Biomaterials in Controlled Drug Delivery: From Smart Carriers to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the transformative role of biomaterials in controlled drug delivery systems, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Biomaterials in Controlled Drug Delivery: From Smart Carriers to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the transformative role of biomaterials in controlled drug delivery systems, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of material-tissue interactions and the classification of natural, synthetic, and bio-inspired systems. The scope extends to advanced methodologies including stimuli-responsive hydrogels, nanoparticle targeting, and 3D-bioprinted scaffolds for applications in oncology, regenerative medicine, and beyond. The review critically addresses key challenges in biocompatibility, scalability, and immune response, while evaluating optimization strategies through high-throughput screening and AI-driven design. Finally, it offers a comparative assessment of clinical translation pathways, regulatory hurdles, and the efficacy of various biomaterial platforms, synthesizing current trends to forecast future directions in personalized and intelligent therapeutics.

The Foundation of Biomaterial-Driven Drug Delivery: Principles, Materials, and Mechanisms

Defining Biomaterials and Their Evolution in Controlled Release

Biomaterials are substances engineered to interact with biological systems for a medical purpose, ranging from treating or diagnosing diseases to replacing or repairing tissue functions [1]. In the context of controlled drug delivery, these materials serve as the foundational platform for encapsulating, stabilizing, and releasing therapeutic agents in a predetermined manner [2]. Their versatility and adaptability have revolutionized therapeutic outcomes by significantly enhancing drug bioavailability while minimizing adverse effects, thereby addressing the critical limitations of conventional drug delivery systems [1] [3]. The evolution of biomaterials has transitioned from simple, inert carriers to sophisticated, intelligently designed systems capable of responding to dynamic physiological cues, marking a paradigm shift in modern pharmacotherapy.

The core objective of using biomaterials in controlled release is to extend, confine, and target the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) within the diseased tissue, thereby protecting it from premature degradation and ensuring a protected interaction with the biological environment [3]. This is particularly crucial for potent drugs requiring low dosages, substances susceptible to degradation in the gastrointestinal tract, or compounds with undesirable organoleptic properties [3]. By carefully selecting and engineering excipients and biomaterials, formulators can overcome these challenges, achieving precise control over release kinetics and site-specific targeting that was previously unattainable with conventional dosage forms like tablets and capsules [1] [3].

Historical Evolution and Generational Shift

The development of ophthalmic biomaterials provides a clear framework for understanding the broader evolution of biomaterials in controlled release, characterized by a structured transition from passive to highly adaptive systems [4]. This progression reflects the convergence of materials science, biomedical engineering, and pathophysiology, with each generation overcoming specific clinical and technological limitations.

Table 1: Generational Evolution of Biomaterials in Controlled Drug Delivery

| Generation | Core Characteristics | Key Material Examples | Advantages | Limitations | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st: Inert Biomaterials | Chemically/mechanically stable; biologically inert; passive structural support [4] | PMMA, PDMS, PVA, Titanium [4] | Excellent biocompatibility and durability; long-term safety [4] | Lack of bioactivity; no therapeutic interaction; low oxygen permeability [4] | Intraocular Lenses (IOLs), Vitreous Substitutes, Contact Lenses [4] |

| 2nd: Bioactive Biomaterials | Biodegradable; surface reactive; promote tissue integration; controlled drug release [4] | PLGA, PLA, PCL, Chitosan, Hydroxyapatite (Hap), Collagen [4] | Promotes cell adhesion & tissue regeneration; tunable degradation rates [4] | Mechanical weakness; pre-programmed release without real-time adaptability [4] | Biodegradable implants, drug-loaded microspheres (e.g., Ozurdex), regenerative scaffolds [4] |

| 3rd: Actively Interactive Smart Biomaterials | Stimuli-responsive; dynamic, on-demand release capability [4] | PNIPAM, Pluronic F127, PEG-PLGA, ZIF-8 [4] | Spatiotemporally targeted drug delivery; improved therapeutic precision [4] | Complex fabrication; mainly open-loop control; potential biosafety concerns [4] | Temperature-sensitive gels, ROS-scavenging nanocarriers, photothermal materials [4] |

| 4th: Closed-Loop & Autonomous Systems (Emerging) | Integration of sensing, computation, and actuation; mimicry of biological feedback [4] | Zwitterionic hydrogels, conductive nanomaterials, iPSC-GelMA hybrids [4] | Real-time monitoring and adaptive control; personalized & autonomous therapeutic response [4] | Power/miniaturization challenges; significant ethical, data, and regulatory barriers [4] | Smart contact lenses for IOP monitoring, autonomous implants for neurostimulation [4] |

This four-stage model illustrates the functional trajectory from basic structural replacements to intelligently adaptive, cell-instructive platforms. The field is currently advancing through the third generation and into the fourth, leveraging innovations in materials science, microfabrication, and bioelectronics to create systems capable of autonomous, real-time control [4].

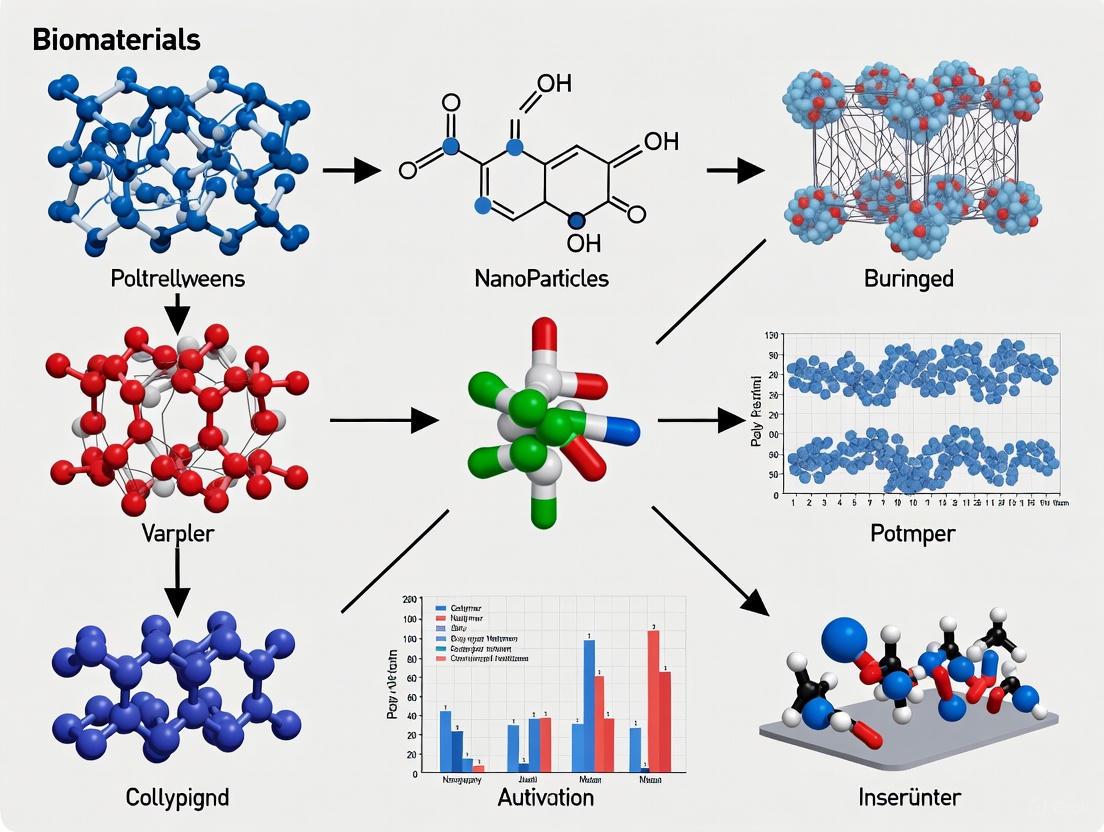

Figure 1: Generational Roadmap of Biomaterials. The evolution progresses from passive, inert systems to bioactive, then stimuli-responsive, and finally towards autonomous, closed-loop platforms [4].

Advanced Biomaterial Systems and Controlled Release Mechanisms

Classification and Material Design

Contemporary biomaterials for controlled release are categorized based on their origin and properties into biobased, biodegradable, and biocompatible materials [1]. Their design must carefully consider parameters such as particle size, with nanoparticles preferred for enhanced bioavailability and targeted delivery, and high surface area, which directly influences drug-loading capacity and interactions with biological components [1]. Advanced rational design focuses on creating versatile and biocompatible polymeric nanoparticles that can protect biologics from degradation, target their delivery, and increase their in vivo half-lives [5]. Key platforms include layer-by-layer nanoparticles, dendrimers, nanogels, self-assembled nanoparticles, and nanocomplexes [5].

Key Release Mechanisms and System Architectures

Controlled drug release is achieved through various fundamental mechanisms, including diffusion, chemical reactions, dissolution, and osmosis, often used in combination [6]. Material-driven strategies have evolved to exploit these mechanisms in sophisticated ways:

- Structurally Engineered Systems: These include bilayer architectures, layer-by-layer assembly techniques, and porous matrix designs that provide structural control over the release profile [7].

- Stimuli-Responsive Mechanisms: These "smart" systems release their payload in response to specific physicochemical triggers in the microenvironment [7] [8]. These triggers include:

- Physical Condition Modulation: Changes in temperature or mechanical force.

- Swelling/Degradation Behavior: Water uptake or material erosion.

- Dynamic Chemical Bond Engineering: Cleavage of bonds by enzymes or pH shifts.

- Crosslinking Network Optimization: Changes in mesh size and porosity.

- Nanotechnology-Enabled Delivery: Polymeric nanoparticles, liposomes, and lipid nanoparticles are engineered with surface modifications to improve gene delivery efficiency and reduce immune responses [8]. For instance, polymer-based nanocarriers like polyethyleneimine (PEI) utilize the "proton sponge" effect to enhance endosomal escape, while liposomes benefit from high biocompatibility and surface functionalization for targeted delivery [8].

Table 2: Advanced Biomaterial Platforms for Controlled Release

| Platform | Key Components | Release Mechanism | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intelligent Hydrogels | Chitosan, PVA-CMC, Dragon's blood resin, Sage extract [8] | Swelling/degradation; response to pH, temperature, or enzymatic activity [8] | Fast-gelling hydrogel for periodontal regeneration; anti-inflammatory wound dressing [8] |

| Branched Peptide-Based Materials | Dendritic peptide structures, natural polymers [9] | Self-assembly; controlled degradation due to slower degradation rates and greater stiffness [9] | Drug delivery systems, wound healing scaffolds, tissue engineering constructs [9] |

| Electrospun Nanofibers | Various biodegradable polymers (e.g., PLGA, PLA) [8] | Diffusion; high surface area and tunable porosity facilitate localized delivery [8] | Diabetic wound healing scaffolds, serving as localized drug delivery systems and structural supports [8] |

| Polymeric Nanoparticles | PLGA, PLA, PEG-PLGA, PEI [8] [5] | Diffusion; degradation; "proton sponge" effect for endosomal escape [8] [5] | Delivery of biologics; cancer therapy; oocyte cryopreservation (PLGA-RES nanocomposite) [8] [5] |

| Motile Microrobots | Hydrogel matrix, magnetic components [8] | Magnetically propelled penetration; sustained release from hydrogel matrix [8] | Co-delivery of drugs for osteosarcoma treatment under external magnetic field guidance [8] |

Experimental Analysis and Computational Modeling

Computational Workflow for Release Kinetics

Understanding and predicting drug release from porous polymeric biomaterials is fundamental to rational design. A leading computational methodology integrates mass transfer simulation with artificial intelligence (AI) to create highly accurate predictive models [10]. The workflow begins with the numerical simulation of diffusional mass transfer, described by Fick's second law, which includes a reaction term:

$$\frac{\partial C}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot \left(-D\nabla C\right)=R$$

where C is the drug concentration (mol/m³), t is time (s), D is the drug diffusivity (m²/s), and R is the chemical reaction term [10]. Solving this equation for a specific geometry (e.g., a cylindrical fibrin matrix) generates a comprehensive dataset of concentration (C) values at different spatial coordinates (r, z), typically comprising over 15,000 data points [10].

Figure 2: Computational Workflow for Drug Release Modeling. This integrated approach combines physics-based simulation with machine learning to predict drug concentration distributions [10].

Machine Learning Model Performance

In a critical study evaluating three regression models—Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR), Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), and Gradient Boosting (GB)—the GB model, optimized with the Firefly Optimization (FFA) algorithm, demonstrated superior performance. It achieved an exceptional R² score of 0.9977, indicating near-perfect alignment with the simulation data, along with the lowest Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) [10]. This highlights the power of ensemble ML methods in modeling complex spatial datasets for drug release prediction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and testing of advanced biomaterials for controlled release rely on a specific toolkit of reagents, materials, and methodologies.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biomaterial-Based Drug Delivery

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Specific Example & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Biodegradable Polymers (PLGA, PLA, PCL) | Form the matrix of nanoparticles, microspheres, and scaffolds; control release kinetics via degradation rate [4] [1]. | PLGA microspheres used in Ozurdex; provide sustained release of dexamethasone over several weeks [4]. |

| Stimuli-Responsive Polymers (PNIPAM, Pluronic F127) | Enable "smart," on-demand drug release in response to temperature, pH, or enzyme triggers [4]. | PNIPAM used in temperature-sensitive hydrogels that gel at body temperature for injectable depot formation [4]. |

| Natural Polymers & Peptides (Chitosan, Branched Peptides, Collagen) | Enhance biocompatibility and provide biomimetic properties; can self-assemble into structured scaffolds [8] [9]. | Branched peptides offer slower degradation, greater stiffness, and modularity for designing tissue engineering constructs [9]. |

| Crosslinking Agents | Stabilize hydrogel networks and control mesh size, directly influencing diffusion-based release rates and mechanical strength [7]. | Genipin is used as a natural crosslinker for chitosan hydrogels, modulating its swelling and release profile. |

| Bioactive Glass & Ceramics (Hydroxyapatite, 4555 Bioglass) | Used in composite materials for bone-related applications; offer osteoconductivity and tunable dissolution rates [2]. | Hydroxyapatite (Hap) is used in orbital implants (e.g., Bio-Eye) for its bioactive integration with bone [4]. |

| Computational Modeling Software | Predicts drug release profiles and optimizes biomaterial design in silico, reducing experimental trial and error [10]. | Used to implement Gradient Boosting models with Firefly Optimization for predicting concentration distributions from porous carriers [10]. |

The evolution of biomaterials from inert structural components to intelligently interactive systems has fundamentally transformed the landscape of controlled drug delivery. This journey, delineated by the four-generation roadmap, showcases a clear trajectory toward greater integration with biological processes, culminating in the emerging paradigm of closed-loop, autonomous therapeutic systems [4]. The ongoing integration of AI and machine learning, both in the computational design of materials and the optimization of release kinetics, is poised to further accelerate this evolution [8] [10].

Future research will focus on bridging the gap between laboratory innovation and clinical application. Key frontiers include the development of AI-assisted material design to optimize biomaterial properties for specific therapeutic needs, and a deeper investigation of the interactions between biomaterials and the immune system to ensure long-term safety and efficacy [8]. Furthermore, the expansion of innovative platforms like microrobots and nanofibers into diverse disease contexts will advance their role in personalized medicine [8]. As the field progresses, addressing the challenges of manufacturing complexity, potential toxicity, and comprehensive regulatory frameworks will be essential for translating these groundbreaking biomaterial-based controlled release systems into mainstream clinical practice, ultimately enabling treatments that are precisely tailored to individual patient needs [1].

The development of advanced drug delivery systems (DDSs) represents a paradigm shift in managing complex chronic conditions, including cancer, neurological disorders, and inflammatory diseases. Biomaterials serve as the foundational cornerstone of these systems, engineered to enhance therapeutic efficacy, improve patient compliance, and minimize side effects through precise spatial and temporal control of drug release [11]. Among the diverse array of biomaterials, three key classes have emerged as particularly significant: synthetic polymers like poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and polyethylene glycol (PEG), natural polymers such as chitosan and collagen, and specialized medical ceramics. These materials enable formulators to overcome fundamental biological barriers, including the reticuloendothelial system (RES) clearance, the blood-brain barrier (BBB), and the complex tumor microenvironment [12] [13]. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of these core material classes, detailing their properties, fabrication methodologies, and mechanisms of action within the context of modern controlled drug delivery research.

Synthetic Polymers

PLGA (Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid))

PLGA is a FDA-approved, biodegradable, and biocompatible copolymer widely utilized in drug delivery systems. Its degradation occurs through hydrolysis of ester linkages into lactic acid and glycolic acid, which are metabolized via the Krebs cycle and excreted as carbon dioxide and water [11]. The properties of PLGA, such as degradation rate and drug release kinetics, can be finely tuned by adjusting its molecular weight, lactide to glycolide ratio, and end-group chemistry [11].

- Applications: PLGA-based nanoparticles and microspheres are extensively used for the controlled delivery of small-molecule drugs, proteins, peptides, antibiotics, and antiviral agents. They enhance drug stability, aqueous solubility, and bioavailability while enabling sustained release profiles from weeks to months [11]. Applications span cancer therapy, pain management, and long-acting injectables, with commercial examples including Lupron Depot and Risperdal Consta [11].

- Key Formulation Parameters: The critical quality attributes of PLGA formulations include particle size, size distribution, porosity, and drug loading capacity, all of which significantly influence in vitro and in vivo performance [11] [14]. Factors such as a higher molecular weight, a higher lactide ratio, and acid end caps contribute to lower hydrophilicity and a slower degradation rate [11].

PEG (Polyethylene glycol) and PEGylation

PEG is a hydrophilic, non-ionic synthetic polymer extensively used to modify the surface of drug carriers, such as PLGA nanoparticles, in a process known as PEGylation. This process forms a steric "stealth" corona around the nanoparticle, reducing opsonization and recognition by the immune system [12]. The primary outcome is a significantly extended systemic circulation time, which increases the likelihood of the drug carrier reaching its target site, a crucial advantage in targeted therapies like cancer treatment [12]. Furthermore, PEGylation provides a versatile platform for the subsequent conjugation of targeting ligands (e.g., antibodies, peptides) while maintaining the nanoparticle's stealth properties [12].

Natural Polymers

Chitosan

Chitosan is a natural cationic polysaccharide derived from the deacetylation of chitin, sourced from crustacean shells, fungi, and other biological materials [15] [16]. Its key attributes include excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability, inherent antibacterial activity, and mucoadhesive properties [15]. However, its application can be limited by poor water solubility, rapid in vivo depolymerization, and insufficient mechanical strength, which can be mitigated through chemical modification or blending with other polymers like collagen [15].

- Applications in Drug Delivery: Chitosan's positive charge enables strong interaction with negatively charged lipids and proteins, making it ideal for gene delivery, protein/peptide delivery, and mucosal drug delivery systems [15] [13]. Its composite with collagen is particularly promising for wound healing and tissue engineering due to synergistic hemostatic, antibacterial, and tissue regeneration activities [15].

- Modifications: Derivatives such as carboxymethyl chitosan, quaternized chitosan, and sulfated chitosan have been developed to enhance solubility, biological activity, and functional versatility for specialized drug delivery applications [15].

Collagen

Collagen, the primary fibrous protein in the extracellular matrix of animals, is characterized by a unique triple-helical structure and a primary sequence of repeating Gly-Xaa-Yaa triplets [16]. Marine-derived collagen, sourced from fish skins and scales or jellyfish, is gaining traction as an alternative to terrestrial sources due to its lower immunogenicity, excellent biocompatibility, and superior scaffold-forming properties that facilitate cellular adhesion and proliferation [16].

- Applications in Drug Delivery and Beyond: Collagen's role extends to tissue engineering scaffolds, wound dressings, and as a carrier for controlled drug release [15] [13]. In composites with chitosan, it enhances mechanical strength and positively affects cell proliferation, creating an ideal environment for tissue repair and regeneration [15].

- Formats: Collagen can be processed into various forms, including nanoparticles, nanofibers, hydrogels, films, and sponges, to suit different delivery needs [15].

Ceramics

Medical ceramics are inorganic, non-metallic materials engineered for use within the human body. They are broadly categorized into bioinert and biocompatible ceramics.

- Bioinert ceramics, such as alumina and zirconia, are characterized by high wear resistance, corrosion resistance, and mechanical strength. They do not interact with surrounding tissues and are primarily used in load-bearing dental and orthopedic implants [17] [18].

- Biocompatible ceramics, including hydroxyapatite and bioactive glasses, actively interact with biological tissues. They are osteoconductive (supporting bone growth along their surface) and can undergo osseointegration, making them suitable for bone grafts and coatings on metal implants [17] [18].

A prominent application in drug delivery involves mesoporous silica nanoparticles and other bioactive ceramics. These materials can be engineered as implantable devices for targeted drug delivery, offering low toxicity, adjustable sizes, and the capability for controlled release [18]. Their surfaces can be functionalized with specific ligands to achieve active targeting, and their porous structure allows for high drug loading [17]. Emerging applications include their use in cancer treatment, diagnostics, and hybrid therapeutic systems [18].

Quantitative Data Comparison

The following tables summarize key properties and application parameters for the discussed biomaterial classes.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Key Biomaterial Classes for Drug Delivery

| Material Class | Representative Materials | Key Properties | Degradation Timeline | Primary Drug Delivery Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Polymers | PLGA, PEG | Tunable degradation, biocompatible, excellent processability | Weeks to months [11] | Controlled release kinetics, "stealth" properties (PEG), high drug loading [12] [11] |

| Natural Polymers | Chitosan, Collagen | Inherent bioactivity, biocompatible, biodegradable | Days to weeks [15] | Mucoadhesion (chitosan), innate cell interaction, hemostatic [15] [16] |

| Ceramics | Hydroxyapatite, Zirconia, Bioactive Glass | High compressive strength, wear-resistant, osteoconductive | Non-degradable to years (resorbable) [17] | Osseointegration, high stability, targeted delivery to bone [17] [18] |

Table 2: Influence of PLGA Properties on Drug Release Performance [11] [14]

| PLGA Property | Impact on Degradation & Drug Release | Typical Range/Options |

|---|---|---|

| Lactide:Glycolide Ratio | Higher lactide content slows degradation. 50:50 degrades faster than 75:25 [11]. | 50:50, 65:35, 75:25, 85:15 |

| Molecular Weight | Higher molecular weight extends degradation duration [11]. | 10 kDa to >100 kDa |

| End Group | Acid end group (COOH) leads to faster degradation than ester-capped (alkyl) [11]. | Carboxylate (acid) or Ester (capped) |

| Crystallinity | More crystalline regions slow down water penetration and degradation [14]. | Amorphous to semi-crystalline |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Preparation of PEGylated PLGA Nanoparticles via Emulsion Solvent Evaporation

This is a standard method for synthesizing drug-loaded PEGylated PLGA nanoparticles, as detailed in recent literature [12].

1. Reagent Setup:

- Organic Phase: Dissolve 50 mg of PLGA polymer and 5 mg of the drug (e.g., a chemotherapeutic agent) in 5 mL of a volatile organic solvent (e.g., dichloromethane, DCM).

- Aqueous Phase: Prepare a 1-2% (w/v) aqueous solution of a stabilizer such as polyvinyl alcohol (PVA).

- PEG Solution: Have a solution of PEG-terminated phospholipid (e.g., DSPE-PEG) or PEG polymer ready for post-formation surface coating.

2. Primary Emulsion Formation:

- The organic phase is added to the aqueous PVA solution (typical volume ratio 1:5 to 1:10 organic:aqueous).

- The mixture is immediately emulsified using a high-speed homogenizer (e.g., 10,000-15,000 rpm for 2-5 minutes) or via probe sonication (e.g., 50-100 W for 1-2 minutes in an ice bath) to form a crude oil-in-water (o/w) emulsion.

3. Emulsion Refinement:

- The coarse emulsion is further processed using a high-pressure homogenizer or subjected to extended sonication to reduce the droplet size and achieve a narrow size distribution.

4. Solvent Evaporation:

- The fine emulsion is stirred continuously at room temperature for several hours (typically 3-6 hours) to allow the organic solvent to evaporate, solidifying the nanoparticles.

- Alternatively, pressure can be reduced to accelerate solvent removal.

5. PEGylation and Purification:

- The PEG solution is added to the nanoparticle suspension and stirred to allow the PEG chains to adsorb or anchor onto the PLGA surface, forming the protective corona [12].

- The nanoparticles are collected by ultracentrifugation (e.g., 20,000-30,000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C) and washed 2-3 times with distilled water or Milli-Q water to remove excess PVA, unencapsulated drug, and free PEG.

6. Characterization:

- Size and Zeta Potential: The mean particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and surface charge (zeta potential) are determined using dynamic light scattering (DLS) [12].

- Drug Loading and Encapsulation Efficiency: The drug content is quantified using a validated HPLC or UV-Vis method after dissolving the nanoparticles in a suitable solvent.

Protocol: Fabrication of Chitosan-Collagen Composite Nanoparticles

This protocol outlines the preparation of composite nanoparticles leveraging the synergistic effects of chitosan and collagen [15].

1. Solution Preparation:

- Chitosan Solution: Dissolve medium molecular weight chitosan in a 1% (v/v) acetic acid solution to obtain a 0.5-1 mg/mL concentration. Filter the solution to remove any undissolved particles.

- Collagen Solution: Dissolve type I collagen (from bovine or marine source) in a weak acid solution (e.g., 0.1M acetic acid) or as per manufacturer's instructions to a similar concentration.

2. Composite Formation:

- Under constant magnetic stirring, add the collagen solution dropwise to the chitosan solution. The positive charge of chitosan facilitates a strong electrostatic interaction with the negatively charged residues of collagen, leading to the self-assembly of composite nanoparticles [15].

- Alternatively, the two solutions can be mixed and then subjected to ionic gelation by adding a cross-linker like tripolyphosphate (TPP).

3. Cross-linking:

- To improve the stability of the nanoparticles, a cross-linking agent such as EDC/NHS can be added to the suspension to form covalent amide bonds between the amine groups of chitosan and carboxyl groups of collagen [15].

4. Purification:

- The nanoparticle suspension is dialyzed against distilled water for 24 hours to remove excess acid and cross-linkers, or purified via repeated centrifugation and resuspension cycles.

5. Characterization:

- Similar to the PLGA protocol, the composite nanoparticles are characterized for size, zeta potential, and morphology (e.g., using SEM or TEM).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Biomaterial Fabrication

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| PLGA Resins | Biodegradable polymer matrix for drug encapsulation. | Forming the core of nanoparticles for sustained release [11]. |

| DSPE-PEG | Amphiphilic polymer for PEGylation and stealth coating. | Conjugating to PLGA surface to reduce immune clearance [12]. |

| Chitosan (Various Mw) | Natural cationic polymer for gene/drug delivery and composites. | Forming ionic complexes with DNA or creating composite scaffolds with collagen [15]. |

| Type I Collagen | Natural protein for bioactive scaffolds and composites. | Providing a biomimetic matrix in wound healing dressings [15] [16]. |

| EDC/NHS Crosslinker | Activating carboxyl groups for covalent conjugation to amines. | Anchoring targeting ligands to nanoparticles or crosslinking collagen-chitosan hydrogels [12] [15]. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol | Surfactant and stabilizer in emulsion formulations. | Preventing coalescence of droplets during PLGA nanoparticle formation [12]. |

| Hydroxyapatite Powder | Bioceramic for bone tissue engineering and drug delivery. | Fabricating osteoconductive scaffolds or coatings for orthopedic implants [18]. |

Visual Workflows and Logical Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate the strategic selection of biomaterials and the experimental workflow for nanoparticle synthesis.

Diagram 1: Biomaterial Selection Strategy

Diagram 2: Nanoparticle Synthesis Workflow

Within the broader thesis on the role of biomaterials in controlled drug delivery systems, understanding the fundamental release mechanisms is paramount. These mechanisms—diffusion, degradation, and stimuli-response—dictate the spatiotemporal control of therapeutic agent release, thereby directly influencing the efficacy and safety of treatments for complex diseases [7] [19]. The evolution from simple passive coverage to advanced, multifunctional dressing systems underscores the critical need for material-driven drug release strategies that can be precisely engineered [7]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of these core release mechanisms, framing them within the context of contemporary biomaterial innovations such as intelligent responsive hydrogels, nanoparticle-hydrogel hybrids, and enzyme-triggered systems [8] [20] [21]. By synthesizing recent advancements and detailed methodologies, this guide aims to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to design next-generation drug delivery platforms.

Core Release Mechanisms in Biomaterials

The controlled release of bioactive agents from biomaterials is governed by three primary mechanisms, which can operate in isolation or in concert. These mechanisms are the foundation for achieving tailored release profiles that meet specific therapeutic needs.

Diffusion-Controlled Release

Diffusion-controlled release is driven by the concentration gradient of the drug between the carrier matrix and the external environment. The drug's path through the biomaterial's structure is the critical rate-determining step. This mechanism is dominant in reservoir systems (where a drug core is surrounded by a polymeric membrane) and matrix systems (where the drug is dispersed throughout a polymer network) [19]. The porosity, swelling behavior, and structural architecture of the biomaterial—such as in bilayer or layer-by-layer assemblies—exert precise control over the diffusion pathway [7]. In nanoparticle-hydrogel hybrids, molecular interactions (electrostatic forces, hydrogen bonding) significantly influence the diffusion rate and the initial burst release [21].

Degradation-Controlled Release

Degradation-controlled release occurs as the biomaterial matrix undergoes chemical breakdown, typically through hydrolysis or enzymatic cleavage, which liberates the encapsulated drug. The rate of drug release is thus directly coupled to the rate of polymer chain scission [19]. Common biodegradable polymers include poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), polylactic acid (PLA), and polyglycolic acid (PGA), which break down into non-toxic byproducts [19]. Engineers can tailor drug release profiles by manipulating the polymer's chemical composition, crystallinity, and molecular weight to achieve a desired degradation rate, ranging from days to months. This mechanism is fundamental to applications where the biomaterial serves a temporary purpose, such as in bioresorbable stents or tissue engineering scaffolds [19].

Stimuli-Responsive Release

Stimuli-responsive, or "smart," release mechanisms enable on-demand drug delivery in response to specific internal (endogenous) or external (exogenous) triggers. This provides a high level of spatial and temporal precision, minimizing off-target effects [8] [22].

Endogenous Stimuli: These are pathological abnormalities in the disease microenvironment. Systems can be engineered to respond to:

- pH: The slightly acidic pH of tumor microenvironments or the pH gradient in cellular compartments (endosomes/lysosomes) can trigger drug release [22] [23].

- Enzymes: Overexpressed enzymes (e.g., matrix metalloproteinases) at disease sites can cleave specific peptide sequences or chemical bonds incorporated into the biomaterial, leading to a highly specific release [20].

- Redox Potential: The significant difference in glutathione concentration between the intracellular and extracellular spaces can degrade materials containing disulfide bonds [22].

Exogenous Stimuli: These are externally applied physical triggers that allow for precise, remote-controlled release:

- Light: Near-infrared (NIR) light can be used with photothermal agents like MXene to generate heat, causing a structural change in the carrier and subsequent drug release [22].

- Magnetic Fields: Magnetic nanoparticles embedded in a hydrogel can be activated by an alternating magnetic field to generate heat, facilitating drug release [21].

- Ultrasound: Ultrasound waves can induce cavitation or thermal effects that disrupt the structure of nanocarriers, releasing their payload [22] [23].

Table 1: Comparison of Fundamental Release Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Key Principle | Trigger/Driver | Common Biomaterials | Release Kinetics Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diffusion | Molecular motion down a concentration gradient | Concentration gradient | Alginate, Chitosan, PVA hydrogels, Layer-by-layer assemblies [7] [21] | Often first-order (Fickian); can exhibit initial burst release |

| Degradation | Erosion of the carrier matrix | Hydrolytic or enzymatic cleavage of polymer chains | PLGA, PLA, PGA, Chitosan [8] [19] | Often zero-order (constant release) possible; dependent on degradation rate |

| Stimuli-Response | Material transformation upon stimulus | pH, enzymes, redox, light, temperature, magnetic field [22] | Peptide-based systems, MXenes, PVA-CMC hydrogels, smart polymers [20] [24] [22] | Pulsatile or on-demand; highly tunable based on stimulus sensitivity |

Advanced Hybrid Systems and Combined Mechanisms

In advanced drug delivery systems, these fundamental mechanisms are rarely isolated. Hybrid systems are designed to leverage multiple mechanisms sequentially or synergistically to overcome complex biological barriers and meet dynamic therapeutic demands [21]. A prominent example is the nanoparticle-hydrogel hybrid material, which combines the high drug-loading capacity and targeted potential of nanoparticles with the biocompatibility and sustained-release properties of hydrogel matrices [21].

In such systems, the release profile is a complex interplay of mechanisms: initial diffusion from the hydrogel matrix, followed by the release of drugs encapsulated in nanoparticles, which may itself be controlled by diffusion, degradation, or a stimulus. For instance, a drug-loaded polymeric NP within a hydrogel may first be released from the hydrogel via diffusion, and once at the target site, the NP may release its payload in response to a local pH change or enzyme [21]. This multi-stage release allows for sophisticated control, such as sustained release of one therapeutic agent while providing on-demand release of another [8]. The design of these composites requires a deep understanding of the molecular interactions between the drug, nanoparticle, and hydrogel network to predict and optimize the overall release behavior [21].

Diagram 1: Hybrid system release pathways.

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Release Mechanisms

Robust experimental characterization is essential to validate and quantify drug release mechanisms. Below are detailed methodologies for key experiments.

Protocol: In Vitro Drug Release Kinetics under Physiological and Stimuli-Responsive Conditions

Objective: To quantify the drug release profile from a biomaterial system under sink conditions and to evaluate the impact of specific stimuli (e.g., pH, enzyme, light) on the release kinetics [24] [22].

Materials:

- Test articles: Drug-loaded biomaterial (e.g., hydrogel, nanoparticles, hybrid composite)

- Release medium: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4; and modified media for stimuli tests (e.g., acetate buffer for pH 5.5, or medium with specific enzyme)

- Dialysis bags or membrane-less methods in vials

- Thermostated water bath or shaker incubator (37°C)

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer, HPLC, or other analytical instrument for drug quantification

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Precisely weigh a known amount of drug-loaded biomaterial (e.g., 100 mg of hydrogel) and place it into a dialysis bag (MWCO selected to retain the carrier but allow free drug passage). Seal the bag securely.

- Initial Setup: Immerse the dialysis bag in a large volume (e.g., 50-100x the sample volume) of pre-warmed (37°C) release medium (PBS, pH 7.4) to maintain sink conditions. Place the vessel in a shaker incubator at a constant, low agitation speed (e.g., 50 rpm).

- Sampling: At predetermined time intervals (e.g., 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 48, 72 hours...), withdraw a fixed aliquot (e.g., 1 mL) from the external release medium. Immediately replace with an equal volume of fresh, pre-warmed medium to maintain constant volume and sink conditions.

- Analysis: Quantify the drug concentration in each withdrawn sample using a pre-validated analytical method (e.g., HPLC-UV, fluorescence spectroscopy). Construct a calibration curve with known drug concentrations for accurate quantification.

- Stimuli-Responsive Triggering: For stimuli tests, after a baseline period (e.g., 4 hours), replace the entire medium with a trigger-specific medium (e.g., low pH buffer, enzyme solution). For external triggers like NIR light, expose the sample to a laser (e.g., 808 nm, 1.5 W/cm²) for a set duration (e.g., 5 minutes) at specific time points, then continue sampling as before.

- Data Processing: Calculate the cumulative drug release (%) at each time point. Plot cumulative release (%) versus time to generate the release profile. Fit the data to mathematical models (e.g., Zero-order, First-order, Higuchi, Korsmeyer-Peppas) to infer the dominant release mechanism.

Protocol: Evaluating Biomaterial Degradation and Its Correlation to Drug Release

Objective: To monitor the mass loss and morphological changes of a biodegradable biomaterial over time and correlate this degradation profile with the observed drug release profile [19].

Materials:

- Pre-weighed samples of the drug-loaded biodegradable polymer (e.g., PLGA microspheres, chitosan scaffold)

- Degradation medium (e.g., PBS, pH 7.4, with or without 0.1 mg/mL lipase or other relevant enzymes)

- Analytical balance (precision ±0.01 mg)

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

- Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) system

Procedure:

- Baseline Measurement: Precisely weigh (W₀) and photograph each sample. For a subset of samples, characterize initial molecular weight (Mₙ₀) via GPC and initial morphology via SEM.

- Incubation: Immerse each sample in a vial containing degradation medium and incubate at 37°C under gentle agitation.

- Monitoring: At predetermined time points (e.g., weekly), remove samples in triplicate from the incubation medium.

- Mass Loss: Rinse the samples with deionized water, lyophilize, and accurately weigh the dry mass (Wₜ). Calculate the remaining mass percentage: (Wₜ / W₀) * 100%.

- Molecular Weight Change: Analyze the molecular weight (Mₙₜ) of the dried polymer using GPC.

- Morphological Analysis: Image the samples using SEM to observe surface erosion, pore formation, and cracks.

- Correlation: Plot the degradation profile (remaining mass % and Mₙ decrease over time) alongside the drug release profile from Protocol 4.1. A strong correlation between polymer mass loss/molecular weight decrease and cumulative drug release indicates a degradation-controlled mechanism.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Key Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Experiment | Key Characteristics & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | A biodegradable polymer for degradation-controlled release studies [8] [19]. | Varying lactide:glycolide ratios and molecular weights allow tuning of degradation rates from weeks to months. |

| Chitosan | A natural, biocompatible polymer for forming pH-sensitive hydrogels and nanoparticles [8]. | Positively charged at low pH, enabling swelling and drug release in acidic environments like tumors. |

| MXene (Ti₃C₂Tₓ) | A 2D nanomaterial acting as a photothermal agent for exogenous stimuli-response [22]. | High NIR photothermal conversion efficiency; enables light-triggered drug release from composite systems. |

| Polyethyleneimine (PEI) | A cationic polymer used for its "proton sponge" effect to enhance endosomal escape [8]. | Facilitates release from degradation in acidic cellular compartments (endosomes). |

| Enzyme (e.g., MMP-2) | A biological trigger to study enzyme-responsive drug release [20]. | Must be specific to the cleavable peptide sequence (e.g., GPLG↓V) engineered into the biomaterial. |

| Dialysis Membrane | A semi-permeable barrier for conducting in vitro release studies under sink conditions. | Molecular Weight Cut-Off (MWCO) must be selected to retain the biomaterial carrier but allow free drug diffusion. |

Visualization of Stimuli-Responsive Pathways

Stimuli-responsive systems rely on specific chemical or physical pathways to trigger drug release. The following diagram illustrates the sequence of events for endogenous and exogenous triggers.

Diagram 2: Stimuli-responsive drug release pathways.

The strategic manipulation of diffusion, degradation, and stimuli-response mechanisms is the cornerstone of advanced controlled drug delivery. As biomaterials science progresses, the integration of these mechanisms into sophisticated, multi-functional systems is becoming the standard for addressing complex therapeutic challenges. Future directions point towards the increased use of AI-assisted biomaterial design to optimize these release properties, a deeper investigation into biomaterial-immune system interactions, and the expansion of innovative platforms like microrobots and hybrid composites into diverse disease contexts [8] [25]. By mastering these fundamental release mechanisms and their interplay, researchers can continue to push the boundaries of personalized medicine, developing safer, more effective treatments that dynamically respond to the needs of the patient.

The Extracellular Matrix (ECM) as a Blueprint for Biomaterial Design

The Extracellular Matrix (ECM) is a highly complex, hierarchically organized microenvironment comprised of natural polymers, growth factors, and signaling molecules that collectively provide a structurally supportive network filled with biomolecule cues regulating cell behavior [26]. Far from being a passive structural element, the ECM actively orchestrates fundamental cellular processes—including adhesion, migration, proliferation, and differentiation—through integrated biomechanical and biochemical cues [27]. This regulatory capacity arises from its tissue-specific composition and architecture, making it indispensable for physiological homeostasis and a critical blueprint for biomaterial design in regenerative medicine and controlled drug delivery [27]. The composition of the ECM varies significantly across different tissue types and developmental stages, with its main components including collagens, elastin, laminin, fibronectin, proteoglycans, and glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) [28]. Furthermore, the ECM serves as a dynamic reservoir for various growth factors, including fibroblast growth factor (FGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and transforming growth factor (TGF-β), which are released in a tightly regulated manner to guide tissue development and repair processes [28]. The rising global burden of chronic diseases and organ failure has intensified the demand for advanced therapeutic strategies that address the limitations of conventional treatments, positioning ECM-inspired biomaterials as promising platforms for enhancing controlled drug delivery systems [27].

Decellularized ECM (dECM) as a Fundamental Biomaterial Platform

The Decellularization Process and Its Impact on ECM Properties

Decellularization represents a cornerstone technique in ECM-based biomaterial design, focused on removing cellular components from native tissues while preserving the intrinsic ECM structure and composition [28]. The fundamental objective is to eliminate immunogenic cellular materials—including DNA and cell membranes—that could trigger adverse host responses, while retaining the complex architecture and bioactive molecules that constitute the functional ECM [26] [28]. This process produces decellularized ECM (dECM) that can be sourced from allogeneic or xenogeneic tissues and subsequently fabricated into various biomaterial formats, including membranes, hydrogels, bio-inks, and porous structures for applications in biomaterial implants, disease models, and drug screening platforms [26].

Decellularization methodologies can be broadly classified into three main categories, each with distinct mechanisms and effects on ECM properties [28]:

- Chemical Methods: Utilize surfactants (ionic, non-ionic, zwitterionic), acids, and alkaline solutions to solubilize cell membranes and disrupt DNA-protein interactions.

- Enzymatic Methods: Employ nucleases (e.g., DNase, RNase) and proteases (e.g., trypsin) to degrade nucleic acids and protein components.

- Physical Methods: Apply freezing-thawing, mechanical pressure, and perfusion to mechanically disrupt cells and facilitate their removal.

The efficacy of decellularization and the preservation of key ECM components are quantitatively assessed through specific benchmarks, as detailed in Table 1 [28] [29].

Table 1: Key Quantitative Benchmarks for Effective Tissue Decellularization

| Parameter | Target Value | Analytical Methods | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Content | <50 ng per mg of dry tissue weight | DNA quantification assays | Reduces immunogenic potential and inflammatory responses |

| Collagen Retention | No significant decrease compared to native tissue | Hydroxyproline assay, SDS-PAGE | Maintains structural integrity and mechanical strength |

| Glycosaminoglycan (GAG) Content | No significant decrease compared to native tissue | DMMB assay, Alcian blue staining | Preserves growth factor binding capacity and hydration |

| Scaffold Porosity | ~75% (tissue-dependent) | SEM analysis, mercury porosimetry | Facilitates cell infiltration, vascularization, and nutrient diffusion |

| Pore Size | ~123 μm (for skeletal muscle scaffolds) | SEM analysis | Enables cell migration and tissue integration |

The successful decellularization of skeletal muscle tissue, for instance, demonstrates a dramatic reduction in DNA content from 1865 ± 398.3 ng/mg in native tissue to 15.11 ± 8.13 ng/mg in decellularized tissue, while effectively preserving collagen (41.01 ± 7.17 μg/mg vs 55.33 ± 10.14 μg/mg in native tissue) and GAG content (49.30 ± 2.45 ng/mg vs 54.08 ± 2.94 ng/mg in native tissue) [29]. These parameters are critical for maintaining the bioactivity and mechanical functionality of the resulting dECM scaffolds for drug delivery applications.

dECM as a Versatile Drug Delivery Carrier

Decellularized ECM biomaterials offer immense potential as versatile drug delivery systems, with various encapsulation, bulk absorption, and conjugation techniques demonstrating success in achieving controlled and localized release of therapeutic agents [26]. From growth factors to small molecules, dECM-based materials can deliver targeted bioactive signals while mimicking the native tissue environment, thus enhancing regenerative outcomes [26]. The inherent presence of GAGs in dECM, particularly heparan sulfate, provides natural binding sites for numerous growth factors through electrostatic interactions, enabling their protection, retention, and sustained release at the target site [28] [29]. This intrinsic property has been strategically enhanced through the immobilization of heparin—a structural analog of heparan sulfate—onto dECM scaffolds to create high-affinity binding platforms for therapeutic growth factors [29].

Table 2: Growth Factor Release Profiles from Heparinized dECM Scaffolds

| Growth Factor | Initial Concentration in PRP | Release Duration (DSMS-HP) | Cumulative Release Percentage | Therapeutic Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDGF-BB | 16998.7 ± 1073.3 pg/mL | 4 days | 56.13 ± 2.91% | Angiogenesis, cell proliferation |

| FGF2 | 68.33 ± 28.18 pg/mL | 4 days | 72.22 ± 9.58% | Tissue repair, morphogenesis |

| VEGF | 1207.47 ± 292.166 pg/mL | 4 days | 67.78 ± 14.66% | Blood vessel formation |

As illustrated in Table 2, heparinized dECM scaffolds (DSMS-HP) demonstrate significantly prolonged release kinetics compared to non-heparinized controls (DSMS-P), with growth factors being released over approximately 4 days versus 1-2 days for the control group [29]. This sustained release profile is particularly valuable for therapeutic applications requiring prolonged growth factor exposure to effectively promote processes such as angiogenesis, cell proliferation, and tissue regeneration [29].

Experimental Protocols for dECM-Based Drug Delivery Systems

Protocol: Fabrication of Heparinized dECM Scaffolds for Growth Factor Delivery

This protocol details the methodology for creating affinity-based drug delivery systems using heparin-functionalized dECM, enabling controlled, prolonged release of growth factors from platelet-rich plasma (PRP) for enhanced skeletal muscle regeneration [29].

Materials and Reagents:

- Native skeletal muscle tissue (allogeneic or xenogeneic source)

- Ionic and non-ionic detergents (e.g., SDS, Triton X-100)

- DNase and RNase solutions

- N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide (EDC)

- Heparin sodium salt

- Platelet-rich plasma (PRP)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Cryostat or freeze-drying system

Procedure:

- Tissue Decellularization:

- Rinse native skeletal muscle tissue thoroughly in distilled water to remove residual blood components.

- Immerse tissue in 1% (w/v) SDS solution for 24-48 hours with continuous agitation.

- Treat with 1% (v/v) Triton X-100 for 6 hours to remove residual cellular membranes and lipids.

- Incubate in DNase/RNase solution (50 U/mL in PBS) for 3 hours at 37°C to degrade nucleic acids.

- Wash extensively with distilled water for 72 hours to remove all detergent residues.

Scaffold Fabrication:

- Mince the decellularized tissue into small fragments and digest using an acidic pepsin solution to create a pre-gel solution.

- Neutralize the digest with NaOH and reconstitute in PBS to the desired concentration.

- Crosslink the dECM solution using EDC/NHS chemistry (5:2 molar ratio) at 4°C for 6 hours.

- Pour the crosslinked solution into molds and freeze at -80°C for 2 hours, followed by lyophilization for 48 hours to create porous scaffolds.

Heparin Functionalization:

- Prepare heparin solution (10 mg/mL in MES buffer, pH 5.5).

- Activate heparin carboxyl groups using EDC/NHS (5:2 molar ratio) for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Incubate dECM scaffolds in the activated heparin solution for 24 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation.

- Wash extensively with PBS to remove unbound heparin.

PRP Loading:

- Immerse heparinized scaffolds in PRP solution for 2 hours at room temperature.

- Remove excess solution and rinse gently with PBS to remove surface-adsorbed proteins.

Quality Control Assessments:

- Verify decellularization efficiency through DNA quantification (<50 ng/mg dry tissue).

- Confirm collagen and GAG retention using hydroxyproline and DMMB assays, respectively.

- Assess scaffold microstructure and porosity using scanning electron microscopy.

- Validate heparin binding through toluidine blue staining.

Protocol: Functional Assessment of dECM Drug Delivery Systems

In Vitro Release Kinetics Study:

- Prepare dECM scaffolds (n=5 per group): DSMS (control), DSMS-H (heparinized), DSMS-P (PRP-loaded), DSMS-HP (heparinized and PRP-loaded).

- Immerse each scaffold in 1 mL of PBS (pH 7.4) and incubate at 37°C with gentle agitation.

- Collect 100 μL of release medium at predetermined time points (1, 2, 4, 8, 24, 48, 72, 96 hours).

- Replace with fresh PBS after each collection to maintain sink conditions.

- Quantify growth factor (PDGF-BB, FGF2, VEGF) concentrations in collected samples using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA).

- Calculate cumulative release percentages and generate release kinetics profiles.

In Vivo Efficacy Assessment in Volumetric Muscle Loss (VML) Model:

- Surgical Procedure:

- Anesthetize adult male mice (8-10 weeks old) using isoflurane inhalation.

- Create a critical-sized defect (approximately 4×4×2 mm) in the tibialis anterior muscle.

- Implant experimental scaffolds (DSMS, DSMS-H, DSMS-P, DSMS-HP) into the defect site.

- Suture the overlying fascia and skin layers separately.

- Post-operative Analysis:

- Euthanize animals at 2, 4, and 8 weeks post-implantation (n=6 per time point).

- Harvest implanted muscles and process for histological analysis (H&E, Masson's trichrome staining).

- Assess angiogenesis through CD31 immunohistochemistry.

- Evaluate myogenic regeneration using desmin and myosin heavy chain immunostaining.

- Quantify host cell migration into the scaffold by measuring cellular density at the implant interface.

ECM-Mimetic Biomaterials for Advanced Drug Delivery

Engineering Synthetic ECM Analogues

While dECM platforms provide exceptional bioactivity, synthetic ECM-mimetic hydrogels have been developed to overcome limitations related to batch-to-batch variability, mechanical tunability, and clinical translation potential [30]. These engineered systems are designed to replicate key features of the native ECM while offering improved reproducibility, defined composition, and tunable physical properties [30]. The polymer backbone of these synthetic hydrogels is typically engineered to reproduce the structural and biochemical features of the ECM, often through the incorporation of key matrix components or bioactive motifs such as hyaluronic acid, collagen, or RGD peptides within the hydrogel network [30].

The integration of nanomaterials into hydrogels represents a significant advancement in this field, substantially expanding their mechanical and functional properties [30]. Nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes, gold nanoparticles, graphene, magnetic nanocomposites, and ceramic nanofillers have been incorporated into hydrogels to enhance their performance through improved mechanical strength, increased electrical conductivity, and enhanced responsiveness to stimuli [30]. These functionalities can be broadly grouped into electromagnetic responsiveness (exemplified by conductive or magnetically aligned systems), mechanical reinforcement (which enhances toughness and stretchability), and stimuli-responsiveness (which enables spatiotemporal control over cell behaviors such as migration and differentiation) [30].

Integrin-Mediated Signaling in Biomaterial Design

Integrins serve as fundamental mediators of bidirectional communication between cells and their ECM microenvironment, playing indispensable roles in tissue repair and regeneration [27]. These transmembrane receptors, composed of α and β subunits, recognize specific ECM components including collagen, fibronectin, and laminin, thereby orchestrating essential cellular processes such as adhesion, migration, proliferation, and survival [27]. The activation of integrin signaling initiates with ECM ligand binding, which induces conformational changes that promote receptor clustering and the assembly of focal adhesion complexes [27]. These specialized structures serve as mechanical and biochemical signaling hubs, recruiting adaptor proteins including talin, vinculin, and paxillin to bridge the connection between integrins and the actin cytoskeleton [27].

The following diagram illustrates the key molecular events in integrin-mediated signaling, which can be strategically leveraged in biomaterial design to enhance regenerative outcomes:

Integrin-Mediated Signaling Pathway

Central to this signaling network is the focal adhesion kinase (FAK) pathway, which, upon activation at Tyr397, recruits Src family kinases to regulate cytoskeletal dynamics and promote cell migration [27]. Parallel MAPK/ERK pathway activation regulates gene expression for proliferation and differentiation, while the PI3K/Akt pathway promotes cell survival in stressful, injured tissue microenvironments [27]. These interconnected pathways function synergistically to ensure appropriate cellular responses during the repair process [27]. The mechanical properties of the ECM exert a profound influence on integrin signaling dynamics, with substrate stiffness, topography, and ligand density collectively modulating the spatial organization and activation state of integrin clusters [27]. This mechanosensitive regulation of integrin function has inspired innovative biomaterial design strategies aimed at recapitulating key aspects of native ECM signaling, particularly through engineered matrices incorporating RGD peptide sequences that demonstrate enhanced capacity to promote cell adhesion and migration through selective engagement of αvβ3 and α5β1 integrins [27].

Experimental Workflow for dECM-Based Drug Delivery System

The following diagram outlines the comprehensive experimental workflow for developing dECM-based drug delivery systems, from tissue processing through functional assessment:

dECM Drug Delivery System Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for dECM-Based Drug Delivery Research

| Reagent/Chemical | Function | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Ionic surfactant for cell membrane disruption and DNA removal | Efficient cellular component removal during tissue decellularization [28] |

| Triton X-100 | Non-ionic surfactant for lipid dissolution | Removal of residual cellular membranes after initial decellularization [28] |

| DNase/RNase Solutions | Enzymatic degradation of nucleic acids | Elimination of immunogenic DNA/RNA fragments from decellularized tissues [28] |

| EDC/NHS Crosslinker | Zero-length crosslinking for scaffold stabilization | Enhancing mechanical properties of dECM scaffolds and conjugating bioactive molecules [29] |

| Heparin Sodium Salt | Glycosaminoglycan analog for growth factor binding | Creating affinity-based delivery systems for sustained growth factor release [29] |

| Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) | Natural source of multiple growth factors | Therapeutic cargo for enhanced tissue regeneration [29] |

| Toluidine Blue | Metachromatic dye for heparin detection | Qualitative assessment of heparin conjugation to dECM scaffolds [29] |

The extracellular matrix serves as an unparalleled blueprint for biomaterial design, providing both structural templates and sophisticated signaling platforms that can be engineered for controlled drug delivery applications [26] [27]. Decellularized ECM platforms offer the distinct advantage of preserving tissue-specific biochemical and architectural cues that are difficult to replicate synthetically, while strategic modifications such as heparin functionalization significantly enhance their capacity for sustained therapeutic delivery [26] [29]. The integration of nanomaterials into ECM-mimetic systems further expands their functionality, enabling enhanced mechanical properties, stimuli-responsiveness, and dynamic control over drug release profiles [30].

Despite these promising advances, challenges remain in standardization, scalability, and immune response modulation [28] [27]. Future directions in ECM-based biomaterial design are directed towards improving ECM-mimetic platforms through the development of more sophisticated biofabrication techniques, including 3D bioprinting with dECM-based bio-inks, and the creation of intelligent, responsive systems that can dynamically adapt to the changing microenvironment during tissue regeneration [26] [28]. By continuing to draw inspiration from the native ECM while leveraging advances in materials science and engineering, researchers can develop increasingly sophisticated biomaterial-based drug delivery systems that bridge the gap between structural mimicry and active biological control, ultimately enabling more effective therapeutic outcomes in regenerative medicine [27].

The interdisciplinary field of biomaterials for controlled drug delivery represents a critical convergence of material science, pharmaceutical technology, and regenerative medicine, driving revolutionary approaches to therapeutic interventions. Over the past two decades, this domain has evolved from simple passive drug carriers to sophisticated systems capable of dynamic biological interaction and spatiotemporal control over drug release. The growing emphasis on precision medicine and targeted therapies has further accelerated innovation in biomaterial-based delivery platforms, making them indispensable in addressing complex disease states. This bibliometric analysis provides a comprehensive, data-driven overview of the scientific landscape from 2005 to 2024, mapping the evolution, current state, and emerging frontiers in biomaterial-driven regenerative drug delivery research. By systematically examining publication trends, geographical contributions, institutional partnerships, and thematic shifts, this review serves as an invaluable navigational tool for researchers, funding agencies, and policy makers seeking to understand the knowledge architecture of this rapidly advancing field and identify promising trajectories for future investigation [31].

The analysis encompasses global research output from January 2005 to December 2024, with data extracted from the Science Citation Index Expanded (Web of Science Core Collection). This systematic approach enables robust quantification of the field's development through metrics including publication volume, citation impact, geographical distribution, institutional productivity, and keyword evolution. The findings presented herein not only document the remarkable expansion of biomaterials research in drug delivery but also highlight the synergistic integration of once-disparate disciplines including nanotechnology, tissue engineering, and digital health, collectively pushing the boundaries of what is therapeutically possible [31].

Quantitative Analysis of Research Growth

Global Publication Output and Impact

The period from 2005 to 2024 witnessed exponential growth in research output focused on biomaterial-driven drug delivery systems. According to the bibliometric data, a total of 885 scholarly publications were recorded globally on this topic during this twenty-year span. The annual publication count first exceeded 50 in 2017 and surpassed 100 in 2024, reaching its peak at 116 publications in 2023. This trajectory demonstrates a maximum annual growth rate of 32.4%, particularly accelerating in the most recent decade, indicating the field's rapidly increasing importance and research activity [31].

Citation analysis further substantiates the field's growing impact, with publications receiving an average of 9.41 citations per year. The highest impact year was 2010, with an impressive 16.71 citations per publication annually. This pattern suggests that while publication volume has increased dramatically in recent years, the foundational works from the earlier period continue to exert substantial influence, providing theoretical and methodological frameworks that subsequent research has built upon. The sharp increase in publications post-2020 suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic substantially accelerated research activity in this field, potentially due to increased recognition of the importance of advanced delivery systems for novel therapeutics [31].

Table 1: Annual Publication Trends in Biomaterials for Drug Delivery (2005-2024)

| Year Range | Total Publications | Key Milestones | Average Citations/Publication/Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005-2009 | <100 | Foundational period | 12.35 |

| 2010-2014 | ~150 | Accelerated growth | 16.71 (peak in 2010) |

| 2015-2019 | ~300 | Exceeded 50 publications annually | 10.22 |

| 2020-2024 | ~400+ | Exceeded 100 publications annually (2024) | 8.75 |

Geographical Distribution and Collaboration Networks

Research in biomaterials for drug delivery has become a truly global endeavor, with 77 countries/regions contributing to the scientific output. The United States leads in research volume with 259 publications, representing 29.3% of the total output, followed by China with 175 publications (19.8%), and India with 76 publications (8.6%) [31]. When measuring research impact through H-index metrics, the United States maintains dominance (H-index = 78), with China (H-index = 51) and Iran (H-index = 30) completing the top tier [31].

Network analysis has identified the United States and China as central nodes in global research collaboration, with Germany, the United Kingdom, France, India, Italy, South Korea, and Australia comprising additional key contributors. The collaboration network exhibits extensive globalization patterns, featuring three principal knowledge exchange hubs: North America, Europe, and East Asia. This tripartite structure underscores the intercontinental nature of contemporary scientific cooperation and highlights how geographical diversity has strengthened the field's development through cross-pollination of ideas and methodologies [31].

Table 2: Leading Countries in Biomaterials for Drug Delivery Research (2005-2024)

| Rank | Country | Article Counts | Percentage of Total | H-index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | United States | 259 | 29.27% | 78 |

| 2 | China | 175 | 19.77% | 51 |

| 3 | India | 76 | 8.59% | 27 |

| 4 | Iran | 67 | 7.57% | 30 |

| 5 | Italy | 60 | 6.78% | 25 |

| 6 | England | 51 | 5.76% | 24 |

| 7 | Germany | 47 | 5.31% | 22 |

| 8 | South Korea | 45 | 5.09% | 21 |

| 9 | Australia | 43 | 4.86% | 20 |

| 10 | Spain | 40 | 4.52% | 18 |

Leading Institutions and Institutional Networks

The global research landscape encompasses over 1,300 participating institutions, with Harvard University and the University of California System emerging as the most productive institutions (26 publications each), followed closely by the Chinese Academy of Sciences (24 publications) and Universidade do Minho (20 publications) [31]. Bibliometric analysis reveals distinct dimensions of scientific influence, with collaborative network mapping identifying three predominant knowledge hubs centered around the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Zhejiang University, and the National University of Singapore [31].

Citation network analysis demonstrates dense interconnection patterns among high-output institutions, suggesting reciprocal citation behaviors that reinforce their disciplinary leadership. Temporal network visualization tracks the progressive expansion of research contributions, with China, the USA, and European nations driving biomaterial-focused advances in regenerative drug delivery systems. These visualizations confirm two critical trends: the formation of self-reinforcing academic ecosystems among top-tier institutions, and the increasing globalization of interdisciplinary research in advanced therapeutic development [31].

Evolution of Research Foci and Emerging Trends

Journal Distribution and Research Areas

The analysis encompassed 324 journals contributing to global research dissemination in biomaterials for drug delivery. ACTA Biomaterialia and Biomaterials emerged as the predominant sources in this domain, with the remaining high-yield journals primarily concentrating on biomaterial engineering, molecular sciences, and pharmaceutical delivery systems [31]. Application of Bradford's law of scattering facilitated the stratification of journals into three distinct zones, identifying 19 core dissemination channels that accounted for the majority of impactful publications [31].

Analysis of research categories using VOSviewer revealed that the dominant research domains include Materials Science, Engineering, Chemistry, Polymer Science, and Science Technology Other Topics. These focal areas underscore the primary directions of current research and point to promising avenues for future advancements in the field. The persistent strength of polymer science reflects the continuous innovation in polymeric architectures for drug encapsulation and controlled release, while the growing presence of "Science Technology Other Topics" indicates the field's expanding boundaries into emerging interdisciplinary areas [31].

Table 3: Core Journals in Biomaterials for Drug Delivery Research

| Rank | Journal | Article Counts | Primary Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acta Biomaterialia | 33 | Biomaterial engineering and characterization |

| 2 | Biomaterials | 31 | Fundamental biomaterial research |

| 3 | Polymers | 23 | Polymer-based delivery systems |

| 4 | International Journal of Molecular Sciences | 19 | Molecular mechanisms and interactions |

| 5 | Advanced Healthcare Materials | 18 | Translational material applications |

Keyword Evolution and Conceptual Shifts

Keyword analysis over the twenty-year period reveals a significant conceptual evolution in the field. Early research (2005-2010) was dominated by fundamental material concepts such as "biocompatibility," "scaffolds," "hydrogels," and "controlled release." The middle period (2011-2018) showed a shift toward functional sophistication with emerging terms including "targeted drug delivery," "nanoparticles," "stimuli-responsive," and "tissue engineering." The most recent period (2019-2024) demonstrates a focus on precision and personalization, with keywords such as "precision medicine," "organ-on-a-chip," "3D bioprinting," "CRISPR delivery," and "AI-assisted design" gaining prominence [8] [31] [32].

This conceptual trajectory illustrates the field's journey from developing basic biocompatible materials to creating intelligent, responsive systems capable of complex biological interactions. The emerging frontiers highlight the growing integration of digital technologies, computational approaches, and personalized strategies that collectively represent the next evolutionary phase in biomaterial-based drug delivery [8].

Emerging Research Trends and Methodological Innovations

Intelligent Responsive Biomaterials

Stimuli-responsive biomaterials represent one of the most dynamic research frontiers, with materials engineered to react to specific physiological cues or external triggers. Recent innovations include enzyme-responsive biomaterials programmed to undergo structural or functional changes when exposed to specific enzymes associated with disease states [20]. These systems enable precise control over drug release kinetics, particularly beneficial for pathological environments characterized by unique enzymatic signatures, such as tumor microenvironments or inflamed tissues [20].

Thermoresponsive hydrogels represent another advanced category, with systems like chitosan-based fast-gelling hydrogels at body temperature proving particularly useful for irregularly shaped tissue defects [8]. These materials allow controlled release of encapsulated drugs while forming a microenvironment beneficial for tissue regeneration, demonstrating the dual functionality that characterizes next-generation biomaterials. The high porosity of these hydrogels enhances cell penetration and nutrient exchange, making them excellent local delivery platforms for periodontal regeneration and other specialized applications [8].

Diagram 1: Stimuli-Responsive Biomaterial Mechanisms. This diagram illustrates the diverse triggers and therapeutic outcomes of intelligent responsive biomaterials in drug delivery.

Nanotechnology-Enabled Delivery Platforms

Nanotechnology has revolutionized drug delivery by enabling unprecedented precision at cellular and molecular levels. Recent innovations include non-viral vectors such as polymers, liposomes, and lipid nanoparticles, which are engineered with surface modifications to improve gene delivery efficiency and reduce immune responses [8]. Polymer-based nanocarriers like polyethyleneimine (PEI) utilize the "proton sponge" effect to enhance endosomal escape, while liposomes benefit from high biocompatibility and surface functionalization for targeted delivery in cardiovascular diseases and other conditions [8].

Poly(Lactic-co-Glycolic Acid)-Resveratrol (PLGA-RES) nanocomposites represent another significant advancement, combining PLGA's biodegradability with the potent antioxidant properties of RES. This innovative approach helps combat oxidative stress during cryopreservation cycles, demonstrating significantly higher oocyte viability and maturation, thus overcoming a major challenge in reproductive medicine [8]. These engineered nanoscale biomaterials showcase the potential to protect against physicochemical damage at the cellular level under severe environmental conditions, expanding applications beyond traditional drug delivery into cellular preservation and regenerative medicine [8].

Advanced Delivery Systems for Complex Diseases

Innovative delivery systems with multiple functions have become key platforms for confronting complex diseases. A notable example includes motile hydrogel microrobots for osteosarcoma treatment via magnetically propelled methods [8]. Under an external magnetic field, these microrobots penetrate tumor sites to co-deliver therapeutic agents, with the hydrogel matrix providing sustained drug release favorable for higher drug retention at the target site. Preclinical studies have shown excellent antitumor activity in both 2D and 3D tumor models without significant toxicity to healthy tissues [8].

Electrospun nanofiber scaffolds represent another advanced platform for promoting diabetic wound healing, leveraging their high surface area, tunable porosity, and biocompatibility to serve as effective localized drug delivery systems and structural supports [8]. By incorporating various therapeutic agents, these scaffolds modulate inflammation and facilitate granulation tissue formation, addressing the impaired healing processes characteristic of diabetic pathophysiology. Similarly, exosome-based therapies have emerged as promising candidates for treating orthopedic degenerative diseases, facilitating cartilage and bone repair by delivering bioactive substances such as proteins and nucleic acids [8].

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Biomaterial Drug Delivery Systems

| Category | Specific Materials | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Polymers | Chitosan, Hyaluronic Acid | Thermoresponsive hydrogels, scaffolding | Biocompatibility, enzymatic degradation |

| Synthetic Polymers | PLGA, PVA-CMC, PEG | Nanoparticles, micelles, hydrogels | Controlled biodegradation, tunable properties |

| Lipid-Based Systems | Liposomes, Lipid Nanoparticles | mRNA/vaccine delivery, targeted therapy | Self-assembly, biomimetic properties |

| Inorganic Nanoparticles | Bioactive glass, Mesoporous silica, Calcium phosphate | Bone regeneration, controlled release | Mechanical strength, osseointegration |

| Stimuli-Responsive Materials | Rotaxanes, pH-sensitive polymers | Targeted drug release, smart delivery | Environmental responsiveness |

| Hybrid/Composite Materials | Polymer-ceramic composites, Hydrogel-ceramic blends | Multifunctional delivery systems | Combined mechanical/biological properties |

Micro Robotics and Digital Integration

Micro robotics represents a frontier innovation in drug delivery, utilizing tiny, soft robots that can navigate narrow spaces within the human body to dispense medicines with unprecedented precision. Recent developments include grain-sized soft robots controlled using magnetic fields that can transport up to four different drugs and release them in reprogrammable orders and doses [33]. These systems have demonstrated movement speeds of 0.30 mm to 16.5 mm per second in different body areas, with controlled movements continuing for up to 8 hours, offering remarkable potential for targeted combination therapy [33].