Metallic vs. Polymeric Biomaterials: A Comprehensive Comparison of Mechanical Properties for Biomedical Applications

This article provides a detailed analysis of the mechanical properties of metallic and polymeric biomaterials, targeting researchers and professionals in biomedical engineering and drug development.

Metallic vs. Polymeric Biomaterials: A Comprehensive Comparison of Mechanical Properties for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a detailed analysis of the mechanical properties of metallic and polymeric biomaterials, targeting researchers and professionals in biomedical engineering and drug development. It explores the fundamental characteristics of both material classes, examines their specific applications in orthopedics, cardiovascular devices, and tissue engineering, addresses key challenges such as stress shielding and degradation control, and offers a comparative validation of their performance. By synthesizing current research and emerging trends, including the use of explainable AI and additive manufacturing for material design, this review serves as a critical resource for the rational selection and development of next-generation biomaterials.

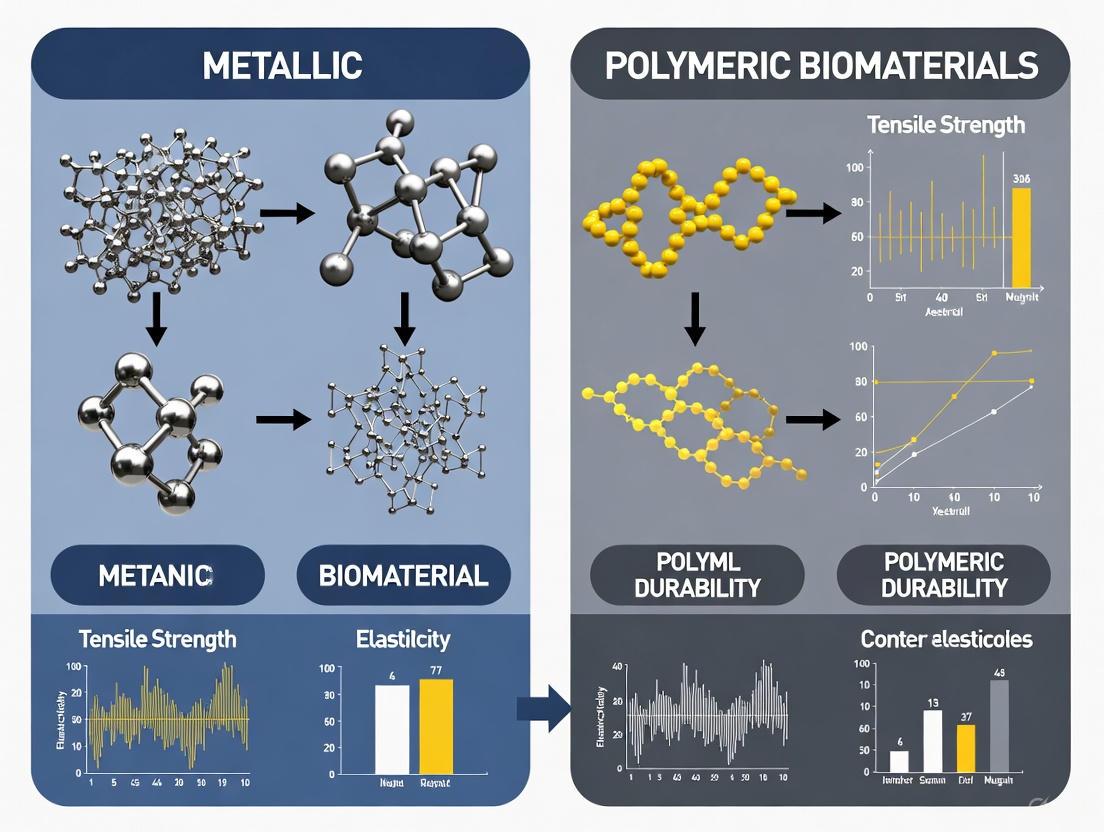

Fundamental Principles: Unraveling the Core Characteristics of Metallic and Polymeric Biomaterials

Biomaterials, traditionally defined as substances engineered to interact with biological systems for a medical purpose, have undergone a revolutionary transformation in both sophistication and application philosophy [1]. The field has evolved from the ancient use of naturally available materials like wood to replace tissues, to a highly interdisciplinary science that seamlessly integrates materials science, biology, and medicine [2]. This evolution is characterized by a fundamental shift from a paradigm of biological inertness to one of active interaction, where modern biomaterials are designed to elicit specific, therapeutic responses from host tissues [2]. The academic foundation of biomaterials has expanded precipitously; in the United States alone, there are now more than 75 departments of biomedical engineering, a dramatic increase from the 12 that existed in 1975, with over 16,000 enrolled students as of 2005 [2]. This growth underscores the critical role biomaterials play in a medical device market that generates approximately $200 billion annually in the U.S. [2]. This article places this evolution within the context of a broader thesis, focusing specifically on the comparison of mechanical properties between two dominant classes of biomaterials: metals and polymers.

Table 1: Historical Evolution of Biomaterials

| Era | Dominant Materials | Design Philosophy | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antiquity to Early 20th Century | Natural Materials (e.g., wood) | Structural replacement, availability | Primitive prosthetics [2] |

| Early to Mid-20th Century | Synthetic Polymers, Metal Alloys, Ceramics | Inertness, mechanical performance | Artificial hips, vascular stents, dental restoratives [2] |

| Late 20th Century to Present | Bioactive and Information-Rich Materials (e.g., composites, smart polymers) | Bioactivity, interaction with host biology, dynamic behavior | Drug-eluting stents, tissue engineering scaffolds, bioactive implants [2] [3] |

Modern Biomaterial Classifications and Properties

Today, biomaterials are broadly classified based on their interaction with host tissue and their chemical composition. The tissue response-based classification categorizes materials as close-to-inert (eliciting minimal tissue response), active (encouraging bonding to surrounding tissue), or degradable/resorbable (incorporated into tissue or dissolved over time) [4]. From a materials science perspective, the primary categories are metals, polymers, ceramics, and composites, each with distinct mechanical and biological properties that dictate their application.

Metallic Biomaterials

Metals are predominantly used for load-bearing applications such as orthopedic and dental implants due to their superior strength, durability, and fatigue resistance [4] [5]. They are typically considered close-to-inert biomaterials. Key challenges for metallic implants include the risk of stress shielding due to a high elastic modulus compared to natural bone, aseptic loosening, and the release of metal ions through corrosion or wear [5] [6]. Consequently, research focuses on developing alloys with lower moduli and enhancing surfaces to improve biointegration.

Table 2: Mechanical Properties of Common Metallic Biomaterials

| Material | Young's Modulus (GPa) | Ultimate Tensile Strength (MPa) | Key Characteristics and Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 316L Stainless Steel | ~200 [7] | ~540 [7] | Cost-effective, good corrosion resistance; removable implants, fracture disks [4] |

| Co-Cr Alloys | ~230 [7] | ~900 [7] | Excellent wear resistance and biocompatibility; artificial hip joints, dental prostheses [4] |

| Commercially Pure Titanium | ~110 [7] | ~240 [7] | Excellent biocompatibility, osseointegration; dental implants [4] |

| Ti-6Al-4V Alloy | ~110 [7] | ~900 [7] | High strength-to-weight ratio, fatigue resistance; bone plates, joint replacements [4] |

| β-type Titanium Alloys | ~40-60 [8] | Varies | Low Young's modulus to reduce stress shielding; next-generation orthopedic implants [8] |

Polymeric Biomaterials

Polymers offer a wide range of properties, from flexible and biodegradable to durable and inert, making them suitable for applications from soft tissue engineering to cardiovascular devices [3] [9]. They can be natural (e.g., collagen, chitosan) or synthetic (e.g., PLA, PCL), and are frequently processed into forms such as hydrogels, porous sponges, and films [3]. A significant advancement is the development of "smart" polymers with self-healing or shape-memory properties, which are highly useful for minimally invasive implantation and creating dynamic tissue environments [3].

Table 3: Mechanical Properties of Common Polymeric Biomaterials

| Material | Young's Modulus | Ultimate Tensile Strength | Key Characteristics and Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | Wide range tunable by composition and MW [3] | Wide range tunable by composition and MW [3] | Biodegradable, used in drug delivery and as stent coatings [4] [3] |

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | Wide range tunable by composition and MW [3] | Wide range tunable by composition and MW [3] | Biodegradable, used in electrospinning for tissue scaffolds [3] |

| Polyurethane (PU) | Varies by formulation | Varies by formulation | Biocompatible, resilient; used in breast implants, cardiac patches, and vascular grafts [4] |

| Acrylic Acid-co-HEMA Graft (Modified ePTFE) | 74-121 MPa [10] | 5-9 MPa [10] | Modified for reduced hydrophobicity; potential use in soft tissue replacement [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Biomaterial Characterization

To objectively compare the performance of metallic and polymeric biomaterials, standardized experimental protocols are essential. The following sections detail key methodologies cited in the literature for evaluating mechanical properties and corrosion behavior.

Static Immersion Test for Metal Release (Metallic Biomaterials)

This in vitro test is designed to quantitatively evaluate the corrosion and metal ion release from metallic biomaterials under simulated physiological conditions [6].

- Objective: To quantify the release of base and alloying elements from metallic biomaterials into various simulated body fluids and understand the effect of solution pH on metal release [6].

- Materials and Specimen Preparation: Specimens of materials like SUS316L stainless steel, Co-Cr-Mo alloy, and Ti-6Al-4V are prepared with a standardized surface finish. They are degreased, rinsed, dried, and sterilized before testing [6].

- Immersion Media: A range of solutions is used to simulate different body environments, including α-medium, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), calf serum, 0.9% sodium chloride, artificial saliva, 1.2% L-cysteine (simulating inflammatory conditions), 1% lactic acid, and 0.01% HCl [6].

- Procedure: Specimens are immersed in the solutions at a consistent surface-area-to-volume ratio and maintained at 37°C for 7 days. The containers are sealed to prevent contamination and evaporation [6].

- Analysis: After the immersion period, the concentrations of released metal ions (e.g., Fe, Cr, Ni, Mo, Co, Ti, Al, V) in the solutions are quantified using analytical techniques like inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). The pH of each solution is also measured post-test [6].

Gamma Irradiation-Induced Grafting for Polymer Modification (Polymeric Biomaterials)

This protocol describes a method to modify the surface of a polymeric biomaterial to alter its physical and mechanical properties, using expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) as an example [10].

- Objective: To graft hydrophilic comonomers onto a hydrophobic polymer surface to improve biocompatibility and measure the resultant changes in mechanical properties [10].

- Materials: Base polymer (e.g., ePTFE film), hydrophilic comonomers (e.g., Acrylic Acid (AA), 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA), N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAAM)), and a gamma irradiation source [10].

- Grafting Procedure:

- The ePTFE substrate is cut into standardized dumbbell shapes and cleaned with hot methanol to remove contaminants.

- The sample is immersed in a solution containing the comonomers and degassed with nitrogen.

- The container is sealed and irradiated at a specified dose (e.g., 0.5 to 2 kGy) using a gamma cell.

- Post-irradiation, the grafted samples are washed with hot methanol and deionized water to remove any ungrafted homopolymer and then dried [10].

- Mechanical Testing: The modified and unmodified samples are subjected to tensile testing using a universal testing machine (e.g., Instron) at a constant crosshead speed. Properties such as Young's modulus, ultimate tensile strength, and elongation at break are evaluated for both dry samples and samples soaked in deionized water (wet condition) [10].

Biomaterial Selection and Testing Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

This table details essential materials and reagents used in the featured experiments and broader biomaterials research, providing researchers with a foundational list for experimental design.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials in Biomaterials Science

| Item | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Simulated Body Fluids (SBFs) | To simulate the chemical environment of the human body for in vitro testing of corrosion, degradation, and bioactivity. | α-medium, PBS, and calf serum used in static immersion tests for metal release [6]. |

| Acrylic Acid (AA) & HEMA | Hydrophilic comonomers used to modify polymer surfaces via grafting. | Grafted onto ePTFE via gamma irradiation to reduce hydrophobicity and alter mechanical properties [10]. |

| Gamma Irradiation Source | Provides high-energy photons to initiate radical formation on polymer chains, enabling surface grafting without multiple chemicals. | Used in the gamma irradiation-induced grafting method for modifying ePTFE [10]. |

| Universal Testing Machine | Measures fundamental mechanical properties of materials, including tensile strength, elongation, and Young's modulus. | Used to characterize both metallic [7] and polymeric [10] biomaterials pre- and post-modification. |

| ICP-MS (Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry) | Highly sensitive analytical technique for quantifying trace levels of metal ions released from biomaterials. | Used to measure concentrations of released ions (Fe, Cr, Ni, Co, Ti, V) after immersion tests [6]. |

| Cyclopropanediazonium | Cyclopropanediazonium Ion Reagent for RUO | Cyclopropanediazonium ions for synthesizing cyclopropylazoarenes and studying radical intermediates. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Butanal, 3,4-dihydroxy- | Butanal, 3,4-dihydroxy-, CAS:34764-22-2, MF:C4H8O3, MW:104.10 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The journey of biomaterials from inert structural replacements to dynamic, bioactive interfaces underscores a profound advancement in medical science. This comparison elucidates a clear dichotomy: metallic biomaterials are unparalleled for applications demanding high strength and fatigue resistance under load, while polymeric biomaterials offer unparalleled versatility, biodegradability, and the potential for sophisticated bio-instructive function. The future of the field lies not only in the continuous refinement of these individual material classes but also in the strategic development of hybrid and composite systems. By harnessing the strengths of both metals and polymers, researchers can create next-generation biomaterials that more perfectly recapitulate the complex mechanical and biological properties of native tissues, thereby improving patient outcomes across a vast spectrum of medical applications.

The selection of materials for biomedical applications, such as implants, stents, and tissue engineering scaffolds, hinges on a fundamental understanding of their intrinsic mechanical properties. These properties are dictated by the material's internal structure, from the type of atomic bonds to the microstructural architecture developed during processing. Within the field of biomaterials research, a central comparison lies between metallic alloys and synthetic polymers, two classes of materials with profoundly different characteristics. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of metallic versus polymeric biomaterials, framing their performance within the context of their atomic bonding and microstructural foundations. It is designed to equip researchers and scientists with the experimental data and methodologies necessary for informed material selection in drug development and medical device innovation.

The global biomaterials market, a domain heavily reliant on these material classes, is projected to grow significantly, underscoring their critical role in advancing human health. These materials are integral to devices that repair or replace physiological functions, with key requirements including biocompatibility, appropriate mechanical properties, and controllable degradation rates for temporary implants. The interplay between a material's chemical structure, its processing history, and its resulting microstructure ultimately determines its success in a biological environment [11].

Atomic and Microstructural Fundamentals

The divergent mechanical behaviors of metals and polymers originate from the nature of their atomic and molecular bonds, which in turn dictate their microstructural organization.

Metallic Biomaterials: The structure of metals is defined by a crystalline lattice held together by metallic bonding, where valence electrons are delocalized and form a "sea" around positively charged ion cores. This bonding allows for plastic deformation without fracture, as planes of atoms can slide past one another via dislocations. This microstructure can be tailored through alloying and thermomechanical processing to control grain size and phase distribution. For instance, in titanium alloys, the stability of the alpha (HCP) and beta (BCC) phases, governed by the Molybdenum Equivalency (MoE), is a primary determinant of mechanical properties like strength and elastic modulus [12]. The quantum mechanical model of atomic structure explains how the arrangement of electrons in atoms leads to these strong, non-directional bonds [13].

Polymeric Biomaterials: Polymers are composed of long-chain molecules based on a carbon backbone, with chains held together by strong covalent bonds along their length and weaker secondary bonds (van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding) between them. Their properties are heavily influenced by the degree of crystallinity and the glass transition temperature (Tg). A semi-crystalline polymer like Poly-l-lactic acid (PLLA) has regions of ordered chains (crystalline domains) embedded in a disordered amorphous matrix. Below its Tg, the amorphous regions are rigid and glassy; above it, they become flexible. The degradation of bioresorbable polymers like PLLA occurs primarily through hydrolysis of the covalent ester bonds in the backbone, a process that progresses from amorphous to crystalline regions [14].

The following diagram illustrates how these fundamental building blocks give rise to the observed material properties.

Comparative Mechanical Properties

The intrinsic differences in bonding and microstructure manifest as distinct mechanical performance profiles. The following tables provide a quantitative comparison of key properties.

Table 1: Comparative Mechanical Properties of Metallic and Polymeric Biomaterials

| Material | Young's Modulus (GPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Flexural Modulus (GPa) | Strength-to-Weight Ratio | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metallic Biomaterials | |||||

| Titanium (Ti-6Al-4V) | 107 [15] | 900-1200 [16] | ~107 [15] | Extremely High (107) [16] | High strength, excellent corrosion resistance, biocompatible. |

| Cobalt-Chromium Alloys | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Very high wear resistance, used in joint replacements. |

| Stainless Steel 316L | 193-200 [15] | 505-700 [16] | ~200 [15] | High (51) [16] | High strength, ductility, cost-effective. |

| Magnesium Alloys | N/A | 180-350 [16] | N/A | Very High (105) [16] | Biodegradable, low radiopacity, fast degradation. |

| Polymeric Biomaterials | |||||

| PLLA (Poly-l-lactic acid) | ~3.5 [14] | 50-70 [14] | 2.5-4.0 [17] [14] | N/A | Biodegradable, transparent, good biocompatibility. |

| PEEK (Polyether ether ketone) | 3.6-4.1 [15] | 90-100 | 3.6-4.1 [15] | N/A | High-performance, radiolucent, excellent chemical resistance. |

| UHMWPE (Ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene) | 0.5-1.5 | 39-48 | ~0.7 [17] | N/A | High wear resistance, used in bearing surfaces. |

| Nylon (PA 6, PA 66) | 2.5-3.5 [15] | 80-90 | 1.0-3.0 [17] | N/A | Tough, wear-resistant. |

Table 2: Clinical Performance and Degradation Profile

| Parameter | Metallic Biomaterials (e.g., Mg Alloys) | Polymeric Biomaterials (e.g., PLLA) |

|---|---|---|

| Biodegradation Mechanism | Corrosion (electrochemical) [14] | Hydrolysis (chain scission) [14] |

| Degradation Rate | Relatively fast (months) [14] | Slow (years); tunable via crystallinity & MW [14] |

| Degradation By-products | Metal ions (e.g., Mg²âº), hydrogen gas [14] | Lactic acid, enters Krebs cycle [14] |

| Radial Strength (in stents) | Good, allows for thinner struts [14] | Requires thicker struts to match metal strength [14] |

| Key Clinical Challenge | Potential for premature loss of mechanical support [14] | Thick struts can affect deliverability and flow [14] |

Experimental Protocols for Characterization

Robust experimental protocols are essential for generating comparable data on material properties. Below are standardized methodologies for key mechanical tests.

Tensile Testing for Young's Modulus (ASTM E8/E8M)

The Young's Modulus, or tensile modulus, is a fundamental property measured under uniaxial tension [15].

- Objective: To determine the stiffness of a material by measuring the relationship between tensile stress and strain within the elastic region.

- Procedure:

- A standardized dog-bone-shaped specimen is gripped in a universal testing machine.

- A controlled, increasing uniaxial tensile load is applied until the specimen yields or fractures.

- The elongation of a specific gauge length is measured using an extensometer.

- Data Analysis: Engineering stress (σ = Force / Original Cross-sectional Area) is plotted against engineering strain (ε = Change in Length / Original Gauge Length). Young's Modulus (E) is calculated as the slope of the initial linear-elastic portion of the stress-strain curve: E = σ / ε [15].

- Standards: ASTM E8/E8M (Standard Test Methods for Tension Testing of Metallic Materials), ISO 6892-1.

Three-Point Bending Test for Flexural Modulus (ASTM D790)

The flexural modulus measures a material's stiffness when subjected to bending forces, which is critical for many load-bearing applications [17] [18].

- Objective: To quantify a material's resistance to bending deformation.

- Procedure:

- A rectangular test bar is placed on two support spans, creating a specified length (L) between them.

- A loading nose applies a force (F) at the midpoint of the supports, deflecting the specimen at a constant rate.

- The test is continued until a set deflection (e.g., 5% as per ASTM D790) or specimen breakage is reached [17].

- Data Analysis: The flexural modulus (Ef) is calculated from the slope (m) of the linear portion of the load-deflection curve using the formula: Ef = (L³m) / (4bd³) where b is the width and d is the thickness of the specimen [17].

- Standards: ASTM D790 (Standard Test Methods for Flexural Properties of Unreinforced and Reinforced Plastics and Electrical Insulating Materials), ISO 178.

The workflow for this standard test is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

A selection of essential materials, testing equipment, and software is critical for research in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Biomaterials Characterization

| Tool / Material | Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Testing Machine | Applies controlled tensile, compressive, or flexural loads to measure mechanical properties. | Performing ASTM D790 three-point bend tests on PLLA scaffolds. |

| Titanium (Ti-6Al-4V) Alloy | A gold-standard metallic biomaterial for orthopedics due to its high strength, low modulus, and biocompatibility. | Control material for comparing mechanical performance of new biodegradable alloys. |

| Poly-l-lactic Acid (PLLA) Resin | A primary biodegradable polymer for fabricating temporary implants and tissue engineering scaffolds. | Studying the effect of molecular weight on the degradation rate and strength retention. |

| Talc Fillers (High Aspect Ratio) | Reinforcing filler for polymers to increase stiffness (flexural modulus). | Improving the load-bearing capacity of polyolefin-based composite biomaterials [17]. |

| Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) | Provides high-resolution imaging of material microstructure, surface topography, and fracture surfaces. | Analyzing the fracture mechanism of a failed tensile specimen or observing polymer porosity. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Measures thermal transitions such as glass transition temperature (Tg) and melting point (Tm). | Determining the crystallinity of a processed PLLA sample, which influences its degradation rate. |

| WebPlotDigitizer Software | Data extraction tool for digitizing data points from published graphs and images in literature. | Compiling mechanical property data from historical publications for meta-analysis [12]. |

| Acridinium, 9,10-dimethyl- | Acridinium, 9,10-dimethyl-|High-Purity Reagent | |

| Butyrophenonhelveticosid | Butyrophenonhelveticosid, CAS:35919-82-5, MF:C39H52O9, MW:664.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The selection of materials for biomedical implants is a critical decision that directly influences the success of medical interventions, from orthopedic implants to vascular scaffolds. The mechanical properties of these materials must be carefully matched to their biological environment to ensure both functionality and biocompatibility. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the key mechanical metrics—strength, modulus, ductility, and hardness—between two principal classes of biomaterials: metals and polymers. Understanding these properties is fundamental for researchers and material scientists developing next-generation medical devices, as mechanical mismatch can lead to complications such as stress shielding, implant failure, or adverse biological responses.

The inherent conflict between various mechanical properties presents a significant challenge in biomaterial design. For instance, high strength and low modulus are often mutually exclusive yet concurrently needed for optimal implant performance [19]. A low Young's modulus helps mitigate stress shielding—a phenomenon where the implant bears most of the load, leading to bone resorption and eventual implant loosening [20] [19]. Simultaneously, high yield strength ensures the implant can withstand physiological loads without permanent deformation [19]. This guide systematically compares metallic and polymeric biomaterials across these critical mechanical parameters, supported by experimental data and testing methodologies relevant to biomedical applications.

Comparative Analysis of Key Mechanical Properties

The mechanical behavior of biomaterials is characterized through standardized testing protocols that evaluate their response to applied forces. The following section provides a detailed comparison of metallic and polymeric biomaterials across four fundamental mechanical properties, supported by quantitative data from recent research.

Table 1: Mechanical Properties of Metallic Biomaterials

| Material Class | Specific Alloy/Type | Young's Modulus (GPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elongation at Break (%) | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Titanium Alloys | Ti-10Nb-5Ta | ~40-50 [20] | >600 [19] | Not Specified | Dental implants |

| Titanium Alloys | Ti-13Nb-5Ta | ~40-50 [20] | >600 [19] | Not Specified | Dental implants |

| Complex Concentrated Alloys (CCAs) | Ti-Zr-Hf-Nb-Ta-Mo-Sn | 40-50 [19] | 600-915 [19] | Not Specified | Orthopedic implants |

| Magnesium Alloys | WE43 | 40-50 [21] | 220-330 [21] | 2-20 [21] | Bioresorbable stents |

| Stainless Steel | 316L | 193 [21] | 668 [21] | 40 [21] | Permanent stents, implants |

| Cobalt-Chromium | Co-Cr | 210 [21] | 235 [21] | 40 [21] | Load-bearing implants |

Table 2: Mechanical Properties of Polymeric Biomaterials

| Material Class | Specific Type | Young's Modulus (GPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elongation at Break (%) | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLLA (Polymer) | Semi-crystalline PLLA | 2-4 [21] [22] | 60-70 [21] | 2-6 [21] | Bioresorbable scaffolds |

| PLA (Polymer) | PLA Ingeo 4043D | 3.6 [22] | ~53 [22] | Not Specified | 3D printed medical devices |

| PLA Composite | PLA + 15wt% DE (Injection Molded) | Up to 4.65 [22] | Reduced vs. pure PLA [22] | Reduced vs. pure PLA [22] | Engineered biomedical constructs |

| PLA Composite | PLA + Metal Particles | 3.5-4 [23] | 50-70 [23] | Not Specified | Tissue engineering scaffolds |

| PDLLA | Amorphous PDLLA | 1-3.5 [21] | 40 [21] | 1-2 [21] | Drug delivery systems |

| PCL | Polycaprolactone | 0.34-0.36 [21] | 23 [21] | >4000 [21] | Soft tissue engineering |

Elastic Modulus: The Stiffness Factor

The elastic modulus (Young's modulus) quantifies a material's stiffness and its ability to resist elastic deformation under applied load. This property is particularly crucial for load-bearing implants to prevent stress shielding, where the implant bears most of the load, leading to bone resorption and eventual implant loosening [20].

Metallic biomaterials typically exhibit high modulus values, with stainless steel and cobalt-chromium alloys ranging from 193-210 GPa [21]. This is significantly higher than human cortical bone (7-30 GPa) [23], creating substantial modulus mismatch. Advanced titanium-based alloys like Ti-Nb-Ta systems and complex concentrated alloys (CCAs) have been developed with lower moduli (40-50 GPa) to better match bone mechanical properties [20] [19].

Polymeric biomaterials generally possess substantially lower modulus values. Semi-crystalline PLLA, used in bioresorbable vascular scaffolds, has a modulus of 2-4 GPa [21], while amorphous PDLLA is even lower (1-3.5 GPa) [21]. The modulus of polymeric materials can be enhanced through reinforcement strategies; for instance, adding 15wt% diatomaceous earth (DE) to semi-crystalline PLA increased its modulus to approximately 4.65 GPa [22].

Strength: Yield and Tensile Strength

Strength represents a material's resistance to permanent deformation and fracture, with yield strength indicating the onset of plastic deformation and tensile strength representing the maximum stress before fracture.

Metallic biomaterials generally offer superior strength properties. Stainless steel 316L exhibits a tensile strength of 668 MPa [21], while newly developed CCAs can achieve yield strengths of 600-915 MPa with lower modulus [19]. Magnesium alloys like WE43 provide intermediate tensile strength (220-330 MPa) [21] with the advantage of biodegradability.

Polymeric biomaterials demonstrate more moderate strength characteristics. Semi-crystalline PLLA used in vascular applications has a tensile strength of 60-70 MPa [21], while commercial PLA grades range between 45-53 MPa [22]. Reinforcement strategies can enhance these properties; metal particle-reinforced PLA composites show improved tensile strength compared to pure PLA [23], though the enhancement is highly dependent on interfacial bonding and filler distribution.

Ductility: Elongation at Break

Ductility, measured as elongation at break, indicates a material's ability to undergo plastic deformation before fracture, which is crucial for processing and certain implant applications like balloon-expandable stents.

Metallic biomaterials typically exhibit good ductility, with stainless steel 316L and cobalt-chromium alloys showing approximately 40% elongation [21]. Magnesium alloys display more variable ductility (2-20%) [21], reflecting their sensitivity to processing conditions and alloy composition.

Polymeric biomaterials show wide variation in ductility. Polycaprolactone (PCL) exhibits exceptional ductility with elongation exceeding 4000% [21], while PLLA is relatively brittle (2-6% elongation) [21]. Amorphous PDLLA shows even lower ductility (1-2% elongation) [21]. The addition of fillers generally reduces ductility; increasing diatomaceous earth content in PLA composites decreases elongation at break while increasing stiffness [22].

Hardness and Other Properties

Hardness represents a material's resistance to localized plastic deformation, which correlates with wear resistance—an important property for articulating joint replacements.

While specific hardness values for all materials weren't provided in the search results, metallic biomaterials generally exhibit superior hardness and wear resistance compared to polymers. The Vickers microhardness of newly developed Ti-Nb-Ta alloys is characterized as part of their comprehensive evaluation [20]. Polymeric biomaterials like PLA have relatively low surface hardness, which can be improved through composite strategies [23].

For bioresorbable materials, degradation behavior becomes a critical additional property. PLLA degrades over >24 months via hydrolysis of ester bonds, progressing from molecular weight reduction to mass loss and eventual resorption [21]. Magnesium alloys degrade more rapidly, typically within 3-12 months [21], with the challenge of controlling corrosion rates to match healing timelines.

Experimental Protocols for Biomaterial Characterization

Tensile Testing for Elastic Modulus and Strength

Tensile testing is the primary method for determining key mechanical properties including elastic modulus, yield strength, tensile strength, and ductility.

Protocol Overview: Tensile tests are performed according to international standards such as ISO 527-1 for plastics [22]. Specimens are machined or molded into standardized dog-bone shapes with specific gauge dimensions. The test involves applying uniaxial tension at a constant crosshead speed until fracture occurs.

Key Methodology Details:

- Specimens are conditioned at standard temperature and humidity before testing

- Strain is measured using extensometers or strain gauges for accurate modulus calculation

- Multiple specimens (typically n≥5) are tested to ensure statistical significance

- Tests are conducted at physiological temperature (37°C) for biomaterials

Data Analysis: The resulting stress-strain curve provides:

- Elastic Modulus: Calculated from the initial linear slope of the curve

- Yield Strength: Determined using the 0.2% offset method

- Tensile Strength: Maximum engineering stress on the curve

- Elongation at Break: Permanent strain at fracture

For composite materials like PLA + diatomaceous earth, tensile testing reveals how filler content affects mechanical properties, showing linear increases in stiffness but reductions in maximum tensile strength and elongation with increasing filler content [22].

Microhardness Testing

Microhardness testing evaluates a material's resistance to localized plastic deformation using diamond indenters under low loads.

Protocol Overview: The Vickers hardness test is commonly used for biomaterials, employing a pyramidal diamond indenter [20].

Key Methodology Details:

- Samples are meticulously polished to a mirror finish using progressively finer abrasives, with final polishing using 0.05 μm alumina powder [20]

- A load of 1000 gf is typically applied for 10 seconds [20]

- Multiple measurements are taken across the sample surface to account for heterogeneity

- For composites, measurements are taken in different phases to characterize reinforcement effects

Data Analysis: The Vickers hardness number (HV) is calculated from the indentation diagonals measured optically. Higher values indicate greater resistance to deformation.

Electrochemical Testing for Corrosion Behavior

Electrochemical testing is crucial for evaluating biomaterial stability in physiological environments, particularly for biodegradable metals and implants.

Protocol Overview: A standard three-electrode electrochemical cell system is used, consisting of a working electrode (test material), reference electrode (typically saturated calomel electrode), and counter electrode (platinum) [20].

Key Methodology Details:

- Tests are conducted in simulated body fluid (SBF) at pH 7.45 and 37°C to mimic physiological conditions [20]

- Multiple techniques are employed:

- Open Circuit Potential (OCP): Measures the steady-state corrosion potential

- Potentiodynamic Polarization: Scans potential to determine corrosion rates

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Evaluates interface characteristics and degradation processes

- Multiple measurements (n≥3) ensure statistical validation [20]

Data Analysis: Corrosion rates are calculated using Tafel extrapolation from polarization curves, while EIS data provides information about surface films and degradation mechanisms.

Advanced Research Tools and Reagent Solutions

Contemporary biomaterials research utilizes specialized reagents, materials, and computational tools to design and characterize novel materials with optimized mechanical and biological properties.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biomaterials Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Poly-L-lactic Acid (PLLA) | Base polymer for bioresorbable scaffolds | Vascular scaffolds, orthopedic implants [21] |

| Ti-xNb-5Ta Alloys | Low-modulus titanium alloy system | Dental implants, load-bearing orthopedic applications [20] |

| Diatomaceous Earth (DE) | Silica-based reinforcement for polymers | PLA composite stiffening agent [22] |

| Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) | In vitro corrosion and degradation testing | Electrochemical evaluation of biomaterials [20] |

| Kroll's Reagent | Metallographic etching for microstructure | Revealing microstructure of titanium alloys [20] |

| Tin(II) Octoate (Sn(Oct)â‚‚) | Catalyst for ring-opening polymerization | PLA synthesis and processing [23] |

| Arc Melting System | Preparation of alloy ingots | Development of novel metallic biomaterials [20] |

Computational Design Tools

Machine learning approaches have emerged as powerful tools for multi-objective optimization of biomaterials. The XGBoost algorithm has been successfully applied to simultaneously predict Young's modulus and yield strength in complex concentrated alloy systems, enabling the design of materials with optimized modulus-strength combinations [19].

Key Features in ML Models:

- Electronic descriptors: Electronegativity, electron affinity, ionization energies

- Atomic descriptors: Atomic radius, size mismatch, lattice distortion energy

- Thermodynamic descriptors: Mixing enthalpy, configurational entropy, melting temperature

- Empirical parameters: VEC, Mo equivalent, bond order (Bo), d-orbital energy level (Md) [19]

These computational tools allow researchers to navigate the complex compositional space of multi-component alloys more efficiently than traditional trial-and-error approaches.

The comparative analysis of metallic and polymeric biomaterials reveals distinct advantages and limitations for each class. Metallic biomaterials generally provide superior strength, hardness, and fatigue resistance, making them suitable for permanent load-bearing applications. Advanced alloys, particularly titanium-based systems and complex concentrated alloys, offer improved modulus matching with biological tissues. Polymeric biomaterials, particularly biodegradable polyesters like PLLA, provide advantages in temporary implants where gradual load transfer to healing tissue is desired, with the additional benefit of eliminating long-term foreign body presence.

The emerging frontier in biomaterials development involves composite approaches and advanced manufacturing techniques. Metal-reinforced PLA composites attempt to bridge the property gap between these material classes [23], while additive manufacturing enables complex geometries tailored to patient-specific anatomy [22] [23]. Computational design tools, particularly multi-objective machine learning models, are accelerating the development of next-generation biomaterials with optimized mechanical-biological performance [19]. As research advances, the integration of material science, computational design, and advanced manufacturing will continue to produce innovative solutions to clinical challenges in regenerative medicine and medical device development.

The performance and longevity of biomedical implants are fundamentally governed by their interactions with the biological environment, primarily through the dual critical axes of biocompatibility and corrosion resistance. These properties determine the host tissue response and the material's structural integrity over time. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this biological interface is essential for selecting and developing next-generation implant materials. This guide provides a objective comparison between metallic and polymeric biomaterials, framing their performance within the broader context of mechanical properties research. It synthesizes current experimental data and methodologies to offer a clear, evidence-based resource for the scientific community.

The imperative for this comparison stems from a fundamental clinical challenge: the mismatch in mechanical properties between implant materials and native human tissue, which can lead to complications such as stress-shielding and implant failure [24]. Furthermore, the degradation profiles of materials—whether the slow, corrosive release of ions from metals or the controlled, enzymatic breakdown of polymers—directly influence their biocompatibility and functional lifespan [25] [26]. This analysis delves into the specific mechanisms, testing protocols, and performance data that define how metallic and polymeric systems navigate this complex interface.

Metallic Biomaterials: Performance and Data

Metallic biomaterials are predominantly used for load-bearing orthopaedic and dental applications due to their superior fatigue resistance, high strength-to-weight ratio, and excellent machinability [24] [27]. However, their performance is critically dependent on resisting corrosion in the harsh physiological environment and mitigating adverse biological reactions to corrosion byproducts.

Corrosion Mechanisms and Biocompatibility

The primary threat to metallic implants is localized corrosion, including pitting and fretting corrosion, which is accelerated by the complex, chloride-rich environment of the human body [27]. This process releases metal ions (e.g., Al, V, Co, Cr) that can provoke toxic responses, inflammatory reactions, and bone resorption, ultimately leading to aseptic loosening [24] [20]. The body's response to wear and corrosion debris often initiates a macrophage-mediated immune response, which can cause bone erosion (osteolysis) around the implant [24]. Therefore, the biocompatibility of metals is intrinsically linked to the stability and protectiveness of their surface passivation films.

Advancements in Alloy Design

Research has pivoted towards developing novel alloys that minimize these risks. Strategies include using non-toxic alloying elements like Nb, Zr, Ta, and Sn, and exploring new alloy systems such as Medium/High Entropy Alloys (M/HEAs) [27]. These designs aim to achieve a lower elastic modulus closer to that of bone to reduce stress shielding, while enhancing corrosion and wear resistance through unique microstructural properties [27] [20].

Table 1: Corrosion Performance of Selected Metallic Biomaterials

| Material | Experimental Environment | Corrosion Rate / Key Metric | Key Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti40Zr40Nb5Ta12Sn3 MEA | Artificial Saliva (AS), Saline Buffer (SB), Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) | Superior corrosion resistance in AS; Metastable pitting in SBF | Passivation film in AS most stable. SBF's complex composition degrades film stability. | [27] |

| Ti-xNb-5Ta Alloys | Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) | Corrosion resistance improves with increasing Nb content. | Higher Nb content promotes stable passive film formation. | [20] |

| Mg-0.3Sr-0.4Mn (SM04) Alloy | In vitro biodegradation | 0.39 mm/year (54% reduction vs. SM0 alloy) | Optimal Mn content refines grains and improves corrosion resistance. | [28] |

Key Experimental Protocols for Metals

Standardized electrochemical tests are crucial for evaluating metallic biomaterials.

- Open Circuit Potential (OCP): Measures the inherent corrosion tendency of the material in a solution over time. An increasing OCP indicates the formation of a stable passivation film [27].

- Potentiodynamic Polarization: Scans through a range of potentials to determine key parameters like corrosion current density and breakdown potential, which quantify corrosion rate and resistance to pitting [27] [20].

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Assesses the protective quality and stability of the passive film on the metal surface by measuring its impedance to a range of AC frequencies [20].

Polymeric Biomaterials: Performance and Data

Polymeric biomaterials offer a distinct set of advantages, primarily their versatility in synthesis, ability to be biodegradable, and the capacity to mimic the properties of natural soft tissues [25]. Their biological interface is defined less by ionic release and more by their degradation products, surface chemistry, and mechanical mismatch.

Biocompatibility and Degradation Profiles

The biocompatibility of polymers is heavily influenced by their origin. Natural polymers (e.g., collagen, chitosan, hyaluronic acid) derive their excellent biocompatibility from their structural similarity to the native extracellular matrix (ECM), which minimizes chronic inflammation and immunological rejection [25]. Their degradation is typically controlled by enzymes [25]. Conversely, synthetic polymers (e.g., PLA, PGA, PCL, PEG) offer superior and tunable mechanical properties and reproducible, controlled degradation rates, but they often lack innate cell adhesion sites and may trigger immune responses, necessitating chemical modification [25].

A key challenge is the mechanical property mismatch between synthetic polymers and natural tissues, which can lead to inadequate load-bearing or adverse tissue responses [29]. Furthermore, the viscoelastic behavior of polymers means their mechanical properties are time-dependent, complicating long-term performance prediction under cyclical physiological loads [29].

Advanced Polymeric Systems

The field is advancing through the development of hybrid natural-synthetic systems, hydrogels with tunable mechanical properties, and nanocomposite polymers [25] [29]. These approaches aim to combine the bioactivity of natural polymers with the mechanical robustness and reproducibility of synthetic ones. For example, hydrogels can be engineered to match the stiffness of various soft tissues, while incorporating nanoparticles can significantly enhance the tensile strength and fracture toughness of polymers for load-bearing applications [25] [29].

Table 2: Mechanical & Biological Performance of Biomedical Polymers

| Polymer Class | Key Properties | Degradation Mechanism | Biocompatibility Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Polymers(e.g., Collagen, Chitosan) | Low mechanical strength, variable batch-to-batch. | Enzyme-controlled degradation in vivo. | Inherently high; mimics native ECM. Low chronic inflammation. |

| Synthetic Polymers(e.g., PLA, PLGA, PCL) | Tunable strength & degradation rate, high reproducibility. | Hydrolysis (controlled by polymer chemistry). | Can lack cell adhesion sites; may require surface modification. |

| Hydrogels(e.g., PEG-based) | Adjustable stiffness & elasticity, high water content. | Often responsive to stimuli (pH, temperature). | Can be designed to be non-immunogenic; excellent for soft tissue mimicry. |

Key Experimental Protocols for Polymers

Mechanical and biological testing for polymers addresses their unique characteristics.

- Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA): Characterizes the viscoelastic behavior of polymers by applying oscillating forces, measuring properties like storage and loss moduli across a range of temperatures or frequencies [29].

- In Vitro Degradation Studies: Polymers are incubated in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or simulated body fluid at 37°C. Mass loss, molecular weight change, and mechanical property retention are tracked over time to predict in vivo performance [25].

- Cell Function Assays: Beyond viability, assays like alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity are used quantitatively (e.g., with p-nitrophenyl phosphate) to assess the material's ability to promote osteogenic differentiation of stem cells, a key marker of bioactivity [28] [20].

Direct Comparison and Discussion

The choice between metallic and polymeric biomaterials is not a matter of superiority, but of application-specific suitability. The core trade-off lies between the high strength and toughness of metals and the tailorable degradation and potential for bioactivity of polymers.

The Stress Shielding Dilemma

A central theme in biomechanics is the elastic modulus mismatch. Metals like CoCrMo and Ti6Al4V have a Young's modulus (~110 GPa and ~110-120 GPa, respectively) significantly higher than human cortical bone (~10-30 GPa) [24] [30]. This disparity causes stress shielding, where the implant bears most of the load, leading to bone resorption and implant loosening [24]. While novel beta titanium alloys can achieve a lower modulus (~40-80 GPa), it remains higher than bone [24] [20]. Polymers, with a wider range of moduli, can be engineered to better match soft tissues, but their strength is often insufficient for major load-bearing bones.

Degradation: Corrosion vs. Controlled Resorption

The degradation pathways are fundamentally different. Metal degradation (corrosion) is an electrochemical process that can release toxic ions and particulate debris, provoking adverse biological reactions [24] [26]. In contrast, biodegradable polymers are designed to resorb through hydrolysis or enzymatic activity, and their degradation products can be metabolized. The ideal biodegradable metal, magnesium, occupies a middle ground, releasing non-toxic Mg²⺠ions that may actually promote bone formation, but controlling its rapid corrosion remains a challenge [28].

Table 3: Direct Comparison of Metallic vs. Polymeric Biomaterials

| Property | Metallic Biomaterials | Polymeric Biomaterials |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Young's Modulus | 40-200 GPa (often much higher than bone) | 0.1 MPa - 10 GPa (wide range, tunable) |

| Primary Degradation Form | Electrochemical Corrosion (ion release) | Hydrolysis/Enzymatic Degradation |

| Key Biocompatibility Concern | Inflammatory response to ions & wear debris | Inflammatory response to degradation products or lack of bioactivity |

| Primary Strength | High tensile & fatigue strength; Fracture toughness | Tunable strength; Good resilience for soft tissues |

| Biological Interaction | Typically bio-inert; surface can be functionalized | Can be designed to be bioactive or bio-instructive |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Biomaterial Interface Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) | In vitro solution mimicking ionic composition of human blood plasma. | Accelerated testing of apatite formation (bioactivity) and corrosion/degradation. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Isotonic buffer with stable pH. | Standard medium for in vitro degradation studies and as a control in biocompatibility tests. |

| Cell Culture Media (e.g., DMEM) | Nutrient-rich medium supporting cell growth. | Used in cytocompatibility assays to culture osteoblasts (e.g., MC3T3-E1) or stem cells (hBMSCs). |

| CCK-8 Assay Kit | Colorimetric kit for quantifying cell viability and proliferation. | Measures the metabolic activity of cells seeded on material extracts or surfaces. |

| p-Nitrophenyl Phosphate (pNPP) | Substrate for alkaline phosphatase (ALP) enzyme. | Used in semi-quantitative analysis of ALP activity, a key marker of osteogenic differentiation. |

| Kroll's Reagent | Etchant for titanium and its alloys. | Used in metallographic preparation to reveal microstructure for optical microscopy. |

| Potentiodynamic Polarization Setup | Standard three-electrode cell (working, reference, counter). | Electrochemical testing to determine corrosion rates and pitting susceptibility. |

| N-Acetylglycyl-D-alanine | N-Acetylglycyl-D-alanine | High-purity N-Acetylglycyl-D-alanine for research applications. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| 6-Methylhept-1-en-3-yne | 6-Methylhept-1-en-3-yne, CAS:28339-57-3, MF:C8H12, MW:108.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The field of biomedical implants is fundamentally defined by a material's relationship with the biological environment over time, creating a clear spectrum from permanent to fully transient devices. On one end, permanent implants are designed from biostable materials such as cobalt-chromium alloys, stainless steels, and certain titanium alloys, which remain in the body indefinitely to provide lifelong structural support for load-bearing applications like joint replacements [24]. These materials prioritize mechanical longevity, corrosion resistance, and biocompatibility over decades of service. Occupying the middle ground, bioactive implants interact with biological systems to promote healing while undergoing minimal degradation themselves; surface-modified metals and certain ceramics fall into this category, enhancing osseointegration through controlled surface interactions without significant bulk degradation [24]. At the far end of the spectrum, fully bioresorbable implants represent the most transformative approach, constructed from materials engineered to safely dissolve after fulfilling their temporary mechanical and biological functions [31]. These transient scaffolds—including magnesium-based alloys, polymers like polylactic acid (PLA) and poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), and emerging hybrid systems—eliminate the need for secondary removal surgeries and can actively promote tissue regeneration by gradually transferring load to healing tissues and releasing bioactive substances during degradation [31] [32].

The fundamental thesis governing material selection in this spectrum revolves around the critical balance between mechanical properties and degradation kinetics. Metallic biomaterials generally provide the structural integrity required for load-bearing applications but have traditionally faced challenges with biodegradability, while polymeric materials offer superior degradation tunability and biological compatibility but often lack the mechanical strength for demanding orthopedic applications [31] [25] [24]. This comparison guide objectively examines the experimental data and performance metrics of metallic versus polymeric biomaterials across this biodegradability spectrum, providing researchers with a structured framework for material selection based on mechanical requirements, degradation timelines, and intended clinical applications.

Material Classes and Their Position on the Biodegradability Spectrum

Metallic Biomaterials

Metallic implants dominate applications requiring high load-bearing capacity and structural integrity, with their biodegradability characteristics varying significantly based on composition.

Permanent Metallic Implants: Traditional orthopedic implants utilize metals prized for their biostability and mechanical performance. Commercially pure titanium and Ti-6Al-4V alloy exhibit excellent corrosion resistance due to a stable surface oxide layer, with Young's modulus values ranging from 110-120 GPa—still significantly higher than cortical bone (10-30 GPa) but lower than other metals [12] [24]. CoCrMo alloys provide exceptional wear resistance necessary for articulating surfaces, with high strength (ultimate tensile strength > 900 MPa) and a Young's modulus of approximately 230 GPa, while stainless steel (316L) offers cost-effective manufacturing with good mechanical properties [24]. The primary limitation of these permanent metallic implants is the stress-shielding effect, where the significant modulus mismatch with bone leads to reduced mechanical stimulation of surrounding tissue, potentially causing bone resorption and implant loosening over time [24].

Biodegradable Metallic Implants: Emerging biodegradable metals represent a paradigm shift toward transient implant technology. Magnesium alloys demonstrate exceptional promise with their bone-like modulus (41-45 GPa), biocompatibility, and ability to completely degrade in physiological environments [31]. Magnesium's degradation rate can be tailored through alloying (with zinc, calcium, or rare earth elements) and processing techniques, creating implants that maintain mechanical integrity during initial bone healing (3-6 months) before gradually dissolving [31]. Similarly, iron and zinc-based alloys offer alternative degradation profiles, with zinc alloys typically degrading slower than magnesium but faster than iron [31]. These materials actively support the healing process during degradation, with in vivo studies showing enhanced osteogenesis and bone formation around degrading magnesium implants compared to inert counterparts [31].

Advanced Metallic Systems: Recent research explores niobium-based alloys as intermediate options, leveraging niobium's excellent corrosion resistance, biocompatibility, and lower elastic modulus (69-103 GPa) compared to traditional titanium alloys [33]. While not fully biodegradable, these alloys address stress-shielding concerns while maintaining long-term stability. Additionally, porous metallic structures created through advanced manufacturing techniques like 3D printing further reduce effective modulus while promoting bone ingrowth [24].

Polymeric Biomaterials

Polymeric biomaterials offer unparalleled versatility in degradation rate tuning and biological functionalization, positioning them predominantly at the biodegradable end of the spectrum.

Synthetic Biodegradable Polymers: This category provides precise control over degradation kinetics and mechanical properties. PLGA stands as the most extensively researched polymer system, with degradation rates controllable from weeks to months by adjusting the lactic to glycolic acid ratio [25] [32]. Polylactic acid (PLA) and polycaprolactone (PCL) offer longer degradation timelines (months to years), with mechanical properties suitable for various applications from sutures to bone fixation devices [25]. The key advantage of synthetic polymers is their reproducible manufacturing and tailorable properties, though they often require surface modification to enhance cell adhesion and may trigger mild inflammatory responses in certain applications [25].

Natural Polymers: Derived from biological sources, natural polymers excel in biological recognition and biocompatibility. Collagen, fibrin, chitosan, and silk fibroin provide innate cell adhesion motifs and enzymatic degradation pathways that closely mimic the natural extracellular matrix [31] [25]. For instance, silk fibroin scaffolds have demonstrated remarkable efficacy in enhancing the proliferation of bone marrow stem cells and chondrocytes in vitro [31]. However, these materials typically exhibit inferior mechanical properties compared to synthetic systems and face challenges with batch-to-batch variability during production [25].

Hybrid and Composite Systems: The most significant advancement in polymeric biomaterials involves creating hybrid natural-synthetic systems that leverage the strengths of both material classes [25]. These composites combine the mechanical robustness and manufacturing consistency of synthetic polymers with the bioactivity and biocompatibility of natural polymers. For example, PLGA-chitosan composites have been developed for nerve guidance conduits, demonstrating enhanced cellular interactions while maintaining structural integrity during the critical healing period [31] [25].

Table 1: Comparative Mechanical Properties of Metallic vs. Polymeric Biomaterials

| Material Class | Specific Examples | Young's Modulus (GPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Degradation Timeline | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permanent Metals | Ti-6Al-4V [24] | 110-125 | 860-900 | Non-degradable | Joint replacements, dental implants |

| CoCrMo Alloy [24] | 200-230 | >900 | Non-degradable | Femoral heads, articulating surfaces | |

| 316L Stainless Steel [24] | 190-200 | 500-700 | Non-degradable | Fracture fixation, temporary devices | |

| Biodegradable Metals | Magnesium Alloys [31] | 41-45 | 250-350 | 3-12 months | Bone fixation, cardiovascular stents |

| Zinc Alloys [31] | 90-110 | 200-300 | 12-24 months | Cardiovascular stents, bone implants | |

| Iron-based Alloys [31] | 180-200 | 300-500 | >24 months | Bone defect scaffolds | |

| Synthetic Polymers | PLGA [25] [32] | 1.5-4.0 | 40-70 | Weeks to months | Drug delivery, tissue scaffolds |

| PLA [25] | 2.5-4.0 | 50-70 | 6 months to 2 years | Bone screws, sutures | |

| PCL [25] | 0.2-0.5 | 20-40 | 2-4 years | Soft tissue engineering | |

| Natural Polymers | Collagen [25] | 0.002-0.05 | 1-10 | Days to weeks | Wound healing, skin regeneration |

| Chitosan [25] | 0.5-2.0 | 20-40 | Weeks to months | Wound dressings, cartilage repair | |

| Silk Fibroin [31] | 5-15 | 50-100 | Months to years | Ligament repair, bone scaffolds |

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Mechanical Performance Under Physiological Conditions

The mechanical compatibility of implant materials with native tissues represents a critical performance metric, particularly for load-bearing applications. Experimental data compiled from extensive studies on Ti-alloys reveals a critical relationship between elastic modulus and β-phase stability, with metastable β-Ti alloys achieving moduli as low as 45-65 GPa—significantly closer to cortical bone (10-30 GPa) than conventional titanium alloys [12]. This reduction in modulus directly addresses the stress-shielding phenomenon, with in vivo studies demonstrating improved bone remodeling around lower modulus implants [24].

For biodegradable materials, the retention of mechanical properties during the degradation process presents the fundamental challenge. Experimental protocols typically involve monitoring mechanical properties of samples immersed in simulated body fluid (SBF) at 37°C over time. Magnesium alloys exhibit the most favorable initial mechanical properties among biodegradable metals, with AZ31 alloy maintaining approximately 80% of its yield strength after 28 days in SBF [31]. However, polymeric systems generally demonstrate more predictable degradation profiles, with PLGA scaffolds showing a linear relationship between molecular weight decrease and strength reduction over 12 weeks in physiological conditions [25].

Table 2: Degradation Characteristics and Biological Response of Biomaterials

| Material Type | Degradation Rate Control | Primary Degradation Byproducts | Tissue Response | Strength Retention During Degradation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnesium Alloys [31] | Composition, processing, coating | Mg(OH)â‚‚, Hâ‚‚ gas | Mild inflammation, enhanced osteogenesis | 60-80% at 4 weeks (varies by alloy) |

| Zinc Alloys [31] | Composition, microstructure | Zn²⺠ions, ZnO | Minimal inflammation, promotes mineralization | >80% at 12 weeks |

| Iron Alloys [31] | Composition, porosity | Fe²âº/Fe³⺠ions, oxides | Minimal inflammation, slow tissue integration | >90% at 24 weeks |

| PLGA [25] [32] | LA:GA ratio, molecular weight | Lactic acid, glycolic acid | Mild to moderate inflammation, predictable healing | 50-70% at 4 weeks (varies by composition) |

| PLA/PCL [25] | Crystallinity, molecular weight | Carboxylic acids, alcohols | Minimal to mild inflammation | 70-90% at 12 weeks |

| Natural Polymers (e.g., Silk) [31] | Crosslinking, structure | Amino acids, peptides | Excellent integration, minimal immune response | Highly variable based on processing |

Advanced Functional Integration

The convergence of material science with biomedical engineering has enabled sophisticated multifunctional implants that combine structural support with therapeutic capabilities. A pioneering example is the fully bioresorbable hybrid opto-electronic neural implant system, which integrates Mo/Si bilayer electrodes for neural recording with PLGA waveguides for optogenetic stimulation [32]. This system exemplifies the potential of transient implants, performing simultaneous electrophysiological monitoring and optical stimulation in mouse models for 2 weeks before complete biodegradation within 8 weeks [32].

The experimental methodology for such advanced systems involves layer-by-layer fabrication using transfer printing and soft lithography techniques, with precise control over material interfaces to prevent delamination during operation [32]. Performance validation includes in vitro degradation monitoring in phosphate-buffered saline at 37°C, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy for electrode functionality, and photoelectric artifact testing to ensure signal fidelity during optical stimulation [32]. In vivo assessment in transgenic mouse models demonstrates the system's capability to record evoked local field potentials while providing optogenetic stimulation, with histological analysis confirming minimal glial scarring and complete absorption of degradation products [32].

Experimental Methodologies for Biomaterial Evaluation

Standardized Testing Protocols

Mechanical Characterization: Standard ASTM protocols govern the mechanical evaluation of biomaterials. Tensile testing (ASTM E8/E8M) determines yield strength, ultimate tensile strength, and elongation at fracture using standardized dog-bone specimens tested at physiological temperature (37°C) in simulated body fluid when assessing biodegradable materials [12]. Compression testing (ASTM E9) evaluates performance under compressive loads relevant to orthopedic applications. Nanoindentation provides localized mechanical property mapping, particularly useful for composite and porous structures [12]. For fatigue assessment, specimens undergo cyclic loading at physiological frequencies (1-5 Hz) in simulated body fluid until failure or reaching 10 million cycles, with results presented as stress-number of cycles (S-N) curves [24].

Degradation Analysis: Immersion testing in simulated body fluid (SBF) at 37°C and pH 7.4 remains the standard for evaluating biodegradation kinetics [31]. Mass loss measurements at regular intervals quantify degradation rates, while solution analysis via inductively coupled plasma spectroscopy tracks ion release profiles. Electrochemical techniques including potentiodynamic polarization and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy provide accelerated corrosion data, with established correlations to actual in vivo performance [31] [33]. Surface characterization pre- and post-degradation using scanning electron microscopy, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, and profilometry documents morphological and compositional changes [33].

Biological Compatibility Assessment: In vitro cytotoxicity testing follows ISO 10993-5 standards, using direct contact and extract methods with fibroblast and osteoblast cell lines [24]. Cell adhesion and proliferation assays quantify cellular response to material surfaces, while specialized differentiation assays (alkaline phosphatase activity, calcium deposition) evaluate osteogenic potential [24]. Animal implantation studies in relevant models (rat femoral condyle, rabbit tibia) provide in vivo degradation and tissue response data, with histological scoring of inflammation, fibrosis, and tissue integration at multiple time points [31] [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Biomaterials Investigation

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Research Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base Materials | Medical-grade Ti-6Al-4V, Mg-Zn-Ca alloys, PLGA (75:25), High-purity collagen | Fundamental implant fabrication | Controlled composition, reproducible properties, documented purity |

| Characterization Reagents | Simulated Body Fluid (SBF), Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), Alamar Blue, MTT assay kits | Degradation studies and biocompatibility screening | Standardized formulations, validated protocols, quantitative output |

| Cell Culture Systems | MC3T3-E1 osteoblast precursor cells, L929 fibroblasts, Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) | In vitro biocompatibility and functionality assessment | Well-characterized response, relevance to implant environment |

| Animal Models | Sprague-Dawley rats, New Zealand White rabbits, Transgenic mice (e.g., Thy-1: ChR2) | In vivo performance and degradation analysis | Established surgical models, predictable healing response |

| Analytical Tools | Scanning Electron Microscopy with EDS, ICP-OES, Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy | Material characterization and degradation monitoring | High sensitivity, quantitative data generation, surface specificity |

| 4-Azido-2-chloroaniline | 4-Azido-2-chloroaniline, CAS:33315-36-5, MF:C6H5ClN4, MW:168.58 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 2-Bromo-1,1-diethoxyoctane | 2-Bromo-1,1-diethoxyoctane, CAS:33861-21-1, MF:C12H25BrO2, MW:281.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Material Selection Framework and Future Directions

The selection between metallic and polymeric biomaterials depends on a balanced consideration of mechanical requirements, degradation timeline, biological functionality, and manufacturing feasibility. The following decision framework visualizes the critical selection pathway for researchers navigating the biodegradability spectrum:

The field of biodegradable implants continues to evolve through several key research frontiers. Hybrid material systems that combine the mechanical advantages of metals with the biodegradability and bioactivity of polymers represent the most promising direction [31] [25]. These include polymer-coated magnesium alloys with controlled degradation profiles and natural-synthetic polymer composites with graded mechanical properties. Advanced manufacturing technologies, particularly 3D and 4D printing, enable patient-specific implants with complex architectures that optimize the balance between mechanical support and biodegradability [31] [24]. Surface functionalization techniques that incorporate bioactive molecules (peptides, growth factors) onto biodegradable scaffolds create implants that actively direct the healing process while gradually transferring load to regenerating tissues [24]. Finally, multifunctional implant systems that combine structural support with sensing, stimulation, and drug delivery capabilities represent the cutting edge of transient medical devices [32].

As research progresses, the distinction between permanent and transient implants continues to blur, with functionally graded materials that exhibit controlled transitions from structural to degradable regions. The future of biomedical implants lies not in a single material solution, but in rationally designed material systems precisely engineered across the biodegradability spectrum to address specific clinical needs and healing timelines.

From Bench to Bedside: Application-Oriented Performance in Medical Devices

Orthopedic implants are critical for restoring function and alleviating pain in millions of patients suffering from musculoskeletal injuries and degenerative diseases. The global orthopaedic implant market, projected to reach $79.5 billion by 2030, reflects the substantial demand for these devices [34]. The fundamental purpose of load-bearing implants—including joint replacements, fracture fixation plates, and spinal implants—is to withstand the complex mechanical forces encountered during daily activities while facilitating biological integration and long-term stability. However, the mechanical environment presents significant challenges, as inadequate load-bearing capacity can lead to catastrophic failure through mechanisms such as implant fracture, loosening, or stress shielding that compromises surrounding bone [34].

The ongoing debate in biomaterials research centers on selecting optimal materials that balance mechanical performance with biological compatibility. Metallic biomaterials have historically dominated load-bearing applications due to their exceptional strength and fatigue resistance, but they present limitations including stress shielding, ion release, and artifacts in medical imaging [34] [11]. Polymeric biomaterials offer advantages such as radiolucency and modulus closer to bone, though their mechanical strength often remains inferior to metals [14]. This comparison guide objectively examines the mechanical properties, experimental methodologies, and clinical performance of metallic versus polymeric biomaterials for orthopaedic applications, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for material selection and development.

Material Classes and Key Properties

Metallic Biomaterials

Metallic biomaterials represent the most extensively used class in load-bearing orthopaedic applications, with a service lifetime of approximately twenty years [11]. These materials are preferred for their excellent mechanical strength, durability, and biocompatibility under demanding physiological conditions [34]. Titanium and its alloys have gained prominence due to their favorable strength-to-weight ratio, corrosion resistance, and elastic modulus lower than stainless steel or cobalt-chromium alloys, thus reducing stress shielding effects [34] [12]. Advanced β-Ti alloys with molybdenum, niobium, and tantalum as alloying elements have been developed to further decrease elastic modulus to levels closer to bone (10-30 GPa) while maintaining strength [12]. Magnesium alloys represent an emerging category of biodegradable metallic materials that offer the potential to eliminate secondary removal surgeries, though their rapid degradation kinetics in physiological environments requires careful alloying and surface modification to match resorption rates with bone healing [34].

Polymeric Biomaterials

Polymeric biomaterials provide distinct advantages for orthopaedic applications, including radiolucency, lighter weight, and elastic modulus closer to bone, which helps reduce stress shielding [34] [25]. Polyether ether ketone (PEEK) has emerged as a leading high-performance polymer for spinal implants and other load-bearing applications due to its excellent mechanical properties, biocompatibility, and inherent radiolucency that enables clear postoperative imaging [34]. Bioabsorbable polymers such as polylactic acid (PLA), polyglycolic acid (PGA), and their copolymers (PLGA) are used for fracture fixation devices that gradually transfer load to healing bone while eliminating the need for hardware removal [34] [11]. Recent advancements in polymer science have led to composite materials such as carbon fiber-reinforced PEEK (CFR-PEEK), which offers enhanced strength and stiffness tailored to match bone's mechanical properties more closely [34]. Natural polymers including collagen, chitosan, and hyaluronic acid are also being investigated for tissue engineering scaffolds, though their mechanical properties generally require reinforcement for load-bearing applications [25].

Table 1: Mechanical Properties of Major Biomaterial Classes for Orthopedic Implants

| Material Category | Specific Materials | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Fatigue Strength | Key Clinical Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metallic | Titanium Alloys (Ti-6Al-4V) | 110-125 [12] | 860-900 [34] | High | Excellent strength-to-weight ratio, osseointegration |

| Stainless Steel (316L) | 190-200 [34] | 640-750 [34] | High | Cost-effective, high strength | |

| Cobalt-Chromium Alloys | 200-250 [34] | 900-1500 [34] | Very High | Extreme wear resistance | |

| Magnesium Alloys (biodegradable) | 41-45 [14] | 200-300 [14] | Moderate | Biodegradable, prevents stress shielding | |

| Polymeric | PEEK | 3-4 [34] [14] | 90-100 [34] | Moderate | Radiolucent, bone-like stiffness |

| CFR-PEEK | 10-18 [34] | 200-300 [34] | Good | Tailorable anisotropy, strength | |

| UHMWPE | 0.5-1.0 [25] | 30-40 [25] | Moderate | Excellent wear resistance, bearing surfaces | |

| PLLA (bioresorbable) | 2.7-4.1 [14] | 50-70 [14] | Low | Biodegradable, eliminates removal surgery |

Composite and Advanced Biomaterials

Composite biomaterials represent a promising approach to overcome limitations of single-material systems by combining advantageous properties from multiple constituents [34] [11]. Carbon fiber-reinforced PEEK (CFR-PEEK) exemplifies this strategy, marrying PEEK's biocompatibility with carbon fibers for enhanced strength and stiffness closer to bone, while maintaining MRI compatibility for postoperative imaging [34]. Nanocomposites incorporating hydroxyapatite, titanium nanoparticles, or other nanoscale reinforcements offer further opportunities to tailor mechanical properties and biological responses [34] [11]. These advanced materials can be engineered with graded or anisotropic properties that more closely mimic the complex structure of natural bone, potentially reducing stress concentrations and improving long-term performance [34].

Experimental Characterization of Mechanical Properties

Standardized Mechanical Testing Protocols

The mechanical characterization of biomaterials for orthopedic implants follows standardized protocols to ensure reproducibility, clinical relevance, and regulatory compliance. Quasi-static tensile testing according to ASTM F2516 or ISO 7206 standards provides fundamental mechanical properties including elastic modulus, yield strength, ultimate tensile strength, and elongation to failure [35] [12]. For orthopaedic applications, compression testing is equally critical, particularly for materials intended for spinal implants or joint replacement components that experience compressive loads [35]. Fatigue testing conducted per ASTM F1800 or ISO 14879 standards evaluates the material's resistance to cyclic loading, which simulates the physiological loading conditions encountered during walking or other daily activities [35]. Wear testing using pin-on-disk or joint simulators (ASTM F732) is essential for bearing surfaces in joint replacements, where particulate wear debris can trigger inflammatory responses and osteolysis [34].

Specialized Methodologies for Biomaterials

Beyond standard mechanical tests, specialized methodologies have been developed to address the unique challenges of orthopaedic biomaterials. Microcompression and nanoindentation techniques enable mechanical characterization at the microstructural level, providing insights into local variations in properties and their relationship to microstructure [36]. These techniques are particularly valuable for porous scaffolds and surface-modified implants where bulk properties may differ significantly from local characteristics [36]. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) has emerged as a powerful tool for mapping nanomechanical properties of biomaterials and even living cells, with applications in understanding cell-material interactions [36]. For biodegradable materials, immersion testing in simulated body fluids (SBS) at physiological temperature (37°C) and pH (7.4) allows researchers to monitor changes in mechanical properties over time, simulating the degradation process that occurs in vivo [14].

Diagram 1: Comprehensive workflow for mechanical characterization of orthopedic biomaterials, covering from material selection through performance evaluation with key standardized tests.

Computational Modeling Approaches