Bioprinting the Future: How 3D Printed Scaffolds Are Revolutionizing Tissue Engineering & Regenerative Medicine

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of 3D printed scaffolds for tissue regeneration, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Bioprinting the Future: How 3D Printed Scaffolds Are Revolutionizing Tissue Engineering & Regenerative Medicine

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of 3D printed scaffolds for tissue regeneration, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of biomaterials and scaffold design, details advanced fabrication methodologies and specific tissue applications, addresses common technical challenges and optimization strategies, and evaluates validation protocols and comparative performance against traditional methods. The review synthesizes current research and future trajectories, offering a roadmap for translating 3D bioprinting from the lab to clinical and pharmaceutical applications.

The Building Blocks of Regeneration: Core Principles of 3D Printed Tissue Scaffolds

Within the framework of a doctoral thesis on 3D-printed scaffolds for tissue regeneration, the "ideal" scaffold is not a universal construct but a biomaterial meticulously engineered to meet specific biochemical and biophysical criteria. The triumvirate of Biocompatibility, Porosity, and Mechanics forms the foundational pillar for in vitro cell viability, differentiation, and ultimate in vivo integration and function. This document synthesizes current research into actionable application notes and protocols for researchers and development professionals.

Table 1: Key Parameter Benchmarks for 3D-Printed Tissue Scaffolds

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Measurement Technique | Impact on Regeneration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Porosity | 60 - 90% | Micro-CT Analysis, Mercury Porosimetry | Facilitates cell infiltration, vascularization, and nutrient/waste diffusion. |

| Pore Size | |||

| - Bone Regeneration | 100 - 500 µm | SEM Image Analysis | Osteoconduction; capillary formation. |

| - Cartilage Regeneration | 150 - 300 µm | SEM Image Analysis | Chondrocyte encapsulation & ECM production. |

| - Vascular Ingrowth | ≥ 200 µm | SEM Image Analysis | Minimum for capillary invasion. |

| Interconnectivity | > 99% | Micro-CT Analysis | Essential for uniform tissue formation. |

| Elastic Modulus (Bone) | 0.5 - 20 GPa (matching target tissue) | Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA), Compression Testing | Mechanotransduction; prevents stress shielding. |

| Degradation Rate | Match neo-tissue formation rate (weeks-months) | In vitro Mass Loss / GPC | Maintains structural integrity until new tissue bears load. |

| Surface Roughness (Ra) | 1 - 10 µm | Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Enhances protein adsorption and cell adhesion. |

Table 2: Common Biomaterials and Their Properties for 3D Printing

| Material Class | Example Materials | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Typical Printing Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Polymers | PCL, PLGA, PLA | Tunable mechanics/degradation, consistent quality | Often hydrophobic, lacks bioactivity | FDM, Melt Electrospinning Writing |

| Natural Polymers | Alginate, Collagen, Hyaluronic Acid, Silk Fibroin | Inherent bioactivity, cell-binding motifs | Low mechanical strength, batch variability | Extrusion-based, Bioprinting |

| Ceramics | β-Tricalcium Phosphate (β-TCP), Hydroxyapatite (HA) | Osteoconductive, high compressive strength | Brittle, difficult to print pure | Binder Jetting, SLA/DLP |

| Composites | PCL/HA, GelMA/Hydroxyapatite | Combines advantages of components | Complexity in printability & characterization | Multi-head Extrusion, SLA/DLP |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessment of Scaffold Porosity and Interconnectivity via Micro-CT

Objective: To quantitatively determine the total porosity, pore size distribution, and degree of pore interconnectivity of a 3D-printed scaffold.

Materials: Scaffold sample (dry, ~5-10mm cube), micro-CT scanner (e.g., SkyScan 1272), analysis software (e.g., CTAn, ImageJ).

Procedure:

- Mounting: Secure the scaffold sample firmly on the specimen stage using low-density foam or clay to prevent movement.

- Scanning Parameters: Set appropriate scanning parameters (e.g., 10-15 µm pixel size, 40-70 kV voltage, 0.5 mm Al filter). Perform a 180° or 360° rotation with a step rotation of 0.4°.

- Reconstruction: Use the scanner's software (e.g., NRecon) to reconstruct 2D cross-sectional images from projections. Apply consistent beam hardening and ring artifact correction.

- Binarization (CTAn):

- Import reconstructed image stack.

- Apply a uniform global threshold to segment scaffold material from pore space. Validate threshold using histogram analysis.

- 3D Analysis:

- Calculate Total Porosity (%) as (Volume of Pores / Total Volume) * 100.

- Perform Pore Size Distribution analysis using sphere-fitting algorithm.

- Perform Interconnectivity Analysis: Define a region of interest (ROI). Use the "Analyze Particles" or "3D Object Counter" function in ImageJ, or the dedicated tool in CTAn, to identify and count structures connected to the scaffold exterior. Interconnectivity = (Volume of interconnected pores / Total pore volume) * 100.

- Visualization: Generate 3D models and virtual sections for qualitative assessment.

Protocol 2:In VitroBiocompatibility and Cell-Scaffold Interaction Assay

Objective: To evaluate scaffold cytocompatibility, cell adhesion, proliferation, and morphology.

Materials: Sterilized scaffold (e.g., ethanol immersion, UV, or gamma irradiation), relevant cell line (e.g., MC3T3-E1 for bone, hMSCs), complete growth medium, calcein-AM/ethidium homodimer-1 (LIVE/DEAD kit), phalloidin/DAPI staining solutions, SEM fixatives.

Procedure:

- Pre-conditioning: Soak scaffolds in culture medium for 24h prior to seeding to improve wettability.

- Cell Seeding: Use dynamic seeding (agitation) or static seeding with a high-density cell suspension (e.g., 1x10^5 cells/scaffold). Centrifuge scaffolds post-seeding (500 rpm, 5 min) to enhance infiltration.

- Culture: Maintain under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO2), changing medium every 2-3 days.

- Viability & Proliferation (Days 1, 3, 7):

- LIVE/DEAD Staining: Incubate scaffolds in dye solution per manufacturer's protocol. Image via confocal microscopy. Quantify live/dead cell ratio.

- Metabolic Assay (e.g., AlamarBlue/CCK-8): Incubate scaffolds in assay reagent. Measure fluorescence/absorbance. Plot metabolic activity over time.

- Cell Morphology (Day 3):

- Fluorescence (F-actin & Nuclei): Fix (4% PFA), permeabilize (0.1% Triton X-100), stain with phalloidin (F-actin) and DAPI (nuclei). Image via confocal to visualize cell spreading and cytoskeletal organization.

- SEM Imaging: Fix (2.5% glutaraldehyde), dehydrate in graded ethanol series, critical point dry, and sputter-coat with gold. Image to observe detailed cell attachment and morphology.

Protocol 3: Uniaxial Compression Testing for Mechanical Characterization

Objective: To determine the compressive modulus and strength of a porous scaffold.

Materials: Hydrated or dry scaffold samples (cylindrical, aspect ratio ~2:1, e.g., 8mm diameter x 4mm height), universal mechanical tester (e.g., Instron) with calibrated load cell (e.g., 500N) and compression plates, PBS (for hydrated testing).

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Measure exact sample dimensions (diameter, height) with calipers. For hydrated testing, keep samples immersed in PBS until immediate testing.

- Tester Setup: Zero the load cell and position. Lower the upper plate to just contact the sample surface (pre-load of ~0.01N). Set the crosshead speed to 1 mm/min.

- Testing: Compress the sample to 50-60% strain or until failure. Record force and displacement data.

- Data Analysis:

- Convert force-displacement data to stress-strain (Stress = Force / Initial Cross-sectional Area; Strain = Displacement / Initial Height).

- Generate a stress-strain curve. Identify the linear elastic region (typically between 5-15% strain).

- Calculate the Compressive Modulus (E) as the slope of the linear elastic region.

- Determine the Compressive Strength as the maximum stress before a 10% drop in load-bearing capacity or at a specific offset strain (e.g., 30%).

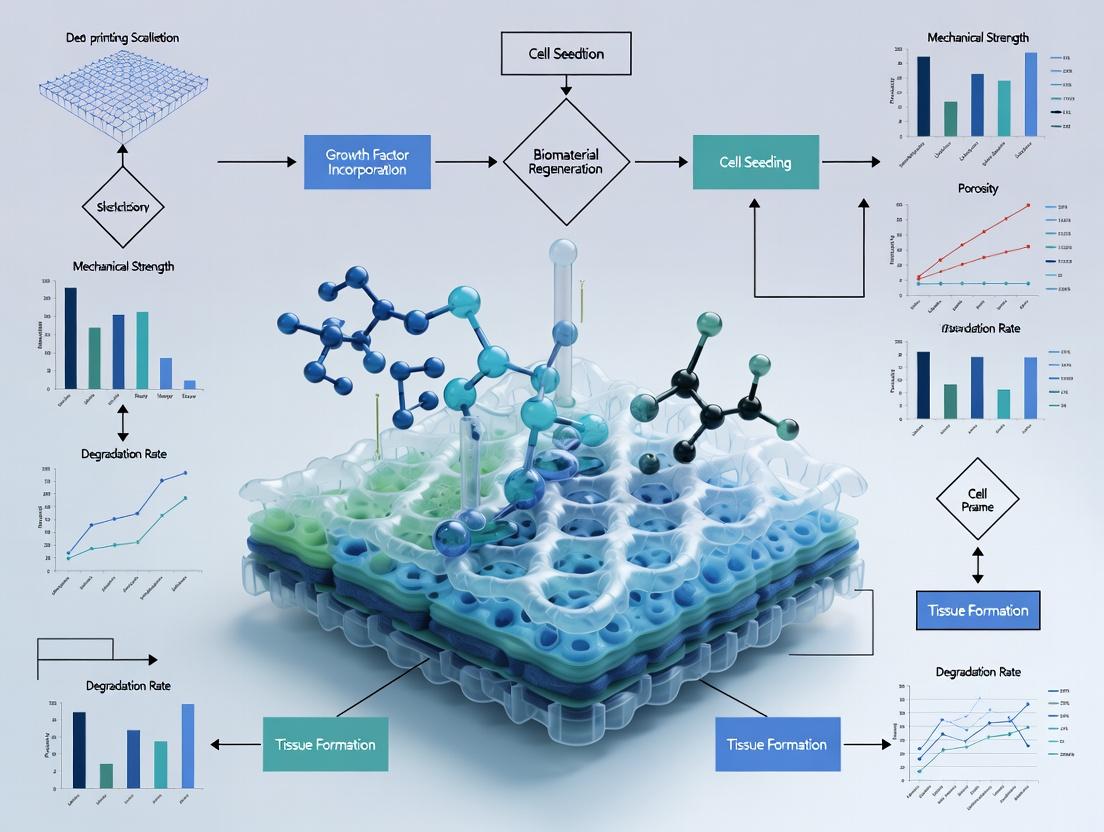

Diagrams

Diagram 1: Scaffold Design-Parameter-Outcome Relationship

Diagram 2: Workflow for Scaffold Evaluation in Regeneration Research

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Scaffold Evaluation

| Category | Item / Reagent | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Biomaterial Printing | Polycaprolactone (PCL) Pellet/Granule | A biocompatible, slow-degrading synthetic polymer offering excellent printability via FDM, serving as a gold-standard base material for mechanical scaffolds. |

| Bioink Formulation | Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | A photocrosslinkable hydrogel derived from gelatin; provides natural cell-adhesive motifs (RGD) for bioprinting cell-laden soft tissue constructs. |

| Cell Culture & Seeding | Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (hMSCs) | A primary multipotent cell source for evaluating osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic differentiation potential on scaffolds under biochemical/mechanical cues. |

| Viability Staining | Calcein-AM / Ethidium Homodimer-1 (LIVE/DEAD Kit) | Dual-fluorescence stain for simultaneous visualization of live (green, calcein) and dead (red, EthD-1) cells adherent within 3D scaffolds. |

| Cytoskeleton Staining | Phalloidin (FITC/TRITC conjugated) | High-affinity actin filament stain used to visualize cell spreading, morphology, and cytoskeletal organization on scaffold surfaces via confocal microscopy. |

| Molecular Analysis | TRIzol Reagent / RNeasy Kit | For total RNA isolation from cells seeded on 3D scaffolds—a critical, often challenging, first step for qPCR analysis of differentiation markers. |

| Histology | Osteocalcin Antibody (Anti-OCN) | A key immunohistochemistry (IHC) target for specific detection of mature osteoblasts and bone matrix formation in in vivo explants. |

| Mechanical Testing | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), 1x | Hydration medium for testing scaffolds under physiologically relevant wet conditions, preventing premature drying during compression/DMA tests. |

Within the thesis framework of 3D printing scaffolding for tissue regeneration, the selection of biomaterial is paramount. This document provides detailed Application Notes and Protocols for six cornerstone polymers, focusing on their utility in extrusion-based (e.g., FDM, bioprinting) and light-based (e.g., DLP) 3D printing for creating regenerative scaffolds.

Application Notes & Quantitative Comparison

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Featured Biomaterials for 3D Printing Scaffolds

| Polymer | Type | Key Properties (for 3D Printing) | Degradation Time (Typical) | Mechanical Strength (Range) | Typical Crosslinking Method | Primary Tissue Target(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA | Synthetic | High modulus, thermoplastic, brittle | 12-24 months | 50-70 MPa (Tensile) | Melt Fusion | Bone, Hard Tissue |

| PCL | Synthetic | Low Tg, ductile, slow-degrading | 2-4 years | 20-40 MPa (Tensile) | Melt Fusion | Bone, Cartilage (long-term) |

| PEG | Synthetic | Hydrophilic, tunable mechanics, bioinert | Days to Months (on MW) | 0.1-10 MPa (Compressive) | Photo (e.g., UV) | Soft Tissue, Drug Delivery |

| Collagen | Natural | Excellent cell adhesion, low mechanics, denatures | Weeks to Months | 1-10 MPa (Compressive - crosslinked) | Thermal, Chemical (e.g., glutaraldehyde), UV | Skin, Bone, Vascular, General ECM |

| Alginate | Natural | Rapid ionic gelation, low cell adhesion | Hours to Weeks (ionically crosslinked) | 5-50 kPa (Compressive - hydrogel) | Ionic (Ca²⁺), Covalent (e.g., Ca²⁺ + covalent modifiers) | Cartilage, Wound Dressings, Bioink Base |

| Hyaluronic Acid | Natural | CD44 receptor binding, highly hydrated, shear-thinning | Days to Weeks (enzymatic) | 0.5-30 kPa (Compressive - hydrogel) | Photo (e.g., Methacrylation + UV), Click Chemistry | Cartilage, Neural, Dermal |

Table 2: Recommended 3D Printing Parameters & Bioink Formulations

| Polymer | Recommended Printing Format | Key Formulation/Processing Notes | Critical Parameter | Target Scaffold Porosity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA | FDM | Filament diameter: 1.75 mm | Nozzle Temp: 190-220°C; Bed Temp: 60°C | 40-70 |

| PCL | FDM | Filament diameter: 1.75 mm | Nozzle Temp: 70-120°C; Bed Temp: 25-40°C | 50-80 |

| PEGDA | DLP/SLA | MW: 700-10,000 Da; Photoinitiator (e.g., LAP 0.1-0.5% w/v) | UV Wavelength: 365-405 nm; Exposure: 5-30 s/layer | 60-90 |

| Collagen | Extrusion Bioprinting | Neutralized Type I (3-10 mg/mL), kept at 4°C pre-print | Printing Temp: 4-10°C; Post-print Incubation: 37°C for gelation | 85-99 |

| Alginate | Extrusion Bioprinting | 2-4% (w/v) in PBS/Cell Media; CaCl₂ crosslinking bath (50-200 mM) | Printing Pressure: 15-30 kPa; Nozzle: 22-27G | 80-95 |

| Hyaluronic Acid | Extrusion/DLP | Methacrylated (MeHA, 1-3% w/v); Photoinitiator for DLP | Crosslink: UV (365nm, 5-60s) or Ionic/Covalent post-print | 75-95 |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: FDM Printing of PLA/PCL Composite Scaffolds for Bone Regeneration Objective: To fabricate a porous, bioactive composite scaffold for osteoconduction.

- Material Preparation: Dry PLA and PCL pellets at 60°C for 4h. Create composite filament via twin-screw extrusion (e.g., 70:30 PCL:PLA) with 5% w/w incorporated β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP).

- Printer Setup: Calibrate FDM printer bed. Load composite filament.

- Printing: Use slicing software to design a 0/90° laydown pattern with 300μm strand diameter, 500μm inter-strand spacing. Print with nozzle at 185°C (PCL-rich), bed at 35°C. Layer height: 200μm.

- Post-processing: Anneal at 60°C for 1h to reduce internal stresses. Sterilize with 70% ethanol (24h) followed by UV exposure (30 min/side).

Protocol 2: Photocrosslinking of PEGDA Hydrogels for Cell Encapsulation Objective: To create a cytocompatible, tunable 3D hydrogel network for soft tissue models.

- Precursor Solution: Dissolve PEGDA (MW 3400) at 10% (w/v) in sterile PBS. Add 0.1% (w/v) lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) photoinitiator. Protect from light. Filter sterilize (0.22μm).

- Cell Mixing: Centrifuge target cells (e.g., mesenchymal stem cells). Resuspend in precursor solution at 5 x 10⁶ cells/mL. Keep on ice.

- DLP Printing/Crosslinking: Pour solution into a resin vat. Use a DLP projector (405 nm) to project layer patterns (50μm layers). Exposure time: 15 seconds per layer.

- Post-print Handling: Rinse printed construct 3x in PBS to remove uncrosslinked polymer. Culture in complete media.

Protocol 3: Coaxial Bioprinting of Cell-Laden Alginate Tubes for Vascularization Objective: To print perfusable, cell-laden tubular structures mimicking vasculature.

- Bioink Preparation: (Core) Prepare 3% (w/v) alginate in cell culture medium. Mix with human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) at 8 x 10⁶ cells/mL. (Shell) Prepare 4% (w/v) alginate (cell-free). Load into separate syringes.

- Crosslinker Preparation: Prepare 100 mM CaCl₂ in PBS.

- Coaxial Printing Setup: Assemble a coaxial printhead on a bioprinter. Connect core and shell ink syringes. Position nozzle over a bath of CaCl₂ solution.

- Printing: Print tubular structures directly into the crosslinking bath. Parameters: Core flow rate: 80 μL/min, Shell flow rate: 120 μL/min; Print speed: 8 mm/s; Nozzle height in bath: 5 mm.

- Maturation: Transfer tubes to culture media after 5 min ionic crosslinking. Culture under static conditions for 24h, then apply gradual perfusion.

Visualization

Title: Biomaterial Processing Paths for 3D Printed Scaffolds

Title: HA Hydrogel: Crosslinking & Cell Signaling Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for 3D Printing Biomaterial Scaffolds

| Item | Function in Research | Example Product/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| Methacrylated Hyaluronic Acid (MeHA) | Provides photo-crosslinkable backbone for DLP or extrusion bioprinting; enables tunable mechanics and bioactivity. | Glycosil (Advanced BioMatrix) or in-house synthesis. |

| Lithium Phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | A cytocompatible, water-soluble photoinitiator for UV (365-405 nm) crosslinking of polymers like PEGDA and MeHA. | Sigma-Aldrich, 900889 or TCI L0231. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) Solution | Ionic crosslinker for alginate; used in bath or co-axial printing to instantaneously form hydrogels. | Sterile, cell culture tested 0.1-1M solution. |

| Type I Collagen, High Concentration | Native ECM protein for bioinks; requires neutralization and cold handling to form thermosensitive gels. | Corning Rat Tail Collagen I, 354249 (≥8 mg/mL). |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) | Synthetic, bioinert hydrogel precursor with controllable mesh size via MW and concentration; for DLP/SLA. | Sigma-Aldrich, various MWs (575, 3400, 10000). |

| β-Tricalcium Phosphate (β-TCP) Powder | Osteoconductive ceramic additive for composite filaments (with PLA/PCL) to enhance bone regeneration. | Sigma-Aldrich, 642631 (≤50μm particle size). |

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Versatile, cell-adhesive bioink component often blended with alginate or HA to improve printability and function. | GelMA Kit (Advanced BioMatrix) or in-house synthesis. |

| Dynamic Rheometer | Critical for characterizing bioink viscoelasticity, shear-thinning, and gelation kinetics pre-print. | TA Instruments DHR series, Malvern Kinexus. |

| Sterile, Bioprinting-Compatible Nozzles | For extrusion of cell-laden or viscous materials; various gauges (16G-27G) and geometries (coaxial, conical). | Cellink, RegenHU, or Nordson EFD. |

Application Notes on Bioactive Signal Incorporation in 3D-Printed Scaffolds

The transition from inert, structural scaffolds to bioactive, instructive platforms is critical for advancing tissue regeneration. Recent research focuses on integrating growth factors, peptides, and sophisticated release mechanisms directly into the 3D printing process to create spatially and temporally defined microenvironments.

1.1. Current Strategies and Quantitative Outcomes: Key strategies include physical adsorption, covalent immobilization, and encapsulation for controlled release. Recent studies highlight the efficacy of these approaches.

Table 1: Quantitative Outcomes of Bioactive Signal Delivery from 3D-Printed Scaffolds

| Bioactive Signal | Scaffold Material | Incorporation Method | Key Quantitative Outcome | Reference (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 (BMP-2) | Polycaprolactone (PCL) / Gelatin Methacrylate (GelMA) | Heparin-mediated affinity binding | ~85% sustained release over 28 days; 2.5-fold increase in in vitro osteogenic marker (ALP activity) vs. control at day 14. | Wang et al. (2023) |

| Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) | Hyaluronic Acid (HA) / Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) Diacrylate | Photocrosslinkable microsphere encapsulation | Near-zero-order release kinetics for 21 days; 3.1-fold increase in endothelial tubule formation in vitro at day 7. | Silva et al. (2024) |

| RGD Peptide | Poly(L-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone) (PLCL) | Direct peptide mixing in bioink | Enhanced cell adhesion by 220% vs. non-RGD scaffold; significant upregulation of vinculin expression. | Chen & Park (2023) |

| Nerve Growth Factor (NGF) | Silk Fibroin / Graphene Oxide | Coaxial printing for core-shell fibers | Controlled biphasic release (initial burst <30%, then sustained for 35 days); 92% increase in PC12 neurite outgrowth length. | Rodriguez et al. (2024) |

| Stromal Cell-Derived Factor-1α (SDF-1α) | Alginate / Nanoclay | Ionic crosslinking with gradient density | Spatial gradient release maintained for 10 days; directed stem cell migration with a 4-fold chemotactic index. | Kim et al. (2023) |

1.2. The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions Table 2: Essential Materials for Incorporating Bioactive Signals

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Recombinant Human Growth Factors (e.g., BMP-2, VEGF, TGF-β1) | High-purity proteins to induce specific cellular differentiation and tissue formation. Often used with carriers. |

| Synthetic Peptides (e.g., RGD, IKVAV, YIGSR) | Short, stable sequences that mimic extracellular matrix (ECM) to promote specific cell adhesion, migration, or differentiation. |

| Heparin or Heparan Sulfate | A glycosaminoglycan used to bind and stabilize growth factors via affinity interactions, protecting them from denaturation and enabling sustained release. |

| GelMA (Gelatin Methacryloyl) | A widely used bioink material that is inherently cell-adhesive and can be functionalized with peptides or proteins via methacryloyl groups. |

| PLGA (Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) Micro/Nanoparticles | Biodegradable polymer particles for encapsulating sensitive molecules, protecting them during printing and allowing tunable release kinetics. |

| Photoinitiators (e.g., LAP, Irgacure 2959) | Crucial for UV-crosslinkable bioinks (e.g., GelMA, PEGDA), enabling shape fidelity and entrapment of bioactive signals during printing. |

| Coaxial Printhead Nozzles | Allows simultaneous printing of a shell material and a core material containing growth factors, creating protected, core-shell fibers for delayed release. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

2.1. Protocol: Heparin-Mediated BMP-2 Binding in a 3D-Printed PCL/GelMA Composite Scaffold Objective: To fabricate a scaffold with sustained, bioactive BMP-2 release for osteogenesis.

Materials:

- 3D Bioprinter (e.g., BIO X, Cellink)

- PCL filaments (1.75 mm diameter)

- GelMA (10% w/v, 70% degree of methacrylation) in PBS with 0.5% LAP photoinitiator

- Recombinant human BMP-2 (carrier-free)

- Heparin sodium salt

- EDC/NHS crosslinking reagents

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblast cells

Methodology:

- Scaffold Fabrication: Print a porous 3D grid structure (e.g., 10x10x2 mm) using PCL via fused deposition modeling (FDM). Nozzle: 250µm, Temp: 80°C, Layer Height: 150µm.

- Surface Functionalization: Immerse the PCL scaffold in a 1 mg/mL heparin solution containing 5 mM EDC/2 mM NHS in MES buffer (pH 5.5) for 12h at 4°C to covalently conjugate heparin. Wash thoroughly with PBS.

- GelMA Infiltration & Crosslinking: Submerge the heparinized scaffold in the GelMA/LAP solution. Apply a vacuum for 5 min to infiltrate pores. Expose to 405 nm UV light (5 mW/cm²) for 60s.

- BMP-2 Immobilization: Incubate the composite scaffold in a solution of 200 ng/mL BMP-2 in PBS for 24h at 4°C. Heparin will bind BMP-2 via affinity.

- Release Kinetics Test: Place scaffold (n=5) in 1 mL PBS at 37°C. At predetermined time points, collect the entire supernatant for ELISA analysis and replace with fresh PBS.

- Osteogenic Differentiation Assay: Seed MC3T3-E1 cells (50,000/scaffold) on BMP-2-loaded and control scaffolds. Culture in osteogenic medium. Perform Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) activity assay at day 7 and 14 (use pNPP substrate, measure absorbance at 405 nm).

2.2. Protocol: Coaxial Printing of Core-Shell Fibers for NGF Delivery Objective: To create a nerve guidance conduit with controlled, sustained NGF release.

Materials:

- Coaxial printhead nozzle (e.g., 20G inner, 16G outer)

- Crosslinkable Silk Fibroin (SF) bioink (8% w/v)

- Alginate bioink (3% w/v) containing NGF (50 µg/mL)

- Calcium chloride (CaCl₂) crosslinking solution (100 mM)

- PC12 cell line

Methodology:

- Bioink Preparation: Prepare sterile, aqueous SF and alginate/NGF solutions. Centrifuge to degas.

- Coaxial Printing Setup: Load the alginate/NGF solution into the inner syringe and the SF bioink into the outer syringe. Use a pneumatic dispensing system.

- Printing & Instant Crosslinking: Directly print aligned fibers into a bath of 100 mM CaCl₂. The Ca²⁺ ions instantly crosslink the alginate core, entrapping NGF, while the SF shell solidifies via shear-induced beta-sheet formation.

- Release Study: Immerse printed mesh (n=5) in neural culture medium at 37°C. Sample medium at intervals and quantify NGF via ELISA.

- Neurite Outgrowth Assay: Plate PC12 cells on the printed meshes. After 72h, fix, stain for β-III-tubulin, and image. Quantify average neurite length per cell using ImageJ software.

Visualizations

Title: Signaling Pathway from Scaffold to Cell Response

Title: Workflow for Developing Bioactive 3D-Printed Scaffolds

Application Notes

The interface between a cell and a 3D-printed scaffold is a dynamic, bi-directional signaling hub that dictates the success of tissue engineering constructs. This nexus governs initial cell adhesion, subsequent proliferation, and ultimate lineage-specific differentiation—the fundamental triad of regeneration. Within the thesis of 3D printing for tissue regeneration, optimizing this interface is paramount; the scaffold is not a passive bystander but an active instructor.

Key Quantitative Parameters of the Cell-Scaffold Interface: Performance is evaluated through quantifiable metrics. The following tables consolidate critical data from recent studies on common scaffold materials.

Table 1: Adhesion & Proliferation Metrics on Common Printed Polymers (14-Day Culture)

| Polymer / Bioink | Printing Method | Avg. Adhesion Efficiency (%) at 6h | Doubling Time (hours) | Cell Viability (%) Day 7 | Reference Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GelMA (5%) | DLP | 92.5 ± 3.1 | 28.4 ± 2.5 | 94.2 ± 1.8 | 2023 |

| PCL | FDM | 75.2 ± 6.8 | 45.7 ± 4.1 | 88.5 ± 3.2 | 2024 |

| Alginate (2%)/Gelatin | Extrusion | 81.3 ± 4.5 | 32.1 ± 3.3 | 90.1 ± 2.5 | 2023 |

| PLA (with RGD coating) | FDM | 89.7 ± 2.9 | 31.5 ± 3.0 | 91.8 ± 2.1 | 2024 |

| Hyaluronic Acid-MeHA | Extrusion | 86.4 ± 5.2 | 35.2 ± 3.8 | 92.7 ± 2.4 | 2023 |

Table 2: Differentiation Outcomes on Functionalized Constructs (21-Day Culture with Induction)

| Scaffold Base | Functionalization | Cell Type | Key Differentiation Marker | Expression Level (Fold Change vs. Control) | Reference Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GelMA | BMP-2 Peptide | hMSCs | Osteocalcin (OCN) | 8.5 ± 1.2 | 2024 |

| PCL | Nanohydroxyapatite | hMSCs | Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) | 6.2 ± 0.9 | 2023 |

| Silk Fibroin | TGF-β1 | hMSCs | Aggrecan (ACAN) | 9.8 ± 1.5 | 2023 |

| Collagen I | IKVAV Peptide | Neural Progenitors | β-III-tubulin | 7.3 ± 1.1 | 2024 |

| PLA Nanofiber | VEGF | HUVECs | CD31 | 5.9 ± 0.8 | 2024 |

The data underscore that natural polymers like GelMA generally support superior initial adhesion, while functionalization is a critical lever for directing differentiation. Mechanical properties, notably stiffness (elastic modulus), are a master regulator via mechanotransduction. Scaffolds mimicking the modulus of native bone (~10-30 kPa) promote osteogenesis, while softer constructs (~1-10 kPa) favor adipogenesis or neurogenesis.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantitative Assessment of Cell Adhesion on Printed Constructs

Objective: To quantify the percentage of seeded cells that initially attach and spread on a 3D-printed scaffold within a defined period.

Materials:

- Sterile, fabricated scaffolds (e.g., 5 mm diameter x 2 mm height discs).

- Cell suspension of interest (e.g., human Mesenchymal Stem Cells, hMSCs).

- Complete growth medium.

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), sterile.

- Trypsin/EDTA solution (0.25%).

- Hemocytometer or automated cell counter.

- 24-well low-attachment plate.

- Orbital shaker placed in a 37°C incubator.

Method:

- Scaffold Pre-conditioning: Sterilize scaffolds (UV irradiation or ethanol wash). Equilibrate scaffolds in complete growth medium for ≥1 hour at 37°C.

- Cell Seeding: Prepare a single-cell suspension at a known density (e.g., 5 x 10⁴ cells/scaffold in 20-30 µL). Pipette the suspension directly onto the center of each scaffold placed in a low-attachment well. Allow cells to attach for 90 minutes in the incubator.

- Gentle Washing: After 90 minutes, carefully add 1 mL of pre-warmed medium to each well without disturbing the scaffold. After 30 minutes, gently aspirate the medium (non-adherent cells) and save.

- Collection of Non-Adherent Cells: Transfer the scaffold to a new well with fresh medium. Rinse the original well with trypsin to collect any remaining loose cells and pool with the aspirated medium. Centrifuge the pooled solution and resuspend the pellet for counting.

- Calculation: Count the cells in the non-adherent fraction. Adhesion Efficiency (%) = [(Total Cells Seeded - Non-adherent Cells) / Total Cells Seeded] x 100%. Perform in triplicate minimum.

Protocol 2: Monitoring 3D Cell Proliferation via Metabolic Activity (AlamarBlue Assay)

Objective: To track cell proliferation within a 3D scaffold over time using a non-destructive, metabolic indicator.

Materials:

- Cell-laden scaffolds in culture.

- AlamarBlue (resazurin) cell viability reagent.

- Phenol red-free complete medium.

- 96-well plate (black, clear bottom).

- Microplate fluorometer/spectrophotometer.

Method:

- Preparation: At each time point (e.g., Days 1, 3, 7, 14), prepare a working solution of 10% (v/v) AlamarBlue reagent in phenol red-free medium.

- Incubation: Aspirate the standard culture medium from scaffolds. Add the 10% AlamarBlue working solution to completely submerge each scaffold. Include scaffold-only controls (no cells) in AlamarBlue for background subtraction.

- Incubation and Measurement: Incubate plates for 3 hours at 37°C, protected from light. After incubation, pipette 100 µL of the reacted solution from each well into a 96-well plate.

- Readout: Measure fluorescence (Excitation: 560 nm, Emission: 590 nm) or absorbance (570 nm and 600 nm). Subtract the average background signal from control wells.

- Analysis: Plot the relative fluorescence/absorbance units over time. A significant increase indicates cell proliferation. This assay allows longitudinal tracking of the same set of constructs.

Protocol 3: Evaluating Osteogenic Differentiation on Functionalized Constructs

Objective: To quantify early and late-stage osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs cultured on printed, bioactive scaffolds.

Materials:

- hMSC-seeded scaffolds (from Protocol 1).

- Osteogenic induction medium (OM: base medium + 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 µg/mL ascorbic acid, 100 nM dexamethasone).

- Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Staining Kit or quantitative substrate (e.g., pNPP).

- Osteocalcin (OCN) ELISA Kit.

- Cell lysis buffer (e.g., RIPA with protease inhibitors).

- BCA Protein Assay Kit.

Method (Quantitative):

- Culture: Maintain hMSC-seeded scaffolds in OM, changing medium every 3 days.

- Early Marker (ALP Activity) - Day 7/10:

- Lyse cells in scaffolds using ice-cold lysis buffer (sonicate on ice if needed).

- Centrifuge lysates, collect supernatant.

- Quantify total protein concentration via BCA assay.

- Perform ALP activity assay using pNPP substrate per manufacturer's protocol. Normalize ALP activity to total protein content (nmol/min/µg protein).

- Late Marker (Osteocalcin Secretion) - Day 21:

- Collect conditioned medium from scaffolds after 24 hours of culture.

- Centrifuge to remove debris.

- Perform Osteocalcin ELISA on the conditioned medium supernatant per kit instructions. Normalize OCN concentration to total cellular DNA or protein from the lysed scaffold.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Cell-Scaffold Research |

|---|---|

| RGD Peptide Solution | A synthetic integrin-binding motif (Arg-Gly-Asp) used to coat or conjugate to synthetic polymers (e.g., PCL, PLA) to enhance specific cell adhesion. |

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | A photocrosslinkable hydrogel derived from gelatin; provides natural cell-adhesive motifs (e.g., RGD) and tunable mechanical properties for extrusion or DLP printing. |

| Recombinant Human Growth Factors (BMP-2, TGF-β1, VEGF) | Soluble signaling proteins added to culture media or tethered to scaffolds to direct stem cell differentiation down osteogenic, chondrogenic, or angiogenic lineages. |

| AlamarBlue (Resazurin) | A cell-permeable, non-toxic blue dye reduced to fluorescent pink resorufin by metabolically active cells, enabling longitudinal tracking of proliferation in 3D constructs. |

| pNPP (p-Nitrophenyl Phosphate) | A colorimetric substrate for Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP); enzymatic cleavage yields a yellow product measurable at 405 nm, quantifying early osteogenic differentiation. |

| Triton X-100 / RIPA Lysis Buffer | Detergent-based solutions used to lyse cells within scaffolds, releasing intracellular proteins and enzymes for downstream quantitative assays (e.g., ALP, ELISA). |

| Hyaluronic Acid Derivatives (e.g., MeHA) | Printable, bioactive glycosaminoglycans that can be modified with methacrylate groups for crosslinking; influential in chondrogenesis and soft tissue engineering. |

| Nanohydroxyapatite (nHA) Particles | A bioactive ceramic mimicking bone mineral; often incorporated into polymer bioinks (e.g., with PCL or GelMA) to enhance osteoconductivity and scaffold stiffness. |

Diagrams

Key Signaling Pathways at the Cell-Scaffold Interface

Experimental Workflow for Interface Analysis

From Blueprint to Biostructure: Advanced 3D Printing Techniques and Targeted Applications

Within the context of 3D printing for tissue regeneration, selecting an appropriate bioprinting modality is critical for achieving biomimetic scaffolds with the requisite structural, mechanical, and biological properties. This analysis compares four core technologies: extrusion, stereolithography (SLA), digital light processing (DLP), and electrospinning-based bioprinting. Each offers distinct trade-offs in resolution, speed, biocompatibility, and suitability for different tissue engineering applications.

Extrusion Bioprinting

- Application Note: Ideal for depositing high-cell-density bioinks and creating large, mechanically robust constructs. Best suited for musculoskeletal tissues (bone, cartilage) and soft tissues requiring macro-architectural control. Limitations include lower resolution and potential shear stress on cells.

- Key Parameters: Nozzle diameter (80-500 µm), pressure (15-150 kPa), print speed (1-50 mm/s), temperature (ambient or heated/cooled stage).

SLA/DLP Bioprinting

- Application Note: Offers high resolution (µm-scale) for creating intricate, patient-specific scaffolds. DLP projects entire layers for faster printing. Ideal for creating microfluidic channels, dental implants, and highly detailed bone or vascular templates. Requires photosensitive, often non-cytocompatible resins, typically used for acellular scaffolds or combined with cell-seeding post-print.

- Key Parameters: Light wavelength (365-405 nm), exposure time (1-30 s/layer for SLA, 1-10 s/layer for DLP), layer thickness (10-100 µm).

Electrospinning (Bioprinting Variants)

- Application Note: Produces non-woven nanofibrous mats mimicking the extracellular matrix (ECM). Melt or solution electrospinning creates scaffolds with high surface area-to-volume ratios, excellent for cell attachment and guidance. Emerging "Near-Field" and handheld electrospinning devices allow for more controlled, direct writing into 3D shapes for wound dressings, neural, and skin tissue engineering.

- Key Parameters: Voltage (10-30 kV), flow rate (0.5-5 mL/h), collector distance (5-30 cm), needle gauge (18-25 G).

Comparative Quantitative Data

Table 1: Comparative Technical Specifications of Bioprinting Modalities

| Feature | Extrusion-Based | SLA-Based | DLP-Based | Electrospinning-Based (Near-Field) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Resolution | 50 - 500 µm | 10 - 100 µm | 10 - 100 µm | 500 nm - 20 µm (fiber diameter) |

| Print Speed | Slow-Moderate (1-50 mm/s) | Slow (sequential curing) | Fast (full layer cure) | Moderate (collector movement) |

| Viscosity Range | High (30 - 6x10^7 mPa·s) | Low-Medium (photo-responsive) | Low-Medium (photo-responsive) | Low (for solution) |

| Cell Viability Post-Print | 40-95% (shear-sensitive) | N/A (often acellular) | N/A (often acellular) | Variable (high voltage risk) |

| Common Materials | Alginate, GelMA, Collagen, Pluronic, PCL | PEGDA, GelMA, Acrylate Resins | PEGDA, GelMA, Acrylate Resins | PCL, PLA, Collagen, Gelatin |

| Key Strength | High cell density, structural integrity | High resolution, surface finish | Speed at high resolution | ECM-mimetic nanofibrous structure |

| Primary Limitation | Low resolution, shear stress | Limited biomaterials, cytotoxicity | Limited biomaterials, cytotoxicity | Difficulty achieving 3D bulk structures |

| Typical Scaffold Porosity | 20-60% (controlled by design) | 20-80% (controlled by design) | 20-80% (controlled by design) | 60-90% (stochastic) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Extrusion Bioprinting of Cell-Laden GelMA Construct for Cartilage Research

- Bioink Preparation: Dissolve 10% w/v GelMA (with 0.25% w/v LAP photoinitiator) in PBS at 37°C. Mix with human chondrocytes (passage 3-5) to a final density of 5x10^6 cells/mL. Keep at 37°C until printing.

- Printer Setup: Use a temperature-controlled (18-22°C) pneumatic extrusion printhead with a 22G (410 µm) conical nozzle. Set stage temperature to 4°C.

- Printing Parameters: Optimize pressure (25-35 kPa) and speed (8-12 mm/s) for consistent filament deposition. Print layer-by-layer in a crosshatch pattern (0/90°).

- Post-Processing: Crosslink each layer with 405 nm light (5-10 mW/cm², 30-60 s exposure) immediately after deposition. After final print, immerse in cell culture medium and cure fully for 120 s.

- Culture: Transfer to 24-well plate, add chondrogenic medium (high glucose DMEM, TGF-β3, ascorbic acid), and culture for up to 28 days, assessing GAG and collagen type II deposition.

Protocol 2: DLP Printing of a Patient-Specific Acellular PCL-based Bone Scaffold

- Resin Preparation: Synthesize a biodegradable resin: dissolve 70% w/w PCL-diacrylate oligomer and 30% w/w PEGDA (Mn 700) in DCM. Add 2% w/w TPO as photoinitiator. Evaporate DCM completely under vacuum. Heat to 70°C to form a homogeneous melt.

- Digital Model Preparation: Segment a patient's CT scan of a mandibular defect using 3D Slicer. Generate a porous scaffold (500 µm pore size) using Autodesk Netfabb. Slice model into 50 µm layers.

- Printing: Preheat DLP vat to 70°C. Load resin. Set exposure time to 3 seconds per layer. Print.

- Post-Processing: Wash printed scaffold in warm ethanol to remove uncured resin. Post-cure under UV light (365 nm, 30 min). Characterize compressive modulus via uniaxial testing.

Protocol 3: Near-Field Electrospinning of Aligned PCL/Gelatin Fibers for Neural Guidance Conduits

- Polymer Solution: Prepare a 12% w/v PCL and 4% w/v gelatin solution in 1,1,1,3,3,3-Hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP). Stir for 12 hours at room temperature.

- Setup: Use a programmable syringe pump and a 23G blunt needle. Connect to a high-voltage supply. Use a grounded, cylindrical mandrel (3 mm diameter) rotating at 3000 RPM as a collector. Set working distance to 3 mm.

- Printing Parameters: Set flow rate to 0.8 mL/h and voltage to 2.5 kV. Program the collector to translate laterally at 20 mm/s to create a aligned fiber mesh along the conduit's long axis.

- Post-Processing: Crosslink the gelatin component using glutaraldehyde vapor (25% solution, 2 hours). Evacuate under vacuum for 24h to remove residual solvent and crosslinker.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Workflow for Bioprinted Scaffold Evaluation in Tissue Regeneration

Diagram 2: Material Crosslinking Pathways in Bioprinting

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Bioprinting Research

| Item | Function & Rationale | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Photocrosslinkable hydrogel combining biocompatibility of gelatin with tunable mechanics. Gold standard for cell-laden constructs. | Advanced BioMatrix, CELLINK |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) Diacrylate (PEGDA) | Synthetic, photopolymerizable resin for creating high-resolution, inert hydrogel scaffolds. Often functionalized with RGD peptides. | Sigma-Aldrich, Laysan Bio |

| Lithium Phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | Efficient, water-soluble, cytocompatible photoinitiator for UV/blue light crosslinking (e.g., of GelMA). | Sigma-Aldrich, TCI Chemicals |

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | Biodegradable, thermoplastic polyester for extrusion or electrospinning. Provides long-term mechanical support. | Sigma-Aldrich, Corbion |

| Alginate (High G-Content) | Rapidly ionically crosslinked (with Ca2+) polysaccharide. Used for extrusion bioprinting to provide immediate shape fidelity. | NovaMatrix, FMC Biopolymer |

| Transforming Growth Factor-beta 3 (TGF-β3) | Key cytokine for inducing chondrogenic differentiation in mesenchymal stem cells within 3D printed scaffolds. | PeproTech, R&D Systems |

| Live/Dead Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit | Standard assay (Calcein AM/EthD-1) to quantitatively assess cell viability post-printing and during culture. | Thermo Fisher Scientific |

| Dimethyloxalylglycine (DMOG) | Hypoxia-mimetic agent used to upregulate VEGF and enhance vascularization in printed constructs in vitro. | Cayman Chemical |

Application Notes

In 3D bioprinting for tissue regeneration, the integration of perfusable vascular networks is the critical bottleneck for engineering clinically relevant, thick tissues. This document details current strategies and quantitative benchmarks for creating microchannels and functional vasculature within 3D scaffolds.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Primary Vascularization Strategies

| Strategy | Core Methodology | Typical Channel Resolution | Key Performance Metrics (Reported Ranges) | Primary Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sacrificial Templating | Printing of fugitive ink (e.g., Pluronic F127, gelatin) co-printed with bioink, later liquefied and evacuated. | 50 - 500 µm | Patency: Days to weeks; Perfusion pressure: 5-15 kPa; Endothelial lining efficiency: 60-80%. | High design freedom, creates complex interconnected networks. | Manual removal challenging in deep layers, potential residue. |

| Direct Printing of Hollow Filaments | Extrusion of coaxial cell-laden bioink with a crosslinkable shell and removable core. | 150 - 1000 µm | Lumen diameter consistency: ±10-20%; Burst pressure: 20-50 kPa; Perfusion flow rate: 1-10 mL/min. | Immediate lumen patency, integrated in a single step. | Limited geometric complexity, lower resolution. |

| Void-Forming Bioinks | Use of microparticle or granular hydrogels that self-assemble or sinter, leaving interstitial spaces. | 20 - 200 µm | Void interconnectivity: 70-90%; Angiogenic sprouting distance: 500-1000 µm in 7 days. | Encourages rapid cellular infiltration and neovascularization. | Limited control over network architecture, smaller lumen size. |

| Photopatterning | Spatial light modulation (e.g., DLP) to crosslink hydrogels in 3D, leaving uncrosslinked channels. | 10 - 100 µm | XY resolution: 10-50 µm; Channel fidelity: High; Endothelialization: Uniform monolayer. | Excellent resolution and architectural control. | Requires photoresponsive (often synthetic) bioinks, limited scaffold depth. |

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Functional Perfusable Network Assessment

| Metric | Measurement Technique | Target Values for In Vitro Networks | Significance for Tissue Regeneration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Patency Duration | Time-lapse microscopy of fluorescent dextran perfusion. | >14-21 days | Indicates structural stability and resistance to collapse. |

| Perfusion Flow Rate | Controlled pressure system with flow sensor (e.g., syringe pump). | 0.5 - 5 mL/min (for ~1mm channels) | Dictates nutrient/waste exchange capacity for encapsulated parenchymal cells. |

| Effective Diffusion Radius | Measurement of fluorescent tracer penetration from channel into matrix. | Sustained cell viability within 150-200 µm of channel wall. | Defines the maximum thickness of viable tissue per vascular channel. |

| Endothelial Barrier Function | Quantification of FITC-dextran (70 kDa) leakage. | <15% leakage over 30 min. | Demonstrates mature, functional endothelial monolayer formation. |

| Anastomosis with Host Vasculature | In vivo implantation, microscopy (e.g., intravital) of host vessel connection. | Functional blood flow into scaffold within 5-7 days post-implant. | Critical for graft survival and integration upon transplantation. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Sacrificial Templating with Pluronic F127 for a Perfusable Bifurcating Network

Objective: To fabricate a collagen-I scaffold with an embedded, endothelialized, perfusable bifurcating channel network.

I. Materials & Pre-Printing Preparation

- Sacrificial Ink: 40% (w/v) Pluronic F127 in PBS (4°C).

- Bioink: 8 mg/mL Rat Tail Collagen I, neutralized with 1M NaOH and 10X PBS on ice. Optionally supplement with 1x10^6 cells/mL fibroblasts.

- Crosslinking Solution: 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde in PBS (for temporary stabilization).

- Cell Seeding Suspension: Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs), 5x10^6 cells/mL in EGM-2 medium.

- Equipment: Pneumatic or piston-driven bioprinter with dual printheads, refrigerated print stage (4°C), 37°C humidified incubation chamber.

II. Printing & Fabrication

- Load Pluronic F127 ink into a printing syringe and maintain at 4°C. Load neutralized collagen bioink into a separate syringe, kept on ice.

- Design a 3D model with two primary connected networks: the sacrificial (Pluronic) network and the surrounding scaffold (collagen).

- Co-printing: On a stage at 4°C, first print the Pluronic F127 network (e.g., 22G nozzle, 25 kPa). Immediately (~30 sec delay) print the collagen bioink around and over the sacrificial template (e.g., 20G nozzle, 15 kPa). Maintain stage at 4°C throughout.

- Temporary Crosslinking: Immediately post-print, gently immerse the construct in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 60 seconds. Rinse 3x with cold PBS.

- Sacrificial Removal: Transfer construct to a 37°C incubator for 15 minutes to liquefy Pluronic. Connect one inlet of the network to a peristaltic pump and perfuse with cold PBS (0.5 mL/min for 10 min) to evacuate the fugitive ink, leaving open channels.

III. Endothelialization & Culture

- Immediately after evacuation, perfuse the channel network with the HUVEC suspension at a very low flow rate (0.1 mL/min) for 20 minutes, allowing cell adhesion.

- Reverse flow direction and repeat to seed the opposite side of the channels.

- Transfer the construct to a bioreactor or static culture with EGM-2 medium, initiating low continuous flow (0.2 mL/min) after 24 hours. Increase flow gradually to 0.5 mL/min over 3 days to promote endothelial alignment.

Protocol 2: Assessment of Network Perfusion and Barrier Function

Objective: To quantify the patency and endothelial barrier integrity of an engineered vascular network.

I. Materials

- Perfusion System: Programmable syringe pump, pressure sensor, tubing set.

- Tracers: FITC-dextran (4 kDa, for perfusion visualization) and Texas Red-dextran (70 kDa, for barrier integrity).

- Imaging: Confocal or fluorescence microscope with time-lapse capability.

II. Methodology

- Setup: Connect the inlet of the engineered vascular construct to the syringe pump via tubing. Place the outlet in a collection tube. Mount the construct under a microscope.

- Patency & Flow Rate Test: Perfuse with FITC-dextran (4 kDa, 1 mg/mL in PBS) at a fixed pressure (e.g., 5 kPa). Record the flow rate achieved. Use time-lapse imaging to visualize uniform filling of the network.

- Barrier Function Assay: Switch perfusion to Texas Red-dextran (70 kDa, 1 mg/mL) at physiological shear stress (~1 dyne/cm²). Collect effluent from the outlet every 5 minutes for 30 minutes.

- Quantification:

- Image the diffusion of Texas Red into the surrounding hydrogel at set time points.

- Measure fluorescence intensity of Texas Red in the collected effluent (Iout) and the original perfusate (Iin).

- Calculate Percentage Leakage = [(Iout - background) / (Iin - background)] * 100.

- A mature barrier should show <15% leakage over 30 minutes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item/Reagent | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Pluronic F127 | Thermo-reversible sacrificial polymer. Solid at room temp/printable, liquefies at 4°C for easy removal, forming microchannels. |

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Photocrosslinkable bioink derived from gelatin. Excellent cell adhesion and tunable mechanical properties for creating vascularized constructs. |

| Fibrinogen-Thrombin | Enzymatically crosslinked hydrogel. Mimics the provisional clotting matrix; strongly pro-angiogenic, promotes endothelial cell sprouting and morphogenesis. |

| VEGF (165 isoform) | Key pro-angiogenic growth factor. Supplemented in culture medium to drive endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and lumen formation. |

| Angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1) | Stabilizing growth factor. Promotes vessel maturation and stability by mediating interactions between endothelial and perivascular cells. |

| RGDS Peptide | Synthetic integrin-binding peptide. Can be conjugated to hydrogels (e.g., PEG) to provide essential cell adhesion motifs for endothelial attachment. |

| Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP)-Sensitive Peptide Crosslinker | Allows cell-mediated remodeling. Critical for endothelial sprouting and invasion into the surrounding hydrogel matrix. |

| Fluorescent Microspheres (1-10 µm) | Used in perfusion studies to visualize flow paths, quantify flow velocity, and identify areas of stagnation or blockage within networks. |

Visualizations

Title: Sacrificial Templating Workflow

Title: Key Signaling Pathways in Vascularization

Title: Validation Pipeline for Engineered Vasculature

This application note details the use of 3D-printed ceramic-polymer composite scaffolds for osteochondral regeneration, a critical focus within the broader thesis on advanced scaffolding for tissue engineering. The synergy between bioceramics (e.g., hydroxyapatite, beta-tricalcium phosphate) and biodegradable polymers (e.g., PCL, PLGA, gelatin) provides scaffolds with optimal mechanical integrity, bioactivity, and tailored degradation profiles, addressing the challenge of regenerating both bone and cartilage tissue interfaces.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Common Ceramic-Polymer Composites for Osteochondral Scaffolds

| Composite Material (Typical Ratio) | Compressive Modulus (MPa) | Degradation Time (Months) | In Vitro Cell Viability (% vs Control) | Key Biological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCL-HA (70:30) | 150 - 220 | 24+ | 95-105% | Enhanced osteogenic differentiation, bone formation |

| PLGA-Beta-TCP (60:40) | 80 - 120 | 6-12 | 90-98% | Good bone ingrowth, resorbable |

| Gelatin-HA (80:20) | 20 - 50 | 1-3 | 98-110% | Excellent chondrocyte proliferation, cartilage ECM deposition |

| PCL-Gelatin-HA (Bilayer) | Bone Layer: 180-250Cartilage Layer: 10-30 | Tailored | >95% (both layers) | Simultaneous regeneration of bone and cartilage zones |

| Silk Fibroin-HA (50:50) | 50 - 100 | 12-18 | 85-95% | Good biocompatibility, sustained mineral release |

Table 2: Critical 3D Printing Parameters for Composite Scaffolds

| Printing Technique | Nozzle Diameter (µm) | Pressure/Temp | Layer Height (µm) | Post-Processing | Pore Size (µm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extrusion-based | 200 - 400 | 65-120°C, 300-600 kPa | 150 - 250 | Crosslinking (e.g., EDC/NHS), Sintering (ceramic) | 300-500 |

| Digital Light Processing (DLP) | N/A | UV Light | 25 - 100 | UV Post-cure, Thermal Debinding/Sintering | 200-400 |

| Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) | N/A | Laser Energy | 50 - 150 | Removal of unsintered powder | 400-700 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Fabrication of PCL-HA Composite Scaffolds via Melt-Extrusion 3D Printing

Objective: To fabricate a porous, osteoconductive scaffold for bone regeneration. Materials: Medical-grade PCL pellets, nano-hydroxyapatite (nHA) powder, anhydrous chloroform. Equipment: Dual-extrusion 3D bioprinter, heated syringe barrel, magnetic stirrer, vacuum desiccator. Procedure:

- Ink Preparation: Dissolve PCL pellets in chloroform (20% w/v) at 50°C under constant stirring. Gradually incorporate nHA powder to achieve a 30% w/w composite. Stir for 12h until homogenous. Evaporate solvent under vacuum for 24h to form a solid composite filament.

- Printer Setup: Load composite filament. Use a 250µm nozzle. Set build platform temperature to 25°C.

- Printing Parameters: Set extrusion temperature to 100°C, pressure to 450 kPa. Use a 0/90° laydown pattern. Define layer height as 200µm, printing speed as 8 mm/s.

- Printing: Execute print job for a 10x10x3 mm scaffold. Store printed scaffolds in a desiccator.

- Post-processing: Immerse scaffolds in 1M NaOH for 2h to enhance surface hydrophilicity. Rinse 3x with DI water and sterilize with 70% ethanol followed by UV exposure (1h per side).

Protocol 3.2:In VitroOsteogenic Differentiation Assay on Composite Scaffolds

Objective: To evaluate the osteoinductive potential of the composite scaffold using human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs). Materials: hMSCs (P3-P5), Osteogenic media (DMEM, 10% FBS, 10mM β-glycerophosphate, 50µM ascorbate-2-phosphate, 100nM dexamethasone), Alizarin Red S stain, Quantification kit. Procedure:

- Seeding: Sterilize scaffolds (Protocol 3.1) and pre-wet with media. Seed hMSCs at a density of 50,000 cells/scaffold in a low-attachment plate. Allow 2h for attachment before adding osteogenic media.

- Culture: Maintain cultures for 21 days, changing media every 3 days.

- Analysis (Day 21):

- Alizarin Red Staining: Fix scaffolds in 4% PFA for 30 min. Wash and incubate with 2% Alizarin Red S (pH 4.2) for 20 min. Wash extensively with DI water and image.

- Quantification: Elute stain with 10% cetylpyridinium chloride for 1h. Measure absorbance at 562 nm. Compare to a standard curve of known calcium content.

- Gene Expression (Optional): Lyse cells at day 7, 14, 21 for RT-qPCR analysis of RUNX2, OSX, OPN, and OCN.

Signaling Pathways in Osteochondral Differentiation

Diagram Title: BMP/TGF-β Pathways in Osteochondral Fate

Experimental Workflow for Composite Scaffold Evaluation

Diagram Title: Integrated Scaffold R&D Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Ceramic-Polymer Composite Research

| Item Name & Typical Supplier | Function in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Medical-grade PCL (Sigma-Aldrich, Purac) | Biodegradable polymer backbone; provides structural integrity and printability. | Molecular weight (Mn 45k-80k) controls degradation rate and melt viscosity. |

| Nano-Hydroxyapatite (nHA) (Berkeley Advanced Biomaterials, Fluidinova) | Bioactive ceramic; mimics bone mineral, enhances osteoconductivity and compressive strength. | Particle size (<200 nm) and crystallinity affect bioactivity and composite homogeneity. |

| Beta-Tricalcium Phosphate (β-TCP) (Sigma-Aldrich) | Resorbable ceramic; promotes osteoblast differentiation and bone remodeling. | Ca/P ratio and porosity influence dissolution kinetics and ion release profile. |

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) (Advanced BioMatrix) | Photocrosslinkable polymer for cartilage layer; supports chondrocyte adhesion and proliferation. | Degree of functionalization determines mechanical strength and crosslinking density. |

| hMSCs (Lonza, ATCC) | Primary cell model for evaluating osteogenic/chondrogenic differentiation on scaffolds. | Use low passage numbers (P3-P5) to maintain multipotency. Verify differentiation potential. |

| Osteogenic & Chondrogenic Differentiation Media Kits (Thermo Fisher, STEMCELL Tech) | Standardized media formulations for consistent in vitro differentiation assays. | Aliquot and store growth factors (e.g., BMP-2, TGF-β3) at -80°C to prevent degradation. |

| AlamarBlue & PicoGreen Assays (Invitrogen) | Quantify metabolic activity and DNA content for cell proliferation on 3D scaffolds. | Ensure thorough washing to remove residual dye trapped in porous scaffolds. |

| EDC/NHS Crosslinking Kit (Thermo Fisher) | Chemically crosslink composite components (e.g., gelatin-HA) to improve mechanical stability. | Optimize molar ratios to maximize crosslinking efficiency while minimizing cytotoxicity. |

Within the broader thesis on 3D-printed scaffolds for tissue regeneration, the biofabrication of complex soft tissues represents a frontier of translational medicine. This application note details current advances, quantitative benchmarks, and standardized protocols for three critical areas: skin, cardiac patches, and neural conduits.

Skin: Bilayer and Full-Thickness Constructs

Engineered skin substitutes aim to replicate the epidermal and dermal layers. Recent focus is on integrating vascular networks and appendages (hair follicles, sweat glands).

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for 3D-Bioprinted Skin Constructs

| Parameter | Bilayer Construct | Vascularized Full-Thickness | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epidermal Stratification | 4-6 layers | 8-10 layers | Histology (H&E) |

| Barrier Function (TEWL*) | 15-25 g/m²/h | 8-15 g/m²/h | Tewameter |

| Tensile Strength | 1.2 - 2.5 MPa | 3.0 - 5.0 MPa | Uniaxial tensile test |

| Time to Vascularization (in vivo) | >21 days | 7-14 days | Laser Doppler imaging |

| Keratinocyte Viability | >85% | >90% | Live/Dead assay |

*TEWL: Transepidermal Water Loss

Protocol 1.1: Bioprinting a Vascularized Dermal-Epidermal Skin Model

Objective: To fabricate a full-thickness skin construct with a perfusable microvascular network. Materials:

- Bioink A (Dermal): 15 mg/mL Type I collagen, 2% (w/v) alginate, human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs, 5x10^6 cells/mL).

- Bioink B (Vascular): 8 mg/mL fibrinogen, 3 mg/mL hyaluronic acid, human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs, 1x10^7 cells/mL), human dermal microvascular endothelial cells (HDMECs, 5x10^6 cells/mL).

- Bioink C (Epidermal): 3% (w/v) gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA), human epidermal keratinocytes (HEKs, 1x10^7 cells/mL).

- Crosslinking: 2% (w/v) CaCl₂ solution (for alginate), 0.1 U/mL thrombin solution (for fibrin), UV light (365 nm, 5 mW/cm² for 60s for GelMA). Method:

- Printing Setup: Use a coaxial extrusion printhead on a stereolithography-assisted 3D bioprinter. Maintain stage temperature at 16°C.

- Print Vascular Core: Co-axially extrude Bioink B (core) with a Pluronic F127 support bath (sacrificial). Crosslink immediately with thrombin solution mist.

- Print Dermal Layer: Using a separate printhead, encapsulate the vascular network with Bioink A in a lattice structure. Crosslink with CaCl₂ mist.

- Culture & Maturation: Culture in endothelial growth medium (EGM-2) for 7 days to form a confluent endothelium. Perfuse using a bioreactor at 0.5 mL/min.

- Seed Epidermal Layer: Seed HEKs (Bioink C) atop the dermal layer after 7 days. Crosslink GelMA with UV. Air-lift the construct at the air-liquid interface for 14 days in keratinocyte differentiation medium.

Cardiac Patches: Electrically Conductive and Contractile Constructs

Cardiac patches require synchronous contraction, robust electromechanical coupling, and integration with host tissue.

Table 2: Benchmarking 3D-Bioprinted Cardiac Patches

| Property | Alginate/GelMA-based | GelMA/CNT*-based | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiomyocyte Viability (Day 7) | 78 ± 5% | 92 ± 3% | Calcein AM staining |

| Conductivity | 0.15 ± 0.03 S/m | 0.68 ± 0.08 S/m | 4-point probe |

| Synchronous Beating Rate | 0.5 - 1 Hz | 1 - 1.5 Hz | Video analysis/MEA |

| Maximum Contractile Stress | 3-5 mN/mm² | 8-12 mN/mm² | Force transducer |

| Expression of Cx43 (Gap Junctions) | Moderate | High | qPCR/Immunostaining |

CNT: Carbon Nanotubes; *MEA: Microelectrode Array

Protocol 2.1: Fabrication of a Conductive Cardiac Patch

Objective: To create a contractile cardiac patch with enhanced electrical conductivity. Materials:

- Bioink: 10% (w/v) GelMA, 0.5 mg/mL single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs), human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs, 1x10^7 cells/mL).

- Control Bioink: 10% (w/v) GelMA only with same cell density. Method:

- Bioink Preparation: Disperse SWCNTs in photoinitiator (0.5% w/v LAP) solution via probe sonication on ice. Mix with GelMA precursor solution. Incubate with hiPSC-CMs gently.

- Bioprinting: Use a digital light processing (DLP) printer. Project a 2D lattice pattern (500 µm pore size) layer-by-layer. Expose each 100 µm layer to 405 nm light (10 mW/cm²) for 20s.

- Post-Printing: Culture in cardiac maintenance medium. Apply cyclic mechanical stimulation (5% strain, 1 Hz) after 3 days using a bioreactor.

- Functional Assessment: On day 10, measure contraction via video analysis, map electrical propagation using microelectrode arrays, and assess calcium transients via Fluo-4 AM dye.

Neural Conduits: Aligned Tubes for Axonal Guidance

Neural conduits provide topographical and biochemical cues to bridge peripheral nerve gaps, directing Schwann cell migration and axonal regrowth.

Table 3: Efficacy of Printed Neural Conduits in Preclinical Models

| Conduit Type | Material Composition | Max Gap Bridged (in vivo) | Axonal Regrowth Speed | Functional Recovery (SFI)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hollow Tube | PCL | 10 mm | 0.8 mm/day | -50 ± 5 |

| Aligned Fiber Lumen | PCL/Gelatin | 15 mm | 1.2 mm/day | -35 ± 7 |

| Multichannel + GDNF | GelMA/HA + growth factor | 20 mm | 1.8 mm/day | -25 ± 4 |

*SFI: Sciatic Function Index (0 = normal, -100 = complete impairment).

Protocol 3.1: Printing a Dual-Cue (Topographical/Biochemical) Neural Conduit

Objective: To fabricate a multichannel nerve guide incorporating aligned topographical cues and sustained neurotrophic factor release. Materials:

- Sheath Bioink: 15% (w/v) Polycaprolactone (PCL) for melt electrowriting (MEW).

- Lumen Bioink: 8% (w/v) GelMA, 1% (w/v) hyaluronic acid methacrylate (HAMA), loaded with glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) in poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) microparticles.

- Cells: Rat Schwann cells (1x10^6 cells/mL). Method:

- Sheath Fabrication: Use MEW to print a microporous, tubular PCL sheath (ID 1.5 mm, length 20 mm) with aligned circumferential fibers (10 µm diameter, 50 µm spacing).

- Lumen Printing: Inside the sheath, use a coaxial extrusion printhead to deposit three parallel strands of the GelMA/HAMA bioink containing GDNF-PLGA microparticles and Schwann cells. Photocrosslink with UV light (365 nm, 10 mW/cm², 30s).

- In Vitro Assessment: Culture in Schwann cell medium. Assess GDNF release via ELISA weekly. At 14 days, seed rat dorsal root ganglion neurons at one end to quantify neurite alignment and length.

- In Vivo Implantation: In a rat sciatic nerve 15mm gap model, suture the conduit. Monitor monthly via electrophysiology and histomorphometry at 12 weeks.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Supplier Examples | Primary Function in Soft Tissue Bioprinting |

|---|---|---|

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Cellink, Advanced BioMatrix | Photocrosslinkable hydrogel providing cell-adhesive RGD motifs for encapsulation. |

| Type I Collagen (Bovine/ Rat Tail) | Corning, Thermo Fisher | Major ECM protein for dermal matrix bioinks, promoting fibroblast attachment and migration. |

| LAP Photoinitiator | Sigma-Aldrich, TCI Chemicals | (Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate) Enables rapid, cytocompatible UV crosslinking of hydrogels. |

| hiPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes | Fujifilm Cellular Dynamics, Takara Bio | Patient-specific cell source for cardiac patches with inherent contractile function. |

| Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNTs) | Sigma-Aldrich, Cheap Tubes | Nanomaterial additive to enhance electrical conductivity of bioinks for cardiac and neural tissues. |

| PLGA Microparticles | PolySciTech, Sigma-Aldrich | Provide sustained, localized release of growth factors (e.g., GDNF, VEGF) from printed scaffolds. |

| EGM-2 Endothelial Cell Medium | Lonza | Specialized medium for expansion and culture of endothelial cells in vascular networks. |

| Pluronic F127 | Sigma-Aldrich | Thermoresponsive sacrificial support bath material for printing hollow, complex structures. |

Diagrams

Title: Cardiac Patch Fabrication and Assessment Workflow

Title: GDNF Signaling in Neural Conduit Efficacy

Application Notes

The evolution from 3D to 4D printing in tissue engineering introduces a temporal dimension, where printed scaffolds dynamically morph or change functionality post-fabrication in response to specific stimuli. This paradigm is pivotal for creating biomimetic environments that guide complex tissue regeneration processes, addressing the static limitations of traditional 3D-printed scaffolds.

1. Key Stimuli-Responsive Mechanisms:

- Thermoresponsive: Utilizing polymers like poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (pNIPAM) that swell/contract at a lower critical solution temperature (LCST ~32°C), enabling cell detachment or pore size modulation.

- pH-Responsive: Employing polymers with ionizable groups (e.g., chitosan, poly(acrylic acid)) that swell in response to pH changes in inflammatory or tumor microenvironments.

- Photo-responsive: Integrating compounds like spiropyran or gold nanoparticles that undergo conformational changes or generate heat upon specific wavelength irradiation (UV, NIR), enabling precise spatiotemporal control.

- Magnetic-responsive: Embedding iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe₃O₄) to allow remote actuation, mechanical stimulation, or targeted drug delivery via external magnetic fields.

- Humidity-Responsive: Using hydrogels with hydrophilic networks (e.g., cellulose derivatives) that undergo shape transformation via water absorption, mimicking plant movements.

2. Quantitative Data Summary:

Table 1: Common Stimuli-Responsive Materials and Their Key Properties

| Material Class | Example Material | Stimulus | Key Quantitative Property | Typical Response Time | Application in Scaffolds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermoresponsive | pNIPAM-co-Gelatin | Temperature (LCST: ~32°C) | Volume change: Up to 80% shrinkage | Seconds to minutes | Cell sheet engineering, dynamic pores |

| pH-Responsive | Chitosan/Alginate hydrogel | pH (Acidic: 5.5-6.5) | Swelling Ratio: 300-600% increase | Minutes to hours | Drug delivery in inflamed tissue |

| Photo-responsive | Methacrylated Hyaluronic Acid + LAP photoinitiator | UV/Blue Light (365-405 nm) | Gelation Time: 5-30 s | Seconds | Spatially controlled stiffness patterning |

| Magnetic-responsive | GelMA + Fe₃O₄ NPs (10-20 nm) | Magnetic Field (50-200 mT) | Elastic Modulus Shift: 15-25 kPa change | Milliseconds | Remote mechanical conditioning of cardiac tissue |

| Shape Memory Polymer | PCL/PLGA blends | Temperature (Tₜ: 40-55°C) | Shape Recovery: >95% | 10-60 seconds | Self-fitting bone grafts |

Table 2: Comparative Performance of 4D vs. 3D Printed Scaffolds in Key Regeneration Models

| Tissue Target | 3D Scaffold Outcome (Static) | 4D Scaffold Outcome (Dynamic) | Key Stimulus | Measured Improvement (4D vs 3D) | Reference Year (est.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular | Limited endothelialization, no anastomosis. | Guided self-tubulation, improved anastomosis potential. | pH / Temperature | ~40% increase in endothelial cell alignment & coverage. | 2023 |

| Cartilage | Fixed stiffness, may impede integration. | Dynamic stiffness matching native tissue. | Mechanical Load / Enzyme | 2.1-fold increase in glycosaminoglycan (GAG) production. | 2022 |

| Neural | Static guidance conduits. | Gradually contracting conduits for axon tension. | Temperature | 35% faster axonal elongation rate observed. | 2023 |

| Bone | Pre-defined porosity, difficult implantation. | Shape-memory for minimally invasive delivery. | Temperature (Body) | 50% reduction in surgical incision size required. | 2022 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication and Testing of a Thermoresponsive 4D Printed Bone Scaffold

Aim: To create a shape-memory poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL)-based scaffold that self-expands at body temperature for cranial bone defect repair.

Materials:

- Polymer: PCL (Mn 50,000), Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA 85:15).

- Solvent: Dichloromethane (DCM).

- Printer: Extrusion-based 3D bioprinter with heated nozzle and cooled print bed.

- Characterization: Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC), Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer (DMA), Micro-CT.

Methodology:

- Ink Preparation: Dissolve PCL and PLGA (70:30 wt%) in DCM (30% w/v) overnight to form a homogeneous viscous solution.

- Temporary Shape Printing:

- Printer Settings: Nozzle Temp: 75°C, Bed Temp: 5°C, Pressure: 250 kPa, Nozzle Diameter: 250 µm, Print Speed: 8 mm/s.

- Print a compressed lattice scaffold (e.g., 10x10x2 mm) with 70% infill. The rapid cooling on the cold bed "freezes" the temporary shape.

- Shape Fixing: Anneal the printed scaffold at 40°C (above PCL's melting point but below its flow point) for 2 hours, then cool to room temperature under constraint.

- Shape Recovery Testing:

- Deploy the scaffold in a 37°C phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) bath.

- Quantitative Analysis: Use time-lapse imaging to measure the recovery of the z-axis height every 30 seconds for 15 minutes.

- Calculate Shape Recovery Ratio (Rᵣ): Rᵣ(%) = (εₘ - εᵤ) / εₘ * 100%, where εₘ is the pre-deformed strain and εᵤ is the residual strain after recovery.

- Cell Seeding & Culture: Sterilize recovered scaffolds in 70% ethanol and UV. Seed with human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs, 1x10⁵ cells/scaffold) and culture in osteogenic medium for 21 days. Assess viability (Live/Dead assay), proliferation (DNA content), and differentiation (ALP activity, Calcium deposition).

Protocol 2: Photopatterning Stiffness Gradients in a 4D Hydrogel for Chondrogenesis

Aim: To create a spatially controlled, dynamically stiffening hydrogel to direct stem cell differentiation into zonally stratified cartilage.

Materials:

- Hydrogel Precursor: Methacrylated gelatin (GelMA, 5-10% w/v).

- Photoinitiator: Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP, 0.1% w/v).

- Light Source: Digital micromirror device (DMD)-based projector (405 nm).

- Cells: hMSCs or chondrocytes.

Methodology:

- Hydrogel Solution: Dissolve GelMA and LAP in PBS at 37°C. Mix with cells at a density of 5x10⁶ cells/mL. Keep in dark until exposure.

- Dynamic Stiffness Patterning:

- Pour cell-laden solution into a mold.

- First Exposure (Homogeneous Soft Gel): Expose entire construct to a low UV intensity (3 mW/cm²) for 20 seconds to create a soft network (E ~2-5 kPa).

- Second Exposure (Gradient Stiffening): Using the DMD projector, expose specific regions (simulating deep zone) to a higher intensity pattern (10 mW/cm²) for 60 seconds. This secondary crosslinking increases local modulus (E ~15-20 kPa).

- Culture and Analysis: Culture constructs for 28 days. Analyze spatially:

- Mechanics: Perform atomic force microscopy (AFM) indentation maps across the stiffness gradient.

- Biochemistry: Section and stain for zonal markers: collagen type II (all zones), collagen type X (hypertrophic zone), proteoglycans (Safranin O).

- Gene Expression: Laser capture microdissection of soft vs. stiff regions followed by qPCR for SOX9, ACAN, COL2A1.

Visualizations

Title: 4D Scaffold Stimulus-Response Logic Chain

Title: Shape Memory Polymer Scaffold Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for 4D Printing Scaffold Research

| Item | Function in 4D Printing Research | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Methacrylated Natural Polymers (GelMA, HA-MA) | Photo-crosslinkable hydrogel base providing cell-adhesive motifs and tunable mechanical properties. Crucial for light-responsive systems. | GelMA degree of substitution (DoS) ~60-80% for optimal printability and crosslinking. |

| Thermoresponsive Polymer (pNIPAM) | Enables temperature-driven shape/volume changes or cell detachment via its LCST transition near physiological range. | Often copolymerized with gelatin or acrylates to improve bioactivity and mechanical integrity. |

| Lithium Phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | A biocompatible, water-soluble photoinitiator activated by blue/UV light (405 nm). Enables high-resolution photopatterning. | Preferred over Irgacure 2959 due to faster kinetics and longer wavelength activation. |

| Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (Fe₃O₄, 10-50 nm) | Provides magnetic responsiveness for remote actuation, mechanical stimulation, or hyperthermia-based therapy. | Surface functionalization (e.g., with -COOH) is critical for stable dispersion in hydrogel inks. |

| Digital Micromirror Device (DMD) Projector | Enables maskless, high-resolution spatial patterning of light for precise 2D/3D photopolymerization within hydrogels. | Core tool for creating complex, grayscale stiffness gradients within a single construct. |

| Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer (DMA) with Humidity/Temp Chamber | Characterizes the viscoelastic properties and shape-memory behavior of materials under controlled stimuli (temp, humidity). | Essential for quantifying recovery ratio (Rᵣ) and fixity ratio (R_f). |

| Micro-Computed Tomography (Micro-CT) Scanner | Non-destructively images and quantifies the 3D architecture, porosity, and mineral density of scaffolds pre- and post-stimulus. | Critical for verifying internal shape transformation and bone ingrowth in vivo. |

Overcoming Bioprinting Hurdles: Troubleshooting Printability, Resolution, and Long-Term Stability

Application Notes

Within the broader thesis on 3D bioprinting for tissue regeneration, the bioink formulation is the critical determinant of translational success. It represents a tri-lemma where optimizing for one property (e.g., printability) often compromises another (e.g., cell viability or mechanical strength). These notes synthesize current research to guide the design of bioinks that effectively balance these competing demands for specific tissue engineering applications, such as cartilage, bone, and vascularized soft tissues.

Key Parameter Interdependencies

The core challenge lies in the intrinsic conflict between bioink viscosity, crosslinking mechanisms, and biocompatibility. High-viscosity materials (e.g., high-concentration alginate) enhance printability and shape fidelity but increase shear stress during extrusion, reducing cell viability. Conversely, low-viscosity bioinks are gentle on cells but lack structural integrity. Crosslinking strategies (ionic, UV, enzymatic) must be rapid enough to stabilize the structure yet mild enough to maintain high cell functionality.

Current Strategies for Balance

Advanced strategies focus on composite (hybrid) bioinks and multi-material printing. For instance, a gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA)-alginate composite combines the excellent cell-responsive properties of GelMA with the rapid ionic crosslinking of alginate, providing immediate structural support during printing while allowing for longer-term cellular remodeling. Sacrificial bioinks (e.g., Pluronic F-127) are used to create perfusable channels within a more rigid, cell-laden bulk matrix, addressing the need for vascularization without compromising the scaffold's overall mechanical integrity.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluation of Bioink Printability and Fidelity

Objective: To quantitatively assess the extrudability, shape fidelity, and resolution of a candidate bioink. Materials: Bioprinter (extrusion-based), bioink, pressurized air or mechanical plunger, Petri dish, imaging system (microscope/camera), image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ).

Methodology:

- Bioink Loading: Load 3 mL of bioink into a sterile cartridge fitted with a tapered nozzle (diameter: 22G-27G). Avoid introducing air bubbles.

- Print Parameter Calibration: Set initial parameters: Pressure (5-25 kPa), print speed (5-15 mm/s), nozzle height (0.5-1 mm from print bed).

- Filament Test: Print a straight, 30 mm long filament onto a dry Petri dish.

- Fidelity Analysis: Immediately image the filament. Measure filament width at 5 points. Calculate the filament uniformity ratio (Standard Deviation / Mean Width). A lower ratio indicates higher uniformity.

- Grid Structure Printing: Print a 10x10 mm, 2-layer lattice structure with a 1 mm strand spacing.

- Shape Fidelity Analysis: Image the grid from a top-down view. Measure the pore area at 5 locations. Calculate the pore uniformity and compare to the designed pore area (1 mm²). Quantify strand collapse or spreading.

Data Analysis: