Bridging the Gap: A Strategic Guide to In Vitro and In Vivo Biomaterial Testing Comparison

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical comparison between in vitro and in vivo biomaterial testing.

Bridging the Gap: A Strategic Guide to In Vitro and In Vivo Biomaterial Testing Comparison

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical comparison between in vitro and in vivo biomaterial testing. It explores the foundational principles of both methodologies, detailing their specific applications as guided by standards like ISO 10993. The content addresses common challenges, such as the poor correlation between test systems, and presents optimization strategies, including advanced 3D models and refined test conditions, to enhance predictive accuracy. Finally, it establishes a framework for the synergistic use of both testing paradigms to validate biocompatibility and safety, ensuring a more efficient and ethically conscious path from laboratory research to clinical application.

Understanding the Basics: Defining In Vitro and In Vivo Testing Paradigms

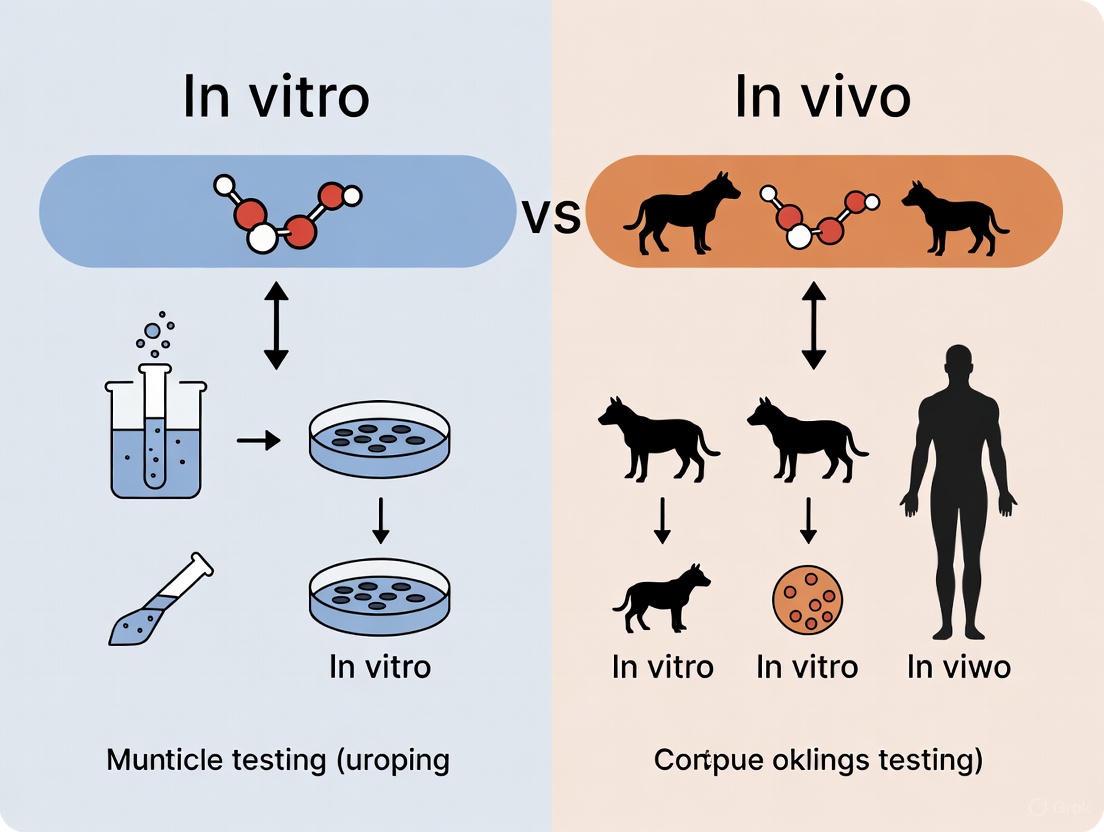

In biomaterial science, predicting how a material will behave once implanted in the human body is the central challenge. Research in this field rests on two fundamental methodological pillars: in vitro and in vivo studies. The term in vitro, Latin for "in glass," refers to experiments performed with microorganisms, cells, or biological molecules outside their normal biological context, typically in labware like Petri dishes or test tubes [1] [2]. In contrast, in vivo, Latin for "within the living," describes studies conducted in or on a whole living organism, such as a laboratory animal or human [3] [2]. The core objective for scientists is to translate findings from the controlled simplicity of in vitro assays to the complex, dynamic reality of an in vivo environment. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these approaches, focusing on their application in evaluating biomaterials for soft tissue reconstruction, to help researchers navigate the strengths and limitations of each.

Core Conceptual Definitions and Comparisons

Defining the Paradigms

In Vitro studies are characterized by their use of components isolated from a living organism. This methodology permits a more detailed or convenient analysis than can be done with whole organisms and is colloquially known as "test-tube experiments" [1]. These studies simplify the system under investigation, allowing researchers to focus on a small number of components, such as the interaction between a specific cell type and a biomaterial [1]. A key advantage is species specificity; human cells can be studied directly, eliminating the need to extrapolate from animal models [1]. Furthermore, in vitro methods are relatively inexpensive, fast, and can be miniaturized and automated for high-throughput screening [1] [4].

In Vivo studies, on the other hand, are defined by their use of a whole, living organism. These studies are designed to provide information regarding the effects of a substance or disease progression in a complex, physiologically complete system [3] [2]. In vivo work is essential for assessing the safety, efficacy, and overall therapeutic profile of a drug or biomaterial before human use [3] [4]. It captures the intricate interplay between different organs, tissues, and physiological factors that cannot be replicated in a dish [5]. However, these studies are very expensive, time-consuming, and are subject to strict ethical regulations [4].

Comparative Analysis at a Glance

Table 1: A side-by-side comparison of in vivo and in vitro methodologies.

| Aspect | In Vitro | In Vivo |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Studies performed "in the glass" outside a living organism [1] [4]. | Studies performed "within a living" organism [3] [4]. |

| System Complexity | Simplified, controlled environment using isolated cells or tissues [1] [5]. | Complex, fully integrated physiological system [5]. |

| Cost & Duration | Relatively low cost and fast results [4]. | Very expensive and long-term studies [4]. |

| Primary Applications | Initial drug/biomaterial screening, mechanism of action studies, high-throughput assays [1] [4]. | Preclinical safety and efficacy testing, pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics (PK/PD), clinical trials [3] [4]. |

| Key Advantages | Experimental control, species specificity, convenience, automation [1] [4]. | Provides specific and reliable data on biological effects in a whole organism [4]. |

| Key Limitations | Physiologically limited; results may not predict in vivo outcomes [1] [4]. | Strict ethical regulations; high cost and complexity; interspecies differences [4] [5]. |

Experimental Models and Methodologies

In Vitro Model Systems

Traditional in vitro models often involve two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures, where a single cell type is grown on a flat plastic surface. While useful for foundational studies, 2D cultures are limited as they cannot replicate the three-dimensional architecture or cell-to-cell interactions found in living tissues [6]. To bridge this gap, Complex In Vitro Models (CIVMs) have been developed.

CIVMs are systems that integrate a multicellular environment within a three-dimensional (3D) biopolymer or tissue-derived matrix [6]. These models seek to reconstruct organ- or tissue-specific characteristics to better mimic in vivo conditions [6]. Key CIVM technologies include:

- Organoids: 3D structures derived from stem cells that self-organize into organ-like structures, recapitulating some functional aspects of the source organ [6].

- Organs-on-a-Chip: Microfluidic devices that combine cell culture with biomedical engineering to simulate a physiological organ environment, including mechanical forces like fluid flow and stretch [6] [4].

- Microphysiological Systems (MPS): Interconnected constructs that combine tissue engineering and biosensors to emulate the functions of an organ in vitro [4].

In Vivo Model Systems

In vivo testing in biomaterial and drug development typically proceeds in two main stages:

- Animal Models (Preclinical): Before human testing, a biomaterial must undergo rigorous evaluation in animals to assess its toxicity, biocompatibility, and efficacy [3] [4]. Rodents, particularly mice, are the most commonly used species due to their size, cost, fast reproduction, and genetic similarity to humans [4]. Studies are designed using disease models induced through invasive procedures, administration of drugs/toxicants, or genetic alteration [3].

- Human Trials (Clinical): If a biomaterial or drug proves safe and effective in animal studies, it progresses to clinical trials in humans [2] [4]. These trials are tightly controlled and monitored to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the intervention in human subjects, often using randomized and blinded designs to ensure result integrity [2].

Quantitative Data: Comparing In Vitro and In Vivo Outcomes

A critical challenge in biomaterial science is correlating in vitro findings with in vivo outcomes. The following data, derived from a study on the host response to implanted materials, illustrates this point.

Table 2: Quantitative comparison of in vitro macrophage responses and in vivo remodeling outcomes for various biomaterials. Data adapted from a study linking in vitro assays to in vivo outcomes [7].

| Material | In Vitro Macrophage Secretion (Relative Levels) | Predicted In Vivo Response (from in vitro data) | Actual In Vivo Remodeling Score (14 & 35 days) | Dominant In Vivo Macrophage Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MatriStem (ECM) | Distinct anti-inflammatory profile | Constructive Remodeling | High | M2 (tissue remodeling) |

| CL-MatriStem (Crosslinked ECM) | Pro-inflammatory profile | Foreign Body Reaction | Low | M1 (pro-inflammatory) |

| D-ECM (Dermal ECM) | Distinct anti-inflammatory profile | Constructive Remodeling | High | M2 (tissue remodeling) |

| Vicryl (Synthetic) | Pro-inflammatory profile | Foreign Body Reaction | Low | M1 (pro-inflammatory) |

| Dual Mesh (Synthetic) | Pro-inflammatory profile | Foreign Body Reaction | Low | M1 (pro-inflammatory) |

Key Findings from the Data:

- ECM-based materials (MatriStem, D-ECM), which are naturally derived, consistently prompted a favorable anti-inflammatory response in vitro that accurately predicted constructive remodeling and a dominant M2 macrophage presence in vivo [7].

- Synthetic and crosslinked materials (Vicryl, Dual Mesh, CL-MatriStem) elicited a pro-inflammatory response in vitro, which correlated with a foreign body reaction, lower remodeling scores, and a dominant M1 macrophage phenotype in vivo [7].

- This study demonstrated that when combined with sophisticated in silico analysis (e.g., Principal Component Analysis and Dynamic Network Analysis), in vitro macrophage assays can serve as a valuable predictor of the in vivo host response to implanted biomaterials [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

A Representative In Vitro Protocol: Macrophage-Biomaterial Assay

This protocol is designed to evaluate the inflammatory potential of a biomaterial by characterizing the dynamic response of human macrophages [7].

Objective: To assess the activation profile of human monocyte-derived macrophages exposed to various biomaterials and use the cytokine secretion profile to predict the in vivo remodeling outcome.

Materials and Reagents:

- Test Materials: Synthetic and biologically derived materials (e.g., ECM scaffolds, polymer meshes) cut into standardized discs.

- Cells: Human monocytes isolated from peripheral blood and differentiated into macrophages.

- Cell Culture Medium: RPMI-1640 supplemented with fetal bovine serum, antibiotics, and macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) for differentiation.

- Analysis Kits: ELISA kits for quantifying cytokine secretion (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α).

Methodology:

- Material Sterilization: All material discs are terminally sterilized using ethylene oxide gas or other appropriate methods [7].

- Macrophage Differentiation: Isolated human monocytes are cultured in M-CSF-containing medium for 7 days to differentiate them into macrophages.

- Material Exposure: Differentiated macrophages are seeded onto the test material discs placed in multi-well culture plates. Control wells contain cells without material or with a reference material.

- Conditioned Media Collection: The culture medium (conditioned media) is collected at multiple time points (e.g., 24, 48, 72 hours) to capture dynamic cytokine secretion.

- Cytokine Quantification: Collected media is analyzed using ELISA to determine the concentrations of key pro-inflammatory (e.g., IL-1β, TNF-α) and anti-inflammatory (e.g., IL-10) cytokines.

- In Silico Analysis: The multidimensional cytokine data is processed using computational methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify distinct response patterns and predict the in vivo outcome [7].

A Representative In Vivo Protocol: Rodent Abdominal Wall Defect Model

This established model is used to evaluate the host remodeling response to a biomaterial in a clinically relevant soft tissue location [7].

Objective: To implant material coupons into a rodent model and assess the in vivo host response, including tissue remodeling and immune cell infiltration.

Materials and Reagents:

- Animals: Female Sprague-Dawley rats.

- Test Materials: Material coupons (e.g., 1x1 cm).

- Surgical Supplies: Sutures (non-degradable for fixation, degradable for skin closure), anesthetic agents, standard surgical instruments.

- Histology Reagents: Neutral buffered formalin, paraffin, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain, antibodies for immunofluorescence (e.g., for M1/M2 macrophage markers).

Methodology:

- Surgical Implantation: A paramedian partial-thickness abdominal wall defect is created in an anesthetized rat. The external and internal oblique muscles are excised, leaving the transversalis fascia intact [7].

- Graft Placement: The size-matched material coupon is inlaid within the defect and fixed to the adjacent muscle at the four corners with non-degradable sutures.

- Post-Op and Explant: The skin incision is closed, and animals are monitored post-operatively. After the predetermined implantation period (e.g., 14 and 35 days), the animals are euthanized, and the implants with surrounding tissue are explanted.

- Histological Processing: Explanted tissues are fixed in formalin, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into thin slices for staining [7].

- Histological Analysis:

- H&E Staining: Used for general histomorphology. A blinded observer scores the tissues semiquantitatively for foreign body giant cell formation, connective tissue organization, encapsulation, and muscle ingrowth to generate a total remodeling score [7].

- Immunofluorescent Staining: Used to identify macrophage phenotype. Sections are labeled with antibodies against M1 markers (e.g., CCR7) and M2 markers (e.g., CD206) to determine the dominant immune response [7].

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

The In Vitro to In Vivo Translation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the sequential and iterative process of translating findings from basic in vitro models to predictive complex models and finally to in vivo validation.

Diagram 1: The iterative workflow for translating in vitro findings to in vivo outcomes.

The Host Response to Biomaterials

This diagram contrasts the typical biological pathways activated by a pro-inflammatory biomaterial versus a constructive remodeling biomaterial, linking cellular events to tissue-level outcomes.

Diagram 2: Key signaling pathways in the host response to biomaterials.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key reagents, materials, and technologies used in biomaterial testing.

| Tool | Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Petri Dishes / Multi-well Plates | Labware | Provide a sterile, controlled environment for 2D cell culture and in vitro assays [1]. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Scaffolds | Biomaterial | Naturally derived materials (e.g., MatriStem) used as test substrates or as components of CIVMs to provide a physiological 3D environment [6] [7]. |

| Synthetic Polymer Meshes | Biomaterial | Materials (e.g., Polypropylene, ePTFE, Vicryl) used as test substrates to study the foreign body reaction and synthetic graft integration [7]. |

| ELISA Kits | Analytical Tool | Quantify specific protein secretion (e.g., cytokines) in in vitro conditioned media or in vivo tissue/tuid samples to assess immune response [7]. |

| Primary Cells (e.g., Macrophages) | Biological Tool | Isolated directly from tissue (human or animal); used in in vitro assays for more physiologically relevant responses than cell lines [7]. |

| Organ-on-a-Chip Devices | CIVM Technology | Microfluidic devices that simulate organ-level physiology for more predictive in vitro drug and toxicology testing [6] [4]. |

| Immunofluorescence Antibodies | Analytical Tool | Allow visualization and identification of specific cell types (e.g., M1/M2 macrophages) and structures in tissue sections from in vivo studies [7]. |

The journey from in vitro discovery to in vivo application remains a central challenge in biomaterial science. While in vitro models offer unparalleled control and throughput for initial screening, their physiological limitations mean results cannot be directly extrapolated to predict outcomes in a living organism [1] [8]. In vivo studies are indispensable for validating safety and efficacy in a whole-body context, but their cost and complexity necessitate their judicious use [4] [5]. The future of the field lies in the development and adoption of more sophisticated Complex In Vitro Models (CIVMs), such as organs-on-chips and patient-derived organoids, which better mimic human physiology [6]. When combined with powerful in silico modeling, these advanced in vitro systems are poised to improve predictive accuracy, help down-select the most promising candidates for in vivo studies, and ultimately accelerate the development of safer and more effective biomaterials [7] [5].

The Critical Role of Testing in the Biomaterial Development Pipeline

The development of novel biomaterials is a complex, multi-stage process where rigorous testing serves as the critical gateway between laboratory innovation and clinical application. Biomaterials, defined as materials engineered to interact with biological systems for medical or therapeutic purposes, must demonstrate exceptional safety, efficacy, and reliability before human use [9]. The testing pathway strategically employs complementary methodologies—in vitro (in glass) and in vivo (within the living) models—to comprehensively evaluate material performance [2] [10]. In vitro studies occur in controlled laboratory environments, such as test tubes or petri dishes, and are ideal for initial screening and mechanistic studies. In contrast, in vivo studies are conducted within whole living organisms, providing essential data on complex physiological interactions and systemic responses [11]. This article objectively compares the performance data, applications, and limitations of these testing paradigms, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a clear framework for navigating the biomaterial development pipeline.

Fundamental Principles: In Vitro vs. In Vivo Testing

Understanding the core definitions and philosophical approaches of each testing methodology is foundational to designing an effective development strategy.

In Vitro Testing: Latin for "in glass," this approach involves experiments performed outside of a living organism [2]. Cells or tissues are maintained in highly controlled, artificial environments, such as culture plates or bioreactors [10]. The primary advantage of this method is the high degree of control over experimental variables, which allows for precise, cost-effective, and rapid screening of biomaterial properties, including cytotoxicity and initial biocompatibility [11] [12]. However, its significant limitation is the inability to replicate the full complexity of a living system, including immune responses, organ-level interactions, and metabolic processes [10] [12].

In Vivo Testing: Latin for "within the living," this methodology involves testing within a whole living organism, typically animal models such as rodents or non-human primates [2] [10]. This approach provides the most physiologically relevant data on how a biomaterial interacts with a complete biological system, informing aspects like long-term biocompatibility, integration with host tissues, and overall safety profile [11]. The main drawbacks include high costs, lengthy timelines, ethical considerations regarding animal use, and greater variability due to inter-individual differences [10] [11].

Table 1: Core Conceptual Differences Between In Vitro and In Vivo Testing.

| Aspect | In Vitro Testing | In Vivo Testing |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Experiments conducted outside a living organism [2] | Experiments conducted within a living organism [2] |

| Experimental Model | Cell cultures, tissues, or organs in an artificial environment [12] | Whole, living animals (e.g., rodents, primates) [10] |

| Key Advantage | High control over variables; cost-effective and rapid [11] | Provides full physiological and systemic context [11] |

| Primary Limitation | Lacks the complexity of a full organism [10] | High cost, time-consuming, and raises ethical concerns [11] |

Performance Data and Comparative Analysis

The choice between in vitro and in vivo models directly influences the type and reliability of performance data obtained for a biomaterial. The key performance parameters in pre-clinical assessment include mechanical integrity, biocompatibility, and degradation behavior [13].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Data from the search results allows for a direct comparison of how these two testing methods are used to evaluate critical biomaterial properties.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Biomaterial Performance Assessment In Vitro vs. In Vivo.

| Performance Parameter | In Vitro Testing Methods & Findings | In Vivo Testing Methods & Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Biocompatibility & Host Response | Macrophage Activation Assays: Cytokine secretion profiles predict foreign body reaction vs. constructive remodeling [7]. | Rodent Implantation Models: Histology shows crosslinked ECM/synthetics cause fibrosis; non-crosslinked ECM promotes constructive remodeling [7]. |

| Mechanical Properties | Tensile Testing: PLA and PHA show sufficient strength and flexibility for load-bearing tissue engineering [9]. | Not the primary method for assessment. Mechanical performance is inferred from implant integrity and functional recovery in the host. |

| Degradation Behavior | Chemical Analysis & Accelerated Aging: Studies on PLA, PHA, and chitosan elucidate degradation rates in controlled biochemical environments [9]. | Explants & Histology: Reveals real-time degradation rate, clearance of byproducts, and correlation between degradation and tissue healing [7]. |

Correlation and Predictive Value

A central challenge in biomaterial development is the translational gap between simplified in vitro models and complex in vivo outcomes. While in vitro data is precise, it does not always accurately predict in vivo responses [12]. For instance, a significant number of drug candidates fail in human clinical trials despite promising pre-clinical in vitro and animal data [2]. To bridge this gap, advanced in vitro models are evolving. For example, one study developed a sophisticated in vitro assay using human macrophages, which, when combined with in silico analysis, successfully predicted the in vivo host response (constructive remodeling versus foreign body reaction) to various biomaterials in a rodent model [7]. Furthermore, technologies like Organ-on-a-Chip systems, which create more physiologically relevant microenvironments with human cells, are emerging as powerful tools to improve predictive accuracy and reduce reliance on animal models [12].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Detailed and standardized protocols are essential for generating reproducible and meaningful data in biomaterial testing. Below are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in this field.

Detailed Protocol: In Vitro Macrophage Activation Assay

This protocol, adapted from a foundational study, is used to predict the in vivo host response to biomaterials by characterizing the dynamic inflammatory response of macrophages [7].

- Objective: To characterize the dynamic inflammatory response of human monocyte-derived-macrophages to biomaterials and identify secretory profiles predictive of in vivo remodeling outcomes.

- Materials Preparation:

- Biomaterial Samples: Cut synthetic and ECM-derived materials (e.g., Polypropylene, Decellularized ECM) into standardized discs (e.g., 2-cm diameter).

- Sterilization: Terminally sterilize all devices using ethylene oxide gas or other appropriate methods that do not alter material properties.

- Cell Culture: Isulate human primary monocytes from peripheral blood and differentiate them into macrophages using Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor (GM-CSF) over 7 days.

- Methodology:

- Culture Setup: Place sterilized biomaterial discs in multi-well culture plates. Seed differentiated macrophages onto the material surfaces at a standardized density (e.g., 500,000 cells/well) in serum-free medium.

- Conditioned Media Collection: Collect cell-conditioned culture media at multiple time points (e.g., 1, 3, 5, and 7 days).

- Analysis of Secreted Factors: Analyze the conditioned media using multiplex immunoassays (e.g., Luminex) to quantify the concentration of key pro-inflammatory (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) and pro-remodeling (e.g., IL-10, TGF-β) cytokines and chemokines.

- In Silico Analysis: Subject the multi-analyte, time-course data to quasi-mechanistic in silico analysis, such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Dynamic Network Analysis (DyNA), to identify dominant, predictive patterns in the macrophage response.

- Outputs: PCA and DyNA generate distinct activation profiles that can discriminate between materials that will elicit a pro-inflammatory (M1) response versus a pro-remodeling (M2) response in vivo [7].

Detailed Protocol: In Vivo Rodent Biocompatibility and Remodeling

This protocol assesses the functional host response and tissue integration of a biomaterial in a live, complex physiological environment [7].

- Objective: To evaluate the in vivo host remodeling response and macrophage polarization to an implanted biomaterial in a rodent skeletal muscle model.

- Materials Preparation:

- Implant Coupons: Cut test biomaterials into small, uniform coupons (e.g., 1 cm x 1 cm).

- Sterilization: Ensure all implants are terminally sterilized as for the in vitro assays.

- Animal Model: Utilize an established model, such as a partial-thickness abdominal wall defect in Sprague-Dawley rats.

- Surgical Implantation:

- Anesthesia and Asepsis: Anesthetize the rodent and prepare the surgical site using aseptic technique.

- Defect Creation: Create a standardized partial-thickness defect in the abdominal wall muscle.

- Implantation: Inlay the biomaterial coupon into the defect and fix it to the adjacent native tissue at the corners using non-degradable sutures for positional stability.

- Closure: Close the surgical site with degradable sutures.

- Post-Op and Analysis:

- Explanation: After a pre-determined implantation period (e.g., 14 and 35 days), euthanize the animals and explant the device with the surrounding host tissue.

- Histological Processing: Fix the explants in formalin, embed in paraffin, and section into thin slices (5 μm) for staining.

- Histological Scoring: Stain sections with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and score them semiquantitatively for key remodeling characteristics: foreign body giant cell formation, degradation, connective tissue organization, encapsulation, and muscle ingrowth. A higher total score indicates more favorable remodeling.

- Immunofluorescence Staining: Label tissue sections with antibodies for macrophage phenotype markers (e.g., CCR7 for M1 and CD206 for M2) to determine the dominant immune response at the implant site.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

A successful testing pipeline relies on a suite of specialized reagents, equipment, and models. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments and the broader field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biomaterial Testing.

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Example/Context |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Testing Machines [14] | Evaluate mechanical properties (tensile strength, compression, elasticity) of biomaterials. | Used for in vitro tensile testing of biopolymers like PLA and PHA to assess strength for load-bearing applications [9]. |

| Human Monocyte-Derived Macrophages [7] | Model the human innate immune response to biomaterials in vitro. | Central to the predictive macrophage activation assay; respond to materials by secreting characteristic cytokine profiles [7]. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM)-Derived Materials [7] | Biologically derived scaffolds (e.g., decellularized dermis, urinary bladder) used as benchmark materials or test articles. | MatriStem (urinary bladder ECM) is used in vivo and shown to promote constructive remodeling with an M2 macrophage presence [7]. |

| Dynamic Mechanical Analyzers & Rheometers [14] | Characterize viscoelastic properties and time-dependent mechanical behavior of materials. | Used to measure self-healing properties and strain-stiffening behavior of advanced hydrogels mimicking natural tissues [15]. |

| Rodent Skeletal Muscle Injury Model [7] | A standard in vivo model for assessing biocompatibility and functional tissue integration of implants. | Provides a robust platform for evaluating the host remodeling response to materials in a soft tissue location [7]. |

| Multiplex Immunoassays | Simultaneously quantify multiple soluble proteins (e.g., cytokines, chemokines) from cell culture media or tissue lysates. | Critical for analyzing the complex secretory profile of macrophages in the in vitro predictive assay [7]. |

Visualizing the Testing Pipeline and a Key Assay

To clarify the logical workflow of the biomaterial testing pipeline and the specifics of a key predictive assay, the following diagrams were generated using Graphviz.

The development of safe and effective biomaterials is unequivocally dependent on a critical, multi-staged testing pipeline that strategically integrates both in vitro and in vivo methodologies. As demonstrated by the comparative data and protocols, in vitro studies provide an unparalleled platform for high-throughput, cost-effective screening of fundamental material properties and initial biological interactions [11] [9]. Conversely, in vivo testing remains indispensable for validating these findings within the irreducible complexity of a whole living organism, revealing systemic responses and long-term functional outcomes that cannot be fully modeled in a dish [11] [7]. The evolving paradigm in the field is not to view these methods as competitors, but as powerfully complementary tools. The emergence of advanced in vitro systems like Organ-on-a-Chip and sophisticated in silico analytical techniques is actively bridging the translational gap, enhancing predictive power, and refining the path to clinical success [12] [7]. For researchers and drug development professionals, a nuanced understanding of the strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications of each testing approach is fundamental to efficiently navigating the biomaterial development pipeline and delivering innovative solutions to patients.

The ISO 10993 series, developed by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), comprises a set of internationally recognized standards for the biological evaluation of medical devices [16]. These standards provide a systematic framework for assessing the potential biological risks posed by medical devices that come into direct or indirect contact with the human body [17] [18]. The fundamental principle underlying these standards is the evaluation of biocompatibility—defined as the "ability of a medical device or material to perform with an appropriate host response in a specific application" [19]. Compliance with ISO 10993 standards helps ensure that medical devices meet essential safety and performance criteria, thereby contributing to the overall quality and reliability of healthcare products while facilitating global market access [16] [18].

The evaluation process outlined in ISO 10993 is integrated within a risk management framework aligned with ISO 14971, the standard for application of risk management to medical devices [18] [20]. This integration emphasizes that biological evaluation should not be a mere checklist of tests but a science-based, risk-informed process conducted throughout the device lifecycle—from design and development to post-market surveillance [20]. The standards are utilized by medical device manufacturers when preparing various regulatory submissions, including Premarket Applications (PMAs), Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) Applications, and Premarket Notifications (510(k)s) in the United States, and are similarly recognized by other regulatory bodies worldwide [16] [17].

The ISO 10993 Series: A Framework for Biological Safety Assessment

The ISO 10993 series consists of multiple parts, each addressing specific aspects of biological safety evaluation. The following table provides an overview of the key standards within the series:

| Standard Number | Title and Focus Area | Latest Version |

|---|---|---|

| ISO 10993-1 | Evaluation and testing within a risk management process | 2025 (expected) [19] [20] |

| ISO 10993-2 | Animal welfare requirements | 2022 [16] |

| ISO 10993-3 | Tests for genotoxicity, carcinogenicity, and reproductive toxicity | 2014 [16] |

| ISO 10993-4 | Selection of tests for interactions with blood | 2017 [16] |

| ISO 10993-5 | Tests for in vitro cytotoxicity | 2009 [16] |

| ISO 10993-6 | Tests for local effects after implantation | 2016 [16] |

| ISO 10993-7 | Ethylene oxide sterilization residuals | 2008 [16] |

| ISO 10993-9 | Framework for identification and quantification of potential degradation products | 2019 [16] |

| ISO 10993-10 | Tests for skin sensitization | 2021 [16] |

| ISO 10993-11 | Tests for systemic toxicity | 2018 [16] |

| ISO 10993-12 | Sample preparation and reference materials | 2021 [16] [21] |

| ISO 10993-17 | Toxicological risk assessment of medical device constituents | 2023 [16] |

| ISO 10993-18 | Chemical characterization of medical device materials | 2023 [16] |

The Central Role of ISO 10993-1

ISO 10993-1 serves as the cornerstone document of the series, providing the overarching principles and framework for biological evaluation [18]. It guides manufacturers through the process of identifying, assessing, and managing biological risks based on the device's materials, design, and intended use [18]. The standard incorporates key concepts from ISO 14971, including hazard identification, risk estimation, risk evaluation, and risk control, specifically focused on biological harms [20]. The 2025 version of ISO 10993-1 further strengthens this risk-based approach and introduces new considerations such as reasonably foreseeable misuse, which requires manufacturers to consider how devices might be used outside their intended instructions [20].

Categorization of Medical Devices and Test Selection

The biological evaluation process begins with categorizing the medical device based on two primary factors: the nature and duration of body contact. This categorization drives the selection of appropriate biological effects that need evaluation [19].

Contact Duration Categories

ISO 10993-1 defines three distinct categories for contact duration, which are critical in determining the extent of testing required [22]:

| Duration Category | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Limited Exposure | ≤ 24 hours | Single-use surgical instruments, injection needles |

| Prolonged Exposure | >24 hours to 30 days | Temporary implants, wound dressings |

| Long-term Exposure | > 30 days | Permanent implants (e.g., bone screws, pacemakers) |

The 2025 update to ISO 10993-1 provides further clarification on calculating exposure, introducing concepts of total exposure period (number of contact days between first and last use) and distinguishing between daily contact and intermittent contact [20]. Furthermore, it emphasizes that if a device contains chemicals known to bioaccumulate, the contact duration should be considered long-term unless otherwise justified [20].

Nature of Body Contact

The standard classifies devices based on the nature of body contact into three main categories [19]:

- Surface Devices: Contact intact skin, mucosal membranes, or breached/compromised surfaces.

- External Communicating Devices: Indirect contact with blood, tissues, bone, or dentin.

- Implant Devices: Direct contact with bone, tissue, or blood.

The combination of contact duration and nature of body contact determines which biological effects (e.g., cytotoxicity, sensitization, irritation) require evaluation. This relationship is detailed in Table A.1 of ISO 10993-1, which serves as a starting point for developing a biological evaluation plan [19].

The "Big Three" in Biocompatibility Testing

Among the various tests outlined in the ISO 10993 series, three assessments—cytotoxicity, sensitization, and irritation—are considered fundamental and are required for almost all medical devices, regardless of their categorization [21]. These are often referred to as the "Big Three" in biocompatibility testing.

Cytotoxicity Testing (ISO 10993-5)

Purpose: Cytotoxicity testing evaluates whether a medical device or its extracts have the potential to cause cell death or inhibit cell growth [21]. This test serves as an essential screening tool for identifying materials that may be toxic to living cells.

Experimental Protocols:

- Test System: Commonly uses mammalian cell lines such as Balb 3T3 (fibroblasts), L929 (fibroblasts), or Vero (kidney-derived epithelial cells) [21].

- Sample Preparation: Devices are typically tested as extracts prepared by immersing the device in extraction solvents such as physiological saline, vegetable oil, or cell culture medium under specified conditions [21]. ISO 10993-12 provides detailed guidance on sample preparation [16] [21].

- Exposure and Analysis: Cells are exposed to device extracts for approximately 24 hours, after which endpoints including cell viability, morphological changes, cell detachment, and cell lysis are assessed [21].

- Viability Assays: Quantitative methods include MTT, XTT, and neutral red uptake assays. Other methods such as Bradford protein, Chrystal violet, Resazurin dye, and Trypan blue assays are used less frequently [21].

Acceptance Criteria: While ISO 10993-5 does not define strict acceptance criteria, it provides guidance for data interpretation. Cell survival of 70% and above is generally considered a positive indicator, particularly when testing neat extract [21].

Sensitization Testing (ISO 10993-10)

Purpose: This assessment determines whether a medical device has the potential to cause allergic contact dermatitis through repeated or prolonged exposure to device extracts [16] [21].

Experimental Protocols:

- Test System: Traditionally conducted in vivo using guinea pig models (e.g., Guinea Pig Maximization Test or Buehler Test).

- Alternative Approaches: Increasingly, in vitro and in chemico methods are being developed and validated as alternatives to animal testing, aligning with the "3Rs" principles (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement) [21].

- Sample Preparation: Device extracts are prepared using polar and non-polar solvents to ensure comprehensive extraction of potential sensitizers.

Irritation Testing (ISO 10993-23)

Purpose: Irritation testing evaluates the potential of a device, material, or their extracts to cause localized inflammatory responses (irritation) on skin, mucosal membranes, or other applicable tissues [16] [21].

Experimental Protocols:

- Test Systems: Can include in vitro reconstructed human tissue models (e.g., skin or epithelial models) or in vivo models.

- Sample Application: Extracts or materials are applied to the test system, and responses such as redness, swelling, or other signs of inflammation are evaluated.

- Scoring: Responses are typically scored using established grading systems to classify the irritation potential.

In Vitro vs. In Vivo Testing: A Comparative Analysis

The ISO 10993 standards incorporate both in vitro (conducted in controlled laboratory environments outside living organisms) and in vivo (conducted in or on living organisms) testing methodologies [2]. Each approach offers distinct advantages and limitations, which are particularly relevant in the context of biomaterial testing results comparison.

Comparative Analysis of Testing Methodologies

| Parameter | In Vitro Testing | In Vivo Testing |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Tests performed outside living organisms (e.g., in petri dishes, test tubes) [2] | Tests performed within living organisms (animals or humans) [2] |

| Complexity | Lower complexity; reduced biological system interactions [2] [23] | Higher complexity; accounts for whole-organism interactions [2] |

| Control | High degree of environmental control [2] | Limited control due to biological variability [2] |

| Cost & Duration | Generally lower cost and shorter duration [24] | Higher cost and longer duration [2] |

| Ethical Considerations | Minimal ethical concerns [21] | Significant ethical considerations, especially for animal studies [21] |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Well-established for specific endpoints (e.g., cytotoxicity) [21] | Often required for more complex endpoints (e.g., implantation) [16] |

| Predictive Value | May not fully replicate conditions inside living organisms [2] [24] | Provides information on effects in whole, living organisms [2] |

| Standardization | Highly standardized for specific tests (e.g., ISO 10993-5 for cytotoxicity) [21] | Standardized protocols with defined animal welfare requirements (ISO 10993-2) [16] |

The Integrated Testing Approach

The ISO 10993 standards promote a sequential testing approach where in vitro studies often serve as foundational investigations to examine drug interactions and disease processes at the cellular level, while in vivo studies expand on this data by monitoring biological responses in living organisms [2]. According to ISO 10993-1, animal testing should only be conducted when existing scientific data and in vitro studies fail to provide adequate information for a comprehensive safety assessment [21]. This approach aligns with the "3Rs" principles (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement) endorsed in Directive 2010/63/EU [21].

Experimental Workflows in Biological Evaluation

The biological evaluation of medical devices follows a structured, iterative process within a risk management framework. The following diagram illustrates the key stages of this workflow:

Biological Evaluation Workflow in ISO 10993

Test Selection Logic Based on Device Characteristics

The selection of specific tests required for a medical device depends on its categorization according to the nature of body contact and contact duration. The following diagram illustrates this decision-making process:

Test Selection Logic Based on Device Characteristics

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Biocompatibility testing requires specific reagents, materials, and test systems to ensure reliable and reproducible results. The following table details key research reagent solutions used in ISO 10993-compliant testing:

| Reagent/Material | Function in Testing | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Mammalian Cell Lines (L929, Balb/3T3) | Assess cell viability and morphological changes in response to device extracts [21] | Cytotoxicity testing (ISO 10993-5) |

| Extraction Solvents (Saline, DMSO, Vegetable Oil) | Extract leachable substances from device materials under standardized conditions [21] | Sample preparation for multiple test types |

| MTT/XTT/Neutral Red | Colorimetric indicators of cell viability and metabolic activity [21] | Quantitative cytotoxicity assessment |

| Guinea Pigs (Hartley, Dunkin-Hartley) | Traditional model for assessing sensitization potential [21] | Sensitization testing (in vivo) |

| Reconstructed Human Tissues (Skin, Epithelial models) | Alternative to animal testing for irritation and corrosion assessment [21] | In vitro irritation testing |

| Reference Materials (USP, negative/positive controls) | Benchmark for comparing test results and ensuring assay validity [16] [21] | Quality control across test systems |

| Culture Media & Supplements (RPMI, DMEM, FBS) | Support cell growth and maintenance during testing periods [21] | Cell-based assay systems |

The ISO 10993 series provides a comprehensive, risk-based framework for evaluating the biological safety of medical devices, balancing thorough safety assessment with ethical considerations regarding animal testing. The standards emphasize a scientifically rigorous approach that begins with material characterization and device categorization, followed by a tailored testing strategy based on the nature and duration of body contact. While the "Big Three" tests—cytotoxicity, sensitization, and irritation—form the foundation of biocompatibility assessment for nearly all devices, additional evaluations are required based on specific device characteristics and intended use.

The evolving landscape of medical device regulation, particularly the upcoming ISO 10993-1:2025 standard, continues to strengthen the integration of biological evaluation within a risk management framework and introduces important considerations such as reasonably foreseeable misuse. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the comparative advantages and limitations of in vitro versus in vivo testing methodologies remains crucial for designing efficient yet comprehensive biological evaluation plans that meet both scientific and regulatory requirements.

The Fundamental Strengths and Inherent Limitations of Each Approach

In biomedical research, in vitro (Latin for "in glass") and in vivo (Latin for "within the living") represent two fundamental experimental approaches with distinct philosophical and practical applications [10] [25]. In vitro methodologies involve testing biological components—such as cells, tissues, or organs—outside their natural biological context in controlled laboratory environments like petri dishes or test tubes [4]. These systems allow researchers to isolate specific variables and study biological processes in a simplified, reductionist manner. In contrast, in vivo methodologies involve experimentation within intact living organisms, preserving the complex physiological interactions between cells, tissues, and organ systems that characterize biological function [10]. This approach provides a holistic perspective that acknowledges the emergent properties of biological systems.

The choice between these methodologies represents a fundamental trade-off between experimental control and biological relevance. While in vitro systems offer precision and manipulation at the cost of physiological complexity, in vivo systems provide comprehensive biological context at the expense of experimental control [10] [25] [4]. This guide objectively examines the strengths and limitations of each approach within the context of biomaterial testing, providing researchers with evidence-based frameworks for methodological selection and interpretation of results.

Fundamental Principles and Definitions

In Vitro Testing Paradigm

The in vitro paradigm centers on studying biological components in isolation from their native environment. This approach typically utilizes cell cultures that fall into four main types: primary cultures (derived directly from tissues), secondary cultures (subcultures from primary ones), continuous cell lines (which can divide indefinitely), and hybridomas (used for monoclonal antibody production) [10]. Recent technological advances have expanded this paradigm to include more physiologically relevant models such as 3D tissue cultures, organ-on-a-chip systems (microfluidic devices that simulate key human organ functions), and microphysiological systems that recapitulate the function of entire organs in vitro [10] [4]. These systems combine tissue engineering, microfabrication, and biosensors to enable the organization and function of multiple tissue-specific cells over time, better approximating in vivo conditions while maintaining experimental control [4].

In Vivo Testing Paradigm

The in vivo paradigm maintains that meaningful understanding of biological processes requires studying them within the context of intact organisms, where complex interactions between different biological systems remain operational [10]. This approach utilizes whole living organisms, ranging from invertebrate models like Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly) and Danio rerio (zebrafish) to vertebrate models including rodents (mice and rats) and, in specific cases, non-human primates [10]. These models allow observation of the effects of an intervention within the real context of a complete biological system, where the complex interactions between cells, tissues, and organs are preserved [10]. The in vivo approach is particularly valuable for assessing systemic effects, long-term toxicity, and complex pharmacokinetic profiles that emerge from the interplay of multiple biological systems [10] [26].

Comparative Analysis: Strengths and Limitations

Experimental Control and Complexity

The fundamental tension between experimental control and biological complexity represents the core trade-off when selecting between in vitro and in vivo approaches. In vitro systems enable researchers to isolate specific variables through stricter experimental control, reducing interference from systemic variables and improving result reproducibility compared to in vivo models [10]. This controlled environment allows precise manipulation of individual factors—such as pH, temperature, oxygen tension, and nutrient availability—that would be impossible to control in a living organism [10] [27]. However, this control comes at the cost of biological complexity, as in vitro systems cannot capture the inherent complexity of organ systems and the internal environment of the human body [25] [28].

In vivo approaches preserve this complexity, providing full physiological relevance by considering all metabolic processes and organic interactions [10]. The intact organism maintains the natural microarchitecture and compartmentation of organs, which enables compensatory mechanisms that may be lost in vitro [28]. For example, research on ammonia detoxification in liver models demonstrated that the organ's ability to switch metabolic pathways under stress conditions was extremely difficult to reproduce in vitro due to the loss of compartmentalization between periportal and pericentral regions of the liver lobule [28]. This preservation of biological complexity makes in vivo models indispensable for studying emergent properties that arise from system-level interactions.

Physiological Relevance and Human Applicability

The translation of research findings to human applications presents distinct challenges for both approaches. In vitro systems benefit from the ability to use human tissues obtained through surgery or donation, which enhances physiological relevance and human applicability [10]. Advanced systems like organ-on-a-chip technologies and 3D tissue models containing differentiated cell layers can physiologically represent complex tissues and evaluate specific endpoints, providing more human-relevant data than animal models in some contexts [10] [4]. However, these systems face significant limitations, as isolated and cultivated primary cells usually differ strongly from the corresponding cell type in an organism [28]. For example, when primary hepatocytes are isolated from their normal microenvironment, hundreds of genes are up- or down-regulated, potentially altering their response to experimental treatments [28].

In vivo models, particularly those using animal subjects, allow researchers to evaluate interventions within the context of an entire physiological system, including endocrine, nervous, and immune systems that interact in ways that cannot be fully replicated in vitro [10] [29]. However, the use of animal models introduces concerns about translatability due to physiological differences between species [25]. While mice share approximately 95% of their genes with humans, differences in drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion can limit the direct application of animal study results to human contexts [4].

Practical Considerations: Time, Cost, and Throughput

Practical considerations significantly influence methodological selection in research design. In vitro systems generally offer rapid results, are suitable for high-throughput testing, and are economically favorable compared to animal testing [25] [27]. The relative simplicity of these systems enables screening of large compound libraries efficiently, making them ideal for early-stage discovery research [10] [4]. Additionally, technological advances have increased the throughput of in vitro systems while reducing inter-experimental variability through standardized protocols and automated systems [30] [27].

In vivo studies are typically very expensive, require long and extensive timelines, and involve strict regulations and compliance standards due to their use of live subjects [25] [4]. The high costs derive from animal procurement, housing, veterinary care, and the specialized personnel required for animal handling [31]. Additionally, in vivo protocols require approval from Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUCs) and must adhere to evolving ethical standards for animal research, adding administrative burdens to these studies [31].

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of In Vitro and In Vivo Approaches

| Parameter | In Vitro | In Vivo |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Control | High control over variables; reduced systemic interference [10] | Limited control due to complex biological interactions [10] |

| Biological Complexity | Limited; cannot replicate full organ system interactions [32] [25] | High; preserves complete physiological context [10] |

| Physiological Relevance | Enhanced when using human tissues, but cells may dedifferentiate [10] [28] | High for system-level responses, but species differences exist [25] [29] |

| Time Requirements | Relatively fast results [25] [4] | Long and extensive timelines [25] [4] |

| Cost Considerations | Relatively low cost [25] [4] | Very expensive [25] [4] |

| Throughput Capacity | Suitable for high-throughput screening [27] | Limited throughput due to practical constraints [31] |

| Regulatory Oversight | Less stringent than animal studies [25] | Strict regulations and compliance standards [25] [4] |

| Ethical Considerations | Reduced ethical concerns [10] [27] | Significant ethical implications, especially regarding animal use [10] [31] |

Technical Limitations and Methodological Constraints

Both approaches face distinct technical challenges that can impact data interpretation and application. In vitro systems struggle with difficulties in capturing interactions between different cell types, problems in extrapolating from in vivo doses to in vitro concentrations, and challenges in simulating the consequences of long-term exposures [32] [28]. These systems also face limitations in including xenobiotic metabolism into assays and extrapolating from perturbed pathways or biomarkers in vitro to adverse effects in vivo [28]. For example, in vitro skin models cannot recreate the full complexity of human skin, which contains a plethora of cell types including sensory neurons, tissue-resident immune cells, vascular cells, and lymphatic cells [32].

In vivo methodologies contend with higher interindividual variability, which can hinder interpretation in early research stages [10]. This variability stems from genetic differences, environmental factors, and complex biological interactions that are difficult to control [10] [26]. Additionally, in vivo models can produce confounding results due to systemic compensation mechanisms that may mask direct effects of an intervention [29]. For instance, in immune system research, the redundancy of signaling pathways in intact organisms can complicate the interpretation of gene knockout studies, as other pathways may compensate for the lost function [29].

Experimental Applications and Case Studies

Cytotoxicity Testing of Biomaterials

Cytotoxicity testing represents a critical application where both approaches provide complementary information. The ISO 10993-5 standard identifies three types of cytotoxicity tests: extract tests, direct contact tests, and indirect contact tests [30]. A recent study on Mg-1%Sn-2%HA composite for orthopedic implants demonstrated a standardized in vitro approach using L-929 mouse fibroblast cells cultured at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for 7 days [30]. The researchers used the elution technique in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS) to prepare extracts, which were then evaluated microscopically for aberrant cell morphology and degeneration, followed by quantitative cell toxicity assessment using the MTT method [30].

The results indicated high cell viability of 71.51% with the undiluted extract preparation, confirming the non-cytotoxic properties of the composite [30]. Furthermore, cell viability improved with dilution, attaining 84.93%, 93.20%, and 96.52% at concentrations of 50%, 25%, and 12.5%, respectively [30]. No notable morphological alterations or indications of cellular deterioration were observed [30]. This in vitro data provided preliminary safety evidence before proceeding to more complex and costly in vivo studies, demonstrating how in vitro approaches can serve as efficient screening tools in biomaterial development.

Drug Combination Studies in Oncology

Drug combination therapy represents another area where both approaches provide essential, complementary data. While in vitro models offer efficient platforms for initial synergy screening, in vivo models better capture tumor heterogeneity and mimic tumor molecular features and treatment responses [26]. However, in vivo models often demonstrate substantial heterogeneity in treatment effects among animals, which, while closely reflecting clinical outcomes, poses challenges for accurate evaluation of treatment responses [26].

The SynergyLMM framework was developed specifically to address the statistical challenges of in vivo drug combination studies [26]. This comprehensive modeling approach accommodates complex experimental designs, including multi-drug combinations, and offers practical options for statistical analysis of both synergy and antagonism through longitudinal drug interaction analysis [26]. The method supports the use of various synergy scoring models, such as Bliss independence, Highest Single Agent (HSA), and Response Additivity (RA), accompanied by uncertainty quantification and statistical assessment [26].

In a reanalysis of drug combination experiments from Narayan et al., SynergyLMM revealed important nuances that simple endpoint analyses missed [26]. For the U87-MG Fluc-Mcherry orthotopic glioblastoma model with Docetaxel + GNE-317 combination, the analysis showed significant synergy under the HSA model but not enough statistical evidence to reject additivity under the Bliss model [26]. This contrasted with the original authors' conclusions using the median-effect principle, demonstrating how methodological choices can significantly impact interpretation of in vivo results.

Table 2: Experimental Considerations for In Vivo Drug Combination Studies

| Consideration | Challenge | SynergyLMM Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal Data | Traditional endpoint analyses lose temporal information [26] | Uses all longitudinal measurements to capture dynamic effects [26] |

| Reference Models | Different models (Bliss, HSA, RA) can yield conflicting results [26] | Supports multiple reference models to assess conclusion robustness [26] |

| Inter-animal Variability | High heterogeneity complicates effect detection [26] | Uses mixed effects models to account for inter-animal variation [26] |

| Experimental Design | Determining appropriate animal numbers and measurement frequency [26] | Provides power analysis tools to optimize study design [26] |

| Model Selection | Choosing appropriate tumor growth kinetics model [26] | Supports both exponential and Gompertz growth models with diagnostics [26] |

Immunological Applications

Immunological research particularly highlights the complementary strengths of both approaches. In vitro models are invaluable for reducing the complexity of the immune system to manageable components, allowing detailed study of specific signaling pathways and mediator release [29]. For example, in vitro systems have been essential for delineating the molecular mechanisms of Toll-like receptor recognition and the cytolytic machinery of natural killer cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes [29]. These reductionist approaches enable researchers to isolate specific immune functions without the confounding effects of entire system integration.

However, the immune system fundamentally operates through complex cellular interactions and spatial organizations that are difficult to reconstruct in vitro [29]. The transition of immune cells from blood vessels to tissues, for instance, involves a coordinated multi-step process (rolling, activation, firm adhesion, and transmigration) that depends on the vascular architecture and flow conditions not easily replicated in vitro [29]. Similarly, the compartmentalization of immune responses between primary and secondary lymphoid organs represents a system-level property that requires intact organisms for meaningful study [29]. Therefore, while in vitro systems provide mechanistic insights, in vivo models remain essential for understanding immune function in physiologically relevant contexts.

Experimental Design and Methodological Protocols

Standardized In Vitro Cytotoxicity Testing

For biomaterial cytotoxicity assessment, researchers should follow established standards such as ISO 10993-5, which provides frameworks for test selection and implementation [30]. A typical protocol involves:

Sample Preparation: Using the elution method to prepare extracts in culture medium supplemented with serum, with incubation typically ranging from 24-72 hours at 37°C [30].

Cell Culture: Maintaining appropriate mammalian cells (e.g., L-929 mouse fibroblast cells) under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂) for a specified period, typically 7 days [30].

Assessment Methods:

- Microscopic Evaluation: Examining cell monolayers for aberrant morphology and degeneration [30].

- Quantitative Assessment: Using methods like MTT assay, which measures mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity by converting yellow MTT to purple formazan crystals, with absorbance measurement at 492 nm [30].

- Alternative Assays: Including colorimetric (MTS, XTT, LDH), fluorometric (CFDA-AM, alamar blue), and luminometric (ATP assay) approaches depending on research needs [30].

Interpretation: Comparing results to appropriate controls and established benchmarks for cytotoxicity classification [30].

This standardized approach ensures reproducibility and facilitates comparison across different studies and laboratories, providing reliable preliminary safety data for biomaterial development.

Advanced In Vivo Combination Therapy Studies

For in vivo drug combination studies, proper experimental design and statistical analysis are crucial for robust conclusions. The SynergyLMM framework provides a comprehensive workflow:

Input Data Collection: Longitudinal tumor burden measurements (e.g., volume, luminescence) in various treatment groups and control animals, normalized against treatment initiation time points [26].

Model Selection: Choosing between exponential or Gompertz tumor growth kinetics based on model diagnostics and performance metrics [26].

Statistical Modeling: Applying linear mixed effects models (exponential growth) or non-linear mixed effects models (Gompertz growth) to estimate growth parameters for each treatment group [26].

Model Diagnostics: Checking model assumptions, identifying outlier observations, and assessing influential subjects [26].

Synergy Assessment: Calculating time-resolved synergy scores using appropriate reference models (Bliss, HSA, or RA) with uncertainty quantification and statistical significance evaluation [26].

Power Analysis: Conducting post-hoc power analysis of completed experiments or a priori power analysis for new experiments to determine appropriate sample sizes and measurement frequencies [26].

This comprehensive approach addresses the specific challenges of in vivo combination studies, particularly the longitudinal nature of tumor growth measurements and substantial inter-animal heterogeneity [26].

Diagram 1: Methodological Selection Framework for Biomaterial Testing. This decision pathway illustrates the fundamental trade-offs between experimental control and biological complexity when selecting between in vitro and in vivo approaches.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of either methodology requires appropriate selection of research reagents and materials. The following table details essential components for representative experiments in both approaches:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for In Vitro and In Vivo Studies

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Media | In vitro systems | Provide essential nutrients for cell growth and maintenance | Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with fetal bovine serum (FBS) [30] |

| Biomaterial Extracts | In vitro cytotoxicity | Evaluate leachable substances from test materials | Mg-1%Sn-2%HA composite extracts in culture medium [30] |

| Viability Assays | In vitro assessment | Quantify cell health and metabolic activity | MTT assay, ATP assays, fluorometric assays [30] |

| Animal Models | In vivo studies | Provide complete biological context for testing | Rodent models, zebrafish, non-human primates [10] |

| Tumor Measurement Tools | In vivo oncology | Monitor disease progression and treatment response | Caliper measurements, luminescence imaging [26] |

| Statistical Frameworks | In vivo data analysis | Analyze complex longitudinal data and synergy | SynergyLMM for drug combination studies [26] |

The fundamental strengths and inherent limitations of in vitro and in vivo approaches underscore their essential complementarity in biomaterial testing. Rather than viewing these methodologies as mutually exclusive, researchers should recognize their synergistic potential when strategically integrated within a structured research program [10]. In vitro systems provide unparalleled efficiency, control, and mechanistic insights for early-stage screening and hypothesis generation, while in vivo models deliver indispensable physiological context and system-level validation for promising candidates [10] [25] [4].

This complementary relationship is reflected in evolving regulatory frameworks that acknowledge the value of both approaches. The European Union's REACH regulation prioritizes alternative methods over animal testing in the chemical sector, while the FDA and other agencies have begun accepting data generated through advanced in vitro platforms in pharmacology and toxicology contexts [10]. Similarly, the role of EURL ECVAM (European Union Reference Laboratory for Alternatives to Animal Testing) has been crucial in validating, harmonizing, and promoting in vitro and alternative studies while recognizing the current necessity of in vivo approaches for complex endpoints [10].

The future of biomaterial testing lies not in exclusive reliance on one approach, but in the continued development of more physiologically relevant in vitro systems and more refined, humanized in vivo models that collectively enhance predictive accuracy while addressing ethical concerns. Through strategic integration of both methodologies, researchers can maximize scientific rigor while advancing the fundamental goals of replacement, reduction, and refinement of animal use in research—the essential 3Rs principle that guides ethical scientific progress [10] [27].

The implantation of a biomaterial initiates a complex and predictable sequence of biological events known as the biological response continuum. This process begins with acute inflammation and progresses through chronic inflammation, granulation tissue development, and ultimately culminates in fibrous encapsulation—a process scientifically termed the foreign body response (FBR) [33]. Understanding this continuum is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals who must navigate the challenging transition from in vitro analysis to in vivo performance. The FBR represents a significant clinical challenge as it can compromise the functionality and long-term performance of implanted biomaterials, potentially leading to implant failure and compromised tissue regeneration [33]. This biological cascade occurs consistently across diverse biomaterial applications, including medical implants, drug delivery systems, and tissue engineering scaffolds, making its understanding fundamental to biomaterial research and development.

The foreign body response is not a single event but rather a synergistically destructive process involving proinflammatory macrophages and activated fibroblasts that drive uncontrolled inflammation and excessive fibrosis [33]. This complex interplay between the immune system and the implanted material determines the ultimate fate of any medical device introduced into the biological environment. The clinical significance of this process cannot be overstated, as the chronic damage resulting from implant rejection often outweighs the intended healing benefits, presenting a considerable challenge when implementing treatment-based biomaterials [33]. Consequently, comprehensive understanding of the biological response continuum is essential for developing safer and more effective biomaterials that can successfully integrate with host tissues.

The Foreign Body Response: A Stage-Based Paradigm

Phase Progression and Key Cellular Players

The foreign body response follows a well-defined sequence of biological events that occur when a biomaterial is introduced into living tissue. While the exact timing may vary based on material properties and implantation site, the fundamental progression remains consistent across most biomaterial applications [33]. The process begins immediately upon implantation and can continue for the duration of the material's presence in the body.

Table 1: Stages of the Foreign Body Response

| Stage | Time Frame | Key Cellular Players | Primary Molecular Mediators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Adsorption | Immediate (seconds to minutes) | Plasma proteins (fibrinogen, albumin, immunoglobulins) | Complement proteins, coagulation factors |

| Acute Inflammation | 0-48 hours | Neutrophils | Reactive oxygen species (ROS), antimicrobial peptides, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) |

| Chronic Inflammation/Macrophage Activity | 48 hours onward | Macrophages, monocytes | TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-4, IL-10, IL-13 |

| Foreign Body Giant Cell Formation | Days to weeks | Multinucleated giant cells (fused macrophages) | Acid hydrolases, proteases, reactive oxygen species |

| Fibrous Capsule Formation | Weeks to months | Fibroblasts, myofibroblasts | TGF-β, PDGF, VEGF, collagen deposits |

Following protein adsorption, neutrophils swiftly dominate the acute inflammatory phase, arriving at the implantation site within hours [33]. These innate immune cells demonstrate potent phagocytic capabilities, engulfing foreign particles, debris, and potential pathogens associated with the biomaterial. Neutrophils also release an array of antimicrobial molecules, including reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antimicrobial peptides, which effectively eradicate potential threats and ensure tissue sterility [33]. Beyond their defensive role, neutrophils secrete various growth factors and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that initiate extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling—a crucial process for subsequent tissue integration or repair [33].

Within approximately 48 hours, a cellular transition occurs as neutrophils are gradually replaced by macrophages, marking the shift from acute inflammation to the chronic foreign body response [33]. Macrophages are pivotal regulators of this phase, possessing the ability to continuously proliferate and release chemotactic factors that recruit additional immune cells to the implantation site. These cells exert sophisticated control over the immune response through polarization—adopting distinct functional phenotypes based on local environmental cues [33]. The classically activated M1 macrophages exhibit proinflammatory properties and drive the FBR through the release of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 [33]. In contrast, alternatively activated M2 macrophages coordinate anti-inflammatory responses and tissue remodeling through the secretion of IL-13, IL-10, and IL-4 [33].

When macrophages encounter biomaterials that resist phagocytosis due to size or structural properties, they may fuse together to form foreign body giant cells (FBGCs) [33]. These large multinucleated cells adhere persistently to biomaterial surfaces and release degradative enzymes including acid hydrolases, proteases, and reactive oxygen species. This enzymatic activity can lead to chronic inflammation and potentially compromise biomaterial functionality through surface degradation [33]. The presence of FBGCs represents a hallmark of the foreign body response and serves as a key indicator in histopathological evaluations of biomaterial compatibility.

The final phase of the biological response continuum involves the development of fibrous encapsulation, where fibroblasts are recruited to the implantation site and activated to deposit collagenous matrix [33]. This process is driven by growth factors released by macrophages, platelets, and adipocytes in the wound environment, particularly platelet-derived growth factors (PDGF), transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), and vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF) [33]. The resulting fibrous capsule effectively walls off the implant from surrounding tissues, a biological attempt to isolate the foreign material that often compromises the intended function of medical devices and tissue engineering constructs.

Figure 1: The Foreign Body Response Cascade. This diagram illustrates the sequential biological events following biomaterial implantation, from initial protein adsorption to final fibrous encapsulation, highlighting key cellular players at each stage.

Comparative Experimental Models: In Vitro vs. In Vivo Assessment

The Translational Challenge

A critical challenge in biomaterial development lies in the significant disconnect between in vitro assessments and in vivo outcomes. A comprehensive multicenter review from the European consortium BioDesign, which analyzed data from 36 in vivo studies and 47 in vitro assays testing 93 different biomaterials, revealed a "surprisingly poor correlation between in vitro and in vivo testing of biomaterials for bone regeneration" [34]. The study found no significant overall correlation between in vitro and in vivo outcomes, with mean in vitro scores showing only a 58% trend of covariance to in vivo scores [34]. This substantial discrepancy highlights the inadequacies of current in vitro assessment methods and underscores the need for novel approaches to in vitro biomaterial testing and validated preclinical pipelines.

The biological complexity of in vivo environments introduces variables that are exceptionally difficult to replicate in laboratory settings. The immune response sensitivity differs significantly between connective tissue and bone tissue, with connective tissue generally responding more sensitively to foreign bodies such as bone substitute materials [35]. This was demonstrated in a comparative study of a novel hybrid bone substitute material, where subcutaneous implants elicited stronger inflammatory reactions with higher counts of polymorphonuclear cells, lymphocytes, multinucleated giant cells, and plasma cells at day 10, alongside consistently elevated irritancy scores compared to calvaria implants [35]. In contrast, calvaria implants showed increased neovascularization, reflecting bone-specific regenerative processes [35]. These findings underscore how implantation site dramatically influences immune activation, vascularization, and biomaterial resorption.

Standardized Methodologies for Biocompatibility Assessment

To ensure consistent evaluation across studies, researchers rely on standardized protocols for assessing biocompatibility and host tissue responses. The DIN EN ISO 10993-6 standard provides a critical framework for the macroscopic and microscopic evaluation of tissue responses to implanted materials, specifically addressing local effects after implantation [35]. This standard employs histopathological analysis to assess parameters such as inflammation, fibrosis, neovascularization, and bone remodeling through semi-quantitative scoring of cellular and tissue reactions surrounding the implant [35]. Histological sections are typically examined and scored on a 0 to 4 scale for various cell types (e.g., polymorphonuclear cells, lymphocytes, macrophages, giant cells) and tissue changes (e.g., necrosis, fibrosis, neovascularization) [35]. These scores calculate a total irritation or tissue response score, which helps classify a material's biocompatibility as non-irritant, slightly irritant, moderately irritant, or severely irritant.

For regulatory approval of bone substitute materials—particularly in the EU under Medical Device Regulation (MDR) or in the US under FDA guidance—both subcutaneous and calvarial implantation models in rats are frequently used in a stepwise preclinical testing strategy [35]. Initial biocompatibility and safety are typically assessed via subcutaneous implantation, while functional evaluation in bone tissue is tested using calvarial defect models or other load-bearing defect models, depending on the intended application [35]. Data from these models form essential components of the technical documentation submitted for regulatory review, demonstrating that materials are safe, biocompatible, and effective in supporting bone regeneration.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Implantation Models Based on ISO 10993-6 Standards

| Assessment Parameter | Subcutaneous Model | Calvarial Defect Model | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorphonuclear Cells | Higher counts at day 10 | Lower counts at day 10 | p≤0.05* |

| Lymphocytes | Elevated throughout study | Reduced presence | p≤0.05* |