Comparative Analysis of Biomaterial-Based Drug Delivery Systems: Efficiency, Applications, and Future Directions

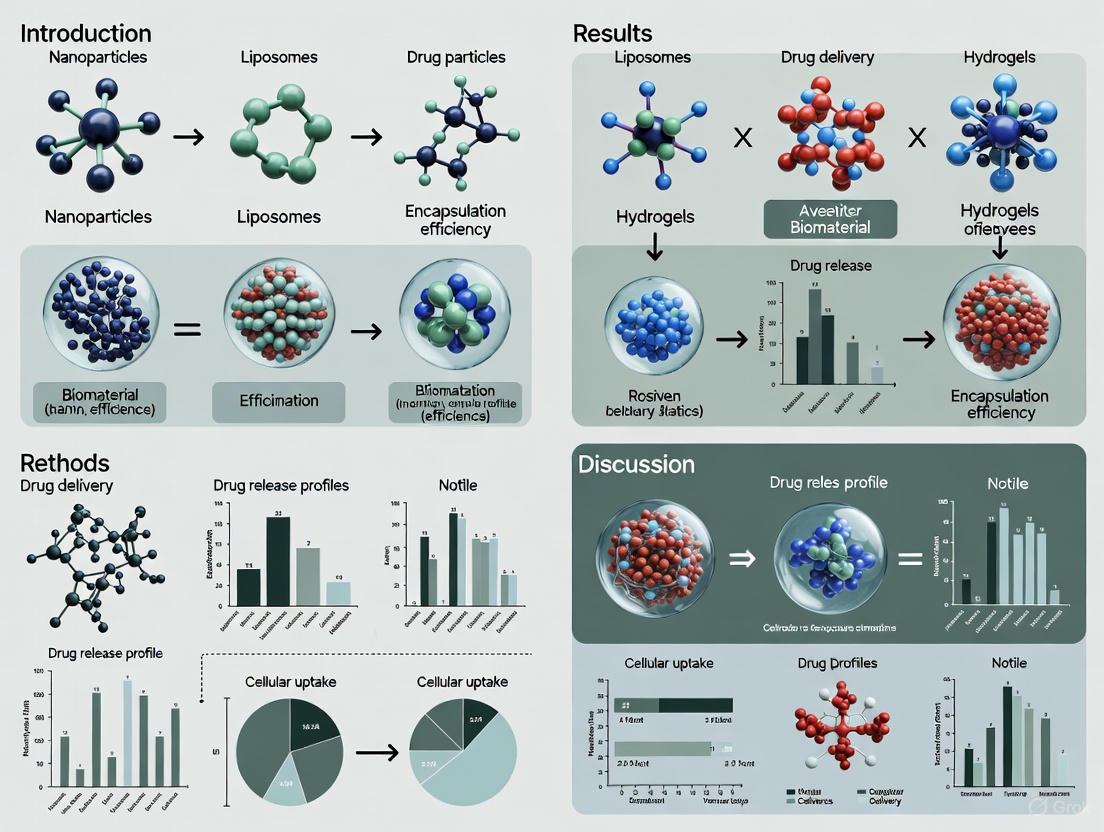

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of the efficiency of various biomaterial-based drug delivery systems (DDS) for researchers and drug development professionals.

Comparative Analysis of Biomaterial-Based Drug Delivery Systems: Efficiency, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of the efficiency of various biomaterial-based drug delivery systems (DDS) for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of key biomaterial classes, including biobased nanomaterials, hydrogels, and biodegradable polymers. The analysis covers methodological advances in their application across diverse medical fields such as cancer therapy, CNS disorders, and regenerative medicine. The review systematically addresses major translational challenges, including scalability, biocompatibility, and overcoming biological barriers, while presenting optimization strategies. A quantitative comparison of system performance metrics—such as targeting precision, stability, controlled release, and patient compliance—offers a validated framework for material selection. By synthesizing current trends and data, this work aims to guide the development of next-generation, efficient, and clinically viable drug delivery platforms.

Biomaterials Unveiled: Exploring the Core Classes and Properties for Advanced Drug Delivery

The field of biomaterials has undergone a profound evolution, transitioning from simple, biocompatible passive structures to dynamic, intelligent systems capable of sophisticated interactions with biological environments. In modern pharmaceutical sciences, biomaterials are engineered substances designed to direct, through controlled interactions with biological systems, the therapeutic course of diagnostic or treatment regimens. This progression is largely driven by the limitations of conventional drug delivery, which often struggles with poor bioavailability, systemic toxicity, and an inability to target specific tissues effectively [1]. The contemporary definition of a biomaterial now encompasses a wide spectrum of substances—from naturally derived, sustainable polymers to synthetic, "smart" systems that respond to physiological stimuli. These advanced materials are foundational to creating targeted drug delivery systems that enhance therapeutic efficacy while minimizing adverse side effects, thereby revolutionizing the management of complex diseases such as cancer, diabetes, and neurological disorders [2] [1] [3]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the performance of various biomaterial systems, underpinned by experimental data, to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Comparative Analysis of Key Biomaterial Systems

The performance of drug delivery systems is critically dependent on the selection of biomaterials, which dictate properties such as drug release kinetics, targeting efficiency, and biocompatibility. The table below provides a structured comparison of three major classes of biomaterials used in advanced drug delivery applications.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Biomaterial Systems for Drug Delivery

| Biomaterial Class | Key Composition | Drug Loading & Release Mechanism | Targeting Efficiency & Key Findings | Reported Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymeric Nanoparticles (PNPs) [4] | PLGA, Chitosan, Poly(lactic acid) | High drug loading capacity; Controlled release via polymer degradation and diffusion [4]. | Passive (EPR effect): High Active (with ligands): Enhanced→ Surface modification with PEG reduces non-specific tissue interaction; Ligands like antibodies enable specific tumor cell targeting [4]. | Potential toxicity of some polymers; Batch-to-batch consistency during scale-up; Regulatory hurdles for novel polymers [4] [1]. |

| Stimuli-Responsive Hydrogels [2] | Chitosan, PVA-CMC, PNIPAM | Fast-gelling at body temperature; Swelling/degradation or dynamic chemical bonds control release in response to pH, temperature, or enzymes [5] [2]. | Temporal/Spatial Control: High→ In a periodontitis model, a thermosensitive chitosan hydrogel provided a localized microenvironment for bone regeneration, reducing inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6) and upregulating osteogenic markers (Collagen I, Runx2) [2]. | Limited mechanical strength for some applications; Response rate to stimuli can be slow; Potential for premature release. |

| Advanced Lipid & Polymeric Nanocarriers [6] [1] | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs), PLGA-RES, PO3Gn-b-PLA Triblock Copolymers | Encapsulation in lipid core or polymeric matrix; Release triggered by microenvironment (e.g., acidic pH) or external stimuli (e.g., NIR light) [6] [1]. | Tumor Targeting (e.g., with folate): Significant→ A bioinspired nano-prodrug (BiNp) with folic acid showed significant tumor-targeting and uptake, releasing active components in acidic tumor microenvironments to promote apoptosis [4]. → PLGA-RES nanocomposites significantly improved oocyte viability during cryopreservation by combating oxidative stress [2]. | Lipid-based systems may have stability issues; Immunogenicity concerns with PEG [7]; Complex manufacturing for some copolymer architectures. |

Experimental Protocols for Biomaterial Evaluation

To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of research in this field, standardized experimental protocols are essential. The following section details key methodologies for synthesizing and characterizing advanced biomaterial systems.

Synthesis of Bio-based Triblock Copolymer Nanoparticles

The development of sustainable and biocompatible polymers is a key research focus. The following protocol, adapted from Tinajero DÃaz et al., describes the synthesis of fully bio-based poly(lactide)-b-poly(1,3-trimethylene glycol)-b-poly(lactide) (PLA-b-PO3Gn-b-PLA) triblock copolymers, which are promising alternatives to PEG-based systems [7].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Triblock Copolymer Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Poly(trimethylene glycol) (PO3Gn) | Bio-based macroinitiator; forms the central, hydrophilic block of the copolymer, imparting "stealth" properties. |

| L-lactide or rac-lactide | Monomer; ring-opens to form the outer, hydrophobic polyester blocks (PLA) that influence crystallinity and degradation. |

| Stannous octoate (Sn(Oct)â‚‚ | Catalyst; accelerates the ring-opening polymerization of lactide. |

| Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) | Stabilizer; used in the emulsion/solvent-evaporation method to form stable nanoparticles in water. |

| Dichloromethane (DCM) | Solvent; dissolves the copolymer for the nanoparticle self-assembly process. |

Detailed Workflow:

- Polymerization Setup: In a three-neck round-bottom flask equipped with a mechanical stirrer, nitrogen inlet, and vacuum outlet, combine the PO3Gn macroinitiator and L-lactide or rac-lactide at a predetermined molar feed ratio [7].

- Purging and Catalyst Addition: Purge the system with nitrogen. Heat the mixture to 120°C under vacuum for several minutes. Subsequently, increase the temperature to 180°C and add a catalytic amount of stannous octoate to initiate the ring-opening polymerization (ROP) [7].

- Bulk Polymerization: Allow the reaction to proceed under a nitrogen atmosphere at 180°C for a specified time until the desired molecular weight is achieved [7].

- Nanoparticle Formation via Self-Assembly: Purify the resulting PLA-b-PO3Gn-b-PLA triblock copolymer. Using the emulsion/solvent-evaporation method, dissolve the copolymer in dichloromethane. Emulsify this organic solution in an aqueous solution containing poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) as a stabilizer. Finally, evaporate the organic solvent to form solid, spherical nanoparticles with hydrodynamic diameters typically ranging from 95 to 158 nm [7].

Diagram 1: Triblock Copolymer Synthesis Workflow

Development and Testing of a Smart Theranostic System

The integration of diagnostics and therapy, known as theranostics, represents a frontier in personalized medicine. The following protocol is based on the work of Park et al., who developed a bifunctional tumor-targeting bioprobe [6].

Detailed Workflow:

- Bioprobe Fabrication: Synthesize or source a biocompatible nanoparticle core (e.g., gold nanorods, silica nanoparticles, or water-dispersible upconversion nanoparticles). Functionalize the nanoparticle surface with two key components: a) a tumor-targeting ligand (e.g., an antibody or peptide) for specific accumulation, and b) a combination of therapeutic and imaging agents, such as a photosensitizer for photodynamic therapy (PDT) and a near-infrared (NIR) fluorescent dye [6].

- In Vitro Validation: Incubate the bioprobe with target cancer cells and control cells. Use NIR fluorescence imaging to confirm specific cellular uptake and accumulation. Subsequently, apply a specific light stimulus (e.g., NIR laser) to activate the photosensitizer, generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) for photodynamic therapy and heat for photothermal therapy (PTT). Measure cell death to assess therapeutic efficacy [6].

- In Vivo Efficacy and Imaging: Administer the bioprobe to animal models with established tumors. Employ non-invasive NIR fluorescence imaging to track the bioprobe's biodistribution and real-time accumulation at the tumor site via the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect and active targeting. Apply targeted irradiation to trigger the therapeutic effects and monitor tumor regression over time. The system is designed for complete decomposition and clearance post-treatment [6].

Diagram 2: Smart Theranostic System Workflow

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The next wave of innovation in biomaterials is being shaped by the convergence of materials science with digital technologies and a heightened focus on sustainability.

- AI-Driven Biomaterials Design: Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are revolutionizing the development of new biomaterials. These technologies can analyze vast datasets to predict material properties, optimize nanoparticle design for specific drug release profiles, and even simulate nanoparticle degradation and interactions within the body. This significantly accelerates the discovery and optimization process, paving the way for highly personalized medicine approaches [4] [1] [8].

- Sustainable and Bio-based Polymers: The shift towards a circular economy is driving research into fully bio-based and biodegradable polymers. Examples include triblock copolymers of poly(lactide) and poly(trimethylene glycol) (derived from glucose fermentation), which serve as promising, potentially less immunogenic alternatives to conventional PEG in drug delivery formulations [7]. The use of natural extracts in hydrogels also aligns with this trend [2].

- Advanced Nanocarriers and Microrobots: The frontier of drug delivery is expanding to include sophisticated systems like magnetically propelled hydrogel microrobots for penetrating tumor sites [2] and exosome-based therapies that leverage the body's own intercellular communication systems for regenerative medicine [2]. The success of lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) in mRNA vaccine delivery has further validated the potential of nanocarriers for complex biologics [1].

The landscape of biomaterials for drug delivery is rich and diverse, spanning from sustainable biobased polymers to intelligently responsive smart systems. This comparative analysis demonstrates that while polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) offer high versatility and drug loading capacity, stimuli-responsive hydrogels excel in providing localized and temporally controlled release. Meanwhile, advanced nanocarriers, including lipid nanoparticles and targeted theranostic probes, show unparalleled potential for precision delivery of complex therapeutics. The choice of biomaterial system is ultimately dictated by the specific therapeutic application, desired release profile, and targeting requirements. As the field advances, the integration of AI-driven design and a commitment to sustainable material sources will further empower researchers to develop next-generation, personalized drug delivery solutions that enhance therapeutic efficacy and patient outcomes.

In the evolving landscape of drug delivery and regenerative medicine, the selection of biomaterials—ranging from natural polymers like polysaccharides and proteins to synthetic polymeric carriers—is paramount for designing effective therapeutic systems. These materials form the foundational scaffold of nano-drug delivery systems (NDDS), influencing critical parameters such as biocompatibility, drug loading, release kinetics, and targeted delivery. Natural polymers, derived from biological sources, offer inherent biocompatibility and bioactivity, whereas synthetic polymers provide tunable mechanical properties and predictable degradation profiles. This comparative guide objectively analyzes the performance of these material classes, drawing on experimental data to inform researchers and drug development professionals. By examining their distinct advantages, limitations, and applications within a structured framework, this review aims to support the rational design of next-generation drug delivery platforms.

Comparative Analysis of Material Properties

The fundamental differences between natural and synthetic biomaterials directly influence their performance in drug delivery applications. The table below summarizes key properties based on experimental data.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Natural and Synthetic Biomaterials for Drug Delivery

| Property | Natural Polysaccharides | Natural Proteins | Synthetic Polymers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biocompatibility | Excellent; low toxicity and immunogenicity [9] | Excellent; high cell recognition [10] | Variable; can induce inflammatory responses [11] |

| Biodegradability | Enzymatically degradable; products are safe [9] | Highly biodegradable (e.g., collagen, silk) [10] | Tunable; but some by-products can be acidic (e.g., PLA, PLGA) [11] |

| Mechanical Strength | Generally moderate; often requires cross-linking [12] | Outstanding and diverse (e.g., high toughness in silk) [10] | Highly tunable and typically robust [11] [13] |

| Drug Loading Efficiency | High for various drugs; can be charge-dependent [12] | High; depends on protein structure and interactions [10] | High; can be engineered for specific drugs [4] |

| Release Kinetics | Can be responsive to pH, enzymes, or redox [9] | Can be controlled by cross-linking and degradation [10] | Predictable, diffusion-controlled release is common [11] |

| Targeting Capability | Inherent (e.g., lectin recognition by β-glucan) [14] | Can be functionalized with targeting ligands [10] | Requires surface functionalization (e.g., PEGylation, ligands) [4] |

| Cost & Scalability | Variable; sourcing and purification can be challenges [9] | Often high cost; batch-to-batch variability [10] | Good scalability and consistent quality [11] |

Experimental Data and Performance in Drug Delivery

Quantitative Formulation Screening Data

High-throughput screening of polysaccharide-based nanoparticles reveals how material selection impacts critical formulation parameters. The following table compiles experimental results from a combinatorial screen of cationic agents formulated with an anionic phosphorylated β-glucan (EEPG) framework for siRNA delivery [14].

Table 2: Experimental Screening Data for Polysaccharide-Based Nanoformulations [14]

| Cationic Material Category | Example Compounds | Optimal N/P Ratio for Formation | siRNA Encapsulation Efficiency (EE%) | Hydrodynamic Diameter (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cationic Polymers | Chitosan, Polyethyleneimine (PEI) | ~1/1 to 15/1 | 30-90% (PEI > Chitosan) | < 200 nm |

| Cationic Lipids | Lipid 2, Lipid 10 | < 0.04/1 to 15/1 | >80% (for Lipid 2/10 at N/P 15/1) | < 200 nm |

| Cell-Penetrating Peptides | K9, KALA, Penetratin | ~1/1 to 20/1 | >80% (at N/P 20/1) | < 200 nm |

| Small Molecules | Spermine | ~30/1 | >80% (comparable to PEI) | < 200 nm |

Experimental Drug Release Profiles

Comparative release studies using model drugs provide performance insights across different polymer classes. The data below summarizes findings from a study investigating ibuprofen (IBU) release from various polysaccharide-based hydrogels [12].

Table 3: Drug Release Kinetics of Ibuprofen from Polysaccharide Hydrogels [12]

| Hydrogel Type (Polymer) | Charge | Cumulative Release (%) | Release Kinetics Model | Key Influencing Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium Carboxymethyl Cellulose (NaCMC) | Anionic | High | Fickian Diffusion | Swelling and electrostatic repulsion |

| Chitosan (CS) | Cationic | Low | Non-Fickian (Anomalous) transport | Electrostatic attraction to anionic drug |

| Tragacanth Gum (TRG) | Anionic | Moderate | Not Specified | Complex hetero-polysaccharide structure |

| Carrageenan (CRG) | Anionic | Moderate | Not Specified | Sulfated group interactions |

| Chitosan-Neutral Polymer Combination | Cationic/Neutral | Prolonged | Sustained Release | Modified diffusion path |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

High-Throughput Screening of Polysaccharide Nanoformulations

This protocol, adapted from a 2024 Nature Communications study, details a robotic-assisted screen for identifying optimal polysaccharide-based siRNA carriers [14].

- Primary Materials: Anionic polysaccharide (e.g., EEPG), diverse cationic compound library (polymers, lipids, peptides, small molecules), siRNA, microfluidics workstation, dynamic light scattering (DLS) instrument.

- Methodology:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare an aqueous solution of the anionic polysaccharide (EEPG) as the outer phase. Prepare solutions of cationic compounds in suitable buffers as the inner phase.

- Microfluidics-assisted Nanoprecipitation: Utilize a high-throughput microfluidics workstation with a co-flow device. Fix the flow conditions for the outer phase (EEPG). Systematically vary the flow rates of the inner phase (cationic compounds) to achieve a wide range of weight or N/P (Nitrogen/Phosphate) ratios.

- Automated Size and Formation Analysis: Direct the output from the microfluidic device to an integrated, automatic DLS system. Use the average derived counting rate (over 6000 kcps) as a primary indicator of successful nanoparticle formation. Record the hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity index (PDI) for each formulation.

- siRNA Encapsulation Assay: For formulations with optimal physical characteristics (small size, PDI < 0.2), mix with siRNA at set N/P ratios (e.g., 15/1 and 20/1). Use a Ribogreen assay to quantify encapsulation efficiency (EE%). The fluorescent dye's signal is quenched upon encapsulation, allowing calculation of unencapsulated siRNA.

- Key Analysis: The optimal candidate, termed GluCARDIA, was identified through this screen and demonstrated efficient cardiac siRNA delivery in a murine model of myocardial ischemic/reperfusion injury [14].

Comparative Hydrogel Drug Release Kinetics

This standard protocol evaluates the drug release profiles from polymer-based hydrogels, as used in studies comparing polysaccharide excipients [12].

- Primary Materials: Polymer (e.g., Chitosan, NaCMC, Carrageenan), model drug (e.g., Ibuprofen), dissolution apparatus, Franz diffusion cells, HPLC system.

- Methodology:

- Hydrogel Preparation: Dissolve the polysaccharide in an appropriate solvent (e.g., aqueous acidic solution for chitosan). Incorporate the model drug uniformly into the polymer solution. Induce gelation via physical (e.g., pH change) or chemical (e.g., cross-linker) methods to form the drug-loaded hydrogel.

- In Vitro Release Study: Place a precise weight of the drug-loaded hydrogel in a receptor medium (e.g., phosphate buffer saline, PBS) under sink conditions. Maintain the system at a constant temperature (e.g., 37°C) with continuous agitation.

- Sample Collection and Analysis: At predetermined time intervals, withdraw aliquots from the receptor medium and replace with fresh medium to maintain sink conditions. Analyze the drug concentration in the aliquots using a validated analytical method (e.g., HPLC or UV-Vis spectrophotometry).

- Kinetic Modeling: Fit the cumulative drug release data to various mathematical models (e.g., Zero-order, First-order, Higuchi, Korsmeyer-Peppas) to determine the primary release mechanism.

- Key Analysis: The study found that cationic chitosan effectively prolonged the release of anionic ibuprofen, whereas anionic hydrogels like NaCMC showed higher, diffusion-driven release [12].

Visualization of Workflows and Mechanisms

High-Throughput Screening Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the automated, step-wise screening process for identifying optimal polysaccharide-based nanoformulations.

High-Throughput Screening Workflow for Optimal Nanoformulations

Mechanism of Targeted Drug Delivery

This diagram outlines the key mechanisms by which engineered polymeric carriers, particularly polysaccharide-based nanoparticles, achieve targeted drug delivery.

Mechanisms of Targeted Drug Delivery by Polymeric Carriers

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This section details key materials and their functions for researchers developing and evaluating natural and synthetic polymeric carriers.

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Biomaterial-Based Drug Delivery Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cationic Polysaccharides | Form polyelectrolyte complexes with nucleic acids; mucoadhesive properties. | Chitosan, Chitosan Oligomer (CS-O) [14] [12] |

| Anionic Polysaccharides | Ionic gelation framework; inherent targeting; responsive release. | Phosphorylated β-glucan (EEPG), Alginate, Hyaluronic Acid, NaCMC [9] [14] [12] |

| Cationic Lipids | Enhance encapsulation of anionic drugs/siRNA; improve cellular uptake. | Lipid 2, Lipid 10 (from combinatorial screens) [14] |

| Cell-Penetrating Peptides (CPPs) | Improve cellular internalization of nanoparticles. | K9, KALA, Penetratin, Transportan [14] |

| Cross-linkers | Stabilize hydrogels and nanoparticles; control degradation and release. | Genipin (natural), Glutaraldehyde, N,N'-Methylenebis(acrylamide) (MBA) [12] |

| Model Therapeutic Agents | For encapsulation and release studies. | Ibuprofen (small molecule), siRNA (genetic), Doxorubicin (chemotherapy) [14] [12] |

| Characterization Instruments | Determine size, charge, stability, and drug release profile. | Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), HPLC, Franz Diffusion Cells [11] [14] [12] |

| Piperidine-3,3-diol | Piperidine-3,3-diol|High-Purity Research Chemical | Piperidine-3,3-diol is a versatile diol-substituted piperidine building block for pharmaceutical and organic synthesis. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Lithium metagallate | Lithium metagallate, MF:GaLiO2, MW:108.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In the development of advanced drug delivery systems, the selection of biomaterials is governed by three critical performance metrics: biocompatibility, biodegradability, and functionalization. These properties collectively determine the safety, efficacy, and temporal control of therapeutic agent delivery. Biocompatibility ensures minimal adverse immune reactions and toxicity, biodegradability governs the rate of material breakdown and drug release kinetics, and functionalization enhances targeting capabilities and modulates interactions with biological systems. This guide provides a comparative analysis of prominent biomaterial systems, supported by experimental data and standardized testing methodologies, to inform rational material selection for specific therapeutic applications.

Comparative Analysis of Biocompatibility

Biocompatibility assessment evaluates the host response to a biomaterial, including its toxicity, immunogenicity, and potential to cause allergic reactions. Rigorous testing is required by regulatory bodies before clinical application [15] [16].

Quantitative Biocompatibility Metrics

Table 1: Standardized Biocompatibility and Toxicity Profiles of Selected Biomaterials

| Material | Test Model | Key Metrics | Results | Tolerated Dose/Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles (MSNs) [17] | Female nude mice (in vivo) | Serology, Hematology, Histopathology | No acute toxicity; Mild, transient elevation of liver enzymes (AST) at higher doses; No significant body weight change or histological lesions. | Up to 50 mg/kg (IV) |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) [15] [16] | Immunoassay (in vitro) | Immunogenicity (Anti-PEG antibodies) | Presence of anti-PEG antibodies can alter nanocarrier biodistribution and trigger hypersensitivity. | Varies by formulation; immunogenicity is a key concern. |

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) [15] [16] | Cell culture & in vivo | Inflammatory response, Histocompatibility | Can provoke inflammatory reactions in vivo; modification with short-chain PEG enhances histocompatibility. | Dependent on application and modification. |

Experimental Protocols for Biocompatibility Assessment

- In Vivo Systemic Toxicity Profile (e.g., for MSNs) [17]:

- Administration: Intravenous injection of material suspended in saline via the tail vein in female nude mice. Doses are typically administered multiple times over a period (e.g., twice per week for 14 days).

- Monitoring: Daily observation for body weight change, visible signs of infection, ascites, grooming, and mobility. A Body Condition Scoring (BCS) system is used.

- Serological and Hematological Analysis: Blood collection at defined intervals (e.g., day 2 and day 14) for Complete Blood Count (CBC) and liver enzyme tests (AST, ALT).

- Histopathological Examination: Post-sacrifice, major organs (liver, spleen, kidney, heart, etc.) are harvested, sectioned, and examined for gross or pathological abnormalities.

- Immunogenicity Testing (e.g., for PEG) [15] [16]: Detection of pre-existing or induced antibodies via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or similar immunoassays. The impact on nanocarrier stability and biodistribution is assessed in relevant biological models.

Biocompatibility Assessment Workflow

Comparative Analysis of Biodegradability

Biodegradation involves the breakdown of materials into simpler substances through biological activity, primarily via hydrolysis or enzymatic action. The degradation rate is a crucial parameter for controlling drug release profiles [15].

Mechanisms and Kinetics of Biodegradation

Table 2: Biodegradation Mechanisms and Influencing Factors for Common Polymers

| Polymer | Primary Degradation Mechanism | Key Influencing Factors | Rate Modulation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) [15] | Hydrolysis of ester bonds | Temperature, Humidity, Catalysts | Hydrolysis rate increased by 30-50% with a 50°C temperature rise under >90% humidity. |

| Starch-based Polymers [15] | Enzymatic cleavage of α-1,4-glycosidic linkages | Enzymes (α-amylase, β-glucosidase), Temperature, Humidity | Degradation rate accelerates when temperature rises from 30°C to 50°C at >80% humidity. |

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) [18] | Hydrolytic cleavage of ester bonds | Crystallinity, Implant Environment, Blending | Blending with PLA in 3D printed scaffolds tailors degradation rate and flexibility [15]. |

Experimental Protocols for Degradation Profiling

- In Vitro Hydrolytic Degradation [15]:

- Sample Immersion: Incubate pre-weighed polymer samples (e.g., films, scaffolds) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a specific pH (e.g., 7.4) and temperature (commonly 37°C).

- Mass Loss Monitoring: At predetermined time points, remove samples, dry them thoroughly, and measure the mass loss. The percentage of mass loss is calculated as (Initial Dry Mass - Current Dry Mass) / Initial Dry Mass × 100.

- Media Analysis: Analyze the immersion media for degradation byproducts using techniques like Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) to track changes in molecular weight.

- Enzymatic Degradation Assay [15]:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a buffer solution containing a specific, purified enzyme relevant to the polymer (e.g., lipase for PCL, proteinase K for PLA).

- Incubation and Sampling: Incubate the polymer sample in the enzyme solution under controlled conditions (e.g., 37°C). Monitor mass loss or molecular weight change over time as in the hydrolytic test.

- Kinetics Analysis: Compare the degradation rate against a control sample (without enzyme) to quantify the enzymatic contribution.

Biodegradation Pathways and Modulation

Comparative Analysis of Surface Functionalization

Surface functionalization enhances the bioactivity, targeting, and interfacial properties of biomaterials. It is particularly vital for synthetic polymers like PCL, which are inherently bioinert [18].

Performance of Functionalization Techniques

Table 3: Comparison of Surface Functionalization Methods for Polycaprolactone (PCL) Scaffolds

| Functionalization Method | Target Material/Application | Key Experimental Findings | Impact on Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| TiCaPCON Coating (Magnetron Sputtering) [18] | PCL for Bone Tissue Regeneration | Enhanced MC3T3-E1 osteoblast cell adhesion/proliferation; Promoted formation of Ca-based mineralized layer in Simulated Body Fluid (SBF). | Induces bioactivity, improves bone regeneration potential. |

| COOH Plasma Polymerization [18] | PCL for Skin Repair | Improved IAR-2 epithelial cell adhesion and proliferation. | Enhances hydrophilicity and cytocompatibility for soft tissue applications. |

| PEGylation (Short-chain PEG) [15] [16] | PLA-based Microspheres | Reduced inflammatory reaction in vivo; Enhanced histocompatibility. | Improves stealth properties, reduces immune recognition. |

Experimental Protocols for Functionalization and Bioactivity Testing

- Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Copolymerization for COOH Groups [18]:

- Setup: Place electrospun PCL nanofibers in a plasma reactor.

- Process: Introduce precursor gases, typically COâ‚‚ and Câ‚‚Hâ‚„, into the chamber. Apply atmospheric pressure plasma to initiate copolymerization.

- Result: A thin, COOH-rich polymer layer is deposited on the PCL surface, increasing hydrophilicity.

- Magnetron Sputtering of TiCaPCON Film [18]:

- Target: Use a composite TiC–CaO–Ti₃POₓ target.

- Deposition: Place PCL scaffolds in a magnetron sputtering system (e.g., "UNICOAT 900"). Sputter the target in an atmosphere of Ar and Nâ‚‚ gases (e.g., 250 sccm Ar, 25 sccm Nâ‚‚) at an accelerating voltage of 450 V for a set duration (e.g., 10 min).

- In Vitro Bioactivity Assessment via SBF Immersion [18]:

- SBF Preparation: Prepare simulated body fluid (1× SBF) with ion concentrations nearly equal to human blood plasma.

- Immersion: Immerse the functionalized scaffolds in SBF at 37°C for a prolonged period (e.g., 21 days).

- Analysis: Post-immersion, characterize the scaffold surface using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy to detect the formation of a calcium phosphate (apatite) layer, indicative of bioactivity.

Surface Functionalization and Evaluation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

This section details key reagents, materials, and instruments essential for the experimental work discussed in this guide.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biomaterial Performance Evaluation

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) [18] | In vitro assessment of bioactivity and biomineralization potential. | Solution with ion concentration similar to human blood plasma. |

| Electrospinning Apparatus [18] | Fabrication of polymer nanofiber scaffolds that mimic the extracellular matrix. | e.g., Nanospider NSLAB 500. |

| Magnetron Sputtering System [18] | Deposition of thin, uniform, and adhesive bioactive coatings on polymers. | e.g., "UNICOAT 900" for TiCaPCON coating. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) [15] [16] | Characterization of thermal properties of polymers (e.g., glass transition, melting point). | Informs processing conditions and stability. |

| Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) [15] [16] | Measurement of thermal stability and decomposition profile of materials. | |

| Enzymes (e.g., Lipases, Proteases) [15] | Study of enzymatic degradation pathways of biodegradable polymers. | Enzyme type selected based on polymer chemistry. |

| Cell Lines (e.g., MC3T3-E1, IAR-2) [18] | In vitro cytocompatibility and cell-material interaction studies. | MC3T3-E1 (osteoblasts), IAR-2 (epithelial cells). |

| Composite Sputtering Target (TiC–CaO–Ti₃POₓ) [18] | Source for depositing TiCaPCON bioactive films via magnetron sputtering. | Produced by self-propagating high-temperature synthesis. |

| Precursor Gases (COâ‚‚, Câ‚‚Hâ‚„) [18] | Used in plasma copolymerization to create COOH-rich functional surfaces. | |

| Anthra[2,3-b]thiophene | Anthra[2,3-b]thiophene, CAS:22108-55-0, MF:C16H10S, MW:234.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 6-Hexadecenoic acid | 6-Hexadecenoic acid, MF:C16H30O2, MW:254.41 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The field of controlled drug delivery has undergone a revolutionary transformation, evolving from simple sustained-release formulations to sophisticated, intelligently targeted systems. This evolution represents a paradigm shift from one-size-fits-all release kinetics to precision medicine approaches that deliver therapeutics with spatial and temporal control. At the forefront of this transformation are poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) based systems, which have served as the foundational backbone for controlled release technologies, and stimuli-responsive platforms that represent the next generation of intelligent drug delivery.

Traditional PLGA systems have demonstrated remarkable success by providing predictable, tunable drug release profiles through biodegradation kinetics. These systems leverage the well-understood hydrolysis of ester linkages in the PLGA backbone to release encapsulated therapeutics over periods ranging from days to months. The durability of PLGA as a drug delivery vehicle stems from its excellent biocompatibility, predictable erosion rates, and regulatory acceptance. However, the inherent passive diffusion mechanism and degradation-controlled release lack the responsiveness to dynamic physiological environments required for optimal therapeutic outcomes in complex disease states.

Stimuli-responsive platforms have emerged to address this critical limitation, integrating smart materials capable of sensing and responding to specific pathological triggers. These advanced systems bridge the gap between conventional sustained release and active pathological targeting, offering enhanced precision through both endogenous and exogenous activation mechanisms. The integration of PLGA with these responsive elements has created a new class of hybrid systems that merge the proven safety and controlled release properties of PLGA with the targeted activation capabilities of stimuli-responsive technologies.

This comparative analysis examines the technological evolution from conventional PLGA systems to advanced stimuli-responsive platforms, providing researchers with a systematic evaluation of their respective drug delivery efficiencies, experimental methodologies, and performance characteristics across key pharmaceutical metrics.

Material Foundations and System Architectures

PLGA-Based Controlled Release Systems

Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) has established itself as one of the most extensively utilized biodegradable polymers in controlled drug delivery, primarily due to its tunable physicochemical properties and excellent safety profile. The degradation mechanism of PLGA occurs through hydrolysis of ester bonds in an aqueous environment, generating lactic acid and glycolic acid as metabolic byproducts that enter the Krebs cycle and are eventually eliminated as carbon dioxide and water [19]. This biodegradation pathway minimizes systemic toxicity and underpins the regulatory acceptance of PLGA for numerous pharmaceutical applications.

The drug release profile from PLGA systems is governed by a complex interplay of polymer characteristics, including molecular weight, lactide-to-glycolide (L:G) ratio, blockiness, and end-group functionality. These parameters collectively influence hydration rates, degradation kinetics, and consequently, release duration. Specifically, higher molecular weight PLGA, increased lactide content, and ester end caps correlate with prolonged degradation times and extended release profiles [19]. This tunability has enabled the development of PLGA-based formulations spanning various administration routes, including injectable microspheres, implants, and nanoparticles.

The fabrication of PLGA nanoparticles typically employs emulsion-solvent evaporation, nanoprecipitation, or double-emulsion methods, with the selection dependent on the hydrophilicity or hydrophobicity of the encapsulated therapeutic. The double-emulsion technique (w/o/w) has proven particularly effective for hydrophilic compounds, allowing for high encapsulation efficiency through the formation of aqueous compartments within the polymeric matrix [20]. These methodological innovations have positioned PLGA as a versatile platform for delivering diverse therapeutic agents, including small molecules, proteins, peptides, and nucleic acids.

Stimuli-Responsive Platform Designs

Stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems represent a sophisticated advancement beyond conventional PLGA platforms, incorporating materials capable of sensing and responding to specific pathological cues or external triggers. These systems are broadly categorized as endogenous or exogenous responsive platforms, with some advanced architectures capable of responding to multiple stimuli simultaneously.

Endogenous stimuli-responsive systems leverage pathological abnormalities in the disease microenvironment, such as decreased pH, elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS), overexpression of specific enzymes, or redox potential gradients. For instance, pH-responsive systems exploit the acidic tumor microenvironment (pH ~6.5-7.0) or endosomal compartments (pH ~5.0-6.0) to trigger drug release through acid-labile bond cleavage or protonation-induced structural changes [21] [22]. Similarly, enzyme-responsive systems utilize pathological overexpression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), hyaluronidases, or proteases to degrade specific peptide sequences or polysaccharide components, thereby releasing therapeutic payloads at the target site.

Exogenous stimuli-responsive systems respond to externally applied triggers such as magnetic fields, light, or ultrasound, offering precise spatiotemporal control over drug release. Magnetic-responsive platforms typically incorporate superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (e.g., maghemite, γ-Fe₂O₃) that generate localized heat under alternating magnetic fields, simultaneously enabling hyperthermia therapy and triggering drug release from thermosensitive carriers [21]. Light-responsive systems employ photosensitizers or gold nanoparticles that convert light energy to thermal energy or reactive oxygen species, while ultrasound-responsive systems utilize microbubbles or nanodroplets that cavitate upon ultrasonic exposure, disrupting carrier integrity and releasing encapsulated drugs.

Multi-stimuli responsive platforms represent the cutting edge of intelligent drug delivery, integrating responsiveness to multiple triggers for enhanced specificity. A notable example is the (maghemite/PLGA)/chitosan nanostructure that responds to pH, heat, and magnetic stimuli simultaneously [21]. In this tri-stimuli responsive system, the PLGA matrix provides pH-sensitive degradation through acid-accelerated hydrolysis, the embedded maghemite nanoparticles enable magnetic hyperthermia under external fields, and the chitosan shell offers additional pH-dependent solubility changes. This multi-functionality creates a sophisticated feedback system where drug release rates can be precisely modulated through combinatorial stimulation.

Table 1: Classification of Stimuli-Responsive Drug Delivery Platforms

| Stimulus Category | Specific Triggers | Responsive Mechanisms | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endogenous (Internal) | pH (acidic tumor microenvironment, ~5.0-6.5) | Protonation of polyelectrolytes, acid-labile bond cleavage, polymer swelling | Tumor-targeted chemotherapy, inflammatory disease treatment |

| Redox potential (elevated glutathione in cancer cells) | Disulfide bond cleavage in high glutathione environments | Intracellular drug delivery to tumor cells | |

| Enzymes (MMPs, hyaluronidases, proteases) | Enzyme-specific substrate degradation | Tumor microenvironment-targeted release, inflammatory sites | |

| Reactive oxygen species (elevated Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ in inflammation) | Oxidation-sensitive bond cleavage (thioether, selenide) | Inflammatory diseases, cancer therapy | |

| Exogenous (External) | Magnetic fields | Hyperthermia from superparamagnetic nanoparticles, particle alignment | Deep-tumor targeting, combined hyperthermia-chemotherapy |

| Light (UV, visible, NIR) | Photothermal conversion, photoisomerization, photocleavage | Superficial and deep-tumor treatment (with NIR) | |

| Ultrasound | Cavitation-induced carrier disruption, thermal effects | Deep-tissue applications, blood-brain barrier opening | |

| Temperature | Polymer phase transition (e.g., LCST of thermosensitive polymers) | Localized hyperthermia-triggered release |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Metrics of Drug Delivery Efficiency

Direct comparison of conventional PLGA systems and stimuli-responsive platforms reveals significant differences in key performance metrics, including drug loading capacity, encapsulation efficiency, release kinetics, and targeting precision. The following structured analysis synthesizes experimental data from multiple studies to provide researchers with a comprehensive efficiency assessment.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of PLGA vs. Stimuli-Responsive Platforms

| Performance Parameter | Conventional PLGA Systems | Stimuli-Responsive Platforms | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Loading Capacity (%) | 5-15% (small molecules) [19] | 10-25% (small molecules) [21] | Cisplatin loading: PLGA (≤15%) vs. (γ-Fe₂O₃/PLGA)/CS (~15%) |

| Encapsulation Efficiency (%) | 50-80% (variable by method) [23] | 70-95% (enhanced with responsive elements) [21] | Double emulsion methods with magnetic incorporation |

| Release Duration | Days to months (tunable via polymer properties) [19] | Hours to weeks (stimulus-dependent) [21] | Programmable release profiles with on-demand bursts |

| Burst Release (Initial 24h) | 15-40% (significant in many formulations) [19] | 5-20% (reduced with chitosan coating) [21] | Chitosan shell as diffusion barrier in (γ-Fe₂O₃/PLGA)/CS |

| Release Rate Modulation | 1.5-2.5 fold (via polymer composition) [19] | Up to 4.7-fold with dual stimuli [21] | pH 5.0 + 45°C vs. pH 7.4 + 37°C in (γ-Fe₂O₃/PLGA)/CS |

| Targeting Specificity | Passive (EPR effect primarily) [20] | Active (pathological microenvironment response) [21] [24] | Magnetic guidance + pH responsiveness in tumor models |

| Therapeutic Efficacy (ICâ‚…â‚€) | Varies with drug potency | ~1.6-fold improvement vs. free drug [21] | Cisplatin against A-549 human lung adenocarcinoma cells |

The data reveal that stimuli-responsive platforms significantly outperform conventional PLGA systems in several key metrics. Most notably, the release rate modulation capability of stimuli-responsive systems demonstrates a substantial advantage, with dual pH- and temperature-responsive systems achieving up to 4.7-fold faster release under trigger conditions compared to physiological conditions [21]. This controlled release enhancement directly translates to improved therapeutic efficacy, as evidenced by the 1.6-fold lower ICâ‚…â‚€ value of cisplatin-loaded (maghemite/PLGA)/chitosan nanoparticles compared to free cisplatin against human lung adenocarcinoma cells [21].

Additionally, stimuli-responsive platforms address the persistent challenge of initial burst release common in conventional PLGA systems. The incorporation of functional barriers, such as chitosan shells in (maghemite/PLGA)/chitosan nanostructures, effectively mitigates this issue by creating an additional diffusion barrier that minimizes premature drug release during the initial exposure period [21]. This controlled initial release profile contributes to reduced systemic toxicity and enhanced accumulation at the target site.

Experimental Models and Methodologies

The evaluation of drug delivery system efficiency employs standardized in vitro and in vivo models to assess release kinetics, targeting accuracy, and therapeutic outcomes. The following experimental protocols represent methodologies commonly cited in the literature for both PLGA and stimuli-responsive platforms.

In Vitro Release Kinetics Protocol:

- Media Conditions: Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at varying pH (7.4 simulating physiological conditions, 5.0-6.5 simulating pathological environments) and temperatures (37°C vs. 45°C for hyperthermia conditions) [21]

- Sample Collection: Aliquots withdrawn at predetermined time points (0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 48, 72, 96 hours) with media replacement to maintain sink conditions

- Analysis Method: UV spectrophotometry at wavelength specific to drug absorbance maximum (e.g., 301 nm for cisplatin) [21]

- Additional Stimuli Application: For magnetic-responsive systems, alternating magnetic field (AMF) application (e.g., 100-400 kHz for 10-30 minutes at specific intervals) to trigger release [21]

Cellular Uptake and Cytotoxicity Assessment:

- Cell Lines: Human cancer cell lines (e.g., A-549 lung adenocarcinoma, T-84 colon carcinoma) and normal fibroblast lines (e.g., CCD-18 colon fibroblasts) for selectivity evaluation [21]

- Incubation Conditions: 24-72 hour exposure to nanoparticle formulations at equivalent drug concentrations

- Viability Assay: MTT or similar colorimetric assay measuring mitochondrial activity of treated cells versus untreated controls

- Internalization Analysis: Flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy for fluorescently labeled nanoparticles

Hemocompatibility Testing:

- Protocol: Incubation of nanoparticle formulations with human blood samples (typically 1:9 ratio of nanoparticles to blood)

- Parameters: Hemolysis percentage, platelet activation, and complement system activation assessment

- Acceptance Criteria: <5% hemolysis generally considered compatible for intravenous administration [21]

The experimental workflow for evaluating stimuli-responsive systems incorporates additional validation steps for stimulus-specific responses, including pre- and post-stimulus release rate comparisons and imaging-guided localization assessment. These methodologies provide comprehensive data on both the baseline performance and activated response of advanced delivery platforms.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for evaluating drug delivery system performance, incorporating both standard characterization and stimulus-specific validation steps.

Advanced Applications and Theranostic Integration

Disease-Specific Implementation

The transition from conventional PLGA to stimuli-responsive platforms has enabled significant advances in disease-specific therapeutic applications, particularly in oncology, inflammatory disorders, and neurological conditions where targeted delivery is critical for efficacy and safety.

In oncology, stimuli-responsive platforms demonstrate superior performance in exploiting pathological hallmarks of the tumor microenvironment. The (maghemite/PLGA)/chitosan system exemplifies this approach, leveraging the acidic pH of tumors combined with externally applied magnetic fields to achieve spatially and temporally controlled drug release [21]. This dual-responsive behavior enables precise drug deployment at the target site while minimizing systemic exposure. Similarly, redox-responsive systems capitalize on the elevated glutathione concentrations in cancer cells (approximately 100-1000 times higher than extracellular levels) to trigger intracellular drug release through disulfide bond cleavage [24] [25].

For inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), pH- and enzyme-responsive nanomaterials have shown remarkable efficacy in achieving colon-specific drug delivery. These systems remain stable during transit through the upper gastrointestinal tract but selectively release their payload upon encountering the inflamed colonic microenvironment characterized by altered pH, elevated reactive oxygen species, and overexpression of specific enzymes [22]. This targeted approach enhances therapeutic efficacy while reducing systemic side effects common with conventional oral IBD treatments.

In neurological applications, the challenge of crossing the blood-brain barrier (BBB) has prompted the development of multifunctional PLGA-based nanoparticles that incorporate targeting ligands for receptor-mediated transcytosis. While still an area of active research, these systems show promise for enhancing drug delivery to central nervous system tumors by leveraging both passive and active targeting strategies [26] [20].

Theranostic Integration and Clinical Translation

The integration of therapeutic and diagnostic capabilities (theranostics) represents a significant advancement in stimuli-responsive platforms, enabling simultaneous treatment and monitoring of disease response. PLGA-based theranostic nanoparticles exemplify this approach by incorporating both therapeutic agents and imaging contrast materials (e.g., superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for MRI, fluorescent dyes for optical imaging) within a single platform [20].

These sophisticated systems allow researchers and clinicians to track nanoparticle distribution, monitor accumulation at target sites, visualize trigger activation, and assess therapeutic response in real-time. For instance, SPION (superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle)-tagged macrophages have demonstrated utility as both therapeutic carriers and MRI contrast agents for hepatic tumor imaging [24]. Similarly, PLGA-PEG nanoparticles encapsulating doxorubicin and SPIONs have shown superior cytotoxicity against cancer cells while enabling dual-mode MRI-fluorescence imaging [20].

The clinical translation pathway for these advanced systems involves rigorous evaluation of biocompatibility, biodegradation, and manufacturing reproducibility. PLGA maintains an advantage in this regard due to its established regulatory approval history and well-characterized safety profile. However, emerging stimuli-responsive platforms incorporating novel materials face additional regulatory hurdles requiring comprehensive assessment of potential long-term toxicity, particularly for non-degradable components [26] [20].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Drug Delivery System Development

| Reagent/Chemical | Function in Formulation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PLGA (50:50 to 85:15 L:G ratio) | Biodegradable polymer matrix providing controlled release kinetics | Core material for nanoparticle fabrication across all system types |

| Chitosan | Positively charged polysaccharide for surface functionalization | pH-responsive shell, mucoadhesive properties in (γ-Fe₂O₃/PLGA)/CS [21] |

| Maghemite (γ-Fe₂O₃) | Superparamagnetic iron oxide for hyperthermia and MRI contrast | Magnetic responsiveness in tri-stimuli systems [21] |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | Surfactant for emulsion stabilization during nanoparticle synthesis | Prevents aggregation in emulsion-based fabrication methods [19] [20] |

| Dichloromethane (DCM) | Organic solvent for PLGA dissolution in emulsion methods | Solvent for oil phase in single/double emulsion techniques [20] |

| Tin(II) bis(2-ethylhexanoate) [Sn(Oct)â‚‚] | Catalyst for ring-opening polymerization of PLGA | Synthesis of PLGA with specific molecular weights and end groups [19] |

| Glutathione | Reducing agent for evaluating redox-responsive systems | Simulating intracellular conditions for disulfide cleavage testing [24] |

| Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) | Proteolytic enzymes for enzyme-responsive system validation | Testing substrate cleavage in disease-mimicking environments [24] |

Future Perspectives and Research Directions

The evolution from PLGA to stimuli-responsive platforms continues to advance with several emerging trends shaping the future of controlled drug delivery. Integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning in nanoparticle design is accelerating the optimization of formulation parameters, potentially reducing the traditional trial-and-error approach to development [23]. The growing availability of comprehensive datasets documenting PLGA nanoparticle formulations provides valuable resources for data-driven design and predictive modeling [23].

Multi-stimuli responsive systems represent another frontier, with research increasingly focused on platforms capable of responding to three or more distinct triggers for enhanced specificity. These systems aim to create sophisticated logic-gated release mechanisms that activate only when multiple disease biomarkers are present simultaneously, thereby minimizing off-target effects [21] [22].

Cell-mediated delivery approaches incorporating stimuli-responsive elements show particular promise for overcoming biological barriers. The use of erythrocytes, immune cells, stem cells, and exosomes as delivery vectors, combined with responsive release mechanisms, creates hybrid systems that leverage both biological targeting and engineered control [24]. For example, macrophage-mediated delivery of doxorubicin-loaded liposomes has demonstrated enhanced accumulation in triple-negative breast cancer models, while SPION-tagged macrophages enable MRI-guided delivery and imaging in hepatic tumors [24].

Despite these advancements, significant challenges remain in scaling up manufacturing processes, ensuring long-term stability, and addressing regulatory requirements for complex combination products. The transition from laboratory-scale synthesis to Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) production presents particular hurdles for stimuli-responsive systems incorporating multiple functional components [26] [20]. Nevertheless, the continued convergence of materials science, pharmaceutical technology, and biological understanding promises to address these challenges and further advance the evolution of controlled release systems.

Diagram 2: Future research directions and technological convergence in advanced drug delivery systems, highlighting the multidisciplinary approach required for continued innovation.

The evolution from conventional PLGA systems to stimuli-responsive platforms represents a significant paradigm shift in controlled drug delivery, moving from passive sustained release to actively targeted, intelligence-based therapeutic deployment. While PLGA continues to provide a valuable foundation with its proven biocompatibility, tunable release kinetics, and regulatory acceptance, stimuli-responsive systems offer unprecedented precision through their ability to sense and respond to pathological cues.

The comparative analysis presented herein demonstrates that stimuli-responsive platforms consistently outperform conventional PLGA systems across multiple efficiency metrics, including drug release modulation, targeting specificity, and therapeutic efficacy. The experimental data confirm that multi-stimuli responsive systems, particularly those incorporating both endogenous and exogenous triggers, achieve superior control over spatiotemporal drug release profiles. These advanced platforms successfully address longstanding challenges in drug delivery, including premature release, off-target accumulation, and inadequate therapeutic concentrations at disease sites.

As the field continues to evolve, the integration of smart materials, biological targeting mechanisms, and diagnostic capabilities will further blur the boundaries between drug delivery systems and precision medicine tools. The ongoing convergence of materials science, pharmaceutical technology, and biological understanding promises to yield increasingly sophisticated platforms capable of adapting to dynamic disease states and patient-specific physiological conditions. This progression from simple controlled release to intelligently responsive therapeutic deployment ultimately heralds a new era in pharmaceutical technology, one characterized by enhanced efficacy, reduced side effects, and truly personalized treatment approaches.

From Bench to Bedside: Application Strategies and Material Innovations in Targeted Therapies

The evolution of nanomedicine has ushered in a new era for targeted drug delivery, particularly in treating challenging diseases like cancer and central nervous system (CNS) disorders. Among the most promising nanocarriers, lipid-based and polymeric nanoparticles have demonstrated exceptional capabilities in enhancing therapeutic efficacy while reducing systemic toxicity. These biomaterial systems address fundamental drug delivery challenges, including poor bioavailability, nonspecific biodistribution, and inability to cross biological barriers such as the blood-brain barrier (BBB). This comprehensive guide provides a comparative analysis of lipid and polymeric nanoparticle platforms, examining their distinct characteristics, performance metrics, and applications through synthesized experimental data and standardized methodologies to inform rational design choices for researchers and drug development professionals.

Comparative Structural and Functional Characteristics

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Lipid and Polymeric Nanoparticles

| Property | Lipid Nanoparticles | Polymeric Nanoparticles |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Composition | Ionizable lipids, phospholipids, cholesterol, PEG-lipids [27] | PLGA, chitosan, PLA, gelatin, dendrimers [28] |

| Common Size Range | 5-200 nm [29] | 10-200 nm [28] |

| Structure Type | Amorphous or non-bilayer core-shell [27] | Nanospheres (matrix) or nanocapsules (reservoir) [28] |

| Drug Encapsulation | Hydrophilic & hydrophobic agents, nucleic acids [27] | Small molecules, proteins, nucleic acids [28] [30] |

| Surface Modification | PEG-lipids, targeting ligands [27] | PEG, antibodies, peptides, folates [28] [30] |

| Release Mechanism | pH-responsive, endosomal escape [27] | Controlled diffusion, polymer erosion, stimuli-responsive [28] [30] |

| Key Advantages | Biocompatibility, clinical validation for RNA delivery [27] | Versatile design, controlled release profiles, high stability [28] |

| Primary Limitations | Potential immunogenicity, limited drug loading for some compounds [27] | Complexity in reproducibility, polymer-specific toxicity concerns [28] |

CNS Drug Delivery Applications and Performance

Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration Mechanisms

The blood-brain barrier represents the fundamental challenge for CNS drug delivery, with its tight junctions, selective permeability, and active efflux mechanisms restricting over 98% of small-molecule drugs and nearly all large-molecule therapeutics [29] [31]. Both lipid and polymeric nanoparticles have demonstrated capabilities to overcome this barrier through multiple mechanisms:

Receptor-mediated transcytosis: Nanoparticles functionalized with targeting ligands (antibodies, peptides, transferrin) engage specific receptors on BBB endothelial cells to initiate vesicular transport into the brain parenchyma [29].

Cell-mediated transport: Some nanoparticle systems are taken up by immune cells like monocytes or macrophages, which subsequently carry them across the BBB in a "Trojan horse" approach [29].

Direct translocation: Certain surface-modified nanoparticles can temporarily disrupt tight junctions or fuse with cell membranes to facilitate paracellular or transcellular transport [29].

Intranasal delivery: Both lipid and polymeric nanoparticles can bypass the BBB completely when administered intranasally, traveling along olfactory and trigeminal nerve pathways directly to the CNS [31].

Figure 1: BBB Penetration Pathways for Lipid and Polymeric Nanoparticles

Quantitative Performance in CNS Delivery

Table 2: CNS Therapeutic Applications and Outcomes

| Nanoparticle Type | Therapeutic Application | Model System | Key Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid Lipid Nanoparticles | Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, glioblastoma | Preclinical animal models | Successful BBB crossing, improved therapeutic distribution, enhanced drug effectiveness | [29] |

| Polymeric (PLGA) NPs | Brain tumor therapy | White albino rats | Enhanced drug concentration in brain compared to conventional delivery | [28] |

| Lipid-based Nanoemulsions | CNS disorders | In vitro & in vivo models | Direct nose-to-brain delivery, bypassing hepatic first-pass metabolism | [31] |

| Chitosan Nanoparticles | CNS drug delivery | Experimental models | Demonstrated ability to cross BBB, protection against chemical degradation | [28] |

| Polymeric Micelles | CNS disorders | Experimental models | Potential to improve drug transport across BBB via EPR effect and active targeting | [30] |

Cancer Therapy Applications and Performance

Tumor Targeting Mechanisms

Both lipid and polymeric nanoparticles leverage unique pathophysiological features of tumors for enhanced drug delivery, primarily through the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect, where the leaky vasculature and impaired lymphatic drainage of tumors allow selective accumulation of nanoscale particles [27] [28]. Beyond this passive targeting, both platforms can be functionalized with active targeting ligands that recognize tumor-specific biomarkers, enabling precise cell-specific drug delivery [27] [30].

Table 3: Cancer Therapy Applications and Experimental Outcomes

| Nanoparticle Formulation | Cancer Model | Therapeutic Payload | Key Experimental Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor-targeted Liposome (EY-L) | Renal cell carcinoma | Everolimus & YM155 | Significant tumor growth suppression, enhanced radiosensitivity in vitro and in vivo | [27] |

| PEG-HPMA Polymeric NPs | 4T1 and MCF-7 breast cancer | Doxorubicin | Enhanced cellular uptake and cytotoxicity compared to free doxorubicin | [28] |

| PLGA-PEG-PLGA NPs | HT29 colon cancer | 5-Fluorouracil & chrysin | High potent synergistic anticancer effect demonstrated | [28] |

| FA-L-PEG-PCL Polymeric NPs | MCF-7 breast cancer | Tamoxifen | Enhanced apoptosis of cancer cells, non-cytotoxic at high concentrations | [28] |

| LNP-mRNA Formulations | Various cancers | mRNA therapeutics | Efficient tumor-specific delivery, demonstrated in ongoing oncology clinical trials | [27] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Formulation Protocols

Lipid Nanoparticle Preparation (Ethanol Injection Method)

- Step 1: Prepare lipid phase by dissolving ionizable lipid, phospholipid, cholesterol, and PEG-lipid in ethanol at specific molar ratios (typical composition: 50:10:38.5:1.5 mol%) [27].

- Step 2: Prepare aqueous phase containing therapeutic payload (mRNA, siRNA, or small molecules) in citrate or acetate buffer (pH 4.0-5.0).

- Step 3: Rapidly mix lipid phase with aqueous phase using microfluidic device or rapid pipetting at 1:3 volume ratio (ethanolic:aqueous).

- Step 4: Dialyze against PBS (pH 7.4) to remove ethanol and establish neutral pH for storage.

- Step 5: Characterize particle size (target: 80-100 nm), polydispersity index (<0.2), encapsulation efficiency (>90%), and in vitro activity [27].

Polymeric Nanoparticle Preparation (Single Emulsion Solvent Evaporation)

- Step 1: Dissolve polymer (e.g., PLGA, PLA) and hydrophobic drug in organic solvent (dichloromethane or ethyl acetate).

- Step 2: Emulsify organic phase in aqueous solution containing stabilizer (e.g., polyvinyl alcohol) using probe sonication or high-pressure homogenization.

- Step 3: Stir continuously for 3-4 hours to evaporate organic solvent and allow nanoparticle hardening.

- Step 4: Centrifuge to collect nanoparticles, wash to remove stabilizer, and lyophilize for storage.

- Step 5: Characterize particle size, surface charge, drug loading, and in vitro release profile [28] [30].

Standardized Characterization Assays

- Size and Surface Charge: Dynamic light scattering for hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity; laser Doppler electrophoresis for zeta potential [30].

- Morphology: Transmission electron microscopy or cryo-TEM for structural analysis [27].

- Drug Encapsulation and Loading: Ultracentrifugation followed by HPLC/UV-Vis quantification of encapsulated vs. free drug [28].

- In Vitro Release Profile: Dialysis method in physiologically relevant buffers (pH 7.4 and 5.5) with sampling at predetermined time points [28] [30].

- Cell Uptake and Cytotoxicity: Flow cytometry with fluorescently labeled nanoparticles; MTT assay for cell viability [27] [28].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Nanoparticle Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids | DLin-MC3-DMA, SM-102, ALC-0315 | LNP core structure, endosomal escape | Critical for nucleic acid delivery; protonate in acidic endosomes [27] |

| Structural Lipids | DSPC, DPPC, DOPE | Bilayer formation, stability | Phospholipids that provide structural integrity to nanoparticles [27] |

| Stabilizing Polymers | PEG-DMG, PEG-DSPE | Steric stabilization, circulation half-life | Reduce protein adsorption and macrophage uptake [27] |

| Biodegradable Polymers | PLGA, PLA, PCL | Polymeric matrix for drug encapsulation | Tunable degradation rates from weeks to months [28] |

| Natural Polymers | Chitosan, gelatin, alginate | Biocompatible nanoparticle matrix | Mucoadhesive properties beneficial for mucosal delivery [28] |

| Targeting Ligands | Folate, transferrin, RGD peptides, antibodies | Active targeting to specific cells/receptors | Enhance cellular uptake through receptor-mediated endocytosis [30] |

| Characterization Dyes | DiO, DiI, DiD, Cyanine dyes | Nanoparticle tracking and cellular uptake studies | Lipid-soluble dyes incorporate into hydrophobic regions [27] |

Lipid and polymeric nanoparticles represent complementary platforms in the targeted drug delivery landscape, each with distinctive advantages for specific applications. Lipid nanoparticles excel in nucleic acid delivery with proven clinical success, biocompatibility, and efficient endosomal escape mechanisms. Polymeric nanoparticles offer superior controlled release profiles, extensive tunability of properties, and high stability. The selection between these platforms depends critically on the specific therapeutic payload, target tissue, and desired release kinetics. Future directions include the development of hybrid systems that combine advantageous properties of both platforms, increased application of artificial intelligence for rational nanoparticle design, and continued focus on overcoming biological barriers for enhanced therapeutic outcomes in both CNS disorders and cancer.

The skin, being the largest organ of the human body, serves as a primary physiological barrier that prevents external substances from entering the system, thereby posing significant challenges for transdermal drug delivery. Conventional topical formulations, including creams and patches, often fail to penetrate the stratum corneum barrier effectively, especially when the skin thickens due to conditions like psoriasis or when biofilms form over infectious wounds [32]. Among the various strategies developed to overcome this barrier, microneedle (MN) technology has emerged as a transformative approach in biomedical applications, offering a painless, minimally invasive, and highly efficient method for drug delivery [32] [33]. Microneedles are micron-scale needle arrays that can painlessly penetrate the stratum corneum to deliver therapeutic agents directly to the epidermis or dermis, bypassing pain receptors and avoiding the discomfort associated with hypodermic needles [34] [35].

Hydrogel-forming microneedles (HFMs) represent a particularly advanced category within this technology. Composed of crosslinked, hydrophilic polymer networks, HFMs undergo rapid swelling upon insertion into the skin, absorbing interstitial fluid to form continuous hydrogel conduits that enable efficient drug transport into the dermal microcirculation [32] [33]. Unlike conventional microneedles that primarily rely on passive diffusion, HFMs create a gel matrix reservoir that facilitates controlled and sustained drug release, thereby maintaining therapeutic levels over extended periods while significantly reducing dosing frequency [32] [34]. This review provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of hydrogel microneedles against alternative drug delivery platforms, examining their mechanical properties, drug delivery efficiency, release kinetics, and therapeutic performance through structured experimental data and methodological protocols.

Comparative Analysis of Microneedle Platforms

Classification and Mechanism of Action

Microneedle platforms can be broadly categorized into five distinct types based on their design and drug delivery mechanisms: solid, coated, hollow, dissolving, and hydrogel-forming microneedles [34] [36] [35]. Each system employs a unique approach for transdermal drug delivery, with varying implications for drug loading capacity, release kinetics, and clinical applicability.

Solid microneedles (SMNs) function primarily as piercing devices to create microchannels in the skin, after which a drug-containing patch is applied for diffusion [35]. While they exhibit excellent mechanical properties and simple preparation methods, they require a two-step application process and offer poor control over drug dosage and administration timing [34]. Coated microneedles (CMNs) consist of solid microneedles coated with drug formulations, enabling rapid delivery of therapeutic agents as the coating dissolves upon skin insertion [32] [35]. Although this design allows for substantial drug loading and dosage control, the preparation process is complex, and there is a risk of coating loss in the stratum corneum [34].

Hollow microneedles (HMNs) feature internal bores through which liquid drug formulations can flow, typically driven by external pressure [35]. These systems enable rapid drug delivery with controllable dosing but are prone to clogging, needle fracture, and flow leakage issues [34]. Dissolving microneedles (DMNs) are fabricated from biodegradable, water-soluble polymers that encapsulate drugs and fully dissolve upon insertion into the skin, releasing their payload [32] [35]. While they offer manageable dosing and high biocompatibility, they often suffer from poor mechanical properties and prolonged action duration [34].

Hydrogel-forming microneedles (HFMs), the focus of this review, are composed of crosslinked hydrophilic polymers that swell upon skin insertion without dissolving, forming hydrogel conduits that enable controlled drug release [32] [33]. The key differentiator of HFMs is that drug delivery is governed primarily by the crosslinking density of the hydrogel matrix rather than the permeability of the stratum corneum, allowing for precise modulation of release kinetics [32]. This unique mechanism provides exceptional drug loading capacity and tunable release profiles while avoiding the generation of sharp biological waste [32] [34].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Microneedle Platforms for Transdermal Drug Delivery

| MN Type | Mechanism of Action | Advantages | Disadvantages | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid MN | Pre-treatment skin perforation followed by drug patch application | Simple preparation; Excellent mechanical properties [34] | Two-step process; Poor drug dosage control; Potential needle breakage [34] [35] | Vaccine delivery; Skin preconditioning [35] |

| Coated MN | Drug coating dissolves upon skin insertion | Large drug load; Controllable dosage [34] | Complex preparation; Coating loss in stratum corneum; Risk of premature drug release [34] [35] | Rapid delivery of vaccines; Macromolecular drugs [35] |

| Hollow MN | Pressure-driven flow through internal bore | Fast drug release; Dose control [34] | Clogging risk; Needle breakage; Low drug load; Flow leakage [34] [35] | Liquid drug formulations; Continuous infusion [35] |

| Dissolving MN | Needle dissolution releases encapsulated drug | Simple production; Biocompatible; No sharp waste [34] [35] | Poor mechanical strength; Prolonged action; Material limitations [34] | Sustained release; Vaccine delivery [35] |

| Hydrogel-forming MN | Skin insertion → hydrogel swelling → controlled drug diffusion | Large drug load; Tunable release; Excellent biocompatibility; Controlled by crosslink density [32] [34] [33] | Moderate mechanical strength; Formulation complexity [34] | Sustained drug delivery; Chronic conditions; ISF monitoring [32] [33] |

Performance Metrics and Experimental Data

Quantitative evaluation of microneedle performance encompasses multiple parameters, including mechanical strength, insertion capability, drug release efficiency, and biocompatibility. Experimental data derived from recent studies enables direct comparison between hydrogel-forming microneedles and alternative platforms.

Mechanical properties represent a critical performance indicator, as microneedles must possess sufficient strength to penetrate the stratum corneum (approximately 10-20 μm thick) and reach the viable epidermis and dermis (100-150 μm) without fracture [32] [36]. Research has demonstrated that optimized HFMs composed of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) crosslinked with glutaraldehyde achieve a fracture force of 0.13 N per needle, substantially exceeding the minimum 0.058 N required for skin penetration [36]. Similarly, HFMs fabricated from PVA, PVP, and poly(ethylene glycol) diacid (PEGdiacid) exhibited minimal height reduction (7.67%) under 32 N compression pressure and successfully achieved insertion depths of 508-522 μm, effectively penetrating the stratum corneum while maintaining structural integrity [36].

Drug release kinetics vary significantly across microneedle platforms. Coated and dissolving microneedles typically exhibit rapid drug release, often within minutes to hours, while hydrogel-forming systems demonstrate extended release profiles ranging from days to weeks [32] [34]. For instance, a cyclosporine A-loaded HFM system for psoriatic treatment demonstrated sustained drug release over 72 hours, maintaining therapeutic concentrations with significantly enhanced skin deposition compared to conventional topical formulations [37]. Similarly, HFMs incorporating poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) and PMVE/MA copolymers for acyclovir delivery achieved 75.56% drug release within 24 hours, with a transdermal absorption rate 39 times higher than conventional topical applications [36].

Drug loading capacity represents another distinguishing factor. While coated microneedles are limited by surface area and hollow microneedles by internal volume, hydrogel-forming systems utilize the entire polymer matrix for drug incorporation, enabling substantially higher payloads [32] [34]. This expanded capacity is particularly advantageous for macromolecular drugs, including proteins, peptides, and nucleic acids, which typically require frequent administration in conventional delivery systems [33].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics of Microneedle Platforms

| Performance Parameter | Hydrogel-forming MNs | Dissolving MNs | Hollow MNs | Coated MNs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Fracture Force (N/needle) | 0.13 [36] | 0.08-0.10 [34] | 0.15-0.20 [34] | 0.10-0.12 [34] |

| Insertion Depth (μm) | 500-522 [36] | 300-400 [34] | 500-1000 [34] | 200-300 [34] |

| Drug Release Profile | Sustained (hours to days) [32] | Rapid (minutes to hours) [34] | Immediate (minutes) [34] | Rapid (minutes) [34] |

| Transdermal Permeation Enhancement | 39-fold increase [36] | 10-20 fold increase [34] | 20-30 fold increase [34] | 5-15 fold increase [34] |

| Macromolecule Delivery Capacity | Excellent [32] [33] | Good [34] | Limited [34] | Limited [34] |

| Skin Recovery Time | 2-4 hours [32] | 4-8 hours [34] | 1-2 hours [34] | 2-4 hours [34] |

Experimental Protocols for HFM Evaluation

Fabrication Methodologies

The manufacturing process for hydrogel-forming microneedles significantly influences their structural integrity, mechanical properties, and drug delivery performance. Micro-molding represents the most widely employed fabrication technique, comprising several standardized steps [32] [34].

Master Mold Preparation: A negative mold containing the desired microneedle geometry (typically 100-1500 μm height, 50-250 μm base width) is fabricated using techniques such as hot embossing, micro-molding, thermal-drawing lithography, magneto-rheological lithography, laser drilling, or increasingly, 3D printing for enhanced customization [32] [38].

Hydrogel Formulation: Biocompatible polymers—including gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA), hyaluronic acid (HA), chitosan, silk fibroin (SF), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), or combinations thereof—are dissolved in aqueous solution along with crosslinking agents [32] [34]. Active pharmaceutical ingredients are incorporated into this polymer mixture, with homogenization ensuring uniform drug distribution.