A Comprehensive Protocol for Validating Spinal Implant Computational Models: From Theory to Clinical Translation

This article presents a detailed, step-by-step protocol for the rigorous validation of computational models used in spinal implant design and evaluation.

A Comprehensive Protocol for Validating Spinal Implant Computational Models: From Theory to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article presents a detailed, step-by-step protocol for the rigorous validation of computational models used in spinal implant design and evaluation. Aimed at researchers and biomedical engineers, the content explores the foundational principles of biomechanical modeling, outlines methodological best practices for finite element analysis (FEA) and multi-body dynamics, provides solutions for common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and establishes a robust framework for quantitative validation against experimental and clinical data. The protocol emphasizes standards like ASTM F2077 and ASME V&V 40 to ensure model credibility, ultimately bridging the gap between computational simulation and safe, effective implant development.

The Bedrock of Credibility: Core Principles and Standards for Spinal Implant Modeling

Defining Model Validation and Verification (V&V) in a Regulatory Context

In the context of regulatory submissions for spinal implants, computational model credibility is paramount. Validation and Verification (V&V) form the systematic process for assessing a model's accuracy and its predictive capability for the intended use. Regulatory bodies like the U.S. FDA and EU MDR require rigorous V&V as part of the computational modeling evidence for device safety and effectiveness.

Table 1: Key Regulatory Guidance Documents for Computational Model V&V

| Agency/Guideline | Document Title/Reference | Core V&V Principle Emphasized | Applicability to Spinal Implants |

|---|---|---|---|

| FDA | Reporting of Computational Modeling Studies in Medical Device Submissions | Credibility of computational models through V&V plans, evidence, and reports. | Directly applicable; recommends ASME V&V 40 framework. |

| ASME | V&V 40-2018: Assessing Credibility of Computational Modeling through Verification and Validation | Risk-informed credibility assessment framework (Credibility Factors). | Foundational framework referenced by regulators. |

| ISO | ISO/ASTM 52900:2021 Additive manufacturing — General principles | V&V for models used in design/ manufacturing (e.g., patient-specific implants). | Relevant for additively manufactured spinal devices. |

| EMA | Qualification of Novel Methodologies for Medicine Development | Defines "fit-for-purpose" model validation within a specific context of use. | Relevant for combination products (e.g., drug-eluting implants). |

Core Definitions in a Regulatory Context

- Verification: The process of ensuring that the computational model is implemented correctly and solves the underlying equations accurately. It answers: "Did we build the model right?"

- Validation: The process of determining the degree to which a model is an accurate representation of the real world from the perspective of the model's intended uses. It answers: "Did we build the right model?"

- Context of Use (COU): A definitive statement that fully and clearly describes the way the model will be used and the decisions it will inform. This is the critical first step defining the required level of credibility.

The ASME V&V 40 Risk-Informed Credibility Framework

The ASME V&V 40 framework is the industry standard for regulatory submissions. It ties the required level of V&V effort (Credibility) to the Risk of the Decision Informed by the Model.

Table 2: Relationship Between Model Risk and Required Credibility Evidence

| Model Risk Category (Per V&V 40) | Description | Example in Spinal Implant Research | Required Credibility Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | Model outcome directly impacts device safety/ efficacy decision; low prior knowledge. | Predicting novel implant's fatigue life in worst-case anatomical loading. | Very High. Extensive, multi-faceted V&V required. |

| Medium | Model informs design or supplements physical test data; some prior knowledge exists. | Comparing relative motion (stability) between two established implant designs. | Medium to High. Targeted V&V on key outputs. |

| Low | Model used for exploratory research or screening; not used for direct claims. | Preliminary scoping study of stress distribution in a vertebral body. | Low. Basic verification and rationale suffice. |

Credibility is built by accumulating evidence across six Credibility Factors: 1. Code Verification, 2. Solution Verification, 3. Conceptual Model Assessment, 4. Input Uncertainty Quantification, 5. Model Validation, 6. Results Uncertainty Quantification.

Title: The ASME V&V 40 Risk-Informed Credibility Process

Detailed V&V Application Notes & Protocols for Spinal Implant Models

Application Note 1: Verification Protocol for a Spinal Fusion Finite Element Model

- Context of Use: Predict segmental range of motion (ROM) and bone-implant interface stresses under physiological loading.

- Verification Activities:

- Code Verification: Use commercial FEA software (e.g., Abaqus, ANSYS) with prior qualification evidence. Document solver version and patch level.

- Solution Verification (Numerical Accuracy):

- Perform mesh convergence study on key outputs (ROM at treated level, peak von Mises stress in implant).

- Protocol: Refine global mesh size sequentially by factor of √2. Model is considered converged when change in key outputs is <5%.

Table 3: Example Mesh Convergence Study Data (L4-L5 Model)

| Mesh Size (mm) | No. of Elements | L4-L5 Flexion ROM (degrees) | % Change from Previous | Peak Implant Stress (MPa) | % Change from Previous |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.0 | 45,200 | 3.85 | - | 142.5 | - |

| 1.4 | 92,500 | 4.12 | 7.0% | 155.8 | 9.3% |

| 1.0 | 181,300 | 4.28 | 3.9% | 162.1 | 4.0% |

| 0.7 | 350,000 | 4.31 | 0.7% | 163.5 | 0.9% |

| 0.5 | 680,000 | 4.32 | 0.2% | 164.0 | 0.3% |

Application Note 2: Validation Protocol Against Bench Test Data

- Context of Use: Predict fatigue performance of a pedicle screw construct.

- Validation Experiment: Correlate model-predicted strain/stress with physical strain gauge measurements on a polyurethane foam block (ASTM F1839) or cadaveric vertebra.

- Detailed Protocol:

- Bench Test Setup: Perform axial cyclic loading (e.g., 100-1000N, 5Hz) on a screw implanted in validated foam block. Attatch strain gauges at screw neck and shaft.

- Computational Model: Replicate exact test geometry, boundary conditions, and material properties (foam density matched to test certificate).

- Comparison Metric: Compare strain amplitude and pattern at identical gauge locations.

- Acceptance Criterion: Predicted vs. experimental strain hysteresis loops shall have a correlation coefficient (R²) > 0.85, and mean strain error < 15%.

Title: Model Validation Workflow Against Bench Test Data

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for V&V

Table 4: Essential Materials & Tools for Spinal Implant Model V&V

| Item/Category | Example Product/Specification | Function in V&V Process |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Test Substrate | Sawbones Polyurethane Foam Blocks (ASTM F1839, densities: 0.16g/cc, 0.32g/cc) | Provides consistent, repeatable mechanical properties for validation bench testing against computational models. |

| Cadaveric Tissue | Fresh-frozen human spinal segments (L1-L5) with documented bone mineral density. | Gold-standard biological substrate for highest-fidelity validation of models predicting bone-screw interaction or implant kinematics. |

| Digital Reference Data | Public corpus of spine CT/MRI datasets (e.g., Visible Human Project, SpineWeb). | Serves as anatomical input for developing and testing image segmentation and model generation pipelines (Conceptual Model Assessment). |

| Calibrated Sensors | Micro-strain gauges (e.g., FLA-2-11, Tokyo Sokki Kenkyujo); 6-DOF load cells. | Provides ground-truth mechanical data (strain, force, moment) from physical tests for quantitative model validation. |

| Software Verification Suite | NAFEMS FEA Benchmark Problems (e.g., LE10, LE11). | Standardized problems with known analytical solutions to verify correct implementation of element formulations and material models. |

| Uncertainty Quantification Tool | Dakota (SNL), or proprietary Monte Carlo modules in FEA packages. | Propagates input uncertainties (e.g., bone material properties, loading direction) to quantify uncertainty in model outputs. |

This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for biomechanical testing of the spine, framed within the context of validating computational models for spinal implants. The validation of finite element (FE) and multi-body dynamics models requires rigorous experimental benchmarking against controlled in vitro tests that quantify the spine's response to fundamental loads and motions, up to and including structural failure. These protocols are essential for researchers and engineers developing and certifying new spinal implant systems.

Quantification of Spinal Loads and Motions

Understanding the in vivo loading environment is critical for designing physiologically relevant computational models and experimental validation tests.

Table 1: RepresentativeIn VivoLoads on the Lumbar Spine

| Activity / Condition | Approximate Load (L4-L5) | Measurement Method | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standing at ease | 500 N | Telemeterized Implant | Rohlmann et al., 2013 |

| Walking | 650 - 850 N | Telemeterized Implant | Fagan et al., 2002 |

| Flexion (20°) | 1100 - 1200 N | Telemeterized Implant | Rohlmann et al., 2001 |

| Lifting 20kg (bent knees) | 1900 - 2400 N | Intra-Discal Pressure + Modeling | Wilke et al., 1999 |

| Sitting unsupported | 700 - 900 N | Intra-Discal Pressure | Sato et al., 1999 |

| Coughing / Sneezing | ~1000 N | Telemeterized Implant | Rohlmann et al., 2009 |

Protocol 1.1:In VitroRange of Motion (ROM) Testing

Purpose: To quantify the flexibility (angular motion per applied moment) of a spinal segment (FSU) in primary anatomical planes. This data is the primary benchmark for validating the kinematic response of computational models.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

- Fresh-Frozen Human Spinal Segments (FSUs): Cadaveric functional spinal units (e.g., L2-L3). Primary biological substrate.

- Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA): For potting vertebral ends to ensure rigid fixation in testing fixtures.

- 6-Degree-of-Freedom Spinal Testing Machine: Electromechanical or servo-hydraulic system capable of applying pure moments.

- Optical Motion Capture System (IR cameras & markers): For high-fidelity, non-contact measurement of 3D vertebral kinematics.

- Environmental Chamber/Humidifier: To maintain tissue hydration with 0.9% saline spray during testing.

- Calibrated Moment-Angle Data Acquisition Software: Custom or commercial (e.g., LabVIEW) for real-time data collection.

Methodology:

- Specimen Preparation: Thaw FSU at 4°C. Carefully dissect paravertebral musculature while preserving ligaments, joints, and discs. Pot cranial and caudal vertebrae in PMMA blocks, ensuring the disc is oriented horizontally.

- Fixture & Instrumentation: Mount potted specimen in testing machine. Attach reflective marker triads rigidly to each vertebral body (not the potting blocks).

- Preconditioning: Apply 3-5 cycles of a low-magnitude pure moment (e.g., ±3 Nm) in flexion-extension, lateral bending, and axial rotation to establish a repeatable neutral zone.

- Load-Controlled Flexibility Test: Apply a pure moment in one primary plane (e.g., flexion-extension) at a slow rate (e.g., 1°/s or 0.1 Nm/s) to a target maximum (typically ±7.5 Nm or ±10 Nm). Hold at peak moment for a 10-second creep period. Record applied moment and the resulting angular displacement from the motion capture system throughout the cycle.

- Data Analysis: Plot moment vs. angle (hysteresis curve). Calculate neutral zone (NZ), range of motion (ROM), and stiffness (slope of the linear region) for the loading phase. Repeat steps 4-5 for lateral bending and axial rotation.

- Model Validation Benchmark: The experimental ROM at ±7.5 Nm serves as the direct validation target for the computational model under identical boundary conditions and loading.

In Vitro Flexibility Testing Workflow

Failure Modes and Injury Mechanisms

Validating a model's prediction of failure (e.g., vertebral fracture, ligament rupture) requires experimental protocols that induce and quantify damage.

Table 2: Common Spinal Failure Modes Under Specific Loading

| Failure Mode | Typical Loading Condition | Associated Injury / Pathology | Critical Biomechanical Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vertebral Body Fracture | Compression / Flexion | Osteoporotic Fracture, Burst Fracture | Ultimate Load (kN), Yield Stress (MPa) |

| Annular Tear / Disc Herniation | Complex Flexion-Compression-Torsion | Disc Prolapse, Radiculopathy | Intradiscal Pressure, Annulus Strain |

| Ligamentous Failure (e.g., PLL, SSL) | Hyperflexion / Hyperextension | Whiplash, Distraction Injury | Ligament Strain at Failure (%) |

| Facet Joint Fracture / Subluxation | Compression-Shear / Torsion | Spondylolisthesis, Facet Arthritis | Joint Contact Force (N) |

| Endplate Fracture | Rapid Compression | Schmorl's Nodes, Disc Degeneration | Endplate Strength (MPa) |

Protocol 2.1: Compressive Failure Testing of Vertebral Bodies

Purpose: To determine the ultimate compressive strength and failure mechanism of a vertebral body. This data validates the failure criteria of material models in FE analyses.

Materials:

- Isolated Vertebral Body: Prepared from a spinal segment.

- Bi-axial Materials Testing System: High-capacity load frame with a rigid, flat platen.

- Saline Spray System: For hydration.

- Digital Image Correlation (DIC) System: Two-camera setup with speckle pattern for full-field strain measurement.

- Acoustic Emission Sensors (Optional): To detect microfracture events.

Methodology:

- Specimen Preparation: Isolate the vertebral body by removing posterior elements and adjacent discs. Parallelize the superior and inferior endplates using a milling machine. Apply a fine speckle pattern on one lateral surface for DIC.

- Mounting: Place the vertebra between two rigid, flat platens. Ensure centric axial alignment.

- Testing: Apply a displacement-controlled axial compression at a slow rate (e.g., 1 mm/min) until a clear drop in load (>20% of peak) is observed, indicating structural failure. Continuously record load, displacement, DIC images, and acoustic emission.

- Post-Test Analysis: Calculate ultimate compressive strength (peak load / cross-sectional area). Use DIC to map strain localization leading to fracture. Correlate acoustic events with load steps. Visually classify fracture type (wedge, burst, etc.).

- Model Validation: The experimental load-displacement curve to failure and the observed fracture pattern are compared to the FE model prediction under identical conditions.

Pathways to Vertebral Body Failure Under Compression

Protocol for Implant-Spine Construct Validation

This integrated protocol combines principles from Sections 1 & 2 to validate a model of an instrumented spine.

Protocol 3.1: Hybrid Experimental-Computational Validation of a Spinal Fixation Construct

Purpose: To generate a comprehensive dataset for validating a computational model of a lumbar segment stabilized with pedicle screw-based instrumentation.

Materials:

- Instrumented Lumbar Specimen (e.g., L1-L3): With a destabilized L2-L3 segment (e.g., dissected disc, ligaments) and posterior fixation at L2-L3.

- Spinal Testing Machine & Motion Capture: As in Protocol 1.1.

- Strain Gauges: Miniature gauges applied to implant rods.

- Pressure-Sensitive Film or Tactile Sensor: For facet joint contact pressure measurement (optional).

Methodology:

- Native State Testing: Perform flexibility test (Protocol 1.1) on the intact L1-L3 specimen to establish baseline ROM.

- Destabilization: Create a standard injury model (e.g., complete discectomy, partial facetectomy) at L2-L3.

- Instrumentation: Implant the pedicle screw-rod system at L2-L3 according to surgical guidelines. Apply strain gauges to the rods.

- Instrumented State Testing: Repeat the flexibility test on the instrumented construct. Record simultaneously: a) segmental ROM (L2-L3), b) rod strain, c) adjacent segment ROM (L1-L2).

- Validation Data Generation: Create a table comparing experimental results (Intact vs. Instrumented) for ROM and rod strain. This forms the multi-modal validation dataset.

- Computational Model Calibration/Validation: The FE model of the intact spine is first calibrated to match the native state ROM. The model of the instrumented construct is then validated against the instrumented state data for ROM, rod strain (stress), and load-sharing characteristics.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Spinal Biomechanics

| Item / Solution | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration for Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Fresh-Frozen Cadaveric Spine | Gold-standard biological substrate for in vitro testing. | Segment (age, BMD), handling (freeze-thaw cycles) critically affect mechanical properties and must be documented for model input. |

| Polyurethane Foam Spines | Repeatable, isotropic synthetic models for feasibility studies. | Material properties are simplified and non-physiological; useful for initial implant fit/range checks, not final validation. |

| 6-DOF Spinal Simulator | Applies pure moments or follower loads to simulate in vivo motion. | Machine compliance and control algorithm (load vs. displacement) must be understood and replicated in the model's boundary conditions. |

| Optical Motion Capture (IR) | Provides high-accuracy 3D kinematics without contact artifacts. | Marker placement relative to vertebral bone (vs. potting block) is crucial; must be digitally replicated in the model. |

| Digital Image Correlation (DIC) | Measures full-field surface strains on bone, implants, or disc. | Provides rich spatial data for validating strain fields predicted by the FE model, moving beyond single-point comparisons. |

| Telemeterized Implant Data | In vivo force measurements from instrumented patients. | The ultimate validation target for load-prediction models, though rare and patient-specific. |

This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for three core computational techniques—Finite Element Analysis (FEA), Multi-body Dynamics (MBD), and Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD). The content is framed within the overarching research thesis: "Protocol for Validating Spinal Implant Computational Models." The objective is to establish rigorous, standardized methodologies for generating and validating computational models that predict the biomechanical performance, durability, and interaction of spinal implants with human physiology. These validated models are critical for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to accelerate the design and regulatory evaluation of novel spinal implants and biologics.

Finite Element Analysis (FEA) for Spinal Implants

Application Notes

FEA is a numerical method for simulating the mechanical response of a structure to loads. In spinal implant research, it is used to predict stress distributions in implants and adjacent bone, assess risk of subsidence or fracture, and evaluate stability under physiological loading.

Key Applications:

- Stress-Shielding Analysis: Quantifying bone resorption due to altered load transfer.

- Fatigue Life Prediction: Estimating implant durability under cyclic loading.

- Patient-Specific Modeling: Using CT data to create subject-specific models for pre-surgical planning.

Protocol: FEA of a Lumbar Cage for Subsidence Risk

Objective: To validate an FEA model predicting the risk of vertebral body subsidence under static compression.

Materials & Software:

- µCT scan data of lumbar vertebral body (L3).

- CAD model of a PEEK interbody cage.

- FEA Software (e.g., ANSYS, Abaqus).

- Material property assignment tables from literature.

Methodology:

- Geometry Reconstruction:

- Segment the L3 vertebral body from µCT data using thresholding.

- Generate a 3D surface model, preserving cortical shell and trabecular architecture.

- Import and position the cage CAD model within the intervertebral space.

- Meshing:

- Mesh the cortical bone with 0.5 mm tetrahedral elements.

- Mesh the trabecular bone with 1.0 mm tetrahedral elements.

- Mesh the implant with 0.3 mm hexahedral elements.

- Perform a mesh convergence study.

- Material Properties & Boundary Conditions:

- Assign linear elastic, isotropic properties (See Table 1).

- Define a frictionless contact interface between cage and bone.

- Fix the inferior surface of the vertebral body in all degrees of freedom.

- Apply a 2000 N compressive load distributed on the superior surface.

- Solution & Validation:

- Run a static structural analysis.

- Validate by comparing predicted strain in the vertebral body against in vitro digital image correlation (DIC) data from a corresponding physical test.

- Calibrate the model by adjusting trabecular bone modulus if error >15%.

Table 1: Typical Material Properties for Lumbar FEA

| Material | Young's Modulus (MPa) | Poisson's Ratio | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical Bone | 12,000 | 0.30 | Literature (Rho et al., 1993) |

| Trabecular Bone | 100 - 900 (Region-dependent) | 0.20 | Patient CT-derived (Bone Density) |

| PEEK Implant | 3,500 | 0.36 | Manufacturer Datasheet |

| Titanium Alloy (Ti-6Al-4V) | 110,000 | 0.33 | ASTM F136 |

Multi-body Dynamics (MBD) for Spinal Segment Kinematics

Application Notes

MBD simulates the motion of interconnected rigid or flexible bodies under force. It is used to analyze the kinematic and kinetic behavior of the spine as a system, evaluating range of motion, facet joint forces, and ligament tensions before and after implantation.

Key Applications:

- Implant Kinematic Performance: Assessing dynamic stability and constraint provided by pedicle screw systems or artificial discs.

- Wear Simulation: Predicting bearing surface wear in mobile-core implants.

- Whole-Spine Dynamics: Studying compensation mechanisms in adjacent segments.

Protocol: MBD Simulation of a Spinal Motion Segment with a Dynamic Stabilization Device

Objective: To validate an MBD model predicting L4-L5 range of motion (ROM) and facet contact forces after implantation of a posterior dynamic stabilization device.

Materials & Software:

- Geometrically accurate MBD model of L4-L5 vertebrae (from public database or reconstructed).

- CAD of the dynamic stabilization device (rods, screws, spacers).

- MBD Software (e.g., ADAMS LifeMOD, AnyBody).

- Kinematic input data from in vitro flexibility tests.

Methodology:

- Model Assembly:

- Define L4 and L5 as rigid bodies. Incorporate intervertebral disc as a 6-DOF nonlinear bushing element.

- Model major ligaments (ALL, PLL, LF, CL, ISL) as nonlinear tension-only spring elements.

- Model facet articulations as 3D contact elements.

- Assemble the implant model, defining joints between screws/vertebrae and compliant elements for the dynamic rod.

- Kinematic Driving & Loading:

- Apply pure moments (7.5 Nm) in flexion-extension, lateral bending, and axial rotation to the superior vertebra (L4) using a kinematic driver.

- Constrain the inferior vertebra (L5) in space.

- Apply a 500 N follower preload to simulate musculature.

- Simulation & Validation:

- Run dynamic simulation for each loading mode.

- Output L4-L5 angular ROM and L4-L5 facet joint contact forces.

- Validate by comparing simulation outputs to data from a matched in vitro experiment using a spinal testing machine and load-sensing facets. Correlation should be R² > 0.85.

Table 2: Key Ligament Properties for MBD (Wiltse et al.)

| Ligament | Stiffness (N/mm) | Pre-strain (%) | Cross-Sectional Area (mm²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior Longitudinal (ALL) | 30.0 | 0.0 | 40.2 |

| Posterior Longitudinal (PLL) | 50.0 | 0.0 | 13.1 |

| Ligamentum Flavum (LF) | 40.0 | 15.0 | 62.1 |

| Capsular Ligament (CL) | 35.0 | 0.0 | 60.1 |

| Interspinous (ISL) | 15.0 | 0.0 | 40.0 |

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) for Biologics Transport

Application Notes

CFD analyzes fluid flow, heat transfer, and associated phenomena. In spinal research, it models the flow of blood, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), or the diffusion of therapeutic agents (e.g., drugs, osteoinductive factors) within the spinal canal or implant-bone interface.

Key Applications:

- Drug Elution from Implants: Optimizing porous coating designs for controlled release of osteogenic drugs.

- CSF Flow Dynamics: Investigating shear stress on the spinal cord or drug dispersion in intrathecal delivery.

- Bone Ingrowth Simulation: Modeling interstitial fluid flow and nutrient transport in porous spinal implants.

Protocol: CFD of Osteogenic Drug Elution from a Porous Titanium Cage

Objective: To validate a CFD model predicting the concentration profile of a bone morphogenetic protein (BMP-2) analog eluting from a porous cage into the adjacent vertebral body.

Materials & Software:

- 3D CAD model of the porous cage and simplified bone region.

- CFD Software (e.g., STAR-CCM+, Fluent).

- Physicochemical properties of the carrier (e.g., collagen sponge) and drug.

Methodology:

- Geometry & Meshing:

- Create a fluid domain representing the porous carrier within the implant and the interconnected pore space of the adjacent trabecular bone.

- Generate a polyhedral volume mesh with prism layers at walls. Ensure mesh quality (skewness < 0.8).

- Physics & Boundary Conditions:

- Model the fluid (interstitial fluid) as incompressible and Newtonian.

- Model the porous carrier region using Darcy's Law with defined permeability.

- Define the drug as a dilute species. Set initial concentration in the carrier to 1.5 mg/mL.

- Set bone boundaries as no-slip walls. Set outer boundaries as zero-concentration outlets.

- Apply species diffusion coefficient (1e-10 m²/s) and carrier porosity (0.85).

- Solution & Validation:

- Run a transient simulation for 14 days.

- Output concentration contours and temporal release profile.

- Validate by comparing the simulated release curve (cumulative release vs. time) against data from an in vitro elution test (HPLC measurement) in a simulated body fluid bath. Normalized RMS error should be < 20%.

Table 3: Key Parameters for Drug Elution CFD

| Parameter | Value | Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluid Density (ρ) | 1000 | kg/m³ | Assumed water-like |

| Fluid Viscosity (μ) | 0.001 | Pa·s | Assumed water-like |

| Carrier Permeability (κ) | 1.0e-12 | m² | From literature (collagen sponge) |

| Drug Diffusion Coefficient (D) | 1.0e-10 | m²/s | For BMP-2 in aqueous solution |

| Initial Drug Concentration | 1.5 | mg/mL | Typical clinical loading |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function in Computational Model Validation |

|---|---|

| Polyurethane Foam Sawbones | Represents standardized bone material for in vitro bench tests. Used to validate FEA models of implant-bone interface mechanics under controlled, repeatable conditions. |

| Fresh-Frozen Human Cadaveric Spine Segments | Provides biologically accurate anatomy and material properties. The gold standard for in vitro validation of MBD and FEA models regarding kinematics, kinetics, and failure modes. |

| Digital Image Correlation (DIC) System | Non-contact optical method to measure full-field strain on bone or implant surfaces during mechanical testing. Critical for validating FEA-predicted strain fields. |

| Six-Degree-of-Freedom Spinal Testing Machine | Applies pure moments and follower loads to spine specimens. Generates kinematic and load data required to drive and validate MBD simulations. |

| Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) | Ion concentration similar to human blood plasma. Used in in vitro elution or corrosion studies to provide a biologically relevant fluid environment for CFD model validation. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Essential for solving high-fidelity, patient-specific FEA and CFD models with millions of elements and complex nonlinearities in a reasonable timeframe. |

| Bone Cement (PMMA) | Used to pot specimens for mechanical testing and to simulate osteolytic defects in validation models for implant stability. |

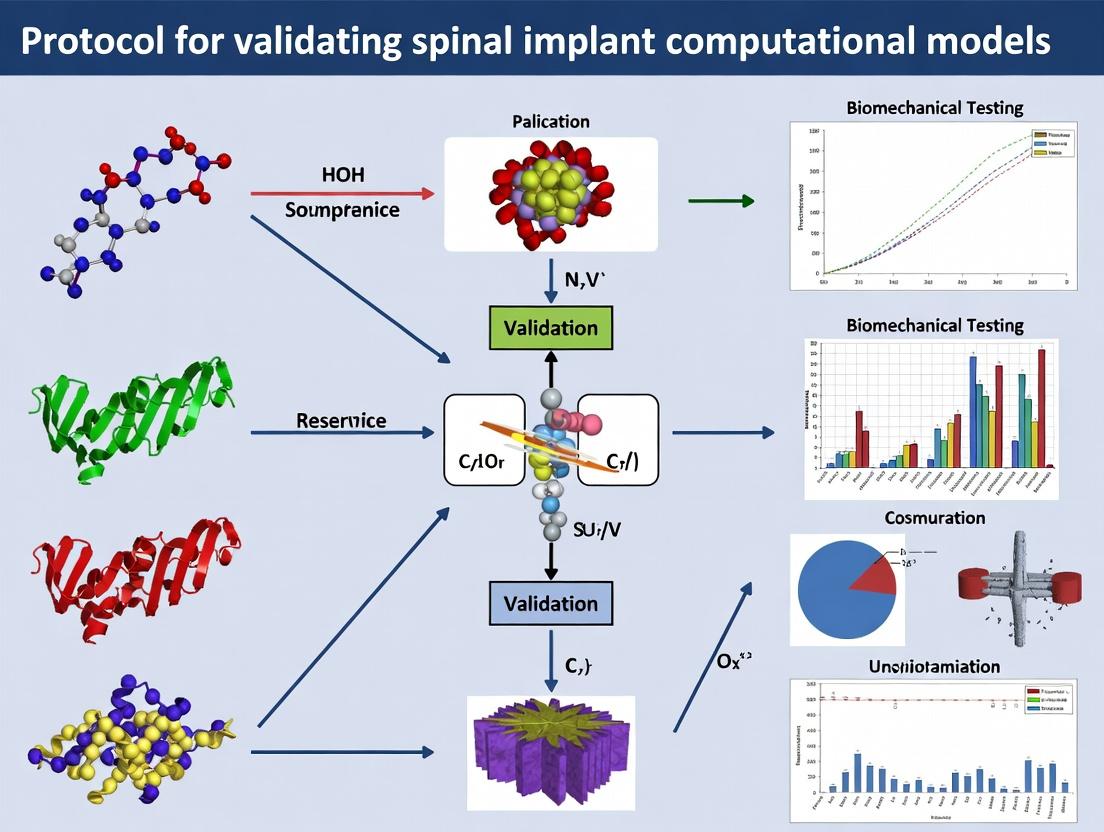

Visualization: Computational Validation Protocol Workflow

Diagram 1: Core Validation Workflow for Spinal Implant Models

Diagram 2: Computational Techniques Map for Spinal Implant Research

Within the research framework for a Protocol for Validating Spinal Implant Computational Models, understanding the regulatory and standardization landscape is paramount. This document provides Application Notes and detailed experimental Protocols based on three cornerstone guidance documents: ASTM, ISO, and ASME V&V 40. These standards provide the structured methodology required to establish credibility in computational model predictions used for evaluating spinal implant safety and performance.

The table below summarizes the key focus, scope, and quantitative requirements of each standard relevant to computational model validation.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Key Standards for Computational Model Validation

| Standard / Guideline | Primary Focus & Scope | Key Quantitative Metrics / Tiers | Direct Application to Spinal Implant Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASME V&V 40-2018Assessing Credibility of Computational Modeling | Risk-informed credibility assessment framework. Defines Model Risk and Decision Risk. | Credibility Factors:1. Verification (Code, Calculation)2. Validation (Experimental)3. Application Inputs4. Results UncertaintyCredibility Scale: Low / Medium / High based on Decision Consequence. | Core framework for defining the required level of validation evidence based on the clinical risk of the spinal implant simulation (e.g., range of motion vs. fatigue fracture). |

| ASTM F3163-21Guide for Verification of Computational Solid Mechanics Models | Specific guidance for verification of finite element analysis (FEA) models. | Verification Activities:1. Code Verification (e.g., order of accuracy, P ≥ 2.0)2. Calculation Verification (Grid Convergence Index, GCI < 5-10% recommended). | Essential for ensuring the spinal implant FEA model is solving equations correctly and numerical errors are quantified. |

| ISO 19208:2017Framework for Verification, Validation of Computational Solid Mechanics Models | High-level framework aligning V&V activities with intended use. | Defines stages: Planning, Verification, Validation, Uncertainty Quantification. Recommends reporting of validation metrics (e.g., correlation metrics). | Provides the overarching process flow for the validation protocol, ensuring traceability from intended use to validation conclusion. |

Application Notes for Spinal Implant Model Validation

Note 1: Risk-Informed Credibility Plan (ASME V&V 40)

The Decision Consequence of the model dictates the required Credibility. For a spinal implant model predicting adjacent segment disc stress:

- High Decision Consequence: Model informs a pivotal preclinical safety test (e.g., implant fracture risk). Requires High Credibility – extensive validation under multiple loading conditions with stringent accuracy metrics.

- Low Decision Consequence: Model used for comparative design screening (e.g., comparing two screw thread designs). May require only Medium Credibility – validation against a single benchmark experiment.

Note 2: Hierarchical Validation Strategy

Leverage a multi-fidelity approach to build model credibility efficiently:

- Sub-model Validation: Validate material models (e.g., titanium elastoplasticity, bone plasticity) against simple coupon tests.

- Component Validation: Validate implant sub-assembly performance (e.g., screw pullout from a synthetic bone block).

- System Validation: Validate full spinal segment (e.g., L3-L5) response under flexion/extension against cadaveric or synthetic spine test data.

Note 3: Validation Metrics and Acceptance Criteria

Define quantitative metrics a priori based on the standard's guidance and clinical relevance.

- Correlation: Use Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) or Correlation Coefficient (R²).

- Difference Metrics: Use Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) normalized to a relevant physical quantity (e.g., range of motion in degrees).

- Example Acceptance Criterion: For a range of motion prediction in a lumbar model, MAPE < 15% may be deemed acceptable for a medium-consequence decision.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validation of a Lumbar Spinal Fusion Construct FEA Model

Title: Experimental Validation of an L4-L5 Instrumented FEA Model Against Cadaveric Biomechanical Testing.

Objective: To validate the kinematic (range of motion) and kinetic (facet joint forces) predictions of a lumbar fusion model per ASME V&V 40 and ISO 19208.

Materials & Reagents: See Scientist's Toolkit below.

Workflow Diagram:

Diagram Title: Spinal Implant Model V&V Workflow

Methodology:

- Computational Model Setup:

- Develop a detailed L4-L5 FEA model including vertebrae (cortical/cancellous bone), intervertebral disc (annulus ground substance & fibers), ligaments (7 major ligaments), and the implant (pedicle screws & rods).

- Assign material properties from peer-reviewed literature.

- Verification (Per ASTM F3163): Perform mesh convergence study. Calculate the Grid Convergence Index (GCI) for maximum von Mises stress in the implant and L4 inferior endplate displacement. Refine mesh until GCI < 5%.

Validation Experiment Setup:

- Obtain N=6 fresh-frozen human L4-L5 specimens.

- Pot specimens in polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) fixtures.

- Mount on a servo-hydraulic test system equipped with a 6-axis load cell.

- Apply pure moments of 7.5 Nm in flexion, extension, lateral bending, and axial rotation following a standard loading protocol (e.g., ISO 12189).

- Measure segmental range of motion (ROM) using an optical motion capture system.

- Measure facet joint contact forces using thin-film pressure sensors inserted in the facet joint capsule.

Simulation & Comparison:

- Run the FEA simulation replicating the exact experimental loading and boundary conditions.

- Extract the same output quantities: ROM for each loading mode and facet joint forces.

- Calculate validation metrics between experimental (E) and simulated (S) data for each specimen:

ROM_MAPE = (1/N) * Σ(|S_i - E_i| / E_i) * 100%(for each motion direction).Force_R²for facet force vs. applied moment curve.

- Compare metrics to pre-defined acceptance criteria (e.g., ROM_MAPE < 20%; R² > 0.85).

Credibility Assessment:

- Following ASME V&V 40, given the model's use for a medium-consequence decision (supporting a 510(k) submission), the achieved validation evidence, combined with completed verification and uncertainty quantification, supports a Medium to High Credibility rating for predicting ROM.

Protocol 2: Verification of a Standalone Cervical Disc Implant Fatigue Model

Title: Code and Calculation Verification for an FEA Model of a Cervical Disc Fatigue Life Prediction.

Objective: To perform rigorous verification of the numerical solution for a dynamic fatigue analysis of a cervical disc implant as per ASTM F3163.

Workflow Diagram:

Diagram Title: FEA Model Verification Process

Methodology:

- Code Verification (Software):

- Use the Method of Manufactured Solutions (MMS). Apply a simple, known displacement field to a coarse mesh of a single implant component (e.g., the core).

- Calculate the corresponding body forces and boundary conditions required to satisfy the momentum equations.

- Input these forces/BCs into the FEA solver and run the analysis.

- Compare the solver's displacement output to the manufactured solution. The observed order of accuracy should approach the theoretical order of the elements used (e.g., ≥ 2.0 for quadratic elements).

- Calculation Verification (Specific Model):

- Develop three mesh densities for the full cervical disc implant assembly: Coarse, Medium, and Fine (e.g., increasing element count by a factor of ~1.5-2 each time).

- Run a static load step simulating peak load in the fatigue cycle.

- Monitor a key output, such as the maximum principal stress in the ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) core.

- Perform a Richardson Extrapolation on the results from the three meshes to estimate the asymptotic numerical value.

- Calculate the Grid Convergence Index (GCI) for the Fine mesh solution.

GCI_fine = (F_s * |ε|) / (r^p - 1), where ε is the relative error between fine and medium solutions, r is the refinement ratio, p is the observed order of accuracy, and F_s is a safety factor (1.25 for 3+ grids). - Acceptance: GCI < 10% for the region of interest (stress concentration area). Document this as the numerical uncertainty.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Spinal Implant Model Validation

| Item / Solution | Function in Validation Context | Example Product / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Bone Blocks | Provides standardized, repeatable medium for component validation (e.g., screw pullout, rod bending). Mimics cancellous bone density. | Sawbones (Pacific Research Labs) foam blocks of specified density (e.g., 15 pcf or 30 pcf). |

| Fresh-Frozen Cadaveric Spines | The gold-standard biological substrate for system-level validation. Provides realistic anatomy and material properties. | Sourced from accredited tissue banks. Stored at -20°C, thawed in saline at 4°C prior to testing. |

| Biocompatible Potting Material | Secures bone specimens into testing fixtures for biomechanical testing. Provides rigid fixation without damaging the tissue. | Poly-methyl methacrylate (PMMA) dental acrylic or low-melt alloy. |

| 6-Axis Load Cell | Precisely measures applied forces and moments during biomechanical testing, providing input validation for simulations. | ATI Mini-45 or similar. Calibrated for Fx, Fy, Fz, Tx, Ty, Tz. |

| Optical Motion Capture System | Accurately measures 3D kinematic output (range of motion, center of rotation) for comparison with FEA predictions. | Vicon or OptiTrack systems with retroreflective markers. |

| Finite Element Analysis Software | Platform for developing and solving computational solid mechanics models. Must have robust solvers and element libraries. | Abaqus (Dassault Systèmes), Ansys Mechanical, or FEBio. |

| Thin-Film Pressure Sensor | Measures contact force/pressure in joints (e.g., facet joints) or between implant components for kinetic validation. | Tekscan K-Scan or I-Scan sensors, calibrated within appropriate pressure range. |

The Role of Validation in the Implant Design Lifecycle and Regulatory Submissions

1. Introduction Within the thesis framework of Protocol for validating spinal implant computational models research, validation is the critical process determining if a computational model accurately represents the physical reality of implant performance. It is not a single event but an iterative activity integrated throughout the design lifecycle, culminating in evidence for regulatory submissions. This document outlines application notes and detailed protocols to formalize this process.

2. Application Notes: Integrating Validation Milestones Validation activities must be synchronized with key design and regulatory stages, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Validation Integration in the Implant Lifecycle

| Lifecycle Phase | Primary Validation Objective | Key Inputs | Output for Regulatory File |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concept & Feasibility | Assess model conceptual accuracy. | Literature data, material properties. | Report on model rationale and scope. |

| Design & Development | Correlate model predictions with benchtop tests (e.g., static, fatigue). | CAD geometry, ASTM test protocols, prototype test data. | Correlation plots and statistical analysis (e.g., R², error margins). |

| Verification & Validation (V&V) | Execute formal model V&V per ASME V&V 40. | Final test data from standardized mechanical tests. | Comprehensive V&V report documenting credibility. |

| Regulatory Submission | Demonstrate model credibility for specific Context of Use (COU). | All prior reports, risk analysis, COU statement. | Integrated summary for FDA/EMA, justifying model use in lieu of certain tests. |

3. Experimental Protocols for Validation Benchmarking The following protocol details a core experiment for validating a finite element analysis (FEA) model of a lumbar spinal implant under static compression.

Protocol 3.1: Physical Benchmark Test for Computational Model Validation

- Objective: To generate empirical data for validating a computational model predicting implant subsidence and strain under compressive load.

- Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" below.

- Methods:

- Specimen Preparation: Use polyurethane foam blocks (Grade 20, 0.32 g/cm³) as standardized surrogate bone material. Machine blocks to dimensions per ASTM F1839.

- Implant Placement: Assemble the titanium alloy (Ti-6Al-4V) implant per surgical technique guide. Insert it into the prepared foam block using a fixture ensuring consistent alignment.

- Instrumentation: Affix a minimum of three uniaxial strain gauges (e.g., 350-ohm) to critical locations on the implant. Connect to a calibrated data acquisition system.

- Mechanical Testing: Mount the construct in a servo-hydraulic test frame. Apply a pre-load of 50N. Then, apply a quasi-static compressive load at a rate of 25 N/s to a maximum of 2000N, holding for 30 seconds. Record load, displacement, and strain data at 100 Hz.

- Data Collection: Perform five (n=5) replicate tests. Record (i) Load vs. Displacement (subsidence) and (ii) Load vs. Microstrain for each gauge location.

- Deliverables: A dataset of mean displacement and strain values with standard deviations at key load intervals (e.g., 500N, 1000N, 2000N) for direct comparison to computational predictions.

4. Visualization of the Validation Workflow

Diagram 1: Validation workflow for spinal implant models.

Table 2: Sample Validation Metric Table (Compression at 2000N)

| Data Source | Subsidence (mm) | Strain at Location A (με) | Strain at Location B (με) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Mean (n=5) | 1.52 ± 0.18 | 1250 ± 95 | 980 ± 110 |

| Computational Prediction | 1.48 | 1190 | 1015 |

| Absolute Error | 0.04 | 60 | 35 |

| Error (%) | 2.6% | 4.8% | 3.6% |

5. The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions Table 3: Essential Materials for Validation Testing

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Polyurethane Foam Blocks (Grade 10/20) | Standardized surrogate for cancellous bone with consistent properties, reducing biological variability in benchtop tests. |

| Ti-6Al-4V ELI Alloy Rods/Implants | Medical-grade titanium alloy representing final implant material for testing; essential for accurate strain measurement. |

| Uniaxial Strain Gauges (350-ohm) | Sensors bonded to implant surface to measure local surface strain, providing direct comparison to FEA node results. |

| Servo-hydraulic Test Frame | Provides precise, controlled application of mechanical loads (compression, shear, fatigue) per ASTM standards. |

| Optical 3D Digital Image Correlation (DIC) System | Non-contact method to measure full-field displacement and strain on implant or surrogate bone surface. |

| ASTM F1717 / F2077 Standards | Definitive protocols for testing spinal constructs; provide the experimental framework for generating validation data. |

Diagram 2: Evidence hierarchy for regulatory acceptance.

Building the Digital Twin: A Step-by-Step Methodological Protocol

Within the broader thesis "Protocol for Validating Spinal Implant Computational Models," the accurate reconstruction of patient-specific spinal anatomy from medical imaging data is the foundational step. This application note details protocols for creating high-fidelity 3D anatomical models from CT or MRI scans, which serve as the geometric basis for subsequent finite element analysis (FEA) and computational validation of implant performance. The precision of this step directly impacts the predictive validity of the entire computational modeling pipeline.

Imaging Modality Selection

The choice between CT and MRI is dictated by the anatomical and tissue features of interest for implant validation.

| Modality | Optimal Use Case in Spinal Implant Research | Typical Resolution | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computed Tomography (CT) | Bony anatomy (vertebrae, pedicles, endplates), implant-bone interface, porous structures. | 0.25 - 0.625 mm slice thickness | Excellent bone contrast; high spatial resolution; fast acquisition. | Poor soft tissue contrast; ionizing radiation. |

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) | Soft tissues (intervertebral discs, ligaments, spinal cord, nerve roots), cartilage, bone marrow edema. | 0.5 - 1.5 mm slice thickness (3D sequences) | Superior soft tissue contrast; no ionizing radiation. | Lower bone definition; longer scan times; more sensitive to motion. |

Recommended Imaging Parameters for Research-Grade Reconstruction

Based on current literature and best practices for computational model generation, the following acquisition parameters are recommended.

| Parameter | CT Protocol (Cortical Bone) | MRI Protocol (Disc/Ligament) |

|---|---|---|

| Slice Thickness | ≤ 0.625 mm | ≤ 1.0 mm (3D isotropic voxels preferred) |

| In-Plane Pixel Spacing | ≤ 0.4 mm | ≤ 0.5 mm |

| Scan Field of View | Focused on target spinal segment(s) | Encompasses relevant soft tissue structures |

| Kernel/Sequence | Bone (sharp) kernel | T2-weighted 3D SPACE or equivalent |

| Dose/Contrast | As Low As Reasonably Achievable (ALARA) | N/A (non-contrast typically sufficient) |

Experimental Protocol: Anatomical Model Reconstruction Workflow

Materials & Software Requirements

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Example Products/Tools |

|---|---|---|

| DICOM Image Dataset | Raw, unprocessed medical images in standard Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine format. | Output from CT/MRI scanners. |

| Image Processing Software | For initial image enhancement, filtering, and format conversion. | ImageJ, Horos, 3D Slicer. |

| Segmentation Software | Core tool for labeling and isolating anatomical structures of interest from image data. | Mimics (Materialise), Simpleware ScanIP (Synopsys), ITK-SNAP, 3D Slicer. |

| 3D Model Editor (CAD) | For smoothing, repairing mesh defects, and preparing geometry for simulation. | Geomagic Wrap, Blender, MeshLab. |

| Reference Anatomical Atlas | Digital or literature-based guide for accurate structural identification during segmentation. | Visible Human Project, published anatomical studies. |

| High-Performance Workstation | Computer with significant RAM (≥32 GB), multi-core CPU, and dedicated GPU for handling large datasets. | Custom-built or commercial scientific workstations. |

Detailed Stepwise Protocol

Step 1: Data Acquisition & Import

- Acquire DICOM datasets per the parameters specified in Tables 1 & 2.

- Import the DICOM series into segmentation software. Ensure correct orientation (anatomical planes) and verify scale using embedded pixel spacing metadata.

Step 2: Image Pre-processing

- Apply noise reduction filters (e.g., non-local means, median filter) to improve signal-to-noise ratio, especially for MRI data.

- Enhance contrast using histogram equalization or contrast-limited adaptive histogram equalization (CLAHE) to better differentiate tissue boundaries.

- For multi-specimen studies, consider spatial normalization to a standard coordinate system.

Step 3: Multi-Structure Segmentation This is the most critical and time-intensive step.

- Thresholding: Use Hounsfield Unit (HU) ranges for CT data to create an initial mask for bone.

- Typical Cortical Bone HU: > 300

- Typical Trabecular Bone HU: 100 - 300

- Region Growing: Seed within a target vertebra and apply connectivity constraints to isolate it from adjacent structures.

- Manual Correction & Refinement: Use manual slice-by-slice editing tools to correct errors at boundaries with low contrast (e.g., disc-vertebra interface, posterior elements).

- Separate Segmentation: Repeat the process for each anatomical structure required for the model (e.g., individual vertebrae, intervertebral discs, ligament attachments).

- Label Fields: Assign each segmented structure a unique label.

Step 4: 3D Model Generation (Meshing)

- Calculate a 3D surface mesh (typically STL format) from each label field using the marching cubes algorithm.

- Adjust mesh quality parameters: target triangle count (balancing detail and computational load), smoothing iterations, and hole-filling.

Step 5: Post-Processing & Validation

- Import surface meshes into a 3D editor or CAD software.

- Perform mesh repair: fix non-manifold edges, remove self-intersections, and close holes.

- Apply minimal smoothing to reduce stair-step artifacts from voxel data without losing anatomical accuracy.

- Geometric Validation: Compare key dimensions (e.g., vertebral body width, pedicle diameter, disc height) of the 3D model against direct measurements from the source images or physical specimens. Document discrepancies.

Step 6: Preparation for Simulation

- Convert surface mesh to a volumetric mesh (tetrahedral or hexahedral elements) suitable for FEA within dedicated pre-processor software (e.g., ANSYS, Abaqus, FEBio).

- Assign material properties and boundary conditions in subsequent steps of the broader validation protocol.

Workflow Diagram

Workflow for Anatomical Model Reconstruction

Data Presentation & Metrics for Validation

Quantitative Validation Metrics

The accuracy of the reconstructed model must be assessed against a ground truth. Common metrics are summarized below.

| Validation Metric | Description | Acceptance Criterion (Typical) | Measurement Tool |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) | Measures spatial overlap between segmented model and ground truth mask (2D or 3D). Range: 0 (no overlap) to 1 (perfect overlap). | DSC > 0.90 for bone; >0.85 for soft tissue. | Image analysis software (e.g., ITK-SNAP). |

| Average Surface Distance (ASD) | The average of all distances from points on model A to the closest point on model B. | ASD < 0.5 mm for bony anatomy. | Mesh comparison software (e.g., CloudCompare, Meshlab). |

| Hausdorff Distance (HD) | The maximum distance from points on model A to model B (measures worst-case error). | HD < 1.5 mm for bony anatomy. | Mesh comparison software. |

| Geometric Dimension Comparison | Linear measurements (e.g., disc height, vertebral width) compared to caliper measurements on specimen or image. | Difference < 5% of measured value. | CAD software / Image ruler tool. |

A rigorous and reproducible protocol for anatomical model reconstruction from CT/MRI data is essential for generating valid computational models for spinal implant research. Adherence to high-resolution imaging parameters, meticulous multi-structure segmentation, and quantitative geometric validation forms the critical first step in the thesis pipeline, ensuring that subsequent biomechanical simulations are based on a faithful representation of patient anatomy.

Within the protocol for validating spinal implant computational models, the accurate assignment of material properties and the biomechanical representation of spinal tissues are foundational. This step directly dictates the predictive fidelity of Finite Element Analysis (FEA) or Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) models under physiological loading. This document outlines contemporary approaches, data, and experimental protocols essential for this phase.

Quantitative Material Property Data for Spinal Tissues

Material properties are typically derived from experimental testing and integrated into computational models as linear/non-linear elastic, hyperelastic (e.g., Mooney-Rivlin, Ogden), or viscoelastic constitutive models.

Table 1: Representative Material Properties for Spinal Tissues

| Tissue/Component | Constitutive Model | Key Parameters (Mean ± SD or Range) | Source / Testing Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical Bone | Linear Elastic (Orthotropic) | E₁ = 11.4 ± 3.1 GPa, E₂ = E₃ = 5.9 ± 1.2 GPa, ν = 0.28 ± 0.06 | Uniaxial tensile/compression test on machined specimens. |

| Cancellous Bone | Non-linear Elastic (Crushable Foam) | Apparent Density: 0.1-0.3 g/cm³, Elastic Modulus: 50-500 MPa, Plateau Stress: 1-10 MPa | Quasi-static compression of core samples, density-modulus correlation. |

| Annulus Fibrosus (Ground Substance) | Hyperelastic (Mooney-Rivlin) | C10=0.12 MPa, C01=0.09 MPa, Bulk Modulus (K)=1.0 GPa | Biaxial or confined compression testing of hydrated tissue. |

| Nucleus Pulposus | Hyperelastic (Neo-Hookean) / Incompressible Fluid | Shear Modulus (μ) = 0.005 - 0.02 MPa, K = 1.67 GPa | Indentation or confined compression; often modeled as fluid cavity in FEA. |

| Spinal Ligaments (ALL, PLL, LF) | Non-linear Tension-Only (Viscoelastic) | Toe Region: E=5-10 MPa, Linear Region: E=50-150 MPa, Failure Strain: 15-30% | Uniaxial tensile test at low strain rates (0.01-0.1 /s). |

| Cartilage Endplate | Poroelastic | Permeability: k = 1e-15 ± 0.5e-15 m⁴/Ns, Elastic Modulus: 20-30 MPa | Confined compression stress-relaxation test. |

Experimental Protocols for Property Determination

These protocols provide the empirical data required for model inputs in Table 1.

Protocol 2.1: Uniaxial Tensile Testing for Spinal Ligaments

- Objective: To obtain non-linear stress-strain curves and failure parameters for ligaments (e.g., Ligamentum Flavum).

- Materials: Fresh-frozen human cadaveric spinal segments, saline solution, tensile testing machine with environmental chamber, cryo-clamps, digital image correlation (DIC) system.

- Procedure:

- Dissect ligament, ensuring minimal damage. Maintain hydration with 0.9% saline.

- Machine ends are potted in polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) blocks for secure gripping.

- Mount specimen in testing machine equipped with a saline bath or spray system at 37°C.

- Apply a pre-load of 0.5 N to remove slack.

- Conduct a preconditioning cycle (10 cycles at 0.5% strain).

- Perform tensile test to failure at a quasi-static strain rate of 0.1%/s.

- Simultaneously, use DIC to measure full-field strain, accounting for grip artifacts.

- Record force (N) and displacement (mm). Calculate engineering stress (Force/initial cross-sectional area) and strain (Displacement/original gauge length).

- Data Analysis: Fit stress-strain data to a Fung-type exponential or piecewise linear model. Extract toe-region modulus, linear-region modulus, and failure stress/strain.

Protocol 2.2: Confined Compression for Intervertebral Disc Properties

- Objective: To determine the compressive modulus and hydraulic permeability of the nucleus pulposus/annulus ground substance.

- Materials: Isolated disc or tissue plug, confined compression chamber with porous platen, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), load cell, displacement transducer.

- Procedure:

- Place a cylindrical tissue sample (e.g., nucleus) into the impermeable chamber fitted with a porous platen at the top.

- Submerge the chamber in 37°C PBS.

- Apply a small pre-strain (2-5%) and allow stress to equilibrate (30 mins).

- Apply a rapid step increase in compressive strain (e.g., 5%).

- Record the resulting stress as it relaxes over time (typically 30-60 mins).

- Repeat for multiple strain increments.

- Data Analysis: Fit the stress relaxation data to a linear biphasic (poroelastic) theory model (e.g., using the Hayes equation) to extract the aggregate modulus (Ha) and hydraulic permeability (k).

Tissue Modeling Approaches: Workflow & Logical Relationships

Title: Workflow for Assigning Material Properties in Spinal Implant Models

Title: Forward vs Inverse Material Parameter Identification

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Spinal Tissue Biomechanical Testing

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), 0.1M | Hydration and ionic balance maintenance for soft tissues during testing and storage. | Must be isotonic and used at 37°C to prevent tissue degeneration. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets | Added to storage solution to inhibit enzymatic degradation of collagen and proteoglycans in soft tissues. | Critical for maintaining native mechanical properties in cadaveric tissues. |

| Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) Resin | For potting bone or ligament ends to ensure uniform load distribution and prevent slippage in grips. | Low exotherm versions preferred to avoid thermal damage to tissue. |

| Silicone-based Mold Release Agent | Prevents tissue samples from adhering to potting molds or compression chambers. | Must be biocompatible and not diffuse into tissue. |

| Digital Image Correlation (DIC) System | Non-contact, full-field 3D strain measurement on tissue surfaces during mechanical testing. | Requires application of a high-contrast speckle pattern to the tissue surface. |

| Porous Titanium or Sintered Bronze Platens | Used in confined/indentation tests to allow fluid exudation while applying compressive load. | Pore size must be small enough to support tissue but allow fluid flow. |

| Environmental Chamber with Temperature Control | Encloses the test setup to maintain physiological temperature (37°C) and humidity. | Prevents tissue drying, which significantly alters mechanical properties. |

| Calibrated Microsphere Suspensions | Used for permeability measurement in poroelastic testing via tracer methods. | Sphere size must be larger than proteoglycan mesh size to track fluid flow. |

Within the protocol for validating spinal implant computational models, Step 3 is the core of translating a conceptual implant design into a robust Finite Element (FE) model capable of predictive biomechanical analysis. The accuracy of this step directly dictates the validity of subsequent verification and validation steps. This application note details methodologies for geometric modeling, mesh generation, and contact definition for implants like cervical plates, lumbar pedicle screw systems, and interbody cages.

Implant Modeling and Geometric Idealization

Implant geometry is sourced from CAD designs or 3D scanned physical specimens. A critical decision is the level of geometric idealization required for the simulation objectives.

| Geometric Feature | High-Fidelity Model | Idealized Model | Rationale for Choice |

|---|---|---|---|

| Threads (Screws) | Explicit 3D threads modeled. | Smoothed cylindrical shaft with adjusted friction coefficients. | Explicit threads increase elements by >300% and require nonlinear contact. Use for pull-out studies. |

| Surface Texturing | Micro-scale roughness features included. | Macroscale geometry with averaged surface properties. | Critical for osseointegration studies; often omitted for macro-mechanics. |

| Small Fillets/Chamfers | Precisely modeled. | Simplified to sharp edges. | Simplification reduces mesh complexity with minimal impact on global stiffness. |

| Porosity (e.g., Ti/Ta lattice) | Homogenized material properties. | Explicit strut modeling. | Explicit modeling is computationally prohibitive for full assembly; homogenization is standard. |

Protocol 2.1: CAD Preparation for FE

- Import solid geometry (STEP or IGES format) into pre-processor (e.g., ANSYS SpaceClaim, Altair HyperMesh).

- Defeaturing: Remove non-structural details (logo engraving, minute fillets <0.1mm).

- Healing: Repair any gaps, overlaps, or non-manifold edges from translation.

- Partitioning: Split complex volumes into simpler, mappable regions for structured meshing (e.g., separate screw head from shaft).

- Export the cleaned geometry as a Parasolid (.x_t) file for meshing.

Meshing Strategies and Quality Metrics

Meshing converts geometry into discrete elements. A convergence analysis is mandatory within the broader thesis validation protocol.

| Mesh Type | Element Formulation | Typical Size at Implant | Application & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetrahedral (Tet10) | Quadratic, 10-node | 0.5 - 1.0 mm | Complex geometries. Softer than hexahedral; use with caution in bending. |

| Hexahedral (Hex8/Hex20) | Linear/Quadratic, 8/20-node | 0.3 - 0.7 mm | Preferred for accuracy and efficiency. Requires geometry partitioning. |

| Mixed (Hex-Dominant) | Hybrid | Varies | Hex in bulk regions, tets in complex zones. Practical compromise. |

Protocol 3.1: Mesh Convergence Analysis Objective: Determine mesh density where solution (e.g., peak von Mises stress in implant) changes by <5%.

- Generate 4 mesh sets with global element sizes progressively refined by a factor of ~1.5 (e.g., 2.0mm, 1.3mm, 0.9mm, 0.6mm).

- Apply identical boundary conditions and a representative load case (e.g., flexion moment).

- Solve each model and extract a key output parameter (P):

P_max_stress_implant,P_max_strain_bone. - Calculate relative error between successive meshes:

Error (%) = |(P_fine - P_coarse) / P_fine| * 100. - Select the mesh density one level coarser than the point where error falls below 5% as the converged mesh.

Protocol 3.2: Mesh Quality Assurance Check Before solution, validate mesh quality against these thresholds in the pre-processor:

- Jacobian Ratio (Quad/Hex): > 0.6

- Skewness: < 0.7 (Tet), < 0.5 (Hex)

- Aspect Ratio: < 10 for bone-implant interface regions

- Element Warping (Quad/Hex): < 15 degrees

Contact Definitions and Interface Modeling

This defines mechanical interactions between implant components and between implant and bone.

| Contact Type | Formulation | Friction Coefficient (μ) | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bonded | No separation/slip. | N/A | Cemented interfaces, locked screw-plate junctions. |

| Frictional | Slip allowed after friction overcome. | 0.2 - 0.6 (Ti-Ti) | Bone-implant interface (primary stability), screw-plate lag. |

| Frictionless | Free slip, no shear resistance. | 0.0 | Conservative simplification of lubricated contact. |

| No Separation | Allows slip, prevents gap opening. | N/A | Model of retained but not bonded components. |

Protocol 4.1: Defining Bone-Implant Interface Contact

- Surface Preparation: Designate the implant outer surface as the "Contact" body and the adjacent bone cavity surface as the "Target".

- Type Selection: For primary stability simulation, select "Frictional".

- Parameter Definition:

- Set friction coefficient (

μ) to 0.4 as a baseline for Titanium-Trabecular bone. - Define normal behavior as "Augmented Lagrange" for robustness.

- Set pinball region to automatically handle initial gaps/penetrations.

- Set friction coefficient (

- Advanced Controls: Enable "Adjust to Touch" to ensure initial contact. Use a symmetric bilateral contact for scenarios where either body can be contact/target.

Protocol 4.2: Modeling Threaded Contacts in Pedicle Screws

For explicit threads, a frictional contact (μ=0.2) is defined between all thread flanks and bone. For idealized smooth shafts:

- Define a bonded contact zone in the predicted region of osseointegration (proximal 1/3 of shaft).

- Define a frictional contact (

μ=0.3-0.5) over the remaining shaft to simulate initial mechanical interlock.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Solution | Function in Computational Modeling |

|---|---|

| CAD Software (SolidWorks, Creo) | Generates the initial, precise 3D geometry of the implant design. |

| FE Pre-processor (ANSYS, Abaqus/CAE, HyperMesh) | Platform for geometry healing, partitioning, meshing, and contact definition. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Enables running large, nonlinear contact models with fine meshes in feasible time. |

| ISO 5832 / ASTM F136 Titanium Alloy Material Data | Provides validated elastic-plastic material properties for implant material definition. |

| Mesh Convergence Script (Python/Matlab) | Automates the process of batch meshing, solving, and result extraction for convergence studies. |

| Medical Image Data (μCT of cadaveric bone) | Source for generating accurate 3D bone geometry (vertebrae) to model the implant's environment. |

This protocol details the critical step of applying physiological boundary conditions and load cases within the broader thesis framework, "Protocol for Validating Spinal Implant Computational Models." This step transforms a generic finite element model into a validated, predictive tool by simulating in vivo mechanical environments. Accurate application is paramount for predicting implant performance, adjacent segment effects, and bone remodeling.

Core Principles & Quantitative Data

Boundary conditions (BCs) constrain model displacement, while load cases represent physiological forces. Key quantitative data for the lumbar spine (L1-L5) are summarized below.

Table 1: Representative Physiological Loads for Lumbar Spine Analysis

| Load Case | Magnitude (N) | Direction | Application Point | Primary Physiological Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compression | 500 - 1200 | Axial (Inferior-Superior) | Superior Endplate | Standing, Weight-Bearing |

| Flexion | 7.5 - 10 Nm | Sagittal Plane Moment | L3 Vertebral Body | Forward Bending |

| Extension | 7.5 - 10 Nm | Sagittal Plane Moment | L3 Vertebral Body | Backward Bending |

| Lateral Bending | 7.5 - 10 Nm | Coronal Plane Moment | L3 Vertebral Body | Side Bending |

| Axial Rotation | 5 - 7.5 Nm | Axial Plane Moment | L3 Vertebral Body | Twisting/Torsion |

| Combined Loading (Gait) | 400-800 N + Variable Moments | Multi-Axial | Superior Endplate | Walking |

Table 2: Common Boundary Condition Definitions

| Constraint Type | Degrees of Freedom Constrained | Typical Anatomical Application | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed (Encastered) | All (UX, UY, UZ, ROTX, ROTY, ROTZ) | Inferior Endplate of Lowest Vertebra (e.g., L5/S1) | Simulates fixation to immobile pelvis. |

| Frictionless Support | Translations (UX, UY, UZ) | Inferior Endplate | Allows rotation but prevents rigid body motion. |

| Symmetry BC | UX=0, ROTY=0, ROTZ=0 | Mid-sagittal Plane | Reduces model size for symmetric analyses. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Application of Pure Moment Loading for Range-of-Motion (ROM) Simulation

Objective: To simulate standard flexion, extension, lateral bending, and axial rotation for implant comparison.

- Model Setup: Isolate the spinal segment (e.g., L4-L5) with implant. Fix all degrees of freedom at the inferior endplate of the lower vertebra (L5).

- Load Application: Apply a pure moment up to the target value (e.g., 10 Nm) incrementally to the superior endplate of the upper vertebra (L4). Use a coupling constraint or reference point (RP) tied to the superior endplate to apply the moment.

- Data Acquisition: At each load increment, record the angular rotation (in degrees) of the superior vertebra relative to the inferior vertebra in the plane of the applied moment.

- Output: Generate a moment-rotation curve. Calculate the Neutral Zone (NZ) and Elastic Zone (EZ) from the hysteresis loop. Compare ROM to intact spine and other implant models.

Protocol 3.2: Application of Combined Compression-Flexion Loading

Objective: To simulate a more physiologically demanding activity, such as lifting.

- Model Setup: As per Protocol 3.1.

- Load Application: a. First, apply a static axial preload of 500 N to the superior endplate RP to simulate body weight. b. Subsequently, apply a linearly increasing flexion moment (0 to 10 Nm) to the same RP, superimposed on the preload.

- Data Acquisition: Record intradiscal pressure (if modeled), facet joint contact forces, implant stresses, and segmental rotation.

- Output: Report peak von Mises stress in implant components, contact forces at the facet joints, and total angular displacement.

Protocol 3.3: Kinematic Validation via Displacement-Control Loading

Objective: To validate the model against in vitro biomechanical testing data.

- Input Data: Obtain experimental rotation data from a cadaveric study for a specific load (e.g., 8 Nm flexion).

- Model Setup: Apply boundary conditions identical to the experimental setup (e.g., potting of inferior vertebra).

- Load Application: Instead of applying a moment, prescribe the angular displacement (from experiment) to the superior vertebra.

- Data Acquisition: Compute the reaction moment generated by the model at the fixed boundary.

- Output: Compare the model-predicted reaction moment to the experimental applied moment (8 Nm). Calculate correlation coefficient (R²) and relative error.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: BC & Load Application Workflow

Diagram 2: Multi-Step Load Case for Gait

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Boundary Condition & Load Application

| Item / Solution | Function in Protocol | Example Product / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Finite Element Software | Platform for applying BCs, loads, and solving. | Abaqus, ANSYS, FEBio. |

| Material Property Datasets | Defines nonlinear, isotropic/orthotropic behavior for bone, ligaments, and implant. | Published data for cortical/cancellous bone, titanium alloy (Ti-6Al-4V), PEEK. |

| Kinematic Coupling Constraint | Applies moments/forces to a reference point tied to a vertebral surface. | Abaqus: Coupling/MPC constraint. ANSYS: Remote Displacement/Force. |

| Nonlinear Solver | Essential for solving large deformations and contact under complex loads. | Abaqus/Standard, ANSYS Mechanical APDL, FEBio's Newton-Raphson solver. |

| Validation Dataset (Benchmark) | In vitro cadaveric ROM data for intact and implanted states. | Published data from Wilke et al. (1998) or subsequent studies. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Reduces solution time for complex, nonlinear, multi-step analyses. | Local cluster or cloud-based solutions (AWS, Azure). |

| Python/Matlab Scripting | Automates the application of multi-step load cases and batch post-processing. | Custom scripts for Abaqus Python API or ANSYS ACT. |

Within the broader thesis on a Protocol for Validating Spinal Implant Computational Models, the design of physical bench tests is the critical translational step. These tests provide empirical, quantitative data to assess the predictive accuracy of finite element analysis (FEA) and computational biomechanics models. This application note details the design principles and specific protocols for corresponding physical bench tests, ensuring a rigorous validation framework.

Core Principles for Corresponding Test Design

The physical test must be the biomechanical analogue of the computational model. Correspondence is defined by:

- Identical Boundary Conditions: Fixturing in the physical test must replicate the model's constraints.

- Identical Loading Profiles: Magnitude, rate, direction, and application point of loads must match.

- Identical Outcome Measures: The measured physical parameters (e.g., strain, displacement, load) must be the direct counterparts of the model's output variables.

- Use of Identical Constructs: The implant, screw, and surrogate bone (e.g., polyurethane foam block) specifications must be the same in both realms.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quasi-Static Axial Compression/Bending Test for a Lumbar Vertebral Body Replacement (VBR) Construct

Objective: To validate computational model predictions of stiffness, subsidence risk, and load distribution under physiological loading.

Detailed Methodology:

- Construct Preparation:

- Use a standardized rigid polyurethane foam block (Grade: 20 pcf / 0.32 g/cm³) to simulate osteoporotic cancellous bone, per ASTM F1839.

- Machine a block to representative vertebral body dimensions (e.g., 25mm height x 40mm width x 40mm depth).

- Prepare the VBR implant per manufacturer instructions.

- Assemble the VBR implanted centrally within the foam block, ensuring uniform endplate contact. Pot the ends in dental stone or low-melting-point alloy within loading platens to ensure even load distribution.

Instrumentation & Setup:

- Mount the construct onto a servo-hydraulic or electro-mechanical materials testing system (e.g., Instron, MTS).

- Calibrate the system's load cell and actuator displacement transducer.

- Affix a minimum of three uniaxial strain gauges (e.g., 350Ω) or a digital image correlation (DIC) system to the implant surface and/or foam block to map strain fields.

- Position a displacement sensor (LVDT) to measure inter-segmental compression.

Loading Protocol:

- Pre-condition the construct with 10 cycles of compression from 50N to 500N at 1 Hz.

- Perform a quasi-static compression test to failure or to a predefined limit (e.g., 5000N) at a displacement rate of 1 mm/min.

- Continuously record load (N), actuator displacement (mm), strain gauge microstrain (µε), and LVDT displacement (mm).

Data Analysis:

- Calculate construct stiffness (N/mm) as the slope of the linear region of the load-displacement curve.

- Identify yield load from the 0.2% offset method.

- Correlate experimental strain maps with FEA-predicted strain contours.

Table 1: Representative Data from VBR Compression Validation Study

| Metric | Computational Model Prediction | Physical Bench Test Result (Mean ± SD, n=5) | Percent Difference | Validation Criterion Met? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct Stiffness (N/mm) | 2450 | 2310 ± 185 | 5.7% | Yes (<10%) |

| Yield Load (N) | 4150 | 3880 ± 310 | 6.5% | Yes (<15%) |

| Peak Strain at Location A (µε) | -1250 | -1180 ± 95 | 5.6% | Yes (<10%) |

Protocol 2: Dynamic Cyclic Fatigue Test for a Pedicle Screw-Rod Construct

Objective: To validate model predictions of fatigue life and failure mode under cyclic physiological loading.

Detailed Methodology:

- Construct Preparation:

- Use ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) or composite test blocks with pre-drilled pilot holes as a consistent surrogate for bone.

- Instrument the block with two pedicle screws (per manufacturer technique) connected by a titanium rod (5.5mm diameter).

- Secure the block in a custom fixture that allows pure moment application.

Setup & Fixturing:

- Mount the fixture on a dynamic biaxial testing system capable of applying simultaneous axial and torsional loads.

- The fixture must allow unconstrained motion along the loading axis to apply pure moments via follower load principles.

Loading Protocol (Based on ASTM F1717):

- Apply a constant compressive pre-load of 200N.

- Superimpose a cyclic sinusoidal flexion-extension moment at a frequency of 2-5 Hz.

- Load magnitude: ±5 Nm to ±10 Nm (based on model simulation loads).

- Cycle until construct failure (defined as screw fracture, rod fracture, or catastrophic loosening) or to 5 million cycles (run-out).

Data Analysis:

- Record cycles to failure.

- Document failure mode via macroscopic and microscopic imaging.

- Compare predicted high-stress locations from FEA with actual failure initiation sites.

Table 2: Example Fatigue Test Validation Matrix

| Loading Condition | FEA Predicted Fatigue Life (Cycles) | Experimental Mean Life (Cycles, n=3) | Observed Failure Mode | Predicted High-Stress Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ±7.5 Nm, 4 Hz | 1.2 x 10⁶ | 0.9 x 10⁶ | Screw fracture at shank-neck junction | Screw shank-neck junction |

| ±10 Nm, 4 Hz | 3.5 x 10⁵ | 2.8 x 10⁵ | Rod fracture near screw interface | Rod at set-screw contact |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item | Specification / Example | Primary Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Surrogate Bone | Rigid Polyurethane Foam (20 pcf) | Provides a consistent, isotropic material with known properties to simulate cancellous bone for screw pull-out/insertion and implant subsidence tests. |