Beyond the Mesh: A Comprehensive Guide to Understanding, Managing, and Minimizing Discretization Error in Finite Element Biomechanics

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a systematic framework for addressing discretization error in finite element biomechanics.

Beyond the Mesh: A Comprehensive Guide to Understanding, Managing, and Minimizing Discretization Error in Finite Element Biomechanics

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a systematic framework for addressing discretization error in finite element biomechanics. We explore the fundamental sources of error, including geometric approximation and numerical integration, and their impact on predictions of stress, strain, and failure in biological tissues. Methodological strategies such as adaptive mesh refinement (h, p, and r-methods) and advanced element technologies are detailed. The guide further covers practical troubleshooting, error quantification techniques (e.g., a posteriori error estimation), and comparative validation against analytical solutions and experimental data. The goal is to equip practitioners with the knowledge to improve model reliability for applications in medical device design, surgical planning, and mechanobiology.

The Inevitable Approximation: Understanding the Core Sources of Discretization Error in Biomechanical Models

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Discretization Error Symptoms in Biomechanical Simulations

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check |

|---|---|---|

| Solution Oscillations ("Checkerboarding" stresses) | Inadequate element integration, overly coarse mesh for high stress gradients. | Run a patch test. Increase mesh density in high-strain regions and/or use higher-order elements. |

| Mesh Locking (Artificially stiff response) | Use of full-integration elements for incompressible/ nearly incompressible materials (e.g., soft tissue). | Switch to hybrid elements (u-P formulation) or use reduced integration with hourglass control. |

| Poor Stress/Strain Recovery | Discontinuous derivative fields at nodes; stress averaging errors. | Perform stress recovery at Gauss points. Use nodal averaging with caution and inspect convergence. |

| Lack of Convergence | Solution does not approach true value with mesh refinement. | Check model formulation (boundary conditions, material laws). Ensure error decreases monotonically with h- or p-refinement. |

| Volume Loss in Large Deformation | Excessive numerical damping, inaccurate integration in finite strain formulations. | Audit time-step size (for dynamics) and use appropriate finite strain measures (e.g., Neo-Hookean with proper volumetric term). |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do I know if my mesh is "fine enough" for my bone-implant interface simulation? A: Perform a mesh convergence study. Monitor a key output metric (e.g., peak von Mises stress at the interface) while systematically refining the mesh globally or in regions of interest. Convergence is typically achieved when the change in the metric between successive refinements is below a predetermined threshold (e.g., <2-5%). Document the final mesh density used.

Q2: What is the practical difference between h-refinement and p-refinement for modeling arterial wall mechanics? A: h-refinement subdivides existing elements (increases number of elements), effectively reducing element size (h). p-refinement increases the polynomial order of the shape functions within elements. For complex, nonlinear soft tissue, a combination (hp-refinement) is often most efficient: use h-refinement near geometric features and p-refinement in smooth, high-gradient regions.

Q3: My tumor growth model results vary drastically with different time-step sizes. How do I manage this temporal discretization error? A: You must conduct a time-step convergence study. Run your simulation with progressively smaller time steps (Δt, Δt/2, Δt/4...). Plot your outcome variable against time step size. The converged solution is approached as the curve asymptotes. Use the largest time step that remains within an acceptable error tolerance for computational efficiency.

Q4: Are there quantitative benchmarks for acceptable discretization error in biomechanics? A: While field-specific benchmarks exist (e.g., FEBio benchmark problems), acceptable error is problem-dependent. A common quantitative measure is the energy norm error or relative error in a primary variable. For peer-reviewed publication, demonstrating mesh and time-step independence through convergence studies is the standard practice.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Mesh Convergence Study for Stent Deployment in a Idealized Artery

- Geometry: Create a simplified cylindrical artery model with atherosclerotic plaque.

- Material: Assign hyperelastic (e.g., Ogden) models to artery/plaque and elasto-plastic model to stent.

- Mesh: Generate a sequence of 4-5 meshes with increasing global element density (e.g., 50%, 100%, 200%, 400% of baseline count).

- Analysis: Run identical stent expansion simulations for each mesh.

- Metric: Extract maximum principal stress in the plaque and lumen gain.

- Convergence Criterion: Refine until the change in maximum plaque stress is <3% between successive meshes.

Table 1: Sample Results from a Mesh Convergence Study

| Mesh ID | Elements (approx.) | Max Plaque Stress (MPa) | % Change from Previous | Lumen Gain (mm²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse | 25,000 | 0.85 | -- | 5.10 |

| Medium | 60,000 | 0.92 | 8.2% | 5.32 |

| Fine | 150,000 | 0.94 | 2.2% | 5.38 |

| Very Fine | 400,000 | 0.945 | 0.5% | 5.39 |

Protocol 2: Time-Step Independence Study for Knee Ligament Dynamics

- Model: Develop a finite element model of a knee joint under impact loading.

- Simulation: Perform an explicit dynamic analysis.

- Time-Steps: Run the simulation with time steps derived from the Courant condition: Δt, 0.8Δt, 0.5Δt, 0.2*Δt.

- Metric: Record the peak force in the Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL).

- Analysis: Plot peak ACL force vs. time-step size. Select a time step in the asymptotic region.

Visualizations

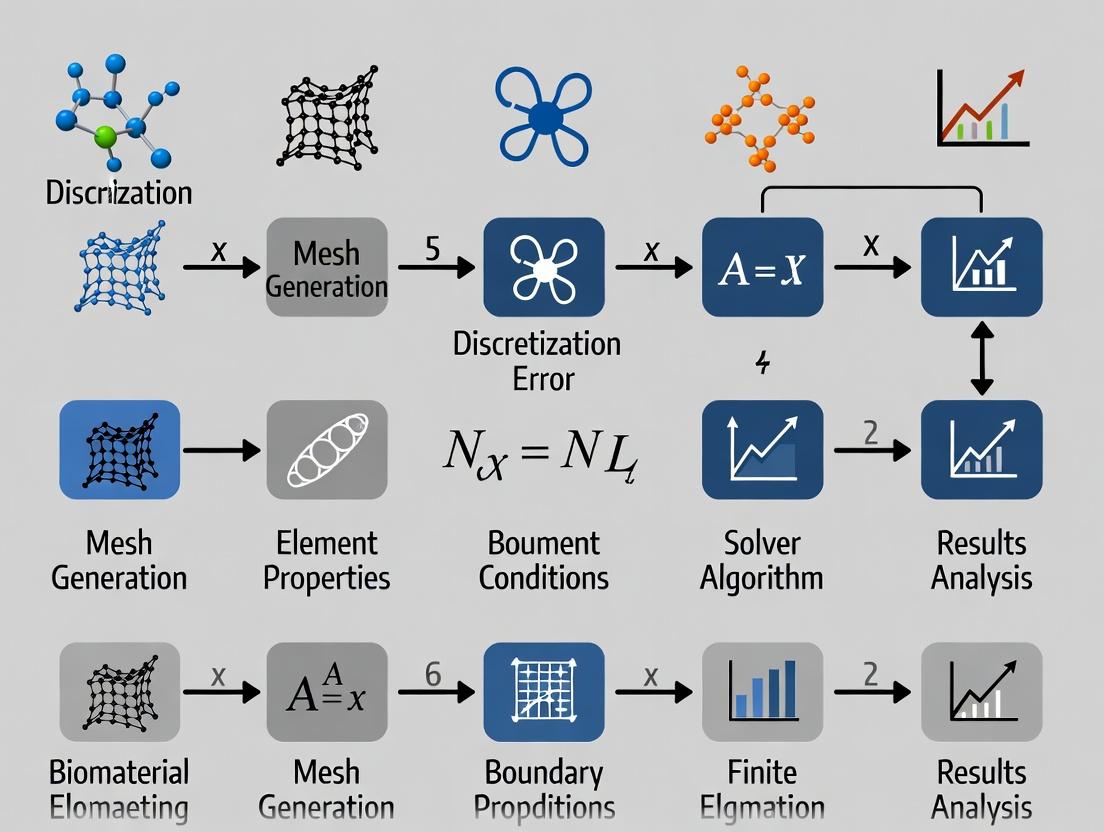

Title: The Origin of Discretization Error

Title: Discretization Error Troubleshooting Flow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Addressing Discretization Error |

|---|---|

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Enables computationally expensive convergence studies (fine meshes, small time steps) within feasible timeframes. |

| Adaptive Mesh Refinement (AMR) Software | Automatically refines the mesh in regions of high error during simulation, optimizing accuracy vs. computational cost. |

| Commercial FEA Solver with Verification Benchmarks (e.g., FEBio, Abaqus) | Provides robust, tested element libraries and solvers for nonlinear biomechanics, establishing a trusted baseline. |

| Scientific Python/Matlab Toolkits (e.g., FEniCS, SciPy) | Allows for custom implementation of novel elements or solvers to test specific discretization methods. |

| Reference Analytic/Numerical Benchmark Solutions | Serves as the "ground truth" for calculating the exact discretization error in simplified model problems. |

| Visualization & Post-Processing Suite (e.g., Paraview) | Critical for identifying spatial patterns of error, such as stress oscillations or localized deformation artifacts. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During finite element analysis (FEA) of a femur, my stress results show unrealistic, highly localized "hot spots" at the lesser trochanter. What is the likely cause and how can I resolve it? A: This is a classic symptom of geometric approximation error due to insufficient mesh refinement at complex curvatures. The lesser trochanter's sharp geometric feature is not captured by the element size, leading to artificially high stress concentrations.

- Solution: Implement a local mesh refinement protocol. Increase element density specifically around the trochanteric region. Use curvature-based mesh sizing algorithms available in most pre-processing software (e.g., ANSYS, Abaqus, FEBio). Validate by performing a mesh convergence study: sequentially refine the mesh and monitor the maximum principal stress at the hot spot until the change between simulations is <5%.

Q2: My simulation of arterial wall stress under hypertension is highly sensitive to the initial mesh generation seed, producing significantly different strain energy results. Why does this happen? A: This indicates that your mesh is likely under-resolved, and the solution has not converged. Complex, multi-branching vascular anatomy leads to non-unique, poor-quality tetrahedral elements (e.g., high aspect ratios, low dihedral angles) depending on the initial seed, especially with automated algorithms.

- Solution: First, enforce stricter mesh quality metrics. Set a minimum allowable dihedral angle >10° and a maximum aspect ratio <20. For critical regions, consider using structured or semi-structured hexahedral meshes, which are more robust but require more manual effort. Always report mesh quality metrics alongside your results.

Q3: When simulating soft tissue contact (e.g., cartilage-cartilage interaction), the solution fails to converge, or contact forces oscillate wildly. Could mesh geometry be a factor? A: Absolutely. Faceted ("stair-stepped") surfaces from coarse meshes create discontinuous surface normals, preventing stable contact detection and force transmission. This geometric error is severe in contact mechanics.

- Solution: Utilize surface smoothing or subdivision techniques to create a C1-continuous surface from the mesh before defining the contact pair. Increase the mesh density of the contacting surfaces and employ a finer integration scheme (e.g., more Gauss points) for contact elements. Verify that the initial distance between surfaces is greater than the geometric approximation error of the meshes.

Q4: How do I quantitatively report geometric discretization error in my manuscript, as it cannot be eliminated? A: Best practice is to perform and report a formal mesh convergence study for your key output metrics (e.g., peak stress, strain energy, displacement).

- Protocol:

- Generate at least 3-4 meshes with progressively increasing global element density (e.g., 2x, 4x elements).

- Run the identical simulation on each mesh.

- Plot your key metric against a measure of element size (e.g., mean edge length, number of degrees of freedom).

- Determine the point where the metric changes less than an acceptable tolerance (e.g., 2-5%). The mesh prior to this is your "converged" mesh.

- Report the results in a table and figure.

Table 1: Impact of Mesh Density on FEA Results for a Lumbar Vertebra

| Mesh Variant | Elements (Count) | Mean Element Size (mm) | Max. Principal Stress (MPa) | Comp. Runtime (min) | % Δ Stress from Finest Mesh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse | 45,200 | 2.5 | 84.7 | 12 | +18.5% |

| Medium | 187,500 | 1.2 | 73.2 | 47 | +2.5% |

| Fine (Ref) | 725,000 | 0.6 | 71.4 | 185 | 0.0% |

Table 2: Mesh Quality Metrics and Solution Stability

| Metric | Recommended Range | Poor Mesh Effect on Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Aspect Ratio | < 20 for 95% of elements | Increased interpolation error, stiffness matrix ill-conditioning. |

| Dihedral Angle (Tetra) | 10° < θ < 165° | Shear locking, poor convergence in plasticity/contact. |

| Jacobian Ratio | > 0.6 for all elements | Integration error, potential simulation failure. |

| Skewness | < 0.8 (0 is perfect) | Reduced accuracy, especially in transient dynamics. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Mesh Convergence Study for Biomechanical Structures

- Image Segmentation: Segment your anatomical geometry (e.g., from µCT/MRI) using validated software (Mimics, Simpleware) with consistent thresholding.

- Surface Generation: Generate a smooth, watertight surface (STL file). Apply conservative smoothing to reduce imaging noise while preserving anatomy.

- Mesh Generation Series: Using your FEA pre-processor (e.g., ANSYS ICEM, FEBioStudio), create a series of volumetric meshes:

- Start with a globally coarse mesh set by an absolute element size.

- Generate 3-4 subsequent meshes by reducing the global element size by a factor of ~1.5-2 each time.

- Apply local refinement at regions of interest (e.g., fillets, foramina, contact surfaces) based on curvature.

- Simulation: Apply identical material properties, boundary conditions, and loads to each mesh. Use the same solver settings.

- Analysis: Extract key quantitative outcomes (peak stress/strain, displacement, strain energy). Plot results vs. element size/number of nodes. Determine the convergence threshold.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Geometric Fidelity via Surface Distance Mapping

- Reference Surface: Obtain a high-resolution reference surface, either from an extremely fine (>>10M elements) computational mesh or a scanned physical model.

- Test Meshes: Generate the candidate meshes you wish to evaluate (e.g., standard tetrahedral vs. advanced hex-dominant).

- Distance Calculation: Use a tool like MeshLab or PyMesh to compute the Hausdorff distance or root-mean-square (RMS) distance from each test mesh to the reference surface.

- Visualization & Quantification: Map the distance error onto the test mesh surface as a color plot. Calculate the average and maximum distance error for quantitative comparison.

Visualizations

Title: Workflow Impact of Mesh Choice on FEA Results

Title: Consequences of Mesh Geometric Error in Biomechanics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Managing Geometric Discretization Error

| Item/Category | Example Software/Package | Primary Function in Addressing Geometric Error |

|---|---|---|

| Advanced Meshing Suite | ANSYS ICEM CFD, Simulia/ABAQUS CAE, FEBioStudio, MeshLab | Generate high-quality, geometry-conforming volume meshes (hexahedral, tetrahedral) with local refinement and smoothing controls. |

| Image-Based Modeling | Materialise Mimics, Synopsys Simpleware ScanIP, 3D Slicer | Convert medical images to accurate 3D surface models, enabling precise capture of anatomical geometry before meshing. |

| Mesh Quality Analyzer | Verdict Library (integrated), MeshLab, CGAL | Quantify element quality metrics (aspect ratio, skewness, Jacobian) to identify poorly shaped elements causing error. |

| Surface & Mesh Comparison | MeshLab, CloudCompare, Paraview | Compute Hausdorff distance between meshes to quantitatively assess geometric fidelity to a reference. |

| Automated Scripting | Python (with PyVista, GMSH API), MATLAB | Batch process mesh generation and convergence studies, ensuring reproducibility and systematic refinement. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Local clusters, Cloud computing (AWS, Azure) | Provide necessary computational power for running multiple high-resolution, converged mesh simulations. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Spurious Stress Oscillations at Material Boundaries Symptoms: Unphysical stress peaks or oscillations appear at interfaces between materials (e.g., bone-implant, soft tissue-hard tissue) in biomechanical models, even under smooth loading conditions. Diagnosis: This is often caused by the inability of standard C0-continuous shape functions (e.g., linear Lagrange) to accurately represent the kink (C1 discontinuity) in the strain field at a bi-material interface. The shape function over-smoothes the true solution. Solution Steps:

- Mesh Refinement: Locally refine the mesh around the interface. This reduces the interpolation error but increases computational cost.

- Higher-Order Elements: Switch to higher-order elements (e.g., quadratic) in the interface region. This improves gradient representation but may introduce other artifacts.

- Interface Elements: Implement specialized cohesive or interface elements with their own kinematic description.

- Gradient Recovery/Smoothing: Use a post-processing technique (e.g., Zienkiewicz-Zhu patch recovery) to compute smoothed, more accurate stress gradients.

Issue: Inaccurate Strain Gradient Prediction in Strain Gradient Elasticity Models Symptoms: When modeling small-scale biomechanical phenomena (e.g., cellular mechanics, bone lamellae behavior) using strain gradient theory, results are mesh-sensitive and fail to converge. Diagnosis: Strain gradient theories require the computation of second derivatives of displacement (strain gradients). Standard C0 shape functions have discontinuous first derivatives across element boundaries, making second derivatives unreliable or zero within elements. Solution Steps:

- C1-Continuous Elements: Utilize elements with inherently continuous first derivatives (e.g., Hermite, NURBS in isogeometric analysis). These are complex to implement.

- Mixed Formulations: Reformulate the problem using a mixed finite element method with independent interpolations for strain and strain gradients.

- Nonlocal Models: Consider integral-type nonlocal models that avoid the need for higher-order derivatives.

Issue: Volumetric Locking in Nearly Incompressible Soft Tissue Symptoms: Elements exhibit artificially stiff behavior when modeling nearly incompressible materials like muscle, cartilage, or intervertebral discs. Diagnosis: Standard displacement-based elements struggle to satisfy the incompressibility constraint, as low-order shape functions cannot simultaneously interpolate displacements and the hydrostatic pressure field accurately. This is a specific manifestation of interpolation error for the volumetric strain gradient. Solution Steps:

- Mixed u-p Formulations: Use elements with separate interpolations for displacement (u) and pressure (p), such as Taylor-Hood elements.

- Selective Reduced Integration: Use reduced integration for the volumetric stiffness term only.

- Enhanced Assumed Strain (EAS) Methods: Introduce additional strain modes to improve the element's response to incompressibility.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: I am using linear tetrahedral elements for a complex bone scaffold simulation. My stress results are very mesh-dependent. Should I just keep refining the mesh? A: While uniform h-refinement (making the mesh smaller everywhere) will eventually reduce error, it is computationally inefficient. For stress and strain gradients, consider:

- Local Refinement (h-adaptivity): Refine only in high-stress gradient regions.

- Element Order Increase (p-adaptivity): Switching to quadratic tetrahedra (p-refinement) in critical areas often provides a much greater accuracy gain per degree-of-freedom increase than simple h-refinement for smooth problems.

- Error Estimation: Use an a posteriori error estimator (e.g., based on stress discontinuity across elements) to guide where to refine.

Q2: How do shape function limitations directly impact drug development research in biomechanics? A: Inaccurate stress/strain gradients can mislead critical analyses:

- Mechanobiology: Incorrect gradients at a cell-scaffold interface can invalidate predictions of cell differentiation or migration driven by mechanical stimuli.

- Drug Delivery Device Design: Over- or under-estimated stress peaks in a biodegradable polymer implant can lead to faulty predictions of failure timing and drug release profiles.

- Bone Remodeling Simulations: Algorithms often use strain energy density (derived from stresses/strains) as a stimulus. Interpolation errors can corrupt the stimulus field, leading to non-physical predicted bone growth or resorption.

Q3: What is the most practical first step to diagnose interpolation error in my model? A: Perform a convergence study. Run your analysis with at least three systematically refined meshes (or increasing element orders). Plot your quantity of interest (e.g., max principal stress at a critical point) against mesh density. If the result does not approach a stable asymptotic value, your model is likely contaminated by significant discretization error, for which shape function limitations are a primary cause. Non-convergence is a clear diagnostic signal.

Q4: Are there modern FEM techniques that inherently reduce these interpolation errors? A: Yes. Isogeometric Analysis (IGA) uses NURBS or other smooth basis functions as shape functions. These offer higher-order continuity (C1, C2, etc.) across element boundaries, providing a more natural framework for approximating gradients and is particularly promising for strain gradient problems in biomechanics.

Table 1: Comparison of Element Performance for Gradient Quantities

| Element Type | Shape Function Order | Continuity (Displacement) | Continuity (Strain) | Suitable for Stress/Strain Gradients? | Common Use in Biomechanics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Tetrahedron (T4) | C0 Linear | C0 | Discontinuous | Poor | Initial meshing, large deformation contact |

| Quadratic Tetrahedron (T10) | C0 Quadratic | C0 | Discontinuous | Moderate (Better than T4) | General purpose, curved boundaries |

| Tri-linear Hexahedron (H8) | C0 Linear | C0 | Discontinuous | Poor | Simple soft tissue blocks |

| Tri-quadratic Hexahedron (H20) | C0 Quadratic | C0 | Discontinuous | Good | Accurate stress analysis |

| Hermite Hexahedron | C1 Cubic | C1 | Continuous | Excellent | Plate/shell models, strain gradient elasticity |

| NURBS (IGA) | Variable (k-refinement) | Cp-1 | Continuous | Excellent | Vascular stents, smooth tissues, phase-field fractures |

Table 2: Error Reduction Rates for Different Refinement Strategies

| Refinement Strategy | Theoretical Convergence Rate for Displacement | Theoretical Convergence Rate for Stress (Gradient) | Practical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| h-refinement (halving element size with linear elements) | O(h²) | O(h) | To halve the stress error, you must quarter the element size (8x elements in 3D). |

| p-refinement (increasing from linear to quadratic order) | O(hp+1) | O(hp) | Increasing p gives a faster error reduction for the same number of new DOFs if the solution is smooth. |

| hp-refinement (combined) | Exponential | Exponential | Optimal strategy: use h-refinement near singularities (cracks) and p-refinement in smooth regions. |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Interpolation Error in a Biphasic Tissue Model

Objective: To quantify the error in fluid pressure gradients within a finite element model of articular cartilage using linear vs. quadratic elements.

- Problem Definition: Create a simplified 2D axisymmetric model of an osteochondral plug under confined compression.

- Material Model: Assign a biphasic (solid-fluid) constitutive law to the cartilage region. Bone is modeled as linear elastic.

- Mesh Generation:

- Generate three meshes for linear quadrilateral elements (coarse, medium, fine).

- Generate three corresponding meshes (similar node count) using quadratic quadrilateral elements.

- Boundary Conditions: Apply a constant ramp displacement to the top surface. Allow fluid flow only at the free surface.

- Simulation: Run a transient consolidation analysis for all six models.

- Data Extraction: At a fixed time point, extract the fluid pressure gradient magnitude (||∇p||) along a vertical path through the cartilage depth.

- Reference Solution: Use the results from the finest quadratic mesh as the "reference" solution.

- Error Calculation: Compute the L2 norm of the error in the pressure gradient field for each model relative to the reference solution:

Error = √( ∫ (∇p_model - ∇p_ref)² dΩ ) - Analysis: Plot error vs. degrees of freedom for both element types. The steeper slope for quadratic elements demonstrates superior efficiency for capturing gradients.

Visualization: Workflow & Relationships

Title: Interpolation Error Impact & Mitigation Workflow

Title: Gradient Error Assessment Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Addressing Gradient Interpolation Error

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose | Example Software/Toolkit |

|---|---|---|

| A Posteriori Error Estimator | Automatically identifies regions of high discretization error (typically where stress jumps are large) to guide adaptive mesh refinement. | deal.II, libMesh, FEniCS, Abaqus (Z-Z estimator) |

| Isogeometric Analysis (IGA) Solver | Provides a framework using NURBS basis functions, offering higher-order continuity for more accurate gradient computation. | FEBio (IGA plug-in), GeoPDEs, Gismo, Analysa |

| Mixed Element Formulation Library | Enables the use of elements with independent fields (e.g., displacement-pressure, displacement-strain) to overcome locking and gradient issues. | FEniCS (UFL), MOOSE Framework, Code_Aster |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster Access | Enables practical use of hp-adaptivity and 3D high-fidelity models, which are computationally expensive. | Local university clusters, cloud HPC (AWS, Azure), commercial solvers with parallel processing. |

| Scientific Visualization Suite | Critical for inspecting and comparing gradient fields (vector plots, contours) to identify spurious oscillations. | ParaView, VisIt, MATLAB with FE post-processing. |

Troubleshooting & FAQs

Q1: Why does my FE model of tendon tissue show unrealistic stress concentrations at element boundaries when using reduced integration? A1: This is a classic symptom of hourglassing or zero-energy modes, common with 1-point Gauss quadrature in soft, nearly incompressible materials. The single integration point cannot adequately capture the stress gradients, leading to spurious deformation modes. Solution: Switch to a full or selective integration scheme (e.g., 2x2x2 for hexahedra) for stiffness calculations. Alternatively, implement an hourglass control algorithm to stabilize the simulation without significantly increasing computational cost.

Q2: How do I choose the optimal Gauss quadrature order for a hyperelastic material model (e.g., Ogden model)? A2: The required order depends on the polynomial degree of the stress-strain response. For standard Ogden models (N=3), numerical tests are essential. Perform a quadrature convergence study:

- Run your simulation with increasing quadrature points (e.g., from 2 to 6 points per direction).

- Plot a key output (e.g., max principal stress at a point) against the number of points.

- The "optimal" order is the point where the output change falls below your tolerance (e.g., 1%). For many soft tissues, 3rd or 4th order is often sufficient.

Q3: My simulation of arterial wall failure shows significant variation in predicted rupture location when I refine the mesh. Is this an integration error? A3: Yes, this can be linked to integration error interacting with material instability. Under-integration can artificially stiffen elements, shifting failure locations. Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Step 1: Ensure you are using a sufficiently high quadrature rule (see Q2).

- Step 2: Perform a mesh objectivity study: Refine the mesh globally while holding the integration order constant. The failure location should converge.

- Step 3: If instability persists, examine the strain state at the integration points. The use of a F-bar or average-strain method can help mitigate volumetric locking in incompressible materials, providing more reliable failure prediction.

Q4: What is the impact of Gauss quadrature on the computational cost of a large-scale organ model (e.g., liver)? A4: The cost scales linearly with the number of integration points per element. Doubling the points in 3D (e.g., from 1 to 8) roughly doubles the element stiffness calculation time. See the table below for a quantitative comparison.

Table 1: Cost-Accuracy Trade-off for 3D Hexahedral Elements

| Integration Scheme | Points per Element | Relative Assembly Time | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduced (1-point) | 1 | 1.0 (Baseline) | Fast, rough deformation; requires stabilization. |

| Full (Gauss) | 8 (2x2x2) | ~3.5 - 4.5 | Standard for nonlinear hyperelasticity. |

| High-Order (Gauss) | 27 (3x3x3) | ~10.0 - 12.0 | For high-order elements or complex material responses. |

Q5: How can I verify that my integration scheme is accurate for a user-defined material subroutine (UMAT)? A5: Implement a patch test. Create a small mesh of distorted elements and apply a uniform strain state (e.g., uniaxial stretch). The stress should be uniform at all integration points to within machine precision. A failed patch test indicates an error in either the constitutive model Jacobian or the integration mapping.

Experimental Protocol: Quadrature Convergence Study for a Biaxial Test Simulation

Objective: To determine the appropriate Gauss quadrature order for a planar biaxial test simulation of skin tissue modeled with a Holzapfel-Gasser-Ogden (HGO) constitutive law.

Materials & Software:

- Finite element software (e.g., Abaqus, FEBio, custom code).

- Scripting interface for automated parameter variation.

- HGO material parameters from published literature for human dermis.

Procedure:

- Model Setup: Create a square planar membrane mesh of quadrilateral elements. Apply biaxial displacement boundary conditions to replicate a standard biaxial test protocol (10% stretch).

- Parameter Sweep: Execute a series of simulations. In each run, change only the number of Gauss integration points in-plane (from 1x1 to 5x5). Maintain full integration through the thickness.

- Data Extraction: For each run, record the reaction force at the loaded edges and the maximum fiber-direction stress (σ₄₄) in the central element at the final strain.

- Convergence Analysis: Calculate the percentage difference in reaction force and σ₄₄ between successive quadrature orders. Define convergence when the difference is < 0.5%.

- Validation: Compare the converged stress field against an analytical solution for a simplified case (e.g., Neo-Hookean material under pure shear).

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Toolkit for FE Biomechanics Integration Studies

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Abaqus/Standard or FEBio | Industry-standard FE platforms with robust hyperelastic material libraries and explicit user control over element formulation and integration. |

| Python with SciPy/NumPy | For scripting automated convergence studies, post-processing results, and implementing custom quadrature rules or patch tests. |

| ParaView | Open-source visualization tool to critically examine field variables (stress, strain) at integration points, not just at nodes. |

| MATLAB or Octave | For rapid prototyping of constitutive models and calculating their theoretical polynomial order to inform quadrature choice. |

| Reference Analytic Solutions (e.g., Cook's membrane, 3D cantilever beam) | Benchmarks to verify that your model+integration combination solves basic continuum mechanics problems correctly. |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Workflow for Diagnosing Integration Error

Diagram 2: Integration Points & Error in an Element

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My simulation of myocardial contraction fails with excessive penetration errors when the ventricular walls contact. The error amplifies over time, causing the solution to diverge. What could be the cause and how can I resolve it?

A: This is a classic issue where material nonlinearity (the hyperelastic, anisotropic myocardium) interacts with contact constraints. The discretization error from the finite element formulation is amplified at the contact interface. To resolve:

- Refine the Mesh at Contact Interfaces: Implement local mesh refinement along the endocardial surfaces where contact is expected. This reduces geometric discretization error.

- Use a Softer Penalty Method or Augmented Lagrangian: Avoid overly stiff penalty parameters which can cause instability. Gradually increase the penalty parameter or use an augmented Lagrangian method for more stable enforcement.

- Verify Material Tangent Consistency: Ensure the consistent linearization (algorithmic tangent) of your constitutive model for cardiac tissue is perfectly accurate. An inconsistent tangent can cause quadratic convergence loss and error growth.

- Reduce Time Step: Use adaptive time stepping to decrease the step size automatically during the contact phase.

Q2: When simulating stent deployment in a calcified artery, the results show high sensitivity to mesh density and element type. How can I establish a mesh-independent reference solution?

A: The contact between the rigid, complex stent geometry and the brittle, nonlinear calcified plaque is highly stress-concentrated. Follow this protocol:

- Perform a Systematic Mesh Convergence Study: Run the simulation with at least 4 progressively finer global mesh densities. Use p-refinement (increasing element order) if possible.

- Extrapolate to Zero Element Size: Plot your Quantity of Interest (QoI), e.g., maximum plaque stress, against average element size (h). Use Richardson extrapolation to estimate the h=0 value.

- Use Adaptive Remeshing: Configure your solver to trigger remeshing based on contact pressure or stress gradient error estimators. This creates a solution-aware mesh.

Q3: In a synovial joint contact simulation, how do I choose between kinematic (node-to-surface) and penalty-based contact algorithms to minimize error?

A: The choice depends on your QoI and computational resources. See the comparison table below.

Table 1: Contact Algorithm Comparison for Physiological Soft Tissues

| Algorithm | Primary Use Case | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage | Recommended for |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinematic (Node-to-Surface) | Accurate stress/strain in the slave surface (e.g., cartilage). | Enforces contact constraints exactly (within numerical tolerance). | Can be computationally expensive; may cause "locking". | Stress analysis in a specific, deformable tissue layer. |

| Penalty Method | General contact, large sliding, complex geometries. | Robust, easier to implement, computationally efficient. | Allows for small penetrations; accuracy depends on penalty stiffness. | Global joint kinematics, pressure distribution studies. |

| Augmented Lagrangian | When penalty method penetrations are unacceptable. | Reduces penetration vs. penalty method without extreme stiffness. | Requires additional iterations for constraint convergence. | Most applications requiring a balance of accuracy and robustness. |

Q4: The constitutive model for liver tissue involves complex visco-hyperelasticity. How can I verify that my implementation is not introducing numerical dissipation that masks or distorts contact behavior?

A: Implement the following verification protocol:

- Run a Single-Element Test: Subject a single element to homogeneous strain paths (shear, compression) and compare the stress output with analytical results or a trusted reference code.

- Energy Balance Check: For a dynamic contact simulation (e.g., impact), monitor the total energy (strain + kinetic + dissipated). In a closed system (no external forces post-impact), the total energy should be non-increasing. A sharp increase indicates numerical instability; an unrealistic decrease indicates excessive algorithmic dissipation.

- Rate-Convergence Test: Run the simulation at multiple, progressively smaller time steps. The QoI (e.g., contact force peak) should converge to a stable value.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Mesh Convergence Study for Contact Stress Objective: To determine the mesh density required for a contact stress solution within 5% of the extrapolated continuum value.

- Geometry: Prepare your contact geometry (e.g., two articular cartilage surfaces).

- Meshing: Generate 4 distinct meshes with global element sizes reduced by a factor of ~1.5 each step (e.g., 1.0 mm, 0.67 mm, 0.45 mm, 0.3 mm).

- Simulation: Run an identical loading/unloading compression simulation for each mesh.

- Post-Processing: Extract the maximum contact pressure (

P_max) and the contact area at peak load for each mesh. - Analysis: Plot

P_maxvs. element size (h). Perform Richardson extrapolation using the two finest meshes to estimateP_maxat h=0. Calculate the relative error for each mesh against this extrapolated value.

Protocol 2: Verification of Consistent Linearization for a Nonlinear Material in Contact Objective: To confirm that the finite element solver achieves asymptotic quadratic convergence, ensuring minimal error propagation.

- Setup: Create a simple model where a block of your nonlinear material (e.g., aorta with Holzapfel-Gasser-Ogden model) contacts a rigid plane.

- Solver Monitoring: Activate the solver's detailed iteration output (Newton-Raphson residuals).

- Run a Static Step: Apply a displacement to induce large strain and contact.

- Data Collection: Record the normalized residual (e.g.,

R) for each iteration within the first critical load step. - Verification: Plot

log(R)vs. iteration number. A straight line with a slope of approximately 2 indicates quadratic convergence and correct tangent implementation. A slope of 1 indicates only linear convergence, signaling an error that will amplify.

Visualizations

Title: How Material & Contact Amplify Discretization Error

Title: Mesh Convergence Study Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Mitigating Nonlinear Contact Error

| Tool / "Reagent" | Function & Purpose | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Adaptive Mesh Refinement (AMR) | Dynamically refines the mesh in regions of high error (e.g., stress gradient, contact interface). | Crucial for managing computational cost while achieving accuracy in unknown contact zones. |

| Consistent Algorithmic Tangent | The exact linearization of the material model's stress update algorithm. | Required for quadratic convergence of Newton-Raphson solver. Must be derived and coded meticulously. |

| High-Order Finite Elements | Uses higher-order polynomial shape functions (e.g., quadratic, cubic) to reduce interpolation error. | p-refinement can be more efficient than h-refinement for smooth solutions. |

| Error Estimator | Quantifies the local numerical error in the solution field to guide AMR. | Can be based on stress recovery (Zienkiewicz-Zhu) or solution residuals. |

| Robust Contact Search | Algorithm that reliably detects which slave nodes interact with the master surface. | Uses techniques like bucket sorting. Failure causes non-physical penetrations or rejection. |

| Augmented Lagrangian Contact | A numerical method to enforce contact constraints with minimal penetration and stable numerics. | Prevents the "over-stiffness" of pure penalty methods which can destabilize nonlinear solvers. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: My simulation of a stent deployment shows unrealistic stress concentrations at the stent-strut junctions, which affects my fatigue life prediction. Could this be a discretization issue?

Answer: Yes, this is a classic symptom of under-resolved geometry. The sharp corners and complex curvature of stent struts require a sufficiently fine mesh to capture stress gradients accurately.

- Solution: Perform a mesh convergence study. Refine the mesh locally at the strut junctions and globally. Monitor the maximum principal stress at your regions of interest. The solution is considered converged when the change in stress value between successive refinements is below a pre-defined threshold (e.g., <2%). Use higher-order elements (e.g., quadratic tetrahedral) if available.

- Protocol for Mesh Convergence:

- Create an initial baseline mesh.

- Solve the simulation and record key outputs (e.g., max stress, strain energy).

- Systematically refine the mesh (e.g., reduce global element size by 25% or apply local refinement).

- Re-solve and record outputs.

- Repeat steps 3-4 until the relative change in outputs between two successive meshes is below your acceptance criterion.

- Use the second-to-last (converged) mesh for your final analysis.

FAQ 2: My finite element model of bone-implant micromotion yields different results when I switch from hexahedral to tetrahedral elements, leading to conflicting conclusions about osseointegration potential. Which result should I trust?

Answer: This discrepancy highlights element-type-dependent discretization error. Hexahedral elements often exhibit superior performance in contact and near-incompressibility scenarios but are difficult to apply to complex geometries. Tetrahedral elements are more versatile but can be too stiff (locking) if linear formulations are used.

- Solution: Do not trust a single model in isolation. For a given geometry, create the best possible mesh for both element types. For tetrahedra, always use quadratic (second-order) elements to mitigate volumetric locking. Perform a convergence study for each element type independently. The converged solutions from both high-quality meshes should be close. If a significant discrepancy remains, investigate the model's assumptions and material properties.

FAQ 3: In simulating soft tissue indentation for a drug delivery device, the force-displacement curve is highly sensitive to the mesh density in the contact region. How do I determine an acceptable mesh without excessive computational cost?

Answer: You need to balance accuracy and resources by employing adaptive or targeted refinement.

- Solution: Implement a multi-stage protocol. First, run a coarse-mesh simulation to identify the zone of maximum deformation and stress. Then, define a sub-domain encompassing this zone (e.g., the region 3x the indenter's radius). Re-mesh only this sub-domain with a fine mesh, while keeping a coarser mesh elsewhere. This "submodeling" or "zone-based refinement" approach ensures accuracy where it matters most while conserving elements.

FAQ 4: How can discretization error in calculating wall shear stress (WSS) in a coronary artery model lead to incorrect research conclusions about plaque rupture risk?

Answer: Low spatial resolution smooths out high WSS gradients, which are critical indicators. Under-resolved meshes near the vessel wall can underestimate peak WSS magnitude and misrepresent its spatial distribution. This may cause a high-risk plaque (with locally elevated WSS) to be misclassified as low-risk.

- Solution: Use boundary layer mesh inflation. Insert 5-10 prism layers with a high aspect ratio near the arterial wall. Ensure the height of the first layer is small enough to resolve the viscous sublayer (often requiring a dimensionless wall distance y+ < 1 for accurate WSS). A convergence study on WSS vector magnitude and direction is mandatory.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of Mesh Refinement on Key Outputs in a Vertebral Body Compression Simulation

| Mesh Density (Elements) | Max Principal Stress (MPa) | % Change from Previous | Compressive Stiffness (N/mm) | Compute Time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse (12,540) | 48.7 | -- | 1850 | 4 |

| Medium (58,920) | 62.3 | +27.9% | 2110 | 21 |

| Fine (254,800) | 67.1 | +7.7% | 2185 | 97 |

| Extra Fine (1.1M) | 67.9 | +1.2% | 2195 | 412 |

Conclusion: The solution converges between Fine and Extra Fine meshes. The Medium mesh, while faster, introduces a >7% error in critical stress.

Table 2: Discretization Error in Drug Eluting Stent Drug Concentration Analysis

| Analysis Type | Mesh Element Size at Coating (µm) | Peak Drug Concentration (µg/mm³) | Time to 50% Release (days) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse Mesh | 10.0 | 15.2 | 4.5 | Unrealistic, "blocky" concentration profile. |

| Recommended | 2.5 | 22.7 | 6.8 | Resolves coating thickness; converged solution. |

| Over-Resolved | 0.5 | 23.1 | 7.0 | <1% change from recommended; high computational cost. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Mesh Convergence Study for Implant Fatigue Analysis

- Geometry Preparation: Clean CAD geometry of the implant (e.g., orthopedic screw). Define key volumes for local refinement (thread roots, fillets).

- Baseline Mesh Generation: Generate an initial tetrahedral mesh with global element size set to 10% of the part's largest dimension.

- Simulation Setup: Apply boundary conditions (fixed distal end) and load (cyclic torque/bending moment at proximal end). Define steel alloy material model with cyclic plasticity.

- Solving & Data Extraction: Solve for stresses. Extract the 10 highest von Mises stress values from the implant body.

- Iterative Refinement: Refine the mesh globally by reducing element size by 30%. Apply local sizing in critical volumes at 50% of the global size. Repeat step 4.

- Convergence Criterion: Calculate the relative difference in the mean of the top 10 stress values between iterations. Stop when ∆ < 5% for three consecutive iterations. The final reported stress should be from the iteration prior to the last one.

Protocol: Boundary Layer Meshing for Arterial Wall Shear Stress (WSS) Accuracy

- Lumen Surface Extraction: From segmented medical imaging (CT/MRI), extract a smooth, watertight surface of the arterial lumen.

- Initial Surface Meshing: Create a surface mesh with triangle elements no larger than 10% of the vessel diameter.

- Inflation Layer Setup: Configure 7-10 inflation layers with a first layer height calculated to achieve y+ ≈ 1. Use a growth rate of 1.2.

- Volume Meshing: Fill the remaining core volume with tetrahedral elements.

- CFD Setup: Apply pulsatile velocity inlet, pressure outlet, and no-slip wall conditions. Use a transient solver.

- Verification: Post-process to confirm y+ values are near 1. Extract WSS at peak systole. Perform one level of global refinement and confirm WSS metrics change by <3%.

Mandatory Visualization

Title: Mesh Convergence Study Workflow

Title: How Discretization Error Propagates to Conclusions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Robust Finite Element Analysis in Biomechanics

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Commercial FEA Software (e.g., Abaqus, ANSYS, FEBio) | Provides robust solvers, element libraries, and contact algorithms specifically validated for nonlinear, large-strain biomechanics problems. |

| Open-Source Meshing Tools (e.g., Gmsh, MeshLab) | Allows for precise control over mesh generation parameters and scripting of automated convergence studies, independent of solver. |

| ISO/ASTM Standard Geometries (e.g., ASTM F2996-13) | Standardized test models (e.g., femoral stem, spinal rod) enable benchmarking of mesh and solver settings against community-agreed results. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster Access | Enables the practical execution of high-fidelity, converged mesh models and complex multiphysics simulations (e.g., fluid-structure interaction). |

| Python/Matlab Scripting | Critical for automating pre-processing, batch submission of convergence studies, and post-processing of results to calculate error metrics. |

| Experimental Validation Dataset (e.g., digital image correlation strain maps, cadaveric load-displacement) | Provides ground-truth data to quantify the total error in a simulation, helping to contextualize the contribution of discretization error. |

Strategies for Refinement: Proven Methodologies to Reduce and Control Mesh-Induced Error

Troubleshooting & FAQs

Q1: During h-refinement of a soft tissue model, my solver fails with a "Jacobian matrix is singular" error. What is the cause and solution? A: This commonly occurs when new nodes are inserted, creating elements with poor aspect ratios or near-zero volumes in complex geometries. Ensure your refinement criterion (e.g., gradient-based error estimator) is applied smoothly. Solution: Implement a "green refinement" step to handle hanging nodes properly. Check the mesh smoothing step post-refinement. In biomechanics, material incompressibility can exacerbate this; consider a mixed u-P formulation.

Q2: After p-refinement (increasing element order), my stress concentrations at bone-implant interfaces become less accurate. Why? A: This is likely Gibb's phenomenon (oscillations near discontinuities). Polynomial enrichment struggles with singularities. Solution: Switch to local h-refinement at the interface or use a combined hp-refinement strategy that geometrically grades elements toward the singularity.

Q3: My r-refinement (node relocation) for a growing tumor boundary causes mesh tangling. How can I prevent this? A: Tangling happens when node movement exceeds the element's deformation capacity. Solution: Implement a monitor function (e.g., based on stress error density) that controls movement velocity. Couple r-refinement with selective h-refinement in high-deformation zones. Use a robust spring analogy or Laplacian smoothing with quality constraints.

Q4: How do I choose between h-, p-, and r-refinement for a specific biomechanics problem? A: See the decision table below.

Q5: In dynamic simulation (e.g., heart cycle), adaptive remeshing causes loss of solution history variables (e.g., plastic strain). How to transfer data? A: This is a key challenge. Solution: Use a consistent projection method (L2 projection) to map state variables from the old to the new mesh. Validate by checking energy conservation before/after remeshing. For complex histories, consider the "superconvergent patch recovery" technique.

Quantitative Comparison of AMR Types

Table 1: Characteristics of AMR Methods for Biomechanics

| Aspect | h-refinement | p-refinement | r-refinement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Action | Splits existing elements into smaller ones. | Increases polynomial order of shape functions. | Relocates nodes; number & connectivity fixed. |

| Convergence Rate | Algebraic (e.g., O(h²) for linear elastostatics). | Exponential for smooth problems. | Depends on smoothness of mapping. |

| Best For | Singularities, sharp gradients, complex geometry. | Smooth solutions, wave propagation, high regularity. | Boundary evolution, large deformations. |

| Comp. Cost per Iter | High (remeshing, projection). | Low (same mesh). | Moderate (solving mesh motion PDE). |

| Data Transfer Need | High (between meshes). | None. | Moderate (interpolation). |

| Mesh Quality Concern | Hanging nodes, aspect ratio. | Conditioning of stiffness matrix. | Tangling, inversion. |

Experimental Protocols for Validating AMR in Biomechanics

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Discretization Error Reduction

- Objective: Quantify the efficacy of each AMR strategy in reducing error for a known solution.

- Method:

- Model Setup: Create a 2D finite element model of a linear elastic arterial wall with a predefined micro-calcification inclusion.

- Analytic Solution: Use a simplified Kirsch solution (stress around a hole in a plate) as a reference for the stress concentration.

- Uniform Refinement: Run simulations with globally uniform h-, p-, and r-refinement. Calculate the L2 norm of the stress error against the analytic solution for each refinement level.

- Adaptive Refinement: Implement an a posteriori error estimator (e.g., Zienkiewicz-Zhu) to guide local adaptive refinement for each method.

- Comparison: Plot error vs. degrees of freedom (DoF) for all six cases. The most efficient method yields the steepest error reduction curve.

Protocol 2: Dynamic Simulation of Ventricular Filling

- Objective: Assess stability and conservation properties of AMR during a transient, large-deformation problem.

- Method:

- Model: Construct a 3D anisotropic hyperelastic model of a left ventricle.

- Loading: Apply a time-varying pressure load to simulate diastolic filling.

- Adaptive Strategy: Trigger h- or r-refinement based on the gradient of strain energy density at each time step.

- Metrics: Monitor total mass, volume, and global energy balance before and after each remeshing event. A reliable data transfer scheme will keep drift below 0.1%.

- Validation: Compare end-diastolic strain fields with MRI-derived measurements from an in-vitro phantom.

Diagrams

Title: AMR Method Selection Workflow

Title: Adaptive Mesh Refinement Loop

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for an AMR Experiment in Computational Biomechanics

| Item / Software | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| FE Solver with AMR API (e.g., FEniCS, deal.II, LibMesh) | Provides core finite element infrastructure and routines for local mesh modification, error estimation, and data projection. |

| A Posteriori Error Estimator (e.g., Zienkiewicz-Zhu, Dual Weighted Residual) | Quantifies local solution error to guide where refinement is needed. Critical for automation. |

| Biomechanical Constitutive Model Library (e.g., Holzapfel-Ogden, Neo-Hookean) | Defines the material behavior of tissues (arteries, myocardium, bone). Accuracy is key for error analysis. |

| Mesh Quality Metrics Tool (e.g, Aspect Ratio, Jacobian, Skewness) | Monitors and constraints mesh quality during refinement to prevent solver failure. |

| Data Projection/Transfer Algorithm (e.g., L2 Projection, Superconvergent Patch Recovery) | Maps history variables (stress, strain, damage) between meshes during refinement, ensuring solution continuity. |

| Visualization & Validation Suite (e.g., Paraview with quantitative comparison plugins) | Compares refined solutions against benchmarks or experimental data to validate error reduction. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: In my FE model of a femur, I'm observing unrealistic stress concentrations at the bone surface, even after mesh refinement. Is this a discretization error related to element choice? A1: Yes, this is a classic symptom of using linear tetrahedral elements for modeling complex geometries and stress gradients. Linear elements are often overly stiff (known as volumetric locking or shear locking) and can produce spurious stress concentrations, especially in bending-dominated scenarios like bone. For cortical bone, which experiences high stress gradients, switch to quadratic tetrahedral elements. These elements better approximate curved geometries and complex stress fields, significantly reducing this specific discretization error. Ensure your material model (e.g., anisotropic elasticity for bone) is correctly implemented for the quadratic shape functions.

Q2: When simulating large deformation of liver tissue, my model with quadratic hexahedral elements fails to converge. What could be the issue? A2: This often stems from element distortion during large deformations. While quadratic elements are generally more accurate, 20-node hexahedra (quadratic bricks) can be susceptible to severe distortion under large strains, causing Jacobian determinants to become negative and solver failure. Consider these steps:

- Switch to a mixed formulation (u-P) element designed for incompressible or nearly incompressible materials like soft tissues. This prevents volumetric locking.

- Use quadratic tetrahedral elements (10-node) with a robust mesh quality check. They can handle large distortions better than quadratic hexahedra in some cases.

- Implement an adaptive remeshing protocol if distortions exceed a critical threshold.

Q3: How do I quantitatively decide between linear and quadratic elements for a new composite model of osteochondral tissue? A3: Perform a convergence analysis for your specific output of interest (e.g., peak von Mises stress in subchondral bone, or maximum principal strain in cartilage). Follow this protocol:

Protocol: Mesh Convergence Analysis

- Create a series of at least 4 meshes with increasing density (element count) for both linear and quadratic element types.

- Run the same simulation (e.g., gait loading) on all meshes.

- Plot your output metric against a measure of mesh size (e.g., (1/√(number of elements))).

- Identify the point where the output change between successive meshes is less than a predefined tolerance (e.g., 2-5%). The element type that reaches this asymptotic value with fewer degrees of freedom (DOF) and lower computational cost is optimal for your study.

Table 1: Qualitative Comparison of Linear vs. Quadratic Elements

| Feature | Linear Elements (e.g., 4-node tetra, 8-node brick) | Quadratic Elements (e.g., 10-node tetra, 20-node brick) |

|---|---|---|

| Geometry Approximation | Poor for curved surfaces; requires finer mesh. | Excellent for curved surfaces; coarser mesh may suffice. |

| Stress/Strain Field | Constant strain within element; prone to inaccuracies in gradients. | Linear strain variation; more accurate for stress concentrations. |

| Computational Cost | Lower per element, but often requires more elements. | Higher per element (more nodes/DOF), but may require far fewer elements. |

| Locking Issues | Prone to shear and volumetric locking, especially for incompressible tissues. | Less prone to locking; often superior for incompressible/ bending problems. |

| Recommended Use | Preliminary studies, simple geometries, where strain gradients are low. | Final analyses, complex geometries (bone), incompressible materials (soft tissue), bending, stress concentration regions. |

Q4: My simulation of a stent expanding in a calcified artery is computationally prohibitive with quadratic elements. Any advice? A4: For multi-scale or contact-intensive problems, a mixed-element strategy is effective. Use quadratic elements only in critical regions (e.g., the calcified plaque-bone interface and stent contact points) and linear elements elsewhere. Ensure proper mesh compatibility at the interfaces. This hybrid approach balances accuracy and computational efficiency, directly addressing discretization error where it matters most.

Table 2: Convergence Analysis Results for a Tibial Bone Model Under Axial Load

| Element Type | Mesh Size (mm) | No. of Elements | Peak Stress (MPa) | % Change from Previous | Solve Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Tetra | 3.0 | 12,450 | 154.7 | -- | 45 |

| Linear Tetra | 1.5 | 98,760 | 178.3 | 15.2% | 320 |

| Linear Tetra | 1.0 | 335,000 | 189.5 | 6.3% | 1,450 |

| Quadratic Tetra | 3.0 | 12,450 | 192.1 | -- | 180 |

| Quadratic Tetra | 1.5 | 98,760 | 194.8 | 1.4% | 1,105 |

| Quadratic Tetra | 1.0 | 335,000 | 195.2 | 0.2% | 4,892 |

Note: The quadratic elements converge to a stable stress value (~195 MPa) with a coarse mesh, while linear elements show significant variation and have not yet converged at 1.0 mm mesh size.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Validating FE Models in Biomechanics

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Digital Image Correlation (DIC) System | Provides full-field, non-contact experimental strain measurements on tissue surfaces to validate FE model strain predictions. |

| Micro-CT Scanner | Generates high-resolution 3D geometry of bone or tissue scaffolds for creating anatomically accurate FE meshes. |

| Biaxial/Triaxial Mechanical Tester | Characterizes the anisotropic, non-linear material properties of soft tissues (e.g., skin, myocardium) for constitutive model fitting. |

| Polyurethane Foam Phantoms | Manufactured test blocks with known, homogeneous mechanical properties used as benchmarks to isolate discretization error from material model error. |

| Strain Gauges | Provides precise, point-based strain validation data at critical locations on synthetic or ex-vivo tissue samples. |

Visualization: Element Selection & Error Assessment Workflow

Title: Decision Workflow for Linear vs Quadratic Elements

Title: Discretization Error Sources & Element Impact

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My simulation exhibits volumetric locking when modeling nearly incompressible soft tissue. Which element formulation should I use and how do I implement it? A: Volumetric locking is a common issue with standard displacement-based elements. Implement a Hybrid (Mixed) Formulation.

- Root Cause: Standard elements cannot satisfy the incompressibility constraint (J=1) without producing spurious stresses.

- Solution: Use a hybrid element that treats pressure (p) as an independent, interpolated variable, separate from displacement. This decouples the volumetric and deviatoric responses.

- Protocol:

- Add pressure degrees of freedom to your element.

- Select a stable displacement-pressure interpolation pair (e.g., Q2/P1 for hexahedra, Taylor-Hood elements).

- Reformulate your hyperelastic constitutive law (e.g., Neo-Hookean) to use the deviatoric part of the deformation gradient, with pressure contributing to the volumetric stress.

- Solve the coupled displacement-pressure system using a mixed variational principle.

Q2: During large deformation analysis of a muscle group, my simulation crashes due to severe element distortion. What are my options? A: This indicates a mesh distortion failure. Consider switching to a Unified (or Polygonal) Element Formulation.

- Root Cause: Low-order simplex elements (e.g., linear tetrahedra) perform poorly in large strain, suffering from hourglassing and sensitivity to distortion.

- Solution: Use elements with higher nodal counts or natural strain formulations.

- Unified Formulation: Utilizes a single mathematical framework for different element shapes (tri, quad, tet, hex). Look for "Solid-Shell" or "3D continuum" elements that are tolerant to in-plane bending and thickness stretch.

- Polygonal Elements: Use Voronoi-based elements with many nodes per face. They are more resistant to distortion and provide a better approximation of strain fields.

- Protocol for Polygonal Meshes:

- Generate a polygonal mesh from your geometry using Voronoi tessellation.

- Employ "Mean Value Coordinates" or "Wachspress Coordinates" as shape functions to ensure consistency and linear completeness.

- Integrate the weak form using sub-cell quadrature (dividing each polygon into triangles for integration).

- Proceed with your standard non-linear solver (Newton-Raphson).

Q3: How do I choose between Hybrid, Unified, and Polygonal elements for my specific biomechanics problem? A: The choice depends on the material behavior and deformation regime. See the comparison table below.

Data Presentation: Element Formulation Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Advanced Element Formulations

| Feature / Challenge | Hybrid (Mixed) Formulation | Unified Formulation (e.g., Solid-Shell) | Polygonal (Voronoi) Elements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Strength | Excellent for incompressible & nearly incompressible materials (J ≈ 1). | Robust under large deformations & complex loading; minimal locking. | Superior for complex geometries, mesh distortion tolerance, crack propagation. |

| Key Limitation | Requires careful selection of stable interpolation pairs; increased DOFs. | Formulation complexity can be higher than standard elements. | Computational cost per element is higher; less common in commercial FE codes. |

| Ideal Use Case | Cardiac tissue, brain matter, hydrogels. | Soft tissue contact, large bending of membranes, composite materials. | Irregular bone structures, tissue with voids/inclusions, adaptive remeshing studies. |

| Typical Convergence Rate | O(h^(k+1)) for displacements, O(h^k) for pressure (with stable pairs). | O(h²) for displacements (with quadratic assumptions). | Between O(h) and O(h²), heavily dependent on quadrature and shape functions. |

| Computational Cost (Relative) | Medium-High (extra pressure DOFs). | Medium. | High (many nodes/element, complex shape functions). |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Element Performance for Incompressible Rubber Block Objective: Quantify pressure oscillation and displacement error for different elements under confined compression.

- Geometry: Create a 10x10x10 mm cube.

- Material: Assign a nearly incompressible Neo-Hookean model (μ=0.5 MPa, κ >> μ, e.g., κ=50 MPa).

- Mesh: Generate meshes with (a) Linear Tetrahedra, (b) Hybrid Tetrahedra (e.g., P2-P1), (c) Linear Hexahedra, (d) Hybrid Hexahedra (e.g., Q2-P1).

- Boundary Condition: Fully fix the bottom face. Apply a 20% compressive displacement to the top face. Confine lateral expansion.

- Analysis: Run a static, large deformation simulation.

- Metrics: Compare the simulated reaction force against the analytical solution (if available). Plot the pressure field contour to check for oscillations. Calculate the L2 error norm of displacement.

Protocol 2: Large Bending of a Cantilever Beam (Patch Test) Objective: Assess sensitivity to mesh distortion and bending locking.

- Geometry: Create a 100x10x1 mm thin beam.

- Material: Assign a St. Venant-Kirchhoff model (E=10 MPa, ν=0.3).

- Mesh: Create a regular and a severely distorted mesh (skewed interior nodes) for: (a) Linear Quadrilaterals, (b) Unified solid-shell quadrilaterals, (c) Polygonal elements.

- Boundary Condition: Clamp one short end. Apply a pure bending moment or a shear load at the free end.

- Analysis: Run a large deformation static simulation.

- Metrics: Compare the tip displacement and final deformed shape with beam theory. Monitor the convergence of strain energy.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Hybrid Element Formulation Workflow

Diagram 2: Polygonal FE Solution Path for Large Strain

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Experiments

| Item | Function in Computational Experiment |

|---|---|

| FE Software with UEL/UMAT Support (e.g., Abaqus, FEBio) | Allows implementation of custom hybrid/polygonal element formulations via user subroutines. |

| Polygonal Mesh Generator (e.g., PolyMesher, Voro++) | Creates Voronoi-based or centroidal polygonal meshes from initial geometry for polygonal FE studies. |

| Non-linear Solver Library (e.g., PETSc, NLopt) | Provides robust algorithms (Newton-Raphson, Arc-length) for solving large deformation, non-linear systems. |

| Hyperelastic Constitutive Model Library | Provides stress/strain routines for incompressible materials (e.g., Neo-Hookean, Mooney-Rivlin, Ogden). |

| Visualization Tool (e.g., Paraview, Visit) | Post-processes results to visualize stress fields, detect locking, and compare deformation patterns. |

| Benchmark Problem Database | Contains analytical or trusted numerical solutions for classic problems (e.g., Cook's membrane, patch test) to validate new elements. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Mesh Contains Non-Manifold Edges or Vertices

- Problem: The generated 3D mesh has edges shared by more than two faces or vertices where fans of faces are not connected, causing solver failures in finite element analysis (FEA).

- Root Cause: Often originates from segmentation errors (thresholding, region growing) in the original medical image (CT/MRI), leading to topological inconsistencies in the label map.

- Solution Workflow:

- Pre-processing: Apply a slight Gaussian blur (σ=0.5-1.0 voxel) to the raw image data before segmentation to reduce noise.

- Segmentation Check: Use

mtools(e.g.,mcheck) or MeshLab'sCheck Non Manifold Edgesfilter on the preliminary surface. - Remediation: Execute a morphological closing operation (dilation followed by erosion) on the binary segmentation to close small holes. Re-mesh.

- Post-processing: Use automated repair functions in software like MeshLab (

Filters -> Cleaning and Repairing) or CGAL's polygon mesh processing library to delete non-manifold elements and re-triangulate.

Issue 2: Stair-Step Artifacts from Voxel Data

- Problem: The mesh surface exhibits a blocky, stair-stepped appearance, not reflecting the true anatomical smoothness, which introduces discretization error in stress concentration zones.

- Root Cause: Direct triangulation of voxelated binary masks without smoothing or adequate resolution.

- Solution Workflow:

- Isosurface Smoothing: When using Marching Cubes, apply Laplacian smoothing iteratively and with caution (e.g., 5-10 iterations, lambda=0.5). Over-smoothing erodes geometric accuracy.

- Subvoxel Refinement: Employ algorithms like Marching Cubes 33 or Dual Contouring that can generate surfaces passing through points other than voxel corners, capturing subvoxel precision.

- Mesh Refinement: Use a local remeshing algorithm (e.g., in MeshLab) to subdivide and smooth the mesh isotropically in regions of high curvature.

Issue 3: Inadequate Mesh Quality Metrics Causing Solver Divergence

- Problem: FEA solver (e.g., Abaqus, FEBio) fails due to poor element quality, even if the mesh is topologically correct.

- Root Cause: Elements with high aspect ratio, excessive skew, or very small dihedral angles (sliver elements).

- Solution Workflow:

- Metric Analysis: Calculate mesh quality metrics (See Table 1).

- Targeted Improvement: Use mesh optimization (e.g., NetGen's

OptimizeMeshor ANSA's quality optimizer) targeting the specific failed metric. Implement boundary-preserving smoothing. - Multi-Resolution Approach: Generate a coarse, high-quality mesh first, then apply controlled refinement in areas of interest.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the recommended workflow to minimize discretization error from imaging to simulation? A1: Follow a validated, multi-stage pipeline: 1) Image Acquisition & Denoising (Non-Local Means filter), 2) Segmentation (Level-Set methods preferred over simple thresholding), 3) Surface Generation (Marching Cubes 33 with 5 iterations of Laplacian smoothing), 4) Mesh Repair & Quality Check (see Table 1), 5) Boundary Condition Mapping, 6) Convergent Analysis (perform a mesh convergence study).

Q2: How do I choose between tetrahedral and hexahedral meshes for biomechanical models? A2: The choice involves a trade-off between automation and accuracy. Tetrahedral meshes are easier to generate automatically for complex anatomy but may exhibit "locking" behavior for incompressible materials (like soft tissue). Hexahedral meshes generally provide higher accuracy per degree of freedom but require more manual effort or advanced multi-block sweeping algorithms. For patient-specific models from imaging, tetrahedral meshes with quadratic elements are often a pragmatic starting point.

Q3: What are the critical mesh quality metrics I must check before running an FEA? A3: The essential metrics depend on your solver but universally include: Aspect Ratio (should be < 5 for tetrahedra in soft tissue analysis), Jacobian (must be positive at all integration points), Skewness (should be < 0.7), and Minimal Dihedral Angle (should be > 10° for tetrahedra). See Table 1 for benchmarks.

Q4: How can I preserve small but anatomically critical features (e.g., thin trabeculae, vessel walls) during meshing?

A4: Use image-based mesh sizing fields. Derive a local element size from the distance map of the segmentation. This allows for smaller elements near thin surfaces and larger elements in voluminous regions, balancing detail and computational cost. Software: vgStudio, Simpleware ScanIP, or the MMG platform.

Q5: My simulation results are sensitive to mesh density. How do I perform a proper convergence study? A5: Systematically refine your global mesh size (or local sizing field) by a factor (e.g., 1.5) to create 3-4 mesh variants. Run the same simulation on each. Plot your Quantity of Interest (QoI - e.g., max principal stress) against mesh density or degrees of freedom. Convergence is achieved when the change in QoI falls below an acceptable threshold (e.g., 2-5%).

Data Presentation

Table 1: Key Mesh Quality Metrics and Recommended Thresholds for Tetrahedral Biomechanical FE Meshes

| Metric | Definition | Ideal Range (Tetrahedron) | Critical Threshold | Tool for Calculation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspect Ratio | Ratio of longest edge to shortest altitude. | 1.0 - 3.0 | < 5.0 | ANSYS Meshing, NetGen, FEBio Mesh |

| Jacobian | Determinant of the Jacobian matrix at integration points. | > 0.6 | > 0.0 | Abaqus, FEBio |

| Skewness | Measure of angular deviation from ideal shape. | 0.0 - 0.5 | < 0.7 | ANSYS, CGAL |

| Min Dihedral Angle | Smallest angle between two faces. | > 20° | > 10° | MeshLab, Paraview |

| Max Dihedral Angle | Largest angle between two faces. | < 130° | < 160° | MeshLab, Paraview |

| Volume Change | Ratio of element volume to avg. volume of surrounding elements. | 0.8 - 1.2 | > 0.1 | Custom Scripts |

Table 2: Comparison of Surface Extraction Algorithms

| Algorithm | Pros | Cons | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marching Cubes (MC) | Simple, fast, robust. | Staircase artifacts, ambiguous cases. | Initial prototype, less curved surfaces. |

| Marching Cubes 33 (MC33) | Resolves ambiguities, smoother than MC. | Slightly more complex. | General-purpose medical data. |

| Dual Contouring (DC) | Captures sharp features, sub-voxel accuracy. | More complex, can produce non-manifold meshes. | CAD-based data, bones with sharp edges. |

| Level-Set Methods | Very smooth, intrinsic sub-voxel accuracy. | Computationally intensive, parameter tuning. | Soft tissue with smooth contours (organs). |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Mesh Convergence Study for a Tibial Bone Model Objective: Determine the mesh density required for a convergent solution in von Mises stress under compressive loading. Materials: Segmented Tibia CT scan (DICOM), Simpleware ScanIP/+, FEBio/ANSYS.

- Base Mesh Generation: In ScanIP, generate a quality tetrahedral mesh using the "Adaptive Remesher" with target Aspect Ratio = 3. Use a global element size of 1.5mm. Export as

.inpor.feb. - Refinement Series: Repeat Step 1, changing the global element size to 1.0mm, 0.75mm, and 0.5mm. Keep all other parameters (smoothing, quality targets) identical.

- FE Simulation Setup: Import each mesh into FEBio. Assign homogeneous linear elastic properties (E=10 GPa, ν=0.3). Apply a fixed constraint on the distal end and a 1000N compressive load on the proximal plateau.

- Execution & Analysis: Run each simulation. Extract the maximum von Mises stress from the proximal metaphyseal region. Plot this value against the number of elements/nodes.

- Convergence Criterion: Identify the mesh density at which a further 30% increase in element count changes the max stress by < 2%.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Smoothing Impact on Geometric Error Objective: Quantify the trade-off between surface smoothness and anatomical accuracy. Materials: Segmented Femur CT, high-resolution optical scan of 3D printed femur (ground truth), MeshLab, CloudCompare.

- Ground Truth Acquisition: 3D print the segmented femur. Scan it with a high-accuracy structured light scanner (e.g., ATOS Core) to obtain a reference mesh (M_ref).

- Test Mesh Generation: Generate 5 surface meshes from the same CT segmentation using Marching Cubes 33 in ScanIP. Apply 0, 3, 5, 10, and 15 iterations of Laplacian smoothing (lambda=0.5).

- Alignment: In CloudCompare, use the "Fine Registration (ICP)" tool to align each test mesh to M_ref.

- Distance Calculation: Compute the Hausdorff distance between each aligned test mesh and M_ref. Use CloudCompare's "Cloud/Mesh Distances" tool.

- Analysis: Plot smoothing iterations vs. Mean and 90th percentile Hausdorff distance. The optimal iteration minimizes distance while improving visual smoothness.

Mandatory Visualization

Title: Mesh Generation and Validation Workflow

Title: Sources of Discretization Error

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for High-Accuracy Mesh Generation

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function in Pipeline | Key Feature for Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3D Slicer | Open-Source Platform | Segmentation, Initial Surface Gen. | Extensive module library (e.g., Segment Editor). |

| Simpleware ScanIP (Synopsys) | Commercial Software | Integrated Seg-to-Mesh | Reliable FE-ready mesh generation with quality control. |

| MeshLab | Open-Source Processing | Mesh Repair, Cleaning, Analysis | Powerful filters for non-manifold repair and smoothing. |

| CGAL Library | Open-Source C++ Library | Advanced Algorithms | Robust algorithms for mesh generation and optimization. |

| MMG Platform | Open-Source Remesher | Adaptive Mesh Refinement | Anisotropic remeshing based on local sizing fields. |

| FEBio Studio | Free Integrated Suite | Pre-processing, Simulation, Check | Built-in mesh quality analyzer and FE solver. |

| CloudCompare | Open-Source 3D Analysis | Geometric Validation | Compute Hausdorff distance vs. ground truth scans. |

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Center

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQ

Q1: My simulation of stent deployment shows unrealistic vessel tearing or excessive mesh distortion. What steps should I take to resolve this?

A: This is a classic sign of excessive discretization error under large deformations.

- Primary Check - Element Formulation: Ensure you are using advanced element formulations suitable for large strains. Avoid using standard linear elements. Switch to elements with hybrid formulation (for incompressible/ nearly incompressible material behavior) and enhanced strain technology.

- Protocol for Mesh Convergence: Perform a mesh convergence study specifically at the point of maximum expansion.