Verification and Validation in Computational Biomechanics: A Comprehensive Guide for Building Credible Models

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Verification and Validation (V&V) processes essential for establishing credibility in computational biomechanics models.

Verification and Validation in Computational Biomechanics: A Comprehensive Guide for Building Credible Models

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Verification and Validation (V&V) processes essential for establishing credibility in computational biomechanics models. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles distinguishing verification ('solving the equations right') from validation ('solving the right equations'). The scope extends to methodological applications across cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, and soft tissue mechanics, alongside troubleshooting techniques like sensitivity analysis and mesh convergence studies. Finally, it explores advanced validation frameworks and comparative pipeline analyses critical for clinical translation, synthesizing best practices to ensure model reliability in biomedical research and patient-specific applications.

The Core Principles of V&V: Building a Foundation for Model Credibility

In the field of computational biomechanics, where models are increasingly used to simulate complex biological systems and inform medical decisions, establishing confidence in simulation results is paramount. Verification and Validation (V&V) provide the foundational framework for building this credibility. These processes are particularly crucial when models are designed to predict patient outcomes, as erroneous conclusions can have profound effects beyond the mere failure of a scientific hypothesis [1]. The fundamental distinction between these two concepts is elegantly captured by their common definitions: verification is "solving the equations right" (addressing the mathematical correctness), while validation is "solving the right equations" (ensuring the model accurately represents physical reality) [1].

As computational models grow more complex to capture the intricate behaviors of biological tissues, the potential for errors increases proportionally. These issues were first systematically addressed in computational fluid dynamics (CFD), with publications soon following in solid mechanics [1]. While no universal standard exists due to the rapidly evolving state of the art, several organizations, including ASME, have developed comprehensive guidelines [1] [2]. The adoption of V&V practices is becoming increasingly mandatory for peer acceptance, with many scientific journals now requiring some degree of V&V for models presented in publications [1].

Core Definitions and Their Practical Application

The V&V Process Workflow

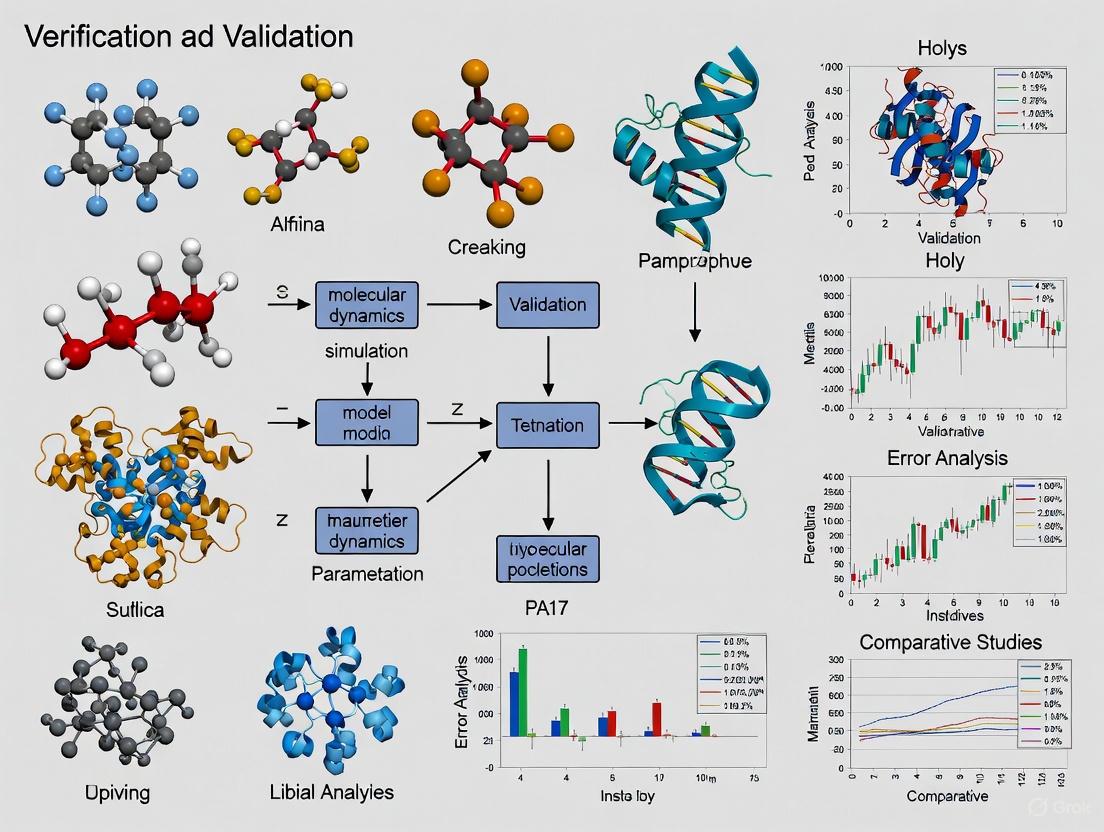

The relationship between the real world, mathematical models, and computational models, and how V&V connects them, can be visualized in the following workflow. Verification ensures the computational model correctly implements the mathematical model, while validation determines if the mathematical model accurately represents reality [1].

Comparative Analysis of V&V Concepts

The following table details the core objectives, questions, and key methodologies for Verification and Validation.

Table 1: Fundamental Concepts of Verification and Validation

| Aspect | Verification | Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Core Question | "Are we solving the equations correctly?" | "Are we solving the correct equations?" [1] |

| Primary Objective | Ensure the computational model accurately represents the underlying mathematical model and its solution [1]. | Determine the degree to which the model is an accurate representation of the real world from the perspective of its intended uses [1]. |

| Primary Focus | Mathematics and numerical accuracy. | Physics and conceptual accuracy. |

| Key Process | Code Verification: Ensuring algorithms work as intended.Calculation Verification: Assessing errors from domain discretization (e.g., mesh convergence) [1]. | Comparing computational results with high-quality experimental data for the specific context of use [1] [2]. |

| Error Type | Errors in implementation (e.g., programming bugs, inadequate iterative convergence). | Errors in formulation (e.g., insufficient constitutive models, missing physics) [1]. |

| Common Methods | Comparison to analytical solutions; mesh convergence studies [1]. | Validation experiments designed to tightly control quantities of interest [1]. |

Quantitative V&V Benchmarks and Experimental Protocols

Established Quantitative Benchmarks in the Literature

Successful application of V&V requires meeting specific quantitative benchmarks. The table below summarizes key metrics and thresholds reported in computational biomechanics research.

Table 2: Quantitative V&V Benchmarks from Computational Biomechanics Practice

| V&V Component | Metric | Typical Benchmark | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Code Verification | Agreement with Analytical Solution | ≤ 3% error [1] | Transversely isotropic hyperelastic model under equibiaxial stretch [1]. |

| Calculation Verification | Mesh Convergence Threshold | < 5% change in solution output [1] | Finite element studies of spinal segments [1]. |

| Validation | Comparison with Experimental Data | Context- and use-case dependent; requires statistical comparison and uncertainty quantification [1] [3]. | General practice for model validation against physical experiments. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for V&V

Protocol for Mesh Convergence Study (Verification)

A mesh convergence study is a fundamental calculation verification activity to ensure that the discretization of the geometry does not unduly influence the simulation results.

- Problem Definition: Select a representative, well-defined problem relevant to the intended use of the full computational model.

- Baseline Mesh Generation: Create an initial mesh with a defined element size and type. The element size should be based on the geometric features of the model.

- Simulation Execution: Run the simulation using the baseline mesh and record the key output Quantity of Interest (QoI), such as peak stress or displacement.

- Systematic Refinement: Refine the mesh globally or in regions of high gradients (e.g., stress concentrations) by reducing the element size. The refinement ratio between subsequent meshes should be consistent (e.g., a factor of 1.5).

- Solution Tracking: Execute the simulation for each refined mesh and record the same QoI.

- Convergence Assessment: Calculate the relative difference in the QoI between successive mesh refinements. The study is considered complete when this relative difference falls below a pre-defined threshold (e.g., 5%) [1]. The solution from the finest mesh, or an extrapolated value, is typically taken as the converged result.

Protocol for a Model Validation Experiment

Validation requires a direct comparison of computational results with high-quality experimental data.

- Context of Use Definition: Clearly define the specific purpose of the model and the relevant QoIs for validation (e.g., ligament strain, joint contact pressure).

- Experimental Design: Design a physical experiment that can accurately measure the identified QoIs under well-controlled boundary conditions and loading scenarios. The experiment should be replicable.

- Specimen Characterization: Document all relevant characteristics of the physical specimen(s), including geometry, material properties, and any assumptions.

- Computational Model Setup: Develop a computational model (e.g., a Finite Element model) that replicates the exact geometry, boundary conditions, and loading of the physical experiment.

- Data Collection & Simulation: Conduct the physical experiment to collect empirical data for the QoIs. Run the simulation with the same inputs.

- Quantitative Comparison: Statistically compare the computational predictions with the experimental measurements. This goes beyond visual comparison and should assess both bias (systematic error) and random (statistical) errors [1].

- Uncertainty Quantification (UQ): Report the uncertainties associated with both the experimental data and the computational inputs. Use UQ methods to propagate these uncertainties and establish confidence bounds on the model predictions [3] [2]. The model is considered validated for its context of use if the simulation results fall within the agreed-upon confidence bounds of the experimental data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table catalogs key computational tools and methodologies that form the essential "reagents" for conducting V&V in computational biomechanics.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for V&V

| Item / Solution | Function in V&V Process | Example Context |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Solutions | Serves as a benchmark for Code Verification; provides a "known answer" to check numerical implementation [1]. | Verifying a hyperelastic material model implementation against an analytical solution for equibiaxial stretch [1]. |

| High-Fidelity Experimental Data | Provides the ground-truth data required for Validation; must be of sufficient quality and relevance to the model's context of use [1]. | Using video-fluoroscopy to measure in-vivo ligament elongation patterns for validating a subject-specific knee model [4]. |

| Mesh Generation/Refinement Tools | Enable Calculation Verification by allowing the systematic study of discretization error [1]. | Performing a mesh convergence study in a finite element analysis of a spinal segment [1]. |

| Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) Frameworks | Quantify and propagate uncertainties from various sources (e.g., input parameters, geometry) to establish confidence bounds on predictions [3] [2]. | Assessing the impact of variability in material properties derived from medical image data on stress predictions in a bone model [1]. |

| Sensitivity Analysis Tools | Identify which model inputs have the most significant influence on the outputs; helps prioritize efforts in UQ and Validation [1]. | Determining the relative importance of ligament stiffness, bone geometry, and contact parameters on knee joint mechanics. |

| 2,2,7-Trimethylnonane | 2,2,7-Trimethylnonane, CAS:62184-53-6, MF:C12H26, MW:170.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 14,15-Ditridecyloctacosane | 14,15-Ditridecyloctacosane, CAS:61625-16-9, MF:C54H110, MW:759.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Evolving Landscape: VVUQ and Digital Twins

The field is evolving from V&V to VVUQ, formally incorporating Uncertainty Quantification as a critical third pillar. This is especially vital for emerging applications like Digital Twins in precision medicine [3]. A digital twin is a virtual information construct that is dynamically updated with data from its physical counterpart and used for personalized prediction and decision-making [3].

For digital twins in healthcare, robust VVUQ processes are non-negotiable for building clinical trust. This involves new challenges, such as determining how often a continuously updated digital twin must be re-validated and how to effectively communicate the levels of uncertainty in predictions to clinicians [3]. The ASME standards, including V&V 40 for medical devices, provide risk-based frameworks for assessing the credibility of such models, ensuring they are "fit-for-purpose" in critical clinical decision-making [3] [2].

In computational biomechanics and systems biology, the credibility of simulation results is paramount for informed decision-making in research and drug development. The process of establishing this credibility rests on the pillars of Verification and Validation (V&V). Verification addresses the question "Are we solving the equations correctly?" and is concerned with identifying numerical errors. Validation addresses the question "Are we solving the correct equations?" and focuses on modeling errors [5]. For researchers and drug development professionals, confusing these two distinct error types can lead to misguided model refinements, incorrect interpretations of system biology, and ultimately, costly failures in translating computational predictions into real-world applications. This guide provides a structured comparison of these errors, supported by experimental data and methodologies, to equip scientists with the tools for robust model assessment within a rigorous V&V framework.

Defining the Error Types: A Comparative Basis

At its core, the distinction between numerical and modeling error is a distinction between solution fidelity and conceptual accuracy.

Modeling Error: This is a deficiency in the mathematical representation of the underlying biological or physical system. It arises from incomplete knowledge or deliberate simplification of the phenomena being studied. Sources include missed biological interactions, incorrect reaction kinetics, or uncertainty in model parameters [6] [7] [8]. In the context of V&V, modeling error is a primary target of validation activities [5].

Numerical Error: This error is introduced when the continuous mathematical model is transformed into a discrete set of equations that a computer can solve. It is the error generated by the computational method itself. Key sources include discretization error (from representing continuous space/time on a finite grid), iterative convergence error (from stopping an iterative solver too soon), and round-off error (from the finite precision of computer arithmetic) [7] [9] [8]. The process of identifying and quantifying these errors is known as verification [5].

The diagram below illustrates how these errors fit into the complete chain from a physical biological system to a computed result.

The chain of errors from a physical system to a computational result. Modeling error arises when creating the mathematical abstraction, while numerical and round-off errors occur during the computational solving process. Adapted from the concept of the "chain of errors" [8].

A Side-by-Side Comparison of Numerical and Modeling Errors

The following table summarizes the core characteristics that distinguish these two fundamental error types.

| Feature | Numerical Error | Modeling Error |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Question | Are we solving the equations correctly? (Verification) [5] | Are we solving the correct equations? (Validation) [5] |

| Primary Origin | Discretization and computational solution process [7] [9] | Incomplete knowledge or simplification of the biological system [6] [8] |

| Relation to Solution | Can be reduced by improving computational parameters (e.g., finer mesh, smaller time-step) [7] | Generally unaffected by computational improvements; requires changes to the model itself [6] |

| Key Subtypes | Discretization, Iterative Convergence, Round-off Error [7] | Physical Approximation, Physical Modeling, Geometry Modeling Error [7] [8] |

| Analysis Methods | Grid convergence studies, iterative residual monitoring [7] | Validation against high-quality experimental data, sensitivity analysis [10] [5] |

Deep Dive: Numerical Error Subtypes

Numerical errors can be systematically categorized and quantified. The table below expands on the primary subtypes.

| Error Subtype | Description | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Discretization Error | Error from representing continuous PDEs as algebraic expressions on a discrete grid or mesh [7]. | Grid Convergence Studies: Refining the spatial mesh and temporal time-step until the solution shows minimal change [7]. |

| Local Truncation Error | The error committed in a single step of a numerical method by truncating a series approximation (e.g., Taylor series) [9]. | Using numerical methods with a higher order of accuracy, which causes the error to decrease faster as the step size is reduced [9]. |

| Iterative Convergence Error | Error from stopping an iterative solver (for a linear or nonlinear system) before the exact discrete solution is reached [7]. | Iterating until key solution residuals and outputs change by a negligibly small tolerance [7]. |

| Round-off Error | Error from the finite-precision representation of floating-point numbers in computer arithmetic [7] [11]. | Using higher-precision arithmetic (e.g., 64-bit double precision) and avoiding poorly-conditioned operations [7] [11]. |

Deep Dive: Modeling Error Subtypes

Modeling errors are often more insidious as they reflect the fundamental assumptions of the model.

| Error Subtype | Description | Example in Biological Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Approximation Error | Deliberate simplifications of the full physical or biological description for convenience or computational efficiency [7] [8]. | Modeling a fluid flow as inviscid when viscous effects are small but non-zero; assuming a tissue is a single-phase solid when it is a porous, fluid-saturated material [8]. |

| Physical Modeling Error | Errors due to an incomplete understanding of the phenomenon or uncertainty in model parameters [7] [8]. | Using an incorrect reaction rate in a kinetic model of a signaling pathway; applying a linear model to a nonlinear biological process [6] [10]. |

| Geometry Modeling Error | Inaccuracies in the representation of the system's physical geometry [7]. | Using an idealized cylindrical vessel instead of a patient-specific, tortuous artery in a hemodynamic simulation. |

Experimental Protocols for Error Quantification

A rigorous V&V process requires standardized experimental and computational protocols to quantify both types of error.

Protocol for Quantifying Numerical (Discretization) Error

The most recognized method for quantifying spatial discretization error is the Grid Convergence Index (GCI) method, based on Richardson extrapolation.

- Generate a Series of Meshes: Create at least three geometrically similar computational grids with a systematic refinement ratio ( r ) (e.g., ( r = \sqrt{2} ) for a doubling of the number of grid elements in a 3D simulation). The grids should be as free of artifacts as possible.

- Compute Key Solutions: On each grid, compute the value of a key Quantity of Interest (QoI), such as the peak stress in a bone implant or the average velocity in a vessel. Denote these solutions as ( f1 ) (finest grid), ( f2 ), and ( f_3 ) (coarsest grid).

- Calculate Apparent Order: The observed convergence order ( p ) can be calculated using: ( p = \frac{1}{\ln(r{21})} \left| \ln \left| \frac{f3 - f2}{f2 - f1} \right| + q(p) \right| ), where ( r{21} ) is the refinement ratio between medium and fine grids, and ( q(p) ) is a term that can be solved iteratively [7].

- Extrapolate and Compute GCI: Use the observed order ( p ) to compute an extrapolated value ( f_{ext} ) and then the GCI for the fine grid solution, which provides an error band. The detailed equations for this step are standardized and available in references like the ASME V&V 20 standard [5].

Protocol for Quantifying and Correcting Modeling Error

The Dynamic Elastic-Net method is a powerful, data-driven approach for identifying and correcting modeling errors in systems of Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs), common in modeling biological networks [6].

- Define the Nominal Model: Start with the preliminary ODE model: ( \frac{d\tilde{x}}{dt} = \tilde{f}(\tilde{x}, u, t) ), where ( \tilde{x} ) represents the state variables (e.g., protein concentrations) and ( u ) is a known input.

- Formulate the Observer System: Create a copy of the system that includes a hidden input ( \hat{w}(t) ) to represent the model error: ( \frac{d\hat{x}}{dt} = \tilde{f}(\hat{x}, u, t) + \hat{w}(t) ).

- Solve the Optimal Control Problem: Estimate the error signal ( \hat{w}(t) ) by minimizing an error functional ( J[\hat{w}] ) that balances the fit to the experimental data ( y(ti) ) with a regularization term that promotes a sparse solution. This functional is often of the form: ( J[\hat{w}] = \sum{i} \left\| y(ti) - h(\hat{x}(ti)) \right\|^2 + R(\hat{w}) ), where ( R(\hat{w}) ) is the regularization term [6].

- Analyze the Sparse Error Signal: The resulting estimate ( \hat{w}(t) ) will be non-zero primarily for the state variables and time periods most affected by model error, directly pointing to flaws in the nominal model structure.

- Reconstruct the True System State: Use the corrected model to obtain an unbiased estimate ( \hat{x}(t) ) of the true system state, which is valuable when not all states can be measured experimentally [6].

Workflow for the Dynamic Elastic-Net method, a protocol for identifying and correcting modeling errors in biological ODE models through inverse modeling and sparse regularization [6].

Case Study: JAK-STAT Signaling Pathway

The JAK-STAT signaling pathway, crucial in cellular responses to cytokines, provides a clear example where modeling error can be diagnosed and addressed.

Experimental Setup and Model

- Biological System: Erythropoietin receptor-mediated phosphorylation and nuclear transport of STAT5 in cells [6].

- Nominal ODE Model: A 4-state variable model (( \text{STAT5}u, \text{STAT5}m, \text{STAT5}d, \text{STAT5}n )) describing the phosphorylation, dimerization, and nuclear transport process [6].

- Experimental Data: Time-course measurements of phosphorylated and total cytoplasmic STAT5, obtained via techniques like flow cytometry or Western blotting [6].

- Observed Discrepancy: Despite parameter optimization, a systematic mismatch persisted between the nominal model's prediction and the experimental data, indicating a significant modeling error [6].

Application of the Dynamic Elastic-Net

Researchers applied the dynamic elastic-net protocol to this system. The method successfully [6]:

- Reconstructed the error signal ( \hat{w}(t) ), showing when and on which state variables the model was failing.

- Identified the target variables of the model error, pointing to specific processes (e.g., a missed feedback mechanism or incorrect transport rate) within the JAK-STAT pathway that were inaccurately modeled.

- Provided a corrected state estimate, allowing for a more accurate reconstruction of the true dynamic state of the system, even with the imperfect nominal model.

This case demonstrates how distinguishing and explicitly quantifying modeling error provides actionable insights for model improvement and more reliable biological interpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Computational Tools

| Item / Solution | Function in Error Analysis |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Experimental Data | Serves as the ground truth for model validation and for quantifying modeling error [6] [10]. |

| BrdU (Bromodeoxyuridine) | A thymidine analog used in cell proliferation assays; its incorporation into DNA provides quantitative data for fitting and validating cell cycle models [10]. |

| MATLAB / Python (with SciPy) | Programming environments for implementing inverse modeling, performing nonlinear least-squares fitting, and running numerical error analyses [10] [12]. |

| Levenberg-Marquardt Algorithm | A standard numerical optimization algorithm for solving nonlinear least-squares problems, crucial for parameter estimation and inverse modeling [10]. |

| Monte Carlo Simulation | A computational technique used to generate synthetic data sets with known noise properties, enabling estimation of confidence intervals for fitted parameters (i.e., quantifying error in the inverse modeling process) [10]. |

| 5-Undecynoic acid, 4-oxo- | 5-Undecynoic acid, 4-oxo-, CAS:61307-46-8, MF:C11H16O3, MW:196.24 g/mol |

| 7-Methyloct-2-YN-1-OL | 7-Methyloct-2-yn-1-ol |

The journey toward credible and predictive computational models in biology demands a disciplined separation between numerical error and modeling error. Numerical error, addressed through verification, is a measure of how well our computers solve the given equations. Modeling error, addressed through validation, is a measure of how well those equations represent reality. By employing the structured protocols and comparisons outlined in this guide—such as grid convergence studies for numerical error and the dynamic elastic-net for modeling error—researchers can not only quantify the uncertainty in their simulations but also pinpoint its root cause. This critical distinction is the foundation for building more reliable models of biological systems, ultimately accelerating the path from in-silico discovery to clinical application in drug development.

In computational biomechanics, models are developed to simulate the mechanical behavior of biological systems, from entire organs down to cellular processes. The credibility of these models is paramount, especially when they inform clinical decisions or drug development processes. Verification and Validation (V&V) constitute a formal framework for establishing this credibility. Verification is the process of determining that a computational model accurately represents the underlying mathematical model and its solution ("solving the equations right"). In contrast, Validation is the process of determining the degree to which a model is an accurate representation of the real world from the perspective of its intended uses ("solving the right equations") [13].

The V&V process flow systematically guides analysts from a physical system of interest to a validated computational model capable of providing predictive insights. This process is not merely a final check but an integral part of the entire model development lifecycle. For researchers and drug development professionals, implementing a rigorous V&V process is essential for peer acceptance, regulatory approval, and ultimately, the translation of computational models into tools that can advance medicine and biology [13]. With the growing adoption of model-informed drug development and the use of in-silico trials, the ASME V&V 40 standard has emerged as a risk-based framework for establishing model credibility, even finding application beyond medical devices in biopharmaceutical manufacturing [14].

The V&V Process Flow: A Step-by-Step Guide

The journey from a physical system to a validated computational model follows a structured pathway. The entire V&V procedure begins with the physical system of interest and ends with the construction of a credible computational model to predict the reality of interest [13]. The flowchart below illustrates this comprehensive workflow.

Stages of the V&V Process Flow

Physical System to Conceptual Model: The process initiates with the physical system of interest (e.g., a vascular tissue, a bone joint, or a cellular process). Through observation and abstraction, a conceptual model is developed. This involves defining the key components, relevant physics, and the scope of the problem, while acknowledging inherent uncertainties due to a lack of knowledge or natural biological variation [13].

Conceptual Model to Mathematical Model: The conceptual description is translated into a mathematical model, consisting of governing equations (e.g., equations for solid mechanics, fluid dynamics, or reaction-diffusion), boundary conditions, and initial conditions. Assumptions and approximations are inevitable at this stage, leading to modeling errors [13].

Mathematical Model to Computational Model: The mathematical equations are implemented into a computational framework, typically via discretization (e.g., using the Finite Element Method). This step introduces numerical errors, such as discretization error and iterative convergence error [13]. The resulting software is the computational model.

Code Verification: This step asks, "Are we solving the equations right?" [13] It ensures that the governing equations are implemented correctly in the software, without programming mistakes. Techniques include the method of manufactured solutions and order-of-accuracy tests [15]. This is a check for acknowledged errors (like programming bugs) and is distinct from validation [13].

Solution Verification: This process assesses the numerical accuracy of the computed solution for a specific problem. It quantifies numerical errors like discretization error (by performing mesh convergence studies) and iterative error [15]. The goal is to estimate the uncertainty in the solution due to these numerical approximations.

Model Validation: This critical step asks, "Are we solving the right equations?" [13] It assesses the modeling accuracy by comparing computational predictions with experimental data acquired from the physical system or a representative prototype [13]. A successful validation demonstrates that the model can accurately replicate reality within the intended context of use. Discrepancies often require a return to the conceptual or mathematical model to refine assumptions.

Uncertainty Quantification and Sensitivity Analysis

Interwoven throughout the V&V process is Uncertainty Quantification (UQ). UQ characterizes the effects of input uncertainties (e.g., in material properties or boundary conditions) on model outputs [15]. A related activity, Sensitivity Analysis (SA), identifies which input parameters contribute most to the output uncertainty. This helps prioritize efforts in model refinement and experimental data collection [13] [15]. UQ workflows involve defining quantities of interest, identifying sources of uncertainty, estimating input uncertainties, propagating them through the model (e.g., via Monte Carlo methods), and analyzing the results [15].

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

A robust validation plan requires high-quality, well-controlled experimental data for comparison with computational predictions. The following example from vascular biomechanics illustrates a detailed validation protocol.

Detailed Protocol: Experimental Validation of a Vascular Tissue Model

This protocol, adapted from a study comparing 3D strain fields in arterial tissue, outlines the key steps for generating experimental data to validate a finite element (FE) model [16].

Sample Preparation:

- Source: Porcine common carotid artery samples are acquired from animals 6-9 months of age.

- Preparation: Frozen specimens are thawed, and residual connective tissue is carefully removed.

- Mounting: A 35 mm section is excised and mounted onto a custom biaxial testing machine via barb fittings.

Equipment and Setup:

- Mechanical Testing: A computer-controlled biaxial testing system is used, which applies controlled axial force and internal pressure.

- Simultaneous Imaging: An Intravascular Ultrasound (IVUS) catheter is inserted into the vessel lumen, allowing for simultaneous mechanical testing and imaging. The system is equipped with a physiological bath (typically PBS at 37°C) to maintain tissue viability.

Experimental Procedure:

- Pre-conditioning: The vessel specimen undergoes cyclic mechanical loading (e.g., pressurization from 0 to 140 mmHg for 10 cycles) to achieve a repeatable mechanical state.

- Data Acquisition: The vessel is subjected to a defined pressure-loading protocol (e.g., 0 to 140 mmHg). IVUS image data is acquired at multiple axial positions (e.g., 15 slices) and at discrete pressure levels across the loading range.

- Strain Derivation: Experimental strains are derived from the IVUS image data across load states using a deformable image registration technique (e.g., "warping" analysis). This provides a 3D experimental strain field for comparison.

Computational Simulation:

- Model Construction: A 3D FE model of the artery is constructed directly from the IVUS image data acquired at a reference pressure state.

- Material Properties: Material parameters are often personalized by calibrating a constitutive model (e.g., an isotropic neo-Hookean model) to the experimental pressure-diameter data.

- Boundary Conditions: The FE model replicates the experimental boundary conditions (applied pressure and axial stretch).

- Analysis: The FE model is analyzed to predict the 3D strain field throughout the vessel wall.

Validation Comparison:

- Data Extraction: Model-predicted strains are extracted from the FE simulation at locations corresponding to the experimental measurements.

- Comparison Tiers: Strains are compared at multiple spatial evaluation tiers: slice-to-slice, circumferentially, and across transmural levels (from lumen to outer wall).

- Accuracy Assessment: The agreement between FE-predicted and experimentally-derived strains (e.g., circumferential, εₜₜ) is quantified using metrics like the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) [16].

Quantitative Comparisons and Data Presentation

The core of model validation is the quantitative comparison between computational predictions and experimental data. The table below summarizes typical outcomes from a vascular strain validation study, demonstrating the level of agreement that can be achieved.

Table 1: Comparison of Finite Element (FE) Predicted vs. Experimentally Derived Strains in Arterial Tissue under Physiologic Loading (Systolic Pressure) [16]

| Analysis Tier | Strain Component | FE Prediction (Mean ± SD) | Experimental Data (Mean ± SD) | Agreement (RMSE) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slice-Level | Circumferential (εₜₜ) | 0.110 ± 0.050 | 0.105 ± 0.049 | 0.032 | Good agreement across axial slices |

| Transmural (Inner Wall) | Circumferential (εₜₜ) | 0.135 ± 0.061 | 0.129 ± 0.060 | 0.039 | Higher strain at lumen surface |

| Transmural (Outer Wall) | Circumferential (εₜₜ) | 0.085 ± 0.038 | 0.081 ± 0.037 | 0.025 | Lower strain at outer wall |

The data shows that a carefully developed and validated model can bound experimental data and achieve close agreement, with RMSE values an order of magnitude smaller than the measured strain values. This non-linear mechanical behavior, where the model's predictions closely follow the experimental trends across the loading range, provides strong evidence for the model's descriptive and predictive capabilities [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Building and validating a credible computational model in biomechanics relies on a suite of specialized tools, both computational and experimental. The following table details key resources referenced in the featured studies.

Table 2: Key Research Tools for Computational Biomechanics V&V

| Tool / Reagent | Function in V&V Process | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Finite Element (FE) Software | Platform for implementing and solving the computational model. | Solving the discretized governing equations for solid mechanics (e.g., arterial deformation) [16]. |

| Custom Biaxial Testing System | Applies controlled multi-axial mechanical loads to biological specimens. | Generating experimental stress-strain data and enabling simultaneous imaging under physiologic loading [16]. |

| Intravascular Ultrasound (IVUS) | Provides cross-sectional, time-resolved images of vessel geometry under load. | Capturing internal vessel geometry and deformation for model geometry construction and experimental strain derivation [16]. |

| Deformable Image Registration | Computes full-field deformations by tracking features between images. | Deriving experimental 3D strain fields from IVUS image sequences for direct comparison with FE results [16]. |

| ASME V&V 40 Standard | Provides a risk-based framework for establishing model credibility. | Guiding the level of V&V rigor needed for a model's specific Context of Use, e.g., in medical device evaluation [14]. |

| Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) Tools | Propagates input uncertainties to quantify their impact on model outputs. | Assessing confidence in predictions using methods like Monte Carlo simulation or sensitivity analysis [15]. |

| 3-(Bromomethyl)selenophene | 3-(Bromomethyl)selenophene|Research Chemical | 3-(Bromomethyl)selenophene is a key synthetic intermediate for research applications in organic electronics and materials science. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 10-Hydroxydec-6-en-2-one | 10-Hydroxydec-6-en-2-one, CAS:61448-23-5, MF:C10H18O2, MW:170.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The V&V process flow provides an indispensable roadmap for transforming a physical biological system into a credible, validated computational model. This structured journey—from conceptualization and mathematical formulation through code and solution verification to final validation against experimental data—ensures that models are both technically correct and meaningful representations of reality. For researchers and drug development professionals, rigorously applying this framework is not an optional extra but a fundamental requirement. It is the key to generating reliable, peer-accepted results that can safely inform critical decisions in drug development, medical device design, and ultimately, patient care. As the field advances, the integration of robust Uncertainty Quantification and adherence to standards like ASME V&V 40 will further solidify the role of computational biomechanics as a trustworthy pillar of biomedical innovation.

In computational biomechanics, Verification and Validation (V&V) represent a systematic framework for establishing model credibility. Verification is defined as "the process of determining that a computational model accurately represents the underlying mathematical model and its solution," while validation is "the process of determining the degree to which a model is an accurate representation of the real world from the perspective of the intended uses of the model" [1]. Succinctly, verification ensures you are "solving the equations right" (mathematics), and validation ensures you are "solving the right equations" (physics) [1]. This distinction is not merely academic; it forms the foundational pillar for credible simulation-based research and its translation into clinical practice.

The non-negotiable status of V&V stems from the escalating role of computational models in basic science and patient-specific clinical applications. In basic science, models simulate the mechanical behavior of tissues to supplement experimental investigations and define structure-function relationships [1]. In clinical applications, they are increasingly used for diagnosis and evaluation of targeted treatments [1]. The emergence of in-silico clinical trials, which use individualized computer simulations in the regulatory evaluation of medical devices, further elevates the stakes [17]. When model predictions inform scientific conclusions or clinical decisions, a rigorous and defensible V&V process is paramount. Without it, results can be precise yet misleading, potentially derailing research pathways or, worse, adversely impacting patient outcomes [18].

Comparative Analysis of V&V Approaches

The implementation of V&V is not a one-size-fits-all process. It is guided by the model's intended use and the associated risk of an incorrect prediction. The ASME V&V 40 standard provides a risk-informed framework for establishing credibility requirements, which has become a key enabler for regulatory submissions [19]. The following tables compare traditional and emerging V&V methodologies, highlighting their applications, advantages, and limitations.

Table 1: Comparison of V&V Statistical Methods for Novel Digital Measures

| Statistical Method | Primary Application | Performance Measures | Key Findings from Real-World Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) | Initial assessment of the relationship between a digital measure and a reference measure [20]. | Magnitude of the correlation coefficient [20]. | Serves as a baseline comparison; often weaker than other methods [20]. |

| Simple Linear Regression (SLR) | Modeling the linear relationship between a single digital measure and a single reference measure [20]. | R² statistic [20]. | Provides a basic measure of shared variance but may be overly simplistic [20]. |

| Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) | Modeling the relationship between digital measures and combinations of reference measures [20]. | Adjusted R² statistic [20]. | Accounts for multiple variables, but may not capture latent constructs effectively [20]. |

| Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) | Assessing the relationship between a novel digital measure and a clinical outcome assessment (COA) reference measure when direct correspondence is lacking [20]. | Factor correlations and model fit statistics [20]. | Exhibited acceptable fit in most models and estimated stronger correlations than PCC, particularly in studies with strong temporal and construct coherence [20]. |

Table 2: Traditional Physical Testing vs. In-Silico Trial Approaches

| Aspect | Traditional Physical Testing | In-Silico Trial Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Product compliance demonstration [21]. | Simulation model validation and virtual performance assessment [21]. |

| Resource Requirements | High costs and long durations (e.g., a comparative trial took ~4 years) [17]. | Significant time and cost savings (e.g., a similar in-silico trial took 1.75 years) [17]. |

| Regulatory Pathway | Often requires clinical evaluation, though many AI-enabled devices are cleared via 510(k) without prospective human testing [22]. | Emerging pathway; credibility must be established via frameworks like ASME V&V 40 [19]. |

| Key Challenges | Ethical implications, patient recruitment, high costs [17]. | Technological limitations, unmet need for regulatory guidance, need for model credibility [17]. |

| Inherent Risks | Recalls concentrated early after clearance, often linked to limited pre-market clinical evaluation [22]. | Potential for uncontrolled risks if VVUQ activities are limited due to perceived cost [21]. |

Essential V&V Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The V&V Process Workflow

A standardized V&V workflow is critical for building model credibility. The process must begin with verification and then proceed to validation, thereby separating errors in model implementation from uncertainties in model formulation [1]. The following diagram illustrates the foundational workflow of the V&V process.

Core Verification Protocols

3.2.1 Code and Calculation Verification Verification consists of two interconnected activities: code verification and calculation verification [1]. Code verification ensures the computational model correctly implements the underlying mathematical model and its solution algorithms. This is typically achieved by comparing simulation results to problems with known analytical solutions. For example, a constitutive model implementation can be verified by showing it predicts stresses within 3% of an analytical solution for a simple loading case like equibiaxial stretch [1]. Calculation verification, also known as solution verification, focuses on quantifying numerical errors, such as those arising from the discretization of the geometry and time.

3.2.2 Mesh Convergence Studies A cornerstone of calculation verification is the mesh convergence study. This process involves progressively refining the computational mesh (increasing the number of elements) until the solution output (e.g., stress at a critical point) changes by an acceptably small amount. A common benchmark in biomechanics is to refine the mesh until the change in the solution is less than 5% [1]. An incomplete mesh convergence study risks a solution that is artificially too "stiff" [1]. Systematic mesh refinement is equally critical on unstructured meshes, as misleading results can arise if refinement is not applied systematically [19].

Core Validation Protocols

3.3.1 Validation Experiments and Metrics Validation is the process of determining how well the computational model represents reality by comparing its predictions to experimental data specifically designed for validation [1]. The choice of an appropriate validation metric is crucial. For scalar quantities, these can be deterministic (e.g., percent difference) or probabilistic (e.g., area metric, Z metric) [21]. For time-series data (waveforms), specialized metrics for comparing signals are required [21]. The entire validation process, from planning to execution, requires close collaboration between simulation experts and experimentalists [21].

3.3.2 Uncertainty Quantification and Sensitivity Analysis Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) is the process of characterizing and propagating uncertainties in model inputs (e.g., material properties, boundary conditions) to understand their impact on the simulation outputs [21]. UQ distinguishes between aleatory uncertainty (inherent randomness) and epistemic uncertainty (lack of knowledge) [21]. A critical component of UQ is sensitivity analysis, which scales the relative importance of model inputs on the results [1]. This helps investigators target critical parameters for more precise measurement and understand which inputs have the largest effect on prediction variability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for V&V in Computational Biomechanics

| Tool or Resource | Category | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| ASME V&V 40 Standard | Credibility Framework | Provides a risk-based framework for establishing the credibility requirements of a computational model for a specific Context of Use [19]. |

| Open-Source Statistical Web App [17] | Analysis Tool | An open-source R/Shiny application providing a statistical environment for validating virtual cohorts and analyzing in-silico trials. It implements techniques to compare virtual cohorts with real datasets [17]. |

| Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) | Statistical Method | A powerful statistical method for analytical validation, especially when validating novel digital measures against clinical outcome assessments where direct correspondence is lacking [20]. |

| Mesh Generation & Refinement Tools | Pre-processing Software | Tools for creating and systematically refining computational meshes to perform convergence studies for calculation verification [19] [1]. |

| Sensitivity Analysis Software | UQ Software | Tools (often built into simulation packages or as separate libraries) to perform sensitivity analyses and quantify how input uncertainties affect model outputs [1]. |

| Validation Database | Data Resource | A repository of high-quality experimental data specifically designed for model validation, providing benchmarks for comparing simulation results [21]. |

| 5,5-Dichloro-1,3-dioxane | 5,5-Dichloro-1,3-dioxane | 5,5-Dichloro-1,3-dioxane is a chemical building block for antimicrobial and synthetic chemistry research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 3-Butyl-1,3-oxazinan-2-one | 3-Butyl-1,3-oxazinan-2-one | 3-Butyl-1,3-oxazinan-2-one (C8H15NO2) is a versatile oxazinanone scaffold for antimicrobial and anticancer research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Implications for Basic Science and Patient-Specific Outcomes

Implications for Basic Science Research

In basic science, the primary implication of rigorous V&V is the establishment of trustworthy structure-function relationships. Models that have been verified and validated provide a reliable platform for investigating "what-if" scenarios that are difficult, expensive, or ethically challenging to explore experimentally [1]. However, the adoption of V&V is not yet universal. While probabilistic methods and VVUQ were introduced to computational biomechanics decades ago, the community is still in the process of broadly adopting these practices as standard [18]. Failure to implement V&V risks building scientific hypotheses on an unstable computational foundation, potentially leading to erroneous conclusions and wasted research resources.

Implications for Patient-Specific Clinical Outcomes

The stakes for V&V are dramatically higher in the clinical realm, where models are used for patient-specific diagnosis and treatment planning. The consequences of an unvalidated model prediction can directly impact patient welfare [1]. The field is moving toward virtual human twins and in-silico trials, which hold the promise of precision medicine and accelerated device development [23] [17]. For example, the SIMCor project is developing a computational platform for the in-silico development and regulatory approval of cardiovascular implantable devices [17]. The credibility of these tools for clinical decision-making is inextricably linked to a robust V&V process that includes uncertainty quantification [23]. The recall of AI-enabled medical devices, concentrated early after FDA authorization and often associated with limited clinical validation, serves as a stark warning of the real-world implications of inadequate validation [22].

Verification and Validation are non-negotiable pillars of credible computational biomechanics. They are not isolated tasks but an integrated process that begins with the definition of the model's intended use and continues through verification, validation, and uncertainty quantification. As summarized in the workflow below, this process transforms a computational model from a theoretical exercise into a defensible tool for discovery and decision-making.

For basic science, V&V is a matter of scientific integrity, ensuring that computational explorations yield reliable insights. For patient-specific applications, it is a matter of patient safety and efficacy, ensuring that model-based predictions can be trusted to inform clinical decisions. The continued development of standardized frameworks like ASME V&V 40, open-source tools for validation, and a culture that prioritizes model credibility is essential for the future translation of computational biomechanics from the research lab to the clinic.

The field of computational biomechanics increasingly relies on models to understand complex biological systems, from organ function to cell mechanics. The credibility of these models hinges on rigorous Verification and Validation (V&V) processes. Verification ensures that computational models accurately solve their underlying mathematical equations, while validation confirms that these models correctly represent physical reality [13] [24]. The foundational principle is succinctly summarized as: verification is "solving the equations right," and validation is "solving the right equations" [13].

These V&V methodologies did not originate in biomechanics but were instead adapted from more established engineering disciplines. This guide traces the historical migration of V&V frameworks, beginning with their formalization in Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) and computational solid mechanics, to their current application in computational biomechanics, and finally to the emerging risk-based approaches for medical devices.

The Foundational Disciplines: CFD and Solid Mechanics

The development of formal V&V guidelines was pioneered by disciplines with longer histories of computational simulation.

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD)

The CFD community was the first to initiate formal discussions and requirements for V&V [13].

- Early Adoption: The Journal of Fluids Engineering instituted the first journal policy related to V&V in 1986, refusing papers that failed to address truncation error testing and accuracy estimation [13].

- Guideline Development: In 1998, the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) published a comprehensive guide, establishing key V&V concepts and practices [24].

- Seminal Text: Roache's 1998 book provided a foundational text on V&V in CFD, solidifying key concepts for the community [13].

CFD's complex nature— involving strongly coupled non-linear partial differential equations solved in complex geometric domains—made the systematic assessment of errors and uncertainties particularly critical [24].

Computational Solid Mechanics

The computational solid mechanics community developed its V&V guidelines concurrently with the CFD field.

- ASME Leadership: The American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) formed a committee in 1999, leading to the publication of the ASME V&V 10 standard in 2006 [13].

- Standardization: This standard provided the solid mechanics community with a common language, conceptual framework, and implementation guidance for V&V processes [25].

Table 1: Key Early V&V Guidelines in Foundational Engineering Disciplines

| Discipline | Leading Organization | Key Document / Milestone | Publication Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) | AIAA | AIAA Guide (G-077) [13] | 1998 |

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) | - | Roache's Comprehensive Text [13] | 1998 |

| Computational Solid Mechanics | ASME | ASME V&V 10 Standard [13] | 2006 (First Published) |

Migration to Biomechanics and the Current State

The adoption of V&V principles in computational biomechanics followed a predictable but delayed trajectory, mirroring the field's own development.

The Time Lag and Initial Adoption

Computational simulations were used in traditional engineering in the 1950s but only appeared in tissue biomechanics in the early 1970s [13]. This 20-year time lag was reflected in the development of formal V&V policies. However, by the 2000s, active discussions were underway to adapt V&V principles for biological systems [13] [19]. Journals like Annals of Biomedical Engineering began instituting policies requiring modeling studies to "conform to standard modeling practice" [13].

The driving force for this adoption was the need for model credibility. As models grew more complex, analysts had to convince peers, experimentalists, and clinicians that the mathematical equations were implemented correctly, the model accurately represented the underlying physics, and an assessment of error and uncertainty was accounted for in the predictions [13].

Current Applications in Musculoskeletal Modeling

Modern applications show the mature integration of V&V concepts. In musculoskeletal (MSK) modeling of the spine, the ASME V&V framework provides a structured approach to ensure model suitability and credibility for a given "context of use" [26]. These models are used to study muscle recruitment, spinal disorders, and load distribution, relying on validation against often limited experimental data [26].

The modeling workflow now explicitly incorporates V&V, progressing from approach selection to morphological definition, incorporation of body weight, inclusion of passive structures, muscle modeling, kinematics description, and finally, validation through comparisons with literature data [26].

Figure 1: The historical evolution and specialization of V&V guidelines across engineering disciplines, culminating in modern biomedical applications.

The Rise of Risk-Based Frameworks: ASME V&V 40

A significant modern development is the shift towards risk-informed V&V processes, particularly for regulated industries like medical devices.

The ASME V&V 40 Standard

Published in 2018, the ASME V&V 40 standard provides a risk-based framework for establishing the credibility requirements of a computational model [2] [19]. Its core innovation is tying the level of V&V effort required to the model's risk in decision-making.

- Application to Medical Devices: V&V 40 has been a key enabler for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) CDRH framework for using computational modeling and simulation data in regulatory submissions [19].

- Future Developments: The V&V 40 subcommittee continues to extend the framework, with ongoing technical reports on topics like a fictional tibial tray component and patient-specific femur-fracture prediction [19].

In Silico Clinical Trials

The push for higher-stakes applications continues with In Silico Clinical Trials (ISCT), where simulated patients augment or replace real human patients [19]. This application places the highest credibility demands on computational models, requiring extensive V&V to satisfy diverse stakeholders [19].

Table 2: Evolution of Key ASME V&V Standards for Solid and Biomechanics

| Standard | Full Title | Focus / Application Area | Key Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| V&V 10 | Standard for Verification and Validation in Computational Solid Mechanics [2] [25] | General Solid Mechanics | Provided the foundational framework for the solid mechanics community. |

| V&V 40 | Assessing Credibility of Computational Modeling through Verification and Validation: Application to Medical Devices [2] | Medical Devices | Introduced a risk-based approach, crucial for regulatory acceptance. |

| VVUQ 40.1 | An Example of Assessing Model Credibility...: Tibial Tray Component... [19] | Medical Devices (Example) | Provides a detailed, end-to-end example of applying the V&V 40 standard. |

Successful implementation of V&V requires leveraging established resources, standards, and communities.

Key Standards and Frameworks

Researchers should consult and apply the following established guidelines:

- ASME V&V 10-2019: The current standard for verification and validation in computational solid mechanics, providing common language and guidance [25].

- ASME V&V 40-2018: The essential risk-based standard for applications in medical devices and biomedical simulations [2] [19].

- NASA-STD-7009: A comprehensive NASA standard covering requirements, verification, validation, and documentation for aerospace systems, with transferable principles [27].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

A robust validation protocol requires a direct comparison between computational predictions and experimental data.

- Gold Standard Comparison: Validation is a process by which computational predictions are compared to experimental data, which serves as the "gold standard," to assess modeling error [13].

- Combined Protocols: Models should be verified and validated using a combined computational and experimental protocol, integrating methodologies and data from both biomechanics domains [13].

- Uncertainty Quantification: The protocol must account for errors (e.g., discretization, geometry) and uncertainties (e.g., unknown material data, inherent property variation) [13] [2].

Professional Communities

Engagement with professional communities is vital for staying current.

- ASME VVUQ Standards Committees: Committees that develop and maintain V&V standards; participation is free and open to those with relevant expertise [2].

- NAFEMS: A worldwide community dedicated to engineering simulation, with working groups focused on simulation governance and VVUQ [27].

The evolution of V&V guidelines—from their origins in CFD and solid mechanics to their specialized application in biomechanics and medical devices—demonstrates a consistent trend toward greater formalization and risk-aware practices. The historical transition from fundamental concepts like "solving the equations right" to sophisticated, risk-based frameworks like ASME V&V 40 highlights the growing importance of computational model credibility. For researchers in biomechanics and drug development, leveraging these established guidelines is not merely a best practice but a fundamental requirement for producing clinically relevant and scientifically credible results. As the field advances toward in silico clinical trials and personalized medicine, rigorous V&V will remain the cornerstone of trustworthy computational science.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing V&V Across Biomechanical Applications

In computational biomechanics, the credibility of model predictions is paramount, especially when simulations inform basic science or guide clinical decision-making. Verification and Validation (V&V) form the cornerstone of establishing this credibility. Within this framework, verification is defined as "the process of determining that a computational model accurately represents the underlying mathematical model and its solution," while validation determines "the degree to which a model is an accurate representation of the real world" [1]. Succinctly, verification ensures you are "solving the equations right" (mathematics), and validation ensures you are "solving the right equations" (physics) [1]. By definition, verification must precede validation to separate errors stemming from the implementation of the model from uncertainties inherent in the model's formulation itself [1]. This guide focuses on the critical practice of code and calculation verification, objectively comparing its methodologies and providing the experimental protocols for their rigorous application.

Foundational Concepts and Methodologies

Verification is composed of two interconnected categories: code verification and calculation verification [1].

Code verification ensures the mathematical model and its solution algorithms are implemented correctly within the software. It confirms that the underlying governing equations are being solved as intended, free from programming errors, inadequate iterative convergence, and lack of conservation properties [1]. The most rigorous method involves comparison to analytical solutions, which provide an exact benchmark. For complex problems where analytical solutions are unavailable, highly accurate numerical solutions or method of manufactured solutions are employed.

Calculation verification addresses errors arising from the discretization of the problem domain and its subsequent numerical solution. In the Finite Element Method (FEM), this primarily involves characterizing errors from the spatial discretization (the mesh) and the time discretization (time-stepping) [1]. A key process in calculation verification is the mesh convergence study, where the model is solved with progressively refined meshes until the solution changes by an acceptably small amount, indicating that the discretization error has been minimized.

The following diagram illustrates the hierarchical relationship and workflow between these verification concepts and their role within the broader V&V process.

Comparative Analysis of Verification Approaches

The table below summarizes the primary benchmarks and methods used for code and calculation verification, detailing their applications, outputs, and inherent limitations.

Table 1: Comparison of Verification Benchmarks and Methods

| Method Type | Primary Application | Key Measured Outputs | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Solutions [1] | Code Verification | Stress, strain, displacement, flow fields | Provides exact solutions; most rigorous for code verification. | Seldom available for complex, non-linear biomechanics problems. |

| Method of Manufactured Solutions [1] | Code Verification | Any computable quantity from the model | Highly flexible; can be applied to any code and complex PDEs. | Does not verify model physics, only the solution implementation. |

| Mesh Convergence Studies [1] | Calculation Verification | Stress, strain, displacement, pressure | Essential for quantifying discretization error; standard practice in FE. | Computationally expensive; convergence can be difficult to achieve. |

| Numerical Benchmarks [28] | Code & Calculation Verification | Pressure-volume loops, stress, deformation | Provides community-agreed standards for complex physics (e.g., cardiac mechanics). | May not cover all features of a specific model of interest. |

Experimental Protocols for Verification

To ensure reproducibility and rigor, a standardized experimental protocol for verification must be followed. The workflow below details the logical sequence of steps for a comprehensive verification study, from defining the problem to final documentation.

Protocol for Code Verification via Analytical Benchmarks

This protocol is designed to test the fundamental correctness of a computational solver by comparing its results against a known exact solution.

Objective: To verify that the computational implementation accurately solves the underlying mathematical model for a simplified case with a known analytical solution [1].

Methodology:

- Problem Selection: Choose a simplified geometry and set of boundary conditions for which an exact analytical solution to the governing equations exists. An example from literature includes verifying a transversely isotropic hyperelastic constitutive model against an analytical solution for equibiaxial stretch [1].

- Simulation Setup: Implement the identical simplified problem in the computational code.

- Data Extraction & Comparison: Run the simulation and extract the relevant output fields (e.g., stress, strain). Quantitatively compare these results to the analytical solution.

- Error Quantification: Calculate the error, defined as the difference between the computational and analytical results. A common metric is the relative error norm. The code is considered verified for this specific case if errors fall below an acceptable threshold (e.g., <3% in the cited example) [1].

Protocol for Calculation Verification via Mesh Convergence

This protocol assesses and minimizes the numerical error introduced by discretizing the geometry into a finite element mesh.

Objective: To ensure that the solution is independent of the spatial discretization by systematically refining the mesh until the solution changes are negligible [1].

Methodology:

- Baseline Mesh: Create a baseline mesh with an initial element size deemed reasonably fine for the problem.

- Systematic Refinement: Generate a sequence of at least three meshes with progressively smaller element sizes (finer meshes). Global or local refinement techniques can be used.

- Solution Execution: Solve the same boundary value problem on each mesh in the sequence.

- Solution Monitoring: Track one or more key Quantities of Interest (QoIs) across the mesh series. QoIs are often maximum principal stress or strain at a critical location [1].

- Convergence Criterion: Determine that the solution has converged when the relative change in the QoI between successive mesh refinements is below a pre-defined tolerance. A common criterion in biomechanics is a change of <5% [1].

Table 2 provides a hypothetical example of how results from a mesh convergence study are tracked and analyzed.

Table 2: Example Results from a Mesh Convergence Study

| Mesh ID | Number of Elements | Max. Principal Stress (MPa) | Relative Change from Previous Mesh | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse | 15,000 | 48.5 | --- | Not Converged |

| Medium | 45,000 | 52.1 | 7.4% | Not Converged |

| Fine | 120,000 | 53.8 | 3.3% | Converged |

| Extra-Fine | 350,000 | 54.1 | 0.6% | Converged (Overkill) |

Emerging Benchmarking Efforts

The field is moving towards standardized community benchmarks to facilitate direct comparison between different solvers and methodologies. A prominent example is the development of a software benchmark for cardiac elastodynamics, which includes problems for assessing passive and active material behavior, viscous effects, and complex boundary conditions on both monoventricular and biventricular domains [28]. Utilizing such benchmarks is a best practice for demonstrating solver capability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Beyond software, a robust verification pipeline relies on specific computational tools and data. The following table details key "research reagents" essential for conducting verification studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Verification Studies

| Item/Resource | Function in Verification | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Solution Repository | Provides ground-truth data for code verification. | Verifying a hyperelastic material model implementation against a known solution for uniaxial tension. |

| Mesh Generation Software | Creates the sequence of discretized geometries for calculation verification. | Generating coarse, medium, fine, and extra-fine tetrahedral meshes from a patient-specific bone geometry. |

| Robust FE Solver (e.g., FEBio) [29] | Computes the numerical solution to the boundary value problem; must be capable of handling complex biomechanical material models. | Solving a contact problem between two articular cartilage surfaces to predict contact pressure. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides the computational power required for running multiple simulations with high-fidelity models during convergence studies. | Executing a parameter sensitivity analysis or a large-scale 3D fluid-structure interaction simulation. |

| Numerical Benchmark Suite [28] | Offers standardized community-agreed problems for verifying solvers against established results for complex physics. | Testing a new cardiac mechanics solver against a benchmark for active contraction and hemodynamics. |

| 3-Methoxy-2,4-dimethylfuran | 3-Methoxy-2,4-dimethylfuran|High-Purity Reference Standard | 3-Methoxy-2,4-dimethylfuran: A high-purity chemical for research use only (RUO). Explore its applications in organic synthesis and fragrance development. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| GTP gamma-4-azidoanilide | GTP gamma-4-azidoanilide, CAS:60869-76-3, MF:C16H20N9O13P3, MW:639.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Code and calculation verification are non-negotiable prerequisites for building credibility in computational biomechanics. This guide has detailed the methodologies for benchmarking against analytical and numerical solutions, providing a direct comparison of approaches and the experimental protocols for their implementation. As the field advances towards greater clinical integration and the use of digital twins [30], the rigorous application of these verification practices, supported by community-driven benchmarks [28], will be the foundation upon which reliable and impactful computational discoveries are built.

In the field of computational biomechanics, the development of sophisticated models for simulating biological systems has advanced dramatically. However, the predictive value and clinical translation of these models are entirely dependent on rigorous experimental validation across multiple biological scales. Without systematic validation against experimental data, computational models remain unverified mathematical constructs of uncertain biological relevance. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the three principal experimental methodologies—in vitro, in vivo, and ex vivo testing—used to establish the credibility of computational biomechanics models for researchers and drug development professionals.

The choice of validation methodology directly influences the translational potential of computational findings. In vitro systems offer controlled reductionism, in vivo models provide whole-organism complexity, and ex vivo approaches bridge these extremes by maintaining tissue-level biology outside the living organism. Understanding the capabilities, limitations, and appropriate applications of each method is fundamental to building a robust validation framework that can withstand scientific and regulatory scrutiny.

Defining the Methodologies

In Vitro Testing

In vitro (Latin for "within the glass") testing encompasses experiments conducted with biological components isolated from their natural biological context using laboratory equipment such as petri dishes, test tubes, and multi-well plates [31]. These systems typically involve specific biological components such as cells, tissues, or biological molecules isolated from an organism, enabling precise manipulation and isolation of variables for detailed mechanistic studies [31].

- Key Characteristics: Controlled experimental conditions, simplified systems, isolation of specific variables, and suitability for high-throughput screening [31].

- Common Applications: Cell culture studies, cell viability and cytotoxicity assays, enzyme kinetics, biochemical assays, high-throughput drug screening, and molecular biology techniques [31].

In Vivo Testing

In vivo (Latin for "within a living organism") testing involves experiments conducted within intact living organisms, such as animals or humans [31]. These studies provide insights into physiological processes in their natural context, allowing for observation of complex interactions between different organ systems, physiological responses, and overall organismal behavior [31].

- Key Characteristics: Whole organism complexity, natural physiological environment, and observation of systemic effects and ecological interactions [31].

- Common Applications: Animal studies modeling disease progression, pathogenesis, and therapeutic strategies; clinical trials testing safety and efficacy of new drugs in humans; behavioral studies; and toxicology assessments [31].

Ex Vivo Testing

Ex vivo (Latin for "out of the living") testing involves experiments conducted on living tissue or biological systems outside the organism while attempting to maintain tissue structure and function. This approach bridges the gap between highly controlled in vitro systems and complex in vivo environments.

- Key Characteristics: Preservation of tissue-level architecture and cellular interactions, controlled experimental conditions, and limited systemic influences.

- Common Applications: Precision medicine platforms, tissue-specific drug response testing, and mechanistic studies requiring intact tissue microenvironment.

Comparative Analysis of Validation Methods

The table below provides a structured comparison of the three experimental methodologies, highlighting their distinct characteristics, applications, and value for computational model validation.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Experimental Validation Methods

| Aspect | In Vitro | In Vivo | Ex Vivo |

|---|---|---|---|

| System Complexity | Isolated cells or molecules in 2D/3D culture [31] | Whole living organism with all systemic interactions [31] | Living tissue or organs outside the organism [32] |

| Control Over Variables | High precision in manipulation of specific conditions [31] | Limited control due to inherent biological variability [31] | Moderate control while preserving tissue context |

| Physiological Relevance | Low - lacks natural microenvironment and systemic factors [31] | High - intact physiological environment and responses [31] | Intermediate - maintains tissue architecture but not systemic regulation |

| Throughput & Cost | High throughput, relatively low cost [31] | Low throughput, high cost and time requirements [31] | Moderate throughput and cost requirements |

| Ethical Considerations | Minimal ethical concerns [33] | Significant ethical considerations, especially in animal models [33] | Reduced ethical concerns compared to in vivo |

| Primary Validation Role | Initial model parameterization and mechanistic hypothesis testing | Holistic model validation and prediction of systemic outcomes [34] | Tissue-level validation and assessment of emergent tissue behaviors |

| Key Limitations | Unable to replicate complexity of whole organisms [33] | Interspecies differences, ethical constraints, high complexity [35] | Limited lifespan of tissues, absence of systemic regulation |

| Typical Duration | Hours to days | Weeks to months (animals); years (clinical trials) | Hours to weeks |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Ex Vivo 3D Micro-Tumor Validation Platform

A clinically validated ex vivo approach for predicting chemotherapy response in high-grade serous ovarian cancer demonstrates the power of tissue-level validation systems [32].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ex Vivo 3D Micro-Tumor Platform

| Reagent/Component | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Malignant Ascites Samples | Source of patient-derived tumor material preserving native microenvironment [32] |

| Extracellular Matrix Components | Provides 3D support structure for micro-tumor growth and organization |

| Carboplatin/Paclitaxel | Standard of care chemotherapeutic agents for sensitivity testing [32] |

| Culture Medium with Growth Factors | Maintains tissue viability and function during ex vivo testing period |

| High-Content Imaging System | Quantifies morphological features and treatment responses in 3D micro-tumors [32] |

| Immunohistochemistry Markers | Validates preservation of tumor markers (PAX8, WT1) and tissue architecture [32] |

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Sample Acquisition and Processing: Collect malignant ascites from ovarian cancer patients and enrich for micro-tumors using centrifugation and washing steps [32].

- 3D Culture Establishment: Embed micro-tumors in extracellular matrix components in multi-well plates to maintain 3D architecture and viability.

- Therapeutic Exposure: Expose micro-tumors to concentration gradients of standard-of-care chemotherapeutics (carboplatin/paclitaxel) and second-line agents for sensitivity profiling [32].

- High-Content Imaging and Analysis: Capture 3D images of micro-tumors over time using automated microscopy, followed by extraction of morphological features indicating viability and response [32].

- Response Modeling: Train linear regression models to correlate ex vivo sensitivity profiles with clinical CA125 decay rates, changes in tumor size, and progression-free survival [32].

- Clinical Correlation: Establish predictive thresholds for treatment response by correlating ex vivo results with patient outcomes, enabling stratification of responders versus non-responders [32].

This platform achieved a significant correlation (R=0.77) between predicted and clinical CA125 decay rates and correctly stratified patients based on progression-free survival, demonstrating its potential for informing treatment decisions [32].

In Vivo Target Validation Protocol