Advanced Hydrogel Fabrication for Wound Healing: From Biomaterial Design to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the latest advancements in hydrogel fabrication for wound healing applications, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Advanced Hydrogel Fabrication for Wound Healing: From Biomaterial Design to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the latest advancements in hydrogel fabrication for wound healing applications, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It systematically explores the foundational principles of hydrogel design, including the critical properties of natural and synthetic polymers. The scope extends to cutting-edge fabrication methodologies, from 3D bioprinting to self-assembly, and their application in creating multifunctional and intelligent wound dressings. It further addresses key challenges in optimization, such as enhancing mechanical robustness and controlling drug release, and validates these approaches through a critical examination of preclinical and clinical evidence. By synthesizing insights across these four core intents, this review serves as a strategic guide for the continued development of clinically effective hydrogel-based therapies.

The Building Blocks of Healing: Hydrogel Fundamentals and Biomaterial Selection

The Physiology of Wound Healing and Rationale for Hydrogel Intervention

Chronic wounds, such as diabetic foot ulcers, venous ulcers, and pressure ulcers, represent a formidable global health challenge, affecting over 40 million patients annually and incurring healthcare costs exceeding $50 billion per year worldwide [1]. These wounds are characterized by a failure to proceed through an orderly and timely reparative process to produce anatomic and functional integrity [2]. The complex pathophysiology of chronic wounds includes persistent inflammation, elevated oxidative stress, bacterial colonization, biofilm formation, and impaired angiogenesis [1] [3]. Traditional wound dressings, including gauze and hydrocolloids, often fail to address this complex microenvironment, leading to prolonged healing times and increased risk of complications [4]. In contrast, hydrogel-based dressings have emerged as a promising class of biomaterials that actively support the healing process by maintaining a moist environment, providing a protective barrier, and delivering therapeutic agents [4] [5]. This application note examines the physiological basis of wound healing and establishes the scientific rationale for hydrogel intervention, providing researchers with detailed protocols for evaluating hydrogel efficacy in wound healing applications.

The Physiology of Wound Healing

Wound healing is a complex, dynamic process that restores function and integrity to damaged tissue. This process traditionally unfolds through four overlapping, precisely regulated phases: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling [2] [1].

Phases of Normal Wound Healing

Hemostasis: Immediately following injury, vasoconstriction occurs to reduce blood loss, followed by platelet aggregation at the site of vessel injury. These activated platelets form a provisional clot and release growth factors and chemokines that initiate the subsequent inflammatory phase [2] [1]. Platelets simultaneously release growth factors and recruit immune cells, establishing the foundation for tissue repair [6].

Inflammation: Characterized by the sequential infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages. Neutrophils are the first responders, clearing pathogens and debris through phagocytosis and releasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) [6]. Macrophages then replace neutrophils, transforming from a pro-inflammatory (M1) to an anti-inflammatory (M2) phenotype, which is crucial for resolving inflammation and initiating tissue repair [6] [1]. Dysregulation in this phase is a hallmark of chronic wounds.

Proliferation: This phase involves re-epithelialization, angiogenesis, and collagen synthesis. Fibroblasts migrate into the wound bed and produce extracellular matrix (ECM) components, particularly type III collagen. Simultaneously, new blood vessels form to restore oxygen and nutrient supply to the healing tissue [6] [2].

Remodeling: The final phase can last for months to years, during which fragile type III collagen is gradually replaced and reorganized into stronger type I collagen, providing mechanical robustness to the repaired tissue [6]. This process determines the ultimate strength and appearance of the healed wound, with excessive ECM deposition leading to fibrotic scarring [1] [3].

The Chronic Wound Microenvironment

Chronic wounds are characterized by a pathological deviation from the normal healing sequence, often stalling in the inflammatory phase due to a complex interplay of factors [1]. Key characteristics of the chronic wound microenvironment include:

- Persistent Inflammation: Sustained elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) and continuous neutrophil activity create a destructive cycle of inflammation and tissue damage [1].

- Elevated Oxidative Stress: Excessive accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) at the wound site creates a vicious ROS-inflammation cycle that heavily hinders tissue regeneration [3].

- Bacterial Biofilms: Drug-resistant bacterial biofilms, particularly in diabetic foot ulcers, increase drug resistance and aggravate inflammatory responses, significantly impeding healing [3].

- Impaired Angiogenesis: Inadequate formation of new blood vessels results in insufficient blood supply with limited oxygen and nutrient delivery to the wound bed [3].

Table 1: Key Biomarkers in the Chronic Wound Microenvironment

| Biomarker Category | Specific Markers | Significance in Chronic Wounds |

|---|---|---|

| Physiological Parameters | Temperature, Oxygen levels, Humidity | Elevated temperature indicates inflammation; hypoxia indicates impaired perfusion [6] |

| Biochemical Parameters | pH, Glucose, Uric acid | Acidic pH may indicate infection; hyperglycemia suggests diabetic dysregulation [6] |

| Inflammatory Cytokines | IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10 | Persistent elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokines indicates chronic inflammation [6] [1] |

| Oxidative Stress Markers | Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) | Excessive ROS creates oxidative stress-inflammation cycle [3] |

| Enzymatic Activity | Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) | Overexpression leads to excessive ECM degradation [1] |

Rationale for Hydrogel Intervention

Hydrogels are three-dimensional, hydrophilic polymeric networks with high water content that closely mimic the native extracellular matrix (ECM), making them ideal biomaterials for wound management [7] [5]. Their unique properties directly address the pathophysiological challenges present in chronic wounds.

Fundamental Advantages of Hydrogels

Moist Wound Environment: Hydrogels maintain a moist wound environment, which has been clinically proven to accelerate epithelialization and promote granulation tissue formation compared to dry wound beds [4]. Their high water content (often exceeding 90%) prevents wound desiccation while absorbing excess exudate [4] [5].

Gas Permeability: The porous structure of hydrogels allows for oxygen permeation to the wound bed while providing a physical barrier against external pathogens [5].

Biocompatibility and Biodegradability: Hydrogels can be fabricated from natural polymers such as chitosan, hyaluronic acid, alginate, and collagen, which exhibit inherent biocompatibility, low immunogenicity, and tunable degradation profiles [7] [5].

Thermal Insulation and Pain Relief: The high water content provides cooling sensation and pain relief through nerve ending insulation, significantly improving patient comfort during dressing changes [4].

Advanced Functional Capabilities

Beyond these fundamental advantages, advanced hydrogel systems offer sophisticated therapeutic capabilities:

Self-Healing Properties: Incorporating dynamic covalent bonds (e.g., Schiff base, disulfide bonds) or non-covalent interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding, host-guest interactions) enables hydrogels to autonomously repair damage after mechanical stress, restoring their structural integrity and extending their functional lifespan [7] [1]. This is particularly valuable for joint areas or wounds subject to movement.

Stimuli-Responsive Drug Delivery: Smart hydrogels can be engineered to release therapeutic agents in response to specific wound microenvironment triggers such as pH, temperature, enzyme activity, or ROS levels [7] [6]. For instance, Schiff base-crosslinked hydrogels degrade faster in the acidic environment of infected wounds, enabling targeted drug release [3].

Multifunctionality: Modern hydrogels can be designed with integrated properties including antibacterial activity (through incorporation of silver nanoparticles, antimicrobial peptides), antioxidant capacity (via ceria nanozymes, gallic acid), pro-angiogenic effects (through growth factor delivery), and even neural regeneration capabilities [1] [3].

Phase-Adaptive Regulation: Recent innovations include hydrogels with phase-adaptive regulating functions that provide different therapeutic actions according to the specific stage of wound healing. For example, a dynamically Schiff base-crosslinked hydrogel (F/R gel) can first eliminate multidrug-resistant bacterial biofilms, then interrupt the oxidative stress-inflammation cycle, and subsequently promote angiogenesis while suppressing fibrotic scarring [3].

Table 2: Hydrogel Functionalization Strategies for Chronic Wound Management

| Functionalization Approach | Mechanism of Action | Representative Agents |

|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobial Integration | Disrupt bacterial cell membranes, prevent biofilm formation | Silver nanoparticles, ε-polylysine, antimicrobial peptides [1] [3] |

| Antioxidant Incorporation | Scavenge excess ROS, break ROS-inflammation cycle | Ceria nanozymes, gallic acid, polyphenols [1] [3] |

| Pro-angiogenic Enhancement | Stimulate new blood vessel formation | Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), VEGF [6] [3] |

| Immunomodulation | Shift macrophages from M1 to M2 phenotype | IL-10, TGF-β, specialized nanoparticles [1] |

| Conductive Properties | Enable real-time wound monitoring | MXene, polypyrrole, PEDOT:PSS [6] [1] |

| Scar Suppression | Modulate fibroblast activity to prevent fibrosis | c-Jun siRNA, TGF-β inhibitors [3] |

Experimental Protocols for Hydrogel Evaluation

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Dynamic Schiff Base-Crosslinked Hydrogel

This protocol describes the synthesis of an injectable, self-healing hydrogel through Schiff base formation between ε-polylysine (εPL) and aldehyde-modified hyaluronic acid (HA-CHO), based on methodology from a recent groundbreaking study [3].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Aldehyde-Modified Hyaluronic Acid (HA-CHO): Synthesized by oxidizing hyaluronic acid with sodium periodate. Serves as the primary polymer backbone with aldehyde functional groups for crosslinking.

- ε-Polylysine (εPL): Cationic antimicrobial polypeptide containing primary amino groups that react with aldehyde groups to form Schiff base bonds.

- εPL-Modified Oxygen-Deficient Nanoceria (εPL-CeOv Nanozyme): Cerium oxide nanoparticles with surface-modified εPL, providing ROS-scavenging capability and antimicrobial activity.

- Drug-Loaded PLGA Microcapsules: Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) microspheres containing therapeutic agents (e.g., bFGF and c-Jun siRNA) for sustained release.

Procedure:

- Polymer Solution Preparation: Dissolve HA-CHO in PBS (pH 7.4) at a concentration of 4% (w/v). Separately, dissolve εPL in PBS at 5% (w/v).

- Nanozyme Incorporation: Uniformly disperse εPL-CeOv nanozyme (2.8 ± 0.8 nm) in the εPL solution at a concentration of 1 mg/mL using gentle sonication.

- Microcapsule Integration: Suspend F/R MCs (loaded with bFGF and c-Jun siRNA) in the HA-CHO solution at a concentration of 2% (w/v).

- Gelation Process: Mix the two component solutions (HA-CHO with MCs and εPL with nanozyme) in a 1:1 volume ratio. Rapid Schiff base formation will occur within approximately 3 seconds, forming a stable three-dimensional hydrogel network.

- Characterization: Confirm successful gelation through rheological measurements, showing storage modulus (G') exceeding loss modulus (G") with Young's modulus approximately 6.69 kPa.

Quality Control:

- Assess shear-thinning behavior by monitoring G' and G" under increasing shear strain (0%-1000% at 1 Hz).

- Evaluate self-healing properties through strain amplitude alternation tests (cycling between 1% and 500% strain).

- Verify porous microstructure using scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

Protocol 2: In Vitro Evaluation of Hydrogel Properties

Swelling and Degradation Kinetics:

- Cut hydrogel samples into standardized discs (e.g., 10 mm diameter, 2 mm thickness).

- Measure initial dry weight (Wd), then immerse in PBS (pH 7.4) or simulated wound fluid (pH 5.5-6.5).

- At predetermined time points, remove samples, gently blot excess surface liquid, and record wet weight (Ww).

- Calculate swelling ratio as (Ww - Wd)/Wd.

- For degradation, monitor mass loss over time and record complete dissolution time.

Drug Release Profiling:

- Prepare hydrogel samples incorporating fluorescently labeled therapeutic agents.

- Immerse in release medium under sink conditions at 37°C with gentle agitation.

- At designated intervals, collect and replace release medium.

- Analyze collected samples using fluorescence spectroscopy or HPLC to determine cumulative drug release.

- Compare release kinetics between physiological (pH 7.4) and acidic (pH 5.5-6.5) conditions to confirm pH-responsive behavior.

Antimicrobial Efficacy Testing:

- Prepare bacterial suspensions of clinically relevant strains (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, methicillin-resistant S. aureus [MRSA]) in nutrient broth.

- Incubate hydrogel discs with bacterial suspensions at 37°C for 24 hours.

- Determine minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) using standard microdilution methods.

- Assess biofilm inhibition by measuring biomass formation using crystal violet staining.

Antioxidant Activity Assessment:

- Treat cells (e.g., fibroblasts, macrophages) with hydrogen peroxide or lipopolysaccharide to induce oxidative stress.

- Apply hydrogel extracts or directly culture cells on hydrogel surfaces.

- Measure intracellular ROS levels using DCFH-DA fluorescence probe.

- Quantify expression of antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT, GPx) using ELISA or Western blot.

Protocol 3: In Vivo Assessment in Diabetic Wound Models

Animal Model Preparation:

- Use 8-10 week old db/db mice or streptozotocin-induced diabetic C57BL/6 mice.

- Anesthetize animals and create full-thickness excisional wounds (6-8 mm diameter) on the dorsal skin.

- Infect wounds with MRSA or P. aeruginosa (1×10^8 CFU) for infected wound models.

Treatment Groups:

- Group 1: Untreated control

- Group 2: Conventional dressing (e.g., gauze)

- Group 3: Basic hydrogel dressing

- Group 4: Advanced multifunctional hydrogel (e.g., F/R gel)

Wound Monitoring and Analysis:

- Macroscopic Assessment: Photograph wounds daily and calculate wound area reduction percentage.

- Histological Analysis: At days 7, 14, and 21 post-wounding, harvest wound tissues for:

- H&E staining to assess re-epithelialization and granulation tissue formation

- Masson's trichrome staining to evaluate collagen deposition and organization

- Immunofluorescence staining for CD31 (angiogenesis), F4/80 (macrophage infiltration), and α-SMA (myofibroblasts)

- Molecular Analysis:

- Measure inflammatory cytokine levels (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-10) using ELISA

- Assess oxidative stress markers (SOD, MDA, MPO) in wound tissues

- Evaluate expression of fibrotic markers (TGF-β, α-SMA, collagen I/III) using RT-qPCR or Western blot

- Scar Assessment: At day 28, evaluate scar formation using:

- Visual analog scales

- Histological scoring of collagen architecture

- Measurement of scar elevation index

Visualization of Wound Healing and Hydrogel Action Mechanisms

Diagram 1: Wound Healing Physiology and Hydrogel Intervention Points. This diagram illustrates the sequential phases of normal wound healing, the pathophysiological deviations in chronic wounds, and the multiple intervention points where advanced hydrogel dressings exert their therapeutic effects.

The physiological process of wound healing represents an intricate cascade of cellular and molecular events that, when dysregulated, leads to chronic, non-healing wounds. Hydrogel-based interventions provide a sophisticated, multifaceted approach to addressing the complex pathophysiology of these challenging wounds. Through their unique capacity to maintain a moist wound environment, provide structural support, deliver therapeutic agents in a spatiotemporally controlled manner, and dynamically respond to the wound microenvironment, hydrogels represent a paradigm shift in wound management. The experimental protocols outlined in this application note provide researchers with robust methodologies for developing and evaluating next-generation hydrogel dressings, with the ultimate goal of restoring timely, anatomically functional, and scar-free tissue repair for patients suffering from chronic wounds. As hydrogel technology continues to advance, incorporating increasingly sophisticated functionalities such as real-time monitoring, closed-loop feedback systems, and personalized therapeutic regimens, these biomaterials are poised to revolutionize wound care and significantly improve patient outcomes.

The management of acute and chronic wounds presents a significant global healthcare challenge. Chronic wounds, such as diabetic foot ulcers, venous leg ulcers, and pressure ulcers, are characterized by a failure to proceed through an orderly and timely healing process, often stalling in the inflammatory phase due to persistent bacterial infection, prolonged inflammation, impaired angiogenesis, and elevated levels of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [8] [9]. Conventional wound dressings, including gauze, often prove inadequate as they can adhere to the wound bed, cause secondary injury upon removal, and fail to provide an optimal healing environment [9].

In response to these limitations, hydrogel-based wound dressings have emerged as a promising advanced therapeutic strategy. Hydrogels are three-dimensional, hydrophilic polymer networks that can absorb large amounts of water while maintaining their structure, thereby providing a moist wound environment conducive to healing [10] [11]. Among them, hydrogels fabricated from natural polymers—particularly chitosan, hyaluronic acid, alginate, and collagen—offer distinct advantages due to their inherent biocompatibility, biodegradability, low immunogenicity, and bioactivity [8] [11]. These materials closely mimic the native extracellular matrix (ECM), facilitating cell adhesion, proliferation, and migration, and can be engineered as delivery platforms for therapeutic agents like antimicrobials, nanoparticles, growth factors, and exosomes [8]. This application note details the bioactive properties of these four key natural polymers and provides standardized protocols for their incorporation into hydrogels for wound healing applications, framed within a broader thesis on advanced hydrogel fabrication.

Bioactive Properties and Mechanisms of Action

The efficacy of natural polymer-based hydrogels in wound healing stems from their diverse and synergistic bioactive properties, which actively modulate the wound microenvironment to promote regeneration.

Table 1: Bioactive Properties of Natural Polymers in Wound Healing

| Polymer | Source | Key Bioactive Properties | Role in Wound Healing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | Crustacean exoskeletons, insects [12] | Antibacterial (cationic nature disrupts bacterial membranes) [12], Hemostatic [13], promotes granulation tissue formation [14] | Controls infection, accelerates blood clotting, supports new tissue growth |

| Hyaluronic Acid (HA) | Bacterial fermentation, animal tissues [15] | Angiogenic, Anti-inflammatory, regulates collagen deposition [15] [9] | Promotes blood vessel formation, modulates inflammation, improves tissue remodeling |

| Alginate | Seaweed [16] [17] | High absorbency, forms gel in contact with exudate, facilitates ion exchange (Ca²âº/Naâº) [16] [17] | Manages wound exudate, maintains moist environment, supports debridement |

| Collagen | Bovine, porcine, marine tissues [10] | Cell adhesion & migration, low antigenicity, promotes fibroblast proliferation [10] | Serves as a scaffold for cellular infiltration, fundamental for all healing stages |

The wound healing process is a complex cascade that can be disrupted in chronic states. The following diagram illustrates the normal healing pathway and how chronic wounds deviate from it, highlighting the therapeutic targets for natural polymer hydrogels.

Diagram 1: The wound healing cascade and points of failure in chronic wounds. Chronic wounds often stall in the inflammatory phase due to a combination of disruptive factors, preventing progression to proliferation and remodeling [8] [9] [11].

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Chitosan-Based Thermosensitive Hydrogel

Application Notes: Thermosensitive chitosan hydrogels are injectable systems that exist as liquids at room temperature and undergo a sol-gel transition at body temperature (37°C). This allows for minimally invasive application that perfectly conforms to irregular wound beds [12]. A common formulation involves combining chitosan with sodium glycerophosphate (GP).

Protocol: Fabrication of Chitosan-Sodium Glycerophosphate (CS-GP) Hydrogel [12]

Objective: To prepare an injectable, thermosensitive hydrogel for drug delivery and wound dressing.

Materials:

- Chitosan (medium molecular weight, deacetylation degree > 85%)

- Sodium β-glycerophosphate (GP)

- Hydrochloric acid (HCl, 0.1 M)

- Deionized water

- Magnetic stirrer with heating plate

- Ice bath

- pH meter

Procedure:

- Chitosan Solution Preparation: Dissolve 2 g of chitosan in 100 mL of 0.1 M HCl solution under vigorous stirring at room temperature overnight to obtain a clear, viscous 2% (w/v) chitosan solution.

- Cooling: Cool the chitosan solution to 4°C in an ice bath.

- GP Solution Preparation: Prepare a 50% (w/v) aqueous solution of GP and cool it to 4°C.

- Mixing: Slowly add the chilled GP solution dropwise into the chilled chitosan solution under constant stirring. Maintain the temperature below 5°C during this process to prevent premature gelation.

- pH Adjustment: Continue stirring until a homogeneous solution is formed. The final pH should be between 7.0 and 7.2; adjust with dilute NaOH or HCl if necessary.

- Gelation Test: Incubate a small aliquot of the final mixture in a water bath at 37°C. The gelation time is typically between 2 to 10 minutes, forming an opaque gel.

The mechanism behind the sol-gel transition is a temperature-driven shift in molecular interactions, as shown below.

Diagram 2: The sol-gel transition mechanism in LCST-type thermosensitive hydrogels like CS-GP. The shift from sol to gel is driven by a change in the dominant molecular interaction from hydrophilic to hydrophobic as temperature increases, which is reflected in the system's Gibbs free energy (ΔG = ΔH - TΔS) [12].

Hyaluronic Acid-Based Multifunctional Hydrogel

Application Notes: Hyaluronic acid (HA) is a core component of the ECM and is crucial for regulating inflammation and promoting tissue regeneration. Methacrylated HA (HAMA) can be crosslinked to form hydrogels with tunable mechanical properties and high stability, suitable for loading and sustaining the release of therapeutic agents [15] [9].

Protocol: Fabrication of an HA-Based Hybrid (HMGF) Hydrogel [15]

Objective: To synthesize a photocrosslinked HA hydrogel synergized with glycyrrhizic acid (GA) and Fe³⺠for antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activity.

Materials:

- Methacrylated Hyaluronic Acid (HAMA)

- Acrylamide (AM)

- Glycyrrhizic acid (GA)

- Iron (III) chloride (FeCl₃)

- Photoinitiator (e.g., Irgacure 2959)

- UV light source (e.g., 365 nm wavelength)

Procedure:

- Polymer Solution Preparation: Dissolve HAMA and AM in PBS or deionized water to a final concentration of 3-5% (w/v).

- Functionalization: Add GA (e.g., 1-2 mg/mL) and FeCl₃ (e.g., 0.5-1 mM) to the polymer solution. Stir thoroughly to ensure a homogeneous mixture.

- Photoinitiator Addition: Add the photoinitiator Irgacure 2959 to a final concentration of 0.05-0.1% (w/v) and stir until completely dissolved.

- Molding and Crosslinking: Pour the solution into a mold matching the wound shape. Expose the mold to UV light (365 nm, 5-10 mW/cm²) for 3-10 minutes to initiate free radical polymerization and form a stable, crosslinked hydrogel.

- Sterilization and Storage: The resulting HMGF hydrogel can be sterilized under UV light and should be stored at 4°C in a sealed container until use.

Alginate-Based Hydrogel for Sustained Drug Delivery

Application Notes: Alginate hydrogels are ideal for exuding wounds due to their high absorbency. Ionically crosslinked alginate gels can be used for the sustained release of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) to combat biofilm-associated infections in chronic wounds like diabetic foot ulcers [16].

Protocol: Fabrication of an Alginate-Based Antimicrobial Peptide (AMP) Delivery Hydrogel [16]

Objective: To create an alginate hydrogel for the sustained release of an antimicrobial peptide.

Materials:

- Sodium Alginate (high G-content preferred)

- Antimicrobial Peptide (AMP)

- Calcium Chloride (CaClâ‚‚) solution (e.g., 50-100 mM)

- Deionized water

Procedure:

- Alginate/AMP Solution: Dissolve sodium alginate (e.g., 2% w/v) and the selected AMP (e.g., 0.1-1 mg/mL) in deionized water under gentle stirring to avoid peptide denaturation.

- Gel Formation via Ionic Crosslinking:

- Method A (In-situ gelation): Mix the alginate/AMP solution with a soluble calcium salt (e.g., CaCO₃) and a slow acidifier (e.g., glucono-δ-lactone, GDL) to gradually release Ca²⺠ions and form a homogeneous gel.

- Method B (Diffusion gelation): Add the alginate/AMP solution dropwise into a bath of gently stirred CaClâ‚‚ solution. The droplets will instantaneously form hydrogel beads. Alternatively, pour the solution into a mold and submerge it in the CaClâ‚‚ solution for bulk gel formation.

- Washing and Equilibration: After gelation (typically 30-60 minutes), remove the hydrogel, rinse with deionized water to remove unreacted ions and surface-bound AMP, and equilibrate in a buffer (e.g., PBS, pH 7.4) before use or characterization.

Collagen-Based Bioactive Hydrogel

Application Notes: Collagen hydrogels provide an excellent biomimetic scaffold that supports all phases of wound healing. Their main limitations—mechanical strength and rapid degradation—can be improved through crosslinking or forming composite hydrogels with other polymers like chitosan or alginate [10].

Protocol: Fabrication of a Crosslinked Collagen-Chitosan Composite Hydrogel [10]

Objective: To prepare a mechanically stable collagen-based composite hydrogel with enhanced properties for wound dressing.

Materials:

- Type I Collagen solution (e.g., from bovine or rat tail tendon)

- Chitosan

- Acetic acid (0.1 M)

- Crosslinker (e.g., PEGDE 500 or Genipin)

- Deionized water

Procedure:

- Chitosan Solution: Dissolve chitosan in 0.1 M acetic acid to obtain a 1-2% (w/v) solution.

- Mixing: Gently mix the collagen solution (e.g., 3-5 mg/mL) and the chitosan solution in a desired mass ratio (e.g., 1:1 or 2:1 collagen:chitosan) under slow stirring at 4°C to prevent collagen fibrillation.

- pH Neutralization: Add a neutralization medium (e.g., NaOH or sodium bicarbonate solution) to raise the pH to approximately 7.4, inducing the initial physical gelation of collagen.

- Chemical Crosslinking: Add a chemical crosslinker like PEGDE 500 (e.g., 1-5% w/w of polymer) to the blend. Incubate the mixture at 37°C for 2-24 hours to form a covalently crosslinked, stable composite hydrogel.

- Hydration and Storage: Wash the formed hydrogel with PBS to remove residual crosslinker and maintain it in a hydrated state at 4°C.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Data of Natural Polymer Hydrogels

| Hydrogel System | Key Performance Metrics | Experimental Results | Reference Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan Thermosensitive | Gelation Time at 37°C | 2 - 10 minutes | Chitosan-GP Hydrogel [12] |

| HA-Based Hybrid (HMGF) | Wound Closure Rate (in vivo, Day 14) | ~90% closure | HMGF Hydrogel [15] |

| Alginate for Drug Delivery | Swelling Capacity (PBS) | Up to 90 g/dm² | Gelatin-Alginate Hydrogel [17] |

| Collagen-Based | Water Vapor Transmission Rate (WVTR) | ~2750 g/m²/day | Collagen-Chitosan Hydrogel [10] |

| General Hydrogel | Antibacterial Efficacy (against S. aureus/E. coli) | Significant inhibition zone | PM@CS Hydrogel [13] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Hydrogel Fabrication and Characterization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Methacrylated Polymers (e.g., HAMA) | Enables photocrosslinking for tunable mechanical properties and in-situ gelation. | Fabrication of structurally stable HA hydrogels [15]. |

| Sodium Glycerophosphate (GP) | A key component for inducing thermosensitivity in chitosan solutions. | Preparing injectable CS-GP hydrogels [12]. |

| Ionic Crosslinkers (e.g., CaClâ‚‚) | Induces rapid gelation of anionic polymers like alginate via ionic bridging. | Forming alginate beads or bulk gels for drug delivery [16] [17]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol Diglycidyl Ether (PEGDE) | A biocompatible chemical crosslinker for enhancing mechanical strength and stability. | Crosslinking gelatin-alginate [17] or collagen-chitosan [10] hydrogels. |

| Glycyrrhizic Acid & Fe³⺠Ions | Provides synergistic antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activity. | Functionalizing HA hydrogels for infected wound management [15]. |

| Cell-Free Probiotic Metabolites (CFPM) | Source of bioactive compounds (organic acids, bacteriocins) for antimicrobial activity. | Loading into chitosan hydrogels to create probiotic metabolite-based dressings [13]. |

| DBCO-Val-Cit-PABC-PNP | DBCO-Val-Cit-PABC-PNP, MF:C46H49N7O10, MW:859.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Aminooxy-amido-PEG4-propargyl | Aminooxy-amido-PEG4-propargyl, MF:C13H24N2O6, MW:304.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The effective management of acute and chronic wounds remains a significant challenge in healthcare, driving the need for advanced therapeutic solutions. Hydrogels, three-dimensional hydrophilic polymer networks, have emerged as a cornerstone of modern wound care due to their ability to maintain a moist wound environment, absorb exudate, and facilitate autolytic debridement [18]. Among the various materials used in hydrogel fabrication, synthetic polymers—particularly polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polyethylene glycol (PEG), and polyacrylamide (PAAm)—offer distinct advantages for wound healing applications, including precise tunability of physical properties, consistent quality, and controllable biodegradation profiles [19] [20]. These polymers can be engineered to create ideal wound dressings that protect against external contaminants, promote cell migration, and minimize interference with the natural healing process [21].

The versatility of PVA, PEG, and PAAm stems from their modifiable chemical structures, which enable researchers to fine-tune mechanical strength, swelling behavior, and bioadhesion properties to address specific clinical requirements. This application note explores the unique characteristics of these synthetic polymers, provides detailed experimental protocols for hydrogel fabrication, and presents quantitative data on their performance in wound healing applications, specifically within the context of a broader thesis on advanced hydrogel fabrication for improved wound management.

Polymer Properties and Tunability

The effectiveness of synthetic polymer-based hydrogels in wound healing applications derives from their customizable physical and chemical properties. The table below summarizes the key characteristics and tuning parameters for PVA, PEG, and PAAm:

Table 1: Tunable Properties of Synthetic Polymers for Wound Healing Hydrogels

| Polymer | Key Properties | Tunable Parameters | Cross-linking Methods | Wound Healing Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVA | Excellent mechanical strength, high biocompatibility, good water content [19] [22] | Molecular weight, degree of hydrolysis, concentration [23] | Freeze-thaw cycles, chemical cross-linkers (e.g., glutaraldehyde), salting-out [19] [22] | Creates robust, flexible dressings; promotes moist environment [23] |

| PEG | High hydrophilicity, biocompatibility, non-immunogenicity [20] | Molecular weight, branching density, functional end-groups | Physical entanglement, chemical cross-linking (e.g., with acrylamide) [20] | Enhances hydration; can be copolymerized for improved drug delivery [20] |

| PAAm | Responsive swelling behavior, functionalizable backbone | Co-monomer composition, cross-linking density | Free radical polymerization, covalent cross-linking [20] | Provides structural framework; enables controlled release of therapeutic agents [20] |

The mechanical and swelling properties of these polymers can be precisely controlled through synthetic parameters. For PVA, higher molecular weights (e.g., Mowiol 56–98 with Mw~195,000) and full hydrolysis (98.0–98.8%) produce cryogels with enhanced structural integrity, while partially hydrolyzed grades offer improved water absorption [23]. The freeze-thaw method, employing temperatures as low as -80°C, creates more open, interconnected structures with superior mechanical strength and elasticity compared to conventional -25°C freezing [23]. Incorporating PEG and PAAm into PVA-based systems further enhances functionality; for instance, PVA-co-AAm hydrogels demonstrate improved breaking strength, deformability, and compatibility with cutaneous tissue [20].

Quantitative Performance Data

Recent studies have provided quantitative evidence supporting the efficacy of synthetic polymer hydrogels in wound healing applications. The following table summarizes key experimental findings:

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Synthetic Polymer Hydrogels in Wound Healing Models

| Hydrogel Composition | Experimental Model | Key Performance Metrics | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVA-based micro-patterned (checks pattern) | SD rat skin wounds | Wound Closure Rate (WCR) at day 7 | 90.4% WCR [21] | |

| PVA-based micro-patterned (checks pattern) | SD rat skin wounds | Time constant (Ï„) to reach 63.2% WCR | 2.7 days [21] | |

| PVA-co-AAm with bromelain | In vitro release study | Bromelain release profile | Sustained release over extended period [20] | |

| PVA/PEG/CuO nanocomposite (1% CuO) | Antimicrobial testing | Antibacterial activity against S. aureus and E. coli | Highest antibacterial properties [24] | |

| PVA/PEG/CuO nanocomposite | Cytocompatibility testing | Cell viability | >70% cell viability [24] | |

| PVA/CMC/PEG bi-layer | Full-thickness skin defects | Wound closure acceleration | Significant acceleration vs. controls [25] | |

| 8% PVA56-98 with 10% PG | Mechanical testing | Stretchability, durability, low adhesion | Optimal balance for wound dressing [23] |

The performance advantages of specific hydrogel designs are particularly notable. Micro-patterned hydrogels with checks patterns demonstrated significantly superior wound healing efficacy compared to wave, line, and non-patterned hydrogels, achieving a 90.4% wound closure rate within 7 days compared to 65.1% in the vehicle control group [21]. This enhanced performance is attributed to increased surface area and volume in the vertical direction, which positively influences cellular responses and wound fluid management [21].

Experimental Protocols

Fabrication of PVA-based Cryogels via Freeze-Thaw Method

Materials: Polyvinyl alcohol (e.g., Mowiol 56–98, Mw~195,000; DH = 98.0–98.8%), propylene glycol, distilled water, sodium chloride, mucin (from porcine stomach, type II) [23].

Procedure:

- Prepare an 8% (w/w) PVA solution by dissolving PVA in distilled water at 90°C with slow stirring (1.5-4 hours until fully dissolved)

- Add 10% (w/w) propylene glycol as a plasticizer and mix thoroughly

- Degas the solution to remove air bubbles

- Pour the solution into appropriate molds for membrane formation

- Subject the samples to freezing at -80°C for 12-24 hours, followed by thawing at room temperature for 8-12 hours

- Repeat the freeze-thaw cycle 3-6 times to increase crystallinity and mechanical strength

- Characterize the resulting cryogels for mechanical properties, absorption capacity, and microstructure [23]

Note: The number of freeze-thaw cycles significantly impacts the final material properties. Higher cycles (up to 6) increase crystallinity, toughness, and tensile properties while decreasing the swelling coefficient [22].

Synthesis of PVA-co-AAm and PEG-co-AAm Hydrogels for Drug Delivery

Materials: PVA, PEG, acrylamide (AAm), N,N'-methylene-bis-acrylamide (BIS), ammonium persulfate (APS), N,N,N',N'-tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED), bromelain [20].

Procedure:

- Prepare separate solutions of PVA and PEG in distilled water

- Dissolve AAm and BIS (cross-linker) in the polymer solutions

- Add APS (initiator) and TEMED (catalyst) to initiate copolymerization

- For drug-loaded hydrogels, incorporate bromelain (or other therapeutic agents) into the solution prior to gelation

- Plate the solution and allow copolymerization to occur (typically rapid)

- Characterize swelling capacity by immersing hydrogels in solution and measuring weight gain at intervals (up to 24 hours)

- Evaluate mechanical properties through tensile testing and deformability measurements [20]

Applications: These copolymer hydrogels are particularly suitable for controlled release of therapeutic proteins like bromelain, which demonstrates anti-inflammatory and debridement properties beneficial for wound healing [20].

Preparation of PVA/CMC/PEG Bi-Layer Hydrogels with Gradient Pore Sizes

Materials: PVA, carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), PEG [25].

Procedure:

- Prepare single-layer PVA/CMC/PEG hydrogels using a thawing-freezing method

- Control pore size through processing parameters

- Fabricate bi-layer hydrogels with gradually increasing pore sizes from upper to lower layer

- Ensure strong bonding between the two layers

- Characterize physical properties, including bacterial penetration resistance and moisture retention capability

- Evaluate wound healing efficacy using full-thickness skin defect models [25]

Advantages: The bi-layer design with gradient pore sizes provides dual functionality—the denser upper layer protects against bacterial penetration while the more porous lower layer facilitates fluid management and tissue integration [25].

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

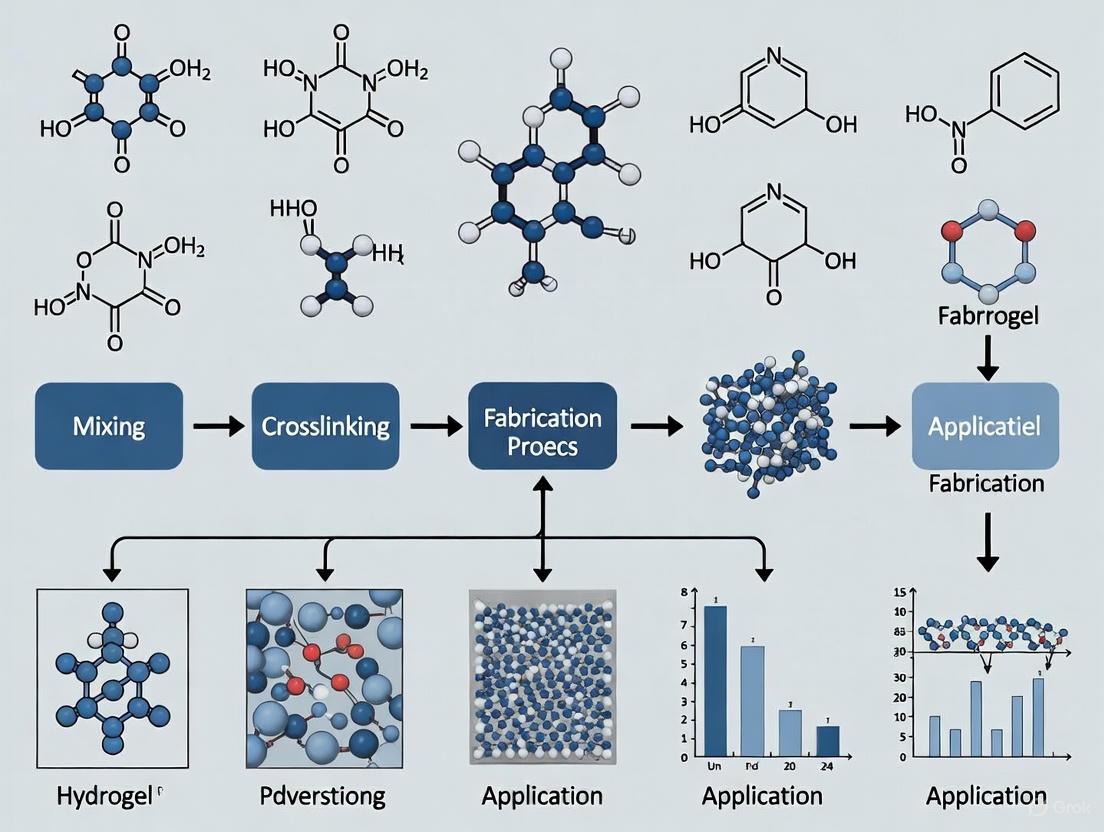

Hydrogel Fabrication and Evaluation Pathway

Wound Healing Mechanism of Action

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Synthetic Polymer Hydrogel Fabrication

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base Polymers | PVA (Mowiol series: 8-88, 56-98), PEG (various MW), Acrylamide | Primary matrix formation | Select PVA based on MW and hydrolysis degree; Higher MW (e.g., 56-98) for mechanical strength [23] |

| Cross-linking Agents | Glutaraldehyde, N,N'-methylene-bis-acrylamide (BIS), Ammonium persulfate (APS) | Create 3D network structure | Chemical cross-linkers enhance stability; Physical cross-linking improves biocompatibility [19] [20] |

| Plasticizers | Propylene glycol, Glycerol | Enhance flexibility and stretchability | 10% (w/w) PG optimizes mechanical properties [23] |

| Active Compounds | Bromelain, Neomycin, Copper oxide nanoparticles | Provide therapeutic activity | Bromelain offers anti-inflammatory and debriding action; CuO adds antimicrobial properties [20] [26] [24] |

| Characterization Reagents | Mucin, Bradford reagent, Azocasein | Assess functional performance | Evaluate swelling, protein content, and enzymatic activity [20] [23] |

Synthetic polymers PVA, PEG, and PAAm provide an exceptionally versatile platform for developing advanced wound healing hydrogels with tunable properties. Through controlled fabrication techniques such as freeze-thaw cycling, chemical cross-linking, and copolymerization, researchers can precisely engineer hydrogels with optimal mechanical strength, swelling behavior, and biofunctional characteristics. The quantitative data presented demonstrates the significant potential of these materials to accelerate wound closure, enhance collagen expression, and prevent infection. As research progresses, the integration of innovative elements such as micro-patterning, nanocomposites, and bi-layer designs will further expand the capabilities of synthetic polymer hydrogels, ultimately leading to more effective wound management solutions that address the complex challenges of both acute and chronic wounds.

Hydrogels, three-dimensional networks of hydrophilic polymers, have emerged as cornerstone materials in advanced wound care due to their high water content, biocompatibility, and ability to mimic the native extracellular matrix (ECM) [7] [27]. The defining characteristic of any hydrogel—its structural integrity and subsequent functionality in a hydrated state—is dictated by its crosslinking mechanism. Crosslinking describes the process by which polymer chains are interconnected, forming a cohesive network that can swell in water without dissolving. In the context of wound healing, the choice of crosslinking chemistry is not merely a manufacturing consideration; it is a fundamental design parameter that directly influences a hydrogel's mechanical properties, degradation profile, bioactivity, and ultimately, its therapeutic efficacy [28] [29]. This Application Note delineates the primary crosslinking mechanisms employed in hydrogel fabrication for wound healing, provides quantitative comparisons, details standardized experimental protocols, and visualizes critical structure-function relationships to guide research and development.

Classification and Impact of Crosslinking Mechanisms

Hydrogel crosslinking is broadly categorized into physical (reversible) and chemical (permanent) bonds, with advanced hybrid systems combining both approaches to achieve tailored properties [30]. The selection of a crosslinking mechanism profoundly impacts the hydrogel's performance as a wound dressing, influencing critical processes such as cellular infiltration, immunomodulation, and drug release.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Primary Hydrogel Crosslinking Mechanisms for Wound Healing

| Crosslinking Type | Bond Nature | Key Characteristics | Impact on Wound Healing Properties | Common Polymers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical (Reversible) [30] | Non-covalent (H-bonds, ionic, hydrophobic) | Reversible, stimuli-responsive, often injectable, weaker mechanical strength. | Promotes cellular integration and tissue remodeling; allows for minimally invasive application. | Alginate, Chitosan, Gelatin, PVA |

| Chemical (Permanent) [28] [30] | Covalent (C-C, ester, amide) | Permanent, mechanically robust, controlled degradation, risk of cytotoxicity. | Provides structural support for longer durations; enables sustained drug release. | PEG, PVA, GelMA, PAAm |

| Dynamic Covalent [7] | Reversible covalent (e.g., Schiff base, Diels-Alder) | Self-healing, shear-thinning, high mechanical strength. | Extends dressing lifespan; maintains integrity under stress in dynamic wound environment. | Chitosan, Hyaluronic Acid |

The physical properties imparted by crosslinking directly dictate biological outcomes. A seminal study on gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) hydrogels demonstrated that lightly crosslinked (soft) hydrogels promoted greater cellular infiltration and resulted in significantly smaller scars compared to heavily crosslinked (stiff) hydrogels [29]. Heavily crosslinked hydrogels increased inflammation and promoted a pro-fibrotic fibroblast response, underscoring how crosslinking density can guide cellular responses to improve healing.

Experimental Protocol: Fabricating and Evaluating Crosslinked Hydrogels

The following protocol details the synthesis and characterization of a model chemically crosslinked hydrogel system, adaptable for various polymer backbones.

Materials and Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Hydrogel Crosslinking Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example Specification / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gelatin Methacrylate (GelMA) [29] | Photocrosslinkable polymer backbone | Degree of functionalization > 70% |

| Lithium Phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | Photoinitiator | Enables crosslinking under UV light (365-405 nm) |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) [31] | Synthetic polymer crosslinker | Mn = 700-10,000 Da; defines network mesh size |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) dithiol (PEG-DT) [31] | Crosslinker for Michael addition | Mn = 3,400 Da; reacts with acrylate/vinyl sulfone groups |

| Genipin [30] | Natural, biocompatible chemical crosslinker | Alternative to toxic glutaraldehyde |

| Dulbecco's Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS) | Swelling and degradation medium | pH 7.4, isotonic |

Step-by-Step Procedure: Photo-Crosslinking of GelMA Hydrogels

This protocol creates hydrogels with tunable crosslinking density for wound healing applications [29].

- Polymer Solution Preparation: Dissolve GelMA macromer in DPBS at a concentration of 5-15% (w/v) to create a stock solution. Gently heat to 37°C to aid dissolution if necessary.

- Photoinitiator Incorporation: Add the photoinitiator LAP to the GelMA solution at a concentration of 0.1-0.5% (w/v). Protect the solution from light and vortex until fully dissolved.

- Molding and Degassing: Pipette the precursor solution into a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) mold or between two glass plates separated by a spacer. Place the mold in a vacuum desiccator for 10-15 minutes to remove air bubbles introduced during mixing.

- UV Light Crosslinking:

- For lightly crosslinked (lo-) GelMA (≈3 kPa): Expose the solution to 365 nm UV light at an intensity of 5-10 mW/cm² for 1 minute.

- For heavily crosslinked (hi-) GelMA (≈150 kPa): Expose the solution to 365 nm UV light at the same intensity for 5 minutes.

- Post-Processing and Sterilization: Carefully extract the crosslinked hydrogel from the mold. For cell culture or in vivo studies, wash the hydrogels three times in sterile DPBS and sterilize under UV light in a biosafety cabinet for 30 minutes per side.

Key Characterization Methods

- Swelling Ratio (Q): Weigh the hydrogel after synthesis (Wd), swell it in DPBS at 37°C for 24-48 hours until equilibrium, then weigh again (Ws). Calculate Q = (Ws - Wd) / Wd. Higher crosslinking density typically results in a lower Q [28].

- Compressive Modulus: Perform uniaxial compression testing on equilibrated hydrogels using a texture analyzer or dynamic mechanical analyzer. The slope of the initial linear region of the stress-strain curve provides the compressive modulus, which correlates directly with crosslinking density [29].

- In Vitro Drug Release: For drug-loaded hydrogels, incubate the hydrogel in a release medium (e.g., DPBS) at 37°C under gentle agitation. Periodically collect release medium and analyze drug concentration via HPLC or UV-Vis spectroscopy. Crosslinking density directly controls release kinetics, from burst to sustained release [31].

Visualization of Crosslinking-Dependent Cell Signaling in Wound Healing

The crosslinking density of a hydrogel dressing directly modulates the behavior of key cells involved in wound repair, such as macrophages and fibroblasts. The following diagram illustrates the distinct signaling pathways activated by soft versus stiff hydrogels.

Figure 1: Cellular Signaling Pathways Modulated by Hydrogel Crosslinking. Soft, lightly crosslinked hydrogels promote a pro-regenerative environment, leading to better healing outcomes. In contrast, stiff, heavily crosslinked hydrogels trigger inflammatory and pro-fibrotic signaling between macrophages and fibroblasts, resulting in increased scarring [29].

The precise engineering of crosslinking mechanisms enables the development of advanced "smart" hydrogels for complex wound management. These include:

- Stimuli-Responsive Drug Release: Hydrogels can be crosslinked to respond to specific wound microenvironment cues (e.g., pH, temperature, or enzyme levels) for on-demand therapeutic agent release [32] [2].

- Self-Healing Hydrogels: Incorporating dynamic reversible bonds (both non-covalent and covalent) allows hydrogels to autonomously repair damage, extending their functional lifespan on dynamic wound beds [7].

- Conductive Hydrogels: Crosslinking conductive polymers (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) or nanomaterials into hydrogel networks facilitates their use as diagnostic dressings for real-time wound monitoring [2].

In conclusion, crosslinking is the foundational process that defines the structure-property-function relationship of hydrogels. A deep understanding of these mechanisms—from simple physical entanglements to complex dynamic covalent networks—is paramount for designing next-generation wound dressings. By strategically selecting the crosslinking chemistry and density, researchers can precisely control hydrogel performance to actively guide the wound healing process toward regeneration, rather than mere repair.

The pursuit of an ideal wound dressing is a central objective in the field of biomedical engineering, particularly within advanced hydrogel fabrication research. The skin, being the largest organ of the human body, serves as a critical physico-chemical barrier against environmental insults, and its impairment necessitates dressings that actively support the complex healing cascade [27] [8]. An optimal dressing must integrate three fundamental properties: superior biocompatibility to interact with biological systems without eliciting adverse responses, effective moisture retention to maintain a hydrated microenvironment conducive to cellular processes, and adequate oxygen permeability to ensure tissue respiration and support various healing phases [33] [34]. Hydrogels, three-dimensional hydrophilic polymer networks, have emerged as a leading class of biomaterials in this domain due to their innate ability to be engineered for these properties, mimicking the native extracellular matrix (ECM) and providing a supportive scaffold for tissue regeneration [27] [35]. This document outlines the core properties of ideal wound dressings, supported by quantitative data, and provides detailed experimental protocols for their evaluation in the context of hydrogel-based wound healing applications.

Core Properties of an Ideal Wound Dressing

The following table summarizes the key properties, their functional significance, and associated quantitative metrics for an ideal wound dressing, with a specific focus on hydrogel-based systems.

Table 1: Key Properties of an Ideal Hydrogel-Based Wound Dressing

| Property | Functional Significance in Wound Healing | Key Quantitative Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Biocompatibility | Prevents adverse immune reactions, supports cell adhesion, proliferation, and integration with host tissue [27] [8]. | >90% cell viability in ISO 10993-5 cytotoxicity tests [27]; Minimal inflammatory cytokine release (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) in vitro [33]. |

| Moisture Retention | Maintains a moist wound bed, facilitates autolytic debridement, promotes cell migration, and reduces patient pain [36] [35]. | High Equilibrium Water Content (EWC > 80%) [36]; Water Vapor Transmission Rate (WVTR) of 2000-2500 g/m²/day [34]. |

| Oxygen Permeability | Supports aerobic cellular respiration, neutrophil activity, and angiogenesis while inhibiting anaerobic bacterial growth [33] [34]. | Oxygen diffusion coefficient comparable to native skin (~2.5-5.0 x 10â»â¶ cm²/s) [33]. |

| Mechanical Properties | Provides structural integrity, conforms to wound contours, and withstands mechanical stress during patient movement [27] [30]. | Elastic modulus (E) matching native skin (0.1-20 MPa, depending on location); High elongation at break (>50%) [27]. |

| Bioactivity & Antimicrobial Protection | Actively prevents infection, modulates inflammation, and promotes vascularization and tissue regeneration [36] [30]. | Zone of inhibition >2 mm against common pathogens (e.g., S. aureus, P. aeruginosa); Controlled release of growth factors (e.g., VEGF, FGF) [30]. |

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Hydrogel Dressing Properties

The following protocols provide standardized methodologies for assessing the critical properties of hydrogel-based wound dressings.

Protocol for Biocompatibility and Cytotoxicity Assessment (ISO 10993-5)

This protocol evaluates the in vitro cytotoxicity of hydrogel extracts using a fibroblast cell line.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Cell Line: L929 mouse fibroblast cells (ATCC CCL-1)

- Culture Medium: Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin.

- Viability Assay: MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) reagent.

- Extraction Medium: Serum-free DMEM.

- Positive Control: Latex extract.

- Negative Control: High-density Polyethylene (HDPE) extract.

Methodology:

- Hydrogel Extract Preparation: Sterilize the hydrogel sample (e.g., UV irradiation for 30 minutes per side). Using aseptic technique, place a 3 cm² sample per mL of extraction medium in a sterile container. Incubate at 37°C for 24 hours under agitation. Filter the extract through a 0.22 µm filter.

- Cell Seeding: Seed L929 fibroblasts in a 96-well plate at a density of 1 x 10ⴠcells per well in complete culture medium. Incubate for 24 hours at 37°C in a 5% CO₂ atmosphere to form a near-confluent monolayer.

- Sample Exposure: Aspirate the culture medium from the wells. Add 100 µL of the hydrogel extract, positive control, and negative control to respective wells (n=6 per group). Include wells with culture medium only as a blank. Incubate the plate for another 24 hours.

- MTT Assay and Analysis: Add 10 µL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL in PBS) to each well. Incubate for 4 hours. Carefully remove the medium and add 100 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to solubilize the formed formazan crystals. Measure the absorbance of each well at 570 nm using a microplate reader.

- Data Calculation: Calculate the percentage of cell viability using the formula:

- Cell Viability (%) = (Absorbance of Test Sample / Absorbance of Negative Control) x 100 A cell viability greater than 90% relative to the negative control is considered non-cytotoxic [27].

Protocol for Moisture Retention and Water Vapor Transmission Rate

This protocol determines the hydrogel's water content and its ability to manage moisture at the wound interface.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS): 0.01 M, pH 7.4.

- Desiccant: Anhydrous calcium chloride.

- Test Setup: Payne cup or similar permeability cup.

Methodology:

- Equilibrium Water Content (EWC):

- Weigh the dry hydrogel sample (Wdry).

- Submerge the sample in PBS at room temperature until swelling equilibrium is reached (no further weight increase).

- Carefully remove the sample, blot gently with filter paper to remove surface water, and weigh immediately (Wwet).

- Calculate EWC using the formula:

- EWC (%) = [(Wwet - Wdry) / W_wet] x 100

- Water Vapor Transmission Rate (WVTR):

- Fill a Payne cup with 10 mL of distilled water.

- Secure the hydrogel sample (of known surface area, A) over the cup opening, ensuring a tight seal.

- Weigh the entire assembly (Winitial) and place it in a controlled environment (e.g., 37°C, 20% relative humidity).

- Weigh the assembly at 24-hour intervals for 3 days (Wfinal).

- Calculate WVTR using the formula:

- WVTR (g/m²/day) = [(Winitial - Wfinal) / (A * T)] where T is the time in days. An ideal range for wound healing is 2000-2500 g/m²/day [34].

Protocol for Oxygen Permeability Measurement

This protocol uses a simplified diffusion cell apparatus to assess the oxygen permeability of hydrogel films.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Oxygen-Sensitive Probe: Tris(2,2'-bipyridyl)dichlororuthenium(II) hexahydrate.

- Oxygen-Free Nitrogen Gas.

- Sensing Film: Hydrogel film incorporated with the oxygen-sensitive probe.

Methodography:

- Apparatus Setup: Construct a two-chamber diffusion cell where the hydrogel film is mounted as a barrier between a donor chamber (initially filled with nitrogen) and a receiver chamber (filled with PBS saturated with air).

- Data Acquisition: Monitor the partial pressure of oxygen (pOâ‚‚) in the receiver chamber over time using a dissolved oxygen meter or via the fluorescence quenching of the oxygen-sensitive probe.

- Data Analysis: The oxygen permeability coefficient (P) is calculated from the steady-state flux (J) of oxygen across the film, using Fick's first law:

- J = P * (Δp / L) where Δp is the difference in oxygen partial pressure across the film and L is the film thickness. The diffusion coefficient (D) can be derived from the time lag method.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Hydrogel Wound Dressing Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Polymers (e.g., Alginate, Chitosan, Collagen) | Serve as the base scaffold for hydrogels, providing inherent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and bioactivity [27] [8]. | Fabrication of ECM-mimicking scaffolds; creation of hemostatic and antimicrobial dressings [36]. |

| Synthetic Polymers (e.g., PVA, PEG, PLGA) | Provide tunable mechanical strength, controlled degradation rates, and structural stability to the hydrogel network [27] [37]. | Synthesis of high-strength, durable hydrogels; development of stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems [30]. |

| Crosslinkers (e.g., Genipin, EDC/NHS, Glutaraldehyde) | Form stable 3D networks by creating covalent or ionic bonds between polymer chains, determining hydrogel stability and mechanics [30]. | Controlling the swelling ratio, mechanical integrity, and degradation profile of the fabricated hydrogel [27]. |

| Bioactive Agents (e.g., Growth Factors, Antimicrobial Nanoparticles) | Confer advanced therapeutic functions such as promoting angiogenesis or preventing/treating infections [36] [30]. | Engineering drug-eluting dressings for chronic wounds; creating scaffolds with enhanced regenerative capacity [8]. |

| Cell Lines (e.g., L929 Fibroblasts, HaCaT Keratinocytes) | In vitro models for assessing biocompatibility, cytotoxicity, and the ability of the dressing to support cellular functions critical to healing [27] [33]. | Standardized cytotoxicity testing (ISO 10993-5); migration (scratch) assays to simulate re-epithelialization [27]. |

| PC Azido-PEG11-NHS carbonate ester | PC Azido-PEG11-NHS carbonate ester, MF:C42H68N6O21, MW:993.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Benzenedimethanamine-diethylamine | Benzenedimethanamine-diethylamine, MF:C16H32N6, MW:308.47 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualizing the Hydrogel Design Pathway for Ideal Wound Dressings

The following diagram illustrates the logical pathway and key considerations for designing an advanced hydrogel wound dressing that meets the core requirements of biocompatibility, moisture retention, and oxygen permeability.

Hydrogel Design and Evaluation Workflow

This workflow outlines the multi-faceted approach to designing and testing advanced hydrogel dressings, from material selection through to functional application, ensuring all key properties are addressed.

From Lab to Bedside: Fabrication Techniques and Multifunctional Applications

Advanced manufacturing technologies are revolutionizing the design and production of hydrogel-based wound dressings, enabling unprecedented control over material architecture and functionality. These techniques facilitate the creation of personalized, biomimetic constructs that actively support the wound healing process [6]. Traditional wound dressings often act as passive barriers, but advanced manufacturing allows for the development of active systems capable of integrated diagnostics and targeted therapy [6]. This document outlines application notes and experimental protocols for three key advanced manufacturing techniques—3D printing, electrospinning, and micromachining—within the context of hydrogel fabrication for wound healing applications.

Comparative Analysis of Advanced Manufacturing Techniques

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and applications of 3D printing, electrospinning, and micromachining in fabricating hydrogels for wound healing.

Table 1: Comparison of Advanced Manufacturing Techniques for Hydrogel-Based Wound Dressings

| Technique | Typical Resolution | Key Advantages | Common Materials | Primary Wound Healing Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D Printing | Micrometer to millimeter scale [38] | High architectural control, patient-specific customization, integration of bioactive components [6] [39] | GelMA, Alginate, PEGDA, HAMA, cellulose derivatives [39] [38] | Custom-shaped dressings for irregular wounds, scaffolds with controlled pore networks for tissue infiltration [6] |

| Electrospinning | Nanometer to micrometer scale (fiber diameter) [40] | High surface area-to-volume ratio, ECM-mimetic nanofibrous structure, efficient drug loading [40] [41] | PCL, Chitosan, Gelatin, Silk fibroin, hybrid polymers [40] | Nanofibrous membranes for exudate management, controlled release of antimicrobials and growth factors [40] [41] |

| Micromachining | Sub-micrometer to micrometer scale [6] | High-precision surface patterning, creation of microfluidic channels and sensor arrays [6] | Various natural and synthetic hydrogels [6] | Integrated biosensors, microneedles for transdermal monitoring, microfluidic systems for biomarker detection [6] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Digital Light Processing (DLP) 3D Printing of GelMA-Based Hydrogel Dressings

This protocol describes the fabrication of high-resolution, micropatterned hydrogel patches using DLP 3D printing, suitable for creating personalized wound dressings with enhanced adhesion and antioxidant properties [38].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for DLP 3D Printing of Hydrogel Dressings

| Reagent | Function | Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gelatin Methacrylate (GelMA) | Primary bioink component providing ECM-mimetic properties and tunable mechanical strength [38] | Synthesized from Type A gelatin (≈300 g Bloom); degree of functionalization should be characterized via 1H NMR [38] |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) | Co-monomer to enhance mechanical properties and printability [38] | Molecular weight (n ≈ 14); helps improve mechanical integrity without significantly compromising cell viability [38] |

| Lithium phenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl) phosphinate (LAP) | Photoinitiator for crosslinking under light exposure [38] | Concentration typically 0.5-1.0% (w/v); enables rapid polymerization under 405 nm light [38] |

| Tartrazine (AY 23) | Photoabsorber to control light penetration and enhance printing resolution [38] | Concentration ~0.03% (w/v); prevents over-penetration of UV light, enabling finer feature resolution [38] |

| Gallic Acid (GA) | Functionalization agent for antioxidant activity and improved adhesiveness [38] | Natural polyphenol; post-printing functionalization via EDC/NHS chemistry to scavenge ~80% of free radicals within 4 hours [38] |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Bioink Preparation: a. Prepare a 10% (w/v) solution of GelMA in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 50°C until fully dissolved [38]. b. Add PEGDA co-monomer at a ratio of 1:1 to 1:3 (GelMA:PEGDA) to enhance mechanical properties [38]. c. Incorporate LAP photoinitiator at 0.5% (w/v) and Tartrazine at 0.03% (w/v) into the polymer solution. Mix thoroughly and protect from light [38]. d. Filter the bioink through a 0.22 µm sterile filter if aseptic processing is required.

DLP Printing Process: a. Design the scaffold model using CAD software and convert to an appropriate file format (e.g., STL) [39]. b. Transfer the bioink to the printing reservoir and maintain at 25°C during printing. c. Set printing parameters: layer thickness of 50-100 µm, exposure time of 10-30 seconds per layer depending on light intensity [38]. d. Initiate the printing process. The constructed layers will be photocrosslinked sequentially according to the digital design.

Post-Printing Processing: a. After printing, rinse the constructs with sterile PBS to remove any uncrosslinked material. b. For functionalization with Gallic Acid (GA), prepare a 2 mg/mL GA solution in MES buffer (pH 5.5) with EDC/NHS crosslinkers [38]. c. Immerse the printed constructs in the GA solution for 4-6 hours at room temperature with gentle agitation. d. Wash thoroughly with PBS to remove any unreacted compounds.

Quality Control and Characterization: a. Assess the swelling capacity by measuring weight change after immersion in PBS (typically 200-300% achieved) [39]. b. Evaluate mechanical properties via rheometry to confirm storage modulus (G') values appropriate for wound dressing applications [38]. c. Perform in vitro cytocompatibility testing using fibroblast cell lines (e.g., NHDF) according to ISO 10993-5 standards [38].

Protocol 2: Electrospinning of Nanofibrous Wound Dressing Membranes

This protocol outlines the fabrication of nanofibrous wound dressing membranes using electrospinning technology, creating structures that mimic the native extracellular matrix (ECM) for enhanced wound healing [40] [41].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Electrospinning Nanofibrous Dressings

| Reagent | Function | Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | Synthetic polymer backbone providing mechanical strength and controlled biodegradability [40] | Molecular weight ~80,000 Da; provides excellent spinnability and tunable degradation profile [40] |

| Chitosan | Natural polymer imparting antimicrobial activity and biocompatibility [40] | Degree of deacetylation >85%; enhances bioactivity but may require blending with other polymers for improved spinnability [40] |

| Vermiculite Nanoclay | Functional additive to promote angiogenesis and collagen deposition [40] | Two-dimensional nanovermiculite; particularly beneficial for diabetic foot ulcer applications [40] |

| Antimicrobial Agents (e.g., Vanillin) | Bioactive compounds for infection control [39] | Natural antimicrobials like vanillin can be loaded in nanomicelles (2-5% w/w) and incorporated into fibers to avoid bacterial resistance [39] |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Polymer Solution Preparation: a. Prepare a 10-15% (w/v) PCL solution in a 7:3 (v/v) mixture of chloroform and methanol [40]. b. For blended systems, dissolve chitosan in dilute acetic acid (1-2% v/v) and mix with PCL solution at appropriate ratios (typically 3:1 to 1:1 PCL:chitosan) [40]. c. Incorporate functional additives such as vermiculite nanoclay (1-3% w/w) or drug-loaded nanomicelles (2-5% w/w) [40] [39]. d. Stir the solution for 12-24 hours at room temperature to ensure complete homogenization.

Electrospinning Setup: a. Load the polymer solution into a syringe fitted with a metallic needle (gauge 18-22). b. Set the flow rate to 0.5-2.0 mL/hour using a syringe pump. c. Apply high voltage (10-25 kV) between the needle tip and the collector. d. Maintain a working distance of 10-20 cm between the needle and collector. e. Use a rotating mandrel or flat collector based on the desired fiber alignment.

Fiber Collection and Post-processing: a. Collect fibers for 2-6 hours depending on the desired membrane thickness. b. Vacuum-dry the collected nanofibrous membranes at 40°C for 24 hours to remove residual solvents. c. For crosslinking, expose chitosan-containing fibers to glutaraldehyde vapor or UV irradiation as needed.

Characterization and Sterilization: a. Analyze fiber morphology by scanning electron microscopy (SEM); target fiber diameters of 100-500 nm [40]. b. Evaluate porosity, which should be >80% for optimal exudate management and gas exchange [41]. c. Perform antibacterial efficacy testing against common pathogens (e.g., S. aureus and E. coli) following ASTM E2149 standards [39]. d. Sterilize using gamma irradiation or ethylene oxide gas before in vivo applications.

Protocol 3: Micromachining of Hydrogel-Based Sensor Arrays

This protocol describes the use of micromachining techniques to create integrated sensor arrays within hydrogel matrices for real-time monitoring of wound biomarkers, enabling closed-loop wound management systems [6].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents for Micromachined Hydrogel Sensors

| Reagent | Function | Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Additives (MXene, PEDOT:PSS) | Enable real-time sensing of biophysical and biochemical signals [6] | MXene (Ti₃C₂Tₓ) provides high conductivity and biocompatibility; PEDOT:PSS offers stable electrochemical properties [6] |

| Stimuli-Responsive Polymers (PNIPAAm) | Provide temperature-dependent swelling behavior for controlled drug release [6] | Poly(N-isopropyl acrylamide) exhibits reversible volume phase transition at ~32°C; useful for thermo-responsive drug delivery [6] |

| pH-Sensitive Dyes (e.g., Spiropyran) | Enable visual or spectroscopic pH monitoring in wound environment [6] | Spiropyran units enable on-demand antimicrobial activation via photochromism; carboxyl groups provide pH-dependent swelling [6] |

| Enzyme Systems (Glucose Oxidase/Catalase) | Facilitate biochemical sensing and autonomous therapeutic responses [42] | GOx/CAT enzyme pair consumes glucose and regulates local pH; enables feedback-regulated drug release in diabetic wounds [42] |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Hydrogel Formulation for Micropatterning: a. Prepare a base hydrogel precursor solution (e.g., 5-10% GelMA or hybrid polymers) in PBS [6] [38]. b. Incorporate conductive additives (0.5-2% w/w MXene or 3-5% w/w PEDOT:PSS) with thorough mixing and sonication to ensure uniform dispersion [6]. c. Add stimuli-responsive components as required: PNIPAAm (5-10% w/w) for thermoresponsiveness, or spiropyran (0.1-0.5% w/w) for photoresponsive applications [6]. d. For enzymatic feedback systems, incorporate GOx (0.01-0.6 g/L) and catalase (0.08 g/L) into OSA-GEL hydrogels [42].

Micromachining Process: a. Soft Lithography: Create polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) stamps with desired microchannel patterns (width: 50-200 µm) [6]. b. Pour hydrogel precursor solution onto the patterned substrate or stamp. c. Apply appropriate crosslinking method: UV exposure (for photopolymerizable systems) or ionic crosslinking (for alginate-based systems). d. Laser Ablation: Use focused laser systems for direct writing of microfluidic channels or sensor patterns in pre-formed hydrogel sheets. e. Photolithography: For high-resolution features, use photomasks with UV exposure to define micro-scale patterns in photopolymerizable hydrogels.

Sensor Integration and Calibration: a. Integrate electrodes for electrochemical sensing of pH, glucose, or other biomarkers using screen-printed or micromachined electrode arrays [6]. b. Calibrate pH sensors in buffer solutions across the physiologically relevant range (pH 5.0-8.5) [6] [42]. c. For glucose sensors, calibrate against standard solutions in the range of 1-4 g/L (representing normal to diabetic glucose levels) [42]. d. Validate temperature response for thermoresponsive systems between 25-40°C.

Performance Validation: a. Test sensor response time and sensitivity to target biomarkers in simulated wound fluid. b. Evaluate mechanical compliance of the integrated sensor-hydrogel system to ensure compatibility with skin movement. c. Assess operational stability over 7-14 days in conditions mimicking the wound environment. d. Perform in vitro biocompatibility testing according to ISO 10993-5 standards.

Integrated Manufacturing Strategy for Advanced Wound Care

The convergence of these advanced manufacturing techniques enables the development of next-generation wound dressings with integrated diagnostic and therapeutic functions. A promising approach involves combining 3D-printed structural frameworks with electrospun functional layers and micromachined sensor arrays to create truly intelligent wound management systems [6]. For instance, a 3D-printed alginate-fucoidan scaffold can provide the macroscopic structure and mechanical support [39], while electrospun nanofibers incorporated with antimicrobial nanomicelles offer enhanced infection control [39], and micromachined pH/glucose sensors enable real-time monitoring of wound status [6] [42]. Such integrated systems represent the future of personalized wound care, capable of dynamically adapting treatment strategies based on continuous feedback from the wound microenvironment.

The management of complex wounds, particularly chronic wounds such as diabetic foot ulcers and pressure ulcers, presents a formidable global health challenge, affecting over 40 million patients annually and incurring healthcare costs exceeding $50 billion per year worldwide [1]. Traditional wound dressings, including gauze and hydrocolloids, often fail to address the complex microenvironment of chronic wounds, leading to prolonged healing times and increased risk of complications [1]. In recent years, stimuli-responsive and self-healing hydrogels have emerged as a promising class of biomaterials for advanced wound management due to their unique ability to dynamically adapt to the wound environment and autonomously repair damage [1] [43].

These "smart" hydrogels represent a significant advancement over conventional wound dressings. Their high water content mimics the natural extracellular matrix (ECM), providing a moist environment that facilitates cell proliferation and migration [43] [44]. More importantly, their inherent responsiveness to specific physiological or external stimuli—such as pH, temperature, enzymes, or reactive oxygen species (ROS)—enables precise regulation of therapeutic agent release and functional adaptation [43] [45]. When combined with self-healing capabilities that restore structural integrity after damage, these materials offer unprecedented potential for revolutionizing wound care and regenerative medicine [7] [46].

This application note provides a comprehensive technical resource for researchers and scientists working in hydrogel fabrication for wound healing applications. We summarize key quantitative performance data, detail essential experimental protocols, visualize critical signaling pathways and mechanisms, and catalog fundamental research reagents necessary for advancing the development of next-generation smart wound dressings.

Mechanisms and Performance Characteristics

Stimuli-Responsive Mechanisms in Hydrogels

Stimuli-responsive hydrogels are engineered to undergo reversible or irreversible physical and/or chemical changes in response to specific environmental cues present in wound microenvironments [43]. The table below summarizes the primary stimulus types, their activation triggers in wounds, and the resultant hydrogel responses that facilitate healing.

Table 1: Characteristics and Wound Healing Applications of Stimuli-Responsive Hydrogels

| Stimulus Type | Trigger in Wound Environment | Hydrogel Response | Therapeutic Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH [45] | Alkaline shift (pH ~7.4-9.0) in chronic wounds [45] | Swelling/contraction or degradation; controlled drug release [45] | Targeted antimicrobial delivery; infection control [43] |

| Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) [43] | Elevated oxidative stress in chronic wounds [43] | Oxidation-triggered disassembly; release of antioxidants or drugs [43] | Scavenging excess ROS; reducing oxidative damage [43] |

| Enzyme [43] | Overexpressed matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [43] | Enzyme-sensitive degradation; on-demand drug release [43] | Precise drug delivery at the site of active tissue remodeling [43] |

| Temperature [47] | Skin surface temperature (~32°C) [47] | Sol-gel transition upon contact with body [47] | Facilitates easy application and conformal wound coverage [47] |

| Light [43] | External NIR/UV application [43] | Photothermal or photochemical reactions [43] | Spatiotemporally controlled therapy; biofilm disruption [43] |

Self-Healing Mechanisms and Performance Metrics

Self-healing hydrogels restore their structural integrity and functionality after damage through dynamic, reversible cross-linking mechanisms [7] [46]. These are broadly classified into dynamic covalent bonds and non-covalent interactions, each offering distinct advantages for wound healing applications.

Table 2: Self-Healing Mechanisms and Representative Performance Data