Advanced Drug-Eluting Stent Coatings: Techniques, Applications, and Future Directions

This comprehensive review explores the evolving landscape of drug-eluting stent (DES) coatings and application techniques, addressing critical needs for researchers and development professionals.

Advanced Drug-Eluting Stent Coatings: Techniques, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the evolving landscape of drug-eluting stent (DES) coatings and application techniques, addressing critical needs for researchers and development professionals. The article systematically examines foundational principles of DES technology, detailing coating materials, drug mechanisms, and stent platform requirements. It analyzes current methodological approaches including coating application techniques, polymer-based and polymer-free systems, and advanced drug delivery mechanisms. The content further addresses troubleshooting and optimization strategies for challenges like stent thrombosis and restenosis, incorporating computational modeling and material innovations. Finally, it validates approaches through clinical outcomes analysis and comparative assessment of different DES generations, providing a thorough evidence base for technology development and clinical application.

The Evolution of Drug-Eluting Stents: From Concept to Modern Coatings

The development of the first-generation drug-eluting stent (DES) marked a revolutionary advancement in interventional cardiology, fundamentally changing the treatment paradigm for coronary artery disease (CAD). Before its advent, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was limited by the significant challenge of in-stent restenosis (ISR), a process of re-narrowing of the treated artery [1]. Bare-metal stents (BMS), introduced in the mid-1980s, represented an improvement over plain old balloon angioplasty (POBA) by effectively addressing acute vessel closure and elastic recoil [2] [1]. However, the metallic scaffold provoked a healing response characterized by neointimal hyperplasia—an excessive proliferation of smooth muscle cells—which led to ISR rates of 15-30% [1]. This pathological process created a critical need for innovative solutions that could inhibit this hyperproliferative response while maintaining vessel patency, thereby setting the stage for the groundbreaking development of first-generation DES.

The Evolution of Stent Technology: From BMS to First-Generation DES

The Bare-Metal Stent Era

Bare-metal stents were constructed from stainless steel and provided radial strength to mechanically scaffold coronary arteries open after angioplasty [1]. By preventing vessel recoil and negative remodeling, they represented a significant step forward from POBA. Nonetheless, their deployment caused injury to the vessel wall, triggering a cascade of inflammatory and proliferative responses that resulted in excessive tissue growth through the stent struts [1]. This neointimal hyperplasia necessitated repeat revascularization procedures in a substantial proportion of patients, with studies reporting restenosis rates of 15-35% [2]. This limitation highlighted the insufficiency of a purely mechanical approach and underscored the need for a biological solution to modulate the healing response.

The Conceptual Leap: Local Drug Delivery

The fundamental innovation behind the first-generation DES was the concept of localized anti-proliferative drug delivery to the vessel wall [1]. Researchers hypothesized that by coating stents with pharmaceutical agents that could inhibit smooth muscle cell proliferation, they could disrupt the pathway responsible for neointimal hyperplasia while minimizing systemic side effects. This required a sophisticated combination of three components: a metallic platform, an anti-proliferative drug, and a polymer coating to control drug release [1]. The polymer served as a drug reservoir, allowing for controlled elution kinetics that could provide therapeutic drug levels during the critical period of healing after stent implantation.

Table 1: Key Components of First-Generation Drug-Eluting Stents

| Component | Description | Examples in First-Generation DES |

|---|---|---|

| Metallic Platform | Base stent structure providing radial strength | Stainless steel (>100 μm strut thickness) [1] |

| Polymer Coating | Drug carrier vehicle controlling release kinetics | Non-degradable synthetic polymers (e.g., polyethylene-co-vinyl acetate, poly-n-butyl methacrylate) [1] |

| Anti-Proliferative Drug | Pharmaceutical agent inhibiting neointimal hyperplasia | Sirolimus, Paclitaxel [1] |

Mechanism of Action: Cytostatic vs. Cytotoxic Approaches

First-generation DES utilized two distinct classes of anti-proliferative agents with different mechanisms of action:

Sirolimus (and its analogues) functioned as cytostatic agents by inhibiting the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a key regulatory kinase in the cell cycle. This blockade prevented cell cycle progression from the G1 to S phase, thereby suppressing smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration without causing cell death [1].

Paclitaxel operated as a cytotoxic agent by stabilizing cellular microtubules, thereby disrupting normal microtubule dynamics during cell division. This mechanism caused M-phase arrest in the cell cycle, ultimately leading to cell death [2] [1].

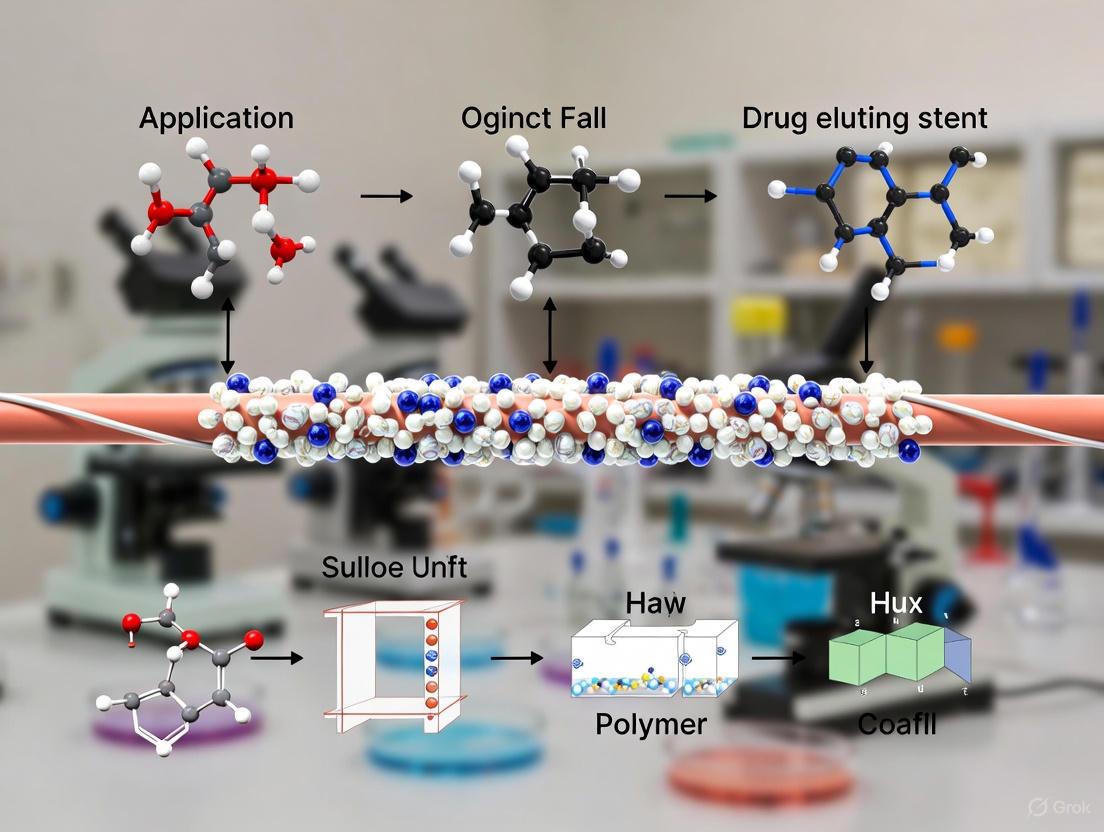

The diagram below illustrates the signaling pathways and mechanisms of action for these two primary drugs used in first-generation DES:

Clinical Evidence and Outcomes

The introduction of first-generation DES demonstrated remarkable success in addressing the limitation of restenosis that plagued BMS. Clinical trials consistently showed that DES significantly reduced restenosis to less than 10%, a substantial improvement over the 15-30% rates observed with BMS [1]. This reduction in anatomical restenosis translated into meaningful clinical benefits, with a pronounced decrease in target lesion revascularization (TLR) procedures [1]. The ability to maintain vessel patency with fewer repeat interventions established DES as the new standard of care in percutaneous coronary intervention.

However, longer-term follow-up revealed an unanticipated concern: very late stent thrombosis (VLST), occurring more than one year after implantation [3]. This serious complication was attributed to delayed endothelialization and polymer-induced inflammation, as the permanent polymer coatings in first-generation DES sometimes provoked hypersensitivity reactions that impaired the normal healing process [1]. Histopathological studies indicated that these polymer coatings contributed to delayed vascular healing, which was associated with the increased risk of VLST [1].

Table 2: Comparative Clinical Outcomes of BMS vs. First-Generation DES

| Outcome Measure | Bare-Metal Stents (BMS) | First-Generation DES | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-Stent Restenosis | 15-30% [1] | <10% [1] | Dramatic reduction in re-narrowing |

| Target Lesion Revascularization | Higher rates [1] | Significantly reduced [1] | Fewer repeat procedures |

| Stent Thrombosis (Early) | Comparable | Comparable | Similar early safety profile |

| Very Late Stent Thrombosis | Lower incidence | Increased risk [1] | New safety concern with DES |

| Need for Dual Antiplatelet Therapy | Shorter duration | Prolonged duration required | Impact on bleeding risk |

A 14-year follow-up study provided intriguing long-term perspectives on this technological evolution. While DES demonstrated significantly lower major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) at 1-year follow-up compared to BMS (3 vs. 10 events, p=0.04), this benefit narrowed over time, with event rates becoming similar at 5, 10, and 14 years [4]. This long-term data suggests that while first-generation DES excelled at addressing the short- to medium-term challenge of restenosis, their advantage over BMS diminished in the very long term.

Experimental Protocols for DES Evaluation

In Vitro Drug Release Kinetics Profiling

Objective: To quantify and characterize the release kinetics of anti-proliferative drugs from stent coatings under simulated physiological conditions.

Methodology:

- Stent Preparation: Place individual DES units (n=6 per group) into separate vessels containing phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.5% Tween 20 at pH 7.4, maintained at 37°C [1].

- Sampling Protocol: Withdraw and replace release medium at predetermined time points (1, 4, 8, 24, 48, 72 hours, then weekly for 90 days).

- Drug Quantification: Analyze samples using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with UV detection to determine cumulative drug release.

- Kinetic Modeling: Fit release data to mathematical models (Higuchi, Korsmeyer-Peppas) to characterize release mechanisms.

Data Analysis: Calculate cumulative drug release profiles and determine burst release percentage (first 24 hours) versus sustained release phase.

Histomorphometric Analysis of Vessel Healing

Objective: To quantitatively assess neointimal suppression and vascular healing responses in pre-clinical models.

Methodology:

- Animal Implantation: Deploy test and control stents in appropriate animal models (porcine coronary model is standard).

- Tissue Harvest: Collect stented arterial segments at predetermined endpoints (28, 90, and 180 days).

- Processing and Sectioning: Fix vessels in formalin, embed in methylmethacrylate resin, and section using rotary microtome.

- Staining and Analysis: Perform hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and elastic van Gieson (EVG) staining; analyze using digital morphometry.

Key Parameters:

- Neointimal Area: (Internal elastic lamina area - luminal area)

- Neointimal Thickness: Measured at each strut location

- Inflammation Score: 0-3 scale based on inflammatory cells around struts

- Endothelialization Score: Percentage of luminal surface covered by endothelium

The experimental workflow for evaluating stent performance integrates both in vitro and in vivo assessments, as visualized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for DES Coating and Application Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in DES Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sirolimus (Rapamycin) | mTOR inhibitor; cytostatic anti-proliferative [1] | Requires specific solvent systems for coating; sensitive to degradation |

| Paclitaxel | Microtubule stabilizer; cytotoxic anti-proliferative [2] [1] | Different mechanism than sirolimus; challenges with controlled release |

| Polymer Matrices (PEVA, PBMA) | Drug reservoir controlling release kinetics [1] | Early non-degradable polymers associated with late inflammation |

| Stainless Steel Platforms | Stent backbone providing radial strength [1] | Thicker struts (>100μm) compared to later generations |

| Chromatography Solvents (HPLC grade) | Drug quantification in release kinetics studies | Essential for accurate measurement of drug elution profiles |

| Cell Culture Media | Biocompatibility testing with endothelial/smooth muscle cells | Assess cytotoxicity and cellular responses to elution products |

| Histology Stains (H&E, EVG) | Tissue response evaluation in pre-clinical models | Critical for quantifying neointimal formation and inflammation |

| Thalidomide-O-C8-COOH | Thalidomide-O-C8-COOH, MF:C22H26N2O7, MW:430.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fmoc-Gly-Gly-Phe-OtBu | Fmoc-Gly-Gly-Phe-OtBu, MF:C32H35N3O6, MW:557.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The development of first-generation drug-eluting stents represented a paradigm shift in interventional cardiology, successfully addressing the formidable challenge of restenosis that had limited bare-metal stents. By combining mechanical scaffolding with controlled biological modulation through local drug delivery, first-generation DES achieved remarkable reductions in target lesion revascularization, establishing a new standard of care [1]. However, the emergence of very late stent thrombosis related to polymer biocompatibility issues highlighted the delicate balance between efficacy and safety in vascular implant technology [1].

These historical milestones and their limitations directly informed subsequent technological evolution, driving the development of second-generation DES with improved alloys, more biocompatible polymers, and alternative anti-proliferative agents [3] [1]. The first-generation DES story exemplifies how a transformative medical technology must continuously evolve based on long-term clinical evidence, balancing innovation with thoughtful consideration of unintended consequences to optimize patient outcomes in coronary artery disease management.

Drug-eluting stents (DES) represent a cornerstone technology in the treatment of coronary and peripheral artery disease, achieving their therapeutic effect through the sophisticated integration of three core components: a stent platform, one or more pharmacological agents, and a coating system that controls drug release [5] [6]. The careful selection and engineering of these components are critical for balancing the efficacy of preventing in-stent restenosis (ISR) with the safety profile of the implanted device [7]. The evolution from first-generation DES, which were plagued by issues of polymer-induced inflammation and late stent thrombosis, has led to advanced coating technologies including biodegradable polymers, polymer-free designs, and novel drug delivery mechanisms [3] [5]. This document provides a detailed technical overview of these key coating components and outlines standardized experimental protocols for their evaluation, serving as a practical resource for researchers and development professionals in the field.

Key Coating Components: Composition and Function

The performance of a DES is governed by the interplay between its metallic platform, the antiproliferative drug, and the polymer matrix that controls drug release. The following sections and tables detail the characteristics and options for each component.

Stent Platforms

The stent platform provides the mechanical scaffold to maintain vessel patency. The base material and structural design directly influence deliverability, radial strength, and long-term safety.

Table 1: Key Stent Platform Materials and Properties

| Material | Key Properties | Advantages | Limitations/Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cobalt-Chromium (CoCr) [3] | High radial strength, good radio-opacity | Allows for thinner strut designs (<70 µm), improved deliverability [3] | Permanent metallic implant |

| Platinum-Chromium (PtCr) [3] | Enhanced radial strength, high radio-opacity | Superior visibility under fluoroscopy | Permanent metallic implant |

| Nitinol (Nickel-Titanium) [6] | Superelasticity, shape-memory, excellent flexibility | Ideal for peripheral arteries with movement (e.g., femoropopliteal) [6] | Potential nickel toxicity concerns; requires stable oxide layer for biocompatibility [6] |

| Magnesium Alloys [3] [5] | Biocorrodible, degradable | Potential for complete resorption, restoring vasomotion [3] | Radial strength and degradation kinetics must be carefully controlled [5] |

Pharmacological Agents

The drugs eluted from DES are primarily cytostatic agents that inhibit smooth muscle cell (SMC) proliferation to prevent neointimal hyperplasia and ISR.

Table 2: Common Drugs Used in Drug-Eluting Stents

| Drug | Drug Class | Mechanism of Action | Release Kinetics & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sirolimus (and analogues like Everolimus, Zotarolimus) [3] [6] | Limus family (mTOR inhibitors) | Arrests the cell cycle in the G1 phase for both SMCs and endothelial cells [6] | Hydrophobic; requires polymer for sustained release. Efficacy depends on precise release kinetics [8]. |

| Paclitaxel [6] | Taxane | Stabilizes microtubules, inhibiting cell migration and division and inducing apoptosis [6] | Highly lipophilic; can be used on polymer-free platforms or with polymers. |

| 5-Fluorouracil (5FU) [9] | Antimetabolite | Inhibits thymidylate synthase, disrupting DNA and RNA synthesis. | Primarily investigated for drug-eluting stents in gastrointestinal cancers [9]. |

Polymer Coating Systems

Polymer coatings serve as a drug reservoir and control the release kinetics of the active agent. The trend is moving towards more biocompatible and biodegradable options to mitigate long-term risks.

Table 3: Types of Polymer Coatings for DES

| Polymer Type | Examples | Key Characteristics | Clinical Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Durable (Permanent) Polymer | PBMA, PVDF-HFP, SIBS [5] [8] | Remains on stent permanently after drug elution. | Earlier generations linked to chronic inflammation and late stent thrombosis [8]. Newer, more biocompatible versions (e.g., fluoropolymers) are widely used [5]. |

| Biodegradable (Bioresorbable) Polymer | PLGA, PCL, Poly(l-lactic acid) (PLLA) [3] [5] | Degrades over time (months), releasing drug and then disappearing. | Eliminates long-term polymer presence, potentially improving safety. Degradation rate must match drug release profile [3] [10]. |

| Polymer-Free | Microporous stents, nanoporous surfaces, reservoir-coated stents [3] [10] | Eliminates polymer entirely, using stent surface to hold and release drug. | Aims to avoid polymer-related adverse events entirely. Performance can be comparable to BP-DES in some studies [10]. |

| Advanced & Specialized Polymers | Biomimetic polymers, Gradient-release polymers, Polyurethane-silicone (PUS) elastomers [3] [9] | Designed to mimic ECM, provide variable drug release, or offer tailored elution profiles. | Represent next-generation innovations to further optimize healing and efficacy, including for non-vascular applications [3] [9]. |

Experimental Protocols for Coating Development and Evaluation

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments in the development and characterization of DES coatings.

Protocol: In Vitro Drug Release Kinetics

Objective: To quantify the rate and profile of drug release from a coated stent under simulated physiological conditions [6].

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Coated Stent Sample: Test DES unit.

- Dissolution Apparatus: USP Apparatus 4 (flow-through cell) or 7 (reciprocating holder) are recommended for stents [6].

- Dissolution Medium: Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) or a suitable medium that maintains sink conditions.

- Analytical Instrument: High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) system with UV-Vis or MS detector.

- Supporting Equipment: Heated water bath or jacket (37°C), sampling syringes with filters, volumetric flasks.

Procedure:

- Setup: Fill the dissolution vessel with a precise volume of pre-warmed (37°C) medium. Assemble the apparatus according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Stent Immersion: Place the coated stent into the vessel, ensuring it is fully immersed and freely moving, or fixed in a holder as per the apparatus design.

- Agitation: Start the agitation system (e.g., rotating paddle at 50-75 rpm) to ensure uniform hydrodynamics. Maintain temperature at 37°C throughout.

- Sampling: At predetermined time points (e.g., 1 h, 6 h, 24 h, 3 d, 7 d, 14 d, 30 d), withdraw a known aliquot (e.g., 1-2 mL) of the release medium. Replace with an equal volume of fresh, pre-warmed medium to maintain constant volume and sink conditions. Filter the sample through a 0.45 µm membrane filter.

- Analysis: Analyze the drug concentration in each sample using a validated HPLC-UV method. Calculate the cumulative amount of drug released at each time point.

- Data Processing: Plot the cumulative drug released (%) versus time to generate the release profile. Model the data using relevant kinetic models (e.g., Higuchi, Korsmeyer-Peppas) to understand the release mechanism.

Protocol: Coating Integrity and Morphology Analysis

Objective: To visually and quantitatively assess the surface morphology, uniformity, thickness, and potential defects of the coating before and after simulated use (e.g., expansion).

Materials:

- Microscopy: Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM).

- Sample Preparation: Sputter coater for applying a thin conductive layer (e.g., gold) for SEM.

- Stent Samples: Un-expanded coated stent, and stent expanded in a mock artery (e.g., silicone tube) to nominal pressure.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Carefully cut a representative section (e.g., 2-3 struts) from both the un-expanded and expanded stent.

- Mounting: Mount the stent segments on an SEM stub using conductive carbon tape to ensure electrical contact.

- Sputter Coating: Place the mounted samples in a sputter coater and apply a thin (5-10 nm) layer of gold/palladium to make the surface conductive.

- SEM Imaging: Transfer samples to the SEM chamber. Image the coating surface at various magnifications (e.g., 50x to 10,000x) to examine uniformity, texture, and the presence of cracks, webbing, or delamination. Obtain cross-sectional images to measure coating thickness.

- Image Analysis: Use image analysis software to measure coating thickness at multiple points and document any defects. Compare pre- and post-expansion images to assess durability.

Protocol: Biocompatibility and Hemocompatibility Assessment

Objective: To evaluate the potential for polymer coatings to induce thrombosis (blood clotting) and inflammatory responses.

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Test Samples: Coated stent segments or polymer-coated surfaces. Sterilize samples prior to testing.

- Biological Reagents: Fresh human platelet-rich plasma (PRP), whole blood, endothelial cell line (e.g., HUVEC), smooth muscle cell line (VSMC).

- Assay Kits: Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) assay kit, MTT/XTT cell viability kit, ELISA kits for inflammatory markers (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6).

Procedure (Key Assays):

- Platelet Adhesion Test: Incubate coated samples with PRP for a set time (e.g., 60 min). Gently rinse to remove non-adherent platelets. Fix and dehydrate the samples. Quantify adhesion via SEM imaging or using an LDH assay to measure platelet number.

- Hemolysis Assay: Incubate coated samples with diluted whole blood. After incubation, centrifuge and measure the hemoglobin released in the supernatant spectrophotometrically. Calculate the hemolysis ratio against controls.

- Cell Viability (Cytotoxicity): Prepare an extract of the coating by incubating it in cell culture medium. Culture relevant cells (HUVECs, VSMCs) and expose them to the extract. After 24-72 hours, measure cell viability using an MTT assay, which measures mitochondrial activity.

- In Vivo Evaluation (Animal Model): Implant the test DES and a control DES (e.g., a commercially approved device) in the coronary arteries of a porcine model. After a pre-determined period (e.g., 28-90 days), perform histopathological analysis of the stented segments to score endothelialization, inflammation, and fibrin deposition [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for DES Coating Research

| Category / Item | Specific Examples | Primary Function in R&D |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Coating Materials | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), Poly(n-butyl methacrylate) (PBMA), Poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) (PVDF-HFP) [5] [8] | Form the drug reservoir and control release kinetics; basis for biocompatibility testing. |

| Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) | Sirolimus, Everolimus, Zotarolimus, Paclitaxel [3] [6] | The therapeutic agent to be eluted; used for developing and validating drug loading and release methods. |

| Analytical Standards | USP Sirolimus RS, USP Paclitaxel RS | Certified reference standards for accurate quantification of drug content and release in analytical methods (HPLC). |

| Cell Lines for Cytocompatibility | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs), Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells (VSMCs) [6] | In vitro models to assess coating cytotoxicity and its specific effects on vascular cell types. |

| Animal Models for In Vivo Testing | Porcine (swine) coronary model [6] | The standard pre-clinical model for evaluating stent safety, efficacy, and vascular healing responses. |

| Characterization Equipment | Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM), High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) system | Essential for analyzing coating morphology, integrity, and drug quantification. |

| (S,R,S)-AHPC-C10-NH2 dihydrochloride | (S,R,S)-AHPC-C10-NH2 dihydrochloride, MF:C33H53Cl2N5O4S, MW:686.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Isamoltane hemifumarate | Isamoltane hemifumarate, CAS:55050-95-8; 874882-92-5, MF:C36H48N4O8, MW:664.8 | Chemical Reagent |

Anti-Proliferative Agents and Their Pharmacokinetics

Anti-proliferative agents are pharmaceuticals designed to inhibit abnormal cellular proliferation, a process central to pathologies such as in-stent restenosis (ISR) following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and cancer. In drug-eluting stents (DES) and drug-coated balloons (DCB), these agents are delivered locally to the vessel wall to suppress neointimal hyperplasia, which is the excessive growth of smooth muscle cells that leads to re-narrowing of the artery [2] [11]. The efficacy of these devices depends on a complex interplay between the pharmacological properties of the active drug, the vehicle or polymer used for delivery, the release kinetics, and the specific biological environment. This document details the primary anti-proliferative agents used in vascular devices, their pharmacokinetics, and associated experimental protocols, providing a framework for researchers developing next-generation coatings and application techniques.

Anti-Proliferative Drug Classes and Mechanisms of Action

The two dominant classes of anti-proliferative drugs used in vascular devices are the taxanes (e.g., paclitaxel) and the limus family (sirolimus and its analogs, such as everolimus and zotarolimus). Their mechanisms of action, while both anti-proliferative, target distinct cellular pathways as shown in the diagram below and summarized in the subsequent table.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Anti-Proliferative Agents in Vascular Devices

| Drug (Class) | Molecular Target | Cell Cycle Arrest | Primary Effect | Key Pharmacokinetic Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paclitaxel (Taxane) [2] [6] | β-tubulin | M-phase | Stabilizes microtubules, inhibiting cell division and migration | Highly lipophilic; requires excipients (e.g., shellac, BTHC) for arterial retention and transfer [2] |

| Sirolimus/Everolimus (Limus) [2] [12] | mTORC1 (via FKBP12) | G1-phase | Inhibits cell cycle progression and reduces inflammation | Poorer arterial wall penetration and shorter duration of action compared to paclitaxel [2] |

Pharmacokinetics and Drug Delivery from Stents and Balloons

The pharmacokinetic profile—encompassing drug release, tissue absorption, distribution, and retention—is a critical determinant of the safety and efficacy of DES and DCB.

Drug-Eluting Stents (DES)

DES technology has evolved through generations to optimize pharmacokinetics and biocompatibility. First-generation DES used durable polymers to elute drugs, which were associated with chronic inflammation and very late stent thrombosis due to the persistent presence of the polymer after drug elution [13] [14]. Second-generation DES featured more biocompatible durable polymers and improved stent platforms [14]. The current third-generation focuses on biodegradable polymers and polymer-free approaches, where the polymer carrier degrades and is resorbed after completing its drug-delivery function, thereby eliminating a nidus for long-term inflammation [13]. A novel advancement is the use of a crystalline drug form applied directly to the stent surface, which aims to provide a more controlled and sustained elution profile, reducing the initial "drug dumping" and local toxicity associated with polymer-based systems [14].

Drug-Coated Balloons (DCB)

DCBs offer a "leave nothing behind" alternative, delivering anti-proliferative drugs via a balloon catheter during brief inflation (typically 30-60 seconds). The key to their success is the rapid and effective transfer of the drug to the arterial wall. This is facilitated by hydrophilic matrix excipients (e.g., iopromide, urea) that enhance drug solubility and adherence to the vascular wall [2]. Paclitaxel is the predominant agent used in DCBs due to its high lipophilicity and rapid cellular uptake, which enable durable tissue effects from a single, short exposure [2]. While sirolimus-coated balloons face challenges due to the drug's poorer penetration and shorter tissue residence time, newer formulations using nanocarrier technology (e.g., MagicTouch SCB) are being developed to overcome these limitations [2].

Experimental Protocols for Coating Characterization and Performance

Robust and standardized experimental protocols are essential for the development and regulatory approval of novel DES and DCB coatings.

In Vitro Drug Release Kinetics

This protocol characterizes the drug release profile from a coated device under simulated physiological conditions.

- Objective: To quantify the rate and extent of drug release from a DES or DCB over time.

- Materials:

- Coated stent or balloon sample

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.05% w/v Tween 80 (or another suitable surfactant) as the release medium, maintained at 37±0.5°C [6]

- USP Apparatus 4 (flow-through cell) or Apparatus 7 (sample immersion) may be used

- High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) system with a validated method for drug quantification

- Method:

- Immerse the device in a known volume of release medium under continuous, gentle agitation.

- At predetermined time points (e.g., 1 hr, 6 hr, 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, 28 days), withdraw and replace the entire release medium to maintain sink conditions.

- Analyze the collected samples using HPLC to determine the cumulative amount of drug released.

- Plot the cumulative drug release (%) versus time to generate the release profile.

- Data Analysis: Model the release data using kinetic models (e.g., zero-order, first-order, Higuchi) to understand the release mechanism. Accelerated release conditions (e.g., elevated temperature) may be developed and validated to predict long-term release profiles for quality control purposes [6].

Coating Uniformity and Surface Characterization

This protocol ensures the quality and consistency of the drug-polymer coating.

- Objective: To assess the thickness, uniformity, and surface morphology of the coating on the stent struts or balloon surface.

- Materials:

- Coated stent or balloon

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

- Atomic Force Microscope (AFM)

- Optical Profilometer

- Method:

- SEM Imaging: Sparrow et al. (2022) describe sputter-coating the sample with a thin layer of gold/palladium to prevent charging. Image multiple struts or balloon sections at various magnifications (e.g., 50X to 10,000X) to visualize coating cracks, webbing, or delamination [6].

- Surface Roughness (AFM): Scan a defined area (e.g., 10 µm x 10 µm) on the coating surface using AFM in tapping mode. Calculate the average surface roughness (Ra) and root mean square roughness (Rq).

- Coating Thickness (Optical Profilometry): Use a profilometer to scan across the edge of a coated region. Measure the step height between the coated and uncoated substrate at multiple locations (n≥9) to determine average thickness and uniformity.

- Acceptance Criteria: Coating should be continuous, without significant cracking or delamination. Thickness measurements should fall within a specified range with low variability (e.g., ±10%).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Anti-Proliferative Coating Research

| Item | Function/Application | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) | The anti-proliferative agent that inhibits neointimal hyperplasia. | Paclitaxel, Sirolimus (and analogs: Everolimus, Zotarolimus) [2] [11] |

| Polymer Carrier | Controls the release rate of the API from the device. Can be durable or biodegradable. | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), Poly(n-butyl methacrylate) (PBMA), Polysulfone [13] [6] |

| Excipient (for DCBs) | Hydrophilic matrix that facilitates drug transfer from the balloon to the arterial wall. | Iopromide, Shellac, Acetyl tributyl citrate (ATBC), Urea [2] |

| Sterilization Agent | Ensures device sterility without compromising coating integrity or drug activity. | Ethylene Oxide (EtO) [6] |

| Tubulin Polymerization Assay Kit | In vitro tool to verify the mechanistic activity of paclitaxel or similar agents. | Commercial kits measuring microtubule formation kinetics. |

| Cell-Based Proliferation Assay | To test the biological efficacy of eluted drugs. | SRB assay, MTT assay using human vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) [15] |

| 3-GlcA-28-AraRhaxyl-medicagenate | 3-GlcA-28-AraRhaxyl-medicagenate, CAS:128192-15-4, MF:C52H80O24, MW:1089.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| N-Boc-piperazine-C3-COOH | N-Boc-piperazine-C3-COOH, CAS:959053-53-3, MF:C14H24N2O5, MW:300.355 | Chemical Reagent |

The effective application of anti-proliferative agents in DES and DCB is a cornerstone of modern interventional cardiology. The continuous refinement of these technologies—through the development of novel drugs, advanced polymer systems, and polymer-free approaches—aims to optimize pharmacokinetics for maximal therapeutic benefit and long-term safety. The experimental protocols and research tools outlined herein provide a foundational framework for scientists and engineers engaged in the critical work of developing the next generation of vascular devices. A deep understanding of drug mechanisms and pharmacokinetics, coupled with rigorous characterization methodologies, is essential for driving innovation in this field.

In the development of drug-eluting stents (DES), the interplay between structural design parameters and coating application techniques is critical for achieving optimal clinical performance. Stents must provide adequate mechanical support to maintain vessel patency while facilitating controlled drug delivery to prevent restenosis. The core mechanical properties—strut thickness, flexibility, and radial strength—are deeply interconnected and significantly influence the stent's interaction with the vascular environment, the effectiveness of the drug-eluting coating, and long-term patient outcomes [16] [17]. This document outlines key design parameters, experimental characterization methods, and their implications for DES coating and application research.

Core Stent Design Parameters and Quantitative Data

Strut Thickness

Strut thickness is a primary determinant of stent performance, influencing both biological responses and deliverability. The trend in new-generation DES is toward thinner struts to improve hemodynamics and reduce thrombogenic risk [17].

Table 1: Impact of Strut Thickness on Stent Performance

| Strut Thickness (μm) | Stent Type/Platform | Key Performance Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 60-64 | Orsiro SES (≤3 mm dia.), MiStent SES | Lower thrombogenicity; faster endothelialization; reduced restenosis | [17] |

| 74-81 | Synergy EES (Pt-Cr) | Improved flexibility, trackability, and reduced side branch occlusion risk | [17] |

| 80 | Ultimaster SES (Co-Cr) | Open-cell design with biodegradable polymer on abluminal side | [17] |

| 132-140 | Early-generation DES (Cypher, Taxus) | 1.5-fold more thrombogenic than 81 μm struts in preclinical models | [17] |

| 150 | Novel L-PBF 316L Stainless Steel Stent | Target wall thickness for metallic stents balancing strength and hemodynamics | [18] |

Preclinical evidence demonstrates that thicker struts (132-140 µm) are approximately 1.5-fold more thrombogenic than thinner struts (81 µm) in ex vivo flow loops [17]. Furthermore, in a porcine model, thick-strut stents accumulated more thrombus and fibrin deposition at three days post-implantation. A pivotal clinical trial (ISAR-STEREO) showed that using thin-strut (50 µm) bare-metal stents instead of thick-strut (140 µm) counterparts significantly reduced binary restenosis at six months (15% vs. 25.8%) and target vessel revascularization (8.6% vs. 13.8%) [17].

Flexibility and Radial Strength

Flexibility is crucial for deliverability through tortuous anatomy, while radial strength is essential for resisting vascular recoil and maintaining vessel patency. These parameters are significantly influenced by stent design, including the configuration of connectors (links) and support rings.

Table 2: Stent Mechanical Performance Characteristics

| Stent Design / Parameter | Radial Strength | Flexibility / Axial Shortening | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Novel Variable-Thickness (VT) Polymer Stent | 10% improvement vs. constant-thickness (CT) stent | Not quantified, but design aims to enhance flexibility | [19] |

| L-PBF 316L M-Type Stent (Metal) | 840 mN/mm | Axial shortening rate of 5.56% | [18] |

| L-PBF 316L M-Type Stent (Metal) | Radial recoil rate of 1.37% | --- | [18] |

| Connector (Bridge) Design | Secondary influence on radial strength | Primary determinant of stent flexibility | [19] |

| Support Ring Architecture & Strut Configuration | Primary determinant of radial strength | Governs axial shortening and flexibility | [18] |

Finite Element Analysis (FEA) and experimental studies show that connecting elements (bridges) have the most significant effect on stent flexibility [19]. Meanwhile, the radial-support rings are the primary load-bearing elements governing radial strength [18]. Innovative designs, such as the double-period unequal-height support rings interconnected by M-shaped struts, aim to optimize the distribution of radial force and control axial shortening during expansion [18].

Experimental Protocols for Mechanical Characterization

Protocol for Radial Strength and Stiffness Testing

Radial force testing is a critical assessment for stent design validation and regulatory submission, measuring a stent's ability to withstand external compressive forces.

- Objective: To measure the radial stiffness, chronic outward force (for self-expanding stents), and radial resistive force of a vascular stent as a function of diameter.

- Equipment: RX550/650 radial force tester (Machine Solutions Inc.) or equivalent system with a segmented head (e.g., 12 segments) for uniform compression. The system must be capable of precise control and recording of diameter and force [20].

- Environmental Control: Set the test temperature to 37°C using the chamber's temperature control system to simulate physiological conditions [20].

- Sample Preparation: Randomly select test samples. Measure and record the free (unconstrained) outer diameter and length of each stent sample using a micrometric gauging machine before and after testing [20].

- Test Profiles (Select as appropriate) [20] [21]:

- Compression Only: For balloon-expandable and self-expanding stents. The head compresses the stent from its initial diameter to a smaller target diameter at a defined speed.

- Expansion Only: Primarily for self-expanding stents. The stent is deployed or compressed to a small diameter, then the head diameter is gradually increased at a set speed to the final target diameter.

- Compression/Expansion Cycles: Multiple cycles are performed to assess the hysteresis behavior of self-expanding stents.

- Customized Profiles: Diameter variation according to a user-defined profile (e.g., specific time-diameter file).

- Data Acquisition: Record the radial force versus diameter throughout the loading and/or unloading profile [20].

- Data Analysis: Report the radial force versus diameter curve. The radial strength is often reported as the maximum compressive force per unit length (e.g., in mN/mm) sustained by the stent. For comparative analysis, the force value may be normalized by the measured stent length [20] [18].

- Regulatory Compliance: This test method supports submissions per FDA guidance and international standards such as ASTM F3067 (Guide for Radial Loading of Vascular Stents) and ISO 25539-2 (Cardiovascular implants — Endovascular devices — Part 2: Vascular stents) [20] [21] [22].

Protocol for Three-Point Bending Flexibility Test

The three-point bending test assesses stent flexibility, which correlates to its deliverability through curved vasculature.

- Objective: To quantify the bending stiffness of a stent by measuring the force-deflection relationship during bending.

- Equipment: A universal testing machine equipped with a three-point bending fixture. The fixture has two fixed lower supports and one movable upper loading pin.

- Sample Preparation: The stent sample is placed across the two lower supports.

- Test Procedure: The upper loading pin is displaced downward at a constant rate, applying a force at the mid-span of the stent until a target deflection is reached. The force and deflection are recorded simultaneously [19].

- Data Analysis: The force-deflection curve is plotted. The slope of the linear (elastic) portion of this curve is used to calculate the bending stiffness. A validated Finite Element Model (FEM) can be correlated with experimental data to analyze strain distribution, particularly in the plastic deformation range [19].

- Application in Design: This method is used to evaluate how different connector designs impact overall stent flexibility. Research has shown that optimizing design can reduce bending forces and improve conformability to vessel walls [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Stent Design and Coating Research

| Material / Solution | Function in Research | Relevance to DES Development | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(L-lactic acid) (PLLA) Resin | Base material for fabricating polymeric stent scaffolds via 3D printing (e.g., LCD). | Biodegradable polymer used in stents (e.g., Orsiro SES) and as a drug-carrying matrix. | [19] [17] |

| Cobalt-Chromium (Co-Cr) & Platinum-Chromium (Pt-Cr) Alloys | High-strength metal platforms for stent scaffolding. | Enable thinner strut designs without sacrificing radial strength; common in new-generation DES. | [17] [23] |

| 316L Stainless Steel Powder | Feedstock for Laser Powder Bed Fusion (L-PBF) additive manufacturing of stents. | Allows monolithic fabrication of complex, patient-specific stent designs. | [18] |

| Poly(DL-lactic acid)/Polycaprolactone (PLGA-PCL) Blend | Biodegradable polymer coating for controlled drug release. | Used as an abluminal coating on stents (e.g., Ultimaster SES) to elute anti-proliferative drugs. | [17] |

| Sirolimus, Everolimus, Paclitaxel | Pharmaceutical agents (anti-proliferative) loaded into polymer coatings. | Inhibits smooth muscle cell proliferation to prevent in-stent restenosis; core of DES function. | [16] [17] [23] |

| Electropolishing Solutions | Electrolytic solutions for post-fabrication surface finishing. | Critical for reducing surface roughness of metal stents (e.g., L-PBF printed), improving biocompatibility and potentially coating uniformity. | [18] |

| Glycodeoxycholic acid monohydrate | Glycodeoxycholic acid monohydrate, MF:C26H45NO6, MW:467.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | |

| THP-PEG4-Pyrrolidine(N-Me)-CH2OH | THP-PEG4-Pyrrolidine(N-Me)-CH2OH, MF:C19H37NO7, MW:391.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implications for Drug-Eluting Stent Coating and Application

The structural design parameters directly impact the constraints and opportunities for drug coating application. Thinner struts present a smaller surface area for drug deposition, requiring highly uniform and efficient coating techniques like ultrasonic spraying or dip-coating to ensure consistent drug dosage [17] [23]. The choice of polymer is critical; while durable polymers provide a stable platform, they can provoke inflammatory responses. Conversely, biodegradable polymers (e.g., PLLA, PLGA) degrade after fulfilling their drug-release function, potentially improving long-term safety by leaving behind a bare metal stent [17]. Advanced coating strategies, such as the asymmetric or gradient coating on the abluminal side only, maximize drug delivery to the vessel wall while minimizing drug loss to the bloodstream [17] [23]. Furthermore, the mechanical integrity of the coating must withstand stent crimping and expansion without cracking or delaminating, a challenge that is exacerbated in more flexible stent designs with complex deformations [19] [17].

The efficacy of drug-eluting stents (DES) is fundamentally governed by the complex, multi-layered structure of the arterial wall, which acts as the primary environment for drug transport following deployment. Cardiovascular diseases, particularly atherosclerosis, remain a leading cause of death globally, and DES have revolutionized treatment by drastically reducing the rate of in-stent restenosis (ISR) compared to bare-metal stents [7] [3]. The primary challenge in DES design lies in achieving sufficient drug delivery to the target tissues to inhibit restenosis while minimizing safety risks, a balance heavily influenced by the dynamic drug transport processes within the arterial wall [7] [24]. This Application Note details the structural components of the arterial wall, the computational and experimental methodologies used to model drug transport within it, and the key parameters that determine the safety and efficacy of drug delivery from DES.

Structural Environment of Drug Transport

The arterial wall is not a homogeneous medium but a structured, multi-layered tissue. Each layer presents a unique set of physical and biological barriers that dictate drug kinetics.

- The Endothelium and Subendothelial Intima (SES): The endothelium forms the innermost lining of the artery. During stent implantation, this layer is typically denuded, removing a significant physical barrier. The underlying subendothelial intima is a porous layer that, in atherosclerotic arteries, can contain migrated smooth muscle cells (SMCs) that become binding sites for anti-proliferative drugs [24].

- The Internal Elastic Lamina (IEL): This membrane, rich in elastin, separates the intima from the media. It acts as a selective barrier, with its fenestrations influencing the rate and distribution of drug molecules passing into the media [24].

- The Media: The medial layer is the primary target for DES-delivered drugs, as it contains the SMCs whose proliferation leads to restenosis. This layer is modeled as a porous medium where drug transport occurs via diffusion and convection, with the added complexity of reversible binding to cellular components [25] [24].

- The Adventitia: The outermost layer, consisting of connective tissue, is often modeled as a boundary condition that can act as a "sink" for drugs, influencing the overall concentration profile within the arterial wall [24].

Quantitative Framework for Drug Transport Modeling

Computational models integrate the physics of drug release from the stent coating with drug transport and binding in the arterial wall. The tables below summarize key parameters and governing equations from established models.

Table 1: Key Parameters in DES Drug Transport Models [25] [24]

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Values / Range | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strut Dimension | a |

100 - 140 µm | Size of the stent strut. |

| Coating Thickness | δ |

5 - 50 µm | Thickness of the drug-polymer coating. |

| Arterial Wall Thickness | Lx |

~200 µm | Thickness of the arterial wall layer. |

| Coating Drug Diffusivity | D1 |

0.01 - 1 µm²/s | Diffusivity of the drug within the polymer coating. |

| Vascular Drug Diffusivity | D2 |

0.1 - 10 µm²/s | Diffusivity of the drug within the arterial wall tissue. |

| Initial Drug Concentration | C0 |

~10â»âµ M | Initial drug load in the stent coating. |

| Association Rate Constant | ka |

10â´ Mâ»Â¹sâ»Â¹ | Rate constant for drug binding to tissue. |

| Dissociation Rate Constant | kd |

0.01 sâ»Â¹ | Rate constant for drug unbinding from tissue. |

| Binding Site Concentration | S0 |

~10â»âµ M | Concentration of available drug binding sites. |

Table 2: Governing Equations for Drug Transport in a Multi-Layered Artery [25] [24]

| Domain | Primary Transport Mechanism | Governing Equation / Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Stent Coating | Diffusion | Fickian diffusion: ∂c/∂t = ∇ · (D₠∇c) |

| Arterial Lumen | Convection & Diffusion | Navier-Stokes equations (flow) + Advection-Diffusion equation (drug transport). |

| Subendothelial Intima (SES) | Convection, Diffusion & Reaction | ∂c_se/∂t + u · ∇c_se = D_se ∇²c_se - k_a c_se (b_max,se - b) + k_d b |

| Media | Convection, Diffusion & Reaction | ∂c_m/∂t + u · ∇c_m = D_m ∇²c_m - k_a c_m (b_max - b) + k_d b∂b/∂t = k_a c_m (b_max - b) - k_d b (Binding kinetics) |

The following diagram illustrates the integrated process of drug release from a stent strut and its subsequent transport through the multi-layered arterial wall, incorporating the key mechanisms described in the tables above.

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Protocol: Computational Simulation of Arterial Drug Distribution

This protocol outlines the steps for using a finite volume method to simulate drug distribution from a single stent strut in a coronary artery cross-section, based on established computational studies [25].

I. Model Geometry Definition

- Create a 2D geometric model representing a rectangular section of the arterial wall adjacent to a single stent strut.

- Define the strut dimensions (e.g., 140 µm), coating thickness (e.g., 5-50 µm), and depth of strut embedment into the arterial wall (

Lp). - Set the overall arterial wall thickness (

Lxto ~200 µm) and the inter-strut distance (Ly, e.g., 1000 µm for an 8-strut stent in a 3-mm artery) [25].

II. Parameter Initialization

- Input the physicochemical parameters for the drug and arterial environment as listed in Table 1. This includes:

- Initial drug concentration in the coating (

Câ‚€). - Drug diffusivities in the coating (

Dâ‚) and arterial wall (Dâ‚‚). Note that the vascular diffusivity can be isotropic or anisotropic (e.g., higher circumferential diffusivityDâ‚‚ythan transmural diffusivityDâ‚‚x) [25]. - Binding kinetic parameters (

kâ‚,k_d,Sâ‚€).

- Initial drug concentration in the coating (

III. Numerical Solution

- Discretize the computational domain using a mesh with sufficient resolution near the strut to capture high concentration gradients.

- Apply boundary conditions: a symmetry condition at the tissue boundaries between struts, a perfect sink condition at the adventitial boundary, and a no-flux condition at the luminal boundary in the denuded area.

- Solve the coupled system of partial differential equations (from Table 2) for drug diffusion in the coating and drug convection-diffusion-reaction in the arterial wall using a finite volume solver until a steady-state or time-dependent solution is achieved.

IV. Data Analysis

- Extract spatiotemporal data for free and bound drug concentrations throughout the arterial wall domain.

- Calculate metrics such as the spatial-average drug level in the media and the drug content (DC) parameter, which is linked to safety [7].

- Visualize the results as contour plots of drug distribution at specific time points (e.g., 1, 7, 30 days) to identify regions of potential therapeutic efficacy or toxicity.

Protocol: Evaluating Safety and Efficacy via a Multiscale Framework

This protocol describes a more advanced framework that couples continuum-based drug transport with an agent-based model (ABM) of vascular remodeling to comprehensively assess DES performance [7].

I. Framework Setup

- Establish a multiscale computational framework with two core modules:

- A Continuum-based Drug Transport Model: Simulates drug release from the DES and its subsequent transport in the arterial wall, as described in Section 4.1.

- An Agent-Based Model (ABM) of Vascular Remodeling: Models the behavior of individual Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell (VSMC) agents in response to drug concentrations and inflammatory signals.

II. Model Coupling and Input

- Link the models so that the local free drug concentration calculated by the continuum model serves as an input to the ABM, influencing VSMC agent behaviors like proliferation and apoptosis.

- Define the inflammatory input to the ABM to be non-uniform, reflecting that VSMC agents closer to the stent strut experience stronger inflammation [7].

- Incorporate the effect of VSMC agent age on mitosis into the ABM to improve biological fidelity [7].

III. Simulation Execution

- Run coupled simulations for a defined period (e.g., 50 days post-implantation).

- Compare simulations of a novel DES design (e.g., a dual-layer coating DES) against a conventional DES.

IV. Performance Quantification

- Quantify Efficacy: Measure the degree of inhibition of neointimal hyperplasia (tissue re-growth) in the ABM.

- Quantify Safety: Calculate the drug content (DC) parameter from the continuum model, where a lower DC indicates greater safety [7].

- An optimal DES design demonstrates a significant advantage in safety (lower DC) with only a slight reduction in efficacy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below catalogs essential materials and computational tools used in the development and analysis of drug transport environments for DES.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for DES Drug Transport Studies

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Sirolimus (Rapamycin) | An immunosuppressive and anti-proliferative drug that inhibits mTOR, used in DES to suppress smooth muscle cell proliferation and restenosis [26]. |

| Paclitaxel | A cytotoxic anti-proliferative drug that stabilizes microtubules, preventing cell division. Also used in DES and drug-eluting balloons [24]. |

| Bio-durable Polymers | Non-degradable polymer coatings (e.g., on early-generation DES) that provide a controlled matrix for drug release over time [25]. |

| Bioresorbable Polymers | Temporary polymer coatings that degrade after completing their drug delivery function, eliminating long-term polymer presence in the artery [3]. |

| Finite Volume Method Solver | A computational fluid dynamics (CFD) technique used to numerically solve the partial differential equations governing drug transport in complex arterial geometries [25]. |

| Agent-Based Modeling (ABM) Platform | A computational modeling paradigm used to simulate the actions and interactions of individual cells (e.g., VSMCs) to assess their collective behavior on tissue remodeling [7]. |

| Dual-Layer Coating | An advanced DES coating design featuring an internal and external drug-polymer layer, which can modulate the drug release profile to mitigate burst release and improve safety [7]. |

| Anisotropic Diffusivity Parameters | A set of distinct diffusion coefficients for different directions within the arterial wall (e.g., circumferential vs. transmural), which more accurately model tissue transport and lead to more uniform drug distribution [25]. |

| Saponin C, from Liriope muscari | Saponin C, from Liriope muscari, MF:C44H70O17, MW:871.0 g/mol |

| Hexamethylbenzene-d18 | Hexamethylbenzene-d18, CAS:4342-40-9, MF:C12H18, MW:162.27 g/mol |

The multi-layered arterial wall presents a highly dynamic and structured environment that determines the fate of drugs released from eluting stents. A deep understanding of the interplay between stent-based release kinetics (influenced by coating technology and drug load) and the tissue-based transport barriers (dictated by diffusion, convection, and binding kinetics) is paramount for optimizing DES design. Computational models that integrate these factors are indispensable tools for in-silico prediction and optimization, helping to narrow down design parameters before costly and time-consuming experimental trials. The ongoing innovation in DES technology, including dual-layer coatings, bioresorbable scaffolds, and sophisticated computational frameworks, continues to advance the central goal of achieving local therapeutic efficacy while ensuring systemic safety.

The evolution of Drug-Eluting Stents (DES) represents one of the most significant advancements in interventional cardiology, fundamentally transforming the management of coronary artery disease. DES technology has progressed through distinct generations, each addressing limitations of its predecessors while introducing novel therapeutic concepts. This progression has shifted the treatment paradigm from merely providing mechanical scaffolding to actively modulating the biological process of vessel healing [3]. The journey from first to fourth-generation DES reflects continuous innovation in scaffold materials, polymer biocompatibility, drug delivery kinetics, and therapeutic agents, culminating in today's sophisticated platforms that offer unprecedented safety and efficacy profiles. Understanding this evolutionary pathway is essential for researchers and drug development professionals working to advance coronary stent technology and improve patient outcomes.

Historical Development and Generational Classification

The Pre-DES Era: Bare-Metal Stents

The foundation for DES was laid with the introduction of bare-metal stents (BMS) in 1986, which represented a significant improvement over plain balloon angioplasty by preventing vessel recoil and negative remodeling [27]. While effective initially, BMS were plagued by high rates of in-stent restenosis (approximately 30%) due to neointimal hyperplasia - a response to vascular injury from stent deployment characterized by migration and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells [27]. This limitation prompted the development of more advanced solutions that could actively modulate the healing process.

First-Generation DES: Proof of Concept with Limitations

First-generation DES emerged in the early 2000s, introducing the revolutionary concept of local drug delivery to inhibit neointimal hyperplasia [27]. These stents featured stainless steel scaffolds coated with either sirolimus (a rapamycin analog) or paclitaxel, released via durable polymers to suppress smooth muscle cell proliferation [3]. The pioneering RAVEL, SIRIUS, and TAXUS trials established the efficacy of these platforms in significantly reducing restenosis rates compared to BMS [27].

However, first-generation DES revealed significant safety concerns, particularly regarding late (>30 days) and very late (>12 months) stent thrombosis, attributed to delayed endothelialization caused by the persistent presence of durable polymers and the anti-proliferative drugs themselves [27]. Additionally, the thick struts (approximately 140 micrometers) and limited flexibility of these early designs posed deliverability challenges in complex anatomy [27].

Table 1: First-Generation Drug-Eluting Stents

| Characteristic | Sirolimus-Eluting Stent (SES) | Paclitaxel-Eluting Stent (PES) |

|---|---|---|

| Scaffold Material | Stainless steel | Stainless steel |

| Strut Thickness | ~140 μm | ~140 μm |

| Therapeutic Agent | Sirolimus | Paclitaxel |

| Mechanism of Action | Binds FKBP12, inhibits mTOR, arrests cell cycle in G1 phase [27] | Inhibits microtubule disassembly, arrests cell cycle in G0-G1 and G2-M phases [27] |

| Key Clinical Trials | RAVEL, SIRIUS [27] | TAXUS [27] |

| Primary Limitation | Late stent thrombosis, delayed endothelialization | Clinical inferiority to SES in restenosis rate [27] |

Second-Generation DES: Enhanced Safety and Deliverability

Second-generation DES, introduced around 2006, addressed many limitations of their predecessors through systematic improvements in scaffold design and polymer technology [28] [3]. These stents transitioned from stainless steel to cobalt-chromium or platinum-chromium alloys, enabling thinner struts (approximately 70-90 micrometers), improved flexibility, and enhanced deliverability without compromising radial strength [27]. The ENDEAVOR and SPIRIT trials established the clinical profiles of these new platforms [27].

The therapeutic agents also evolved, with everolimus and zotarolimus (both sirolimus derivatives) replacing the original drugs, offering more favorable pharmacokinetic profiles [27]. Additionally, more biocompatible polymers were introduced to reduce inflammatory responses and promote healthier vessel healing. These collective advancements resulted in significantly improved safety profiles, particularly regarding very late stent thrombosis, while maintaining efficacy in reducing restenosis [3].

Table 2: Second-Generation Drug-Eluting Stents

| Characteristic | Everolimus-Eluting Stent (EES) | Zotarolimus-Eluting Stent (ZES) |

|---|---|---|

| Scaffold Material | Cobalt-chromium | Cobalt-chromium |

| Strut Thickness | ~80 μm | ~90 μm |

| Therapeutic Agent | Everolimus | Zotarolimus |

| Mechanism of Action | Sirolimus derivative, inhibits mTOR pathway | Sirolimus derivative, inhibits mTOR pathway |

| Key Clinical Trials | SPIRIT [27] | ENDEAVOR [27] |

| Advancements | Improved safety profile, thinner struts, more biocompatible polymers | Enhanced deliverability, reduced inflammation |

Third-Generation DES: Biodegradable Polymers

Third-generation DES introduced biodegradable polymers that provided temporary drug delivery during the critical period of neointimal hyperplasia (typically 3-6 months) before completely resorbing, thereby eliminating the long-term presence of foreign material in the vessel wall [3]. This approach aimed to combine the early restenosis prevention of DES with the long-term safety profile of BMS by allowing complete endothelialization once the polymer had degraded.

The evolution continued with platform refinements including thinner strut designs and optimized drug release kinetics. Initial setbacks with early bioresorbable scaffolds led to improvements in mechanical properties and resorption profiles, paving the way for next-generation technologies [3].

Fourth-Generation DES: Polymer-Free and Bioresorbable Platforms

As of 2025, fourth-generation DES technologies have emerged, characterized by polymer-free designs, advanced bioresorbable scaffolds, and nanotechnology-enhanced drug delivery systems [3]. These innovations aim to further improve long-term outcomes by promoting natural vessel healing, restoring vasomotion, and eliminating permanent metallic implants entirely.

Advanced bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) now feature hybrid metal-polymer compositions, ultra-thin struts (<70 μm), and accelerated resorption profiles (12-18 months) [3]. Polymer-free technologies utilize nanoporous surfaces or micro-reservoirs for controlled drug elution without permanent polymer presence. Additionally, multi-drug elution platforms that combine antiproliferative, anti-inflammatory, and pro-healing agents in temporally coordinated sequences represent the cutting edge of DES technology [3].

Quantitative Clinical Outcomes Across Generations

The progressive evolution of DES technology has translated into measurable improvements in clinical outcomes, as demonstrated by numerous randomized controlled trials and registry analyses. The following tables summarize key performance metrics across generations.

Table 3: Comparative Clinical Outcomes of First vs. Second-Generation DES

| Outcome Measure | First-Generation DES | Second-Generation DES | Pooled Effect Size (OR with 95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-Cause Mortality | Increased risk | Reduced risk | OR: 1.23 (95% CI: 1.05-1.45) [28] | 0.0120 |

| Myocardial Infarction | Increased risk | Reduced risk | OR: 1.48 (95% CI: 1.22-1.80) [28] | <0.0001 |

| Target Lesion Revascularization | Increased risk | Reduced risk | OR: 1.47 (95% CI: 1.24-1.74) [28] | <0.0001 |

| Cardiac Death | Similar risk | Similar risk | Not significant [28] | - |

| Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events | Similar risk | Similar risk | Not significant [28] | - |

Table 4: Contemporary DES Performance Metrics (2025)

| Performance Metric | Fourth-Generation DES | Third-Generation DES | Second-Generation DES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Lesion Failure (1 year) | <3% [3] | ~4-5% | ~5-6% |

| Very Late Stent Thrombosis (/year) | <0.1% [3] | ~0.2-0.3% | ~0.3-0.5% |

| Strut Thickness | 60-70 μm [3] | 70-80 μm | 80-100 μm |

| Polymer Presence | Polymer-free or fully bioresorbable [3] | Biodegradable (3-6 months) | Durable or biodegradable |

Experimental Protocols for DES Evaluation

Pre-Clinical Assessment Protocol

Objective: To evaluate the safety and efficacy of novel DES platforms in controlled animal models before human trials.

Methodology:

- Stent Implantation: Deploy test and control DES in healthy or atherosclerotic porcine coronary arteries (n=30-40 stents per group)

- Histopathological Analysis:

- Euthanize animals at 28, 90, and 180 days post-implantation

- Process arteries for plastic embedding and sectioning

- Perform hematoxylin-eosin and elastic trichrome staining

- Quantify neointimal area, inflammation score, endothelialization percentage, and fibrin deposition

- Drug Kinetics Assessment:

- Measure tissue drug concentrations at multiple time points using LC-MS/MS

- Determine arterial wall drug distribution via autoradiography or MALDI imaging

- Statistical Analysis: Compare continuous variables using ANOVA with post-hoc testing, categorical variables with chi-square test (significance at p<0.05)

Clinical Evaluation Protocol for New DES Platforms

Objective: To demonstrate clinical non-inferiority and superiority of next-generation DES compared to contemporary standards.

Study Design: Prospective, multicenter, randomized controlled trial with blinded endpoint adjudication.

Population: Patients with symptomatic coronary artery disease requiring percutaneous intervention (n=2000-5000).

Intervention:

- Experimental: Novel DES platform (e.g., polymer-free nano-coated)

- Control: Current standard-of-care DES

Primary Endpoint: Target lesion failure at 12 months (composite of cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction, clinically-driven target lesion revascularization).

Secondary Endpoints:

- Device success

- Procedure success

- Individual components of primary endpoint

- Stent thrombosis (ARC definite/probable)

- Patient-oriented composite endpoint (all death, all MI, all revascularization)

Follow-up Protocol: Clinical assessment at 1, 6, and 12 months, then annually to 5 years; angiographic follow-up in subset at 13 months; intravascular imaging in subset at 13 months.

Statistical Considerations:

- Power calculation based on non-inferiority margin of 3.5% for primary endpoint

- Intention-to-treat analysis

- Pre-specified subgroup analyses for complex lesions

Signaling Pathways and Biological Mechanisms

The efficacy of DES depends on precisely modulating complex biological pathways involved in vascular healing. The following diagram illustrates key signaling pathways targeted by DES therapeutic agents.

DES Technology Selection Algorithm

Choosing the appropriate DES generation and platform requires consideration of multiple clinical, anatomical, and patient-specific factors. The following workflow provides a systematic approach to DES selection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for DES Development

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Cobalt-Chromium Alloy | Scaffold material for 2nd-4th generation DES | MP35N or L605 composition, radial strength >150 kPa, strut thickness 60-90 μm [27] |

| Poly(L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) PLGA | Biodegradable polymer for drug elution | Varying lactide:glycolide ratios (50:50 to 85:15), molecular weight 10-100 kDa, degradation time 30-180 days [3] |

| Everolimus | Anti-proliferative therapeutic agent | Chemical formula C₅₃H₈₃NOâ‚â‚„, molecular weight 958.2 g/mol, solubility in ethanol ~50 mg/mL, working concentration 100 μg/cm² stent surface area [27] |

| Fluorescently-labeled Anti-CD31 Antibody | Endothelialization assessment | Host: mouse monoclonal, clone JC70A, working dilution 1:100-1:500, excitation/emission ~494/519 nm (FITC conjugate) |

| Masson's Trichrome Stain | Histological evaluation of vessel healing | Differentiates collagen (blue), muscle/cytoplasm (red), and nuclei (dark brown); quantifies neointimal area and fibrin deposition |

| PDGF-BB Recombinant Protein | In vitro smooth muscle cell proliferation assay | Source: E. coli, molecular weight ~25 kDa, working concentration 10-50 ng/mL, induces SMC migration and proliferation |

| HUVEC (Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells) | Endothelialization and biocompatibility testing | Culture medium: ECM-2 with growth supplements, passage 3-6, seeding density 10,000 cells/cm² for migration assays |

| LC-MS/MS System | Drug release kinetics and tissue concentration | Column: C18 reverse phase (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.8 μm), mobile phase: methanol/water with 0.1% formic acid, LLOQ ~0.1 ng/mL for rapamycin analogs |

| 2-Picenecarboxylic acid | 2-Picenecarboxylic acid, CAS:118172-80-8, MF:C28H36O5, MW:452.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 10-Methylhexadecanoic acid | 10-Methylhexadecanoic acid, CAS:17001-26-2, MF:C17H34O2, MW:270.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Future Directions and Emerging Technologies

The evolution of DES technology continues with several promising innovations currently in advanced stages of development. Genetically engineered endothelial progenitor cell capture stents incorporate antibodies or aptamers that selectively capture circulating endothelial progenitor cells, dramatically accelerating endothelialization and vessel healing [3]. Smart stents with integrated miniaturized sensors can monitor local flow dynamics, inflammatory markers, and endothelial function in real-time, providing unprecedented insights into vessel healing and enabling early detection of complications [3].

Three-dimensional printed personalized stents represent another frontier, with customized designs tailored to individual patient anatomy potentially manufactured in the catheterization laboratory during the procedure itself [3]. Additionally, dual-drug eluting stents carrying combinations of antiproliferative and anti-thrombotic agents with time-controlled release profiles are being developed to target the different timing of bio-response to stent implantation [27]. Gene-eluting stents that deliver plasmid DNA to express therapeutic proteins such as VEGF directly within the vessel wall are also under investigation to support healthy endothelialization [27].

These emerging technologies, combined with personalized medicine approaches based on genetic profiling and lesion-specific characteristics, promise to further refine the field of coronary intervention and improve outcomes for the millions of patients worldwide affected by coronary artery disease.

DES Coating Techniques and Advanced Application Methodologies

The application of uniform, consistent coatings is a critical step in the manufacturing of drug-eluting stents (DES), directly influencing drug delivery kinetics, safety, and therapeutic efficacy [6]. Coating techniques must ensure precise control over thickness, uniformity, and integrity to facilitate controlled drug elution and maintain biocompatibility within the vascular environment [6]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for three central coating methods—dip-coating, spray-coating, and immersion techniques—within the specific context of DES development for researchers and scientists.

The selection of a coating method impacts critical quality attributes. Table 1 provides a comparative overview of these techniques.

Table 1: Comparison of Coating Application Methods for Drug-Eluting Stents

| Parameter | Dip-Coating | Spray-Coating | Immersion Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Submersion and withdrawal of stent into coating solution [6] | Atomization of coating solution directed onto stent surface [6] [29] | Prolonged submersion to saturate or functionalize the surface |

| Coating Uniformity | Challenging to ensure uniformity; prone to edge effects [6] | High uniformity achievable; industry-feasible for layer-by-layer coating [6] [29] | Varies with substrate and solution properties |

| Process Control | Dependent on withdrawal speed and viscosity [30] | High control via programmable parameters (spray rate, pattern, nozzle distance) [29] | Dependent on immersion time and concentration |

| Scalability | Suitable for R&D and small batches [29] | Highly scalable for industrial production with high productivity [6] | Easily scalable for batch processing |

| Key Challenges | Ensuring uniformity, avoiding sagging, managing solvent evaporation [6] | Managing overspray, nozzle clogging, ensuring consistent droplet size [6] | Controlling drug leaching back into solution, achieving precise thickness |

Dip-Coating Methodology

Dip-coating involves the controlled submersion and withdrawal of a stent from a coating solution reservoir. The coating thickness is primarily governed by the withdrawal speed and the viscosity of the coating solution [30].

Experimental Protocol: Dip-Coating of a Polymeric Drug Solution

Objective: To apply a uniform primer layer of a biodegradable polymer (e.g., PLGA) onto a nitinol stent platform.

Materials:

- Stent Substrate: Cleaned, bare nitinol stent.

- Coating Solution: Poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) dissolved in a suitable organic solvent (e.g., acetone, dimethyl sulfoxide) to a target concentration (e.g., 1-5% w/v).

- Equipment: Precision dip-coater apparatus (automated or semi-automated), solvent-resistant container, fume hood, drying oven.

Procedure:

- Stent Preparation: Plasma clean the nitinol stent to increase surface energy and promote coating adhesion.

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve the PLGA polymer in the solvent under constant stirring until a clear, homogeneous solution is achieved.

- Coating Process:

- Secure the stent vertically in the dip-coater holder.

- Program the dip-coater with the following parameters:

- Immersion speed: 5 mm/s

- Dwell time in solution: 30 seconds

- Withdrawal speed: 1 mm/s (optimize based on desired thickness)

- Initiate the coating cycle to submerge the stent completely, hold, and withdraw.

- Drying & Curing:

- Immediately transfer the coated stent to a drying oven.

- Cure at a controlled temperature (e.g., 40-50°C) for 1-2 hours to evaporate the solvent.

- Quality Assessment: Determine coating mass gravimetrically and inspect for defects using scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the sequential steps involved in a standardized dip-coating process.

Spray-Coating Methodology

Spray-coating employs atomization to deposit a fine mist of coating solution onto the stent surface. It is the most widely used technique in industrial-scale DES manufacturing due to its precision and layer-by-layer capability [6] [29].

Experimental Protocol: Spray-Coating of a Drug-Polymer Matrix

Objective: To apply a uniform layer of a drug-polymer matrix (e.g., Sirolimus in PLGA) onto a primed stent surface.

Materials:

- Stent Substrate: Primer-coated nitinol stent mounted on a rotating mandrel.

- Coating Solution: Homogeneous dispersion of crystalline Sirolimus in PLGA solution [31].

- Equipment: Ultrasonic spray coater with precision nozzle, XYZ motion stage, rotary fixture, fume hood, drying oven.

Procedure:

- System Setup:

- Mount the stent securely on a rotating mandrel within the spray chamber.

- Set the nozzle-to-stent distance (e.g., 10-30 mm).

- Calibrate the spray parameters using a blank substrate.

- Coating Process:

- Program the spray coater with optimized parameters:

- Nozzle type: Ultrasonic or air-assisted

- Liquid flow rate: 0.1 - 0.5 mL/min

- Atomization pressure (if applicable): 5-15 psi

- Mandrel rotation speed: 100-500 rpm

- Nozzle traverse speed: 1-10 mm/s

- Number of passes: 10-100 (to achieve target drug dose)

- Initiate the spray cycle, ensuring even coverage over the entire stent surface.

- Program the spray coater with optimized parameters:

- Drying Between Layers: Apply mild drying (e.g., 40°C air flow) between passes to prevent washing off previous layers.

- Final Curing: After the final pass, cure the stent in an oven at a specified temperature and time to form a stable coating.

- Quality Assessment: Measure coating thickness per strut via SEM and perform HPLC to quantify drug content and uniformity.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram outlines the core operational loop of a spray-coating system.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful coating development relies on a suite of specialized materials. Table 2 details key reagents and their functions in DES coating formulation and application.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Stent Coating R&D

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example in DES Context |

|---|---|---|