA/Bleed (BG2) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen-1 Fibers | 15 days | Minimal | Moderate | High | BG2 > BG1 > CG |

| Collagen-1 Fibers | 30 days | Low | Moderate | High | BG2 > BG1 > CG |

| Collagen-1 Fibers | 60 days | Moderate | High | Very High | BG2 > BG1 > CG |

| RANK-L Immunoexpression | 15 days | Low | Moderate | Moderate | BG1 ≈ BG2 > CG |

| RANK-L Immunoexpression | 30 days | Low | Moderate | High | BG2 > BG1 > CG |

| RANK-L Immunoexpression | 60 days | Moderate | Moderate | High | BG2 > BG1 ≈ CG |

| Tissue Structural Organization | 60 days | Poor | Moderate | Well-organized | BG2 > BG1 > CG |

Analysis of Results

The HA/PLGA/Bleed scaffold (BG2) demonstrated superior performance across multiple parameters compared to HA/PLGA alone (BG1). Histological analysis revealed significantly higher collagen type I (Col-1) fiber formation in BG2 at all time points, indicating enhanced bone matrix formation [28]. The increased RANK-L immunoexpression observed in BG2 at 30 and 60 days suggests heightened degradation of the biomaterial and increased bone remodeling activity [28]. These findings indicate that the addition of the Bleed polysaccharide component significantly enhanced the biological performance of the composite material.

The superior performance of the HA/PLGA/Bleed scaffold is attributed to the hemostatic properties of the Bleed polysaccharide, which immediately activates coagulation factors, controls local blood leakage, and creates a favorable environment for subsequent regeneration processes [28]. This demonstrates the importance of designing biomaterials that not only provide structural support but also actively participate in the regenerative process through strategic material composition.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biomaterial Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Hydroxyapatite (HA) Nanoparticles | Mineral component mimicking natural bone structure; provides osteoconductivity | Synthesized via calcium hydroxide precipitation with orthophosphoric acid [28] |

| PLGA Polymer | Biodegradable polymer providing mechanical stability and controlled degradation | Dissolved in chloroform for scaffold formation; typically used in 70:30 ratio with HA [28] |

| Bleed Polysaccharide | Hemostatic agent activating coagulation factors; enhances regenerative environment | Vegetable-derived polysaccharide paste; comprises up to 92% of HA/PLGA/Bleed composite [28] |

| Recombinant Fusion Proteins | Self-assembling biomaterials with precisely integrated bioactivity | Genetic fusions of functional domains (e.g., fibronectin, fluorescent proteins) with self-assembling proteins (e.g., Ubx, 4RepCT) [6] |

| Linker Sequences | Spacers between functional and self-assembling domains preventing steric hindrance | Amino acid sequences (e.g., GH, LEALFQGPNS, GGKGG); typically 2-10 amino acids [6] |

| Expression Host Systems | Production platforms for recombinant protein biomaterials | E. coli (standard), specialized E. coli (truncated endotoxin), yeast, insect cells, mammalian cells (CHO) [6] |

| Acetaminophen Glucuronide Sodium Salt | Acetaminophen Glucuronide Sodium Salt, CAS:120595-80-4, MF:C14H16NNaO8, MW:349.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Arbutamine Hydrochloride | Arbutamine Hydrochloride | Arbutamine hydrochloride is a potent, non-selective beta-adrenoceptor agonist for cardiac stress research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Signaling Pathways in Biomaterial-Mediated Bone Regeneration

Diagram 2: Bone Regeneration Signaling Pathway

The development of bioactive and resorbable biomaterials represents a paradigm shift in addressing clinical needs in bone regeneration. The integration of recombinant DNA technologies with biomaterial science has enabled the creation of sophisticated materials with precisely controlled bioactivity and resorption profiles. As demonstrated by the enhanced performance of composite materials like HA/PLGA/Bleed, strategic material design that incorporates multiple functional components can significantly improve regenerative outcomes. These advances, coupled with the precise control offered by recombinant protein engineering, are paving the way for a new generation of biomaterials that actively participate in the regenerative process while progressively transferring load to newly formed tissue.

From Bench to Bedside: Methodologies and Breakthrough Applications in Tissue Engineering

Recombinant DNA technology serves as a foundational pillar in biomaterial functionalization research, enabling the production of engineered proteins that enhance material bioactivity, specificity, and therapeutic potential. The selection of an appropriate protein expression system is a critical initial step that directly influences the success of downstream applications. This choice necessitates a careful balance between achieving sufficient protein yield and accommodating the structural complexity of the target protein [30]. Bacterial systems offer simplicity and high yield for straightforward proteins, while mammalian systems provide the necessary cellular machinery for processing complex human therapeutics, albeit with increased cost and lower volumetric yield [31].

This application note provides a structured framework for researchers and drug development professionals to navigate the selection of protein expression systems. We present comparative quantitative data, detailed protocols for high-throughput screening methods, and visual workflows to guide the integration of these systems into recombinant biomaterial research and development.

Comparative Analysis of Major Expression Systems

The selection of a host system is primarily guided by the protein's structural complexity and post-translational modification requirements. Below is a summary of the key characteristics of the most commonly used expression systems.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Protein Expression Systems

| Expression System | Typical Yield Range | Key Advantages | Major Limitations | Ideal for Proteins With |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial (E. coli) | 1 - 10 g/L [32] | Rapid growth, high yield, cost-effective, simple scale-up [31] | No PTMs, improper folding, protein misfolding, inclusion bodies [31] [30] | Simple, single-domain prokaryotic structures, no glycosylation needed [30] |

| Yeast (P. pastoris) | Up to 20 g/L [31] [32] | Eukaryotic PTMs, high-density cultivation, secretion into medium, rapid screening [31] [33] | Non-human glycosylation patterns, potential hyperglycosylation | Eukaryotic origin, requiring glycosylation or disulfide bonds |

| Insect Cell-Baculovirus | 0.1 - 1+ g/L [31] | Complex PTMs, proper folding of eukaryotic proteins, safety (non-human pathogen) [34] | Slower growth, more expensive than microbial systems, non-human glycosylation | Complex tertiary/quaternary structures, VLPs, vaccine antigens [34] |

| Mammalian (CHO, HEK293) | 0.5 - 10 g/L [31] [32] | Human-like PTMs, high protein quality and functionality, correct folding and secretion [31] [35] | High cost, long culture times, technical complexity, risk of contamination [32] | Complex human therapeutics (mAbs, cytokines), critical human-like glycosylation [35] |

The decision-making workflow for selecting an expression system based on protein complexity and project goals can be visualized as follows:

Advanced Screening and Display Platforms

For the development of advanced biomaterials and biologics, high-throughput screening technologies are indispensable for identifying high-affinity binding molecules.

Yeast Surface Display for Initial Discovery

Yeast Surface Display (YSD) is a powerful eukaryotic platform for antibody discovery and engineering. It leverages the simplicity and cost-efficiency of yeast to present antibody fragments on the cell surface [36] [33].

Key Protocol Steps:

- Library Construction: Clone a diverse antibody gene library (e.g., scFv, Fab) into a display vector, fusing it to a yeast cell wall protein (e.g., Aga2p).

- Transformation & Induction: Introduce the library into S. cerevisiae strain EBY100. Induce protein expression and surface display with galactose.

- Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting (MACS): Incubate the yeast library with biotinylated antigen. Use streptavidin-conjugated magnetic beads to capture antigen-binding clones, enriching the pool.

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): Label the induced yeast library with fluorescent ligands:

- Antigen Binding: Use a biotinylated antigen detected by a streptavidin-fluorophore conjugate.

- Expression Level: Use an anti-epitope tag antibody (e.g., anti-c-myc) conjugated to a different fluorophore.

- Isolation of Binders: Use FACS to isolate individual yeast cells that are double-positive for both expression and antigen binding.

- Sequence Analysis: Sequence the plasmid DNA from sorted clones to identify the antibody variable regions for further characterization.

Mammalian Cell Display for Developability Screening