Evidence Levels in Biomaterial Research: A Framework from Bench to Bedside

This article provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the hierarchy of evidence in biomaterials research, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Evidence Levels in Biomaterial Research: A Framework from Bench to Bedside

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the hierarchy of evidence in biomaterials research, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational concepts of evidence-based biomaterials, detailing the translation roadmap from basic research to commercial medical products. The content delves into methodological applications, including systematic reviews and meta-analyses, for generating robust scientific evidence. It further addresses common challenges in study design and data interpretation, offering optimization strategies and exploring the role of advanced tools like AI. Finally, it covers validation and comparative techniques essential for regulatory approval and clinical translation, synthesizing key takeaways to guide future research and development in the field.

What Are Evidence Levels? Foundational Principles for Biomaterial Scientists

Defining the EBBR Framework in Preclinical Research

Evidence-Based Biomaterials Research (EBBR) represents a systematic approach to evaluating biomaterial efficacy and safety through rigorously designed preclinical studies. This methodology emphasizes standardized experimental parameters, appropriate model selection, and robust data analysis to generate reliable, translatable evidence for clinical applications. In joint repair research, for instance, EBBR principles have been applied to evaluate a plethora of promising devices, with the recognition that study design significantly influences therapeutic outcomes and clinical translation potential [1]. The framework provides a structured pathway for navigating the complex journey from laboratory discovery to clinical implementation, addressing the critical need for consensus in experimental design that has historically made conclusions on efficacy difficult to draw [1].

The foundation of EBBR rests upon eliminating potential sources of bias through meticulous experimental planning. Key bias domains addressed in rigorous EBBR include selection bias (through proper randomization), detection bias (via blinded outcome assessment), attrition bias (by accounting for all results), and reporting bias (through comprehensive outcome reporting) [1]. This systematic approach to bias management enhances the reliability of preclinical findings, which is essential for successful progression through the stringent review processes required for regulatory approval [1]. By implementing these principles, EBBR aims to standardize experimental approaches across the field, ultimately advancing the effective translation of novel biomaterial-based therapeutics to the clinic.

Core Methodological Principles of EBBR

Systematic Literature Review and Risk of Bias Assessment

The EBBR approach employs systematic literature review methodologies to identify key experimental parameters that significantly affect biomaterial therapeutic outcomes. This process begins with defined search criteria across scientific databases such as PubMed, using specific terms related to the biomaterial application [1]. For joint repair studies, inclusion criteria typically focus on English-language publications utilizing large animal models (pig, goat, sheep, horse) investigating biomaterial-based treatments for knee cartilage defects, while excluding studies incorporating growth factors, genetic material, or other biological fluids [1].

Risk of Bias (RoB) assessment forms the cornerstone of EBBR quality evaluation. Modified tools like the Office of Health Assessment and Translation (OHAT) and Systematic Review Centre for Laboratory Animal Experimentation (SYRCLE) are utilized to score studies across multiple bias domains [1]. Studies are evaluated based on sample allocation sequences, blinded outcome assessment, completeness of outcome reporting, use of appropriate validated outcomes, ethical approval, and conflict of interest declarations [1]. This rigorous scoring system allows researchers to identify high-quality studies with low RoB, which form the evidence base for reliable conclusions about biomaterial performance.

Key Experimental Parameters in Biomaterial Evaluation

EBBR emphasizes the critical importance of standardizing key experimental parameters to enable valid comparisons between studies. Through systematic analysis of low RoB publications, EBBR has identified several factors that significantly influence outcomes in joint repair research, including defect localization, animal age and maturity, selection of appropriate controls, and the use of cell-free versus cell-laden biomaterials [1].

The selection of animal models represents another crucial consideration in EBBR. Different species offer distinct advantages and limitations; for example, miniature pigs are often preferred due to joint size and cartilage thickness (0.5-1.5 mm in the medial femoral condyle) similar to humans (1.69-2.55 mm), while sheep models show more variability in cartilage thickness (0.45-1.68 mm) that can lead to inconsistent outcomes [1]. Understanding these model-specific characteristics is essential for proper study design and interpretation of results within the EBBR framework.

Comparative Analysis of Biomaterial Performance

EBBR Application in Osteochondral Repair

The systematic application of EBBR principles to osteochondral repair studies has yielded significant insights into biomaterial performance. Analysis of low RoB studies revealed that mechanically strong biomaterials perform better at the femoral condyles, while highlighting the importance of including native tissue controls to properly evaluate the quality of newly formed tissue [1]. Furthermore, in cell-laden biomaterials, the pre-culture conditions played a more important role in defect repair than the cell type itself [1].

Table 1: Key Experimental Parameters Identified Through EBBR in Osteochondral Repair Studies

| Parameter Category | Specific Factors | Impact on Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Defect Characteristics | Location (femoral condyle vs. other sites) | Mechanically strong biomaterials perform better at femoral condyles [1] |

| Size and volume | Must be standardized relative to species-specific cartilage thickness [1] | |

| Animal Model | Species selection (pig, sheep, goat, horse) | Influences comparability to human pathology and healing processes [1] |

| Age and maturity | Affects healing response and translation to human clinical scenarios [1] | |

| Experimental Design | Control group selection | Native tissue controls essential for proper evaluation of repair tissue quality [1] |

| Cell-free vs. cell-laden approaches | Cell pre-culture conditions more critical than cell type [1] |

These findings demonstrate how EBBR methodologies can extract meaningful patterns from diverse studies, providing evidence-based guidance for future research directions and clinical translation strategies. The systematic comparison approach allows researchers to identify not only which biomaterials show promise, but also under what specific conditions they demonstrate efficacy.

Natural vs. Synthetic Biomaterials in Cardiac Tissue Engineering

EBBR principles have been applied to compare natural and synthetic biomaterials for cardiac tissue regeneration, revealing distinct advantages and limitations for each category. Natural biomaterials like chitin, chitosan, cellulose, and hyaluronic acid demonstrate excellent biodegradability and biocompatibility with human cardiac tissue [2]. In contrast, synthetic biomaterials such as poly-vinyl alcohol, polyglycolic acid, and polyurethane offer high customizability but may lack the innate biological recognition of natural alternatives [2].

The EBBR approach indicates that natural biomaterials currently fulfill more desired characteristics for cardiac tissue regeneration compared to synthetic options [2]. However, the framework also highlights the emerging potential of hybrid biomaterials that combine advantages from both categories, suggesting this may represent the optimal solution for future therapeutic development [2]. This evidence-based comparison provides valuable guidance for researchers selecting biomaterial strategies for specific cardiac repair applications.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Biomaterial Categories Through EBBR Framework

| Evaluation Criterion | Natural Biomaterials | Synthetic Biomaterials | Hybrid Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biocompatibility | Excellent compatibility with human cardiac tissue [2] | Variable; depends on material composition and degradation products | Can be engineered to optimize compatibility |

| Biodegradability | Controlled, predictable degradation profiles [2] | Tunable but may produce less biocompatible breakdown products | Balance of natural degradation with synthetic control |

| Customizability | Limited by natural material properties | High degree of chemical and physical customization [2] | Maximum design flexibility combining both approaches |

| Mechanical Properties | May lack required strength for some applications | Highly tunable mechanical characteristics [2] | Can achieve ideal mechanical match for target tissue |

| Clinical Translation | Generally favorable safety profiles | May face regulatory hurdles due to novel chemistry | Combines established natural materials with enhanced functionality |

Experimental Protocols in EBBR

Large Animal Model Selection and Surgical Protocols

EBBR emphasizes standardized surgical protocols for creating osteochondral defects in large animal models. The recommended approach involves creating critical-sized defects in weight-bearing areas of the femoral condyles, with dimensions proportional to the species-specific joint anatomy [1]. For miniature pigs, defect diameter typically ranges from 4-6 mm, while in sheep models, 4-5 mm defects are common, reflecting the smaller joint dimensions [1]. These defect sizes must be calibrated against the specific cartilage thickness of the chosen model, which varies significantly between species - from 0.45-1.68 mm in sheep to 0.5-1.5 mm in miniature pigs [1].

Postoperative care and evaluation timelines represent another critical component of EBBR protocols. Studies employing EBBR principles typically include standardized rehabilitation protocols, pain management strategies, and predetermined evaluation timepoints (e.g., 3, 6, and 12 months) to assess both short-term and long-term outcomes [1]. The inclusion of multiple assessment timepoints allows for evaluation of the temporal progression of tissue integration, remodeling, and maturation, providing a more comprehensive understanding of biomaterial performance throughout the healing process.

Outcome Assessment Methodologies

EBBR incorporates comprehensive, multimodal outcome assessments to evaluate biomaterial efficacy. Macroscopic evaluation includes scoring systems for tissue appearance, integration with surrounding tissue, and surface characteristics [1]. Histological analyses provide critical information about tissue architecture, cellular distribution, and extracellular matrix composition using standardized staining protocols (e.g., hematoxylin and eosin, safranin-O, collagen type II immunohistochemistry) [1].

Biomechanical testing forms another essential component of EBBR assessment protocols, evaluating the functional integration of the repair tissue through indentation testing, tensile testing, and other mechanical property assessments [1]. These quantitative measurements provide crucial data about the functional performance of the regenerated tissue compared to native cartilage. Additionally, biocompatibility evaluations assess local and systemic inflammatory responses, degradation characteristics of the biomaterial, and overall tissue biocompatibility through histological analysis and evaluation of immune cell infiltration [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for EBBR Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Biomaterials | Provide biocompatible scaffolding with inherent biological recognition | Chitin, chitosan, cellulose, hyaluronic acid [2] |

| Synthetic Biomaterials | Offer highly customizable mechanical and chemical properties | Poly-vinyl alcohol, polyglycolic acid, polyurethane [2] |

| Cell Sources | Provide cellular component for cell-laden approaches | Chondrocytes, mesenchymal stem cells, induced pluripotent stem cells [1] |

| Histological Stains | Enable evaluation of tissue architecture and composition | Hematoxylin and eosin, safranin-O, collagen type II immunohistochemistry [1] |

| Biomechanical Testing Equipment | Assess functional integration and mechanical properties | Indentation testers, tensile testing systems, dynamic mechanical analyzers [1] |

| HEX azide, 6-isomer | HEX azide, 6-isomer, MF:C24H12Cl6N4O6, MW:665.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Fluoro-5-iodobenzylamine | 2-Fluoro-5-iodobenzylamine, 771572-96-4 | 2-Fluoro-5-iodobenzylamine (CAS 771572-96-4) is a key building block for pharmaceutical and chemical research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

This toolkit represents the essential components for conducting rigorous EBBR studies in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. The selection of specific reagents and materials should be guided by the research question, target tissue, and desired outcomes, with careful consideration of the evidence supporting each component's efficacy for the intended application.

The EBBR framework represents a paradigm shift in biomaterial evaluation, emphasizing evidence-based decision-making throughout the research process. By implementing systematic methodologies, standardized protocols, and comprehensive outcome assessments, EBBR enhances the reliability, reproducibility, and clinical translatability of biomaterial research findings. The comparative analyses enabled by this approach provide valuable insights into the performance characteristics of different biomaterial strategies under specific experimental conditions, guiding future research directions and clinical application decisions.

As the field continues to evolve, EBBR principles will play an increasingly important role in navigating the complex landscape of biomaterial development and validation. The continued refinement of EBBR methodologies, including the development of more sophisticated outcome measures and standardized reporting guidelines, will further enhance the quality and impact of biomaterial research. Ultimately, the widespread adoption of EBBR principles promises to accelerate the translation of promising biomaterial technologies from the laboratory to clinical practice, addressing unmet needs in tissue repair and regeneration.

The development of biomaterials from basic research to commercialized medical products is a complex, multidisciplinary endeavor fraught with translational obstacles. The biomaterials market, estimated at over 100 billion USD in 2019 with a compound annual growth rate of 15.9%, demonstrates significant therapeutic and commercial potential, yet the journey from discovery to clinical adoption often takes decades [3]. For instance, the translation of PLGA from initial biocompatibility studies to an approved product for prostate cancer therapy spanned approximately 20 years [3]. This lengthy timeline underscores the critical need for robust methodologies to validate and prioritize promising biomaterials research.

The emerging discipline of Evidence-Based Biomaterials Research (EBBR) addresses this need by applying systematic, evidence-based approaches—spearheaded by systematic reviews and meta-analyses—to translate vast research data into validated scientific evidence [4] [5]. This paradigm shift moves the field beyond unstructured empirical approaches toward development strategies entrenched in data validation, enabling researchers to navigate the "valley of death" where promising academic solutions frequently stall [6]. This guide compares traditional and evolving research strategies within a hierarchical evidence framework, providing researchers with a structured approach to evaluate biomaterials' clinical potential.

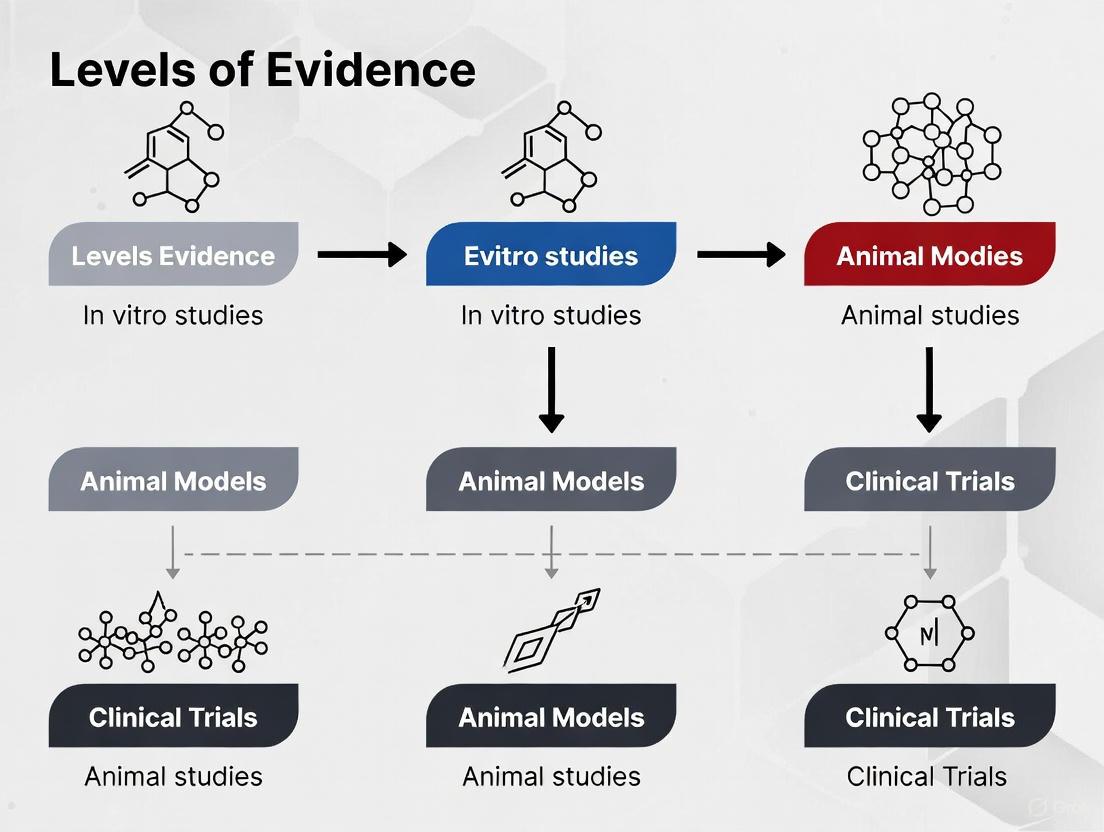

Levels of Evidence in Biomaterials Research

In evidence-based practice, research findings are categorized according to their inherent reliability and freedom from bias. This hierarchy, illustrated below, provides a critical framework for assessing the strength of biomaterials research claims.

Figure 1: The Evidence Hierarchy Pyramid for Biomaterials Research. Level I represents the strongest, most synthesized evidence, while Level V represents the least filtered information. Adapted from established evidence-based medicine principles [7] [8].

Understanding the Evidence Levels

- Level I (Strongest Evidence): Systematic reviews and meta-analyses comprehensively synthesize all available evidence on a specific research question. For example, an EBBR approach using systematic review can generate validated evidence about a biomaterial's performance across multiple studies, providing the highest confidence for clinical decision-making [4] [7].

- Level II: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) provide high-quality experimental evidence where participants are randomly allocated to treatment or control groups. While more common in clinical settings, controlled preclinical studies in animal models also fall under this category when properly randomized [7] [8].

- Level III: Cohort studies follow groups of subjects (e.g., animals or human patients) exposed to a particular biomaterial over time, comparing their outcomes to unexposed groups. These observational studies provide valuable longitudinal data but with less control than RCTs [7] [9].

- Level IV: Case-control studies and case series report on outcomes for a small group of subjects or a single subject without control groups. These are often used for initial safety reports or preliminary efficacy signals [7] [8].

- Level V (Weakest Evidence): Expert opinion, background information, and mechanistic studies based on non-systematic reviews represent the lowest level of evidence, though they can provide valuable foundational knowledge for further research [7] [8].

Comparative Analysis of Biomaterial Research Approaches

Traditional Empirical Development vs. Evidence-Based and Data-Driven Approaches

The biomaterials field is undergoing a fundamental transformation from reliance on traditional empirical methods to more systematic, evidence-based approaches. The table below compares these evolving research paradigms.

Table 1: Comparison of Biomaterials Research and Development Approaches

| Research Aspect | Traditional Empirical Approach | Evidence-Based Approach (EBBR) | Data-Driven/Machine Learning Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Methodology | Trial-and-error experimentation based on researcher intuition and literature precedents [3] | Systematic review and meta-analysis of existing research data [4] [5] | Machine learning algorithms trained on high-throughput experimental data [3] |

| Data Utilization | Limited, unstructured data analysis; focus on individual studies | Comprehensive synthesis of all available published data | Analysis of multi-dimensional datasets including composition, structure, and properties [3] |

| Translation Timeline | Lengthy (e.g., ~20 years for PLGA translation) [3] | Potentially accelerated through validated evidence | Dramatically accelerated prediction of optimized materials (e.g., 10 hours vs. 5 days for composites) [3] |

| Key Strengths | Direct researcher control; established protocols | High-quality, validated evidence; reduced bias | Handles complex parameter spaces; discovers non-intuitive relationships [3] |

| Limitations | Susceptible to bias; limited scope; inefficient | Dependent on quality of primary studies | Requires large, high-quality datasets; "black box" limitations |

Case Comparison: Printable Biomaterials for Neural Tissue Engineering

Recent research on neural tissue engineering scaffolds provides exemplary data for comparing biomaterials across multiple evidence levels. The following table synthesizes experimental findings from a comprehensive study evaluating four thermoplastics and one hydrogel for neural applications [10].

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of 3D-Printed Biomaterials for Neural Tissue Engineering

| Biomaterial | Printability & Resolution | Mechanical Properties | In Vitro Cell Viability | In Vivo Biocompatibility (10 days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA | Superior printability, high resolution and shape fidelity [10] | Excellent thermal stability, degradability [10] | Moderate | Connective tissue encapsulation with some inflammatory cells [10] |

| PCL | Superior printability, high resolution and shape fidelity [10] | Mechanical elasticity, long-term degradation, low melting point [10] | Moderate | Connective tissue encapsulation with some inflammatory cells [10] |

| Filaflex (FF) | Good printing results [10] | High flexibility (92A shore hardness), electroconductive [10] | Moderate | Connective tissue encapsulation with some inflammatory cells [10] |

| Flexdym (FD) | Good printing results [10] | Great viscoelastic properties, flexible, stretchable [10] | Moderate | Connective tissue encapsulation with some inflammatory cells [10] |

| GelMA Hydrogel | Lower resolution compared to thermoplastics [10] | Great viscoelastic properties, tunable mechanical properties [10] | Greater cell viability after 7 days [10] | Connective tissue encapsulation with some inflammatory cells [10] |

This comparative data demonstrates how different biomaterials offer distinct advantages depending on the target application requirements, with thermoplastics generally providing superior structural characteristics while hydrogels like GelMA offer enhanced biocompatibility.

Experimental Protocols for Biomaterial Evaluation

Standardized Workflow for Biomaterial Characterization

The translation of biomaterials requires rigorous, standardized characterization across multiple domains. The following diagram outlines a comprehensive experimental workflow for evaluating candidate biomaterials.

Figure 2: Progressive Workflow for Biomaterial Evaluation. The workflow progresses from material characterization (yellow) to in vitro testing (blue) and finally to in vivo assessment (red/green), representing increasing evidence levels [10].

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

Printability and Mechanical Testing Protocol

Objective: Evaluate biomaterials for extrusion-based 3D printing and characterize mechanical properties relevant to neural tissue engineering [10].

Materials Preparation:

- Thermoplastics: Use ready-to-use filaments (PLA, PCL, Filaflex) or pellets (Flexdym) [10].

- Hydrogel: Prepare 10% GelMA/0.5 LAP (w/v) by dissolving 60 mg LAP (lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate) in 12 mL of 1× sterile phosphate buffer solution, then adding lyophilized GelMA [10].

Printability Assessment:

- Utilize extrusion-based 3D printing systems (e.g., fused deposition modeling for thermoplastics, 3D plotting for hydrogels).

- Assess printing parameters: resolution, shape fidelity, structural integrity.

- Optimize nozzle temperature (for thermoplastics) or crosslinking conditions (for photopolymerizable hydrogels like GelMA) [10].

Mechanical Testing:

- Perform uniaxial tensile testing according to ASTM D638 standards.

- Measure elastic modulus, ultimate tensile strength, and elongation at break.

- For viscoelastic materials (e.g., FD, GelMA), conduct dynamic mechanical analysis to characterize storage and loss moduli [10].

In Vitro Cell-Biomaterial Interaction Protocol

Objective: Evaluate cellular response to biomaterials, including viability, adhesion, and proliferation [10].

Cell Culture:

- Use relevant cell lines (e.g., neural stem cells, Schwann cells) or primary cells.

- Culture cells according to established protocols with appropriate media supplements.

- Seed cells onto sterilized 3D-printed scaffolds at standardized densities (e.g., 50,000 cells/scaffold).

Viability Assessment:

- Employ live/dead staining at predetermined intervals (e.g., 1, 3, 7 days).

- Quantify viability using fluorescence microscopy and image analysis software.

- Alternatively, use metabolic assays (e.g., MTT, Alamar Blue) at 24-hour intervals [10].

Cell Morphology and Differentiation:

- Fix cells and perform immunocytochemistry for neural markers (e.g., β-III-tubulin, GFAP).

- Image using confocal microscopy to assess cell morphology and differentiation.

- Quantify expression levels using flow cytometry or Western blotting where appropriate.

In Vivo Biocompatibility Assessment Protocol

Objective: Evaluate host response to implanted biomaterials in animal models [10].

Animal Model and Implantation:

- Use appropriate immunocompetent animal models (e.g., rats, mice).

- Perform surgical implantation of sterilized scaffolds according to approved ethical protocols.

- Include appropriate controls (sham surgery, commercially available materials).

Histological Analysis:

- Euthanize animals at predetermined endpoints (e.g., 10 days, 30 days).

- Harvest implantation sites with surrounding tissue.

- Process for histology: fix in formalin, dehydrate, embed in paraffin, section.

- Stain with Hematoxylin & Eosin for general morphology and Masson's Trichrome for collagen deposition.

- Score inflammatory response semi-quantitatively based on immune cell infiltration [10].

Immunohistochemical Analysis:

- Perform staining for specific immune markers (e.g., CD68 for macrophages, CD3 for T-lymphocytes).

- Assess fibrous capsule thickness and composition.

- Evaluate tissue integration and vascularization at the implant-tissue interface.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Biomaterials Translation

| Reagent/Category | Function | Specific Examples | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Polymers | Provide 3D scaffold architecture and mechanical support | PLA, PCL, Polyurethane (Filaflex), SEBS (Flexdym) [10] | Thermoplastics offer superior printability; synthetic polymers provide tunable mechanical properties [10] |

| Biofunctional Hydrogels | Mimic extracellular matrix; support cell adhesion and signaling | GelMA (gelatin methacrylate) [10] | Photocrosslinkable; offers biofunctionality with mechanical tunability; superior cell viability [10] |

| Crosslinking Agents | Enable hydrogel solidification and stability | LAP (lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate) [10] | Photoinitiator for UV crosslinking of methacrylated polymers; critical for maintaining structural fidelity |

| Cell Culture Reagents | Support in vitro cell viability, growth, and differentiation | Neural stem cells, Schwann cells, appropriate culture media [10] | Primary cells provide most relevant response; standardized media formulations essential for reproducibility |

| Characterization Reagents | Enable assessment of material properties and biological responses | Live/Dead staining kits, antibodies for immunostaining, histological stains [10] | Critical for quantifying cell-material interactions; validate biocompatibility claims |

| Cyclopentadiene-quinone (2 | Cyclopentadiene-quinone (2, MF:C16H16O2, MW:240.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Apoptosis inducer 4 | Apoptosis Inducer 4|RUO | Apoptosis Inducer 4 is a potent compound with anticancer research applications. This product is for Research Use Only and not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

Navigating the Translation Pathway: From Evidence to Clinical Product

The journey from laboratory research to clinical product requires careful navigation of regulatory, manufacturing, and validation hurdles. The following diagram illustrates this complex translation pathway.

Figure 3: The Biomaterials Translation Pathway. This roadmap highlights key stages from basic research to clinical adoption, emphasizing the critical role of evidence synthesis in de-risking translation [4] [6].

Advanced Translation Strategies

Adaptive Validation Frameworks

Recent innovations propose adaptive validation frameworks that align evidence requirements with an AI tool's risk profile, integrating real-world evidence for more efficient clinical translation [11]. As stated by researchers developing these frameworks, "Accuracy isn't enough—what matters is impact on patient outcomes" [11]. This approach is particularly relevant for data-driven biomaterial discovery enabled by machine learning.

Immune-Compatible Design Strategies

Considering the host immune response throughout therapeutic development is crucial for translational success. Design strategies include:

- Biomaterial Surface Modification: Modulating hydrophilicity to control protein adsorption (e.g., hydrophobic surfaces for albumin adsorption to block cell adhesion) [6].

- Mechanical Property Optimization: Matching tissue-specific stiffness (e.g., softer materials for neural tissues) to modulate immune activation [6].

- Controlled Degradation Profiles: Using synthetic biomaterials that hydrolyze into non-toxic byproducts or incorporating enzyme-cleavable crosslinks for environmentally-responsive degradation [6].

The biomaterials translation roadmap is evolving from traditional empirical approaches toward evidence-based and data-driven methodologies. By systematically applying evidence hierarchies, employing standardized experimental protocols, and leveraging emerging technologies like machine learning, researchers can accelerate the development of safer, more effective biomaterials while reducing costly translational failures. The comparative data and methodologies presented in this guide provide a framework for researchers to design robust development strategies that generate high-quality evidence, ultimately bridging the gap between promising laboratory results and clinically impactful medical products.

In the rigorous fields of biomaterials science and drug development, the ability to distinguish between strong and weak evidence is fundamental. The hierarchy of evidence is a core principle of evidence-based medicine (EBM), providing a structured framework for ranking research methodologies based on their reliability and potential for bias [12]. This pyramid-shaped hierarchy ensures that clinical guidelines and research directions are informed by the most trustworthy evidence available, with systematic reviews and meta-analyses at its apex, followed by randomized controlled trials, observational studies, and expert opinions [8] [12]. For researchers and scientists, understanding this hierarchy is not merely academic; it is a critical tool for designing robust studies, critically appraising published literature, and making informed decisions that ultimately impact patient care and product development.

The concept of a hierarchy of evidence originated in the mid-20th century, championed by figures like Archie Cochrane, who emphasized the necessity of systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [12]. This approach has since evolved into a more nuanced system, formalized by organizations like the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, which classifies evidence into levels to guide practitioners and policymakers [9]. In biomaterials research, where the translation of a new material from the lab to a commercial medical product is complex and costly, employing a sound evidence-based approach is increasingly recognized as vital for validating scientific findings and prioritizing research resources [4].

The Evidence Pyramid: A Detailed Breakdown

The hierarchy of evidence is commonly visualized as a pyramid. This section provides a detailed comparison of each level, from the most to the least methodologically rigorous.

Level 1: Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

At the top of the pyramid are systematic reviews and meta-analyses, which represent the highest quality of evidence [8] [12]. A systematic review is a type of literature review that uses a systematic and predefined process to identify, select, and critically appraise all available research on a specific, focused question [13]. A meta-analysis is a statistical component that quantitatively combines and synthesizes the results of the selected studies, thereby providing a more precise estimate of an intervention's effect [13].

The primary strength of this level is its comprehensive nature and its ability to minimize bias through a structured, transparent, and reproducible methodology [12]. By synthesizing findings from multiple studies, systematic reviews can resolve uncertainties and contradictions in the literature. However, it is crucial to note that the quality of a systematic review is entirely dependent on the quality of the individual studies it includes; a review of flawed or biased primary studies will produce similarly flawed conclusions [12].

Level 2: Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs)

Just below systematic reviews are Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs). In an RCT, participants are randomly allocated to either an intervention group or a control group. This random allocation is a powerful methodological feature that minimizes selection bias and helps ensure that the groups are comparable at the start of the trial [12]. This design allows researchers to establish causal relationships between an intervention and an outcome with high confidence.

RCTs are considered the gold standard for evaluating the efficacy of new therapies or interventions. Nevertheless, they have limitations: they can be resource-intensive and expensive, may raise ethical concerns in certain situations, and their highly controlled setting can sometimes limit the generalizability of their findings to real-world clinical practice [12].

Level 3: Observational Studies (Cohort and Case-Control Studies)

Occupying the middle of the pyramid are observational studies, which include cohort studies and case-control studies. Unlike RCTs, researchers in observational studies do not assign interventions; they instead observe and analyze the effect of an exposure or intervention as it occurs naturally.

- Cohort Studies: These follow a group of people (a cohort) over time to see how different exposures affect outcomes. They can be prospective (following groups forward in time) or retrospective (looking back at historical data) [12]. Prospective designs generally provide more reliable data.

- Case-Control Studies: These start with individuals who already have a disease (cases) and compare them to similar individuals without the disease (controls), looking back to identify differences in exposure [9].

While observational studies are invaluable for investigating questions where RCTs are not feasible (e.g., studying the harmful effects of smoking), they are more susceptible to confounding variables, which can obscure the true relationship between an exposure and an outcome [12].

Level 4: Case Series and Case Reports

Case series and case reports provide detailed descriptions of a single patient or a small group of patients with a similar condition or treatment. They are primarily hypothesis-generating and are particularly useful for reporting rare diseases, unexpected treatment effects, or novel surgical techniques [12].

Due to their small scale, lack of a control group, and inherent selection bias, they sit low on the evidence hierarchy. Their findings are not generalizable to the broader population, but they can serve as a critical first step in identifying new areas for more rigorous investigation [12].

Level 5: Expert Opinion and Anecdotal Evidence

At the base of the pyramid are expert opinions and anecdotal evidence. This level relies on the personal experience and judgment of authorities in the field rather than systematic research [8] [12]. While expert opinion can be insightful for addressing complex clinical questions where higher-level evidence is lacking, it is considered the least reliable form of evidence. It is highly subjective, prone to bias, and lacks the systematic methodology and controls necessary for scientific validation [12].

Table 1: Summary of Evidence Levels in Medical and Biomaterials Research

| Level | Study Type | Key Features | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis | Synthesizes multiple high-quality studies using a predefined protocol [13] [12]. | Highest level of evidence, minimizes bias, provides comprehensive conclusions [12]. | Quality dependent on included studies; can be complex and time-consuming [12]. |

| 2 | Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) | Participants randomly assigned to intervention or control groups [12]. | Establishes causation, minimizes selection bias [12]. | Can be costly, may lack generalizability, ethical constraints for some questions [12]. |

| 3 | Cohort Study | Observes groups with/without exposure over time [12]. | Suitable for studying etiology and incidence, can study multiple outcomes [12]. | Susceptible to confounding, time-consuming, not suitable for rare diseases [12]. |

| 3 | Case-Control Study | Compares subjects with a disease (cases) to those without (controls) [9]. | Efficient for rare diseases, requires fewer subjects, can study multiple exposures [12]. | Prone to recall and selection bias, cannot establish incidence or causality [12]. |

| 4 | Case Series / Report | Detailed report on one or a small group of patients [12]. | Identifies new diseases or adverse events, hypothesis-generating [12]. | No control group, susceptible to bias, low generalizability [12]. |

| 5 | Expert Opinion | Based on personal experience and judgment [8] [12]. | Useful when no research evidence exists, provides quick insights [12]. | Subjective, lacks systematic methodology, highly prone to bias [12]. |

The following diagram illustrates the standard evidence hierarchy and the foundational workflow for generating its highest level of evidence: the systematic review.

Experimental Protocols in Biomaterials Research

The principles of the evidence hierarchy are directly applicable to biomaterials research. The following examples illustrate how different study designs are implemented in this field.

Protocol for a Systematic Review

The systematic review titled "A Histological and Clinical Evaluation of Long-Term Outcomes of Bovine-Derived Xenografts" provides a clear template for this level of evidence [14].

- Research Question Formulation: The review used the PICO framework (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) to define its scope. The population was patients undergoing dental implant surgery requiring bone regeneration; the intervention was bovine-derived xenografts; the comparison was alternative grafting materials; and the outcomes were long-term clinical and histological results [14].

- Search Strategy: A comprehensive electronic search was performed across multiple databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science) using a combination of keywords like "Bio-Oss," "bovine bone graft," "bone regeneration," and "long-term" connected by Boolean operators (AND, OR) [14].

- Screening & Selection: The process followed the PRISMA guidelines. After duplicate removal, studies were screened by title/abstract and then by full text against predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria [14].

- Data Extraction & Quality Assessment: Two independent reviewers performed data extraction. The quality of evidence was further assessed using the GRADE framework, which evaluates risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias [14].

Protocol for an In Vivo Animal Study

The systematic review on "Whitlockite as a next-generation biomaterial for bone regeneration" summarizes the protocols common to many of the animal studies it synthesized [15].

- Animal Models: The included studies utilized animal bone defect models in species such as rats, mice, and rabbits to test the efficacy of Whitlockite-based materials [15].

- Intervention: The biomaterial (Whitlockite in various forms like nanoparticles, granules, and composite scaffolds) was implanted into the bone defects [15].

- Comparison: The test groups were compared against control groups, often treated with conventional materials like hydroxyapatite (HA) or β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) [15].

- Outcome Measures: Key outcomes included quantitative measures of bone regeneration, such as bone volume fraction (BV/TV) and bone mineral density (BMD), as well as histological analysis of bone quality and expression of osteogenic markers (e.g., ALP, OCN) [15].

- Quality Assessment: The reviewers used the SYRCLE Risk of Bias Tool, a specific tool for assessing bias in animal studies [15].

Table 2: Comparison of Biomaterials Study Designs and Outcomes

| Study Focus | Study Type | Level of Evidence | Primary Outcome Measures | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bovine-Derived Xenografts [14] | Systematic Review of Human Studies | Level 1 (if including RCTs) | Long-term graft integration, complication rates (inflammation, migration), implant survival [14]. | Favorable long-term outcomes and implant survival, but concerns about late-onset complications and limited biodegradability [14]. |

| Whitlockite Biomaterials [15] | Systematic Review of Animal Studies | Level 1 (for animal evidence) | Bone volume fraction (BV/TV), bone mineral density (BMD), osteogenic marker expression (ALP, OCN) [15]. | Whitlockite consistently outperformed traditional materials (HA, β-TCP), showing 2–6% greater BV/TV and BMD, with enhanced osteogenesis [15]. |

| Biodegradable Orthopaedic Implants [16] | Meta-Analysis & Statistical Review | Level 1 | Tensile strength, degradation rate, biocompatibility [16]. | Biodegradable materials showed sufficient strength for orthopaedic applications, with degradation rates in the pattern BME > NBME > BHE > BLE [16]. |

Conducting high-quality, evidence-based research requires a suite of methodological tools and resources. The table below details key solutions used across different stages of the research process.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Evidence-Based Biomaterials Research

| Tool / Resource | Category | Primary Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| PICO / PICOTTS [13] | Methodological Framework | Provides a structured approach to formulating a focused, answerable research question [13]. | Defines Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and optionally Time, Type of study, and Setting. Foundation of any systematic review [14]. |

| PubMed / MEDLINE [13] | Bibliographic Database | Provides access to a vast repository of life sciences and biomedical literature [13]. | A primary database for conducting comprehensive literature searches, often used with MeSH terms and Boolean operators [13] [14]. |

| Covidence / Rayyan [13] | Research Software | Streamlines the systematic review process by assisting with study screening, selection, and data extraction [13]. | Improves efficiency and accuracy during the systematic review workflow, enabling collaboration among reviewers [13]. |

| Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool [13] | Quality Assessment | A standardized tool for assessing the methodological quality and risk of bias in randomized controlled trials [13]. | Used in systematic reviews to evaluate the internal validity of included RCTs, informing the strength of the overall evidence [13]. |

| SYRCLE Risk of Bias Tool [15] | Quality Assessment | A tool specifically designed to assess the risk of bias in animal studies [15]. | Critical for ensuring the quality and reliability of pre-clinical evidence synthesized in systematic reviews of animal literature [15]. |

| GRADE Framework [14] | Quality Assessment | A systematic approach to rating the overall quality of a body of evidence and strength of recommendations [14]. | Used to evaluate evidence across domains (bias, inconsistency, etc.), allowing for transparent judgment of evidence certainty [14]. |

| R / RevMan [13] | Statistical Software | Specialized software for performing meta-analysis and generating statistical summaries (e.g., forest plots) [13]. | Used to compute pooled effect sizes, confidence intervals, and assess heterogeneity across studies in a meta-analysis [13]. |

The following diagram maps the logical progression of a research idea through different study designs, highlighting the iterative nature of evidence generation and the role of technological advancements.

Navigating the hierarchy of evidence is an essential skill for any professional engaged in biomaterials research or drug development. From the foundational observations of case reports to the definitive power of systematic reviews, each level of evidence plays a distinct and valuable role in the scientific ecosystem. A clear understanding of the relative strengths, weaknesses, and appropriate applications of each study design allows researchers to not only produce more robust and impactful science but also to critically evaluate the work of others. As the field continues to evolve with the integration of artificial intelligence, big data, and real-world evidence, the fundamental principles of this hierarchy will remain the bedrock of evidence-based practice, ensuring that advancements in biomaterials are built upon a foundation of rigorous, transparent, and reliable scientific evidence [12] [17].

The field of biomaterials has evolved from a materials-centric discipline to a multidisciplinary science that increasingly emphasizes biological interactions and clinical applications [18]. This rapid development has generated an enormous volume of research data, creating an urgent need for methodologies that can translate this data into validated scientific evidence [18]. The concept of evidence-based biomaterials research (EBBR) has emerged to address this need, applying systematic approaches to evaluate and synthesize research findings [18]. Central to this evaluation is understanding the distinction between primary and secondary information sources, as this distinction fundamentally impacts the reliability and level of evidence available for making scientific and clinical decisions in biomaterials development and application.

In biomaterials research, the origin of data plays a critical role in assessing its validity as scientific evidence. The classification into primary and secondary sources determines not only how the data is collected but also its potential limitations and appropriate applications.

Primary data refers to information collected directly by researchers specifically for the purpose of their study using ad hoc methods [19]. In biomaterials research, this typically includes:

- Data from original laboratory experiments investigating material synthesis, processing, structure, and properties [18]

- Biocompatibility and biosafety evaluations conducted per ISO 10993 standards [18]

- Pre-clinical animal studies designed to assess specific material performance and host responses [18]

- Objective diagnostic methods such as blood tests or imaging results specifically conducted for the research [19]

- Direct measurements of material properties and performance characteristics [18]

Secondary data comprises information that was originally collected for purposes other than the current research study and is repurposed for new investigations [19]. In biomaterials contexts, this includes:

- Prescription registers and medical records documenting device implantation outcomes [19]

- Computerized pharmacy records and insurance claims databases [19]

- Previously published research data that is reanalyzed for new insights [18]

- Clinical and administrative databases originally established for billing or other non-research purposes [19]

Table 1: Comparison of Primary and Secondary Data Sources in Biomaterials Research

| Characteristic | Primary Data | Secondary Data |

|---|---|---|

| Collection Purpose | Specifically for research questions | For non-research purposes (clinical, administrative) |

| Data Control | Researchers design collection methods | Researchers utilize existing data structures |

| Common Sources | Laboratory experiments, preclinical studies, clinical trials | Medical records, prescription databases, claims data |

| Key Advantages | Targeted to specific research questions, controlled conditions | Larger sample sizes, real-world clinical settings |

| Potential Limitations | Limited sample size, artificial experimental conditions | Missing variables, measurement bias, confounding factors |

Methodological Approaches for Evidence Generation

Experimental Protocols for Primary Data Collection

Generating robust primary evidence in biomaterials research requires standardized methodological approaches:

Material Synthesis and Characterization Protocol:

- Material Processing: Utilize sol-gel, 3D printing, or other fabrication techniques appropriate to the biomaterial class [18]

- Structure Analysis: Employ SEM, TEM, or XRD to characterize material microstructure [18]

- Property Assessment: Conduct mechanical testing, degradation studies, and surface analysis [18]

- Biological Evaluation: Perform in vitro cell culture studies to assess cytotoxicity and cellular responses [18]

Pre-clinical Evaluation Workflow:

- Animal Model Selection: Choose species-specific models (e.g., calvarial defect models for bone regeneration) [18]

- Implantation Procedure: Standardize surgical protocols and control groups [18]

- Outcome Assessment: Implement histomorphometry, micro-CT, and biomechanical testing at predetermined endpoints [18]

- Statistical Analysis: Apply appropriate power calculations and statistical methods to ensure reproducible results [18]

Systematic Review Methodology for Secondary Data Analysis

The evidence-based approach utilizes systematic reviews to synthesize existing research:

Protocol Development:

- Formulate specific research questions using PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) framework [18]

- Establish explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria for studies [18]

- Define comprehensive search strategies across multiple databases [18]

Data Extraction and Synthesis:

- Develop standardized data extraction forms to capture key study characteristics and outcomes [18]

- Implement quality assessment of individual studies using validated tools [18]

- Conduct meta-analysis when appropriate to quantitatively synthesize results [18]

Comparative Analysis: Evidence Levels and Applications

The distinction between primary and secondary data sources carries significant implications for the level of evidence they provide in the biomaterials translation roadmap from basic research to commercialized medical products [18].

Table 2: Evidence Levels and Applications in Biomaterials Translation

| Research Stage | Primary Data Applications | Secondary Data Applications | Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Research | Hypothesis testing, mechanism exploration, structure-property relationships | Literature reviews, research trend analysis, knowledge gap identification | Foundational |

| Applied Research | Prototype development, in vitro performance testing, preliminary safety assessment | Systematic reviews, meta-analyses of existing studies, research synthesis | Preclinical |

| Product Development | Biocompatibility testing, animal studies, design verification and validation | Post-market surveillance data analysis, clinical registry reviews | Regulatory |

| Clinical Evaluation | Controlled clinical trials, specific performance metrics | Real-world evidence (RWE), clinical database analysis, outcomes research | Clinical Validation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Biomaterials Evidence Generation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Primary/Secondary Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sol-gel Bioactive Glasses | Dental and periodontal tissue regeneration studies [18] | Primary data generation through in vitro and in vivo testing |

| 3D Printed Scaffolds | Bone regeneration research in calvarial defect models [18] | Primary data on design parameters (material, porosity, pore size) |

| Cell Culture Assays | Biocompatibility assessment and host-response evaluation [18] | Primary data on cellular interactions with biomaterials |

| ISO 10993 Test Materials | Standardized biosafety evaluation for regulatory approval [18] | Primary data for design validation and verification |

| Medical Device Databases | Post-market surveillance and real-world performance analysis [18] | Secondary data analysis for safety and effectiveness monitoring |

| Clinical Registry Data | Long-term outcomes assessment of implanted devices [18] | Secondary data for real-world evidence generation |

| Propyl 2,4-dioxovalerate | Propyl 2,4-dioxovalerate, CAS:39526-01-7, MF:C8H12O4, MW:172.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-Chloro-1-ethyl-piperidine | 4-Chloro-1-ethyl-piperidine, CAS:5382-26-3, MF:C7H14ClN, MW:147.64 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Analysis of Heterogeneity in Biomaterials Evidence

A critical challenge in evaluating biomaterials evidence lies in addressing heterogeneity between primary and secondary data sources. Current reporting standards in major medical journals demonstrate significant limitations in this regard:

- Only 34.8% of meta-analyses in high-impact journals report the source of data (primary vs. secondary) [19]

- Merely 13.0% include method of outcome assessment as a variable in heterogeneity analysis [19]

- Only one surveyed meta-analysis compared and discussed results considering different data sources [19]

This represents a substantial gap in evidence evaluation, as failing to account for data source heterogeneity may lead to misleading conclusions in meta-analyses of biomaterials effects [19]. The integration of primary and secondary data sources through systematic methodology is essential for comprehensive evidence assessment.

The distinction between primary and secondary information sources represents a fundamental consideration in evaluating scientific evidence for biomaterials. Primary data offers controlled, targeted insights specifically designed to answer research questions, while secondary data provides valuable real-world context and larger sample sizes. The emerging methodology of evidence-based biomaterials research emphasizes systematic approaches to synthesizing both types of evidence, with careful consideration of source heterogeneity [18]. As the field advances, explicit acknowledgment and methodological rigor in handling these distinct information sources will be crucial for generating reliable evidence to guide biomaterials development, regulatory approval, and clinical application, ultimately supporting the translation of innovative biomaterial technologies from concept to clinical practice [18].

The Critical Role of Evidence in Regulatory Approval and Clinical Translation

The journey of a biomaterial from a laboratory concept to a clinically approved medical product is governed by a rigorous, evidence-based pathway. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the hierarchy of evidence and specific regulatory requirements is crucial for successful clinical translation. The global biomaterials market, projected to grow from USD 192.43 billion in 2025 to approximately USD 523.75 billion by 2034, underscores the critical importance of this field and the evidence that supports it [20]. This guide examines the levels of evidence different biomaterial research studies generate, objectively compares regulatory strategies, and details the experimental protocols required to demonstrate safety and efficacy, providing a framework for navigating the complex translation from bench to bedside.

Regulatory Frameworks and Evidence Requirements

FDA Pathways and Evidence Standards

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) employs distinct regulatory pathways for medical devices and biomaterials, each with unique evidence requirements [21]:

- 510(k) Clearance: Requires demonstration of "substantial equivalence" to a legally marketed predicate device. Evidence typically includes comparative bench testing, preclinical data, and possibly limited clinical data.

- Premarket Approval (PMA): Mandatory for high-risk devices (Class III) with no predicate, requiring extensive scientific evidence, including robust clinical trial data.

- De Novo Classification: For novel, low-to-moderate risk devices with no predicate, requiring evidence of safety and effectiveness through analytical, preclinical, and clinical data as needed.

The FDA has increasingly incorporated Real-World Evidence (RWE) into regulatory decision-making. As shown in , RWE has supported various regulatory actions, including new approvals and label changes, across multiple medical product types [22].

Table 1: FDA Use of Real-World Evidence in Regulatory Decisions (Select Examples)

| Product | Data Source | Study Design | Regulatory Action | Role of RWE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aurlumyn (Iloprost) [22] | Medical records | Retrospective cohort study | New drug approval (Feb 2024) | Confirmatory evidence |

| Vimpat (Lacosamide) [22] | PEDSnet data network | Retrospective cohort study | Labeling change (Apr 2023) | Safety data for new dosing |

| Actemra (Tocilizumab) [22] | National death records | Randomized controlled trial | Approval (Dec 2022) | Primary efficacy endpoint in an AWC* study |

| Prolia (Denosumab) [22] | Medicare claims data | Retrospective cohort study | Boxed Warning (Jan 2024) | Identified risk of severe hypocalcemia |

Note: AWC = Adequate and Well-Controlled

Accelerated Approval and Confirmatory Evidence

For serious conditions with unmet medical needs, the Accelerated Approval Pathway allows approval based on surrogate endpoints (e.g., laboratory measures or physical signs) that are "reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit" [23]. This pathway is critical for accelerating patient access to novel therapies, including advanced biomaterials. However, it mandates post-approval confirmatory trials to verify the anticipated clinical benefit. Recent FDA guidances emphasize that these confirmatory trials should be underway at the time of approval, with clearly defined milestones to ensure timely completion [23]. Failure to verify clinical benefit in confirmatory trials or to demonstrate safety can lead to product withdrawal from the market.

Hierarchy of Evidence in Biomaterials Research

The strength of conclusions drawn from biomaterials research depends fundamentally on the study design. The "hierarchy of evidence" ranks research designs based on their ability to minimize bias and establish causality [24].

Figure 1: The Hierarchy of Evidence for Biomaterials Research. Experimental designs like RCTs offer the highest internal validity for establishing cause-and-effect, while descriptive studies provide foundational knowledge but are more susceptible to bias [24].

Quantitative Research Designs and Their Evidence Level

Descriptive (Non-Experimental) Designs: These observe and describe patterns without attempting to modify the subject of study. They are foundational but occupy the lower levels of the evidence hierarchy due to limitations in establishing causality [24].

- Cross-Sectional Studies: Provide a "snapshot" in time, useful for determining prevalence. They are relatively inexpensive and convenient but cannot establish temporal relationships [24].

- Case-Control Studies: Begin with the outcome (e.g., implant failure) and look backward for exposures or risk factors. They are efficient for studying rare outcomes but prone to selection and recall bias [24].

- Cohort Studies: Follow groups of individuals (cohorts) over time, either prospectively (forward in time) or retrospectively (using historical data). They can establish temporal sequence and are used to study multiple outcomes from a single exposure [24].

Experimental Designs: These involve direct manipulation of an independent variable (e.g., a new biomaterial) under controlled conditions.

- Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs): The "gold standard" for establishing efficacy. Participants are randomly allocated to intervention or control groups, minimizing selection bias and confounding. RCTs provide the highest level of evidence for a single study [24].

- Quasi-Experimental Designs: Implement an intervention but lack full control, such as random assignment. They are used when RCTs are not feasible due to ethical or practical constraints but are more vulnerable to threats in internal validity [24].

Comparative Analysis of Biomaterials and Regulatory Strategies

The choice of biomaterial and corresponding regulatory strategy depends on the application's specific requirements, including mechanical properties, biodegradability, and bioactivity.

Table 2: Comparison of Major Biomaterial Classes and Their Applications

| Biomaterial Class | Key Characteristics | Common Applications | Regulatory Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymers [20] [25] | Versatile, tunable degradation, can be natural or synthetic. | Tissue engineering scaffolds, drug delivery systems, resorbable sutures, hydrogels. | Often Class II devices (510(k)); biocompatibility testing per ISO 10993 is critical. |

| Metals [20] | High strength, fatigue resistance, load-bearing capacity. | Orthopedic implants (joint replacements, plates), dental implants, stents. | Often Class III devices (PMA); require extensive mechanical and fatigue testing. |

| Ceramics [20] [26] | High compressive strength, bioactive, inert. | Dental implants, bone graft substitutes, joint replacements. | Bioceramics for bone contact often require clinical data demonstrating osteointegration. |

| Natural Biomaterials [20] | High biocompatibility, inherent bioactivity, biodegradable. | Wound healing, soft tissue regeneration, drug delivery. | Complex manufacturing and sourcing require rigorous validation; immunogenicity risk assessment. |

Table 3: Analysis of Regulatory Pathways for Medical Devices

| Regulatory Pathway | Risk Classification | Key Evidence Requirements | Typical Timeline | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 510(k) Clearance [21] | Class I/II (Low-Moderate) | Substantial equivalence to a predicate; bench and animal testing. | ~90 days | Lower cost, faster time-to-market. | Requires a suitable predicate; not suitable for truly novel technologies. |

| De Novo Request [21] | Class I/II (Novel, Low-Moderate) | Evidence of safety and effectiveness; risk-benefit analysis; clinical data may be needed. | 150-200 days | Creates a new regulatory classification for novel devices. | More resource-intensive than 510(k); requires demonstration of low-to-moderate risk. |

| Premarket Approval (PMA) [21] | Class III (High Risk) | Extensive scientific evidence; typically requires clinical trials; manufacturing info. | 6 months - 1 year | Suitable for novel, high-risk, life-sustaining devices. | Highest cost and longest timeline; requires intensive clinical data. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies for Biomaterials

Generating robust evidence for regulatory submissions requires adherence to standardized experimental protocols. Below are detailed methodologies for key areas of biomaterial testing.

Preclinical Biocompatibility and Safety Testing

Before human studies, biomaterials must undergo rigorous preclinical safety assessment, aligned with international standards like ISO 10993 ("Biological evaluation of medical devices") [21].

Protocol: Cytotoxicity Testing (ISO 10993-5)

- Objective: To determine if the biomaterial leaches toxic substances that cause cell death or damage.

- Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Extract the biomaterial using both polar and non-polar solvents under standardized conditions (e.g., 37°C for 24 hours).

- Cell Culture: Use established mammalian cell lines (e.g., L-929 mouse fibroblast cells) cultured in appropriate media.

- Exposure: Apply the extract to the cell monolayers, with control groups receiving only the extraction vehicles.

- Incubation and Analysis: Incubate for 24-72 hours. Assess cell viability using quantitative methods like the MTT assay, which measures mitochondrial activity, or by qualitative microscopic examination for morphological changes.

- Data Interpretation: A reduction in cell viability by more than 30% is generally considered a sign of potential cytotoxicity.

Protocol: Sensitization Testing (ISO 10993-10)

- Objective: To evaluate the potential for the biomaterial to cause an allergic contact dermatitis response.

- Methodology (Murine Local Lymph Node Assay - LLNA):

- Animal Model: Use female mice (e.g., CBA/Ca or BALB/c strains).

- Application: Apply the biomaterial extract or control substances to the dorsum of both ears daily for three consecutive days.

- Pulsing and Measurement: On day five, inject the mice with radioactive thymidine. Five hours later, drain the auricular lymph nodes and measure the incorporation of radioactivity using a beta-scintillation counter.

- Data Interpretation: A stimulation index (SI) of three or greater compared to the vehicle control indicates a sensitizing potential.

Performance and Functional Testing

Protocol: Mechanical Testing for Orthopedic Implants

- Objective: To verify that an implant can withstand physiological loads without failure.

- Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Manufacture test samples to final implant specifications.

- Testing Equipment: Use a servo-hydraulic or electromechanical test frame with environmental control (e.g., in saline at 37°C).

- Static Testing: Perform tensile, compressive, or bending tests to determine yield strength, ultimate tensile strength, and modulus of elasticity.

- Dynamic Testing: Conduct fatigue testing by applying cyclic loads representative of in vivo conditions (e.g., up to 10 million cycles for a hip stem) to determine the implant's endurance limit.

- Data Interpretation: Compare results against minimum performance standards (e.g., ASTM F382 for bone plates) or predicate devices.

Protocol: In Vivo Efficacy in an Animal Model

- Objective: To evaluate the functional performance and tissue integration of a biomaterial in a living organism.

- Methodology (Example: Critical-Sized Bone Defect Model):

- Animal Model: Use a validated species (e.g., rat, rabbit, or sheep).

- Surgical Procedure: Create a standardized defect in a long bone (e.g., femur) that will not heal spontaneously.

- Implantation: Implant the test biomaterial into the defect. Control groups may receive a standard of care (e.g., autograft) or be left untreated.

- Monitoring and Analysis: After a pre-defined period (e.g., 8-12 weeks), euthanize the animals and analyze the defect site using micro-CT for 3D bone formation, histology for tissue morphology and integration, and biomechanical testing for strength.

Visualization of the Clinical Translation Workflow

The path from concept to clinic is a multi-stage process with iterative feedback loops, where evidence generation is central to each decision point [27].

Figure 2: The Biomaterial Clinical Translation Pathway. This workflow illustrates the staged evidence generation required for regulatory approval, from initial concept to post-market monitoring, highlighting the iterative feedback from post-market data to future designs [21] [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful biomaterials research relies on a suite of specialized reagents and analytical tools to characterize properties and assess biological performance.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biomaterials Development

| Reagent/Material | Function and Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| AlamarBlue / MTT Reagents [25] | Colorimetric or fluorometric assays to quantify cell viability and proliferation in cytotoxicity and biocompatibility testing. | Provide a quantitative measure of metabolic activity; high sensitivity. |

| Primary Cells (e.g., Osteoblasts, Chondrocytes) [27] | Used in in vitro models to assess cell-material interactions in a tissue-specific context. | More physiologically relevant than cell lines; require specific culture conditions. |

| ELISA Kits | Measure specific protein secretion (e.g., inflammatory cytokines, osteogenic markers) to evaluate the host immune response or bioactivity of a material. | Highly specific and quantitative; essential for evaluating molecular-level responses. |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Reagents (e.g., glutaraldehyde, gold sputter coater) | Prepare samples for imaging the surface topography and microstructure of biomaterials, as well as cell adhesion and morphology. | Provides high-resolution, detailed images at the micro- and nano-scale. |

| PCR Assays (qRT-PCR) | Quantify gene expression levels to understand how a biomaterial influences cellular differentiation (e.g., towards osteogenic lineage) or inflammatory pathways. | Highly sensitive; allows for mechanistic studies of material-cell interactions. |

| ISO 10993 Biocompatibility Test Matrix [21] | A standardized suite of tests (e.g., for sensitization, irritation, systemic toxicity) required for regulatory submission. | Internationally recognized framework for safety assessment. |

| Spikenard extract | Spikenard Extract | |

| p-O-Methyl-isoproterenol | p-O-Methyl-Isoproterenol|Supplier | p-O-Methyl-Isoproterenol (CAS 3413-49-8), a key metabolite of Isoproterenol. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

The clinical translation of biomaterials is a complex but structured process anchored in the generation of robust, hierarchical evidence. From basic biocompatibility testing to advanced RCTs and post-market surveillance, each stage of development builds upon the previous one to establish a comprehensive safety and efficacy profile. The regulatory landscape is dynamic, with pathways like Accelerated Approval and the growing use of RWE offering opportunities to accelerate patient access, while simultaneously placing greater emphasis on post-market validation. For researchers and developers, success hinges on a strategic understanding of these evidence requirements, early engagement with regulatory bodies, and the meticulous execution of standardized experimental protocols. As the field advances with AI-driven material design and personalized biomaterials, the foundational principles of evidence-based research will remain more critical than ever in bringing safe and effective biomaterial innovations to the clinic.

Generating Robust Evidence: Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Biomaterials

In the rapidly advancing field of biomaterials research, where new materials and applications emerge constantly, the ability to distinguish truly effective innovations from merely promising ideas is paramount. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses occupy the highest position in the evidence hierarchy, providing the most reliable foundation for scientific and clinical decision-making [28] [29]. These methodologies offer a structured, transparent, and reproducible framework for synthesizing research findings, effectively distinguishing signal from noise across sometimes contradictory primary studies.

The growing complexity of biomaterials science, encompassing everything from biodegradable alloys to tissue engineering scaffolds, has generated "significant number of studies and publications as well as tremendous amount of research data" [4]. This abundance creates an urgent need for evidence-based biomaterials research (EBBR), an approach that adapts the rigorous principles of evidence-based medicine to translate raw research data into validated scientific evidence through systematic methodology [4]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of these two gold-standard evidence synthesis methods, detailing their protocols, applications, and implementation within the specific context of biomaterials research.

Core Concepts and Definitions

Systematic Reviews

A systematic review is a rigorous, structured research method that aims to identify, evaluate, and summarize all available evidence on a specific research question using a predefined, documented protocol [28] [13]. Unlike traditional narrative reviews, systematic reviews employ explicit, systematic methods to minimize bias and provide a comprehensive overview of the evidence landscape [28]. The primary purpose is to "gather all existing evidence on a particular topic, evaluate the quality of that evidence, create a transparent summary that answers a specific research question, identify gaps in current knowledge, and inform evidence-based practice and policy decisions" [28].

Meta-Analyses

A meta-analysis is a statistical procedure that combines the numerical results from multiple similar studies to calculate an overall effect size [28] [13]. Think of it as a "study of studies" that uses statistical methods to find the signal amid the noise of individual research findings [28]. While a systematic review asks, "What does all the evidence say?", a meta-analysis asks more specifically, "What is the mathematical average effect across all studies, and how confident can we be in this number?" [28]. A meta-analysis typically builds upon a systematic review foundation but requires additional steps including statistical pooling and weighting of studies based on their precision [28].

Key Differences Between Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

While systematic reviews and meta-analyses are often mentioned together, they serve distinct purposes and employ different methodologies. The table below summarizes their key differences:

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

| Feature | Systematic Review | Meta-Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Comprehensive review that identifies, evaluates, and synthesizes all available evidence on a specific question [28] | Statistical technique that combines results from multiple similar studies to calculate an overall effect [28] |

| Primary Purpose | To gather and critically appraise all relevant research [28] | To provide a precise mathematical estimate of effect [28] |

| Nature | Primarily qualitative synthesis [28] | Primarily quantitative analysis [28] |

| Study Types Included | Can include diverse study designs [28] | Requires studies with compatible numerical data [28] |

| Analysis Method | Narrative synthesis, thematic analysis [28] | Fixed or random effects models, meta-regression [28] |

| Output Format | Text summary, evidence tables, narrative synthesis [28] | Forest plots, pooled effect sizes, confidence intervals [28] |

| Typical Conclusion | "The evidence suggests that..." [28] | "The pooled effect size is X (95% CI: Y-Z)" [28] |

A key conceptual relationship is that a meta-analysis typically builds upon a systematic review but requires the additional step of statistical pooling. All meta-analyses should be based on a systematic review, but not all systematic reviews include a meta-analysis [28] [13]. A meta-analysis is only possible when the included studies report compatible statistical outcomes that can be mathematically combined [28].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Standards

Conducting high-quality evidence synthesis requires adherence to strict methodological standards. The following workflow outlines the key stages, which incorporate both systematic review and potential meta-analysis components:

Evidence Synthesis Workflow

Protocol Development and Registration

The process begins with developing and registering a detailed protocol, which serves as a research plan that minimizes bias and enhances transparency [29] [30]. The protocol should specify the research question, inclusion/exclusion criteria, search strategy, data extraction methods, and planned synthesis approaches [29]. Registration on platforms like PROSPERO protects against duplicate publication and reduces publication bias [30].

Formulating the Research Question

A well-structured research question is fundamental. In biomaterials research, frameworks like PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome) or its extended versions are commonly used [13] [30]. For example, in evaluating a new biodegradable material for orthopaedic implants:

- Population: Patients with long bone fractures requiring internal fixation

- Intervention: Biodegradable low-entropy alloy implants

- Comparator: Traditional non-biodegradable medium-entropy alloy implants

- Outcome: Fracture healing rate, implant degradation rate, adverse events [16]

Comprehensive Literature Search

A systematic search across multiple databases is essential to capture all relevant evidence. For biomaterials topics, this typically includes PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, and specialized databases like Cochrane Library [13] [31]. The search strategy should combine controlled vocabulary (e.g., MeSH terms) with free-text keywords and include "gray literature" to reduce publication bias [13] [31]. Tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley help manage references and remove duplicates [13].

Study Selection and Data Extraction