Advanced Degradable Suture Materials and Implantation: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of degradable suture materials and their implantation methods, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Advanced Degradable Suture Materials and Implantation: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of degradable suture materials and their implantation methods, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational science behind material chemistry, from established polymers to emerging biomaterials like albumin composites and biodegradable metals. The scope extends to methodological considerations for implantation, critical troubleshooting of mechanical integrity and biocompatibility, and a rigorous comparative validation of material properties. By synthesizing current research and performance data, this review serves as a strategic resource for guiding the development and application of next-generation sutures in tissue engineering and clinical practice.

The Material Science of Degradation: From Polymer Chemistry to Novel Biomaterials

Surgical sutures are medical devices essential for approximating tissues and facilitating the wound-healing process. Within the context of degradable biomaterials research, they are fundamentally classified based on their interaction with the biological environment over time. Absorbable sutures are those that lose their tensile strength within 60 days and are subsequently broken down and metabolized by the body, with little to no trace remaining [1] [2]. In contrast, Non-absorbable sutures are defined by their ability to retain most of their initial tensile strength for longer than 2-3 months, and they typically remain encapsulated in tissue or require manual removal [1] [3].

This classification is not merely temporal but is rooted in the material's composition and its degradation mechanism. Absorbable sutures, constructed from natural or synthetic polymers, are engineered to undergo hydrolytic degradation or proteolytic enzymatic degradation at a rate commensurate with tissue healing [4] [1]. Non-absorbable sutures, made from biostable materials, provide permanent structural support, making them indispensable in high-tension anatomical regions or for securing prosthetic implants [1] [3]. The following sections will delineate the key characteristics, quantitative properties, and experimental protocols central to the research and development of these critical biomaterials.

Key Characteristics and Comparative Analysis

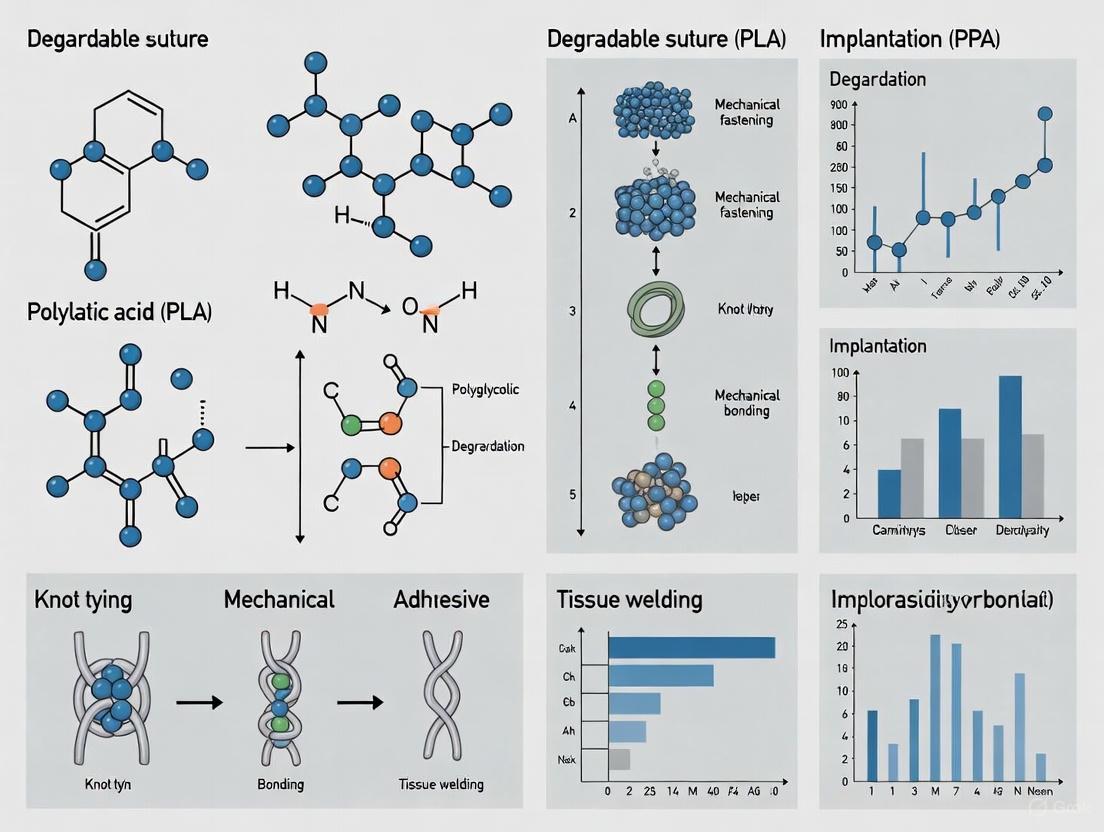

The selection of a suture material for a specific clinical or research application is guided by a detailed understanding of its physicochemical and mechanical properties. The following diagram illustrates the primary classification logic and key degradation pathways for suture materials, providing a framework for their study.

Material Composition and Degradation Profiles

The core distinction between absorbable and non-absorbable sutures lies in their material composition, which directly dictates their degradation profile and biological interaction.

Absorbable Sutures: These materials are designed with a finite lifespan in vivo. Natural variants, such as surgical gut (catgut), are degraded by proteolytic enzymes and subsequently phagocytosed by macrophages [4]. Synthetic absorbables, including polyglycolic acid (PGA), polylactide (PLA), poly-p-dioxanone (PDS), and copolymers like polyglactin 910 (Vicryl), degrade primarily through hydrolysis of their ester bonds [4] [1]. The degradation kinetics are influenced by the polymer's crystallinity, molecular weight, and the local biological environment (e.g., pH, enzyme levels) [4]. A critical performance metric is the "strength retention half-life," which varies significantly between suture groups, as detailed in Table 1.

Non-Absorbable Sutures: These materials are engineered for biostability. They encompass natural fibers like silk and cotton, and synthetic polymers such as polypropylene (Prolene), polyamide (nylon), polyester, and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) [1] [2] [3]. They do not undergo significant degradation; instead, they elicit a foreign body reaction that typically results in the suture becoming encapsulated by fibrous tissue [3]. Their resistance to hydrolysis ensures long-term mechanical support, a necessity in procedures like hernia repair, cardiovascular surgery, and the securing of orthopedic hardware [1] [3].

Quantitative Mechanical and Physical Properties

The functional performance of a suture is quantifiable through a set of standardized mechanical properties. Recent comparative studies of commonly used materials provide critical data for evidence-based selection.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Representative Suture Materials

| Suture Material | Type & Classification | Tensile Strength (Relative) | Key Degradation / Strength Retention Timeline | Primary Tissue Reaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vicryl (Polyglactin 910) | Synthetic, Absorbable, Multifilament | Highest [5] | ~50% strength loss in 14-21 days; total absorption in 60-90 days [4] [1] | Moderate tissue reactivity [5] |

| Monocryl (Polyglecaprone 25) | Synthetic, Absorbable, Monofilament | Not Specified | Classified as a medium-term absorbable [4] | Lower reaction vs. multifilament [6] |

| PDS (Polydioxanone) | Synthetic, Absorbable, Monofilament | Not Specified | ~50% strength loss in 28-35 days; total absorption in 180-210 days [4] [1] | Minimal [1] |

| SafilQuick+ (PGA) | Synthetic, Absorbable, Braided | Not Specified | Loses strength significantly in 9-12 days; total absorption ~42 days [4] | Not Specified |

| Silk | Natural, Non-Absorbable, Multifilament | Lowest of compared materials [5] | Retains strength >2-3 months; undergoes slow proteolysis [1] [7] | Significant tissue reactivity [5] |

| Polypropylene (Prolene) | Synthetic, Non-Absorbable, Monofilament | Intermediate (Lower than VICRYL) [5] | Retains tensile strength for >2 years [5] [1] | Minimal tissue reaction [5] |

| Nylon | Synthetic, Non-Absorbable, Monofilament | High | Tensile strength decreases 15-25% per year in vivo [1] | Low tissue reactivity [1] |

Further physical properties are critical for handling and performance. Suture size, denoted by the U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) system ranging from 12-0 (smallest) to 10 (largest), directly influences tensile strength and tissue drag [5]. The physical configuration—monofilament versus multifilament (braided or twisted)—also presents a trade-off: monofilaments exhibit lower tissue reactivity and reduced risk of infection, while multifilaments generally offer superior knot security and handling [5] [2]. Research indicates that multifilament constructions (e.g., VICRYL, silk) can score higher in tenacity, toughness, and knot tensile strength compared to monofilaments like polypropylene [5].

Experimental Protocols for Suture Evaluation

Robust and standardized experimental methodologies are paramount for characterizing suture materials in a research and development setting. The protocols below are adapted from current literature and international standards.

Protocol 1: Tensile Strength and Elongation at Break

Objective: To determine the ultimate tensile strength and elongation of suture materials under a controlled, uniaxial load, simulating the mechanical stresses encountered in vivo.

Materials & Reagents:

- Universal Testing Machine (UTM) equipped with a calibrated load cell (e.g., 100 N capacity)

- Standardized suture samples (e.g., 20-30 cm lengths)

- Micrometer for precise diameter measurement

- Environmental chamber (optional, for conditioned testing)

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Cut a minimum of six specimens per suture type to a standardized length. Measure and record the diameter of each specimen at three points along its length using a micrometer [5] [2].

- UTM Setup: Mount the specimen in the UTM grips, ensuring it is aligned axially. Set the gauge length (distance between grips) to a standardized distance, typically 10 mm [2].

- Testing Parameters: Program the UTM to apply a tensile load at a constant crosshead speed of 50 mm/min until failure [2].

- Data Collection: The UTM software will generate a force-elongation curve. Record the Breaking Force (N) and the Elongation at Break (%).

- Data Analysis: Calculate the mean and standard deviation for each suture group. Statistical analysis (e.g., one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey test) should be performed to identify significant differences between materials (p < 0.05) [5] [2].

Protocol 2: In Vitro Hydrolytic Degradation and Strength Retention

Objective: To simulate the in vivo absorption process and quantify the loss of mechanical strength over time, a critical parameter for absorbable sutures.

Materials & Reagents:

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) or Ringer's Solution (8.6 g/L NaCl, 0.3 g/L KCl, 0.33 g/L CaCl₂·2H₂O) [4]

- Temperature-controlled incubator or water bath (set to 37°C ± 1°C)

- Sealed containers for solution immersion

- Universal Testing Machine (as in Protocol 1)

Methodology:

- Baseline Testing: Perform tensile strength testing on a representative set of fresh suture samples (Group T=0) as per Protocol 1.

- Solution Immersion: Place the remaining test samples in individual containers filled with a sufficient volume of pre-warmed PBS or Ringer's solution to fully submerge them. Seal the containers to prevent evaporation and place them in the incubator at 37°C [4].

- Sampling Interval: Remove a cohort of samples (e.g., n=6-8) at predetermined time intervals relevant to the suture's expected absorption profile (e.g., days 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, 28) [4].

- Post-Immersion Testing: Gently rinse the retrieved samples with deionized water and pat dry. Immediately subject them to tensile testing as described in Protocol 1.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of original tensile strength retained at each time point: (Strength at Time T / Baseline Strength) x 100%. Plot the strength retention profile over time to model the degradation kinetics [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

For researchers embarking on the evaluation of suture materials, the following table catalogues essential tools and their specific functions in a experimental workflow.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Suture Characterization

| Research Tool / Reagent | Primary Function in Suture Research |

|---|---|

| Universal Testing Machine (UTM) | The cornerstone instrument for quantifying key mechanical properties including tensile strength, elongation at break, and modulus [5] [2]. |

| Ringer's Solution / PBS | Isotonic solutions used in in vitro degradation studies to simulate the biological environment and initiate hydrolytic degradation of absorbable sutures [4]. |

| Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) | Used for high-resolution imaging of suture surface morphology, degradation patterns, and structural integrity before and after testing [2]. |

| Micrometer / Digital Caliper | Provides precise measurement of suture diameter, a critical variable that correlates with tensile strength and is required for standardized reporting [5]. |

| Cell Viability Assays (e.g., MTT) | In vitro biocompatibility tests to assess the cytotoxicity of suture materials or their degradation byproducts on cultured cell lines [2]. |

| Temperature-Controlled Incubator | Maintains a constant 37°C environment for degradation studies, accelerating hydrolysis and mimicking physiological temperature [4]. |

| Prudomestin | Prudomestin | High-Purity Research Compound |

| (+)-Intermedine | (+)-Intermedine, CAS:146-68-9, MF:C19H13IN5O2.Cl, MW:505.7 g/mol |

The rational selection between absorbable and non-absorbable sutures is a critical decision point in both clinical practice and biomaterials research, hinging on a deep understanding of their defining characteristics. Absorbable sutures offer the key advantage of autonomous degradation, eliminating the need for removal and reducing long-term foreign body presence, but require precise matching of their strength retention profile to the tissue's healing timeline. Non-absorbable sutures provide dependable, long-term mechanical support but may necessitate a secondary removal procedure or remain as a permanent implant.

The future of suture technology, as indicated by market and research trends, is moving toward "smart" functionalities. The biodegradable smart suture market is projected to grow significantly, driven by innovations such as sutures capable of controlled drug delivery and responsiveness to environmental changes like pH or temperature [8]. Furthermore, ongoing research into novel polymers, such as poly-4-hydroxybutyrate (P4HB), and the refinement of copolymer compositions promise next-generation sutures with enhanced biocompatibility and precisely engineered degradation rates [1] [9]. This evolution underscores the importance of the fundamental characterization protocols outlined herein, which provide the essential toolkit for developing and evaluating the advanced suture materials of tomorrow.

Surgical sutures are fundamental medical devices designed to approximate tissue and secure wound closure until the healing process provides sufficient strength. The ideal suture material balances multiple properties: high tensile strength, excellent handling and knot security, minimal tissue reactivity, predictable degradation, and sterility [10] [11]. Sutures are broadly classified as either natural (derived from biological sources like animal intestines or silk worm filaments) or synthetic (manufactured through chemical polymerization) [12]. A critical distinction lies in their fate within the body: absorbable sutures are designed to degrade and lose tensile strength within weeks to months, while non-absorbable sutures maintain their strength for longer than 2-3 months [13] [1]. The selection of a specific suture material is a critical surgical decision that directly influences wound healing, infection risk, and cosmetic outcome [12].

This review provides a detailed comparison of six key materials—catgut, silk, polyglycolide (PGA), polylactide (PLA), polydioxanone (PDO), and poly-4-hydroxybutyrate (P4HB)—framed within ongoing research on degradable biomaterials. We present standardized experimental data and protocols to support preclinical evaluation and material selection for research and drug development applications.

Material Properties and Performance Data

Quantitative Comparison of Suture Materials

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Suture Materials

| Material | Classification | Absorption Time (Days) | Tensile Strength Retention | Primary Degradation Mechanism | Tissue Reaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catgut | Natural, Absorbable | 60-70 [13] | Lost by 60 days [13] | Proteolytic enzymatic degradation [1] | Moderate to Severe [14] |

| Silk | Natural, Non-Absorbable | N/A (Non-absorbable) [1] | Retains strength >2 months [1] | Not applicable; encapsulation in tissue | Moderate [5] |

| PGA | Synthetic, Absorbable | 60-90 [13] | ~50% at 2-3 weeks [15] | Hydrolysis [13] | Minimal [13] |

| PLA | Synthetic, Absorbable | 180+ [13] | Prolonged (>6 months) [15] | Hydrolysis [13] | Minimal [13] |

| PDO | Synthetic, Absorbable | 180+ [13] | ~70% at 4 weeks, ~50% at 6 weeks [13] | Hydrolysis [13] | Minimal [13] |

| P4HB | Synthetic, Absorbable | 365-540 [15] | ~65% at 12 weeks [14] | Hydrolysis & surface erosion [15] | Minimal [14] |

Table 2: Experimental Mechanical and Functional Performance

| Material | Structure | Key Functional Advantages | Key Functional Limitations | Common Trade Names |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catgut | Monofilament or Twisted [13] | Rapid absorption, proven history | High tissue reactivity, unpredictable absorption [14] | Chromic Catgut [14] |

| Silk | Braided Multifilament [5] | Excellent handling & knot security [5] | High capillarity, infection risk, moderate reactivity [5] | Silk, Virgin Silk [13] |

| PGA | Braided Multifilament [13] | High initial strength, predictable absorption [13] | Stiff, can saw through tissue [13] | Dexon [13] |

| PLA | Various [13] | Long-term strength retention [15] | Slow degradation, acidification upon hydrolysis [15] | Orthodek [13] |

| PDO | Monofilament [13] | Flexibility, good knot strength [13] | Slow absorption, potential for late inflammation [13] | PDS, PDS II [13] |

| P4HB | Monofilament [15] | High elasticity, biocompatible degradation product [15] | Higher cost, specialized production [15] | TephaFlex [13] [15] |

Analysis of Comparative Data

The data reveals a clear evolutionary pathway from natural to advanced synthetic materials. Natural materials like catgut and silk, while historically important, are characterized by significant biological reactivity and unpredictable degradation profiles [14] [5]. In contrast, synthetic materials (PGA, PLA, PDO, P4HB) offer superior control over mechanical properties and absorption kinetics, leading to minimized tissue reaction [13]. The global absorbable sutures market, valued at USD 3 billion in 2024, is dominated by synthetic materials, which hold a 71.4% market share due to these advantages [16].

PGA and PLA, among the first-generation synthetic absorbables, degrade via hydrolysis of their ester bonds, producing predictable strength loss profiles [13]. PDO offers a good balance of flexibility and strength retention, making it suitable for tissues requiring extended support [13]. P4HB represents a significant advancement; it is a bacterial-derived polyester that is FDA-approved and exhibits exceptional elasticity, with degradation products that are natural human metabolites [15]. Its degradation profile, spanning 12-18 months for complete resorption, makes it ideal for applications like soft tissue repair where long-term, gentle support is needed [15].

Experimental Protocols for Suture Evaluation

Protocol 1: In Vitro Degradation and Strength Retention

Objective: To quantitatively assess the mass loss, molecular weight change, and tensile strength retention of absorbable suture materials under simulated physiological conditions.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4: Simulates physiological pH.

- Lipase Solution (e.g., from Pseudomonas cepacia): Models enzymatic degradation for certain polymers [14].

- Incubator: Maintained at 37°C.

- Tensile Testing Machine: Equipped with a small-load cell (e.g., 50 N capacity).

- Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC): For monitoring changes in molecular weight.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Cut suture samples to standardized lengths (e.g., 20 cm). Record initial mass and diameter. For braided sutures, ensure consistent pre-tensioning during measurement.

- Immersion Study: Aseptically place samples in sterile containers with PBS or lipase solution. Maintain a consistent buffer-to-suture mass ratio (e.g., 20:1). Incubate at 37°C [14].

- Time-Point Sampling: Remove samples in triplicate at predetermined intervals (e.g., 1, 2, 4, 8, 12 weeks).

- Analysis:

- Mass Loss: Rinse retrieved samples with deionized water, dry to constant weight in a vacuum desiccator, and calculate percentage mass loss.

- Molecular Weight: Dissolve dried suture fragments in appropriate solvent (e.g., Hexafluoroisopropanol for PDO, P4HB) and analyze via GPC to determine Mn and Mw [14].

- Tensile Strength: Perform uniaxial tensile tests on wet samples according to ASTM F2548. Clamp a gauge length of suture and pull at a constant crosshead speed (e.g., 50 mm/min) until failure. Record peak load and calculate tensile strength [5].

Data Interpretation: Plot strength retention and molecular weight against time. Materials like PGA will show a rapid decline, whereas PDO, PLA, and P4HB will demonstrate more extended strength retention profiles [14] [13].

Protocol 2: In Vivo Biocompatibility and Tissue Response

Objective: To evaluate the local tissue reaction, foreign body response, and in vivo degradation kinetics of suture materials in a live animal model.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Animal Model: Female Sprague-Dawley rats (200-250 g).

- Suture Implantation Device: Trocar or large-bore needle.

- Histology Supplies: Formalin fixative, paraffin embedding station, microtome, Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E) stain, stain for macrophages (e.g., CD68 immunohistochemistry).

Methodology:

- Implantation: Anesthetize rats according to approved IACUC protocol. Make a small skin incision and implant pre-sterilized suture segments (e.g., 2 cm long) into the tergal muscle mass or subcutaneous tissue using a trocar. Implant negative control materials (e.g., USP polyethylene) concurrently [14].

- Explanation: Euthanize animals and explant the suture and surrounding tissue block at designated time points (e.g., 1, 4, 12, 26 weeks).

- Histopathological Analysis:

- Fix tissue blocks in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 48 hours.

- Process, embed in paraffin, and section to 5 µm thickness.

- Stain sections with H&E and analyze under light microscopy for inflammatory cell infiltration (neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages), fibrosis, and capsule formation.

- Score the foreign body reaction semi-quantitatively on a standardized scale (e.g., 0-4) for parameters like inflammation and fibrosis [14].

Data Interpretation: Compare the inflammatory scores and degradation progress of test materials against controls and each other. Catgut typically incurs a more pronounced and persistent cellular response, while advanced synthetics like P4HB show markedly milder reactions [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Suture Material Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) | Model braided synthetic absorbable suture | Positive control for in vitro hydrolysis and strength retention studies [5] [12]. |

| Polydioxanone (PDS) | Model monofilament, slow-absorbing suture | Benchmark for evaluating long-term (≥6 months) tissue response and strength loss [13]. |

| Lipase Enzyme (P. cepacia) | Catalyst for accelerated in vitro polymer degradation | Simulating enzymatic degradation of aliphatic polyesters like P4HB in buffer solutions [14]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Simulates physiological pH environment | Standard medium for in vitro hydrolysis studies under controlled, non-enzymatic conditions [14]. |

| Triclosan-coated Sutures (Vicryl Plus) | Antimicrobial suture model | Studying efficacy in reducing bacterial biofilm formation and surgical site infections (SSI) [12]. |

| 1-Bromoadamantane | 1-Bromoadamantane (1-Adamantyl Bromide) >99.0% | |

| 5-Methylindole | 5-Methylindole, CAS:614-96-0, MF:C9H9N, MW:131.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Research Workflow and Material Selection Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for selecting and evaluating suture materials in a research context, integrating the key concepts and protocols discussed.

Biodegradation is a critical process in biomedical engineering, particularly for the development of advanced degradable suture materials and implants. These materials are designed to perform their therapeutic function and then safely break down within the body, eliminating the need for secondary removal surgeries and reducing long-term complications [17]. The degradation process in biological environments occurs through three primary, often interconnected, mechanisms: hydrolysis, enzymatic degradation, and cellular phagocytosis. Understanding these mechanisms at a fundamental level enables researchers to design materials with tailored degradation profiles that match tissue healing timelines, thereby optimizing clinical outcomes [17] [18]. This document provides a detailed overview of these mechanisms, supported by experimental protocols and data analysis tools, specifically framed within research on next-generation suture materials.

Mechanism 1: Hydrolysis

Principle and Key Factors

Hydrolysis is a chemical process where polymer chains are cleaved through the reaction with water molecules. This mechanism is particularly dominant in synthetic biodegradable polymers used in sutures, such as polyglycolic acid (PGA), polylactic acid (PLA), and polydioxanone (PDS) [19] [18]. The process occurs without direct cellular involvement and is influenced by both the intrinsic properties of the polymer and the external environment.

The rate of hydrolytic degradation is governed by several key factors [20]:

- Chemical Structure: Polymers with hydrolytically labile bonds in their backbone, such as esters, carbonates, and amides, degrade more rapidly.

- Hydrophobicity/ Hydrophilicity Balance: Hydrophilic polymers tend to absorb more water, accelerating the hydrolysis process. Computational LogP(SA)â»Â¹ values can predict this behavior, with negative values indicating higher water affinity and potentially faster degradation [20].

- Glass Transition Temperature (Tg): Polymers with a lower Tg have more chain mobility, which can facilitate water penetration and increase degradation rates.

- Crystallinity: The amorphous regions of a polymer are more accessible to water and degrade faster than the crystalline regions.

Experimental Protocol: Monitoring Hydrolytic DegradationIn Vitro

Objective: To quantify the hydrolytic degradation rate of a novel albumin-based suture material under simulated physiological conditions [19].

Materials:

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS): pH 7.4, to simulate physiological pH.

- Suture Samples: Pre-cut to standardized lengths (e.g., 2 cm) and weights.

- Incubation Vessels: Hermetic containers to prevent evaporation.

- Analytical Balance: Precision of ±0.01 mg.

- Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) System: For monitoring changes in molecular weight.

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM): For examining surface erosion.

Procedure:

- Baseline Characterization: Weigh each suture sample (W₀) and characterize initial molecular weight (Mₙ₀, Mᵂ₀) via GPC.

- Immersion: Immerse samples in PBS maintained at 37°C in an incubator. Use a high surface-to-volume ratio of PBS to sample to ensure sink conditions.

- Sampling: At predetermined time points (e.g., 1, 2, 4, 8, 12 weeks), retrieve triplicate samples from the PBS.

- Mass Loss Analysis: Rinse retrieved samples with deionized water, dry to constant weight in a vacuum desiccator, and record the dry weight (Wₜ).

- Molecular Weight Analysis: Analyze the dried samples using GPC to determine the remaining molecular weight (Mₙₜ, Mᵂₜ).

- Morphological Analysis: Examine the surface morphology of the dried samples using SEM to identify cracking, pitting, or surface erosion features.

Data Analysis:

- Mass Loss (%) = [(W₀ - Wₜ) / W₀] × 100

- Molecular Weight Retention (%) = (Mₙₜ / Mₙ₀) × 100

- Fit the mass loss and molecular weight data to kinetic models (e.g., first-order) to determine the degradation rate constant.

Table 1: Key Properties Influencing Hydrolytic Degradation Rates of Suture Polymers

| Polymer | Labile Bond | Typical Tg (°C) | Crystallinity | Relative Degradation Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyglycolic Acid (PGA) | Ester | 35-40 | High | Fast [20] |

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Ester | 55-60 | Medium | Slow [20] |

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | Ester | (-60) - (-65) | Low | Medium [20] |

| Polydioxanone (PDS) | Ester, Ether | ~ -10 | Medium | Medium |

Figure 1: Mechanism and Key Influencing Factors of Hydrolytic Degradation.

Mechanism 2: Enzymatic Degradation

Principle and Key Factors

Enzymatic degradation involves the specific cleavage of polymer chains by biologically active enzymes, such as proteases, esterases, and lipases [20] [21]. This mechanism is often more specific and faster than hydrolysis alone and is a key degradation route for natural polymer-based sutures like catgut, silk, and albumin [19]. Enzymes act as biological catalysts, lowering the activation energy required for bond scission.

The efficiency of enzymatic degradation depends on:

- Enzyme-Substrate Specificity: The enzyme must recognize and bind to specific chemical structures on the polymer.

- Surface Accessibility: Enzymes are too large to penetrate dense polymer matrices, so degradation is primarily a surface-erosion process.

- Environmental Conditions: Local pH and temperature can dramatically affect enzyme activity.

- Presence of Inhibitors or Activators: Other molecules in the biological milieu can modulate enzyme function.

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Enzymatic Degradation Kinetics

Objective: To determine the degradation profile of a silk fibroin suture in the presence of a protease enzyme solution [17] [18].

Materials:

- Enzyme Solution: Protease from Streptomyces griseus (e.g., 1 U/mL) in Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.8).

- Inactivated Enzyme Control: Enzyme solution boiled for 10 minutes to denature the enzyme.

- Suture Samples: Pre-weighed and characterized.

- Orbital Shaker: For constant, gentle agitation.

- UV-Vis Spectrophotometer: For analyzing protein release (e.g., absorbance at 280 nm).

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare the active and inactivated enzyme solutions.

- Immersion: Immerse triplicate suture samples in both the active and control solutions. Maintain at 37°C with constant agitation.

- Sampling: At regular intervals, withdraw a small aliquot (e.g., 1 mL) from the supernatant and replace with fresh buffer or enzyme solution to maintain volume and activity.

- Analysis of Soluble Products:

- Measure the absorbance of the supernatant at 280 nm to quantify the release of soluble protein fragments.

- Alternatively, use the BCA or Bradford assay for more precise protein quantification.

- Sample Retrieval: At major time points, retrieve entire suture samples for mass loss, GPC, and SEM analysis, as described in the hydrolysis protocol.

Data Analysis:

- Plot the concentration of soluble degradation products vs. time.

- Model the degradation kinetics using the Michaelis-Menten equation to determine Vₘâ‚â‚“ (maximum degradation rate) and Kₘ (Michaelis constant).

- The Haldane-Andrews model can be applied if high substrate concentrations (e.g., high suture mass) inhibit the enzyme [21].

Table 2: Common Enzymes in Biodegradation of Suture Materials

| Enzyme Class | Target Polymer/Bond | Relevant Suture Material |

|---|---|---|

| Proteases | Peptide bonds | Albumin, Collagen, Silk [19] |

| Esterases | Ester bonds | PGA, PLA, PCL [20] |

| Lipases | Ester bonds (in lipids) | Polyurethanes, PCL [20] |

| Collagenases | Collagen triple helix | Catgut |

Mechanism 3: Cellular Phagocytosis

Principle and Key Factors

Cellular phagocytosis is an active, energy-dependent process where specialized immune cells, primarily macrophages, engulf and internalize small particles or fragments of degraded material [22]. This process is crucial for the final clearance of degradation products and is intimately linked to the inflammatory and tissue-repair response [17]. When an implant degrades via hydrolysis or enzymes to micro- and nano-scale fragments, phagocytes can clear these fragments.

The process is highly regulated by "eat-me" signals [22]:

- Phosphatidylserine (PS) Exposure: In apoptotic cells, PS is externalized to the outer leaflet of the membrane, acting as a primary "eat-me" signal for phagocytes.

- Receptor Recognition: Phagocytes express receptors (e.g., TAM family receptors MerTK and Axl, Tim-4) that bind to these signals.

- Cytoskeletal Rearrangement: Upon binding, the phagocyte's actin cytoskeleton reorganizes to extend pseudopods and engulf the target.

- Formation of Phagolysosome: The internalized material is trafficked to lysosomes, where it is degraded by potent acidic hydrolases [23].

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Macrophage-Mediated Phagocytosis of Suture Fragments

Objective: To visualize and quantify the uptake of fluorescently-labeled suture fragments by macrophages in vitro.

Materials:

- Macrophage Cell Line: e.g., RAW 264.7 or primary bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs).

- Fluorescent Suture Fragments: Micronized suture material labeled with a stable fluorophore (e.g., FITC).

- Cell Culture Facilities: Including COâ‚‚ incubator and sterile hood.

- Confocal Microscope: For high-resolution imaging.

- Flow Cytometer: For quantitative analysis.

- Inhibitors: e.g., Cytochalasin D (actin polymerization inhibitor) as a negative control.

Procedure:

- Fragment Preparation: Generate and sterilize micron-sized fragments of the suture material. Label with a non-toxic fluorescent dye.

- Cell Seeding: Seed macrophages into multi-well plates (containing coverslips for microscopy) and allow to adhere overnight.

- Treatment: Incubate cells with fluorescent suture fragments at a predetermined particle-to-cell ratio. Include wells with cytochalasin D pre-treatment to confirm phagocytosis is energy-dependent.

- Incubation: Incubate for 2-6 hours.

- Analysis:

- Confocal Microscopy: Fix cells, stain actin cytoskeleton (e.g., with phalloidin) and nuclei (DAPI). Image to visualize internalized fragments.

- Flow Cytometry: Trypsinize and collect cells. Analyze the fluorescence intensity of the cell population, which corresponds to fragment uptake.

Data Analysis:

- Quantify the percentage of fluorescent-positive cells via flow cytometry.

- Determine the mean fluorescence intensity, which indicates the average phagocytic load per cell.

- From microscopy images, count the number of particles per cell.

Figure 2: Cellular Phagocytosis Pathway for Suture Fragment Clearance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Biodegradation Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Samples | Base material for suture development and degradation testing. | Human Serum Albumin (HSA) for novel composite sutures [19]. |

| Protease Enzyme | Catalyzes enzymatic degradation of protein-based sutures. | Testing degradation kinetics of silk fibroin sutures [17]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Provides a simulated physiological environment for hydrolysis studies. | In vitro immersion studies for mass loss and molecular weight change [19]. |

| RAW 264.7 Cell Line | A murine macrophage cell line for phagocytosis assays. | Quantifying cellular uptake of fluorescent suture fragments. |

| Cytochalasin D | Inhibitor of actin polymerization; negative control for phagocytosis. | Confirming that particle uptake is an energy-dependent process. |

| Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) | Analyzes changes in polymer molecular weight distribution over time. | Tracking the chain scission and erosion of synthetic polymers like PLA [20]. |

| Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) | Visualizes surface morphology and erosion patterns of degrading materials. | Identifying pitting, cracking, or surface roughening on sutures after in vitro testing [19]. |

| Jatrophane 3 | Jatrophane 3, CAS:210108-87-5, MF:C43H53NO14 | Chemical Reagent |

| (+)-Isoajmaline | (+)-Isoajmaline|Research Chemical|RUO | High-purity (+)-Isoajmaline for research applications. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO) and is not intended for diagnostic or personal use. |

The field of regenerative medicine is increasingly focused on the development of advanced biomaterials that provide temporary mechanical support and actively promote tissue healing without requiring surgical removal. Among these, degradable suture materials represent a critical area of innovation, balancing the requirements of mechanical integrity, biocompatibility, and controlled degradation. Traditional polymeric sutures, while widely used, face limitations including suboptimal tissue integration, potential cytotoxicity, and mechanical mismatch with native tissues. This has spurred research into three promising material categories: albumin-based composites, biodegradable metals (magnesium, iron, and zinc alloys), and graphene-enhanced sutures. These advanced materials offer unique advantages for tissue engineering applications, from enhanced biocompatibility and bioactive functionality to superior mechanical properties that can be tailored to specific clinical needs. This article provides a comprehensive overview of the current state of these emerging biomaterials, with detailed experimental protocols and performance data to guide research and development efforts.

Material Classes and Performance Characteristics

Albumin-Based Composite Sutures

Human serum albumin (HSA) has emerged as a promising base material for biodegradable sutures due to its excellent biocompatibility, natural origin, and biodegradability. Research demonstrates that albumin-based sutures can be fabricated using extrusion methodology to create filaments with tunable mechanical properties suitable for various medical applications [24].

Table 1: Mechanical Properties of Albumin-Based Composite Sutures

| Material Composition | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elongation at Break (%) | Key Characteristics | Potential Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filament Suture (FS) from HSA | 1.3 - 9.616 | 11.5 - 146.64 | Biocompatible, biodegradable, tunable mechanical properties | Soft tissue repair, 3D printing of medical devices (plates, nails) |

| HSA with gelatin additives | Data not specified | Data not specified | Enhanced cell adhesion, improved handling characteristics | Wound closure, tissue engineering scaffolds |

The mechanical versatility of albumin-based sutures is evident from the broad range of tensile strengths and elongation percentages achievable through modifications in processing parameters and additive incorporation. These sutures can be further enhanced with biodegradable organic modifiers to improve their mechanical performance and biological interactions [24]. The fundamental advantage of albumin lies in its status as a natural blood component, which minimizes immune reactions and supports natural healing processes.

Biodegradable Metal Sutures and Fasteners

Biodegradable metals represent a revolutionary approach to temporary implantable devices, combining the mechanical strength of metals with the resorbability of biodegradable materials. The three primary metal systems under investigation are magnesium (Mg), zinc (Zn), and iron (Fe) based alloys.

Table 2: Comparison of Biodegradable Metals for Surgical Applications

| Metal Type | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Degradation Rate | Key Advantages | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnesium Alloys (e.g., ZK60) | 41-45 [25] | 65-100 [25] | Fast (can be too rapid) | Promotes bone formation, excellent biocompatibility, similar modulus to bone | Hydrogen gas evolution, alkalization, rapid corrosion [25] |

| Zinc Alloys (e.g., Zn-Cu-Mn-Ti) | 90-110 [26] | 75-160 [26] | Intermediate (ideal for many applications) | Good biocompatibility, nutrient element, no gas evolution | Lower strength and plasticity in pure form [26] |

| Iron Alloys | 180-210 [26] | 50-1450 [26] | Slow (may be too slow) | High strength, familiar processing techniques | Very slow degradation, potential inflammation from corrosion products [26] |

Recent advances in magnesium alloys include the development of fluoridized ZK60 suture anchors for rotator cuff repair, which demonstrated superior osseointegration and new bone formation compared to titanium anchors in goat models [27]. Similarly, zinc alloys have shown remarkable progress with novel compositions like Zn-1.0Cu-0.2Mn-0.1Ti exhibiting excellent mechanical properties for surgical staples, with corrosion rates of approximately 0.02 mm/year in Hank's balanced salt solution and 0.12 mm/year in fed-state simulated intestinal fluid [28]. The varying degradation rates depending on physiological environment make these materials particularly suitable for site-specific applications.

Graphene-Enhanced Sutures

The integration of carbon-based nanomaterials with traditional suture materials has opened new frontiers in bioactive wound closure devices. Research demonstrates that coating resorbable poly(glycolide-co-lactide) (PGLA) sutures with bioactive glass nanopowders (BGNs) and graphene oxide (GO) imparts significant bioactivity and enhances wound healing properties [29].

These composite coatings create stable, homogeneous surfaces on sutures that promote fibroblast attachment, migration, and proliferation. Additionally, they stimulate the secretion of angiogenic growth factors that accelerate wound healing. The GO component enhances the electrical conductivity and mechanical strength of the coatings, while the BGNs contribute bioactive ions that support cellular functions [29]. The combination results in sutures that not only provide physical support but actively modulate the wound environment to facilitate regeneration.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication and Characterization of Albumin-Based Sutures

Materials Required:

- Human serum albumin (HSA) or bovine serum albumin (BSA)

- Gelatin powder (additive material)

- Extrusion equipment with temperature control

- Tensile testing machine

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

- Thermogravimetric analyzer (TGA)

Procedure:

- Material Preparation: Prepare HSA solution according to manufacturer specifications. For composite formulations, add gelatin powder at concentrations ranging from 0.5–50 μg/mL [24].

- Extrusion Process: Utilize sub-critical water technology and extrusion methodology to form filament sutures (FS). Optimize temperature and pressure parameters to achieve desired filament diameter [24].

- Mechanical Testing: Evaluate tensile strength and elongation at break using standardized tensile testing protocols. Target values should range from 1.3 to 9.616 MPa for tensile strength and 11.5% to 146.64% for elongation at break [24].

- Morphological Analysis: Characterize surface morphology and cross-sectional structure using SEM imaging.

- Thermal Analysis: Determine thermal stability using TGA with a temperature ramp from ambient to 600°C.

Quality Control:

- Ensure consistent filament diameter throughout the length

- Verify absence of surface defects or irregularities

- Confirm reproducible mechanical properties across batches

Protocol 2: Preparation and Evaluation of Magnesium Alloy Suture Anchors

Materials Required:

- ZK60 magnesium alloy (Mg-6.0Zn-0.5Zr)

- 42% hydrofluoric acid

- Titanium anchors (control)

- CNC machining equipment

- Ultrasonic cleaner

- Orbital shaker

- Computed tomography (CT) imaging system

Procedure:

- Anchor Fabrication: Machine ZK60 alloy into anchors with diameter of 5 mm and length of 15 mm using CNC machining [27].

- Surface Treatment: Clean anchors ultrasonically in ethanol and deionized water for 5 minutes each.

- Fluoride Coating: Immerse anchors in 42% hydrofluoric acid at room temperature with shaking at 70 rpm for 24 hours to create MgFâ‚‚ coating [27].

- Post-treatment Cleaning: Ultrasonically clean coated anchors in ethanol and deionized water for 5 minutes each.

- Sterilization: Sterilize anchors with 75% ethanol prior to implantation.

- In Vivo Evaluation: Implant anchors in animal model (e.g., goat rotator cuff) and evaluate at 4, 8, and 12 weeks using CT imaging and histological analysis [27].

Assessment Parameters:

- New bone formation quantification

- Osseointegration quality

- Tendon healing assessment

- Local tissue response

Protocol 3: Application of Graphene Oxide/Bioglass Coatings on Sutures

Materials Required:

- PGLA sutures (90:10%)

- Bioactive glass nanopowders (BGNs)

- Graphene oxide (GO) solution

- Vacuum sol deposition apparatus

- Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) equipment

- Cell culture facilities (L929 fibroblast cells)

Procedure:

- Coating Preparation: Synthesize GO-doped melt-derived BGNs via sol-gel process [29].

- Surface Coating: Apply BGNs and BGNs/GO coatings to resorbable PGLA sutures using optimized vacuum sol deposition method [29].

- Characterization: Analyze chemical structure using FTIR spectroscopy in the range of 400–4000 cmâ»Â¹.

- Morphological Examination: Examine surface morphology and coating homogeneity using field emission scanning electron microscopy with elemental analysis.

- In Vitro Bioactivity: Evaluate bioactivity through immersion in simulated body fluid and monitoring of hydroxyapatite formation.

- Cellular Response: Assess fibroblast attachment, migration, and proliferation using L929 cell line.

Quality Metrics:

- Coating stability and homogeneity

- Enhanced fibroblast attachment and proliferation

- Accelerated angiogenic growth factor secretion

- Improved wound healing in in vivo models

Signaling Pathways and Biological Mechanisms

The bioactive materials described herein promote healing through modulation of critical cellular signaling pathways. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for optimizing material design and predicting clinical performance.

Magnesium ions released during degradation stimulate bone formation and improve osseointegration, as demonstrated in fluoridized ZK60 suture anchors that showed superior new bone formation compared to titanium controls [27]. Zinc alloys with nutrient elements (such as strontium) trigger signaling pathways that promote both angiogenesis and osteogenesis, creating a favorable environment for bone regeneration [26]. Bioactive glass coatings contribute ions that enhance cell adhesion and migration while stimulating angiogenic factors, particularly important for soft tissue repair [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Degradable Suture Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Human Serum Albumin (HSA) | Base material for albumin-based sutures | Use first grade purity; source from reputable suppliers (e.g., Wako Pure Chemical Industries) [24] |

| ZK60 Magnesium Alloy | Biodegradable metal for suture anchors | Composition: Mg-6.0Zn-0.5Zr; requires MgFâ‚‚ coating for corrosion resistance [27] |

| Zn-Based Alloys | Biodegradable staples and sutures | Optimal compositions: Zn-1.0Cu-0.2Mn-0.1Ti, Zn-1.0Mn-0.1Ti, Zn-1.0Cu-0.1Ti [28] |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) | Coating component for enhanced bioactivity | Enhances electrical conductivity, mechanical strength, and bioactivity [29] |

| Bioactive Glass Nanopowders (BGNs) | Coating component for tissue integration | Promotes fibroblast attachment and proliferation; enhances wound healing [29] |

| Hydrofluoric Acid | Surface treatment for Mg alloys | 42% concentration for MgFâ‚‚ coating formation; requires careful handling [27] |

| Cyprodenate | Cyprodenate, CAS:15585-86-1, MF:C13H25NO2, MW:227.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Csf1R-IN-13 | Csf1R-IN-13, MF:C21H20N4O3, MW:376.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The development of advanced degradable suture materials represents a multidisciplinary frontier in regenerative medicine. Albumin-based composites offer exceptional biocompatibility and tunable mechanical properties. Biodegradable metals, particularly magnesium and zinc alloys, provide superior strength and osseointegration capabilities for load-bearing applications. Graphene-enhanced sutures introduce bioactive functionality that actively promotes healing through cellular interactions. Each material class presents unique advantages and challenges that must be carefully considered for specific clinical applications. The protocols and data presented herein provide a foundation for further research and development in this rapidly evolving field, with the ultimate goal of creating next-generation surgical materials that enhance healing outcomes while eliminating the need for secondary removal procedures.

The structural design of a suture—specifically, whether it is constructed as a monofilament or multifilament thread—is a fundamental determinant of its in vivo performance and degradation behavior. These structural categories present distinct trade-offs in mechanical properties, tissue reactivity, and functional longevity, making the choice critical for specific clinical and research applications [30] [31]. Within the context of degradable biomaterials, this selection directly influences the wound healing process and the success of a medical device implantation.

Monofilament sutures consist of a single, homogeneous filament of material, while multifilament (or braided) sutures are composed of multiple finer filaments twisted or braided together [30] [31]. This fundamental physical difference dictates a suture's interaction with both the host tissue and the biological environment, guiding researchers in selecting the appropriate model for simulating implantation scenarios. Understanding these performance trade-offs is essential for designing rigorous experimental protocols and accurately interpreting in vitro and in vivo data.

Structural Characteristics and Performance Trade-offs

Monofilament Sutures: Features and Performance Profile

Monofilament sutures, fashioned from a single strand of material, are characterized by their smooth, uniform surface. This structural simplicity confers several key advantages in a research and clinical context.

- Low Tissue Drag and Trauma: Their smooth surface allows for effortless passage through tissue, minimizing drag and associated trauma [30]. This is a critical property for experiments involving delicate tissues or for simulating minimally invasive procedures.

- Reduced Infection Risk and Capillarity: The absence of inter-filament spaces eliminates the wicking effect known as capillarity, thereby preventing the migration of fluids and bacteria along the suture line [30] [31]. This makes them the preferred model for studies involving contaminated or infection-prone wound environments.

- Low Tissue Reactivity: Composed of inert synthetic polymers and presenting a minimal surface area, monofilaments typically elicit a lower inflammatory response compared to multifilament structures [30]. This is a key consideration for experiments where minimizing the host immune response is a variable.

However, the monofilament design also presents significant trade-offs:

- Handling and Knot Security: These sutures are often stiffer and possess high "memory," a tendency to return to their packaged coiled state, which can complicate handling and knot tying [30] [31]. Their smooth surface also results in lower friction, often requiring additional knot throws to ensure knot security [31].

- Mechanical Properties: While strong, some monofilament types may be more susceptible to nicking or fracturing if crushed with surgical instruments, a factor that must be controlled for in mechanical testing protocols [31].

Multifilament/Braided Sutures: Features and Performance Profile

Multifilament sutures, comprising several filaments woven or twisted together, offer a contrasting set of properties derived from their complex, multi-stranded architecture.

- Superior Handling and Knot Security: The braided structure provides exceptional pliability, making them easy for surgeons to handle and manipulate [30]. The increased surface friction grants excellent knot security, with knots holding firmly with fewer throws [30] [31].

- High Tensile Strength: The collective strength of multiple fine filaments often results in a higher tensile strength-to-diameter ratio compared to monofilaments [5]. This is a critical parameter for experiments requiring high mechanical integrity in the initial phases of healing.

- Flexibility and Pliability: Their inherent flexibility makes them well-suited for applications requiring the suture to conform to delicate or complex anatomical structures [30].

The primary disadvantages of multifilament sutures are directly linked to their structure:

- Capillarity and Infection Risk: The interstitial spaces between filaments can act as micro-conduits, drawing in fluids and bacteria through capillary action [30] [31]. This structure can harbor microorganisms, potentially leading to persistent infection, which limits their use in contaminated wound models [30] [32].

- Increased Tissue Reactivity and Drag: The larger, more textured surface area can cause increased friction ("tissue drag") during passage and may provoke a greater foreign body reaction [30] [31]. Natural multifilament sutures, like silk, are known for causing significant inflammation [31].

Table 1: Performance Trade-offs between Monofilament and Multifilament Sutures

| Performance Characteristic | Monofilament Sutures | Multifilament/Braided Sutures |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue Drag | Low [30] | High [30] |

| Knot Security | Lower (requires more throws) [30] [31] | Higher (secure with fewer throws) [30] [31] |

| Handling & Pliability | Stiffer, higher memory [30] [31] | Softer, more pliable [30] [31] |

| Risk of Infection/Capillarity | Low [30] [31] | High [30] [31] |

| Tissue Reactivity | Low [30] | Moderate to High [30] [31] |

| Tensile Strength (for diameter) | Generally high | Very high [5] |

Table 2: Common Suture Materials and Their Structural Classification

| Suture Material | Example Brand Names | Filament Type | Absorbability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyglactin 910 | Vicryl [5] | Multifilament | Synthetic Absorbable [31] |

| Poliglecaprone 25 | Monocryl [30] | Monofilament | Synthetic Absorbable [31] |

| Polydioxanone | PDS II [30] [33] | Monofilament | Synthetic Absorbable [31] |

| Polyglycolic Acid | Dexon [32] | Multifilament | Synthetic Absorbable |

| Silk | - [5] | Multifilament | Natural, Non-absorbable [31] |

| Polypropylene | Prolene [30] | Monofilament | Synthetic Non-absorbable [31] |

| Nylon | Ethilon [31] | Monofilament | Synthetic Non-absorbable [31] |

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Suture Performance

Protocol 1: In Vitro Degradation and Strength Retention Kinetics

Objective: To quantitatively assess the degradation profile and mechanical integrity of absorbable sutures under simulated physiological conditions over time.

Background: The degradation of synthetic absorbable sutures occurs primarily via hydrolysis, where water molecules cleave the polymer's ester bonds [4]. The rate of this process is influenced by the suture's material composition, structure, and environmental factors such as pH and enzyme presence [4] [34]. Monitoring the loss of tensile strength provides a critical metric for predicting functional performance in vivo.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

- Test Sutures: Absorbable monofilament (e.g., PDS II, Monocryl) and multifilament (e.g., Vicryl) sutures, USP size 3-0 [4] [33].

- Buffered Solutions: Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS, pH 7.4) to simulate physiological conditions. Acidic (pH ~5.6) and alkaline (pH ~8.8) buffers to simulate pathological or specific tissue environments [34] [33].

- Incubation System: Thermostatic water bath or incubator maintained at 37°C [4] [33].

- Mechanical Tester: Universal Testing Machine (e.g., Instron) equipped with a calibrated load cell [4] [34].

- Specimen Preparation:

- Prepare multiple suture loops for each test condition and time point (n=6-8 recommended for statistical power) [4] [33].

- Create loops by tying one surgical knot followed by four simple square knots using a standardized mandrel (e.g., a 10-mL syringe) to ensure consistent loop size [33].

- All procedures should be performed aseptically to prevent microbial contamination.

Methodology:

- Baseline Measurement (Day 0): Measure the initial tensile strength of non-immersed suture loops to establish a baseline [33].

- Immersion Study: Immerse prepared suture loops in the different buffered solutions. Ensure samples are fully submerged and incubated at 37°C [4] [33].

- Time-Point Sampling: Remove samples from incubation at predetermined intervals (e.g., Days 7, 14, 21, 28) for mechanical testing [4] [33].

- Tensile Strength Testing:

- Mount each loop on the Universal Testing Machine.

- Apply a pre-load (e.g., 1 N) to remove slack.

- Pull the loop at a constant crosshead speed (e.g., 60 mm/min) until failure [33].

- Record the maximum load at break (N).

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the percentage of original tensile strength retained at each time point:

(Strength at Time T / Baseline Strength) * 100. - Perform statistical analysis (e.g., ANOVA followed by post-hoc tests like Tukey HSD) to compare degradation profiles between suture types and across pH conditions [4] [5].

- Calculate the percentage of original tensile strength retained at each time point:

Figure 1: Workflow for in vitro degradation and strength retention testing of sutures.

Protocol 2: Impact of Dynamic Environmental pH on Suture Integrity

Objective: To evaluate the effect of fluctuating pH, simulating an oral or digestive environment, on the tensile strength of absorbable sutures.

Background: Sutures placed in the oral cavity or gastrointestinal tract are exposed to significant and rapid pH shifts due to food and beverage consumption [34]. This protocol simulates these conditions to provide a more clinically relevant assessment of suture performance in these challenging environments.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

- Test Sutures: Monofilament (e.g., PGCL) and multifilament (e.g., PGLA) absorbable sutures [34].

- Test Beverages/Solutions: Artificially synthesized tea, coffee, and cola solutions, along with artificial saliva as a control [34].

- Thermal Cycling Device: To simulate oral temperature fluctuations (e.g., between 5°C and 55°C) [34].

- Artificial Saliva: Standardized solution mimicking the ionic composition of human saliva.

- Universal Testing Machine: As in Protocol 1.

Methodology:

- Specimen Preparation: Prepare suture specimens as described in Protocol 1.

- Cyclic Exposure:

- Expose suture specimens to test beverages five times per day for 5 minutes per exposure.

- Between exposures, store specimens in artificial saliva at 37°C.

- Subject all specimens to thermal cycling (e.g., 40 cycles per day between 5°C and 55°C) to simulate intra-oral temperature changes [34].

- Time-Point Testing: Perform tensile strength testing on the Universal Testing Machine at defined intervals (e.g., Days 0, 3, 7, and 14) [34].

- Data Analysis: Analyze the maximum tensile strength at break across groups and time points to identify significant decreases in strength attributable to the beverage type and pH environment.

Quantitative Data and Analysis

Recent studies provide quantitative insights into the mechanical and degradation behaviors of different suture structures. The following tables consolidate key findings from the literature.

Table 3: Strength Retention Profile of Selected Absorbable Sutures Over Time In Vitro [4] [33]

| Suture Name | Structure | Material | ~50% Strength Retention | Complete Absorption |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SafilQuick+ | Multifilament | Polyglycolic Acid | 9-12 days [4] | ~42 days [4] |

| Monosyn Quick | Monofilament | Glyconate | 9-12 days [4] | 56 days [4] |

| Vicryl (Polysorb) | Multifilament | Polyglactin 910 | 50% at 3 weeks [33] | 56-70 days [33] |

| PDS II | Monofilament | Polydioxanone | 60% at 6 weeks [33] | 180-210 days [33] |

| Maxon | Monofilament | Polyglyconate | 50% at 4 weeks [33] | 180 days [33] |

Table 4: Tensile Strength Comparison of Suture Materials (Baseline, USP 3-0)

| Suture Material | Structure | Reported Maximum Tensile Load (Mean ± SD) | Source / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| VICRYL | Multifilament | Highest among tested (Silk, VICRYL, PP) [5] | Scientific Reports, 2025 |

| Polypropylene | Monofilament | Intermediate between VICRYL and Silk [5] | Scientific Reports, 2025 |

| Silk | Multifilament | Lowest among tested (Silk, VICRYL, PP) [5] | Scientific Reports, 2025 |

| Polysorb | Multifilament | 70.54 ± 7.42 N [33] | J Vet Med Sci, 2025 |

| Vicryl | Multifilament | 49.31 ± 4 N [33] | J Vet Med Sci, 2025 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Key Reagents and Equipment for Suture Performance Research

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Testing Machine | Measures tensile strength, elongation, and break load of suture materials. | Instron Testing System [34] |

| Thermal Cycling Device | Simulates in vivo temperature fluctuations, particularly for oral environment studies. | 5°C to 55°C cycling [34] |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | A standard isotonic solution for simulating physiological pH (7.4) in immersion studies. | pH 7.4 [33] |

| Ringer's Solution | A balanced salt solution with electrolytes, used for seasoning sutures to simulate body fluid exposure. | Sodium, Potassium, Calcium Chlorides [4] |

| Artificial Saliva | Mimics the chemical composition of human saliva for intra-oral suture studies. | Standardized ionic recipe [34] |

| Acidic & Alkaline Buffers | Simulate pathological conditions or specific tissue environments (e.g., infected wounds, urinary tract). | pH 5.6 (Acidic), pH 8.8 (Alkaline) [33] |

| HbF inducer-1 | HbF Inducer-1|Fetal Hemoglobin Activator|RUO | |

| Ascleposide E | Ascleposide E, MF:C19H32O8, MW:388.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The choice between monofilament and multifilament suture designs remains a balance of competing performance priorities. Monofilaments offer lower tissue reactivity and infection risk but can be challenging to handle. Multifilaments provide superior strength and ease of use but may potentiate infection and inflammation [30] [31]. For researchers, the decision must be guided by the specific biological and mechanical requirements of the experimental model, whether it prioritizes minimal immune response (favoring monofilaments) or requires superior initial strength and handling (favoring multifilaments).

Future research is directed toward developing advanced "smart" sutures that integrate functionalities like drug delivery and environmental responsiveness [17] [8]. Furthermore, standardizing robust in vitro test protocols that accurately predict in vivo performance, particularly under dynamic physiological conditions, is a critical ongoing challenge. A deep understanding of the fundamental trade-offs between suture structures, as outlined in these application notes, provides the essential foundation for this future innovation.

Figure 2: Decision pathway for selecting suture structure based on performance trade-offs. Green arrows indicate positive drivers, red arrows indicate negative trade-offs.

Strategic Selection and Advanced Implantation Techniques for Optimal Wound Closure

Suture selection is a critical determinant of surgical success, balancing the material's mechanical properties with the biological environment of the healing tissue. For researchers and drug development professionals working on next-generation degradable biomaterials, understanding the precise relationship between a suture's absorption profile, its tensile strength retention (TSR), and specific clinical requirements provides the foundation for intelligent material design [18]. The evolution from simple wound closure devices toward multifunctional, "smart" suture platforms underscores the need for a systematic framework that matches material capabilities to clinical applications [18] [8].

This guide provides a quantitative approach to suture selection grounded in material science principles, with structured experimental protocols for evaluating novel suture formulations. By establishing clear correlations between polymer composition, degradation kinetics, and mechanical performance requirements across tissue types, researchers can accelerate the development of optimized surgical materials that actively promote healing while minimizing complications.

Suture Material Properties and Quantitative Comparisons

Fundamental Suture Classification and Characteristics

Suture materials are fundamentally categorized by their degradation mechanism and timeline:

- Absorbable sutures: Undergo predictable degradation in the body through hydrolysis or enzymatic processes, eliminating the need for removal [35] [5]. Their utility depends on maintaining sufficient strength during the critical healing phase before absorption.

- Non-absorbable sutures: Remain at the implantation site unless removed, providing permanent structural support [35]. These materials typically elicit minimal tissue reaction but require removal in superficial applications.

Material construction further differentiates suture performance:

- Monofilament sutures: Comprise a single strand, offering smooth tissue passage and reduced infection risk but challenging handling characteristics [35] [36].

- Multifilament/Braided sutures: consist of multiple woven strands, providing superior knot security and handling but potentially increased capillarity and infection risk [35] [36].

Quantitative Analysis of Absorbable Suture Properties

Table 1: Tensile Strength Retention and Absorption Profiles of Common Absorbable Sutures

| Suture Material | 50% TSR Timeframe (Days) | Complete Absorption (Days) | Key Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) | 14-21 [37] | 56-70 [37] | General soft tissue approximation, subcutaneous closures [35] |

| Poliglecaprone 25 (Monocryl) | 7-14 [37] | 90-120 [35] [37] | Subcuticular skin closures, pediatric procedures [35] |

| Polydioxanone (PDS) | 28-42 [37] [38] | 180 [35] [37] [38] | Slow-healing tissues, fascial closures [35] |

| Polyglycolic Acid (Dexon) | 10-14 [38] | 60-90 [35] [38] | General soft tissue approximation [35] |

| Surgical Gut (Plain) | 7-10 [37] | 70-90 [37] | Mucosal tissues, superficial lacerations [35] |

| Surgical Gut (Chromic) | 10-21 [37] | 90 [37] | Mucosal tissues, episiotomy repair [35] |

Table 2: Mechanical Properties of Non-Absorbable Sutures

| Suture Material | Construction | Tensile Strength Profile | Key Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polypropylene (Prolene) | Monofilament | Minimal degradation over time [35] | Vascular anastomoses, hernia repair [35] |

| Nylon (Ethilon) | Monofilament | Gradual degradation (15-20% per year) [35] | Skin closures, microsurgery [35] |

| Polyester (Ethibond) | Braided | Permanent [35] | Cardiovascular procedures, tendon repair [35] |

| Silk | Braided | Gradual degradation over 1-2 years [35] [37] | Ligatures, oral surgery [35] |

| Surgical Steel | Monofilament | Permanent [35] | Orthopedic procedures, sternum closure [35] |

Material-Tissue Matching Framework

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for matching suture properties to tissue healing requirements:

Experimental Protocols for Suture Evaluation

Protocol 1: In Vitro Tensile Strength and Degradation Testing

Purpose: To quantitatively evaluate the tensile strength retention and absorption profile of novel absorbable suture materials under simulated physiological conditions.

Materials and Equipment:

- Universal testing machine (e.g., Instron) with environmental chamber [37]

- pH-controlled phosphate buffered solution (PBS, pH 7.4) at 37°C

- Suture samples (minimum n=10 per time point)

- Analytical balance (±0.1 mg precision)

- Sterile surgical gloves and instruments

Procedure:

- Baseline Measurement: Condition samples in PBS for 24 hours at 37°C. Measure initial diameter and perform baseline tensile testing (5 mm/min crosshead speed) until failure [5] [37].

- Accelerated Degradation: Immerse pre-weighed suture samples in PBS at 37°C with continuous agitation. Maintain sterile conditions throughout.

- Time-point Sampling: Retrieve samples at predetermined intervals (e.g., days 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, 42) for analysis.

- Strength Testing: At each interval, measure tensile strength (straight-pull and knot-pull configurations) and calculate percentage TSR relative to baseline [37].

- Mass Loss Analysis: Rinse retrieved samples, dry to constant weight, and calculate percentage mass loss.

- Morphological Assessment: Examine suture surface and cross-section using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to characterize degradation patterns.

Data Analysis:

- Plot TSR (%) versus time to generate degradation profiles

- Calculate absorption half-life and time to complete loss of mechanical integrity

- Compare experimental data against clinical requirements in Table 1

Protocol 2: Knot Security and Handling Characteristics Assessment

Purpose: To evaluate the practical surgical performance of suture materials, focusing on knot configuration and security.

Materials and Equipment:

- Universal testing machine with custom suture grips

- Microsurgical instruments (needle holders, forceps)

- Experienced surgeon evaluators (minimum n=3)

- Standardized evaluation scoring system

Procedure:

- Knot Configuration: Create standardized surgeon's knots and square knots according to established surgical protocols [36].

- Knot Security Testing: Mount knotted sutures in testing machine and apply tensile load (10 mm/min) until failure. Record failure mode (knot slippage vs. suture breakage).

- Handling Evaluation: Qualified surgeons perform standardized wound closure simulations, rating materials on:

- Pliability and memory

- Knot tie-down performance

- Tissue drag and passage

- Overall ease of use (5-point Likert scale)

- Statistical Analysis: Perform ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey testing (p<0.05) to identify significant differences between materials [5].

Protocol 3: In Vivo Biocompatibility and Functional Assessment

Purpose: To evaluate tissue response and functional performance of novel suture materials in a living system.

Materials and Equipment:

- Approved animal model (typically rat or rabbit)

- Histopathology equipment and stains (H&E, Masson's Trichrome)

- Immunohistochemistry capabilities (IL-10, TNF-α markers) [18]

- Sterile surgical facility and protocols

Procedure:

- Implantation: Insert test and control sutures subcutaneously or in target tissue according to approved ethical protocols.

- Time-point Analysis: Euthanize animals at predetermined intervals (1, 2, 4, 8, 12 weeks) for tissue collection.

- Histopathological Evaluation:

- Assess inflammatory cell infiltration (0-4 scale)

- Quantify foreign body giant cells and fibrosis

- Measure capsule thickness around suture material [39]

- Functional Assessment: Evaluate wound healing progression, scar formation, and tissue integration.

- Molecular Analysis: Perform cytokine profiling to characterize inflammatory response [18].

Advanced Suture Technologies and Research Applications

Emerging Suture Functionalization Strategies

Advanced suture technologies now incorporate multifunctional capabilities that extend beyond mechanical approximation:

- Antibacterial sutures: Coating or impregnation with antimicrobial agents (nanosilver, chlorhexidine, chitosan) to prevent surgical site infections [18] [40]. Recent approaches achieve 93.58% antibacterial effect against common pathogens like S. aureus and E. coli [18].

- Drug-eluting sutures: Controlled release systems for antibiotics, anti-inflammatories, or growth factors to modulate the healing microenvironment [18]. These systems can reduce inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, TNF-α) and promote angiogenesis [18].

- Smart responsive sutures: Materials designed to respond to environmental changes (pH, temperature) or provide electrical stimulation to accelerate wound healing [18] [8].

- Bio-inspired materials: Novel formulations using bacterial cellulose-chitosan composites that mimic natural structures, achieving knot-pull tensile strength of 23.3±0.6 N while promoting tissue regeneration [40].

Research Reagent Solutions for Suture Development

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Advanced Suture Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Polyglycolic Acid (PGA) | Synthetic polymer base | Primary material for absorbable sutures with rapid absorption [38] [9] |

| Polydioxanone (PDS) | Synthetic polymer base | Long-term absorbable sutures for slow-healing tissues [38] [9] |

| Chitosan | Natural polymer additive | Enhances antibacterial properties and flexibility [18] [40] |

| Nanoparticles (Ag, TiOâ‚‚) | Functional additives | Provide sustained antimicrobial activity [18] |

| Hyaluronic Acid | Coating material | Improves biocompatibility and antibacterial capabilities [36] |

| Chlorhexidine | Antimicrobial agent | Surgical site infection prevention in coated sutures [18] |

| Bacterial Cellulose | Base material | Bio-derived suture substrate with high purity and biocompatibility [40] |

The systematic matching of suture properties to clinical requirements represents a critical advancement in surgical materials science. By aligning quantitative metrics of tensile strength retention and absorption profiles with specific tissue healing timelines, researchers can design next-generation sutures that optimize patient outcomes. The experimental frameworks provided herein establish standardized methodologies for evaluating novel materials, while emerging technologies in antibacterial functionality, drug delivery, and smart responsiveness point toward future developments in active wound management. As the biodegradable suture market continues to expand—projected to reach $909.9 million by 2034—these principles will guide the innovation of specialized solutions tailored to specific surgical applications and patient populations [9].

Suture classification and sizing are fundamental to ensuring predictable performance, facilitating clear communication between researchers and clinicians, and maintaining quality control in the development of new degradable materials. The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) system provides a standardized framework for categorizing sutures based on diameter, a critical physical property directly linked to tensile strength [41] [42]. For research focused on degradable suture materials, a precise understanding of these standards is indispensable for accurately reporting material specifications, comparing experimental results, and designing pre-clinical studies that can be translated to clinical practice. This document outlines the key principles of suture classification and sizing, with a focus on applications within materials science research for implantable, degradable devices.

Suture Sizing Systems

USP System and Metric Measurements

The USP system classifies sutures using a numerical scale where diameter decreases as the number of zeros increases [41] [43]. This system provides a standardized nomenclature that is universally recognized. The corresponding metric sizes offer a direct measurement of the suture's diameter in millimeters, which is essential for precise engineering and material property calculations [42] [44].

Table 1: USP Suture Sizes and Metric Equivalents

| USP Designation | Synthetic Absorbable Diameter Range (mm) | Non-Absorbable Diameter Range (mm) | Typified Research and Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11-0 | - | 0.01 | Microsurgery, ophthalmology [43] |

| 10-0 | 0.02–0.029 | 0.02–0.029 | Microvascular, nerve repair [45] |

| 9-0 | 0.03–0.039 | 0.03–0.039 | Microsurgery [43] |

| 8-0 | 0.04–0.049 | 0.04–0.049 | Small vessel repair, grafting [43] |

| 7-0 | 0.05–0.069 | 0.05–0.069 | Vessel repair, fine facial suturing [43] |

| 6-0 | 0.07–0.099 | 0.07–0.099 | Facial skin closure, tendon repair [43] |

| 5-0 | 0.10–0.149 | 0.10–0.149 | Vessel repair, skin closure (limbs, face) [43] |

| 4-0 | 0.15–0.199 | 0.15–0.199 | Closure of fascia, muscle [43] |

| 3-0 | 0.20–0.249 | 0.20–0.249 | Closure of thick skin, fascia [43] |

| 2-0 | 0.30–0.339 | 0.30–0.339 | Fascia, drain stitches [43] |

| 0 | 0.35–0.399 | 0.35–0.399 | Fascia closure [43] |

| 1 | 0.40–0.499 | 0.40–0.499 | Large tendon repairs, thick fascial closures [43] |

| 2 | 0.50–0.599 | 0.50–0.599 | Large tendon repairs, orthopaedic surgery [43] |

| 3 | 0.60–0.699 | 0.60–0.699 | - |

| 4 | 0.60–0.699 | 0.60–0.699 | - |

Key Suture Classification Criteria

Beyond diameter, sutures are characterized by several other critical parameters that influence their in vivo performance and experimental outcomes.

- Absorbability: Absorbable sutures are degraded in tissue within 60 days, losing tensile strength as they are broken down, making them ideal for internal tissues and temporary support [41] [46] [44]. Non-absorbable sutures maintain their tensile strength for longer than 60 days and are used for long-term support or structures that heal slowly [41] [46].