Biomaterial Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering: From Design Principles to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements in biomaterial scaffolds for tissue engineering, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Biomaterial Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering: From Design Principles to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements in biomaterial scaffolds for tissue engineering, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational design principles of ideal scaffolds, including biocompatibility, mechanical properties, and bioactivity. The review delves into methodological innovations across material classes and fabrication techniques like 3D bioprinting, examines key challenges and optimization strategies for immune response and mechanical performance, and discusses the role of AI and high-throughput technologies in validation and comparative analysis. By synthesizing current research and future directions, this article serves as a strategic resource for advancing regenerative medicine from the laboratory to the clinic.

Blueprint for Regeneration: Core Principles of an Ideal Biomaterial Scaffold

In the field of tissue engineering, biomaterial scaffolds serve as temporary three-dimensional (3D) structures that mimic the native extracellular matrix (ECM), providing mechanical support and biochemical cues that guide cellular behavior for tissue regeneration [1]. For these scaffolds to function successfully in a clinical setting, they must fulfill two foundational requirements: biocompatibility—the ability to perform with an appropriate host response without triggering deleterious effects—and biodegradability—the capacity to break down into non-toxic byproducts at a rate that matches new tissue formation [1] [2]. These intertwined properties are non-negotiable for the safe and effective integration of implants within the human body. Without them, scaffolds risk provoking severe immune responses, chronic inflammation, or mechanical failure, ultimately leading to device rejection and therapeutic failure. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of the principles, assessment methodologies, and material innovations defining these critical attributes, serving as a guide for researchers and drug development professionals working at the forefront of regenerative medicine.

Defining the Core Principles

Biocompatibility: Beyond Inertness

Modern interpretations of biocompatibility have evolved from the historical concept of material inertness. Today, it is understood as an active, favorable response where the material interacts with the host's biological system in a way that supports the intended function—be it promoting cell adhesion, proliferation, differentiation, or integration with surrounding native tissue [2]. A key metric of biocompatibility is the foreign body response (FBR), an immune-mediated reaction that begins with protein adsorption onto the implant surface, followed by acute and chronic inflammation, and potentially culminating in fibrosis and scar tissue formation [2]. Ideal biomaterials actively modulate this response to minimize FBR, thereby promoting integration and regeneration [2].

Biodegradability: Engineering Transience

Biodegradability refers to the controlled, predictable breakdown of a scaffold material into metabolic byproducts that the body can safely resorb or excrete. This process can occur through hydrolytic degradation (cleavage of chemical bonds by water) or enzymatic degradation (cleavage by specific enzymes present in bodily fluids) [1]. The degradation kinetics must be carefully tailored to the specific clinical application; the scaffold must maintain structural integrity long enough to support the developing tissue but subsequently degrade to avoid impeding further growth or creating long-term complications [1]. The degradation profile is thus not merely a property of disappearance but a critical design parameter that governs the success of the regeneration timeline.

Quantitative Assessment of Scaffold Properties

The evaluation of next-generation scaffolds yields critical quantitative data on their performance. The table below summarizes key findings from recent studies on composite and natural material-based scaffolds.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Representative Biomaterial Scaffolds

| Scaffold Material | Key Measured Property | Initial Value | Value After 8 Weeks | Experimental Model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNC-CS-AG-GT Hydrogel | Compressive Strength | ~68 MPa | ~25 MPa | In vitro SBF + Lysozyme | [1] |

| BNC-CS-AG-GT Hydrogel | Weight / Mass Loss | 0% (Baseline) | 54% reduction | In vitro SBF + Lysozyme | [1] |

| Ulva sp. Seaweed Cellulose | Thickness | 2.00 ± 0.06 mm | Remained Consistent | In vivo Rat Subcutaneous | [2] |

| Cladophora sp. Seaweed Cellulose | Thickness | 1.70 ± 0.05 mm | Remained Consistent | In vivo Rat Subcutaneous | [2] |

These quantitative metrics are essential for researchers to model and predict scaffold behavior. The steady decline in compressive strength and mass of the BNC-CS-AG-GT hydrogel indicates a controlled degradation profile suitable for applications like bone tissue engineering where gradual load transfer to new tissue is desired [1]. Conversely, the structural stability of the seaweed cellulose scaffolds over an eight-week period suggests their utility in applications requiring longer-term mechanical support [2].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following toolkit outlines critical reagents and materials used in the featured studies for fabricating and evaluating scaffold biocompatibility and biodegradation.

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials for Scaffold Evaluation

| Reagent / Material | Function & Role in Evaluation | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) | Mimics the ionic composition of human blood plasma for in vitro degradation studies. | Used to study hydrolytic degradation of BNC-CS-AG-GT hydrogels [1]. |

| Lysozyme | An enzyme present in human bodily fluids (e.g., tears, saliva) that enzymatically degrades specific polymers like Chitosan. | Added to SBF to simulate enzymatic, body-fluid-driven degradation [1]. |

| AlamarBlue Assay | A cell viability indicator that uses a redox reaction to measure cell proliferation and cytotoxicity. | Confirmed the non-toxicity of seaweed cellulose (SC) scaffolds in vitro [2]. |

| CaCl₂ (Calcium Chloride) | A cross-linking agent used to form stable, ionic-bridged hydrogel networks with polymers like Alginate. | Used to cross-link BNC-CS-AG-GT scaffolds post-fabrication [1]. |

| Matrigel | A tumor-derived extracellular matrix commonly used for organoid culture, but poses xenogeneic risks. | Discussed as a suboptimal control in liver organoid research, to be replaced by defined biomaterials [3]. |

Standardized Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and accurate comparison of data across studies, adherence to standardized experimental protocols is paramount. The following sections detail common methodologies for assessing biodegradation and biocompatibility.

In Vitro Biodegradation Protocol

This protocol assesses the degradation profile of scaffolds in a controlled, simulated physiological environment [1].

- Step 1: Scaffold Preparation. Fabricate scaffolds into standardized dimensions (e.g., 5mm diameter cylinders using a biopsy punch). Sterilize the scaffolds, typically via autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes [1].

- Step 2: SBF and Lysozyme Preparation. Prepare SBF solution with ions at physiological concentrations (NaCl, NaHCO₃, KCl, CaCl₂, etc.). Supplement the SBF with a defined concentration of lysozyme (e.g., consistent with levels found in human serum) to model enzymatic activity [1].

- Step 3: Incubation and Sampling. Immerse pre-weighed scaffolds in the SBF-lysozyme solution and incubate at 37°C under gentle agitation to simulate body temperature and fluid movement. The study duration should be relevant to the intended application (e.g., up to 8 weeks). Sample the solution at regular intervals [1].

- Step 4: Analysis.

- Mass Loss: At each time point, remove scaffolds, rinse, dry thoroughly, and weigh. Calculate percentage weight loss relative to the initial mass [1].

- Mechanical Properties: Measure compressive strength using a universal testing machine to track the loss of mechanical integrity over time [1].

- Solution Analysis: Analyze the incubation medium for soluble degradation products using assays like HPLC for sugar content and Bradford assay for protein content [1].

In Vitro Biocompatibility and Cytotoxicity Protocol (MC3T3-E1 Cell Line)

This protocol evaluates scaffold toxicity and its ability to support cell growth and function, using the osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cell line as an example [1].

- Step 1: Scaffold Sterilization and Pre-conditioning. Sterilize scaffolds (e.g., via ethanol immersion or UV irradiation) and equilibrate in cell culture medium.

- Step 2: Cell Seeding. Seed cells directly onto the surface of the scaffolds at a defined density. A control group is typically cultured on standard tissue culture plastic.

- Step 3: Cell Culture. Cultivate the cell-scaffold constructs in an appropriate osteogenic medium, changing the medium regularly. The culture period can extend several weeks to monitor long-term effects.

- Step 4: End-Point Analysis.

- Cell Viability/Cytotoxicity: Use assays like AlamarBlue to quantify metabolic activity as a proxy for cell viability and proliferation [2].

- Cell Differentiation: Measure specific differentiation markers. For osteogenesis, Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) activity is a key early marker [1].

- Cell Morphology and Adhesion: Use techniques like scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to visualize cell attachment and morphology on the scaffold surface.

- Mineralization: Assess matrix mineralization, a late-stage marker of osteogenic differentiation, using stains like Alizarin Red S [1].

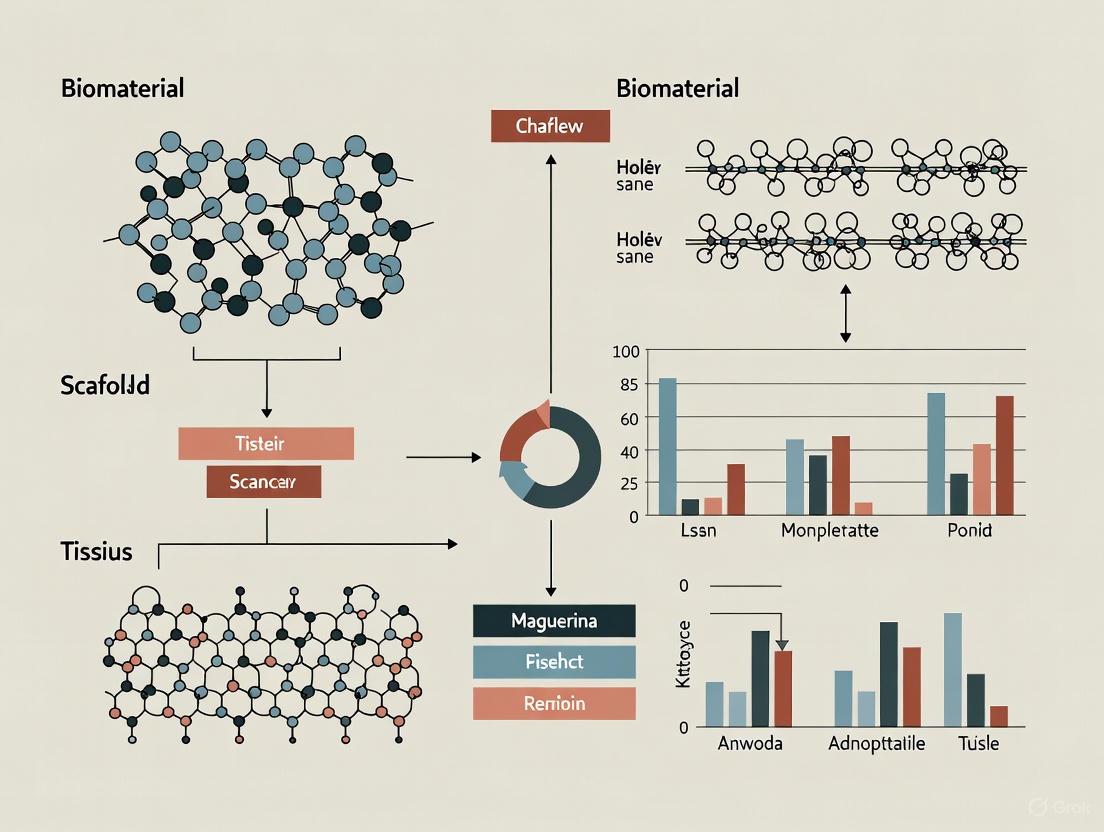

The experimental workflow for these assessments is visualized below.

Material Innovations and Case Studies

Composite Hydrogels: BNC-CS-AG-GT

Bacterial Nanocellulose (BNC) possesses excellent mechanical strength but suffers from limited innate biodegradability in the human body. To overcome this, a composite hydrogel integrating BNC with Chitosan (CS), Alginate (AG), and Gelatin (GT) was developed [1]. In this design:

- BNC provides the nanofibrillar structural reinforcement.

- CS enhances biodegradability (via lysozyme degradation) and introduces antibacterial properties.

- AG enables ionic cross-linking with Ca²⁺ for hydrogel stability.

- GT improves cell adhesion through its RGD peptide sequences [1].

This multi-material approach successfully created a scaffold with a compressive strength of ~68 MPa, which degraded gradually in SBF with lysozyme, losing 54% of its mass over 8 weeks while supporting osteoblast adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation without cytotoxicity [1].

Seaweed-Derived Cellulose Scaffolds

Seaweed cellulose (SC) presents a sustainable and lignin-free alternative to plant-derived cellulose, simplifying extraction [2]. Studies comparing SC from Ulva sp. (porous architecture) and Cladophora sp. (fibrous architecture) revealed how scaffold microstructure dictates the in vivo host response in a rat subcutaneous implantation model [2]:

- Ulva sp. (Porous): Promoted compartmentalized healing with distributed vascularized connective tissue.

- Cladophora sp. (Fibrous): Supported stratified tissue organization with aligned collagen deposition.

Both scaffolds showed minimal FBR, successful integration, and progressive vascularization over eight weeks, highlighting that biocompatibility is not only a chemical but also a structural property [2].

The distinct host responses elicited by different scaffold architectures are summarized below.

Biocompatibility and biodegradability are not standalone properties but are deeply interconnected, forming the non-negotiable foundation for the safe and successful integration of biomaterial scaffolds. As the field progresses, future work will focus on developing "smarter" biomaterials with precisely tunable degradation rates and bioactive surfaces that can actively direct cellular processes. The shift towards sustainable sources, such as seaweed-derived cellulose, further highlights the growing importance of eco-design in biomedical materials [2]. The ongoing challenge is to seamlessly integrate these advanced materials into complex, functional tissues, a goal that demands continued collaboration across materials science, cell biology, and clinical medicine.

In the field of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine (TERM), the ultimate goal is to develop biological substitutes that restore, maintain, or improve tissue function. Central to this endeavor is the design of biomaterial scaffolds that faithfully replicate the native tissue environment. The term "biomimicry" was first described by Otto Schmitt in 1957 and has since evolved to encompass various strategies for imitating nature's solutions [4]. In TERM, successful biomimicry requires a multifaceted approach that addresses three critical aspects: mechanical properties (matching tissue stiffness and strength), morphological properties (recreating architectural features), and biological properties (recreating the biochemical microenvironment) [4]. This technical guide focuses specifically on the mechanical and structural dimensions of biomimicry, examining how scaffolds can be engineered to withstand physiological loads while providing appropriate architectural cues that direct cellular behavior and tissue formation.

The consequences of failing to mimic native mechanical and structural properties can be severe. Mechanical mismatches between implants and native tissues often lead to graft failure, stress shielding, and improper mechanotransduction, where cells receive incorrect mechanical cues that steer them toward undesirable fates [4]. Similarly, inadequate structural design can inhibit cell infiltration, vascularization, and nutrient waste exchange, ultimately compromising tissue integration and regeneration. As such, a deep understanding of native tissue biomechanics and architecture provides the essential foundation for designing effective tissue engineering scaffolds.

Native Tissue Biomechanics: A Quantitative Framework for Biomimicry

Native tissues exhibit remarkable diversity in their mechanical properties, spanning several orders of magnitude in stiffness and strength. These properties are precisely tuned to withstand the specific physiological loads each tissue experiences daily. Table 1 summarizes the mechanical properties of key human tissues, providing critical target values for scaffold design.

Table 1: Mechanical Properties of Native Human Tissues

| Tissue Type | Elastic/Young's Modulus | Ultimate Tensile Strength | Key Mechanical Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical Bone | 19.3 GPa [4] | 50-150 MPa (highly variable) | High stiffness, compressive strength |

| Hyaline Cartilage | 0.2-0.8 MPa [5] | 4-40 MPa (region-dependent) | Compressive resilience, low friction |

| Meniscus | 0.182 MPa (bovine, compressive) [6] | Varies by direction | Anisotropic, tension-resistant |

| Skin | 0.1-16 kPa [4] | 5-30 MPa | Highly elastic, viscoelastic |

| Bladder | Variable | N/A | Dynamic, elastic |

These mechanical properties are not arbitrary; they play crucial roles in tissue development, homeostasis, and function. For example, the meniscus exhibits anisotropic mechanical behavior due to its specialized collagen architecture, with the equilibrium modulus significantly higher in the circumferential direction than in the radial direction [6]. This anisotropy enables the meniscus to effectively convert compressive tibiofemoral forces into tensile hoop stresses, which are efficiently managed by the circumferentially aligned collagen fibers. Similarly, bone's exceptional stiffness enables weight-bearing capabilities, while skin's elasticity allows for stretching and recovery. These structure-function relationships must guide the design of tissue-engineered constructs.

Experimental Methodologies for Characterizing Mechanical and Structural Properties

Rigorous characterization of both native tissues and engineered scaffolds is essential for effective biomimicry. The following experimental protocols provide standardized methodologies for assessing key mechanical and structural parameters.

Mechanical Testing Protocols

Uniaxial Tensile Testing:

- Purpose: To determine elastic modulus, ultimate tensile strength, and strain-to-failure of scaffold materials.

- Sample Preparation: Prepare rectangular specimens (e.g., 30mm × 10mm × thickness) according to ASTM D638. Hydrate samples in physiological solution for 24 hours prior to testing.

- Protocol: Mount samples in mechanical testing system with pneumatic or manual grips. Apply pre-load of 0.01N to ensure proper alignment. Conduct test at strain rate of 1% per minute until failure. Record force and displacement data at 100Hz sampling rate.

- Data Analysis: Calculate engineering stress (force/initial cross-sectional area) and engineering strain (change in length/original length). Determine elastic modulus from the linear region of the stress-strain curve (typically 0-10% strain).

Unconfined Compression Testing:

- Purpose: To evaluate compressive modulus and stress relaxation behavior, particularly for cartilaginous tissues.

- Sample Preparation: Prepare cylindrical specimens (e.g., 5mm diameter × 2mm height). Maintain hydration throughout preparation and testing.

- Protocol: Place sample between impermeable platens. Apply 5% strain at rate of 0.5% per second, then hold for 30 minutes to reach equilibrium. Record force data throughout.

- Data Analysis: Calculate equilibrium modulus from equilibrium stress divided by applied strain. Calculate stress relaxation percentage as (peak stress - equilibrium stress)/peak stress × 100%.

Structural Characterization Techniques

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) for Pore Architecture:

- Purpose: To visualize and quantify scaffold porosity, pore size, and interconnectivity.

- Sample Preparation: Dehydrate scaffolds through graded ethanol series (50%, 70%, 90%, 100%), critical point dry, and sputter-coat with gold/palladium.

- Protocol: Image samples at multiple magnifications (50X-5000X) under appropriate accelerating voltage (5-15kV). Capture images from at least three different regions per sample.

- Data Analysis: Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ) to measure pore size distribution, strut thickness, and porosity percentage. Calculate interconnectivity by analyzing pore throat sizes.

Histological Analysis for Tissue Integration:

- Purpose: To assess cell distribution, extracellular matrix production, and tissue-scaffold integration.

- Sample Preparation: Fix constructs in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours, dehydrate, and embed in paraffin. Section at 5-10μm thickness.

- Protocol: Deparaffinize and rehydrate sections. Perform staining (H&E for cell distribution, Safranin-O for proteoglycans, Masson's Trichrome for collagen). Image using brightfield microscopy.

- Data Analysis: Use established scoring systems (e.g., International Cartilage Repair Society grading system) for semi-quantitative assessment [5]. For quantitative analysis, measure staining intensity, cell number per area, and tissue infiltration depth.

Table 2: Advanced Characterization Techniques for Scaffold Evaluation

| Technique | Primary Application | Key Parameters Measured | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Micro-Computed Tomography (μCT) | 3D pore architecture | Porosity, pore size distribution, interconnectivity, scaffold degradation | Requires density contrast; may need staining for polymer scaffolds |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Nanoscale mechanical properties | Local stiffness, surface roughness, adhesion properties | Time-consuming; provides high spatial resolution |

| Confocal Microscopy | 3D cell distribution and viability | Cell infiltration, spatial organization, viability in thick constructs | Requires fluorescent labeling; limited penetration depth |

| Finite Element Analysis (FEA) | Computational modeling of mechanical behavior | Stress/strain distributions, prediction of failure points | Dependent on accurate material properties and boundary conditions |

Engineering Strategies for Mechanical and Structural Biomimicry

Material Selection and Composite Design

The choice of base material fundamentally influences scaffold mechanical properties. Synthetic polymers like poly(ε-caprolactone) [PCL] offer tunable degradation rates and high initial strength, making them suitable for load-bearing applications [4]. For example, PCL reinforced with Zein and gum Arabic in electrospun meshes achieved tensile strengths up to 2.9 MPa, appropriate for skin regeneration [4]. Natural polymers like collagen and elastin provide inherent bioactivity but often require reinforcement to achieve adequate mechanical properties. Janke et al. demonstrated that adding poly(L-lactide-co-ɛ-caprolactone) [PLCL] to collagen type I scaffolds increased ultimate tensile strength from 1.8 ± 0.8 kPa to 160 ± 20 kPa, achieving the J-shaped stress-strain curve characteristic of many native soft tissues [4].

Composite materials have emerged as particularly promising strategies for reconciling the often-conflicting demands of mechanical strength and bioactivity. For instance, hydroxyapatite (HA)/chitosan nanocomposites combine the osteoconductivity of HA with the processability of chitosan, creating scaffolds with enhanced compressive strength for bone tissue engineering [7]. Similarly, incorporating reduced graphene oxide (rGO) into polymer matrices can significantly improve electrical conductivity while maintaining mechanical integrity, which is crucial for engineering electrically responsive tissues like cardiac muscle [4].

Porosity Design and Architectural Control

Porosity represents a critical design parameter that simultaneously influences both mechanical and biological performance. An optimal pore architecture must balance sufficient porosity for cell infiltration and nutrient diffusion (typically >80% for many tissues) with preserved mechanical integrity [8]. Table 3 summarizes target pore sizes for various tissue engineering applications.

Table 3: Target Pore Sizes for Tissue-Specific Scaffold Design

| Tissue Type | Optimal Pore Size Range | Primary Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Bone | 200-350 μm [7] | Facilitates vascularization and osteoconduction |

| Cartilage | 100-200 μm | Supports chondrocyte migration and ECM production |

| Skin | 50-150 μm | Promotes fibroblast infiltration and keratinocyte migration |

| Nerve | 10-100 μm | Guides axonal extension and Schwann cell migration |

| Vascular | 50-200 μm (with hierarchical design) | Enables endothelialization and mechanical compliance |

Advanced manufacturing technologies now enable unprecedented control over pore architecture. 3D bioprinting allows for precise spatial patterning of multiple materials and cells, creating scaffolds with region-specific mechanical properties that mimic tissue interfaces like the osteochondral junction [8]. Freeze-drying (lyophilization) techniques can produce highly interconnected porous networks by controlling ice crystal formation during freezing; lower temperatures typically yield denser, more compact structures with smaller pores, while higher temperatures create larger, more open architectures [7]. Electrospinning generates nanofibrous scaffolds that closely mimic the native extracellular matrix's fibrous architecture, with fiber alignment providing contact guidance for cell orientation and tissue organization [6].

Convergence Strategies for Complex Tissue Mimicry

The most successful approaches for replicating complex tissues often combine multiple fabrication techniques. For the knee meniscus, which features circumferentially oriented collagen fibers (600nm diameter) interwoven with radial tie-fibers, convergent manufacturing strategies have shown particular promise [6]. For example, combining electrospinning to replicate the nanofibrous micro-architecture with 3D printing to create the macroscopic wedge-shaped structure enables better recapitulation of the meniscus's hierarchical organization. Similarly, decellularized ECM scaffolds preserve the native tissue's complex ultrastructure and biochemical composition while providing a biomechanically competent template for cell repopulation [6].

These convergent approaches acknowledge that tissues are not homogeneous but exhibit spatial variations in composition, architecture, and mechanical properties. The meniscus, for instance, demonstrates regional variations in proteoglycan content, with higher concentrations in the inner regions where compressive forces predominate [6]. Successfully mimicking such complexity requires designing scaffolds with graded mechanical properties and heterogeneous pore architectures that mirror this native spatial organization.

Computational Modeling in Scaffold Design

Computational approaches have become indispensable tools for optimizing scaffold design before fabrication. Finite Element Analysis (FEA) enables prediction of stress distributions throughout scaffold architectures under physiological loading conditions, identifying potential failure points and guiding structural reinforcement [8]. For example, FEA can model how different pore geometries (e.g., hexagonal vs. rectangular) influence stress concentration factors in bone scaffolds, enabling data-driven design decisions.

Modern modeling approaches also incorporate fluid-structure interactions to simulate nutrient transport and waste removal through porous networks, predicting regions potentially limited by diffusion constraints. These computational models can be coupled with cell behavior algorithms that predict how mechanical cues (substrate stiffness, fluid shear stress) influence cell migration, proliferation, and differentiation, creating comprehensive in silico testing platforms for scaffold optimization [8].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational-experimental workflow for scaffold design and validation:

Scaffold Design Workflow: This diagram illustrates the iterative process of designing and validating tissue engineering scaffolds, integrating computational modeling with experimental validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of the methodologies described in this guide requires specific reagents and equipment. The following table catalogues essential research tools for developing and characterizing biomimetic scaffolds.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Scaffold Development

| Category/Item | Specific Examples | Primary Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Base Polymers | Poly(ε-caprolactone) [PCL], Polylactic acid [PLA], Gelatin methacryloyl [GelMA], Collagen type I | Scaffold matrix material providing structural integrity and biocompatibility |

| Crosslinkers | 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide [EDAC], Genipin, Methacrylic anhydride | Enhance mechanical properties through chemical bonding of polymer chains |

| Bioactive Additives | Hydroxyapatite [HA], Bone morphogenetic protein-2 [BMP-2], RGD peptide, Reduced graphene oxide [rGO] | Enhance osteoconduction, specific differentiation, cell adhesion, or electrical conductivity |

| Characterization Reagents | Safranin-O, Hematoxylin & Eosin, Alcian blue, Alizarin red | Histological staining for proteoglycans, cell nuclei, glycosaminoglycans, and mineralization |

| Fabrication Equipment | 3D bioprinter, Electrospinning apparatus, Freeze-dryer | Scaffold fabrication with controlled architecture and porosity |

Mimicking the mechanical and structural properties of native tissue remains a fundamental challenge in tissue engineering, but continued advances in materials science, manufacturing technologies, and characterization methodologies are steadily closing the gap. The emerging paradigm recognizes that successful biomimicry requires integrated approaches that simultaneously address mechanical, structural, and biological cues in a spatially coordinated manner.

Future progress will likely be driven by several key developments. Stimuli-responsive biomaterials that dynamically alter their mechanical properties in response to physiological cues or external triggers could better mimic the adaptive nature of living tissues. Multi-material bioprinting technologies with increasingly fine resolution will enable more faithful replication of tissue interfaces and spatial heterogeneity. Advanced characterization techniques, particularly in vivo monitoring methods, will provide richer understanding of how scaffolds perform under physiological conditions. Finally, machine learning algorithms are poised to revolutionize scaffold design by identifying non-intuitive structure-property relationships and optimizing complex, multi-parameter design spaces [8].

As these technologies mature, the field moves closer to the ultimate goal of creating tissue-engineered constructs that seamlessly integrate with native tissues, providing functional restoration that persists for the long term. By maintaining a rigorous focus on mimicking both the mechanical and structural properties of native tissues, researchers can develop increasingly sophisticated solutions to the challenging problems of tissue loss and organ failure.

The field of tissue engineering has undergone a profound transformation, evolving from the development of passive, structural scaffolds to the engineering of sophisticated "smart" platforms that actively and precisely interface with biological systems to orchestrate therapeutic outcomes [9]. This evolution represents a fundamental paradigm shift, fueled by convergence of breakthroughs in materials science, immunology, and bioengineering. Where first-generation biomaterials were designed primarily for structural support with minimal biological interaction, contemporary approaches embrace bioactive and stimuli-responsive systems capable of dynamic biological regulation. This transition acknowledges the immune system not as an adversary to be evaded, but as a powerful biological system that can be rationally programmed and harnessed for therapeutic benefit, particularly through strategic manipulation of macrophage polarization and other immune mechanisms [9].

The "intelligence" ascribed to smart biomaterials is fundamentally rooted in their engineered capacity to sense specific alterations in their surrounding environment and respond to these changes in a predetermined, functional manner [9]. These advanced systems are transforming the landscape of tissue engineering by effectively addressing various regenerative clinical challenges across cardiology, orthopedics, and neural tissue regeneration [10]. By combining the advantageous properties of metals, polymers, and ceramics, hybrid scaffolds surpass limitations associated with single-material constructs, enabling advanced applications in biomimetics, wound healing, targeted drug delivery, and even tumor therapy [10]. This technical guide explores the fundamental principles, design considerations, and methodological approaches for incorporating bioactivity and smart functionality into biomaterial scaffolds for tissue engineering applications.

Classification and Evolution of Biomaterial Scaffolds

The classification of biomaterials reflects an increasing level of sophistication in their interaction with biological systems, essentially mirroring an evolution in their biomimetic capabilities [9]. This progression highlights a journey from static implants to dynamic, self-adaptive platforms, with each category representing distinct characteristics and functionalities.

Table 1: Classification Levels of Biomaterial Scaffolds

| Classification | Key Characteristics | Primary Functions | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inert Materials | Minimal biological interaction; designed primarily for structural support | Mechanical support; space occupation | Titanium alloys; inert ceramics; certain polymers [9] |

| Active Materials (Bioactive) | Elicit defined biological response at material-tissue interface | Release of pre-loaded bioactive agents; surface-mediated cellular interactions | Drug-eluting stents; antibiotic-loaded bone cements; hydroxyapatite coatings [9] |

| Responsive Materials | Sense and respond to specific environmental stimuli (pH, temperature, enzymes) | On-demand drug release; structural transformation in response to pathological cues | pH-sensitive hydrogels; temperature-responsive polymers like PNIPAM; enzyme-degradable matrices [9] |

| Autonomous Materials | Bi-directional responsiveness; sense, respond, and adapt based on feedback | Create adaptive, interactive systems that mimic homeostatic feedback loops | Materials that receive cellular feedback and remodel accordingly; 4D printed structures [9] |

The trajectory from inert to autonomous systems embodies the conceptual pivot in biomaterial design. While inert materials often trigger a foreign body response culminating in fibrous capsule formation, advanced smart materials aim to actively modulate this response, engaging with immune components like macrophages to skillfully guide their behavior toward pro-regenerative, anti-inflammatory phenotypes [9]. This strategic manipulation creates local microenvironments conducive to constructive tissue repair and functional restoration, rather than destructive inflammation or scarring.

Critical Design Parameters for Smart Scaffolds

Architectural and Biomechanical Considerations

The architectural design of scaffolds represents a critical determinant of their biological performance and integration with host tissues. Several key parameters must be optimized during the design process:

Porosity and Pore Size: Porosity significantly influences cell migration, nutrient diffusion, and vascularization. Optimal pore sizes vary by tissue type: typically 100-350μm for bone regeneration, 20-150μm for skin regeneration, and smaller dimensions for neural applications [10]. Interconnected pore networks are essential for uniform cell distribution and tissue formation.

Biomechanical Compatibility: Scaffolds must match the mechanical properties of native tissues to avoid stress shielding or mechanical failure. Critical parameters include compressive modulus (bone: 0.1-20 GPa; cartilage: 0.1-1 MPa), tensile strength, and fatigue resistance. Hybrid scaffolds combining metals, polymers, and ceramics offer enhanced mechanical integrity over single-material constructs [10].

Degradation Kinetics: The degradation rate should synchronize with tissue regeneration pace. Materials can be engineered with specific hydrolysis rates, enzymatic sensitivity, or responsive cleavage mechanisms. Monitoring includes mass loss over time (typically weeks to months) and molecular weight reduction [10].

Bioactivity and Signaling Incorporation

Bioactivity in scaffolds extends beyond basic structural support to encompass deliberate interactions with biological systems:

Chemical Bioactivity: Surface functionalization with specific peptide sequences (e.g., RGD for cell adhesion) or mineral components (e.g., hydroxyapatite for osteoconduction) enhances cellular interactions and tissue-specific differentiation.

Physical Bioactivity: Topographical features at micro- and nano-scales (grooves, pits, fibers) influence cell morphology, alignment, and gene expression through contact guidance mechanisms [10].

Biological Signaling: Controlled delivery of growth factors (BMP-2 for bone, VEGF for vasculature, NGF for nerves) at physiological concentrations (typically ng to μg per mg scaffold) directs cellular processes and tissue maturation.

Stimuli-Responsive Mechanisms in Smart Scaffolds

Stimuli-responsive biomaterials represent a cornerstone of smart functionality, enabling precise spatiotemporal control over scaffold behavior and therapeutic delivery. These systems exploit specific environmental triggers to initiate predetermined responses.

Table 2: Stimuli-Responsive Mechanisms in Smart Biomaterials

| Stimulus Type | Response Mechanism | Applications | Key Material Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH-Responsive | Ionizable groups protonate/deprotonate; pH-labile bonds cleave | Drug delivery in acidic tumor microenvironments (pH 6.5-6.9) or inflammatory sites | Polymers with carboxylic, amine groups; hydrazone, acetal, orthoester linkages [9] |

| Temperature-Responsive | Polymer chains undergo conformational changes at LCST/UCST | Injectable depot systems; thermally-activated drug release | Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM); Pluronics; chitosan/glycerophosphate [9] |

| Enzyme-Responsive | Specific enzyme recognition and cleavage of substrate motifs | Targeted drug release in disease sites with elevated enzyme expression (MMPs in cancer, chronic wounds) | Peptide-crosslinked hydrogels; hyaluronic acid-based systems [9] |

| Magnetic-Responsive | Particle alignment or heat generation under alternating magnetic fields | Remote-controlled drug release; hyperthermia therapy | Superparamagnetic Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles; paramagnetic MnOx composites [9] |

The development of multi-stimuli responsive systems represents a growing frontier in smart biomaterials. For instance, Chen et al. developed a triple-functional stimulus-responsive nanosystem based on superparamagnetic Fe₃O₄ and paramagnetic MnOx nanoparticles co-integrated onto exfoliated graphene oxide nanosheets using a novel double redox strategy [9]. This system achieved high drug loading capacity and pH-responsive drug release performance, demonstrating the potential of combinatorial approaches.

Diagram 1: Stimuli-Responsive Mechanism Workflow in Smart Biomaterials

Advanced Fabrication Technologies: 3D and 4D Bioprinting

The fabrication of complex, functional scaffolds has been revolutionized by additive manufacturing technologies. Three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting advances have enabled the creation of in vitro models for drug testing and therapeutic efficiency evaluation with unprecedented physiological relevance [10]. Key technological approaches include:

Extrusion-Based Bioprinting: Utilizes pneumatic or mechanical dispensing systems to deposit bioinks in layer-by-layer fashion. Optimal parameters include printing pressures (15-80 kPa), nozzle diameters (100-400μm), and printing speeds (5-20 mm/s) tailored to material viscosity and cell viability requirements.

Stereolithography (SLA): Employs UV light to photopolymerize liquid resins in precise patterns. Achieves high resolution (25-100μm) using photoinitiators (Irgacure 2959, LAP) at concentrations of 0.1-1.0% w/v with exposure times of 5-30 seconds per layer.

Digital Light Processing (DLP): Projects entire layers simultaneously for faster printing speeds. Utilizes similar photochemistry to SLA but with reduced printing times, though with potential trade-offs in resolution.

The emergence of 4D printing introduces the critical dimension of time, creating dynamic structures that evolve post-fabrication [10]. This is achieved primarily through shape memory polymers (SMPs) that can be programmed to undergo predictable morphological changes in response to specific stimuli. The 4D printing process involves: (1) Creating a 3D structure from SMPs or other responsive materials; (2) Programming the temporary shape through mechanical deformation above transition temperature; (3) Fixing the temporary shape by cooling below transition temperature; (4) Triggering shape recovery through application of stimulus (heat, light, solvent). This capability allows scaffolds to mimic the complex and dynamic properties of living tissues, responding to various physiological cues with precision timing [10].

Experimental Protocols for Smart Scaffold Evaluation

Protocol for Synthesis of pH-Responsive Hybrid Scaffold

This protocol describes the synthesis and characterization of a pH-responsive hybrid scaffold system for controlled drug delivery in wound healing applications, adapted from methodologies analyzed in the SMART Protocols guidelines [11].

Materials and Reagents:

- Alginate (high G-content, Sigma-Aldrich, Catalog #W201502)

- Gelatin Type A (300 Bloom, Sigma-Aldrich, Catalog #G2500)

- Chlorogenic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, Catalog #C3878)

- 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC, Thermo Fisher, Catalog #PG82079)

- N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS, Thermo Fisher, Catalog #24510)

- Calcium chloride dihydrate (CaCl₂·2H₂O, Sigma-Aldrich, Catalog #C7902)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, pH 7.4, Thermo Fisher, Catalog #BP24384)

- MES buffer (0.1 M, pH 6.0, Thermo Fisher, Catalog #BP30068)

- Deionized water (18.2 MΩ·cm resistivity)

Equipment:

- Syringe pump (Cole-Parmer, Model #78-0100C)

- Freeze dryer (VirTis, Model #GenesisSQ)

- UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Model #UV-2600)

- Scanning Electron Microscope (Hitachi, Model #SU3900)

- Mechanical tester (Instron, Model #5943)

Procedure:

Polymer Functionalization:

- Prepare 2% w/v alginate solution in MES buffer (0.1 M, pH 6.0)

- Dissolve chlorogenic acid (CA) in DMSO at 50 mg/mL

- Add EDC (20 mM final concentration) and NHS (10 mM final concentration) to alginate solution

- Add CA solution at 1:0.1 alginate:CA molar ratio

- React for 12 hours at room temperature with continuous stirring (200 rpm)

- Dialyze against deionized water for 48 hours (MWCO 12-14 kDa)

- Lyophilize for 72 hours to obtain CA-functionalized alginate

Scaffold Fabrication:

- Prepare 3% w/v solution of CA-alginate and 5% w/v gelatin in PBS at 60°C

- Mix polymers at 1:1 volume ratio with model drug (e.g., vancomycin at 2 mg/mL)

- Transfer to syringe and maintain at 37°C

- Extrude solution into CaCl₂ crosslinking bath (2% w/v) using syringe pump at 5 mL/h

- Maintain scaffolds in crosslinking solution for 24 hours at 4°C

- Rinse with PBS and store at 4°C until use

Characterization:

- Morphological Analysis: Image by SEM at 10 kV acceleration voltage after gold sputtering. Measure pore size using ImageJ software (n=50 measurements).

- Swelling Studies: Weigh dry scaffolds (Wd), incubate in PBS at pH 7.4 and 5.5 at 37°C. Remove at time points, blot excess liquid, weigh (Ww). Calculate swelling ratio as (Ww - Wd)/Wd.

- Drug Release: Place scaffolds in release medium (PBS, pH 7.4 or 5.5) at 37°C with shaking (50 rpm). Withdraw aliquots at predetermined times, analyze by HPLC or UV-Vis. Replace with fresh medium to maintain sink conditions.

Troubleshooting:

- Poor Crosslinking: Ensure CaCl₂ solution is freshly prepared. Increase crosslinking time to 36 hours.

- Irregular Pores: Optimize extrusion rate (3-7 mL/h range) and nozzle diameter (200-400μm).

- Incomplete Drug Release: Verify drug solubility and consider adding surfactants (0.1% Tween-80) to release medium.

Protocol for Evaluating Macrophage Polarization Response

This protocol assesses the immunomodulatory potential of smart scaffolds through macrophage polarization studies, critical for evaluating pro-regenerative microenvironment formation [9].

Materials and Reagents:

- RAW 264.7 macrophage cell line (ATCC, Catalog #TIB-71)

- DMEM culture medium (Thermo Fisher, Catalog #11995065)

- Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS, Thermo Fisher, Catalog #26140079)

- Penicillin-Streptomycin (Thermo Fisher, Catalog #15140122)

- Lipopolysaccharide (LPS, Sigma-Aldrich, Catalog #L4391)

- IL-4 (PeproTech, Catalog #214-14)

- IL-10 (PeproTech, Catalog #210-10)

- IFN-γ (PeproTech, Catalog #315-05)

- Antibodies for flow cytometry: CD86-FITC, CD206-PE, iNOS-APC

- RNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Catalog #74104)

- cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher, Catalog #4368813)

- qPCR reagents (Thermo Fisher, Catalog #4309155)

Procedure:

Scaffold Sterilization and Conditioning:

- Sterilize scaffolds (5mm diameter × 2mm thickness) in 70% ethanol for 30 minutes

- UV irradiate both sides for 15 minutes each

- Pre-condition in complete DMEM for 24 hours at 37°C

Cell Seeding and Culture:

- Seed RAW 264.7 cells at 1×10⁵ cells/scaffold in 48-well plates

- Allow attachment for 6 hours, then add fresh medium

- For polarization studies, after 24 hours, add:

- M1 polarization: LPS (100 ng/mL) + IFN-γ (20 ng/mL)

- M2 polarization: IL-4 (20 ng/mL) + IL-10 (20 ng/mL)

- Culture for 48 hours with treatments

Flow Cytometry Analysis:

- Harvest cells using gentle scraping

- Wash with PBS and stain with surface antibodies (CD86, CD206) for 30 minutes at 4°C

- For intracellular staining (iNOS), fix and permeabilize cells prior to antibody incubation

- Analyze using flow cytometer, collect 10,000 events per sample

- Calculate polarization ratios as (M2 markers)/(M1 markers)

Gene Expression Analysis:

- Extract total RNA using commercial kit

- Synthesize cDNA using 1μg RNA template

- Perform qPCR with primers for M1 markers (TNF-α, IL-1β, iNOS) and M2 markers (Arg-1, IL-10, TGF-β)

- Calculate relative expression using 2^(-ΔΔCt) method with GAPDH as reference

Statistical Analysis:

- Perform experiments in triplicate with three independent replicates (n=9)

- Analyze data using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test

- Consider p<0.05 statistically significant

- Report data as mean ± standard deviation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and evaluation of smart biomaterial scaffolds requires specialized reagents and materials with specific functional attributes. The following table catalogs essential components for research in this field.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Smart Biomaterial Development

| Reagent/Material | Function and Utility | Key Characteristics | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stimuli-Responsive Polymers | Provide sensing and response capabilities to environmental cues | Defined transition temperatures; specific cleavage sites; tunable sensitivity | PNIPAM (temperature); poly(β-amino esters) (pH); MMP-cleavable peptides (enzyme) [9] |

| Crosslinking Agents | Enable controlled scaffold formation and mechanical properties | Controlled reactivity; biocompatible byproducts; selective functionality | EDC/NHS (carboxyl-amine); genipin (natural alternative); glutaraldehyde (high efficiency) [11] |

| Bioactive Signaling Molecules | Direct cellular responses and tissue regeneration | Specific receptor binding; appropriate half-life; controlled release kinetics | Growth factors (BMP-2, VEGF, TGF-β); cytokines (IL-4, IL-10); chemokines [9] |

| Characterization Standards | Enable quantitative assessment of scaffold properties | Certified reference materials; standardized protocols; traceable values | GPC standards (molecular weight); NIST reference materials (mechanical properties) [11] |

| Cell Culture Assays | Evaluate biological responses to scaffold materials | Reproducible; quantitative; physiologically relevant | Macrophage polarization kits; metabolic activity assays (MTT, AlamarBlue); differentiation markers [9] |

Signaling Pathways in Smart Scaffold-Tissue Interactions

Smart biomaterials interact with biological systems through specific signaling pathways that ultimately dictate therapeutic outcomes. Understanding these pathways is essential for rational biomaterial design.

Diagram 2: Signaling Pathways in Smart Scaffold-Mediated Tissue Regeneration

The interaction between smart scaffolds and immune cells, particularly macrophages, creates a critical signaling network that determines regeneration success. Scaffold properties (physical cues, controlled drug release, surface topography, mechanical properties) directly influence macrophage polarization toward either pro-inflammatory M1 or pro-regenerative M2 phenotypes [9]. These phenotypes then activate specific signaling pathways: M1 macrophages typically activate NF-κB pathway promoting inflammation, while M2 macrophages preferentially activate STAT and TGF-β/Smad pathways associated with tissue repair [9]. The ultimate balance of these signaling cascades determines functional outcomes including angiogenesis, matrix deposition, and tissue remodeling.

The incorporation of bioactivity and smart functionality represents the frontier of biomaterial scaffold development, transforming passive frameworks into dynamic, regenerative environments. Advances in smart hybrid scaffolds are already revolutionizing approaches to drug delivery, wound healing, and tumor therapy, while 3D bioprinting technologies are producing increasingly sophisticated in vitro models for drug testing and therapeutic evaluation [10]. The strategic integration of stimuli-responsive mechanisms through 4D printing and shape memory polymers enables scaffolds to mimic the complex and dynamic properties of living tissues, responding to various physiological cues with unprecedented precision [10].

Future developments in this field point toward several transformative directions. Precision immune engineering will leverage increasingly sophisticated biomaterial systems to orchestrate specific immune responses tailored to individual patient needs and specific tissue contexts [9]. The integration of artificial intelligence-driven design approaches will accelerate the rational development of next-generation scaffolds, optimizing complex parameter combinations that would be impractical to explore through traditional experimental approaches alone [9]. Additionally, the convergence of biomaterial science with emerging technologies such as optogenetic control and multimodal therapeutic strategies will further blur the distinctions between medical devices and pharmacological interventions, creating truly integrated diagnostic-therapeutic systems.

As the field progresses, addressing challenges in biosafety, scalable manufacturing, and regulatory approval will be essential for successful clinical translation [9]. However, the continued evolution of smart biomaterials promises to pioneer new paradigms in precision immune engineering, offering transformative strategies for regenerative medicine and disease intervention that fundamentally exceed the capabilities of passive framework approaches.

The extracellular matrix (ECM) represents a highly sophisticated biological framework that transcends its conventional role as a passive structural scaffold [12]. Comprising a dynamic network of proteins, glycosaminoglycans, and signaling molecules, the ECM actively orchestrates fundamental cellular processes—including adhesion, migration, proliferation, and differentiation—through integrated biomechanical and biochemical cues [12]. This regulatory capacity arises from its tissue-specific composition and architecture, making it indispensable for physiological homeostasis and a critical blueprint for biomaterial design in regenerative medicine [12]. The rising global burden of chronic wounds, degenerative diseases, and organ failure has intensified the demand for advanced therapeutic strategies that address the limitations of conventional treatments [12]. While current biomaterials often fail to recapitulate the ECM's dynamic reciprocity with cells—leading to suboptimal outcomes such as fibrosis or functional deficits—recent innovations have yielded ECM-inspired platforms with enhanced biomimicry [12].

Central to the ECM's therapeutic relevance is its dual role in tissue repair: as a structural scaffold and a signaling hub. Following injury, it directs hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling by spatially coordinating cellular responses [12]. Key components like fibronectin and collagen engage integrin receptors, activating downstream pathways to drive migration while sequestered growth factors (e.g., TGF-β, PDGF) are released to modulate proliferation [12]. This synchronized regulation of adhesion, motility, and cell cycle progression creates an optimized microenvironment for regeneration [12]. Despite these advances, critical translational challenges persist. Gaps remain in understanding how engineered ECM analogs influence regenerative outcomes, particularly in mimicking dynamic remodeling [12]. Immune responses, mechanical mismatches, and inadequate vascularization further complicate clinical implementation [12]. This review systematically examines ECM biology and its biomaterial applications, analyzing: (i) structure-function relationships governing cell fate; (ii) molecular signaling mechanisms; (iii) comparative advantages of biomaterial classes; and (iv) strategies to overcome immunological, manufacturing, and regulatory barriers.

Fundamental ECM Biology and Composition

The ECM is a highly dynamic, three-dimensional network that provides not only structural support for tissues but also biochemical and mechanical cues essential for cellular function [13]. Composed of macromolecules such as collagens, glycosaminoglycans, elastin, and proteoglycans, the ECM regulates fundamental biological processes, including cell adhesion, migration, differentiation, and signal transduction [13]. The composition and mechanical properties of ECM show significant differences across tissue types, anatomical regions, and pathological states [13].

Table 1: Key ECM Components and Their Functions in Tissue Regeneration

| ECM Component | Primary Function | Role in Regeneration |

|---|---|---|

| Collagens (especially types I, II, III, IV, VI) | Provide tensile strength and structural integrity [13] | Type III to I transition enhances tissue strength; Type IV is crucial for basement membrane function [12] [14] |

| Elastin | Allows tissues to resume shape after stretching [13] | Provides resilience and stretch capacity to regenerating tissues [13] |

| Fibronectin | Mediates cell adhesion and migration [13] [14] | Forms provisional matrix after injury; regulates cell adhesion, differentiation, and communication [12] [14] |

| Laminin | Major component of basement membranes [14] | Promotes cell adhesion, differentiation, and angiogenesis; binds to integrins and other ECM components [14] |

| Proteoglycans/GAGs | Maintain structural properties and facilitate cell signaling [13] | Regulate water retention, growth factor binding, and cell signaling processes [13] |

The mechanical properties of the ECM—including stiffness, viscoelasticity, pore size, porosity, topology, and geometry—serve as key regulators of cellular behavior via mechanotransduction pathways [13]. Changes in ECM mechanics are frequently observed in pathological conditions, including cancer, fibrosis, and cardiovascular diseases, where dysregulated ECM remodeling promotes disease progression [13]. The aberrant stiffening of the ECM, for instance, enhances tumor invasion and fibrosis progression by altering cellular mechano-signaling [13].

Table 2: ECM Mechanical Properties Across Tissues and Pathological States

| Tissue/State | Stiffness/Mechanical Properties | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Brain Tissue | <2 kPa [13] | Soft environment suitable for neuronal function |

| Bone Tissue | 40–55 MPa [13] | Rigid structure providing mechanical support |

| Normal Breast Tissue | 0.167±0.031 kPa [13] | Physiological stiffness maintaining tissue homeostasis |

| Breast Cancer Tumor | 4.04±0.9 kPa [13] | Increased stiffness promoting malignancy and invasion |

| Pulmonary Fibrosis | 16.52 ± 2.25 kPa (5–10x increase) [13] | Progressive hardening driving disease progression |

Integrin-Mediated Signaling in Tissue Repair and Regeneration

Core Mechanisms of Integrin Signaling

Integrins serve as fundamental mediators of bidirectional communication between cells and their ECM microenvironment, playing indispensable roles in tissue repair and regeneration [12]. These transmembrane receptors, composed of α and β subunits, recognize specific ECM components including collagen, fibronectin, and laminin, thereby orchestrating essential cellular processes such as adhesion, migration, proliferation, and survival [12]. The dynamic interplay between integrins and their ECM ligands forms the molecular foundation for tissue regeneration, with distinct subunit combinations conferring specificity to these critical interactions [12].

The activation of integrin signaling initiates with ECM ligand binding, which induces conformational changes that promote receptor clustering and the assembly of focal adhesion complexes [12]. These specialized structures serve as mechanical and biochemical signaling hubs, recruiting adaptor proteins including talin, vinculin, and paxillin to bridge the connection between integrins and the actin cytoskeleton [12]. The formation of focal adhesions triggers the activation of multiple downstream signaling pathways that collectively coordinate the cellular response to tissue injury [12].

Central to this signaling network is the focal adhesion kinase (FAK) pathway, which, upon activation at Tyr397, recruits Src family kinases to regulate cytoskeletal dynamics and promote cell migration [12]. Parallel MAPK/ERK pathway activation regulates gene expression for proliferation and differentiation, while the PI3K/Akt pathway promotes cell survival in stressful, injured tissue microenvironments [12]. These interconnected pathways function synergistically to ensure appropriate cellular responses during the repair process [12].

Integrin Signaling in Mesenchymal Stem Cell Differentiation

The role of integrin signaling is particularly crucial in mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) differentiation, which is fundamental to tissue engineering strategies [15]. MSCs are multipotent stem cells with the ability to differentiate into various cell types, including adipocytes, chondrocytes, and osteoblasts [15]. The interaction of cell-ECM is mediated by integrins, which regulate cell adhesion, migration, and signaling, all of which are essential for tissue development and regeneration [15].

The activation of downstream pathways by integrin varies significantly across different MSC lineages [15]. In adipocytes, the interaction of ECM and integrin regulates adipogenesis through the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and inhibition of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) activity [15]. These activations reduce the expression of adipogenic markers such as AP2, AdipoQ, and CEBPα [15]. In chondrocytes, integrin receives signals from inflammation and produces inflammatory mediators (IL-1β and TNF-α) and matrix-degrading enzymes (MMP-3 and MMP-13), while the activation of MAPK-ERK is driven by Src, leading to chondrogenesis [15]. In osteoblasts, the activation of integrin induces both Wnt/β-catenin and FAK/ERK pathways activation, which in turn promote mineralization and osteogenic differentiation, respectively [15].

Dynamic ECM Remodeling in Wound Healing

ECM remodeling is a dynamic, tightly regulated process essential for wound healing, involving degradation of the provisional matrix and deposition of new ECM components critical for tissue restoration [12]. Shortly after injury, a fibrin-rich provisional matrix forms, offering structural support and enabling cellular infiltration that initiates repair [12]. This matrix also modulates the inflammatory response by recruiting fibroblasts and endothelial cells [12].

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) become pivotal during the remodeling phase by degrading the provisional matrix and facilitating fibroblast migration and ECM synthesis [12]. MMPs ensure a balanced transition from matrix degradation to new ECM formation, which is essential for effective healing [12]. A hallmark of this phase is the replacement of type III collagen with type I collagen, enhancing tissue tensile strength and restoring structural integrity [12]. Moreover, remodeling involves upregulation of matricellular proteins like fibronectin and tenascin-C, which modulate cell-ECM interactions and influence cell behavior, including adhesion, migration, and differentiation [12].

Precise regulation of ECM turnover is crucial; dysregulation can lead to pathological scarring, such as hypertrophic scars or keloids [12]. Overall, ECM remodeling supports both early repair and later tissue normalization through coordinated synthesis and degradation [12]. The dynamic process of ECM remodeling during wound healing highlights its key phases and components, illustrating the transition from provisional matrix formation to collagen maturation and tissue restoration [12].

ECM-Inspired Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering

Design Principles and Material Classes

ECM-inspired biomaterials have emerged as a significant advancement in the field of tissue engineering, presenting promising approaches for the repair and regeneration of damaged tissues [12]. These biomaterials are engineered to replicate both the structural and biochemical characteristics of the natural ECM, providing an optimal environment conducive to cellular activities critical for healing [12]. The inherent properties of the ECM are being investigated in efforts to develop scaffolds that promote cell attachment and proliferation while also enhancing the intricate processes of tissue repair and remodeling [12].

The design principles underlying ECM-inspired biomaterials focus on recapitulating key aspects of native ECM, including:

- Structural mimicry: Replicating the three-dimensional architecture of natural ECM [12]

- Biochemical signaling: Incorporating bioactive molecules that regulate cellular behavior [12]

- Mechanical compatibility: Matching tissue-specific mechanical properties [12]

- Dynamic remodeling: Enabling controlled degradation and neotissue formation [12]

Table 3: Classes of ECM-Inspired Biomaterials and Their Applications

| Biomaterial Class | Key Examples | Advantages | Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECM-based Scaffolds | Decellularized tissues, ECM hydrogels [12] [16] | Preserves native ECM composition and bioactivity [12] | Dermal regeneration, musculoskeletal repair [12] |

| Natural Biomaterials | Collagen, hyaluronic acid, fibrin [12] | Innate biocompatibility and bioactivity [12] | Wound healing, cartilage regeneration [12] |

| Synthetic Polymers | PLGA, PEG, PCL [12] | Tunable mechanical properties and degradation [12] | Bone tissue engineering, drug delivery [12] |

| Bioceramics | Hydroxyapatite, β-tricalcium phosphate [12] | Excellent osteoconductivity and mechanical strength [12] | Bone defect repair, dental applications [12] |

| Composite Materials | Polymer-ceramic blends, nano-reinforced composites [12] | Combines advantages of multiple material classes [12] | Osteochondral regeneration, vascular grafts [12] |

Advanced Fabrication Technologies

Innovations in decellularization, biofunctionalization, and advanced manufacturing are discussed as promising avenues to enhance biomimicry and therapeutic efficacy [12]. Furthermore, clinically approved ECM-derived products and the need for standardized protocols to bridge translational gaps are explored [12]. Key fabrication technologies include:

- 3D Bioprinting: Enables precise replication of the ECM's hierarchical architecture through layer-by-layer deposition of bioinks containing cells and biomaterials [12]

- Electrospinning: Creates nanofibrous scaffolds that mimic the fibrous structure of natural ECM [12] [17]

- Decellularization: Preserves the complex composition and ultrastructure of native ECM while removing cellular components [12] [16]

- Biofunctionalization: Enhances scaffolds with peptides, glycosaminoglycan mimetics, and nanostructured coatings [12]

Immune Response to ECM Bioscaffolds

The immune response to an implanted biomaterial is initiated by the inflammation caused by surgery itself [16]. The disruption of blood vessels, basement membranes, and tissues, in general, triggers coagulation cascade events, which result in the accumulation of platelets and leukocytes [16]. The contact of blood with the implanted biomaterial enables the adsorption of proteins such as albumin, immunoglobulins, and fibrinogen, which modulate the platelets' activation and coagulation events, therefore influencing the progression of the healing [16].

Unlike synthetic implants, which are often associated with chronic inflammation or fibrotic encapsulation, ECM bioscaffolds interact dynamically with host cells, promoting constructive tissue remodeling [16]. This effect is largely attributed to the preservation of structural and biochemical cues—such as degradation products and matrix-bound nanovesicles (MBV) [16]. These cues influence immune cell behavior and support the transition from inflammation to resolution and functional tissue regeneration [16]. However, the immunomodulatory properties of ECM bioscaffolds are dependent on the source tissue and, critically, on the methods used for decellularization [16]. Inadequate removal of cellular components or the presence of residual chemicals can shift the host response towards a pro-inflammatory, non-constructive phenotype, ultimately compromising therapeutic outcomes [16].

After the inflammatory response onset, innate immune cells interact with the implanted material through transmembrane receptors called integrins that activate metabolic pathways in response to mechanical and biochemical stimuli [16]. These metabolic pathways include cascade factors such as NF-κB, MAPK, TGF-β, JAK/STAT, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, and control the release of cytokines and growth factors that communicate and amplify the immune response at the local level [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for ECM and Integrin Signaling Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrin Ligands | RGD peptides, collagen-mimetic peptides, laminin-derived peptides [12] [14] | Biomaterial functionalization | Promote specific integrin binding and cell adhesion [12] |

| ECM Component Antibodies | Anti-collagen I, III, IV; anti-fibronectin; anti-laminin antibodies [14] | Immunohistochemistry, ELISA, Western blot | Detection and quantification of ECM proteins [14] |

| MMP Inhibitors/Assays | GM6001, MMP-2/9 inhibitor I, fluorescent MMP substrates [12] | Study of ECM remodeling | Modulation and measurement of protease activity [12] |

| Decellularization Reagents | SDS, Triton X-100, sodium deoxycholate, nucleases [12] [16] | Tissue decellularization | Removal of cellular content while preserving ECM structure [12] [16] |

| Mechanosensing Probes | YAP/TAZ antibodies, FRET-based tension sensors [13] | Mechanotransduction studies | Visualization of mechanical signaling pathways [13] |

Experimental Protocols for Critical Assessments

Protocol 1: Assessment of ECM Scaffold Immunomodulatory Properties

- Scaffold Preparation: Decellularize tissue using perfusion with 0.1% SDS followed by 1% Triton X-100, with nuclease treatment (50 U/mL DNase and RNase in PBS) for 3 hours at 37°C [16]

- Immune Cell Isolation: Isolate human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) using density gradient centrifugation [16]

- Co-culture Setup: Seed PBMCs on ECM scaffolds at density of 1×10^6 cells/cm² in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% FBS [16]

- Phenotype Analysis: After 72 hours, analyze macrophage polarization markers (CD86 for M1, CD206 for M2) using flow cytometry [16]

- Cytokine Profiling: Quantify cytokine secretion (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α for pro-inflammatory; IL-10, TGF-β for pro-remodeling) using multiplex ELISA [16]

Protocol 2: Evaluation of Integrin-Mediated MSC Differentiation

- Biomaterial Fabrication: Prepare RGD-functionalized hydrogels at varying stiffness (1-50 kPa) to mimic different tissue microenvironments [15]

- MSC Culture and Seeding: Culture human MSCs in growth medium and seed at passage 3-5 on functionalized surfaces at 10,000 cells/cm² [15]

- Osteogenic Differentiation: For osteogenesis, use medium supplemented with 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 μM ascorbate-2-phosphate, and 100 nM dexamethasone for 21 days [15]

- Adipogenic Differentiation: For adipogenesis, use medium with 1 μM dexamethasone, 0.5 mM IBMX, 10 μg/mL insulin, and 200 μM indomethacin for 14 days [15]

- Analysis: Quantify differentiation using Alizarin Red S staining (mineralization) for osteogenesis or Oil Red O staining (lipid accumulation) for adipogenesis [15]

The ECM represents a pivotal system that intricately influences cell behavior, tissue repair, and regeneration through a multitude of signaling pathways and interactions [14]. This review has underscored the importance of various matrix proteins, including collagens, fibronectin, laminin, and others, in mediating these processes [14]. The unique properties of each of these proteins enable them to play critical roles in wound healing, cell adhesion, differentiation, and communication [14].

By integrating emerging research with clinical perspectives, this review provides a roadmap for developing next-generation ECM-inspired biomaterials that address unmet needs in regenerative medicine, emphasizing interdisciplinary collaboration to optimize safety, functionality, and patient outcomes [12]. Future research directions should focus on:

- Advanced Biomimicry: Developing materials that better replicate the dynamic nature of ECM remodeling [12]

- Immunomodulation Strategies: Harnessing the immune-modulating properties of ECM for enhanced tissue integration [16]

- Personalized Approaches: Creating patient-specific scaffolds based on individual ECM profiles [13]

- Advanced Manufacturing: Utilizing 3D bioprinting and other technologies for complex tissue constructs [12]

- Standardization and Regulation: Establishing standardized protocols and regulatory frameworks for clinical translation [12]

The continued exploration of ECM biology and integrin signaling mechanisms will undoubtedly yield new insights and innovative solutions for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications. As our understanding of these complex systems deepens, so too will our ability to create increasingly sophisticated biomaterials that truly learn from nature's design principles.

Building Functional Tissues: Material Innovations and Fabrication Technologies

Natural polymers represent a cornerstone of modern tissue engineering, providing biomimetic scaffolds that closely resemble the native extracellular matrix (ECM). Among these, collagen, hyaluronic acid, chitosan, and silk fibroin have emerged as particularly promising materials due to their exceptional biocompatibility, tunable properties, and diverse biological functions. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of these four key natural polymers, focusing on their structural characteristics, biological mechanisms, and experimental applications in tissue engineering. By synthesizing current research findings and methodologies, this whitepaper aims to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the practical knowledge necessary to leverage these biomaterials for advanced therapeutic strategies. The content is framed within the broader context of biomaterial scaffold development, emphasizing the critical role of natural polymers in creating functional tissue constructs that support cell adhesion, proliferation, differentiation, and ultimately, tissue regeneration.

Polymer Profiles and Properties

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Key Natural Polymers

| Polymer | Chemical Structure | Primary Sources | Key Properties | Degradation Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen | Triple helix of polypeptide chains with [Gly-X-Y]ₙ repeats | Mammalian tissues (skin, tendon), marine organisms [18] | Excellent biocompatibility, low immunogenicity, biodegradability, hemostatic properties, mechanical strength [18] | Enzymatic degradation by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [18] |

| Hyaluronic Acid (HA) | Linear polysaccharide composed of D-glucuronic acid and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine [19] | Bacterial fermentation, rooster combs, vertebrate connective tissues [19] | Biocompatible, biodegradable, viscoelastic, CD44 receptor recognition, molecular weight-dependent bioactivity [19] [20] | Hyaluronidase-mediated degradation [19] |

| Chitosan | Linear polysaccharide of (β1→4) linked 2-amino-2-deoxy-d-glucose and N-acetyl-2-amino-2-deoxy-d-glucose [21] | Crustacean shells, insect cuticles, fungal cell walls [21] | Biocompatible, biodegradable, antimicrobial, hemostatic, pH-sensitive solubility [21] [22] | Enzymatic degradation by lysozyme and bacterial enzymes in colon [21] |

| Silk Fibroin (SF) | Protein with crystalline β-sheet domains surrounded by less organized regions [23] | Silkworms (Bombyx mori), spiders [22] | Excellent mechanical properties, biocompatible, biodegradable, versatile processability, tunable degradation [23] [22] | Proteolytic degradation; rate controlled by β-sheet content [23] |

Table 2: Mechanical and Functional Performance Metrics

| Polymer | Tensile Strength | Elongation at Break | Compressive Strength | Key Functional Advantages | Common Modifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen | Variable (source-dependent) | High elasticity in native forms | Enhanced in composite scaffolds [18] | Reconstructs ECM microenvironment, promotes cell adhesion, migration, proliferation, differentiation [18] | Cross-linking (EDC/NHS), polymer composite formation [24] |

| Hyaluronic Acid | Low (native form) | High (native form) | Low (native form) | Angiogenic potential, inflammation modulation, antibacterial, antioxidant functions [19] | Methacrylation, acrylation, norbornene, thiolation for cross-linking [20] |

| Chitosan | Moderate | Moderate to high | Moderate | Antimicrobial, mucoadhesive, hemostatic, can be functionalized via amino groups [21] [25] | Acylation, quaternization, carboxymethylation, thiolation [21] |

| Silk Fibroin | High (0.5-1.2 GPa) | High (10-30%) | Enhanced through β-sheet formation [23] | Superior mechanical strength, supports mesenchymal stem cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation [23] | Cross-linking, blending with other polymers, β-sheet content control [23] |

Cellular Interactions and Signaling Mechanisms

Collagen-Cell Interactions

Collagen regulates cellular behavior through specific receptor-mediated interactions. Integrins (α1β1, α2β1, α10β1, α11β1) and discoidin domain receptors (DDRs) serve as primary collagen receptors, recognizing specific triple-helical sequences within the collagen structure [18]. The GxOGEx' motif facilitates integrin binding, while DDR1 interacts with collagen types I, II, III, and IV, and DDR2 primarily binds collagen types I and III with high affinity for the GVMGFO motif [18]. These interactions trigger intracellular signaling cascades that direct fundamental cellular processes.

DDR1 binding to collagen activates the MAPK/ERK pathway, regulating immune cell migration, monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation, and secretion of chemotactic factors that enhance macrophage migration [18]. DDR2 activation primarily regulates MMP expression to mediate cell migration, inducing MMP-8 expression to degrade collagen networks and release chemotactic peptides that induce neutrophil chemotactic migration in 3D matrices [18]. Additionally, increased DDR2 expression enhances endogenous collagen synthesis, creating a positive feedback loop that promotes fibroblast proliferation and ECM remodeling through MMP-2 expression [18].

Beyond receptor-mediated signaling, collagen matrices provide physical guidance cues through haptotaxis (migration along adhesion gradients), durotaxis (migration along stiffness gradients), and contact guidance (migration along topological features) [18]. These mechanisms collectively enable collagen to orchestrate complex tissue regeneration processes by directing cell positioning, differentiation, and tissue assembly.

Hyaluronic Acid Molecular Weight-Specific Effects

Hyaluronic acid exhibits dichotomous biological effects directly correlated with its molecular weight. High molecular weight HA (>500 kDa) demonstrates immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory properties, while low molecular weight HA (<500 kDa) promotes pro-inflammatory phenotypes [20]. This size-dependent bioactivity significantly influences its application in tissue engineering, where specific inflammatory responses may be desirable or detrimental depending on the regeneration context.

HA interacts with cells primarily through CD44 and RHAMM (Receptor for Hyaluronan-Mediated Motility) receptors [19]. CD44, widely expressed on fibroblasts, blood cells, and cancer cells, regulates cell adhesion, migration, and proliferation. RHAMM promotes cell movement and focal adhesion turnover during migration and in response to cytokines [19]. These receptor interactions enable HA to directly influence cellular behavior and tissue organization.

The degradation products of HA further modulate biological responses. Oligosaccharides generated through hyaluronidase activity affect wound healing, angiogenesis, and immune reactions [19]. This degradation creates a dynamic feedback system where HA fragments can either promote or resolve inflammatory processes depending on their size, concentration, and temporal presentation during the healing cascade.

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Preparation of Carp Collagen Scaffolds for Guided Bone Regeneration