Building a Better Belly

How Scientists Are Engineering New Abdominal Walls

Forget stitches and synthetic mesh. The future of healing major abdominal injuries lies in regenerating brand new, living tissue.

Imagine the delicate, intricate structure of your abdominal wall. It's not just muscle for doing crunches; it's a dynamic, living corset of tissue that protects your internal organs, helps you stand upright, cough, and bend. Now, imagine a large section of this wall is gone—removed due to a traumatic injury, a battle with cancer, or a severe infection.

This is a devastating clinical problem called "large abdominal wall defect." Surgeons traditionally patch these holes with synthetic mesh, but it's an imperfect solution. The mesh can become infected, cause pain, and doesn't grow or function like real tissue, especially in children. But what if instead of patching the hole, we could regrow the wall?

Welcome to the frontier of regenerative medicine, where scientists are moving beyond repair and into the realm of rebirth. This is the story of how tissue engineering is using a scaffold, a patient's own cells, and the body's innate healing power to experimentally build a new abdominal wall from scratch.

The abdominal wall is a complex structure of muscles and tissues that protects internal organs.

The Blueprint for Regeneration: Core Concepts

Tissue engineering is like advanced biological architecture. To build a new tissue, you need three key components, often called the "Tissue Engineering Triad":

The Scaffold

This is the 3D framework. Think of it as the construction scaffolding for a new building. It must be biocompatible (not rejected by the body), biodegradable (it should dissolve safely after it's done its job), and have the right physical structure for cells to latch onto and grow.

The Cells

These are the construction workers and building materials. Scientists often use a patient's own stem cells or muscle cells (myoblasts). Using the patient's own cells eliminates the risk of rejection and provides the raw material for functional, living tissue.

Signals (Bioactive Molecules)

These are the foremen and blueprints. They are growth factors and chemicals that signal to the cells, telling them to multiply, turn into specific tissue types (like muscle or blood vessels), and organize themselves properly.

The ultimate goal? To implant a "construct" combining these three elements into the defect, where it will integrate with the body, the scaffold will dissolve, and a new, fully functional, and strong abdominal wall will take its place.

An In-Depth Look: The Groundbreaking Experiment

To turn this theory into reality, researchers design meticulous experiments. Let's break down a typical, pivotal study in this field.

The Mission

To test whether a tissue-engineered construct, made from a biodegradable scaffold seeded with a patient's own muscle cells, can effectively regenerate a functional abdominal wall in a large animal model (e.g., a pig or rat), outperforming a standard synthetic mesh.

The Methodology: A Step-by-Step Guide

The experiment was carefully designed to mimic a human clinical scenario.

A porous, biodegradable scaffold made from a material like Polycaprolactone (PCL) or a blend of natural polymers (e.g., collagen) is sterilized. Its structure is designed to mimic the natural extracellular matrix that cells grow on.

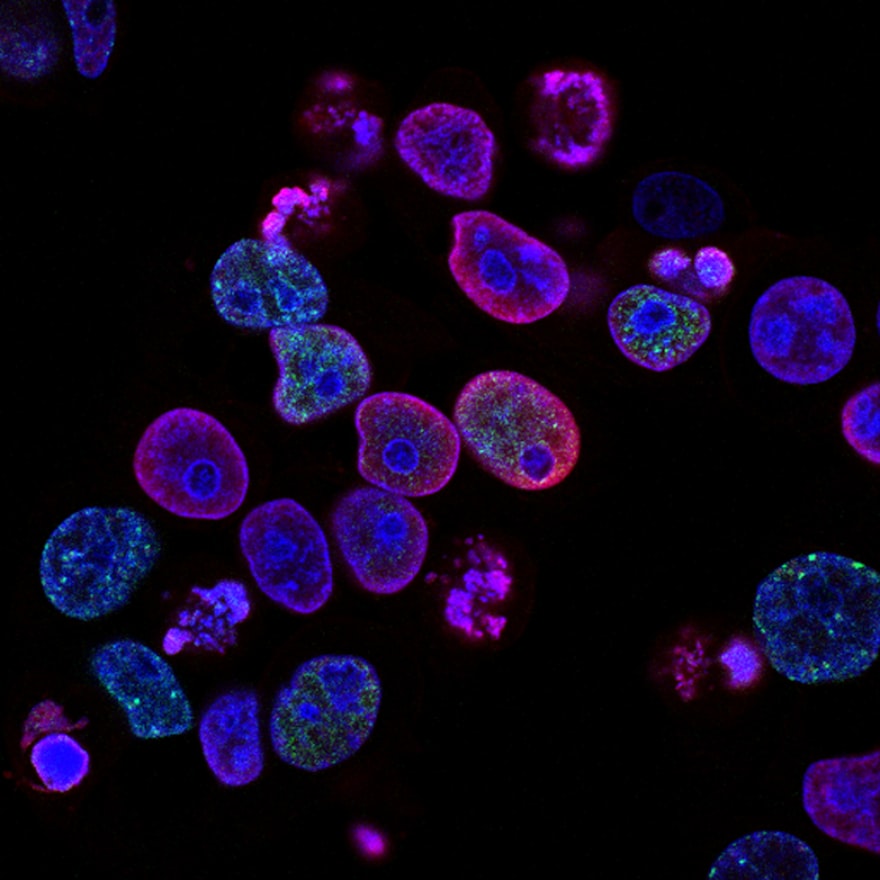

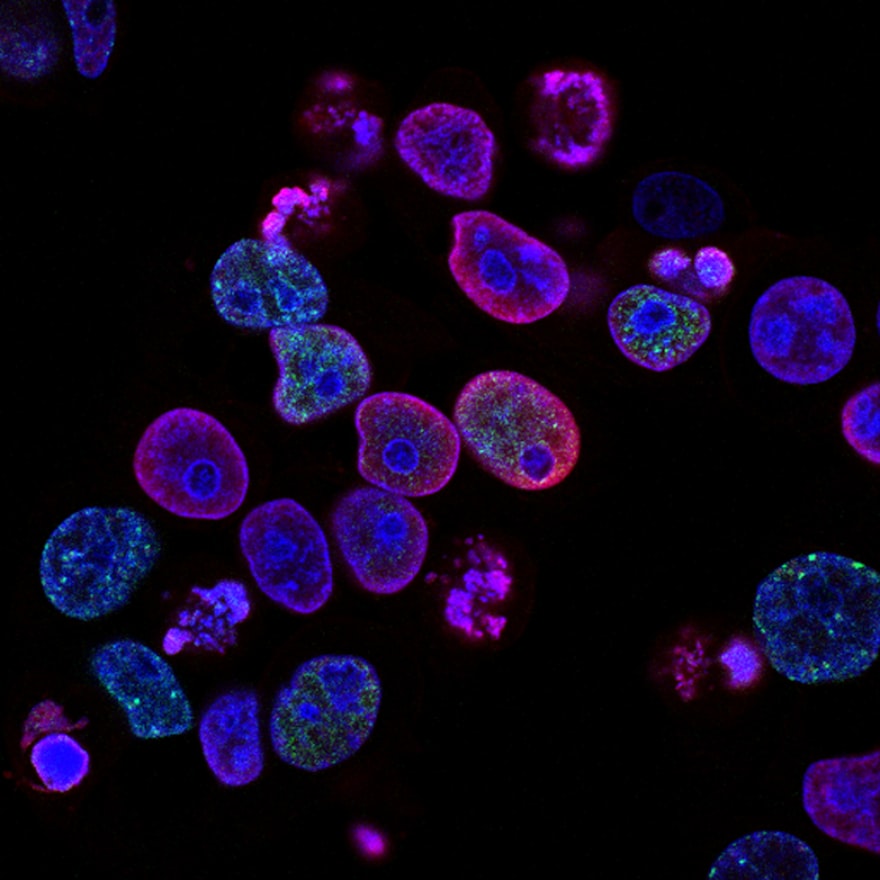

A small muscle biopsy is taken from the animal. Muscle progenitor cells (myoblasts) are isolated and multiplied in the lab over several weeks. These "super-charged" cells are then carefully seeded onto the scaffold, where they attach and begin to form a living layer.

The researchers surgically create a standardized, critical-sized defect (one that is too large to heal on its own) in the abdominal wall of the animal.

- Experimental Group: The defect is repaired with the new tissue-engineered construct (scaffold + cells).

- Control Group 1: The defect is repaired with the scaffold alone (no cells).

- Control Group 2: The defect is repaired with a standard, commercially available synthetic mesh (the current clinical standard).

After a set period (e.g., 3-6 months), the animals are examined. The implant sites are analyzed for:

- Strength: Using a mechanical tester to measure the burst strength

- Integration: How well the new tissue has connected to the native tissue

- Tissue Regeneration: Microscopic analysis for new muscle fibers and blood vessels

- Immune Response: Checking for signs of rejection or scar tissue formation

The Results and Why They Matter

The results from such experiments are consistently promising and highlight the superiority of the tissue-engineered approach.

Superior Strength

The cell-seeded constructs achieved burst strength nearly equivalent to the native, healthy abdominal wall, significantly outperforming the scaffold-only and synthetic mesh groups.

True Regeneration

Under the microscope, the experimental group showed remarkable regrowth of organized, striated muscle fibers and a dense network of new blood vessels. The synthetic mesh, in contrast, was mostly encapsulated by scar tissue with no evidence of new muscle formation.

Reduced Complications

The engineered tissue groups showed significantly fewer adhesions to the intestines and lower rates of infection compared to the synthetic mesh groups.

Scientific Importance

This proves that a "living patch" is not just a concept. It demonstrates that by providing the right structural and biological cues, we can coax the body into regenerating complex, functional tissues instead of just forming scar tissue. It moves the goal from mere mechanical repair to true biological restoration.

Burst Strength Comparison (after 12 weeks)

Pressure (in mmHg) the repaired abdominal wall could withstand before failing

Data at a Glance: Measuring Success

| Group | Average Burst Strength (mmHg) | % of Native Tissue Strength |

|---|---|---|

| Native Tissue (Healthy) | 320 | 100% |

| Tissue-Engineered Construct | 305 | 95% |

| Scaffold Only | 210 | 66% |

| Synthetic Mesh | 250 | 78% |

| Group | New Muscle Formation | Vascularization (Blood Vessels) | Adhesions to Bowel |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue-Engineered Construct | 2.8 | 2.9 | 0.5 (Mild) |

| Scaffold Only | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.2 (Moderate) |

| Synthetic Mesh | 0.2 | 0.7 | 2.8 (Severe) |

| Group | Infection Rate | Seroma (Fluid Build-up) Rate | Re-Herniation Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue-Engineered Construct | 0% | 10% | 0% |

| Scaffold Only | 10% | 20% | 20% |

| Synthetic Mesh | 30% | 25% | 10% |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Building living tissue requires a specialized toolkit. Here are some of the essential components used in this pioneering research.

Biodegradable Polymer (e.g., PCL)

Serves as the physical scaffold. Its slow degradation rate provides mechanical support long enough for new tissue to form.

Collagen (Type I)

A natural protein found in skin and muscle. Often used to coat synthetic scaffolds to make them more "sticky" and recognizable for cells to adhere to.

Growth Factors (e.g., VEGF, FGF)

Proteins added to the cell culture or scaffold. They act as signals, stimulating cells to grow, differentiate, and form new blood vessels (angiogenesis).

Enzymes (e.g., Collagenase)

Used to carefully digest the initial muscle biopsy and break it down to isolate the precious individual muscle progenitor cells.

Cell Culture Medium

A specially formulated nutrient-rich "soup" that provides everything the harvested cells need to survive, multiply, and thrive outside the body before implantation.

Conclusion: From Lab Bench to Bedside

The experimental evidence is compelling. Tissue engineering offers a paradigm shift in how we approach massive tissue loss. While challenges remain—such as scaling up the production of cells and ensuring the long-term stability of the regenerated tissue—the path forward is clear.

This research moves us closer to a future where a soldier wounded by an explosive device, a cancer survivor, or a child with a congenital defect can receive a personalized, living graft that heals, grows, and functions as nature intended. We are not just learning to patch the human body; we are learning to rebuild it.

References:

The future of abdominal wall repair lies in regenerative techniques that restore full function.