Electroconductive Biomaterials for Neural Tissue Engineering: Bridging the Gap to Neural Repair

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements in electroconductive biomaterials for neural tissue engineering, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Electroconductive Biomaterials for Neural Tissue Engineering: Bridging the Gap to Neural Repair

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements in electroconductive biomaterials for neural tissue engineering, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles that make electrical conductivity critical for neural repair, details the methodologies for developing and applying conductive scaffolds and hydrogels, addresses key challenges in biocompatibility and long-term stability, and evaluates the performance of these materials against traditional options. By synthesizing current research and future trends, this review serves as a strategic resource for guiding the development of next-generation therapies for neurological injuries and diseases.

The Rationale for Conductivity: Why Nerves Need Electroactive Scaffolds

The Native Electrophysiological Environment of Neural Tissues

The native electrophysiological environment of neural tissues is a complex, dynamic system where electrochemical signaling underpins all brain function, including sensory processing, motor control, and cognitive operations. This environment maintains precise ionic gradients, supports action potential propagation, and facilitates synaptic transmission through specialized structures and signaling mechanisms. Preserving the spatial and functional integrity of this native environment is crucial for accurate neuroscientific investigation and therapeutic development [1]. Traditional in vitro models often strip away this critical complexity, whereas native tissue preparations preserve the architectural and functional context of neural circuits, providing a more accurate representation of in vivo conditions [1]. Within this native landscape, electrophysiological activity occurs across multiple scales—from single-ion channel currents to synchronized network oscillations—creating a rich electrophysiological signature that reflects both health and disease states. Understanding this native environment is particularly pivotal for the field of neural tissue engineering, where emerging electroconductive biomaterials aim to replicate these properties to promote neural repair and regeneration [2] [3].

Fundamental Components of the Native Electrophysiological Environment

The native electrophysiological landscape is structured by both cellular elements and extracellular components that collectively enable efficient neural communication. The following table summarizes these core components:

Table 1: Core Components of the Native Electrophysiological Environment

| Component | Description | Primary Electrophysiological Function |

|---|---|---|

| Neurons | Electrically excitable cells with specialized processes. | Generate and propagate action potentials; mediate synaptic transmission. |

| Glial Cells | Non-neuronal cells (astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, microglia). | Maintain ionic balance; form myelin sheaths; modulate immune response. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) | Complex network of proteins and glycoproteins. | Provides structural and biochemical support; influences synaptic plasticity. |

| Ionic Gradients | Differential concentrations of Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, Cl⁻ maintained across cell membranes. | Establish resting membrane potential; provide driving force for electrical signaling. |

At the cellular level, neurons form intricate networks with synaptic connectivity and specific structural layouts that enable the dynamic interactions fundamental to neural processing [1]. The preservation of natural protein expression and cellular relationships in native tissue minimizes artifacts that can lead to misleading results in reduced preparation systems [1]. The extracellular space further contributes to the electrophysiological environment through its composition and architecture, which influence signal propagation and provide neurotrophic support.

Techniques for probing native neural electrophysiology

Investigating the electrophysiological language of living neural systems requires technologies capable of capturing electrical activity within preserved tissue architectures. The following experimental platforms are essential for this purpose:

Table 2: Key Electrophysiological Platforms for Native Tissue Investigation

| Technique | Primary Application | Key Measurements | Considerations for Native Tissue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manual Patch Clamp | Precise recordings from individual neurons within intact tissue. | Single-ion channel currents, postsynaptic potentials, action potentials. | Preserves intrinsic neuronal properties and synaptic inputs; technically challenging. |

| Field Recordings | Assessment of population-level activity and synaptic plasticity. | Local field potentials (LFPs), population spikes, long-term potentiation (LTP), long-term depression (LTD). | Reflects integrated synaptic activity from a neuronal population; excellent for circuit-level studies. |

| Multi-Electrode Arrays (MEAs) | Spatiotemporal mapping of activity across tissue regions. | Network firing patterns, burst activity, oscillatory synchrony. | Enables long-term monitoring of network dynamics in healthy and disease models [1]. |

| Wire Myograph | Measurement of contractility in smooth muscle tissue (e.g., vascular). | Force of contraction, relaxation parameters. | Valuable for studying autonomic innervation and neurovascular coupling. |

These platforms enable researchers to study the physiological integrity of neural systems by capturing the complexity of intact circuits, which is crucial for generating translatable data for therapeutic development [1]. The choice of technique depends on the specific research question, whether focused on molecular mechanisms (patch clamp), synaptic integration (field recordings), or network dynamics (MEAs).

Experimental Protocol: Multi-Electrode Array (MEA) Recordings in Acute Brain Slices

This protocol details the methodology for obtaining electrophysiological recordings from native neural tissue using acute brain slice preparations combined with MEA technology, capturing network-level dynamics while preserving cytoarchitecture.

Materials and Reagents

- Animal Model: Wild-type or transgenic adult mice (8-16 weeks old)

- Carbogen: 95% O₂ / 5% CO₂ gas mixture

- Cutting Solution: Ice-cold, carbogen-saturated solution containing (in mM): 110 Choline Chloride, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH₂PO₄, 25 NaHCO₃, 0.5 CaCl₂, 7 MgCl₂, 10 Glucose, 1.3 Na-Ascorbate, 0.6 Na-Pyruvate (osmolarity ~305 mOsm/kg)

- Artificial Cerebrospinal Fluid (aCSF): Carbogen-saturated solution containing (in mM): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH₂PO₄, 25 NaHCO₃, 2 CaCl₂, 1 MgCl₂, 10 Glucose (osmolarity ~300 mOsm/kg)

- Vibratome: For tissue sectioning (e.g., Leica VT1200S)

- Multi-Electrode Array System: Commercial MEA setup with 60 electrodes (e.g., Multi Channel Systems MCS GmbH or Med64 System)

- Recording/Perfusion Chamber: Maintained at 32°C with continuous aCSF perfusion

Procedure

Animal Sacrifice and Brain Extraction: Deeply anesthetize the animal with isoflurane according to approved institutional protocols. Decapitate rapidly and extract the whole brain, immersing it immediately in ice-cold, carbogen-saturated cutting solution for ~1 minute.

Brain Slice Preparation: Mount the brain on a vibratome stage using cyanoacrylate adhesive. Prepare 300-400 μm thick coronal or horizontal sections in ice-cold cutting solution. Transfer slices to a holding chamber containing oxygenated aCSF at 32°C for 30 minutes, then maintain at room temperature for at least 60 minutes for recovery.

MEA Recording Setup: Place one recovered brain slice on the MEA recording chamber, ensuring good contact between the tissue and electrodes. Secure the slice with a nylon harp or similar anchor. Perfuse continuously with oxygenated aCSF (2-3 mL/min) at 32°C.

Data Acquisition: Allow the slice to equilibrate for 20 minutes in the recording chamber. Acquire spontaneous activity for 10-20 minutes. For evoked responses, apply biphasic current pulses (50-200 μA, 0.1 ms pulse width) through selected electrodes. Record signals with a sampling rate of 20-50 kHz, using appropriate band-pass filtering (e.g., 1-3000 Hz for local field potentials; 300-3000 Hz for single-unit activity).

Data Analysis: Process recorded signals offline using custom scripts or commercial software:

- For local field potentials: Apply a low-pass filter (<300 Hz) and analyze power spectra across frequency bands (delta, theta, alpha, beta, gamma).

- For single-unit activity: Apply a high-pass filter (>300 Hz) and detect spikes using threshold-based algorithms.

- For network bursts: Identify synchronous firing across multiple electrodes using cross-correlation analysis.

Diagram 1: MEA Experimental Workflow for Native Tissue Electrophysiology.

Electroconductive Biomaterials: Engineering the Native Environment

Electroconductive biomaterials represent a revolutionary approach in neural tissue engineering by creating scaffolds that mimic the electrical properties of native neural tissue. These materials are designed to bridge the functional gap at neural injury sites, providing both structural support and appropriate electrochemical signaling capabilities to promote regeneration [3].

Table 3: Classes of Electroconductive Biomaterials for Neural Applications

| Material Class | Examples | Conductivity Range (S/cm) | Key Advantages | Neural Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conductive Polymers | Polypyrrole (PPy), Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT), Polyaniline (PANI) | 10⁻³ to 10³ [4] | Biocompatibility, ease of processing, tunable conductivity | Neural electrodes, nerve guidance conduits, cortical implants [5] |

| Carbon-Based Nanomaterials | Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs), Graphene, Graphene Oxide (GO) | 10² to 10⁵ | High conductivity, excellent mechanical properties, nanoscale topography | Spinal cord injury scaffolds, peripheral nerve regeneration [3] |

| Conductive Nanocomposite Hydrogels (CNHs) | GelMA-PPy, Hyaluronic acid-Graphene, PEDOT:PSS-PEG | 10⁻⁴ to 10⁻¹ [3] | Tissue-like hydration, biocompatibility, drug delivery capability | Neural differentiation platforms, 3D neural tissue models, injectable therapies [3] |

The integration of conductive nanocomposite hydrogels (CNHs) is particularly promising as they combine the electrical properties of conductive nanomaterials with the hydration and biocompatibility of hydrogels, creating a microenvironment that closely resembles native neural tissue [3]. These advanced materials support critical regenerative processes including neuronal differentiation, axon guidance, and synaptic reconnection by providing a conductive substrate that enables the propagation of bioelectrical signals essential for coordinating neuronal activity [2] [3].

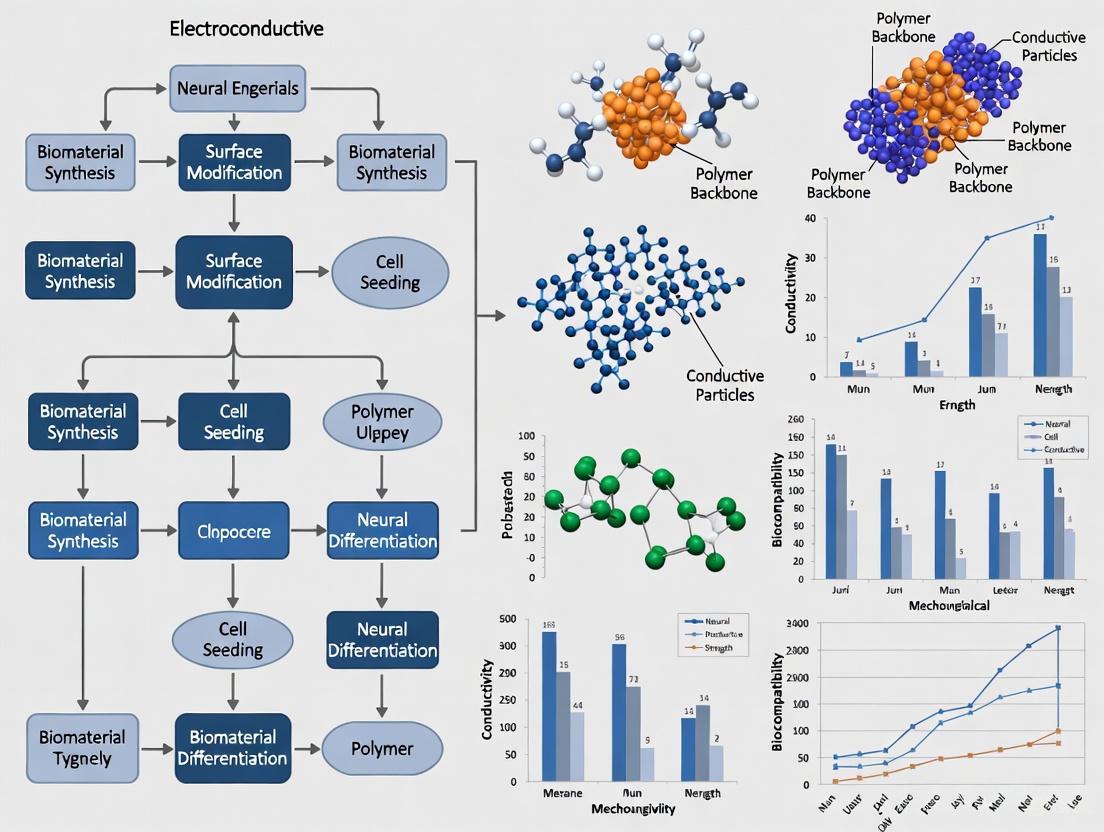

Diagram 2: Bio-inspired Electronics Design Strategies for Neural Interfaces.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This section details critical reagents and materials employed in studying native neural electrophysiology and developing electroconductive biomaterials, providing researchers with a practical resource for experimental design.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Neural Electrophysiology

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrophysiology Solutions | Artificial Cerebrospinal Fluid (aCSF), Sucrose-based cutting solution, Ionic channel blockers (TTX, 4-AP, TEA) | Maintain physiological ionic environment; isolate specific current types | Osmolarity (~300 mOsm/kg), pH (7.3-7.4), continuous carbogenation required |

| Conductive Polymers | PEDOT:PSS, Polypyrrole (PPy), Polyaniline (PANI) | Neural electrode coatings; nerve guidance conduits; conductive scaffolds | Conductivity tunable via doping; biocompatibility varies with composition [4] |

| Carbon-Based Nanomaterials | Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs), Graphene Oxide (GO), Graphene | Neural scaffold reinforcement; conductive composite filler; neural recording electrodes | High aspect ratio; requires dispersion for biocompatibility; potential toxicity at high concentrations [3] |

| Hydrogel Precursors | Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA), Hyaluronic Acid, Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | 3D neural cell culture; injectable delivery systems; scaffold base material | Tunable mechanical properties; photopolymerizable options available [3] |

| Cell Culture Supplements | Neurobasal medium, B-27 supplement, N2 supplement, BDNF, GDNF, NGF | Support neuronal survival and growth; induce neural differentiation | Serum-free conditions often preferred for primary neuronal cultures |

The native electrophysiological environment of neural tissues represents a complex, multi-scale system that is fundamental to neural function and integrity. Faithfully recording from this environment requires specialized techniques that preserve tissue architecture, while repairing it demands innovative materials that replicate its essential electrochemical properties. Electroconductive biomaterials—particularly conductive polymers, carbon-based nanomaterials, and nanocomposite hydrogels—are emerging as powerful tools that bridge the gap between biological and synthetic systems [2] [3]. These materials do not merely provide passive structural support; they actively participate in the electrophysiological dialogue of the nervous system, promoting neural regeneration through guided axon growth, enhanced neural differentiation, and functional synaptic reconnection [2]. As the field advances, the integration of these materials with biohybrid and "all-living" interfaces promises a future where neural implants can achieve seamless structural and functional integration with host tissues, opening new avenues for treating neurological disorders and injuries [5].

Electroconductive biomaterials represent a paradigm shift in neural tissue engineering by providing a biomimetic platform that recapitulates the electrophysiological microenvironment of native nervous tissue. These advanced materials, including conductive polymers, carbon-based nanomaterials, and functional composites, directly influence cellular behavior through mechanisms such as facilitated electrical signal propagation, enhanced cell-to-cell communication, and targeted electrical stimulation. This technical review examines the fundamental principles through which conductive interfaces modulate neural cell responses, detailing the specific cellular pathways activated by electroactive substrates and providing standardized methodologies for evaluating these interactions. By integrating recent advances in material science with core neurobiological principles, this analysis offers a comprehensive framework for developing next-generation neural interfaces and regenerative therapies with enhanced functional outcomes.

The nervous system fundamentally operates through bioelectrical signaling, with native neural tissues exhibiting characteristic electrical conductivity ranging from 0.08 to 1.3 S/m [6]. This inherent electrophysiology creates a dynamic microenvironment where endogenous electric fields play crucial roles in development, maintenance, and repair processes. Following injury, the nervous system demonstrates limited regenerative capacity, often resulting in permanent functional deficits with profound clinical consequences [7]. Traditional therapeutic approaches, including autologous nerve grafts, face significant challenges such as donor site morbidity, limited availability, and suboptimal functional recovery [8].

Electroconductive biomaterials offer a promising strategy to bridge this therapeutic gap by engineering scaffolds that mimic both the structural and electrophysiological properties of native extracellular matrix (ECM). These materials create an interactive biointerface that supports cellular adhesion and proliferation while simultaneously facilitating the transmission of electrical cues that direct cellular behavior [9] [10]. The strategic incorporation of conductive components—including intrinsically conductive polymers, carbon-based nanomaterials, and composite systems—enables researchers to design neural tissue engineering scaffolds that both structurally support regeneration and actively modulate the cellular responses through controlled electrical signaling [11] [6].

Fundamental Mechanisms of Cellular Modulation

Recreation of the Native Electrophysiological Microenvironment

Conductive biomaterials function primarily by replicating the natural electrophysiological environment that neural cells experience in vivo. These materials create a microcurrent environment within neural conduits that promotes neuronal growth and axonal extension [8]. When conductive scaffolds are implemented as nerve guidance conduits (NGCs), they establish electrical continuity that enables the propagation of both endogenous bioelectrical signals and applied electrical stimulation (ES) across the lesion site. This sustained electrophysiological support is particularly crucial during the critical period of axonal regeneration and target reinnervation [8].

The conductive interface facilitates electrotaxis and galvanotaxis—directed cell migration along electrical gradients—which guides axonal growth cones and promotes oriented neural extension [8]. This electrically guided outgrowth significantly enhances the precision of regeneration compared to passive biomaterials. Furthermore, conductive substrates enhance intercellular coupling by facilitating the formation of functional synapses and gap junctions between neighboring cells, ultimately supporting the development of synchronized neural networks essential for complex nervous system function [9].

Electrical Stimulation-Mediated Cellular Responses

The application of controlled electrical stimulation through conductive substrates activates multiple intracellular signaling cascades that direct cellular behavior. Research demonstrates that ES parameters—including specific waveforms, frequencies, amplitudes, and durations—can be optimized to promote distinct neural responses:

- Neurite outgrowth and extension: Applied electrical fields enhance the secretory activity of Schwann cells, increasing the production of neurotrophic factors such as nerve growth factor (NGF) and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) that support neuronal survival and axonal extension [8].

- Stem cell differentiation: ES through conductive substrates promotes the differentiation of neural stem cells and progenitor cells toward neuronal lineages while suppressing astrocytic differentiation, potentially through the activation of voltage-gated calcium channels and subsequent calcium-mediated signaling pathways [9].

- Synaptic maturation: Electrical stimulation enhances the expression of synaptic markers and promotes the formation of functional connections between neurons, critical for restoring neural circuitry after injury [10].

Table 1: Cellular Responses to Electrical Stimulation via Conductive Biomaterials

| Cellular Process | Key Changes | Primary Signaling Pathways |

|---|---|---|

| Neurite Outgrowth | Increased length and branching of axons and dendrites | Calcium signaling, MAPK/ERK pathway |

| Stem Cell Differentiation | Upregulation of neuronal markers (βIII-tubulin, MAP2) | Voltage-gated calcium channels, CREB activation |

| Schwann Cell Activation | Proliferation, neurotrophic factor secretion (NGF, BDNF, GDNF) | PI3K/Akt, JAK/STAT pathways |

| Axonal Guidance | Directed growth cone movement, enhanced regeneration speed | Electrotaxis, cytoskeletal reorganization |

Material-Cell Interface Interactions

At the nanoscale level, conductive biomaterials influence cellular behavior through direct interactions at the material-cell interface. The surface properties of conductive scaffolds—including topography, charge distribution, and energy—directly affect protein adsorption and subsequent cell adhesion [10]. Once cells attach, the conductive interface affects transmembrane potential and regulates the activity of voltage-gated ion channels, thereby influencing intracellular signaling and gene expression patterns [9].

Conductive materials also modulate cytoskeletal dynamics through electromechanical coupling mechanisms. The application of electrical stimuli through these substrates induces rearrangements in actin networks and microtubule organization, directly affecting cell morphology, migration, and process extension [10]. Additionally, conductive interfaces can reduce the formation of inhibitory glial scars by modulating astrocyte behavior, creating a more permissive environment for regeneration [7].

Major Classes of Electroconductive Biomaterials

Conductive Polymers

Intrinsically conductive polymers (CPs) represent the most extensively studied category of electroactive biomaterials for neural applications. These π-conjugated polymers contain delocalized electrons that enable efficient charge transport while maintaining the mechanical flexibility and processability of conventional polymers [9].

- Polypyrrole (PPy): Exhibits high electrical conductivity, ease of synthesis, and excellent biocompatibility. PPy requires doping with anions (Cl⁻, Br⁻, NO₃⁻) to achieve optimal charge transport capabilities, and the choice of dopant significantly influences cellular responses [9]. PPy-based scaffolds have demonstrated enhanced neurite outgrowth and Schwann cell migration under electrical stimulation [8].

- Polyaniline (PANi): Offers tunable conductivity through doping and dedoping processes. While demonstrating promising neural applications, PANi faces challenges related to processability and potential cytotoxicity at higher concentrations [10].

- Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT): Provides superior electrical stability compared to other conductive polymers and can be functionalized with various biological motifs to enhance cellular interactions. PEDOT-based materials show particular promise for neural electrode applications [10].

Carbon-Based Nanomaterials

Carbon-based nanomaterials offer exceptional electrical properties combined with nanoscale dimensions that closely mimic the structural features of natural ECM:

- Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs): Exhibit exceptional electrical conductivity and mechanical strength at nanoscale dimensions. CNTs can be incorporated into composite scaffolds to create conductive networks that support neural growth and differentiation [10].

- Graphene and Graphene Oxide: Provide high surface area with excellent charge transport capabilities. Graphene oxide's functional groups facilitate further modification with bioactive molecules, enhancing its compatibility with neural tissues [12].

- Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO): Balances electrical conductivity with processability, making it suitable for creating conductive coatings on various scaffold architectures [10].

Composite and Hybrid Materials

Composite approaches combine conductive elements with structural biomaterials to create systems with optimized properties for neural tissue engineering:

- Conductive polymer-bioceramic composites: Integrate the electrical properties of conductive polymers with the bioactivity of ceramics to create multi-functional interfaces [10].

- Conductive hydrogel systems: Combine the hydrating properties of hydrogels with electrical conductivity, creating swollen networks that closely mimic the native neural microenvironment [8].

- Conductive nanofibrous scaffolds: Utilize electrospinning techniques to create aligned fibrous structures with incorporated conductive elements that provide both topographical and electrical guidance cues [12].

Table 2: Electrical Conductivity of Native Tissues and Biomaterials

| Material/Tissue | Conductivity Range (S/m) | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Native Neural Tissue | 0.08 - 1.3 [6] | Baseline for biomaterial design |

| Peripheral Nerves | 0.08 - 1.3 [6] | Nerve guidance conduits |

| Polypyrrole (PPy) | 10⁻¹ - 10⁴ [9] | Neural interfaces, conductive coatings |

| PEDOT | 10 - 10⁴ [10] | Electrode coatings, neural probes |

| Carbon Nanotubes | 10² - 10⁵ [10] | Composite reinforcement, conductive networks |

| Graphene | 10³ - 10⁵ [10] | Neural scaffolds, biosensors |

Experimental Methodologies and Assessment

Standardized Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vitro Assessment of Neural Cell Behavior on Conductive Substrates

Materials Required:

- Conductive substrate (PPy, PANi, PEDOT, or composite films)

- Primary neural cells (e.g., dorsal root ganglion neurons, PC12 cells) or neural stem/progenitor cells

- Appropriate culture medium with serum and growth factors

- Electrical stimulation system with custom-built or commercial electrodes

- Immunocytochemistry reagents for neural markers

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Fabricate conductive substrates of consistent thickness (typically 50-200 μm) and sterilize using ethanol immersion or UV irradiation.

- Cell Seeding: Plate cells at optimized density (e.g., 10,000-50,000 cells/cm²) onto conductive substrates and allow attachment for 24 hours.

- Electrical Stimulation: Apply defined electrical parameters (typically 1-100 mV/mm, 1-100 Hz, 30-60 minutes daily) using customized stimulation chambers.

- Fixation and Staining: At predetermined timepoints, fix cells and immunostain for neural markers (βIII-tubulin, MAP2, NF-200 for neurons; GFAP for astrocytes).

- Image Acquisition and Analysis: Capture fluorescent images and quantify neurite length, branching complexity, and orientation using specialized software (e.g., ImageJ with NeuronJ plugin).

Controls: Include non-conductive substrates (e.g., pure PLGA, collagen) and non-stimulated conductive substrates as experimental controls.

Protocol 2: Electrically Conductive NGCs for Peripheral Nerve Repair

Materials Required:

- Conductive nerve guidance conduits (NGCs)

- Animal model (rat or mouse sciatic nerve injury model)

- Surgical instruments for microsurgery

- Electrophysiology setup for functional assessment

- Histological processing equipment

Procedure:

- Conduit Fabrication: Manufacture porous conductive NGCs with appropriate internal architecture (aligned fibers, microgrooves, or luminal fillers).

- Surgical Implantation: Create a critical-size defect (typically 10-15 mm in rat sciatic nerve) and bridge with conductive NGC using microsurgical techniques.

- Functional Assessment: Periodically evaluate functional recovery using walking track analysis, electrophysiological recordings (compound muscle action potential), and sensory tests.

- Tissue Harvest and Analysis: At study endpoint, process explained nerves for histomorphometric analysis (axon density, myelination thickness) and immunohistochemistry.

Key Parameters: Include autograft and non-conduit groups as positive and negative controls, respectively.

Analytical Techniques for Characterizing Cellular Responses

The following dot code illustrates the multi-technique approach required to comprehensively evaluate cell-material interactions:

Intracellular Signaling Pathways Activated by Electroconductive Materials

Electroconductive biomaterials influence cellular behavior through the specific activation of intracellular signaling cascades that regulate growth, differentiation, and function. The following dot code illustrates the key pathways involved:

The primary signaling mechanisms include:

Calcium-mediated signaling: Electrical stimulation through conductive substrates activates voltage-gated calcium channels, leading to increased intracellular calcium levels that trigger downstream effectors including calmodulin-dependent kinases and CREB phosphorylation, ultimately influencing gene expression related to neural growth and differentiation [9].

MAPK/ERK pathway: Conductive material-mediated electrical stimulation promotes the phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1/2), which translocate to the nucleus and regulate the expression of genes involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival [10].

PI3K/Akt pathway: The electrical cues transmitted through conductive scaffolds activate phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and its downstream target Akt, promoting neuronal survival and growth while inhibiting apoptosis [8].

These activated signaling cascades converge to regulate transcriptional programs that enhance the expression of neurotrophic factors (BDNF, NGF, GDNF), cytoskeletal components, and synaptic proteins, collectively promoting neural regeneration and functional recovery [8] [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Neural-Electroconductive Material Studies

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Polymers | Polypyrrole (PPy), Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT), Polyaniline (PANi) | Primary conductive substrates for neural interfaces; typically used as films, coatings, or composite components |

| Dopants | Sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate (SDBS), Chloride (Cl⁻), Polystyrene sulfonate (PSS) | Enhance electrical conductivity and environmental stability of conductive polymers; influence cellular responses |

| Carbon Nanomaterials | Carbon nanotubes (CNTs), Graphene oxide (GO), Reduced graphene oxide (rGO) | Create conductive networks within scaffolds; provide nanoscale topography for enhanced neural interactions |

| Structural Biomaterials | Polycaprolactone (PCL), Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), Collagen, Chitosan | Provide structural framework for conductive elements; ensure mechanical stability and biocompatibility |

| Neural Cell Markers | βIII-tubulin, Microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2), Neurofilament (NF-200) | Identify neuronal cells and processes in vitro and in vivo |

| Glial Cell Markers | Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), S100β, Ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 (Iba1) | Identify astrocytes and microglia; assess glial reactions to conductive materials |

| Neurotrophic Factors | Nerve growth factor (NGF), Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) | Enhance neuronal survival and neurite outgrowth; often used in combination with electrical stimulation |

| Signaling Pathway Reagents | Calcium indicators (Fluo-4, Fura-2), Pathway inhibitors (U0126 for MEK, LY294002 for PI3K) | Investigate molecular mechanisms underlying cellular responses to conductive materials |

Electroconductive biomaterials represent a transformative approach in neural tissue engineering by actively modulating cellular behavior through the recreation of native electrophysiological microenvironments. The core principles underlying their function—including facilitated electrical signal propagation, enhanced cell-to-cell communication, and activation of specific intracellular signaling pathways—provide a robust foundation for designing advanced neural interfaces. As research in this field advances, key challenges remain in optimizing the long-term stability and degradation profiles of conductive materials, precisely controlling the spatial and temporal presentation of electrical cues, and translating promising in vitro results to clinically effective therapies.

Future developments will likely focus on creating smart conductive systems with responsive properties that adapt to changing physiological conditions, integrating multi-modal stimulation approaches that combine electrical cues with biochemical and topological signals, and implementing patient-specific designs enabled by advanced fabrication technologies such as 3D bioprinting. By continuing to elucidate the fundamental principles governing cell-electroconductive material interactions, researchers can develop increasingly sophisticated neural regeneration strategies that ultimately restore function after nervous system injury or degeneration.

Electroconductive biomaterials represent a transformative class of materials at the interface of biology and electronics, offering unprecedented capabilities for interfacing with electrically active tissues. The discovery of intrinsically conductive polymers, recognized by the 2000 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, fundamentally reshaped the landscape of electronic materials and catalyzed their biomedical potential [13]. Within neural tissue engineering, these materials play a crucial role in replicating the native electrophysiological environment, facilitating electrical signal propagation, and guiding cellular behavior to support nerve regeneration [8] [6].

The nervous system's limited self-regenerative capacity in mammals presents a significant clinical challenge, with lasting functional deficits common after injury or disease [7]. Current gold standard treatments for peripheral nerve injury, such as autologous nerve grafts, face limitations including donor site morbidity, limited availability, and incomplete functional recovery [8] [14]. Similarly, central nervous system repair remains largely ineffective clinically [14]. Conductive biomaterials offer a promising alternative by providing scaffolds that not only offer structural support but also actively participate in electrical communication with neural tissues [8] [13].

This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of the major classes of electroconductive biomaterials—polymers, carbon-based nanomaterials, and metallic systems—with emphasis on their properties, mechanisms, and applications in neural tissue engineering. By integrating quantitative performance data, experimental protocols, and visualization of key concepts, this review aims to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the necessary knowledge to advance this rapidly evolving field.

Material Classes and Properties

Electroconductive biomaterials are broadly categorized based on their composition and conduction mechanisms, each offering distinct advantages for neural interface applications.

Conductive Polymers

Conductive polymers (CPs) represent a class of organic materials capable of transporting electrical charges through their conjugated π-electron backbone systems. The electrical conductivity mechanism of these polymers is rooted in their classification into intrinsically and extrinsically conductive systems [13].

Polypyrrole (PPy) stands as the most extensively studied conductive polymer for biomedical applications, maintaining reasonable conductivity (1–75 S/m) under physiological conditions with demonstrated biocompatibility both in vitro and in vivo [14]. Its synthesis typically involves electrochemical polymerization or chemical oxidation in the presence of dopant molecules, which significantly influence material properties including flexibility and surface characteristics [14].

Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) offers enhanced environmental stability compared to other conductive polymers and is often combined with polystyrenesulfonate (PSS) to improve processability. PEDOT demonstrates excellent charge injection capabilities, making it suitable for neural interface applications [13].

Polyaniline (PANI) exhibits tunable conductivity through doping and protonation, though its clinical translation has been limited by processing challenges and potential cytotoxicity concerns [13].

Table 1: Properties of Major Conductive Polymers for Neural Applications

| Polymer | Conductivity Range (S/m) | Key Advantages | Limitations | Neural Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polypyrrole (PPy) | 1–75 | High biocompatibility, ease of synthesis | Moderate mechanical strength, slow degradation | Nerve guidance conduits, neural electrodes |

| PEDOT | 10–1000 | Excellent stability, high conductivity | Rigid backbone, processing challenges | Deep brain stimulation, biosensors |

| Polyaniline (PANI) | 1–1000 | Tunable conductivity, redox activity | Potential cytotoxicity, limited processability | Neural scaffolds, drug delivery systems |

Carbon-Based Nanomaterials

Carbon-based nanomaterials offer exceptional electrical, mechanical, and biological properties that make them attractive for neural tissue engineering applications. Their high surface area-to-volume ratio and capacity for functionalization enable enhanced cellular interactions [15] [16].

Graphene and its derivatives, particularly graphene oxide (GO) and reduced graphene oxide (rGO), demonstrate remarkable electrical conductivity (up to 10⁸ S/m for pristine graphene), mechanical strength, and flexibility. Graphene-based materials support neural cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation while providing appropriate electroactive microenvironments [15] [17].

Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs), both single-walled (SWCNTs) and multi-walled (MWCNTs), exhibit exceptional charge transport capabilities and mechanical reinforcement properties. When incorporated into polymeric matrices, CNTs create conductive networks that promote neurite outgrowth and guide axonal regeneration [16] [17].

Carbon Nanofibers (CNFs) provide a fibrous, high-surface-area architecture that mimics natural extracellular matrix topography, supporting neural cell attachment and alignment while delivering electrical stimulation [15].

Table 2: Carbon-Based Nanomaterials for Neural Tissue Engineering

| Material | Conductivity Range (S/m) | Key Advantages | Limitations | Neural Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene | 10⁶–10⁸ | Exceptional conductivity, mechanical strength, flexibility | Potential aggregation, complex functionalization | Neural scaffolds, bioelectronic interfaces |

| Carbon Nanotubes | 10³–10⁶ | High aspect ratio, excellent charge transport | Potential toxicity concerns, dispersion challenges | Neural composites, conductive coatings |

| Carbon Nanofibers | 10–10⁴ | Fibrous architecture, high surface area | Variable conductivity, structural defects | Electrospun scaffolds, nerve guides |

Metallic and Other Nanomaterials

Traditional metallic conductors including platinum, gold, and titanium remain indispensable in long-term implantable neurodevices due to their electrochemical stability and proven track record in clinical applications [13]. More recently, MXenes—two-dimensional transition metal carbides, nitrides, and carbonitrides—have emerged as promising conductive materials with high metallic conductivity, hydrophilic surfaces, and tunable properties suitable for neural interfaces [13].

Ceramic-based conductors such as diamond-like carbon (DLC) coatings offer exceptional biocompatibility, wear resistance, and electrical properties that can be tuned through doping processes, making them valuable for neural probe applications [13].

Conductivity Mechanisms and Electrical Properties

The electrical conduction mechanisms vary significantly across material classes, influencing their performance in biological environments.

Conduction Mechanisms

Intrinsically conductive polymers transport charge through conjugated π-bond systems where charge carriers (polarons, bipolarons) move along polymer chains and hop between chains. Doping processes introduce charge carriers into the polymer backbone, dramatically increasing conductivity by several orders of magnitude [13].

Carbon-based materials conduct electricity through sp² hybridized carbon networks that allow electron delocalization. In graphene, charge transport occurs through massless Dirac fermions, enabling exceptional electron mobility. Carbon nanotubes exhibit ballistic transport properties, while the conductivity of graphene oxide can be tuned through reduction processes [15] [17].

Metallic conductors operate through free electron models where external electric fields accelerate conduction electrons that subsequently scatter off lattice imperfections, with conductivity governed by the Drude model [13].

Electrical Properties of Native Tissues

Understanding the electrical conductivity of native neural tissues is essential for designing appropriate conductive biomaterials. Neural tissues exhibit conductivity values ranging from 0.08 to 1.3 S/m, varying by specific region and physiological state [6]. Matching these electrical properties is crucial for minimizing interface impedance and promoting effective integration.

Diagram 1: Signaling Pathways in Electrical Stimulation

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Scaffold Fabrication and Characterization

Electrospinning Conductive Nanofibers:

- Prepare polymer solution (e.g., PCL 10-15% w/v in chloroform:methanol 3:1)

- Add conductive component (e.g., 1-5% w/w graphene oxide, 0.5-3% w/w CNTs)

- Utilize electrospinning apparatus with controlled parameters (flow rate 0.5-2 mL/h, voltage 15-25 kV, collection distance 10-20 cm)

- Characterize fiber morphology via SEM, conductivity via four-point probe, and mechanical properties via tensile testing

Conductive Hydrogel Preparation:

- Synthesize or procure base polymer (e.g., collagen, silk fibroin, alginate)

- Incorporate conductive polymers (PPy, PEDOT) via in situ polymerization or carbon nanomaterials via dispersion

- Crosslink using physical (ionic, thermal) or chemical (genipin, glutaraldehyde) methods

- Evaluate swelling ratio, degradation profile, and impedance spectroscopy

3D Printing Conductive Scaffolds:

- Formulate conductive bioinks with appropriate rheological properties

- Optimize printing parameters (pressure, speed, temperature) for structural fidelity

- Implement multi-material approaches for graded conductivity

- Validate architectural integrity via micro-CT and mechanical testing

In Vitro Neural Cell Culture and Electrical Stimulation

PC12 Cell Culture on Conductive Substrates:

- Maintain PC12 cells in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% horse serum, 5% FBS

- Plate cells on conductive scaffolds at 10,000-50,000 cells/cm²

- Differentiate with NGF (50-100 ng/mL) for 5-7 days

- Apply electrical stimulation using customized setups (typically 100-500 mV/mm, 1-20 Hz, 1 hour daily)

- Assess neurite outgrowth via immunostaining (β-tubulin III), quantify length and branching

Human Neural Progenitor Cell (hNPC) Conditioning:

- Culture hNPCs in neural expansion media with EGF and FGF-2

- Seed on PPy scaffolds at 50,000-100,000 cells/cm²

- Apply electrical stimulation protocol (+1 V to -1 V square wave at 1 kHz for 1 hour)

- Analyze gene expression changes (VEGF-A, BDNF, MMP-9) via qPCR

- Implant conditioned cells for in vivo assessment

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Conductive Biomaterial Evaluation

In Vivo Nerve Regeneration Models

Rat Sciatic Nerve Defect Model:

- Create 10-15 mm nerve gap in Sprague-Dawley rats (200-250 g)

- Implant nerve guidance conduit (NGC) with conductive component

- Assess functional recovery weekly via gait analysis, electrophysiology

- Harvest at 4-12 weeks for histology (toluidine blue, immunostaining)

- Quantify myelinated axon density, diameter, G-ratio

Electrical Stimulation Parameters for Nerve Regeneration:

- Intraoperative: 1-3 hours immediately post-implantation, 20 Hz, 100-500 μA

- Chronic: Intermittent stimulation (1 hour/day), various waveforms

- Monitor evoked potentials, muscle reinnervation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Conductive Neural Scaffold Research

| Category | Specific Materials | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base Polymers | Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL), Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), Collagen, Chitosan, Silk fibroin | Structural matrix providing mechanical support, biodegradability | Adjust degradation rate to match tissue regeneration (weeks to months) |

| Conductive Fillers | Polypyrrole (PPy), PEDOT:PSS, Graphene oxide, Carbon nanotubes (SWCNT/MWCNT) | Impart electrical conductivity, enhance mechanical properties | Optimize dispersion and concentration (typically 0.5-5% w/w) for percolation threshold |

| Dopants/Counterions | Chondroitin sulfate, Hyaluronic acid, Polystyrene sulfonate | Enhance processability, stability, and bioactivity | Select based on desired material properties and biological effects |

| Crosslinkers | Genipin, Glutaraldehyde, UV initiators (Irgacure 2959) | Stabilize scaffold structure, control mechanical properties | Balance crosslinking density with cell infiltration and nutrient diffusion |

| Bioactive Factors | Nerve Growth Factor (NGF), BDNF, GDNF, VEGF | Enhance neuronal survival, axonal guidance, angiogenesis | Incorporate via encapsulation, surface immobilization, or gene delivery |

| Cell Types | PC12 cells, Schwann cells, Human neural progenitor cells (hNPCs) | In vitro assessment of biocompatibility and functionality | Primary cells vs. cell lines; species-specific responses |

Applications in Neural Tissue Engineering

Peripheral Nerve Regeneration

Conductive nerve guidance conduits (NGCs) represent a promising alternative to autologous nerve grafts for bridging peripheral nerve gaps. These constructs create a protective microenvironment while delivering electrical cues that promote axonal regeneration. Multimodal strategies have been developed to match different injury types, with short-distance defects benefiting from high-conductivity coatings and long-distance defects relying on wireless piezoelectric stimulation [8].

Advanced designs incorporate conductive coatings (carbon nanotubes, PPy), composite matrices (graphene/PCL), and in situ electro-responsive hydrogels (graphene oxide/silk fibroin) that transmit endogenous electrical signals in real-time while delivering neurotrophic factors for chemical-electrical synergistic regulation [8].

Bioelectronic Interfaces

Neural interfaces integrating flexible electrodes and intelligent catheters enable closed-loop regulation through intraoperative electrophysiological monitoring and adaptive electrical stimulation. Conductive biomaterials serve as critical components in these systems, providing compliant interfaces that minimize foreign body response while maintaining stable electrical performance [8] [13].

Smart Scaffolds with Responsive Capabilities

Fourth-generation conductive scaffolds incorporate stimuli-responsive capabilities, adapting their properties to dynamic physiological changes. Piezoelectric materials (PVDF, ZnO) convert mechanical energy from ultrasound or muscle contraction into local electric fields that drive directional migration of Schwann cells, creating self-powered stimulation systems [8].

Future Perspectives and Challenges

Despite significant advances, the clinical translation of conductive biomaterials faces several challenges that require continued research effort. Cytotoxicity concerns, particularly with certain carbon nanomaterials and metallic nanoparticles, necessitate comprehensive biocompatibility assessment and surface modification strategies [13] [17]. Controlling degradation kinetics to match tissue regeneration rates remains challenging for many conductive polymers [13].

Scalability and manufacturing reproducibility present hurdles for clinical translation, though emerging technologies like 3D printing and microfabrication offer promising solutions [13]. The development of unified design frameworks that correlate material structure, charge transport behavior, and biomedical functionality would significantly advance the field [13].

Future directions include the development of bioresorbable conductors that safely degrade after fulfilling their function, dynamic bioelectronic interfaces with adaptive responsiveness, and personalized conductive scaffolds tailored to individual patient anatomy and pathophysiology. The integration of AI-assisted material design and sustainable manufacturing techniques will further support the transition from laboratory innovation to clinical deployment [13].

As the field advances, conductive biomaterials are poised to revolutionize neural tissue engineering, enabling restoration of function for patients suffering from neurological disorders and injuries through enhanced bioelectronic integration and regeneration.

The development of electroconductive biomaterials for neural tissue engineering represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine. A core tenet of this approach is that engineered scaffolds should replicate the native electrophysiological environment of neural tissues to effectively direct cellular behavior and support nerve regeneration [10] [8]. While the significance of electrical cues is widely acknowledged, a precise understanding of the electrical conductivity properties of target tissues is often overlooked, leading to suboptimal material design. This technical guide establishes the foundational conductivity ranges for neural tissues and related excitable tissues, providing a critical framework for researchers developing next-generation neural interfaces, nerve guidance conduits, and electroactive scaffolds. The objective is to bridge the gap between fundamental tissue electrophysiology and applied biomaterials science, enabling the rational design of constructs that communicate effectively with the nervous system through biomimetic electrical properties.

Electrical Conductivity of Native Tissues

Electrical conductivity, measured in Siemens per meter (S/m), quantifies a material's ability to conduct electric current. For tissues, this property is intrinsically linked to their ionic composition and extracellular matrix architecture. Establishing baseline conductivity values for native tissues is crucial for designing biomaterials that seamlessly integrate with the host's electrophysiological environment.

Conductivity Ranges for Key Tissues

The following table summarizes the characteristic electrical conductivity values for various native tissues, as reported in recent literature. These values serve as targets for biomaterial design.

Table 1: Electrical Conductivity Ranges of Native Human Tissues

| Tissue Type | Electrical Conductivity (S/m) | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Neural Tissue | 0.08 - 1.3 [6] | Broad range encompasses different neural components and measurement conditions. |

| Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) | ≈ 1.5 - 2.0 [18] | Highly conductive due to high ion content. |

| Skeletal Muscle | 0.04 - 0.5 [6] | Highly anisotropic; conductivity is greater parallel to muscle fibers [19]. |

| Cardiac Tissue | 0.005 - 0.16 [6] | Critical for designing patches for myocardial repair. |

| Bone Tissue | 0.02 - 0.06 [6] | Naturally conductive, a target for bone tissue engineering scaffolds [4]. |

| Fat (Subcutaneous) | ~0.02 - 0.04 [6] [19] | Relatively insulating property; values remain constant across a wide frequency range [19]. |

Critical Considerations for Neural Tissue Conductivity

For neural engineering, the target conductivity is not a single value but a carefully considered range. A pivotal 2024 study demonstrated that neural-tissue-like low conductivity (0.02–0.1 S/m) prompted neural stem/progenitor cells (NSPCs) to exhibit a greater propensity toward neuronal lineage specification compared to supraphysiological conductivity (3.2 S/m) [20]. This finding underscores that excessively high conductivity can be detrimental, instigating apoptotic processes due to calcium overload, whereas physiological conductivity promotes balanced intracellular calcium dynamics and beneficial epigenetic changes [20]. Furthermore, it is essential to recognize that conductivity is a frequency-dependent property, especially for anisotropic tissues like skeletal muscle, whose anisotropy decreases with increasing frequency [19].

Experimental Protocols for Conductivity Analysis

To ensure the accurate characterization of both native tissues and engineered biomaterials, rigorous and standardized experimental protocols are essential. The following sections detail two foundational methodologies.

Protocol 1: In Vivo Conductivity Estimation via Bounded Electrical Impedance Tomography (bEIT)

This non-invasive method is used to estimate tissue conductivities in living subjects, providing critical in vivo data that can differ significantly from ex vivo measurements [18] [19].

1. Participant Preparation & Instrumentation:

- Subjects: Recruit healthy volunteers with informed consent and ethical approval.

- Electrode Placement: Affix eight standard electrocardiography electrodes in a tetrapolar configuration on the limb of interest (e.g., forearm). The electrodes should be placed between bony landmarks, such as the wrist and elbow [19].

- 3D Surface Scanning: Use a handheld 3D surface scanner (e.g., Artec Leo) to record the precise spatial locations of all electrodes on the skin surface [19].

2. Data Acquisition:

- Impedance Measurements: Using a impedance analyzer (e.g., MFIA Impedance Analyzer), perform a frequency sweep (e.g., from 30 Hz to 1 MHz). Apply a 1 V excitation voltage and measure the resulting impedance for all unique electrode configurations (e.g., 140 measurements with 8 electrodes) [19].

- Medical Imaging: Acquire T1 and T2-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) images of the instrumented limb using a 3T MRI scanner. Place MRI-visible skin markers to later co-register the MR images with the 3D surface scan [19].

3. Model Construction & Computational Analysis:

- Subject-Specific Model Creation: Segment the MR images to identify different tissue boundaries (e.g., muscle, fat, bone). Integrate the segmented anatomy with the precise electrode locations from the 3D scan to create a subject-specific finite element model (FEM) of the limb [19].

- Forward Problem Solving: Use the FEM to numerically solve the electrostatic forward problem, predicting the surface impedance measurements for a given set of internal tissue conductivities [19].

- Inverse Problem Solving: Employ a probabilistic inverse problem-solving method (e.g., Bayesian estimation) to find the tissue conductivity values that minimize the difference between the computationally predicted impedance and the actual measured impedance. This provides conductivity estimates with robust uncertainty bounds [19].

Protocol 2: Isolating Conductivity Cues for Neural Stem Cell Fate Studies

This cell culture-based protocol is designed to specifically investigate the effect of substrate conductivity on neural cell behavior, independent of other material properties [20].

1. Substrate Fabrication with Decoupled Properties:

- Material Synthesis: Prepare conductive substrates by combining multi-wall carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and graphene oxide nanoribbons (GONRs).

- Controlled Oxidation: Subject the carbon-based films to a controlled oxidation process (e.g., using KMnO₄ and H₂SO₄) for varying durations (e.g., 24 to 48 hours). This systematically tunes the electrical conductivity from supraphysiological (e.g., 3.2 S/m) to neural-tissue-like (e.g., 0.02 S/m) without significantly altering the material's composition or nanoscale roughness [20].

- Surface Functionalization: Pre-coat all substrates with a consistent layer of poly-D-lysine and laminin to ensure a uniform density of cell-binding ligands across all experimental groups, thereby isolating the variable of conductivity [20].

2. Cell Seeding and Culture:

- Cell Type: Utilize neural stem/progenitor cells (NSPCs) or a neuronal cell line such as PC12 cells.

- Seeding: Seed cells at a standardized density onto the fabricated substrates.

- Culture Conditions: Maintain cells under standard conditions (e.g., 37°C, 5% CO₂) with an appropriate differentiation medium, if applicable, for a defined period (e.g., 7-10 days) [20].

3. Endpoint Analysis:

- Immunocytochemistry: Fix and stain cells for cell-type-specific markers: βIII-tubulin (Tuj1) for neurons, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) for astrocytes, and O4 for oligodendrocytes [20].

- Quantitative Image Analysis: Use fluorescence microscopy and image analysis software to quantify the percentage of cells expressing each marker, thereby determining lineage specification.

- Mechanistic Investigation:

- Calcium Imaging: Use fluorescent calcium indicators (e.g., Fluo-4 AM) to monitor intracellular calcium dynamics in live cells.

- Epigenetic Analysis: Perform immunostaining for histone modifications like H3 acetylation (H3ac) to assess chromatin openness and its role in gene activation related to neuronal differentiation [20].

Signaling Pathways in Electrically-Mediated Neural Regeneration

The beneficial effects of electroconductive biomaterials are mediated through specific cellular signaling pathways, which are initiated by the material's ability to transmit or influence bioelectrical signals. The following diagram illustrates the primary signaling cascade triggered by conductive substrates that promote neuronal differentiation.

Pathway Description: Neural-tissue-like conductive substrates promote a balanced intracellular ion flux, particularly of calcium, which acts as a critical second messenger [20]. This balanced signal leads to epigenetic modifications, such as the acetylation of histone H3 (H3ac), which opens the chromatin structure. This open chromatin state facilitates the activation of neurogenic transcription factors and the subsequent expression of genes that drive neuronal lineage specification [20]. In contrast, supraphysiological conductivity can trigger calcium overload, which bypasses this differentiation pathway and instead initiates apoptotic signaling, ultimately impairing neurogenesis [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

To implement the experimental protocols and investigate conductive biomaterials for neural engineering, researchers require a specific set of reagents and materials. The following table catalogues key items and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Neural Conductivity Studies

| Category | Item | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Materials | Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) / Graphene Oxide Nanoribbons (GONRs) | Form tunable, carbon-based conductive substrates for 2D and 3D cell culture studies [20]. |

| Polypyrrole (PPy), Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) | Conductive polymers used to fabricate electroactive scaffolds, hydrogels, and coatings [10] [8]. | |

| Cell Culture | Neural Stem/Progenitor Cells (NSPCs) | Primary model for studying neuronal differentiation and lineage specification in response to conductive cues [20]. |

| PC12 Cell Line | A widely used neuronal cell line for initial adhesion and neurite outgrowth studies [20]. | |

| Cell Staining & Analysis | Anti-βIII-Tubulin (Tuj1) Antibody | Immunostaining marker for identifying newly differentiated neurons [20]. |

| Anti-GFAP Antibody | Immunostaining marker for identifying astrocytes [20]. | |

| Anti-O4 Antibody | Immunostaining marker for identifying oligodendrocytes [20]. | |

| Fluo-4 AM Calcium Indicator | Cell-permeable dye for live-cell imaging of intracellular calcium dynamics [20]. | |

| Anti-H3ac Antibody | Antibody to detect histone H3 acetylation, an indicator of open, active chromatin [20]. | |

| Instrumentation | Impedance Analyzer | Measures the electrical impedance/conductivity of materials and tissues across a frequency spectrum [19]. |

| Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) | Characterizes the nanoscale topography and roughness of conductive substrates to ensure property decoupling [20]. |

The rational design of electroconductive biomaterials for neural engineering is critically dependent on a deep and nuanced understanding of native tissue electrical properties. Target conductivity should not be viewed as a "higher is better" metric but as a biomimetic range that optimally stimulates desired cellular responses, primarily between 0.02 and 0.1 S/m for neural applications [20]. Future progress in the field hinges on the continued refinement of in vivo measurement techniques [18] [19], the development of more sophisticated 3D culture models that better mimic the neural microenvironment [10] [20], and a deeper mechanistic investigation into how biophysical electrical cues are transduced into intracellular biochemical and epigenetic signals. By adhering to the target ranges, experimental protocols, and conceptual frameworks outlined in this guide, researchers can systematically develop advanced conductive biomaterials that significantly improve outcomes in neural regeneration and repair.

From Material Design to Functional Constructs: Fabrication and Application Strategies

The field of neural tissue engineering is increasingly leveraging electroconductive biomaterials to develop advanced strategies for nerve regeneration and repair. These materials are designed to interface with the nervous system by mimicking the electrophysiological microenvironment of native neural tissues, thereby facilitating cellular responses and guiding tissue regeneration. Electrical activity is fundamental to nervous system development and function, regulating crucial processes such as signal transmission and neuronal network activity [21]. Electroconductive biomaterials provide a platform to manipulate cell behavior through exogenous electrical stimulation (ES) in addition to presenting inherent biophysical and biochemical cues [14]. This in-depth technical guide examines five principal classes of electroconductive materials—conducting polymers, carbon nanotubes, graphene, MXenes, and gold nanowires—within the context of neural tissue engineering research. The guide summarizes their fundamental properties, synthesis methodologies, applications in neural interfaces, and detailed experimental protocols for researchers and drug development professionals working in this rapidly advancing field.

Material Classes: Properties, Synthesis, and Applications

Conducting Polymers

Core Polymers and Properties: The most extensively studied conducting polymers for biomedical applications include polypyrrole (PPy), polyaniline (PANI), and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT). These polymers feature a backbone of alternating single and double bonds with overlapping π-bonds that enable electron delocalization and charge transport. Introducing dopants (e.g., polystyrene sulfonate, chondroitin sulphate, hyaluronic acid) disrupts the polymer backbone, creating charge carriers that significantly enhance electrical conductivity [14]. PPy maintains reasonable conductivity (1–75 S/m) under physiological conditions and demonstrates excellent biocompatibility both in vitro and in vivo [14]. PANi and its derivatives, such as aniline oligomers, offer well-defined structures, good electroactivity, and potential for renal clearance [22].

Synthesis and Fabrication: Conducting polymers can be synthesized via chemical polymerization or electrochemical deposition. For neural applications, they are often processed into various architectures:

- Pure Films: Electrochemically synthesized on electrode surfaces (e.g., PPy membranes on indium-tin oxide glass) [22].

- Composite Films: Blended with natural (e.g., chitosan, silk fibroin) or synthetic (e.g., PLA, PCL, PU) polymers to improve mechanical brittleness and processability [22]. These are created using methods like emulsion polymerization, dip-coating, or in situ polymerization.

- Interpenetrating Networks: Formed by coating a polymer scaffold (e.g., PCL) with a conductive polymer layer, creating an interpenetrating network with resistivities suitable for target tissues (e.g., 1.0 ± 0.4 kΩ cm for cardiac tissue) [22].

Table 1: Key Properties and Applications of Conducting Polymers in Neural Engineering

| Polymer | Typical Conductivity | Key Advantages | Common Forms for Neural Applications | Notable Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polypyrrole (PPy) | 1–75 S/m [14] | High biocompatibility, dissolvable in various solvents [14] | Films, composites, nerve conduits | >90% enhancement in neurite outgrowth with ES on PC12 cells; myelinated fibers in rat sciatic nerve after 4 weeks [14] |

| Polyaniline (PANI) | Varies with doping | Well-defined oligomers (e.g., tetramer) with renal clearance potential [22] | Sulfonated copolymers, composite blends | Increased mineralization of MC3T3-E1 cells and BMSCs under ES [22] |

| PEDOT | High conductivity | Excellent electrical stability, often used with PSS dopant | Coatings, composite films | Improved charge injection capacity in neural electrodes |

Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs)

Structure and Properties: Carbon nanotubes are hollow cylinders of graphite sheets, classified as single-walled (SWCNTs) or multi-walled (MWCNTs). They possess exceptional electrical conductivity, high mechanical strength, and a large surface-to-volume ratio [23] [24]. Their nano-scale dimensions and shape closely mimic small neuronal processes, enabling intimate interactions with cell membranes [24]. A key advantage for neural interfaces is their ability to significantly reduce electrode impedance and increase charge injection capacity, which improves the signal-to-noise ratio for recordings and the efficacy of stimulation [23] [24].

Biocompatibility and Cellular Interactions: CNT-based substrates are biocompatible and support neuronal adhesion, survival, and growth [25] [24]. Hippocampal neurons grown on purified SWCNT substrates show intimate contacts between the cell membrane and nanotubes, which provides a physical substrate for electrical coupling [25]. Studies report that CNTs can increase single-cell excitability and spontaneous synaptic activity in neuronal networks, suggesting a capacity to influence neuronal integrative properties [24].

Fabrication of Neural Interfaces: A common method for creating CNT-modified microelectrode arrays (MEAs) involves drop-casting a CNT suspension onto a pre-patterned gold electrode [23]. This approach can lower the electrode impedance at 1 kHz by approximately 50% (e.g., from 17 kΩ to 8 kΩ), enhancing performance for long-term neural interfaces [23].

Graphene and Graphene Oxide

Forms and Properties: Graphene is a single layer of sp²-hybridized carbon atoms arranged in a two-dimensional honeycomb lattice, exhibiting record electrical and thermal conductivity, exceptional mechanical strength, and high flexibility [26]. For biomedical applications, graphene oxide (GO) and electroactive reduced GO (rGO) are often used. GO contains oxygen functional groups, making it hydrophilic and easier to process, while rGO has restored conductivity through the reduction process [27].

Neural Tissue Engineering Applications: Graphene-based materials (GBMs) are promising for neural interfaces due to their carbon-based chemistry and favorable properties [26]. They can be integrated into composite scaffolds, such as electrospun silk/rGO micro/nano-fibrous scaffolds. These non-woven mats can achieve conductivities up to 3 × 10⁻⁴ S cm⁻¹ after hydration and have been shown to support NG108-15 neuronal cell adhesion, viability, and neurite outgrowth (extensions up to ~250 µm) without external electrical stimulation [27]. Research indicates that graphene can promote controlled elongation of neuronal processes, thereby facilitating neuronal regeneration [26].

MXenes

Composition and Synthesis: MXenes are a class of two-dimensional transition metal carbides, nitrides, and carbonitrides with the general formula Mₙ₊₁XₙTₓ, where M is a transition metal, X is carbon or nitrogen, and Tₓ represents surface functional groups (e.g., fluorine, hydroxyl, oxygen) [21]. They are typically synthesized from MAX phase precursors (e.g., Ti₃AlC₂) via a top-down etching process using hydrofluoric acid or other fluoride-containing etchants to remove the "A" layer (e.g., Al), followed by delamination into single or few-layer nanosheets [21].

Properties and Neural Applications: MXenes are hydrophilic, electrically conductive, mechanically strong, and their surfaces can be easily modified [21] [28]. They have been explored as substrates for nerve cell regeneration and reconstruction. For instance, Ti₃C₂Tₓ MXenes have shown excellent biocompatibility with neural stem cells (NSCs), promoting their proliferation and leading to higher neuronal differentiation efficiency [21]. Furthermore, 3D Ti₃C₂Tₓ MXene-Matrigel hydrogel systems have been shown to promote the formation of mature synapses and enhance intercellular signal transmission in spiral ganglion neurons [21]. Their potential also extends to spinal cord injury repair, with GelMA-MXene hydrogels demonstrating effectiveness in repairing completely transected spinal cords in vivo [21].

Gold Nanowires

While the provided search results focus more on other material classes, gold nanowires are another relevant material in neural engineering. They are typically valued for their high electrical conductivity, chemical stability, and excellent biocompatibility. Gold is a standard material for microfabricated electrodes [23], and its nanostructured form (nanowires) can be integrated into composites or used to create conductive networks within insulating hydrogel matrices to provide electrical connectivity while maintaining a soft, tissue-like mechanical modulus.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Electroconductive Biomaterial Classes

| Material Class | Electrical Conductivity | Key Mechanical Properties | Processing Advantages | Limitations & Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conducting Polymers | Moderate (e.g., 1-75 S/m for PPy) [14] | Brittle in pure form; tunable in composites [22] | Easy synthesis & modification, can be made biodegradable [22] [14] | Non-biodegradable (inherent), poor processability, mechanical brittleness [22] |

| Carbon Nanotubes | Very High | Very high strength, flexible [23] [24] | High surface area, can be functionalized [23] [24] | Uncertain long-term in vivo toxicity, potential aggregation [22] |

| Graphene/GO/rGO | Very High (Graphene, rGO) | High strength, flexible [26] | Large surface area, facile functionalization, tunable chemistry [27] [26] | Potential toxicity concerns, complex reduction process for rGO [27] |

| MXenes | High (Metallic conductivity) | Excellent mechanical properties [21] [28] | Hydrophilic, easily modified surface, good biocompatibility [21] [28] | Oxidative instability in physiological environments [21] [28] |

| Gold Nanowires | High (Metallic conductivity) | Ductile, can form percolating networks | Biocompatible, chemically stable, can be synthesized with high aspect ratio | Non-degradable, potentially high cost, may require complex synthesis |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Fabrication of a Conductive PPy/PDLLA Composite Nerve Conduit

Objective: To create a flexible and conductive nerve guidance conduit from a composite of polypyrrole (PPy) and poly(D,L-lactic acid) (PDLLA) [22].

Materials:

- Polymer: Poly(D,L-lactic acid) (PDLLA)

- Monomer: Pyrrole

- Oxidant: Ferric Chloride (FeCl₃)

- Dopant: Polystyrene sulfonic acid (optional)

- Solvent: Dichloromethane or other suitable solvent for PDLLA

- Fabrication Substrate: Glass rod or mandrel of desired diameter

Procedure:

- Form PDLLA Film or Conduit: Dissolve PDLLA in an appropriate solvent to create a polymer solution. Cast the solution into a film or dip-coat a rotating glass mandrel to form a tubular conduit. Allow the solvent to evaporate completely.

- Prepare Polymerization Mixture: Prepare an aqueous mixture containing pyrrole monomer (0.1-0.5 M). A dopant like polystyrene sulfonic acid may be added at this stage.

- Incorporate Oxidant: Immerse the PDLLA scaffold (film or conduit) into the polymerization mixture. Then, add ferric chloride (FeCl₃) as an oxidant to initiate polymerization. The typical molar ratio of oxidant to monomer is around 2.3:1.

- Polymerization: Allow the reaction to proceed for a predetermined time (e.g., several hours) at low temperature (0-4°C) to control the reaction rate and ensure a uniform coating of PPy on the PDLLA surface.

- Post-processing: After polymerization, rinse the resulting PPy/PDLLA composite thoroughly with deionized water and ethanol to remove any unreacted monomers or oxidant. Dry the composite under vacuum at room temperature.

Characterization: The resulting composite can be characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to observe surface morphology and PPy distribution. Electrical conductivity can be measured using a four-point probe method [22].

Preparation of CNT-Modified Microelectrode Arrays (MEAs)

Objective: To reduce the impedance of gold microelectrode arrays (Au-MEAs) by surface modification with multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) for enhanced neural interfacing [23].

Materials:

- Substrate: Glass slides

- Conductive Layer: Gold (Au) source for sputtering

- Nanomaterial: Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) with hydroxyl functional groups

- Solvent: Deionized (DI) water

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation and Gold Deposition: Clean glass substrates thoroughly. Use a sputtering system to deposit a 100 nm thin layer of gold onto the modified glass substrate.

- CNT Suspension Preparation: Obtain MWCNTs with hydroxyl functional groups. Prepare a highly dispersed suspension by sonicating 1 mg/mL of MWCNTs in deionized water for 30 minutes.

- Surface Roughening (Optional but recommended): Perform a surface modification process on the Au electrode to create a roughened surface, which improves CNT adhesion.

- Drop-Casting CNTs: Place a parafilm mask with a defined window (e.g., 1 x 1 cm²) over the electrode surface to control the modification area. Drop-cast the well-dispersed CNT suspension onto the exposed electrode sites.

- Drying and Fixation: Allow the solvent to evaporate slowly at room temperature or on a hotplate at 100°C. The CNTs become embedded and fixed onto the roughened Au surface.

- Patterning (if needed): A laser can be used for final patterning of the electrode structure.

Characterization: Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) is used to measure the electrode impedance before and after modification. A successful modification should show a significant decrease in impedance (e.g., ~50% reduction at 1 kHz) [23].

Fabrication of Electroactive rGO/Silk Fibrous Scaffolds

Objective: To create electroactive micro/nano-fibrous scaffolds from silk and reduced graphene oxide (rGO) for neuronal cell culture [27].

Materials:

- Polymer: Silk fibroin solution

- Conductive Filler: Graphene oxide (GO)

- Reducing Agent: (e.g., Ascorbic acid for in-situ reduction)

- Electrospinning Setup: Syringe pump, high-voltage power supply, collector drum

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Blend silk fibroin solution with GO loadings typically ranging from 1 to 10 wt%. Ensure homogeneous dispersion by vigorous stirring or sonication.

- Electrospinning: Load the silk/GO solution into a syringe. Use an electrospinning apparatus to fabricate non-woven fibrous mats. Typical parameters include a controlled flow rate (e.g., 0.5-2 mL/h), high voltage (e.g., 10-25 kV), and a fixed distance between the needle tip and the collector (e.g., 10-20 cm).

- In-Situ Post-Reduction: Subject the electrospun silk/GO scaffolds to a reducing agent (e.g., ascorbic acid vapor or solution) to convert GO to electroactive reduced graphene oxide (rGO) within the silk matrix.

- Washing and Drying: Rinse the reduced scaffolds thoroughly with water to remove residual reducing agent and dry.

Characterization: Confirm the reduction of GO to rGO via Raman spectroscopy or X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Measure the electrical conductivity of the dry and hydrated scaffolds using a four-point probe or impedance analyzer. The conductivity of hydrated scaffolds can reach up to 3 × 10⁻⁴ S cm⁻¹ [27].

Signaling Pathways in Electrical Stimulation-Mediated Neural Regeneration

Electrical stimulation (ES) activates intrinsic cellular mechanisms that promote nerve regeneration by mimicking natural electrical cues and calcium influx waves [29]. The application of ES to neurons leads to direct effects on cellular ion dynamics and the activation of several key intracellular signaling pathways.

Diagram 1: Signaling pathways activated by electrical stimulation in neural regeneration.

The pathways illustrated above are central to the cellular response to ES. Key experimental evidence includes:

- VEGF-A Upregulation: Electrical stimulation of human neural progenitor cells (hNPCs) on PPy scaffolds significantly upregulated Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A (VEGF-A) and associated factors like matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP-9). Blocking VEGF-A with bevacizumab abolished this effect, confirming the direct role of ES [14].

- Calcium-Dependent Pathways: ES facilitates Na⁺ influx and K⁺ efflux while elevating intracellular Ca²⁺ levels through plasma membrane channels. This elevated calcium activates a cascade including mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K) pathways, which control specific mRNAs and promote neurite growth [29].

- Synergistic Effects: The activation of these pathways, particularly through increased intracellular calcium and VEGF signaling, leads to downstream outcomes crucial for nerve repair: enhanced neurite outgrowth, axonal elongation, and improved cell survival [29] [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Electroconductive Biomaterial Research in Neural Engineering

| Item/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|